Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

High Court of Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> High Court of Ireland Decisions >> Fernleigh Residents Association & Anor v An Bord Pleanala & Ors (Approved) [2023] IEHC 525 (27 September 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IEHC/2023/2023IEHC525.html

Cite as: [2023] IEHC 525

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

THE HIGH COURT

JUDICIAL REVIEW

Record Number: 2021/804 JR

In the matter of Section 50, 50A and 50B of the Planning and Development Act 2000 and in the matter of the Planning and Development (Housing) and Residential Tenancies Act 2016

Between

FERNLEIGH RESIDENTS ASSOCIATION

AND

BRIAN CASSIDY

Applicants

and

AN BORD PLEANÁLA,

IRELAND AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

Respondents

and

IRONBORN REAL ESTATE LIMITED

Notice Party

JUDGMENT OF MR JUSTICE DAVID HOLLAND DELIVERED 27 SEPTEMBER 2023

Contents

BOARD’S DIRECTION AND ORDER. 7

PRESUMPTION OF VALIDITY - HOW TO READ AN ADMINISTRATIVE DECISION.. 8

S.9(3) & (6) of the 2016 Act. 11

S.28 PDA 2000 - Guidelines & SPPRs. 12

SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 & Ironborn’s Reliance Thereon. 12

S.37(2)(c) PDA 2000 - Reasons, Intermingling of Reasons & Discretion to Refuse Certiorari 13

INSPECTOR’S REPORT - MATERIAL CONTRAVENTION AS TO HEIGHT & SPPR3 OF THE HEIGHT GUIDELINES. 16

Daylight - Pleadings & Submissions. 17

Daylight - Introduction, §3.2 & SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 & Apartment Guidelines. 18

Daylight - BRE Guide, Daylighting Code & Caselaw.. 22

BRE Guide ADF Standards - applicable to Apartments?. 25

Developer’s Failure to Demonstrate Compliance - Walsh. 28

The Applicable ADF Standard for LKD Rooms. 29

Appropriate & Reasonable Regard to the BRE Guide and to the BS. 29

Identification of Non-Compliance & its Extent & Justification thereof - Walsh. 31

Daylight - Ironborn’s Light Report, Planning Report & Material Contravention Statement. 34

Daylight - Inspector’s Report. 37

Inspector’s Report - 2nd half of §12.5.8. 39

Inspector’s analysis at 2% ADF - §12.5.11 et seq. 41

Inspector’s Report & Fernleigh’s Daylight Tables. 44

Inspector’s Analysis - Continued - §12.5.14 et seq. 45

Inspector on Compensatory Design Solutions & his Conclusion. 46

Daylight - Further Discussion & Decision. 50

2 - OPEN SPACE - MATERIAL CONTRAVENTION.. 52

Figure 1 - Layout of the Proposed Development - general illustration. 52

Open Space - Quantification. 53

Figure 2 - DLRCC-owned open space and walkway. 53

Open Space - §8.2.8 of the Development Plan - Dispute as to Interpretation & Decision Thereof. 57

Open Space - Ironborn’s Planning Application and Reports. 62

A Distinction - Interpretation/Irrationality. 66

Open Space - Board Decision and Inspector’s Report. 67

Open Space - Fernleigh Pleadings & Submissions. 69

Open Space - ABP Pleadings & Submissions. 71

Open Space - Board’s Characterisation of DLRCC Position. 73

Open Space - The Exceptionality Criterion. 74

An Taisce v ABP & McQuaid Quarries. 76

Jennings, Redmond, Sherwin, Crekav & Mulholland. 77

Open Space - New Underground Attenuation Tank, Bike Spaces & Sunlight - Decision. 81

3 - PUBLIC TRANSPORT CAPACITY. 86

Transport - Traffic & Transport Assessment, Material Contravention Statement & Planning Report. 87

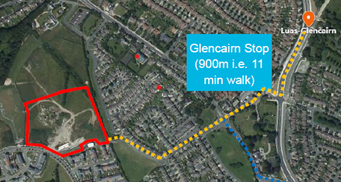

Figure 3 - Site relationship to nearest Luas Station. 88

Transport - DLRCC CEO Report & Transport Report. 90

Transport - A note on the Apartment Design Guidelines 2020. 92

Transport - Caselaw - O’Neill, Ballyboden & Jennings. 93

Transport - Fernleigh Pleadings & Submissions. 96

Transport - The Board’s Pleading & Submissions - GDA Transport Strategy & Comment thereon. 97

Transport - Inspector’s Report, Board Decision & Comment thereon. 102

4 - EIA - NO PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION.. 110

Bats - The Facts & Comment thereon. 113

Bats - Fernleigh Pleadings & Submissions. 115

Bats - Board Pleadings & Submissions. 116

Bats - Discussion & Decision. 118

6 - S.37 PDA 2000 - STRATEGIC NATURE OF PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT. 122

Introduction & Caselaw on the meaning of “Strategic”. 122

The Facts, Discussion & Decision. 123

7 - OTHER RELEVANT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENTS (Art 299B PDR 2001) 126

Article 299B, the Pleadings, Facts and Context. 126

Waltham Abbey, Discussion & Decision. 129

8 - INCOMPATIBLE PERMISSIONS - UNAUTHORISED DEVELOPMENT. 132

Incompatible Permissions - The Facts. 132

Incompatible Permissions - The Inspector’s Report and the Board’s Decision. 134

Incompatible Permissions - Dwyer Nolan & South-West Regional Shopping Centre. 134

INTRODUCTION [1]

1. The First Applicant (“Fernleigh”) seeks certiorari quashing the decision (“the Impugned Permission”) of the Respondent (“the Board”) dated 15th July 2021 [2] granting, under the 2016 Act [3] planning permission to the Notice Party (“Ironborn”) to build a Strategic Housing Development (“SHD” [4]) of 445 Build-to-Rent (“BTR” [5]) 1- and 2-bedroom apartments in 9 blocks [6] of up to 8 storeys over basements, a childcare facility and associated works (the “Proposed Development”) all at 2 non-contiguous sites in ‘Sector 3’, Aiken’s Village, Stepaside, Dublin 18 (“the Site”). [7] The total Site area is recorded at about 3.39 hectares. [8] Density is recorded at 156 units/ hectare. [9] In granting permission, the Board agreed with its Inspector’s report.

2. As is well-known and is well-recognised judicially, [10] the 2016 Act was prompted by the national housing crisis which has for many years proved intractable and which subsists today as a consideration highly relevant to proper planning and sustainable development.

3. Fernleigh is an association of residents who live in the Fernleigh residential estate immediately east of and adjoining the Proposed Development. Fernleigh participated as an objector in the planning process. Fernleigh say they do not oppose residential development of the Site but that the Proposed Development would overdevelop it. It seems fair to illustrate Fernleigh’s view, without adopting it, by noting that the planning history for the Site is of permitted density increased successively from 121 units to 243 units to 445 units. [11] Whether that is a good thing is not for the Courts to decide - it is a matter of planning judgment for the Board, which judgment it has exercised in favour of that increased density.

4. The Second Applicant is no longer prosecuting these proceedings. The Notice Party filed a Statement of Opposition but later abandoned participation in the proceedings. A challenge to the constitutionality of s.28(1C) PDA 2000 [12] and all issues as against the State Respondents stand adjourned pending adjudication of the other issues in the case. So the State Respondents did not participate in the trial.

5. The Site is in the functional area of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council (“DLRCC”) and the Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Development Plan 2016-2021 (the “Development Plan”) applies. It is largely zoned residential. An existing area of DLRCC-owned open space is zoned for open space. There is no zoning controversy in the case.

6. The Inspector and the Board found a material contravention of the Development Plan as to building height. [13] The Development Plan, via its Policy UD6: Building Height Strategy, applies a general height limit of two storeys to the area in which the Site sits. But a maximum of 3-4 storeys may be permitted in appropriate locations. Minor modification of that maximum of 3-4 storeys, up or down by up to 2 floors, can be considered if identified “modifiers” are present. However, given the Proposed Development includes height of up to 8 storeys and as the Inspector and the Board found a material contravention as to height, it is not necessary here to interrogate the detail of Policy UD6. Given that material contravention, the validity of the Impugned Permission depends on the Board’s satisfaction of the statutory requirements allowing it, in limited circumstances, to grant permission despite a material contravention of the Development Plan.

7. Fernleigh is prosecuting some only of the grounds on which it got leave to seek judicial review and this judgment is structured accordingly.

DLRCC REPORT

8. DLRCC’s statutory report to the Board [14] recommended refusal of permission. DLRCC considered that the Proposed Development was, overall, not consistent with relevant objectives of the Development Plan. Amongst DLRCC’s reasons for recommending refusal, the following are here relevant: [15]

· 1 - The Proposed Development would seriously impact on existing and future residential amenities … inter alia through a lack of quality open space and by way of breach of the Development Plan

o Policy UD6 of Building Height Strategy [16],

o §8.2.8.3, (headed “Landscape Plans”),

o §8.2.8.3, (headed “Public/Communal Open Space - Quality”).

· 3 - The Proposed Development would prevent completion of the partly-built development permitted by planning permission D10A/0440 and so would materially contravene a condition of an existing permission for development which has been partly-built and thus would be prejudicial to the orderly development of the area.

· 4 - The Site is not suitable for BTR apartments. It is not well-served by public transport and the application overestimates its proximity/ accessibility/ connectivity to good public transport. The Site is highly suburban and not sufficiently near large retail units and services or employment locations to negate the need for a car. So, the unrealistic low provision of car parking spaces in the Proposed Development would negatively impact existing residential amenity in an area already suffering traffic management issues. [17] The Proposed Development would endanger public safety by reason of being a traffic hazard or obstruction to road users or otherwise.

9. DLRCC summarises the issues raised in the 161 submissions [18] made in public participation. The elected members views [19] were broadly similar and, inter alia, included: [20]

· Excessive height and density.

· Luas capacity issues are such that residents already travel in the direction opposite to their destination to get access. It is “bursting at the seams”.

· Recent concerns raised by the OPR [21] regarding the ability of public transport to accommodate multiple developments along the M50 motorway and Luas lines. [22]

· Many other developments and the resultant population increase (listed and including “enormous development at Cherrywood” [23]) have not been considered in public transport capacity planning for the area and will more than consume the planned increased capacity of longer Luas carriages.

· Too few buses serve the area - only hourly.

· The availability and frequency of public transport will not suffice to result in the hoped-for high public transport use, and resultant low car ownership, by the tenants of the Proposed Development. Occupants will need cars as local transport is inadequate - including a lack of Luas capacity.

· Excessive traffic generation in an area which already has severe traffic problems. The roads can’t take existing traffic. Long traffic delays are already a serious issue.

· The Proposed Development, with inadequate car parking and with 5 other named nearby SHD schemes, will put pressure on already insufficient local road parking.

· Lack of open/green space in the Proposed Development is “striking”.

As its reasons set out above demonstrate, the executive of DLRCC essentially agreed with these submissions.

10. I will return to DLRCC’s views on public transport when considering the challenge under that heading. Suffice it to say now that DLRCC - both its executive and elected members - clearly had significant concerns as to public transport. It also had significant concerns as to road traffic and parking - in considerable degree informed by what it saw as the inadequacy of public transport.

11. In addition, DLRCC states that the Developer’s 'Sunlight, Daylight and Shadow Assessment' does not assess the kitchens to the applicable 2% ADF [24] standard set by BS 8203-2 - Code of Practice for Daylighting. Of the rooms tested, a significant number fall below 2% and so look dull, such that electric lighting is likely to be turned on.

12. As to communal/ public open space, DLRCC says the scheme “appears to work towards the minimum standards required. Given the vacant nature of the site, this is disappointing.” [25] As has been seen, DLRCC’s reasons for recommending refusal included a “lack of quality open space”.

BOARD’S DIRECTION AND ORDER

13. Insofar as relevant to these proceedings, the Board:

· “Decided to grant permission generally in accordance with the Inspector’s recommendation”. [26]

· Found a material contravention of the Development Plan as to building height.

· Applied s.37(2) PDA 2000 [27] in granting permission despite that material contravention as to building height. It recorded:

o As to s.37(2)(b)(i), the application was lodged under the SHD legislation [28] and the Proposed Development is strategic in nature and relates to matters of national importance - the delivery of housing. The proposal represents the regeneration of an important site in Stepaside, and contributes 445 Build-to-Rent units to the housing stock, and, therefore, seeks to address a fundamental objective of the Housing Action Plan [29], and such addresses a matter of national importance, that of housing delivery.

o As to s.37(2)(b)(iii), the proposal has been assessed against the criteria set out in §3.2 of the Height Guidelines 2018 (“§3.2”), which state, inter alia, that building heights must be generally increased in appropriate urban locations subject to those criteria. (As §3.2 of the Height Guidelines 2018 sets the criteria for application of SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018, this passage in substance invokes SPPR3.)

o As to s.37(2)(b)(iv), the Board cites precedent permission for material contravention as to height on a nearby site. [30]

· Screened out both AA and EIA. The Board does not record, and it is agreed it did not do, a Preliminary Examination [31] prior to its EIA Screening.

PRESUMPTION OF VALIDITY - HOW TO READ AN ADMINISTRATIVE DECISION

14. The Board makes a general allegation - or at least a repeated allegation, as to the questions whether,

· the Board found that the proposed open space is of exceptionally high quality,

· the materials before the Board and the Inspector’s report identified the rationale for design solutions compensatory for below-target daylight provision in the apartments, and

· the Impugned Permission is invalid as inconsistent with an earlier Planning Permission

It alleges in these respects that Fernleigh is guilty of reading the Impugned Permission “as invalid rather than valid (i.e., the opposite of the approach that should be taken …. which is to read such documents in a way that makes sense and renders them valid rather than invalid.”

15. It is worth briefly considering, from a general perspective, the principle invoked by the Board. M.E.O. [32] is authority that this principle derives from the presumption of validity of administrative decisions and that, “on a fair reading”, “An administrative decision should be read, where possible, in a way that renders it valid rather than invalid.” This approach was described in M.R. [33] as “fundamental” and in O.A. [34] the word “must” is used rather than “should”. In the planning context, Humphreys J in a Sweetman case [35] considered it “more appropriate to construe administrative decisions in a way that makes sense and renders them valid rather than invalid”.

16. The principle is undoubtedly correct and well-established in authority. But the phrases “makes sense”, “where possible” and “on a fair reading” are important.

17. The presumption of validity of an impugned decision is potentially applicable to an administrative decision in various ways (I do not pretend to be exhaustive in this regard):

a. The presumption seems to be primarily a principle that, generally at least, a decision is legally consequential unless and until set aside by a court of competent jurisdiction [36] as “…. in the interests of good order and administration. Citizens must be allowed to rely on public acts until they are set aside in the appropriate way and they should not be encouraged to take the law into their own hands.” [37]

b. In judicial review the presumption, being rebuttable, primarily emphasises that the onus of proof is on the applicant - see Weston and Balz. [38] But, on ordinary principles of litigation, that would be so in any event.

c. As a principle affecting the interpretation of an administrative decision, it seems to me that the presumption only arises where the decision is ambiguous and on one fair reading is valid and on another fair reading is invalid. If, where the decision is ambiguous, one fair reading keeps the decision valid, the presumption suggests that, ceteris paribus, it be the interpretation adopted. For example, that is how the principle was applied by the Supreme Court in Krikke [39] - though the court did not address whether the principle was confined to such situations. But genuine ambiguity is required before the principle takes effect and the courts do not strain to find ambiguity in formal consequential documents where none exists. [40] The principle does not seem to me to justify a strained, unreal or unfair interpretation of an administrative decision. The principle does not save a decision fairly capable only of a meaning or meanings which would result in its being invalid.

This last observation seems to me consistent, if by analogy, with the view of Barton J in Balz [41] that the presumption of validity cannot cure a deficiency in the record of an administrative decision where that deficiency results in inability to determine whether legal obligations have been met.

18. As Murray J noted in Stanberry, [42] the presumption of validity is associated with the principle of curial deference. He said that, without significant qualification, the proposition that Courts should be “slow to interfere with the decisions of expert administrative Tribunals” is “apt to mislead”. While stating that the scope for deference was limited, he did, of course, emphasise that issues will arise which are “peculiarly suited to the expert determination of the specialist body” and “where an appeal on a point of law presents an issue of underlying fact or inference in relation to matters within those zones of expertise, the Courts should certainly afford very significant weight to the decision of the expert body”. The same principle applies in judicial review. But Stanberry was a case in which Murray J considered that the Commissioner for Valuation was seeking to “extract from ‘curial deference’ a supercharged presumption of validity.” Murray J continued:

“It was claimed at one point, for example, that the Court failed to observe due deference to a specialist body by failing to adopt one interpretation of the last paragraph of the conclusions section of the Tribunal’s decision: the Commissioner has sought to contend that ‘curial deference’ means that if there were two possible interpretations of the decision of the Tribunal available, the Court is required to adopt the interpretation that upholds it. That is not a correct statement of the principle. Deference means that in those areas touching on the Tribunal’s expertise, the Court should be slow to interfere with the Tribunal’s reasoning. It does not mean that where the Tribunal’s reasoning is unclear so that there are differing possible interpretations of its decision the Court must simply assume that it was correct in the conclusion it reached. As Charlton J. said in EMI Records v. Data Protection Commissioner at para. 22, “curial deference cannot possibly arise where by statute reasons for a decision are required but none are given.” ‘Curial deference’ is thus properly understood as depending on the Tribunal having provided a properly reasoned decision, not as affording a mechanism for compensating where the decision is not so reasoned.”

Murray J also observed that discerning the meaning of a decision should not require speculation and the court should not rewrite an impugned decision so as to sustain its validity.

19. In short, the presumption of validity, curial deference and the principle of reading a decision as valid rather than invalid where possible, are important. On occasion they are decisive in upholding an impugned decision. But they are not talismans against invalidity as a result of interpretation of an impugned administrative decision or a warrant for a strained, unreal or unfair interpretation of such a decision or a basis for assuming validity where a decision is inadequately reasoned. Both deployment of expertise and adequacy of reasons are pre-conditions of curial deference. And reliance by a decision-maker on the clarity of its decision is far more attractive than its recourse to the presumption of validity.

20. Though it is obvious and no argument to the contrary was made, it may be useful to observe that the principle of reading a decision as valid rather than invalid where possible applies only to the impugned administrative decisions themselves. It does not apply to other generally applicable documents relevant to the validity of an impugned decision. So, for example, one cannot read a development plan or a planning guideline on that principle with a view to validating a particular impugned decision. One way of explaining this is that, whereas impugned decisions are of particular application, development plans are of general application - including to decisions other than that impugned - and the development plan cannot mean different things depending on the light shone on it by the particular impugned decision under consideration.

MATERIAL CONTRAVENTION - SOME RELEVANT STATUTORY PROVISIONS, SPPR3 OF THE HEIGHT GUIDELINES & OTHER MATTERS

21. It is useful at this point to set out some statutory provisions relevant to the possibility of granting SHD planning permission despite material contravention of the relevant development plan.

S.9(3) & (6) of the 2016 Act

22. S.9(3) of the 2016 Act provides that:

“(3) (a) When making its decision in relation to an application under this section, the Board shall apply, where relevant, specific planning policy requirements of guidelines issued by the Minister under section 28 of the Act of 2000.

(b) Where specific planning policy requirements of guidelines referred to in paragraph (a) differ from the provisions of the development plan of a planning authority, then those requirements shall, to the extent that they so differ, apply instead of the provisions of the development plan.” [43]

“Specific planning policy requirement” is in practice generally abbreviated to “SPPR”.

23. S.9(6) of the 2016 Act provides that:

“Where the proposed strategic housing development would materially contravene the development plan …… other than in relation to the zoning of the land, then the Board may only grant permission ……….. where it considers that, if section 37(2)(b) of the Act of 2000 were to apply, it would grant permission for the proposed development.”

S.37(2)(b) PDA 2000

24. S.37(2)(b) PDA 2000 provides, as relevant, that

“ ….. the Board may only grant permission ….. where it considers that—

(i) the proposed development is of strategic or national importance,

(ii) ………..

(iii) permission for the proposed development should be granted having regard to … guidelines under section 28, …

or

(iv) permission for the proposed development should be granted having regard to the pattern of development, and permissions granted, in the area since the making of the development plan.”

S.28 PDA 2000 - Guidelines & SPPRs

25. S.28(1) & (2) PDA 2000 empower the Minister to issue guidelines - often referred to as “planning guidelines” and as “s.28 guidelines” - as to the exercise of planning functions, to which guidelines planning authorities and the Board shall have regard in the performance of their functions. The Height Guidelines 2018, addressed below, are such guidelines.

26. S.28(1C) PDA 2000 provides that such guidelines:

“…… may contain specific planning policy requirements with which planning authorities, … and the Board shall, in the performance of their functions, comply.”

McDonald J in O’Neill [44] observed that S.28(1C) “imposes a very clear mandatory requirement that, where specific planning policy requirements are specified in ministerial guidelines, they must be complied with.”

SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 & Ironborn’s Reliance Thereon

27. SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 provides:

“It is a specific planning policy requirement that where;

(A) 1. an applicant for planning permission sets out how a development proposal complies with the criteria above; [45] and

2. the assessment of the planning authority [46] concurs, taking account of the wider strategic and national policy parameters set out in the National Planning Framework [47] and these guidelines;

then the planning authority may approve such development, even where specific objectives of the relevant development plan or local area plan may indicate otherwise.” [48]

McDonald J in O’Neill observed that:

“It is clear from the text of SPPR 3(A) that its application is dependent upon (a) an applicant for planning permission setting out how a development proposal complies with the “criteria above” and (b) an assessment by the Board concurring with that conclusion. The relevant criteria for this purpose are set out in para.3.2 of the Building Height Guidelines. Paragraph 3.2 requires that an applicant “shall demonstrate to the satisfaction of the [the Board] that the proposed development” satisfies a number of criteria which are set out over the next three pages of the Guidelines. ….. these criteria must be satisfied if SPPR 3(A) is to apply.” [49]

28. Ironborn’s statutory [50] Material Contravention Statement [51] invokes SPPR3 as a basis for a grant of permissions despite the proposed material contravention of the Development Plan as to building height.

S.37(2)(c) PDA 2000 - Reasons, Intermingling of Reasons & Discretion to Refuse Certiorari

29. S.37(2)(c) PDA 2000 requires that in granting a permission in reliance on s.37(2)(b) PDA 2000, the Board must give “the main reasons and considerations for contravening materially the development plan.” It is not uncommon that, in justifying permission despite material contravention, the Board, as it did in this case, will invoke more than one of s.37(2)(b)(i) to (iv) PDA 2000. S.37(2)(c) requires that the Board give its reasons for reliance on each.

30. Clonres/Conway #2, [52] Ballyboden TTG [53] and Jennings [54] are authority that, where the Board invokes more than one of the criteria found in s.37(2)(b)(i) to (iv), flawed reliance on one may not be fatal to the permission if reliance on one or more others is valid. That, in turn, depends on satisfaction of two requirements - such satisfaction to be objectively discernible from the impugned decision:

· First, it depends on the reasons given by the Board for its decision as to reliance on those criteria being discernibly discrete in their application to the criterion upon which reliance is flawed on the one hand and, on the other, the valid criteria. Or, to put it another way, while “intermingling” by the Board of its reasons for reliance on those criteria is not a problem as long as reliance on all criteria is valid, where reliance on one criterion is flawed, that flawed reliance can be severed and the permission saved if the reasons given for the flawed reliance on that criterion can be severed from the reasons given for the valid reliance on the other criteria. On the facts that first question was answered against the Board in Clonres/Conway #2.

· Second, survival of the impugned decision depends on whether, shorn of the invalid reason and on viewing the valid reasons remaining after severance, and bearing in mind the significance of material contravention of the Development Plan, the Board can be read as having regarded the remaining valid reasons as sufficient to justify the material contravention in question.

31. That second question was answered against the Board in Ballyboden TTG:

“282. The Board urges that if the Board erred in its application of s.37(2)(b)(iii) I should refrain from quashing the impugned decision on the basis that the Board’s reasons given pursuant to s.37(2)(b)(i)(ii) & (iv) PDA 2000 survive and suffice. The analogy of severance of invalid planning conditions and Aherne v An Bord Pleanála [55] are called in aid. I respectfully reject that submission.

283. Aherne is authority that a “peripheral and insignificant” planning condition is severable if invalid and it is demonstrated that the Board would have granted the relevant permission subject only to the other conditions. While material contravention permissions by the Board are by no means unusual in practice, nonetheless as disapplications of democratically-adopted development plans, they are no small thing, are legally exceptional and should arise only for substantial reason - a consideration reflected in the obligations imposed on the Board by s.37(2) PDA 2000. As a matter of law I should not lightly conclude that any reason given pursuant to s.37(2)(b) PDA 2000 is “peripheral and insignificant” or in any degree analogous to “peripheral and insignificant. The Board has not stated that any individually its [56] reasons pursuant to s.37(2)(b) sufficed to justify its decision or whether the cumulative weight of some or all sufficed for that purpose and I do not consider that I can make an inference to that effect. Accordingly the Board’s argument in this regard fails.

32. In Jennings, despite the invalidity of the Board’s reliance on ‘strategic and national importance’ to justify material contravention, both the questions stated above were answered in the Board’s favour and certiorari was refused accordingly. In passing, I note that since the hearing in this case similar reasoning in a somewhat different context saved the impugned decision in Murtagh. [57]

33. The question of intermingling of reasons in the application of s.37(2)(b) and (c) PDA 2000 arose in this case in a somewhat unusual way. The Board’s application of s.37(2)(b)(iv) as to precedent permissions nearby was not impugned in these proceedings. The Board did not plead the point that even if the Board’s application of s.37(2)(b)(i) and (iii) was invalid, its application of s.37(2)(b)(iv) sufficed to justify the material contravention. However Fernleigh, in its written submissions, specifically as to the issue of the Board’s application of s.37(2)(b)(i) - the strategic nature of the Proposed Development - conceded that there was no intermingling of reasons and Fernleigh all but volunteered that certiorari was unlikely on that issue given remaining valid reasons. [58]

34. The Board’s written submissions unsurprisingly took up the issue - but again in the specific context of the challenge to the Board’s application of s.37(2)(b)(i) as to the strategic nature of the Proposed Development. The Board submitted that, having regard to Jennings [59] and to the discretionary nature of remedies in judicial review and as the Board had given valid reasons for its invocation of and had validly invoked s.37(2)(b)(iii) and (iv) PDA 2000 and had not Intermingled its reasons for invoking s.37(2)(b)(i), (iii) and (iv) PDA 2000 respectively:

“…….. the conclusion reached by the Board in relation to section 37(2)(b)(i) can be excised such that the remainder of the justification of the grant of permission despite material contravention survives, such that the Court should refuse certiorari on this ground.”

35. The respective oral submissions at trial adverted to, but did not expand or extrapolate, the written submissions in this regard. The oral submissions too were confined to the discretion to decline certiorari in the event that the Board’s reliance on, specifically s.37(2)(b)(i) as to the strategic nature of the proposed development was invalid. Notably, Fernleigh did not concede and the Board did not argue that if the Board’s invocation of s.37(2)(b)(iii) as to reliance on the Height Guidelines 2018, and specifically §3.2 and SPPR3 of those guidelines as to daylight provision and public transport, was invalid, certiorari should likewise be declined on discretionary grounds. It may be that standing on its invocation of s.37(2)(b)(iii) was a prudent tactical course by the Board. Perhaps the Board took the view that if it lost those arguments as to the important matters of daylight provision in the apartments and availability of high capacity public transport well-serving 445 Apartments, the decision as to material contravention was unlikely be saved from certiorari on a discretionary basis by the single swallow of a permission for 200 units, at heights of up to 7 storeys, 300 metres east of the Site (a question canvassed obiter but not answered in Ballyboden TTG [60]). Also, the Board may have noted that in Jennings, while an invalid reason for invoking s.37(2)(b)(i) as to the strategic nature of the proposed development was excised, the permission was nonetheless quashed on a ground as to SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 and Daylight Analysis. But all this is a bit speculative - what matters is that, whatever its reason, the Board did not argue that its decision under s.37(2)(b)(iv) should save the Impugned Permission from any infirmity of its invocation of s.37(2)(b)(iii).

INSPECTOR’S REPORT - MATERIAL CONTRAVENTION AS TO HEIGHT & SPPR3 OF THE HEIGHT GUIDELINES

36. Save to the following extent, I will consider the Inspector’s report when considering each ground of challenge to the Impugned Permission.

37. As stated above, as the Inspector and the Board found a material contravention as to height, given the proposed height of up to 8 storeys, [61] it is not necessary to interrogate the detail of Development Plan Policy UD6: Building Height Strategy. The Inspector [62] identified considerations relevant should the Board be minded to materially contravene the Development Plan as to height in exercise of its powers under s.9(6) of the 2016 Act and s.37(2)(b) PDA 2000. Those considerations include that the Proposed Development is of strategic or national importance. I will address this issue of strategic or national importance when considering the relevant ground.

38. Those considerations relevant to permitting material contravention also include the Building Height Guidelines 2018 [63] to the effect that building heights must be generally increased in appropriate urban locations, subject to the criteria set out in §3.2 of the guidelines. This passage [64] is cross-referenced to §12.4 of the Inspector’s report, which makes it apparent that, in invoking the criteria set out in §3.2, the Inspector is applying SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018. Applying SPPR3 arises only where the Board is satisfied that a proposed development meets those §3.2 criteria. §12.4.17 of the Inspector’s report reads:

“SPPR 3 of the Height Guidelines states that where a planning authority is satisfied that a development complies with the criteria under section 3.2 of the guidelines, then a development may be approved, even where specific objectives of the relevant development plan or local area plan may indicate otherwise (I refer the Board to Section 12.3 ‘Material Contravention’ for further consideration of this issue as it relates to the Development Plan). In this instance the Building Height Strategy of the Development Plan set a notional limit of 6 storeys on this site. As such the criteria under section 3.2 of the Building Height Guidelines, provide a relevant framework within which to assess the merits, or otherwise, of this proposed development.”

39. Amongst the §3.2 criteria for the invocation of SPPR3 identified by the Inspector are that

o the Site be well served by high capacity public transport. [65]

o the proposed development maximise access to natural daylight. [66] In this regard, the Inspector [67] cross-references his consideration of the daylight issue at §12.5 of his report.

40. In summary, and while he did so in a somewhat obliquely-expressed way and could have done so more explicitly, I am satisfied that, interpreting his report as a whole, the Inspector invoked SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 in invoking s.37(2)(b)(iii) PDA 2000 as to ministerial guidelines issued under s.28 PDA 2000. Thereby, he invoked also the §3.2 criteria for the invocation of SPPR3 - including those as to public transport capacity and as to daylight provision to apartments. This illuminates the significance of the Board’s explicit invocation of §3.2. In fairness to all concerned, and quite properly, this was not in dispute. But it seems to me useful to state the position given that the Inspector was somewhat oblique on this issue and given it bears considerably on the consideration of the grounds of challenge as to daylight provision and public transport capacity.

1 - DAYLIGHT [68]

Daylight - Pleadings & Submissions

41. Fernleigh pleads that the Impugned Permission is invalid as contravening the daylight requirements of both §3.2 of the Height Guidelines 2018 (a criterion for applying SPPR3) and the Apartment Design Guidelines 2020, in breach of s.9(3) of the 2016 Act. It pleads that the Proposed Development does not comply with the BRE Guide and/or the Daylighting Code (to which §3.2 required “appropriate and reasonable regard”) and/or contains material errors of fact. Fernleigh’s pleadings do not, but its submissions do, assert contravention of s.28 PDA 2000. However it seems to me clear, given the terms of s.9(3) of the 2016 Act, that the plea necessarily implies reliance on s.28 PDA 2000.

42. In essence, the allegation is of misapplication by the Board of SPPR3, allowing the material contravention as to height, in that the §3.2 criteria for its application were not satisfied. [69] Fernleigh plead and submit 4 legal errors - each allegedly fatal to the Impugned Permission:

a. Ironborn in its Daylight, Sunlight and Overshadowing Report (the “Light Report” [70] ) submitted with its planning application, and the Board in its Inspector’s report, erroneously applied to combined living /kitchen/dining (“LKD”) rooms a 1.5% “Average Daylight Factor” (“ADF”) instead of the applicable 2% ADF and/or failed to justify a 1.5% ADF. The Inspector accepts this incorrect standard: “I am satisfied that the alternative value of 1.5% for the living/kitchen/dining areas is appropriate”. [71]

b. Ironborn did not clearly identify any non-conformity with the BER Guide/Daylighting Code and its extent - as required by §3.2 of the Height Guidelines - see Walsh. [72] Instead, it asserted 97% conformity by applying the wrong standard. The Inspector’s ad hoc calculation based on a 2% ADF does not avail the Board (even if it had relied upon it) as the obligation to identify the non-conformity rests on the developer, presumably so that the public will participate on the basis of correct standards.

c. §3.2 of the Height Guidelines requires that, as to any identified non-conformity with the BER Guide/Daylighting Code, “a rationale for any alternative, compensatory design solutions must be set out”. The Inspector cites “compensatory design solutions” but none of them were set out by Ironborn as such solutions. So they are irrelevant considerations for the purposes of §3.2.

d. The Inspector took account of another irrelevant consideration - that the Proposed Development is of BTR apartments. Residents of such accommodation are entitled to the same daylight as those in other forms of accommodation and no different standard applies or has been identified by the Board.

43. The Board pleads and submits that:

a. Ironborn justified its application of the 1.5% ADF standard instead of the 2% ADF standard.

b. In any event, the Board considered the Proposed Development “against the 1.5% and 2% ADF standard” and even at 2% overall compliance was high.

c. The Board did identify the extent of non-compliance with the 1.5% and 2% ADF standards. Ironborn’s allegation of failure to do so is abstract, general and based on incomplete quotation of the Inspector’s Report and the materials before the Board.

d. The Board accepted the compensatory design solutions proffered by Ironborn and their rationale, as it was entitled to in its discretion and as a matter of planning judgment. Fernleigh’s challenge is essentially merits-based, is based on selective reading of the Inspector’s report and on reading it “as invalid rather than valid (i.e., the opposite of the approach that should be taken”.

Daylight - Introduction, §3.2 & SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018 & Apartment Guidelines

44. All agree that:

· The Proposed Development is in material contravention of the Development Plan as to height.

· The validity of the Impugned Permission depends on the application of s.9(3) of the 2016 Act [73] (which allows material contravention on certain conditions), s.28 PDA 2000 [74] (which requires compliance with SPPRs [75]), and SPPR3 of the Height Guidelines 2018.

· SPPR3 in effect allows the Board to override certain Development Plan building height constraints and to do so in favour of increased height in appropriate urban locations.

· Application of SPPR3 in turn depends on satisfaction of the “Development Management Criteria” set out in §3.2 of the Height Guidelines 2018 (“§3.2”). It is not merely a matter of having regard to these criteria or to the Height Guidelines 2018 more generally. These §3.2 criteria must be satisfied before SPPR3 can lawfully be invoked and applied - Jennings. [76]

· §3.2 requires that, in making a planning application proposing increased building height, [77] the planning “applicant shall demonstrate to the satisfaction of the (the Board), that the proposed development satisfies (certain) criteria”. Those criteria include the following “At the scale of the site/building”: [78]

o “The form, massing and height of proposed developments should be carefully modulated so as to maximise access to natural daylight, ventilation and views and minimise overshadowing and loss of light.

o Appropriate and reasonable regard should be taken of quantitative performance approaches to daylight provision outlined in guides like the Building Research Establishment’s ‘Site Layout Planning for Daylight and Sunlight’ (2nd edition) or BS 8206-2: 2008 - ‘Lighting for Buildings - Part 2: Code of Practice for Daylighting’.

o Where a proposal may not be able to fully meet all the requirements of the daylight provisions above,

§ this must be clearly identified and

§ a rationale for any alternative, compensatory design solutions must be set out,

§ in respect of which the planning authority or An Bord Pleanála should apply their discretion, having regard to local factors including specific site constraints and the balancing of that assessment against the desirability of achieving wider planning objectives. Such objectives might include securing comprehensive urban regeneration and or an effective urban design and streetscape solution.” [79]

· In short, the validity of the Impugned Permission turns, on the facts of this case, on compliance with the daylight criteria of §3.2 as set out above.

· Ironborn’s Material Contravention Statement [80] in this regard essentially referred to its Light Report.

45. It seems to me that the adjectival and other emphases in §3.2 as to daylight are striking - access to natural daylight is to be maximised, loss of light is to be minimised and the need to justify departures arises where “all” the requirements are not “fully” met. They are consonant with the recognition of the importance of daylight in apartments - to which recognition I will refer below.

46. I will refer to the Building Research Establishment’s [81] ‘Site Layout Planning for Daylight and Sunlight’ (2nd edition) as the “BRE Guide” and to BS 8206-2: 2008 - ‘Lighting for Buildings - Part 2: Code of Practice for Daylighting’ [82] as the “Daylighting Code”.

47. No question arises in this case of application of an SPPR of the Apartment Design Guidelines 2020, [83] and so, for present purposes, they are guidelines to which the Board was obliged only to have regard. Nonetheless, they cover some of the same Daylight/Sunlight ground as, and do so in terms, as one would expect of a coherent suite of planning guidelines, consistent with the Height Guidelines 2018 and SPPR3. So they bear some review here. The Apartment Design Guidelines 2020 make the important, general and indisputable observation that,

“the amount of sunlight [84] reaching an apartment significantly affects the amenity of the occupants.” [85]

In this they echo the BRE Guide, which says:

“People expect good natural lighting in their homes ..” [86]

48. In similar vein, as to content of planning applications and in terms echoing those of the Height Guidelines 2018, the Apartment Design Guidelines 2020, state:

“6.5 The provision of acceptable levels of natural light in new apartment developments is an important planning consideration as it contributes to the liveability and amenity enjoyed by apartment residents. In assessing development proposals, planning authorities must however weigh up the overall quality of the design and layout of the scheme and the measures proposed to maximise daylight provision with the location of the site and the need to ensure an appropriate scale of urban residential development.

6.6 Planning authorities should have regard to quantitative performance approaches to daylight provision outlined in guides like the (BRE Guide and the Daylighting Code of Practice) when undertaken by development proposers which offer the capability to satisfy minimum standards [87] of daylight provision.

6.7 Where an applicant cannot fully meet all of the requirements of the daylight provisions above, this must be clearly identified and a rationale for any alternative, compensatory design solutions must be set out, which planning authorities should apply their discretion in accepting taking account of its assessment of specific. [88] This may arise due to a design constraints associated with the site or location and the balancing of that assessment against the desirability of achieving wider planning objectives. Such objectives might include securing comprehensive urban regeneration and or an effective urban design and streetscape solution.”

That the Apartment Design Guidelines 2020 in substance echo the daylight requirements of the Height Guidelines 2018 will be readily apparent from the foregoing.

49. Humphreys J in Walsh, [89] articulated the importance of the issue of daylight in apartments:

“The clear language of the ministerial guidelines sends the message that the reasonable exercise of planning judgement requires that an enthusiasm for quantity of housing has to be qualified by an integrity as to the quality of housing. Among other obvious reasons, and speaking about developments generally rather than this one particularly, such an approach reduces the prospect of any sub-standard, cramped, low-daylight apartments of today becoming the sink estates and tenements of tomorrow.” [90]

My purpose in citing this excerpt is not to comment on or impugn the design of the Proposed Development by reference to the prospect identified by Humphreys J - it is to articulate the general importance of natural light in apartments to the amenity of their occupants, as recognised in the various guidelines.

Daylight - BRE Guide, Daylighting Code & Caselaw

50. The caselaw is significant to an understanding of this ground of challenge. It has proceeded, inter alia, from disputes as to the significance of the concepts of “criteria” and “appropriate and reasonable regard” in SPPR3, §3.2 of the Building Height Guidelines and the terms of the BRE Guide. The most recent authority is Jennings, [91] which considered Atlantic Diamond, [92] Walsh, [93] and Killegland. [94]

51. In Killegland, and by way of contrast with the generally light burden to “have regard” to something, Humphreys J observed that “ an intensifier such as to have … “appropriate and reasonable regard” (as in the relevant SPPR in the Building Heights Guidelines) … generally connotes an additional degree of weight to be given to the matter to which regard is to be had, with a general enhancement of the level of reasons that have to be given for not affording such weight.” He had said in Atlantic Diamond, [95] that “The obligation is to have “appropriate and reasonable regard” to guides of this nature, and regard would not be appropriate or reasonable unless one considered all of the material and acted in conformity with it or, if not, explained why.”

52. The BRE Guide [96] and the Daylighting Code combine to set quantitative [97] standards explicitly as minima for adequacy of daylight in residential units. They are measured in terms of an ADF - a unit which measures the overall amount of daylight in a space using a “standard overcast sky” [98] as a reference point. [99] Generally (the proper application of the standards is contested), the applicable ADF minima are:

· 1% for bedrooms,

· 1.5% for living areas and

· 2% for kitchens.

Importantly, in multi-use rooms the highest applicable use standard applies. [100] So, for example, in a combined living/kitchen/dining (“LKD”) room, the applicable minimum ADF is 2%.

1% ADF equates to 1% of outdoor unobstructed illuminance. 5% ADF equates to a “well daylit” space. 2% equates to a “partly daylit” space. Below 2%, the room will look dull and electric lighting is likely to be turned on.

53. Consistent with this understanding of the Daylighting Code, the BRE Guide says:

“The amount of daylight a room needs depends on what it is being used for.” [101]

“Living rooms and kitchens need more daylight than bedrooms.” [102]

“If a predominantly daylit appearance is required, then the ADF should be 5% or more if there is no supplementary electric lighting, or 2% or more if supplementary electric lighting is provided. There are additional recommendations for dwellings of 2% for kitchens, 1.5% for living rooms and 1% for bedrooms. These additional recommendations are minimum values of ADF which should be attained even if a predominantly daylit appearance is not achievable.” [103]

So, the recommendations of 2% for kitchens, 1.5% for living rooms and 1% for bedrooms are minima which do not achieve “a predominantly daylit appearance” but at 2% “a predominantly daylit appearance” can be achieved by use of supplementary electric lighting. The BRE Guide unsurprisingly comments that, while the minima can be used as targets for obstructed situations, better is desirable. [104]

54. The BRE Guide, though explicitly using the word “minimum” to describe its numerical guidelines, nonetheless states that:

“It is purely advisory and the numerical target values within it may be varied to meet the needs of the development and its location. Appendix F explains how this can be done in a logical way, while retaining consistency with the British Standard recommendations on interior daylighting.” [105]

“The advice given here is not mandatory and the guide should not be seen as an instrument of planning policy; its aim is to help rather than constrain the designer. Although it gives numerical guidelines, these should be interpreted flexibly since natural lighting is only one of many factors in site layout design (see Section 5). In special circumstances the developer or planning authority may wish to use different target values.” [106]

55. In its own terms all that is clear enough. The interpretative difficulty arises where, as in §3.2 of the Height Guidelines which sets criteria for the application of SPPR3, the BRE Guide is explicitly adopted, not merely “as an instrument of planning policy” (a role it itself explicitly disavows) to which regard must be had - but as one to which “appropriate and reasonable regard” must be had, as that phrase is explained in Killegland and in Atlantic Diamond. In other words, the Height Guidelines explicitly adopt the BRE Guide for a purpose to which the BRE Guide explicitly says it is unsuited and, having done so, imposes a higher than usual duty of regard to it. Further, it does so in a context in which that regard operates as a mandatory criterion for the application of an SPPR which overrides Development Plans. In such circumstances, interpretive difficulties are, if not inevitable, at least predictable. It is entirely unsurprising that, from their different and partisan perspectives, developers emphasise the merely advisory nature and inherent flexibility of the BRE Guide and its ADF standards, whereas objectors emphasise the statutory context in seeking to characterize the BRE Guide and its ADF standards, at least where application of SPPR3 to a material contravention is concerned, as little less than mandatory. In this regard one can only repeat the importance which Collins J ascribed in Spencer Place [107] to careful and clear drafting of planning guidelines - not least where SPPRs are concerned and repeat also that, while incorporation by reference is a very useful drafting technique, it always requires careful consideration of the content of the document thus incorporated.

56. The ADF standards set in the BRE Guide are not merely explicitly minima, they are quantified minima which do not achieve a “predominantly daylit appearance”. Notably, the BRE Guide envisages departures from those numerical minima:

· in “special circumstances”. (That inevitably prompts the question: are the circumstances special and what is special about them? The Board has not suggested that the examples of special circumstances [108] given in the BRE Guide as justifying lesser targets apply in the present case - either in terms or by analogy. Nor were any such special circumstances identified to the Board or to the Court.)

· in accordance with Appendix F.

· in a logical way.

· while retaining consistency with the Daylighting Code (which sets the ADF standards).

So, even in its own terms, the flexibility of the BRE Guide is not carte blanche.

57. Generally, (and this is no criticism of what was originally written and intended as a non-statutory guide for a use very different to that to which the Height Guidelines have put it) it seems to me that the word “interpreted” in the indication that the “numerical guidelines, … should be interpreted flexibly”, is properly to be read as “applied”. The Board’s counsel agreed. [109]

BRE Guide ADF Standards - applicable to Apartments?

58. The Statement of Grounds records that Ironborn asserted, in its Light Report that the BRE Guide does not apply or is applied in some generally attenuated way by “the majority of councils in Ireland and the UK”, to apartment developments as opposed to “traditional house layout and room usage” and that “This has been confirmed as acceptable and standard practice by the author Dr Paul Littlefair”. The full relevant text of the passage of the Light Report is as follows:

“We note that for apartment developments the majority of councils in Ireland and the UK accept the lower value of 1.5% assigned to living rooms to also include those with a small food preparation area (kitchen) as part of this space. The higher kitchen figure of 2.0% is more appropriate to a traditional house layout and room usage. The use of a reduced value accepted by Local Authorities is still compliant within the terms of the guidelines. This has been confirmed as acceptable and standard practice by the author Dr Paul Littlefair. We have thus used the minimum values of 1.0% for bedrooms and 1.5% for the Living room spaces.”

59. In effect, this passage purports to disapply the 2% standard to LKD rooms in apartments generally - as opposed to on foot of any specific characteristics of the Site, its locale or the Proposed Development. It falls little short, if at all, of baldly stating that the 2% standard does not apply to LKD rooms in apartments. For reason which follow, I reject that assertion.

60. I should recognise that Counsel for the Board, correctly in my view, placed little or no reliance on the reference in that that passage to the view of Dr Littlefair. He also agreed that the BRE Guide does not suggest that the treatment of daylight issues is to be attenuated as to apartments. [110] He was, as he was entitled to be, more equivocal as to the relevance of the rest of that passage - calling attention to the explicit invocation in the BRE Guide of flexibility, though conceding that the attitude of UK planning authorities was of little relevance. However, in my view, Fernleigh is correct in submitting that “It is on the basis of this analysis that the Developer calculated its purported levels of compliance.” [111]

61. The Inspector recites [112] this passage of the Light Report in a section of his report which the Board’s submissions describe [113] as his “analysis”. But he does so without comment, analysis or scrutiny and, importantly, he does so in support of his own conclusion that he is “satisfied that the alternative value of 1.5% for the living/ kitchen/dining areas is appropriate”. Indeed he later says, clearly referring to this passage of the Light Report, “While the report does not apply a target of 2% for LKDs (a target of 1.5% is applied), justification is set out for this.” So I find, despite the Board’s disavowal of it at trial, that the Inspector did rely on this passage in the Light Report and did so, in at least considerable degree, in deeming a target of 1.5% ADR for LKD rooms appropriate. In my view, that reliance was in error - indeed, in error for the very reasons for which the Board did not rely on this passage at trial.

62. The Board’s written submissions do not engage with the issue. So, despite counsel’s concession, I should record the reasons why these observations by Ironborn are of minimal weight, if any weight at all, are as follows:

· First, a sweeping, unsubstantiated and likely unverifiable assertion as to what the “majority of councils in Ireland and the UK” habitually do or do not do, by way of the disapplication of a standard, inevitably invites healthy scepticism. That is especially so as to a standard to which “appropriate and reasonable regard” must be had in overriding planning policy as expressed in a Development Plan. At very least, attributing any weight to it would require that the planning-decision maker have independent verification of, or itself be in a position to confirm, the proposition.

· Second, it seems inevitable that the “majority of councils in Ireland and the UK” habitually apply the BRE Guide in contexts entirely unaffected by SPPR3 and the legal context in which SPPR3 sits.

· Third, the citation of the views of Dr Littlefair is entirely unattributed as to precise source or content or context, as to when or to whom they were expressed, in answer to what question or whether in public. While the rule against hearsay does not, of course, apply and weight is a matter for the Board, nonetheless some statements are just clearly and self-evidently weightless.

· Fourth, there is no recognition in the Light Report of SPPR3 or §3.2 of the Height Guidelines 2018 - indeed of the Height Guidelines at all or even of the Apartment Design Guidelines - much less of the legal context in which they sit - or that the BRE Guide has been transmuted by Irish law into the very “instrument of planning policy” which Dr Littlefair, explicitly in the BRE Guide, intended it not to be.

· Fifth, there is no evidence that Dr Littlefair was aware of SPPR3 and the legal context in which it sits - or that his BRE Guide has been transmuted by Irish law into the very “instrument of planning policy” which he intended it not to be.

· Sixth, even if he was so aware, his interpretation of his BRE Guide, while relevant is, by reason of his authorship of it, no more authoritative than any other interpretation - St Kevin’s GAA. [114] However, even to the extent it is relevant, in the absence of direct and reliable expression of his view, as opposed to a highly general aside, clearly no weight of consequence could reasonably be placed on it. In fairness, counsel for the Board [115] correctly placed “little or no reliance” on the fact that this was interpretation attributed to Dr Littlefair. However he did not elaborate on his assertion that the Inspector placed “little or no reliance” on it and, as I have said, the passage of the Inspector’s report [116] which cites this content generally is the passage at the end of which he draws the conclusion that “the alternative value of 1.5% for the living/kitchen/dining areas is appropriate”.

· Seventh, on my perusal of the BRE Guide there is no suggestion of such a distinction between apartments and houses. The necessarily objective interpretation of the BRE Guide discloses no such distinction. Had such a major point of distinction been intended, it would have had to have been expressed in the BRE Guide and it is not. Indeed, the illustrative photographs in the BRE Guide make clear that it is very much intended for application to apartments. That makes sense as it is primarily in the case of intensive apartment blocks, as opposed to extensive housing estates, that adequacy of daylight is an issue.

· Eighth, §6.6 and §6.7 of the Apartment Guidelines 2020, set out above, are perfectly clear that,

o the BRE Guide and the Daylighting Code apply to apartment developments.

o the aim is to “fully meet” their requirements.

o where they cannot be fully met “this must be clearly identified and a rationale for any alternative, compensatory design solutions must be set out”.

There is no recognition of any of this in the Light Report - which, as I have said, does not even mention the Apartment Guidelines 2020. But the Apartment Guidelines 2020 are clear as to the underlying relevance of the BRE Guide and the Daylighting Code to apartment developments.

Of course, these are guidelines to which planning decision-makers must have regard - as opposed to the obligation of appropriate and reasonable regard imposed by §3.2 of the Height Guidelines 2018 as to the BRE Guide and the Daylighting Code when it comes to satisfying criteria for the application of SPPR3 - which obligation was recognised as weightier in Atlantic Diamond. [117] And, whatever regard the Board must have, by inevitable implication planning applicants and their expert advisors must in practice have like regard.

63. The BRE Guide and the Daylighting Code apply to apartments just as much as to any other form of residential development. I reject any contrary suggestion. The Board’s apparent lack of even curiosity, much less analysis, as to these assertions in the Light Report is, putting it at its least, disappointing in light of the expectation articulated by O’Donnell J in Balz [118] (and in other cases I cite below) that the Board fulfil an “important public function” as “an independent expert body carrying out a detailed scrutiny of an application in the public interest, and at no significant cost to the individual”. While “detailed scrutiny” of a planning application does not require exhaustive exploration of its every nook and cranny, the assertion that the BRE Guide is inapplicable to apartments in an important respect such as the applicability of ADF standards falls well within the requirement.

Developer’s Failure to Demonstrate Compliance - Walsh

64. In Walsh, [119] the Board granted an SHD permission in material contravention of the applicable development plan as to building height. By s.9(6) of the 2016 Act, the validity of that permission depended on satisfaction of the requirements of s.37(2)(b) PDA 2000.

65. Of some note given it is also argued in this case, and presumably on foot of emphasis on the requirement in SPPR3 that the developer set out how its development proposal complies with the §3.2 criteria and the stipulation in §3.2 that the developer “shall demonstrate” satisfaction of those criteria, Mr Walsh asserted that the developer had failed to provide the Board with material from which the Board could find compliance with the §3.2 criteria and misconstrued the Height Guidelines, therefore failing to provide a basis for material contravention. However Humphreys J held:

“But a failure by a developer to provide material, in and of itself, is not generally a basis for certiorari. It is true that in certain contexts such as a defect in the application form itself or some other document essential to jurisdiction, any failing by the developer or applicant in a process might be a ground for certiorari as such, but in the context here, any shortcomings in the developer’s material would only become a problem if they flow through into the decision-maker’s analysis. Thus it is the approval of the application by the decision-maker without adequate material, not a failure by the developer to furnish material, that is a ground for certiorari [120] ……. Applicants seem to misunderstand this conceptual point with almost predictable regularity, and the present case furnishes no exception.”

Counsel for Fernleigh suggested this observation by Humphreys J was a “side-wind” - the last sentence of the passage makes clear it was not.

66. It seems to me that the underlying rationale of the requirements of the Developer specifically made in SPPR3 and §3.2 is to ensure that the Board has adequate materials and reasoning before it. A developer who fails to meet those requirements clearly runs a risk of an adverse decision by the Board. But if by other means the Board has adequate materials and can engage in reasoning adequate to support a decision to grant permission, such that the shortcomings in the developer’s materials do not flow into the Board’s analysis and if those shortcomings have not resulted in procedures unfair to other participants in the process (for example by way of their not being position to respond to materials and reasoning not proffered by the developer), I respectfully agree with Humphreys J, that the developer’s failure is not a ground for certiorari. The requirements of fair procedures vary with circumstances and certiorari would require demonstration of real and substantive, as opposed to formal, unfairness - Wexele. [121] While I do not rule out the possibility of exceptions, it is difficult to see how, generally, justice would require certiorari where the developer’s error has not flown into the Board’s analysis.

The Applicable ADF Standard for LKD Rooms

67. As to the ADF standard for LKD rooms applicable by virtue of and on a correct interpretation of the BRE Guide and the Daylighting Code, Humphreys J put it pithily in Walsh: “1.5% is not the standard, the standard is 2%”. In Atlantic Diamond, Humphreys J noted, as to the Daylighting Code, that “insofar as kitchens are combined with living rooms in the proposed development, the appropriate ADF would be the higher of the 1.5% standard for living rooms and the 2% standard for kitchens ....”. [122] In Jennings it was said that “The Daylighting Code standard for ADF in LKD spaces is 2%.” [123] The position in this regard is entirely clear. The Inspector and the Board erred in applying 1.5%.

Appropriate & Reasonable Regard to the BRE Guide and to the BS

68. As noted above, by the criteria set by §3.2 of the Height Guidelines include that before the Board may lawfully apply SPPR3 it must have paid “appropriate and reasonable regard” to “quantitative performance approaches to daylight provision outlined in guides like” the BRE Guide and the BS. As I have noted, in Killegland [124] Humphreys J, citing SPPR3, described “Appropriate and reasonable” as an “intensifier” of the more common “have regard to” obligation. That intensifier “generally connotes an additional degree of weight to be given to the matter … with a general enhancement of the level of reasons that have to be given for not affording such weight”. In this he echoed his view, expressed in Atlantic Diamond, [125] of an argument that the BRE Guide is not mandatory:

“ …. the reference to guidelines like the two identified certainly includes having regard to both of the two guides identified …” [126]

“The mandatory s.28 guidelines require appropriate and reasonable regard to be had to the BRE guidelines. That takes them well out of the “not mandatory” simpliciter category.” [127]

“The obligation is to have “appropriate and reasonable regard” to guides of this nature, and regard would not be appropriate or reasonable unless one considered all of the material and acted in conformity with it or, if not, explained why.” [128]

“…… if the standards identified are not being complied with, it must be clear why.” [129]

“If, having regard to the relevant guidelines, the developer is not able to fully meet all the requirements regarding daylight provisions, then there are three very specific consequences.

(i). this must be clearly identified;

(ii). a rationale for any alternative compensatory design solutions must be set out; and

(iii). a discretion and balancing exercise is to be applied.” [130] (by the Board).

69. In Atlantic Diamond [131] Humphreys J noted that the developer’s Daylight/Sunlight Study, as to ADF, identified the appropriate guidelines for kitchens at 2% and living rooms at 1.5% and, as recorded above, noted the 2% ADF standard applicable to LKD rooms. [132] He observed: “Unfortunately, the developer applied a 1.5% standard to these combined rooms ...”. [133] He observed of the Daylight/Sunlight Study:

“Crucially, however, that document does not articulate (and neither does the Board) that we are dealing here with combined kitchens and living rooms. They are simply treated as living rooms with no acknowledgment of the problem. That methodological gap in the reasoning would in my view be fatal in itself.” [134]

He continues:

“The second fatal aspect arises when combined with the fact that the British Standard [135] requires that the highest standard of a combined room be applied. That has a direct read-across to the BRE guidelines with which the developer claimed compliance, wrongly on this analysis. The board acted erroneously in endorsing that without properly stress-testing it against the guidelines. If they had done so, the incompatibility would have come to light. Thus the case illustrates a certain laxity in scrutiny, involving in effect the cutting-and-pasting of the developer’s materials by the board without adequate critical interrogation.” [136]

70. In Jennings, [137] as to this passage of Atlantic Diamond, specific note was taken of the Board’s obligation of “active and critical interrogation”, failing which deference to it is not justified - citing Weston [138] to the effect that “Any planning application must be processed with scrupulous rigour.” I have already referred to the need identified by O’Donnell J in Balz for “detailed scrutiny”. In Jennings, [139] Balz was cited as to the importance of such scrutiny to public trust in the planning system and it was said that the Inspector and the Board “are perfectly entitled to accept information tendered by a planning applicant - but only after rigorous scrutiny. And, as to significant issues, both scrutiny and its rigour must be apparent: that is a primary function of an Inspector’s report. It is to contain not merely summary but analysis. Indeed, the very function of expertise, and the reason it is accorded deference, is to exercise judgment in analysis.” And recently Humphreys J in Treascon [140] emphasised “the need for thoroughly independent and detailed expert scrutiny by the statutory decision-maker”.

Identification of Non-Compliance & its Extent & Justification thereof - Walsh

71. In Walsh, Humphreys J repeated that any departure from the BRE Guide and the BS [141] “must be clearly identified” and continued:

“That has to mean identifying the extent of the non-compliance. The concept of identifying the non-compliance is meaningless otherwise because the acceptability of a particular design hinges on its precise form and that of each of its parts. Thus, the impact and assessment of a design depends on the extent of non-compliance with design standards in precise terms. The mere fact that it can be said that some unquantified or not fully quantified part of a scheme does not comply with standards is totally inadequate information for the purposes of a proper and rational evaluation in planning terms or a logically watertight environmental assessment.” [142]

“The need to identify in precise and clear terms the extent of any of failure to meet standards is critical to the evaluation of the acceptability of a project. The extent to which an application falls short of building design standards, and why, is critical to whether a sub-standard design such as this one should be accepted. It can’t be lawfully accepted without first clearly identifying the extent of non-compliance, which wasn’t done.” [143]

Humphreys J said of the inspector:

“ ……… her analysis is based on a false premise. Insofar as she assesses non-compliance, it is by reference to the debased standard proposed by the developer of 1.5% ADF …. She should have started with the applicable standard, which is 2%, then “clearly identified” the extent of the non-compliance, and only at that point interrogated the rationale for such non-compliance by reference to the objective planning considerations referred to in the guidelines. Instead ….. she accepted a basis for “defaulting to a 1.5% value” as a “target” ……. and thus found the 97.3% “complying with standards”. But 1.5% is not the standard, the standard is 2%. Essentially she asked the wrong question and fell into an error of law in doing so. That error occurred at the outset of the analysis - we never even got to whether a departure from standards was really justifiable having regard to the sort of objective planning features envisaged by the guidelines …..” [144]

72. So what are “the sort of objective planning features envisaged by the guidelines”? Humphreys J cites §3.2 of the Height Guidelines to the effect that:

“.. a rationale for any alternative, compensatory design solutions must be set out, in respect of which the planning authority or An Bord Pleanála should apply their discretion, having regard to local factors including specific site constraints and the balancing of that assessment against the desirability of achieving wider planning objectives. Such objectives might include securing comprehensive urban regeneration and or an effective urban design and streetscape solution.”

73. It is important to remember that flexibility in guidelines is not carte blanche to degrade the norm set by guidelines such that the exception becomes the rule - or at least, something less than a true exception. Such an approach tends to degrade norms towards meaninglessness - not least incrementally in repeated decisions and over time. So, as a matter of proper rigour in decision-making, one must start with the norm, assess compliance against it and justify availing of flexibility to depart from it.

74. Remembering to read the Height Guidelines on XJS [145] principles and not as if they were a statute, it seems to me that the foregoing passage from Atlantic Diamond envisages that the Board will balance “local factors including specific site constraints” against “the desirability of achieving wider planning objectives” when considering the adequacy of “compensatory design solutions” in mitigating the ill-effects of failure to meet ADF standards. All three elements are to feature in the decision:

· First, it must be noted that design solutions are “compensatory” - they may do much to mitigate non-compliance but are an “alternative” - not the preferred - solution. The preferred solution - the norm - is compliance with the applicable standard and the provision of daylight accordingly.

· Second, the necessity of non-compliance arises due to “local factors”. [146] That is because the underlying presumption is that the standard is set in the expectation that compliance with it is, in the great majority of planning applications, ordinarily and generally compatible with other standards and “achieving wider planning objectives”. If that were not so, planning policy, as expressed in s.28 guidelines, would be incoherent. While tensions between planning policies are inevitable, incoherence is found only in the last resort. So it is only in a minority of cases and due to specific local factors that a tension arises in practice between adhering to the ADF standards of the BRE Guide/Daylight Code/§3.2 of the Height Guidelines on the one hand and “achieving wider planning objectives”. Of course, tension between ADF standards and “wider planning objectives” is not the only type of tension which may require flexibility and non-compliance with ADF standards “since natural lighting is only one of many factors in site layout design”. [147]

Incidentally, I accept that local factors and constraints and general considerations tend to elide as the former often are functions of the latter. However the main point is that the reasons for reducing ADF standards will include local factors. Though they may be factors arising off-site (e.g. obstruction of light by pre-existing buildings), they will be site-specific in their effect on design. I would not rule out the possibility that non-local factors may in rare cases justify disapplication of standards but such cases will be rare and will require detailed articulation. Any other approach would be destructive of the standards and of the expectation that planning policy, as expressed in s.28 guidelines, is coherent.