Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

High Court of Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> High Court of Ireland Decisions >> Enviromental Trust Ireland v An Bord Pleanala & Ors (Approved) [2022] IEHC 540 (03 October 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IEHC/2022/2022IEHC540.html

Cite as: [2022] 10 JIC 0305, [2022] IEHC 540

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

THE HIGH COURT

JUDICIAL REVIEW

[2022] IEHC 540

2021/856JR

IN THE MATTER OF SECTION 50 OF THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ACT 2000 (AS AMENDED)

Between

Environmental Trust Ireland

Applicant

And

An Bord Pleanála, Limerick City and County Council

Ireland and the Attorney General

Respondents

And

Cloncaragh Investments Ltd

Notice Party

Judgment of Mr Justice Holland delivered 3 October 2022

Contents

Judgment of Mr Justice Holland delivered 3 October 2022. 1

Impugned Permission, Proposed Development, ETI, the Site and its Location. 2

Figure 1 - extract from Planning Application Site Location Map. 5

Figure 2 - extract from Planning Application/WERATN Surface Water Receptors Figure 2.2. 5

Grounds on Which Relief is Sought - Brief Summary. 6

Procedural History of the Judicial Review Proceedings. 6

2016 Act - Introductory Note. 7

Karstic and Fractured Limestone - a note. 8

Site Investigation Report - January 2020. 11

Groundwater Management Plan (Basement Construction Phase) - January 2020. 14

AA Screening Report & NIS - January 2021. 16

ETI Submission - 3 June 2021 - Content. 18

AA - Inspector’s Report & Board’s Decision. 20

Affidavit of Michelle Hayes - sworn 11 October 2021 - filed by ETI 24

Affidavit of Pierce Dillon - sworn 20 January 2022 - filed by the Board. 25

Affidavit of Tim Paul - sworn 28 January 2022 - filed by Cloncaragh. 25

Affidavit of Pierce McGann - sworn 28 January 2022 - filed by Cloncaragh. 26

Affidavit of David Drew - sworn 15 February 2022 & Exhibited Drew Report - filed by ETI 28

Affidavit of Michael Duffy - sworn 17 February 2022 - filed by ETI 30

2nd Affidavit of Michelle Hayes - sworn 22 February 2022– filed by ETI 32

Affidavit of Joe Moynihan - sworn 24 February 2022 - filed by ETI 32

2nd Affidavit of Pierce Dillon - sworn 20 January 2022 - filed by the Board. 32

2nd Affidavit of Pierce McGann - sworn 10 March 2022 - filed by Cloncaragh. 33

2nd Affidavit of Tim Paul - sworn 10 March 2022 - filed by Cloncaragh. 34

3rd Affidavit of Michelle Hayes - sworn 29 April 2022 - filed by ETI 36

Ground 1 - FAILURE TO TRANSMIT THE ETI SUBMISSION TO THE COUNCIL. 41

The 2016 Act Scheme for Consideration of Submissions & Consultation with the Planning Authority. 42

ETI Submission - Sequence of Events. 44

The Alleged Absence of Prejudice. 47

Conclusion as to Ground 1 - Failure to send the ETI Submissions to the Council in Time. 57

Ground 2 - CONFLICT BETWEEN PLANNING APPLICATION DRAWINGS. 57

Ground 2 - Other Allegations. 63

Ground 3 - AA- GAPS AND LACUNAE. 63

Pleaded Ground 3 as to AA.. 65

Pleaded Opposition to Ground 3 as to AA.. 66

Ground 2 incorporated in Ground 3 - Plans and Particulars. 66

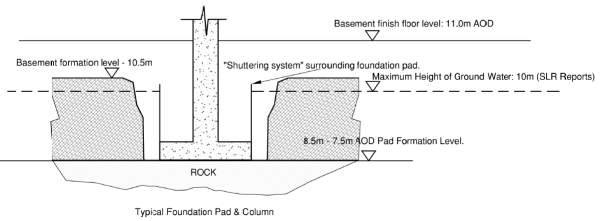

Figure 3 - Construction Management Plan - Typical Foundation Pad & Column. 69

Secant Pile Depth and No Secant Pile Elevations - Breach of Article 297 PDR 2001. 70

Pleadings - Hydrological Route & Failure to Properly Establish Groundwater Levels. 72

Consequences of the Pleading Issue as to Hydrological Route. 76

Disputed Risk of Cement Leaching to Groundwater. 76

Can ETI Raise Cement Leaching and is the Duffy Evidence on it Admissible?. 77

General Issue of Dispute as to the Existence of a Risk. 85

Method of Resolution of Dispute as to Existence of Risk. 90

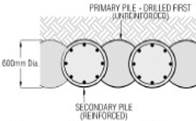

Conclusion on Disputed Risk of Cement Leaching to Groundwater. 94

INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND

Impugned Permission, Proposed Development, ETI, the Site and its Location

1. The Applicant (“ETI”) seeks to quash a decision of the First Respondent (“the Board”) dated 18 August 2021 granting planning permission (“the Impugned Permission”) under the PDA 2000 [1] and the 2016 Act[2] to the Notice Party (“Cloncaragh”) for a Strategic Housing Development (“SHD” and the “Proposed Development”) which may be fairly, if a little incompletely, described as demolition of various disused buildings on site and construction of a 7-storey over basement car park building of 60 Apartment/318 bedspaces of student accommodation and 30 build-to-let apartments on a 0.77 hectare brownfield site at Punches Cross, Limerick (the “Site”) about 1.1km from Limerick City Centre and less than 300m from Mary Immaculate College. Cloncaragh’s SHD Planning Application was made on 30 April 2021. It was accompanied by various reports, plans, and particulars which I describe below.

2. ETI describes itself as an environmental protection NGO and, leaving aside the specifics of its grounds of challenge to the Impugned Permission, its counsel described its “underlying concern” as being that the Proposed Development will give rise to the discharge of on-Site pollutants to groundwater which will thereby reach and adversely impact on the Lower Shannon River SAC [3]. ETI made a submission to the Board in the planning process (the ETI “Submission”) which I describe below.

3. The Board decided to grant the Impugned Permission “generally in accordance with the inspector’s recommendation”. This is not recorded in the Board’s order but is recorded in its direction. So the Board’s Inspector’s reasoning may be imputed to the Board - see Eoin Kelly [4] to the effect that “… the Board order and the board direction can be read with the Board inspector’s report …” and see also Dublin Cycling [5]. That formulation in the Board’s direction suffices to record the adoption of the Inspector’s report save to any extent that the Board’s decision explicitly or by necessary implication differs from that report. [6]

4. For purposes of compliance with the Habitats Directive [7], Cloncaragh submitted an AA [8] Screening Report [9] and an NIS [10]. The Board conducted an AA Screening and concluded that AA was required having regard to the likelihood of significant effects on the Lower Shannon River SAC [11] (the “SAC”). (AA is sometimes termed “Stage 2 Appropriate Assessment” to distinguish it from Stage 1 AA Screening. To avoid confusion [12] I will refer simply to “AA” and “AA Screening” respectively).

5. As to AA, the Board:

· concluded that the information before it was adequate for AA purposes

· adopted the AA done in its Inspector’s report

· concluded

o beyond reasonable scientific doubt

o based on a complete assessment of all aspects of the proposed development

o that the proposed development, by itself or in combination with other plans or projects,

o would not adversely affect the integrity of European Sites [13] in view of their conservation objectives [14].

The Board did an EIA [15] Screening [16] and concluded that EIA was not required.

The Site

6. The Site is not entirely regularly shaped but can be thought of as roughly diamond-shaped, with its northern apex at Punches Cross [17] from which Rosbrien Road runs south east along the north east boundary of the Site and Ballinacurra Road/O'Connell Avenue runs south west along the north west boundary of the site. Cloncaragh’s Groundwater Management Plan [18] by SLR Consulting [19] says [20] that, generally, the Site falls about 6m from north-west to south-east in accordance with the gradient of the local area. Dr Drew [21] appears to agree. However the URS Report 2013 [22] has it sloping “southwest along the general gradient of the surrounding land”. The proposed ground floor levels likewise fall, though less so, from 15.2m OD at the northern apex of the Site, to 14m OD at roughly the south eastern and south western apexes.

7. Again roughly describing matters, the western/north-western half of the Site was occupied by a petrol station from about 1960 to around 2007 - since when the petrol station has been disused [23] and largely demolished. Though the precise locational detail and timing are not entirely clear to me and do not matter, at least some of the Site was a quarry preceding the petrol station. The quarry was backfilled - such that much of the Site is made ground. Substantial disused buildings on Site remain for demolition. 4 underground oil storage tanks in the south/southwest of the site [24] (“the Tanks”) are for removal - 4 others were removed about a decade ago.

8. Figure 2 below, from Cloncaragh’s SHD planning application dated 30 April 2021 ( the “Planning Application”), locates the site with reference to the Dooradoyle/Ballinacurra River, which runs from east to west/north west and discharges to the Shannon/Fergus estuary. Figure 2 depicts the SAC in the Shannon/Fergus estuary and the Dooradoyle/Ballinacurra river. It also depicts the River Fergus SPA [25] (the “SPA”) but it did not feature in argument. At its nearest, the SAC is 1km southwest and/or west of the Site [26]. Figure 2 also depicts what Cloncaragh asserted in the Planning Application to be the groundwater flow direction from the Site southeast to discharge to the Dooradoyle River in excess of 500m from the Site.

Figure 1 - extract from Planning Application Site Location Map

Figure 2 - extract from Planning Application/WERATN [27] Surface Water Receptors Figure 2.2

Grounds on Which Relief is Sought - Brief Summary

9. While leave to seek judicial review was granted [28] on wider grounds, and it will be necessary in due course to further consider the pleadings, by the end of the trial it was apparent that ETI relied only on three grounds of attack on the Impugned Permission as follows:

1. That the Board failed to circulate the ETI submission to the Second Respondent (the “Council”).

2. That the drawings accompanying the Planning Application were not in accordance with Articles 297 and 298 PDR 2001 [29]. Essentially, it is alleged that drawings were divergent and irreconcilable in that the engineer’s drawings and accompanying reports and other engineer’s documents proposed a basement car park Finished Floor Level (“FFL”) of 11 metres above Ordnance Datum (“11m OD”) whereas the equivalent figure in the architect’s drawings was 10 metres above Ordnance Datum (“10m OD”). So, the architect showed the basement car park FFL a metre lower than did the engineer. The fact of the discrepancy is now admitted by all - but its legal significance is disputed.

3. That the AA done by the Board was invalidated [30] by gaps and lacunae, in that it failed to consider, adequately or at all, the alleged risk to the SAC posed by cement leaching from concrete to be poured in the construction works being carried from the Site by groundwater flow. In essence, two failures are asserted:

o Failure to identify and consider the risk of cement entering the groundwater;

§ It is agreed that the Board did not identify and consider that risk but the question remains whether this absence represents a lacuna in the AA.

o Failure to adequately identify hydrogeological pathways via which leached cement might travel from the Site to the SAC.

4. An allegation that the Board failed to comply with EIA screening requirements was not pursued - not because ETI considered it unviable but because ETI took the helpfully pragmatic view that if it failed on the AA point it would fail also on the EIA point [31].

Procedural History of the Judicial Review Proceedings [32]

5. Leave to seek judicial review was granted by order made on 18 October 2021. The Statement of Grounds inter alia sought to have quashed the Council’s decision to approve the statutory report [33] of its Chief Executive to the Board dated 24 June 2021 in relation to the Planning Application (the “Chief Executive’s Report”). On 18 October 2021, and on ETI’s application, the claims for relief against the Council and the State were adjourned generally such that neither was served with the proceedings or required to file opposition papers. They have since played no part in the proceedings.

6. The Chief Executive’s Report concluded that the proposed development was consistent with the applicable Development Plan and in accordance with the proper planning and sustainable development of the area. It is not entirely clear to me that there was such a decision and it may be that the proper relief, were any appropriate, would have been to simply quash the report itself [34]. But nothing turns on that, at least for now, as the case against the Council stands adjourned [35]. However, the Council’s involvement in the process is important to Ground 1 as to the allegation of failure to circulate the ETI Submission to the Council.

7. At a Directions hearing on 4th April 2022 these proceedings, as against the Board only, were listed for hearing from 28th June 2022 and trial before me proceeded accordingly. At that Directions hearing, ETI raised no issue as to its case against the Council. On that occasion also, ETI was given liberty to issue a motion to cross-examine the Notice Party's deponents - such motion to be returnable for mention on 9th May 2022. ETI did not avail of that liberty - instead it filed the third affidavit of Michelle Hayes, sworn 29th April 2022.

2016 Act - Introductory Note

8. In very general terms, the purpose of the 2016 Act, as it relates to SHDs, can be described as a temporary [36] response to what has become generally known as the national “housing crisis” - a chronic deficiency in the national supply of housing. It applies to applications for planning permission for certain large residential developments - deemed SHDs by the 2016 Act - and the Proposed Development comes within the definition of an SHD [37]. The method of the Act is to expedite the SHD planning process by exceptionally providing that the planning application be made directly to the Board - as opposed to the normal process of application to the local planning authority with recourse to the Board only on appeal. This purpose is achieved in part also by a formal pre-application consultation process between the developer and the Board - such that the developer is expected to produce an “oven ready” development proposal in its planning application. This likely explains the omission of the “further information” process which adds to the duration of non-SHD planning applications. Importantly and doubtless as, unusually, the application is made directly to the Board, the 2016 Act requires the relevant planning authority to consider the planning application and submissions thereon and its Chief Executive to report to the Board on such consideration. Again in the cause of expedition, the SHD process is also characterised by strict deadlines applicable to the various steps in the process.

AA - the Basic Rule

9. While I will address the law later in this judgment, it is useful to recall, in reading what follows, the basic rule of AA as identified in the seminal Waddenzee [38] case:

“The competent national authorities, taking account of the appropriate assessment of the implications of [the project] for the site concerned in the light of the site's conservation objectives, are to authorise such an activity only if they have made certain that it will not adversely affect the integrity of that site. That is the case where no reasonable scientific doubt remains as to the absence of such effects.”

As AG Kokott says in Lies Craeynest [39], this standard has the same effect as a presumption that projects adversely affect European Sites and so, in principle, should not therefore be implemented. That presumption can be refuted only by removing all reasonable scientific doubt.

While that presumption applies in the AA process before the Board, as will be seen, the position is more complex once the Board has made its decision and if the matter comes to judicial review.

Karstic and Fractured Limestone - a note [40]

10. Below the Site is a limestone aquifer [41]. The papers disclose dispute whether the limestone is karstic or is better described as fractured. Limestone is fractured by earth movement. Limestone is karstic where water erosion of pre-existing fractures has produced a network of enlarged channels. All agree this limestone is either one or the other - perhaps both. It is not clear to me that anything turns on this distinction for present purposes. Whether fractured or karstic or both, at least a possible effect is to direct groundwater flow in greater or lesser degree other than down the general gradient of the land and/or hydraulic gradient [42] of the water table in the area.

URS Closure Report 2013

11. In September 2013, URS Ireland Ltd (“URS”) prepared an expert “closure” report on the petrol station to Esso [43] (“the URS Report”) to provide a single point of reference for the investigation and validation work done to make the petrol station site suitable for future commercial use. It is in substance a collection or summary of 15 earlier reports [44] dated between 2005 and 2012. It records, inter alia:

· URS investigation, sampling and assessment of, and repeated reporting on, the Site since 2005, including as to risks to groundwater - which work is summarised.

· Decommissioning included site remediation, by reference to pollutant risk, supervised by URS. In the decommissioning 4 Tanks were removed - leaving in situ 4 Tanks which had been installed in 1959.

· A finding of no significant risk to “controlled waters” [45].

· That excavation works for redevelopment are likely to encounter visually impacted and odorous soils and shallow groundwater.

· That, assuming a redeveloped site sealed by structural slabs, managed landscape and the like, contaminants are not a significant risk to commercial users.

· That the site is free of contaminants to the extent and degree necessary for commercial development.

12. However, the URS Report is, at least to the layperson, confusing as to groundwater flow direction. It says the site slopes “southwest along the general gradient of the surrounding land” [46]. In contrast, and as recorded above, the Groundwater Management Plan [47] in the Planning Application says that the Site generally falls to the south-east in accordance with the gradient of the local area, and Dr Drew [48] appears to agree. Disagreement on such a basic matter seems surprising. The URS Report states variously that inferred groundwater flow direction is “to the west [49] and southwest” [50] “towards the south” [51] and “in the northern section of the site was towards the west”. [52] Figures 5 and 6 of the URS Report illustrate Conceptual Site Model sections on a north/northwest - south/southeast axis. But neither these figures nor the model they illustrate, nor the reason for the choice of axis, are referred to in the body of the URS Report [53]. The choice of axis appears to contrast with the Planning Application expectation of groundwater flow to the south-east [54].

13. The URS Report includes section drawings depicting sub-surface strata including made ground, till, weathered bedrock, limestone bedrock, groundwater level, and also depicting monitoring wells/boreholes, soil sampling trial pits and a “Non-Registered Groundwater Supply Well” over 250m southeast of the Site.

14. As Cloncaragh relies on it in the present process, I note that in the URS Report the conclusion of absence of significant risk to “controlled waters” is based on a “Controlled Waters Risk Assessment” by reference to “SSTLs” [55] - which I take to be related to hydrocarbons and other contaminants. Those SSTLs were calculated in contemplation of theoretical groundwater wells in shallow bedrock 100m from the site. [56] The URS Report lists an appendix: “Controlled Waters Risk Assessment”. But I have not seen it and it is not apparent that the Board saw it, as the URS Report is exhibited three times in these proceedings, including by the Board, and no copy includes the appendices. What I take to be a summary of the Controlled Waters Risk Assessment appears in the URS report [57]. It records that SSTLs were set as “protective of controlled waters” but is unspecific as to the applicable standards and purposes of protection or how, if at all, they related to the conservation objectives of the European sites [58]. It concludes that no significant risks to controlled waters receptors exist. The URS Report does not identify what is meant by, and no one in these proceedings deposed to what is meant by, “controlled waters” which, as far as I am aware, is not a term of art at Irish Law. I am aware that it is a term defined in UK water pollution law and includes groundwaters, inland freshwaters and coastal waters [59]. It seems reasonable to conclude that the Controlled Waters Risk Assessment in this case was done by reference to the standards of applicable UK law. While I readily infer its possible relevance to informing AA, I cannot infer that a Controlled Waters Risk Assessment is intended to, or does directly, address requirements of Habitats Law. Certainly, the URS Report does not in terms mention or address Habitats Law issues, much less consider risk to the specific conservation interests of the SAC. I am unaware if the URS Report was proffered in the refused 2019 SHD planning application [60] and it was, no doubt properly and fairly, not proffered in the subject Planning Application by way of argument that AA was unnecessary.

2019 Refusal

15. The Inspector’s report records that in 2019 a SHD planning application for 70 student apartments (326 bedspaces) and 30 build-to-rent apartments was refused (“the 2019 Refusal ” [61]) for one reason only, relating to AA - which had been “screened out” [62] by the planning applicant such that no NIS was before the Board. That reason is set out in full in the Inspector’s report in the present matter [63], as follows:

“The proposed development includes the excavation of c. 33,000m3 of soil/ subsoil and removal of fuel tanks and hazardous substances. The site is located on lands where the groundwater is extremely vulnerable (www.gsi.ie [64]) and it is located c. 1km from the edge of the River Shannon and River Fergus Estuaries SPA …. and the Lower River Shannon SAC ……

The submitted Screening for Appropriate Assessment has regard to the inclusion of mitigation measures to control silt/sedimentation and spillage of hazardous substances to prevent any likely significant impact on the groundwater pathways which provide a hydrological pathway for polluted water. Measures intended to avoid or prevent significant effects on a European site cannot be considered in screening for AA ……….. Having regard to the inadequacy of information provided in the Screening Report, the nature of the proposed development, the misapplication of mitigation measures and the absence of a Natura Impact Statement, the Board could not be satisfied that a full understanding and analysis of the hydrological connectivity between the site with [65] the … River Shannon and River Fergus Estuaries SPA … and the Lower River Shannon SAC … and the potential implications of the proposed development on the groundwater quality has not [66] been undertaken.

The Board therefore cannot be satisfied, beyond reasonable scientific doubt, that the proposed development, either individually or in combination with other plans and projects, would not adversely affect the integrity of River Shannon and River Fergus Estuaries SPA ……… and the Lower River Shannon SAC ……. in view of the site’s Conservation Objectives. The proposed development would therefore be contrary to the proper planning and sustainable development of the area.”

16. In addition, the AA section of the Inspector’s report in the present matter records points of note from the Inspector’s report which informed that earlier refusal, including:

· Bedrock near the surface of the Site and groundwater classified by GSI as highly vulnerable.

· History of hydrocarbon contamination.

· Proposed excavation and removal of c.33,000m3 of soil/subsoil and 4 fuel Tanks to accommodate basement parking

· Serious concerns as to the impact of such extraction on water quality, inter alia by transfer of hydrocarbons and hazardous substances through percolation of the Site.

· A direct link from the Site to the European Sites.

Accordingly, the absence of an NIS precluded permission.

17. The Water Environment Risk Assessment Technical Note (“WERATN”) submitted with the Planning Application records [67] further content of the 2019 Refusal as follows:

“The excavation of circa 33,000 m³ of soil/subsoil and removal of fuel tanks and hazardous substances on lands where the groundwater is extremely vulnerable, could result in a significant negative impact on the existing water quality of the [European Sites].”

“The proposed extraction of materials, in particular the fuel tanks have the potential to cause pollution via percolation and I have serious concerns relating to the impact on water quality, inter alia the transfer of hydrocarbons and hazardous substances through percolation of the site” [68]

Site Investigation Report - January 2020

18. A 2019 site investigation for Cloncaragh, by “IGSL” for Pierce McGann, Engineers, is described in a report dated January 2020 appended to the Civil Engineering Report of January 2021 submitted with the Planning Application. It is fair to regard it as supplemental to what was already known of the site from the URS report. IGSL drilled 8 boreholes, the records of which are provided, and describe the findings as to such as underground strata content, strength and groundwater levels. Samples were lab-tested for hydrocarbons - 3 exceeded the landfill waste acceptance criteria for inert material. Hydrocarbon odours were noted in several locations. Dr Drew, for ETI, is critical of this site investigation [69].

WERATN [70] - January 2021

19. The WERATN is overtly prepared by SLR. It was in fact prepared by a hydrogeologist - though that became apparent only in proceedings. In light of the 2019 Refusal, it was prepared “to address the risk to” European Sites and to “update” the URS Report to that end. It is not apparent why it is a “Technical Note” rather than a “Report” or what such a distinction might imply, if anything, as to the status of the document or its content - but no point was taken in that regard.

20. The WERATN cites [71] verbatim relevant content of the Inspector’s report and Board’s decision in the 2019 planning refusal (some of which is set out above) and states [72] that the WERATN was prepared “further to” the “considerations raised” by the Board in that decision to address the risk to the European Sites. It identifies those matters as “the potential risk to the [European Sites] from the excavation of soils, subsoils and fuel tanks at a location where the groundwater could be vulnerable.” [73] The inspector in the 2019 Refusal had noted [74] that the site was “c 1km from the edge” of the European Sites and considered that “there is a hydrological pathway between the site and these European Sites via the groundwater” and considered [75] also that there was “a direct source-pathway-receptor linkage from the site to the River Shannon and River Fergus”. For reasons not apparent, the WERATN does not recite a significant element of the 2019 Refusal - that permission was refused as:

“ … the Board could not be satisfied that a full understanding and analysis of the hydrological connectivity between the site with [76] the … [European Sites] … and the potential implications of the proposed development on the groundwater quality has not [77] been undertaken.”

But as that passage is recited in the present Inspector’s report, the Board’s awareness of it is clear.

21. The Conceptual Site Model used by the WERATN to analyse “the different Source - Pathway [78] - Receptor linkages” [79], and thereby risk [80], is said [81] to describe:

· “the potential sources of contamination at a site

· the migration pathways it may follow

· and the receptors it could impact upon.”

It is said [82] to focus on the site-specific potential contamination and potential pathways.

22. The identified [83] potential groundwater contamination sources are essentially soils contaminated by hydrocarbons/chemicals in the vicinity of the Tanks.

23. On foot of the 2019 site investigation, the WERATN infers [84] a steep water table gradient from borehole groundwater strikes noted at 1.3m bgl [85] on the northern boundary of the Site and at 5.1m bgl at the southern boundary - said to be consistent with the tabulated URS-reported groundwater levels [86]. Dr Drew thinks this unlikely.

24. The primary pathway identified [87] is the lateral flow [88] of that groundwater contamination from the Site through the weathered limestone aquifer. The WERATN identifies the Dooradoyle River as the [89] surface water receptor of groundwater flow as it is downgradient of the site. That river flows into the River Shannon. The WERATN states [90] that “Groundwater flow direction in the limestone bedrock and overlying limestone gravel is expected to follow the topography towards the south east as shown on Figure 2-1” [91] through the weathered limestone aquifer towards the Dooradoyle River at a point over 500m from the Site. [92] I understand this to mean that the groundwater flow will follow the inferred water table gradient in the same direction as the topography, southeast to the Dooradoyle River and thence via that river to the European Sites.

25. Though explicitly based on updating the URS report, the WERATN does not refer to or explain why the expected groundwater flow to the southeast, due to the steep hydrological gradient, differs from that expected by URS which inferred groundwater flow direction variously to the west, the southwest and the south but not to the southeast. [93]

26. It is said [94] that most groundwater flow is likely to take place in the top 30m approximately - in a weathered layer of a few metres (epikarst) and a connected fractured layer below it. Deeper groundwater flow occurs along fault zones and large fractures. The WERATN cites [95] the URS “Controlled Waters Risk Assessment” - which I have considered above.

27. Though not so entitled, what is clearly the conclusion of the WERATN is as follows [96]:

· The URS Controlled Water Risk Assessment shows that the groundwater results from the Site did not exceed SSTLs in the weathered bedrock strata 100m downgradient of the Site [97].

· These target levels will also be protective of the bedrock aquifer more than 500m downgradient of the site at the Dooradoyle River.

· Contaminant concentrations in the European Sites arising from the proposed development will be negligible due to:

o The removal during construction of the contamination source (Tanks, contaminated soil and groundwater).

o The Dooradoyle River is more than 500m downgradient of the Site in the direction of groundwater flow.

o It is assumed that the Dooradoyle River is in direct continuity with the weathered bedrock and that any potential contamination 500m downgradient of the site could reach the River.

o However, the ground conditions at the “GSI well” directly south of the Site and between it and the Dooradoyle River [98] indicate approximately 11m of overburden. The groundwater vulnerability classification also indicates more than 10m of moderately permeable subsoil. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that contamination from the Site has reached or will reach the Dooradoyle River via the bedrock aquifer.

· In the highly unlikely event that any contamination reaches the Dooradoyle River, an estimated dilution factor of over 1,000 would apply to any such contamination [99]. For the avoidance of doubt, and as there may have been some misunderstanding at trial, this dilution factor does not refer to dilution in the groundwater between the Site and the Dooradoyle River. It refers to dilution at entry of the groundwater plume into the River.

· A further dilution factor of over 2,900,000 would apply along the 2.3km stretch of River to the nearest European Site. [100]

· This clearly demonstrates that the risk of contamination from the Site affecting the European Sites is negligible.

· These conclusions are consistent with the conclusions of the URS Closure Report (2013): “that currently no significant risks to controlled water receptors exist”.

28. Of the foregoing analysis I observe that:

· While it is correct to identify that removal of contaminants will decrease risk once the excavation is complete, it is their removal during excavation works that is identified in the WERATN [101] and by the Inspector in the 2019 Refusal [102] as posing the risk to European Sites.

· The analysis is predicated on expected groundwater flow to the southeast. The inconsistency of this expectation with apparently contrary views in the URS Report is not interrogated - a point made repeatedly in the ETI Submission to the Board [103] as a “fatal” and “major omission”.

Groundwater Management Plan (Basement Construction Phase) - January 2020

(“Groundwater Management Plan”)

29. This was prepared by SLR - specifically by its Director (Geotechnical Engineering) and Technical Director (Hydrogeology; Risk Assessment & Retail Petrol Station Remediation). Its stated purpose [104] is to plan, inter alia, measures to ensure that groundwater (including potentially contaminated groundwater in the vicinity of the 4 Tanks to be removed) is collected, treated as required, and disposed of in a manner that does not affect the integrity of the European Sites.

30. Though they cover much of the same ground, the Groundwater Management Plan and the WERATN do not refer to each other. But they are consistent with each other. Like the WERATN, the Groundwater Management Plan states [105] that the topography, locally and on Site, falls from the north west to the south east towards the Dooradoyle River - “Groundwater flow is expected to follow the topographic gradients, … underlying flow to the southeast”. Like the WERATN, it infers [106] a steep water table gradient from borehole groundwater strikes noted at 1.3m bgl on the northern boundary of the Site and at 5.1m bgl at the southern boundary. The Groundwater Management Plan records [107] the URS record of hydrocarbon contamination near the “historical underground storage tank farm”.

31. The Groundwater Management Plan states as to “Overall Approach to Groundwater Management - Basement Construction” [108] and “Groundwater Management Measures” [109], that

· It envisages a “.. basement … formation level of 11mOD” [110] - this is another way of referring to a Basement FFL of 11mOD [111]. From this the Groundwater Management Plan estimates basement excavation formation level at approximately 10mOD generally - in places lower to accommodate sewers and storm water attenuation tanks [112].

· “This indicates a likely positive groundwater head of up to +2m in the north-western corner of the site above the base of the excavation, with the majority of the basement excavation above the average groundwater level suggesting a dry excavation. The groundwater will increase further for the localised areas of the site where the deeper stormwater attenuation tank will be constructed. This indicates that groundwater control will be required in localised areas of the basement in order to maintain a dry excavation and enable basement and drainage construction”. So, “groundwater seepage will not be encountered across the majority of the excavation at elevations above 10mOD. However, groundwater seepages will be present in the north-western site. This coincides with the lowest 1m to 2m of the excavation in this area.”

· “The perimeter of the basement excavation will be constructed using an interlocking secant pile wall system, seated into the underlying weathered limestone bedrock at depths greater than 5m as illustrated in Drawing 18.104-10 in Appendix 01, to ensure excavation side wall stability". Secant reinforced concrete piles will be designed and constructed around the site perimeter to an average depth of 4 metres below bedrock level and more than 4 metres below groundwater level [113]. “The embedded secant pile wall will cut-off groundwater inflow from the Made Ground.” [114]

o I reject any complaint of inadequacy of these details - both as to substance and as not pleaded [115].

· Given the small area requiring groundwater control [116], the potential vertical head pressures, the calculated possible groundwater flow rates into that area and therefore required drawdown [117] and pumping rates, and the duration of the programme, manageable volumes of water are likely to be generated and groundwater control via traditional in-excavation sump pumping would be suitable. A groundwater control trench or sumps in the bedrock can be made if required.

· A delineation borehole investigation of the area containing the Tanks to be removed will identify the extent of the contaminated soil. That area will be isolated by a local sheet pile wall before removal of the Tanks and any contaminated soils and groundwater beneath in a reduced level excavation - which will be at groundwater level and require groundwater control to allow dry excavation.

· Groundwater control will be by a specialist contractor and a qualified Environmental Consultant will manage the contaminated soil excavation.

· Soil sampling and analysis will validate complete removal of contaminated soil.

· A mobile treatment plant will treat contaminated soil and groundwater. It will typically reduce dissolved hydrocarbon concentrations to below laboratory limits of detection.

32. I accept that §4.2 of the Groundwater Management Plan, part of which I have cited above, describes the mitigation intended to ensure that the groundwater below the site will not be contaminated. The adequacy of that information is a matter for the Board who are entitled to at least some curial deference on that issue (see Kemper [118]), and to the extent it is in controversy between experts, there was no cross-examination on the issue.

AA Screening Report & NIS - January 2021

33. The AA Screening Report and NIS are conveniently combined in one document. They were, as is required, prepared by experts - whose expertise is not impugned. They were informed, inter alia, by the WERATN, the Groundwater Management Plan and other documents, which describe mitigation measures [119].

AA Screening Report

34. The AA Screening Report considers the possibility of risk to the SAC and SPA by release of pollutants to groundwater from contaminated soils during excavation and construction. [120] It does so specifically on foot of the WERATN, the conclusion of which it cites in extenso - and it concludes that “while it is not considered likely to occur there is potential for contaminated groundwater to reach” the European Sites.

35. The AA Screening Report considers that:

· It is clear from the WERATN that any effect on the SPA due to release of pollutants via groundwater is not likely to be appreciable. Effects on the SPA are not likely to be significant based on the nature of the qualifying interests of the SPA and the sensitivity of these species and their supporting habitats to groundwater water pollution.

· While the WERATN considers the likelihood of contaminated groundwater reaching the SAC to be negligible, the significance of potential effects on the SAC is uncertain as some of the qualifying interests [121] may be affected indirectly through the potential for reduction in water quality.

· So AA is required, as to effects on the SAC, “to facilitate provision of mitigation measures on a precautionary basis.” (Mitigation cannot be considered in AA Screening [122]).

36. The WERATIN conclusions informed the AA Screening to the effect that:

· In the highly unlikely event that any contamination reaches the Dooradoyle River, it is estimated that a dilution factor of over 1,000 would apply to any such contamination.

· A further dilution factor of over 2,900,000 would apply along the 2.3km stretch of River to the nearest European Site.

Despite that information as to dilution factors, AA was deemed necessary:

· because the significance of potential effects on the SAC was considered uncertain as some of the qualifying interests may be affected indirectly through the potential for reduction in water quality

· “to facilitate provision of mitigation measures on a precautionary basis.”

So, the dilution factors by themselves did not enable screening out AA, and mitigation was necessary to the conclusion in AA set out in the NIS.

NIS

37. The NIS [123] provides supporting information to assist the Board determine in AA to whether the proposed development would adversely affect the integrity of the SAC. “The focus is on demonstrating, with supporting evidence, that there will be no adverse effects on the integrity of the SAC. Where this is not the case, adverse effects must be assumed.” I do not suggest that, had it been pleaded, a challenge on this account would have succeeded but, in passing, I respectfully observe that the “focus” of an NIS should not be on “demonstrating” that “there will be no adverse effects”. It should be on determining whether there will be adverse effects. The difference is of mindset in preparing a NIS.

38. It is recorded that the elements of the project likely to give rise to significant effects on the SAC are the excavation, removal and treatment of contaminated material from the Site, including the removal of the Tanks, and any potential migration of any groundwater pollution offsite to the SAC. The specific attributes and targets defining the conservation objectives for each qualifying interest of the SAC were reviewed and considered for the qualifying interest likely to be affected.

39. The WERATN is again described as finding that contaminant concentrations at the European Sites from the proposed development will be negligible based on an examination of the bedrock and groundwater vulnerability as well as the distance to the closest surface water receptor and estimation of the dilution factor of the watercourses. Therefore, it is said, the WERATN considers it highly unlikely that any contamination from the site will reach the closest surface water receptor via the groundwater. “While the Water Risk Assessment similarly considers the likelihood of contaminated groundwater reaching the Lower River Shannon SAC to be negligible; the significance of potential effects on the Lower River Shannon SAC is uncertain as some of the qualifying interests may be affected indirectly through the potential for reduction in water quality”. [124] The NIS next asserts that “The integrity of the … SAC is not considered likely to be affected as the WERATN …… considers that it is highly unlikely that any contamination from the site has reached, or will reach, surface water receptors via groundwater.” The NIS then moves [125] to Mitigation Measures which it describes primarily by citing the other documents [126] enclosed with the Planning Application. The NIS records [127] that “The mitigation measures to be implemented to avoid effects on ground and surface water are measures that are well established and proven to work. The measures proposed in this report and in greater detail in the documentation accompanying the planning application are used as standard in construction and operation of similar developments and their efficacy in protection of the receiving environment is proven and demonstrable.”

40. The NIS concludes [128] that there is certainty that will be no adverse effects on the integrity of the SAC and that the Board has sufficient information to allow it to so conclude.

ETI Submission - 3 June 2021 - Content

41. Substantively [129], the ETI Submission is a wide-ranging document - covering many topics and running to over 100 pages [130]. Of present interest is its assertion that the redevelopment of the Site, formerly a quarry, latterly a petrol station and sitting on an extremely vulnerable [131] karstic limestone aquifer which creates a direct hydrological link to the European Sites, creates a major risk of groundwater contamination and, in turn risk to the SAC. The contamination risk is allegedly posed by hydrocarbons and other leachates due to the petrol station and to the Tanks, likely corroded and leaking, to be removed. [132]

42. ETI asserts inadequacy of the Site investigation and of the AA as to the risk posed to groundwater by the contaminated Site. Inter alia, ETI asserts that Cloncaragh has not demonstrated, given that karstic features may redirect groundwater flow from general surface gradients, that the groundwater flow direction from the Site is to the southeast [133] to the Dooradoyle River [134]. Put simply, ETI asserts that Cloncaragh assumes a longer and more diluting flow to the European Sites than might be the case by reason of karstic features resulting in shorter/more direct routes to the European Sites. ETI notes that URS had inferred groundwater flow to the west and southwest - i.e. more directly towards the European Sites - which flow Cloncaragh ignores. This is alleged to be a “fatal” and “major omission” [135] - as is the alleged absence of a geological or hydrogeological report or groundwater report. The inadequacy of the Groundwater Management Plan is asserted. So, ETI asserts, Cloncaragh’s assumptions as to dilution of pollutants in the Dooradoyle River en route to the European Sites are unreliable having regard to the standard of proof beyond reasonable scientific doubt required in AA [136].

43. ETI asserts [137] a risk posed by intended piling - the gravamen of which seems to be a risk of providing a route for hydrocarbons and like toxins to reach groundwater. However, and notably, the ETI Submission does not identify a risk of cement leaching to groundwater.

44. The ETI Submission considers the URS Report, inter alia, as:

· Relating to the safety of the site for commercial, as opposed to residential, development.

· Recording variable groundwater levels to no discernible seasonal pattern.

· Recording hydrocarbons found and pollutant risks.

45. The ETI Submission critiques the WERATN and NIS in some detail, inter alia:

· That the WERATN was anonymously prepared and based on conjecture, assumptions and a lack of evidence.

· Asserting that the WERATN’s implication that the extreme vulnerability of the aquifer has been lessened by the backfilling of the quarry is unsubstantiated.

· Doubting the conclusions that:

o it is highly unlikely that contaminants from the site will reach the Dooradoyle river.

o the asserted fact that that the SAC is 2.3km further downgradient, in the Ballinacurra river, from the discharge of groundwater from the Site to the Dooradoyle River will result in further dilution.

· This, it is asserted [138], ignores:

o the direct hydrological link to the European Sites by groundwater. (In general terms, by this is meant a link directly to the European Sites to the west/southwest of the Site, not mediated by the Dooradoyle River).

o a stream on the Site previously seen by local residents and probably now underground.

o the complex effects of karst on groundwater directional flow.

o variable groundwater flow direction reported by URS.

o the URS inference of groundwater flow to the west.

o that the URS report suggests complex geomorphology requiring further analysis.

Circulation of ETI Submission to the Council & Report of the Chief Executive of the Council to the Board

46. In sequence, the next relevant events were the circulation of the ETI Submission to the Council and the Chief Executive’s Report. I will address these below when dealing with Ground 1.

AA - Inspector’s Report & Board’s Decision

47. The Inspector’s consideration of AA starts [139] with a recital of the reason for the 2019 refusal: essentially that the AA Screening Report and other information to hand had not enabled a full understanding and analysis of the hydrological connectivity between the Site and the European Sites, and the potential implications of the proposed development on groundwater quality. The inspector then recites certain content of the report of the Inspector which had informed that refusal, as follows [140]:

· The Site is on a highly vulnerable aquifer with bedrock near the surface.

· The history of hydrocarbon contamination of the Site.

· The proposal required removal of c.33,000m3 of soil/subsoil and 4 fuel tanks to accommodate basement parking. This prompted serious concerns at potential pollution via percolation of hydrocarbons and hazardous substances impacting water quality.

· The AA Screening Report stated that, assuming correct implementation of listed mitigation measures, impacts via the groundwater pathways are not likely to be significant.

· There is a direct link from the Site to the European Sites.

· The works, including excavation, removal of fuel storage tanks and the treatment of contaminated materials from the site, had not been fully detailed or assessed as to the potential impact on European Sites.

· Having regard to the scale of works and implications for groundwater quality a NIS was required.

48. The Inspector had, earlier in her report [141], recited observers’ concerns thematically [142] as including [143]:

· Removal of the hydrocarbon-contaminated tanks, soil and water and the possibility of other contaminants.

· Bedrock, aquifer, groundwater vulnerability and directional flow, contamination and environmental impacts, and absence of assessment of the impact of past quarrying thereon.

· The URS report contemplated commercial, not residential, use.

· The WERATN fails to consider the quarry, the direct hydrological link to the SAC, the URS report inference of groundwater flow to the west (towards the SAC) and southwest, and the complex effects of karst on groundwater directional flow.

· Risk to the integrity of European sites by contaminated groundwater via the direct hydrological link.

· That the current proposal fails to overcome the 2019 reason for refusal.

· Inadequacy of data provision.

The Inspector notes [144] that the Planning Authority raised no objections on these grounds [145].

49. The Inspector had also, in her general planning assessment, considered the subject of contaminated lands [146], including removal of the Tanks containing contaminated water and of contaminated soils - citing in this regard a “common thread” of observers’ concerns, including, by necessary implication, ETI’s concerns. The Inspector notes [147] historical hydrocarbon impact near the Tanks at the depth of the smear zone of the groundwater table and the underlying soils, indicating a probable contaminant source deriving from the base of the Tanks. She notes documents submitted [148] all of which she reads together [149].

50. She notes in particular the content and conclusion of the URS Report and the view expressed in the Construction and Demolition Waste and Management Plan that removal of fuel tanks and disposal of excavated materials to a licensed waste facility, necessary for the decontamination of the site, is not unusual for a city centre brownfield site. She notes that the Groundwater Management Plan includes measures to ensure that groundwater on the Site and any potential contaminated groundwater in the vicinity of the Tanks is collected, treated (where required) and disposed of/discharged in a manner that does not affect the integrity of the European Sites. She records that those mitigation measures include:

· Safety measures and contaminated water control measures relating to the removal of the Tanks and surrounding contaminated ground.

· A site-specific groundwater control management plan - to be agreed with the Council before works start.

· All groundwater generated from the activities on site is to be filtered and processed before discharge to sewers.

· Measures to ensure that groundwater is not polluted by excavation and/or construction works - in particular, management and control of groundwater will be such as to prevent any pollution downstream of the Site.

· Excavation and construction will accord with various listed documents [150].

The inspector considers [151] that “Mitigation measures are set out in detail in the relevant reports which I consider reasonable and enforceable”.

51. Notably, the inspector next devotes particular attention to the subject of “Excavations & Construction/Demolition Waste Management” [152], inter alia by reference to the Construction Management Plan. She notes that extensive excavation of the basement car park is intended and that “details are set out” [153] of the manner in which contaminated ground is to be excavated and disposed of. She notes that a secant pile wall will prevent groundwater ingress from surrounding roads before Tank removal starts. (The Inspector does not display any lack of understanding of what secant piles are). A specialist contractor will remove traces of contaminated material from the Site. More generally, all excavation on Site will be in accordance with the various SLR Reports. The inspector goes on to describe the procedure to remove the Tanks, once the secant piles are in place and before the bulk excavation starts, as including isolating the area around the Tanks with steel sheet piles to a depth of 10mOD to allow safe extraction of the Tanks and potentially contaminated ground material surrounding them. The sequencing and phasing of these works are described in the SLR reports.

52. Also notably, the inspector devotes particular attention to the Groundwater Management Plan [154] submitted in response to the previous reason for refusal - as is the NIS. She recites the basis of SLR’s inference of groundwater levels at 9.4mOD to 10mOD across most of the Site, corresponding to regolith depth across much of the site. It appears to be recharged from underlying limestone bedrock. There next follows [155] the inspector’s account of the basement formation and other levels. Notably, for present purposes and at the expense of repetition, it records:

“…….. a likely positive groundwater head of up to +2m in the north-western corner of the site above the base of the excavation with the majority of the basement exaction above the average groundwater level suggesting a dry excavation. Groundwater control will be required in localised areas of the site where the deeper stormwater attenuation tank will be constructed in order to maintain a dry excavation and enable basement and drainage construction. The stormwater attenuation tank will be below rest groundwater level and therefore an appropriate waterproofing design will be required to ensure no ground water ingress into the attenuation tank or drainage infrastructure on completion.”

53. There follows [156] the inspector’s description of excavation phasing and groundwater management measures. It is too lengthy to set out here in full but it includes:

· A specialist groundwater control contactor to provide detail design and to implement the groundwater control scheme - including its day-to-day management.

· A suitably qualified Environmental Consultant to manage the contaminated soil excavation around the Tanks.

· Identification by delineation borehole investigation of the contaminated zone, followed by its isolation from the rest of the excavation and dewatering works by a sheet pile wall.

· Use of an oil/water separator plant for groundwater abstracted in the contaminated zone. The plant proposed, of a type used in redevelopment of petrol station sites where tanks are removed, typically reduces dissolved hydrocarbon concentrations to below laboratory limits of detection.

· In some detail, a description of the removal procedure as to the Tanks and contaminated soil and dewatering of the area isolated by sheet piles for that purpose. [157]

· Ongoing soil sampling and analysis to validate the extent and completion of contaminated soil excavation.

· Groundwater abstraction from the excavation generally.

· Reference to SLR’s involvement in and knowledge of other similar remediation projects.

54. The inspector concludes [158] as to contaminated soil and groundwater risk that the measures proposed are robust and sufficient and address concerns raised by third parties.

55. I observe that the Inspector’s recital of the 2019 refusal, of the Inspector’s report in that refusal, of the observers’ submissions and of the AA Screening Report and NIS in the present application, and her treatment of the issue of contaminated lands and groundwater risk demonstrate that she was, in reporting to the Board on AA issues, fully conscious of the asserted risk posed by contamination of groundwater to European Sites and of the issues in that regard recited by her. I observe also that she had concluded that the measures proposed in those regards were robust, sufficient, and address the concerns raised by third parties.

56. Of the foregoing elements of the Inspector’s Report, ETI says that she “simply summarises what has been said by the developer before saying that it's satisfied that it's robust, but without providing any analysis”. [159] I respectfully reject that criticism. Given the technical nature of the task and works described, the fact that the proposed works under consideration were those proposed by Cloncaragh, that description of those works was to be found only in Cloncaragh’s expert reports and that no contrary technical appraisal had been submitted [160] it is entirely unsurprising that the Inspector’s report should have been largely informed by Cloncaragh’s expert reports. The Inspector’s report records a lengthy and detailed appreciation of what Cloncaragh proposed by way of those expert reports. I see no deficiency in the Inspector’s report in that regard. Indeed, it seems reasonable to infer that ETI’s pivot of their complaints to an issue of cement leaching rather than hydrocarbon contamination likely reflects its own view to similar effect.

57. Returning to the AA Section of her report [161], I note that the Inspector considered the content of the combined AA Screening Report/NIS as “reasonable and robust” and that “the submitted information allows for a complete examination and identification of all the aspects of the project that could have an effect, alone, or in combination with other plans and projects on European sites”. [162]

58. Essentially for the reasons set out in the AA Screening Report, she concludes that significant effects on the SAC could not be excluded. She notes specifically that the AA Screening Report identified potential pollution during the excavation, removal and treatment of the Tanks and contaminated material during construction and potential migration of contaminated groundwater to the SAC which could potentially cause adverse effects on the qualifying interests of the SAC. So her screening determination was that AA was required as to the possibility of adverse effects on the qualifying interests of the SAC.

59. The Inspector then moved to AA [163]. She observed that while the NIS itself was light on information, she identified the various site-specific documents [164] as to mitigation, cited in the NIS, as critical to her AA. The main area of concern was potential pollution during the excavation, removal and treatment of the Tanks and contaminated material and potential migration of contaminated groundwater to the SAC. She recites her detailed assessment of the methodology for the removal of Tanks, excavation, removal of contaminated soil and the groundwater protection plan and mitigation measures already set out [165] and again describes them as “robust and satisfactory” [166], and as “clearly described, reasonable, practical and enforceable” [167] to avoid or minimise the risk of impacts on the SAC.

60. Accordingly the Inspector considers it reasonable to conclude [168],

o on the basis of objective scientific information on the file, which she considered adequate to perform AA,

o and of complete assessment of all aspects of the proposed project,

o having regard to the works proposed during construction,

o and subject to the implementation of best practice construction methodologies and the proposed mitigation measures,

· that the proposed development would not adversely affect the integrity of the SAC or any other European site in view of their Conservation Objectives,

· and that there is no reasonable scientific doubt as to the absence of adverse effects.

These are the formal conclusions required in AA if planning permission is to be capable of being granted.

61. The Impugned Board Order records that it had performed AA Screening and AA. It explicitly adopts the Inspector’s report in both regards and echoes her conclusions.

Evidence

62. No fewer than 14 affidavits were sworn. While desirable in any event, it is necessary to set out an account of the affidavits given a dispute, in the context of Ground 3 as to AA, as to the status of some evidence and the significance of the fact that no deponents were cross-examined.

Affidavit of Michelle Hayes - sworn 11 October 2021 - filed by ETI

63. The judicial review application is grounded on the first Affidavit of Michelle Hayes. She is a practising solicitor and president of ETI. She authored the ETI Submission. She verifies the grounds, exhibits relevant documents, generally canvasses the themes of the ETI Submission. Inter alia, says that:

· The architectural and engineering drawings submitted with the Planning Application differ as to basement floor level: the former saying 10mOD; the latter saying 11mOD. It is unclear which is correct. So, the building will either be 1m higher than proposed [169], or 1m deeper than the environmental and engineering calculations assume [170]. This discrepancy was not identified in the application process.

· Generally, at the northern end of the Site, bedrock is within 3m of the surface, the centre of the site has been excavated and filled in in the past [171] and the southern end of the site falls away. [172] Groundwater levels are cited - higher at the northern end of the Site at 10.65mOD to 12.56mOD.

· The construction of the basement car park will involve:

o excavation into bedrock at the northern end of the Site;

o the laying of a concrete floor onto bedrock at the northern end of the Site and close to bedrock at the southern end.

· The Site will be part-surrounded and/or the Proposed Development part-supported by permanent secant piling [173]. This involves drilling interlocking bores into bedrock to a depth of 4m or more below the 9.5mOD estimated groundwater level and filling the bores with concrete. The Planning Application does not adequately explain that process.

· Pollution risk to groundwater posed by “cement, oil and chemicals” was inadequately addressed in the Planning Application. Cement is highly alkaline [174] and the risk of its discharge to groundwater in the piling process and by pouring of concrete on or close to bedrock - for example as floors - is not addressed in the planning application and represents a serious lacuna in the AA.

64. The affidavit also deposes to the events involved in the making of the ETI Submission to the Board. I address these further below.

Affidavit of Pierce Dillon - sworn 20 January 2022 - filed by the Board

65. This is essentially a formal affidavit exhibiting relevant documents and objecting to the ETI raising issues in this judicial review not raised by it in the planning process before the Board.

Affidavit of Tim Paul - sworn 28 January 2022 - filed by Cloncaragh

66. Mr Paul is an engineer of SLR, authors of many of the reports submitted with the Planning Application. He, inter alia:

· Asserts the adequacy of the various reports as to assessment of risk - including risk of hydrocarbon contamination.

· Identifies the author of the WERATN as a named hydrogeologist on SLR’s staff.

· Asserts that questions of hydrogeological connection to the European Sites were fully addressed in the WERATN and NIS which concluded that contamination of the European Sites would be highly unlikely and, if it occurred, negligible, citing very high dilution factors en route.

· Asserts that the Proposed Development will have an important benefit in resolving a known source of contamination by removing the remaining Tanks.

· Asserts that Ms Hayes’ concern as to cement is misplaced as:

o Groundwater control measures outlined in the Ground Water Management Plan will maintain a dry basement excavation for the basement construction save for a small controllable area in the northwest of the Site.

o Secant piling is formed of poured concrete, not cement, in a controlled construction technique and does not result in the discharge of cement to groundwater.

o On placement, concrete cures and hardens to form solid concrete elements.

· Asserts that

o the “key point” is that the GSI [175] does not classify the limestone bedrock aquifer as karstic.

o the bedrock is fractured limestone with fractures approximately 0.2cm apart [176].

o the correct bedrock and groundwater levels have been identified.

· Asserts that the Groundwater Management Plan sets out in considerable detail the more- than-feasible groundwater management and control measures for the basement construction using proven measures and technologies.

Affidavit of Pierce McGann - sworn 28 January 2022 - filed by Cloncaragh

67. Mr McGann is an engineer of Pierce McGann & Company, civil and structural engineers to Cloncaragh.

68. Mr McGann describes secant piling as providing permanent retaining walls around the site, including for the basement, and fulfilling other structural needs. The piles will be seated into the underlying weathered limestone at depths greater than 5m. He illustrates this by a Construction Management Plan Secant Piling Section detail drawing [177] which shows:

· the basement level at 11mOD and basement formation level at 10.5mOD.

· a variable groundwater level at average 10mOD falling across the site.

· a variable rock level at average 9.5mOD.

· secant piles extending to an average of 4m below rock level.

69. Mr McGann says secant piling “guarantees that groundwater is prevented from flowing into the basement excavation” and “eliminate[s] issues of groundwater ingress into the site”.

70. Mr McGann:

· asserts generally that the Construction Management Plan and Groundwater Management Plan set out detail of the secant piling and of the interplay of construction detail and groundwater management.

· denies that the secant piling process involves pouring cement into holes drilled in bedrock - the gravamen of which observation appears to be that what is poured is concrete not cement.

· asserts that secant piling is suited to use in limestone.

· is clear that concrete will not discharge to groundwater.

· asserts that the secant piling is drilled, not excavated, “as wrongly believed by Ms Hayes”. (If I correctly understand secant piling as excavation by drilling of vertical holes into which concrete is then poured, I do not understand this distinction made by Mr McGann as it seems to me that drilling is a particular form of excavation. This was my reaction to Mr McGann’s Affidavit before I had read the affidavit of Michael Duffy [178] so it is not a question of my now preferring the latter to the former on this issue.)

71. Mr McGann says Ms Hayes is wrong in believing that the buildings will be supported on piles - pad foundations will be used and can be laid so as to ensure that freshly poured concrete will not contaminate groundwater. The foundations will not contaminate groundwater.

However, Mr McGann also says that the piles will fulfil structural needs. So I am unclear of the position in this regard. They will obviously be retaining walls, and their location directly under the outer walls of the building may be significant. That said, it is not apparent that anything turns on this for present purposes and pad foundations are clearly intended [179].

72. Mr McGann addresses the assertion of discrepancy between the architectural and engineering drawings as to basement floor levels. He does so essentially by explaining and asserting the correctness and coherence of the engineering drawings and other documents reflecting a basement floor level of 11mOD. He says that detail of construction works, measurements and depths are not usual on architectural drawings and says he is “at a loss to understand … how Ms Hayes could be unclear on these details”. He embarks on a technical explanation at some length.

I confess that on first reading this Affidavit as to that allegation of discrepancy, I was left confused - especially as to the answer to the simple and basic question whether there was in fact a discrepancy between the architectural and engineering drawings as to basement floor levels. So I initially thought Mr McGann’s criticism of Ms Hayes harsh. As will be seen, in a later affidavit Mr McGann accepted that indeed there was, as between the architectural and engineering drawings, the very discrepancy Ms Hayes asserts as to basement floor levels. On rereading Mr McGann’s affidavits, I am confirmed in my view that it is regrettable that, before embarking on a complex explanation and justification of the engineering drawings and criticising Ms Hayes, Mr McGann didn’t, as a matter of the assistance the court expects from expert witnesses, simply and clearly accept and identify the existence of the discrepancy.

73. Mr McGann points out that the 11mOD basement floor level implies, in ease of risk to groundwater, a shallower excavation than a 10mOD basement floor level and says that, for excavation to 10mOD (to allow a 11mOD basement floor level), groundwater inflows are not expected and so groundwater controls will not be required for the majority of excavation works. He disputes any effect of the 11mOD basement level on building height.

74. Mr McGann echoes Mr Paul as to groundwater-borne risk to the European Sites.

Affidavit of David Drew - sworn 15 February 2022 & Exhibited Drew Report - filed by ETI

75. Dr Drew is clearly a hydrogeologist of considerable eminence, not least as to Irish limestone hydrogeology and karstic hydrogeology. Inter alia, he is the co-author of a GSI publication on the Karst of Ireland for the general reader and the sole author of what is clearly an important text on Irish karstic hydrogeology addressing, inter alia, investigative methods [180], and published by GSI [181] and written for an expert and technical readership. He did not contribute in the SHD planning process.

76. As relates to AA, Dr Drew considers that further hydrological investigation should be done. He cannot accept the conclusions of Mr Paul and Mr McGann as to hydrogeology. He disputes, to paraphrase him, that absence of evidence of karstic limestone is evidence of its absence. In limestone in a wet climate, karstification is assumed - only its type is unknown. He considers that the Applicants have assumed and surmised, rather than demonstrated, the hydrological connectivity between the Site and the European sites. In this he is referring to the precise directional route, as opposed to the more general issue of the existence of an hydrological connection, which is common case.

77. His exhibited report cites his consideration of the URS Report, the SLR Groundwater Management Plan, and the WERATN. He expressly, and properly, confines himself to hydrogeological issues - he explicitly disavows consideration of contamination and development issues. Indeed, he does not mention AA or relate his analysis to the requirements of AA or to the standards of proof and certainty applicable in AA. He says nothing on the question of doubt as to adverse effect on the European Sites.

78. Inter alia, Dr Drew:

· Asserts that a secure understanding of existing groundwater conditions is essential to a robust groundwater management plan which will prevent contamination of surface water bodies.

· Asserts that the URS and SLR Reports differ significantly in interpreting some aspects of geology and hydrogeology beneath the site and in the surrounding area. Neither investigates groundwater conditions to the point of provision of definitive answers.

· Makes detailed criticisms of the site investigation and the conclusions SLR draw from it [182] - in particular uncertainty as to the composition of the regolith [183], the absence of information as to groundwater in the bedrock for want of boreholes penetrating it, the possibility of perched groundwater, and the improbability of the steep water table gradient inferred by SLR from what he considers the anomalously high water level results of a single borehole at the northern end of the site - from which gradient SLR inferred generally southerly groundwater flow.

· Observes that objectors note an on-site water supply borehole which may penetrate into the limestone and could yield important water level data but is not referred to in the Reports.

o Mr Paul denies the existence of such a well on-Site. At trial it became apparent to my satisfaction that Dr. Drew’s observation likely derived from ETI’s misinterpretation of a URS drawing [184] which in fact shows a well over 250m southeast of the Site [185].

· Observes that SLR suggest possible upwards groundwater flow from bedrock at the northern part of the site. If true, this would be highly significant but it does not seem to have been investigated further.

o I observe that Dr Drew does not elaborate on why this is significant or with what possible or actual practical consequence, and the Planning Application documents explicitly envisages wet excavation in this area as requiring groundwater control measures.

· Observes that all limestone aquifers such as this will be karstified to some degree and so develop preferential flow paths, making flowpaths and discharge points difficult to predict without appropriate hydrogeological investigation. The SLR reports scarcely mention such conditions and instead seem to assume conventional, predictable, uniform down-hydraulic gradient flows (i.e. to the south east [186]). URS thought groundwater flows were to the south in August 2011 and to the west in October 2011/February 2012. SLR thought they were to the southeast/south - in each case determined by “groundwater” [187] gradients based on borehole water levels and assuming flow along the steepest gradients.

· observes that the SLR Report initially presumes a direct hydraulic link between the site and the Shannon and later definitely asserts it to be a link to the Dooradoyle river, a tributary to the Shannon.

o I comment that:

§ This appears to be a reference to the WERATN. As I read it, the WERATN initially records [188] the inspector in the earlier planning application as having assumed a direct source-pathway-receptor linkage to the Shannon/Fergus. It does not record the SLR authors as expressing that opinion.

§ SLR’s opinion [189] is that “Groundwater flow direction in the limestone bedrock and overlying limestone gravel is expected to follow the topography towards the south east”, “towards the Dooradoyle River” and “over 500m from the site” to a point about 2.3km upstream of the European sites.

§ This resulted in a conceptual model in which the assumed pathway was “Lateral migration through fractured bedrock aquifer to Dooradoyle River >500m downgradient of site [190], followed by migration in Dooradoyle River to Lower River Shannon SAC”.

§ Crudely, that assumes a 2.8km and much more diluting route than a more direct route via groundwater flow to the European Sites [191] - the nearest points of which are 1km southwest of the Site as the crow flies [192].

79. Dr Drew states that his reasons query the validity of the conclusions as to groundwater flow and as to hydrogeology more generally. Notably, he considers it “probable that the presumed groundwater levels relate to the regolith and that there is a regional water table in the bedrock unrelated to the superficial water system in the overburden. The latter may simply represent radial drainage of regolith water off the bedrock knoll on which the site is located.” Or the data “may well” represent “a perched groundwater body unrelated to the true groundwater in the bedrock”. And, especially “if the aquifer is karstic, with preferential flow paths and a weak relationship between flow directions and hydraulic gradients”, “Even if data for the bedrock aquifer were available it would not be possible to estimate groundwater flow directions by extrapolating from water level data for the boreholes clustered into such a small area (0.77ha). Data from a much wider area would be needed.”

80. Dr Drew considered further investigations desirable, including:

· Drill borehole into limestone to 30-40m below ground and record water data.

· Take on board the probable karstic nature of the aquifer.

· Verify the true groundwater flow direction to identify the likely receptor of any contaminated water.

81. While it was not his only point, it does seem fair to say that the primary thrust of Dr Drew’s report was that the Planning Application assumed, but failed to demonstrate, groundwater flow direction from the Site to the southeast and so erroneously ignored other possible, shorter, directional routes to the European Sites.

Affidavit of Michael Duffy - sworn 17 February 2022 - filed by ETI

82. Mr Duffy is an engineer. He comments on the McGann and Paul Affidavits, inter alia, as follows:

· He suggests the McGann affidavit is confusing on the basement floor level issue. (I have addressed this issue above.)

· The issue is not groundwater ingress but the potential for groundwater contamination during construction, including of the secant piles.

· A secant pile site wall will have no impact on groundwater rising through the bottom of the site or on material being discharged down through it.