Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> South Tees Development Corporation & Anor v PD Teesport Ltd (Rev1) [2024] EWHC 214 (Ch) (05 February 2024)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2024/214.html

Cite as: [2024] EWHC 214 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

BUSINESS & PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND & WALES

CHANCERY DIVISION (ChD)

Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| (1) South Tees Development Corporation (2) South Tees Developments Limited |

Claimants |

|

| - and - |

||

| PD Teesport Limited | Defendant |

|

| -and- |

||

| Teesworks Limited |

Third Party |

____________________

Andrew Walker KC and James Mitchell instructed by DWF Law for the Defendants

Katharine Holland KC and Admas Habteslasie instructed by Taylor Wessing LLP for the Third Party

Hearing dates: 3-6, 9-13, 16-20, 23-27, 30 October, 7, 9, 10 November 2023

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- This is a trial to determine the existence and extent of several rights of way that the Defendant ("D") claims to enjoy over the site of the former British Steel steelworks at Teesside, near Middlesbrough.

- The steel works were permanently closed in October 2015. The site now forms part of 4500 acres, which has been designated by central government as part of the UK's largest freeport. The area is said to be the largest brownfield development in Europe, and the development is expected to create up to 20,000 jobs for the local area.

- The first Claimant ("STDC") is a mayoral development corporation which was incorporated in August 2017, by statutory instrument to promote the regeneration of the area. The second Claimant ("C2"), is a wholly owned subsidiary of STDC which was incorporated in January 2019. I refer to the two Claimants together as "Cs". The third party ("Teesworks") is a private company which is a joint venture vehicle. C's have a shareholding in Teesworks. JC Musgrave Capital Limited, Northern Land Management Limited and DCS Industrial Limited are the other shareholders in Teesworks. Teesworks has the benefit of options over land owned by Cs. Although separately represented, the interests of Cs and Teesworks in this litigation are entirely aligned. I shall refer to them together as "the STDC parties". The STDC parties are the freehold owners of the land over which D asserts rights of way.

- D is the statutory harbour authority for the River Tees, and owner and operator of the port of Teesport, one of the UK's major ports. D owns the land where the port is situated. D also owns Redcar Quay and it owns land, including the breakwater and lighthouse, at South Gare. It also owns a strip of land bordering the Smith's Dock Road ("the Smith's Dock Road Parcel").

- D's land, and that of the STDC parties, forms part of the wider Teesside site ("the Site") which is located on the southern bank of the River Tees in the Borough of Redcar and Cleveland, approximately 3 miles from Middlesbrough and close to the towns of South Bank, Grangetown and Redcar. It broadly comprises of four areas known as South Bank, Redcar, Lackenby and South Gare, and abuts land owned by third parties (most notably Redcar Bulk Terminal Ltd ("RBT"). Fig 1 indicates the different areas' names within the Site and the public transport connections:

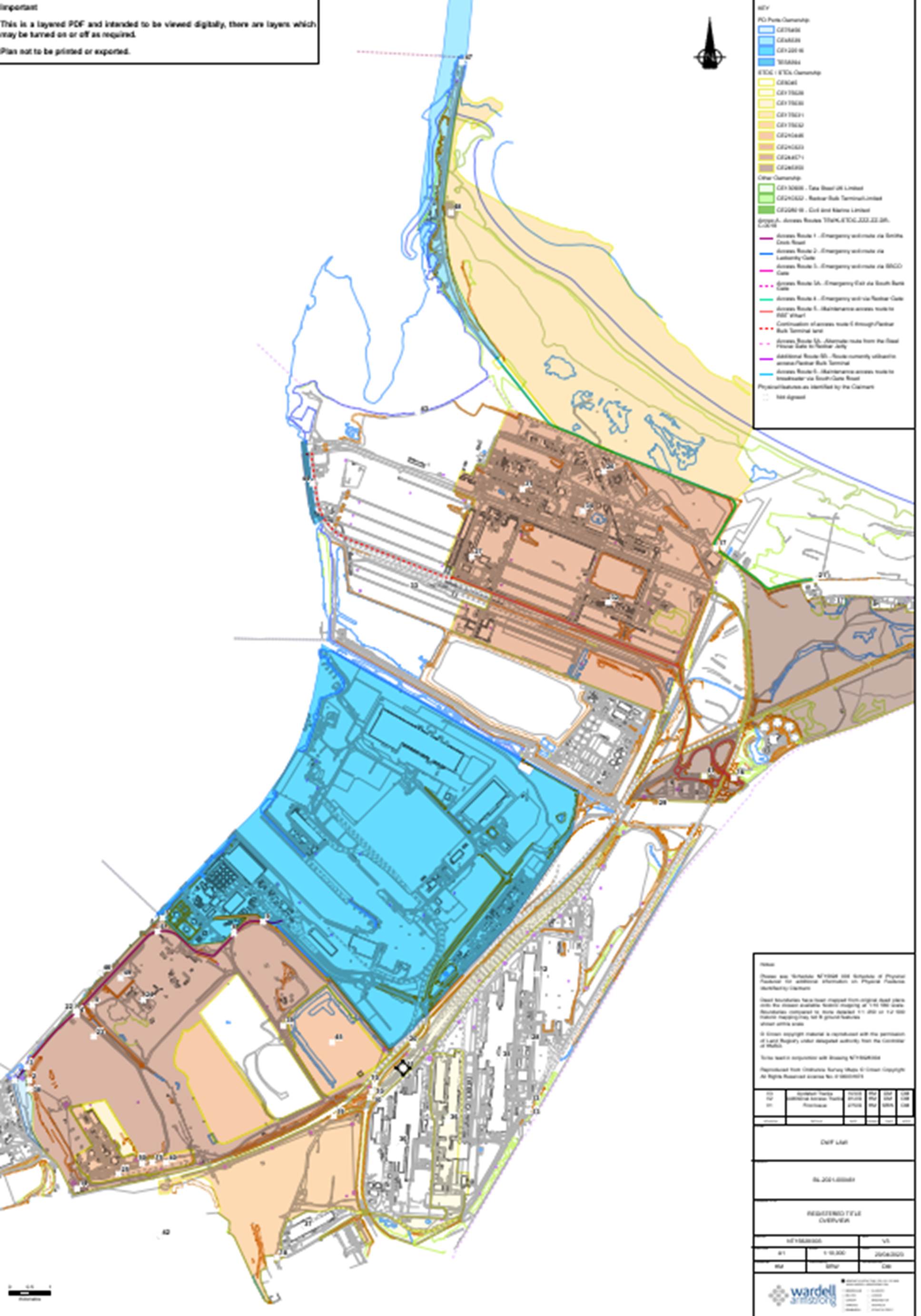

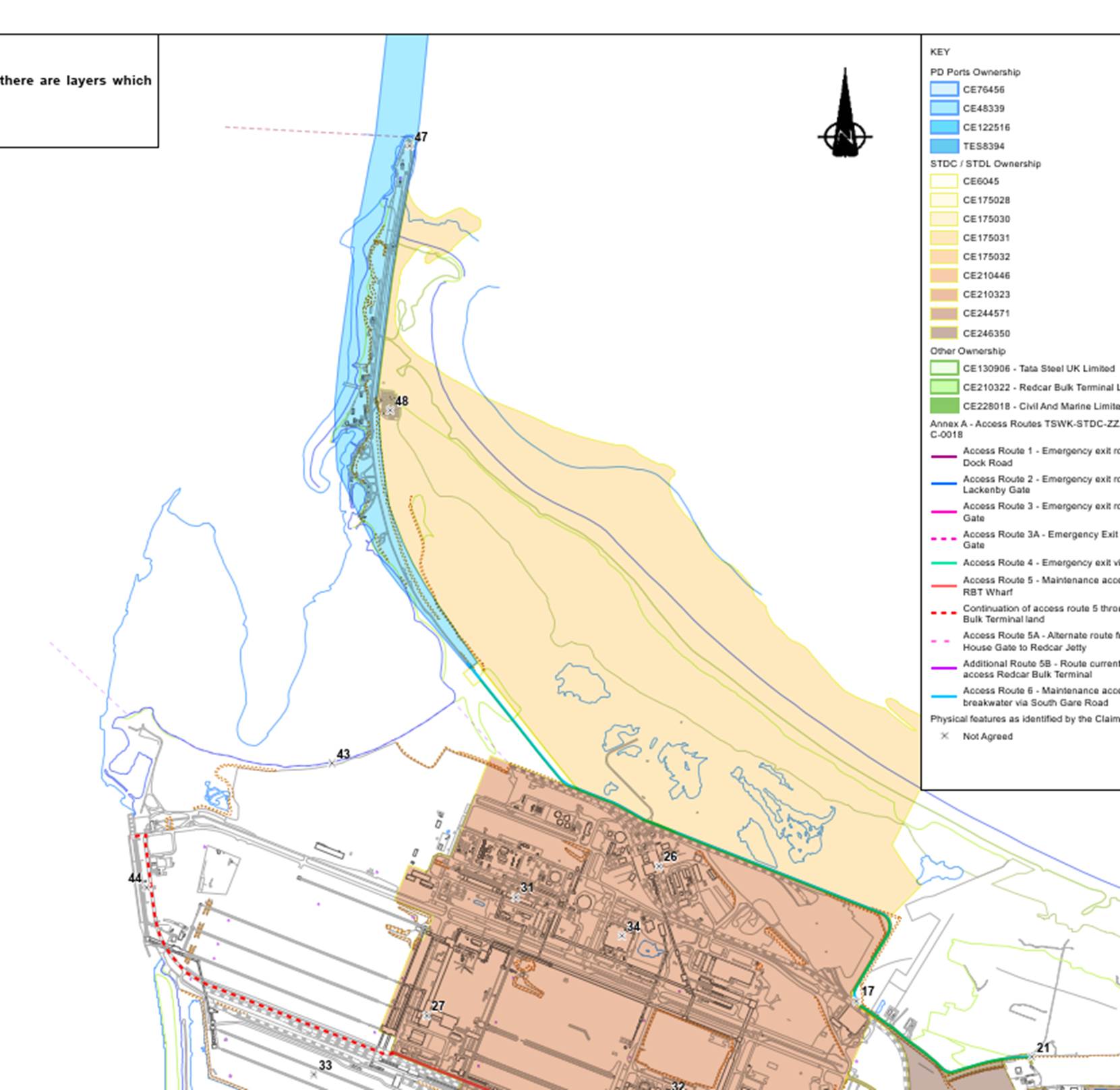

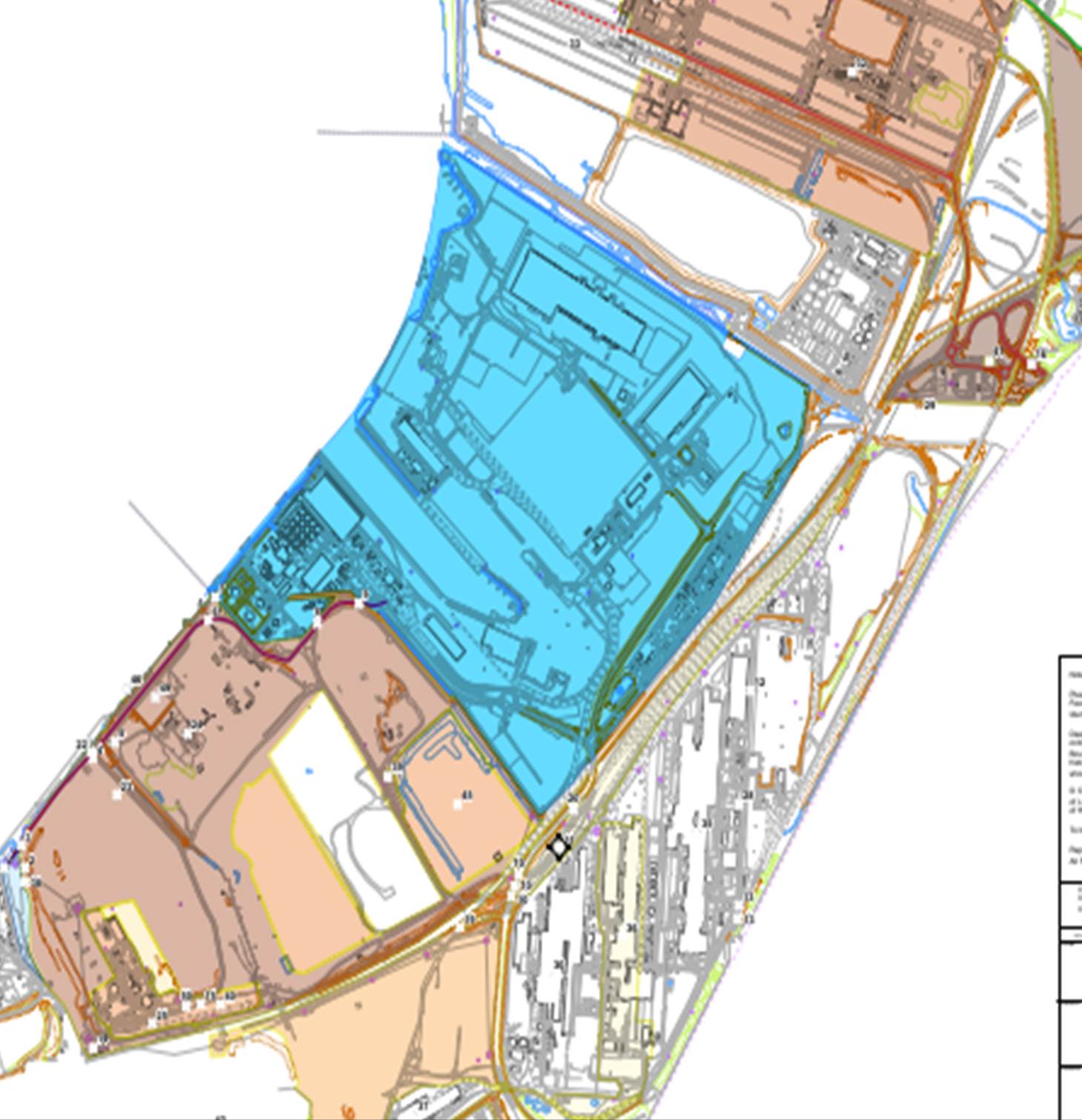

- The STDC parties' land is shaded in yellow and brown on the (north orientated) plan below (Fig 2). D's land is shaded blue. The white land belongs to third parties.

- Cs brought these proceedings seeking negative declarations that D does not enjoy any rights of way across their land. Following Teesworks' acquisition of part of Cs' land in October 2022, it was joined to the proceedings. D, by way of its Counterclaim, seeks positive declarations that it enjoys the benefit of rights of way across that land. D's Revised Schedule of Rights (served in July 2023) identified 15 separate categories of rights claimed, but in its trial skeleton argument D abandoned many of its claims to rights of way and has filed amended pleadings to reflect that. The STDC parties have lain down a marker that they intend to address the costs consequences of this late abandonment of part of D's case at an appropriate juncture. It is common ground that D, as the party seeking positive declarations as to the existence of those rights, bears the burden of proof in the proceedings.

- D's claims relate to three areas: South Gare, Redcar Quay and South Bank.

- D owns the breakwater at South Gare and maintains a lighthouse and other facilities there. The only road access to the breakwater and the lighthouse is along a solitary road, from the lighthouse to where it meets Tod Point Road at Fisherman's Crossing. The road is privately owned. The STDC parties own the road from Fisherman's Crossing to the point where it reaches D's land, and it is owned by D from that point until it ends at the lighthouse. D claims to be entitled to a right of way for all purposes and with vehicles across the STDC's section of the road. In these proceedings, this road has been called "Access Route 6". D's claim is that it has an express right of way granted to it in various conveyances dating back to 1891, and that although the route may have moved or been diverted, it retains a right of way over Access Route 6. In the alternative, D says that it has a prescriptive right arising under the common law from long user.

- D also owns Redcar Quay. This is a bulk ore terminal constructed in the early 1970's which is currently leased to RBT. Redcar Quay has access from the River Tees but is otherwise landlocked. Road access to a highway (the A1085) must cross over land owned by RBT and land owned by the STDC parties – this is Access Route 5. D says that the grant of a right of way is implicit in the conveyance to it in 1971, or under a 1995 lease, but if it is wrong on that then it claims a right of way by necessity under the common law.

- D owns Teesport. The primary access to Teesport is via the Tees Dock Road which connects Teesport to the A66 and the A1065. Tees Dock Road is susceptible to flooding. D claims a right of way along a riverside road, which connects D's land by the highway at Smith's Dock Road (the Smith's Dock Road Parcel shaded light blue in the bottom left-hand corner of Fig 2) to the Tees Dock Road on D's land at Teesport. This is Access Route 1. D claims a right of way by prescription under the common law arising from long user for general purposes, and separately for emergency access and egress when Tees Dock Road cannot be used.

- In relation to Teesport, D also claims a right of way under the doctrine of proprietary estoppel. In order to secure D's agreement to the building of a roundabout which D says encroaches on its land, D alleges it was assured by STDC that it would be granted a suitable alternative access route through the STDC parties' land at South Bank and it has acted to its detriment as a consequence.

- The STDC parties say a complete answer to this claim is that D's predecessor in title did not have the statutory capacity to acquire easements; they seek to amend to plead that point. D opposes the proposed amendment only on the ground that it is without merit and so at the outset of the trial, I directed that submissions on the issue should be made as part of closing submissions and for the application to amend to be considered alongside the other issues for determination in this Judgment.

- Subject to that issue, the STDC parties dispute D's contentions that it has express or implied rights arising from the conveyances as a matter of their proper construction and the law.

- As for prescription, the STDC parties say that D cannot discharge the burden of proof on it in respect of any of its claims. In the alternative, they assert that any period of established use was with the permission of one of them or their predecessors in title or was interrupted by a period of such permissive use.

- The trial was ordered to be expedited. It commenced on 3 October 2023 and lasted for approximately 6 weeks. Unfortunately, attempts to find an available courtroom in Middlesbrough or Newcastle proved unsuccessful, with the consequence that the trial was heard in the Rolls Building in London. Some 34 witnesses, most of them from Middlesborough or the area around it, travelled down to London to give their evidence. Three witnesses – aged 91, 79 and 79 - gave evidence remotely by video conference. I travelled to Middlesbrough to visit the site with representatives of the parties after the trial.

- I heard evidence from two expert witnesses. Mr David Meddings, a chartered land surveyor, gave evidence for the D and Mr Martin Clay, an architect, gave evidence for the Cs. The purpose of their evidence was twofold. Firstly, they provided assistance in the interpretation of contemporaneous documents like aerial photographs and prepared a series of maps and plans showing the present and historical position of title to the land, the routes claimed, and the physical features thought to be relevant. Secondly, they gave their expert opinion on whether the roundabout encroached on D's land.

- The following witnesses of fact were called by D:

- The following witnesses of fact were called by Cs.

- Teesworks called no witnesses, but relied on the evidence called by Cs.

- In relation to the documentation, there were hundreds of deeds, conveyances, office copy entries and other conveyancing documentation, hundreds of historic plans and maps (conveyancing plans, site plans prepared by British Steel or its predecessors, Ordnance Survey maps over the last hundred years), and nearly as many interpretive plans prepared by the experts. There were historic photographs, including aerial photographs and publicly available reports, books and other publications. There were also contemporaneous communications between the parties and internal documentation the bulk of which related to the roundabout and promissory estoppel issues.

- Notwithstanding the vast number of documents in the electronic bundles, it is also clear that I do not have all relevant documents. As appears below in relation to trespass, there are important deeds and plans which are missing. During the course of the trial, it became clear that there is a cabinet system of about 300,000 plans in the possession of British Steel. Although STDC has a licence to access that cabinet system, and some plans were produced from it, a proper search has not been conducted for the purposes of disclosure. There is also a general dearth of internal communications or inter party communications prior to 2002, about D's use of Access Route 1 for emergency use and generally. There is no documentary record of the discussions, which must inevitably have taken place between the THPA and British Steel at the time the road to South Gare was diverted to accommodate the new Redcar steelworks. These are just examples of the gaps in the documentary record. I have to do my best to identify what reliable conclusions can be drawn from this incomplete universe of documents.

- Most of the factual witnesses were called to give evidence on the disputed issues of prescription. In the main, these were patently honest witnesses doing their best to assist the court. However, it is clear that they cannot all be correct because there are countless inconsistencies between their recollections. Memory plays tricks on people. It is perfectly possible for an honest witness to have a firm memory of events which they believe to be true, but which in fact is not correct.

- The well known, and even now, most comprehensive, judicial treatment of the science, is by Mr Justice Leggatt (as he then was) in Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC 3560 (Com m), at paragraphs 15-20.

- Since those comments were made, CPR PD57AC has been introduced in the Business and Property Courts. It requires witness statements in most Business and Property cases to be prepared in accordance with the Statement of Best Practice which is annexed to it. There is a similar warning to that in Gestmin to be found at paragraph 1.3:

- The Statement of Best Practice is intended to guide the preparation of witness statements in line with the science, particularly as to how to access recollections without interfering with them. The rules for examination in chief do not allow leading questions or free use of documents to "refresh memory" and the science suggests examination in chief was a good model for accessing a witness' recollection without corruption. In broad terms, the Statement of Best Practice encourages the preparation of a witness statement in a way which follows the template of an examination in chief:

- All of the witness statements in this case profess to have been made in accordance with CPR PD57AC. The extent to which I consider the Statement of Best Practice has been complied with in respect of each witness, is something which I consider when assessing their evidence. It must be said, however, that even religious compliance with the Statement of Best Practice does not remove the risk of interference with memory.

- D criticises Cs, with some justification, as to the extent to which they have complied with CPR PD57AC. For example, Christopher Briggs was interviewed with Noel Kelly. Noel Kelly did not give evidence. Although the witness statement sets this out openly, it is not what the Statement of Best Practice envisages. The witness statement does not say, as Mr Briggs said in cross examination, that he had been approached to give evidence by David Jones who was also present during the interview. Mr Brigg's witness statement was not solely his evidence, but included words and recollections from others. It was a combined effort, and it fails to identify what are his own recollections, or prevent his recollections being interfered with by discussion with others. Like many of Cs witnesses, Mr Briggs was shown documents which would not have satisfied the test for refreshing memory, including the "Out of Gauge" plan, which (as I explain below) is misleading. While I am completely satisfied that he was an honest witness, his witness statement simply did not comply with CPR PD57AC, or its objectives, notwithstanding the purported certificate of compliance. Ms Barton submitted that this non-compliance was unfortunate but not particularly relevant as I had heard the evidence and seen it tested. I disagree for the reasons I have sought to explain above. The manner in which the recollections of honest witnesses are accessed does matter because it can change the recollections of those witnesses without them realising it.

- I also formed the view that David Jones was not being open and transparent about the preparation of his evidence. In his evidence, he admitted being contacted by Mr Musgrave and Mr Corney (who are the individuals behind Teesworks) and for whom he does work, to give evidence. He said that he nevertheless did not have any conversations with anyone about his evidence, apart from Forsters, before he prepared his statement. It later transpired that he had contacted Mr Briggs and Mr Kelly and persuaded them to give evidence, and indeed attended at Cs premises with them and was present when Forsters took instructions for their evidence. He had also seen the "Out of Gauge" plan before he made his witness statement – his explanation that he must have seen it lying around when he was involved in removing papers from the Site for the Official Receiver and remembered it because he had a "snapshot memory" was not credible. I consider it more likely, that someone provided Mr Jones with the "Out of Gauge" plan as part of discussions about his evidence. I noticed that his evidence improved through cross-examination, correcting, and expanding, on what was said in his witness statement. While I do not disregard his evidence, I treat it with caution.

- Although Legatt J's words have been sometimes taken as an encouragement to place no reliance on witness recollection, particularly when there is an abundance of reliable contemporaneous documentation, the Court of Appeal has confirmed that the assessment of the credibility of a witness' evidence should be a part of a single compendious exercise of finding the facts based on all of the available evidence; see Kogan v Martin [2019] EWCA Civ 1645 and Natwest Markets Plc, Mercuria Energy Europe Trading v Bilta (UK) Ltd (In Liquidation) [2021] EWCA Civ 680 at paragraphs 50 and 51.

- Each witness's evidence has to be weighed in the context of the reliably established facts (including those which can safely be distilled from contemporaneous documentation bearing in mind that the documentation itself may be unreliable or incomplete), the motives and biases in play, the possible unreliability or corruption of human memory and the inherent probabilities. Where there is reliable contemporaneous documentation, it will be natural to place weight on that. Where documents add little to the analysis, other secure footholds in the evidence need, if possible, to be found to decide whether it is more likely than not that the witness' memory is reliable or mistaken.

- That is the approach I take.

- The Tees Conservancy Commissioners ("the TCC") was a statutory body formed by the Tees Conservancy and Stockton Dock Act 1852, which inherited the duties of the old Tees Navigation Company.

- The TCC was replaced by the Tees and Hartlepool Port Authority ("the THPA"), which was created by the Tees and Hartlepools Port Authority Act 1966 ("the 1966 Act") .

- A private limited company, the Tees and Hartlepool Port Authority Ltd, was incorporated on 2 August 1991 with the power to acquire the property, rights and functions of the THPA pursuant to s.2 of the Ports Act 1991. On 1 April 2003, this new company changed its name to that of D.

- In this Judgment, I refer to D, the THPA and the TCC together as "D and its predecessors".

- D is a privately owned company with commercial profit-making objectives. It also has a statutory function. The statutory powers and duties of D and its predecessors include:

- Historically, much of the Site formed part of the riverbed or the foreshore of the estuary of the River Tees. Prior to the Victorian period, even above the high water-mark, much of the relevant land consisted of marshes, sands and mudflats unsuitable for construction or industry. That land has been reclaimed from sea, river and marsh by work done by, or under the auspices of the TCC.

- A 2 ½ mile long breakwater was built by the TCC, with a railway line along it. It was formally opened in 1888. A lighthouse and coastguard station were established at its furthest reaches at South Gare. Much of the breakwater has now been incorporated into land reclaimed on either side, but there still remains the last section of it leading to the lighthouse at South Gare.

- The Newcomen family was a prominent family in the area and were significant landowners. Trustees and entities holding that land are involved in many of the conveyances in this case. For convenience, the parties have referred to them as "the Newcomen Estate".

- By 1912, there were two main industries at the Site – shipbuilding and steelmaking.

- The shipbuilder Smith's Dock Company opened a major ship-building yard in 1909, on the western side of Smith's Dock Road roughly where the Teesport Commerce Park is now located. In 1966 Smith's Dock Company merged with another local shipbuilder, Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson ("Swan Hunter"). The ship-building yard remained in active use until its closure in 1987.

- As for steelmaking, a collection of iron works in the area came to be replaced by a succession of major iron and steel manufacturers. By 1865, Bolckow, Vaughan & Co ("Bolckow Vaughan") was producing 1 million tons of pig iron per annum from its factories in the area. It acquired another major manufacturer, Walker Maynard & Co in in 1916 before it was itself eventually subsumed by Dorman, Long & Co ("Dorman Long") which employed 20,000 people in the area in 1914 and opened major new steelworks on the Site. The Iron and Steel Act 1967 brought the fourteen largest steel producers in the UK, including Dorman Long, into public ownership as the British Steel Corporation ("British Steel"). By this point, Dorman Long owned all the land now owned by Cs at the Site and it was vested in British Steel by statutory instrument in 1970.

- Following the nationwide steel strike in 1980 and acceleration of de-industrialisation over that decade, the steel industry on Teesside entered a period of steady decline. In 1999, British Steel (now re-registered as British Steel Ltd) merged with the Dutch steel producer, Koninklijke Hoogovens, and was renamed Corus UK Ltd in 2000 ("Corus"), under whose ownership the Teesside steel operations were mothballed. Corus Group was then acquired in 2007 by the Tata Group, with the effect that Corus was renamed Tata Steel UK Limited ("Tata") in 2010. Shortly thereafter in 2011, parts of Tata's holdings were sold to Sahaviriya Steel Industries Limited ("SSI"), the rest being acquired by Cs in 2019. SSI recommenced steelmaking in around 2012 and operated the Redcar Steelworks, South Bank Coke Ovens and Lackenby works for some time. However, following SSI's insolvency in October 2015 the steelworks were permanently closed.

- In this Judgment, I will refer to STDC and its relevant predecessor in title to the land, namely British Steel which became Corus and then Tata, as "the STDC predecessors".

- An easement is a right a landowner has to use land owned by another (or to prevent it being used), in a particular way. It is an incorporeal hereditament, and therefore a species of land itself. Unlike a personal right (such as a licence), an easement attaches to the land it benefits and the benefit and burden of the easement passes to successors in title to the original parties.

- The essential characteristics of an easement were identified in the Judgment of Evershed MR in the leading case of Re Ellenborough Park [1956] Ch 131 (and recently approved by the Supreme Court in Regency Villas Ltd v Diamond Resorts Ltd [2018] UKSC 57; [2019] AC 553):

- The STDC parties seek permission to amend to raise as a defence to D's claims that between 1 November 1966 and 31 July 1991, THPA did not have the capacity to acquire easements. It is contended that this lack of capacity prevented the THPA acquiring easements by express or implied grant, and further it prevented prescriptive rights arising.

- There is no dispute that the TCC (the THPA's immediate predecessor) had capacity to acquire easements nor that any easements the TCC had were vested in the THPA. There is also no dispute that D has the capacity to acquire easements.

- The STDC parties contend that, unlike the statutes constituting the TCC and D, the 1966 Act which established the THPA, contains no express powers to acquire easements by agreement. It is not suggested there was a reason for removing from the THPA the power to acquire easements by agreement, but it is contended that this is the consequence as a matter of statutory construction.

- The TCC's powers were set out in various Tees Conservancy Acts. An express power to "purchase, but by Agreement only…any Rights of Way or other Easements over [Land adjoining or near to the Tees]" was provided for by section 11 of the Tees Conservancy Act 1863. Section 23 of the Tees Conservancy Act 1867 empowered the Commissioners to acquire by agreement "any Easement, Right, or Interest in or affecting any Lands" which may be required for certain works. Section 9 of the Tees Conservancy Act 1875 provided that persons empowered by the Land Clauses Act to sell or convey certain lands could "grant to the Commissioners any easement …".

- The preamble to the 1966 Act explains that the THPA was being created to consolidate the entire undertaking of the TCC, the Hartlepool Commissioners, the Docks Board, and the entities operating Stockton Quay and Middlesbrough Wharf. By section 12, the THPA was given the duty to take such steps as it considered necessary for the conservancy, maintenance and improvement of the harbour and its facilities and for the reclamation of land. For that purpose, it was given the power (section 12(2)(d)) to "do all other things which in their opinion are expedient to facilitate the proper carrying on or development of the undertaking".

- By section 14(1), the THPA was given the power to "acquire land by agreement, whether by way of purchase, exchange, lease or otherwise" (emphasis added). By section 14(3), the THPA was given the power to "dispose of land…in such manner, whether by way of sale, exchange, lease, the creation of any easement, right or privilege or otherwise, for such period, upon such conditions and for such consideration as they think fit".

- Pausing there, if the question of construction stopped there, I would be inclined to accept that in the context of the permissive empowerment of section 12, section 14(1) was wide enough to permit the THPA to acquire interests in land including easements. This is reinforced by the fact that s. 14(3) is wide enough to permit the THPA to acquire an easement by reservation on a disposal of land. But the matter does not stop there.

- The 1966 Act (section 4(1)) incorporates s.3 of the Harbours, Docks and Piers Clauses Act 1847, which defines "land" as including "hereditaments". The 1847 Act was one of a series of acts consolidating clauses and terms usually contained in other statutes. The Land Clauses Consolidation Act 1845 was another such act, section 3 of which also defines "land" as including hereditaments. Hereditaments was authoritatively determined to include incorporeal hereditaments, such as easements, in Great Western Railway v Swindon and Cheltenham Extension Railway Co (1884) 9 App Cas 787 at 795, 800-803 and 807-809. In doing so, the House of Lords distinguished the obiter remarks in the Court of Appeal of Lord Carnworth in Pinchin v London and Blackwall Railway Company (1854) 43 E.R. 1101.

- I am satisfied therefore, that there is no merit in the contention that the THPA did not have the power to acquire easements by agreement and therefore no merit in the proposed amendments. I dismiss the applications.

- The land at South Gare which is owned by D ("South Gare"), is shaded light blue on the plan above and extends out to sea. Its principal feature is what remains of a narrow breakwater some two-and-a-half miles long, formed by the tipping of millions of tons of slag from local ironworks. Construction began in the 1860s and it was completed in 1888. At its end is sited a lighthouse.

- The area to the east, shaded yellow, belongs to the STDC parties. It is largely undeveloped and is now protected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest under the Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981. There is a group of fisherman's cabins on the STDC parties' land which are licensed out.

- Access by road to South Gare has at all material times started at a point called Fisherman's Crossing (marked 21 on the bottom right corner of Fig 3). When the Redcar Steelworks (shaded brown on Fig 3) were constructed in the 1970s, a new section of road was constructed, which followed the perimeter of the new Redcar Steelworks. This road from Fisherman's Crossing to South Gare is Access Route 6, shown in green on the plan above. Although what is now Access Route 6 first appears on Ordnance Survey mapping in 1980, it is clear enough from an aerial photograph from November 1974 that it was in place on the ground by then.

- D's case is that by a combination of three deeds, it has a complete right of way between Fisherman's Crossing and South Gare along Access Route 6. The three deeds are:

- There has only ever been one access road on and off South Gare via Fisherman's Crossing, but the route has been altered twice: first, in around 1925; second, in around 1974.

- D says that the 1925 Deed gave the TCC a right of way along the then route from A to B, and from B to C, on the plan below ("the 1925 Route"), it already having a right of way from the breakwater (where the words "Tod Point" appear on the plan) to C and on to Fisherman's Crossing pursuant to the 1891 Deed ("the 1891 Route").

- When in 1974 the route was changed again, D says it acquired a right of way by implication over the diverted route in the 1974 Conveyance. The extent of the deviation between the 1925 Route (shown as the red pecked line) and Access Route 6 (shown as the solid red line) can be seen below. The deviation begins at point B on the 1925 route and so D still relies on the 1925 Deed for a right of way from B to C and on the 1891 Deed for a right of way between C and Fisherman's Crossing.

- The STDC parties attack every stage of D's attempted compilation of a complete right of way over Access Route 6.

- In their skeleton arguments for trial, the STDC parties for the first time raised a challenge to D's paper title to South Gare.

- By a conveyance dated 8.9.1863, it seems that the TCC acquired the land from the Crown on which it intended to build the breakwater. A copy of this conveyance has not been found, but it, together with a deed dated 31 July 1869 whereby the TCC acquired parts of what became the breakwater from the Newcomen Estate, was referred to in subsequent conveyancing documents as the root of the TCC's title to the breakwater. From 1863 onwards D and its predecessors have constructed, maintained, used and occupied the breakwater.

- However, the THPA only became the registered owner of South Gare (the land shaded light blue on Fig 3) as a result of a deed of exchange dated 8 May 1980 ("the Deed of Exchange"). By that deed, the Crown conveyed South Gare to the THPA in exchange for the THPA conveying back to the Crown the land it had acquired in 1863. The conveyance plan below shows in pink the land the THPA acquired in 1980 (and D continues to own) and in blue the land that the TCC had acquired by the conveyance dated 8 September 1863 and owned until 1980.

- The STDC parties say that any rights D claims under any instrument to which it was party prior to 1980 cannot have been proprietary rights benefiting the land which D currently owns. Accordingly, D's claim under the 1974 Conveyance (either express or impliedly diverting the 1925 Route) must fail, as the allegedly burdened land did not give access onto D's then land (coloured blue below), but onto the pink land which was then Crown land.

- D does not dispute that the Deed of Exchange suggests that either (1) the Crown conveyed some of the wrong land to the TCC in 1863 or (2) when building the breakwater, the TCC built it partly along the wrong alignment. D says that this is not a point that the STDC parties are entitled to raise on their pleadings, and in any event, this does not lead to the conclusion for which they contend.

- As to the entitlement to raise it, D says that, although the STDC parties had the 1980 Deed of Exchange, they raised no positive case about it in their pleadings, and merely put D to proof of the ownership of South Gare at the date of the 1925 and 1975 Conveyances. These pleas were introduced only by amendment in July 2023, with Teesworks explaining that the amendments "all go to the construction of the relevant documents" in relation to D's case on diversion of the 1925 route. There was no express denial of THPA's title to any relevant land, nor any positive plea based on the Deed of Exchange.

- D rightly says that the STDC parties cannot raise a positive case against D's title to South Gare at the relevant dates, but I do not think that D can ignore the 1980 Deed, and effectively treat the non-admission as an admission. It is right that the STDC parties had the information to plead a positive case, denying D's title rather than resting on a non-admission, but what D cannot say is that on the information it had, the STDC parties should have admitted D's title; see SPI North Ltd v Swiss Post International (UK) Ltd [2019] EWCA Civ 7 at [48]-[49]. While the STDC parties cannot raise a positive case on the 1980 Deed of Exchange, D must still prove a prima facie case of ownership of the Gare at the date of the conveyances on which it relies. D could do that if it could prove a prima facie paper title at the relevant dates from the conveyancing documents. Then no positive case could be advanced to displace that prima facie title. D's difficulty is that it cannot prove a prima facie paper title prior to 1980. D has to rely on the Deed of Exchange to show that D now has paper title to South Gare, but that also shows that it did not have paper title to it before the Deed of Exchange.

- D's response is that so far as the THPA's ownership of the pink land is concerned the 1980 Deed of Exchange was completely unnecessary. This is because, it says, the construction of the breakwater was a clear act of taking possession of the land on which it was built, thereby ousting the Crown's possession of that land. While the TCC and its successors had a statutory duty to build and maintain a breakwater and the facilities there, that gave it no right to enter upon the land of another to do so, so its activities on the land were qua owners. Under the common law, that possession immediately gave the TCC and its successors a prima facie estate in fee simple, good against all the world except for the true owner: see Jourdan, Adverse Possession at para 20-23 et seq. The TCC believed it was the owner of the breakwater and since then it and its successors have maintained the breakwater and acted in all respects as its owners, including in its dealings with the STDC predecessors who have treated it as the landowner. Pursuant to s.1 of the Crown Suits Act 1861 and s. 4 Limitation Act 1939, after 60 years the TCC's prima facie title will have become indefeasible by the Crown. This will have expired at the latest in 1948.

- I accept these submissions that the TCC had a prima facie possessory fee simple from at least 1888. There is no reason in principle why easements cannot be acquired or reserved for the benefit of a possessory fee simple. I also accept that the TCC's possessory title became prima facie inalienable from at least 1948.

- It will require a positive case to disprove that prima facie title to the land and as I have already indicated no such positive case was raised by the STDC parties. I declined to allow Miss Holland to raise a completely new point in her oral closing submissions, based upon s.66 of the Tees Conservancy Act 1875 (prohibiting interference by the TCC with Crown land without written consent). Firstly, this impermissibly raised a positive case and secondly raised a new point for the first time far too late in the proceedings. There might be arguments available to the Crown, if it chose to challenge the inalienability of the TCC's and THPA's title prior to 1980. Those arguments might be based on s.66, and indeed the express recital in the Deed of Exchange which state that the Crown was then the owner of the pink land. I am not convinced they are points which could have been taken by the STDC parties if they had chosen to raise a positive case, and they do not appear to affect the TCC's prima facie possessory fee simple.

- The 1891 Deed conveyed a section of reclaimed land immediately adjoining the western side of the breakwater from the TCC to the Newcomen Estate. Among the various rights granted and reserved, the Newcomen Estate were granted access across the breakwater (and the railway running along it) to connect their land on either side, and they granted the TCC the following right of way:

- This granted the TCC a right of way to and from the breakwater over a route to be chosen by (at that time) the Newcomen Estate.

- The dominant land benefitted by the right of way is not expressly identified by the 1891 Deed. Where an easement is created by an express grant, there is no legal necessity for it to specify the dominant tenement, but it is essential that there is one. The court will consider the facts known to the grantor and the grantee at the time of the grant, to identify the dominant tenement and its extent. The breakwater at this point was in the ownership of the TCC and was its means of access to South Gare. This right of way appears to be the only road access to the breakwater and was for the TCC's tenants, servants and workmen. The purpose of obtaining access to this point of the breakwater must have been to thereby gain access to the rest of the breakwater and the land it accessed. I determine that the dominant tenement included South Gare and not just the part of the breakwater immediately adjacent to the cottages.

- D says that the plan to the 1925 Deed (Fig 4 above) shows that the chosen route (at least by 1925) was over Fisherman's Crossing, through an archway under the Jetty Railway at point C and then along the yellow track or road to the breakwater where the words "Tod Point" appear on the plan.

- The STDC parties dispute that point C (the archway) to Fisherman's Crossing was part of the chosen route pursuant to the 1891 Deed. They point to a map in 1893 showing the existence of other routes between the cottages and Fisherman's Crossing. Nevertheless, I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that D is correct. D's contention is consistent with the 1913 OS mapping and the plans to the 1917 Agreement, the 1917 Deed and the 1925 Deed. It is clear from those documents and others, that the 1925 Route was an extension of the by then existing road from Fisherman's Crossing to the archway.

- The STDC parties also say that any right of way from Point C to Fisherman's Crossing is not a right of way for vehicular access. However, there is nothing in the 1891 Deed to restrict the use of the right of way, and unless there is something in the context or factual circumstances which indicates otherwise, it is a general right of way for all purposes for which the way was suitable; Kain v Norfolk [1949] Ch 163 at 168, Cannon v Villiers (1878) 8 Ch D 415 at 420-1. There is nothing in the context to indicate that a restriction to non-vehicular access was intended. At the time of the 1891 Deed, the STDC parties say, labourers employed by the TCC probably travelled on foot or by bicycle. Even if that be right, I have no reason to think that the route was only to be used by labourers and not also by supervisors, surveyors, engineers, and others who might be accustomed to travelling by horse, cart or carriage. The right of way extends to the village of East Coatham some distance away, and it would have been reasonable for those who were able, or enabled by the TCC, to use a horse or cart to travel to and fro and transport tools and material. There is also nothing in the evidence to indicate that a right of way for vehicles was not suitable. As discussed below, by 1917 there was a tarmac road which it seems may have been 20 foot wide (that being the width of the extension to it).

- The route was changed in 1925, apparently to enable Dorman Long to redevelop and considerably expand Coatham Iron Works.

- By an agreement for sale and purchase between the TCC and Dorman Long, dated 14.8.1917 ("the 1917 Agreement"), so far as relevant to the right of way:

- By deed dated the same day ("the 1917 Deed"), Dorman Long acquired ownership of points A to B of the 1925 Route from the Newcomen Estate. As to the balance (points B-C), they were granted a right to extend the road "together with a perpetual right of way ... for [Dorman Long] at all times and for all purposes over the said extended road". This was neither the acquisition of the land, nor the procuration of a perpetual right of way for both Dorman Long and the TCC that the 1917 Agreement envisaged.

- The road was built and the 1925 Deed was made. By clause 1, the TCC were purportedly granted a right of way for all purposes between points A and C. From that point onwards, the access road to South Gare was the 1925 Route and the existing road joining to the public highway via Fisherman's Crossing. This remained the case until around 1974.

- The STDC parties dispute that the 1925 Deed was effective in giving the TCC a right of way from points B to C. They correctly observe that Dorman Long was not the owner of the land between B and C, instead only having a perpetual right of way over that land. Consequently, Dorman Long lacked the capacity to grant any right of way along that part of the route to the TCC.

- D seeks to get around this problem as follows:

- Ms Barton submitted that, as a matter of construction of the 1917 Deed, it was only Dorman Long's land beyond point A which was intended to be benefitted by the perpetual easement over B-C. I do not agree. The land at A to B was the dominant land benefitted by the easement over B-C. The requirement that the dominant land is in the ownership of the grantee is therefore satisfied. That land was purchased to build a road to replace the existing road to the breakwater, and I do not see any justification for finding as a matter of construction an intention to restrict its use to only accessing some of the land accessed by the previous road beyond point A.

- Nevertheless, I do not accept D's analysis. Where I consider it falls down is in the proposition that, by granting the TCC a right of way over the road between A-B, the TCC thereby became a successor in title to a sufficient part of that land to carry with it the benefit of Dorman Long's easement over B-C. No authority has been produced to support this proposition. An incorporeal hereditament such as an easement is capable of itself being a dominant tenement for the grant of some right which is appurtenant to it; see Hanbury v Jenkins [1901] 2 Ch 401. That is not the issue here, as there is no valid grant of rights by Dorman Long to the TCC over B-C because Dorman Long did not own the land at B-C. The easement over B-C is notionally affixed to Dorman Long's land between A-B as the dominant land. It would pass on a transfer of title to the dominant land comprising A-B (or if the land is partitioned, any part of it; Newcomen v Coulsen (1877) 5 Ch D 133 at 141)) and it can be enjoyed by those occupying the land at A-B. An easement granted over A-B, however, is not a transfer of part of the title to A-B. Nor does it confer rights of occupation of A-B (as under a lease). It is simply the creation of a right to use the land. It does not make the TCC a successor in title of all or part of the land at A-B so that the benefit of the right of way over B-C passes to it.

- D's alternative argument is that if in some way the 1925 grant was ineffective, Dorman Long were estopped by deed from denying that right, which estoppel was 'fed' in 1954, when it became the owner of the road from B-C. Estoppel by deed is a common law doctrine, not an equitable one. Two categories of estoppel by deed were identified in First National Bank plc v Thomson [1996] Ch 231. D relies on the first category only:

- As the STDC parties say, however, there was no "clear and unequivocal" statement in the 1925 Deed by Dorman Long that it owned B-C. The 1925 Deed was in fact scrupulously clear about the extent of Dorman Long's interest. The recitals to it recorded that Dorman Long now owned the land between points A and B in fee simple and had the benefit of a perpetual right of way between points B and C pursuant to the 1917 Deed. Although the deed goes on to express that Dorman Long "as Beneficial Owners hereby grant" the easement over the whole road A-C, that cannot be a clear and unequivocal representation of ownership in light of the explicit recitals. Therefore, insofar as the benefit of a perpetual right of way was insufficient to constitute Dorman Long as a competent grantor, it was not representing otherwise in the 1925 Deed.

- It is still necessary for me to consider the issues in relation to the 1974 Conveyance.

- The route of the access road was changed in around 1974 to facilitate the redevelopment of Redcar Iron and Steel Works by British Steel. The deviation is highly likely to have been agreed between the THPA and British Steel. But there is no evidence of any such agreement and an express right of way over the deviated route must be by deed; s.52(1) of the LPA 1925 provides that "all conveyances of land or of any interest therein are void for the purpose of conveying or creating a legal estate unless made by deed". D therefore seeks to rely on an implied right arising under the 1974 Conveyance to use the new route to get to and from Fisherman's Crossing. It seems to me that if D is correct in its submissions as to the effect of the 1974 Conveyance, it will also remedy the invalid grant in the 1925 Deed of a right of way over B-C. Indeed, it would not be necessary for D to rely on either the 1891 Deed or the 1925 Deed at all, as an implied grant in the 1974 Conveyance would give it a complete right of way over the STDC parties section of the road to South Gare.

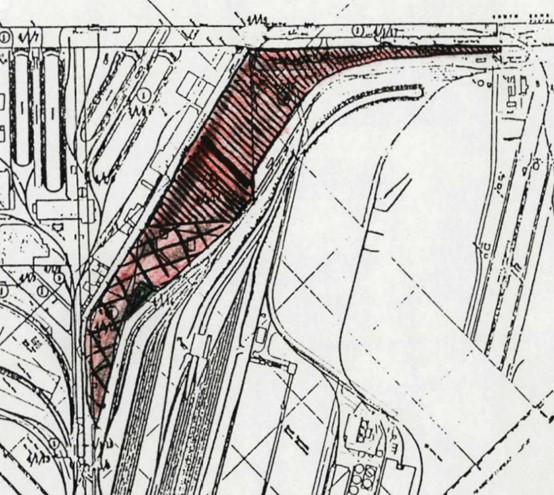

- By the 1974 Conveyance, the THPA sold part of the breakwater to British Steel. This is the land marked dark blue on the plan below prepared by the experts from the conveyance plan ("the 1974 parcel").

- Over the northern part of the 1974 Parcel, the THPA reserved to itself "the right for [the THPA] to pass and repass at all times with or without vehicles plant and equipment over and along the area [marked on the conveyancing plan] for all purposes until such time as the Corporation is able to grant to [the THPA] an alternative right of access acceptable to [the THPA]". This area ends where the new route (marked on the plan in light blue) meets the land being conveyed to British Steel, so seems to have been intended to provide for the continuation of the THPA's access to South Gare from Fisherman's Crossing along the new route which had by then been constructed.

- D says it would have been absurd for the THPA to reserve a right of access that could be used only to travel between South Gare and the end of the land over which the right was expressly reserved. D submits that a grant by British Steel in favour of the THPA over the rest of the route can be implied as a matter of the application of the rules of construction to the 1974 Conveyance. Those rules, as they are now understood, are that the interpretation of a contract is the ascertainment of the contract's meaning to a reasonable person with all the relevant background knowledge. A term which is not in the written contract can only be implied if the court finds that the parties must have intended to include that term in their agreement; it is not enough that it is a term that reasonable parties would have agreed to if it had been suggested to them. It must be a term which is necessary to give the contract business efficacy or be a term which is so obvious as to go without saying; Marks & Spencer Plc v BNP Paribas Securities Services Trust Co (Jersey) [2015] UKSC 72.

- In the context of easements, it may be said that these principles of construction find expression in the explanation of Lord Parker of Waddington in Pwllbach Colliery Co. Ltd v Woodman [1915] A.C. 634 {AU/81} at 646–7:

- In Stafford v Lee (1992) 65 P. & C.R. 172, Nourse LJ explained in relation to the second class of cases at p.175:

- It seems to me that an application of the principles in Pwllbach, should not be allowed to detract the court from the primary exercise which it is undertaking, namely ascertaining the meaning of the document to a reasonable person, including the implication of terms a reasonable person would conclude that the parties must have intended to include in it. No doubt most circumstances which fall into one or other of the two heads referred to by Lord Parker will also satisfy the ordinary rules of construction. But it is possible that there will be cases where they do not. It seems to me that this is one such case.

- On the face of it, both heads of classification in Pwllbach are engaged. Firstly, the reserved right was a right of way over part of the road to access D's land at South Gare (the 1974 Conveyance refers to the reserved right continuing until "an alternative right of access" is made available). That right could only be used or enjoyed if there was a right to get to that section of road over the rest of the road from Fisherman's Crossing. Secondly, the relevant background includes the long-established use by the THPA of its land at South Gare to maintain the marine facilities there (including a breakwater, a lighthouse, a coastguard station, a pilot station, a radar and radio installation, a marina and fisherman's cabins). A reasonable person would infer that the THPA and British Steel intended that use to continue. Access to South Gare, and a right of way over that part of the route, which was owned by British Steel, was necessary for that use.

- However, the problem with D's submission seems to me to be that the 1974 Conveyance is a discrete and limited transaction – it deals with the conveyance of the 1974 parcel by the TCC and matters consequential upon it and nothing else. Save for an express reservation of a right of way over the new route on the part of the land sold on which it ran, there is no reference in it to the new route or to British Steel's land over which the new route ran. It is perfectly business efficacious, in achieving its apparent object of conveying the 1974 parcel and dealing with matters arising from that. There is no need to imply a term to give it business efficacy. It is impossible to say that it is obvious that the parties intended British Steel to grant a right of way over the rest of the route by this document. On the contrary, it seems to me to be quite clear from the document that there was no such intention. There is a deliberate and careful reservation over part of the route, which shows the draughtsman and the parties (who were sophisticated landowners) had the route well in mind but made no attempt to make provision in respect of the rest of the route. That appears to have been deliberate. It may be that it was intended that further documentation would be executed with a grant of such a right of way. It may be that there was a mistaken assumption, that the THPA already had a right over the remainder of the route. Neither are matters which can be corrected as a matter of construction, as opposed to, say, by an estoppel by convention (which is not pleaded or contended for).

- D has therefore failed to establish an implied grant of a right of way in the 1974 Conveyance.

- D has failed in its attempts to compile a complete right of way across Access Route 6 from the three deeds.

- On one of the plans prepared by D's expert the 1974 parcel does not connect to the rest of D's land at South Gare. There is no suggestion of any gap on Cs' expert plans and nobody suggests that any gap was intended. I am satisfied that this is a drawing error by D's expert.

- Redcar Quay is the land marked blue on the plan below. The yellow and orange land belongs to the STDC parties. The only road access to Redcar Quay is marked in red and pecked red – Access Route 5. The white land between Redcar Quay and the STDC Parties' land coloured yellow, and which Access Route 5 crosses in pecked red, belongs to RBT.

- From around 1969 there were plans to redevelop the Redcar site, replacing the original ironworks with a modern steelworks facility. Part of the redevelopment of the Redcar ironworks was the construction of a new ore quay and terminal. This required extensive excavation of the riverbed to permit access from ships with higher deadweight tonnage than had previously been possible, and the reclamation of the tidal flats on which the new Redcar steelworks would be constructed.

- Land was transferred by British Steel to the THPA to build the quay, with the intention that the THPA should lease it to British Steel to be used in conjunction with the facilities being constructed by British Steel at the site. A number of papers were prepared by the engineers, who built the quay or worked on the unloading and distribution system, from which it can be seen that the quay was intended to receive the importation of 7 million tons of foreign ore per annum and then distribute it by rail to ironmaking plants in Cleveland, Hartlepool, Consett and Workington. The unloading and distribution system used a conveying system to move the ore from the quay to the wagon loading station, where a purpose-built fleet of tippler railway wagons could be loaded with ore. What was eventually to become Access Route 5, featured in early drawings before work was commenced, but the road was not the intended distribution method for the ore. Access Route 5 was partially complete in 1974 and first appears in completed form on the historical mapping in 1980. Prior to Access Route 5's completion, there must have been other road access – there are references in the engineering reports to 1.1 million cubic metres of blast furnace slag being brought in by road to reclaim land for the quay.

- By a conveyance on 26.5.1971, British Steel conveyed the Redcar Quay to the THPA ("the 1971 Conveyance"). This reserved a right of access to British Steel in order to provide and install unloading equipment "for use in connection with the Quay about to be constructed by the Purchaser on the said land". In fact, it seems construction had already begun by the date of the 1971 Conveyance. At the time of the 1971 Conveyance, British Steel owned all of the land over which Access Route 5 now runs.

- Redcar Quay was then leased to British Steel by the 1974 Lease, which demised Redcar Quay for a term of 20 years from 17.06.1973. It reserved a right for the lessors to use the quay for other traffic. In 1995, the 1974 Lease was renewed for a term of 40 years from 17.06.1993 ("the 1995 Lease"). It included the same reservation permitting use of the quay by D:

- D does not claim to enjoy the benefit of any express rights of access to Redcar Quay, nor is any prescriptive claim pursued. Instead, D says an easement arises by way of implication into either the 1971 Conveyance or the 1995 Lease. D puts its case on rights of access to the Redcar Quay on three bases:

- I have set out earlier in this Judgment, the principles applied by a Court in the construction of a document and the implication of terms. I have also referred to the principles of construction, as expressed in the context of an implied grant of an easement in Pwllbach and Stafford v Lee.

- It is clear that the common intention of British Steel and the THPA at the time of the 1971 Conveyance, was that the new Redcar Quay would be built and operated as a quay. The 1971 Conveyance itself referred to "the Quay about to be constructed" and it is identified as a proposed quay on the plans to the 1971 Conveyance.

- D submits that a right of way between the land on which the Quay was to be built and the public highway was necessary, to give effect to that intended purpose. The quay could not have been built, nor could it be operated, without it. Operation as a quay means operation for the unloading and/or loading of goods or materials between ship and land, to enable their transportation onwards: landward access to and from the public highway is an essential part of this. Such landward access was also needed to bring the plant and materials required to build it; and it would have been known that it would continue to be needed for the people, plant and materials required to operate and maintain it.

- The STDC parties answer to this is that the Redcar Quay was intended to be leased to British Steel and operated by it – so the THPA did not need access. Secondly it was to be operated by British Steel as a quay servicing its ore storage and distribution facilities at Redcar. Road access was not required for the unloading and distribution of ore which was intended to be dealt with by the conveying system and railway.

- It is clear that the common intention of the vendor and the purchaser to the 1971 Conveyance was that the land would be used to build a quay which would be used as a quay in conjunction with the ore facilities. The construction of the quay is long since complete and any implied right of access for that purpose is now irrelevant. The question is whether D can prove that road access is necessary for its use as a quay in conjunction with the ore facilities.

- The fact that the operator of the quay might be British Steel, as lessee, who owned the adjoining land does not seem to me to be an answer. The question is not whether the THPA needed access to the quay when it was going to be let to British Steel, nor is it whether British Steel needed a right of way when it owned the adjoining land. The question is whether road access is necessary for the use of Redcar Quay as a quay.

- The answer to that question seems to me to also be clear - yes. The quay needs to be maintained. The plant and machinery on it need to be serviced, renewed and replaced. The quay needs to be staffed. For that reason alone, road access is and always has been necessary for its ordinary use as a quay. A reasonable person would conclude that the parties intended there should be road access for that purpose.

- In principle operation as a quay also requires road access to enable goods to be delivered for loading or distributed after unloading. In this case, the quay was intended to be used in a specific way in conjunction with the ore facilities. Road access was not generally required for the unloading and distribution of ore, which was intended to be dealt with by the conveying system and railway. There might still be a requirement for road access for its use in conjunction with the ore facilities – I can conceive that it might be necessary to use road distribution if the conveying system fails or there is a problem with the railway, or for distribution to a plant which was not serviced by the railway. There is no evidence of that before me.

- It might be said that, at some point in the future, Redcar Quay may not be used in conjunction with the ore facilities. It might be used for some other purpose for which road access is necessary to load and unload goods. I do not think that assists D. It is not enough for D to show that Redcar Quay might be used in this way in the future – it has to show that it was the common intention at the time of the 1971 Conveyance that it would be so used; see Pwllbach Colliery. Else it cannot show that the parties must have intended to grant or reserve a right for such future use.

- RBT has not been joined to these proceedings. It has made clear that it has no desire to be included in this litigation. It currently does not take issue with D's use of Access Route 5 over its land to access Redcar Quay.

- The STDC parties say that the absence of RBT is fatal to D's claims in relation to Redcar Quay. They say RBT is a necessary party. Had the STDC parties raised the point timeously in these proceedings, RBT could have been joined and no doubt would have played a minimal role. I do not accept their protestations that it was for D to join RBT. CPR 1.3 requires the parties to litigation to help the court further the overriding objective of dealing with cases justly and at proportionate cost. This requires litigants to take reasonable steps to ensure that there is a common understanding as to the substantive and procedural issues in play; see Abbott v Econowall UK Ltd [2016] EWHC 660. That is not achieved by leaving an issue as to whether the proceedings have been constituted with the right parties until the run up to trial and the skeleton arguments for trial.

- Fortunately, the STDC parties are wrong in their assertion that RBT is a necessary party. It may have been a desirable party, to ensure that it was bound by my Judgment, but it is not a necessary party. No relief is sought against RBT in these proceedings. The only declarations sought are as to rights over the STDC parties' land; and such declarations will be binding on and affect only the STDC parties and their successors in title. RBT will not be bound by my findings in this Judgment. I can take care to fashion an appropriate declaration in respect of D's rights in relation to Redcar Quay so that they do not affect RBT.

- There is a risk that one day there will be another trial to vindicate a right of way over the land owned by RBT. There is a risk that at that trial, the judge will reach different conclusions to me on different evidence. That is undesirable, but I consider that there remain pressing reasons for continuing in the absence of RBT, in particular to resolve the current dispute which is as between the STDC parties and D.

- I conclude that there is an implied grant of a right of way in the 1971 Conveyance, for the purpose of using Redcar Quay as a quay where the primary system of loading and unloading does not generally require road access.

- It is not necessary to consider D's fall-back arguments for an easement of necessity or a limited easement arising under the 1995 Lease and I do not do so. These arguments would only arise if I am wrong that road access is needed for the intended use of the land in 1971. At this stage, it is not clear to me what counterfactual I should use for analysis of the fall-back arguments.

- On 3 December 1946 Swan Hunter conveyed to the TCC certain land beside the River Tees on the South Bank ("the Swan Hunter Conveyance"):

- The same route was previously the subject matter of a grant by virtue of a conveyance dated 4 February 1924 from Bolckow Vaughan to Swan Hunter. Bolckow Vaughan (owners of the servient land) reserved the right "at any time it becomes more convenient as necessary for them to do as to close divert or otherwise alter the road between points marked A and B hereinbefore referred to and provide other road access to the said piece of ground".

- At the time of the 1924 grant, the southernmost portion of the route ended at Grangetown Station, where it was connected to the public roadways via an underpass. By 1953, the underpass had ceased to exist. There is no conclusive evidence as to when the underpass ceased to exist and it seems to me that the Swan Hunter Conveyance itself is evidence that it continued to exist as at its date in 1946 and the right of way granted continued to have utility to the dominant land at the time of the grant. In other words, the Swan Hunter Conveyance created a valid and binding easement over the identified route.

- However, it is fair to say that route has ceased to be of any utility long ago. The road itself has now disappeared (although D points out that Bolckow Vaughan and its successors were entitled to move the route). D says it is nevertheless entitled to a declaration of its continuing right under the Swan Hunter Conveyance.

- The STDC parties raised a number of points in their pleadings, including laches, which were not pursued in closing submissions. They were refused permission to amend to plead abandonment and extinguishment. They say that D has stood back and allowed the STDC predecessors to act on the burdened land, without making any assertion of these rights until its counterclaim in these proceedings. In that context, they submit that the Court should decline to grant declaratory relief – the granting of declaratory relief being discretionary; Rolls Royce plc v Unite the Union [2009] EWCA Civ 387.

- In circumstances where D has established a subsisting right which the STDC parties are unwilling to recognise (and indeed seek a declaration that it does not exist), it would require some exceptional reason for that right not to be vindicated by the grant of declaratory relief. I do not regard the alleged delay, in circumstances which do not affect the validity of the subsisting right or fall within one of the established doctrines for preventing the assertion of the right (such as laches or estoppel), to be sufficient grounds in this case for refusing relief.

- On 26 December 1964, by a Deed of Exchange ("the 1964 Deed") the TCC acquired a rhombus of land south of the oil jetty and oil tanks, together with a right to construct an entrance to Access Route 1. In the First Schedule, by paragraph 7, it defined the land to be conveyed by reference to a plan ("the Rhombus"). By the following paragraph at 8 it also granted an express right of way as follows:

- The rhombus is hatched in dark blue on the plan below and the express right of way is marked in red.

- Cs accept that D, as owner of the Rhombus, enjoys this express right. Teesworks does not dispute that D has this express right, but objects to the way the claim is pleaded and says it should be dismissed.

- Teesworks objects to the fact that paragraph 37(1) of the Re-Re-Re-Amended Defence to Counterclaim ("the RRRADCC") asserts that, "Teesport has the benefit of the rights granted by" the 1964 Deed and Teesport is defined elsewhere in the RRRADCC as all of D's land at Teesport. Mr Walker has conceded that he only contends that the Rhombus benefits from this easement. Ms Holland maintains that D is not entitled to the relief as sought. The relief sought in D's RRRADCC is "A declaration that D has a right to use the Defendant's 1964 Right of Way as defined in paragraph 37 of the Defence". Absent amendment to paragraph 37, she says, D cannot make out its case and it must be dismissed.

- In fact it is paragraph 37(2) that defined "the Defendant's 1964 Right of Way". It defined it as the right of way in paragraph 8(a) of the First Schedule to the 1964 Deed and quoted the excerpt set out above at paragraph 130. It is silent as to which land benefits from the easement. I see nothing that Teesworks can say requires amendment in that definition of "the Defendant's 1964 Right of Way" and therefore nothing which requires amendment in relation to the relief as sought in the prayer. I can address any legitimate concern Teesworks might have as to the land benefitted in the form of the order.

- I accept Mr Walker's concession of a lesser case as to the land benefitted without requiring further amendment to the pleading. It would be disproportionate to do otherwise.

- D also claims a right of way along that part of Access Route 1 between the 1964 Parcel and Smith's Dock Road. The claim is that such a right was implied into the 1964 Deed by s.62 of the Law of Property Act 1925.

- S.62 contains general words which, in the absence of a contrary intention, are implied into a conveyance. In particular s.62 passes to the transferee all rights and advantages which at the time of the conveyance appertain or are reputed to appertain to the land or are enjoyed with the land conveyed or part thereof. The effect of s.62 may be to create new easements by way of express grant where there were previously only quasi-easements. There is no requirement for the right or advantage to be necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the land.

- The section envisages something which exists and is seen to be enjoyed as a right or advantage; Nickerson v Barraclough [1981] Ch 426. There needs to be a pattern of regular use. Where there has been no use at all within a reasonable period preceding the date of the conveyance s.62 cannot operate to create an easement; Wood v Waddington [2015] EWCA Civ 538 at [52].

- Access Route 1 was complete and in use by the time of the 1964 Deed. At that time, Access Route 1 was wholly owned by Dorman Long. D says that in addition to the express right of way under the 1964 Deed, from the Rhombus to the Tees Dock Road, it has an implied right pursuant to section 62 in the other direction, to reach Smith's Dock Road.

- Prior to the 1964 Deed, the Rhombus had been leased by Dorman Long to ICI and Shell – so there was diversity of ownership. It is not therefore necessary to show that the right or advantage was continuous and apparent in the sense used in the rule in Wheeldon v Burroughs (although a made up road has been described as the "easiest case" of a continuous and apparent right; see Hansford v Jago [1921] 1 Ch 322 at 338).

- The STDC parties suggested that there was no access point from Access Route 1 to the 1964 Parcel before the 1964 Deed. The language of the 1964 Deed, suggests that some sort of construction work was to be carried out at the intended access point from the Rhombus to Access Route 1. However, a Layout plan of Teesport in 1958 shows an entrance to the Rhombus was already there and the plans to licences granted by Dorman Long to ICI in 1962 and July 1964 also show it and describe it as the "main ICI access".

- D's difficulty, however, is that there is no evidence at all of use by Shell and ICI of Access Route 1 to get to the Smith's Dock Road prior to December 1964. Mr Walker says that there is no evidence that Dorman Long had a right of way over the Tees Dock Road and could only have provided to its lessees with access along Access Route 1 to Smith's Dock Road. Whatever rights Dorman Long had (or indeed Shell and ICI might have independently had), it is clear from the licences referred to above that the intended route of access and egress to the Rhombus was via the Tees Dock Road and not in the other direction.

- As I explain below when considering the claim for prescription, Access Route 1 was at this time a convenient route to travel to and from Teesport and was open to all. Employees or visitors of Shell and ICI could have used Access Route 1 from the Smith's Dock Road, but I have no evidence that they did. They could also have only used Access Route 1 from the Tees Dock Road because that was the route authorised by Dorman Long. I have very limited evidence as to how the Shell and ICI sites operated and the nature of the traffic to and from their sites; the 1962 licence suggests access to the ICI site was only required (and only authorised) for emergencies, construction and maintenance.

- D has not discharged the burden of proving its claim under s.62.

- PRESCRIPTION

- Prescription describes the common law concept of a legal right over land that is acquired by use or enjoyment for the period and in the manner fixed by law. The right acquired is measured by the extent of the enjoyment that is proved; Williams v James (1867) LR 2 CP 577, 580.

- The manner of the use required is use "as of right" (in the sense of "as if of right"; per Lord Walker in R(on the application of Beresford) v Sunderland City Council [2000] 1 AC 335 at [72]).

- That has the same meaning as the Latin expression 'nec vi, nec clam, nec precario' – without force, without secrecy, without permission. Lord Rodger said of the Latin tripartite test in R. (Lewis) v Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council (No.2) [2010] 2 AC 70 at [87], "their sense is perhaps best captured by putting the point more positively: the user must be peaceable, open and not based on any licence from the owner of the land." In R v Oxfordshire County Council, Ex p Sunningwell Parish Council [2000] 1 AC 335 Lord Hoffman explained: "The unifying element in these three vitiating circumstances was that each constituted a reason why it would not have been reasonable to expect the owner to resist the exercise of the right - in the first case, because rights should not be acquired by the use of force, in the second, because the owner would not have known of the user and in the third, because he had consented to the user, but for a limited period."

- It has been decided at the highest level that "as of right" and the tripartite test (nec vi, nec clam, nec precario) are synonymous in meaning and effect; R(on the application of Beresford) v Sunderland City Council [2000] 1 AC 335 at [6] and [55], R (on the application of Lewis) v Redcar & Cleveland BC (No.2) [2010] UKSC 11 at [20] and [87], Lynn Shellfish Ltd v Loose [2016] UKSC 14, at [37]. Use which satisfies the tripartite test establishes a prescriptive right. There is no further criterion to be satisfied; London Tara Hotel v Kensington Close Hotel Ltd [2011] EWCA Civ 1356; [2012] 1 P&CR 13 (CA) at [28], [74].

- The use must accommodate the dominant tenement in the sense of being connected with the normal enjoyment of the dominant tenement.

- The focus is on the way the land has been used by the users and the quality of that use; Redcar per Lord Brown at [100]. The use in question must have the quality that the users have used it as one would expect those who had the right to do so, to have used it; Redcar per Lord Kerr at [116]. It must be of such amount and in such manner as would reasonably be regarded as the assertion of a right; Redcar per Lord Hope at [67]. It is judged by how the use would have appeared to the reasonable owner of the land; Redcar per Lord Walker at [30] and [36], London Tara per Neuberger LJ at para [29].

- It does not matter what the owner of the land and the users of the roadway actually think as to who the user is or why or on what basis the use is occurring. The subjective understanding and intention of the person or persons when enjoying the amenity now claimed to have been acquired by prescription is irrelevant; Sunningwell, per Lord Hoffman at 356A-D. The subjective understanding and intention of the owner of the land is equally irrelevant; London Tara per Lewison LJ at [60].

- The use must be continuous and uninterrupted.

- The authorities have held that peaceable use is use which is not just without force, but also use which is not contentious, because, for example, the servient owner objects and protests to the use. I do not need to consider this in any detail because it is not pleaded (and although raised in written closing submissions, was by the end of closing submissions no longer contended) by the STDC parties that any of the use relied on by D was contentious.

- The use in question must not have taken place in secret; Redcar per Lord Kerr at [116].

- It is not contended that the use in question in this case took place in secret. If the landowner does not have actual or constructive knowledge of the use, then there may be an issue as to whether the use has been secret, for the purposes of the tripartite test. It is not contended here that the STDC predecessors did not have actual knowledge of the alleged use.

- Use will not be 'nec precario' if there has been some grant of permission by the servient owner, whether express or implied: see Beresford. As to the types of act which may be demonstrative of permission:

- The law on prescriptive periods has been described as:

- There are three periods of prescription recognised in English law which operate as follows:

- In this case, D relies on the doctrine of "lost modern grant" in respect of all its claim to prescriptive rights. In short, D must show 20 years of continuous and uninterrupted use. D also relies on s.2 of the 1832 Act in relation to South Gare, but it adds little to its claim.

- I observe at this stage that had there been merit in the STDC's parties' contentions on THPA's statutory capacity I would have had to consider the STDC's parties' submissions that this defeated D's prescription claims. There being a legal fiction that a grant was made pursuant to which the use followed, I would have found that a prescriptive right could still arise, notwithstanding any lack of capacity on the part of THPA to acquire new easements, particularly as use had commenced when the dominant land was owned by the TCC which did have the capacity to receive a grant.

- The dominant landowner (D) has the legal burden of proof of prescriptive use, but if it proves open use then an evidential presumption arises that the enjoyment was as of right - in particular, that it was without permission and not contentious. The evidential burden then passes to the servient landowner (the STDC parties) to prove permission and contention. The STDC parties have pleaded that Ds use was with the permission of one or more of the STDC predecessors. There is no plea of contention.

- Access Route 6, which gives access to South Gare, became fixed on its current route in 1974, but before then there had been a single road giving access for many decades.

- The South Gare breakwater was constructed by D's predecessor and since 1893 has had a lighthouse and a coastguard station at its furthest reaches. A lifeboat station followed in about 1911. A pilot station came soon after. By 1970, there was a radar and radio installation.

- There is no dispute that D and its predecessors have maintained the breakwater, the lighthouse and many of the other facilities since they were put in place. There are written records like the Tees and Hartlepool Port Authority North and South Gares Breakwater study in 1987, which record the history of the breakwater's construction using 135 million tons of slag. As well as the regular need for remedial and maintenance work to prevent the breakwater breaking up.

- Since 1974, the only land access D has had for maintaining the facilities at South Gare has been Access Route 6. The shoring up of the breakwater sometimes requires depositing tonnes of material along it. For example, a recent piece of maintenance required the installation of 100 12-14 tonne armour blocks, requiring a hundred visits by concrete trucks. From 1974 they would have used Access Route 6 to do so.

- In addition, the facilities at the breakwater have had to be maintained. Mr Dalus was D's former General Manager of Engineering, having joined in 2012. He explained that currently there are cyclical checks carried out at South Gare at least weekly and there are records of those checks having been carried out over many years. Maintenance workers will have gained access to the breakwater from 1974, over Access Route 6.

- The facilities at South Gare have been manned and operated by D's employees and others, whose only land access for that purpose since 1974 has been Access Route 6. For example, the pilots who were based on South Gare (by licence from D and its predecessors) until around 2011 when the Government Jetty was washed away. There were multiple pilots on shift all day, every day. They will have used Access Route 6 to get to the pilot station.