1 The Challenge of Disinformation

Historically, the term ‘disinformation’ referred to the escalating information operations conducted by the United States and Soviet Union over the course of the twentieth century. In this Cold War context, disinformation was the discipline of state agents who weaponised both facts and falsehoods to stoke tensions and influence popular opinion within and beyond their rival’s public. It was the work of CIA agents who launched balloons with leaflets over the Iron Curtain as well as the efforts of KGB agents who promoted the conspiracy of a US-manufactured AIDS pandemic.[1]

Today, the term ‘disinformation’ typically refers to many tangled phenomena. For its part, the European Commission emphasises three general characteristics of the contemporary information environment when it talks about ‘disinformation’. First, the Commission acknowledges that state actors still weaponise false or misleading information, but new actors have entered this space, many lured by financial gain.[2] Second, technologies that facilitate instant communication, pseudonymity, amplification, and targeting present a substantial risk for false or misleading information to cause public harm.[3] And third, the diminished influence of traditional journalism outlets and low levels of digital media literacy make mitigation of disinformation more difficult.[4] By emphasising these characteristics, the Commission has charted a policy strategy that prioritises coordinated intelligence, enhanced scrutiny of monetized content, and the availability of relevant and reliable information.[5]

These observations and resultant priorities appear relatively straightforward. Nevertheless, they obscure an ever-expanding range of behaviour and content the Commission seeks to regulate under what it now calls ‘the overarching term “disinformation”’.[6] In its May 2021 ’Guidance on Strengthening the Code of Practice on Disinformation’, the Commission encouraged firms to adopt a wider view of ‘disinformation’ to include ‘disinformation in the narrow sense, misinformation, as well as information influence operations and foreign interference in the information space, including from foreign actors, where information manipulation is used with the effect of causing significant public harm’.[7] From relatively straightforward priorities, convoluted proposals one day come.

While the Commission attempts to parse ‘disinformation’ into regulable elements, elsewhere the term is used as a simple rhetorical weapon. US politicians and pundits notably favour the epithet to discredit and dismiss opponents and opposing views. Fox News pundit Tucker Carlson, for example, warned that ‘CNN itself has become a disinformation network far more powerful than QAnon’.[8] And from the halls of the US Capitol Building, then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi criticised the President and the White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator for ‘spreading disinformation’ about COVID-19.[9] In these examples, the term ‘disinformation’ is inseparable from the speakers’ political perspectives: the speakers draw an ambiguous distinction between themselves and their targets and, in drawing that distinction, cynically exempt themselves from further debate. In short: You’re wrong and the discussion is over.

‘The term has always been political and belligerent,’ observed technology reporter Joseph Bernstein in a provocative essay on ‘Big Disinfo’, his term for the burgeoning counter-disinformation industry.[10] In it, Bernstein argues that ‘Big Disinfo’’s singular focus on technology firms as the cause of ‘disinformation’ shields other powerful actors—politicians and legacy media, in particular—from scrutiny.[11] Viewed in this light, the Commission’s response to the challenge of disinformation—define it, refine it, and encourage technology firms to referee it—either reflects a narrow appreciation of the political nature of disinformation, or an expansive view of the Commission’s own political future.

2 The EU-Level Response to Disinformation

Following the Brexit referendum and the 2016 US presidential election, allegations of disinformation took centre stage. News reports exposed the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal at the same time social media executives appeared before the US Congress to testify on Russian electoral interference.[12] With the 2019 European elections on the horizon, responding to the threat of disinformation became a matter of urgency for the Commission.[13]

That urgency led the Commission to develop a voluntary framework of industry self-regulation known as the ‘EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (2018)’.[14] The original technology firm signatories to the Code were Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Mozilla.[15] They were followed by Microsoft in May 2019 and TikTok in June 2020.[16] The Code defines ‘disinformation’ and sets out five broad commitments for signatories: improve scrutiny of advertisements, ensure public disclosure of political and issue-based ads, ensure the integrity of their services, empower users of their services, and empower the research community. Signatories commit to prepare an annual self-assessment report of their counter-disinformation measures.

The Code is situated within a wider pattern of EU-level promotion of industry self-regulation of online speech. The Code, however, is unique among these frameworks because it aims to address lawful speech. Moreover, many of the broader objectives of the Code are complemented by EU legislation on data protection and audiovisual media services as well as Member State electoral and media laws. The Code is generally not complemented by disinformation-specific legislation in Member States, though laws in Germany and France stand out as exceptions.

In practice, the Commission’s strategy to mobilise private actors to regulate online speech reflects the challenges authors have identified with gatekeeper regulation—namely, alignment of gatekeepers’ information-control processes with fundamental rights. On this point, there are only a limited number of judgments from Member State courts—Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands—which acknowledge the horizontal effect of fundamental rights on the private contracts between users and technology firms. It remains unclear whether courts in other Member States will develop similar responses to private content moderation decisions.

2.1 Self-Regulation: EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (2018)

The Commission took its first steps toward a Code of Practice in January 2018 when it established a high-level group of 39 experts from civil society, social media, news media, and academia to advise on responses to disinformation.[17] After three months, all but one expert adopted a final report which, firstly, defined disinformation as ‘false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented and promoted to intentionally cause public harm or for profit’ and, secondly, suggested a ‘self-regulatory approach based on a clearly defined multi-stakeholder engagement process’.[18]

The lone holdout—the European Consumer Organisation—voted against the report because it lacked recommendations to combat ‘clickbaiting’ and to examine ‘the link between advertising revenue policies of platforms and dissemination of disinformation’.[19] Indeed, efforts to discuss approaches which would examine the role firms’ business models play in the spread of disinformation were reportedly opposed by representatives from Facebook and Google.[20]

Following publication of the group’s report, the Commission convened a Multi-Stakeholder Forum on Disinformation comprised of two different and autonomous groups: a Working Group, made up of the major online platforms and advertising associations, and a Sounding Board, made up of representatives from media, civil society, fact-checking organisations, and academia.[21] The Working Group prepared a draft Code of Practice on Disinformation, while the Sounding Board provided comments and advice.

By the final meeting of the two groups, there was tension in the room. According to the Sounding Board’s spokesperson, the Sounding Board could not support the Code because it ‘lack[ed] quantifiable KPIs [key performance indicators], include[d] vaguely-phrased commitments, and [had] no mechanism to ensure compliance’.[22] Some members expressed a more fundamental concern: who decides what disinformation is?[23] Others considered that continued discussions with the Working Group ‘would not be worthwhile’, while a few Sounding Board members simply walked out of the meeting.[24]

In its unanimous final opinion, the Sounding Board observed that the Code ‘contains no common approach, no clear and meaningful commitments, no measurable objectives or KPIs, hence no possibility to monitor process, and no compliance or enforcement tool: it is by no means self-regulation, and therefore the platforms, despite their best efforts, have not delivered a Code of Practice’.[25] Nevertheless, this final draft of the Code was signed by Facebook, Google, Twitter, Mozilla, and representatives of the advertising industry in October 2018. They were followed by Microsoft in May 2019 and TikTok in June 2020.

The Code defines ‘disinformation’ as ‘verifiably false or misleading information which, cumulatively, (a) is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally deceive the public; and (b) may cause public harm, intended as threats to democratic political and policymaking processes as well as […] the protection of EU citizens’ health, the environment or security’.[26] Paolo Cesarini, a former senior Commission official, suggests that ‘the element of intentionality’ eliminates the risk of creating ‘judge[s] of truth’.[27] This attractive explanation, however, overlooks one of the most obvious risks of the Code’s definition: it designates technology firms as judges of intent. Pielemeier, in an assessment of the Code’s definition, observes that discerning a speaker’s intent online can be incredibly difficult ‘where nuance, jargon, and slang—not to mention the use of different languages—proliferate’.[28] That difficulty is compounded at scale: ‘A one-in-a-million chance [in content moderation] happens 500 times a day’, said Twitter vice president of Trust and Safety, Del Harvey, in 2014.[29]

Additionally, it is not clear how the Commission or signatories conceptualise the potential of disinformation to cause public harm. The Code itself offers no guidance except to equate public harm with threats to democratic processes, public health, the environment, and security. Chase points out that the Commission has only ever cited two sources of ‘essentially opinion- rather than evidence-based’ data to support an actual causal link between disinformation and public harm.[30] They include a synopsis of nearly 3,000 public comments received during the public consultation phase,[31] as well as the results of a Eurobarometer poll related to trust in media, perceived exposure to disinformation, and perceived ability to identify it.[32]

As a practical matter, it may be difficult to establish and measure harm because, as Pielemeir notes, the impacts of disinformation will likely be more diffuse than, for example, terrorist incitement.[33] Still, researchers are taking a bite at the apple. In 2020, Ben Nimmo, a journalist turned influence operations analyst, proposed a breakout scale for researchers to ‘compare the probable impact of different operations in real time’.[34] The scale divides influence operations into six categories which are roughly defined by how many platforms a particular influence operation reaches.[35] Translated to policymakers, the breakout scale suggests that, as an operation infiltrates more platforms, the risk of public harm increases.

The Code also sets out five broad commitments: improve the scrutiny of advertisements, ensure public disclosure of political and issue-based ads, ensure the integrity of their services, empower users of their services, and empower the research community. These commitments are further qualified by allowances for flexible uptake. Signatories need only sign up to the commitments which correspond with their services and technical capabilities. Moreover, on account of differences among signatories’ operations, purposes, technologies, and audiences, the Code ‘allows for different approaches to accomplishing the spirit’ of the commitments.[36] Chase speculates that the Commission acted more like a facilitator, not a negotiator, in this context because disinformation, unlike hate speech, is not illegal.[37]

A common criticism of the Code is that it generally lacks ambition. As Taylor et al observe, the Code is a mirror image of signatories’ existing policies and current initiatives,[38] particularly its ‘Annex of Best Practices’ which links to various community rules and announcements of the original signatories.[39] The European Regulators Group for Audiovisual Media Services (ERGA) has criticised the commitments for creating ‘space for the signatories to implement measures only partially or, in some cases, not at all’.[40] For example, signatories follow different approaches to the identification and disclosure of issue-based ads, perhaps owing to the lack of an agreed-upon definition or understanding of ‘issue-based advertising’.[41] As of October 2019, Facebook was the only signatory with a policy on issue-based ads applicable across the EU, while Twitter’s policy, which included a certification mechanism, applied only to the US (with the exception of application in a single Member State, France).[42]

Moreover, despite the Code’s call for protection of fundamental rights, it fails to put forward any measures to do so.[43] For example, there are no Code commitments to introduce appeal mechanisms for account sanctions or removals. But access to fair processes may do more to legitimise the regulation of disinformation than reports of content removals ever can. Marsden et al note that ‘a very important factor in accountability for legal content posted may be examples of successful appeals to put content back online’.[44]

Other criticisms take aim at the Code’s casual reporting requirements.[45] To monitor the Code’s effectiveness, signatories commit to write annual self-assessment reports to be made publicly available and subject to review by a third-party organisation. But these reports, which firms typically organise around their chosen commitments, tend to use the informal language and selective presentation of data commonly found in corporate press releases. For example, in its 2019 annual self-assessment, Twitter describes its efforts to protect the integrity of its service by listing six statistics whose accuracy and significance are unverifiable. Among them: ‘2.5 times more private information removed with a new, easier reporting process’ and ‘100,000 accounts suspended for creating new accounts after a suspension during January – March 2019, a 45% increase from the same time last year’.[46] In short, the logic of the Code’s reporting and monitoring process is an honour system.

In light of the Code’s imprecise commitments, allowance for flexible uptake, and lax reporting, it is reasonable to expect oversight challenges and poor outcomes. Indeed, after the Code’s first year, ERGA found it was not possible to assess implementation of three of the five commitments—improve the scrutiny of advertisements, ensure public disclosure of political and issue-based ads, and ensure integrity of services—because the data provided was completely inadequate for monitoring compliance.[47]

Signatories’ commitment to empower users produced mixed results. ERGA found that some firms made use of tools like labels and links to trustworthy information, but those tools were not available across all Member States and firms did not provide any data on their use.[48] In addition to developing user interface tools, several signatories participate in media literacy campaigns. However, ERGA found that those campaigns typically ‘involve only a tiny fraction of the total population (mainly journalists, politicians, and school teachers)’ and are concentrated in major cities.[49] In light of signatories’ reluctance to share data—as well as the Code’s presumption of media literacy campaigns’ effectiveness—signatories could easily comply with their commitment to empower consumers by making further investments in these campaigns. Striking a cautiously optimistic note, Butcher notes that the Code’s ‘most important work lies in its long-term measures to increase societal resilience to disinformation’, particularly investments in media literacy.[50]

The research community did not fare any better under the Code. Here, ERGA found that firms developed a variety of relationships with fact-checking organisations, including contracting directly (Facebook), providing technical support (Google), or not officially supporting them at all (Twitter).[51] Where signatories work with fact-checking organisations, it is unclear whether and how the firms used fact-checkers’ assessments.[52] Not only are fact-checkers kept in the dark, as reported by Ananny in 2018,[53] but also the researchers responsible for assessing compliance with the Code. At the Member State-level, for example, Teeling and Kirk were unable to assess the extent to which Facebook’s partnerships with fact-checking organisations reduced distribution of false news in Ireland because the data to make those assessments were not available to them.[54]

On the whole, ERGA found that researchers continue to face ‘enormous difficulties’ gaining access to data, particularly ‘crucial data points’ on ad targeting and user engagement with disinformation.[55] Notably, researchers reported that the ad libraries created by Facebook, Google, and Twitter in response to the Code ‘were inadequate to support in-depth systematic research into the spread and impacts of disinformation in Europe’.[56] While many researchers are concerned with the absence of audience targeting data in the ad library, there are also reports of the libraries’ incomplete data,[57] limited search functions,[58] and mysteriously vanishing political ads.[59]

2.2 EU-Level Response to Disinformation in Context

2.2.1 Industry Self-Regulation in the EU

The Code is situated within a wider pattern of EU-level promotion of industry self-regulation of online speech. It joins the ‘Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech (2016)’ and the Commission’s ‘Recommendation on Measures to Effectively Tackle Illegal Content Online (2018)’, each of which complements national legislation restricting these forms of expression to various degrees.[60] All three of these instruments, observes Kuczerawy, are forms of ‘delegated private enforcement’, which tends to be ‘less visible and less obvious’ than direct state intervention.[61] The Code of Practice on Disinformation, however, is unique among these frameworks because it seeks to address lawful speech such as false news articles, conspiracy theories, and hyper-partisan rhetoric.[62] This speech should be moderated, according to the Commission, because it may cause harm to personal and public health, crisis management, the economy, and even social cohesion.[63] Viewed in this light, the Code bears out Lessig’s warnings about public bodies’ indirect use of ‘code as law’: broadly, the Commission ‘gets the benefit of what would clearly be an illegal and controversial regulation without even having to admit any regulation exists’.[64]

2.2.2 EU Legislation

Many of the broader objectives of the Code are complemented by EU legislation, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD).[65] For example, the Code calls on signatories to ensure transparency of political and issue-based ads, while the GDPR, applied in an electoral context, addresses microtargeting of voters based on unlawful processing of personal data.[66] The Code and the GDPR, Nenadić notes, form a ‘European approach’ to tackling the particular challenge of social media manipulation during elections.[67]

Further, the Code calls on signatories to partner with civil society, governments, and educational institutions to support efforts to improve digital media literacy. On this front, signatories collaborate with fact-checking organisations,[68] distribute grants to media literacy organisations,[69] and work on Member State-level media literacy projects.[70] These activities are one part of a wider European effort (see, for example, the AVMSD) to equip citizens with the skills required ‘to exercise judgment, analyse complex realities and recognise the difference between opinion and fact’.[71]

2.2.3 Member State Electoral and Media Laws

In addition to EU legislation, the Code is complemented by Member State electoral and media laws. Generally, these laws set the ground rules for political advertising on broadcast media during campaign periods, including who may advertise, when, and how much money may be spent. These rules, however, are not harmonised across Europe, nor are they necessarily applicable to online political advertising. For example, in a 2020 comparative study on the regulation of political advertising in the EU, Furnémont and Kevin found that France prohibits online advertising during election periods, Ireland does not specifically regulate online political advertising, and Italy promotes self-regulatory guidelines for equal access to online platforms during election campaigns.[72] Presently, Member States are considering a proposal for a political advertising regulation put forward by the Commission in late 2021 to harmonise rules across the Union and establish a high level of transparency.[73]

2.2.4 Member State Disinformation Laws

With a few notable exceptions, the Code is generally not complemented by disinformation-specific legislation in Member States. One exception is Germany’s Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), adopted in 2017, which requires social media platforms to remove ‘clearly illegal’ content within 24 hours of receipt of a user complaint.[74] Categories of illegal content—including the dissemination of certain propaganda, commission of forgery, and incitement to crime and hatred—are set out in separate statutes. Germany’s approach, Butcher observes, bundles disinformation into hate speech law.[75] Critics of the law argue that it incentivises platforms to remove reported content because they must operate within the law’s tight 24-hour deadline or face heavy fines.[76] Moreover, the law fails to provide for judicial oversight or right to appeal.[77]

Another exception is France’s Law 2018-1202, adopted in 2018, ‘on the fight against the manipulation of information’.[78] The law allows the public prosecutor, any candidate, any party or political group, or any interested person to apply to a judge for an order requiring platforms to take ‘proportionate and necessary measures’ to stop the ‘deliberate’ dissemination of ‘inaccurate or misleading allegations of fact likely to alter the sincerity of the […] ballot in the three months preceding general elections.[79] After receiving the application, the judge has 48 hours to issue a decision.[80] Examining this procedure, Craufurd Smith argues that to establish the subjective intent of the originator, or even re-publishers, will prove ‘all but impossible, certainly in the relevant time-frame for action’.[81] Instead, applicants will have to demonstrate the ‘manifest falsity’ of the information, from which the originator’s intent may be inferred.[82]

2.2.5 Horizontal Effect of Fundamental Rights

The Code, which is premised on the ability of technology firms to control information, reflects a network gatekeeper theory of regulation.[83] Network gatekeepers, according to Barzilai-Nahon, are those entities with the discretion to engage in information-control processes (e.g., selecting, channelling, withholding, timing, and deleting), which they carry out via information-control mechanisms.[84] For example, signatories’ commitment to enforce policies on identity is premised on their ability to suspend or terminate user accounts. But these processes, Laidlaw notes, pose risks to fundamental rights.[85] These rights are enforceable vertically against the state but generally unenforceable horizontally against the private firms at the frontlines of enforcement.

There are only a limited number of judgments from Member States’ courts which acknowledge the horizontal effect of fundamental rights on the private contracts between users and technology firms. Moreover, within this limited case law, the complainants are political parties or elected officials. For example, Kettemann and Tiedeke describe cases in Germany and Italy where courts applied ‘public law in private spaces’ to reinstate the Facebook accounts of right-wing political parties.[86] In both cases, the horizontal application of public law principles (in Germany, equality before the law; in Italy, the right to political participation) to private contracts was supported by the courts’ findings that Facebook had become an essential platform to disseminate political messages.[87]

Where courts have acknowledged the horizontal effect of freedom of expression on these private contracts, however, they do not emphasise that access to the platform is essential to participate in public discourse. For example, a district court in the Netherlands considered whether LinkedIn’s suspension of a Member of Parliament’s account and removal of his posts for running afoul of the company’s public health disinformation policies violated his right to freedom of expression.[88] Weighing the MP’s freedom of expression against the importance of protecting public health, the court emphasised the obligations of elected officials in the context of a public health pandemic: criticism of public policies is a legitimate exercise of freedom of expression, while criticism which undermines such policies is not.[89] The court ordered LinkedIn to restore the MP’s account, but not the removed posts.

Overall, it is unclear how this case law will develop in Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, and whether other Member States which recognise the horizontal effect of fundamental rights will follow a similar pattern. On this latter point, there is reason to doubt uniform national responses. TJ McIntyre, for example, describes a similar lack of clarity in Ireland where the law also recognises the horizontal effect of fundamental rights.[90] Drawing on Irish case law in the public broadcasting context, McIntyre suggests that ‘Irish courts would be reluctant to develop a “must carry” rule which second guessed the policies of platforms’.[91]

2.3 Criticisms of the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation

2.3.1 An Open-Ended Definition of Disinformation

The Code defines ‘disinformation’ as ‘verifiably false or misleading information which, cumulatively, (a) is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally deceive the public; and (b) may cause public harm, intended as threats to democratic political and policymaking processes as well as […] the protection of EU citizens’ health, the environment or security’.[92]

By this definition, which lacks a legal basis, false or misleading information becomes ‘disinformation’ through its interaction with ‘bad actors’: those who disseminate it for economic gain or to deceive. It lays the groundwork for firms to regulate disinformation as a problem of bad behaviour, bypassing the more problematic burden of becoming arbiters of truth.

This open-ended definition of ‘disinformation’ is a politically convenient regulatory trapdoor. It is subject to revision at the Commission’s behest, enforced at the whims of firms on the frontline who shape the definition to suit their own operational and financial needs, and it is shielded from both democratic deliberation and judicial review.

The Commission has begun to call for more nuanced definitions of the challenges associated with disinformation. Citing the COVID-19 ‘infodemic’, the Commission pointed to a need to ‘differentiate more precisely between various forms of false or misleading content and ‘manipulative behaviour’.[93] This echoes policy recommendations made by Chase who emphasises the need to distinguish between disinformation as ‘pieces of content’ and disinformation as ‘disruptive campaigns’.[94] Dittrich acknowledges this distinction as well, but pushes back on its use to broaden the scope of enforcement: ‘[…] the EU should refrain from mandating [firms] to police content directly’ and instead ‘should focus on how [firms] tackle two main drivers of the spread of disinformation, namely fake accounts and inauthentic behavior’.[95]

Nevertheless, in May 2021, the Commission called for expanding the scope of enforcement measures against misinformation, disinformation, influence operations, and foreign interference.[96] Indeed, the Code and its open-ended definition have the appearance of a repository for European security, electoral, and media policies which cannot survive public or legal scrutiny, or simply lack priority.

2.3.2 Private, Ad Hoc Regulatory Tools Lacking Meaningful Transparency

Signatories are given wide discretion to meet their commitments, resulting in the development of private, ad hoc counter-disinformation tools which lack meaningful transparency. They include tools of standard-setting which address false or misleading information, inauthentic representation, and manipulative behaviour.[97] Disinformation standards, however, are routinely criticised as unclear, unstable, and inconsistent across platforms.[98]

They also include tools of human detection and evaluation. In the context of disinformation, this is the work of fact-checking organisations and internal investigative teams. Fact-checking organisations, however, do not have broad coverage across Member States.[99] Moreover, they have evolved ‘highly diversified working practices’[100] and very little is known about how signatories select claims for fact-checkers or how signatories translate the outputs of fact-checkers into indicators of relevance, authenticity, and authority to prioritise information.[101]

Internal investigative teams participate in ongoing monitoring of users suspected of ‘inauthentic’ or ‘manipulative’ behaviour.[102] Their work, however, is not subject to investigative transparency. They publicly report very little detail about how their internal systems flag suspected inauthentic behaviour or the duration of their monitoring activities. Typically, they voluntarily disclose the number of coordinated inauthentic accounts they have terminated as well as the accounts’ affiliations with state or non-state actors.[103]

Finally, signatories apply tools of enforcement to violations. In the context of disinformation, signatories typically apply sanctions to behavioural infractions (e.g., account terminations and suspensions) and lighter touch enforcement mechanisms to content (e.g., recommendation and contextualisation).[104] Account sanctions, however, are not always accompanied by a clear explanation to the affected user, while tools of recommendation and contextualisation, which rely on the work of fact-checking organisations, lack meaningful transparency.[105] Moreover, little is known about whether tools of recommendation and contextualisation actually succeed in countering disinformation.[106]

2.3.3 Lack of Effective Redress Possibilities

Users whose accounts are sanctioned, or whose content is removed, lack effective possibilities for redress. While there is a limited sample of cases from Germany and Italy where courts have given horizontal effect to fundamental rights of equal treatment and participation in order to restore users’ access to Facebook—because of the platform’s ‘significant market power’ (Germany) and its ‘systemic relevance [to] political participation’ (Italy)—national courts, on the whole, have not recognised the horizontal effect of freedom of expression in order to reinstate content.[107]

Germany’s Federal Court of Justice has begun to address this gap in protection by applying a consumer protection framework to platform sanctions. In a July 2021 judgment, the court gave horizontal effect to freedom of expression in a consumer protection context when it considered the reasonableness of Facebook’s terms of service related to deletion of content and blocking of user accounts.[108] First, the court recognised that a platform is entitled to set rules on permissible speech that go beyond criminal prohibitions as well as to remove content or block users when those rules are violated. However, the court observed, a platform’s terms of service, in practice, must reflect an appropriate balance between a user’s freedom of expression and a platform’s freedom to pursue an occupation.[109] Applying that reasoning to Facebook’s terms of service, the court held that the platform’s deletion of content must be accompanied by notices to the user, at least after the fact, while the platform’s blocking of a user’s account must be accompanied by advance notice to the user.[110]

While this case reemphasises the importance of access to a platform’s service, it also makes clear the limitations of a consumer protection framework to safeguard freedom of expression: the court’s emphasis is on the fair application of the platform’s terms of service when removing content, rather than the congruence of the platform’s rules on permissible speech with principles of freedom of expression. In any event, safeguards for freedom of expression at the national level will continue to develop in an ad hoc manner, precluding adequate protection for freedom of expression across all Member States.

3 Co-Regulation Through the EU Digital Services Act

Like the Code, the Digital Services Act reflects the EU-level trend of using firms as network gatekeepers to regulate online speech. This legislation, however, mobilises firms to address the criticisms of self-regulation by requiring them to adopt safeguards of transparency and redress. These due diligence obligations vary according to the function and size of the firm, though the vast majority of the obligations are addressed to ‘online platforms’, particularly ‘very large online platforms (VLOPs).[111]

An online platform, according to the DSA, is ‘a hosting service which, at the request of a recipient of the service, stores and disseminates to the public information’.[112] This describes the services provided by Code signatories Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok. As the platform’s user population expands, so too do its due diligence obligations.[113] Online platforms with a population equivalent to 10% of the EU population are considered ‘very large online platforms’ (VLOPs) which must adopt additional due diligence obligations to manage the systemic risk of disinformation.[114]

Overall, the DSA provides modest improvements to the transparency of counter-disinformation tools. On one hand, it improves the transparency of automatic detection and evaluation tools by requiring intermediaries to publish reports on the precise purposes of their use for content moderation, which must include ‘a qualitative description, a specification of the precise purposes, indicators of the accuracy and possible rate of error […], and any safeguards applied’.[115] It also takes steps toward standardisation of online advertising transparency by requiring ‘clear, concise, and unambiguous’ advertisement labels as well as the development of an online advertising repository.[116] In November 2021, the Commission published a proposal for a regulation on political advertising which will complement these provisions in the DSA.[117]

On the other hand, it is unclear to what extent the DSA reigns in signatories’ interpretation of ‘disinformation’. It may deliver transparency of signatories’ policies on coordinated inauthentic behaviour, but it likely will not shed light on how signatories determine indicators of relevance, authenticity, and authority. Moreover, the DSA fails to address the transparency of the human content moderation behind disinformation—namely, fact-checking organisations and internal security teams. This preserves the opacity of recommender systems, contextualisation tools, and the regulation of coordinated inauthentic behaviour.

Finally, the DSA establishes a system of internal complaint-handling for platforms complemented by a system of independent, out-of-court dispute settlement bodies to resolve content moderation disputes.[118] Each of these systems, however, places the burden on affected users to challenge content moderation decisions. This empowers platforms to act first and answer for it later, if at all. Nevertheless, the independent, out-of-court dispute settlement bodies have the potential to provide valuable feedback on the quality of a platform’s content moderation systems, as well as the clarity, application, and enforcement of disinformation standards.

3.1 Limited Restriction of Signatories’ Interpretations of ‘Disinformation’

To what extent does the DSA create safeguards against signatories’ interpretation of the Commission’s open-ended definition of ‘disinformation’? The DSA delivers transparency of a limited set of signatories’ disinformation standards. Article 12 requires intermediaries to publish ‘information on any restrictions that they impose […] in respect of information provided by [users] […] in clear, plain, intelligible, user friendly, and unambiguous language’.[119] This is an ‘information obligation’ (i.e., policies must be clear and publicly available) limited to those disinformation policies which result in ‘restrictions’.[120]

‘Restrictions’ most certainly include blunt enforcement mechanisms like account sanctions. But do they include more subtle enforcement mechanisms like recommendation and contextualisation which can produce restrictive effects? Even if they are included, Article 12 does not necessarily require signatories to go the extra step to disclose how they define indicators of relevance, authenticity, and authority which inform the use of these tools. Accordingly, the DSA promises transparency of prohibitions against coordinated inauthentic behaviour (routinely enforced through account sanctions), but does not deliver transparency of the indicators of relevance, authenticity, and authority which inform signatories’ enforcement through tools of recommendation and contextualisation.

3.2 Lack of Transparency of Signatories’ Partnerships with Fact-Checking Organisations

Signatories, in varying degrees of coordination with fact-checking organisations, may continue to define ‘relevant, authentic, and authoritative’ information without meaningful transparency of these indicators. This entrenches the opacity of tools to recommend, or prioritise, information, as well as tools to contextualise information, from low-profile labels to conspicuous warnings requiring click-throughs. Although VLOPs must assess the risks of recommendation and contextualisation to freedom of expression, there is no express requirement anywhere in the DSA to disclose how relevance, authenticity, and authority are defined.[121]

Ultimately this is a matter of transparency of how signatories influence fact-checkers’ claim selection, as well as how signatories translate the outputs of fact-checkers’ into indicators of relevance, authenticity, and authority. Signatories may indirectly influence claim selection by filtering potential claims to fact-checkers,[122] and they may directly influence claim selection by placing certain claims off-limits as a matter of platform policy.[123] In terms of translating the outputs of fact-checkers, signatories may use fact-checks to train machine learning or create warnings, rather than simply publishing fact-checks as written.[124] The DSA fails to shed light on these workflows, precluding scrutiny of how indicators of relevance, authenticity, and authority are developed and deployed to prioritise and contextualise information.

3.3 Lack of Transparency of ‘Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour’ Investigations

Despite the promise of Article 12 to provide ‘clear, plain, intelligible, user friendly, and unambiguous standards’ for platform policies—which would include policies on coordinated inauthentic behaviour—the DSA mandates a lower standard of public investigative transparency than what signatories have historically voluntarily adopted. Under the DSA, the problem of intentional manipulation of services as well as practices of ongoing monitoring, are subject to a closed loop of transparency among VLOPs, the Commission, and Digital Services Coordinators.

Presently, signatories publicly report very little about how they detect suspected coordinated inauthentic behaviour. Facebook, for example, has variously referenced ‘internal investigations’,[125] ‘public reporting’ by news agencies[126] and fact-checking organisations,[127] the work of external researchers,[128] and reports from law enforcement[129] as the starting points for user monitoring. While no signatories report on the duration of their monitoring activities, each typically discloses the number of accounts terminated and the affiliation of the network of accounts with state or non-state actors on a monthly basis.[130]

The DSA does not appear to require public disclosure for much of this information. Where it does, it is limited to an annual or semi-annual basis. Article 13 requires intermediaries to report on their total number of account suspensions and terminations, categorised by the type of ‘violation of the terms and conditions […], by the detection method and by the type of restriction applied’.[131] Accordingly, at least once per year (or every six months for VLOPs), intermediaries must publish the total number of account sanctions for violations of coordinated inauthentic behaviour (and related) policies. It is not clear that disclosure of the ‘detection method’ requires any more than reporting a distinction between automatic or human detection. Moreover, there is no requirement to attribute the operation (as many platforms do) or disclose the duration of monitoring activities (which no platforms have reported in the past).

Not even VLOPs’ additional transparency reporting requirements are likely to shed light on this ongoing monitoring. Article 26 requires VLOPs to assess the ‘systemic risks stemming from the design, […] functioning and use made of their services’, including the risk of ‘actual or foreseeable negative effects on civic discourse and electoral processes, and public security’.[132] When making these assessments, VLOPs must analyse ‘whether and how [those risks] are influenced by intentional manipulation of their service, including by means of inauthentic use’.[133] Although Article 33 requires VLOPs to publicly report the results of these risk assessments, it also allows them to remove information from these public reports, including information which ‘may cause significant vulnerabilities for the security of its service’ and information which ‘may undermine public security or may harm recipients’.[134]

At best, the DSA promises ‘comprehensive reports’ published by the Board, in cooperation with the Commission, which identify and assess ‘the most prominent and recurrent systemic risks reported by [VLOPs] or identified through other information sources’ as well as ‘best practices for [VLOPs] to mitigate the systemic risks identified’.[135]

3.4 Inadequate Transparency of Redress Mechanisms

While the DSA establishes a system of redress for content moderation decisions, the transparency requirements associated with this system are essentially limited to annual check-ins: Are the platforms settling content moderation disputes in a timely manner? Are their automated content moderation tools accurate? This precludes adequate oversight of the redress mechanisms which is needed to assess two important processes: whether platforms are making appropriate content moderation decisions and whether users are abusing the redress mechanisms. Although Article 23 of the DSA requires platforms to publicly disclose ‘without undue delay’ their initial content moderation decisions and statements of reasons, this does not address the full picture of content moderation practices, which may involve complaints based on those decisions and subsequent engagement with redress mechanisms.

Ultimately, the DSA fails to provide adequate transparency of users’ complaints and platforms’ resolutions to content moderation disputes. Article 13 requires intermediaries to report annually (VLOPs, semi-annually) on the number of complaints received through their internal complaint-handling systems, the basis of those complaints, decisions taken, median time to take a decision, and the number of instances where decisions were reversed.[136] And Article 23 requires online platforms to report annually (VLOPs, semi-annually) on the number of disputes submitted to out-of-court dispute settlement bodies, the outcomes, median time for settlement, and share of disputes where the platform implemented the bodies’ decisions.[137] These are important disclosures, but they do not fully address the risks presented by platforms empowered to remove content without warning or the risks of users abusing the complaint-handling system.

Firstly, the DSA should mandate disclosure, at the time a complaint is submitted, of the infringing material removed, date of removal, date of complaint, and basis of the complaint. This would facilitate detection of user abuse of the complaint-handling system at a time when intervention is most urgent. Secondly, the DSA should mandate disclosure, at the time a complaint is settled, of the decision of the platform (or settlement body), date of the decision, and the reason for the decision. This would facilitate more comprehensive oversight of the content moderation practices of platforms as well as early detection of the timeliness of the complaint-handling process. For content moderation decisions related to disinformation—where the Commission has called for greater consistency across platforms to reduce the risk of public harm—these additional transparency requirements could also facilitate oversight of content moderation consistency.

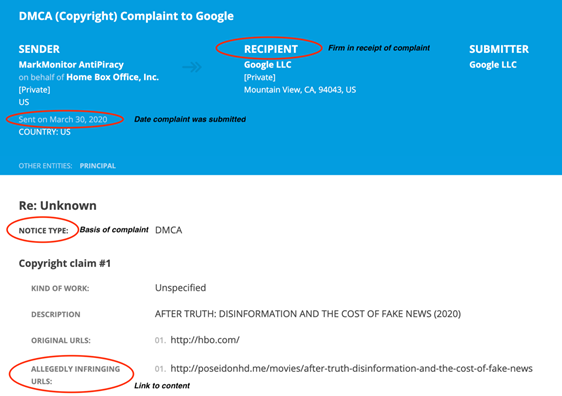

If the DSA mandated disclosure of these elements, the Commission could facilitate the creation of a database similar to Lumen, an independent third-party research project which publishes millions of voluntary submissions of online content complaints, particularly in the context of copyright infringements.[138] These submissions include the date the complaint was submitted, the technology firm recipient of the complaint, the basis of the complaint, and the URL where the content is located.

The information in the Lumen database makes possible research into the content moderation practices of technology firms as well as detection of user abuse of notice-and-takedown systems. For example, after learning of a number of falsified court documents requesting the removal of content, Volokh relied on the resources in the Lumen database to access thousands of court orders submitted to Google and other search firms.[139] Initially, Volokh reported that, over a period of four years, about 200 of 700 court orders submitted to Google were either forged, fraudulent, or highly suspicious.[140] Taking these findings as a case study, Volokh published his observations about designing legal systems to manage the risk of fraud, including the roles of verification processes, deterrent measures, and enhanced public scrutiny.[141]

4 Co-Regulation of Disinformation Through an Article 10 Lens

Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects freedom of expression, is enforceable vertically against the state but unenforceable horizontally against private actors. In the context of regulating disinformation, it is unclear to what extent the content moderation practices of private firms are in fact compelled by public bodies, amounting to state action to suppress speech.[142] Although the DSA requires firms to have ‘due regard’ to fundamental rights in their content moderation practices, this requirement is ambiguous: Some rights are named, while the door remains open to others (Article 12 points to ‘freedom of expression, freedom and pluralism of the media, and other fundamental rights and freedoms […] in the Charter’), and it is unclear what is the practical effect of requiring firms to have ‘due regard’ to them.[143] As Appelman et al asked, does ‘due regard’ effectively require horizontal application of certain fundamental rights between intermediaries and users? Because the DSA does not offer guidance on operationalising this provision, the authors note that ‘[it] might remain too vague to have real effect’.[144]

Nevertheless, the Commission convened technology firms to draw up a Code of Practice and it continues to evaluate their progress and recommend improvements. This encouragement of private regulation of speech should operate with attention to fundamental rights. To that end, Article 10 case law sheds light on the hazards created by the DSA as it relates to the regulation disinformation.

4.1 Insufficient Guarantees Against Abuse

In the case of prior restraints, the Court has held that ‘a legal framework is required, ensuring both tight control over the scope […] and effective judicial review to prevent any abuse of power’.[145] In Ekin Association v France, the Court considered a minister’s powers to impose ‘general and absolute bans throughout France on the circulation, distribution or sale of any document written in a foreign language or any document regarded as being of foreign origin, even if written in French’. Not only did the law fail to define ‘foreign origin’ or indicate the grounds on which such publications may be banned, but the application of the law produced results that were ‘at best surprising’ and in other cases ‘verge[d] on the arbitrary’.[146]

Moreover, because the administrative bans were subject to limited review only upon application by the affected party, the framework provided ‘insufficient guarantees against abuse’.[147] The Court clarified this requirement for effective judicial review in Yildirim v Turkey where it described the need for ‘a weighing-up of the competing interests at stake’ in order to ‘strike a balance between them’.[148] Nevertheless, without a framework that established ‘precise and specific rules regarding the application of preventive restrictions on freedom of expression’, effective judicial review was ‘inconceivable’.[149]

The framework set out by the Code fails to tightly control the scope of content removals and account sanctions (although content removal is not explicitly envisioned by the Code, it occurs in practice). The definition of ‘disinformation’ is subject to ongoing revision at the Commission’s behest and the DSA preserves this arrangement. Indeed, the Commission has called on signatories to update the definition of ‘disinformation’ to include ‘influence operations’ and ‘foreign interference’ with references to vague descriptions of these phenomena.[150]

Still, there is the possibility that the out-of-court dispute settlement bodies established by the DSA have the potential to facilitate ‘tight control’ over the scope of restrictions on disinformation. Article 18 empowers Member States to certify independent, out-of-court dispute settlement bodies to issue non-binding content moderation decisions. These decisions have the potential to perform a corrective function to align signatories’ disinformation policies with fundamental rights principles. Indeed, in its first annual report, the independent Oversight Board for Meta’s content moderation decisions disclosed that the company ‘either demonstrated implementation or reported progress’ for two-thirds of the Board’s non-binding recommendations.[151]

Moreover, content removals and account sanctions are only subject to review upon application by users to the internal complaint-handling system or an out-of-court dispute settlement body. This is an insufficient guarantee against abuse because it empowers signatories to act first to remove content or sanction user accounts, and answer for those decisions later, if at all.

4.2 Lack of Incentives to Avoid Indiscriminate Approaches to Disseminators of Disinformation

While the definition of disinformation is restricted to actors with harmful intent, in practice it is applied indiscriminately against all users who share false or misleading information. The Court has held that ‘an indiscriminate approach to the author’s own speech and statements made by others is incompatible with the standards elaborated in the Court’s case law under Article 10’.[152] This principle has been explored in the context of journalists’ reproduction of statements made by others. In several cases, the Court has held that a distinction must be made between statements emanating from a journalist and quotations of others because to punish a journalist for disseminating the quotations of others would seriously hamper discussion of matters of public interest.[153] The state must advance ‘particularly strong reasons’ to do otherwise.[154]

Accordingly, any framework to regulate disinformation must distinguish between the actors with the intent to cause harm and those who lack such intent. Where an actor without the requisite intent reproduces disinformation, the platform must conduct a balancing exercise of the competing interests at stake in the context in which the disinformation was reproduced. Less intrusive restrictions on that actor should be considered (e.g., use of contextualisation tools).[155]

The Commission’s Guidance on Strengthening the Code sets out a definition of ‘misinformation’—’false or misleading content shared without harmful intent’—and calls on signatories ‘to have in place appropriate policies and take proportionate actions to mitigate the risks posed by misinformation, where there is a significant public harm dimension and with proper safeguards for the freedom of speech’.[156] Appropriate actions including empowering users ‘to contrast this information with authoritative sources and be informed where the information they are seeing is verifiably false.[157]

But this guidance assumes that all contextualisation tools developed by signatories are created equal, that they are effective, and that they do not interfere with expression. Because there is so little known about these tools which continue to be experimented with, it is not possible to say that carving out ‘misinformation’ for proportionate responses will avoid indiscriminate approaches.

4.3 Failure to Mitigate the Risks of Wrongful Takedowns and Removals

The Commission’s definition of disinformation, which is not a legal standard, requires an evaluation of an actor’s motives. In reality, this evaluation is conducted by platforms that want to avoid liability for users’ content, leading them to ‘err on the side of caution and take it down, particularly for controversial or unpopular material’.[158] This is achieved through the work of content moderators, many unfamiliar with the cultural context of a post, who are given just seconds to make an assessment.[159] Consequently, there is a high risk, in the context of disinformation, that harmful posts will be removed irrespective of a user’s motive. This risk makes plain the value of lighter touch content moderation tools like labels and warnings, though their ability to mitigate the harm of disinformation is still unknown. By contrast, there may be a low risk of wrongful removal of users for coordinated inauthentic behaviour because those decisions require analyses of patterns of behaviour. Nevertheless, the DSA does not require transparency of these investigations, which is necessary to avoid wrongful removals of users.

5 Conclusions

By preserving the framework of the Code, the DSA fails to address the Code’s root problem: an open-ended definition of ‘disinformation’ without a legal basis. More broadly, the DSA reflects an uncertainty of how public bodies should regulate the private actors whose content moderation practices affect the exchange of information. This EU-level uncertainty is playing out in parallel to uncertainty among Member States which, with limited exceptions, have not addressed disinformation in national law.

It may be that litigation within Member States shapes the wider European experience. On this front, Germany has proven the most active Member State. Its courts have ruled to restore users’ access to their accounts as well as to reinstate content. It remains to be seen whether its judgments will serve as a model for judicial intervention in content moderation in other Member States, and whether there is potential for a clash between developing national standards and a European approach. European law has yet to consider the question of to what extent informal state pressure brings the actions of private technology firms within the scope of horizontal application of fundamental rights. Further work in this area is required.

[1] Thomas Rid, Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2020).

[2] Commission, ‘Action Plan Against Disinformation’ JOIN/2018/36 final, 5 December 2018.

[3] Ibid 4.

[4] Ibid 9–11.

[5] Commission, ‘Communication on the European Democracy Action Plan’ COM/2020/790, 3 December 2020.

[6] Commission, ‘Guidance on Strengthening the Code of Practice on Disinformation’ COM/2021/262, 26 May 2021 (emphasis added).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Tucker Carlson, ‘Mainstream Media Disinformation More Powerful and Destructive Than QAnon’ (Fox News, 23 February 2021), available at https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/tucker-carlson-media-disinformation-more-powerful-destructive-qanon accessed 27 August 2021.

[9] Adia Robinson and Adam Kelsey, ‘Speaker Pelosi Blames Trump, GOP for Deadlock in Coronavirus Relief Negotiations’ (ABC News, 2 August 2020), available at https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/speaker-pelosi-blames-trump-gop-deadlock-coronavirus-relief/story?id=72121342 accessed 27 August 2021.

[10] Joseph Bernstein, ‘Bad News: Selling the Story of Disinformation’ (Harper’s Magazine, September 2021), available at https://harpers.org/archive/2021/09/bad-news-selling-the-story-of-disinformation/ accessed 26 August 2021.

[11] Bernstein (n 10).

[12] Carol Cadwalladr, ‘“I Made Steve Bannon’s Psychological Warfare Tool”: Meet the Data War Whistleblower’ (The Guardian, 18 March 2018), available at http://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/data-war-whistleblower-christopher-wylie-faceook-nix-bannon-trump accessed 6 August 2021; Cecilia Kang and Sheera Frenkel, ‘Facebook and Twitter Have a Message for Lawmakers: We’re Trying’ (The New York Times, 4 September 2018), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/04/technology/facebook-and-twitter-have-a-message-for-lawmakers-were-trying.html accessed 6 August 2021.

[13] Independent High Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation, A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation (March 2018), available at https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/739290 accessed 6 August 2021.

[14] EU Code of Practice on Disinformation [2018], available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/code-practice-disinformation accessed 6 August 2021.

[15] European Commission, ‘Code of Practice on Disinformation’ (Updated 13 July 2021), available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/code-practice-disinformation accessed 6 August 2021.

[16] Commission (n 15).

[17] European Commission, ‘Experts Appointed to the High-Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation’ (12 January 2018), available at https://wayback.archive-it.org/12090/20210424010927/https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/experts-appointed-high-level-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation accessed 2 September 2021.

[18] Independent High Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation (n 13).

[19] Ibid.

[20] Nico Schmidt and Daphné Dupont-Nivet, ‘Facebook and Google Pressured EU Experts to Soften Fake News Regulations, Say Insiders’ (openDemocracy, 21 May 2019), available at https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/facebook-and-google-pressured-eu-experts-soften-fake-news-regulations-say-insiders/ accessed 2 September 2021.

[21] Commission, ‘Meeting of the Multi-Stakeholder Forum on Disinformation’ (11 July 2018), available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/meeting-multistakeholder-forum-disinformation accessed 2 September 2021.

[22] Commission, ‘Minutes, Fourth Meeting of the Multi-Stakeholder Forum on Disinformation’ (17 September 2018), available at https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2019-4/final_minutes_of_4th_meeting_multistakeholder_forum_on_disinformation_002_67AFE6B9-B872-0AAE-0D090C9AB5EEBC77_56666.pdf accessed 2 September 2021.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Sounding Board of the Multistakeholder Forum on Disinformation Online, ‘The Sounding Board’s Unanimous Final Opinion on the So-Called Code of Practice’ (24 September 2018), available at https://www.euractiv.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/10/3OpinionoftheSoundingboard-1.pdf accessed 2 September 2021.

[26] EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (n 14) preamble.

[27] Paolo Cesarini, ‘Disinformation During the Digital Era: A European Code of Self-Discipline’ (2019) 6 Annales des Mines, available at http://www.annales.org/site/enjeux-numeriques/DG/2019/DG-2019-06/EnjNum19b_3Cesarini.pdf accessed 2 September 2021.

[28] Jason Pielemeier, ‘Disentangling Disinformation: What Makes Regulating Disinformation So Difficult?’ (2020) 2020(4) Utah Law Review 917, 923.

[29] Del Harvey, ‘Protecting Twitter Users (Sometimes From Themselves)’ (TED2014, March 2014), available at https://www.ted.com/talks/del_harvey_protecting_twitter_users_sometimes_from_themselves accessed 16 September 2021.

[30] Peter Chase, ‘The EU Code of Practice on Disinformation: The Difficulty of Regulating a Nebulous Problem’ (29 August 2019) Working Paper of the Transatlantic Working Group on Content Moderation Online and Freedom of Expression 6 <https://www.ivir.nl/publicaties/download/EU_Code_Practice_Disinformation_Aug_2019.pdf accessed 21 December 2022>.

[31] Commission, ‘Synopsis Report of the Public Consultation on Fake News and Online Disinformation’ (26 April 2018), available at https://wayback.archive-it.org/12090/20210728070511/https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/synopsis-report-public-consultation-fake-news-and-online-disinformation accessed 3 September 2021.

[32] Commission, ‘Flash Eurobarometer 464 Report: Fake News and Disinformation Online’ (February 2018), available at https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2183 accessed 3 September 2021.

[33] Pielemeier (n 28).

[34] Ben Nimmo, ‘The Breakout Scale: Measuring the Impact of Influence Operations’ (Brookings, September 2020), available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Nimmo_influence_operations_PDF.pdf accessed 15 January 2021.

[35] Ibid.

[36] EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (n 14).

[37] Chase (n 30).

[38] Emily Taylor et al, ‘Industry Responses to the Malicious Use of Social Media’ (Oxford Information Labs, November 2018), available at https://stratcomcoe.org/cuploads/pfiles/web_nato_report_-_industry_responsense.pdf accessed 9 August 2021.

[39] EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (n14) Annex II Current Best Practices From Signatories of the Code of Practice.

[40] European Regulators Group for Audiovisual Media Services (ERGA), ‘Report on Disinformation: Assessment of the Implementation of the Code of Practice’ (2020) 2, available at https://erga-online.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ERGA-2019-report-published-2020-LQ.pdf accessed 15 September 2021.

[41] Commission, ‘Assessment of the Code of Practice on Disinformation’ SWD/2020/180 final, 10 September 2020.

[42] Commission, ‘Code of Practice on Disinformation: First Annual Reports’ (October 2019) 7, available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/annual-self-assessment-reports-signatories-code-practice-disinformation-2019 accessed 6 September 2021.

[43] Florian Saurwein and Charlotte Spencer-Smith, ‘Combating Disinformation on Social Media: Multilevel Governance and Distributed Accountability in Europe’ (2020) 8 Digital Journalism 820.

[44] Chris Marsden et al, ‘Platform Values and Democratic Elections: How Can the Law Regulate Digital Disinformation?’ (2019) 36 Computer Law & Security Review, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2019.105373 accessed 24 February 2020.

[45] See, e.g., Aleksandra Kuczerawy, ‘Fighting Online Disinformation: Did the EU Code of Practice Forget about Freedom of Expression?’ in Kużelewska et al (eds) Disinformation and Digital Media as a Challenge for Democracy (Vol 6, Intersentia 2019).

[46] Commission, ‘Progress Report: Code of Practice Against Disinformation’ (29 October 2019), available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/annual-self-assessment-reports-signatories-code-practice-disinformation-2019 accessed 6 August 2021.

[47] ERGA (n 40) 17–9, 24.

[48] Ibid 25–7.

[49] Ibid 28–9.

[50] Paul Butcher, ‘Disinformation and Democracy: The Home Front in the Information War’ (2019) Discussion Paper, European Politics and Institutions Programme, available at https://www.epc.eu/content/PDF/2019/190130_Disinformationdemocracy_PB.pdf accessed 7 September 2021.

[51] ERGA (n 40) 31–4.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Mike Ananny, ‘The Partnership Press: Lessons for Platform-Publisher Collaborations as Facebook and News Outlets Team to Fight Misinformation’ (Tow Center for Digital Journalism 2018), available at https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D85B1JG9 accessed 6 August 2021.

[54] Lauren Teeling and Niamh Kirk, ‘Codecheck: A Review of Platform Compliance with the EC Code of Practice on Disinformation’ (2020) 12–13, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340978676_Codecheck_A_Review_Of_Platform_Compliance_With_The_EC_Code_Of_Practice_On_Disinformation accessed 21 December 2022.

[55] ERGA (n 40) 38.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Mozilla, ‘Data Collection Log — EU Ad Transparency Report, available at https://adtransparency.mozilla.org/eu/log/ accessed 23 September 2021.

[58] French Ambassador for Digital Affairs, ‘Twitter Ads Transparency Center Assessment’, available at https://disinfo.quaidorsay.fr/en/twitter-ads-transparency-center-assessment accessed 23 September 2021.

[59] Rory Smith, ‘The UK Election Showed Just How Unreliable Facebook’s Security System For Elections Really Is’ (BuzzFeed, 14 January 2020), available at https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/rorysmith/the-uk-election-showed-just-how-unreliable-facebooks accessed 23 September 2021.

[60] Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online [2016], available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination/racism-and-xenophobia/eu-code-conduct-countering-illegal-hate-speech-online_en accessed 18 January 2023; Commission, ‘Recommendation (EU) 2018/334 on Measures to Effectively Tackle Illegal Content Online’ C/2018/1177, 1 March 2018.

[61] Kuczerawy (n 45).

[62] Institute for Information Law, ‘The Legal Framework on the Dissemination of Disinformation Through Internet Services and the Regulation of Political Advertising: Final Report’ (December 2019), 31, available at https://www.ivir.nl/publicaties/download/Report_Disinformation_Dec2019-1.pdf accessed 21 December 2022.

[63] COM/2021/262 (n 6).

[64] Lawrence Lessig, Code Version 2.0 (Basic Books 2006) 135.

[65] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data [2016] OJ L119/1; Council Directive (EU) 2018/1808 on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services in view of changing market realities [2018] OJ L303/69 (AVMSD).

[66] Iva Nenadić, ‘Unpacking the “European Approach” to Tackling Challenges of Disinformation and Political Manipulation’ (2019) 8(4) Internet Policy Review, available at https://policyreview.info/node/1436 accessed 1 September 2021.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Google, ‘EC EU Code of Practice on Disinformation Annual Report’ (October 2019) 18.

[69] Commission (n 46).

[70] Facebook, ‘Baseline Report on Implementation of the Code of Practice on Disinformation’ (January 2019) sect 4.6, available at https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2019-5/facebook_baseline_report_on_implementation_of_the_code_of_practice_on_disinformation_CF161D11-9A54-3E27-65D58168CAC40050_56991.pdf accessed 21 September 2021.

[71] AVMSD (n 65) art 33a(1).

[72] Jean-François Furnémont and Deirdre Kevin, ‘Regulation of Political Advertising: A Comparative Study With Reflections on the Situation in South-East Europe’ (September 2020) 19, 27, 37–8, available at https://rm.coe.int/study-on-political-advertising-eng-final/1680a0c6e0 accessed 7 September 2021.

[73] Commission, ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising’ COM/2021/731, 25 November 2021.

[74] Jenny Gesley, ‘Germany: Social Media Platforms to Be Held Accountable for Hosted Content Under “Facebook Act”’ (Library of Congress, 11 July 2017), available at https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2017-07-11/germany-social-media-platforms-to-be-held-accountable-for-hosted-content-under-facebook-act/ accessed 6 August 2021.

[75] Butcher (n 50), 11.

[76] Human Rights Watch, ‘Germany: Flawed Social Media Law’ (24 February 2018), available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/14/germany-flawed-social-media-law accessed 14 September 2021.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Law No 2018-1202 on the Fight Against the Manipulation of Information 2018 (1), available at https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000037847559/ accessed 7 September 2021. Translated from French to English using Google Translate, available at https://translate.google.com/.

[79] Ibid art L163-2(I).

[80] Ibid.

[81] Rachael Craufurd Smith, ‘Fake News, French Law and Democratic Legitimacy: Lessons for the United Kingdom?’ (2019) 11 Journal of Media Law 52, 61.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Karine Barzilai-Nahon, ‘Toward a Theory of Network Gatekeeping: A Framework for Exploring Information Control’ (2008) 59 Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 1493.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Emily B Laidlaw, ‘A Framework for Identifying Internet Information Gatekeepers’ (2010) 24 International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 263, 268.

[86] Matthias C Kettemann and Anna Sophia Tiedeke, ‘Back Up: Can Users Sue Platforms to Reinstate Deleted Content?’ (2020) 9(2) Internet Policy Review, 8–10, available at https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/back-can-users-sue-platforms-reinstate-deleted-content.

[87] Ibid 9.

[88] Case No C/15/319230 / KG ZA 21-432 (Court of North Holland, 6 October 2021) ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2021:8539.

[89] Ibid.

[90] Martin Fertmann and Matthias C Kettemann (eds), ‘Can Platforms Cancel Politicians? How States and Platforms Deal With Private Power Over Political Actors: An Exploratory Study of 15 Countries’ GDHRNET Working Paper Series 3/2021, 55–57, available at https://www.hans-bredow-institut.de/uploads/media/default/cms/media/o32omsc_GDHRNet-Working_Paper-3.pdf accessed 19 August 2021.

[91] Ibid 55.

[92] EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (n 14).

[93] SWD/2020/180 (n 41).

[94] Chase (n 30).

[95] Paul-Jasper Dittrich, ‘Tackling the Spread of Disinformation’ (2019) Policy Paper, Jacques Delors Institute Berlin, 7, available at http://aei.pitt.edu/102500/1/2019.dec.pdf accessed 1 September 2021.

[96] COM/2021/262 (n 6).

[97] See, e.g., Meta, ‘Facebook Community Standards: Inauthentic Behavior’, available at https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards/inauthentic_behavior accessed 6 August 2021; Twitter, ‘Platform Manipulation and Spam Policy’ (September 2020), available at https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/platform-manipulation accessed 6 August 2021.

[98] Britt van den Branden et al, ‘In Between Illegal and Harmful: A Look at the Community Guidelines and Terms of Use of Online Platforms in the Light of the DSA Proposal and the Fundamental Right to Freedom of Expression’ (DSA Observatory, 2 August 2021), available at https://dsa-observatory.eu/2021/08/02/in-between-illegal-and-harmful-a-look-at-the-community-guidelines-and-terms-of-use-of-online-platforms-in-the-light-of-the-dsa-proposal-and-the-fundamental-right-to-freedom-of-expression-part-1-of-3/ accessed 6 August 2021.

[99] JOIN/2018/36 (n 2).

[100] Paolo Cavaliere, ‘From Journalistic Ethics to Fact-Checking Practices: Defining the Standards of Content Governance in the Fight Against Disinformation’ (2020) 12 Journal of Media Law 133.

[101] Ananny (n 53).

[102] See, e.g., Facebook, ‘Annual Report on the Implementation of the Code of Practice for Disinformation’ (29 October 2019), available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/annual-self-assessment-reports-signatories-code-practice-disinformation-2019 accessed 6 August 2021; Commission (n 46).

[103] See, e.g., Meta, ‘Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior’, available at https://about.fb.com/news/tag/coordinated-inauthentic-behavior/ accessed 6 August 2021; Twitter Transparency Center, ‘Information Operations’, available at https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/information-operations.html accessed 6 August 2021.

[104] See, e.g., Commission (n 46) and Facebook (n 102).

[105] See, e.g., Commission (n 46) and Facebook (n 102).

[106] SWD/2020/180 (n 41) 10.

[107] Kettemann (n 86).

[108] Bundesgerichtshof, ‘Federal Court of Justice on Claims Against the Provider of a Social Network Who Deleted Posts and Blocked Accounts on Charges of “Hate Speech”, Press Release No. 149/2021’ (29 July 2021), available at https://www.bundesgerichtshof.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2021/2021149.html accessed 9 August 2021.

[109] Ibid.

[110] Ibid.

[111] Commission, ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on a Single Market for Digital Services (Digital Services Act)’ COM/2020/825, 15 December 2020 (DSA), ch III. All citations to the DSA are to the final version concluded at trilogue. There may be linguistic changes in the forthcoming final text.

[112] Ibid art 2(h).

[113] Ibid recitals 53–4; ch III, sects 3–4.

[114] Ibid recital 54.

[115] Ibid art 13(1)(e).

[116] Ibid arts 24, 30

[117] COM/2021/731 (n 73).

[118] DSA (n 111) arts 17–18.

[119] Ibid art 12(1).

[120] Naomi Appelman, João Pedro Quintais, and Ronan Fahy, ‘Article 12 DSA: Will Platforms Be Required to Apply EU Fundamental Rights in Content Moderation Decisions?’ (DSA Observatory, 31 May 2021), available at https://dsa-observatory.eu/2021/05/31/article-12-dsa-will-platforms-be-required-to-apply-eu-fundamental-rights-in-content-moderation-decisions/ accessed 9 August 2021.

[121] DSA (n 111) art 26(1)(b).

[122] Ananny (n 53).

[123] Meta, ‘Fact-checking Policies on Facebook’, available at https://www.facebook.com/business/help/315131736305613 accessed 9 August 2021.

[124] Emily Taylor et al (n 38).

[125] Facebook, ‘April 2021 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report’, available at https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/April-2021-CIB-Report.pdf accessed 9 August 2021.

[126] Ibid.

[127] Facebook, ‘April 2020 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report’, available at https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/April-2020-CIB-Report.pdf accessed 9 August 2021.

[128] Facebook, ‘January 2021 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report’, available at https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/January-2021-CIB-Report.pdf accessed 9 August 2021.

[129] Facebook, ‘August 2020 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report’, available at https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/August-2020-CIB-Report.pdf accessed 9 August 2021.

[130] Meta (n103); Twitter Transparency Center (n 103).

[131] DSA (n 111) art 13(1)(c).

[132] Ibid art 26(1)(c).

[133] Ibid art 26(2).

[134] Ibid art 33(2)(a), (3).

[135] Ibid art 27(2)(a)–(b).

[136] Ibid art 13(1)(d).

[137] Ibid art 23(1)(a).

[138] Lumen, ‘About Us’, available at https://lumendatabase.org/pages/about accessed 9 August 2021.

[139] Carolyn E Schmitt, ‘Shedding Light on Fraudulent Takedown Notices’ (Harvard Law Today, 12 December 2019), available at https://today.law.harvard.edu/shedding-light-on-fraudulent-takedown-notices/ accessed 28 September 2021.

[140] Ibid.

[141] Eugene Volokh, ‘Shenanigans (Internet Takedown Edition)’ (2021) 2021 Utah Law Review 237.

[142] Genevieve Lakier, ‘Informal Government Coercion and the Problem of “Jawboning”’ (Lawfare, 26 July 2021), available at https://www.lawfareblog.com/informal-government-coercion-and-problem-jawboning accessed 9 August 2021.

[143] DSA (n 111) art 12(2).

[144] Appelman et al (n 120).

[145] Ekin v France App no 39288/98 (ECtHR, 17 July 2001) para 58.

[146] Ibid para 60.

[147] Ibid para 61.

[148] Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey App no 3111/10 (ECtHR, 18 December 2012) para 64.

[149] Ibid para 64.

[150] COM/2021/262 (n 6).

[151] Oversight Board, ‘Annual Report 2021’ (June 2022), available at https://oversightboard.com/news/322324590080612-oversight-board-publishes-first-annual-report/ accessed 23 June 2022.

[152] Godlevskiy v Russia App no 14888/03 (ECtHR, 23 October 2008) para 45.

[153] Pedersen and Baadsgaard v Denmark App no 49017/99 (ECtHR, 17 December 2004) para 77; Thorgeir Thorgeirson v Iceland App no 13778/88 (ECtHR, 25 June 1992) para 65; Jersild v Denmark App no 15890/89 (ECtHR, 23 September 1994) para 35; Godlevskiy (n 152) para 45.

[154] Godlevskiy (n 152) para 45.

[155] Kacki v Poland App no 10947/11 (ECtHR, 4 July 2017) para 56.

[156] COM/2021/262 (n 6) 5.

[157] Ibid.

[158] Daphne Keller, ‘Toward a Clearer Conversation About Platform Liability’ (2018) Knight First Amendment Institute, “Emerging Threats” Essay Series, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3186867 accessed 9 August 2021.