1 Facts

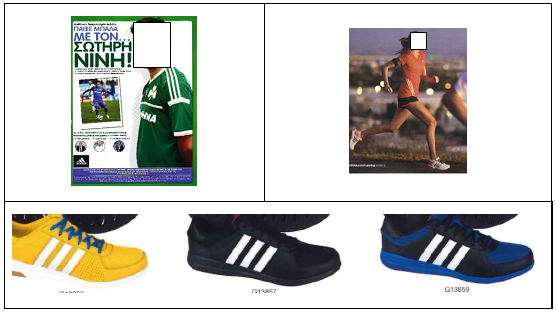

On 18 December 2013, adidas AG (hereinafter “adidas”), the well-known multi-national sportswear manufacturer based in Germany, filed an application before the Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (“OHIM”) (now “European Union Intellectual Property Office” – “EUIPO”) for the registration of the following Community trade mark (now “European Union trade mark”) for goods in Class 25 (“Clothing; Footwear; Headgear”) of the Nice Classification:

On 16 December 2014, the Belgian footwear company Shoe Branding Europe BVBA filed an application for declaration of invalidity of adidas’s figurative EU trade mark pursuant to Article 52(1)(a) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 (now Article 59(1)(a) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001) jointly with Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 (now Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001).

The Cancellation Division granted the application for declaration of invalidity on 30 June 2016, having found that adidas’s figurative EU trade mark “was devoid of any distinctive character, both inherent and acquired through use.”[2] Adidas then filed an appeal with the EUIPO on 18 August 2016. While accepting that the mark at issue lacked an inherently distinctive character, adidas asserted that the trade mark had acquired distinctive character through use pursuant to Article 7(3) and Article 52(2) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 (now Article 7(3) and Article 59(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001).

The EUIPO’s Second Board of Appeal dismissed the appeal on 7 March 2017 based on its findings that (i) the mark had been validly registered as a figurative mark; (ii) the mark was inherently devoid of distinctive character; and (iii) the evidence provided by adidas failed to prove that the mark had acquired distinctive character through use throughout the relevant geographical area, namely the EU.

2 Analysis

Adidas’s plea in law was based on the infringement of Article 52(2) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 jointly with Article 7(3) of the said regulation, as well as the principles of the protection of legitimate expectations and proportionality.

Specifically, adidas argued that the Board of Appeal (i) rejected most of the evidence provided having erroneously concluded that it referred to signs other than the mark at issue and (ii) made an error of assessment when it found that the mark at issue had not acquired distinctive character through use throughout the EU.

2.1 Adidas’s plea in law, part one: Alleged unjustified rejection of evidence

In the first part of its plea, adidas claimed that the Board of Appeal’s decision to dismiss numerous items of evidence on the ground that they referred to signs other than the mark at issue was based on (i) a misinterpretation of said mark and (ii) incorrect application of the “law of permissible variations.”[3]

2.1.1 Misinterpretation of the EU figurative trade mark

Citing “the EUIPO’s examination guidelines and the legitimate expectations which follow from them,” adidas argued that the mark at issue, although registered as a figurative mark, in fact constitutes a pattern mark, the dimensions and proportions of which may vary depending on the goods on which it appears.[4] The “three parallel equidistant stripes” that comprise the mark can therefore be elongated or shortened or presented obliquely without altering the distinctive character of the mark as registered.[5]

Responding to these arguments, the General Court noted first that “an EU trade mark may consist of any signs which may be represented graphically, provided that such signs are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.”[6] Citing Jaguar Land Rover v OHIM,[7] the Court also noted that only those specific characteristics of a trade mark (description, graphic representation etc.) that are indicated in the application for registration are entitled to protection.[8]

In particular, the Court stressed that it is the responsibility of the person who applies for a trade mark “to file a graphic representation of the mark corresponding precisely to the subject matter of the protection he wishes to secure.”[9] It follows that once a trade mark is registered, the owner cannot expect “a broader protection than that afforded by that graphic representation.”[10]

The Court noted that when an application for registration includes a description of the mark, “that description must be considered together with the graphic representation.”[11] Moreover, “the distinctive character of the mark” must be examined “in the light of the type of mark chosen by the applicant in its application for registration.”[12]

It was further observed that neither Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 nor Commission Regulation (EC) No. 2868/95, which applied when the application for a declaration of invalidity was filed, refers specifically to “pattern marks” or “figurative marks.”[13]

The Court acknowledged that “until the entry into force of Implementing Regulation 2017/1431, a pattern mark could be registered as a figurative mark, where it consisted of an image.”[14] However, the mark at issue had been registered by adidas “as a figurative mark and on the basis of the graphic representation and the description” included in the application for registration.[15]

The Board of Appeal’s interpretation of the trade mark at issue, described as “three vertical, parallel, thin black stripes against a white background, whose height is approximately five times the width,”[16] closely coincides with the graphic representation provided at the time of registration. Therefore, the Board of Appeal correctly identified all the characteristics and elements that graphically compose the trade mark at issue.

This interpretation was contested by the applicant, who argued on the one hand that to register a figurative mark, it is not necessary to indicate certain elements, such as scale and/or proportions, and on the other hand that the trade mark at issue was a pattern mark. In other words, “a design consisting of three parallel equidistant stripes” was “the sole function of the graphic representation.”[17]

The General Court did not accept these arguments. Firstly, the Board of Appeal, in defining the trade mark at issue, did not refer to how its dimensions could be represented on a good. Secondly, the judgment invoked by the applicant regarding the registration of a figurative trade mark and its proportions had been misinterpreted by the applicant. Thirdly, the applicant claimed that the mark at issue is a pattern mark whose proportions are variable.

The General Court went on to argue that it is not clear from either the graphic representation or the description that the trade mark at issue is made up of “regularly repetitive elements.”[18] In addition, the General Court noted that no real evidence had been submitted by the applicant to prove its contention that “the use of the three parallel equidistant stripes,”[19] regardless of their length, represents “the object of the protection.”[20]

Finally, the General Court concluded by stating that the definition of “pattern mark” contained in the EUIPO’s examination guidelines was no different from the one reported in the Birkenstock case law.[21]

On this basis, the General Court concluded that the Board of Appeal had correctly interpreted and described the mark at issue in the contested decision as an “ordinary figurative mark.”[22] The Court therefore dismissed this first claim.

2.1.2 Misapplication of the “law of permissible variations”

The second claim in the first part of the plea refers to the misapplication of the “law of permissible variations,”[23] which holds that such variations must not alter the distinctive character of the registered trade mark.

The concept of “use” under Article 7(3) and 52(2) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009

Use is considered “genuine” when it can be shown to have penetrated the market through the commercial exploitation of the goods and/or services covered by the mark. Thus, a clear, unequivocal understanding of whether the use of a trade mark is or is not “genuine” is vital, particularly in the context of revocation proceedings for non-use.[24]

Before proceeding to analyse this claim, the meaning of “use” pursuant to Article 7(3) and Article 52(2) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 must be clarified. While adidas asserted that the concept of “use” must be understood “in the same way as the concept of genuine use,”[25] the EUIPO argued that when seeking to verify that a trade mark has acquired distinctiveness, its owner may refer only to the use of that trade mark as it was registered. In contesting the applicant’s interpretation, the EUIPO asserted that the concept of “genuine use” in Article 15(1) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 is less restrictive than that of “use” in Articles 7(3) and 52(2).

The General Court noted that while point (a) of the second subparagraph of Article 15(1) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 allows the owner of a trade mark to make small changes to the registered form for the purposes of marketing and promotion of the goods and services covered by that mark, provided its distinctive character remains unaltered,[26] neither Article 7(3) nor Article 52(2) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 specifically mention the use of a trade mark in a form other than the one for which it has been registered.

Therefore, point (a) of the second subparagraph of Article 15(1) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 must be interpreted as meaning that the forms of a trade mark used for the purpose of commercial exploitation are “broadly equivalent” to those covered by the registration.[27]

The “law of permissible variations”

Adidas claimed that the Board of Appeal incorrectly interpreted the “law of permissible variations” in finding that when a trade mark is extremely simple, even a small variation will lead to a deviation from the distinctive characteristics established when the mark was registered; that reversing the colour scheme of the mark at issue alters its distinctive character, as does the use of sloping rather that vertical stripes; and that some of the evidence adidas presented showed two rather than three stripes.[28]

In support of its arguments, adidas submitted numerous pieces of evidence, most of which were found to refer to signs that clearly differed from the registered EU figurative trade mark. For example:

The Board of Appeal considered that in view of the extreme simplicity of the mark in question (“three black parallel lines in a rectangular configuration on a white background”),[30] even a minimal variation could significantly alter the characteristics of the registered mark.

Given that the mark at issue was registered in black and white, a different colour combination can be interpreted as a significant difference that alters the fundamental characteristics of the mark, in which case the forms of use cannot be considered as “broadly equivalent” to those of the registered mark.[31] Therefore, the General Court concluded that the Board of Appeal was right to dismiss all items of evidence that referred to signs with three white stripes on a black background.

On this basis, the General Court dismissed this second claim and, subsequently, the first part of the plea in its entirety.

2.2 Adidas’s plea in law, part two: Erroneous assessment regarding the acquisition of distinctive character through use

In the second part of its plea in law, adidas claimed that the finding by the Board of Appeal that adidas had not proven that the mark at issue had acquired distinctive character through use within the territory of the EU was based on a misappraisal of its evidence.

Adidas argued that it had submitted plentiful evidence to support its claim regarding both the “intensive use” of the mark at issue and its recognition by the relevant public.[32] However, the only relevant evidence in such cases is that which refers to the trade mark “in its registered form.”[33] Evidence of forms which are “broadly equivalent” to the registered mark also are acceptable, but forms in which “the colour scheme is reversed or which fail to respect the other essential characteristics of the mark at issue” are not.[34]

In light of the above, the General Court considered whether the Board of Appeal had (i) correctly examined the evidence presented by adidas to establish that the mark had been used in “the relevant geographical area” and had acquired a distinctive character through that use and (ii) was justified in finding that evidence in relation to that area had not been presented.[35]

2.2.1 Evaluation of the evidence

As highlighted in the decision of the Court of Justice in Windsurfing Chiemsee Produktions-und Vertriebs GmbH (WSC) v Boots-und Segelzubehör Walter Huber and Franz Attenberger,[36] factors such as the length, intensity, and geographical spread of the use, the extent of investment in promoting the mark, market share, statements from trade and professional associations and so on must be evaluated globally.

Adidas provided several types of evidence in support of its claims:

- Images. The General Court found that the Board of Appeal rightly rejected most of the images adidas had presented in evidence because they referred to signs that were not broadly similar to the registered form of the mark at issue. Other images were considered “irrelevant” because they showed the mark on goods that were not at issue in the case.[37] Lastly, some of the images adidas submitted did not show that the mark at issue was sufficiently used “for a significant proportion of the relevant public to identify,” on the basis of that mark, “a product as originating from a particular undertaking.”[38]

- Data concerning turnover and marketing and advertising costs. Adidas submitted an affidavit before the EUIPO showing its turnover and the marketing and advertising expenses it had incurred. The General Court confirmed the assessment of the Board of Appeal that, although the affidavit showed that adidas had “used some of its marks in an intensive and ongoing manner within the European Union and ha[d] made considerable investments in order to promote those marks,”[39] it did not establish a link between those figures and the mark at issue because the figures related to the “entire business” of the company.[40]

- Market surveys. The General Court considered market surveys that adidas conducted in five European countries from 2009 to 2011. These five surveys showed that the mark at issue had been used in its registered form and indicated the degree of distinctiveness perceived by the relevant public. Although the General Court accepted these surveys “in principle” as “relevant evidence” that the mark at issue had “acquired distinctive character following the use which has been made of it,”[41] it criticized the survey methodology. As with the images discussed above, other market surveys adidas submitted in evidence referred to signs which differed from the registered form, particularly in terms of the colour and number of stripes.

- Other evidence. Adidas produced other items of evidence, including decisions by various national courts, although it did not expressly mention those decisions in the second part of its plea. However, these decisions were considered “irrelevant” because they did not relate to the registered form of the mark at issue.[42]

2.2.2 Evidence of use and distinctiveness

According to EU trade mark legislation, an EU mark is characterized, inter alia, by having a “unitary character”[43] and “equal effect”[44] in the territory of the EU. It follows that in order to be registered, an EU trade mark must have a distinctive character throughout the EU. That distinctive character can be inherent or acquired through use.

A mark that is not inherently distinctive can be registered if it has been shown to have acquired distinctive character through use in the territory of the EU. Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009 does not provide that the acquisition of distinctive character through use in each Member State must be demonstrated through separate evidence. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that, although it is not necessary to demonstrate that a trade mark has acquired distinctive character through use in each individual Member State, it must have acquired such distinctiveness throughout the EU.

Given that “the mark at issue is inherently devoid of distinctive character,”[45] the General Court concluded that the Board of Appeal was right to determine whether it had acquired distinctiveness for the relevant public within the EU.

The only relevant evidence on which to base this determination were the five market surveys previously noted, which did not cover the whole of the EU. Indeed, adidas was unable to demonstrate that the domestic markets of the five Member States in which surveys were conducted were comparable to the national markets of the other 23 Member States.

Because adidas failed to show that the mark at issue had been used throughout the EU, or that the mark, through that use, was identified with the goods for which it was registered, the General Court concluded that the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that adidas failed to prove that its mark had acquired distinctiveness throughout the EU through use.

For the various reasons set forth above, the General Court rejected the plea in its entirety and dismissed the action.

3 Conclusion

The substantive points of greatest interest in the present decision concern the distinction between pattern and figurative marks, the law of permissible variations, and the rule of evidence.

Regarding the nature of the trade mark at issue, the applicant claimed that, although it had been registered as figurative, the mark is a “surface pattern” which therefore can be reproduced in different dimensions and proportions depending on the goods on which it appears.[46] According to this interpretation, “the three parallel equidistant stripes constituting the mark at issue could be extended or cut in different ways, including cut at a slanted angle.”[47] The General Court disagreed with this reasoning. In fact, the Court cannot consider elements or characteristics of a trade mark that are not mentioned in the application for registration. In this case, the mark’s description did not indicate that the stripes could be represented in different ways or that they could be present in various colour schemes. In other words, no elements were given in the application to suggest that it was a “pattern mark.” Therefore, the General Court rightly confirmed that the mark at issue was a figurative mark and “that a figurative mark is, in principle, registered in the proportions shown in its graphic representation.”[48]

This issue, inter alia, highlights the need for precision when applying to register a trade mark. Specifically, it underscores the basis on which entitlement to the protection that registration is designed to secure rests, namely the graphic representation and description of the mark submitted with the application, and the type of mark chosen by the applicant. In other words, the decision in this case should serve as an important reminder to trade marks holders to monitor the use of their marks to ensure it is consistent with their description in their registration. Using a mark in a way that differs from the description submitted at the time of registration can prove enormously costly in terms of lost revenue and brand dilution. Therefore, particular attention must be paid at the registration stage to the graphic representation and description of the mark.

As for the law of permissible variations, Article 18(1)(a) of Regulation (EU) No. 2017/1001 allows the

use of the EU trade mark in a form differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of the mark in the form in which it was registered, regardless of whether or not the trade mark in the form as used is also registered in the name of the proprietor.

At first glance, the scope of this provision appears clear: variations to the trade mark which do not alter its distinctive character are permitted.[49] However, it is important to emphasize that the variations must be insignificant, so that the two signs (the one registered and the one used) are broadly equivalent. It is also worth noting that a trade mark with a strongly distinctive character will be less affected by an addition, omission, or alteration than a weakly distinctive mark. Therefore, variations are most likely to alter a mark whose distinctiveness is weak.

The mark in the present case represents a figurative mark “consist[ing] of three black parallel lines in a rectangular configuration on a white background.”[50] Involving no words or other specific elements, it is, therefore, a very simple mark. For this reason, the Board of Appeal and subsequently the General Court concluded that “even minor alterations to that mark may constitute significant changes, so that the amended form may not be regarded as broadly equivalent to the mark as registered.”[51] In the present case, the applicant submitted evidence of the figurative mark in which the registered colour scheme was reversed (i.e. three white parallel lines on a black background).

The General Court’s interpretation of the law of permissible variations seems less restrictive when we consider the nature of the mark at issue. In fact, it is because of its simplicity that this figurative mark is devoid of strong distinctiveness. Therefore, as set forth above, even a slight change can affect its distinctive character significantly. Indeed, unlike composite marks, whose distinctiveness is not generally influenced by variations to certain figurative elements, using a simple figurative mark (i.e. one involving only a design and no words) in a way other than the one registered may constitute an impermissible variation.

Finally, regarding the rule of evidence, this case underscores both the need to select evidence scrupulously and the error of assuming that an apparent abundance of evidence is sufficient proof of entitlement. In fact, the quality of the evidence presented – i.e. its direct relevance to the claims being made – is the primary basis for judgement. Despite their unique and distinctive circumstances, the adidas judgment recalls a recent decision by the EUIPO Cancellation Division concerning McDonald’s “BIG MAC” EU trade mark.[52] In both cases, lack of relevant evidence played a decisive role. Indeed, “the vast majority of the evidence”[53] provided by adidas was judged, first by the Board of Appeal and subsequently by the General Court, to be “irrelevant” because, inter alia, it did not relate to the use of the EU figurative trade mark in its registered form. Similarly, in the “BIG MAC” case, the evidence McDonald’s submitted was found to have little if any probative value, having been shown to be either unreliable (the Wikipedia entry), not independent (the affidavits and company website printouts) or largely irrelevant, containing none of the details the EUIPO requires to prove genuine use, suggesting that quality is more important than quantity when asserting a claim of genuine use.[54]

Adidas has registered other EU figurative trade marks in Class 25 of the Nice Classification, which will be unaffected by this decision and therefore may provide some protection for the company.[55] This favourable situation was also present in the “BIG MAC” case, where McDonald’s, although for different reasons, registered a “Big Mac” EU word trade mark exactly one year after the revocation request was filed.[56]

[1] Case T-307/17 adidas v EUIPO – Shoe Branding Europe [2019] ECR II-427 (hereinafter adidas), para. 2.

[2] adidas, para. 7.

[3] adidas, para. 23.

[4] adidas, para. 24.

[5] Ibid.

[6] adidas, para. 26.

[7] Jaguar Land Rover v OHIM, T-629/14, EU:T:2015:878, para. 34.

[8] adidas, para. 27.

[9] adidas, para. 30, citing Red Bull v EUIPO – Optimum Mark, T-101/15 and T-102/15, EU:T:2017:852, para 71. This case, appealed before the Court of Justice (C-124/18 P), was decided on 29 July 2019.

[10] Ibid.

[11] adidas, para. 31, citing Red Bull v EUIPO – Optimum Mark, T-101/15 and T-102/15, EU:T:2017:852, para 79. This case, appealed before the Court of Justice (C-124/18 P), was decided on 29 July 2019.

[12] adidas, para. 32, citing Enercon v OHIM, C-170/15 P, EU:C:2016:53, paras. 29, 30, and 32.

[13] adidas, para. 33.

[14] adidas, para. 34, citing Fraas v OHIM, T-326/10, EU:T:2012:436, para. 56.

[15] adidas, para. 35.

[16] adidas, para. 36.

[17] adidas, para. 38.

[18] adidas, para. 43.

[19] adidas, para. 44.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Birkenstock Sales v EUIPO, T-579/14, EU:T:2016:650.

[22] adidas, para. 46.

[23] adidas, para. 48.

[24] Indeed, if a trade mark is not used continuously for a period of five years and there are no valid reasons for its non-use, it can be revoked. See Matteo Mancinella, “Evidencing Genuine Use: The EUIPO’s Decision to Revoke McDonald’s ‘BIG MAC’ European Union Trade Mark” (2019) 41(6) European Intellectual Property Review 391–394.

[25] adidas, para. 50.

[26] adidas, para. 54, citing, inter alia, Rintisch, C-553/11, EU:C:2012:671, para. 21.

[27] adidas, para. 61, citing, inter alia, LTJ Diffusion v OHIM – Arthur and Aston (ARTHUR & ASTON), T-83/14, EU:T:2015:974, para. 18.

[28] adidas, para. 64.

[29] adidas, para. 68.

[30] adidas, para. 70.

[31] adidas, para. 101.

[32] adidas, para. 106.

[33] adidas, para. 107.

[34] Ibid.

[35] adidas, para. 108.

[36] adidas, para. 109, citing Joined Cases C-108/97 and C-109/97, Windsurfing Chiemsee Produktions- und Vertriebs GmbH (WSC) v Boots- und Segelzubehör Walter Huber and Franz Attenberger, Judgment of the Court, 4 May 1999, EU:C:1999:230, para. 51.

[37] adidas, para. 118.

[38] adidas, para. 119.

[39] adidas, para, 121.

[40] adidas, para, 123.

[41] adidas, para, 130.

[42] adidas, para, 141.

[43] Article 1(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 (previously art. 1(2) of Regulation (EC) No. 207/2009).

[44] Ibid.

[45] adidas, para. 150.

[46] adidas, para. 24.

[47] Ibid.

[48] adidas, para. 41.

[49] In this regard it should also be noted that the EUIPO’s Management Board and Budget Committee recently adopted the CP8 Common Practice “Use of a trade mark in a form differing from the one registered.” This document is a useful reference for assessing “when the use of a trade mark in a form differing from the one registered alters its distinctive character.”

[50] adidas, para. 70.

[51] adidas, para. 72.

[52] EUIPO Cancellation Division, Decision of 11 January 2019, Cancellation No. 14788 C (Revocation), Supermac’s (Holdings) Ltd v McDonald’s International Property Company Ltd.

[53] adidas, para. 67.

[54] Mancinella, supra n. 24.

[55] See, for example, trade mark no. 003517612 (Figurative), filed 3 November 2003, registered 26 April 2007, Class 25 (“Clothing”), described as consisting of “three parallel equally spaced stripes applied to a garment, the stripes running along one third or more of the side of the garment;” trade mark no. 003517661 (Figurative), filed 3 November 2003, registered 26 April 2007, Class 25 (“Clothing”), described as consisting of “three parallel equally spaced stripes applied to a trouser or short, the stripes running along one third or more of the length of the side of the trouser or short;” trade mark no. 004269072 (Figurative), filed 2 February 2005, registered 9 January 2008, Class 25 (“Headgear”), described as comprising “three stripes applied on a cap visor, as shown in the illustration, the shape of the cap as such does not form part of the mark.”

[56] See trade mark no. 017305079 (Word), filed 6 October 2017, registered 11 April 2018, Classes 29, 30, 43.