1 Introduction

Before digitalisation, the vertical structure of the market for recorded music could roughly be described as a large number of creators (composers, lyricists, and musicians) supplying creative expressions to a small and decreasing number of larger record labels and publishers. These funded, produced, and marketed the resulting recorded music and subsequently sold this to consumers through a fragmented retail sector.[1] To use the description of Richard Caves, the record labels and publishers acted as the centre of gravity of a nexus of contracts, controlling the production of consumed music.[2] Being at the centre of contracting, record labels and publishers project-managed production, bore most of the risks, and in return, gained rewards as residual claimants of the stream of revenues generated. In other creative industries, most notably book publishing, digitalisation has led to (a) increased concentration at the retail level, (b) a possible reduction in concentration through disintermediation in other intermediate levels, and (c) a potential shift in the centre of gravity of contracts towards creators trading directly through the on-line retailers.[3] In this paper, we demonstrate that for the first two, similar observations can be made in the music industry. However, in contrast with the book industry, music labels and producers appear to have maintained their share of the market.

Increased concentration at the retail level implies the existence of successive oligopolistic segments within the industry. Such structure is associated with a concern that consumer prices may be subject to double-marginalisation, i.e. a situation where the two successive levels add an oligopolistic mark-up to their costs, including wholesale costs. This is likely to be detrimental to consumers without necessarily benefiting creators.

Disintermediation, on the other hand, may have the effect that the current structure is short-lived because it poses two possible challenges to the power of the record labels and publishers. One direct challenge arises from the entry of new players offering increased competition. The other comes from the creators directly because of the increased availability of the tools necessary for “self-publishing”. This enables creators either to take control directly, by becoming the new centre of gravity of contracts, or to threaten to do so to strengthen their bargaining position during negotiations. In this regard, it is beneficial that major retailers, such as Amazon, are used to dealing with small independent retailers and sometimes even individual sellers. A better understanding of the developments in the structure of this industry will help us predict future effects on both creators and consumers. As copyright is another major driver shaping creative industries, a key element of this paper is to provide an appreciation of the effects of and recent developments in this area.

Throughout the paper we have tried to identify relevant data. Finding (consistent) data on variables, such as market shares, is surprisingly hard. What we do find is that, while there are some features in common with what can be observed in the market for books, there are also important differences. As with books, the retail sector has become dominated by a small number of firms. Those creating music have available internet services which enable them to produce and even retail their own music without going through the traditional channels of record labels, publishers and collecting societies. In contrast to the book industry, the market shares, in particular of digital music, of the top three largest record labels have remained more or less constant, possibly due to the complexities of the exploration of copyright within the music industry.

The paper is structured as follows: section 2 provides a contextual background by describing the evolution in consumers’ habits. Section 3 focuses on the legal framework surrounding creation and commercialisation of music. Section 4 discusses the evolution in the market structure in the music industry. Finally, section 5 offers some brief conclusions.

2 The effect of digitalisation on recorded music

It is commonly accepted that the digital age has changed everything in terms of music experience. With digital music, we saw the decline of physical mediums on which music was recorded and an increase in types of devices on which music could be played.

While the CD was the first medium on which one could store digital music, the big leap was the creation of the MP3 file format, which compressed the file size of a recording without noticeable loss in quality. The real effect of this was not fully realised until the introduction of portable devices such as MP3 players and iPods, enabling consumption of music wherever the listener was located.[4]

Early versions of MP3 players had rather limited capacity and were only able to hold a small number of songs. The iPod first generation, launched in 2001, was a huge improvement on other MP3 players. iTunes does not use MP3 encoding but songs are encoded in Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) format, superior to MP3.[5] Where the first MP3 players could hold roughly 12 tracks, the first generation of iPods could store up to 5 GB worth of MP3 files (i.e. roughly 1,000 tracks). These portable devices have subsequently been constantly improved and today, in addition to much larger storage capacity, include numerous improvements including, for example, powerful processors and a high-quality screen capable of displaying video. Whilst MP3 continued to evolve, new ways of listening to music emerged. Today, consumers listen to music on other portable devices such as smartphones, tablets, and even watches.

2.1 Platforms and peer-to-peer file sharing

The creation of compressed digital files made delivering music over the internet a commercially viable possibility. The launch of the Apple iTunes Music Store in 2003 was the start of a new business model in which digital delivery, through the purchase and download of albums and individual tracks, was the product on offer. This helped catapult iTunes to the forefront of the music distribution business, making it the largest music distributor in the world since 2010. Other web-based retailers followed, making use of the increased number of devices capable of playing music.

The number of downloads initially grew rapidly, outstripping sales of CDs and other physical means of consuming music, but have since been overtaken by streaming. Music streaming services are broadly speaking services which enable the consumer to listen to the music without downloading it. Hence, no copy is made on the user’s personal device. Launched in 2005, Pandora appears to be the pioneer in music streaming services. This initiative tried to revive the Music Genome Project,[6] a sophisticated taxonomy of musical information generated by music experts which was then fed into an algorithm enabling users to listen to music matching their tastes. Owing to the wealth of the information on the database, Pandora’s search engine enables users to customise their listening experience and discover thousands of songs from across the world. While Pandora might have become a very popular service for listeners, it was less popular with creators. It is easy to appreciate the concerns of creators about a service which enabled users across the world to access tens of thousands of works without purchasing tracks or albums. To this day, the battle over royalties paid to creators and collecting rights societies continues, at least partly due to the large differences in the gross pay-out per stream to labels.[7] Irrespective of whether pay-per-play undercompensates the creators, in terms of economic logic, the move from a share of album sales to a pay-per-play remuneration also implies a shift of risk from consumer to creator. When buying the album, the consumer took the risk that they might not enjoy the album as much as expected, whereas with pay-per-play the creators take the risk that the consumer may lose interest in their music. This makes comparing the two scenarios challenging. Not only does one have to allow for potentially greater revenue from both those who listen a lot and those who listen a little, one must also allow for the impact of the risk premium on sales. Since 2007, Pandora experiences several royalty developments leading to licensing deals directly with music publishers such as ASCAP and BMI.[8]

Creating a new standard for online music distribution, Pandora was followed closely by Spotify, which was officially founded in Sweden in 2006. Despite the similar features between Pandora and Spotify,[9] these two streaming services differ in various ways. Spotify was classified as an interactive service and Pandora as a non-interactive service (closer to radio), which has consequences on the applicable licensing scheme.[10] For example, Spotify’s music catalogue is about 20 times larger than Pandora’s, making Spotify the “gold standard” among streaming services.[11] However, probably due to the sophisticated Music Genome Project, Pandora remains the reference point for music discovery.

The arrival of streaming services went one step further in connecting users. Both Pandora and Spotify provide their users with the ability to connect with friends, share music they like, and recommend either tracks or entire playlists to other users. Nevertheless, streaming services do not provide identical social features. In this category, Spotify is superior to Pandora as it provides a real possibility for users to interact with their friends by allowing them to share music via social media websites such as Facebook, Twitter, or Tumblr, but also via Spotify’s own messaging application. Finally, Spotify offers the possibility for users to collaborate and create playlists together. Today, other streaming services have emerged, such as iHeartRadio, iTunes music, Google Play, Rhapsody and other new names keep entering the market, e.g. Tidal, Deezer, Amazon Prime Music, Amazon Music Unlimited, and SoundCloud. Data from June 2017 suggests that Spotify remains the most popular subscription service,[12] with 40% of the market, followed by Apple Music (19%) and Amazon (12%).[13]

Alongside these applications, video-sharing websites started to stream music. Founded in 2005 by PayPal employees, YouTube quickly became the world’s most important online video portal. Ever since its purchase by Google in 2006, YouTube also became the world’s second largest search engine, catapulting the online sharing platform to the forefront of online distribution channels. Furthermore, in 2015 YouTube developed its own music app, YouTube Music, aimed at enabling users to search only for music-related results. By the end of 2017, YouTube had signed agreements with the three major record labels to share revenue, in addition to agreements previously reached with collecting Rights Societies, such as PRS for Music in 2016.[14] YouTube is planning to introduce a subscriptions service in 2018 by combining Google Play Music and YouTube Red.[15] In an attempt to please right-holders, YouTube has announced its intention to “force” long-established listeners to subscribe to its paid music service by impeding their experience and pestering them with more ads than the casual YouTube user.

From different directions, the services all appear to travel towards subscription-based streaming.[16] Whether this will be the new equilibrium in the long-run remains to be seen. It is notable that previous digital products, such as CDs and downloads, have grown rapidly only to peak and then to decline (vinyl appears to be the odd one out as a medium which is growing again as it becomes collectable).[17] The growth rate of streaming, particularly for subscription-based streaming, is more dramatic and arguably driven by the nature of current competition. In the IFPI 2017 report, Spotify’s Economics director, Will Page, noted:

What is especially key is that it is competition based around market growing, not market stealing. There are more big players – and arguably more sustainable players – than have come and gone in the past, and it’s all about making new audiences aware of streaming and expanding the market.[18]

Streaming services differ across a number of characteristics, raising several questions. Does the consumer view radio, non-interactive streaming (e.g. Pandora), and interactive (e.g. Spotify) streaming as close substitutes? From the consumer perspective, a key difference between non-interactive and interactive streaming is that for the former, users do not control the songs played next (mimicking a radio broadcast) and for the latter users choose the tracks which are played.[19] Where should one place video-sharing websites such as YouTube, which feature licensed music as well as other content, included user-generated videos? Other differences relate to “payment”: freemium and advertising, or subscription-based business models. The services historically relied on advertising to generate revenue (e.g. YouTube or ad-funded Spotify), but have slowly but increasingly introduced subscription models.[20] Individual services are further differentiated in terms of shared playlists and algorithmic suggestions. In this regard, YouTube has been growing exponentially, leading to a battle between the music industry and YouTube to ensure fair remuneration.[21]

The developments in the mode and cost of the delivery of music, made possible by digitalisation, have created a small set of new downstream retailers and potentially removes some of the scale arguments for the concentration among labels, publishers, and collecting societies. On their own, these changes would be expected to lead to significant changes in industry structure. However, the power of these developments to change structure depends, at least to some extent, on the rules provided by the copyright framework. In the next section we summarise this framework to illustrate that it still favours the traditional intermediaries who are able to spread the transaction cost of managing the framework across the output of creators and artists.

3 Legal aspects

Intellectual property rights, and especially copyright, underpin the economic framework used in the music industry. By conferring a bundle of rights to right-holders, creators can license their works in the UK and around the world, and generate revenue to incentivise investment in creating new creative content. Digitalisation and the growth of the internet have fundamentally transformed the way we access and listen to music, but they also and continue to require the music sector constantly to reinvent itself to extract revenues from the emerging services and platforms while shielding copyright-protected works from copyright infringement. Given the central role of copyright in the music industry, this section will give an overview of some of the key copyright principles applicable in the UK.

3.1 Copyright and the multi-layering of rights

In the UK, the copyright regime is governed by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988,[22] as well as EU directives[23] and international treaties.[24] If a person creates a song (the composition), copyright can subsist in the lyrics (literary work) and the music (musical work) provided these works are original,[25] in addition to existing in any material form.[26] The first copyright owners of this composition are generally its creators.[27] But a song which has been recorded can also attract a separate copyright protection, referred to as an “entrepreneurial work” in UK legislation.[28] In contrast with copyright vested in authorial works, the first copyright holder of an entrepreneurial work is the record producer.[29]

These rights are not transferred to the owner of the physical product (e.g. CD, MP3, or other digital file), who therefore does not own the copyright(s) embodied within it. Users who purchase a CD lawfully are not entitled to copy or communicate its content if they do not own the copyright(s) in the song. However, current technology allows user to easily copy or communicate works (whether it is to burn a CD or copy a digital file). This generally constitutes a violation of the right-holders’ copyright. Indeed, once copyright subsists in a work, its right-holder is granted a bundle of exclusive[30] rights. First, the right-holder is provided with a set of economic rights[31] to cover activities such as copying the work, communicating the work to the public, making adaptations, issuing copies of the work to the public, performing the work in public, broadcasting or sending a cable transmission of the work (which includes digital transmission), and lending the work to the public. These rights are designed to enable the right-holder to extract rent, which is then dispersed according to contractual arrangements with those involved in producing the object of the copyright. The costs and effectiveness of this rent extraction may depend on to whom the rights are finally assigned to. Secondly, moral rights are granted to authors.[32] Essentially, in the UK these include the paternity right[33] (and the right not to have a work falsely attributed to anybody else but its author)[34] and the integrity right.[35] Unlike economic rights, the paternity right must be asserted[36] and moral rights cannot be assigned. However, these can be waived[37] and are transferrable upon death.

Finally, there are performers’ rights. While these rights were initially reserved for public performances only,[38] the EC Rental Directive[39] extended the protection to anyone involved in a recording – including both featured and session musicians – when licensed for broadcast purposes. This extension of rights complicates the production of recorded music, because activities that had previously simply been an input into the process, remunerated only once, are now potentially entitled to an ongoing stream of income. A consequence of this is that a larger group of musicians depend on the success of the recording, and hence a group that had not previously borne any risk now does. In effect, after the change, more of those involved in producing music faced a remuneration based partly on the success of the performance. Since this group is getting a deferred, if uncertain, income, standard economic logic based on the principal-agent theory[40] would imply that their initial fee or salary would be reduced. By how much depends on the size of the risk and their attitude to risk. The greater the risk and the more they dislike risk, the greater a risk-premium has to be included in the initial fee or salary. The standard reason for the principal to link remuneration to outcome is to provide incentives for the agent to put in the appropriate effort. The standard problem is that increasing incentives usually imply increased risk and the principal is typically assumed to be more able to shoulder this risk. If the principal is a large record label or producer and the agent a session musician, it would seem reasonable to assume that the former is better able to tolerate risk arising from unsure future incomes. Hence, absent any incentive problems, the risk faced by the music performers should be minimised. Placing more risk on musicians may incentivise them to play “better”, but arguably there are less costly means of achieving this since the effort is readily observable to the principal, who can take appropriate action. Moreover, reputational effects may be very powerful in ensuring a high-quality performance. From this perspective, it is difficult to identify the benefits for the performers from the EC Rental Directive. The EC Rental Directive clearly increases the cost of managing a recording. Having to identify and keep track of a larger set of people entitled to a share of the rent generated adds considerable transaction costs to the disbursement of monies collected from recorded music. For standard transaction cost reasons the Directive strengthens the motivation for having large established traditional intermediaries who can spread the costs of the disbursements across a large number of recordings.

The legal beneficiary of performers’ rights is the performer of a particular musical performance. The rights can appear similar to the ones granted to right-holders of authorial works, but they remain somewhat different. As such, performers also have a reproduction right, distribution right, rental and lending right, and a right to make the work available to the public, but they also have the right to equitable remuneration.[41] Finally, performers also enjoy moral rights as described above.[42]

This brief description of the key copyright concepts is potentially misleading, because it focuses on UK copyright only. The previous section demonstrated that the evolution of music consumption strives towards more internationalisation. Therefore, it is important to take into consideration domestic idiosyncrasies when analysing the UK music market, but we also need to consider its international dimension and other countries’ variations which are especially relevant when dealing with assignment and licensing of copyright.[43]

The key insight form this subsection is that, even without adding the international dimension, copyright is complex, and compliance costly. This derives from the multi-layering of rights embodied in a single track and its inherent numerous right-holders. This in itself creates increasing returns to scale in the delivery of music from creator to consumer. However, original creators rarely remain the right-holders of their works. To maximise their chances of reward, generally right-holders transfer their copyrights to collecting rights societies, which license music on the creators’ behalf and collect royalties deriving therefrom.

3.2 Assignment and licensing of copyright

To ensure remuneration and dissemination, most right-holders of authorial and entrepreneurial works assign (by selling) or license (by authorising) their copyrights to third parties. Adding a further layer of complexity, a right-holder can decide to share these exclusive rights between several third parties.[44] However in practice, these are often licensed collectively to specific bodies, arguably because of the complexity of the copyright system which creates large transaction costs.[45] These collecting rights societies became increasingly important not only to help creators enforce their rights and collect royalties by granting licences but also in an ideal world to ensure correct distribution of these royalties.

In the UK, right-holders of the composition, usually assign their performance and broadcasting rights to Performing Right Society (PRS) for Music which administers the licences of the works’ performances.[46] In order to develop a record, the first copyright owner (generally the publisher) can assign the right to record the work, known as the mechanical right. The right-holders of the musical works traditionally mandate the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society (MCPS) to administer these rights to reproduction. Hence, whoever wants to record music must seek prior authorisation from MCPS. The royalties are then redistributed to the copyright owners. As mentioned earlier, the rights in the sound recording are initially granted to the producer. In the UK, record companies employing these producers usually assign the exclusive rights to Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) to, for example, broadcast (including via internet transmission) the works or to authorise somebody else to make another recording including the original record (also known as synchronisation rights). As noted by Greenfield and Osborn, exclusivity is key in the music industry.[47] These authors explain how music industry players try to acquire exclusive control over creators and their outputs for at least as long as they are successful. In standard contracts, musicians exclusively license all exploitation of rights throughout the world during copyright protection to a label to ensure that all present and future performances can be identified and monetised. Efficient contracting among all those who are involved in producing music, which ensures that the rent extracted from the consumers of music is distributed in a fair manner and which keeps control over pricing among a few key players benefit those in the industry at the cost of consumers. Consequently, contract law also plays a crucial role and contractual terms need to be carefully negotiated. These can take different forms: license, exclusive long-term recording contract, development deals, production deals, and the most recent 360° model.[48]

In the changing technological and digital landscape, revenue is still generated. However, the ways in which the music industry generates revenues have adjusted. Firstly, there is an increase of “standard terms”, meaning that one party (e.g. the publisher or record company) imposes terms on the other party (e.g. the creator) who must either accept or refuse them.[49] This allows intermediaries to protect their interests in the music industry value chain.[50] Secondly, some costs have been reduced with digitalisation. As discussed below, with the emergence of streaming, music distribution does not require copying music on a tangible format.[51] The risk for a record company of being left with unsold stock is reduced as they can manufacture fewer physical records (e.g. CDs) without adverse effects on unit costs. The internet opens new possibilities for creators to produce and distribute their music independently of intermediaries (or traditional intermediaries) such as record labels or publishers. Because retaining the production and distribution roles can be very costly in terms of time and effort, creators may still prefer to sign a contract with traditional music publishers, but the option is there for those who are more entrepreneurial. New intermediaries have also increased the ability for creators to self-produce their music and self-publish their work via online intermediaries which enable direct interaction with consumers. Examples are Patreon, which organises a form of fan-funding by helping creators run a membership business and Bandcamp, which acts as a direct sales site. The digital environment empowers independent creators and labels to enter the market independently as an alternative to handing exclusive rights over to the established intermediaries such as labels, record companies, and collecting societies. In theory, record labels have lost their monopoly on the gatekeeper role as they are not solely responsible for deciding the music that consumers can listen to. With the distribution of musical content now available to everyone, consumers can decide which works they want to listen to. The key effect of the recent changes is that the value added by record labels and publishers is much reduced, which ought to translate into both less use and less profitable terms for the intermediaries. Who benefits the most from this – creators, retailers, or consumers – is less obvious.

Digitalisation has made the market for music more global. In an attempt to increase transparency and good governance, and to improve competition between collecting rights societies in the EU, the 2014 European Directive on the collective management of copyright also aims at facilitating trans-border licensing of online music.[52] By facilitating online licensing of authorial works, it is believed that the consumer’s position will be significantly improved by the availability of a large and more diverse repertoire of music throughout the European Union. Imposing new standards of transparency for right-holders, the directive modernises the organisation and management of collecting rights societies to ensure that right-holders have a say in how their rights are being managed, in order to maximise their chances at financial returns.

Overall, we note that the traditional copyright paradigm relies on intermediaries (i.e. publishers and labels), capable of exploiting two sources of economies of scale (the technology related to production and delivery of music, and the transactions costs arising from copyright law) to control and distribute the physical content comprising the creative content. In the digital era, the role of these traditional intermediaries is being questioned as the technological argument for such scale is reduced. The question raised about copyright is currently less about its effect through complexity on market structure and more about its adequacy in ensuring that creators derive adequate royalties from P2P or streaming services.

In recent years, the main debate focused on securing revenue streams from the increasingly powerful platforms disseminating music online. As we have seen, Spotify and other subscription-based services secure licences with right-holders. Currently, it is believed that Spotify pays around 70% of its revenues to right-holders. This share is further divided between record labels (55-60%) and publishers (10-15%). It would be erroneous to believe that this amounts to the share received by artists. Typically, the right-holders are collecting rights societies, record labels, and publishers to whom the artist will have transferred the copyright. Artists will nevertheless perceive the royalties distributed by the right-holders.

3.3 Towards subscription-based models

Following the utilitarian justification of copyright, copyright legislation establishes a system to promote creation and dissemination of works against financial reward. Traditionally, this system has mostly benefited the intermediaries through the transfer (or license) of exclusive rights from composition creators to organisations administering these rights on their behalf, against a percentage share. Just like composition creators, creators of sound recordings are also granted exclusive rights, which they can in turn transfer or license to record labels which will administer these rights on their behalf.

This paradigm is altered in the 21st century. The rise of online music distribution disrupted the music ecosystem to the extent that commentators question the current copyright system and its adequateness to provide incentives, given the difficulty of rights administration and enforcement of copyright in the digital world.[53] Digitalisation and disintermediation have made it possible to side-line publishers, and may also have exacerbated the differences between different groups of creators. This is particularly apparent in the attitudes towards free downloads, streaming, and even piracy. Digitalisation also has the capacity to alter the size and nature of transaction costs. The same is true of copyright laws. Since organisational structures as well as industry structures are driven to a significant extent by the saving of transaction costs (e.g. the raison d’être for the collecting societies), the interplay between digitalisation and copyright may be important. In the light of that, questioning the suitability of current copyright laws and the way in which they are used may be warranted. Is it possible to simplify the law to reduce transaction costs while maintaining its core functions? Will the combination of future technology and copyright rules enable creators to look after themselves, or would interventions ensuring that creators and performers receive a fair remuneration be more effective?

4 The market structure

In this context of technological change and the increasing reliance on copyright legislation by industry players, the question remains as to how these changes affect the music industry at large, especially intermediaries. Do creators still rely as much as before on collecting rights societies, publishers, and record labels, given both that technology has decreased production costs and that creators are able to sell directly music to consumers online?

4.1 Revenue sharing in the UK music industry in the pre-online music distribution era

In the previous section, we established that the copyright paradigm is the centre-piece of the music industry. It establishes a system which aims at fostering creation and dissemination of new works by providing right-holders with exclusive rights to control and exploit them. In so doing, copyright constitutes a bargaining chip for record labels. By transferring their exclusive rights to intermediaries, creators are entitled to royalties, which aims to promote the creation of new works.

To understand the impact of digitalisation on the music industry and the market’s structure, it is helpful to understand how royalties, derived from the reproduction and distribution of the sound recording, were calculated in the pre-digital era.[54] In the UK, royalties are calculated by multiplying the CD wholesale price by the royalty rate (which is traditionally specified in the contract between the creator and the record label). However, these calculations are affected by two considerations: the packaging deduction, and the reserve. The packaging deduction essentially deals with the cost of delivering the music to the retailer and is based on the philosophy that the creator should only be entitled to royalties deriving from the sales of the record or CD. The reserve refers to an amount of the income, to which the creator is entitled, which is kept back until an agreed sales volume has been reached. The motivations for this are that recording and manufacturing a record or CD is costly and this cost is sunk, that CDs are sold on a 100% return basis, and that demand is uncertain. Hence, marketing a record or CD is risky. This risk naturally varies depending on the CD and the creator, and hence so does the reserve. Passman reports that the reserve usually fluctuates between 20-30% and between 5-15% for more established creators.[55]

The first and obvious point to make is that both the deduction and the reserve are a phenomenon purely related to physical sales – with digital delivery, both disappear. Secondly, allowing for some costs to be deducted before sharing has the effect of moving the remuneration for the creator from a pure revenue share to a partial profit share. Moreover, the reserve amounts to a degree of risk sharing between creator and record label. Taken together, these two deductions from the royalties have the effect of making the creator more of a residual claimant alongside the record label, with similar incentives, but without any of the decision-making powers which often accompany such partnerships. If the creator is already taking some of the risk and paying for some of the costs, it may appear a small step to resume full responsibility.

4.2 The music industry in the online music distribution era

The rise of online music distribution disrupted this ecosystem, and especially the role of record labels. In a world where consumers relied heavily on tangible media to access music, record labels constituted important capital-providing intermediaries.[56] This essential role is being questioned in the online environment given the significant reduction of the upfront costs for bringing music onto the market. In 2017, the IFPI Digital Music Report noted that in 2016, the new online music models account for more than half of industry revenues (having overtaken the share of physical works already in 2015).[57]

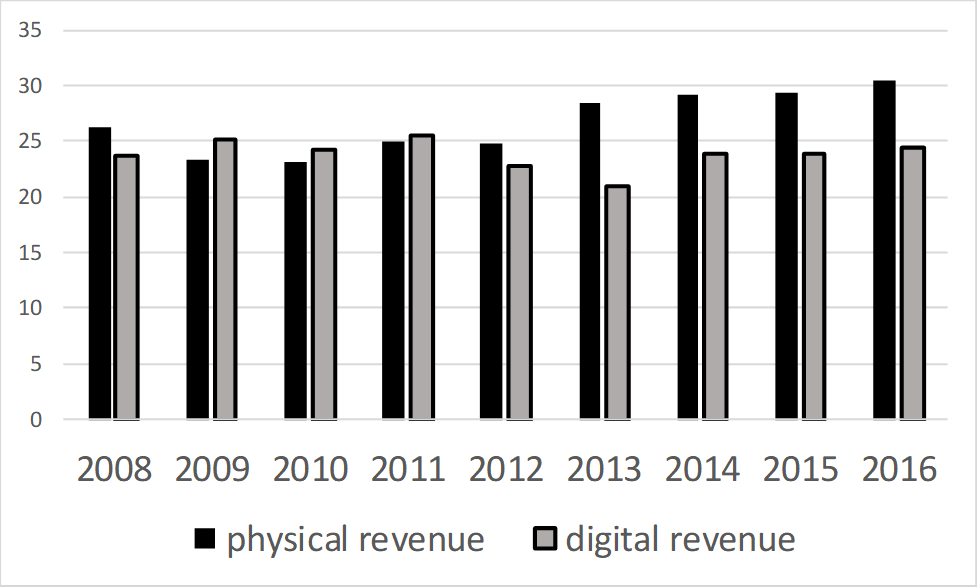

The market shares for physical and digital music over the period 2008-2016 is fairly stable, with a small set of major labels and a large set of independent labels. The main overall change has been the merger between EMI and Universal Media Group, which reduced the set of major labels to three. The market share of the independents over that period is summarised in figure 1 below:

An alternative to using a record label to distribute your music has emerged in recent years. There is currently a large number of such services, including Amuse, AWAL, CD Baby, DistroKid, Ditto Music, Fresh Tunes, Horus Music, Landr, MondoTunes, OneRPM, ReverbNation, RouteNote, Soundrop, Stem, Symphonic, and Tunecore. These digital distribution companies help those musicians who chose to record and produce their own music, so called “DIY musicians”, to get their music onto streaming platforms (digital service providers). In the future these services will also enable DIY musicians to collect royalties themselves.[60] While some of these services have been active for many years (CD Baby was founded in 1998), this is a developing area which in the longer term has the potential to enable DIY musicians to sidestep both record labels and collecting societies. For this they clearly benefit from having new entrants in the retail market, such as Amazon, who are used to retail on behalf of small firms and even individuals.

Both the labels and self-recording creators need to retail music whether it is in the form of a physical product or a digital file for downloading or streaming. While some brick and mortar stores remain, in particular the chain store HMV, the number of independent stores has decreased as they have become niche outlets. Overall brick and mortar retail accounts for about a third of the sales revenues in the UK. The main channels for retail distribution are either on-line retailers or streaming services. BPI statistics[61] show that, for the UK, streaming outstripped sales of digital singles (downloads) for the first time in 2014. This was both due to a steep growth in streaming and partly to the sales of digital singles levelling off. At the same time the sale of physical albums and singles continued its sharp decline. This, in itself, points to a shift away from brick and mortar stores. If one looks at sales by major retailers for 2015, Amazon (27.0%) and Apple (26.7%) between them have more than half the music retail market in the UK, while the specialist chain-store HMV had 15.4%, the major supermarkets 17.0%, and remaining outlets 13.9%. The Herfindahl measure of concentration at the retail level is around 0.18. This corresponds to having an industry with between 5 and 6 retailers of similar size. As the data take in retailers with very different profiles, this has clearly become a concentrated part of the market.

While central download-based models remain popular, their popularity seems rapidly to be declining, the music download market-share of 84.4% of the digital music market in 2010 has shrunk to 34.9% in 2016.[62] Following the Napster saga, major record labels launched their own online music store, e.g. Sony Music Entertainment and Universal Music Group teamed up to launch Pressplay, while EMI, AOL/Time Warner, and Bertelsmann Music Group teamed up to launch MusicNet. These services did not do particularly well, given the limitations attached to the user experience. While these services struggled to take off, the demand for mainstream digital audio download led to the launch of iTunes Store, which linked to the iPod technology led to the growth of the music download market as users could download music directly onto their portable devices. Very quickly, other services emerged. For example, creators developed their own online music stores by embedding digital distribution widgets onto their website to sell their music directly to consumers.[63] These direct-to-fans (D2F) platforms consist of a business model which removes the “middle-man” by allowing creators to deliver music directly to fans, in the hope of allowing the former to retain a higher percentage of their sales revenue.

From the perspective of platform services, a big difference relates to the type of licence needed. Typically, non-interactive platforms are slightly privileged because these benefit from compulsory licenses, while interactive (on-demand) services are subject to voluntary licenses, affecting their bargaining power vis-à-vis the record labels. Streaming services have a lot in common with radio stations, and yet the licensing of these platforms is much more burdensome than for radio stations. Taking the example of an interactive subscription streaming service, such a service needs to obtain a licence from collecting rights societies for the use of the copyright-protected composition and for the sound recording. Therefore, not only does an interactive online service need to get a mechanical licence for the reproduction of the sound recording, but also for the protected authorial works embodied in the sound recording. Given that there is no statutory rate, these licensing fees are subject to negotiations, generally between MCPS (representing the right-holders and creators of the musical compositions) and the British Phonographic Industry (BPI), representing the record labels. In addition, the online music distribution service needs to clear the rights of performance and of communication to the public. This means that the platform needs to obtain a licence from PRS for Music and PPL. This fragmentation can be time consuming and burdensome for online music distribution services, especially when taking into consideration the need to get cross-border licensing. If having a full repertoire is valuable, it also has the potential for hold-up, where the last to agree a licence extract a disproportionately good deal and all want to be last.[64] However, changes are underway. PRS for Music and MCPS now license online music services together.[65] Additionally, resulting from a partnership between PRS for Music, STIM, and GEMA, an integrated licensing hub (known as ICE) was launched in 2016 to facilitate multi-territory licensing of works within the EU territory, providing a real pan-European online music rights licensing hub.[66] Reported statistics focus on various subsets of services and there appears to be no settled market definition. Finding market share data in streaming is difficult, but most business analysts suggest that there is a small number of dominant firms. The markets are, however, very fluid.

The consequences for the creators are yet fully to be played out. The album does not represent the market anymore. While the pre-digital market could be measured by looking at the average income per album, the streaming market is measured by the value per user. To remedy the licensing and royalty issues, the best way to measure this market is perhaps to measure the average amount earned per album/track per streaming user. Additionally, consumers seem to be more accustomed to paying for the access to a service rather than access to individual creators’ works. This reinforces the need for more transparency in the non-disclosure agreements signed between record labels (or collecting rights societies) and streaming services. In so doing, record labels often refuse to disclose the exact terms to the creators who may struggle to unravel the price at which their creative endeavour is being sold.[67] Hence, it is essential for featuring and non-featuring creators to include a provision in their recording contract with the record labels which provides for the distribution of royalty shares deriving from any form of streaming. The difficulty with these agreements, between interactive services and record labels, is that these are largely confidential, thereby reducing the bargaining power of the creator.

To adapt to the digital era, record labels have consolidated some earlier roles and acquired others. For example, record labels are essential for the marketing and promotion of music. Indeed, given the mass dissemination of works over the internet, consumers face an overabundance of choices and there are indications that consumers increasingly want to be told what music they are likely to enjoy, without actually searching for it. To do so, record labels play a crucial role in ensuring that the music is present on various online music distribution services, that it is played on relevant radio programmes, and that it obtains appropriate press coverage. These roles will become increasingly important if the licensing of online music is simplified, resulting in the entry of new platforms in the market.

Services like Spotify tend to focus on maximising their growth and popularity at the expense of short-term profit. The value of a streaming platform to the artist is in a combination of the number of streams and the amount paid per stream.[68] The former depends on the size of the subscription base. The latter depends on how important the piece of music is to the platform. Consumers prefer a streaming service that offers the best combination of cost (fee or adverts) and coverage of music. Depending on how the platform obtains its revenue, it will prefer a large number of users (advertising) or subscribers (fees). In other words this is a multi-sided market, and as we know, the pricing on such markets is complex, but the side which is most important to the platform tends to get the better deal. The only way to increase the artists’ revenue seems to be either to increase the number of ads on freemium services, or to increase the monthly fee for a subscription service. The problem is that this will deter some deals with potential advertisers or drive away the consumer to another service whilst the second option is likely to decelerate the growth of the platform as a whole, which goes against their current business model.

In conclusion, re-intermediation[69] in the music industry has begun on two accounts. Firstly, traditional intermediaries such as collecting societies and record labels are adapting to the digital economy and new intermediaries are emerging, such as the various online streaming services, mimicking physical distribution of music. Secondly, digital aggregators have emerged as new intermediaries,[70] providing services to supply creative content in the appropriate digital formats to digital retailers. Crucially, both the record company level and the retail level are now best characterised as concentrated oligopolies. Although there is some evidence that some consumers multi-home, using streaming to identify new creators but then wanting to purchase physical copies of the creators they like,[71] the fragmentation is likely to reduce competition. The consumer response to reduced competition is harder to gauge, because multi-homing may be viewed as costly. The convenience of a one-stop-shop may therefore outweigh any increase in the price for the service.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we demonstrated how the value chain structure of the music record industry has evolved (and is still evolving). The changes have been manifold. Firstly, at retail level digital downloads have contributed significantly to the delivery of music to consumers but this is being overtaken by the growth of streaming.[72] While it is recognised that some consumers might prefer obtaining a physical copy, this may be less about consuming music and more about owning a collectible. Therefore, whether one considers digital and physical music as complementing or substituting one another depends on consumer preferences and on how supply (i.e. the amount of music available) is presented to the consumer. With an ever-expanding repertoire, consumers require new ways of navigating through this “long tail” of options. This explains the growing consumer interest in services which identify the content they are likely to want to access without the need for them to look for it. Secondly, at production level, Richard Caves’ centre of gravity of the nexus of contracts[73] appears theoretically to have moved from record labels and publishers to intermediaries such as streaming platforms. In Caves’ model, record labels and publishers were at the centre of contracts because they bore the greatest risk and gained rewards as residual claimants of the stream of revenues generated. Our research demonstrates the rise of disintermediated vertical services which displaced the centre of contracts towards internet service providers (ISPs). Today, these intermediaries are essential for the distribution of digital music to consumers. Even further, with the rise of apps, there is a theoretical possibility of bypassing (some) intermediaries, allowing content creators to sell music directly to consumers. This, consequently, places the content creator at the centre of the contractual relationship. Content creators (with the right project management skills) can plausibly bypass traditional intermediaries to deal directly with music retailers and consumers. The threat of “going it alone” is likely to lead creators to obtain better terms with publishers and record labels if they choose to deal with these established intermediaries. How effective this threat to bypass traditional intermediaries is likely to be depends on a number of issues beyond the scope of this paper, including any possible reforms to copyright laws, the creation of an open source database of music, and the future structure and behaviour of the CMOs. The current copyright rules, which have entrenched complexities into the way which the revenue generated from the rights are distributed, support the status quo of powerful industry actors. A reset through which copyrights are taken back to the basic premises of protecting moral rights and offering adequate incentives for talented individuals to engage in creative endeavours is likely to affect participants in the music industry, such as the established intermediaries, established and new artists and consumes, differently. Any adverse effects from a reduction in market power are likely to be experienced by the established intermediaries and the established artists, leaving the users and potentially new artists as the main beneficiaries. Given the lobbying strength of these different interest groups, such a reset does not seem likely.

Without further reforms, one might reasonably expect established creators to be better off financially with the new digital structures, thus having a greater incentive to create. The change in structure is considerably less likely to lead to a better deal for consumers. A greater level of concentration at several successive vertical levels, combined with increased bargaining power of established creators, is theoretically likely to increase the upwards distortion of prices for their music.[74] The likely effect on new and less established creators is unclear. While they do have the option to promote themselves through several of the ISPs, the long tail makes this ever more challenging. Whether current structures and regulations support the weaker parties in this market remains an open question.

What is the role of record labels in digital music distribution? After all, the costs of manufacturing and distributing records have declined drastically. So far, these intermediaries act as “gatekeepers” because the licensing deals have to be negotiated on a case-by-case basis and there is no statutory fee. Consequently, the “middle-man” is not yet dead in the digital world. Yet, roles are displaced. As the streaming services have grown in the number of subscribers they have signed up, so has their market power.[75] This has enabled the large streaming service providers to complete copyright agreements with the major record labels. This does not automatically imply that creators are better off. As we have noted, record labels are not obliged to redistribute the income to the creators unless this has been included in a provision of the recording contract. And even where the contract does provide for the distribution of revenue, the royalty rate is generally low given the inequality in bargaining power. Streaming services are often accused of giving creators low pay rates. However, there is some merit in arguing that these low royalty rates are derived from the fragmentation of copyright and the complex licensing agreements, leading to higher transaction costs. Recent changes in the music industry, as well as changes yet to come, may remedy this situation in order to create a competitive and sustainable streaming market.

[1] Alex Solo, “The Role of Copyright in an Age of Online Music Distribution” (2014) 19 Media and Arts Law Review 171-194.

[2] Richard Caves, Creative industries: Contracts between Arts and Commerce, Harvard University Press (2000), ch. 4.

[3] See e.g. Niva Elkin-Koren, “The Changing Nature of Books and the Uneasy Case for Copyright”, (2010-2011) 79 George Washington Law Review 101-133, and Morten Hviid, Sofia Izquierdo Sanchez, and Sabine Jacques, “From publishers to self-publishing: The disruptive effects of digitalisation on the book industry”, CREATe working paper 2017/06.

[4] This mirrors the rapid take-up of e-books once suitable devices had been developed.

[5] See https://www.diffen.com/difference/AAC_vs_MP3 (accessed 29 June 2018).

[6] About the Music Genome Project, see https://www.pandora.com/about/mgp (accessed 29 June 2018).

[7] Recent data from Statista illustrate the source of this. While Pandora pay $0.00134 per stream and Spotify pay $0.00397 per stream, Xbox pay as much as $0.02730 per stream. At the same time, Pandora and Spotify have a combined market share of 69.4%, see https://www.statista.com/chart/13407/music-streaming-who-pays-best (accessed 29 June 2018). See also section 3.2 below.

[8] See section 4.3 below.

[9] Spotify secures two types of licenses: mechanical rights and public performance rights.

[10] See section 4.2 below.

[11] See http://www.digitaltrends.com/music/spotify-vs-pandora/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[12] Recently, Spotify announced its wish to be listed as a public company, where its direct competitors will be Apple Music and Amazon Music. See https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/04/spotify-public-listing-ambition-struggling-musicians-stock-market (accessed 13 May 2018).

[13] https://musicindustryblog.wordpress.com/2017/07/14/amazon-is-now-the-3rd-biggest-music-subscription-service/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[14] See PRS press release, https://www.prsformusic.com/press/2016/prs-for-music-and-youtube-announce-extension-to-multi-territory-licensing-deal (accessed 16 February 2018).

[15] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-12-07/youtube-is-said-to-plan-new-music-subscription-service-for-march (accessed 29 June 2018); https://www.spin.com/2018/03/youtube-streaming-subscription-plan/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[16] Which can be explained by the changes in the legal framework as more and more, intermediaries are being held responsible for the content shared on their platforms (i.e. YouTube). See Sabine Jacques, Krzysztof Garstka, Morten Hviid & John Street, “Automated anti-piracy systems as copyright enforcement mechanism: a need to consider cultural diversity” (2018) 40(4) EIPR 218-229.

[17] https://musicbusinessresearch.wordpress.com/2017/07/30/the-uk-recorded-music-market-in-a-long-term-perspective-1975-2016/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[18] IFPI 2017 report, available at http://www.ifpi.org/downloads/GMR2017.pdf (accessed 29 June 2018), p. 17.

[19] Subsection 114(j)(6) and (7) of the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C.

[20] This push is fuelled not only by the music industry but also by companies wanting to advertise on these platforms. See https://www.wsj.com/amp/articles/unilever-threatens-to-reduce-ad-spending-on-tech-platforms-that-dont-combat-divisive-content-1518398578 (accessed 29 June 2018).

[21] See http://www.completemusicupdate.com/article/the-lovehate-relationships-continues-as-prs-renews-its-deal-with-youtube/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[22] 1988 c. 48.

[23] Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market; Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8/06/2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (“Directive on electronic commerce”); Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society. An important copyright reform is underway, see Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on copyright in the Digital Single Market COM(2016) 593 final.

[24] Mainly, the Berne convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886 (as amended on 28 September 1979), the Rome Convention 1961, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights 1994, the WIPO Copyright Treaty 1996, and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty 1996.

[25] C-5/08 Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening [2009] ECDR 16. The Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd & Ors v Meltwater Holding BV & Ors [2011] EWCA Civ 890; for more on the originality threshold, see Lionel Bently and Brad Sherman, Intellectual Property Law (Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 93-117.

[26] Section 3 CDPA 1988.

[27] Section 9(1) CDPA 1988. There are exceptions to this rule, for example see s. 11 CDPA 1988 (creations made in the course of employment).

[28] Also called “neighbouring right” or “related right”. Sound recording is to be interpreted in the broad sense, covering vinyl record, tapes, CDs, MP3, and other digital file formats.

[29] Section 9(2)(aa) CDPA 1988.

[30] Exclusivity is an important concept in copyright law which means that no one other than the right-holder is allowed to carry out one of the restricted acts set out in s. 16 CDPA 1988 without prior authorisation.

[31] Section 16 CDPA 1988.

[32] For more on moral rights, see Bently and Sherman, supra n. 25, pp. 272-291.

[33] Section 77 CDPA 1988.

[34] Section 84 CDPA 1988.

[35] Section 80 CDPA 1988.

[36] Section 78 CDPA 1988.

[37] Section 87(2) CDPA 1988.

[38] In other words, the protection of the musical performance. See s. 180(2) CDPA 1988.

[39] Directive 2006/115/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12/12/2006 on rental right and lending right and on certain rights related to copyright in the field of intellectual property (codified version).

[40] See e.g. Joseph Stiglitz, “Principal and Agent (ii)”, in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

[41] For performers’ rights, see ss. 182–182D CDPA 1988.

[42] See ss. 205J(2), 205L, and 205M CDPA 1988.

[43] Therefore, in addition to the international treaties mentioned in footnote n. 23 above, the US, French, German and Japanese legal frameworks seem to be of particular importance for this creative industry because it adds to the complications of doing business and hence to transaction costs of different players.

[44] Section 90 CDPA 1988.

[45] See e.g. Ariel Katz, “The potential demise of another natural monopoly: Rethinking the collective administration of performing rights” (2005) 1(3) Journal of Competition Law and Economics 541-593.

[46] As the owner of copyrights, PRS for Music can also either exercise the rights in the work itself or transfer these to a third party such as a publisher or other collecting society. Once a member of PRS for Music, the original copyright holder assigns the copyright subsisting in the current work together with the copyrights in future works.

[47] Steve Greenfield and Guy Osborn, “Copyright law and power in the music industry” in Simon Firth and Lee Marshall (eds.), Music and copyright (Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p. 96.

[48] Ann Harrison, Music: The Business (6th ed., Random House, 2014), pp. 73-89; Martin Kretschmer, George Klimis and Roger Wallis, “The Changing Location of Intellectual Property Rights in Music: A Study of Music Publishers, Collecting Societies and Media Conglomerates” (1999) 17 Prometheus: Critical Studies in Innovation, 178-186; Bernt Hugenholtz, “Adapting copyright to the information superhighway” in The Future of Copyright in a Digital Environment (The Hague, London, Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1996), p. 84.

[49] Lucie Guibault, Copyright and Contracts: An Analysis of the Contractual Overridability of Limitations on Copyright (The Hague: Kluwer, 2002), p. 205.

[50] Roger Wallis, “Copyright and the composer” in Simon Firth and Lee Marshall (eds.), Music and Copyright (Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p. 110.

[51] See section 4.1 infra.

[52] Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market OJ L 84, 20.3.2014, pp. 72–98; transposed in the UK by The Collective Management of Copyright (EU Directive) Regulations 2016.

[53] Supra, n. 59.

[54] Don Passman, All You Need to Know about the Music Business (London: Penguin books, 2011), pp. 63-82, and particularly p. 77.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] IFPI, Digital Music Report (2017), available at http://www.ifpi.org/downloads/GMR2017.pdf (accessed 29 June 2018).

[58] Data sources from Music and Copyright blog, available at https://musicandcopyright.wordpress.com/ (accessed 29 June 2018). The data for 2017 are not comparable with the past data as Music & Copyright’s 2017 review of their music publishing share methodology, see their May 15 2018 blog, https://musicandcopyright.wordpress.com/2018/05/15/umg-and-wmg-make-recorded-music-market-share-gains-sony-outperforms-in-publishing/ (accessed 29 June 2018). The new methodology finds a larger market share for the independents and a smaller market share for in particular UMG and WMG. The overall market shares for 2016 and 2017 using the new methodology appear largely stable.

[59] See: https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/major-labels-revenues-grew-1bn-2017-biggest-year/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[60] For a review of these, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses, see http://aristake.com/post/cd-baby-tunecore-ditto-mondotunes-zimbalam-or (accessed 29 June 2018).

[61] Reported in blog post “Amazon overtook Apple as UK’s biggest music retailer last year” on Music Business Worldwide (16 July 2015), available at http://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/amazon-sold-more-music-than-apple-in-the-uk-last-year/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[62] The UK recorded music market in a long-term perspective, 1975-2016, available at: https://musicbusinessresearch.wordpress.com/2017/07/30/the-uk-recorded-music-market-in-a-long-term-perspective-1975-2016/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[63] E.g. Bandbox, Bandcamp, Nimbit, Bandzoogle, Cash Music, MySpace, fm, Pledgemusic, ReverbNation, soundcloud, Songcast, Tunecore, Wazala, and Topspin.

[64] The difficulty with getting licences for a comprehensive coverage is highlighted in Morten Hviid, Simone Schroff, and John Street, “Regulating CMOs by competition: an incomplete answer to the licensing problem?” (2016) 7 Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and Electronic Commerce 256-270 (previously CREATe Working Paper 2016/03).

[65] The breakdown can be found at: http://www.prsformusic.com/creators/memberresources/mcpsroyalties/mcpsroyaltysources/onlineandmobile/jol/pages/jol.aspx (accessed 29 June 2018).

[66] More information about this new venture can be found at: https://www.prsformusic.com/iceservices/Pages/default.aspx (accessed 29 June 2018).

[67] https://basca.org.uk/public-affairs/thedaythemusicdied/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[68] As noted at supra n. 6, the streaming services with the larger market share pay the lower amount per stream.

[69] For more on intermediation, disintermediation, and re-intermediation in the record industry, see Francisco Bernardo and Luis Martins, “Disintermediation effects in the music business – a return to old times?” (2013), available at https://musicbusinessresearch.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/bernardo_desintermediation-effects-in-the-music-business.pdf (accessed 29 June 2018).

[70] Harrison, supra n. 51, p. 188, argues that this results in a shift of dynamics, empowering the creators and away from traditional record labels.

[71] BPI, “Music fans deliver verdict on digital versus physical: it’s not either/or – it’s BOTH!”, AudienceNet study (December 2015), available at https://eraltd.org/news-events/press-releases/2015/music-fans-deliver-verdict-on-digital-versus-physical-it-s-not-eitheror-it-s-both/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[72] According to a music industry blog, the share of label revenues for streaming was 34% in 2016 (23% in 2015), see https://musicindustryblog.wordpress.com/2017/02/26/global-recorded-market-music-market-shares-2016/ (accessed 29 June 2018).

[73] Richard Caves, Creative industries: Contracts between Arts and Commerce (Harvard University Press, 2000), ch. 4.

[74] The theoretical argument would be along the lines that an increase in creator bargaining power would raise the costs to the record labels and publishers. Because of their market power they will in turn add a mark-up to these increased costs, leading to an increase in wholesale prices. This in turn, with a more concentrated retail level, leads to a further mark-up of the higher wholesale price to yield a higher price to the consumer.

[75] At the moment, as argued above, growth is in terms of subscribers new to streaming. As the market becomes saturated, growth for an individual streaming service will have to come from converting the subscribers of other services. How that will alter the bargaining power both between streaming service providers and labels, and streaming services and consumers remains to be seen.