Volume 11, Issue 1, April 2014

Jeremy de Beer,* Alexandra Mogyoros,** and Sean Stidwill***

Cite as: J de Beer, A Mogyoros and S Stidwell, “Present Thinking About the Future of Intellectual Property: A Literature Review”, (2014) 11:1 SCRIPTed 69 http://script-ed.org/?p=1349

Download PDF

DOI: 10.2966/scrip.110114.69

![]() © Jeremy de Beer, Alexandra

Mogyoros, and Sean Stidwill 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please click on the link to

read the terms and conditions.

© Jeremy de Beer, Alexandra

Mogyoros, and Sean Stidwill 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please click on the link to

read the terms and conditions.

1. Introduction

People have often mistaken the uncertain and non-predictive nature of the future as a reason to not consider it.[1] However, those who insufficiently consider the future will find themselves reacting to it, rather than seamlessly adapting to, or possibly even shaping it. Not only is the future relevant in its own right, but the way we think about the future influences how we think and behave in the present.[2] Thus, truly informative work about the future must do more than predict. It must identify our pre-conceptions and assumptions about the present, and challenge our understanding of how the future may unfold.

Intellectual property (IP) researchers and practitioners seem concerned with what the future will bring.[3] Nevertheless, despite the reviews of the growing body of empirical literature addressing historical and contemporary intellectual property issues,[4] little is known about the extent and nature of literature considering the future of intellectual property.

To understand better the current thinking on the future of intellectual property, this paper undertakes a systematic literature review, and provides corresponding recommendations for future scholarship. To this end, first, we provide an overview of what is meant by futures studies, foresight, and scenarios. Second, we outline the methods used for our literature review and provide an overview of our results. Third, we synthesise and analyse our findings. Fourth, we discuss the implications of our review and explore an emerging trend to consider the future in a more systematic way by using a tool called “scenarios”. Fifth and finally, we conclude by considering the benefits and potential disadvantages of using scenarios as a tool for exploring the future of IP.

2. Futures Studies, Foresight and Scenarios

Dator’s First Law of Futures holds: “The future cannot be predicted because the future does not exist”.[5] Nevertheless, different cultures, fields, and disciplines have all recognised the future as an area worthy of exploration.[6] Future exploration, also known by some as “futures studies”, has many forms. While there is inconsistency around the terms describing different philosophies and approaches to considering the future,[7] this paper focuses on one way to consider the future—foresight.

“Foresight” is an umbrella term for a way of thinking about and exploring the future according to a several core principles. Foresighting is often contrasted to its predecessor forecasting. Forecasting practitioners subscribe to the notion that given sufficient data, and the right algorithm, they can analyse trends and predict the future such that the future becomes relatively known. In contrast, foresight practitioners do not believe there is only one future. They consider that the future can take various shapes and forms depending on a multitude of factors, some known and some unknown. In the practice of foresight, one does not try to collect sufficient data to make accurate predictions about the future. Rather, one attempts to understand the different possible futures that might unfold, and understand why trends and factors may drive the future in one direction versus another equally plausible one.

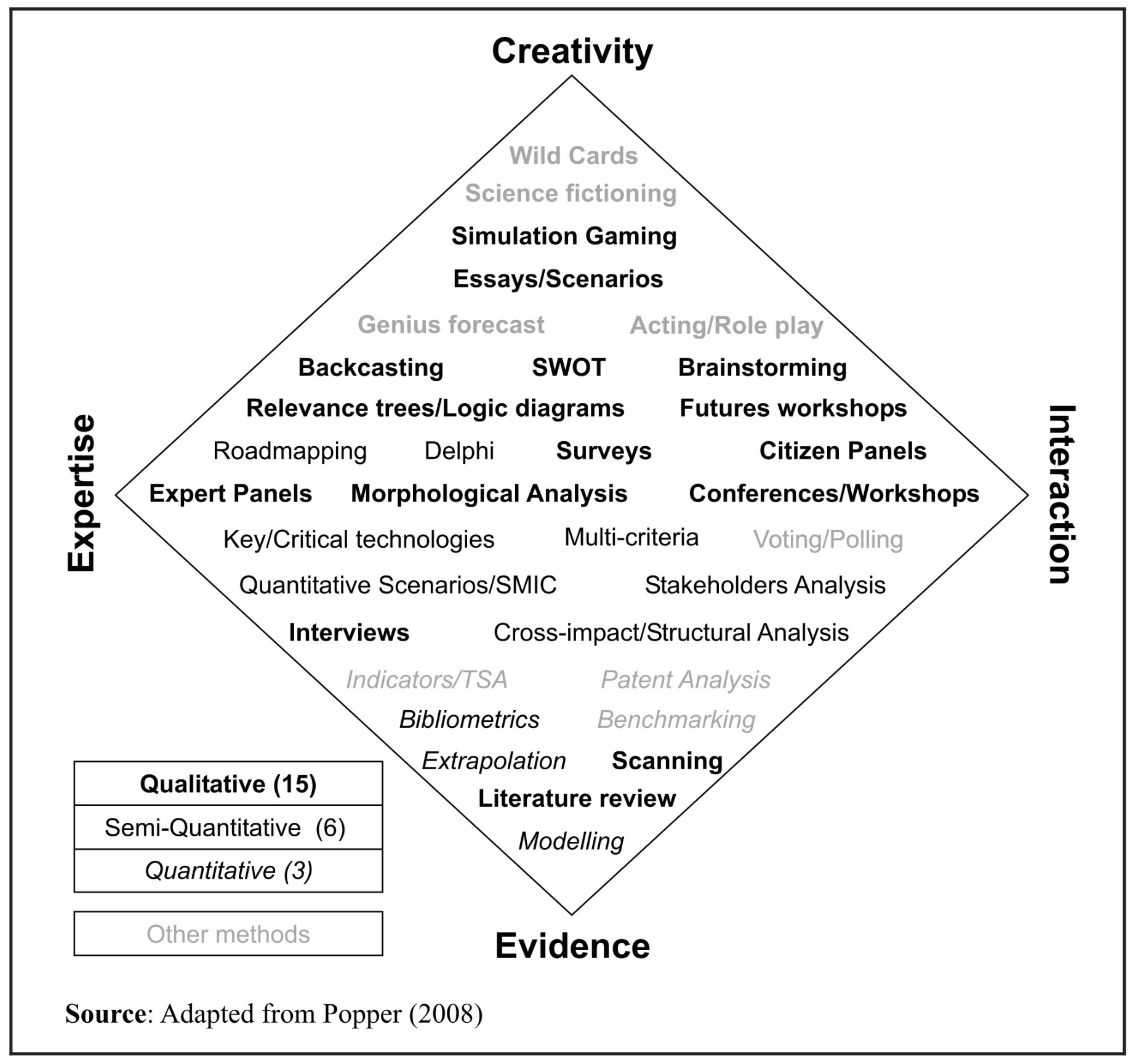

Championed in the fields of management and futures studies, foresight is a powerful tool and method to consider the future. After the Royal Dutch Shell Company popularised foresight in the 1970s, multi-national corporations[8] and governments[9] have been its primary users in recent years.[10] As these foresight users tended to practise foresight in confidential and commercial ventures, foresight methods and theories remained obscured until recently, when research projects, non-profit organisations, and grass-root groups began to make use of these tools.[11] As a result, there has been an increased discussion in the literature regarding different ways to engage in foresight. To date, there are over thirty generally accepted foresight methods.[12] These range from scenarios, to road mapping, to SWOT analyses, to expert panels, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The foresight diamond: Various methods for conducting foresight research[13]

Notwithstanding the range of accepted methods, scenarios remain the most predominant way of engaging in foresight.[14] The ultimate goal of scenarios is to form different “stories” or narratives that describe a plausible future state:[15]

Scenarios are alternative stories of how the future may unfold. They are not predictions or forecasts, but credible, consistent and challenging stories that help to focus on the critical uncertainties and to understand the balance of forces that will shape the future.[16]

The significance of scenarios comes in large part from its ability to allow for, and articulate, multiple possible futures. By describing multiple plausible and differentiated scenarios, a scenario exercise ideally challenges its readers to consider what assumptions they hold about how the future will unfold, and bring to light relevant factors that may shape the future in a variety of unpredictable ways.

Regardless of the tools one uses, all foresight methods optimally identify uncertainties that lie ahead. Thus perhaps the greatest contribution of foresight thinking is that rather than treat uncertainties as a crippling obstacle to planning, foresight embraces uncertainty. Foresight’s ability to re-contextualise uncertainty in a way that gives it value is a utility that extends over a range of disciplines and fields. As the goals of foresight are broad and accommodating, foresight can be successfully used in a wide range of projects. Foresight is about challenging how people think about the future, and perhaps more importantly, how they act in the present.

Accordingly, the value in foresight comes less from a resulting product, and more from the potential to change the mind-set of those exposed to it:

To operate in an uncertain world, people needed to be able to re-perceive – to question their assumptions about the way the world works, so that they could see the world more clearly…The end result, however, is not an accurate picture of tomorrow, but better decisions about the future.[17]

Foresight methods are becoming increasingly commonplace in scholarly research, especially research focussed on achieving practical, policy-relevant results. One recent research project provides a good example of the application of foresight methods in a scholarly context: the Open African Innovation Research and Training project, “Open AIR.” Between 2011-2014, the Open AIR project took a two-pronged approach to investing the role of IP rights as a tool for collaboration on the African continent. In addition to a series of empirical case studies on current realities across 14 African countries, a network of nearly 50 researchers embarked on a foresight exercise to construct plausible scenarios for the future. The results of this exercise are reported in further detail in the discussion section of this article. For now, it is merely notably that this literature review of presenting thinking about the future of IP was among the first steps toward that much broader scenario-building research. The Open AIR project’s foresight research methods were inspired by work on a related project investigating the future of agricultural genomics, the Value Addition through Genomics and GE3LS project, VALGEN.

Given the unique value of foresight over less methodical and rigorous ways of treating the future, and its planned use as a key component of the Open AIR project’s research methodology, this article asks how and to what extent IP scholars currently consider the future. Moreover, this paper inquires to what degree the treatment of the future in existing IP scholarship is congruent with foresight principles and methods.

3. Methods and Results

3.1 Methods

This literature review considers how intellectual property researchers and practitioners think about the future. To answer this question, we used general literature review methods, canvassing both academic and grey literature on the future of IP. [18] The goal was not to conduct a comprehensive review of every possible work ever written about the future of IP, but rather, to conduct a representative review that illustrates dominant trends in this field. The databases selected reflect our goal to explore the literature contained in an array of databases covering different subject matters, not to exhaustively amass all potentially relevant works. We selected both legal and non-legal databases to ensure we did not overlook relevant works because of their disciplinary classification. And while our list is not exhaustive, we consciously selected databases that include all relevant disciplines and major journals germane to both intellectual property and futures studies.

In our review of the academic literature, we considered publications from the following five databases:

· Social Science Research Network (SSRN): A publicly available database that covers a wide range of social science (including legal) research and often publishes work that has not been published in peer reviewed journals thus providing access to a broad range of works.[19]

· Business Source Complete: A database that provides access to journals on a wide range of business and management topics, including works exploring strategic future planning.[20]

· ScienceDirect: A comprehensive general database that reviews an array of subject areas within the social sciences, humanities, science, and business studies.[21]

· Index to Legal Periodicals and Books, Full Text: A legal database that provides comprehensive coverage of the legal landscape including interdisciplinary legal works. This database has international coverage including journals from the U.S., Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand.[22]

· Legal Source: A legal database offering a collection with a wide coverage of legal disciplines from more than 880 full-text journals and 300 law reviews. Full-text coverage includes the world’s most respected scholarly law journals.[23]

In addition to reviewing the academic literature, this review considered the grey literature. Grey literature includes published and unpublished material that may not be included in academic databases, for example government reports and white papers.[24] We reviewed the grey literature by footnote chasing,[25] and targeted searches. However, our search of the grey literature did not include a review of the media; accordingly, sources such as blogs, online news outlets, websites, and tweets were not included in the review. Generally, we also excluded books from our analysis, although we nevertheless became aware of relevant monographs, mainstream titles, and edited collections.

We searched the databases and grey literature for works containing the keywords: “intellectual property” or “copyright” or “patent” or “trademark” and “future” or “foresight”. We selected these search terms to capture works that considered intellectual property rights and systems as a whole, as well as work that treated only one branch of intellectual property. Our keyword searches were dictated by tensions between completeness and manageability. For example, adding future-related terms such as “21st century” or “potential” returned thousands of ostensibly irrelevant results; an impractical number for meaningful analysis.

Where possible, we searched for articles that contained the search terms in the title, abstract, keywords or the text of the article itself. However, given the differences in each database, we altered this parameter to fit the format of each database while being as broad as possible.[26] We searched only for English sources with no limitation as to time period.[27] No qualitative screen was applied at this stage.

We screened each result for relevancy and coded the results as either “relevant” or “not-relevant”. We coded work that addressed the research question with any degree of relevance as long as it considered the future of intellectual property in any capacity, even peripherally. To aid with the coding process we asked, “Does this work consider the future of an intellectual property issue?” or “Is this a paper that looks at the future of an industry or topic, on which IP has some relevance?” We coded only the former as relevant. Upon reviewing the results, it became clear that a large body of literature contained the word “future” but did not consider the future of IP rights, systems, laws, or policy and was thus not relevant to our research question. We coded these works as “not relevant”.[28]

We further classified all relevant works by their attributes (see Table 1). The first division considered whether the work treated the future in a primary or ancillary manner. This determination rested on how the work treated the future. We coded a work as being primary where the future was central to the analysis, formed a substantial and fundamental aspect of the thesis, or was discussed for a majority of the paper. In contrast, we coded a work as ancillary where the future was auxiliary to the main thesis or thrust of the paper. In these works, the author often treated the future as an afterthought, or only discussed the future in the concluding section of a work focused on another topic.

Next, we asked whether primary works were conceptualising the future in a predictable or uncertain way. We coded works as predictable where the future was understood as being the inevitable or likely consequence of a given trigger or situation. These works did not necessarily predict the future per se, but framed the future as following from a given stimulus in a linear fashion. In contrast, uncertain works engaged with the future as an unknown entity. Uncertain works acknowledged the possibility of multiple plausible scenarios for the future.

Table 1: Attributes of Relevant Works Addressing the Future of IP

|

Classification |

Attributes |

|

Ancillary |

The future is considered as an afterthought or secondary to the authors’ primary analysis, usually discussed only in a concluding section of a work focussed on current issues. |

|

Predictable |

The future is considered as central to the analysis, but tends to be forecasted in a linear manner, typically predicting effects of a particular cause or causes. |

|

Uncertain |

Multiple, challenging, plausible scenarios for the future are imagined, none of which are predicted as inevitable but rather depend on systemic forces, often external to IP. |

We further classified all works primarily about the future of IP according to other characteristics. This included the geographic focus of the work, the breadth of analysis of the future, and what factors or trends authors considered to drive or shape the future.

The geographic focus of each primary work was identified and coded as being either: local, national, regional, international, or global. We coded works as regional where the authors considered countries that were connected by either geography, such as North America, culturally, such as Scandinavia, or politically, such as the European Union. In contrast, we coded works as international where they dealt with at least two countries that were not in the same region. We coded works as global where the work treated the issue at large without emphasising regional or national delineations.

Next, we classified each primary work by its breadth of analysis (see Table 2). We coded work as being systemic, categorical, or issue-specific.

Table 2: Classification of Primary Works by Breadth of Analysis

|

Classification |

Attributes |

Examples of Topics |

|

Systemic |

The work considers IP laws on a systems level, IP rights systems, or regimes. |

International intellectual property regimes; WIPO’s development agenda, intellectual property rights |

|

Categorical |

The work considers a specific branch of intellectual property. |

Copyrights; patents; trademarks |

|

Issue-Specific |

The work considers a topic that either falls within a specific branch of intellectual property, or a specific industry or topic that may cross over different branches of IP law. |

Pharmaceutical industry; opt-out copyright regimes; biotechnology litigation; the music industry; film piracy |

Last, we examined all primary works to determine the factors or trends that authors identified as driving and shaping the future. We coded these as being: legal, economic, technological/scientific, political, social, or religious/ethical. We did not treat these drivers as mutually exclusive categories; we noted all drivers that an author substantially engaged with.

3.2 Results

The formal literature review returned 5,620 results. From the formal literature review only 226 unique results were relevant to our research question (see Table 3).[29] Our grey literature review uncovered three relevant works: the European Patent Office (EPO)’s “Scenarios for the Future”, Gollin, Hinze and Wong’s “Scenario Planning on the Future of Intellectual Property: Literature Review and Implications for Human Development”, and Halbert’s article Intellectual Property in the Year 2025.[30] Thus, there were a total of 229 unique relevant results.

Table 3: Results by Relevance of Formal Literature Review[31]

|

Database |

Total Results |

Relevant Results |

Duplicate Results |

Unique Results |

|

Social Science Research Network |

1,148 |

50 |

0 |

|

|

Business Source Complete |

1,474 |

13 |

1 |

|

|

Science Direct |

849 |

11 |

1 |

|

|

Index to Legal Periodicals and Books |

1,494 |

8 |

0 |

|

|

Legal Source |

655 |

154 |

8 |

|

|

Total |

5620 |

236 |

10 |

226 |

4. Analysis

To facilitate analysis and develop the recommendations presented at the end of this article, we analysed the results of our literature review in light of the characteristics and attributes described above. Our review of relevant works identified several clusters of scholarship.

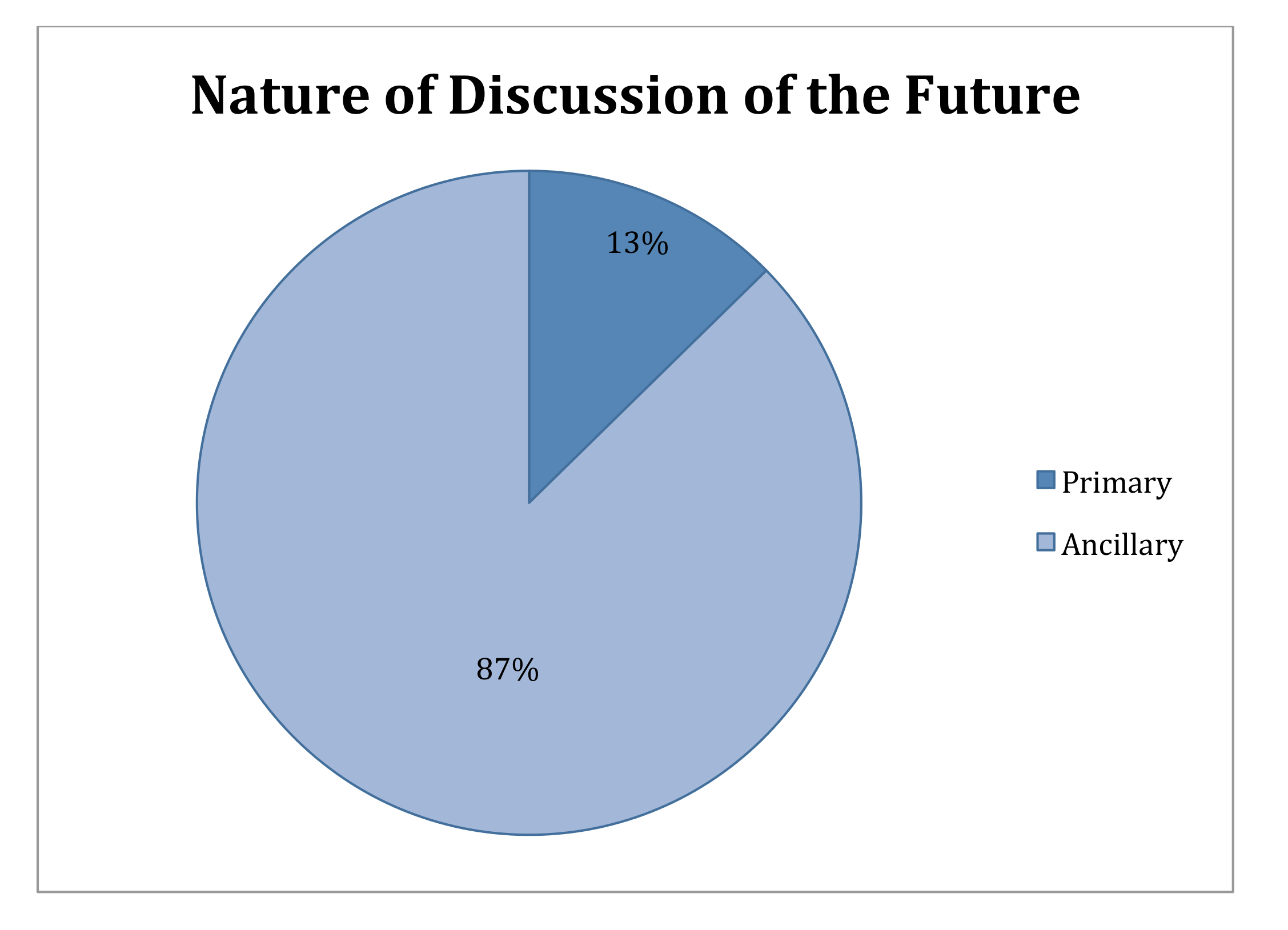

Relevant work that considers the future of intellectual property often does so as an afterthought or an addendum to a primary analysis.[32] As seen in Figure 2, the overwhelming majority of works (87.3%) we identified as relevant considered the future in an ancillary way.

Figure 2: Does the work treat the future as a primary or ancillary issue?

As just one illustration of this tendency, in “The ‘Compulsory Licence’ Regime in India: Past, Present and Future”, Basheer and Kochupillai’s analysis of the future of India’s licencing system is limited to the paper’s concluding remarks. Consequently, this paper provides a limited analysis on the future of the compulsory licensing regime in India.[33]

This disjunctive consideration of the future may be interpreted in one of two ways. The first is that exploring the future is not a central concern for intellectual property scholars. Instead, considerations of the future are seen as an appropriate way to conclude a work and give it relevancy going forward. The second possible interpretation is that intellectual property scholars may feel ill equipped to engage in a meaningful discussion on the future of intellectual property. This is likely because those trained in IP are not trained as futurists and cannot necessarily uptake futures methods when treating the future of IP.

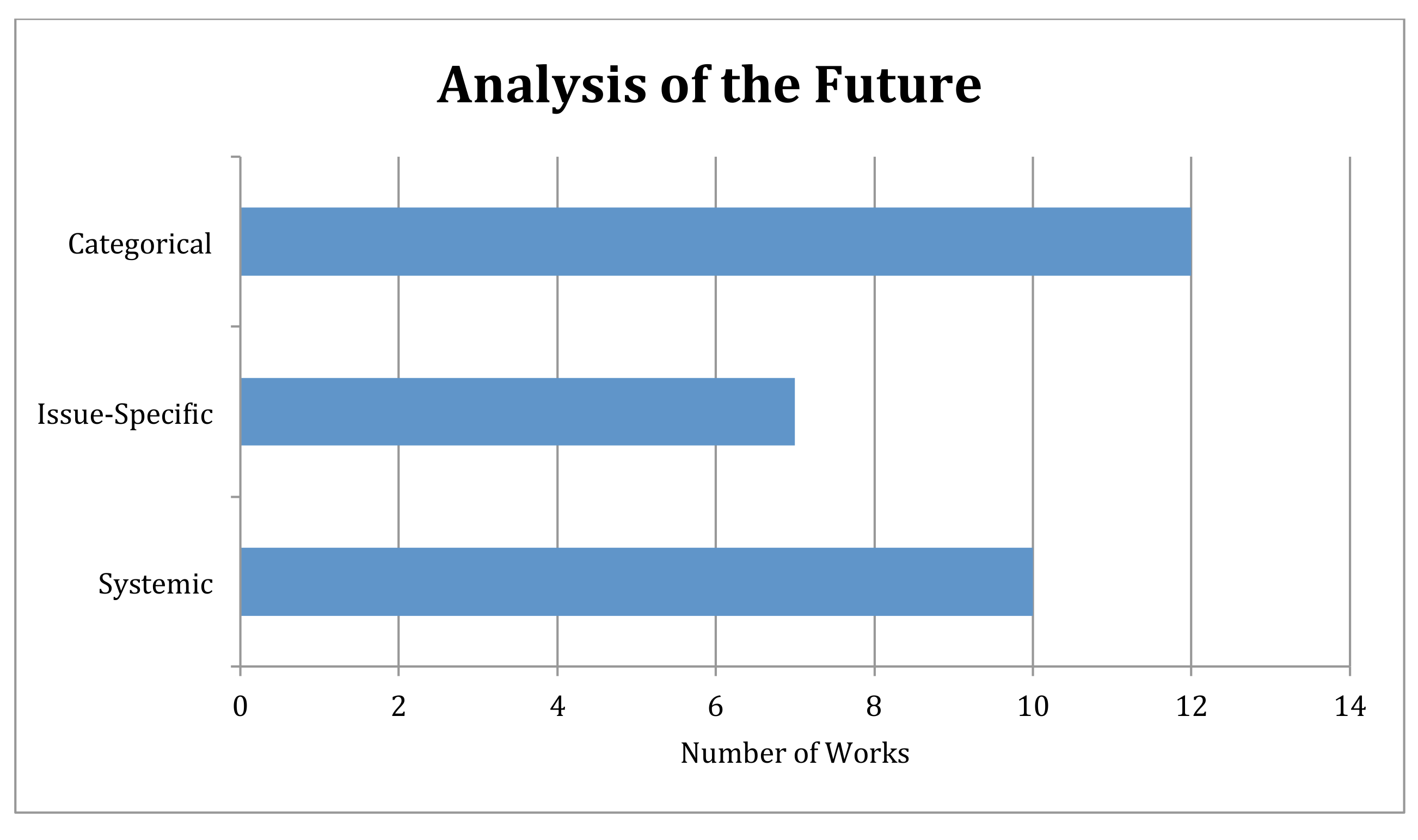

We coded all primary relevant works by the breadth of the analysis. Primary works most frequently considered categorical issues within IP (see Figure 3). Many works considering the future of intellectual property consider the future of a narrow, discrete area or future implications of a singular event. Some works considered the implications of a specific legal case, as in Risch’s “Forward to the Past” which considered the future of patent jurisprudence and innovation in the United States following the Supreme Court decision in Bilski v Kappos.[34] Other works considered the future of discrete events or areas of IP law, such as the future of: open source software development;[35] an opt-out copyright system;[36] the Internet, specifically online services like Google and YouTube;[37] patent information centres in Europe, specifically Bavaria;[38] database protection and information patents;[39] counterfeiting and privacy;[40] and the well-known mark protection regime in China.[41]

Figure 3: What is the breadth of

works’ analysis of the future?

Figure 3: What is the breadth of

works’ analysis of the future?

By identifying a “cause” and then describing a correlated “effect”, categorical and issue-specific works tend to consider the future in a predictive and linear way. In fact, fewer than 1 in 5 unique relevant sources that did not consider the future in an ancillary manner treated the future as open-ended and uncertain.[42]

Taken together, this body of work creates a piecemeal image of the predicted future of IP. Some of the topics addressed are quite distinct from one another and it is logical to treat them discretely, such as the Bavarian patent system and well-known marks in China. However, other topics, such as the future of an opt-out copyright system and the future of open source software development, are interrelated and will likely impact on one another. The effect of considering the future of some of these areas separately is that it may be difficult to understand the ways in which topics may overlap and impact one another. While this approach may be natural for intellectual property subject matter experts, rather than researchers experienced in the social science of future studies, it is not ideal.

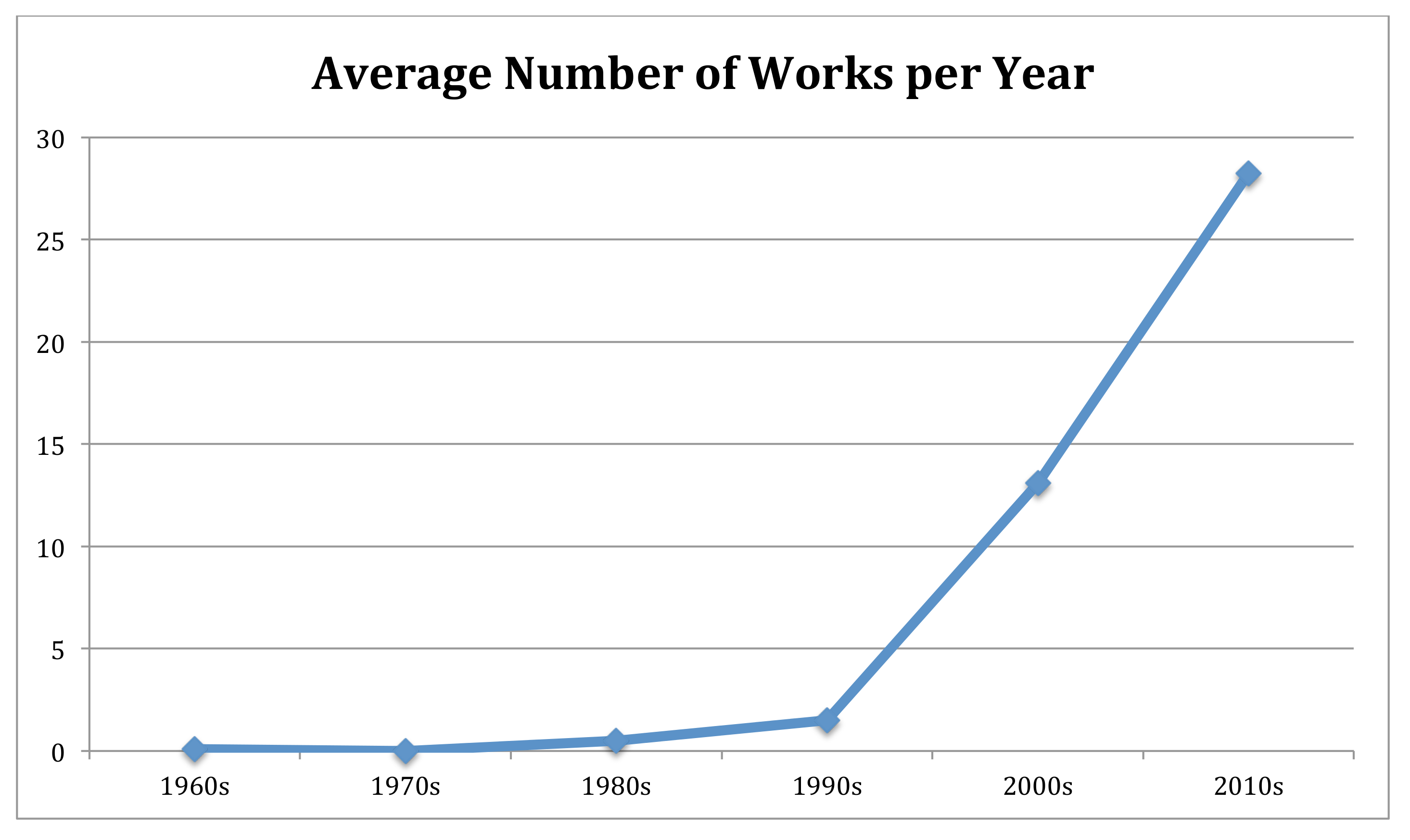

It is apparent that the body of literature relevant to the future of IP is growing. More than 91% of relevant works have been published since the year 2000. While we have not correlated the growth trends of future-focused IP scholarship with IP scholarship generally, it is not surprising to us that greater attention has been paid to the future of IP following the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPs).

Figure 4: How is the body of

relevant works growing over time?[43]

Figure 4: How is the body of

relevant works growing over time?[43]

The literature we reviewed often considered factors that may drive the future of intellectual property. These driving forces include copyright law,[44] human rights,[45] monopolies,[46] decreasing concern for human health and environmental safety,[47] resistance of harmonised international intellectual property regimes,[48] legislative and jurisprudential changes in patent law,[49] and accelerated use of user-generated content.[50] Identifying the sources of change in intellectual property is essential in considering the future of IP.

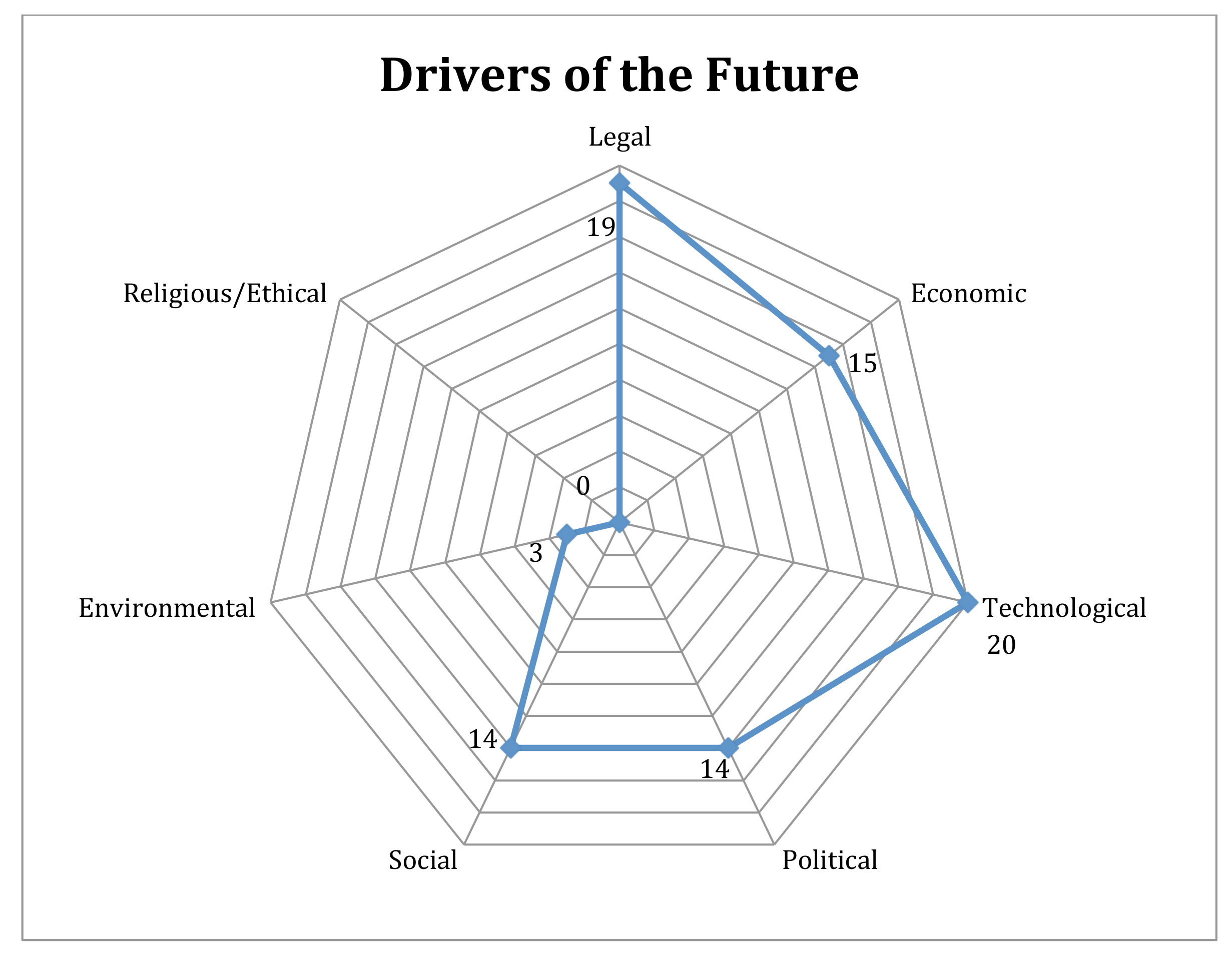

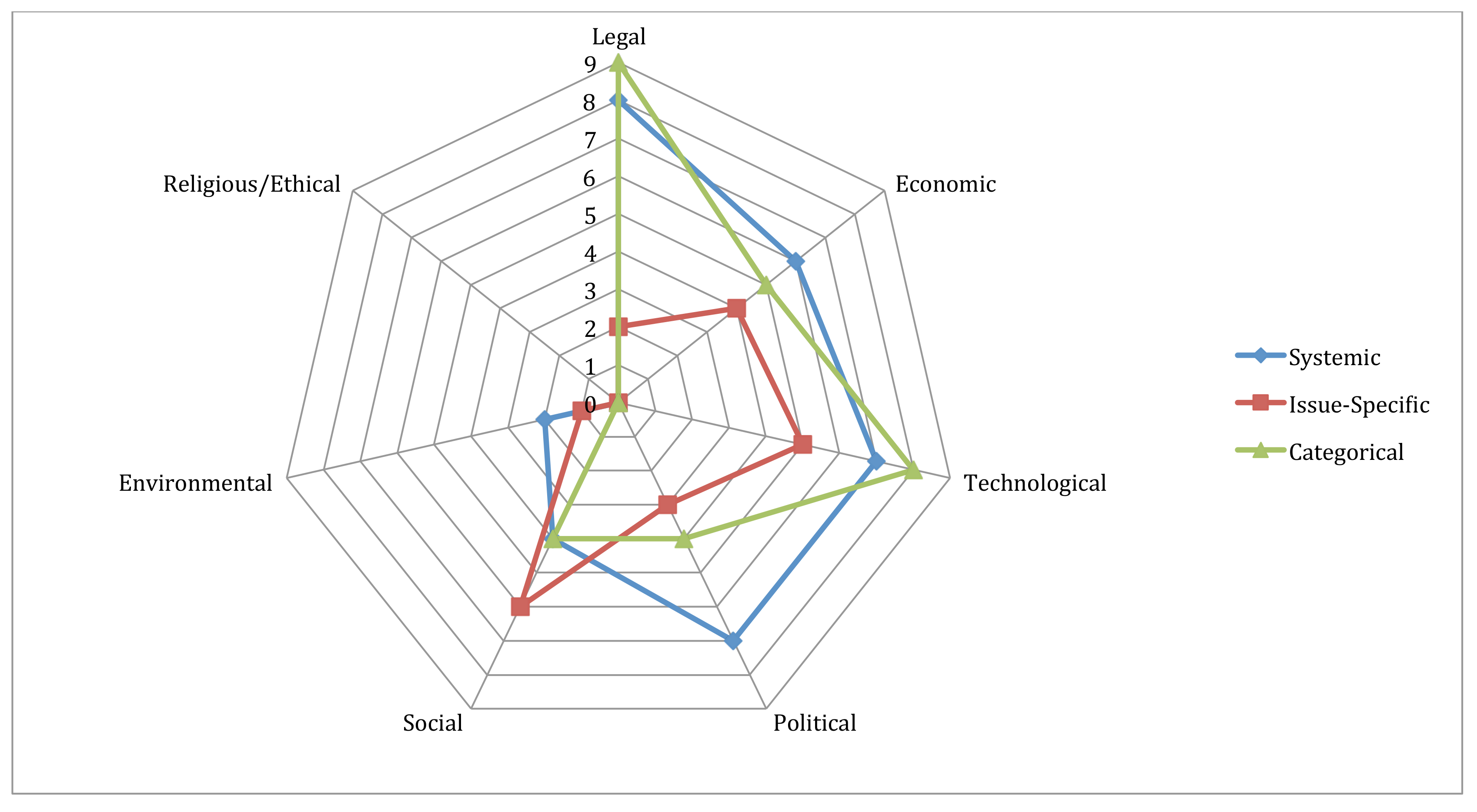

When looking at the different possible drivers of the future that authors considered, we can see in Figure 5 that legal, technological, and economic drivers are the most treated in the literature. However, when we correlate the drivers of the future by breadth of analysis, as seen in Figure 6, we see that works considering categorical topics in IP also tend to most consider legal and technological drivers. The type of topics that the categorical works explored may explain this. Of the twelve works we coded as exploring a categorical topic, eight of those looked at copyright issues. With this in mind, it makes sense that authors would identify the future of copyright law as being driven by technological advancements, as new ways of accessing and experiencing copyrighted works will have an impact on our laws that govern them.

Figure 5: What factors drive change and determine the future?

Figure 6: Which drivers of change

are considered in different analyses?

Figure 6: Which drivers of change

are considered in different analyses?

Also as shown in Figure 6, works classified as systemic deal with the future of IP systemically and tend to emphasise political and economic drivers of change, while works focused on specific issues emphasise social drivers. Most works consider factors and elements within intellectual property law, and closely related fields, as drivers of change, such as economics and politics.[51] With some exceptions such as Helfer’s work on human rights and intellectual property,[52] most discussion of the future is focused on factors internal to IP law, rather than external driving forces. For example, none of the works we examined appeared to consider the role of religious/ethical trends or factors in shaping the future of IP. Similarly, only three papers considered the role of environmental factors in shaping the future.[53]

This introspective analysis imposes serious limitations on the ability of intellectual property researchers to understand or enlighten their field of study. In addition, in identifying forces that will drive future change, most work considers the evolution or growth of a discrete aspect of intellectual property law. As examples, works consider what will drive the changes of the European Patent Documentation Group,[54] or disparate aspects of the future of American copyright law.[55] Few works consider what will drive changes of the intellectual property regime on a systems-based scale. Accordingly, most works that mention the future of intellectual property are generally less relevant than they might otherwise be.

Table 4: Depth of the Works and the Result of the Analysis

|

Depth |

Number of Works |

|

|

Ancillary |

200 |

|

|

Primary |

Predictable |

24 |

|

Uncertain |

5 |

|

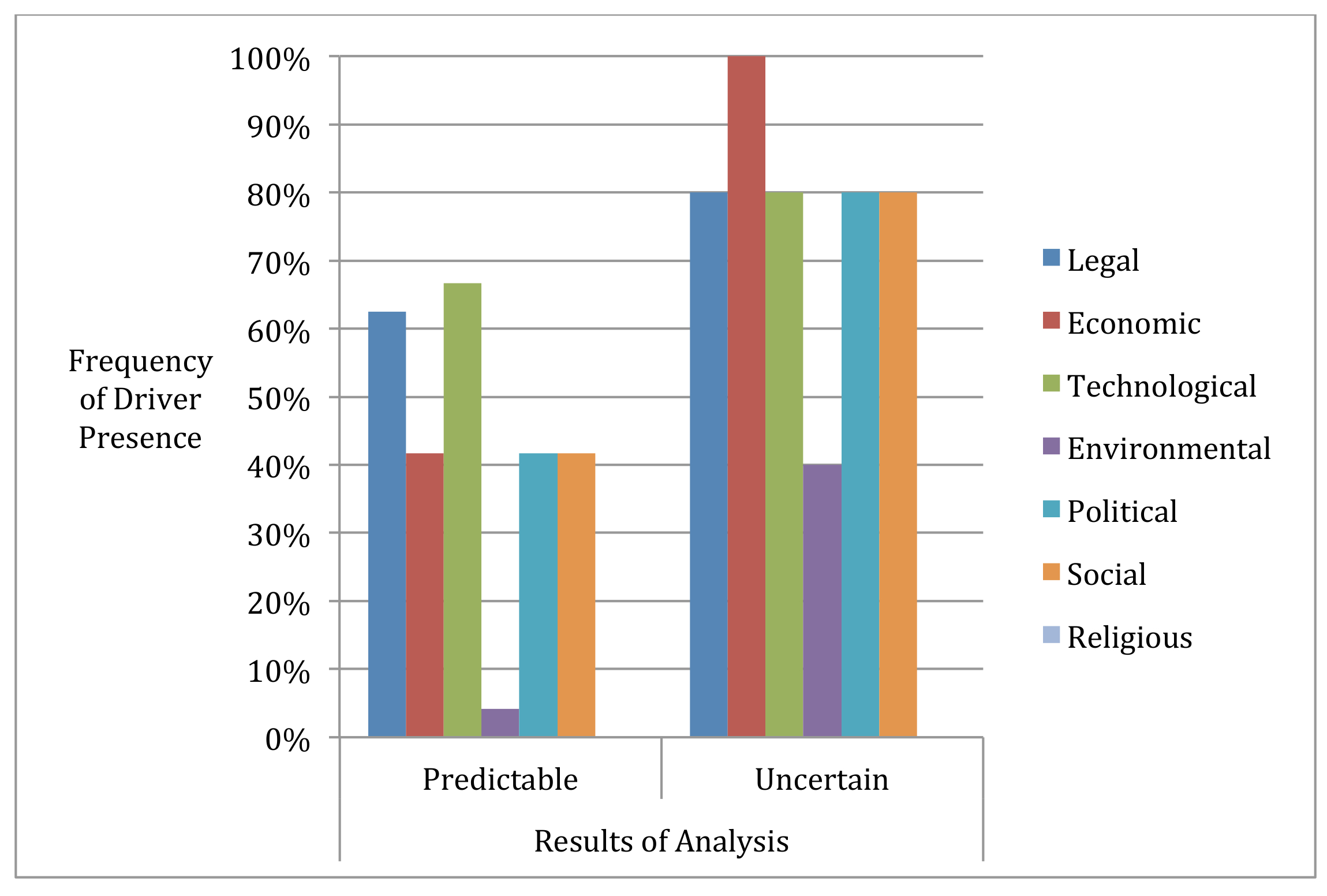

This trend, however, appears to exist primarily in works that consider the future in a predictive way. It is more common to see a greater variety of drivers of the future considered in works that treat the future as uncertain (see Figure 7). In fact, five of the seven kinds of drivers of change are present at least 80% of the time in works treating the future as inherently uncertain. By contrast, where a work was coded as predictable, the frequency of any given driver being present dropped below 70%. Thus, where scholars acknowledge the multiplicity of plausible futures they appear to take a more holistic approach to considering the drivers of the future.

Figure 7: Do different drivers of

change correspond to the way the future is conceived?

Figure 7: Do different drivers of

change correspond to the way the future is conceived?

Very few of the works found in our literature review use a methodological approach to thinking about the future of intellectual property, or take a specific foresight approach, such as scenarios. Scenarios are essentially stories about the way the world may turn out in the future, as previously discussed.[56] While there are many different ways to construct scenarios,[57] at their core, they are ways in which we can identify certainties and uncertainties about the future, and examine our understanding of the different ways in which they may unfold.

This group of works includes: (i) Halbert’s “Intellectual Property Law, Technology, and Our Probable Future”[58] and “Intellectual Property in the Year 2025”[59]; (ii) Gollin, Hinze and Wong’s chapter “Scenario Planning on the Future of Intellectual Property: Literature Review and Implications for Human Development” in Intellectual Property and Human Development[60]; (iii) de Beer and Bannerman’s “Foresight into the Future of WIPO’s Development Agenda”[61]; and (iv) the European Patent Offices’ “Scenarios for the Future”.[62]

Halbert’s work systematically considers the future of intellectual property by creating narratives of different future worlds—scenarios—to address possible future realities. In “Intellectual Property Law, Technology, and Our Probable Future”, Halbert contemplates the future of intellectual property law and technology by exploring the issues through the lens of two different alternative scenarios. The first scenario, “Business as Usual”, shows a trend towards all information being treated as property. Halbert’s second scenario, “Hackers and the Future” illuminates a world where one of the primary desires is to set information free and information becomes a self-standing entity. In creating these scenarios, Halbert identifies the importance of looking outside the law to develop an alternative discourse on intellectual property. She explores how certain factors and constant elements in IP discourse, namely the language of property and the legal system, inform how we conceive, understand, and will shape the future of IP law. She invites her readers to consider what may be constraining our vision of the future, and challenges us to think outside traditional expectations and norms.

Halbert’s second work, “Intellectual Property in the Year 2025” also uses scenarios to discuss the future. Halbert’s goal in doing so is:

[To] open a discussion on the contemporary state of intellectual property law and how we would like to see it develop in the next twenty-five years. By defining some of the possibilities, it becomes more likely that we can begin a future-oriented debate that will bring us to our most desirable future.[63]

In this article, Halbert outlines three scenarios, each of which builds off of a different set of assumptions. She stresses the importance of futures work to challenge our conceptions about the future and to recognise that it is unlikely the future will be similar to today.

Gollin, Hinze and Wong in “Scenario Planning on the Future of Intellectual Property: Literature Review and Implications for Human Development” undertake a relatively organic literature review, exploring the way in which scenarios have been used to address the future of IP and development issues. The authors define scenarios as stories that describe an alternative possible future outcome.[64] In this chapter, the authors mention Halbert’s work, the EPO scenarios, as well as work exploring the future of agricultural systems and information technologies.[65]

They conclude their chapter by identifying three alternative futures for IP in the specific context of development.[66] In the first alternate future, Gollin, Hinze and Wong identify a world where countries become compliant with the WTO’s regime in IP rights through an incremental expansion of these rights.[67] Their second future posits a broad expansion of protection for all types of IP worldwide. In the authors’ third world, IP protection is reduced. Gollin, Hinze and Wong use scenarios not only to explore the future of intellectual property and development, but also as a way to organise and conceptualise the conclusions of their research.

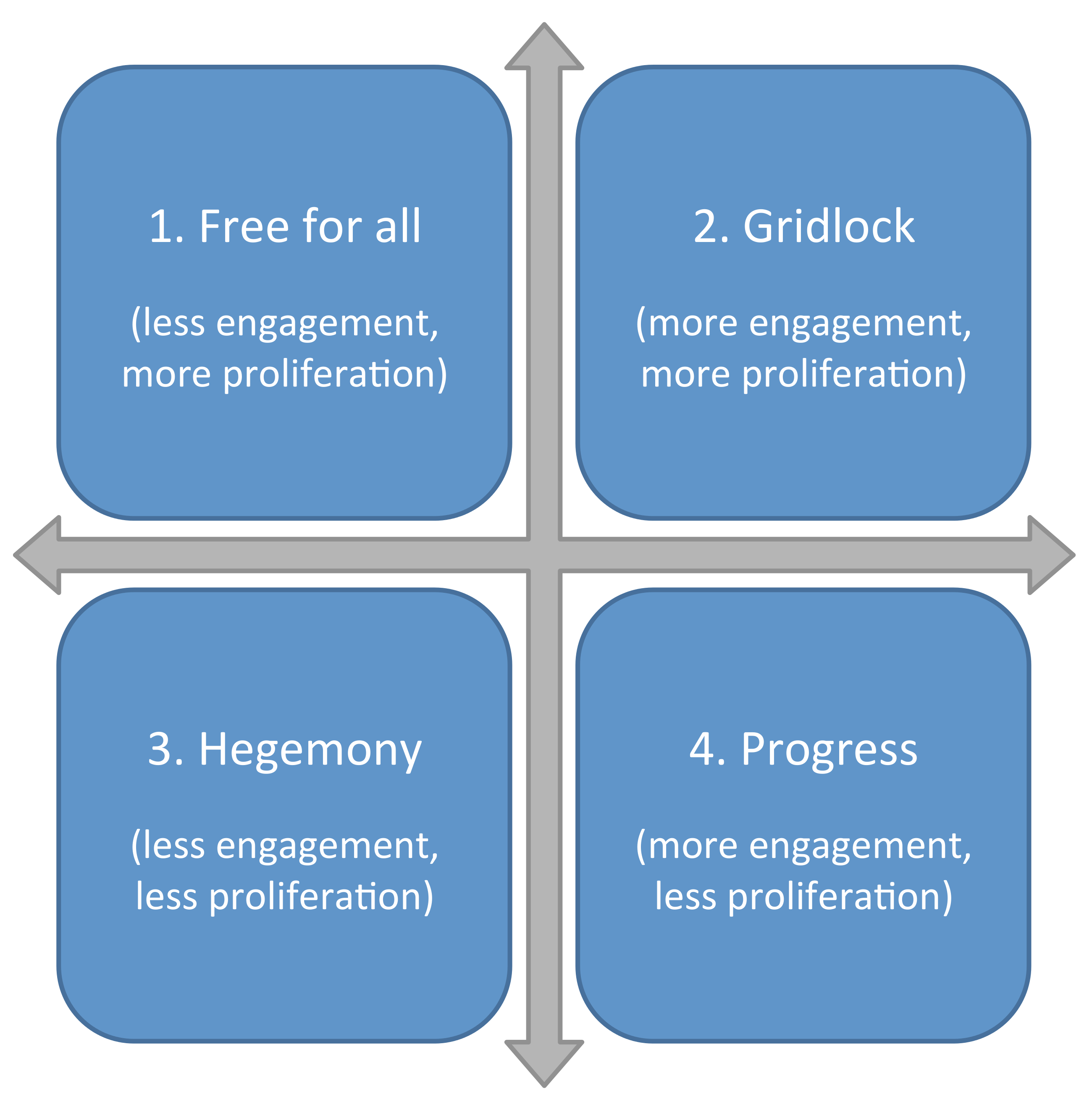

Similarly, de Beer and Bannerman consider the future of international IP in the article “Foresight into the future of WIPO’s Development Agenda”.[68] This work addresses the future of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) by exploring different plausible future worlds for WIPO’s development agenda. Building on what participants in a scenario-building workshop identified as two critical uncertainties, member state engagement and forum proliferation, de Beer and Bannerman created four different, but possible, future states for the year 2020, as seen in Figure 8.

De Beer and Bannerman explain that these scenarios help conceptualise and better understand uncertainties regarding the future of WIPO’s development agenda. Furthermore, they argue that acknowledging different possible futures is essential to be prepared for all possible futures, and will allow work towards a preferred future.

Figure 8: Scenarios for the Future of WIPO’s Development Agenda, based on member state engagement and forum proliferation[69]

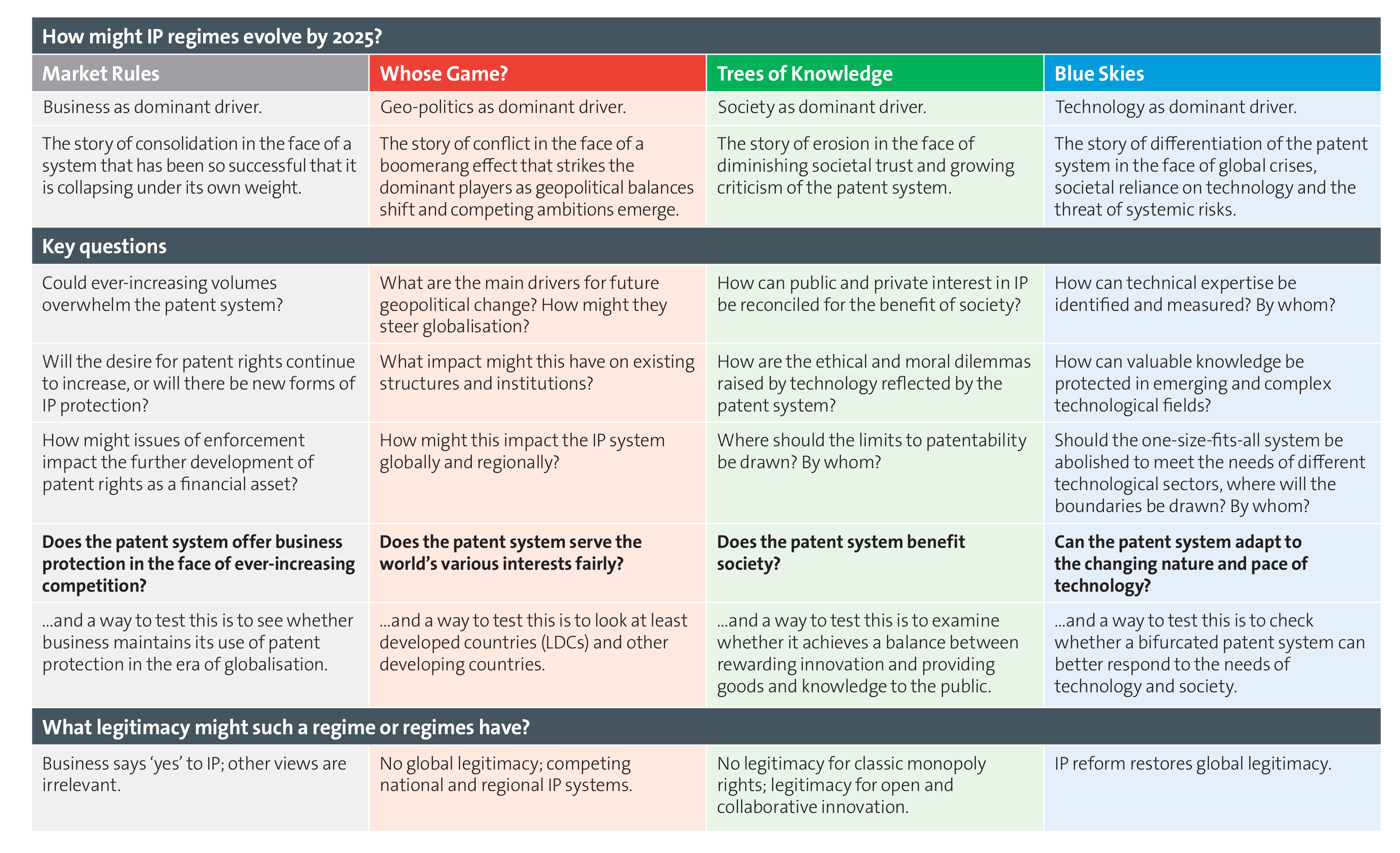

Last, the European Patent Office’s “Scenarios for the Future” presents a sophisticated analysis for the future of IP, and in particular, of the patent system. This report identifies four possible futures for IP regimes in 2025, as seen in Figure 9. These four scenarios all describe equally plausible future states of IP regimes. These scenarios were made by building off of extensive desk research, interviews, and collaborative workshops. EPO’s motivating goal behind this project was to better understand the landscape of patent systems and the future of patent systems and to stimulate questions for policymakers and decision makers.[70]

Figure

9: Overview of four scenarios from the EPO’s “Scenarios

for the Future”[71]

Figure

9: Overview of four scenarios from the EPO’s “Scenarios

for the Future”[71]

In sum, our systematic literature review reveals that the present thinking on the future of intellectual property involves one or more of four distinct characteristics. First, the future is rarely the primary focus of IP scholarship and is often ancillary to another analysis. Second, the future is often addressed in the context of discrete events or singular incidents. Third, while scholars and practitioners often consider what will affect or drive the future of IP, they rarely look at the effect of forces outside IP on IP. Fourth, an emerging group of work creates stories, or scenarios, as a means of understanding different alternate futures and the factors that will create them. These results provide a useful building block upon which further qualitative research can be conducted. For example, future work may consider exploring if there are any future scenarios that tend to reappear among various studies, or what percentage of foresight research at large considers IP issues.

Identification of these characteristics helped to shape the scenario-building work of the Open AIR network, referenced above, between 2011 and 2014. Having completed this literature review and analysis while in the early and middle stages of that project’s scenarios exercise, Open AIR researchers took special care to avoid common problems and adopt best practices in respect of future-focused IP research. Consequently, the Open AIR network produced three distinct and challenging but equally plausible scenarios for the future of knowledge and innovation systems—including but not limited to IP law—on the African continent. One of these scenarios envisions a world of “Wireless Engagement”, which is a world where African enterprise is interconnected with the global service-oriented economy, young business leaders form a vocal middle class, and citizens hold governments accountable. In contrast, in Open AIR’s scenario of “Informal – the New Normal”, dynamic informalities cross every aspect of African societies, and ideas constantly recombine within communities built upon interpersonal trust, triggering innovations adapted to relentless change. And finally, in the third scenario of “Sincerely Africa”, African communities ensure sustainability by reinterpreting traditional knowledge systems, and tapping human and natural resource riches in response to global instabilities and external pressures. Any of these three scenarios could result from unpredictable interactions among a number of key drivers of change: global relationships, statehood and governance, identities and differences, infrastructure and technology, and employment and livelihoods. Facilitated in part by the insights generated through this literature review, these drivers of change and future scenarios are juxtaposed against one another and the backdrop of the continent’s rich historical legacies in Knowledge and Innovation in Africa: Scenarios for the Future.[72] This is the sort of methodical forward looking research we hope other scholars might consider engaging in vis-à-vis other IP-related issues.

5. Discussion

Our analysis reveals that the characteristics of the literature on the future of IP may be interpreted as recognising two distinct ways of thinking about the future.

The first three clusters of scholarship, when taken together, are indicative of a linear way of thinking about the future. By failing to consider the future of intellectual property in its own right, the body of literature on the future of IP remains restricted and underdeveloped. Further, this insular way of thinking about the future, results in a piecemeal view of the future, which explores discrete pockets of IP systems and rights but lacks an overarching understanding of the different forces that may drive future change. This type of future thinking reinforces, rather than challenges, current thinking and assumptions, and draws out consequences in a limited way.

In contrast, the type of thinking represented by scenarios, which discuss the future as provocatively uncertain, does the opposite. These works suggest multiple potential futures and overtly avoid making predictions. Instead, these works challenge our assumptions about how certain trends and factors might unfold and how different futures may materialise. Accordingly, these works can take a contextual and high-level view to areas within IP or IP as a whole, using scenarios as a basis for their discussion.

While scenarios can be understood as simply being stories about the future, scenarios are also explained as a tool to engage in the practise of foresight. Foresight is essentially a research method, which can be described as a process that systematically looks into the long-term future.[73]

Despite the increasing popularity of foresight, there is no consensus on the best way to practise it. Originally, the private sector was the primary user of foresight methods for corporate strategic planning purposes. Accordingly, information regarding how foresight was conducted was confidential and inaccessible.[74] However, now a wider range of stakeholders, such as governments and researchers use foresight. It has become mainstream.

For instance, Al Gore’s book, The Future: Six Drivers of Global Change, uses foresight terminology and methods by identifying what he considers the six factors that will drive the world’s future.[75] Gore’s contribution to foresight joins other popularised authors, scholars and foresight practitioners in working towards a deeper understanding of the future, and attempting to distil the driving forces that will shape it. Other authors working on IP or closely related topics have also begun to mainstream future-focused analyses. The best examples are Steven Johnson’s recent book, Future Perfect,[76] which explores the principles underpinning the open design of the Internet and their impact on the future, and Lawrence Lessig’s widely cited book, The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World, also about the future of openness following the Internet revolution.[77]As the use of foresight-related language and concepts become more widespread, more information on what foresight is, and how to practise it, is publicly available.

Our review suggests that the current thinking on the future of intellectual property remains limited. A great deal of the current literature on the future of IP considers discrete areas of IP in isolation, and does so in a narrow and linear way. This results in a disjointed body of literature on the future of IP that does not adequately engage with other disciplines and areas of practice that may have a real impact on the future of IP.[78] However, the use of scenarios in intellectual property scholarship and research can challenge readers in a way that may change our current behaviour, and perhaps allow us to shape the future of IP in a preferable way.[79]

6. Recommendations

This literature review has sought to illuminate the ways in which people think about the future of intellectual property. As we begin to explore current thinking on the future of IP, we can begin to recognise its limitations and obstacles.

In the last fifteen years, there has been an emerging trend to think about the future in a systematic way using scenarios, that is, stories and narratives about the possible future.[80] This approach to futures thinking displays a high degree of sophistication, as these works consider issues within IP in a broader framework, and take a contextual and higher-level approach to factors that may drive future change.

We recommend that IP scholars explore the viability of using scenarios methods in their research, or, at minimum, increase their awareness of the limitations of the predominant modes of addressing “the future” in existing scholarship. Not only is a scenarios-based approach to exploring the future likely to provide more useful scholarly and practical insights, but also, by challenging assumptions about current thinking by providing dynamic conceptions of more than one possible future, foresight methods have the potential to change current behaviour.[81]

Implementing a foresight initiative to conduct scenarios work can present some logistical challenges. For example, where scenarios are created collaboratively with extensive expert consultation, this type of research may be more expensive and time consuming than legal research methods such as desk research and normative commentary. However, this need not be the case. Although scenarios work is sometimes done in workshops or collaboratively over long periods of time, as was the case in de Beer and Bannerman and the EPO’s scenarios, it can also be done by a single researcher or using desk research, as evidenced by the work of Halbert and Gollins, Hinze and Wong.

This research method is useful for not only IP researchers and practitioners, but also for policy makers who have the power to shape intellectual property policies and practices in a way that can transform economies and drive human development. Incidentally, futures scholars and practitioners have begun to recognise the value scenarios in legal thinking.[82] Ramirez and Medjad explain that using scenarios may help legislators and policymakers legislate in a more proactive and iterative way.[83]

The future of intellectual property is necessarily uncertain. However, to adequately practise, research, and legislate in the face of this uncertainty, the role of IP scholars ought to be to challenge assumptions and pre-conceptions.[84] Thus, going forward we suggest that traditional ways of thinking about the future of IP be complemented by research that contextualises IP within a broader socio-economic framework and recognises the myriad of possible worlds the future may hold.

7. Appendix A

Below is a breakdown of the searches performed in each of the five academic databases including any alterations made to our standard search parameters.

7.1 Social Science Research Network

The SSRN search box was unable to handle complex Boolean strings. To accommodate this, instead of completing one search, eight independent searches were done recombining the search terms to cover all possible permutations. SSRN’s e-library extends from 1996-present. This database was searched at the highest degree of detail possible, which included searching in articles’ title, abstract, abstract identification and keywords.

7.2 Business Source Complete

The complete Boolean search string was used in this database, and we searched the available time frame, which included from 1950-present. This database allows for search terms to be used in all texts, and this was the level the search was conducted at.

7.3 ScienceDirect

The Boolean search string was used in its entirety for this database. Initially, we searched for our search terms in all text fields. However, this proved logistically unfeasible as 257,076 results were returned. Accordingly, we modified our search and searched within the fields of title, abstract and keywords. This resulted in 849 results, which were all screened for relevancy. The time period available in this database was 1950-present.

7.4 Index to Legal Periodicals and Books, Full Text

This database has texts available from 1981-present. When our search terms were searched in all texts results we received 50,851 hits. As it was logistically unfeasible to review all these results we modified our search for this database. Accordingly, we conducted two searches:

· (“intellectual property” or copyright or patent or trademark) in ABSTRACTS and (foresight or future) in ALL TEXT FIELDS

· (“intellectual property” or copyright or patent or trademark) in ALL TEXT FIELDS and (foresight or future) in ABSTRACTS

This ensured a comprehensive search while returning a feasible amount of search results. These searches yielded 1,494 results, all of which were reviewed for relevancy.

7.5 Legal Source

Similar to the Index to Legal Periodicals and Books, Full Text search, the initial search in all text fields returned an unmanageable amount of returns with 67,826 hits. Other variations of the search that included all text fields returned amounts that were not feasible. The search was then refined to the following:

· ("intellectual property" or copyright or patent or trademark)) in ABSTRACTS and (future or foresight) in TITLE

· ("intellectual property" OR copyright OR patent OR trademark) in TITLE and (future OR foresight) in ABSTRACTS

This search returned 655 results, all of which were reviewed for relevancy.

8. Appendix B

The following are the relevant results of our search.

A

L Akers, “The Future of Patent Information––a User with a View” (2003) 25 World Patent Information 303-312.

H Anawalt, “Internet Distribution of Intellectual Property Protected Works in the United States, in Japan, and in the Future” (2002) 18:2 Santa Clara Computer & High Technology Law Journal 207-234.

R Andewelt, “Recent Revolutionary Changes in Intellectual Property Protection and the Future Prospects” (1986) 50 Albany Law Review 509-521.

K Andrews and J de Beer, “Accounting of Profits to Remedy Biotechnology Patent Infringement” (2009) 47:4 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 619-662.

Anonymous, “The Future of Biosimilar Patent Litigation” (2009) 1 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 257-258.

E Aprill, “The Supreme Court’s Opinions in Bilski and the Future of Tax Strategy Patents” (2010) 113:2 Journal of Taxation 81-93.

I Ayers, “The Future of Global Copyright Protection: Has Copyright Law Gone Too Far?” (2000) 62:1 University of Pittsburgh Law Review 49-86.

B

S Basheer and M Kochupillai, “The ‘Compulsory Licence’ Regime in India: Past, Present and Future” (2005) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1685129.

J Baxter, “Commentary on ‘Fear, Hope, and Longing for the Future of Authorship and Revitalized Public Domain in Global Regimes of Intellectual Property’” (2003) 52:4 DePaul Law Review 1235-1240.

B Beebe, “Fair Use and Legal Futurism” (2013) 25:1 Law & Literature 10-19.

J de Beer and S Bannerman, “Foresight into the Future of WIPO’s Development Agenda” (2010) 1:2 World Intellectual Property Organization Journal 211-231 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1726153.

T Bell, “Pirates in the Family Room: How Performances from Abroad, to U.S. Consumers, Might Evade Copyright Law” (2011) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn/paper=1816726.

A Berschadsky, “RIAA v. Napster {180 F.3d 1072 (9th Cir. 1999): A Window onto the Future of Copyright Law in the Internet Age” (2000) 18:3 John Marshall Journal of Computer & Information Law 755-789.

L Björklund, “Online Patent Information: Perspectives for the Future” (1991) 13:4 World Patent Information 206-208 available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/017221909190194A.

K Black and J Wishart, “Containing the GMO Genie: Cattle Trespass and the Rights and Responsibilities of Biotechnology Owners” 2008:2 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 397-425.

M Bloch, “The Expansion of the Berne Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention to Protect Computer Software and Future Intellectual Property” (1985) 11 Brooklyn Journal of International Law 283-323.

M Bloom, “University and Non-Profit Organization Licensing in the United States: Past, Present and into the Future — Part I” (2011) 31:5 Licensing Journal 1-9.

M Bloom, “University and Non-Profit Organization Licensing in the United States: Past, Present and into the Future — Part II” (2011) 31:6 Licensing Journal 9-16.

E Bock, “Using Public Disclosure as the Vesting Point for Moral Rights under the Visual Artists Rights Act” (2011) 110:1 Michigan Law Review 153-174.

J Boehm, “Copyright Reform for the Digital Era: Protecting the Future of Recorded Music through Compulsory Licensing and Proper Judicial Analysis” (2009) 10:2 Texas Review of Entertainment & Sports Law 169-211.

D Bollier, “Why We Must Talk about the Information Commons” 2004:2 Law Library Journal 267-282.

D Bowman, “Patently Obvious: Intellectual Property Rights and Nanotechnology” (2007) 29 Technology in Society 307-315 available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160791X07000280.

R Bradfield, “Four Scenarios for the Future of the Pharmaceutical Industry” (2009) 21:2 Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 195-212 available at http://resolver.scholarsportal.info/resolve/09537325/v21i0002/195_fsftfotpi.xml.

A Brown, “Illuminating European Trade Marks” (2004) 1:1 SCRIPT-ed 46-57 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1137535.

C Brown, “Business-Method Patents Face Uncertain Future in Europe” (2001) 113 Corporate Legal Times 11-22.

C

M Carolan, “The Problems with Patents: A Less than Optimistic Reading of the Future” (2009) 40:2 Development & Change 361-388 available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01518.x/abstract.

G Chan, “How Patent Law Amendments Will Affect Design Patent Practice” (2009) China Law & Practice 12.

S Chan, “Canadian Copyright Reform—’User Rights’ in the Digital ERA” (2009) 67:2 University of Toronto Faculty of Law Review 233-264.

G Cheliotis et al, “Taking Stock of the Creative Commons Experiment Monitoring the Use of Creative Commons Licenses and Evaluating its Implications for the Future of Creative Commons and for Copyright Law” (2007) TPRC 1-42 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=2102940.

V Chiappetta, “TRIP-ping Over Business Method Patents” (2004) 37:1 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 181-201.

C Chien, “Reforming Software Patents” (2012) 50:2 Houston Law Review 325-390.

D Clonts, “The Federal Circuit Puts the Willfulness Back into Willful Infringement” (2007) 19:12 Intellectual Property & Technology Law Journal 9-13.

H Coble, “Copyright’s Past and its Application to Copyright’s Future” (2000) 47 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 1-11.

J Cohen, “Copyright as Property in the Post-Industrial Economy: A Research Agenda” (2011) 2011:2 Wisconsin Law Review 141-165.

A Colaianni and R Cook-Deegan, “Columbia University’s Axel Patents: Technology Transfer and Implications for the Bayh-Dole Act” (2009) 87:3 Milbank Quarterly 683-715.

N Conley, “The Future of Licensing Music Online: The Role of Collective Rights Organizations and the Effect of Territoriality” (2008) 25 John Marshall Journal of Computer & Information Law 409-485 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1417678.

R Coombe, “Fear, Hope, and Longing for the Future of Authorship and a Revitalized Public Domain in Global Regimes of Intellectual Property” (2003) 52:4 DePaul Law Review 1171-1191.

K Crews, “Copyright Law and Information Policy Planning: Public Rights of Use in the 1990s and Beyond” (1995) 22:2 Journal of Government Information 87-99.

K Crews, “Looking Ahead and Shaping the Future: Provoking Change in Copyright Law” (2001) 49:2 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 549-584 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1773017.

J Cromer-Young, “Review of James Boyle’s the Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind” (2011) 1:2 The IP Law Book Review 50-53 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1866042.

E Crowne-Mohammed and Y Rozenszajn, “DRM Roll Please: Is Digital Rights Management Legislation Unconstitutional in Canada?” (2009) 2009:2 Journal of Information, Law & Technology 1-22.

D

A Datesh, “Storms Brewing In the Cloud: Why Copyright Law Will Have to Adapt to the Future of Web 2.0” (2012) 40:4 AIPLA Quarterly Journal 685-726.

V Dehin, “The Future of Legal Online Music Services in the European Union: A Review of the EU Commission’s Recent Initiatives in Cross-Border Copyright Management” (2010) 32:5 European Intellectual Property Review 220-237.

R Delchin, “Musical Copyright Law: Past, Present and Future of Online Music Distribution” (2004) 22:2 Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal 343-399.

R Denicola, “Some Thoughts on the Dynamics of Federal Trademark Legislation and the Trademark Dilution Act of 1995” (1996) 59 Law & Contemporary Problems 75-92.

C Dennie, “Native American Mascots and Team Names: Throw Away the Key; The Lanham Act is Locked for Future Trademark Challenges” (2005) 15:2 Seton Hall Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law 197-220.

G Dinwoodie, “The WIPO Copyright Treaty: A Transition to the Future of International Copyright Lawmaking?” (2007) 57:4 Case Western Reserve Law Review 751-766.

G Dinwoodie and R Dreyfuss, “The WTO, WIPO, ACTA and More” in A Neofederalist Vision of TRIPS: The Resilience Of The International Intellectual Property Regime (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) 143-203.

G Dolin, “Exclusivity Without Patents: The New Frontier of FDA Regulation for Genetic Materials” (2013) 98:5 Iowa Law Review 1399-1465.

P Drahos, “Securing the Future of Intellectual Property: Intellectual Property Owners and Their Nodally Coordinated Enforcement Pyramid” (2004) 36:1 Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 53-77.

D Dunner, “The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit: Its Critical Role in the Revitalization of U.S. Patent Jurisprudence, Past, Present, and Future” (2010) 43:3 Loyola of Los Angeles International & Comparative Law Review 775-784.

W Dutton et al, Freedom of Connection – Freedom of Expression: The Changing Legal and Regulatory Ecology Shaping the Internet (Paris: UNESCO, 2011).

E

C Edfjäll, “The Future of European Patent Information” (2008) 30 World Patent Information 135-138 available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0172219007001354.

European Patent Office, EPO Scenarios for the Future: Executive Summary (2007) available at http://documents.epo.org/projects/babylon/eponet.nsf/0/DFF138B734D4AF14C12572CA0047CF73/$File/Scenarios_Executive_Summary.pdf.

F

K Fayle, “Sealand Ho! Music Pirates, Data Havens, and the Future of International Copyright Law” (2005) 28:2 Hastings International & Comparative Law Review 247-266.

O Fischman-Afort, “The Evolution of Copyright Law and Inductive Speculations as to its Future” (2012) 19:2 Journal of Intellectual Property Law 231-259.

B Fitzgerald, “Copyright 2010: The Future of Copyright” (2008) 30:2 European Intellectual Property Review 43-49.

P Fowler and A Zalik, “A U.S. Government Perspective Concerning the Agreement on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property: Past, Present and Near Future” (2003) 17:3 St John’s Journal of Legal Commentary 401-415.

A Fox, “The Economics of Expression and the Future of Copyright Law” (1999) 25:1 Ohio Northern University Law Review 5-26.

J Fromer, “The Compatibility of Patent Law and the Internet” (2012) 78:6 Fordham Law Review 2783-2797.

G

D Gangjee, “The Polymorphism of Trademark Dilution in India” (2008) 17 Transnational Law & Contemporary Problems 101-120 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1273711.

S Garland and S Smordin, “The Harvard Mouse Decision and Its Future Implications” (2003) 39 Canadian Business Law Journal 162-180.

J Garon, “Google, Fairness and the Battle of the Books” in The IP Book (Midwest Intellectual Property Institute, 2010), at ch 8 available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1690186.

N Geach, “The Future of Copyright in the Age of Convergence: Is a New Approach Needed for the New Media World?” (2009) 23:1/2 International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 131-142.

P Geller, “Copyright History and the Future: What’s Culture got to do with it?” (2000) 47 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 209-264.

S Ghosh, “Managing the Intellectual Property Sprawl” (2012) Univ of Wisconsin Legal Studies Research Paper Series No 1200 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=2103612.

J Ginsburg, “The Author’s Place in the Future of Copyright” (2009) 45:3 Willamette Law Review 381-394.

M Godinho and V Ferreira, “Analyzing the Evidence of an IPR Take-Off in China and India” (2012) 41 Research Policy 499-511.

R Gomulkiewicz, “Intellectual Property, Innovation, and the Future: Toward a Better Model for Educating Leaders in Intellectual Property Law” (2011) 64 SMU Law Review 1161-1186 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1648990.

O Goodenough, “The Future of Intellectual Property: Broadening the Sense of ‘Ought’” (2002) 24:6 European Intellectual Property Review 291-293.

D Gorski, “The Future of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) Subpoena Power on the Internet in Light of the Verizon Cases” (2005) 24:1 Review of Litigation 149-172.

J Graham, “The Future of Patent Law” (2008) New Zealand Law Journal 363-368.

B Greenberg, “More Than Just a Formality: Instant Authorship and Copyright’s Opt-Out Future in the Digital Age” (2012) 59:4 UCLA Law Review 1028-1074 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1942735.

J Griffin, “The Digital Copyright Exchange: Threats and Opportunities” (2013) 27:1/2 International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 5-17.

H Grosse Ruse-Khan, “Access to Knowledge under the International Copyright Regime, the WIPO Development Agenda and the European Communities’ New External Trade and IP Policy” in E Derclaye (ed), Research Handbook on the Future of EU Copyright (Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc, 2009) 574-612.

H Gutiérrez, “Peering Through the Cloud: The Future of Intellectual Property and Computing” (2011) 20:4 Federal Circuit Bar Journal 589-607.

H

D Halbert, “Intellectual Property Law, Technology, and Our Probable Future” (1996) 52 Technological Forecasting and Social Change 147-160.

D Halbert, “Intellectual Property in the Year 2025” (2001) 49 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 225-258.

D Halbert, “The World Intellectual Property Organization: Past, Present and Future” (2007) 54:2/3 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 253-284.

L Heilprin, “Technology and the Future of the Copyright Principle” 1968:1 American Documentation 6-11.

L Helfer, “Human Rights and Intellectual Property: Conflict or Coexistence?” (2003) 5 Minnesota Intellectual Property Review 47 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=459120.

S Henry, “The First International Challenge to U.S. Copyright Law: What Does the WTO Analysis of 17 U.S.C. § 110(5) Mean to the Future of International Harmonization of Copyright Laws Under the TRIPS Agreement?” (2001) 20:1 Penn State International Law Review 301-327.

E Hess, “Code-Ifying Copyright: An Architectural Solution To Digitally Expanding The First Sale Doctrine” (2013) 81:4 Fordham Law Review 1965-2011.

S Hetcher, “User-Generated Content and the Future of Copyright: Part One-Investiture of Ownership” 2008:4 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 863-892.

S Hetcher, “User-Generated Content and the Future of Copyright: Part Two-Agreements between Users and Mega-Sites” (2008) 24:4 Santa Clara Computer & High Technology Law Journal 829-867.

S Hilgartner, “Intellectual Property and the Politics of Emerging Technology: Inventors, Citizens, and Powers to Shape the Future” (2009) 84:1 Chicago-Kent Law Review 197-224.

L Hill, “The Race to Patent the Genome: Free Riders, Hold Ups, and the Future of Medical Breakthroughs” (2003) 11:2 Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal 221-258.

C Hilti, “The Future European Community Patent System and its Effects on Non-EEC-Member-States” (1990) 18 AIPLA Quarterly Journal 289-331.

A Hoare and R Tarasofsky, “Asking and Telling: Can ‘Disclosure of Origin’ Requirements in Patent Applications Make a Difference?” (2007) 10:2 Journal of World Intellectual Property 149-169.

J Hoboken, “Looking Ahead—Future Issues when Reflecting on the Place of the iConsumer in Consumer Law and Copyright Law” (2008) 31:4 Journal of Consumer Policy 489-496.

T Hoffman, A Kelli and A Värv, “The Abstraction Principle: A Pillar of the Future Estonian Intellectual Property Law?” (2013) 21:3 European Review of Private Law 823-842.

T Holbrook, “The Return of the Supreme Court to Patent Law” 2007:1 Akron Intellectual Property Journal 1-25.

R Hu, “Protecting Intellectual Property in China: A Selective Bibliography and Resource for Research” (2009) 101:4 Law Library Journal 485-515.

M Hugard, “Lost in Transitory Duration: A Look at Cartoon Network v. CSC Holdings, Inc. and Its Implications for Future Copyright Infringement Cases” (2010) 43:4 UC Davis Law Review 1491-1528.

P Hugenholtz, “Copyright in Europe: Twenty Years Ago, Today and What the Future Holds” (2013) 23:2 Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal 503-524.

J Hughes, “Political Economies of Harmonization: Database Protection and Information Patents” (2002) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=318486.

G Hull, “Digital Copyright and the Possibility of Pure Law” (2003) 14:1 Qui Parle available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1019702.

D Hurst, “Conference Report–U.S. & German Bench and Bar Gathering: ‘A New Bridge Across the Atlantic’: The Future of American Patent Litigation” (2013) 14:1 German Law Journal 269-278.

I

K Idzik, “No More Drama? The Past, Present, and Potential Future of Retroactive Transfers of Copyright Ownership” (2007) 18:1 Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law 127-155.

J

P Janicke, “The Future of Patent Law: Institute for Intellectual Property & Information Law Symposium” (2002) 39:3 Houston Law Review 567-568.

M Jansen, “Applying Copyright Theory to Secondary Markets: An Analysis of the Future of 17 U.S.C. § 109(a) Pursuant to Costco Wholesale Corp. V. Omega S.A.” (2011) 28:1 Santa Clara Computer & High Technology Law Journal 143-167.

T Jeffs, “Redefining Boundaries: How Cohesive Technologies Altered Literal and Equivalent Infringement” 2011:3 Brigham Young University Law Review 879-910.

K

A Kaburakis, J Lindholm and R Rodenberg, “British Pubs, Decoder Cards, and the Future of Intellectual Property Licensing after Murphy” (2012) 18:2 Columbia Journal of European Law 307-322.

E Kane, “Patent Ineligibility: Maintaining a Scientific Public Domain” (2006) 80 St John’s Law Review 519-558 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=833564.

D Karshtedt, “The Future of Patents: Bilski and Beyond” (2011) 63:6 Stanford Law Review 1245-1246.

B Kaunelis, “Securing Global Trademark Exceptions: Why the United States Should Negotiate Mandatory Exceptions into Future International Bilateral Agreements” (2010) 85:3 Chicago-Kent Law Review 1147-1170.

L Kazi, “Will We Ever See a Single Patent System Covering the European Union, Let Alone Spanning the Atlantic or Pacific?” (2011) 33:8 European Intellectual Property Review 538-542.

B Keele, “Review of Intellectual Property and Human Development: Current Trends and Future Scenarios” (2011) 39:1 International Journal of Legal Information 98-100.

R Kennedy, “No Three Strikes For Ireland (Yet): EU Copyright Law and Individual Liability in Recent Internet File Sharing Litigation” (2011) 14:11 Journal of Internet Law 15-31.

J Kesan, “Taking Stock and Looking Ahead: The Future of U.S. Patent Law” (2009) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1372382.

S Knowles, “A Patent Attorney’s Perspective on the Future” (2003) 17:2 Emory International Law Review 603-612.

H Krestel, “Patent Information Today and in the Future – A Survey of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Bavaria” (2001) 23 World Patent Information 29-34.

K Kruckeberg, “Copyright ‘Band-Aids’ and the Future of Reform” (2011) 34:4 Seattle University Law Review 1545-1574.

S Kumar, “Border Enforcement of IP Rights Against in Transit Generic Pharmaceuticals: An Analysis of Character and Consistency” (2009) European Intellectual Property Review, Forthcoming available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1383067.

L Kurtz, “Copyright and the Human Condition” (2007) 40:2 UC Davis Law Review 1233-1252.

L

D Ladd, “Securing the Future of Copyright: A Humanist Endeavor” (1985) 9 Columbia-VLA Journal of Law & the Arts 413-420.

C Lanks, “In re Seagate: Effects and Future Development of Willful Patent Infringement” (2009) 111:2 West Virginia Law Review 607-638.

F Lastowka, “Free Access and the Future of Copyright” (2001) 27:2 Rutgers Computer and Technology Law Journal 293-332 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=913989.

M Leaffer, “Life after Eldred: The Supreme Court and the Future of Copyright” (2004) 30:5 William Mitchell Law Review 1597-1616.

R Leal-Arcas, “How Will the EU Approach the BRIC Countries? Future Trade Challenges” (2008) 2:4 Vienna Online Journal of International Constitutional Law 235-271 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1398109.

B Lehman, “Intellectual Property: America’s Competitive Advantage in the 21st Century” (1996) 31:1 The Columbia Journal of World Business 6-16.

M Leistner, “Copyright Law in the EC: Status Quo, Recent Case Law and Policy Perspectives” (2009) 46:3 Common Market Law Review 847-884.

J Leman, “The Future of Unpublished Works in Copyright Law after the Fair Use Amendment” (1993) 18 Journal of Corporation Law 619-651.

D Levin, “The Future of Copyright Infringement: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd.” (2006) 21:1 St John’s Journal of Legal Commentary 271-310.

S Levmore, “The Impending iPrize Revolution in Intellectual Property Law” (2013) 93:1 Boston University Law Review 139-162.

N Linck and K Buchanan, “Patent Protection for Computer-Related Inventions: the Past, the Present, and the Future” (1996) 18 Hastings Communications & Entertainment Law Journal 659-716.

J Lipton, “The Law of Unintended Consequences: The Digital Millennium Copyright Act and Interoperability” (2005) 62:2 Washington & Lee Law Review 487-546.

D Liu, “The Transplant Effect of the Chinese Patent Law” (2006) 5:3 Chinese Journal of International Law 733-752.

M Lopez, “Creating the National Wealth: Authorship, Copyright, and Literacy Contracts” (2012) 88:1 North Dakota Law Review 161-208.

C Lopresro, “Gamestopped: Vernor v. Autodesk and the Future of Resale” (2011) 21:1 Cornell Journal of Law & Public Policy 227-246.

B Luo and S Ghosh, “Protection and Enforcement of Well-Known Mark Rights in China: History, Theory, and Future” (2009) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1326398.

D Lussier, “Beyond Napster: Online Music Distribution and the Future of Copyright” (2001) 10:1 University of Baltimore Intellectual Property Law Journal 25-48.

M

K MacKenzie et al, “Large-Scale Carbon Nanotube Synthesis” (2008) 2:1 Recent Patents on Nanotechnology 25-40.

M Madison, “Rewriting Fair Use and the Future of Copyright Reform” (2005) 23:2 Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal 391-418.

P Maier, “OHIM’s Role in European Trademark Harmonization: Past, Present and Future” (2013) 23:2 Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal 687-729.

L Malic et al, “Current State of Intellectual Property in Microfluidic Nucleic Acid Analysis” (2007) 1:1 Recent Patents on Engineering 71-88.

G Mandel, “The Future of Biotechnology Litigation and Adjudication” (2005) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=706546.

V Marti, “The Use of IP Backed Securitizations under the Spanish Regulation: Perspectives for the Future” (2008) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1138149.

C May, “Bounded Openness: The Future Political Economy of Knowledge Management” (2011) 33:8 European Intellectual Property Review 477-480.

A Mazumdar, “Information, Copyright and the Future” (2007) 29:5 European Intellectual Property Review 180-186.

P McKay, “Culture of the Future: Adapting Copyright Law to Accommodate Fan-Made Derivative Works in the Twenty-First Century” (2012) 24:1 Regent University Law Review 117-146.

C McManis, “Teaching Current Trends and Future Developments in Intellectual Property” (2008) 52:3 St Louis University Law Journal 855-875.

E McMillan-McCartney, “The Future of Copyright Protection and Computer Programs—Beyond Apple v. Franklin {714 F.2d 1240}” (1986) 13 Northern Kentucky Law Review 97-127.

M Meller, “Commentary on the Future including the Need and Possibility of a Global Patent” (2000) 9:4 Federal Circuit Bar Journal 606-613.

P Menell, “Envisioning Copyright Law’s Digital Future” (2003) 46:1/2 New York Law School Law Review 63-199 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=328561.

P Menell, “Forty Years of Wondering in the Wilderness and No Closer to the Promised Land: Bilski’s Superficial Textualism and the Missed Opportunity to Return Patent Law to its Technology Mooring” (2011) 63:6 Stanford Law Review 1289-1314.

R Mercado, “The Use and Abuse of Patent Reexamination: Sham Petitioning Before the USPTO” (2011) 12 Columbia Science & Technology Law Review 92-158.

B Mercurio, “‘Seizing’ Pharmaceuticals in Transit: Analysing the WTO Dispute that Wasn’t” (2012) 61:2 International & Comparative Law Quarterly 389-426.

K Mihara, “Future Revision Policy of Patent Classification” (2012) 94:1 Journal of the Patent & Trademark Office Society 75-91.

L Miller, “Administering Mayo to Patents in Medicine and Biotechnology: Appropriate Dosage or Risk of Toxic Side Effects?” (2013) 64:2 Mercer Law Review 573-589.

K Milunovich, “The Past, Present, and Future of Copyright Protection of Soundalike Recordings” (1999) 81:7 Journal of the Patent & Trademark Office Society 517-543.

L Morea, “The Future of Music in a Digital Age: The Ongoing Conflict between Copyright Law and Peer-to-Peer Technology” (2006) 28:2 Campbell Law Review 195-249.

M Morgan, “Regulation of Innovation under Follow-on Biologics Legislation: FDA Exclusivity as an Efficient Incentive Mechanism” (2010) 11 Columbia Science & Technology Law Review 93-117.

J Mueller, “The Tiger Awakens: The Tumultuous Transformation of India’s Patent System and the Rise of Indian Pharmaceutical Innovation” (2007) 68:3 University of Pittsburgh Law Review 491-641.

N

J Neal, “A Lay Perspective on the Copyright Wars: A Report from the Trenches of the Section 108 Study Group” (2009) 32:2 Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts 193-205.

D Nimmer, “Back from the Future: A Proleptic Review of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act” (2001) 16 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 855-876.

M Noller, “Darkness on the Edge of Town: How Entitlements Theory can Shine a Light on Termination of Transfers in Sound Recordings” (2012) 46:3 Georgia Law Review 763-798.

C Nosko, D Garcia-Swartz and A Layne-Farrar, “Open Source and Proprietary Software: The Search for a Profitable Middle-Ground” (2004) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=673861.

A Nuvolari, “Book Review: Intellectual Property Rights and the Life Science Industries: Past, Present and Future by Graham Dutfield” (2010) 63:4 The Economic History Review 1206-1207.

P

S Perlmutter, “Future Directions in International Copyright” (1998) 16:2-3 Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal 369-382.

S Perlmutter, “Convergence and the Future of Copyright” (2001) 23:2 European Intellectual Property Review 111-117.

A Perzanowski, “Evolving Standards & the Future of DMCA Anticircumvention Rulemaking” (2007) 10:10 Journal of Internet Law 1-22.

E Peters, “Are We Living in a Material World?: An Analysis of the Federal Circuit’s Materiality Standard Under the Patent Doctrine of Inequitable Conduct” (2008) 93:4 Iowa Law Review 1519-1564.

B Pikas, A Pikas and C Lymburner, “The Future of the Music Industry” (2011) 5:3 Journal of Marketing Development & Competitiveness 139-149.

A Pisarevsky, “Cope-ing with the Future: An Examination of the Potential Copyright Liability of Non-Neutral Networks for Infringing Internet Content” (2007) 24:3 Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal 1359-1393.

W Pollack, “Tuning In: The Future of Copyright Protection for Online Music in the Digital Millennium” (2000) 68:6 Fordham Law Review 2445-2488.

F Porcelli, “Future of Business-Method Patents in Question” (2008) 80:54 Buffalo Law Journal 15.

W Potter, “Music Mash-Ups: The Current Australian Copyright Implications, Moral Rights and Fair Dealing in the Remix Era” (2012) 17:2 Deakin Law Review 349-384.

W Price II, “Unblocked Future: Why Gene Patents Won’t Hinder Whole Genome Sequencing and Personalized Medicine” (2012) 33:4 Cardozo Law Review 1601-1631.

E Priest, “The Future of Music and Film Piracy in China” (2006) 21 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 795-871 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=827825.

R

A Rai, J Allison and B Sampat, “University Software Ownership and Litigation: A First Examination” (2009) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=996456.

K Raju, “Is the Future of Software Development in Open Source? Proprietary vs. Open Source Software: A Cross Country Analysis” (2007) 12:2 Journal of Intellectual Property Rights 199-211 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=985237.

C Rappi, “The Past, Present, and Future of Offer-to-Sell Infringement Jurisprudence and Damages” (2011) 22:4 Intellectual Property Litigation 1-19.

J Reichman, “Intellectual Property in the Twenty-First Century: Will the Developing Countries Lead or Follow?” (2009) 46:4 Houston Law Review 1115-1185 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1589528.

R Reis, “Progress, Innovation and Technology: A Delicate ‘Google’ Balance” (2012) Buffalo Intellectual Property Law Journal, Forthcoming available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1879417.

R Reis, “Smoke and Mirrors: America Invents Act 2011: A Chill in the Air” (2012) 6:2 Akron Intellectual Property Journal 301-335.

J Reiss, “Commercializing Human Rights: Trademarks in Europe After Anheuser-Busch v Portugal” (2011) 14:2 Journal of World Intellectual Property 176-201.

J Rekola, “An Electronic Future in the Finnish Patent Office” (2000) 22 World Patent Information 329-332.

M Risch, “Forward to the Past” (2010) Cato Supreme Court Review 333-368 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1678163.

L Ritchie de Larena, “License to Sue?” (2007) SSRN Electronic Journal available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1018715.

E Rogers, “Ten Years of Inter Partes Patent Reexamination Appeals: An Empirical View” (2013) 29:2 Santa Clara Computer & High Technology Law Journal 305-368.

J Rothman, “Initial Interest Confusion: Standing at the Crossroads of Trademark Law” (2005) 27 Cardozo Law Review 105-191 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=691543.

E Ruzich, “In re Bilski and the Future of Business Method and Software Patents” (2009) 50:1 Idea 103-120.

A Ryan, “Contract, Copyright, and the Future of Digital Preservation” (2004) 10:1 Boston University Journal of Science & Technology Law 152-176.

S

P Samuelson and J Schultz, “‘Clues’ for Determining Whether Business and Service Innovations are Unpatentable Abstract Ideas” (2011) 15:1 Lewis & Clark Law Review 109-131.

A Sawkar, “Are Storylines Patentable?” 2008:6 Fordham Law Review 3001-3063.

R Sawyer, “Creativity, Innovation, and Obviousness” (2008) 12:2 Lewis & Clark Law Review 461-487.

G Scanlan, “The Future of Design Right: Putting s 51 Copyright Designs & Patents Act 1988 in its Place” (2005) 26:3 Statute Law Review 146-160.

N Schaumann, “Copyright, Containers, and the Court: A Reply to Professor Leaffer” (2004) 30:5 William Mitchell Law Review 1617-1631.

C Schultz II and B Saporito, “Protecting Intellectual Property: Strategies and Recommendations to Deter Counterfeiting and Brand Piracy in Global Markets” (1996) 31:1 The Columbia Journal of World Business 18-28.

M Schultz, “Live Performance, Copyright, and the Future of the Music Business” (2009) 43:2 University of Richmond Law Review 685-764.

S Schwemer, “Food for Thought – Revisiting the Rationale of Law-Based Food Origin Protection” (2012) 7:3 European Food & Feed Law Review 1341-1342.

S Seymore, “The Null Patent” (2012) 53:6 William & Mary Law Review 2041-2105.

E Shinneman, “Owning Global Knowledge: The Rise of Open Innovation and the Future of Patent Law” (2010) 35:3 Brooklyn Journal of International Law 935-964.

B Silver, “Controlling Patent Trolling with Civil RICO” (2009) 11 Yale Journal of Law & Technology 70-95.

Z Slováková, “International Private Law Issues regarding Trademark Protection and the Internet within the EU” (2008) 3:1 Journal of International Commercial Law & Technology 76-83.

B Smith, “Technology and Intellectual Property: Out of Sync or Hope for the Future?” (2013) 23:2 Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal 619-643.

L Solum, “The Future of Copyright” (2005) 83 Texas Law Review 1137-1171 available at http://ssrn.com/paper=698306.

C Suarez, “Look Before you ‘Lock’: Standards, Tipping, and the Future of Patent Misuse After Princo” (2011) 13 Columbia Science & Technology Law Review 371-415.

G Swank, “Extending the Copyright Act Abroad: The Need for Courts to Reevaluate the Predicate-Act Doctrine” (2012) 23:1 Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law 237-263.

T