The Networked Electorate: The Internet and the Quiet Democratic Revolution in Malaysia and Singapore

Tang Hang Wu*

Assistant Professor

Law School

National University of Singapore

lawthw@nus.edu.sg

Abstract

This paper is intended to be a contribution to the literature on claims of the democratising effect of the Internet. The paper begins by setting out the arguments and also critiques of claims of the democratising power of the Internet. In order to test the validity of these arguments, the author will undertake a comparative study of the impact of the Internet on recent general elections in Malaysia and Singapore. The study will demonstrate that in the case of Singapore, the Internet has merely exerted some pressure on the pre-existing laws and state-imposed norms governing free speech; in contrast, in Malaysia, the Internet was a major contributory factor to what has been described as a ‘political tsunami’ during the recent general election. In this comparative study, the author will attempt to explain why the impact of the Internet has been so different in both jurisdictions which share similar laws, culture and language. It will be suggested that, in spite of their similarities, the main reasons for this phenomenon are subtle but important differences in terms of legal, social, economic conditions and also the political climate in both jurisdictions. Despite this difference, the claim made in this paper is that the Internet, due to its evolving architecture, is beginning to generate important norms governing free expression which are capable of having an effect on the electorate. In both countries, the Internet connects individuals to become networks which in turn create powerful echo chambers which have or will ultimately strain the effectiveness of pre-existing laws and state-imposed norms governing free speech. It is also suggested that the recent events in Malaysia has inspired nascent Internet activism in Singapore which potentially may be of greater influence in future elections.

This a Refereed Article published on 18 September 2009.

Citation: Tang, H. W., ‘The Networked Electorate: The Internet and the Quiet Democratic Revolution in Malaysia and Singapore’, 2009(2) Journal of Information, Law & Technology (JILT), <http://go.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/2009_2/tang>

Keywords

e-Democracy; free speech; Internet speech; active dot matrix; networked electorate; powerful echo chambers; Malaysia; Singapore.

1. Introduction

The flow of information to the electorate has traditionally depended mainly on newspapers, television and radio. Obviously, this state of affairs precludes the average man or woman on the street from reaching to the masses because of barriers of entry in terms of costs and access to these channels of communication. In countries where there is limited press freedom, this dependence on traditional media prevents opposition politicians from effectively campaigning and spreading their message to the electorate. The Internet presents a reversal of this old paradigm – with the advent of Web 2.0, it is theoretically possible for the average person with a message to communicate with the electorate at large. Therefore, it is unsurprising that many people are excited with the possibility of the democratising effect of the Internet. This paper is an exploration of this possibility from the perspective of two jurisdictions – Singapore and Malaysia. These countries are selected as comparative case studies because they share very similar laws, culture and language and recently held general elections – Singapore in 2006 and Malaysia in 2008.1 And yet, the effect of the Internet on the electorate in these two countries has been markedly different. In spite of these apparent similarities, in the case of Singapore, the Internet merely exerted some pressure on the pre-existing laws and state-imposed norms governing free speech; in contrast, in Malaysia, the Internet was a major contribution to what has been described as a ‘political tsunami’ during the recent general election. This paper will attempt to explain the reasons for this divergence. Despite this divergence, I will argue that both jurisdictions share a particular commonality – the presence of active Internet communities among the electorate has generated norms with regard to free speech that are incompatible with pre-existing norms that exist off-line. These Internet speech norms have the tendency of spilling out of cyberspace and making off-line speech norms less stable. In the case of Malaysia, the spillover effect of these norms, for reasons which will be explored below, is greater than what has happened in Singapore. In Malaysia, these speech norms coupled with the effective use of the Internet as a campaigning platform rendered the Internet as one of the contributing factors in swaying the electorate to vote in a particular manner. It is also contended that the existence of social and political weblogs or blogs in these jurisdictions presents unique opportunities for the creation of new social spaces where free speech thrives. This paper attempts to present a rough snap shot of these newly created social spaces.

2. The Theoretical Framework of this Paper: Of Dots and Active Dot Matrix

I begin this paper by examining the theoretical framework of the various forms of restraints operating on an individual’s behavior. The individual, as Lawrence Lessig has famously argued, may be conceptualised as a (pathetic) dot (Lessig, 2006, pp. 122-123). As lawyers, we often only think of the law as the primary regulator of human behaviour. However, Lessig alerts us of four forces which restrain the behaviour of the dot. Quite apart from law, these restraints include social norms, architecture and market forces. The dot and these four restraints are represented in the figure below:

Figure 1: A Dot's Life (Lessig, 2006, p. 123).

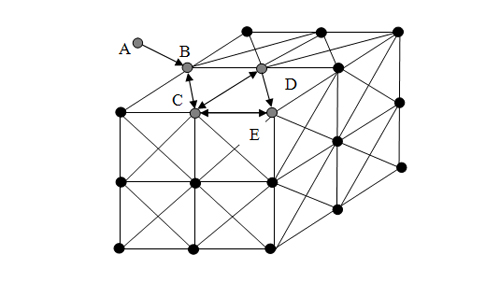

Lessig’s insight on architecture impacting on the dot’s behaviour is an insightful and important observation. For the purposes of this paper, the architecture of the Internet is significant. The heavily hyperlinked architecture of the Internet (especially weblogs or blogs) connects individuals with one another. Thus, the individual is not, as Lessig conceptualises, a lonely and pathetic dot existing in isolation in the context of Web 2.0. Rather, a more accurate representation of the dot in this context is Andrew Murray’s active dot matrix which is represented in the figure below. In analysing digital speech, we should realise that individuals are linked together in a complex matrix. The active dot matrix is not merely a descriptive phenomenon; the contention of this paper is that this matrix is capable of influencing speech norms. In this paper, I make the following claims. First, as more and more individuals are plugged into the active dot matrix, the Internet is increasingly becoming a powerful alternative to the main stream media in terms of news dissemination. This point is extremely significant especially in jurisdictions where press freedom is not guaranteed. In Singapore and Malaysia, I shall demonstrate how the Internet has subverted the agenda and tone of certain issues in the national political discourse and undermined strict campaigning laws during the election period. Second, the active dot matrix is also important because it may generate internal norms which may be incompatible with off-line laws and norms. The principal focus of this essay is to study Internet speech norms and to investigate how these norms make the effectiveness of laws and norms existing off-line less stable. A related point is the issue of the dynamics in group decision making. A hypothesis mooted in this paper is that the results of the Malaysian elections may be partly explained as a form of cascade and polarisation of opinion by reason of the active dot matrix. Third, the active dot matrix forms what I christen as ‘ powerful echo chambers’. While the term ‘echo chamber’ has distinctively insular and pejorative connotations, powerful echo chambers makes the concerns of members of active dot matrix louder and impossible to ignore by the mainstream press. Finally, the active dot matrix has the potential to tag certain politicians with ‘digital scarlet letters’. This would have a moderating impact on the tone of the political discourse and the behaviour of some politicians.

Figure 2: Murray’s ‘Active Dot’ Matrix (Murray, 2008, p. 301)

Nevertheless, it would be naïve to believe that the Internet is not susceptible to regulation. As I will demonstrate in this paper, the Malaysian and Singapore governments and some corporations have taken some action against Internet activists. Regulation on any particular dot within the matrix would have repercussions on the entire active dot matrix. This is represented by Murray in the figure below. Thus, while the networked electorate does wield some power by reason of its interconnectedness, this power of the networks is extremely fragile. It is susceptible to destruction by stringent government regulations or private law action such as defamation.

Figure 3: Regulatory Impact (Murray, 2008, p. 304)

3. The Internet and its Effect on Electorate

The argument that the Internet has a democratising effect on the electorate is not a new one. There are several points embedded in this claim. First, in most jurisdictions, the regulatory regime affecting the Internet is usually less stringent than those affecting newspapers, radio and television. This is not because governments do not wish to control the Internet but there are practical and political difficulties to regulating the Internet. On one level, an overzealous regulatory control of the Internet may, to a certain extent, impede trade. A government who obsessively censors the Internet would have an unfavorable reputation among international investors. Of course, if the regime is not too concerned with the views of the international community, it can attempt to control the Internet and block out certain websites. While this option may be open to a country like China (Reporters Sans Frontieres, 2007), which remains an attractive proposition to investors despite its human rights record, or Burma (Reporters Sans Frontieres, 2008), which does not seem to care about the opinion of the international community, most countries are wary of driving away potential international investors. Control of the Internet also poses immense practical problems. Since the Internet is so vast, any form of effective control would be extremely labor intensive and costly. Furthermore, various techniques such as the setting up of anonymous websites, hosting the websites overseas, using overseas websites such as Youtube or Blogger, putting up mirror sites etc may route around some of the attempts to control the Internet.

Apart from routing around restrictive legal controls, the Internet has lowered the barriers to entry for access to mass communication. With the ubiquity and popularity of social and political blogs and video sharing websites such as Youtube, a person may write and broadcast content which may potentially reach the electorate with access to the Internet. All this may be done without incurring too much cost. Therefore, the barriers to entry in the Internet era are not the regulatory regime or prohibitive costs; rather it is the practical problem of finding and keeping an interested audience (Drezner, 2008, p. 181). In particular, blogs have emerged as a powerful medium in many countries as an effective means of connecting with the electorate (See, e.g., Coleman, 2005; Jackson, 2008; Ferguson and Griffiths, 2006). The architecture of the blog – the possibility of hyper linking it to other blogs and websites and the comments section for readers – has made it an ideal medium for political punditry, dissemination of information and encouraging a dynamic interaction between the blogger and his or her readers. The interactive nature of the blog can be seen as creating new social spaces where the electorate may participate in the deliberative process and as a means of aggregating the collective knowledge of the electorate in considering the pressing issues of the day. It is therefore unsurprising that many political parties all over the world have used blogs as a medium to reach out to the electorate.

Despite the claim that the Internet has had a dramatic democratisation effect among the electorate, there has been some pessimism raised about the extent of this effect. Some of these principal concerns about the limited effect of the Internet will be discussed below.

3.1 The Problem of the Daily Me

Cass Sunstein eloquently describes the problem of the Daily Me in Republic.com (Sunstein, 2002, pp. 3-22). Sunstein warns that the Internet may fragment public discourse into party lines and make the electorate more insular. Prima facie, this seems like a counter-intuitive argument - wouldn’t the Internet expose the electorate to more information and disparate points of views? Sunstein argues that the opposite might be true. People may just log on to the Internet and read things that reflect their pre-existing opinion. In order to describe this phenomenon, Sunstein uses the metaphor of the echo chamber – Internet users will seek out others who echo their pre-existing views. As such, the information on the Internet will only serve to reinforce a person’s preconceived beliefs. According to this theory, the Internet, far from serving as a forum for balanced public discourse, could degenerate into a series of polarised echo chambers. In the context of a multi-ethnic electorate like Singapore and Malaysia, this observation may be particularly apposite. Quite apart, from discourse on the Internet being polarised on ideological grounds, there is also the possibility of fragmentation according to language and racial lines. For example, it is quite likely that the views expressed on the Malaysian English language blogosphere are very different from that prevalent in the Malay language blogosphere.2

3.2 Digital Divide

Another commonly mentioned limitation of the Internet is the existence of the digital divide between those who have the skills and financial resources to have access to the Internet and those who do not (Norris, 2001, pp. 3-26). The presence of the digital divide means that the content of the Internet will only reach those who are well-off and technologically savvy. Therefore, a commonly made argument is that since the degree of Internet penetration is usually relatively low in developing countries especially with the older demographic of the electorate who may not be technologically proficient, the democratisation effect of the Internet is largely overstated.

3.3 Laws May Curtail the Content of the Internet

The initial euphoria among libertarians about the Internet not being subject to legal control has given way to some realism that laws may curtail Internet activism. Website owners, blog writers and various content providers live in the real world and they are subject to the laws of the jurisdiction where they are based. While it is a theoretical possibility of maintaining a completely anonymous website or blog, most prominent political commentators disclose their identity. It is surmised that this is because a political commentator or activist garners more credibility in the public sphere if their identity is known rather than being an anonymous voice on the Internet. Once the identity of the website owner or blogger is disclosed, this immediately subjects the person to the local laws where they are based.

3.4 Most Content on the Internet Are Puerile, Inane or Simply Inaccurate

While some Internet websites have very good content, the fact is, most popular websites are either very puerile or inane.3 Websites featuring pornography and sex scandals remain the perennial top websites and searches on the Internet. Apart from pornography, there is also a huge appetite for puerile content on the web such as gossip on celebrities, fashion etc. Also, a lot of the content on the Internet is simply wrong. Wild conspiracy theories about various celebrities and politicians flourish on the Internet. Thus, it may very well be that the Internet’s power to educate and enlighten the electorate is exaggerated.

4. An Overview of the Recent General Election in Singapore and Malaysia

The contrast between the fortunes of the ruling party in the general election between Singapore and Malaysia is very stark. In the general election in 2006, Singapore’s ruling party, the People’s Action Party (‘PAP’), returned with a comfortable majority of 66.6 % of the overall votes and dropped only 2 seats out of 84 to the opposition (The Strait Times (Singapore), May 8, 2008). In comparison, the ruling coalition in Malaysia, Barisan Nasional, lost its 2/3 majority in the Parliament in the 2008 general election winning 140 out of the 222 seats (New Strait Times, Mar 10, 2008; The Wall St. Journal, Mar 10, 2008). By way of background, the Barisan Nasional is a multi-racial coalition, of which the main players are the United Malay National Organisation, Malaysian Indian Congress and the Malaysian Chinese Association. The 2/3 majority represents a crucial figure because this is the majority that is needed to amend the Constitution.4 The 2008 general election was the worst ever showing by the Barisan Nasional since 1969.5 It is instructive to compare the results of the Malaysian general election in 20046 and 2008. In the 2004 election, Barisan Nasional obtained an enviable 198 out of 219 seats in Parliament. Interesting questions arise when we look at these results. How is the PAP able to maintain such a huge domination over the electorate in Singapore? Has the opposition in Singapore failed to take advantage of the Internet? On the Malaysian side, what is the explanation for the dramatic downward shift in terms of votes for Barisan Nasional? Is the Internet a contributory factor for this shift? The related point is that since there was already the presence of a strong Internet activist movement in Malaysia, why did the opposition not fare much better in the 2004 election?

It would seem that a confluence of factors accounted for Barisan Nasional’s poor showing in the 2008 polls. What then are these factors? Due to space constraints, it is beyond the scope of this paper to undertake a comprehensive account of these factors. For the purposes of this paper, it is sufficient merely to outline the main factors. The 2004 Malaysian general election was unique in the sense that there was a change of the Prime Minister after 22 years. Recall that the general election was called 5 months after the transition between the long serving Prime Minister, Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, who stepped down in favor of Abdullah Badawi (Liow, 2005). In contrast to Dr. Mahathir’s feisty and combative style of leadership which polarised the electorate, the affable and soft-spoken Abdullah Badawi seemed like a breath of fresh air. The general feel-good mood of the electorate for the end of ‘Mahathirism’ after 22 years accounted for some of the success of Barisan Nasional. Second, Abdullah Badawi being a new Prime Minister cleverly appropriated the mantra of change and reform from the opposition. In the 1999 general election, Anwar Ibrahim’s party, Party Keadilan Rakyat, had gained some ground with the campaign message of reform (‘reformasi’). However, this message of reform was adopted by Abdullah Badawi in 2004, and, therefore, Barisan Nasional took the wind out of the sails of the opposition. Abdullah Badawi sold himself as ‘ Mr. Clean’ and a person who was determined to institute structural changes to governance and to crack down on corruption. Barisan Nasional also cleverly neutralised the Islamic party in Malaysia, Parti Islam Se-Malaysia, by promoting a moderate and progressive brand of Islam, Islam Hadhari. It is noteworthy to point out that the terrorist attacks in New York on September 11, 2001 had some of the Muslim and non-Muslim electorate wary of the growing fundamentalist Islamic movement that was taking root in Malaysia. Thus, Islam Hadhari was a perfect compromise to placate those fears. While it does not deny the importance of Islam, it presents a moderate face of Islam (New Straits Times, Mar. 22 2004).

In contrast, the 2008 general election was held at a time when there was a strong feeling of disenchantment with the government among the three major communities in Malaysia. Among the communities, the Indian community’s feeling of disillusionment was especially acute in 2008. One of the major turning points was a much publicised ‘body snatching’ incident. This involved the burial of M. Moorthy who was widely considered a local hero among the Indian community (Malaysiakini, Dec.22 2005). By way of background, Moorthy was an army officer and part of a Malaysian team which climbed Mount Everest. When M. Moorthy tragically died in 2005, the Islamic religious authority applied to the Syariah court for a declaration that he was a Muslim. It was alleged that army records showed Moorthy had converted to Islam before his death. His family disputed this and asserted that Moorthy died a Hindu. Despite protests, the Islamic officials insisted that Moorthy be buried as a Muslim which resulted in Moorthy’s family not attending the funeral (Aziz, 2005). The high handed and oppressive manner in which the officials behaved gave birth to the Hindu Rights Action Force (‘Hindraf”). The second event which galvanised the Hindu community was the demolition of several Hindu temples including the Sri Maha Mariamman Temple (New Straits Times, Singapore, Nov.7, 2007). All this anger culminated in a bizarre rally organised by Hindraf to collect signatures to petition Queen Elizabeth II and to file a class action suit against the British government for bringing Indians to Malaysia as indentured servants (New Straits Times, Nov.22, 2007). Although the stated goals of the rally were rather odd, it attracted a huge turnout. It was reported that between 5,000 – 20,000 people turned up at the rally.7 In response, the riot police used teargas and water cannons to break up the protesting crowds. Scenes of the riot police battling the crowd further angered the Indian community. Subsequently, Hindraf leaders were arrested without trial under the Internal Security Act. These incidents left the Indian community with the feeling that their interests were not protected by Barisan Nasional’s Malaysian Indian Congress (‘MIC’). It was unsurprising that in the subsequent polls most of the top MIC politicians lost their seats (Anand, 2008).

In the 2008 election, the Chinese community also deserted Barisan Nasional’s Malaysian Chinese Association (‘MCA’) because there was a feeling that the party was impotent when it came to protecting the community’s interest (New Sunday Times, Mar.9, 2008). The high water mark must have been the 2006 United Malay National Organization (‘UMNO’) general assembly where very inflammatory rhetoric was heard. One UMNO delegate was reported to have said: ‘Umno is willing to risk lives and bathe in blood to defend the race and religion. Don't play with fire. If they mess with our rights, we will mess with theirs’ (Ahmad, 2006). The Education Minister, Hishamuddin Hussein, unsheathed, kissed and raised a Malay sword, the keris, and said: ‘This is a warning from the youth movement’. To make matters worse, the entire event was broadcast live (Ahmad, 2006) on cable television to the horrified non-Malay electorate (Lau, 2006). Unrepentant, Hishamuddin again waved the keris in the 2007 UMNO general assembly (Hong, 2007). Other important factors which contributed to Barisan Nasional’s poor showing included: (a) Dr. Mahathir’< s constant attacks on Abdullah Badawi;8 (b) the alarming rise of crime rate in Malaysia (Ong, 2008); (c) rising cost of living (Hong, 2008); (d) the trial of a research analyst with rumoured links to the government for allegedly murdering his Mongolian mistress; and (e) alleged corruption in the highest level among members of the Malaysian judiciary and the police force (Ming, 2008). All these events left the electorate with the impression that all major institutions of the government were crumbling and Abdullah Badawi was a weak and ineffectual leader.

A few observations seem to be striking in this cursory overview of the general elections in both countries. First, the degree of Internet penetration among the electorate does not inevitably guarantee success for the opposition. Singapore has a higher percentage of Internet penetration than Malaysia (George, 2005). And yet, the PAP has been extremely successful in dominating the political space in the country. Another important qualification is that the strength of civil society in a particular country appears to be more important than the degree of Internet penetration. This is shown by comparing Internet activism in Singapore with that in Malaysia. The former has higher Internet penetration and a relatively weaker civil society activism than the latter. As such, in Singapore Internet activism is correspondingly less vibrant than Malaysia. Also, as will be demonstrated below, in the case of Singapore, a strategic use of legislation may prevent the Internet from being used as an effective means of campaigning and raising funds during the general election. Another important observation is that even if there is the presence of strong Internet activism, the effect of the Internet is merely one factor which may sway the electorate. In Malaysia, there was a combination of many adverse factors which contributed to the decline of the fortunes of Barisan Nasional. However, it would be a mistake to conclude that the Internet had no effect on the electorate in the 2006 general election in Singapore. As I will demonstrate below, the Internet played an important role in news dissemination, subverting the message of the ruling party and routing around some of the legal restraints to free speech and campaigning in Singapore.

5. Free Speech in Singapore and Malaysia: Legal Restraint

In Singapore and Malaysia, the right to freedom of speech is enshrined in the Constitution.9 Nevertheless, free speech in Singapore and Malaysia is subject to several types of legal fetters.The right to free speech in both countries is expressly subject to laws that Parliament may enact.

More specifically, there are a multitude of laws in both jurisdictions which have the effect of regulating speech (especially political speech). A non-exhaustive list is as follows: (i) Sedition Law: Both countries have sedition law10 which makes it an offence to say or publish words which have a seditious tendency. The offence is defined widely to include words designed to: (a) bring hatred or contempt or exciting disaffection against the government; (b) exciting the alteration other than by lawful means of any matter by law established; (c) bringing into hatred or contempt or excite disaffection against the administration of justice; (d) raise discontent or disaffection among the residents or citizens; and (e) promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between races or classes of the population. (ii) Defamation: Singapore’s politicians have never been reserved in using defamation laws against their political opponents when they feel they have been defamed (Thio, 2006, pp. 167-168; Hang, 2008a, pp. 452-462; Hang, 2008b, p. 876). In Malaysia, there has also been a worrying trend of defamation suits against reporters asking for astronomical damages (Logan, 2001). (iii) Contempt of Court and Contempt of Parliament: In Singapore and Malaysia, there are stringent laws against speech that can be construed as a contempt of court11 and/or contempt of parliament.12 (iv) Internal Security Act:13 Both countries have the Internal Security Act which allows the government to detain a person without trial; and (v) Official Secrets Act:14 Communication of materials which are construed as an official secret is punishable by either a fine or imprisonment. In Malaysia and Singapore, newspapers15 are required to obtain a licence from the government.16 The government’s discretion not to issue a licence is not subject to judicial review.

In addition to these laws, there are additional laws in Singapore such as: (a) Public Entertainments and Meetings Act:17 All forms of public entertainment including any lecture, talk, address, debate or discussion can only take place in an approved place and in accordance with a licence granted by the relevant Licensing Officer; (b) Penal Code:18 The Penal Code in Singapore has been amended to expand its reach to the Internet for the following offences committed via the electronic medium, such as section 292 (sale of obscene books), section 298 (uttering words with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person), section 499 (defamation) and section 505 (statements conducing to public mischief) (Lum, 2006); and (c) Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act19: Pursuant to section 9 (read with section 8) of this Act, the government may grant a restraining order against persons who are inciting or instigating any religious group or institution to: cause feelings of enmity, hatred, ill-will or hostility between different religious groups, carry out activities to promote a political cause, or a cause of any political party while, or under the guise of, propagating or practising any religious belief, carry out subversive activities under the guise of propagating or practising any religious belief, or excite disaffection against the President or the Government while, or under the guise of, propagating or practising any religious belief.

All the laws described above can (and in some cases have been) be applied to digital speech.

6. Limiting the Effect of the Internet on Politics: The Case of Singapore (Thio, 2008)

Apart from the similarities mentioned above, there are specific statutes in Singapore that have the potential to restrict digital speech. Singapore’s Parliamentary Election Act,20 the Broadcasting Act21 and the Films Act22 deserve a fuller analysis as there are provisions in these specific Acts which impact directly on the Internet. It is surmised that the presence of these specific rules has to do with the less vibrant Internet landscape in Singapore as compared to Malaysia.

For example, there is some form of legal control over political blogs and putting up political podcasts on the Internet during the 2006 general election.23 These rules appear to be derived from a patchwork of legislation and Ministerial statements. Two main statutes are often cited as providing the framework regulating political blogs and political podcasts – the Parliamentary Election Act24 and the Broadcasting Act.25 Section 78A of the Parliamentary Election Act26 provides that the relevant Government Minister may make regulations governing election advertising which includes regulating not just political parties, the candidates and their agents but also relevant persons. A ‘relevant person’ is in turn defined as someone who ‘provides any programme’ on the Internet and is required to obtain a class licence and register with the Media Development Authority of Singapore (‘MDA’) on the account that he or she engages in or provides any programme for the ‘propagation, promotion or discussion of political issues relating to Singapore.’ The class licence refers to requirements imposed by the Broadcasting Act.27 Section 9 of the Broadcasting Act stipulates that MDA may determine certain provisions of broadcasting services as requiring a class licence. The term ‘broadcasting services’ is defined so widely that it could technically include a blog owner or a person putting up a podcast on the Internet. The Broadcasting (Class Licence) Notification28 mandates that an ‘ Internet service provider’ must apply for a class licence from the MDA. The terms ‘Internet service provider’ is defined as a person who provides ‘any programme, for business, political or religious purposes…on the Internet’. Section 6 of the Broadcasting Act also provides that the MDA is empowered to issue a code of practice with regard to broadcast standards maintained by licensees. An Internet Code of Practice was re-issued with effect on November 1, 1997 (Samtani, 2001).

The effect of this confusing array of legislation and subsidiary legislation on new Internet technologies was clarified shortly before the elections by the Senior Minister of State, Dr. Balaji Sadasivan (The Straits Times, Singapore, Apr.4, 2006) who suggested that: (a) podcasts featuring ‘explicit political content’ were prohibited; and (b) bloggers who consistently espouse a political line would have to register their sites with the MDA. With regard to the latter, Dr. Balaji was quoted as saying bloggers who ‘persistently propagate, promote or circulate political issues relating to Singapore’ must register with the MDA (Ibid). He added ‘[d]uring the election period, these registered persons will not be permitted to provide material online that constitutes election advertising’ (Id).

Another significant legislation affecting free speech on the Internet is the Films Act. 29 The rationale for this legislation is the view that political films were not beneficial to the country’s political process because it would reduce the seriousness of political debate and transform domestic politics into a mere advertising competition.30 Section 33 of the Films Act renders it an offence for anyone to import, make, distribute, or exhibit a party political film. A person breaching this provision is liable to imprisonment of up to two years and/or a maximum fine of S$ 100,000.31 A ‘party political film’ is defined as one directed towards a ‘political end’ in Singapore.32 As to what constitutes a ‘political end’ this includes anything which is likely to affect voting in any election or partisan references/comments on any of the following matters: (a) the election; (b) the candidates; (c) national issues and policies; (d) the Government; (e) the opposition to the Government; or a Member of Parliament. Critics of this new enactment have pointed out that this definition of ‘political end’ is unduly wide.33 Unsurprisingly, this broad characterization of what is a political film has proved to be problematic. A documentary, Visions of Persistence, made by some polytechnic lecturers about the veteran opposition member, the late J.B. Jeyeratnam, caused much controversy when it was submitted for screening and later withdrawn from the Singapore International Film Festival (How, 2002). More recently another film, Singapore Rebel, about another opposition politician, Chee Soon Juan, was banned in Singapore (Koh, 2005). The Films Act is drafted so widely that it even prevented the ruling party, the PAP, from making a film to mark its 50th anniversary (Chia, 2005).

The combination of these laws makes it difficult for opposition parties and political pundits in Singapore to use the Internet as an effective means of campaigning during the election period. The effect of the legal regime in Singapore means that a website owner who persistently features political content is technically obligated to apply for a licence from MDA during the election period. The presence of such a requirement is enough to put off many would be political pundits, save for a rare few, from commenting actively on politics during the general election period.34 An illustration of this effect is the closure of the discussion site known as Singapore Internet Community (‘Sintercom’). When Sintercom was asked to register itself as a political website, its original founders decided to close the website.35 It is also technically illegal to distribute short political clips because such conduct is prohibited due to the expansive reach of the Films Act. As such, the Films Act would make it illegal for a person to make a short clip which is political in nature and upload it on a video sharing website such as Youtube.

The Singapore experience vividly demonstrates that a targeted use of specific legislation may prevent politicians and their supporters from using the Internet effectively. Consider the issue of political donations. In Malaysia, Jeff Ooi, a prominent blogger turned politician, successfully used his website to raise more than RM 100,000 for his campaign. Ooi did this by alerting his blog readers of his bank account number and setting up a Paypal account; Ooi then invited his readers to make contributions into both accounts.36 Such a strategy would not work in Singapore. Singapore’s Political Donation Act37 only permits donations from Singaporeans and expressly prohibits anonymous donations. Thus, Ooi’s strategy of canvassing for contributions via the Internet would not work in Singapore because it is envisaged that some of the political donations would be anonymous in nature.

7. Subverting the Dominant Discourse in Singapore: James Gomez and Bak Chor Mee

Despite the stringent legal control which exists in Singapore, the Internet has had some impact on the electorate during the 2006 general election.38 More specifically, the content on the Internet subverted the dominant discourse in the main stream media relating to an important campaign issue raised by the PAP. The incident which dominated much of the 2006 general election involved the Workers’ Party candidate, James Gomez, and a dispute with the Elections Department.39 To understand how the Internet had an effect on this matter, a background of the saga is briefly sketched out. On April 24, 2006, Gomez went to the Elections Department and asked for an application form for a minority certificate. This form had to be submitted to the Elections Department if Gomez was to be the designated minority candidate of a Group Representative Constituency.40 Gomez initially claimed that he had submitted the form to the Elections Department. Two days later, when the Elections Department could not locate the relevant form, Gomez went to the Elections Department and told the officials: ‘You know what’s the implications? Something must happen… ’41 Subsequently, Gomez’t s account that he had submitted the necessary form appeared to be contradicted by footage from the close circuit television tape. When confronted with this evidence, Gomez’s position was that he did not want to discuss his election administration over the media; in any case, he did not need the certificate because there was another minority candidate in his Group Representative Constituency (Foo, 2006). Matters did not rest there. In days to come, Gomez was subject to a barrage of questions and criticisms from the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister and the Finance Minister who all asked Gomez to give a full story of what happened and come clean over the incident (Sim, 2006). The Finance Minister said this matter was a question of accountability. In response to these demands, Gomez issued a statement at a political rally saying that he apologised if his actions had caused any distress or confusion to the staff of the Elections Department (Sim, 2006). Nevertheless, this apology did not cut any ice with his critics. Gomez was accused of trying to damage both the Elections Department and the government by pretending to submit his minority form (The Straits Times, Singapore, May 3, 2006). This issue was continually raised during the campaign period as ‘an issue which was crying out for an explanation’ (The Straits Times, Singapore, May 1, 2006) and Gomez was branded as a liar, a disgrace and a liability and had behaved in a manner which was blatantly dishonest (The Straits Times, Singapore, May 3, 2006).

It was around this time that a particular podcast put up by two bloggers, known as Mr. Miyagi and Mr. Brown, became very popular. Lee Kin Mun or otherwise known by his online moniker, Mr. Brown, started putting up a series of podcasts on his blog42 during the election period calling them the ‘persistently non-political podcast’. This is an obvious reference to the government’s position that bloggers who persistently engage in the propagating of politics must register with the MDA. One particular podcast captured the public’s attention; it featured a fictitious exchange, in a mixture of Hokkien and Singlish, between Jeff Lopez and a mince meat noodle seller (such noodles are known in the Hokkien dialect as ‘bak chor mee’). The skit featured Jeff Lopez ordering his lunch from the noodle seller. When the bak chor mee was served, Jeff Lopez asked the hawker why there was pork liver (known in Hokkien as ‘tur kwa’) in his noodles when he (Jeff Lopez) had asked for his noodles to be cooked without liver. The noodle seller became very indignant over this issue and pulled out footage from his close circuit television camera which showed Jeff Lopez did not ask for his noodles to be served without liver. When Jeff Lopez said sorry and that he wanted to move on and have his lunch, the noodle seller refused to accept his apology and kept on berating Jeff Lopez demanding that he explain why he said he did not want tur kwa in his noodles when he did not say initially that the noodles were to be served without liver. In a phrase that was to become iconic on the Internet, the noodle seller told Jeff Lopez ‘Sorry also must exprain (sic)’.

It was evident that this fictitious exchange was a thinly disguised parody of the James Gomez incident. This particular podcast became widely downloaded and talked about during the election period (Sim, 2006). It was reported that the podcast was downloaded more than 110,000 times since it was put up (Ibid). The bak chor mee podcast is significant to the issue of free speech during the election on a number of levels. First, the hilarity and the ridiculousness of the skit presented in the podcast subverted the PAP’s main message that the James Gomez incident was a serious issue that went to the integrity of that particular candidate. In fact, after the elections the Minister for Informations, Communications and Arts, Mr. Lee Boon Yang, said that although he found the clip ‘clever and funny’ he also ‘wondered if such humour could detract from the seriousness of the root political issue’ (Koh and Rajan, 2006). Second, the podcast also effectively broke Singapore Press Holdings’ (the main newspaper company in Singapore) editorial and reporting hegemony on this issue. The main newspaper in the country had covered this issue in a very deferential, somber and serious manner. By satirising the incident, the implicit message in the podcast was that the James Gomez affair was not really such a major issue in the election.

As an epilogue, James Gomez was questioned by the police after the election for allegedly committing the offences of criminal intimidation, giving false information and using threatening words and behaviour (Chia, 2006). After three sessions with the police, Gomez was let-off with a stern warning from the police.

8. The Rise of the Internet News Portal, Uber Bloggers and Blogger Politicians

Certainly in the aftermath of the 2008 Malaysian general election, the general consensus was that the Internet was a significant contributor to the shift among the electorate in favour of the opposition (New Straits Times, 2008). While the presence of Internet activism per se does not guarantee political success, the confluence of all the factors mentioned above in part IV together with the presence of credible Internet news portals and a remarkable proliferation of social political blogs and websites proved to be detrimental to Barisan Nasional. This phenomenon can be explained on several levels. The electorate in Malaysia seemed to have lost faith in the traditional main stream media and to place more trust on the information found on the Internet. If this is true, this meant the ruling party had lost a considerable advantage i.e. the monopoly of the medium in presenting information to the electorate. There is some empirical support for this assertion that the electorate especially the younger ones do place more trust and confidence on the Internet as compared to the mainstream press. In a study conducted in Malaysia between February 20 and March 5, 2008 involving 1,500 respondents between the ages of 21 and 50, more than 60 % of those between 21 to 40 years trusted blogs and online media for reliable information. In contrast, only 23 % of the people of that age group thought information from television programmes was trustworthy and 12 - 15 % of thought the same of newspapers.43 For those between 41 -50 years old, they trusted the mainstream media more than the Internet. If this study is accurate, this is a startling development where younger members of the electorate place more trust on the Internet as compared to the traditional main stream media. This is a worrying trend for Barisan Nasional; it was reported that the opposition had more than 7,500 blogs and websites as compared to 3 set up by the ruling party.44

The irony of the phenomenon above is this: if the main stream press is tightly controlled and eventually regarded by the electorate as sycophantic to the ruling government, the public will eventually lose confidence in the main stream media. A few influential websites filled this need for alternative points of view from what was available from the mainstream media. The first significant website is the award-winning news portal Malaysiakini. Malaysiakini was set up in October 1999 shortly after the launch of Malaysia’s Multi Media Super Corridor.45 The timing of Malaysiakini’s beginning was also fortuitous because it was set up a year after the former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s arrest. This news portal is frequently updated and regularly features hard hitting news and editorials. Malaysiakini proved to be so popular that during the general election, their website crashed and it had to provide many mirror sites in order to cope with the rising page views. Whenever a significant newsworthy event happens in Malaysia, Malaysiakini would experience a huge spike in viewership so much so that it has to provide a stripped down version of its website. The other website that became a thorn in Barisan Nasional’s side was Malaysia Today run by the inimitable Raja Petra Kamarudin. Unlike the serious-minded Malaysiakini, Malaysia Today is full of irreverent editorials, salacious gossip and conspiracy theories. Raja Petra’s regular features such as The Khairy Chronicles and The Corridors of Power are written like a daytime soap opera featuring the alleged shenanigans of politicians. However, the twists and turns of the Malaysian political scene in recent years involving a murdered Mongolian mistress, sodomy allegations, body snatching, statutory declarations that are made and later hastily withdrawn etc, left a lot of people wondering whether Raja Petra’s stories are really that far-fetched. Raja Petra also scored a ‘scoop’ on the mainstream press by being the first to report on the Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi’s engagement to Jean Danker (Malaysiakini, June 6, 2007; Yi and Tsin, 2007). Besides English language websites, there was also a remarkable proliferation of social and political blogs in the Malay language.46 In addition, the Islamic opposition party, Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (‘PAS’), also maintained a popular Malay news portal at Harakahdaily.net.

Another interesting occurrence is the rise of the blogger-politician in Malaysia. In order to capitalise on their reputation, the opposition fielded a few prominent bloggers as candidates in the general election. Two candidates from the Democratic Action Party, Tony Pua and Jeff Ooi won convincing victories in their constituencies (Seneviratne, 2008; Ping, 2008). It is believed that both individuals are the first blogger politicians in the world. Tony Pua became well known for an incisive and analytical blog on the state of the Malaysian education. In a country which is obsessed about the ranking of the universities in the annual Times Higher Education Supplement list, Pua was the first to ‘scoop’ the main stream press by demonstrating that University of Malaya’s top 100 ranking was based on an erroneous assumption of the foreign staff and student ratio.47 Ooi is one of the best known bloggers in Malaysia and often described as the most influential blogger in Malaysia (Wu, 2006). The rise of these blogger politicians shows an interesting synergy between a potential political candidate and the Internet. The success of Ooi and Pua, as bloggers and later as politicians, demonstrates that an aspiring politician may achieve a degree of fame and credibility by running a respected blog. This may in turn capture the attention of certain political parties into fielding such bloggers as candidates in the general election. The advantage of putting up such blogger politicians is obvious as they would already have a degree of brand equity with the electorate.

In contrast to Malaysia, there was no meaningful Internet news portal or blogger politician in the 2006 general election. However, two particular websites stood out during the 2006 GE – Sammyboy’s Alfresco Coffee Shop (‘Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop’)48and Yawning Bread.49 In their own ways, both these websites exerted considerable pressure on the hegemony of the main stream press as the principal news disseminator in Singapore during the 2006 general election. By way of background, Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop is an Internet message board which started its life as an off-shoot of a successful pornographic website. The founder of its parent website, a person who goes by the name Sam Leong, set up Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop because he found that some of his forum members in the original site were engaging in discourses other than a discussion of the sex industry.50 Thus, Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop was set up to accommodate these non-sexual topics. The topics found on this forum are quite wide ranging akin to informal gossip found at your local coffee shop. True to its raunchy beginning, the messages on Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop are often crude, sexist, racist, xenophobic, homophobic, profane, and scandalous and often consist of unsubstantiated rumours. Its popularity can be explained on the grounds that anyone can participate in this forum anonymously and in general no holds barred format of the discussion. During the 2006 general election, Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop’s real time coverage and lack of editorial control provided this forum with several advantages over the main stream press as a news disseminator. First, with virtually no production time whatsoever, this meant that the message board could publish breaking news much faster than the main stream press. In this regard, members’ posts on the board ‘scooped’ the main stream press on several newsworthy events in this election.51 Second, the members on this message board would often cut and paste newspaper articles and other reports from the main stream press and post this on the forum with their own comments. Other forum members would then post their take on the article and the piece would essentially be used as a starting point for a discussion on a particular issue (Balkin, 2004). By doing this, the members of the forum are in fact providing their own counter-editorial to the ones found in the main stream press. Finally, the fact that Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop is a public forum allowed it to harness the collective knowledge and manpower of its readers. The forum is constantly updated with new posts and readers would often write about their own experiences and observations on this message board especially with regard to election issues. In addition, a synergistic relationship developed between various blogs and Internet forums. Photographs, weblinks of videos of political rallies, overseas media coverage of Singapore and notable blogging commentaries were often posted on Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop.

Another website that became a runaway success during the 2006 general election is a website called Yawning Bread maintained by prominent gay activist, Alex Au. Au’s intelligent and incisive articles on election issues such as a review of the parties’ manifestos and a write up on the new candidates introduced by the ruling political party made the website popular with many Internet readers. Yawning Bread was responsible for perhaps the single most iconic photograph during the elections which was uploaded in a post called ‘On Hougang Field’ on May 1, 2006. Au snapped a picture of the crowd attending the rally from the 13th floor of a nearby flat; the resulting photograph showed a small lighted stage surrounded by a sea of people.

Due to the fact that the mainstream press did not initially publish any photographs showing the number of people attending opposition rallies, this snapshot quickly became one of the most talked about photograph in the country. Members of Sammyboy’s Coffee Shop copied this photograph and posted it frequently on the forum message board. Many blogs also carried this photograph. There was also some anecdotal evidence that this photograph was widely circulated by email during the election period. It was not difficult to see why this photograph gained prominence in such a short period of time. First, the startling crowd size shown in the picture puts to rest the assumption that Singaporeans are in general apathetic to politics. Those who saw the photograph thought that perhaps this election was different as people did care about political issues. Second, the fact that this photograph was not published in the mainstream press until a few days later gave rise to the general complaint that the mainstream media never published or reported anything good or positive about the opposition. On May 5, 2006, the Straits Times finally published the picture depicting the attendance at the Hougang rally which looked remarkably similar to Au’s own picture (Au, 2006). Au speculated that the Straits Times must have had in their possession the photograph taken from the same angle for more than 5 days.

As a postscript, there is a website which is developing along the model of Malaysiakini in Singapore. The Online Citizen was formed in December 2006 and comprises of a group of Internet activists (Yong, 2008). Like Malaysiakini, the website is updated frequently and regularly features hard hitting editorials. In addition, The Online Citizen regularly embeds relevant Youtube videos on its website. Therefore, it is unsurprising that this website has become very popular and averages about 10,000 ‘hits’ per day. Besides its online content, the editors and writers of The Online Citizen have been organising events for the public at Hong Lim Park to talk about issues such as a rise in public transport fees. The recent world financial crisis which resulted in many Singaporean investors losing their money in financial products based on credit default swaps have added to the visibility of this website. One of their regular feature writers have been organising well-attended weekly meetings at Hong Lim Park to talk about this issue (Suhaimi, 2008). The challenge for The Online Citizen is to move from a purely voluntary model to a commercial model like Malaysiakini and Ohmynews (Kim, 2006). 52 Otherwise, the pool of volunteer writers at The Online Citizen would find it difficult to provide their readers with comprehensive coverage like Malaysiakini.

9. Blogs, SMS, Message Boards and Connectors: An Alternative Campaign Platform

Members of opposition parties have long complained of several disadvantages in contesting in general elections in Singapore and Malaysia in terms of media coverage. Among the principal grievances are the alleged inadequate coverage and unfair portrayal of opposition members by the media. These structural imbalances between the ruling party and the opposition parties were ameliorated, to some extent, by the Internet during the recent elections in Singapore and Malaysia. What is interesting about these elections is that both elections were held at a time when there was a sizeable blogging community in Singapore and Malaysia. As I have argued elsewhere (Wu, 2006), blogs are different from other Internet websites because of inter alia a heavily hyperlinked architecture. This potentially can result in a spread of information in a rapid ‘viral’ form. Although, most Singaporean blogs are usually non-political in nature, during the election period there were some blogs which began to discuss election issues. In contrast, in Malaysia there was a massive proliferation of social and political blogs which covered the election issues extensively. Short messages via mobile phone (‘SMS’) were also utilised effectively during the campaign period in Malaysia. Unlike print materials such as posters, campaigning via SMS is relatively inexpensive and has the potential to spread in a ‘viral’ fashion. In the aftermath of the general election, Barisan Nasional conceded that they had ignored the power of the Internet to their peril.

Another medium in Singapore whereby election issues were covered is Internet forums and message boards. It is interesting that in Singapore forums and message boards appear to be more popular than Malaysia during the election. One possible explanation is that many people like to use these forums and message boards because they allow anonymous comments to be posted. The use of Internet forums and message boards in Singapore as sites of resistance (Ho, Baber and Khondker, 2002) is not a new phenomenon, but what is novel in the 2006 general election is the development of an architecture whereby blogs and Internet forums/message boards became inextricably linked making it a formidable network (Wu, 2006). For example, if a blogger puts up a post which is deemed noteworthy and well written, a reader might then include the weblink of this entry on his or her own blog, email his or her friends the contents of the entry and/or also post a link on popular internet forums/message boards and thereby giving the original piece a wide readership. In this election, robust election commentaries were found on a number of blogs. The intense interest and Internet readership on matters pertaining to local politics during the elections is evidenced by the fact that at the height of the James Gomez incident, the words ‘James Gomez’ became one of the most searched words on Technorati, a search engine dedicated to blogs.53 The evolution of the close network between blogs and Internet message boards is an important development. The resultant architecture of this heavily hyperlinked environment enables information, announcements, videos, audio files and pictures to spread at an amazing speed. It is surmised that this formidable network had something to do with the swiftness with which Mr. Brown’s bak chor mee podcast gained immense popularity.

Quite apart from acting as a medium of dissemination of photographs and commentaries, the other very significant development in this election is how the advent of digital technologies routed around certain legislation in Singapore such as the Films Act54 and the restriction that political rallies could only be held at certain places and at specified times. Recall that pursuant to the Films Act, the making of political films is not allowed and subject to criminal law sanctions. Despite this prohibition, videos of political rallies (especially rallies by opposition parties) were rife on the Internet. Anonymous persons would make videos of these rallies and upload them on Youtube. Blogs and message boards would then hyperlink these videos thereby giving rallies by opposition parties a wider coverage. Therefore, these videos overcame the temporal and geographical limitations imposed for the holding of political rallies. A person can view the rallies at any time by clicking on the relevant weblink.

As a campaign platform, the Internet has the advantage of being a medium which can potentially reach out to young voters. Unsurprisingly the Internet became an attractive campaign instrument for opposition parties in Singapore and Malaysia to reach out to the masses. Opposition party members have long accused the main stream press of publishing unflattering pictures making them look shifty and untrustworthy e.g. with their eyes half closed or mouth agape. With the development of the network of blogs and message boards, supporters of opposition parties also used similar strategies. Pictures of politicians from the ruling party taken at unflattering angles quickly found their way on to blogs and message boards. In addition to publishing such photographs, the resultant architecture of blogs and message boards was used as an alternative platform for commentaries. Speeches by PAP and Barisan Nasional politicians, news reports and editorials in the main stream press are rapidly dissected and mercilessly critiqued. Any unfortunate comments will be pounced upon and stinging replies and rebuttals will quickly find their way on to the Internet.

As mentioned above in section 3, an often-made observation about the limitation of the influence of the Internet on the electorate is the digital divide. It is interesting to note that the degree of Internet usage in Malaysia is not as high as that in Singapore. However, the recent general election in Malaysia has shown that the problem of the digital divide may be exaggerated. There are many anecdotal accounts of how photocopied materials from the web are distributed to the rural electorate who may not have access to a computer (Low, 2008). An anecdote told to the present author by a politician is that many people in the villages spend a lot of time gossiping about politics in the local coffee shop. In these coffee shops, there would be at least one person who would have access to the Internet, read everything and printed the web materials for his or her friends to read. Using the terminology of Malcolm Gladwell’s Tipping Point (2001), these people act as connectors for those who do not have access to the Internet to start a ‘viral’ spread of information. Another vivid example of the influence of the digital media on the rural electorate is Hindraf’s road shows across the country to the rural India community in Malaysia. According to the Chief Editor of Malaysiakini, Steven Gan, Malaysiakini made a DVD called ‘Hard Questions No Answers’ which featured demolition of temples, indentured labor in the rural areas and eviction of squatters.55 During Hindraf’s visits to the Indian villages, this DVD was shown. It is surmised that this had something to do with the huge turnout in the protest rally in Kuala Lumpur.

10. Generating Norms on the Internet: The Spillover Effect, Cascades and Polarisation

A very interesting phenomenon that can be observed during the general elections in both countries is how the norms on speech on the Internet might conflict with the norms that exist in real life. With regard to the norms pertaining to speech, people appear to be more vocal, hyper-critical and less diffident in expressing their views on the Internet as compared to how they would act off-line. In Singapore and Malaysia, it is not usually the norm for the electorate to criticise their political leaders openly in a harsh manner.56 Political leaders are usually accorded a degree of respect by reason of their office. However, this norm is rendered almost meaningless in the online world. In the cold flicker of the computer monitor involving a text based discourse, a person is stripped from the aura and prestige of his or her office and is judged solely by the quality of his or her ideas.57 The Internet has facilitated an environment whereby members of the online community sharply contest ideas put forth by their leaders on blogs, message boards, news portals etc. Thus, the rules of engagement of the electorate with their leaders appear to be quite different online as compared with that which exists off-line. It is suggested that these Internet norms inevitably have a spillover effect into the offline world and would affect the dynamics of the relationship between the electorate and their political leaders. Malaysia Today’s irreverent take on politics and politicians, the hilarious Bak Chor Mee podcast, Malaysiakini’s hard hitting editorials and Talking Cock’s merciless satire of Singaporean politicians (Johal, 2004) are but a few examples of how speech norms operate differently in cyberspace.

However, one must be careful not to overstate the significance of the Internet and fall into the trap of Internet triumphalism. It is not the contention of this paper that the presence of robust Internet norms has made offline speech norms redundant. Far from being irrelevant the latter still dictates much of the way public discourse takes place in important traditional mediums like television, newspapers and radio. However, what is important to appreciate is that the norms governing digital speech exert considerable pressure on the traditional norms and make the latter less stable. This is because it is not possible to keep the Internet speech norms confined to the cyber world. Inevitably, as incidents such as the Bak Chor Mee podcast demonstrates, these norms have a habit of ‘leaking’ out to the non-virtual world and affecting the public discourse.

Another important point to note is effect of group polarisation on decision making. Cass Sunstein christens this problem in his book Infotopia as ‘cascades and polarization’ in deliberating groups. Sunstein argues when group polarisation happens ‘members of a deliberating group typically end up in a more extreme position in line with their tendencies before deliberation began (Sunstein, 2006).’ Thus, the Internet could possibly be one of the contributing factors to Barisan Nasional’ s poor showing in the general election in Malaysia. Due to the multiple unfavorable incidents, a sizeable portion of the electorate with direct or indirect access to the Internet was involved in a form of cascade and polarisation against voting for the Barisan Nasional.

11. Setting the Agenda in the Mainstream Media: Powerful Echo Chambers

One of the frequent criticisms of the Internet is that it has the tendency of being an ‘echo chamber’ (Sunstein, 2007) i.e. that people usually only seek out news and opinions that reflect their pre-existing views. It could very well be that the Internet community in Singapore and Malaysia could be characterised as an echo chamber comprising of young, well educated, and technologically savvy people with libertarian beliefs. These people can hardly be said to represent the majority of the Singaporean and Malaysian population. If the Internet community is nothing more than an echo chamber, then it is arguable that its influence is largely overstated.

However, I believe that the creation of an echo chamber within the Internet community does not necessarily mean that the Internet community’s effect on the rest of the Singaporean and Malaysian society is overestimated. On the contrary, the existence of an echo chamber can sometimes enhance the power of the Internet community in certain circumstances. I call this phenomenon the creation of ‘powerful echo chambers’. Staying with the metaphor of an echo chamber, ‘powerful echo chambers’ have the tendency of making the voices of its members louder than it usually is. Thus, ‘ powerful echo chambers’ can act like a megaphone in amplifying a lone dissenting voice in the wilderness. This is important as it might affect how journalists in the main stream media write their stories and the way government officials collect feedback from the population. Well known websites in Malaysia like Malaysia Today and Malaysiakini and blog aggregators in Singapore such as Tomorrow.sg have regularly pushed certain stories on to the front pages of the mainstream press. As such, these websites have helped shape the agenda for political discourse in the country. It is also not uncommon for lesser known websites to push certain stories into the mainstream media. With regard to this point, a story that gains a certain ‘buzz’ or currency on the Internet could tip off a journalist to write about the story in the main stream press (MacKinnon, 2007). Such a write up will then effectively push an otherwise ignored issue into the consciousness of members of the public. Besides pushing certain stories into the national (and sometimes international) press, it is surmised that ‘powerful echo chambers’ provide a channel of feedback to the government. Government officials are also human and this author speculates that it is more convenient for them to obtain feedback from ‘the person on the street’ by surfing the Internet rather than doing a face to face survey of the population.

12. The Digital Scarlet Letter: Wikipedia and Youtube as Badges of Shame

In a fascinating book, Daniel Solove explores how the Internet is increasingly used inter alia to shame transgressors of social norms (Solove, 2008). He likens this phenomenon to tagging the wrongdoer’s identity with a digital scarlet letter (Ibid). It is beyond the scope of this paper to assess whether this is a desirable phenomenon. For the purposes of this paper, it is sufficient to note that the digital scarlet letter phenomenon applies in the law of politics as well. Embarrassing gaffes and other unfortunate remarks made by politicians are preserved on the Internet. If there is a video recording of the event, it is highly likely that the video will find itself on Youtube. Almost instantaneous entries and updates on Wikipedia will inevitably spring up detailing the gaffes and remarks. Therefore, the Internet prevents slip ups by politicians from being easily forgotten. Every time someone searches for the particular politician’s name, either the relevant Wikipedia entry or an Internet website recording the gaffe would be among the results in the first few pages of the search. Thus, awkward incidents such as sex scandals, keris waving, racist comments etc would continue to follow a particular candidate for a very long time. It is suggested that this digital scarlet letter effect has a discernible impact on political speech norms. For example, after the 2008 Malaysian general election, any shrewd thinking politician would have to think very hard before waving a keris. Even though such rhetoric have traditionally appealed to certain quarters of the electorate, the price of bearing such a digital scarlet letter may be too great to bear for any politician hoping to achieve mainstream acceptance.

13. Conclusion

In writing this paper, I hope I have not over romanticised or exaggerated the influence of the Internet community in carving out a social space for free expression in Singapore and Malaysia. A cynic might be quick to challenge the thesis of this paper by pointing out that the contents of most of the blogosphere have nothing to do with politics or serious social issues. But despite this cynicism, I would argue that the basic thesis of this paper is still valid i.e. that the existence of a vocal Internet community in Singapore and Malaysia has exerted pressure on the laws, norms and structural restraints that govern free speech in both countries. In Singapore, the Internet has only exerted a modest pressure; on the other hand, the Internet has been credited as one of the major contributory factor for the opposition’s success in 2008 general election in Malaysia. While I do believe that the presence of vibrant Internet communities does have the effect of widening the social space for free expression in Singapore and Malaysia, I am also extremely mindful that such influence is fragile. The online community is not immune to the laws that exist off line which suppress free speech. At the time this paper is written, two high profile defamation suits have been filed in Malaysia by the New Straits Times against two prominent bloggers (The Straits Times, Malaysia, Jan.23, 2008). Raja Petra of Malaysia Today was detained for a few months without trial under the Internal Security Act before being freed pursuant to a habeas corpus application (Jong, 2008). Such developments could also happen in Singapore and ‘chill’ digital speech. On a positive note, there are signs of a nascent and promising Internet activism movement in Singapore as evidenced by the activities of the people behind The Online Citizen. In this regard, one senses that the Singaporean government’s policy on digital speech is in a state of flux. It remains to be seen whether this digital social space in Malaysia and Singapore will be subjected to harsher legal restraints.

Endnotes

* Thanks are due to Amanda Whiting, Arun Mahizhan, Tan Tarn How, Shin-yi Peng, Jothie Rajah, Naomita Royan and Anne Cheung for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. I am also indebted to Haniza Binte Mohd Reeza Abnas for her excellent research assistance and Tan Choog Ing for proof reading an earlier draft. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Institute of Policy Studies at the National University of Singapore, Singapore Management University, Centre of Media and Communications Law at Melbourne Law School, and Institute of Law for Science and Technology at National Tsinghua University. I am grateful to the participants at these forums for fielding comments and questions.

1 For previous investigation on the impact of the Internet and politics in Singapore and Malaysia see, George, C (2005), ‘The Internet’s Political Impact and the Penetration/Participation Paradox in Malaysia and Singapore’, 27 Media, Culture & Society, p. 903; George, C (2006), Contentious Journalism and the Internet: Democratizing Discourse in Malaysia and Singapore.

2 The Malay and English blogs were divided on the issue of a Member of Parliament who handed in a petition to lower the volume of the daily Muslim prayer emanating from the local mosque. For a background to this incident see, ‘ Police reports lodged against Teresa Kok’, THE STAR, (Sept. 14, 2008), available at: The Star Online: Home/News/Nation. For divided opinions see e.g.: ‘Teresa Kok is innocent’, Aisehman.org, available at: <http://aisehman.org/?p=674> (Sept. 14, 2008); ‘Terbalikkan gambar Teresa Kok’, PolitikBanjar, available at:<http://politikbanjar.blogspot.com/2008/09/abo-8-sesudah-subuh-916-terbalikkan.html> (Sept. 22, 2008).

3 For example one of the most popular websites in Singapore that garners 50,000 daily ‘hits’ is about the live and love of a twenty something young woman. See, Yong, D, ‘Xiaxue Won't Say Sorry To Dawn’, The Straits Times (Singapore), July 23, 2008, available at: Factiva.

4 Malay. Const., art. 159(3).

5 ‘Nation's political landscape dramatically transformed’, Malaysiakini, Mar. 9, 2008, available at: Malaysiakini.com; see generally, Beng, O K et al. (2008) ‘March 8: Eclipsing May’, p. 13.

6 For an excellent overview see, Wong, C H (2005), ‘The Federal and State Elections in Malaysia, March 2004’, 24 Electoral Studies, p. 311; Mohamad, M (2004), ‘Malaysia’s 2004 General Elections: Spectacular Victory, Continuing Tensions’, 19 Kasarinlan: The Philippine Journal of Third World Studies, p. 25.

7 Chow, K H (Nov. 6, 2007), ‘ Indians Take To KL Streets Against Discrimination’, The Straits Times (Singapore), available at: Lexis-Nexis where it was reported 5,000 people showed up. In contrast see, Guan, L H (2008), ‘ Malaysia in 2007: Abdullah Administration under Siege’, Southeast Asian Affairs, p. 187 at 190 which states that 20,000 – 50,000 attended the rally.

8 See, e.g. Ex-No 1 Umno member continues attack on PM, Malaysiakini, May 20, 2008, available at: Malaysiakini.com; Leong, C K, ‘Pak Lah can't manage finance: Dr M’, Malaysiakini, Sept. 18, 2008, available at: Malaysiakini.com.

9 SING. CONST. (Rev. Edn), art.14; MALAY. CONST., art. 10.

10 Sedition Act, c. 290, (1985 Revised Edn.) (Sing.); Sedition Act, 1948, (Malay.)

11 See, s. 7 of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act, c. 322 (1999 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.). See also, Attorney General v. Lingle [1995] 1 S.L.R 696 (Sing. C.A.); Defamation Act, 1957, (Malay.).

12 See, e.g. JB Jeyaretnam v. Attorney General [1989] 1 M.L.J. 137 (Sing. C.A.).

13 Internal Security Act, c. 143, (1985 Rev.Edn.)(Sing.); Internal Security Act, 1960, (Malay.). See e.g., Fritz, N and Flaherty, M (2003), ‘Unjust Order: Malaysia’s Internal Security Act’, 26 Fordham Int’L L.J., p. 1345.

14 Official Secrets Act, c. 213, (1985 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.); Official Secrets Act, 1972, (Malay.).

15 For an overview of the press in Malaysia see, Idid, S A (1998), ‘Malaysia’ in Asad Latif (ed.), Walking the Tightrope: Press Freedom and Professional Standards in Asia, p. 119; Safar, H M, Sarji, A B and Gunaratne, S A (2000), ‘ Malaysia’ in Shelton A. Gunaratne (ed.), Handbook of Media in Asia, p. 317.

16 Printing Presses and Publications Act, 1984, (Malay.). See also, Harding, A (1996), Law, Government and the Constitution in Malaysia, pp. 197-198; Newspaper and Printing Presses Act, c. 206, (2002 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

17 C. 257, (2001 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

18 C. 224, (1985 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

19 C. 167A, (2001 Rev. Edn) (Sing). See, Winslow, A V (1990), ‘Separation of Religion and Politics: The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act’, 32 Mal. L. Rev. p. 327; Hang, T T (2008), ‘Excluding Religion From Politics and Enforcing Religious Harmony Singapore Style’, Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, pp.118-142.

20 C. 218, (2001 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

21 C. 28, (2003 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

22 C. 107, (1998 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

23 Cf. It is likely that the law would be changed by the next Singapore election. See, Oon, C ‘ Political Podcast to Be Allowed by Next GE’, The Straits Times (Singapore), Jan. 10, 2006, available at: Lexis.

24 C. 218, (2001 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

25 C. 28, (2003 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

26 C. 218, (2001 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

27 C. 28, (2003 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

28 Broadcasting (Class Licence) Notification. (15th July 1996), available at: <http://www.mda.gov.sg/wms.file/mobj/mobj.487.ClassLicence.pdf> (last visited Jan. 01, 2009).

29 C. 107, (1998 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.). Cf. It is also likely that the Films Act would be amended by the next Singapore election. See, Oon, C ‘ Green Light And Grey Areas; Which Political Films Get The Go-Ahead Will Depend On How New Rules Are Applied’, The Straits Times (Singapore), Jan. 16, 2006, available at: Lexis.

30 Yeo, B G ‘Explains Ban on Party Political Films’, The Straits Times (Singapore), Feb. 28, 1998, available at: Lexis. See also,Thio, L (2002), ‘The Right to Political Participation in Singapore: Tailor-Making a Westminster-Modelled Constitution Fit the Imperatives of ‘Asian’ Democracy’, 6 Singapore Journal of International and Comparative Law, p. 181 at 210 -211.

31 Films Act, c.107, s. 33, (1998 Rev. Edn.)(Sing.).

32 Films Act, c. 107, s. 2, (1998 Rev. Edn)(Sing.).

33 See concerns of a group of film makers in Singapore expressed in ‘Film Act: Film-makers Seek Clarification’, The Straits Times (Singapore), May 11, 2005, available at: Lexis.