Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Cross v Coach House Mews (Highbury) Ltd (RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - modification - covenants restricting extensions or external alterations) [2022] UKUT 20 (LC) (27 January 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2022/20.html

Cite as: [2022] UKUT 20 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2022] UKUT 20 (LC)

UTLC Case Numbers: LC-2020-42

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - modification - covenants restricting extensions or external alterations - planning permission for extension - whether covenants secure practical benefits of substantial value or advantage - s.84(1)(aa) and (c), Law of Property Act 1925 - application dismissed

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION UNDER Section 84 of the Law of Property Act 1925

BETWEEN:

NICHOLAS CROSS

HANNAH CROSS

Applicants

-and-

(1) COACH HOUSE MEWS (HIGHBURY) LTD

(2) RUTH YOUNG

(3) BENJAMIN O’DONNELL

(4) ROMANY O’DONNELL

Objectors

|

|

|

|

Re: 7 Coach House Lane,

London,

N5 1AW

Mr Mark Higgin FRICS

3 November 2021

Royal Courts of Justice

Mr Andrew Skelly, instructed by Osbornes Law for the applicants

Mr Jonathan McNae for the objectors

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2021

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Re Bass Limited’s Application (1973) 26 P & CR 156

Martin v Lipton [2020] UKUT 8 (LC)

Shephard v Turner [2006] 2 P. & C.R. 28, [2006] EWCA Civ 8

Introduction

1. Mr Nicholas Cross and Mrs Hannah Cross (“the applicants”) are the freehold owners of 7 Coach House Lane, London N5 1AW (“the property”), a three-storey mews house constructed in 1991. It forms part of a small development of 18 similar houses situated on land formerly used as gardens and a coach house to the west of Highbury Hill and close to the Emirates Stadium.

2. On 9 July 2020 the applicants received planning consent (“the planning consent”) from the London Borough of Islington (“the Council”) for the construction of a ground floor extension of 7.4 m2, adjacent to the south eastern elevation and occupying the site of a path which provided access to the rear garden of the property. The proposed extension, although small, would allow the applicants to reconfigure the interior of their house and provide better use of the floorspace for their expanding family.

3. The twenty one freehold owners of Coach House Lane and Coach House Mews (Highbury) Ltd, a management company owned by them (“the Company”) benefit from a covenant which prevents the erection of, or material alteration or addition to the external appearance of, any buildings, walls, fences or other structures. I will examine the covenant in detail as part of this decision.

4. The applicants applied to the Tribunal on 30 November 2020 for the modification of the restrictions on grounds (aa) and (c) of section 84(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

5. The modification sought is to permit the construction of a single-storey side extension on the property in accordance with the planning consent.

6. There were four objections to the application from:

(i) Coach House Mews (Highbury) Ltd

(ii) Ruth Young (16 Coach House Mews)

(iii) Benjamin O’Donnell (17 Coach House Mews)

(iv) Romany O’Donnell (17 Coach House Mews)

7. The applicants were represented at the hearing by Mr Andrew Skelly who called Mr Nicholas Cross as a witness of fact. The objectors were represented by Mr Jonathan McNae who called Mr Paul Spibey, Mr George Clark, Mr Benjamin O’Donnell, Ms Ruth Young and Mr Michael Kingsley as witnesses of fact. I am grateful to both Counsel for their submissions.

8. I inspected the property on Monday 1 November 2021. I walked around the entire development and viewed the intended site of the extension together with the rear garden of the property. I also viewed the site of the extension from the first floor of No. 17 Coach House Lane. Whilst in that property I took note of the bi-fold doors that had been installed at the rear. The reasons for doing so will be apparent when I return to this matter later in the decision.

The Factual Background

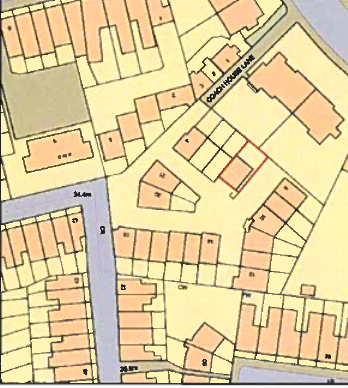

9. Coach House Lane comprises three terraces of three storey townhouses in an essentially ‘V’ shaped arrangement with a pair of three storey semi-detached houses located within the ‘V’. The plan below shows the layout, and the property is shown edged red. Although the plan shows the neighbouring properties as unshaded the property itself forms part of a terrace of four properties. Vehicular access is by means of a gated, single-track roadway from Highbury Hill. The Estate was designed by the architectural practice of Maxwell Hutchison in the late 1980s. Mr Hutchison is an architect of some standing having been the president of the Royal Institute of British Architects from 1989 to 1991 and has subsequently advocated good architecture on television and radio.

|

10. The development is characterised by elevations of brick and white-washed render. The main roofs are pitched and covered with slate. There are some small areas of flat roof at ground floor level, and these are felted and concealed behind parapet brickwork. The design incorporates two styles of windows which are deployed throughout the development, namely simple softwood, single glazed casements, and larger fixed panels containing multiple square panes, again originally constructed in softwood. These panels are referenced on either side of the main entrance doors with a vertical arrangement of similar panes. Above each door is a faux stone portico. The property itself is wider than its neighbours and set back from the others in the same terrace. The houses in the development are not identical. On my site visit I noted that Nos.10 and 11 are significantly different in appearance, No. 13 has a single storey, flat roofed projection at the front and at No.19 there is a stepped front elevation with a wrought iron gateway.

11. Throughout the development most of the external woodwork is painted brilliant white, but the garage and entrance doors are finished in Monarch Red. Where windows have been renewed the owners have taken care to ensure that the replacements match the originals and repainted doors are all in the same shade of red. Several owners have reconfigured the internal layout by incorporating the garage into the living space on the ground floor. This has been achieved by leaving the garage door in place thereby preserving the exterior appearance of the house. However, it has removed the ability to park a car out of sight and the result is that there are parked cars in the roadways around the development. Their presence, together with the positioning of the buildings contributes to a rather crowded streetscape.

12. When consent was originally granted for the development permitted development rights were excluded from the planning permission which means that small scale alterations that ordinarily would not need planning permission require consent.

13. The proposed extension would sit adjacent to the flank wall of the property and extend along its full length at ground floor level. Internally the extension is about 7.25 metres long with a width of 1.02 metres. At the eaves it is intended to be 2.5 metres high and at the point where the new roof will join the existing wall it is 3.08 metres tall. Part of the new floorspace would be incorporated into an area currently used as a living area and a bathroom. A second area accessed by a door on the front elevation is to be used for storage. The walls are to be brick built and those at the front and rear are to be constructed as continuations of the respective elevations. The roof will be a mono-pitch design, partly in glass with a slope of about 30 degrees. In its current configuration the property has an unusual internal layout with two bedrooms on the second floor, one on the ground floor and a kitchen and lounge on the first floor. The proposed layout relocates the lounge and kitchen into a single space on the ground floor and facilitates two bedrooms and an en-suite bathroom on the first floor. The garage is to be incorporated into the living space although the external door is retained.

14. The Planning Officer’s report dated 6 July 2020 recommended consent be given and made several observations in relation to conservation and design issues. He considered the proposed extension to be “subordinate to the host building, given its restricted projection from side elevation and use of a sloping roof.” He also noted that the “proposed fenestration details to the front and rear elevations are considered to be in keeping with the host building and wider area.”

15. He went on to say that:

“It is acknowledged that the host building forms part of a relatively unaltered terrace which provides a degree of symmetry. However, it should be noted that the host building is set back from the remaining terrace, and the proposed extension is not considered to be of a scale or design which would significantly interrupt this existing arrangement. Officers consider the alterations to be sympathetic to the design of the original building, the terrace as a whole as well as the setting of the adjoining conservation area”.

The legal background

The restrictive covenants

16. The property forms part of the Coach House Mews Estate (“the Estate), being land derived from Title No. NGL629828 and NGL629829. It was originally sold by a transfer dated 09.09.1991 (“the 1991 Transfer”) which imposed a restrictive covenant, in the following terms:

“For the benefit and protection of the land comprised in the Estate (other than the Property) and each and every part thereof so as to bind the Property into whosesoever hands the same may come the Purchaser HEREBY COVENANTS with the Vendor and the Company and as a separate covenant with every other person claiming under the Vendor as purchasers of any part or parts of the Estate that the Purchaser and the persons deriving title under him will at all times hereafter observe and perform the covenants conditions and other matters on his part set out in Schedule 4.

Schedule 4:

3. New Buildings

(a) Not at any time to erect or suffer to be erected any buildings walls fences or other structures on the Property (save for any future replacements of existing buildings screen walls or fences and save further for the construction of a wall between the points marked “A” and “B” on the Estate Plan in material and to a specification previously approved).

(b) Without prejudice to paragraph 3(a) of this Schedule not to make or suffer to be made any material alteration or addition to the external appearance of the buildings walls fences railings and other structures now on the Property or to alter or suffer to be altered the external decorative scheme of the Property and such buildings walls fences railings and other structures thereon from that which exist at the date hereof.”

Since August 2018, the Applicants have been the registered freehold proprietors of 7 Coach House Lane.

17. The Restriction is not applied uniformly to the whole Estate. In the case of No. 17 a unique qualification to the restriction permits the owner to “enlarge the ground floor window at the rear of the Property provided that the full specification for the work is first produced to and approved by the Vendor (such approval not to be unreasonably withheld or delayed)”. The transfer of No. 17 which contains that qualified version of the restriction is dated 17 June 1998 some 6 years after the Estate was built.

The statutory provisions

18. Section 84 of the Law of Property Act 1925 provides, so far as is relevant:

“84(1) The Upper Tribunal shall ... have power from time to time, on the application

of any person interested in any freehold land affected by any restriction arising under

covenant or otherwise as to the user thereof or the building thereon, by order wholly or

partially to discharge or modify any such restriction on being satisfied-

...

(aa) that (in a case falling within subsection (1A) below) the continued existence

thereof would impede some reasonable user of the land for public or private purposes

or, as the case may be, would unless modified so impede such user; or

...

(c) that the proposed discharge or modification will not injure the persons entitled to

the benefit of the restriction; and an order discharging or modifying a restriction under this subsection may direct the applicant to pay to any person entitled to the benefit of the restriction such sum by way of consideration as the Tribunal may think it just to award under one, but not both, of the following heads, that is to say, either—

(i) a sum to make up for any loss or disadvantage suffered by that person in

consequence of the discharge or modification; or

(ii) a sum to make up for any effect which the restriction had, at the time when it was imposed, in reducing the consideration then received for the land affected by it.

(1A) Subsection (1)(aa) above authorises the discharge or modification of a restriction by reference to its impeding some reasonable user of the land in any case in which the Upper Tribunal is satisfied that the restriction, in impeding that user, either -

(a) does not secure to persons entitled to the benefit of it any practical benefits of

substantial value or advantage to them; or

(b) is contrary to the public interest; and that money will be an adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which any such person will suffer from the discharge or modification.

(1B) In determining whether a case is one falling within section (1A) above, and in

determining whether (in any such case or otherwise) a restriction ought to be discharged or modified, the Upper Tribunal shall take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permissions in the relevant areas, as well as the period at which and context in which the restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances.

(1C) It is hereby declared that the power conferred by this section to modify a restriction

includes power to add such further provisions restricting the user of or the building on the

land affected as appear to the Upper Tribunal to be reasonable in view of the relaxation of the existing provisions, and as may be accepted by the applicant; and the Upper Tribunal may accordingly refuse to modify the restriction without some such addition.”

The Application

19. The application was made primarily under ground (aa) but also under ground (c) in order that the planning permission could be put into effect. This being the case Mr Skelly had agreed with Mr McNae that the Tribunal needed to determine each of the following issues based on the questions to be considered under ground (aa) as set out in Re Bass Limited’s Application (1973) 26 P&CR 156:

ii) Whether the Restriction secures practical benefits to the objectors.

iii) Whether any practical benefits that may be identified are of substantial value or advantage to the objectors.

iv) Whether money would be an adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage which any objector will suffer from the modification.

v) Whether the Restriction should be modified so as to permit the proposed development.

vi) Whether the proposed development would cause a diminution in the value of the objectors’ properties.

vii) Whether, if the Restriction is modified, compensation should be awarded in consequence of such modification.

20. Mr Skelly noted that the Company accepted that the proposed user was reasonable, and that the restriction impedes that user. In objecting Mr and Mrs O’Donnell and Mrs Young said that they did not agree that the covenant impeded the reasonable use of the land. Mr Skelly submitted that this stance was unsustainable and that the fact that the planning permission had been granted was strongly supportive of the user being found reasonable.

The Objections

21. The objections were focused on the practical benefits arising from the covenant. The first of these was certainty, insofar as all residents were aware that the external appearance of their homes could not be altered. This ensured the continuance of the second benefit which was the visual uniformity conferred by the original design. Finally, it was said that the covenant prevented the setting of precedents for modification, the so-called ‘thin end of the wedge’.

Evidence of the Applicant

22. Mr Cross and his wife moved to Coach House Lane in February 2018. He explained that since that time they have started a family and the need to reconfigure the layout of the house had become more pressing. An architect was engaged in March 2020 and the feasibility of extending on to the small strip of land to the side of the house was explored. This strip provided access to the rear garden and was, according to Mr Cross, obscured by shrubbery in an adjacent flowerbed. The intention was to design an addition that was as inconspicuous as possible and to be in keeping with the rest of the Estate. It was anticipated that the reaction from neighbours would be one of indifference. Mr Cross noted that the design of the Estate is not uniform and that the potential for replicating the type of extension planned for his house was extremely limited, the only other house with a similar strip of land being No. 8.

23. During the planning application process Mr and Mrs Cross sent details of the proposed extension to all of the residents at Coach House Lane and received comments from the occupiers of Nos. 4 and 19 expressing concerns about elements of the design. In response Mr and Mrs Cross sought to assuage these anxieties by proposing some amendments and indicating that he would re-use bricks from the existing side wall to ensure a good match with the front elevation. Three formal comments were received by the Council when the application was made and these related to design, the presence of the covenants and the impact on delivery drivers as a result of the extension.

24. The comments of the Planning Officer have been set out already, but Mr Cross thought that the Council had been ‘challenging and robust’ with other, previous applications. They had turned down an application in relation to No. 4 in 2012 because the proposed alteration would ‘damage the visual unity of the terrace group’ and had made reference to the removal of permitted development rights ‘to preserve its coherent architectural character’.

25. While the planning process was ongoing Mr and Mrs Cross sought to engage with the Company and other neighbours with the intention of securing agreement to modify the covenant. Ultimately this approach proved fruitless, and the Company turned down their request.

26. Mr Cross drew attention to the unique position at No. 17 where the covenant was altered to permit the enlargement of the ground floor window on the rear elevation and to persistent breaches of a covenant restricting parking on the Estate, to which he said the Company turned a blind eye.

27. In summary Mr and Mrs Cross do not believe that their plans will cause any harm to their neighbours, and they have not received any comments from the owners of the houses that directly overlook the side of their house. Additionally, they do not believe that their plans will set any precedent by ‘opening the floodgates to other extensions’.

Evidence of the objectors

Mr Paul Spibey

28. Mr Paul Spibey who lives at No. 13 gave evidence on behalf of the Company. He has been a director of the Company for more than 20 years and to his recollection there have been no new buildings erected or extensions to properties in the Estate. He explained that the houses on the Estate were sold subject to numerous restrictive covenants, and these were intended to apply to all property owners and their successors in title. He went on to explain that the covenants and their mutual enforceability suggested a desire on the part of the original developer to retain and maintain the design, aesthetic appearance, and character of the Estate.

29. He noted that in May 2020 the owner of No. 10 had sought to extend the ground floor of their house, but permission from the Company was refused and the owner subsequently acknowledged that the proposed extension would have breached the covenant.

30. Mr Spibey’s primary concern was that if the covenant was modified to allow the extension at the property it would lead to other owners seeking permission from the Company to extend their properties. In his view this would not be in the best interests of most of the owners who live on the Estate. In seeking permission to modify rather than declare the covenant obsolete, he presumed that there was an acceptance on the part of Mr and Mrs Cross that the covenant confers some benefit on owners, not least in maintaining the uniformity, appearance, and value of houses on the Estate.

31. He also disagreed that there was limited scope for other extensions. He considered that the majority of owners could extend into their rear gardens and others might seek to build porches at the front.

32. Finally, he considered the property to be in a central position and the proposed extension would be visible from many houses including his own, implying this to be a negative attribute.

Mr George Clark

33. Mr Clark has also lived at the Estate since it was constructed in 1992. He has served as a director of the Company and has training and qualifications in Town Planning and Urban Design. However, he did not practice in Town Planning and spent his career as a civil servant specialising in social research. He appeared as a witness of fact and not as an expert witness.

34. His comments mainly concerned the visual appearance of the proposed extension. He thought it marked a departure from the ‘visual integrity of the Estate frontages’. He considered that the Planning Officer’s comments just related to the terrace of which the property formed part and did not take account of the impact on the Estate in its entirety. In particular he thought that the additional door in the front elevation and the sloping roof line would damage the integral design of the Estate as a whole and that the roof would be at odds with the strong vertical and horizontal features which were a characteristic of the Estate. He concluded that the extension would have a significant impact on the appearance of the Estate and that were it to go ahead the case for protecting the architectural aspects would be severely undermined.

Mr Benjamin O’Donnell

35. Mr O’ Donnell and his wife, Romany, have lived at No.17 since 2004. They were made aware of the covenant when purchasing their house and understood that they would benefit from the restriction in the knowledge that the other owners were similarly affected. He described the covenant as being ‘fundamental to us’ as it ensured the architectural integrity of the Estate and restricted extensions. In common with Mr Spibey, he said that there were other houses that would benefit from extensions, but he went further, stating that were any to be built it would have a material effect on the health and wellbeing of himself and his wife.

36. He also stated that the extension would be clearly visible from the first and second floors of his house, implying that this would be disagreeable to him. Whilst I was at Coach House Lane Mr and Mrs O’Donnell kindly allowed me access to the first and second floors. The extension would indeed be visible but only obliquely and then just in winter when the tree which is situated between the two properties is not in leaf.

37. Mr and Mrs O’Donnell are the owners of the only house in the Estate that has benefitted from a significant alteration, namely the installation of full width bi-fold doors at the rear of the property. This has been accompanied by a re-configuration of the type sought by Mr and Mrs Cross. The qualified covenant that permitted this change is contained in deeds dated 17 June 1998 and obviously predated the O’Donnell’s acquisition.

Ms Ruth Young

38. Ms Young is a new arrival at Coach House Lane having purchased No. 16 in January 2021. Her solicitor had explained the restrictive covenants and the proposed extension, but she said in her witness statement that had she realised that there was a possibility that they could be modified she might have reduced her bid. She later admitted in cross examination that she knew that covenants could be altered.

39. Ms Young said that for her the issue was the ‘thin end of the wedge’ and a point of principle. She thought that if the covenant was modified the Estate would have the potential to become just another group of houses and values could be adversely affected. That the extension would be visible from the front of her house would impact on her enjoyment.

Mr Michael Kingsley

40. Mr Kingsley is a co-director of the Company and has owned No. 20 since August 2007. He shared many of the concerns of the other objectors especially in relation to the precedent effect of permitting the proposed extension. He considered that modification of the covenant would result in similar extensions becoming commonplace. He postulated that if at some future point in time the owner of his house could not be prevented from building an extension into his garden, the neighbouring garden which is already in shade from a large tree in the communal area, would suffer still less light. This situation could be alleviated by building an identical extension at No. 21, which together with the proposed extension to No. 7 would have a disproportionately detrimental effect on the Estate’s appearance.

41. He also considered that the proposed extension would comprise some 18 m2 of brick walls and will produce ‘both an aesthetic and practical cramping effect’. He additionally noted that the Estate had the advantage of a compact and symmetrical arrangement with light, space and greenery at a premium. Mr Kingsley appeared to have forgotten that there is existing brickwork and that the new, additional areas would be minimal by comparison.

Discussion

42. Notwithstanding the comments of Mr and Mrs O’Donnell and Ms Young, both sides agree that the proposed user is reasonable. It is an extension to a residential building in a residential Estate. It is further agreed that the covenant impedes the proposed user.

43. I will now return to the issues for the Tribunal to determine which I set out in paragraph 18. Putting aside the first issue for the moment, the next question to be considered is whether the restriction secures practical benefits to the objectors. Mr McNae, for the objectors said that the Company had, over time, worked to maintain the Estate’s unique character and appearance. It had long been recognised that the aesthetic was worth preserving and the removal of permitted development rights when the original planning permission was granted was recognition that the ‘coherent architectural character’ was worthy of protection.

44. The question of whether the proposed extension would disrupt that aesthetic is highly subjective. The sloping roof line is a feature that is not found at ground floor level elsewhere in the Estate and a roof concealed behind parapet brickwork would in my view have been a more elegant and fitting solution. I am mindful that the property is already larger than the other houses in the same terrace, the extension is small and occupies a site which is to some extent screened by shrubs in the adjacent flower bed. However, I am inclined to disagree with the Planning Officer that the extension is ‘sympathetic to the design of the original building, the terrace as a whole as well as the setting of the adjoining conservation area.’ The additional door in the frontage and sloping roof line are not features found elsewhere and although the Estate’s design ethos could be characterised as cohesive rather than uniform, I take the view that the extension will harm its visual appeal.

45. It is obvious that the restriction secures a practical benefit to the objectors since it is the means by which the original appearance of the Estate can be preserved and in this case prevents the implementation of the planning permission. But is that benefit of substantial value or advantage?

46. Mr Spibey, Ms Young and Mr and Mrs O’Donnell all said that they will have direct views of the proposed extension from their houses, implying a loss of visual amenity. In my judgement the scale and location of the proposed extension is such that any loss of amenity from the houses concerned will be negligible. Given the location of the extension I do not agree with Mr Kingsley’s contention that it will cause a ‘cramping effect’ in the Estate. The additional areas of brickwork will be insignificant given that there is already a brick-built flank wall on the site.

47. I now turn to what is usually termed ‘the thin end of the wedge’ but which might be better described as the setting of an unfavourable precedent. Many of the objectors were fearful that modification of the covenant would lead to a situation where the restriction is unenforceable and that more owners would seek to alter the size and appearance of their properties. Mr Skelly said that there was no such appetite amongst owners, and to Mr Spibey’s recollection there have been only two proposals which have involved additional floorspace.

48. In Shephard v Turner Carnwath LJ said:

“It is not in dispute that one material issue (often described as the "thin end of the wedge" point) may be the extent to which a proposed development, relatively innocuous in itself, may open the way to further developments which taken together will undermine the efficacy of the protection afforded by the covenants. In McMorris v Brown [1999] 1 AC 142, 151, the Privy Council adopted a statement by the Lands Tribunal from Re Snaith and Dolding's Application [1995] 71 P&CR 104. The applicants had been seeking modification of a covenant, to enable them to build a second house on a single plot within a building scheme. The President (Judge Bernard Marder QC) said: "The position of the Tribunal is clear. Any application under section 84(1) must be determined upon the facts and merits of the particular case, and the Tribunal is unable to bind itself to a particular course of action in the future in a case which is not before it... It is however legitimate in considering a particular application to have regard to the scheme of covenants as a whole and to assess the importance to the beneficiaries of maintaining the integrity of the scheme. The Tribunal has frequently adopted this approach....

49. Whilst the objectors may genuinely believe that modification is the first step on a path to the complete erosion of the design ethos that has underpinned the appearance of the Estate, it represents a misconception about the scope of the application and the order that the Tribunal has the ability to make. Regardless of the outcome of this application the restriction would continue to bind every other house in the Estate, and would continue to bind the property itself in its modified form.

50. Mr Skelly noted the words of the Deputy President of the Tribunal Martin Rodger QC, in Martin v Lipton [2020] UKUT 8 (LC) at [72]:

“Finally, it is necessary to reiterate what was said by the President of the Lands Tribunal in the passage cited by Carnwath LJ and quoted above: “any application under section 84(1) must be determined upon the facts and merits of the particular case”. Applications of this type are fact sensitive, and it cannot be assumed that the outcome of one case will be mirrored in the outcome of a different application, even one seeking a very similar modification on the same Estate”.

51. He went on to say at paragraph 73 that:

“The question which the Tribunal must now address is whether modifying the restriction to permit the proposed development is likely to open the way to further developments which, taken together, will undermine the efficacy of the protection afforded by the covenants from which the objectors benefit. If there is a significant risk that it may do so, and that the attractions of the Estate may thereby be jeopardised, the avoidance of that risk would be a practical benefit capable of being of substantial value or advantage to the objectors”.

52. I have already concluded that the proposed extension disturbs the original design philosophy of the Estate. Mr Cross asserted that there is very limited scope for a similar extension to the one he had proposed. Mr Spibey was concerned about potential porches but given the layout of the Estate I doubt that such alterations would be feasible as they would hinder the movement of vehicles and exacerbate the existing parking difficulties. It is possible that Mr Spibey himself could seek to extend over the single storey part of his house, but this would involve a property that is situated at the very periphery of the Estate and it would only be properly visible from Mr Cross’s house. I conclude that the scope to alter by extension, the street facing elements of any of the houses is very limited.

53. Greater scope exists to extend into gardens on the Estate. Most of the gardens are very constricted and extensions would potentially have an adverse effect on the amenity of neighbours. That the Council granted permission for a small, single storey extension at No. 10 in 2020 shows that there is potential for this type of alteration. The covenant prevented it from being built. The removal of permitted development rights offers some protection for owners, but the covenant ensures that the amenity currently enjoyed is protected by an additional layer of security. The same rationale can be applied to Nos. 20 and 21 which are situated in the middle of the Estate and the gardens of which are overlooked by most of the houses. In addition to a potential loss of amenity for the respective neighbours, extensions into the gardens of these properties would have a deleterious effect on the visual amenity for owners in the wider Estate, not to mention the possibility of harm to its character.

54. My conclusion, having considered the perceived practical benefits, is that modification of the covenant to allow the extension would encourage others to seek to extend their properties and increase the prospects of them being successful. A significant loss of amenity is a likely risk. The covenant in its existing form removes the element of uncertainty about what might be permitted in the future and provides assurance to owners that the form of the Estate will not be disturbed. In a densely developed Estate where outside space and light are at a premium it is clear to me that the covenant protects attributes that are worth preserving. It follows that the practical benefit conferred by the covenant is of substantial advantage and the requirements of section 84(1)(aa) are in my view not satisfied. I therefore have no jurisdiction to grant the modification.

|

|

|

Mark Higgin FRICSMember Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) |

|

|

|

Dated 27 January 2022 |

Right of appeal

Any party to this case has a right of appeal to the Court of Appeal on any point of law arising from this decision. The right of appeal may be exercised only with permission. An application for permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal must be sent or delivered to the Tribunal so that it is received within 1 month after the date on which this decision is sent to the parties (unless an application for costs is made within 14 days of the decision being sent to the parties, in which case an application for permission to appeal must be made within 1 month of the date on which the Tribunal’s decision on costs is sent to the parties). An application for permission to appeal must identify the decision of the Tribunal to which it relates, identify the alleged error or errors of law in the decision, and state the result the party making the application is seeking. If the Tribunal refuses permission to appeal a further application may then be made to the Court of Appeal for permission.