Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Martin v Lipton & Ors (RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - MODIFICATION) [2020] UKUT 8 (LC) (14 January 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2020/8.html

Cite as: [2020] UKUT 8 (LC), [2020] 1 P & CR DG25

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

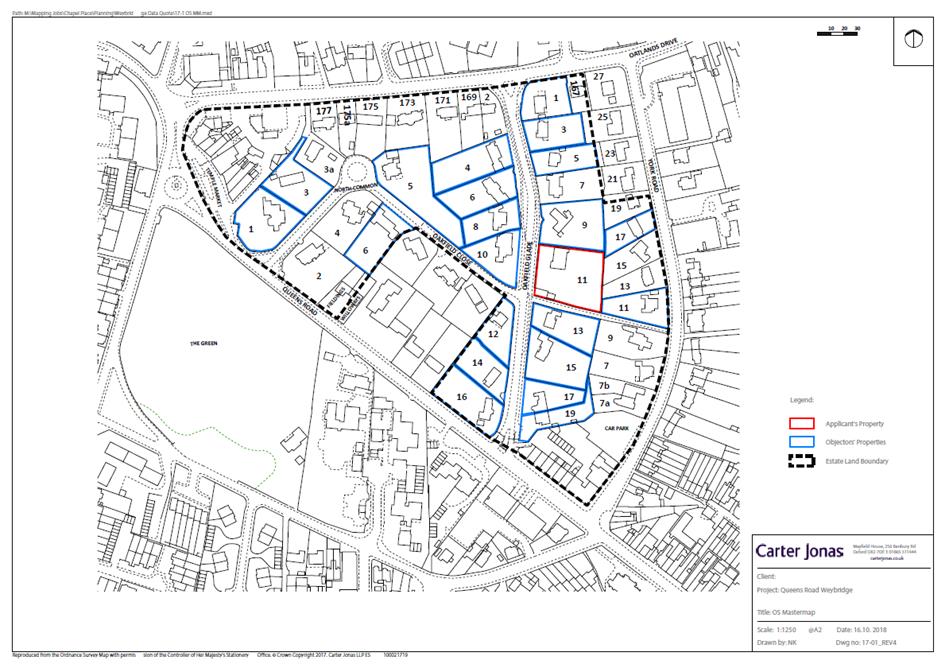

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER) |

|

|

Neutral citation number: [2020] UKUT 8 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LP/13/2018

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - MODIFICATION - restriction to one dwellinghouse per plot on small estate - modification sought to permit one additional house on largest plot - whether restriction secured practical benefit of substantial value or advantage - whether modification would set a damaging precedent - whether compensation payable for short term disruption caused by building works - application allowed - compensation for temporary disturbance payable to some objectors - Law of Property Act 1925, s.84(1)(aa) and (c).

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 84(1),

LAW OF PROPERTY ACT 1925

|

Between |

|

|

|

|

MR ANTHONY STEPHEN MARTIN and MR MICHAEL LIPTON and others |

Applicants

Objectors |

|

|

|

|

Re: Oak House,

11 Oakfield Glade,

Weybridge,

Surrey

Before: Martin Rodger QC, Deputy Chamber President and Paul Francis FRICS

Royal Courts of Justice

11-12 December 2019

Mr Jonathan Upton instructed by Dentons UK & Middle East LLP, for the applicant

Mr Andrew Skelly instructed by Hunters, solicitors, for 21 represented objectors

Mr Julian Adams, on his own behalf

The following case is referred to in this decision:

Shephard v Turner [2006] 2 P. & C.R. 28, [2006] EWCA Civ 8

Introduction

1. The Oakfield estate at Weybridge in Surrey is a residential estate of 44 properties laid out in 1928 and developed in the following years, whose original form has largely been preserved by covenants requiring that not more than one dwellinghouse be erected on each plot. This application under section 84(1), Law of Property Act 1925 seeks the modification of that restriction in relation to No.11 Oakfield Glade (known as Oak House) (HM Land Registry title SY537189).

2. The applicant, Mr Anthony Martin is the registered proprietor of No. 11 and wishes to build a detached two-storey house in its garden, while retaining the existing dwelling. Planning permission for the new house was originally granted on 13 December 2017. A second planning permission was granted on 18 July 2018 for a house of the same size and layout but with a modified façade.

3. The objectors are all owners of other houses on the estate. There are 26 of them in total (two others having withdrawn their original objections) each of whom is entitled to the benefit of the restriction imposed on the first sale of each property prohibiting the building of more than one house on any plot.

4. It is an unusual feature of this case, and an indication of the strength of feeling amongst the objectors to Mr Martin’s proposed development, that there has already been litigation between the parties in the High Court which confirmed that the restriction remains enforceable. Mr Martin did not actively oppose that conclusion and a declaration was duly made by Deputy Master Bartlett on 20 September 2017. The suggestion that changes on the estate might have made the restriction unenforceable appears to have been made by Mr Martin’s solicitors, prompting the High Court proceedings, but it has not featured in the argument before us.

5. At the hearing of the application Mr Martin was represented by Mr Jonathan Upton of counsel and expert evidence was given on his behalf by Mr Michael Tibbatts MRICS. Mr Martin also gave evidence.

6. Five of the objectors acted in person, of whom only Mr Julian Adams, the owner of 2 North Common, attended the hearing and made oral submissions. The remaining 21 objectors were represented at the hearing by Mr Andrew Skelly of counsel and relied on expert evidence given by Mr Thomas Grillo FRICS. Written evidence was filed by 18 of the objectors, of whom the following also gave oral evidence: Mr Richard Perry of 11 York Road; Mr Gareth Conyers of 10 Oakfield Glade; Mr Michael Lipton of 13 Oakfield Glade; Ms Chung Shune Mac of 8 Oakfield Glade; Mr Peter Cobham of 9 Oakfield Glade; Mr James Young of 15 Oakfield Glade; Mrs Frances Clemmow of 6 Oakfield Glade; Mr William Steward of 5 Oakfield Glade; Mrs Chung Chee Mac of 3 Oakfield Glade; and Dr Martin Vesely of 5 North Common. We have taken the evidence of all of the objectors, written and oral, into account in reaching our decision.

The Oakfield estate

7. The Tribunal visited the Oakfield estate on the day before the hearing, viewing No. 11 itself and other properties mentioned in the evidence. We looked at the site from the gardens and upper floors of its immediate neighbours, Nos. 10, 12 and 13 Oakfield Glade, and from No.11 York Road. We also looked at those parts of the estate where the restriction has not been observed and walked all of the estate roads and the footpath between Nos. 11 and 13.

8. The parties provided a plan showing the whole of the estate, which we include at the end of this decision. Some caution is required when referring to the plan as it does not show recent extensions to houses on the estate, many of which are significantly larger than they appear on the plan.

9. The estate is approximately triangular, being bounded by three main roads, York Road, Oatlands Drive and Queen’s Road.

10. York Road runs approximately north/south and forms the eastern boundary of the estate. Some commercial properties at the southern end of the road on its west side (within the estate boundary) are on land to which the restriction does not apply. The remaining properties on the west side of York Road are large detached house, with the exception of a pair of semi-detached houses at Nos. 7a and 7b. There are thirteen houses in all, of which nine are within the estate boundary (Nos. 7a to 17). Between Nos. 9 and 11 a public footpath runs west off York Road, towards the centre of the estate.

11. The northern boundary of the estate is formed by Oatlands Drive, a busy public road which runs approximately east/west. Seven houses on Oatlands Drive are within the estate, as are a petrol filling station and commercial properties at the western end. No.167 Oatlands Drive is a small detached house built in the garden of 1 Oakfield Glade in about 1993, apparently in breach of the restriction.

12. The third estate boundary is formed by Queen’s Road which runs approximately north-west/south-east linking the southern end of York Road to the western end of Oatlands Drive. There are small parades of local shops at each end of this stretch of road which are part of the estate but not bound by the restriction. Three houses on the estate have boundaries to Queen’s Road, Nos. 1 and 2 North Common and No. 16 Oakfield Glade, each a substantial detached house with a large garden. In 1975 two small detached houses (Fieldings, and Willoways) were built in part of the garden of No. 2 North Common, apparently in breach of the restriction.

13. The roads within the boundaries of the estate are private roads maintained at the expense of the residents. Oakfield Glade is the main estate road and runs north/south, parallel to York Road, with gates controlling access at both ends. There are 18 houses on Oakfield Glade, including Mr Martin’s house at No. 11. A second estate road, Oakfield Close, runs west off Oakfield Glade about half way along its length, becoming North Common before turning southwest and joining Queen’s Road. Dr Vesely’s house at 5 North Common has a large garden with a very long boundary to this road.

14. With very few exceptions the houses on the estate date from the inter-war period and are in the Arts and Crafts style. The 18 plots on Oakfield Glade are not of a regular size but most (especially those on the east side like No.11) are large approximately rectangular plots with the house placed towards the front, allowing a generous garden at the rear. The boundaries of most plots feature mature vegetation. Building heights and building lines are broadly consistent.

15. Most of the houses along Oakfield Glade have been extended significantly to the side and to the rear and, in some cases, into the roof space. As a result, many of the buildings span almost the entire width of the plot on which they stand, notable examples being Nos. 6, 8, 10 and 13 Oakfields Glade. This feature is not apparent from the plan provided by the parties and which we annex to our decision, but it was very clear when we visited the estate.

16. In their evidence a number of the objectors mentioned a sense of spaciousness as a particular attraction of the estate, but while that it is no doubt a feature of the large rear gardens, it was not the impression we formed of Oakfield Glade when viewed from the road. The houses are relatively close to the road and to each other and the hedges which separate them from the roadside verges are low enough to provide clear views of upper floors from the road and from houses opposite.

The application land

17. No. 11 Oakfield Glade is a large detached house on a prominent plot in the centre of the estate, opposite the junction of Oakfield Glade and Oakfield Close. The house itself was built in about 1930 (the conveyance imposing the restriction is dated 16 June 1930) and more recently it has been extended at the rear but not at the side. It occupies the largest plot on the estate (approximately 40 metres wide, making it twice as wide as some of the narrower plots, such as Nos. 5 and 8). The house itself is positioned close to the northern boundary, with its large garden on the southern side of the plot and towards the rear. A detached garage and workshop stand close to the southern boundary of the plot, connected to Oakfield Glade by a short stretch of drive. A semi-circular driveway also provides space for parking immediately in front of the house.

18. Mr Martin wishes to divide his plot into two equal parts and build a new house on the southern half, occupying the space currently used as lawn. The new house would appear bulkier than the existing No.11 to the north and No.13 to the south (but not noticeably taller than either of them). It would take in the footprint of the detached garage (which would be demolished) and would be served by the drive currently leading to it.

19. Mr Martin told the Tribunal he intended to implement the first of the two planning permissions he has obtained. Of the two designs the first is rather less in the Arts and Crafts style than he second, but it is not unique in that regard. No. 13 Oakfield Glade, the house next door, has been modernised and extended in recent years in a manner which makes few references to the prevailing style on the estate, as have others.

20. The proposed house has been referred to by the objectors as a four-storey building, but the Planning Inspector’s decision of 13 December 2017 described it in more precise terms as a detached two-storey house with additional accommodation in the roof and a submerged basement. It would not be the first house on the estate to feature either additional rooms within the roof space (No.13 Oakfield Glade, for example) or a basement, or both (No. 4 North Common).

21. A significant feature of Mr Martin’s plot at No.11 is the mature boundary planting. The hedge at the front of his house has been allowed to grow significantly taller than those in front of most other houses on the estate, while the hedge in front of the proposed site of the new house is taller still. The rear garden is surrounded by a fence, with tall, dense shrubs and a very tall beech tree lining the southern boundary, and a row of conifers and shrubs lining the eastern boundary which adjoins the gardens of Nos.11, 13, 15 and 17 York Road. The planting along the stretch of boundary which adjoins the garden of No.13 York Road (Mr Perry’s house) were supplemented in 2018 by a further row of conifers.

22. The immediate neighbours of No.11 are, on the eastern side, the four houses in York Road; on the southern side, No. 13 Oakfield Glade, which is separated from the garden of No.11 by the public footpath (about 4 metres wide) running between York Road and Oakfield Glade; on the northern side, No. 9 Oakfield Glade; and on the western side, on the opposite side of Oakfield Glade, Nos. 8, 10 and 12. Of these three properties only No. 10 is directly opposite No.11, with Nos. 8 and 12 being offset to the sides. No.12 is oriented on its plot so that the front of the house faces towards No.11.

The relevant statutory provisions

23. The application is made in reliance on grounds (aa) and (c) of section 84(1) of the 1925 Act.

24. Ground (aa) requires that, in the circumstances described in subsection (1A), the continued existence of the restriction must impede some reasonable use of the land for public or private purposes. Satisfaction of subsection (1A) is a requirement of a successful application based on ground (aa); it provides as follows:

(1A) Subsection (1)(aa) above authorises the discharge or modification of a restriction by reference to its impeding some reasonable user of land in any case in which the Upper Tribunal is satisfied that the restriction, in impeding that user, either-

(a) does not secure to persons entitled to the benefit of it any practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to them; or

(b) is contrary to the public interest,

and that money will be an adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which any such person will suffer from the discharge or modification.

25. When considering whether sub-section (1A) is satisfied, the Tribunal is required by section 84(1B) to take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permission in the area.

26. Ground (c) permits the Tribunal to modify a restriction where it is satisfied that the proposed modification will not injure the person entitled to the benefit of the restriction.

27. When the Tribunal makes an order modifying or discharging a covenant under section 84(1) it may direct the applicant to pay a sum of money to an objector by way of consideration to make up for any loss or disadvantage suffered by that person as a consequence of the modification or discharge. The measure of compensation under section 84(1) is such amount as the Tribunal may think it just to award.

The expert evidence

28. The expert evidence provided by Mr Tibbatts on behalf of the applicant and Mr Grillo on behalf of the objectors was of very limited value to the Tribunal.

29. Mr Tibbatts’ evidence that there would be no adverse impact on the amenity of neighbouring occupiers, nor diminution in value of their properties, was not based on relevant observation and was largely speculative as he had not sought permission to inspect any of the objectors’ homes or gardens. His suggestion that the “climate” of feeling between Mr Martin and his neighbours would not have permitted an inspection ignored the obligation on those participating in Tribunal proceedings to cooperate with the Tribunal and with each other to ensure the proceedings are properly prepared. Had it been asked to do so, and had it been asked, the Tribunal would have directed that facilities for all appropriate inspections should be made available to the experts by all participants. As it was, Mr Tibbatts was seeing No.11 from the gardens and windows of the surrounding properties for the first time when he accompanied the Tribunal on its inspection on the day before the hearing, six months after preparing his report. He also chose not to express a view on the value of any of the objectors’ properties.

30. Mr Grillo had at least viewed the development site from the neighbouring gardens and had taken some photographs, including some useful views from the upper windows of No. 11 York Road, and No. 13 Oakfield Glade. His evidence on the practical consequences of the proposed development was expressed in general and sometimes extravagant terms; he suggested, for example, that the new development would have an adverse effect on all of the objectors because it would “degrade the quality of the estate”, but the evidence that this would be so, after building work was complete, amounted to little more than the consequences of the additional traffic generated by one extra household.

31. Mr Grillo did not attempt to value the objectors’ properties and suggested it was “not practical” to provide a meaningful assessment of the possible diminution in value which might be caused by the development. He did provide some evidence based on a comparison between the purchase price of No. 10 Oakfield Glade and the purchase price of houses in other parts of Weybridge from which he deduced that the modification of the restriction and construction of the new house would reduce the value of No. 10 by 9.8% or £230,000. From this he ascribed a reduction in the value of Nos. 6, 8, 12, 13 Oakfield Glade of 5%. We found this evidence flawed and unhelpful. Mr Grillo was unable to explain what his current valuation of No. 10 was based on (it may have been the price paid by the current owner for the un-extended property in 2008 indexed to the date of his report, or it may have been a property elsewhere in Weybridge). He could not explain the table used to support his conclusions which, in any event, was arithmetically incorrect. He provided no valuation of any property other than No. 10, so his suggestion of a 5% diminution in value for neighbouring houses was impossible to translate to a sum of money which might be awarded in compensation.

32. We have taken into account the expert evidence in undertaking our own assessment of the impact the modification of the restriction on the amenity of the estate. Without meaningful evidence we are unable to form a view of the value of any of the objectors’ properties, nor would we be able to quantify any diminution in value if appropriate.

Ground (aa)

33. All parties agree that the building of an additional house in the garden of No.11 is a reasonable use of that land, and that it is impeded by the restriction. The main issue on ground (aa) is whether, by impeding that reasonable use of the garden of No.11, the restriction secures for the objectors a practical benefit of substantial value or advantage.

34. In their written evidence each of the objectors identified the practical benefits which they considered the restriction secures for them. Many of the points they made overlapped and in his skeleton argument Mr Upton drew them together in a list which Mr Skelly agreed was an accurate summary. Some of the perceived benefits flowed from the avoidance of the short-term disruption which would be caused during the works themselves, while others were concerned with the prevention of a permanent change to the appearance of the estate and the detrimental effect on the enjoyment of individuals’ homes caused by the construction of a new house in the centre of the estate. A major concern which featured in the evidence of almost all the objectors was the effect a modification of the restriction on No.11 might have on future applications to modify or release the restrictions on other plots, often referred to as the “thin end of the wedge” argument.

35. Apart from protection in the short term against excessive noise, disturbance and parking by contractors’ vehicles, the long term benefits of the restriction which were identified in the evidence were the following: the protection of views from gardens; the protection of greenery and trees; not being overlooked; not feeling overcrowded; the maintenance of the character of a low density residential neighbourhood and protection against noise and bustle from the occupation of an additional dwelling.

Long term benefits

36. We will begin by considering the long-term benefits of maintaining the restriction.

37. Each of the matters relied on by the objectors is capable in principle of being a practical benefit of the restriction. In practice, however, we do not consider that the proposed development will have the serious adverse consequences feared by the objectors.

38. In this case the protection of views from gardens and the protection of greenery and trees are two sides of the same coin; they may also conveniently be considered alongside the proposition that the preservation of the restriction benefits the objectors by preventing them from being overlooked.

39. At present there are no significant views into the garden of No.11 from the gardens of adjoining properties because of the dense boundary planting; views of the garden from the upper floor front windows of Nos. 10 and 12 Oakfield Glade and from the rear windows of No. 11 York Road are also entirely of foliage.

40. The objectors’ fear is that the construction of a new house in the garden of No. 11 will result in the loss of the seclusion and views of foliage and trees which they now enjoy and their replacement with views of, and from, the new house itself. That concern has not been allayed by the plans for which planning consent has been obtained, which show the boundary planting as being retained, nor by the views of the planning inspector, whose appeal decision of 13 December 2017 considered this issue. In paragraph 8 of the inspector’s decision he said that while the new house “would have some negative effects in terms of the setting of the existing property [i.e. No.11 itself] and the overall street scene”, the retention of the existing boundary vegetation “would maintain the leafy and secluded nature of the road and reduce the prominence of the new building.”

41. A number of the objectors expressed concern that the construction of the new house would require the removal of much of the boundary planting or would put it at risk of damage. Mr Grillo, the objectors’ expert, suggested that the hedge fronting Oakfield Glade would have to be taken out during construction and that the beech tree in the rear garden would be “vulnerable”. He also thought it possible that other trees or shrubs would be removed by the owners of the new house to enlarge the usable area of their garden.

42. We are satisfied that most of these concerns are unrealistic. Mr Martin intends to move to the new house once it is constructed and he told us that he wishes to make it his family’s home for the long term. We see no reason to doubt that he, or any subsequent purchaser of the new house from him (however soon a sale might occur) would value the mature planting on the boundaries of the garden and would wish to maintain it. It is visually attractive and helps to isolate the garden from views of neighbouring buildings. It will perform the same function when the new house is built and no convincing reason was advanced why an owner would prefer to remove it.

43. Because of its position in the garden of No. 11 the construction of the new house will not require the removal of much of the existing boundary foliage. The shortest distance between the southern boundary fence and the southern flank wall of the new building will be 2.4 metres, widening to 4.1 metres towards the rear of the building. This stretch of boundary separates the garden from the adjoining public footpath, and the space between the garage and the close boarded boundary fence is currently filled by a bank of hedging. Some of the hedging may be thinned or removed altogether to allow demolition of the garage and the construction of the new house, but there will be ample space for it to be replanted if necessary. We also think it likely that the existing conifer screen at the front of the site will be thinned to allow the installation of a new fence between the existing No.11 and the new building (as shown on the tree protection plan). Some of the hedge will probably be lost where it adjoins the current drive providing access from Oakfield Glade to the garage if, as we expect, the entrance is widened when it becomes the sole point of entry to the new drive.

44. As for damage to foliage sustained during the construction phase, the tree protection plan submitted as part of the planning application shows where protective fencing will be installed to guard against collision damage or soil compression. The shrubs in the rear garden and the root structure of the beech tree will be protected in this way and, given the distance between the beech tree and the building footprint, we regard the suggestion that it will be “vulnerable” as unjustified.

45. Mr Tibbatts suggested that construction traffic would park at the rear of the site, gaining access between the existing house and the new development. We think this very unlikely, but if it were to be the case it would probably be necessary to remove additional hedging which screens the drive of No.11 from the garden. That stretch of hedge is perpendicular to Oakfield Glade and provides very little screening from the view point of neighbouring houses. It would, in any event, be likely to be regarded by the residents of both No.11 and the new house as in their interests to restore it once the work has been completed.

46. Our overall conclusion is that only modest sections of the existing boundary planting are likely to be removed during the construction phase, and that no significant boundary features will be required to be removed permanently to accommodate the new building and its foundations.

47. It is also relevant to mention that the planning permission is conditional on the approval of a further arboricultural plan and method statement and requires the retention of existing trees identified in the plan for five years from first occupation of the new house and the replacement of any which are damaged or die. Additionally, Mr Martin has proposed that any order modifying the restriction should be conditional on his agreeing not to remove any trees or shrubs other than as necessary during construction. There are issues with the enforcement of such a condition and this one overlaps substantially with the conditions to which the planning permission is already subject. We will return to the issue of conditions at the end of this decision.

48. For all of these reasons it is necessary to assess the impact which the new house will make on the visual amenity of its immediate neighbours on the basis that boundary foliage will remain substantially as it is at present.

49. There will be no significant view of the new house from the windows of Nos. 9 and 13, its immediate neighbours to the north and south, as No. 11 itself will block the view from No. 9 and there are no windows in the flank wall of No. 13. Mr Cobham, the owner of No. 9, did not mention a concern that his own garden would be overlooked in his evidence. We do not doubt the sincerity of Mr Lipton, the owner of No. 13, who told us in his written evidence that the new building would overlook his house so severely that it would leave him with no privacy in his garden making it necessary for him to move. We agree with the planning inspector’s assessment that, standing in Mr Lipton’s rear garden, the upper floor and roof of the new house would be visible to some extent notwithstanding the boundary vegetation. But we also agree with the inspector that little harm is likely to be caused to the amenity of the residents of No. 13 whose garden is already overlooked from the side by No. 15. They will not have a sense of being directly overlooked because of the significant screening which will remain, because the public footpath separates their garden from that of No. 11, and because the new building will be to the side of theirs. In our judgment the garden of No. 13 will not be materially less private than it currently is.

50. On the eastern side, the garden of No.11 abuts the gardens of Nos. 11, 13, 15 and 17 York Road. The owners of 15 and 19 are not objectors, and no witness statement has been filed explaining the views of Mr Allan and Ms Watkins, the owners of No. 17.

51. Mr Perry, who owns No.11 York Road, feared being directly overlooked by the new property which he considered would have a significant impact on his and his family’s privacy and enjoyment of their garden. His feelings on the subject are clearly genuine, but we do not think they are realistic. The view of the new house from the garden and upper windows at the rear of No. 11 York Road will be partially obscured by existing boundary yew trees and other large shrubs which will remain in the garden of No. 11 and more completely, when it is in leaf, by the substantial beech tree. In time, 12 conifers recently planted by Mr Martin will grow up to provide additional screening. The rear elevations of the two houses will be separated by a distance of at least 50 metres and, at its closest point, Mr Perry’s garden will be about 25 metres from the new building with a close boarded fence and substantial mature and more recent planting blocking the view. We do not suggest that he and his family will be unaware of the presence of the new building; they will no doubt have some glimpses of it, as they already have of other neighbouring properties, but we have no doubt that Mr Perry’s fears of being visually dominated will not come to pass. It is likely that the screen of conifers will, in time, be much more intrusive, denying the garden the benefit of the variety and depth of planting in the garden of No. 11, but the restriction does not provide protection against such planting and Mr Martin was quite entitled to install it.

52. On the west side of the application site, Nos. 10 and 12 stand on the opposite side of Oakfield Glade. Neither has much garden of significance at the front of the house and the concern of the owners in each case is that they will have direct views of the new house from their first-floor bedroom windows.

53. Mr Conyers, the owner of No. 10, said in his written evidence that he would lose the view he currently enjoys of the beech tree in the garden of No. 11 which would be replaced in his line of sight by the upper floor and roof of the new building. We have no doubt that Mr Conyers is correct, and that the outlook he enjoys when he gets out of bed in the morning will change in the manner he describes, but we find it difficult to regard the practical benefit of preserving that outlook as being of substantial value or advantage. Mr Conyers’ house is directly opposite No. 11 which, together with No. 13, already frames his view of the proposed building plot for anyone standing at his window. He explained that he enjoys the view while lying in bed and it is probably the case that the adjoining properties, or at least No. 11, would be out of his line of sight from that position. Enjoyable though his experience of the view while lying in bed may be, we doubt Mr Conyers spends much of his time in contemplation of the view between Nos. 11 and 13. The planning inspector considered that the proposed development would not harm the living conditions of the occupiers of No. 10 in terms of outlook, privacy or light any more than No. 11 already does. We substantially agree with that conclusion.

54. Due to the oblique angle at which it is built, the view from the first-floor windows at the front of No.12 is also of the high hedges screening the garden of No. 11 on the opposite side of the road, with No. 11 itself in the background and No. 13 to the right. No. 12 is a smaller house than most in the road and it is let out by its owner. We do not think the introduction into the view of a new building between Nos. 11 and 13 will harm the visual amenity of residents of No. 12 to any meaningful extent.

55. The next practical benefits said to be secured by the prevention of the proposed development in the garden of No. 11 are not feeling overcrowded and the maintenance of the character of a low density residential neighbourhood. We can conveniently consider these together and state our view briefly. We have already described our impressions of Oakfield Glade. The proposed site is the only significant portion of the street scene which has not yet been developed on the original building line. The erection of the new house will complete the stretch of properties running more or less continuously, with only modest separation distances, along the whole of its eastern side. Although it will bring about a change, we do not think that change will make any significant difference to the character of the estate or to the enjoyment of it by residents. The new house will be another substantial dwelling in a substantial garden, and we agree with the view of the planning inspector that it will be consistent with the rest of the road, and it will not look intrusive or exceptional.

56. The final practical benefit mentioned by objectors was protection against noise and bustle from the occupation of an additional dwelling. The proposed new house will be one more in a street of 19 units on Oakfield Glade (No. 2 is divided into two flats). Mr Martin’s evidence was that he will live in it and that his current house at No.11 will be sold. No.11 is a large family house and it may come to be lived in by a large family, but we do not consider there to be any substantial advantage to the current residents of the estate in preventing the “noise and bustle” of one additional home. The restriction does not secure tranquillity. Any one of the original houses on the estate might be occupied from time to time by an exceptionally boisterous family, or might become the home of a mute contemplative. The restriction does not protect, nor was it intended to protect, the occupants of the estate against the ordinary consequences of life in a low density residential neighbourhood.

57. To the extent that preventing the construction of a new house in the garden of No. 11 secures practical benefits for the other residents of the estate, our conclusion is that these are not benefits of substantial value or advantage whether looked at individually or cumulatively.

58. We have considered whether compensation is required in consideration of any loss or disadvantage suffered by any of the objectors as a consequence of the modification of the restriction. As regards the longer term changes which will be brought about if the new house is built, we have been provided with no meaningful evidence which we could use as a base line for an assessment of any diminution in value of any of the adjoining properties. Had we found that a diminution in value had been sustained we would have considered whether to invite additional evidence to enable us to quantify it but, in the event, we are satisfied that none of the objectors will sustain any loss in the value of their property as a result of the construction of a new house at No. 11. The objectors’ homes will be no less attractive to purchasers than they now are. Nor do we consider that the modest changes in the immediate surroundings of the houses which most closely neighbour the new house will cause a meaningful loss of amenity such as to require compensation.

Short term consequences

59. There was no dispute that during the construction of the new house at No. 11 the immediate neighbours, and others on what is quite a small estate, will experience short term disturbance in the form of the noise of the works themselves, dust and mud on the estate roads, additional traffic including heavy vehicles and machinery required for the excavation of the basement beneath part of the new building, and damage to roadside verges and possibly to the roads themselves.

60. There was an uninformed debate about the likely duration of the disturbance. In his written evidence Mr Grillo said the project would take “up to a year or more”, and elsewhere “probably two years”. Mr Martin said he had been told by the architect who prepared the design that if a professional builder was engaged to undertake a project of this scale completion within 12 months should be “perfectly achievable”. Mr Tibbatts formed no independent view of his own.

61. The most useful evidence on the likely duration of the development of the site was supplied by Dr Vesely, the owner, together with his wife, of No. 5 North Common. The property opposite his, No. 4, has recently been demolished and reconstructed. The new two storey house built on the site includes an excavated basement and accommodation in the roof space and had taken 18 months to complete. The road leading to his house had regularly been obstructed, delaying him and his family in coming in and out. At the busiest time of the project, the final fit out, there would sometimes be six or seven vehicles parked in the road. The grass verges had been destroyed and later replaced by the contractors, but the road itself had not been damaged. Dr Vesely had usually been absent at work when building operations were going on but there had been times when he was at home and he was able to confirm, as one would expect, that the works had been noisy.

62. The only reason why the new house proposed by Mr Martin might be completed more rapidly than the new house at 4 North Common is that it will not be necessary first to demolish and remove a substantial building from the site. In the absence of other evidence, we will nevertheless assume that the work will take about 18 months and that similar disruption will be caused to the immediate neighbours of No. 11 Oakfield Glade as was experienced by Dr Vesely and his family. The noisiest work is likely to occur at an early stage, during the excavation for the new basement, and the peak in term of contractors’ vehicles is likely to occur towards the end, when electrical wiring, kitchens and bathrooms are being installed, the property is being decorated and carpets, curtains and other finishing off is taking place.

63. Whether protection from the disturbance likely to be caused by a development project was capable of being a practical benefit of substantial value or advantage such as to justify a refusal of an application for the release or modification of a restriction which impedes the development was considered by the Court of Appeal in Shephard v Turner [2006] 2 P. & C.R. 28, [2006] EWCA Civ 8. Having reviewed a number of decisions of the Lands Tribunal in which more or less weight had been given to temporary disturbance, Carnwath LJ said this at [58]:

“In my view, account must be taken of the policy behind paragraph (aa) in the amended statute. The general purpose is to facilitate the development and use of land in the public interest, having regard to the development plan and the pattern of permissions in the area. The section seeks to provide a fair balance between the needs of development in the area, public and private, and the protection of private contractual rights. "Reasonable user" in this context seems to me to refer naturally to a long term use of land, rather than the process of transition to such a use. The primary consideration, therefore, is the value of the covenant in providing protection from the effects of the ultimate use, rather than from the short-term disturbance which is inherent in any ordinary construction project. There may, however, be something in the form of the particular covenant, or in the facts of the particular case, which justifies giving special weight to this factor.”

64. The particular restriction in issue in this case is not aimed specifically at the prevention of disturbance; it is a density restriction designed to limit the number of houses which may be constructed on the estate. Its purpose is not to offer protection against the temporary consequences of development. In our judgment the disturbance which will be experienced, including by the most immediate neighbours of No. 11 in Oakfield Glade, will not be intolerable and protection from it is not a practical benefit of substantial value or advantage. On the other hand, the development will be intrusive and quite protracted and the disturbance to immediate neighbours calls for modest compensation which we will assess later in this decision.

The “thin end of the wedge”

65. We come finally to the issue on which greatest stress was laid by the objectors in their evidence and submissions. Their concern is that the modification of the restriction in this case will establish a damaging precedent and will materially change the physical and legal context in which any future applications for modification will be determined. They contend that, for those reasons, the retention of the restriction in full force confers a practical benefit of substantial value or advantage to its beneficiaries.

66. In Shephard v Turner Carnwath LJ acknowledged the materiality of these concerns, at 26, as follows:

“It is not in dispute that one material issue (often described as the "thin end of the wedge" point) may be the extent to which a proposed development, relatively innocuous in itself, may open the way to further developments which taken together will undermine the efficacy of the protection afforded by the covenants. In McMorris v Brown [1999] 1 AC 142, 151, the Privy Council adopted a statement by the Lands Tribunal from Re Snaith and Dolding's Application [1995] 71 P&CR 104. The applicants had been seeking modification of a covenant, to enable them to build a second house on a single plot within a building scheme. The President (Judge Bernard Marder QC) said:

"The position of the Tribunal is clear. Any application under section 84(1) must be determined upon the facts and merits of the particular case, and the Tribunal is unable to bind itself to a particular course of action in the future in a case which is not before it… It is however legitimate in considering a particular application to have regard to the scheme of covenants as a whole and to assess the importance to the beneficiaries of maintaining the integrity of the scheme. The Tribunal has frequently adopted this approach….

Insofar as this application would have the effect if granted of opening a breach in a carefully maintained and outstandingly successful scheme of development, to grant the application would in my view deprive the objectors of a substantial practical benefit, namely the assurance of the integrity of the building scheme. Furthermore I see the force of the argument that erection of this house could materially alter the context in which possible future applications would be considered." (p 118)

67. Before considering this aspect of the objectors’ case there are two preliminary points which deserve to be stressed, in light of misconceptions which featured in the evidence of some of the objectors and their expert, Mr Grillo.

68. It appeared to be Mr Grillo’s understanding that the effect of the modification of the restriction binding No. 11 would be that the same restrictions would thereafter be unenforceable throughout the estate. In his report he suggested that if the restriction was removed “one can envisage two or more plots being combined and perhaps three or four houses in diminished gardens being built, or indeed low quality semi-detached houses or blocks of flats.” Later he explained the difficulty he had in assessing the diminution in value of the objectors’ properties by saying that it was “not practical to carry out a full valuation exercise on any one house on the Estate to compare its value with a similar house having all the advantages of those on the Estate with the one exception that the neighbouring house might be converted into flats or otherwise developed more densely.”

69. It was also apparent from the evidence of the objectors that many feared the consequence of modification would be that the protection afforded by the scheme of restrictions binding properties on the estate would be lost. Mr Conyers’ witness statement was typical in urging that the application should not be permitted “because then the Covenant becomes worthless for the genuine long-term residents in the road.” To the same effect was the evidence of Mrs Mac: “If the covenant can no longer be upheld, then we will be inundated with even more property developers who will view properties for sale as an unrestricted opportunity to build inappropriately high-density buildings purely for profit, without any regard for protecting our surroundings.”

70. These obviously sincere concerns on the part of objectors reflect a misunderstanding of the scope of the application and of any order the Tribunal is empowered to make. The sole application under consideration is in relation to No. 11 Oakfield Glade and is to permit one additional detached house on the largest plot on the estate. Subject to that modification the restriction would continue to bind No.11. It would also continue to bind each and every other plot on the estate to which it currently applies.

71. The second preliminary point which needs to be made is that the “thin end of the wedge” argument raises issues of fact, not of law. That point was emphasised by Carnwath LJ in Shephard v Turner, at [29], after he had explained that the specific effects of a proposed modification on the integrity of a scheme of covenants “would depend on the nature of the particular proposal in the future, which in turn would be subject to detailed control by the planning authority and the Tribunal.” At times during Mr Skelly’s closing submissions the possibility that success for this application would be the “thin end of the wedge” was deployed as if it was an argument in its own right which did not need to be developed or related to the facts. Without attention to the facts, and an assessment of potential consequences of the particular modification being sought which is rooted in those facts, the thin end of the wedge is no more than a slogan.

72. Finally, it is necessary to reiterate what was said by the President of the Lands Tribunal in the passage cited by Carnwath LJ and quoted above: “any application under section 84(1) must be determined upon the facts and merits of the particular case”. Applications of this type are fact sensitive, and it cannot be assumed that the outcome of one case will be mirrored in the outcome of a different application, even one seeking a very similar modification on the same estate.

73. The question which the Tribunal must now address is whether modifying the restriction to permit the proposed development is likely to open the way to further developments which, taken together, will undermine the efficacy of the protection afforded by the covenants from which the objectors benefit. If there is a significant risk that it may do so, and that the attractions of the estate may thereby be jeopardised, the avoidance of that risk would be a practical benefit capable of being of substantial value or advantage to the objectors.

74. There is no doubt that the estate is of considerable interest to developers and the objectors told us they regularly receive unsolicited inquiries from companies who wish to acquire land on the estate. Even where not stated explicitly, the reasonable assumption in all of these cases is that the prospective developers see the potential either to build in the gardens of existing properties, or to demolish them in order to make more intensive use of their generous plots. There is also evidence of some serious applications for planning permission for development which would be in breach of the restriction. In 2009 an application for permission to demolish the existing houses at 171, 173 and 175 Oatlands Drive and build 10 houses was withdrawn after opposition from local residents. A proposal to build a block of flats on the site of 7-9 York Road was also considered but not pursued (instead 2 houses, 7a and 7b York Road, were built in the garden of 7 York Road). Reference was also made by Mr Adams to a proposal to convert the existing detached house at No. 1 North Common into three flats which had not proceeded after the new owner was reminded of the existence of the restriction.

75. A number of relevant points emerged from the evidence. The first is that the proposed modification would not be the first departure from the one dwelling per plot principle which the restrictions impose on all of the plots on the estate. Since the imposition of the restrictions, 2 North Common has been sub-divided to create 2 additional small detached houses, 1 Oakland Glade has been subdivided to create an additional dwelling on Oatlands Drive (167 Oatlands Drive), 2 Oakfield Glade has been converted into two flats, and 7 York Road has been sub-divided to create 3 properties, Nos. 7, 7a and 7b.

76. There is no suggestion that any of these breaches of the scheme of covenants was authorised by the Tribunal, yet on behalf of the applicant it was not argued by Mr Upton (or at least not with any conviction) that the fact that they had occurred in the past was of much importance to the outcome of this application. The objectors rightly drew attention to the fact that each of the infringements of the principle that there should be only one dwelling on each plot was on land on the fringes of the estate. The character of Oatlands Drive and Queens Road is very different from the central parts of the estate along its private roads. Despite its address in Oakfield Glade, the building at No.2 which has been converted into flats fronts onto Oatlands Drive, and the detached house in the garden of No. 1 is also on the same busy public road. Having viewed each of these infringing properties, we are satisfied that they have not damaged the integrity of the original pattern of restrictions.

77. It is also relevant that the proposed modification is, in our judgment, entirely in keeping with the original pattern of development on the estate. If the new house is completed it will be difficult for someone unfamiliar with the conveyancing history of the estate to identify which two adjoining properties on Oakfield Glade stand on what was originally a single plot. That is the consequence of the size of the plot on which No. 11 stands, and the variability of the size of other plots, but it means that a modification will not introduce an alien or incongruous element into the layout of the estate. This is not an application to build a house on back land, let alone a block of flats, a retirement home or a terrace of small town houses, each of which was mentioned as a risk by Mr Grillo and the objectors.

78. The scope for any further development which would infringe the one house per plot principle without changing the appearance of the estate for the worse or introducing a new style of building is distinctly limited. The only obvious candidate in the central part of the estate is in the garden of 5 North Common , which is large enough to accommodate an additional house on land fronting one of the estate roads. Dr Vesely, the owner of No. 5, is opposed to any such development, but it is appropriate to have regard to the possibility that he might change his mind or that a future owner may take a different view. While we emphasise that our current view will have no impact on any future application which may come before the Tribunal, we consider there is a realistic prospect that an application to modify the restriction currently binding No. 5 North Common would have some prospect of success. On the other hand, the features it shares with the application land with which we are currently concerned (i.e. it’s very large garden and direct access on to an estate road) mean that a development there would make little impact on the general appearance or character of the estate. It is also the case that the two houses immediately opposite the potential development plot are not within the estate and do not have the benefit of the restriction (although we appreciate that No. 6 North Common , and at least Nos. 6, 8 and 10 Oakfield Glade, would also be neighbours to any such development). Taking all of these matters into consideration, we do not think the modification of the restriction in the manner requested by Mr Martin will materially affect the prospects of a successful application to permit an additional house in the garden of No. 5 North Common.

79. The only other property where there is any possibility of development fronting on to one of the estate roads (without demolishing an existing building) is at No. 12 Oakfield Glade. This occupies a corner plot and the house is noticeably smaller than others on the estate. The plot is about a third of the size of the plot on which No. 11 currently stands and its subdivision would allow space for only a small house which would be vulnerable to the suggestion that it was out of keeping with the core part of the estate. We do not think the modification of the restriction to permit an additional house at No. 11 would materially increase the prospects of success of an application to squeeze a further house into the garden of No. 12.

80. There is greater development potential outside the central core of the estate, in the gardens of No. 16 Oakfield Glade and No. 2 North Common. . Both of these properties have long gardens which border Queens Road. The garden of No. 2 North Common was developed for two new houses in the 1970s but probably remains large enough for another to be added. We do not consider that the potential for development of a small number of additional homes on sites peripheral to the estate is material. Just as the non-core developments which have already taken place do not provide a precedent of relevance to this application, so the success of this application would not increase the prospect of success of any further applications for modification to permit development round the outskirts of the estate.

81. It was suggested by Mr Conyers that there was space to insert a new house at the side of No. 9 Oakfield Glade, but we do not agree with that assessment. Any such development would have to be at the back of the plot, and would not fit between No. 9 and its neighbour, No. 11. Such back-land development would raise very different issues.

82. We have considered but discounted the risk that success for the current application might lead to a greater risk of back-land development, the replacement of existing single detached houses with two or more smaller houses on a single plot, the amalgamation of plots to secure development at a greater density, or the possibility of blocks of flats or terraced housing. There is no doubt that many plots on the estate are large enough to be more intensively developed, but any such development would involve a radical departure from the principle on which the estate was laid out. In our judgment the prospect of securing a modification of the restriction to permit any of these forms of development would be no greater whatever conclusion we reached on Mr Martin’s application for one additional detached house in the garden of No. 11, fronting the estate roads and consistent in design, scale and position with the existing properties on the estate.

83. Finally, we have considered a factor mentioned by the objectors in their solicitors’ correspondence and in some of their evidence, namely that a successful outcome to this application will encourage other applications and intensify pressure from developers, while at the same time diminishing the resolve of the objectors to resist. We do not underestimate the financial and emotional drain which proceedings between neighbours can give rise to, but we do not consider the avoidance of these sorts of pressures is a practical benefit secured by the restrictions. The evidence shows that interest from developers is already acute, and we see no reason why it should not continue to be resisted by those residents who wish the estate to remain as it is. Residents who might be more attracted to the prospects of development are already in a position to make an application under section 84 if they consider it has a sufficient prospect of success. Every owner of a home on the estate has had that right since 1928 when the estate was first laid out, and we do not consider that discouraging others from exercising their right to make such an application is a benefit secured by the restriction.

84. For these reasons we are satisfied that the integrity of the original pattern of covenants will not be materially undermined by the modification which we are now asked to make. Nor will it materially alter the context in which any future application in relation to a different part of the estate would fall to be considered.

85. The requirements of section 84(1)(aa) all having been satisfied, we have a discretion, which we will exercise, to permit the proposed modification.

86. The application having succeeded on the basis of ground (aa), it is not necessary for us to consider the higher hurdle presented by ground (c).

Compensation

87. We have dealt in paragraphs 63 and 64 above with the principle that compensation may be payable to reflect temporary disturbance caused by the proposed works. Bearing in mind our conclusion that it is unlikely the rear garden of the new plot will realistically be used for the parking of contractors’ vehicles, we do think that parking on and disturbance to roadsides and grass verges will inevitably be significant and will particularly affect (in addition to No. 11 itself) Nos. 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 and 15. Of these properties, No. 10 is likely to be the worst affected by parking, and by vehicles negotiating access to and egress from the site. Further, Nos. 10 and 13 can be expected to be affected more by on-site noise than any of the other nearby houses.

88. We therefore determine that the owners of Nos. 8, 9, 12 and 15 should be paid £2,000 each, with No 10 receiving £4,000 and No. 13 receiving £3,000 as compensation for such disturbance as they may suffer. Disturbance to other objectors is likely to be negligible and no compensation is therefore awarded to them.

Other conditions

89. In correspondence shortly before the hearing Mr Martin offered to accept a modification of the restriction subject to a number of conditions. That offer was repeated by Mr Upton on Mr Martin’s behalf.

90. The purpose of the conditions was to alleviate concerns about temporary disruption, changes to the design of the development and the removal of vegetation. It was proposed that any modification should be on condition that:

a. Mr Martin should, make good at his own expense any damage caused to “the approach road, grass verges and areas immediately surrounding the access to the existing garage” during the proposed construction works. It was suggested that a schedule of condition of the relevant areas be prepared by the parties’ experts and supported by photographs.

b. No more than 3 vehicles at a time belonging to contractors or their employees should be permitted to be parked on the common parts of Oakfield Glade during the construction of the development.

c. Except where the footprint of the new house requires vegetation to be removed to allow for its construction, the existing boundary and perimeter landscaping surrounding the application land will not be reduced (other than being trimmed and maintained in the usual way).

d. The only house permitted to be built on the application land should be the development permitted under the grant of planning permission in appeal reference APP/K3605/W/17/3181923.

e. The only access to and egress from the site for the new house following its completion should be via the current route immediately adjacent to the public footpath.

91. These proposed conditions were not greeted with enthusiasm by the objectors, who raised a great many questions in a response from their solicitors on 30 November. We share their scepticism and having already concluded that compensation is appropriate for those likely to be most affected by the temporary disturbance caused by the works, we do not consider further conditions to be appropriate. In his own interest Mr Martin is likely to require his contractors to make good damage they cause. A condition restricting temporary parking by third parties is unlikely to be easily enforceable. The planning permission already includes a condition for reinstatement of lost or damaged vegetation of significance and provides a greater degree of protection than any condition the Tribunal might impose. The modification is sought in respect of a specific property and it is our intention to order it in such terms in any event, and to provide for access in the location suggested.

92. We attach a draft order indicating the modification we are prepared to make in the restriction and the conditions to which it will be subject requiring confirmation that the compensation payments we have determined have been paid to the relevant objectors.

93. This decision is final on all matters other than the costs of the application. The parties may now make submissions in writing on such costs, and a letter giving directions for the exchange and service of submissions accompanies this decision. The attention of the parties is drawn to paragraph 12.5 of the Tribunal’s Practice Directions dated 29 November 2010.

Martin Rodger QC, Deputy President Paul Francis FRICS, Member

14 January 2020