High Court of Ireland Decisions

You are here:

BAILII >>

Databases >>

High Court of Ireland Decisions >>

Sherry v The Minister for Education and Skills & Ors (Approved) [2021] IEHC 128 (02 March 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IEHC/2021/2021IEHC128.html

Cite as:

[2021] IEHC 128

[

New search]

[

Printable PDF version]

[

Help]

APPROVED

[2021] IEHC 128

THE HIGH COURT

JUDICIAL REVIEW

[2020 No. 655 JR]

BETWEEN

FREDDY SHERRY

APPLICANT

AND

THE MINISTER FOR EDUCATION AND SKILLS, THE MINISTER FOR

FURTHER EDUCATION AND HIGHER EDUCATION, RESEARCH, INNOVATION

AND SCIENCE, IRELAND, AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

RESPONDENTS

Judgment of Mr. Justice Charles Meenan delivered on the day of 2

nd

March, 2021.

Contents

2

Introduction

1.

The fight to contain the spread of the Covid-19 virus has involved the imposition by

the State of restrictions on almost every aspect of our lives. The young, the old, those with

disabilities, and those without have all been affected, some to a greater degree than others. To

halt the spread of the virus, it is necessary to limit, if not restrict entirely, the circumstances

under which people meet and congregate.

2.

In excess of 62,000 students were due to sit the Leaving Certificate in 2020. This

obviously involved the congregation of significant numbers of people in close proximity in an

indoor setting for prolonged periods of time. As the date for the commencement of the Leaving

Certificate 2020 approached, it was apparent that, though the spread of the virus had at that

stage been significantly reduced, for reasons of public health, the examination could not take

place. For the first time in the history of the State, by a decision of the Government of 8 May

2020, the Leaving Certificate due to start the following month was cancelled.

3.

The Leaving Certificate has a central role in the Irish education system. For those who

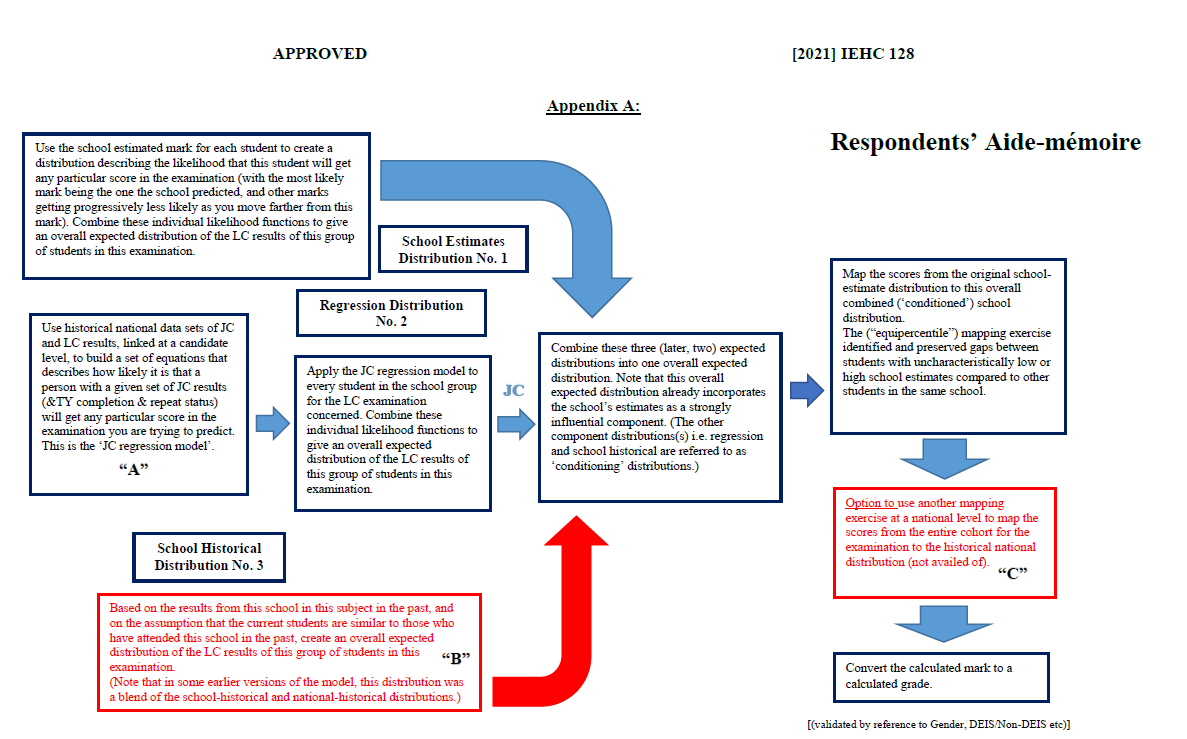

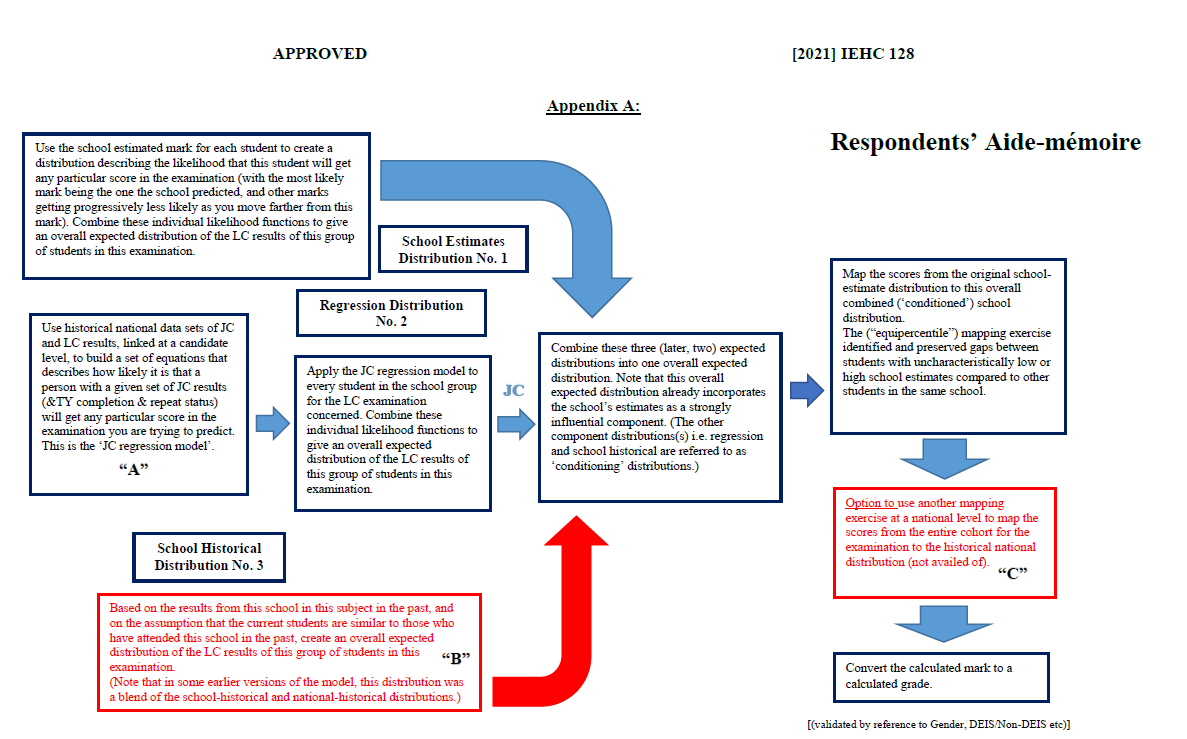

wish to advance to third level education, the results of the Leaving Certificate are, for the most

part, a basis for entry to a particular course and a subsequent career. For others, who do not

wish to pursue third level education, the Leaving Certificate is a qualification that may be

necessary to obtain employment. The importance of the results of the Leaving Certificate

cannot be overstated for young people who wish to pursue a particular career or, indeed, for

more mature people who may wish to embark on a new and different career. Without a Leaving

Certificate, the class of 2020 would have been left stranded, so it was imperative that an

3

alternative system be devised to give an accurate assessment, as far as possible, of the standards

that would have been achieved had the exam proceeded in the normal way. The first named

respondent (the Minister) did not have the option to simply defer Leaving Certificate 2020 to

2021.

4.

The whole Leaving Certificate system has been the subject of comment and criticism

over many years. However, it is difficult, if not impossible, to replicate by an alternative system

the fairness of the Leaving Certificate exam. Students doing the Leaving Certificate exam come

from various and diverse backgrounds. Families of some students have the financial means to

send their children to "fee-paying" schools and to provide additional education by way of

grinds. Other families who do not have such financial means may, with great sacrifice, enrol

their children in "fee-paying" schools. Very many other families simply cannot afford this but

want their children to do a good Leaving Certificate and, notwithstanding the inequalities in

the system, have equality of opportunity. However, at the end of the day, all students do the

same exam. The correction of each subject in the Leaving Certificate is done entirely

anonymously and according to guidelines which, prior to their adoption, have been considered

in detail by the relevant experts.

5.

The task facing the Minister in devising a system that would give to a student a grade

that he or she would have obtained had the Leaving Certificate exam been sat in the normal

way cannot be underestimated. Further, this task had to be completed to the satisfaction of

students, teachers and the wider public in a narrow timeframe. The system devised was the

awarding of "calculated grades".

6.

The basis used for the award of a calculated grade raises fundamental issues, not all of

which are legal. It is a fact that certain schools, in particular "fee-paying" schools, have

historically achieved stronger Leaving Certificate results than other schools. Should the

calculated grades being awarded in 2020 reflect this? Also, grades achieved in the Leaving

4

Certificate may vary depending upon the gender and socio-economic background of the

candidates. Should this also be reflected in the awarding of calculated grades? It would not be

acceptable to many to factor into the system for the awarding of calculated grades inequality,

since it must be a basic principle of any for education system to achieve equality of opportunity.

Thus, a system that may, statistically, give an accurate result would not be acceptable to the

public at large. It was the requirement for public acceptance that was central to the decisions

taken by the Minister and the Government that are the subject of these proceedings.

Calculated grades

7.

There were two phases to the system for the awarding of calculated grades. Firstly, a

schools phase; and, secondly, a phase overseen by the Department of Education and Skills (the

Department).

8.

The school phase involved the award by the relevant teacher(s) of an estimation of the

percentage mark in each subject that each candidate is likely to have achieved if they had sat

the Leaving Certificate examination in 2020 under normal conditions. The school then carried

out a "class ranking" for each student in each subject, i.e.: a list of all the students in each

individual class group for a particular subject in order of their estimated level of achievement.

Amongst the matters which informed estimated marks and rankings were the previous results

of the school in the particular subject.

9.

It was correctly anticipated that the estimated marks coming from the schools were

likely to be overestimated and considerably ahead of what the particular school had achieved

in past years. This is not an adverse reflection on the professionalism of the teachers involved

but, rather, of the difficulties faced by teachers in having to give marks to their students in

what, for many, would be the most important examination of their lives. Thus, simply awarding

school estimates as calculated grades for the Leaving Certificate of 2020 was not a viable

option, as it would undoubtedly lead to hyper "grade inflation".

5

10.

The Department phase involved the consideration and design of a "standardisation

model", which would be applied to the estimated marks coming from the schools. This was

with a view to making the calculated grades that would be awarded statistically accurate and

in line with previous years. Hence, the proposed use of "school historical data" and "national

historical data".

School historical data (SHD)

11.

This was data based on historical Leaving Certificate examination performance for the

particular school across three prior years. It is the case that the performance of students in each

school does not vary widely from year to year and, so, it was considered statistically reasonable

to assume that the cohort of students in any individual school in 2020 would not perform very

differently to that of previous years. It should be noted, as I have referred to elsewhere, that

historical school performance in each subject was a matter that should be taken into account at

school level in the giving of a calculated mark. Also, data concerning prior performance in the

Junior Certificate was part of the standardisation model and remained in place.

National historical data (NHD)

12.

This is data of student results on a subject by subject basis based on historical Leaving

Certificate examination performance. The reason for using this data in the standardisation

model was to ensure that, overall, the calculated grades awarded in the Leaving Certificate of

2020 were in line with the results of previous years. The purpose of applying this data was to

avoid "grade inflation".

13.

In order to avoid "grade inflation", not only was NHD to be used in the model, but also

another mapping exercise at a national level to map the scores from the entire cohort for the

examination to the historical national distribution would have to be used. This is referred to as

the "mapping tool". As we shall see, this "mapping tool" was not used.

6

Government decision of 1 September 2020

14.

At its meeting of 1

September 2020, the Government took two decisions on the data

that was to be used in the final version of the standardisation model for the awarding of

calculated grades: -

(i)

School historical data (SHD) would be removed from the range of data being

used in the standardisation model, however, data from previous Junior

Certificate examinations would still be used; and

(ii)

The national historical data (NHD) would be retained in the standardisation

model but the "mapping tool" would not be applied, and so the impact of this

data would be minimal.

Leaving Certificate results of 2020

15.

Results were issued to students entitled to receive calculated grades on 7 September

2020. Students also had available to them the estimated marks from their schools, as were

submitted to the Department. Thus, students could compare the calculated grades that had been

awarded with the estimated school marks. The media reported widely that students who had

attended schools or other educational establishments which historically had good Leaving

Certificate results had been awarded calculated grades below the estimated marks that had been

submitted. It was maintained that this "downgrading" stemmed from the Government decision

to remove SHD from the standardisation model.

16.

Some days after the release of the Leaving Certificate results, the Central Applications

Office (the CAO) published the points required for entry to various third level courses. It was

immediately apparent that there had been a considerable increase in points as a result of "grade

inflation". Though not highlighted at the time, this would appear to have been as a result of the

decision not to use the "mapping tool".

7

17.

The applicant was amongst those who believed that he had been unfairly downgraded.

The applicant attended Belvedere College in Dublin for his secondary education. He stated in

his Grounding Affidavit that he studied consistently for the Leaving Certificate up to the time

of the announcement of 8

May 2020 that the exam was cancelled and would be replaced by a

system of calculated grades. His Leaving Certificate subjects were English, French, Chemistry,

Biology, Irish, Latin and Maths. He received his calculated grades on 7 September 2020, and

received his teachers' estimated marks on 14 September 2020. The applicant had apparently

been downgraded. He stated that the result of these downgrades was that he did not have the

points necessary for his third level course of choice. I will examine, in some detail, the

calculated grades that were awarded to the applicant and the influence, if any, which the use of

the SHD would have had if it had been applied.

18.

An affidavit was filed by Mr. Tom Doyle, Deputy Principal of Belvedere College. In

the course of his affidavit, he refers to not only the Leaving Certificate results of the applicant

but, also, to those of other students in the school. He maintains that the absence of SHD in the

final standardisation model adversely affected the Leaving Certificate results, which had been

historically strong, in Belvedere College. Later in the judgment, I will also consider whether,

in fact, Belvedere College has been so adversely affected.

19.

In addition to the applicant herein, close to 70 other sets of proceedings were initiated

concerning the award of calculated grades. As the issue of SHD was common to many of these

actions, the Court directed that the parties involved select one test case so that this issue could

be determined. The parties selected the instant case. Both the Court and the parties were

conscious that the issues involved had to be resolved as soon as possible in a tight timeframe.

This was necessary since the Leaving Certificate of 2021 was then only a matter of months

away. It is to the credit of the parties in this case, and their advisors, that this difficult and

complex case was ready for hearing in a matter of weeks. The hearing of this application

8

commenced on 8 December 2020 and concluded on 2 February 2021, some five weeks of

hearing.

The issue

20.

At a hearing towards the end of November, 2020, a number of preliminary matters were

decided by the Court, including: the inspection of various standardised models, cross-

examination of deponents of affidavits and whether executive privilege was applicable. The

Court directed that the following issue be determined: -

"That the decision of the first and fifth named respondents of 19 August 2020 and/or

the decision of the first named respondent of 21 August 2020 and/or the confirmation

of the said decision by the sixth named respondent on 1 September 2020 to alter the

standardisation model so as to exclude the use of all school by school historical data

(SHD) on the performance of students in past cohorts in each subject was arbitrary,

unfair, unreasonable, irrational and unlawful and in breach of the applicant's legitimate

expectations."

It will be seen that the above only referred to SHD and did not refer to the decision not to apply

the "mapping tool" to NHD. In the course of the hearing, there were lengthy submissions and

considerable evidence on the latter decision. Towards the end of the hearing, objection was

taken by the respondents to the inclusion of this decision as being part of the issue before the

Court.

21.

I will not accede to this objection as, as I have said, evidence was given and submissions

were made, without objection, in the course of the hearing. I am satisfied that this second

decision, not to apply the "mapping tool", was fully dealt with. However, for the reasons I will

set out later in this judgment, I am of the view that the same legal principles apply to both

decisions. It therefore follows that in considering the issue the Court will give its determination

9

as to the lawfulness of the removal of SHD and the non-application of the "mapping tool" to

NHD in the standardisation model that was finally used.

Evolution of the standardisation model

22.

The standardisation model that was eventually used, Model 21(a), to process the school

data of the applicant evolved over a period of time, undergoing a number of iterations. In the

course of its evolution, two decisions were taken by the Minister. Firstly, to remove school

historical data (SHD) from the model and, secondly, not to apply the "mapping tool" to the

national historical data (NHD). Both of these decisions affected the calculated grades that were

awarded. In this section of the judgment, I will consider how and why these decisions came

about, the evidence that was given to the Court and my conclusions.

23.

The prevailing circumstances that were facing the Minister cannot be discounted. In a

matter of weeks, the well tried and trusted Leaving Certificate had to be replaced by an

alternative system that would award grades to the Leaving Certificate class of 2020 so that they

could go on to third level education or choose other careers. Each student had to have a Leaving

Certificate for 2020. Simply postponing everything for one year was not an option, the class of

2020 could not be abandoned.

24.

The calculated grades awarded for Leaving Certificate 2020 had to meet two objectives.

Firstly, they had to be statistically accurate, and, secondly, they had to be acceptable to

universities, future employers and the wider general public. These objectives were not easily

met. For example, details of the gender and socio-economic background of a candidate for the

Leaving Certificate might make the standardisation model more statistically accurate but

would, at the same time, not make it acceptable to the public. It was in this context that the use

of SHD and, to a lesser extent, not using the "mapping tool" became problematic. The Minister

established a complex structure to advise on and design a system for the awarding of calculated

grades. A Calculated Grades Executive Office was established to deliver the system of

10

calculated grades. A decision making forum, the National Standardisation Group (the NSG)

was established. The purpose of the NSG was to be "the decision-making group responsible

for the implementation of the iterative standardisation process and the application, review, and

adjustment of the data in line with the principles, parameters and constraints associated with

the model to arrive at fair and just representations of student performance". (Report from the

NSG, 6 September 2020). To achieve its purpose, the NSG would consider the statistical

outcomes of various iterations of the standardisation model. This required the NSG to: -

i.

Interrogate the data-sets emerging from the model at each iteration.

ii.

Compare outcomes at national level with those of recent years.

iii.

Consider effects and impacts at school level.

iv.

Ensure that the appropriate balance was struck between optimising the statistical

accuracy and maintaining "face validity".

In addition, an Independent Steering Committee was established by the Minister to provide

assurance to the Minister "of the quality and integrity of the outcomes of the calculated grades

system ...".

25.

The decision to postpone the "traditional" Leaving Certificate of 2020 was set out in

a decision of the Government dated 8 May 2020. This decision stated that the Government

agreed: -

"(i) ---

(ii) to put in place a system to be operated by the Minister ... on an administrative

basis pursuant to executive powers of Government under Article 28.2 of the

Constitution, whereby Leaving Certificate candidates could opt to have calculated

grades issued to them by the Minister in order to facilitate their progress to third-level

11

education or the world of work in Autumn 2020, and such system shall include the

following elements:

(a)

the professional judgment of each of the candidate's teachers which shall not be

subject to appeal;

(b)

in-school alignment to ensure fairness amongst candidates at school level;

(c)

approval by the school principal of the estimated scores and rankings of students

in the school;

(d)

a process of standardisation at national level to ensure fairness amongst all

candidates; and

(e)

--

(iii) to deliver the system through a non-statutory executive office in the Department

of Education and Skills and a non-statutory steering committee, made up of relevant

experts, who will oversee the quality and independence of the process under the

authority of the Minister; ..."

The said decision further stated: -

(vi) the calculated grades model would use estimated examination scores from students,

teachers and schools and would also involve standardisation at national level to ensure

equity of treatment for candidates; ..."

26.

On 21 May 2020 the Minister published a document entitled: -

"A Guide to Calculated Grades for Leaving Certificate Students 2020".

This document set out in general terms the basis upon which calculated grades would be

awarded. In his Grounding Affidavit, the applicant made specific reference to certain sections

of this document: -

Para. 2, which states: -

12

"A Calculated Grade is a grade that can be provided to students following the

combination of school information about a student's expected performance in an

examination and national data available in relation to the performance of students in

examinations over a period of time. ..."

Para. 10.2: -

"What happens to the school data in this process?

The rank order within the class group is preserved in the statistical process. However,

the teachers' estimated marks from each school will be adjusted to bring them into line

with the expected distribution for the school. The national standardisation process

being used will not impose any predetermined score on any individual in a class

or a school. ...

The relevant Department data sets that support the process include mark data at:

·

National level for both Leaving Certificate and Junior Certificate examinations for

2019 and previous years;

·

School level for both Leaving Certificate and Junior Certificate examinations for

2019 and previous years;

·

Candidate level for both Leaving Certificate and Junior Certificate examinations

for 2019 and previous years;

·

Candidate level for the Junior Certificate results of the 2020 Leaving Certificate

cohort of candidates."

And 10.3: -

"Processing the school level data

In advance of receiving the estimated marks from schools the information about how

the school has done in the past and the information about the strengths and weakness

of the current group of students will all be assembled and will be used to predict the

13

level of achievement that this particular group of students would have been expected to

reach in that subject if those students had sat the Leaving Certificate examination in the

normal way. This information is then combined with the estimates that the school has

provided in order to generate the fairest possible result that can be calculated.

..."

27.

A further document published by the Minister on 20 July 2020 once again set out the

relevant information that would be used to support the process. The document further stated: -

"By collecting and using a range of different types of information, the different sources

of data will complement each other, to provide the most accurate and fair set of results

within the limitations of the available data. As the school data is only accurate at school

level, the final calculated marks, and so Calculated Grades, provided to students, for

any subject and level, may be higher or lower than the estimates provided by their

school.

It is as a result of this standardisation process that the Calculated Grades will have an

equal standing and status with previous and future Leaving Certificate grades. If this is

not done, it would undermine the currency and value of Calculated Grades.

---

The maintenance of a national standard during the Calculated Grades process is as

important as in previous years in order to ensure that the Leaving Certificate 2020

Calculated Grades are of equal standing to the outcomes from previous years. This is

in order to ensure equity and fairness for the 2020 cohort but also for previous and

future students who may be competing for college places or in the world of work. ..."

28.

Candidates for Leaving Certificate 2020 had an option to opt into the calculated grades

system and still sit a written Leaving Certificate exam later in the year. Alternatively,

candidates could opt not to receive calculated grades and later sit the Leaving Certificate. In

14

any event, the decision had to be made before 4 p.m. on Monday 27 July 2020. This was set

out in a document entitled "Getting my Calculated Grades a Guide for Students". In the

course of the document it was stated: -

"Calculated Grades have the same status as the Leaving Certificate results awarded to

students in previous years. There is no downside to opting into receiving a Calculated

Grade."

The applicant opted to receive calculated grades.

29.

Meanwhile, various iterations of the standardisation model were being considered and

examined. In the course of a lengthy affidavit, Mr. Dalton Tattan, Assistant Secretary of the

Department of Education and Skills, stated: -

"The NSG's role included considering the statistical outcomes within a decision-

making framework which took account of the commitments, principles, values and

constraints which apply to calculated grades and to arrange for the implementation of

adaptions in order to tune the model through various iterations. This required the Group,

inter alia, to interrogate the data-sets emerging from the model at each iteration from a

range of perspectives at national level, at various disaggregated levels, ..."

He also stated that: -

"... Those commitments included ensuring that the results of school groups in 2020

were not unduly constrained by the historical performance of the school, ensuring that

the results of individual students in 2020 were not unduly constrained by the historical

performance of the school and placing a high value on the estimates from schools. It

was recognised that the overriding imperatives of fairness and accuracy could require

the relaxation or adjustment of some of those commitments in particular circumstances.

..."

15

30.

In August, 2020, the commitments that had been given to apply SHD came sharply into

focus. This was, primarily, as a result of events that took place in the United Kingdom. The

authorities in the UK were faced with a similar problem concerning the cancellation of the A

Level examinations, which are, roughly, equivalent to our Leaving Certificate examinations.

A calculated grades system was put in place. There was a separate system for Scotland. Like

the system in this country, it was envisaged that historical school data could be used to achieve

statistical accuracy in the calculated grades given. Mr. Tattan stated in his affidavit that the use

of school historic data in the UK was referred to as a "post code lottery" and "school

profiling", particularly in cases where the scale of over estimation of teacher grades was greater

in schools serving areas of disadvantage than in schools serving more affluent communities

and smaller, private fee-charging schools. This caused a major political crisis in the UK and,

indeed, threatened the future of the Government of Scotland. In response, use of a

standardisation model was abandoned and candidates were awarded calculated grades based

on school estimates, save where the calculated grade was greater.

31.

Almost immediately, the issues that were convulsing the UK calculated grades system

were widely reported by the media here. Attention was immediately focused on the use of SHD.

This was taken up by politicians and commentators, criticising the use in this country as to

what was being described in the UK as being a "post code lottery" and "school profiling".

The fact that there were a number of fundamental differences between the system for the award

of calculated grades in this country and that of the UK (to a lesser extent in Scotland) was

completely lost in the ensuing storm.

32.

The political storm set in train a number of events that would culminate in a decision

of the Government to remove SHD from the standardisation model and not to apply the

"mapping tool" to NHD. Evidence of these events was given to the Court by Mr. Tattan, who

was cross-examined, at length, on his affidavit. Mr. Tattan stated that the Minister herself had,

16

since taking office at the end of June, 2020, considerable doubts and misgivings on the use of

SHD. The Minister had to consider the effects of removing SHD. The removal of SHD would

result in taking out of the standardisation model the measure of "school effectiveness". This

means, in simple terms, that schools who have a history of obtaining high grades in the Leaving

Certificate are more likely to be accurate in their estimated marks than are schools with a less

good history.

33.

To illustrate the statistical effects of removing SHD, two models were looked at:

Models 10 and 17. For the purposes of these models only two schools were selected. The first

school, Mount Anville, had a record of strong results in the Leaving Certificate; and the other

school, a DEIS school, did not have such a record. Only one subject was considered, namely:

Mathematics, both at ordinary and higher level. In Model 10 SHD was removed, whilst it was

retained in Model 17. It should also be noted that Model 17 did not preserve the class rankings

as submitted by the schools. This exercise appeared to show that the omission of SHD in Model

10 led "to a substantial decrease in the mean mark (in higher/ordinary level mathematics) and

the grade profile in comparison to what the school had seen in the past". On the other hand,

in respect of the DEIS school, the removal of SHD had led to a substantial increase in the mean

mark and the grade profile in comparison to what the school had seen in the past. This would,

on its face, appear to show that the removal of SHD would adversely affect a traditionally high-

performing school, such as Mount Anville. However, as against this it must be noted that these

models only looked at two schools and one subject, they were experimental in nature and, in

any event, would not have been the final model that would be used for the award of calculated

grades.

34.

The Minister was informed of the exercise concerning Models 10 and 17.

35.

Confusion arose in the course of Mr. Tattan giving his evidence as to inclusion in the

standardised model of national historical data (NHD) and the application of a "mapping tool"

17

to such data. It will be recalled that the purpose of including such data was to bring about an

alignment between the results of 2020 and those of previous years. Whereas though NHD was

included, its effects on the eventual calculated grades awarded were reduced by the non-use of

the "mapping tool". In the course of his evidence, Mr. Tattan incorrectly indicated that NHD

was not used. However, the decision that was, in fact, taken was not to apply the "mapping

tool". Had the mapping tool been used, it would have meant that some 58% of higher level

grades would have been reduced by one grade. It was the view of the Minister that such a

downward adjustment in the schools' estimates "could have been fatal to the acceptability of

the calculated grades system". (Per para. 62 of the affidavit of Mr. Tattan). This resulted in

"grade inflation" in the order of 4.5% to 5%. Mr. Tattan expressed the view that there was, in

effect, a trade-off between grade inflation and restoring public confidence in the calculated

grade system.

36.

I have already referred to the fact that the standardisation model underwent numerous

iterations in the period that led up to the events and the consequent decisions of August and

September, 2020. By the middle to the end of August, the Minister was looking at two models,

namely: 18(a) and 18(g). In Model 18(a) SHD had been "dialled down to the greatest possible

degree", whereas in Model 18(g) SHD had been removed completely. Further, though in both

of these models there was an element of NHD, in neither was the "mapping tool" applied.

Before proceeding, two matters should be noted. Firstly, there was a Model 18 which evolved

into 18(a) and (g); and, secondly, the model that was ultimately used was Model 21(a), though

the differences in the final model and Model 18(g) do not appear to be relevant. As to the

circumstances under which Models 18(a) and (g) came about, the Court heard evidence from

Mr. Hugh McManus who was cross-examined, at considerable length, on his affidavits.

37.

Mr. McManus was Assistant Director of the Calculated Grades Executive Office at the

Department of Education and Skills. Mr. McManus was also a member of the NSG. He gave

18

detailed evidence of the various iterations of the standardisation model that led to Model 18

and subsequent models. In particular, he described the effects of using SHD in earlier models.

He stated that, paradoxically, over emphasising the role of SHD had actually caused the schools

to come closer together, which was not what one might expect. He stated that if you tried to

force SHD too strongly into the model that you actually prevent either individuals, or groups

of individuals, from deviating from the history of the school to the extent that they ought to if

the model was functioning properly. These observations on the effects of the use of SHD had

led to Model 18(a), which had reduced SHD to the lowest degree possible. Mr. McManus stated

that this had occurred without the intervention of the Minister and that if the Minister had not

intervened the SHD that would have been used in the final model was as it had been used in

Model 18(a). Mr. McManus was aware of the Minister's view of SHD. This evidence was the

source of considerable controversy, which I will return to shortly.

38.

Mr. McManus accepted that removing SHD from the model was removing a significant

source of information, being the element of school effectiveness. He gave evidence concerning

four tables that were set out in a document entitled "Information Note Calculated Grades"

of 20 August 2020 from the Department of Education and Skills. It would appear that this note

informed the decision that was taken to remove SHD and not to use the "mapping tool". In

this document there are four tables which set out the effects of either using Model 18(a) with

SHD and Model 18(g) without SHD. In the course of his cross-examination on these tables,

Mr. McManus accepted that they give a generalised view of how many grades will be increased

or decreased and that they do not give information as to which cohort of students will gain or

lose, though he did state that with every change to the standardised model some students would

gain and others would lose. Mr. McManus accepted that, from a purely statistical perspective,

the results that would have emerged had SHD been left in were likely to be more statistically

accurate than the ones that emerged from the standardisation model without SHD.

19

39.

Whilst giving his evidence, Counsel for the applicant challenged Mr. McManus on his

evidence that the SHD that was used in Model 18(a) was as a result of the evolution of the

standardisation model, rather than by intervention of the Minister. In a later submission,

Counsel referred to documents from Ms. Andrea Feeney, Director of the Calculated Grades

Executive Office, which, on their face, indicated that the change in the use of SHD was

prompted by intervention of the Minister following on from the public controversy, which I

have referred to. These documents were not put to Mr. McManus in the course of his cross-

examination. This prompted a letter from the Chief State Solicitor's Office, on behalf of the

respondents, suggesting that Mr. McManus be recalled to give evidence on these documents

and that Ms. Andrea Feeney also be called to give evidence on this. It should be noted that in

the course of a preliminary hearing this Court refused an application by the applicant to cross-

examine Ms. Feeney on her affidavits. Counsel for the applicant submitted that the content of

the evidence given by Mr. McManus should have been referred to in both the Statement of

Opposition and replying affidavits. Arising from this it was maintained that there was a lack of

candour on the part of the respondents, and that they had failed to meet the applicant's case

"with all cards face up", as they ought to have done. The applicant invited the Court to reject

the evidence of Mr. McManus on this point. As for the fact that the documents from Ms. Feeney

were not put to Mr. McManus, in the course of cross-examination Counsel relied on the rule in

Browne v. Dunn, as considered by the Supreme Court in McDonagh v. Sunday Newspapers Ltd

40.

I will not be acceding to this application. I accept the evidence of Mr. McManus for a

number of reasons. Firstly, Mr. McManus was cross-examined at length and in detail,

commencing on the morning of Wednesday 13 January and concluding on the afternoon of

Friday 15 January, in excess of two and a half days. In the course of that time, I had an

opportunity to assess Mr. McManus as a witness and I am satisfied that, at all stages, he gave

20

his evidence truthfully and conscientiously. As for the suggestion that this was "new" evidence

and ought to have been referred to in both the Statement of Opposition and the various replying

affidavits, I do not accept this. All of the documentation in this case makes clear that the

standardisation model was undergoing numerous iterations before a final model was arrived at.

Various iterations can only mean changes in the model from one iteration to another. Mr.

McManus was a member of the NSG and it is clear that changes to the manner in which SHD

was being used were within its terms of reference (see para. 24 above). Arising from this, I do

not accept that there has been any lack of candour on the part of the respondents. I do not attach

very much significance to the fact that Ms. Feeney's documentation was not put to Mr.

McManus in the course of his cross-examination. However, I would have thought that if this

evidence from Mr. McManus was as significant as the applicant maintains it was that the offer

to recall Mr. McManus and, indeed, the offer to make Ms. Andrea Feeney available to give

evidence would both have been accepted. Further, insofar as the evidence of Mr. McManus

may have had implications on the statistical aspect of the case, the applicant declined an

opportunity to recall their own statistical expert, Professor Cathal Walsh, to deal with this.

41.

Having considered the evidence of Mr. McManus, I find, as a fact, that had there been

no intervention by the Minister, the SHD that would have been used in the final standardisation

model would have been as it was used in Model 18(a). In this context, I also note that the only

model in respect of which the applicant submits SHD was used appropriately was Model 17. It

was common case that Model 17 was a developmental model and would not have been used as

a final model.

42.

I will now consider the documentation that was before the Court on which the decision

of the Minister was based. The respondent claimed executive privilege over the memorandum

to Government. I refer to a document, namely: "Information Note Calculated Grades" of 20

August 2020. This document refers to the memorandum to Government of 8 May 2020 which

21

sets out the data to be used in the standardisation process so as to ensure the equitable treatment

of candidates for Leaving Cert 2020. This data was: -

(1)

The estimated marks and ranking of students supplied by schools;

(2)

The historical national distribution of student results on a subject-by-subject

basis based on historical Leaving Certificate examination performance;

(3)

School historical data based on historical Leaving Certificate examination

performance at the school level across three prior years; and

(4)

A prediction of the likely Leaving Certificate performance of the class of 2020

in each school based on their collective performance when they undertook the

junior cycle examinations.

The document then sets out why standardisation was required, stating that different schools

would take different approaches for generating estimated marks and rank orders. Some schools

would be overly optimistic, others very harsh. The document further stated that the element of

the standardisation process that had proved to be least acceptable in public discourse had been

the use of SHD and reference was made to the events that had unfolded in the UK. However,

the safeguards, not present in the UK system, were set out.

43.

The document stated that two versions of the standardisation model were now available,

namely: Model 18(a) and Model 18(g). It was stated that one of the models, Model 18(g),

involved a change in the data sources used and that the Government would need to be made

aware of this change.

44.

The document considered the estimated marks that had been submitted by the various

schools, stating that when aggregated across all subjects the percentage of grade ones at higher

level in 2019 was 5.8%, while in the 2020 school based estimates it was 13.2%. Thus, the

percentage of grade ones had more than doubled in teachers' estimates in many subjects. The

22

document noted that "such a change in standards within one calendar year is simply not

credible".

45.

The document, in its four tables, sets out the effects of retaining SHD, albeit at a low

level, in Model 18(a), comparing the outcome to Model 18(g) where SHD had been removed.

This exercise was carried out for DEIS schools and non-DEIS schools. In summary, it was

found that Model 18(g) appeared to show that over 75% of all teachers' estimated grades would

remain unchanged, about 5% would be raised and 18.6% of the grades would be lowered.

Marginally fewer grades would be lowered in DEIS schools than in non-DEIS schools. The

recommendation was made to use Model 18(g).

46.

In the course of the hearing, the applicant emphasised that the NSG do not appear to

have been involved in the decision to remove SHD and not to apply the "mapping tool". These

matters were also the source of considerable debate amongst officials in the Department, with

various emails and commentaries therein being produced to the Court. However, the role of the

NSG was to develop a standardisation model based on the four data sets that had been identified

in various documentation that emanated from the Department. The NSG did not have authority

to remove a data set from the standardisation model as this was a matter for the Minister. In

any event, the NSG in its comprehensive report of 6 September 2020 supported the decisions

taken, as did the Independent Steering Committee.

47.

Prior to being considered by the cabinet, the decisions on the final standardisation

model were discussed by the Minister with the Taoiseach, and, separately, leading members of

the parties that make up the present coalition government were briefed. The matter came before

the Government on 1 September 2020. The written decision of the Government recorded the

following had been agreed: -

"(i)

that historical school distribution data, based on historical Leaving Certificate

Examination performance of past cohorts of students at the school level across

23

2017, 2018 and 2019, will be removed from the range of data being used in the

standardisation model in response to concerns that have been raised; and

(ii)

that the reliance in the standardisation model on historical national distribution

of students' results on a subject-by-subject basis, and therefore the impact of

this data, will be minimal."

48.

Having considered the affidavits filed, the exhibits and the evidence given to the Court

by Mr. Tattan and Mr. McManus, I am satisfied that the data that was used in the

standardisation model for the awarding of calculated grades did not meet the commitments that

had been given by the Minister. Though there was an element of SHD from the basis on which

teachers' awarded estimated marks and the use of prior Junior Certificate data, it clearly was

not used in the form that had been communicated to the applicant in the documentation I have

already referred to.

49.

There was also a commitment by the Minister that the results of the Leaving Certificate

of 2020 would be in line with the results of previous years. This commitment was also not

honoured in that by deciding not to apply the "mapping tool" to NHD it, inevitably, resulted

in "grade inflation" . As far as the applicant is concerned, this "grade inflation" has to be seen

alongside the effects on him of the removal of SHD.

50.

In the course of the hearing, the respondents supplied to the Court an aide-mémoire

illustrating how the standardisation model worked. There was no disagreement as to its

contents. I have therefore included it in Appendix A to this judgment. For clarity: -

-

"A" represents how NHD and prior Junior Certificate results were used;

-

"B" represents SHD, which was not used; and

-

"C" represents the "mapping tool", which was also not used.

51.

The failure of the Minister to honour these commitments has to be seen in the context

that the results of Leaving Certificate 2020 had to be acceptable to the general public. I will

24

now consider the legal principles that apply. I will also consider whether, in fact, the applicant

suffered any unfairness.

Justiciability

52.

The first legal issue which I will consider is whether the decisions, be they of the

Minister or the Government, are justiciable.

53.

Article 28.2 of the Constitution provides: -

"The executive power of the State shall, subject to the provisions of this Constitution,

be exercised by or on the authority of the Government."

Submissions

54.

Mr. Feichín McDonagh SC (with Mr. Micheál P. O'Higgins SC and Mr. Brendan

Hennessy BL), on behalf of the applicant, submitted that the system providing for the award of

calculated grades does not have a legislative basis, nor, indeed, does the Leaving Certificate

examination itself. Rather, the system was clearly administrative and voluntary. The system

was the result of negotiations entered into by the various interested parties. Therefore, the

decisions of August/September 2020 could not, and did not, transform the voluntary system

into a compulsory one. It followed, according to the submission, that the executive power of

the State was not invoked, save in respect of funding.

55.

As for the public controversy that arose following the events in the UK arising from its

system of calculated grades, Counsel submitted that the controversy was based on a complete

misunderstanding of the differences between the Irish system and that operating in the UK. In

the applicant's view, the pressure that built up on the Minister, which resulted in the impugned

decisions, was a result of ill-informed commentators and politicians. Thus, there was no

reasonable or rational basis for the decisions.

56.

As part of their submission, Counsel relied on a number of authorities. In State (C) v.

Minister for Justice [1967] I.R. 106, Walsh J. stated: -

25

"With regard to the last point, it is my opinion that the fact that a statutory power is

conferred upon a member of the executive or a representative of the executive, as was

the Lord Lieutenant, does not make that power an executive power within the meaning

of that expression in the Constitution as the statute might just as easily have conferred

the power on anybody else. ..."

Reliance was also placed on Gutrani v. Minister for Justice [1993] 2 I.R. 427. This case

concerned a letter that had been written on behalf of the respondent concerning procedures that

would be implemented for applications for refugee status and asylum, as had been suggested

by the representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The applicant

maintained that humanitarian considerations had not been taken into account in accordance

with the terms of the said letter. In the course of giving the judgment of the Supreme Court,

McCarthy J. stated: -

"The Minister does not contest that he is obliged to consider the application within the

framework of the letter of the 13th December, 1985. Having established such a scheme,

however informally so, he would appear to be bound to apply it to appropriate cases,

and his decision would be subject to judicial review. It does not appear to me to depend

upon any principle of legitimate or reasonable expectation; it is, simply, the procedure

which the Minister has undertaken to enforce."

The applicant also relied on a number of English authorities, in particular: The Secretary of

This case concerned a judicial review arising out of a refusal to grant a licence to catch what

was a very commercially valuable fish, the Patagonian toothfish.

57.

Ms. Eileen Barrington SC (with Mr. Brian Kennedy SC, Mr. Francis Kieran BL and

Mr. Joseph O'Sullivan BL) submitted that in making the impugned decisions the executive

power of the State was engaged. "Executive power" is not defined, but reliance was placed on

26

the following passage from the judgment of O'Donnell J. in Barlow v. Minister for Agriculture

"... It appears that the executive power in Irish law to date is, as Professor Casey

observed, the residue which is left when the judicial and legislative powers are

subtracted: Casey, Constitutional Law in Ireland, 3rd Ed., (Dublin, 2000), pp. 230-231.

..."

58.

The respondents submit that the calculated grade system was put in place by executive

decision to be operated by the Minister. This was deposed to in the affidavit of Mr. Tattan. Mr.

Tattan further deposed that the Government decision of 8 May 2020 was based on a

memorandum to the Government which included reference to using SHD as part of the

standardisation process. He maintained that in having to reconsider the matter a further decision

of the Government would be required.

59.

More particularly, the respondents submitted that the decisions to remove SHD and not

to apply the "mapping tool" to NHD involved matters of policy which, given the separation of

powers, fell outside the jurisdiction and competence of the courts to review. A number of

authorities were relied upon. As a general statement of the law, reliance was placed on the

decision of the Supreme Court in T.D. v. Minister for Education [2001] 4 IR 259. This was

an appeal to the Supreme Court from a decision of the High Court which had granted a

mandatory injunction directing the respondent to implement forthwith a policy that had been

formulated regarding the accommodation and treatment of children with special needs, which

category included the applicant. In his judgment, Murray J. (as he then was) stated: -

"Adopting a policy or a programme and deciding to implement it is a core function of

the Executive. It is not for the courts to decide policy or to implement it. It may

determine whether such policy or actions to implement such policy are compatible with

the law or the Constitution to fulfil obligations. That is not deciding policy.

27

Judicial review in a democracy

Thus the powers of the court include judicial review of acts of the executive and the

legislature. It is a feature common to many democracies, particularly with a written

constitution. Judicial review permits the court to set aside executive actions or

legislative measures which offend against the law or the Constitution. Judicial review

does not in such democracies give the courts jurisdiction to exercise rather than review

executive or legislative functions. Judicial review permits the courts to place limits on

the exercise of executive or legislative power, not to exercise it themselves. It deals

with the limits of policy, not its substance. That is why judicial review by the courts,

which are not answerable to any constituency other than the law and the Constitution,

is democratic. ..."

In considering the granting of mandatory orders, Murray J. stated: -

"In so far as McKenna v. An Taoiseach (No. 2) [1995] 2 IR 10, Crotty v. An Taoiseach

[1987] IR 713 and District Judge McMenamin v. Ireland [1996] 3 I.R. 100 might be

said to be authority for the making of some form of mandatory order where there is `a

clear disregard' by the State of

its constitutional obligations, it must be borne in mind

that in none of those cases was a mandatory order granted. I have already made the

distinction between `interfering' in the actions of other organs of State in order to ensure

compliance with the Constitution and taking over their core functions so that they are

exercised by the courts. ... In my view the phrase `clear disregard' can only be

understood to mean a conscious and deliberate decision by the organ of state to act in

breach of its constitutional obligation to other parties, accompanied by bad faith or

recklessness. A court would also have to be satisfied that the absence of good faith or

the reckless disregard of rights would impinge on the observance by the State party

concerned of any declaratory order made by the court. ..."

28

In the instant case, were the issue before the Court to be decided in the applicant's favour, a

declaratory order would follow.

60.

The respondents also submitted that not only are the impugned decisions a matter of

policy, but also that there were no legal standards of competency on the part of the Court which

could guide it were it to review the said decisions. The respondents relied on the decision of

the Court of Appeal in Moore v. Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht [2018] 3 I.R.

265. This case concerned a judicial review of a decision by the respondent arising out of the

refusal to declare Moore St. and its environs a "national monument" for the purposes of the

relevant statute. The High Court had granted the relief sought, including a declaration that

certain sites constituted national monuments for the purpose of the statute. In allowing the

appeal, Hogan J. stated: -

"(41) The reason why, however, the matter would be regarded as executive (or, possibly

in some instances, legislative) in character is, however, readily apparent, because the

designation of a monument as a national monument ultimately calls for political and,

in some instances, perhaps, administrative judgment ..."

and: -

"(42) The judicial branch quite obviously lacks the institutional competence, capacity

and, most of all, democratic legitimacy to determine policy matters of this kind. Article

34.1 of the Constitution instead requires the judiciary to administer justice, thus

typically requiring the judges to apply conventional legal materials - such as the corpus

of common law rules and principles, rules of statutory interpretation, precedent and

reasoning by analogy in a detached and principled fashion, regardless of the

consequences. ..."

On the issue of separation of powers, Hogan J. stated: -

29

"(44) The other branches of government bring with them the strength of democratic

accountability and the constitutionally assigned role of policy making. The Government

brings with it the policy insights of its members and the wider civil service. It can give

a lead as to what is likely to be effective in practical policy terms and it is likewise

dispensed from the necessity to rationalise its actions by reference to conventional legal

principles.

(45) The reason for this different approach is, of course, because, generally speaking,

the two other branches of government are engaged in the business of policy formulation

as distinct from the administration of justice. In contrast to judicial decision making,

the policy makers of the legislative and executive branches are not required to be

consistent or to have regard to established precedent or to proceed from legal principle

or to give detailed reasons in writing for their decisions. Nor are they required to be

detached and impartial in the same manner as is required of the judiciary by Article

34.6.1° of the Constitution. Critically, however, the two other branches of government

are democratically accountable in a way that the judiciary are not."

61.

Similar views were expressed by Hogan J. in Garda Representative Association v.

Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform [2016] IECA 18, which case concerned an

application for judicial review of a decision by the respondent to include An Garda Síochána

in "Sick Leave" Regulations. This inclusion was made notwithstanding a commitment that the

Gardaí would be excluded. It was not in dispute that the respondent Minister suddenly changed

his mind and decided that the Regulations would apply to the Gardaí, with immediate effect. It

subsequently emerged that the reason for the volte-face was that a senior trade union official

stated that the public sector trade unions would not accept any exemption or derogation for the

Gardaí. In upholding the decision of the High Court to refuse the applicants the reliefs they

sought by way of judicial review, Hogan J. stated: -

30

"(42) In the present case the Minister was engaged in the practical politics of policy

formation by piloting the 2013 Act through the Oireachtas and by subsequently

promulgating [the 2014 Regulations] ... It is true that the GRA might legitimately

consider that they had been let down by the manner in which that decision was arrived.

The GRA are also entitled to feel disappointed given that the critical intervention of

Mr. Cody was not disclosed to them at the time and this only came to light subsequently

in the course of the discovery process after these proceedings had been commenced.

Yet, from the Minister's perspective, the greater prize of securing the reform of a very

expensive feature of public service pay and conditions while avoiding the threat of

industrial action from other public sector unions made it imperative in the

circumstances that a snap decision of this kind (i.e., to include An Garda Siochána in

the new regime) be taken immediately, regardless of any assurances in relation to

consultation which the Minister might previously have given to the GRA.

(43) This conclusion finds expression in the case-law which has consistently rejected

the suggestion that legislative, or quasi-legislative decisions, attracts the principles of

fair procedures, even though such generally applicable rules might have significant

implications for the livelihood, well-being and general welfare of those affected by

such decisions. ..."

Evidence

62.

Dr. William Maxwell filed an affidavit exhibiting an expert report on behalf of the

respondents. Dr. Maxwell is an Educational Consultant and was Her Majesty's Chief Inspector

of Education for Scotland from 2010 to 2017. He led the creation and development of

Education Scotland, a new quality improvement agency established in 2011 to integrate both

inspection and improvement support functions. As HM Chief Inspector, he was Chief

Professional Advisor to Scottish Ministers on matters relating to education. From 2008 till

31

2010, he was Her Majesty's Chief Inspector for Education for Wales. Dr. Maxwell was in a

good position to give evidence on the system that was adopted in Scotland and the remainder

of the UK for the awarding of calculated grades due to the cancellation of state examinations,

the circumstances and nature of the political storm that blew up and the steps taken by

politicians to address the situation.

63.

In his report Dr. Maxwell stated: -

"In conclusion, on the basis of the evidence I have seen in relation to the development

of the Irish `calculated grades' approach through to its conclusion, it is my view that

the Minister acted rationally and reasonably in ordering the changes which were set out

in the memorandum of the 24

th

August. These were a reasonable response to ensuring

that the overarching policy objective of maintaining confidence in the fairness and

integrity of the awarding system was secured, in the context of heightened risk arising

from a series of high-profile problems emerging around equivalent approaches in the

UK and the resulting focus of public disclosure in Ireland throughout August.

Furthermore, having considered evidence of the outcomes of the standardisation

process in general, and its impact on Belvedere College in particular, I see no evidence

that the changes which the Minister ordered, including the removal of school-by-school

performance data, resulted in any unfair disadvantage to students at high-performing

schools, and consequently to him personally, in the way that the Applicant contends.

..."

64.

Dr. Maxwell was cross-examined on his report. It was put to Dr. Maxwell that the

standardisation model was likely to be more accurate if SHD was included. In response, Dr.

Maxwell stated that, from a statistically purist perspective, it would make the model more

accurate, as indeed would including "--the social postcode of the child and the family ". This

32

would not be considered to be ethical or credible in the public domain, even though it might

enhance the statistical technical accuracy of the model. He gave details of the controversy in

calculated grades that arose in the UK. Scotland was first to give its results first and the initial

public reaction was not concerning the treatment of disadvantaged schools, but, rather, "the

sheer scale and number of students who were affected by downgrading effectively ...". A

narrative developed that this downgrading had happened more to the pupils in certain

disadvantaged schools, and hence the use of a term such as "postcode lottery".

65.

Dr. Maxwell gave evidence that a feature of the criticism of the calculated grade system

in the UK was that by including SHD in the standardisation model, not only did it favour well-

resourced schools with a history of good exam results, but it also "pegged back" less well-

resourced schools whose examination results were improving year on year. He expressed the

view that when perception of the potential for unfairness takes hold, then the credibility of the

system suffers.

66.

Dr. Maxwell outlined what would have been the appropriate response to the public

controversy on calculated grades. He stated in evidence: -

"I think the role of public administration is to adjust and adapt the way systems are

operated to guard against criticisms that are, whether justified or unjustified, as far as

is reasonably possible, and it is, therefore if some adjustment can be made to a system

to protect it against allegations or the perception, right or wrong, without doing

detriment, significant detriment to the system, when it should be - - it makes sense to

adjust."

In the UK the response was, in effect, to abandon the standardisation process.

Consideration of submissions

67.

The first matter which I wish to consider is whether the impugned decisions were an

exercise of executive power. Applying the passage I cited from O'Donnell J. in Barlow v.

33

Minister for Agriculture, it would seem to me that this was an exercise of executive power.

The decisions taken were clearly not an exercise of judicial or legislative powers. The fact that

the calculated grade system was voluntary does not alter this. (See Ryanair DAC v. An

68.

In these proceedings, the applicant has not invoked any constitutional or legal right

(save for legitimate expectation, which I will consider later) that has been infringed. Nor has

the applicant identified any "clear disregard" of the respondents of their powers and duties

conferred on them under the Constitution, as per Murray J. in T.D. v. Minister for Education

(see para. 58 above). In my view, the decision of Walsh J. in State (C) v. Minister for Justice

is not of assistance. The passage of the judgment cited earlier (para. 56) is clearly referable to

"statutory power", which is not the case here. This also applies to the English Court of Appeal

decision in The Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs v. Quark Fishing

Ltd. What was involved there was also statutory provision. Further, the issue in Gutrani v.

Minister for Justice was a scheme set out in a letter from the respondent to the United Nations

High Commissioner for Refugees. This arose by reason of Ireland being a signatory to the

United Nations Convention on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, 1951 and the

United Nations Protocol on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, 1967, though these

were not part of domestic law of the State, such a letter is very different from the proposed

system of calculated grades in these proceedings. Further, in Gutrani the respondent did not

contest that he was obliged to follow the terms of the letter. That is clearly not the case here.

69.

Whatever issues there may be as to whether or not executive power was engaged in the

making of the impugned decisions, to my mind, these were policy decisions which, on the

authorities of T.D. v. Minister for Education; Garda Representative Association v. Minister for

Public Expenditure and Reform; and Moore v. Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht

34

are not reviewable by the Court. To explain how I reach this conclusion, it is necessary to

retrace some steps.

70.

The purpose and aim of the calculated grades system was to award each candidate a

calculated grade that would represent the grade that he or she would have obtained had the

particular exam been sat in the normal way. There were always two fundamental aspects to the

system. Firstly, that the system had to be statistically accurate, and, secondly, that there had to

be public acceptance of the system. The importance of public acceptance cannot be minimised.

Calculated grades awarded for Leaving Certificate 2020 would have to be accepted by those

responsible for admissions to third level education and present and future employers of the

class of 2020. However, what was not in dispute was that the use of certain data, e.g.: gender

and economic background, which might make the system more statistically accurate would not

be acceptable to the public. Statistical accuracy had to be sacrificed to maintain public

acceptance. This was the case even before the controversy arose in the UK.

71.

The effect of the controversy in the UK was that the inclusion of SHD and the

downgrading, on a large scale, of teachers' estimated grades, though statistically justifiable,

was not acceptable to the public. This left the Minister with three options, as per the evidence

of Dr. Maxwell: -

(i)

To carry on regardless, stick to the original plan, highlight the differences

between the Irish model and that in the UK, and make all the arguments to

persuade the public as to the fairness of the standardised model as it stood;

(ii)

To make a number of adjustments to the standardised model so as to reduce the

likelihood of a narrative gaining ground which could undermine the whole

system;

(iii)

To abandon the standardised model, as was done in all parts of the UK, the

Netherlands and France.

35

What is common to these options is an appreciation and understanding of what is necessary to

gain public acceptance and to restore confidence in the system for the awarding of calculated

grades. Being democratically elected politicians, the Minister and her Government colleagues

are best placed to decide what is, or is not, acceptable to the public. This puts the matter firmly

in the area of policy, which is a matter for elected representatives and not the courts. I refer to

the authorities, which the respondents relied upon, set out at paras. 56-60 above, arising from

the separation of powers, the courts have neither the competence nor legal authority to choose

one of the above options over another.

72.

Those, including the applicant, who feel aggrieved by the decisions taken by the

respondents are not without redress. I refer to the following passage from Hogan J. in Garda

Representative Association v. The Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform: -

"41. This democratic accountability has the important consequence that the electorate

expect their politicians to achieve practical results. Politicians who are perceived by the

electorate as having failed to deliver such results will potentially suffer the electoral

consequences. For these reasons, these politicians must have regard to the practical

consequences of their decisions and the wishes of the electorate in a manner which

would not be appropriate to judicial decision-making."

73.

In view of the foregoing, I am satisfied that the impugned decisions, notwithstanding

that they had the effect of reducing the statistical accuracy of the calculated grades that were

awarded and caused "grade inflation", were policy decisions taken by the respondents to

ensure public acceptance of the calculated grades system and are not justiciable by the Court.

Legitimate expectation

74.

It is clear from the terms of the issue before the Court that the applicant relies upon

"legitimate expectation".

36

75.

In Glencar Exploration Plc v. Mayo County Council (No. 2) [2002] 1 IR 84, Fennelly

J., having reviewed a number of authorities on legitimate expectation, drew the following

conclusions, which he described as provisional: -

"... Firstly, the public authority must have made a statement or adopted a position

amounting to a promise or representation, express or implied as to how it will act in

respect of an identifiable area of its activity. I will call this the representation. Secondly,

the representation must be addressed or conveyed either directly or indirectly to an

identifiable person or group of persons, affected actually or potentially, in such a way

that it forms part of a transaction definitively entered into or a relationship between that

person or group and the public authority or that the person or group has acted on the

faith of the representation. Thirdly, it must be such as to create an expectation

reasonably entertained by the person or group that the public authority will abide by the

representation to the extent that it would be unjust to permit the public authority to

resile from it. Refinements or extensions of these propositions are obviously

possible. Equally they are qualified by considerations of the public interest including

the principle that freedom to exercise properly a statutory power is to be

respected. However, the propositions I have endeavoured to formulate seem to me to

be preconditions for the right to invoke the doctrine."

I will now apply these conclusions to the case the applicant is making.

76.

Earlier in the judgment I quoted extensively from various documentation that emanated

from the Minister as to the data that would be used in the standardisation model for the

awarding of calculated grades. It was clearly the case that SHD would be used to achieve

statistical accuracy. It was also the case that the results of Leaving Certificate 2020 would be

aligned with those of previous years. This would necessitate the application of the "mapping

tool" to NHD. This is clearly a "public authority" making a statement "amounting to a

37

promise or representation, express or implied as to how it will act in respect of an identifiable

area of its activity".

77.

These representations were made directly "to an identifiable person or group of

persons", this being the applicant and the Leaving Certificate class of 2020.

78.

The third condition is somewhat more problematic. The respondents submitted that the

applicant failed to satisfy this condition in that in the document inviting the applicant to opt

into the calculated grades system stated: -

"... there is no downside to opting into receiving a calculated grade."

This statement was made in circumstances where the applicant still had the option to sit all or

any subjects in a "traditional" Leaving Certificate exam that was to be held in November that

year. In any event, the academic year in third level institutions would begin before that date

and, so, any points requirement had to be fulfilled on the basis of calculated grades so there

was no other option. In his affidavit, the applicant stated: -

"... As I thought the process was going to be fair, I didn't keep on studying for the

possible sitting of an exam in November."

Thus, the applicant maintains he acted to his detriment. In any event, there is authority for the

proposition that "detrimental reliance" is not a condition precedent to a successful claim of

legitimate expectation. I refer to the following passage from Administrative Law in Ireland by

Gerard Hogan, David Gwynn Morgan and Paul Daly (5

th

ed.) p. 1261 where, the authors having

quoted Fennelly J. in Daly v. Minister for the Marine [2001] IESC 77, state: -

"21-68 To put this important point another way: unfairness in the context of legitimate

expectations is not to be equated with detrimental reliance in the context of estoppel.

Whilst they draw inspiration from similar springs, they are distinct concepts which play

different roles in public and private law respectively. Where an applicant has

detrimentally relied on an assurance, policy or practice, his or her case may be

38

stronger (and/or may be needed to justify a public body resiling from its previous

position), but the absence of detrimental reliance will not be fatal to a legitimate

expectations claim.

However, what has to be established is that it would be `unjust to permit the public

authority to resile...' "

It follows from this that the applicant must establish some unfairness that he has suffered as a

result of the impugned decisions.

Fairness

79.

In the following paragraphs, I will consider the effects on both the applicant and his

school, Belvedere College, of the removal of SHD and the non-application of the "mapping

tool" to NHD. I will also consider the evidence given by the statistical experts on behalf of

both the applicant and the respondents.

80.

Given the number of candidates, possibly in excess of 62,000, being awarded calculated

grades, the unfairness would have to be of an order to render the system unlawful. It was clearly

the case that, from the start of the process, the standardisation model was going to undergo a

number of iterations. Each iteration was going to produce different results. Thus, it was

inevitable that any change to the model would result in some candidates gaining and others

losing. Those who lost would, undoubtedly, consider it to be unfair. However, in the absence

of evidence that the unfairness suffered by an individual was widespread across the cohort of

those receiving calculated grades and of a serious nature, it is difficult to see how such

unfairness could amount to being unlawful.

81.