Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

The Law Commission

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Anti-money laundering: the SARs regime (Report) [2019] EWLC 384 (18 June 2019.)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2019/LC384.html

Cite as: [2019] EWLC 384

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Anti-money laundering: the SARs regime

HC 2098 Law Com No 384

(Law Com No 384) |

Anti-money laundering: the SARs regime Report |

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 18 June 2019. |

HC 2098 |

© Crown copyright 2019

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence,

visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at anti-money- laundering@lawcommission.gov.uk.

ISBN 978-1-5286-1191-6 CCS0419963024 06/19

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum

Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

The Law Commission

The Law Commission was set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law.

The Law Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lord Justice Green, Chairman Professor Nick Hopkins

Stephen Lewis

Professor David Ormerod QC Nicholas Paines QC

The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Phil Golding.

The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne's Gate, London SW1H 9AG.

The terms of this report were agreed on 27 March 2019.

The text of this report is available on the Law Commission's website at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk.

Contents

Page

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 18

The project and our Terms of Reference 18

Money laundering and the UK’s legal response 19

The UK’s anti-money laundering framework 20

The money laundering offences 21

Key concepts 22

Authorised disclosures 23

Required disclosures 25

Failure to disclose by those working within the regulated sector 26

Failure to disclose by nominated officers working in the regulated

sector 27

Failure to disclose by other nominated officers 28

Tipping-off 29

Problems with the current law 29

Retaining consent 29

Recommendation 1. 30

The need for a balanced regime 30

Quality or quantity? 31

History of the project 32

Consultation 32

The SARs Reform Programme 33

Purpose of data analysis 33

Data analysis 34

Recent Developments 35

Volume of SARs 35

FATF Mutual Evaluation – underreporting and concerns about the

quality of SARs 36

Structure of report and recommendations 37

Acknowledgments 39

CHAPTER 2: MEASURING EFFECTIVENESS: DATA ANALYSIS 40

Introduction 40

The current scheme 40

Authorised disclosures 41

Methodology 43

Analysis 47

Conclusion 49

Recommendation 50

iv

Recommendation 2. | 50 |

CHAPTER 3: GUIDANCE | 51 |

Introduction | 51 |

The current scheme | 52 |

Criticisms of the current scheme | 52 |

Fragmented guidance | 53 |

Conflicting guidance | 54 |

Insufficient collaboration in creating and maintaining guidance | 56 |

No legal protection for reporters (“safe harbour”) | 56 |

Conclusion | 57 |

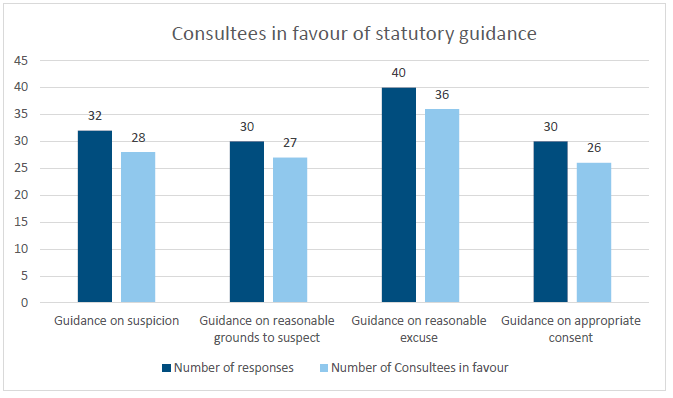

Consultation | 57 |

Single definitive source | 59 |

Collaboration | 59 |

Safe harbour | 60 |

Analysis | 61 |

Who would draft and approve the guidance we recommend: does the SARs regime need an Advisory Board? | 66 |

Recommendations | 68 |

Recommendation 3. | 69 |

Recommendation 4. | 69 |

CHAPTER 4: THE “ALL-CRIMES’’ APPROACH | 70 |

Introduction | 70 |

The current law | 70 |

Evaluation of the current law | 71 |

Consultation | 73 |

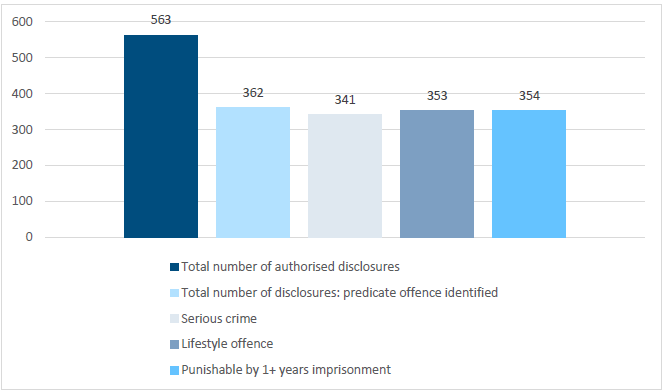

Data analysis | 76 |

Serious crimes | 76 |

Identification of the predicate offence | 76 |

Proportion of disclosures for non-serious offences | 77 |

Analysis | 78 |

Volume | 78 |

Intelligence value | 79 |

Identifying the predicate offence | 79 |

Drafting a list | 80 |

Pecuniary advantage | 82 |

Financial value | 82 |

Maximum penalty | 83 |

Two-tiered approach | 83 |

Conclusions | 84 |

Recommendation | 85 |

Recommendation 5. | 85 |

v |

CHAPTER 5: SUSPICION 86

Introduction 86

The current law 86

Authorised disclosures: sections 327(2)(a), 328(2)(a), 329(2)(a) and

338 of POCA 86

Required disclosures: sections 330-331 POCA 86

Meaning of suspicion 87

The obligations of the reporter 87

Criticisms of the current law 91

Impact on resources of NCA 93

Impact on individuals and businesses 93

Provisional conclusions 94

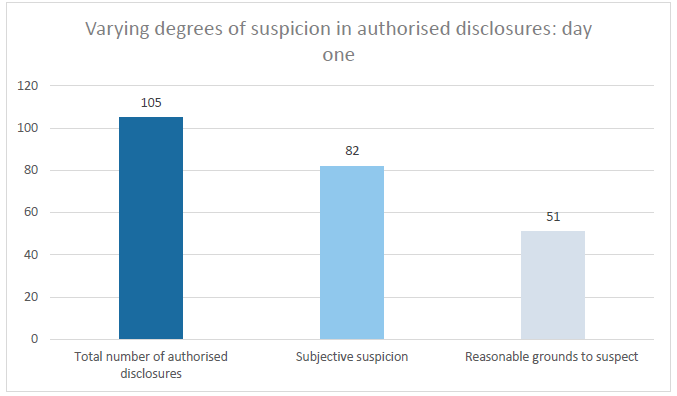

Data analysis 95

The issue 98

Defining suspicion 99

Analysis 100

Recommendation 101

Recommendation 6. 101

Guidance on suspicion 101

Prescribed form 105

Analysis 107

Recommendations 108

Recommendation 7. 108

Recommendation 8. 109

Moving to reasonable grounds to suspect 109

Consultation 112

Data analysis 114

Analysis 115

Recommendation 9. 117

Summary of our recommendations for reform 117

CHAPTER 6: APPROPRIATE CONSENT 118

Introduction 118

The current scheme 118

Evaluation of the current scheme 119

Consultation 119

Analysis 121

Recommendations for reform 122

Recommendation 10. 122

CHAPTER 7: REASONABLE EXCUSE 123

Introduction 123

The current law 123

vi

Evaluation of the current law | 123 |

Data analysis | 125 |

Consultation | 127 |

Analysis | 128 |

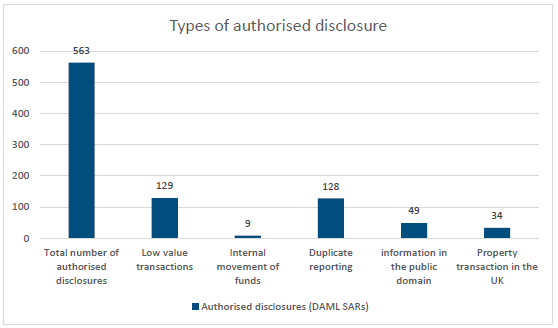

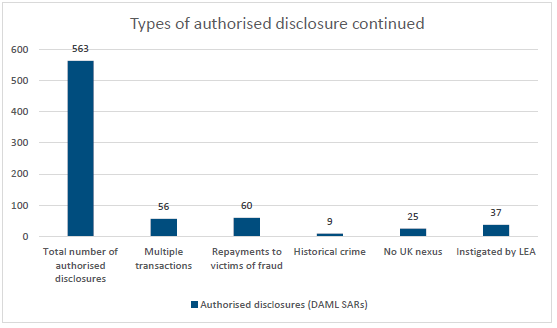

Low value transactions | 128 |

Recommendation 11. | 130 |

Internal movement of funds | 130 |

Duplicate reporting obligations | 131 |

Recommendation 12. | 132 |

Information in the public domain | 132 |

Property transactions within the UK | 134 |

Multiple transactions and related accounts | 136 |

Recommendation 13. | 137 |

Repayments to victims of fraud | 137 |

Recommendation 14. | 138 |

Historical crime | 138 |

No UK nexus | 139 |

Recommendation 15. | 140 |

Conclusion | 140 |

CHAPTER 8: CRIMINAL PROPERTY AND MIXED FUNDS | 142 |

Introduction | 142 |

The current law | 142 |

Evaluation of the current law | 144 |

Data analysis | 145 |

Consultation | 145 |

Option 1: The current law | 147 |

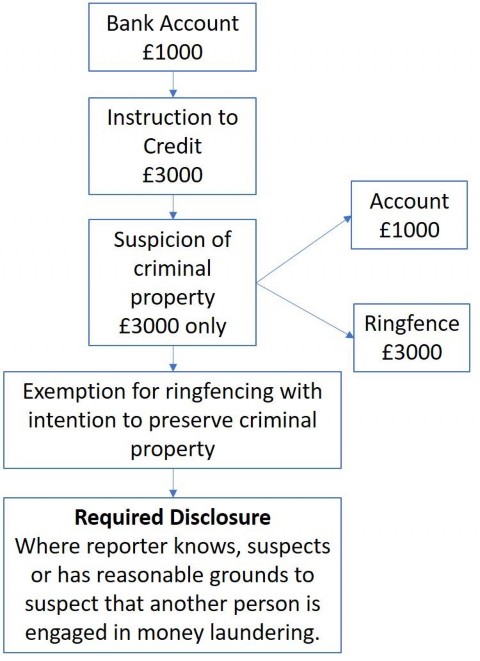

Option 2: Ringfencing under the proposed legislative exemption | 148 |

Drafting | 150 |

Analysis | 151 |

Recommendations for reform | 154 |

Recommendation 16. | 155 |

Recommendation 17. | 155 |

Recommendation 18. | 155 |

CHAPTER 9: INFORMATION SHARING | 157 |

Introduction | 157 |

The current law - voluntary information sharing | 158 |

Information sharing in relation to a suspicion | 158 |

Further information orders | 159 |

Data protection legislation | 160 |

Consultation | 160 |

How might further information sharing be achieved | 163 |

The Current law - JMLIT | 164 |

vii |

Public-private information sharing partnership 164

Consultation 165

Regulated sector participation 165

Law enforcement participation 166

Conclusion 167

CHAPTER 10: ENHANCING CONSENT 168

Introduction 168

Retaining the consent regime 168

Consultation 169

Analysis 171

Thematic reporting 171

Case study 173

Geographic Targeting Orders 173

Case study 174

Addressing problems with the current regime 174

Consultation 176

Analysis 178

Costs 178

Other arguments 180

Recommendations for reform 181

Recommendation 19. 182

CHAPTER 11: FUTURE REFORMS 183

Introduction 183

Corporate Criminal Liability 183

The current law 183

Evaluation of the current law 185

Consultation 187

Analysis 189

Conclusion 190

Jurisdiction, extraterritoriality and legal conduct overseas 191

Extraterritorial jurisdiction 191

Legal conduct overseas 193

SARs Reform Programme 195

CHAPTER 12: RECOMMENDATIONS 197

APPENDIX 1: NON-EXHAUSTIVE LIST OF GUIDANCE 203

viii

APPENDIX 2: LIST OF THOSE WHO RESPONDED TO THE

CONSULTATION PAPER 209

Members of the regulated sector 209

Government departments 209

Supervisory authorities, other appropriate bodies and trade organisations 209

Agencies, police and prosecuting authorities 210

Individuals, practitioners and academics 210

Non-governmental organisations 211

APPENDIX 3: STATUTORY MATERIAL 212

ix

x

Glossary1

Account Freezing Order – Account Freezing Orders allow a variety of law enforcement agencies to apply to the magistrates’ court to freeze bank accounts they suspect hold criminal property. The relevant provisions are set out in sections 303Z1 to 303Z3 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Action Fraud – Action Fraud is the reporting mechanism for the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau within the City of London Police.

Advisory Board – Advisory Boards are usually independent bodies with a remit to review or evaluate a particular part of the law.

Authorised disclosure – Authorised Disclosures are voluntary disclosures, triggered when a person2 has a suspicion that they have encountered criminal property and wishes to do one of the acts prohibited in sections 327-329 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. He or she may make an authorised disclosure to a constable (including officers in the UK Financial Intelligence Unit (“UKFIU”)), customs officer or nominated officer. Authorised disclosures are made by filing a suspicious activity report (SAR, see below).

Association of British Insurers – The Association of British Insurers (“ABI”) is the leading trade association for insurers and providers of long-term savings.

The British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association – The British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (“BPEVCA”) is the industry and public policy advocate for the private equity and venture capital industry.

Code of practice – A code of practice is an authoritative statement of practice to be followed in some field. It typically differs from legislation in that it offers guidance rather than imposing requirements.

Consent regime – The consent regime refers to the process by which a person who suspects he or she is dealing with the proceeds of crime can seek consent to complete a transaction by making an authorised disclosure to the United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit. No criminal offence is committed where an authorised disclosure is made and appropriate consent to proceed with an act otherwise proscribed by sections 327 to 329 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 is given.

1 These definitions are intended to provide a brief summary of key terminology used in this report. For detailed discussion of these terms, see Chapters 2 and 3 of CP 236 and for the legislative provisions please see Appendix 3.

2 In this report, although any individual may make an authorised disclosure, we will focus on individuals making disclosures which arise out of their employment within a bank or business, or in the course of providing a professional service or giving professional advice as this is the most common context in which reports are lodged.

Criminal property – Criminal property is defined in section 340 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 as property that constitutes a person’s benefit from criminal conduct (in whole or part and whether directly or indirectly) where the alleged offender knows or suspects that it constitutes or represents such a benefit.

Defence against Money Laundering – (“DAML”) The term used by the UKFIU to describe an authorised disclosure in which the suspicion relates to money laundering – see above, where a reporter seeks a defence to an offence under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Defence against Terrorist Financing - (“DATF”) of the term used by the UKFIU to describe an authorised disclosure in which the suspicion relates to terrorism financing – see above, where a reporter seeks a defence to an offence under the Terrorism Act 2000.

Debanking – The practice of withdrawing banking facilities from a customer due to the perceived risk he or she presents to the bank.

ELMER – refers to the computerised system used by the UKFIU to process SARs. Reports are stored on the ELMER database for six years and may be accessed by a law enforcement agency during that time.

Financial Action Task Force – The Financial Action Task Force (“FATF”) is an intergovernmental body whose objectives are to set standards and promote effective implementation of legal, regulatory and operational measures for combatting money laundering, terrorist financing and other related threats to the integrity of the international financial system.

Financial Conduct Authority – The Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) is the conduct regulator for 58,000 financial services firms and markets in the United Kingdom.

Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive – This is the fourth European Union directive to address the risk of money laundering.

Further Information Orders – Further Information Orders (“FIOs”) can be sought on application to the magistrates’ court. An FIO can require the person making a disclosure (to the United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit) or any person carrying on a business in the regulated sector to provide specified information, or any other information that the court deems appropriate, in relation to a matter arising from a disclosure under Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Geographic Targeting Order – A Geographic Targeting Order (“GTO”) is a specific form of thematic reporting, focussing on a particular location where a transaction or activity is occurring.

High street bank – A high street bank is a credit institution which offers banking services to the general public. The term is generally reserved for larger, more widespread organisations with multiple branches.

High value dealers – Under the Money Laundering Regulations, a high value dealer is any business or sole trader that accepts or make cash payments of

€10,000 or more (or equivalent in any currency) in exchange for goods.

Historical crime – For the purposes of this publication a “historical crime” refers to an offence perpetrated more than five years before an authorised disclosure was made to the United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit.

Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs – Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs (“HMRC”) is a non-ministerial department of the UK Government responsible for the collection of taxes, the payment of some forms of state support and the administration of other regulatory regimes.

Indictable offence – An indictable offence is an offence which, if committed by an adult, is triable on in the Crown Court before a judge and jury, whether it is exclusively so triable or triable either way.3

Home Office Circular – Home Office Circulars are documents used to communicate, or provide updates on Home Office policies.

Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Task Force – The Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Task Force (“JMLIT”) is a public-private partnership that facilitates information sharing between banks in the regulated sector and law enforcement agencies. It operates in accordance with the information gateway provisions contained in the Crime and Courts Act 2013.

Law enforcement agency - Law enforcement agencies (“LEA”) are organisations with responsibility for enforcing the criminal laws of the United Kingdom. In this context law enforcement agencies include, the National Crime Agency, the police and other bodies such as the Serious Fraud Office who investigate suspected money laundering and associated criminality.

Money Laundering Reporting Officer (“MLRO”) – Under FCA rules, a firm must appoint an individual as MLRO, with responsibility for oversight of its compliance with the FCA’s rules on systems and controls against money laundering. The job of the MLRO is to act as the focal point within the relevant firm for the oversight of all activity relating to anti-money laundering.4 The MLRO may also act as the “nominated officer”, an individual with responsibility within a firm, company or other organisation to submit SARs to the UKFIU (see below).

Money Service Business – A business which operates as a currency exchange office, transmits money (or any representation of monetary value) by any means or cashes cheques which are made payable to customers.5

3 Interpretation Act 1978, sch. 1.

4 Financial Conduct Authority Handbook SYSC 3.2.6IR and SYSC 3.2.6JG.

5 The Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017, SI 2017 No 692, Chapter 3.

Mandate – A service contract between a customer and their bank which gives the bank authority to act on the customer's behalf.

Moratorium period – if a request for consent is refused during the statutory seven-day notice period, a statutory moratorium period of 31 calendar days begins. This allows further time for investigation. The Criminal Finances Act 2017 amended Part 7 of POCA to empower a Crown Court judge to grant an extension to the moratorium period up to a further 186 days in total on application.6

Nominated Officers - The nominated officer’s obligation to disclose only arises where they receive a required disclosure from another person (pursuant to section 330 of POCA) informing them of a knowledge or suspicion of money laundering.7

National Crime Agency – The National Crime Agency is a non-ministerial government department with oversight of national law enforcement agencies in the United Kingdom. It is the UK's lead agency against organised crime; human, weapon and drug trafficking; cyber-crime; and economic crime that goes across regional and international borders, but can be tasked to investigate any crime.

Proceeds of Crime Lawyers Association – The Proceeds of Crime Lawyers Association (“POCLA”) is an association of lawyers established to foster and encourage best practice in matters involving the proceeds of criminal conduct.

Pecuniary advantage – In this report, a “pecuniary advantage” refers to a financial advantage (other than property) obtained through criminal conduct. Section 340 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 deems a person to have obtained a sum of money equivalent to any pecuniary advantage they have obtained.

Predicate offence – A criminal offence which generates the proceeds of crime that may become the subject of any of the money laundering offences.

Principal money laundering offences – Refers to the criminal offences in sections 327 to 329 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 that prohibit particular dealings with actual or suspected criminal property and can be contrasted with the failure to report offences.

Reporter - We use the term reporter to mean a person who has either an obligation to report under Part 7 of POCA or who makes a voluntary disclosure

6 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s335(6), 335(6A), 336A, B, C, and D and the Criminal Finances Act 2017, Part 1, s 10(2) (s 335(6A) in force, October 2017, subject to transitional provisions specified in SI 2017 No.991 reg 3(1)). See Home Office Circular 008/2018 [Criminal Finances Act: extending the moratorium period for suspicious activity reports]. See also CP 236 at para. 2.23.

7 A nominated officer is a person who is nominated within a firm, company or other organisation to submit suspicious activity reports on its behalf to the United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit.

seeking consent in order to protect themselves from a committing a money laundering offence under Part 7 of POCA.

Required disclosure – Refers to the statutory obligation to make a report where a person knows or suspects, or has reasonable grounds to know or suspect that a person is engaged in money laundering. A failure to make a required disclosure is a criminal offence for which reporters can be found personally liable.8 Required disclosures provide law enforcement agencies with intelligence and the opportunity to disrupt criminality.

Safe harbour – For the purposes of this report a “safe harbour” refers to the notion that compliance with relevant guidance should provide reporters with a defence to a criminal offence under Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Serious Organised Crime Agency – The Serious Organised Crime Agency (“SOCA”), a forerunner of the National Crime Agency, is a former non- departmental national law enforcement agency that operated from 2006 to 2013.

Spanish bullfighter issue – A shorthand reference for the application of money laundering provisions to the proceeds of an activity legal in a foreign jurisdiction, but illegal under the criminal law of the relevant part of the UK.

Suspicious Activity Report – Suspicious Activity Reports (“SARs”), are an electronic or paper document in which the reporter discloses their suspicions of money laundering to the UKFIU, in accordance with their obligations under sections 330 to 332 or voluntarily pursuant to 338 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Statutory guidance – A statute may empower a Minister to issue guidance about the operation of its provisions. Although such statutory guidance is not to be treated as legislation, it is capable of having a legal effect. The courts will give guidance produced under a statutory power greater weight than guidance produced voluntarily.

Supervisory authority – In this report a supervisory authority is a body with responsibility for supervising compliance with anti-money laundering legislation. Schedule 9, paragraph 4 to the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 lists 25 supervisory authorities.

The regulated sector – The regulated sector refers to those institutions specified in Schedule 9, paragraph 1 to the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (and corresponding provisions in the Terrorism Act 2000) which are subject to particular obligations under anti-money laundering legislation. This includes a broad range of sectors, such as credit institutions, those providing legal and accounting services and high value dealers.

8 Reporters who fail to submit a required disclosure will be liable unless they fall within one of the narrow exceptions to the failure to disclose offence. The exceptions available will vary depending on the status of the reporter and whether they were operating within or outside of the regulated sector.

Thematic reporting – Thematic reporting is an administrative approach to reporting suspicious activity which requires reports to be made based on set criteria irrespective of suspicion.

Terrorist financing – Terrorist financing concerns money or other property likely be used for the purposes of terrorism and any proceeds of the commission of acts of terrorism or acts carried out for the purposes of terrorism.

United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit – The United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit (“UKFIU”) sits within the National Crime Agency and is responsible for receiving, analysing and disseminating suspicious activity reports.

Value transfer system – A value transfer system refers to a mechanism, or network of people, which operates outside of formal banking channels to facilitate the transfer of goods and money directly, even to users in remote locations.

Chapter 1: Introduction

THE PROJECT AND OUR TERMS OF REFERENCE

In 2017, the Law Commission agreed with the Home Office to review and make recommendations for reform of particular aspects of the anti-money laundering regime in Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (“POCA”) and of the counter-terrorist financing regime in Part 3 of the Terrorism Act 2000 (“TA”). This followed a discussion of ideas for inclusion in the Law Commission’s Thirteenth Programme of Law Reform.

The primary purpose of the review is to improve the prevention, detection and prosecution of money laundering and terrorism financing in the United Kingdom (“UK”).1 However, our review is limited in scope. Our aim is to address systemic problems in the suspicious activity reporting process, in particular the “consent regime”, to ensure that it is proportionate and efficient.

We agreed the following Terms of Reference with the Home Office:

The review will cover the reporting of suspicious activity in order to seek a defence against money laundering or terrorist financing offences in relation to both regimes.

Specifically, the review will focus on the consent provisions in sections 327 to 329 and sections 335, 336 and 338 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, and in sections 21 to 21ZC of the Terrorism Act 2000.

The review will also consider the interaction of the consent provisions with the disclosure offences in sections 330 to 333A of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 and sections 19, 21A and 21D of the Terrorism Act 2000.

To achieve that purpose, the review will analyse the functions of, and benefits and problems arising from, the consent regime, including:

the defence provided by the consent regime to the money laundering and terrorist financing offences;

the ability of law enforcement to suspend suspicious transactions and thus investigate money laundering and restrain assets;

the ability of law enforcement to investigate, and prosecutors to secure convictions, as a consequence of the wide scope of the money laundering and terrorist financing offences;

1 It should be noted throughout this report that the Law Commission’s remit covers England and Wales only.

the abuse of the automatic defence to money laundering and terrorist financing offences provided by the consent provisions;

the underlying causes of the defensive over-reporting of suspicious transactions under the consent and disclosure provisions;

the burden placed by the consent provisions and disclosure provisions on entities under duties to report suspicious activity; and

the impact of the suspension of transactions under the consent provisions on reporting entities and entities that are the subject of reporting.

The review will then produce reform options that address these issues. In doing so, the review will take into consideration the Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive and the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force, as well as the effect of new legislation or directives, such as the Criminal Finances Act 2017, the Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive, the Payment Services Directive 2, and the General Data Protection Regulation.

The review will also gather ideas for wider reform which may go beyond the focussed Terms of Reference noted above. These will be intended to provide a basis for future development of the anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing regimes.

Before we provide a general overview of our recommendations and the structure of the report, we begin with a brief explanation of what money laundering is. We also explain how the disclosure of information about individuals and businesses by the private sector is linked to preventing and detecting the flow of criminal funds in the UK.

MONEY LAUNDERING AND THE UK’S LEGAL RESPONSE

Money laundering, in very general terms, describes the processing of criminal property in order to disguise its illegal origin. As Professor Liz Campbell observes:

There is a lack of clarity as to the scope of the concept of money laundering, rendering it difficult to study and to measure. Legally the term encompasses not only the orthodox understanding of the “cleaning” of assets, but also their concealment, conversion, transfer and removal.2

The Government’s Serious and Organised Crime Strategy, published in November 2018, described the problem of illicit funds faced by the UK:

…illicit finance involves the holding, movement, concealment, or use of monetary proceeds of crime that has an impact on UK interests. Organised crime groups and corrupt elites launder the proceeds of crime through the UK to fund lavish lifestyles and reinvest in criminality.

2 See Campbell, L, Dirty Cash (money talks): 4AMLD and the Money Laundering Regulations 2017 [2018] Crim LR, 103.

The vast majority of financial transactions through and within the UK are entirely legitimate, but its role as a global financial centre and the world’s largest centre for cross-border banking makes the UK vulnerable to money laundering. There is a realistic possibility that the scale of money laundering impacting the UK annually is in the tens of billions of pounds.3

The UK’s anti-money laundering framework4

As we explained in our Consultation Paper, our focus in this review is on four aspects of the existing anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing regimes in the UK.

Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 created:

three offences of money laundering which apply to the proceeds of any criminal offence;

legal obligations to report suspected money laundering bolstered by criminal offences for failures to disclose;

a complementary “consent regime” of authorised disclosures (Defence Against Money Laundering or (DAML SARs)); this offers the UKFIU (“UKFIU”), which is part of the National Crime Agency (“NCA”) the opportunity to grant or refuse consent to proceed with a transaction.5 Where consent is granted, the reporter is protected from criminal liability for what might otherwise have been a money laundering offence under sections 327 to 329 of POCA; and

a prohibition on warning any person not authorised to receive the information that a report had been made to the authorities or an investigation had begun (“tipping off”).

A parallel regime operates in relation to counter-terrorist financing and is contained in Part 3 of the Terrorism Act 2000. As we identified in our Consultation Paper, our focus has primarily been on Part 7 of POCA as, first, the number of terrorist financing SARs in which consent was sought is relatively small and, secondly, stakeholders were broadly in agreement that the issues identified in relation to the consent regime under Part 7 of POCA are not replicated in relation to counter-terrorist financing.6

3 HM Government, Serious and Organised Crime Strategy (November 2018), pp 13-14.

4 This is a non-exhaustive summary of the current law. For a fuller summary please see CP 236 and for the legislative provisions please see Appendix 3.

5 Deemed consent may also arise when (1) an individual who makes an authorised disclosure does not receive notice that consent to the doing of the act is refused before the end of the statutory seven-day notice period. See Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s335(2) and 335(3); or (2) an individual who makes an authorised disclosure does receive notice of refusal of consent during the notice period but the moratorium period has expired (subject to any application to extend the moratorium period). See Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 335(2) and 335(4).

6 For a summary of the relevant provisions under the Terrorism Act 2000, see CP 236, Chapter 3.

The anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing framework is supplemented by the Financial Action Task Force Recommendations and European Union (“EU”) Directives.7

The money laundering offences

Part 7 of POCA creates three principal money laundering offences.8

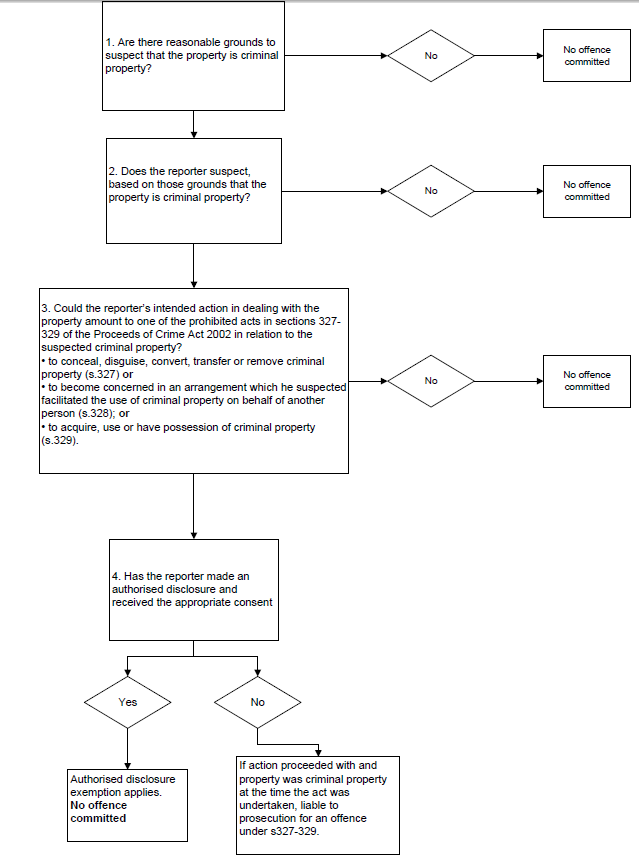

The offences in sections 327, 328 and 329 of POCA are intended to criminalise specific acts of money laundering. A person commits an offence of money laundering if he or she:

conceals; disguises; converts; transfers; or removes criminal property from England and Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland; or9

enters into or becomes concerned in an arrangement which he or she knows or suspects facilitates (by whatever means) the acquisition, retention, use or control of criminal property by or on behalf of another person;10 or

acquires criminal property; uses criminal property; or has possession of criminal property.11

There are a number of legal exemptions and defences to the principal money laundering offences which were discussed in detail in our Consultation Paper.12 However, our focus is on the consent regime which is underpinned by the authorised disclosure exemption. This exemption applies to any individual but for the purposes of this report, we focus on how the exemption relates in practical terms to individuals in banks and businesses who encounter suspected criminal property. In the next section, we deal with some of the key concepts in Part 7 of POCA and look at the legislative framework of the disclosure regime.

7 Domestic anti-money laundering provisions have been supplemented by successive EU Directives on money laundering. These have been implemented by Regulation in the UK.4AMLD was agreed in June 2015 and implemented in the Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017 (“The Money Laundering Regulations 2017”). The Money Laundering Regulations 2017 create a system of regulatory obligations for businesses under the supervision of the Financial Conduct Authority and the relevant professional and regulatory bodies recognised within the Regulations. Additionally, the UK is one of the founding members of Financial Action Task Force, an inter- governmental body established in 1989 to set standards in relation to combatting money laundering and terrorist financing. Its recommendations are recognised as the international standard for anti-money laundering regulation. The recommendations set out a framework of measures to be implemented by its members and monitored through a peer review process of mutual evaluation.

8 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340(11) and ss 327 to 329.

9 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 327.

10 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 328.

11 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 329.

12 See para. 2.69 of CP 236.

Key concepts

There are three important concepts common to the money laundering offences which are examined in detail below: “criminal property”, “suspicion” and “criminal conduct”.

Each of the principal money laundering offences is conditional upon the action in question (eg transferring or using) being done in relation to “criminal property”. If the property is not criminal in nature, the principal offences in sections 327 to 329 of POCA are not committed.

For property to be “criminal”, for the purposes of Pt 7 of POCA, it must satisfy two conditions:

it must constitute a person’s benefit from criminal conduct or represent such a benefit (in whole or in part and whether directly or indirectly); and

the alleged offender must know or suspect that it constitutes or represents such a benefit.13

A person will be considered to have benefited from criminal conduct if he or she obtains some property (or other financial advantage) as a result of or in connection with the conduct.14

Criminal property has been broadly defined by the legislation. Whilst criminal proceeds may take the form of cash, more sophisticated levels of laundering are also accounted for. The definition would include a house or a car purchased with the proceeds of criminal activity. Criminal property is not restricted to physical money in the form of notes and coins. A credit balance on a bank account or equity shares in a company would fall within this wide definition.15

Suspicion is a key component of the money laundering offences. It is the minimum mental state required for the commission of an offence under sections 327, 328 and

329.16 The fact that a person suspects that property is criminal may, depending on the circumstances, also trigger a reporting obligation under sections 330, 331 and 332 which will be considered below. In the absence of a statutory definition or guidance, it has been left to the courts to determine what “suspicion” means.

In the context of money laundering, the leading authority on the meaning of suspicion is R v Da Silva.17 In this case, the Court of Appeal considered the correct interpretation

13 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340(3), (4).

14 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340(5) to (7).

15 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340(9).

16 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340(3)(b); a person must suspect that the property in question is criminal property.

17 [2006] EWCA Crim 1654, [2006] 2 Cr App R 35.

of suspicion within the meaning of section 93A(1)(a) of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 (the predecessor to the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002):

What then does the word “suspecting” mean in its particular context in the 1988 Act? It seems to us that the essential element in the word “suspect” and its affiliates, in this context, is that the defendant must think that there is a possibility, which is more than fanciful, that the relevant facts exist. A vague feeling of unease would not suffice. But the statute does not require the suspicion to be “clear” or “firmly grounded and targeted on specific facts”, or based upon “reasonable grounds”.18

Criminal conduct is defined broadly as conduct which “constitutes an offence in any part of the United Kingdom”.19 The UK’s approach to money laundering is described as an “all-crimes” approach. That means simply that laundering the proceeds of any crime of any value whatsoever will amount to the offence.20 It is not limited to serious crimes, certain types of offending, or those punishable with imprisonment.

Criminal conduct is conduct which:

constitutes an offence in any part of the United Kingdom; or

would constitute an offence in any part of the United Kingdom if it occurred there.21

Conduct abroad which would be legal in that country but unlawful somewhere in the United Kingdom is sufficient. For example, conduct that took place in Egypt might amount to fraud in the UK and would therefore be criminal conduct for the purposes of section 340 of POCA. However, the limited exceptions to this will be discussed further at paragraph 2.73 below.22

There is no temporal limit to criminal property; it does not matter whether the criminal conduct occurred before or after the passing of POCA. If the property is generated by criminal activity at any stage, its use in any of the ways described in sections 327 to 329 is proscribed. For example, if an offender stole a painting and kept it for decades, it would remain criminal property regardless of the passage of time. It is an “all-crimes” “for all time” approach.

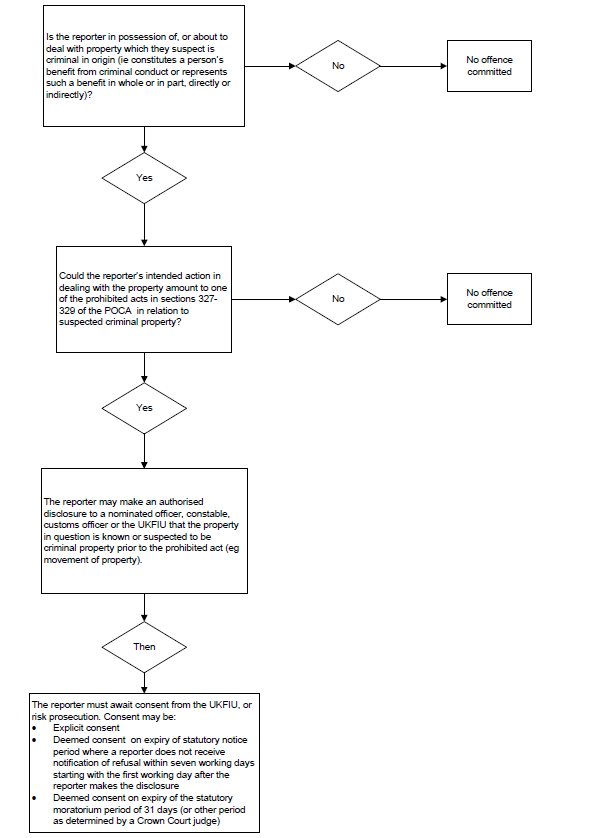

Authorised disclosures

An individual who suspects that they are dealing with the proceeds of crime can seek consent to complete a transaction by disclosing their suspicion to the UK Financial Intelligence Unit (“UKFIU”), a function as part of the National Crime Agency (“NCA”). A

18 [2006] EWCA Crim 1654, [2006] 2 Cr App R 35.

19 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340

20 Theft Act 1968, s 12(5) and (6). This offence is punishable on summary conviction with a fine not exceeding level 3 on the standard scale.

21 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 340.

22 See Serious Organised Crime and Policing Act 2005, s 102 and the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Money Laundering: Exceptions to Overseas Conduct Defence) Order 2006, SI 2006 No 1070.

money laundering offence is not committed under sections 327 to 329 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 where a person makes an “authorised disclosure” to the authorities and acts with “appropriate consent”. The money laundering offences are widely drawn and the fault threshold for criminality, currently set at suspicion, is a low one. In addition, the all-crimes approach means that the proceeds of any criminal activity are caught by the offences in 327 to 329 of POCA. To balance this, the opportunity to obtain consent by making an authorised disclosure offers comfort and necessary legal protection, particularly to those who may, in the course of their profession, encounter property which they are suspicious may have criminal origins. Without such an exemption, such a low threshold would have a far-reaching impact and potentially place a large number of people at risk of criminal liability. For example, this exemption would apply where bank official suspects criminal property is in an account. That fact can be disclosed to the authorities and consent obtained to continue to process relevant transactions. An employee of a bank may frequently encounter situations in which they suspect property is criminal in origin and the authorised disclosure exemption mitigates the effect of such wide offences.

For a disclosure to be authorised, it must be made to either a nominated officer (a person nominated within a company, firm or other organisation to receive reports of suspicious activity), a constable, or a customs officer. The matter disclosed is that the property is known or suspected to be criminal property.

The timing of the disclosure is important. To benefit from the exemption, the disclosure must be made either:

before the transaction is undertaken;

during a transaction if the reporter only suspected that they were dealing with criminal property once they had begun to handle the property; or

after the fact, if there was a reasonable excuse.23

If the disclosure is made during or after the transaction has taken place, the disclosure must be made on the reporter’s own initiative and as soon as is practicable after the knowledge or suspicion arose.24

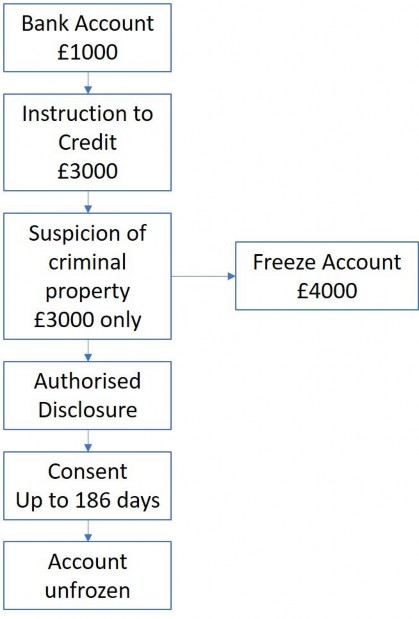

In broad terms, in return for their authorised disclosure, if consent is not refused by the UKFIU, the reporter receives protection against criminal liability for a money laundering offence. Therefore, authorised disclosures have a dual function: they both provide intelligence to law enforcement agencies (police forces in the relevant region), and may shield the reporter from relevant criminal liability. This process is known as the “consent regime”. For example, a bank may become suspicious that funds in a customer’s account represent the proceeds of crime. If the customer asks the bank to make a payment in accordance with their mandate, the bank will make a disclosure to the UKFIU to obtain consent to proceed with the transaction. Provided consent is not refused, the reporter will be brought within a statutory exemption which effectively

23 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, ss 327(2)(a), 328(2)(a), 329(2)(a) and 338.

24 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 338(3)(c).

precludes any future money laundering charge against the reporter in relation to that transaction.

The UKFIU facilitates the disclosure process by acting as the intermediary for intelligence between the private sector and law enforcement agencies. When an authorised disclosure is submitted, it is analysed by UKFIU and made available to law enforcement agencies who will investigate and decide whether to take further action. Because of the time it takes to conduct an investigation and intervene to preserve criminal assets, the authorised disclosure scheme requires the reporter to refrain from processing the transaction as they will not be protected by the statutory exemption if they undertake one of the prohibited acts in section 327-329 without appropriate consent. This allows time for the UKFIU to take a fully informed decision on whether to consent to the transaction proceeding.25

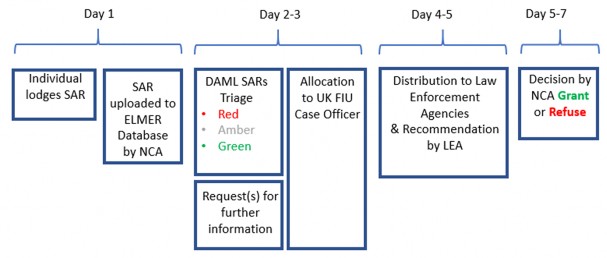

Life of an authorised disclosure26

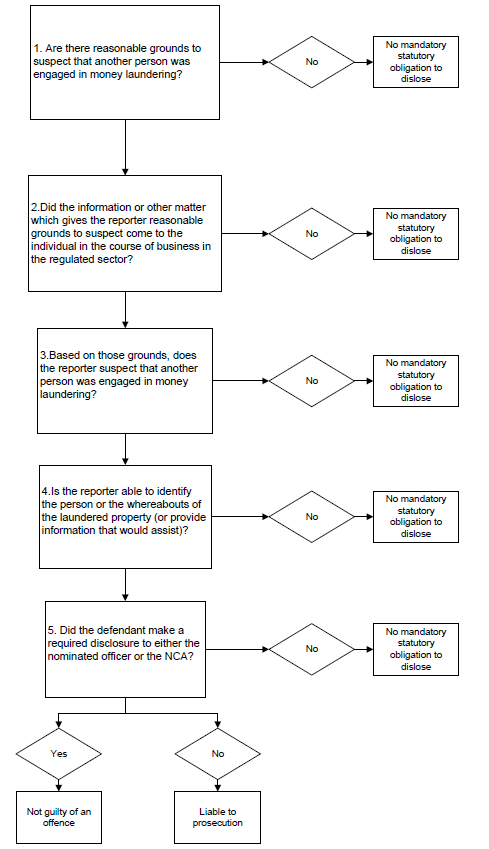

Required disclosures

The legislation distinguishes between two types of disclosure that are made to the UKFIU: “required disclosures” and “authorised disclosures.”27 The important distinction is between whether the disclosure is required by law or whether the reporter wishes to protect themselves from a potential money laundering charge and makes a voluntary disclosure. If a reporter fails to lodge a SAR in accordance with their obligations under Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, he or she may be liable for prosecution for

25 UKFIU may give appropriate consent, refuse consent or not give notice of either a grant or refusal in which case Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, ss335(2)-(4) apply. See also Proceeds of Crime Act, 2002, s 336(5)-(6).

26 This diagram is intended to provide a general description of the process, it may not be representative of all cases. For example, a decision may be made prior to days 5 to 7: Deemed consent may also arise when (1) an individual who makes an authorised disclosure does not receive notice that consent to the doing of the act is refused before the end of the statutory seven-day notice period. See Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s335(2) and 335(3); or (2) an individual who makes an authorised disclosure does receive notice of refusal of consent during the notice period but the moratorium period has expired (subject to any application to extend the moratorium period). See Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 335(2) and 335(4).

27 See also voluntary information sharing provisions in Criminal Finances Act 2017, ss 339ZB-339ZG and Terrorism Act 2000, ss 21CA-21CF.

one of three disclosure offences, depending on his or her status and whether they were acting within or outside the regulated sector.

As outlined above, a reporter is obliged to disclose their suspicion that another person is engaged in money laundering. This is known as a “required disclosure”. If a disclosure is not made, the person who ought to have reported is liable to be prosecuted for a criminal offence.

The regulated sector is defined in Schedule 9 to the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 and the original definition has been amended by various legislative provisions and EU law. Broadly, the regulated sector encompasses businesses where their activity presents a high risk of money laundering or terrorist financing. Businesses may be included within the definition by virtue of the type of activity they undertake. For example, the acceptance by a credit institution of deposits or other repayable funds from the public, or the granting by a credit institution of credits for its own account brings banks into the regulated sector. A firm of solicitors who undertake conveyancing work would be included as they are “participating in the buying or selling of real property” and would fall within the definition in Schedule 9. In addition, those who trade in goods are brought within the regulated sector whenever a transaction involves the making or receipt of a payment or payments in cash of at least €10,000 in total. This threshold applies whether the transaction is executed in a single operation or in several operations which appear to be linked, by a firm or sole trader who by way of business trades in goods. However, as the nature of the activity is relevant, it is possible that a business may undertake some work which falls within the definition of the regulated sector and other work which does not.

Failure to disclose by those working within the regulated sector

Section 330 applies to a person acting in the “course of a business in the regulated sector” who fails to make a “required disclosure”. Disclosure is required where four conditions are met:

he or she “knows or suspects” or has “reasonable grounds for knowing or suspecting”) that another person is engaged in “money laundering”;

the information or other matter on which his or her knowledge or suspicion is based or provides reasonable grounds for suspicion must have come to him or her in the course of business in the regulated sector;

he or she can identify the person engaged in money laundering or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property; and

he or she believes, or it is reasonable to expect him or her to believe, that the information or other matter will or may assist in identifying the person or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property.

The information which the reporter is required to disclose is:

the identity of the person, if he or she knows it;

the whereabouts of the laundered property, so far as he or she knows it;

information that will or may assist in identifying the other person or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property.

An offence is committed when a person does not make the required disclosure to either the nominated officer or the UK Financial Intelligence Unit as soon as is practicable after the information comes to him or her.

Failure to disclose by nominated officers working in the regulated sector

Section 331 applies to “nominated officers” who operate in the “regulated sector”. A nominated officer is a person who is nominated within a firm, company or other organisation to submit SARs on its behalf to the United Kingdom Financial Intelligence Unit. If an employee has a suspicion, the nominated officer must evaluate the information reported and decide whether, independently, he or she has knowledge, or a suspicion or should have reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering based on what he or she has been told.

The nominated officer’s obligation to disclose arises where he or she receives a required disclosure from another person (pursuant to section 330 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002) informing them of a knowledge or suspicion of money laundering. The nominated officer must decide if he or she is obliged to lodge a SAR by considering whether the following three conditions apply:

He or she knows or suspects or has reasonable grounds to know or suspect, that another person is engaged in “money laundering”; or

the information or other matter on which their knowledge or suspicion is based, or which gives them reasonable grounds for suspicion, came to them in consequence of a disclosure made under section 330; and

he or she:

knows the identity of the person engaged in money laundering or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property, in consequence of a disclosure made under section 330;

can identify the person or whereabouts of the laundered property can from the information of other matter; or

they believe, or it is reasonable to expect them to believe, that the information or other matter will or may assist in identifying the person or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property.

The information which the reporter is required to disclose is:

the identity of the person, if disclosed in the section 330 report;

the whereabouts of the laundered property, so far as disclosed in the section 330 report; and

information that will or may assist in identifying the other person or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property.

An offence is committed when a person does not make the required disclosure to either the nominated officer or the UKFIU as soon as is practicable after the information comes to him or her.

Failure to disclose by other nominated officers

Section 332 applies to nominated officers other than those acting within the regulated sector. For example, a high street chain of jewellery shops may typically conduct transactions which fall below the transaction threshold of 10,000 Euros necessary to bring them within the regulated sector. If the nominated officer of this high street chain fails to make a required disclosure in accordance with section 332, he or she is at risk of criminal liability under that section.

Disclosure is required where the following three conditions are made out:

he or she knows or suspects that another person is engaged in money laundering;

the information or other matter on which his or her knowledge or suspicion is based came to him or her in consequence of a disclosure either under section 337 (a protected disclosure) or 338 (an authorised disclosure); and

he or she:

knows the identity of the person, or the whereabouts of any laundered property in consequence of the disclosure he or she received; or

the person, or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property, can be identified from the information or other matter received; or

he or she believes, or it is reasonable to expect him or her to believe, that the information or other matter will or may assist in identifying the person or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property.

The information which the reporter is required to disclose is:

the identity of the person, if disclosed to him or her;

the whereabouts of the laundered property, so far as disclosed to him or her;

any information or matter disclosed to him or her that will or may assist in identifying the other person or the whereabouts of any of the laundered property.

An offence is committed when a person does not make the required disclosure to either the nominated officer or the UKFIU as soon as is practicable after the information comes to him or her.

Tipping-off

Part 7 of POCA also includes provisions designed to ensure the subject of a SAR is not made aware of any ongoing investigation into his or her finances. In our Consultation Paper we noted, for example, if a bank employee were to inform the subject of an investigation that a SAR had been submitted to the authorities, this could seriously affect the outcome of any investigation. It may also place the reporter in jeopardy if only a small circle of people could have known about the transaction or provided particular matters of personal information. Whilst certain disclosures are permitted, others are prohibited if they risk “tipping-off” a suspect in a criminal investigation.

Under section 333A of POCA, it is an offence to disclose:

the fact that a disclosure (a suspicious activity report) under Part 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 has been made; or

that an investigation into allegations of a money laundering offence is being contemplated or is being carried out.

In addition, the following two conditions need to be satisfied:

the disclosure must be likely to prejudice any investigation; and

the information on which the disclosure is based must have come to the person in the course of business in the regulated sector.28

Section 21D of the Terrorism Act 2000 creates an offence for tipping-off in relation to counter-terrorist financing investigations.

PROBLEMS WITH THE CURRENT LAW

Retaining consent

Although it was not within the scope of our Terms of Reference to consider removal of the consent regime, we did ask consultees for their views on the system. In our Consultation Paper we set out the arguments in favour of, and the issues created by, the consent regime. We asked consultees whether they believed that the consent regime should be retained. If not, we asked whether consultees could conceive of an alternative regime that would balance the interests of reporters, law enforcement agencies and those who are the subject of disclosures.

The overwhelming majority of consultees who replied to this question did not think that the regime should be removed or replaced altogether. This confirmed our own perception that the system serves a useful function, but is in need of improvement.

In light of our analysis and the overwhelming support amongst consultees, we recommend retention of the consent regime with improvements to render it more efficient and effective.

28 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, s 333A.

Recommendation 1.

1.52 We recommend that the consent regime is retained.

The need for a balanced regime

The disclosure regime is required to perform a difficult balancing act between the interests of law enforcement agencies, reporters and those who are the subject of a SAR (for example, the bank customer whose account is frozen). Northumbria University’s Financial Compliance Research Group response summarised the competing interests which must be balanced:

We believe there to be a fundamental tension between the objectives and requirements of those tasked with submitting SARs and those seeking to make use of the information contained within them. The challenge of the proposed reforms will be to deliver a system that achieves objectives that may not be mutually compatible, namely, to be less burdensome and costly for the regulated sector but to provide maximum usefulness to law enforcement.

Many stakeholders we met with were concerned that the balance is not currently being struck correctly.

In our Consultation Paper we recognised that obliging those with a reporting obligation to file a SAR whenever they have a “suspicion” means that the trigger for reporting is a light one.29 In principle this provides considerable benefit to law enforcement agencies, as it maximises the amount of information they are likely to receive. However, there is currently no means of ensuring that the burden of reporting is proportionate to the gravity of the offence, the value of the criminal property and the benefit to law enforcement agencies of this intelligence. This is problematic as resources are finite. The burden on those who are obliged to file reports is substantial. The burden on those whose accounts and transactions are frozen pending review is also very significant.30 It undermines the aim of achieving a truly risk-based approach.

In our Consultation Paper we identified a number of pressing problems which arise from the operation of the disclosure regime:

Complying with reporting obligations is expensive. UK Finance (formerly the British Bankers’ Association), a trade association representing the banking and finance industry operating in the UK, estimates that its members are spending at least £5 billion annually on core financial crime compliance.31

29 Proceeds of Crime Act s 330; a report may also be triggered if an individual working in the regulated sector, as defined in sch 9 to the POCA knows or has reasonable grounds for knowing or suspecting that another person is engaged in money laundering, or related criminality.

30 See Chapter 5.

31 The British Bankers’ Association (now UK Finance) estimated that its members spend at least £5 billion annually on core financial crime compliance, https://www.bba.org.uk/policy/bba-consultation-responses/bba-

The burden on the reporters is compounded since there are common misunderstandings and a lack of clarity around reporting obligations, these arise because of the complexity of the provisions and the absence of a single definitive source of guidance on the law. This can result in wasted time for both the reporter and for those processing SARs.

Defensive reporting arises from the risk of personal criminal liability for either a money laundering offence or a failure to provide information to the authorities. It can also arise from concern of being criticised by a regulatory body. This is exacerbated when reporters lack clarity concerning their obligations. Defensive reporting or reporting where it is unnecessary creates a larger volume of poor quality reports.

Reporting and assessing authorised disclosures is a resource-intensive process, requiring analysis and administration by both the reporter and the UKFIU. Poor quality authorised disclosures and those which are unlikely to be of assistance to law enforcement divert resources and attention away from their ability to tackle serious and organised crime.

Disclosures can have severe consequences for the subject of the report. Because a transaction is paused while the UKFIU reaches a decision on consent the subject will in all likelihood be unable to access their funds for that period of time.

Quality or quantity?

In the Consultation Paper we highlighted concerns from a cross-section of stakeholders that there were problems with the quality of disclosures made to the UKFIU. While there is an understandable desire among those working in law enforcement to maximise the amount of intelligence and raw data they receive, a large volume of SARs does not guarantee quality of intelligence. As the Proceeds of Crime Lawyers Association (“POCLA”) noted in its response:

the danger of casting the net this wide, is that valuable resources are deployed trawling through low grade material, allowing the larger fish and their associated predators to escape detection.

This concern has been echoed by Ben Wallace MP, the Minister of State for Security at the Home Office, who explained to the Treasury Committee that SARs reform was designed to deliver “quality not quantity of SARs”.32

We have had clear confirmation from law enforcement agencies that SARs are a vital source of intelligence. High quality SARs – in other words SARs which are data rich, and are submitted to the UKFIU in a format which is easy to process - can provide evidence of money laundering in action. Furthermore, they are one of the primary methods of sharing information to produce intelligence for law enforcement agencies to investigate and prosecute crime more generally. All SARs may provide raw data,

response-to-cutting-red-tape-review-effectiveness-of-the-uks-aml-regime/ (Last visited 21 May 2019); this figure is not limited to compliance generated by the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 ss 327-9 and 330-332.

32 Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP’s oral evidence to the Treasury Committee, Economic Crime HC 940 (31 October 2018).

such as a name or phone number, which may assist in the investigation and prosecution of a crime. Inferior quality SARs, in other words SARs which contain little or no data or are submitted in an inadequate format, are inevitably less valuable. They are more time-intensive to process, can contribute to delay in the system and may ultimately remain of little value to law enforcement agencies.33

Our focus throughout this project has been on identifying measures which can assist to strike the right balance between the quality of intelligence provided in disclosures and the burdens on those who submit and assess reports to improve the overall efficiency of the system. We are also concerned to ensure that the effect of a SAR on its subject is considered.

HISTORY OF THE PROJECT

Consultation

Work began on the project in February 2018. We engaged with a wide range of stakeholders. We heard first-hand from those working within the system about how the consent regime operates. We met with staff at the UKFIU, representatives from law enforcement agencies, officials from government departments, the judiciary, prosecutors, supervisors and reporting entities from across the regulated sector.

We also heard directly from practitioners who have represented individuals and entities who have been the subject of a disclosure, as well as those who have represented the NCA or law enforcement agencies in related proceedings. We learned of the personal experiences of those who had a personal or business account frozen from the subject of a disclosure whose accounts were subsequently re- opened.34

Additionally, we sought input from leading academics in this field on how the existing system might be improved. In total, we met with over 60 individuals with relevant experience of the consent regime in practice or from their own research.

We held a public symposium on 6 July 2018 at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies. This was attended by over 100 people including anti-money laundering professionals, academics, practitioners, civil servants and individuals who work in law enforcement, as well as staff from the NCA and the UKFIU.

We published our Consultation Paper on 20 July 2018. It generated considerable interest and stimulated debate on the efficiency and efficacy of the consent regime.

The consultation period ran until 5 October 2018. In total we received 56 consultation responses. These responses came from:

12 entities in the regulated sector;

33 The UKFIU waste valuable time and resource chasing reporters for making requests for further information; Anti-Money Laundering: the SARs Regime, Law Comm Consultation Paper 236 (2018) (“CP 236”) para 1.25.

34 For example, the consultation response of David Lonsdale.

19 supervisory authorities, other appropriate bodies or trade organisations;

five police and prosecuting authorities;

16 individuals, practitioners and academics;

three non-governmental organisations; and

a joint response from the Home Office and HM Treasury.

We draw upon the valuable information and comments in these consultation responses throughout this report.

The SARs Reform Programme

Our work is separate from but complementary to that of the SARs Reform Programme. That is a public-private partnership between the Home Office, the NCA and UK Finance. This project will make proposals for operational reform, including improvements to IT systems, to make use of modern technology and data analytics software.35 Throughout the duration of our project we have been mindful of the work of the SARs Reform Programme. Their operational review of SARs has the same stakeholders in common as our legislative review of Part 7 of POCA. We have therefore aimed to ensure that our proposals are broadly aligned where there may be scope for overlap. This is to ensure that that our recommendations for reform are relevant, realistic and have the support of those that they may affect.

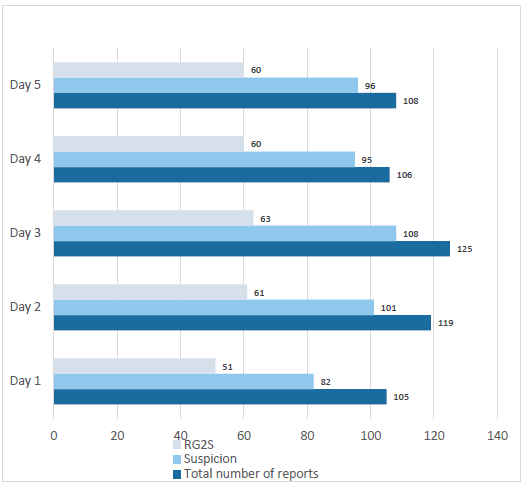

Purpose of data analysis

In our Consultation Paper we drew attention to the large volume of SARs, of which a significant proportion are authorised disclosures. We also observed that there is anecdotal evidence from stakeholders suggesting that the quality of disclosures is poor in some cases. We identified four principal reasons why the quality of reports might be affected:

a low threshold of culpability for the principal money laundering offences. The reporter is exposed to criminal liability for a money laundering offence carrying a significant maximum penalty of imprisonment based on his or her mere suspicion of the property being criminal;

individual criminal liability. The criminal liability of the reporter is personal; it is not the liability of the organisation for which they work. We were told that the combined effect of a low threshold and individual criminal liability is, understandably, an overly cautious approach to reporting. In some circumstances reporting is defensive in nature rather than reflecting a true assessment of the risk of money laundering in any given transaction;

confusion as to obligations. Reporters are faced with a complex set of inter- related reporting obligations with required and authorised disclosures requiring different approaches; and

35 National Crime Agency, Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) Annual Report (2018), p 2.

confusion as to the concept of suspicion. Some reporters struggle with applying the nebulous concept of suspicion. Consultees told us that the overall quality of the SAR is diminished when reporters do not understand the concept of suspicion. Many SARs fail to provide relevant information that will assist law enforcement agencies in a presentable, easy-to-read format to enable swift action.36

We made a number of provisional proposals designed to improve the quality of intelligence disclosed to law enforcement agencies and as a consequence, enhance the overall efficiency of the consent regime. Our analysis of SARs was designed to test the impact that our provisional proposals may have on the assumptions above and the scope and volume of reporting generally.

In undertaking this analysis our broad objectives were to quantify and measure:

the proportion of authorised disclosures made in accordance with the current law;

the proportion of authorised disclosures which fail to meet the threshold and are therefore made unnecessarily; and

the proportion of authorised disclosures which could be improved upon or enhanced to provide focussed and well-presented intelligence which meets the needs of law enforcement agencies.37

Although the focus of our research was on authorised disclosures we performed a smaller-scale analysis of required disclosures for comparison. However, we note that required disclosures are not time-sensitive and resource-intensive in the same way as authorised disclosures as they do not require any decision to be taken on consent. An additional objective in respect of required disclosures was to establish how rich they were as an intelligence source and whether our proposals could assist law enforcement agencies by improving the quality of intelligence that is provided.

Data analysis

In our Consultation Paper we highlighted the paucity of data available with which to measure the effectiveness of the regime. There had been no independent analysis of the quality of disclosures made to the UKFIU. This concern was echoed by many consultees. POCLA observed in its response:

As the Law Commission points out, the effectiveness of the current regime is unsupported by the evidence. The purpose of reporting is essentially two-fold. First to provide the authorities with information and intelligence on money laundering and financial crime. Secondly, to give the authorities an opportunity to freeze or restrain assets.

36 CP 236, para 4.16.

37 We base this part of our analysis on the categories of SARs identified by reporters, law enforcement agencies and the UKFIU as providing little intelligence value in Chapter 11 of CP 236.

As to the first purpose, no data is available at all. As to the second, we are told that 634,113 reports were made between October 2015 and March 2017. Of those, only 1,558 were requests for consent to act where consent was refused. It is not clear from the statistics how many of these refusals resulted in freezing or, more importantly, prosecution and confiscation/recovery of assets, but the NCA identify only 36 cases where arrests were effected. It must be inferred that a substantial portion of those 36 cases did not result in prosecutions, convictions and asset confiscation. Consequently, the objectives of the reporting regime fall well short of being met.

Tristram Hicks (former Detective Superintendent on the national Criminal Finance Board), submitted a joint response with Ian Davidson (former Detective Superintendent with national financial investigation responsibility) and Professor Mike Levi, Cardiff University. They recognised that there was a shortage of evidence on the utility of SARs, but warned against concluding on that basis that the system was not working:

We recognise that excellent results from some SARs have not been fed back adequately to the reporting sector by the NCA (or its predecessor bodies). This has perhaps engendered a lack of confidence in their value and may have contributed to the existence of this consultation. We also recognise that end-users of SARs (the other seventy-six agencies) do not feed the benefits back adequately to the NCA. In our view it would be a better use of time and money to invest in explaining better the known value of SARs through research and routine case reviews than to cut them off at source. This would provide empirical evidence of the utility of SARs to both the reporting sector and to senior managers in law enforcement, particularly those without investigative or intelligence backgrounds. This would enhance the legitimacy of the regime among user groups and reinforce their commitment.

Following the publication of our Consultation Paper, we undertook an examination of a number of SARs that had been submitted to the NCA. This was the first independent analysis of its kind in the UK. This small-scale review gave us a valuable insight into the detailed inner workings of the consent regime. As noted above, our principal focus was on authorised disclosures but we were also able to look at a smaller sample of required disclosures for comparison. The results were striking and allowed us to assess the consultation responses against the evidence we collated.

In chapter 2 we outline our methodology and summarise our findings. We examine the data in more detail in each subsequent chapter and use it to inform our recommendations.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Volume of SARs

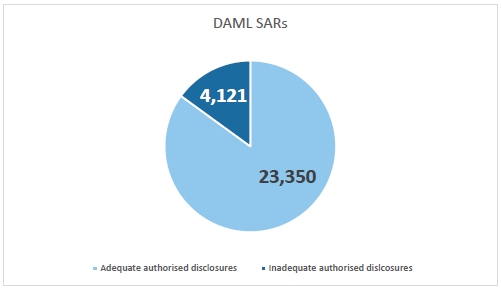

The numbers of SARs submitted to the UKFIU continues to rise. The UKFIU has confirmed that it received and processed 463,938 SARs between April 2017 and

March 2018. This amounts to a 9.6% increase on the volume of SARs in 2016-17. The NCA describe it as a “record number”.38

Of the total number of SARs received, 22,619 were authorised disclosures seeking consent to proceed with a transaction where there was a suspicion of criminal property (now referred to by the UKFIU as a “Defence Against Money Laundering” SAR or “DAML SARs”). This represents a 20% increase on the previous year’s volume of disclosures.39 A further 423 resulted from suspected terrorist financing (“Defence Against Terrorist Financing” or “DATF SARs”). The trend for an increasing volume of disclosures has continued.

Of the total number of authorised disclosures lodged in respect of suspected money laundering, consent was refused in 1,291 cases (5.70%). In relation to authorised disclosures in respect of suspected terrorist financing there were 42 cases in which consent was refused (9.93%). The NCA reported that £51,907,067 was denied to criminals as a result of DAML requests (both refused and granted).

Of the 1,291 authorised disclosures where a suspicion of money laundering was identified and consent was refused initially, 440 (34.08% of overall refusals) were subsequently granted in the moratorium period.

The NCA have told us that since our consultation, the volume of authorised disclosures that they are receiving continues to rise and the regime in its present form is untenable:

Pressures on the DAML (consent) regime have continued, to rise. In February 2019 we received 4,000 DAMLs compared with 2,000 in February 2018, a 100% increase. While the DAML regime produces operational results, clearly this is unsustainable.40

FATF Mutual Evaluation – underreporting and concerns about the quality of SARs

The Financial Action Task Force (“FATF”) conducted its evaluation of the UK’s anti- money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures in 2018, publishing its findings in December. The evaluation offered a broadly positive assessment of existing measures. However, FATF observed that:

… while reports of a high quality are being received, the SAR regime requires a significant overhaul to improve the quality of financial intelligence available to the competent authorities.

FATF also raised concerns about the quality of SARs lodged even by those who are regular reporters:

The requirement to report SARs applies to all financial institutions and DNFBPs41 as required by the FATF. Ordinarily, this should ensure that financial intelligence from

38 National Crime Agency, Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) Annual Report (2018) p 3.

39 Above.

40 Further Comments from the NCA, 29 March 2019.

41 Designated non-financial businesses and professions.

all of the sectors covered by the FATF Recommendations is available, but the low level of reporting in many sectors and the poor quality of many SARs has a negative impact on the quality and usefulness of the financial intelligence available to the competent authorities.42

There is a risk that investigative opportunities, particularly relating to complex criminal activity, may be missed as a result of a lack of comprehensive, cross agency analysis of available financial intelligence and the poor quality of SARs.43

FATF reported that SARs contributed to around 7,900 investigations, 2,000 prosecutions and 1,400 convictions annually for standalone money laundering offences or where money laundering is the principal offence.44

Reflecting the high volume of reporting and the wide variety of sectors and businesses incorporated into the UK’s anti-money laundering/counter terrorist financing regime, there are concerns about the quality of reporting by all reporting entities, including banks. During the on-site visit, some firms indicated that they were sometimes filing SARs in response to unexplained/unusual transactions without additional analysis or investigation. LEAs reported concerns about the quality of the SARs, including that they lacked information on a genuine suspicion of money laundering or terrorist financing.45

STRUCTURE OF REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In this section we summarise the contents of our report and our recommendations.

In chapter 2 we outline the data analysis we conducted in conjunction with the UKFIU. We set out our methodology and some of our overall findings. We use this analysis to inform our recommendations in subsequent chapters. In this chapter we recommend that samples of SARs are analysed at regular intervals in consultation with an Advisory Board constituted by those with relevant expertise.

In chapter 3 we make the case in principle for statutory guidance overseen by an Advisory Board. We set out our arguments for statutory guidance on three statutory concepts: suspicion, reasonable excuse and appropriate consent. We recommend that POCA is amended to impose an obligation on the Secretary of State to issue guidance covering the operation of Part 7 of POCA so far as it relates to businesses in the regulated sector. In particular, we recommend that explanatory guidance should cover the suspicion threshold, appropriate consent and the reasonable excuse defence to assist the regulated sector in complying with their legal obligations. We also recommend that an Advisory Board is created to assist in the production of

42 Financial Action Task Force, Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures: United Kingdom Mutual Evaluation Report (December 2018) p 51.

43 Financial Action Task Force, Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures: United Kingdom Mutual Evaluation Report (December 2018) p 59.

44 Above, p 3.

45 Above, p 121.

guidance, to measure the effectiveness of the reporting regime and to advise the Secretary of State on ways to improve it.