Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

English and Welsh Courts - Miscellaneous

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> English and Welsh Courts - Miscellaneous >> The Rustat Memorial, Jesus College, Cambridge, Re [2022] ECC Ely 2 (23 March 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/Misc/2022/2022ECCEly.html

Cite as: [2022] ECC Ely 2

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral citation number: [2022] ECC Ely 2

Faculty application - Grade I listed Cambridge College Chapel – College applying to remove the C 17th Rustat Memorial from the west wall of the Chapel to a specially created exhibition space within the College – Pastoral and missional concerns due to Rustat’s involvement in the slave trade –DAC not objecting - 68 objectors becoming parties opponent - Removal causing considerable or notable harm to significance of Chapel - College not demonstrating a clear and convincing justification for removal - Faculty refused

Application Ref: 2020-056751

IN THE CONSISTORY COURT OF

THE DIOCESE OF ELY

Date: 23 March 2022

Before:

THE WORSHIPFUL DAVID HODGE QC, DEPUTY CHANCELLOR

In the matter of:

THE RUSTAT MEMORIAL, JESUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

Hearing Dates: 2 - 4 February 2022

Venue: Jesus College, Chapel

Mr Mark Hill QC (instructed by Mr Stuart Jones of Birketts LLP) represented the petitioner, Jesus College, Cambridge

Mr Justin Gau (instructed directly) represented 65 of the parties opponent

Professor Lawrence Goldman, another party opponent, appeared in person

Another two parties opponent were neither present nor represented

The following cases are referred to in the judgment:

Re All Saints, Hooton Pagnell [2017] ECC She 1

Re Jesus College, Cambridge [2022] ECC Ely 1

Re St Alkmund, Duffield [2013] Fam 158

Re St John the Baptist, Penshurst (2015) 17 Ecc LJ 393

Re St Lawrence, Wootton [2015] Fam 27

Re St Luke the Evangelist, Maidstone [1995] Fam 1

Re St Peter, Shipton Bellinger [2016] Fam 193

Re St Peter & St Paul, Aston Rowant [2019] ECC Oxf 3, (2020) 22 Ecc LJ 265

Re St Peter & St Paul, Olney [2021] ECC Oxf 2

Re St Saviour, Nottingham [2022] ECC S & N 1

JUDGMENT

Paragraphs Introduction

Decision and summary reasons

Tobias Rustat and his memorial

The work of the Legacy of Slavery Working Party and the resulting petition

Consultation responses

The Diocesan Advisory Committee

The published guidance on ‘Contested Heritage in Churches and Cathedrals’

The historical evidence

The College’s evidence

The evidence of the parties opponent

The legal framework

The College’s submissions

Mr Gau’s submissions

Professor Goldman’s submissions

Analysis and conclusions

Fees and costs

Postscript

On the morning of the first day of the hearing, we prayed:

Give us, Lord, the courage to change those things

that should be changed,

the patience to bear those things

that cannot be changed,

and the wisdom to know the difference.

(with acknowledgment to Reinhold Niebuhr)

- On 11 October 2021 I was appointed by the Bishop of Huntingdon (pursuant to powers conferred by an instrument of delegation) to determine a faculty petition presented on 17 May 2021, through the Online Faculty System (the OFS), by Dr Richard Anthony, the Bursar of Jesus College, Cambridge. That petition sought a faculty authorising the: “Removal and inspection of and conservation works to the memorial dedicated to Tobias Rustat currently on the west wall of the College Chapel. Safe temporary storage or display of the monument on college premises.” A draft petition seeking a faculty in these terms had previously been submitted to the Diocesan Registry in December 2020, and this had been the subject of extensive consultation. Included amongst the supporting documents on the OFS was a further petition, dated 7 May 2021, in the name of the College of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist and the Glorious Virgin Saint Radegund, near Cambridge, and commonly called ‘Jesus College, Cambridge’ (the College), acting by the College architect, Mr Paul Vonberg (who signed the document). That petition seeks (in summary) a faculty authorising: (1) the careful removal from the west wall of the Grade I listed College Chapel of the memorial to Tobias Rustat, (2) the making good of the wall, using appropriate traditional materials, and (3) the conservation of the memorial, which is to be re-erected in an exhibition and study space to be created in a room on the ground floor of East House, which is situated within the College grounds to the north-east of Library Court. At the outset of the substantive hearing, the College made it clear that it was seeking a faculty in the terms described in the petition dated 7 May 2021, rather than the petition dated 17 May 2022.

- I have conducted two procedural hearings on this petition. These took place remotely, using the Zoom video platform, on Monday 15 November 2021 and Saturday 8 January 2022. At the second of those hearings, I refused an application by the parties opponent for an adjournment of the substantive hearing of this petition for at least four months for the reasons I set out in a written judgment handed down on 18 January 2022 (under neutral citation number [2022] ECC Ely 1) to which reference may be made for additional background details to this petition. I undertook a site visit, accompanied by representatives of the College and the parties opponent, on the afternoon of Sunday 30 January 2022 during the course of which I inspected the whole of the Chapel, the Fellows’ Guest Room (the east wall of which forms the west wall of the Chapel, on which the Rustat memorial is presently displayed), and East House. Later that same evening, I attended Choral Evensong in the College Chapel. The substantive hearing took place, in the nave, the transepts and the tower crossing of the College Chapel, over three days from Wednesday 2 to Friday 4 February 2022. I sat in the tower crossing facing west, with the Rustat memorial directly opposite the bench. Mr Mark Hill QC (instructed by Birketts LLP) appeared for the College. Mr Justin Gau (of counsel, instructed directly) appeared for 65 of the parties opponent. Professor Lawrence Goldman, another of the parties opponent, appeared in person; whilst the remaining two parties opponent were neither present nor represented. Since there was insufficient space in the Chapel to accommodate all those, including representatives of media organisations, who wished to attend the hearing, the proceedings were “live-streamed” to a “viewing room” within the College premises. I am grateful to all those many members of the College staff who were concerned in facilitating this hearing, at a time when some COVID-related restrictions remained in place, for the welcome and the hospitality that were shown to all those who attended and were involved in the hearing, and for ensuring a safe working environment for all of us. I am also grateful to all the many people who have taken the time and the trouble to write in to the Diocesan Registry with their views, some in support of, and others in opposition to, the petition without wishing to become formal parties to these faculty proceedings. I have taken all of the views expressed into account in reaching my decision on the petition, weighing the arguments, rather than counting the numbers, on each side. I must also pay tribute to the Diocesan Registry and its staff who have had to address a faculty petition of a magnitude, nature, and complexity well outside the normal range of applications submitted through the OFS. They have done so with competence and good humour. At the conclusion of the hearing, probably to the surprise of no-one present, I indicated that I would hand down my judgment in writing. I apologise for the length of time it has taken me to prepare this judgment but, although I have taken some two weeks’ leave to do so, I have had to interrupt work on it to attend to other cases in the Business and Property Courts in which I sit.

- The College’s petition is advanced on the basis that any harm caused to the significance of the Chapel as a building of special architectural and historic interest by the removal of the Rustat memorial is substantially outweighed by the resulting public benefits, in terms of pastoral well-being and opportunities for mission. The College contends that because of Rustat’s known involvement in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans (usually referred to as the slave trade) throughout the period from 1663 until shortly before his death on 15 March 1694 [1], the continued presence of his memorial in such a prominent position, high up on the west wall of the Chapel, creates a serious obstacle to the Chapel’s ability to provide a credible Christian ministry and witness to the College community and a safe space for secular College functions and events; and that its removal will enable the pastoral, and missional, life of the Chapel to thrive. The College says that it does not seek to erase Rustat’s name, or his memory, from the College but merely to re-locate his memorial to a more appropriate, secular space, where it can be properly conserved and protected, and become the subject of appropriate educational study and research.

- The parties opponent contend that the court should give the support afforded to the petition from current and past students of the College no weight at all since it is the product of a false narrative that Rustat amassed much of his wealth from the slave trade, and used moneys from that source to benefit the College; and that any positive support from the amenity bodies for the removal of the memorial is similarly tainted by reactions to the memorial generated entirely by misinformation. The parties opponent acknowledge that Rustat’s whole life must be examined and put into its true context; but they say that this can be done most economically, most effectively, and most powerfully, by leaving the memorial in place, with an appropriate contextual plaque and information.

- Those coming to this petition with no knowledge of planning and ecclesiastical law may wonder why the College itself cannot simply implement the decision its governing body has already made, and remove the memorial to a safe, secular space elsewhere within the College itself. The answer is that the Chapel is a Grade I listed building, which means that the Chapel is of exceptional interest in a national context. That listing extends to any object or structure fixed to the building, and that includes the Rustat memorial. If the Rustat memorial were within a secular space, its removal would require listed building consent from the local authority or the Secretary of State. Because the Chapel is included in the list of places of worship maintained by the Church Buildings Council under s. 38 of the Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction and Care of Churches Measure 2018 (the 2018 Measure), it is subject to the faculty jurisdiction of the diocese of Ely, exercised through its consistory court. It therefore benefits from the ‘ecclesiastical exemption’ from the need for listed building consent. This means that a faculty (or permission) from the consistory court of the diocese takes the place of listed building consent. But it is important to understand that it does so only because the state regards the faculty jurisdiction as equivalent to secular listed building consent, in terms of due process, rigour, consultation, openness, transparency and accountability; although this does not mean that the consistory court is required to apply precisely the same approach to listed buildings as is followed in the secular system. This is because a church (or a college chapel) is a house of God and a place for worship: it does not belong to conservationists, to the state, or to the congregation, but rather to God. The ecclesiastical exemption is of importance to the Church as it permits it to retain control of any proposed alterations to a listed church building that may affect its worship, mission or liturgy. As Chancellor Singleton QC (in the Diocese of Sheffield) explained at paragraph 20 of her judgment in Re All Saints, Hooton Pagnell [2017] ECC She 1:

- After that brief introduction to this case, I turn to the merits of the petition. My detailed reasons will follow later in this judgment; and I would urge anyone interested in the fate of the Rustat memorial, and the life of the College and its chapel, to read them in full. But since I do not wish to create any unnecessary suspense, I will start by saying that this petition is dismissed for the following brief reasons: Applying the Duffield guidelines, I am satisfied that the removal of the Rustat memorial from the west wall of the Chapel would cause considerable, or notable, harm to the significance of the Chapel as a building of special architectural or historic interest. The College must therefore demonstrate a clear and convincing justification for the removal of the memorial. I am not satisfied the College has done so: the suggested justification is clearly expressed, but I do not find it to be convincing. I am not satisfied that the removal of the memorial is necessary to enable the Chapel to play its proper role in providing a credible Christian ministry and witness to the College community, or for it to act as a focus for secular activities and events in the wider life of the College. I am not satisfied that the relocation of the memorial to an exhibition space where it can be contextualised is the only, or, indeed, the most appropriate, means of addressing the difficulties which the presence of the Rustat memorial in the College Chapel is said to present.

- No-one disputes that slavery and the slave trade are now universally recognised to be evil, utterly abhorrent, and repugnant to all right-thinking people, wherever they live and whatever their ethnic origin and ancestry. They are entirely contrary to the doctrines, teaching and practices of the modern Church. However, on the evidence, I am satisfied that the parties opponent have demonstrated that the widespread opposition to the continued presence of the Rustat memorial within the College Chapel is indeed the product of the false narrative that Rustat had amassed much of his wealth from the slave trade, and that it was moneys from this source that he used to benefit the College. The true position, as set out in the historians’ expert reports and their joint statement, is that Rustat’s investments in the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa (the Royal Adventurers) brought him no financial returns at all; that Rustat only realised his investments in the Royal African Company in May 1691, some 20 years after he had made his gifts to the College, and some five years after the completion of the Rustat memorial and its inscription; and that any moneys Rustat did realise as a result of his involvement in the slave trade comprised only a small part of his great wealth, and they made no contribution to his gifts to the College. I recognise that for some people it is Rustat’s willingness to invest in slave trading companies at all, and to participate in their direction, rather than the amount of money that he made from that odious trade, that makes the Rustat memorial such a problem. I recognise also that it does not excuse Rustat’s involvement in the slave trade, although it may help to explain it, that, in the words of L. P. Hartley (in his 1953 novel, The Go-Between), “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” I also acknowledge that there is no evidence that Rustat ever repented for his involvement in the slave trade, unlike, for example, the reformed slave ship captain, the Reverend John Newton, whose hymn ‘How Sweet the name of Jesus Sounds’ was sung at the beginning of the service of Choral Evensong which I attended at the College Chapel and whose history I had to consider in the context of the creation of an educational area dedicated to his life and work in my judgment in Re St Peter & St Paul, Olney [2021] ECC Oxf 2. However, I would hope that, when Rustat’s life and career is fully, and properly, understood, and viewed as a whole, his memorial will cease to be seen as a monument to a slave trader. Certainly, I do not consider that the removal of such a significant piece of contested heritage, representing a significant period in the historical development of the Chapel from its medieval beginnings to its Victorian re-ordering, has been sufficiently clearly justified on the basis of considerations of pastoral well-being and opportunities for mission in circumstances where these have been founded upon a mistaken understanding of the true facts.

- I am also persuaded that the appropriate response to Rustat’s undoubted involvement in the abomination that was the enslavement and trade in black Africans is not to remove his memorial from the College Chapel to a physical space to which its monumentality is ill-suited, and where that involvement may conveniently be forgotten by many of those who attend the College Chapel, whether for worship or prayer, or for secular purposes, but to retain the memorial in the religious space for which it was always intended, and in which Rustat’s body was laid to rest (on 23 March 1694) and his human remains still lie, where, by appropriate interpretation and explanation, that involvement can be acknowledged and viewed in the context of his own time and his other undoubted qualities of duty and loyalty to his King, and his considerable charity and philanthropy. In this way, the Rustat memorial may be employed as an appropriate vehicle to consider the imperfection of human beings and to recognise that none of us is free from all sin; and to question our own lives, as well as Rustat’s, asking whether, by (for example) buying certain clothes or other consumer goods, or eating certain foods, or investing in the companies that produce them, we are ourselves contributing to, or supporting, conditions akin to modern slavery, or to the degradation and impoverishment of our planet. I acknowledge that this may take time, and that it may not prove easy; but it is a task that should be undertaken.

- I bear in mind also that whilst any church building must be a ‘safe space’, in the sense of a place where one should be free from any risk of harm of whatever kind, that does not mean that it should be a place where one should always feel comfortable, or unchallenged by difficult, or painful, images, ideas or emotions, otherwise one would have to do away with the painful image of Christ on the cross, or images of the martyrdom of saints. A church building is a place where God (not the people remembered on its walls) is worshipped and venerated, and where we recall and confess our sins, and pray for forgiveness. Whenever a Christian enters a church to pray, they will invariably utter the words our Lord taught us, which include asking forgiveness for our trespasses (or sins), “as we forgive them that trespass against us”. Such forgiveness encompasses the whole of humankind, past and present, for we are all sinners; and it extends even to slave traders. Jesus recognised that it would not be easy to be one of his followers; yet he led by his example. The first words Jesus uttered from the Cross, as he suffered in terrible agony caused by others, were not words of anger or vengeance; incredibly, he thought of others: the very people who were hurting him, and he begged God to pardon them: “Then said Jesus, ‘Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do’. And they parted his raiment, and cast lots.” (Luke 24, v. 34).

- The entry for Tobias Rustat (bap. 1608, d. 1694) in The Dictionary of National Biography (created by Philip Lewin on 9 December 2021) describes him as a “courtier and benefactor”. It notes that: “Two years into the Restoration he was lending money to other courtiers, using the king's authority to ensure priority repayment. As Rustat’s wealth increased he invested in the slave trade. His name appears on both the 1663 charter of the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, and the later 1672 charter of the reconstituted Royal African Company, where he served on the board as a director (‘assistant’) in the years 1676 and 1679–80. He also appears to have had an interest in the Gambian Adventurers. The record of his banking transactions with Edward Backwell still survives. … Rustat commissioned three royal statues from Grinling Gibbons, all in Roman costume — Charles II, at Chelsea; Charles II on a horse, in Windsor Castle; and James II, now in Trafalgar Square. In Jesus College, where Rustat is buried, is a marble memorial, probably by Gibbons, which Rustat stored in his house for eight years. In 2020 the college decided to replace this memorial with a plaque acknowledging Rustat’s involvement in the slave trade. The college also has a portrait painted by [Sir Godfrey] Kneller, dated 1682. In the British Museum is a rare engraving, apparently based on this portrait, but incorporating a charity motif.” The previous version of this entry (also created by Philip Lewin on 3 January 2008) noted that: “Two years into the Restoration he was lending money to other courtiers, using the King's authority to ensure priority repayment. He became a director of the Royal African Company and the record of his banking transactions with Edward Backwell still survives.”

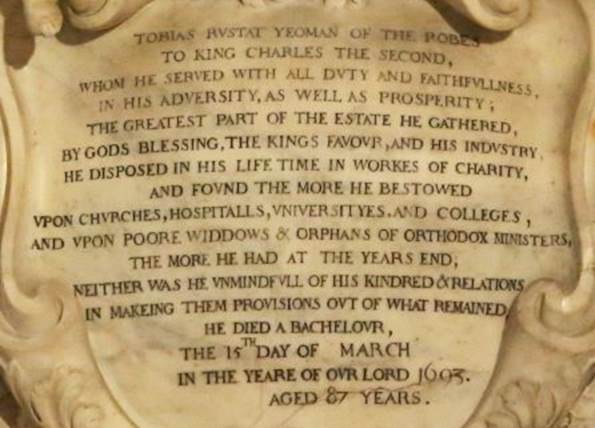

- The entry for the College Chapel in the current (2014) volume of The Buildings of England for Cambridgeshire (edited by Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner) describes the Rustat Memorial (at page 117) as follows: “w wall, Tobias Rustat + 1693/4, an excellent monument with the courtier’s portrait in an oval medallion, two asymmetrically posed putti holding up draperies, and garlands below the inscription. Made c. 1686, almost certainly by the studio of Grinling Gibbons, from whom Rustat commissioned royal statues for Windsor and elsewhere; probably carved by A. Quellin.” A fuller description of the memorial reads: “… white marble wall monument with inscription cartouche bordered by garlands of fruit and flowers and surmounted by two cherubs holding aside draperies to reveal an oval medallion containing a portrait-bust carved in high relief, and with a crowning cartouche containing the carved arms of Rustat”. Rustat commissioned the memorial in about 1686 and, for the last eight years of his life, it resided at his house in Chelsea. Apart from the final lines, with details of Rustat’s death (according to the old calendar), he was responsible for the inscription, which reads:

- At the end of this judgment, I attach photographic images showing Sir Godfrey Kneller’s 1682 portrait of Rustat, the Rustat memorial on the west wall of the College Chapel, its inscription, the Cranmer monument (of 1912) on the south wall of the south transept, and views of the Chapel; and also an artist’s impression of the proposed exhibition space within East House (which Pevsner describes as “wholly dull”), to the north-east of Library Court.

- At its Council Meeting on 20 May 2019 the College decided to establish a College-based Working Party to undertake an inquiry into legacies of slavery at the College. Its terms of reference included exploring how the College might have benefited historically from slavery and coerced labour through financial and other donations and bequests. I emphasise that the decision to establish the LSWP had been taken before Ms Sonita Alleyne was admitted as the 41st Master of the College, on 7 October 2019. The LSWP’s Interim Report (presented to the College Council in November 2019) considered the “strong and well-documented” links to slavery of the College’s “most prominent benefactor”, Tobias Rustat, whose gifts to the College were said to total £3,230 (the equivalent of £500,000). The Interim Report stated:

- This draft petition provoked a host of objections. Although over 120 objectors chose not to do so, in due course some 68 of those who had objected to the draft petition became parties opponent to the eventual petition; and 65 of them have instructed Mr Gau to represent their interests. Mr Gau had previously settled and submitted a formal written objection to the draft petition. Objections have also been received from five lineal descendants of Tobias Rustat’s elder brother, Robert, whose son (and Tobias’s nephew), also called Robert, and his family are said to have been the principal beneficiaries of Tobias Rustat’s estate. The Registry have also received a number of emails from students of the College strongly supporting the removal of the Rustat memorial from the Chapel and its relocation in an educational space within the College. In July 2021 189 College alumni sent an open letter to the Master, which was copied to the Registry, also expressing their full support for the College’s efforts to remove the memorial from the Chapel and relocate it to a place where it could be understood in its full context. It is clear from these documents that feelings about the future of the Rustat memorial run high on both sides of this dispute. It is a powerful tribute to their maturity and integrity that throughout the hearing of this petition everyone concerned has displayed a remarkable degree of dignified restraint and mutual tolerance and respect, appropriate to the College’s standing as one of this nation’s foremost academic institutions for the advancement of education, learning, research, and religion (as provided in the College’s charitable objects and governing statutes). Typical of this dignified restraint was the fact that on the mornings of the second and third days of the hearing, my arrival in the College was welcomed by about a dozen members of the “College Chapel Community” politely displaying hand-written, home-made placards reminding me that “Churches are people not marble” and that this case is about “Moving not erasing”. I have had regard to all the written representations received by the Registry, irrespective of whether or not the makers of those representations have elected to become a party to these proceedings.

- Historic England, the Church Buildings Council (the CBC), the local planning authority and interested amenity societies have all been consulted on the removal proposals as they have developed with the following results:

- Historic England’s initial advice was contained in a 12-page letter, dated 18 December 2020, from Mr John Neale, the head of development advice. This had been informed both by a visit to the College to view the monument in its setting and by reference to the Historic England Advisory Committee. It is impossible to due full justice to this letter without reproducing it in full, and it merits careful and considered reading. The summary on page 1 reads:

- Historic England’s letter proceeds to consider Sir Tobias Rustat, his wealth and its connection to Jesus College noting that: “Rustat … profited knowingly from the enslavement of people. As the College states in its application, ‘profiting from enslavement, trafficking, and exploitation is unambiguously wrong’.” It then describes the memorial, its significance and its relation to that of the Chapel:

- In a later letter, dated 14 July 2021, sent in response to the petition, Historic England reiterated its previous advice save in one respect. It acknowledged that the principal difference between the final petition and the earlier version of the proposals was that it is now proposed to create a new space within East House in which Rustat’s monument would be displayed, fixed to a wall, as part of an exhibition of material from the College’s archive, which is housed in this building. Historic England

- In their original email, dated 11 December 2020, the Ancient Monuments Society (the AMS) indicated its opposition to taking the memorial down without the clearest idea where it was to end up. The AMS was clear that any new home should be appropriate in terms of presentation, associated interpretation, and environmental conditions. They emphasised that “… we are surely dealing here with a work of art which, judged by intrinsic merits, is itself of Grade 1 quality and interest”. In a later email, dated 25 June 2021, written in response to the revised proposal to re-locate the memorial to East House, the AMS declared this to be

- In its initial letter of advice, dated 14 December 2020, SPAB emphasised that it had no wish to commemorate slavery or anyone who had benefitted from it and it recognised that there was a long tradition of removing monuments when societies changed.

- The Georgian Group’s consultation response is set out in an email dated 19 August 2021. Noting that the memorial falls outside its normal 1700-1840 date remit, it nevertheless commented as follows:

- The consultation response of the conservation team of the local planning authority is directed solely to the practical, historic building conservation aspects of the proposal to re-locate the memorial from the wall of the College Chapel to some alternative location.

- The CBC set out their position in a letter dated 9 July 2021. They did not wish to enter a formal opposition to the proposal, or to become a ‘party opponent’; but they advised that there were still a number of areas of the application that required further consideration. The CBC commented in particular as follows:

- On 30 December 2020 the CMS wrote expressing its total opposition to the proposed removal of the Rustat memorial from the west wall of the College Chapel, describing it as “totally unacceptable”:

- On 29 January 2021 the DAC issued a Notification of Advice (NoA) stating that it did not object to the court approving the temporary relocation of the Rustat memorial within the College, subject to the following provisos:

- The NoA records that in the DAC’s opinion, the work proposed is likely to affect the character of the Chapel as a building of special architectural or historic interest. It notes that Historic England, the local planning authority, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, the Ancient Monuments Society, and the Church Buildings Council had all been consulted about the proposals; and that all the responding consultees had raised objections which had not been withdrawn. The Committee's principal reasons for not objecting to the proposals being approved, despite those objections, were as follows:

- On 24 June the Diocesan Registrar wrote to the DAC, referring to further submissions made by the College and seeking the DAC’s views on these. On 21 July 2021 members of the DAC’s casework group visited the College to inspect the memorial in the Chapel, and also the proposed new location for the monument in East House. The views of the casework group were detailed in a site visit report; and the advice contained within that report was endorsed by the full DAC at their meeting on 29 July 2021. This can be summarised as follows:

- In May 2021 the Church Buildings Council and the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England (the CFC) published helpful guidance entitled ‘Contested Heritage in Churches and Cathedrals’. This guidance was issued pursuant to powers under s. 3 (3) (a) of the Care of Cathedrals Measure 2011, and s. 55 (1) (d) of the Dioceses, Mission and Pastoral Measure 2007. As this is statutory guidance, it must be considered with great care (as I have sought to do); and the standards of good practice set out in the guidance should not be departed from unless the departure is justified by reasons that are spelled out clearly, logically and convincingly. In his closing submissions, Mr Hill notes that this guidance contains a framework for addressing contested heritage but it is no substitute for the Faculty Jurisdiction procedure. I will set out those parts of the guidance to which I was specifically referred, or which seem to me to be of particular relevance to this present faculty application (italicising those statements upon which Mr Hill places particular emphasis and underlining four passages which seem to me to be of particular relevance to the present case):

- Pursuant to my case management order of 15 November 2021 (as varied with the consent of the parties on 8 December 2021), on 6 December 2021 the College served the witness statement of Dr Michael Edwards, a senior lecturer in History and a Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge. He was proffered as the College’s only expert witness, speaking to research he had undertaken into original source material relating to the life and activities of Tobias Rustat. Although I acknowledge that Dr Edwards is suitably qualified to give such evidence, I note that in its interim (November 2019) report, Dr Edwards was noted as “in attendance” at LSWP meetings as the Keeper of the Old Library; and in this role he is recorded as one of those who had made “key contributions”. He is also recorded as a member of the LSWP in its November 2020 report. At paragraph 19 of his statement, Mr Edwards states:

- The service of Dr Edwards’s witness statement provoked the application by the parties opponent which led to my judgment of 18 January 2022, refusing them an adjournment of the substantive hearing of this petition (since I considered that this would have been contrary to the overriding objective of dealing with the case justly and, in particular, expeditiously) but giving them permission to call their own historical expert, Dr Aaron Graham, a lecturer in early modern British economic history at University College, London, to respond to the statement of Dr Edwards. Dr Graham’s particular field of study is the economic, social and political history of Britain and its empire between 1660 and 1850. In the event, Dr Graham was able to produce his expert statement on 18 January 2022.

- Dr Edwards and Dr Graham were able to meet remotely via Zoom on the afternoon of Friday 21 January 2022 for around one and a half hours to discuss their respective research findings and expert reports on Tobias Rustat’s involvement with the slave trade. The object of that meeting was to identify areas of agreement and any remaining areas of disagreement. There was a high level of agreement on the facts of Rustat’s involvement with companies that had traded in enslaved people. In his expert report, Dr Graham had detailed several areas where, based on their reports, it seemed that the experts held different views. These were: corporate governance in the late 17th century; the exact nature of Rustat’s participation in both the Royal Adventurers and the Royal African Company; the activities of the Gambia Adventurers; wider attitudes towards slavery in late 17th century Britain; and the significance of Rustat’s involvement with the financier, Edward Backwell. The experts discussed each of the areas of potential disagreement and, in most cases, they identified areas of common ground. These are listed in section 1 of their joint statement. Remaining areas of disagreement were listed in section 2. For ease of reference, and to avoid extending the body of this judgment more than is strictly necessary, I have set out relevant extracts from the expert historians’ joint statement at the end of this judgment, together with extracts from Dr Edwards’s witness statement where this is now agreed and is necessary to an understanding of the joint statement.

- The College wish to emphasis that: (1) Rustat: (a) was involved, as an investor, a lender, and a member of the Court of Assistants, with two companies (the Royal Adventurers and the Royal African Company) that had traded in enslaved people; and (b) was fully aware that these companies were involved in trading enslaved people; (2) this involvement both pre-dated and post-dated Rustat’s gifts to Jesus College, and he was involved in the Royal Adventurers at the time he donated to the College; and (3) Rustat appears to have been more active than the average shareholder in the governance of the Royal African Company (although this cannot be stated definitively without a quantitative study comparing his level of participation against other shareholders).

- However, it is also clear that Rustat: (1) amassed little of his great wealth from the slave trade and (2) used no moneys from that source to benefit the College. By about the time of his gifts to the College, far from generating any financial returns, his involvement in the Royal Adventurers had probably cost him £1,044, equivalent to some £172,980 today; and this loss must be set against the equivalent net profit figure of between £923 13s 10d and £1,595 13s 10d (equivalent to between £137,300 and £237,200 today) which he and his estate together earned from the Royal African Company. Dr Edwards does not believe that “the key issue here is arguing about whether Rustat made a ‘big’ profit or not; the moral question of his involvement in slavery should not be reduced to the question of whether he made more or less money from it than other investors”. Dr Edwards acknowledges that “Rustat died a wealthy man, and there is no dispute that any money he received as a result of involvement in the slave trade comprised only a part of his estate, and that it did not exceed the reported value of his philanthropic giving”. But he makes the point that “a small part of a wealthy person’s estate might still be a very considerable sum of money”. Dr Edwards also emphasizes that “any investment in the slave trade supported the exercise of that trade”, whilst recognizing that: “It is important to remember that membership in early modern joint stock companies had other social, political, and economic benefits that appealed to their members. Access to economic opportunities beyond those offered by the African companies may have been another factor that attracted Rustat, particularly given his money-lending and philanthropic activities.” Dr Graham considers that Rustat’s conduct “is consistent with that of someone seeking to manage and increase the value of his investment but is also not incompatible with someone who chose to seek profit in a fashion which also demonstrated his loyalty to the Stuart cause; indeed, he may not have seen these as being contradictory”.

- The College called six witnesses in the following order:

- At paragraphs 4 and 5, the Dean expresses his

- At paragraphs 6 and 7, the Dean explains the memorial’s incongruence with the Christian gospel:

- At paragraphs 8 to 15, the Dean explains how the continued presence of the Rustat memorial in the College Chapel frustrates the Chapel’s credible Christian witness and ministry to all, including:

- At paragraphs 16 to 19 the Dean considers how the memorial hinders the Chapel’s outreach, mission and welcome within and to the College community, including:

- At paragraphs 20 to 27, the Dean addresses the competing merits of relocation and contextualisation, as follows:

- At paragraphs 28 to 30 the Dean explains that he was aware, at an early stage of the College’s discussions with the DAC, that the Rustat memorial would usually be considered as the property of the heirs-at-law of those who first erected it, and that at some point within the proceedings the College would be expected to attempt to identify such a person, whose views might therefore offer some pertinence as to the future of the memorial. The Dean makes it clear that the College does not wish to challenge the claim of Mr Stephen Hemsted and other family members that they are descendants of Robert Rustat, but the College is in no position to confirm whether they are the heirs-at-law to Tobias Rustat, as they claim. The Dean notes that Stephen Hemsted only claims that he and his brothers are heirs ‘along with others’, not that he (or any of his brothers in particular) is the sole heir-at-law. The College has sought advice from a professional genealogist with a view to identifying the heir-at-law to Tobias Rustat’s estate but they have been advised that, given the number of succeeding generations, the number of Rustat’s indirect descendants, and the possibility that the research may include countries outside the United Kingdom, such a commission could involve up to 200 hours of work, at a cost of up to £14,000. The College did not consider such a cost to be an appropriate use of its charitable funds.

- Because he was the College’s first witness, the Dean was subjected to a lengthier cross-examination than any of the College’s other witnesses. Effectively, he was being used as a vehicle to advance the case of the parties opponent by reference to certain of the documents in the hearing bundle. The Dean was taken to an extract from a minute of the discussions at the College Council on 13 July 2020 (at which he told the court that he had not been present) where he was recorded as supporting, as an alternative to the removal of the memorial, “leaving the memorial in place with the addition of contemporary artwork to recontextualise it”. The Dean explained that this had been one of a number of suggestions that had been proposed as a response to the concerns that had been raised about the presence of the memorial. Relocation became the preferred option. The Dean affirmed that relocation would bring pastoral and missional benefits, but it would also assist in contextualising the memorial. Some undergraduates were disturbed and upset by being faced with the memorial, and it represented a barrier to welcoming them into, and their participation in the life of, the Chapel. Mr Gau pointed to the statements in the LSWP’s November 2019 interim report (which the Dean confirmed had been made available to the student body) that:

- In his introduction to the faculty application in May 2021, the Dean had written:

- In the course of his cross-examination of the Dean, Professor Goldman emphasised Rustat’s other fine qualities (of duty, faithfulness, fidelity and loyalty to his King), which could not be entirely discounted because of one facet of his whole life (his investment in two royal companies engaged in the slave trade). The Dean acknowledged this, but he maintained that these qualities could be more appropriately studied and engaged with elsewhere than in the Chapel. The problem was not so much about Rustat himself but about the effect of the memorial on the Chapel’s worship and mission, and the flourishing of the pastoral life of the Chapel.

- In his written evidence Professor Goldman had raised the issue of the Cranmer memorial on the south wall of the south transept of the Chapel, posing the question: ‘If Rustat, why not Cranmer?’ Thomas Cranmer had been Archbishop of Canterbury for twenty years, from 1533 to 1553, and he had been responsible for the production of the Book of Common Prayer and the 42 (later reduced to the 39) Articles of Religion, the foundational creed of the Church of England. But, according to Professor Goldman, he had also been a murderous misogynist who had shown violent hostility to religious freedom and all those who had rebelled against the English Reformation or had held to the old Roman Catholic religions and its ways. In 1533 Cranmer had pronounced Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn to be lawful; three years later he pronounced it null and void. He took Anne’s confession before her execution in May 1536, knowing full well that she was innocent of the crimes laid against her. Cranmer’s biographer describes these events as ‘a stain on Cranmer’s reputation’ whose integrity was ‘soiled’ by his conduct. In short, Professor Goldman contends that it would be easy indeed to build an unanswerable case against Thomas Cranmer and to campaign for the removal of his memorial from the Chapel. Why, he asked, were the fellows of Jesus College not doing so? Why tolerate such behaviour, which runs counter to all modern principles and practice? Is a man who invested indirectly in the slave trade worse than a man who sent soldiers to kill communities that wanted freedom to worship as they wished, and who was instrumental in the execution of three defenceless and essentially innocent young women? If the answer to these questions was that we must recognise that political and religious beliefs, and attitudes to women, were different in the 16th century, then the same argument should apply to Tobias Rustat: in his case, he was engaged in perfectly legal investment in a perfectly legal trade (even though it is abhorrent to us today). Religious persecution, murderous misogyny, and profiting from slavery are all wrong. In short, if Rustat, why not also Cranmer? Professor Goldman makes it clear that that he would never support such a campaign. Cranmer was a great figure in his own right, one of those few about whom it might rightly be said that they formed English identity. He is the most distinguished son of the College. He is correctly placed in the College Chapel where he should remain. But it is a truism, which Professor Goldman claims is apparently lost on the fellows of Jesus College, that all great men and women have feet of clay, and that with political and religious leadership comes error, misjudgement and worse. Rustat, and Cranmer, were both servants of monarchs who expected loyalty; their sins derived from that loyalty. So Professor Goldman asks again: If Rustat, why not Cranmer? Professor Goldman put these points to the Dean, who acknowledged that there were clearly elements of Cranmer’s life which he found “regrettable”. The Dean’s response was that not all memorials were the same. Rustat’s memorial was causing practicable and demonstrable difficulties over worship in the Chapel, which was not the case with Cranmer. These had arisen from a particular inquiry into the legacy of slavery. There had been no corresponding inquiry into the Protestant Reformation. The Dean pointed out that the Cranmer memorial was very different in its size and location, and that it merely bore Cranmer’s surname.

- In re-examination, the Dean reiterated that there were no other practicable locations for the memorial within the Chapel. In answer to Mr Hill’s question: How do the spiritual life and worship of the Chapel continue to be compromised by the presence of the memorial? the Dean responded: “There are a variety of responses. There are some members of the College who will not enter the Chapel for any reason and find it distressing. There are a larger majority who continue to come but feel disquieted and discomforted by the memorial. They are in limbo at present, working patiently with the College. They look forward to a conclusion.” I inquired: “Knowing that the College has done all it can to secure the removal of the memorial, there are two options: If the memorial stays, do you consider more people will be lost to the congregation? Do you consider that the congregation will increase if it goes and that those who are disquieted will return?” The Dean’s response was: “I believe that if the memorial stays, those who continue to use the Chapel on the understanding that the College are pursuing removal would stop, and that it would cause untold damage to the reputation and esteem of the College for non-religious functions. If the memorial were to be relocated, I would anticipate that those who are staying away now would feel able to come back. It would help to bolster and secure the sense of welcome the Chapel is renowned for and which, over the last few years, the presence of the memorial has put in jeopardy.” Mr Gau was permitted to ask any questions arising from this answer, which led to this exchange between himself and the Dean:

- In his closing submissions, Mr Gau acknowledged that the Dean had been doing his best to assist the court; but he also criticised him for his reluctance, at times, to accept the obvious, and for his refusal to be moved from his own views. Mr Gau submitted that the Dean’s “judiciously crafted answers” about the emails sent by students, along the lines of: “I wouldn’t have phrased it that way”, had not helped the College’s case. The Dean’s suggestion that more people might come into the Chapel if the monument were removed was mere speculation. The Dean had quoted extensively from College students. Rightly he had not identified them; but nor had he identified when, in what context, or precisely what had been said to him. This evidence was not only hearsay but hearsay with no foundation to assist the court. No witnesses had been called to support the Dean’s assertions. I consider that there is some force in these observations.

- I have no doubt that the Dean’s views are sincerely held and that they are motivated by a genuine concern to preserve, and promote, the position and role of the Chapel as a centre of worship and mission, and as a primary pastoral resource within the College. However, I do not consider that the Dean’s evidence, however moving and caring it was, is sufficient to exclude contextualisation as an appropriate solution to the difficulties presented by the presence of the memorial within the Chapel. I am concerned that the views expressed by members of the student body have been influenced by the false narrative that has gained currency about the source of Rustat’s great wealth, and his donations to the College, and as to the nature and extent of his involvement in the slave trade. I am also concerned that the College has done little to dispel this false narrative, which does disservice to Rustat’s many other fine qualities. I am also concerned by the implications of Professor Goldman’s question: If Rustat, why not also Cranmer? It seemed to me that the Dean provided no satisfactory answer to that question, or any solution to the implications to which it gives rise.

- Mr Doku emphasised that, in terms of numbers, the supporters of the petition listed in the alumni letter outnumber the parties opponent by more than two to one. There is said to be a clear and articulate majority amongst former alumni in favour of the proposal to remove the memorial from the chapel. The signatories make it clear that, far from erasing history, this action is about facing up to the College’s colonial past and taking the necessary action to put that history into context. Mr Doku also introduces a personal note:

- At the end of Mr Doku’s cross-examination, I referred him to paragraph 7 of his witness statement and the following exchange took place between us:

- The Rt Revd Stephen Conway has been the Bishop of Ely since 2010, and he was appointed also as the Acting Bishop of Lincoln with effect from 1 January 2022. His legitimate interest in the life of Jesus College is as the ex-officio Visitor. The Bishop explains that he had been aware during all his time as Bishop and Visitor that there have been scholarships and grants endowed by Rustat and named after him. He regrets to say that he had not investigated Rustat’s life and activity as perhaps he should have done. He had only been aware of the burial of Rustat’s remains in the choir and the presence of an elaborate and “self-vaunting” memorial. The Bishop is glad that the memorial is to be preserved, displayed and fairly interpreted elsewhere in the College. There is no suggestion that Tobias Rustat’s remains should be disturbed, nor the engraved stone immediately above the place of his interment removed. “His place in eternity is not our business and we are all in need of God’s grace and mercy according to the Christian understanding of sin.” The Bishop’s witness statement continues:

- Under cross-examination in his own court, the Bishop made it clear that he had had no direct contact with any of the College students and that he had been reliant upon what he had been told by the Master and the Dean of the College, whom he had reason to trust. The Bishop spoke movingly about how, as an investor in the Royal African Company, Rustat was someone who had allowed human beings to be treated as chattels. People did not need to be reminded, in such a holy place, about how their forebears had been tortured and dehumanised. Rustat’s presence was very obvious in the memorial, as Rustat had intended. The Bishop was concerned for the spiritual life and the mission of the College Chapel, and he would not want anything to detract from Christ’s promise to all humankind. Founding upon evidence provided by Professor Goldman, Mr Gau referred the Bishop to the site of the former shrine of Little St Hugh in Lincoln Cathedral as an example of “retain and explain”. The boy’s murder, in the mid-13th century, had been falsely attributed to members of the local Jewish community; and his shrine had become the focus for antisemitic attacks. In the 1950s the Cathedral had put up an appropriate explanatory notice which (as photographed by Professor Goldman in 2009) stated:

- Dr Mottier’s specialist field of study relates to the comparative history and politics of eugenics and racial ‘science’; and policymaking regarding gender, ethnicity and reparative justice. As the chair of the LSWP since its foundation in May 2019, Dr Mottier’s witness statement seeks “to explain how the Rustat memorial fits within the brief and wider work carried out by the LSWP since July 2019, and to explain the College’s decision-making process regarding the Rustat Memorial and the role of the LSWP within that process”. At paragraphs 13-15 of her witness statement Dr Mottier responds to the statement made by Mr Andrew Sutton, one of the parties opponent, on 7 July 2021 concerning Tobias Rustat as follows:

- At paragraph 26 of her witness statement, Dr Mottier explains that:

- In closing, Mr Gau accused Dr Mottier of not being frank with the court on several occasions, and on one occasion of not being truthful with the court. He also criticised her refusal to accept any view other than her own. In that, she was said to have exemplified the approach of the LSWP as a whole. She was said to have failed to assist the court. I consider that there is some justification in these observations. Certainly, I found Dr Mottier to be an underwhelming witness who was firmly wedded to her own entrenched opinions and unwilling to recognise any views other than her own (unlike the College’s previous witnesses).

- The Master gave evidence from about 3.30 until about 5.10 on the afternoon of the first day of the hearing. Like all the other witnesses, she did so facing away from the Rustat memorial. In his written closing, Mr Gau rightly described the Master as a “deeply impressive person”, although he did add the barbed comment that it was “hard to get a concise answer from her”. It is difficult to do justice to the Master’s eloquent and highly emotive testimony without quoting at length from her witness statement:

- Under cross-examination by Mr Gau, the Master emphasised that the Chapel is a place of education as well as religion; it is also used for music and drama. Rustat’s memorial is in a place of veneration: one has to look up at it. The inscription refers to his “industry”. The memorial is in a difficult space. For a number of people coming into the Chapel, it is very problematic. Speaking as the first black Master of a Cambridge College, the Master described the memorial as putting barriers up to people coming in to the Chapel. The College does not set out to make matters difficult for people; the College wants to be more inclusive. The Master explained that every community in the Church of England is different and must decide what is right for it. The College has concluded that even a large contextual plaque would not be adequate. One out of every three people applying to come to the College is of mixed colour. You cannot say to people whose ancestors were enslaved, look there is a plaque up now, it is morally cleansed, now it is OK so off you go. Because this is a chapel, the moral aspect of it is very important. The memorial is designed to be looked up to. You cannot just put up a plaque and say: Here is Rustat, he invested in slavery; people would say what is he doing here? Even if Rustat’s involvement in the slave trade was very small, how much sin do you need to have before you come off the wall? The memorial refers to Rustat’s “industry”; but what did he do? Because his involvement was small, does that get him off the hook? People still have to be responsible for their actions; those who were involved in the slave trade knew that peoples’ lives were being were lost. The only answer to the charge that this was not sinful would be to contend that the victims were not human beings. The Master confirmed that some of the undergraduates had approached her about their concerns and a few, especially those of colour, had told her that they found it very difficult to enter the Chapel. Rustat had invested in the slave trade, he had known what it was about, with slave factories in Africa; and he had been part of an elite circle who had benefitted from their investment in the slave trade. The Master had detected a lack of inter-action on the part of the objectors with the current student body. In response to questions about the College’s involvement with funds from China, the Master emphasised that there had been no substantial funds introduced into the College from that source since she had become the Master; but even if there had been, the College would still have been appearing before the consistory court asking for the removal of this memorial.

- In answer to questions from Professor Goldman, the Master asked rhetorically why young people should have to worship with compromise and a lack of dignity. The Master acknowledged that there was not much in issue between herself and Professor Goldman, but the difference was that she knew her students: they would not meekly come in to the Chapel and say that now they had been informed about Rustat’s life and investments, it was all OK. The College was becoming increasingly diverse. It had been in a state of limbo, waiting for the matter to be resolved. Everyone had been really fantastic in trusting in the process and patiently waiting in the belief that the court would see the harm that had been caused to the College community. The Bible is clear that all people are equal and that Christ died on the Cross for all of us. It is for the Church to identify what barriers it wishes to set up for people who wish to worship in the Chapel. The student body should be free to use the Chapel, not as a “safe space”, but rather as a glorious, inspiring, religious space.

- Mr Vonberg’s evidence addresses: (1) the significance of the Rustat memorial to the Chapel; (2) the process of removing the memorial; and (3) the suitability of the proposed new location. I am satisfied that Mr Vonberg is appropriately qualified, as an architect accredited in building conservation, to express an opinion on such matters. I reject Mr Gau’s submission to the contrary. However, Mr Vonberg is certainly nowhere near as well qualified as Dr Bowdler to speak to heritage and listing matters in general, and funerary monuments in particular. I accept Mr Gau’s further submission that Mr Vonberg was neither truly independent nor impartial. I acquit him of any financial self-interest in the outcome of this petition; but I found him to be partisan, exhibiting a tendency to argue the College’s case (although this was perhaps understandable given his role as the College’s long-serving conservation architect and the nature of his involvement in the attempts to remove the memorial from the wall of the College Chapel).

- Mr Vonberg addresses the significance of the memorial to the Chapel at paragraph 7 of his witness statement. Regarded as a discrete object, Mr Vonberg acknowledges that the memorial clearly has considerable significance as a work of art, and also as a historical record of Tobias Rustat’s life and his role as a benefactor of Jesus College. It is Mr Vonberg’s opinion, however, that the memorial does not contribute greatly to the significance of the Chapel and therefore its removal would cause little harm to the significance of the Chapel as a building of special architectural or historic interest. He offers “three arguments in support of that opinion”: (a) The Chapel’s significance depends infinitely more on its core history and on its fixed and co-ordinated architectural elements than on its memorials and pictures. (b) The paintings and memorials mounted or hung within the Chapel are essentially adornments or embellishments. Mr Vonberg observes that paintings and memorials (of which latter Mr Vonberg assesses that there are some 49 in the Chapel, including eleven to men who died in the 17th century) generally reveal their less fundamental and more temporary characters by various ‘tell-tales’: the variety of their sizes and shapes, their often random placing in relation to the architecture, and their relative portability. (c) The abundance of the locations in which this particular memorial has been fixed reinforces the idea of its being an adornment. Were it the case that the Rustat memorial had been fixed permanently in a position which was definite, a location so obviously and deliberately selected as to be unassailable, its significance might be greater; perhaps still not as great as the windows or the roof, but nevertheless greater than it is. It is thought to have been erected in one, or possibly both, of the transepts of Jesus College Chapel albeit there is some confusion about which one or when. It may have been on the west wall of the nave (its current location) at various times, but it was certainly not there in 1912 when a photograph shows that place occupied by an organ. Mr Vonberg argues that:

- Mr Vonberg addresses the process of removing the memorial at paragraph 8 of his witness statement. He explains that the Rustat memorial comprises some eight separate pieces of hand-carved marble of different sizes, the heaviest weighing perhaps 500 kilogrammes and the complete memorial maybe as much as 3.5 metric tonnes. The memorial is approximately 2.6 metres high and 1.6 metres wide. It is secured to the west wall of the nave with its lowest edge three metres above floor level. It will not become entirely clear how the memorial is secured to the wall until its removal has commenced but it is likely that all the stones are built into the thickness of the wall, secured both by mortar and by several wrought iron cramps. It is anticipated that the services of Cliveden Conservation would be engaged to carry out the specialist work of removing the memorial. Before moving anything, Cliveden would carry out an assessment of the condition of the memorial, label the separate elements, and reattach any loose pieces of stone to avoid any damage during the dismantling. They would also protect the chapel floor, the oak panelling and the oak bench seat below the memorial. There is no reason to suppose that the removal of the memorial will raise any structural issues for the west wall. Mr Vonberg argues that

- Mr Vonberg addresses the suitability of the proposed new location for the memorial at paragraph 9 of his witness statement. He explains that in the preliminary consultation phase, the College’s proposal had been that after its removal from the Chapel, the memorial should be

- During the course of cross-examination, Mr Vonberg accepted that his expertise on 17th century monuments was limited but he said that he had fairly extensive experience in the conservation of listed buildings generally. He acknowledged that the memorial was a very considerable piece of art which was designed to be seen at a height. Mr Vonberg explained that it was not thought that there was anywhere within the Chapel where it would be possible, or appropriate, to display the memorial. He agreed with Dr Bowdler’s assessment of the memorial’s artistic and historic significance but he disagreed with him about the application of the Duffield guidelines. Removing the memorial would cause some harm to the Chapel but Mr Vonberg considered that this would be small enough to be outweighed by the resulting benefits:

- At the start of the hearing Mr Gau indicated that the parties opponent had elected not to call the Reverend Canon Professor Nigel Biggar, the Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford, as a witness. The court therefore heard from four witnesses (in the following order):

- It is unnecessary for me to recite in detail the evidence of the parties opponent. Much of it is directed to what the objectors view as the lack of engagement with their concerns on the part of the College, and what they describe as the marked changes of position on the part of the College over the past couple of years. I accept Mr Gau’s description of the parties opponent as demonstrating proper intellectual curiosity, vigour, and concern for their old College. Having undertaken diligent and helpful research, they felt themselves rebuffed by the College authorities and falsely accused by certain members of the student body as racists and white supremacists. Neither description is accurate: they are loyal Jesuans. The response of the College to their approaches has been a matter of personal sadness to them, but they have had the grace to rise above it.

- Mr Sutton’s helpful research has been largely overtaken by the reports and the joint statement of the historical experts. With the sole exception of Dr Edwards’s failure to address the whole of Rustat’s life by concentrating instead on his involvement with the slave trade, Mr Sutton welcomed the well-researched facts and opinions of the historical experts. He found their joint statement very helpful; and he would hesitate to dissent from their agreed statement. At the end of his cross-examination, the following poignant exchange took place between Mr Hill and Mr Sutton:

- As members of the steering committee of the ‘Rustat Memorial Group’, Mr Farley and Mr Emmison draw attention to the inaccurate statements about Rustat and the source of his wealth contained within the standard form letters and emails in support of the petition sent by various graduate and undergraduate members of the College. They observe that the majority of these supporters must have been materially influenced by the inaccurate historical information they had received from sources within the College about Tobias Rustat and the extent of his involvement in, and the wealth derived from, the slave trade. They comment that it is no wonder that many students supported the College’s petition when they read the “emotional exaggerations” contained in the email sent to all College undergraduates on 19 December 2020 by an undergraduate member of the LSWP (cited at paragraph 41 above). Mr Emmison comments (at paragraph 33):

- Mr Emmison and Mr Farley explain that they oppose the petition for the following reasons:

- As part of his evidence, Mr Emmison produces a 45-page typed letter (received by email on 6 January 2022) addressed to him by a recent post-graduate member of the College (who received an M. Phil in world history) objecting to “the motion” for the removal of the Rustat memorial. (In common with every person who has contributed to these proceedings otherwise than by giving evidence, I will not name the writer.) The author is

- In his original report dated July 2021 Dr Bowdler expressly addresses the Duffield questions. He is exceptionally well qualified to do so, at least on heritage issues. I recognise that the subject of Dr Bowdler’s PhD thesis (on 17th century English church monuments) and his former role (until the summer of 2021) as a council member of the Church Monuments Society both militate against an entirely objective approach to any proposal for the removal of such a significant memorial from the College Chapel (although I take Dr Bowdler’s point that it would be strange to be interested in church monuments and not be a member of the CMS). Dr Bowdler concludes that the College’s proposals will cause substantial harm to the Chapel and that any resulting public benefits would not outweigh this harm. In his more recent statement of 6 January 2022, Dr Bowdler concentrates on issues relating to the significance of the Rustat memorial arising from the College’s witness statements. Intrinsically, Dr Bowdler considers the Rustat memorial to be one of the most important church monuments of the late 17th century in terms of (a) the critical esteem in which it is held, (b) its authorship by one of the greatest craftsmen-sculptors of his age, (c) its style and appearance, (d) its sculptural quality, (e) the interest and importance of its epitaph, and (f) the circumstances of its commissioning. The Rustat memorial was not conceived as a stand-alone item of sculpture capable of being moved from location to location. It was commissioned as a funerary monument: a bespoke piece of commemorative art intended to mark the resting place of an individual in a specific building. Its place within the Chapel has shifted several times but it remains close to Rustat’s grave in the chancel, which is marked by a modest inscription on the floor. To take the monument out of the Chapel would greatly affect its context. The Rustat monument is very rare in its local context of Cambridge college chapels; and it is very special in its specific college context. Dr Bowdler considers that the visual contribution of the monument - one of the key fixtures inside the Chapel - is considerable and that this adds to the significance of the Chapel overall. The College Chapel is strongly medieval in character, with a notable overlay of Gothic revival enrichment from the Victorian era. The monument thus has evident significance as a testament to the post-medieval history of the College, and recalls a major gift to the College. The Rustat memorial possesses artistry of distinction, as well as high historical interest; and it clearly adds to the significance of the Grade I listed Chapel. It is Dr Bowdler’s opinion that:

- As for the third question (the seriousness of the harm), Dr Bowdler is of opinion that because of the clear significance of the memorial, its removal from the Chapel would evidently cause “considerable harm”. The Chapel is largely medieval and Gothic revival in character: the Rustat memorial is by far the most important fixture to date from the lengthy period in between, and it reflects an exceptional relationship between a donor and a college. Cambridge college chapels are not blessed with funerary monuments to the extent that Oxford ones are, which makes this all the more special in local terms. Because the Rustat memorial contributes very clearly to the significance of the Chapel, its removal would cause substantial harm and would deprive future visitors and worshippers of a centuries-old connection with a significant national figure, who is a key figure in the College’s history. Dr Bowdler writes:

- On the fourth question, Dr Bowdler does not find the justification for the removal of the memorial to be either clear or convincing. The statement of significance is inadequate in that it does not identify the grounds of significance, nor does it assess the significance of the Rustat memorial. It deliberately attempts to underplay the monument’s importance, it fails to register the impact of its removal on the Chapel, it displays a regrettable lack of objective balance, and it fails to articulate the case for its removal. Dr Bowdler comments that the supporting document, written by the Dean:

- As for the fifth question, Dr Bowdler does not find the public benefits set out clearly in the application, which makes it difficult for him to reach a view as to the overall balance. The alleged public benefits appear to Dr Bowdler to be:

- In cross-examination by Mr Hill, it was put to Dr Bowdler that he had used the phrase “considerable harm” whilst Historic England had used the phrase “notable harm”. Dr Bowdler could see no difference between the two forms of words; both he and Mr Neale, in his “thoughtful submission”, had been “saying the same thing” Dr Bowdler accepted that his expertise lies in assessing historical significance in listing matters rather than in matters of worship (a point Dr Bowdler had acknowledged at page 21 of his report, where he had said that as his document was “concerned with matters of heritage significance”, he would avoid comment on the “pastoral and missional context”). Mr Gau described the manner of Mr Hill’s cross-examination, with some justification, as “unhelpful ‘hair-splitting’”. I suspect that the reason for this was because it was very difficult to challenge Dr Bowdler’s reasoned opinions.

- In his witness statement, Professor Goldman opposes the removal of the Rustat memorial on historiographical grounds, based on the principles that underpin historical research and historical scholarship. He sets out reasons why the memorial tablet should remain where it is, derived from precedents set by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (the ODNB). At the end, he also makes some strictly historical points about Rustat’s involvement with slavery in the late 17th century, in order to help to clarify his role, although he does not present himself as an expert on this period. However, Professor Goldman begins his evidence in Jesus College Chapel, thinking about another notable biographical monument there, the memorial to the college’s most famous son, Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556). He, more than any other student to have been educated at Jesus, defines the College and its place in British History. Professor Goldman poses the question: ‘If Rustat, why not Cranmer?’ Professor Goldman advocates that the Church of England should not countenance the removal of a monument because it memorialises someone whom we now convict of what are to us, morally unacceptable acts. Sin is a part of life; we are fallen creatures; and in Christian doctrine, Christ redeems us all. Professor Goldman asks rhetorically: How can it accord with fundamental scholarly and religious principles to hide away a monument to someone, the totality of whose acts may be judged both good and bad, both exploitative and beneficent? Historians, churchmen and churchwomen must surely agree that there is no history, no religion, indeed no humanity, without error and sin. Professor Goldman notes that the College wishes to remove Rustat’s monument to another location in the College, wresting it from its place for the last three and a half centuries, and, in the term used by our age, thereby ‘cancelling’ him. A new sensibility and also, perhaps, new knowledge about his investments, apparently justifies this action. But this is neither scholarly nor honest. It obscures Rustat as a historical figure, who is less accessible; and it obscures an honest appreciation of the College’s historic associations with slave trading through Rustat. The fact that a previous generation of fellows of the College took Rustat’s benefaction without demur, and that it has been used for good ends for generations, is now more difficult to appreciate, is lost to history. This may be convenient, because it is less embarrassing; but it is not how historical and biographical scholarship are conducted. An educational institution as reputable as a Cambridge college should be intensely rigorous, accurate and honest in its scholarship, and in the presentation of its history. Professor Goldman suggests that the example of the ODNB may assist. When it was re-written, from 1992 onwards, no subject was ejected on moral, or any other, grounds: all who were thought worthy of an entry by former generations of editors and scholars were kept in the work. But in acknowledgment of our changed views of the past and of the discovery of new information, all articles were reviewed, and more than four-fifths of them were entirely rewritten, to include the latest scholarship. That would be a better option for Jesus College to adopt in dealing with the Rustat memorial. A plaque beside the Rustat memorial could set out his biography and his investments in the slave trade. The College website might then carry pages explaining who Rustat was and what he had done in detail: students, potential applicants, and scholars would learn something, rather than know nothing at all about a man who had been removed from history. “A great college should surely not forgo an educational opportunity, and while about it, Jesus might also update its pages on Thomas Cranmer to present him in light of all the facts and the latest scholarship, as well.” In an age when there are more ways than ever of communicating scholarship, Professor Goldman finds it troubling that the College seeks to remove the Rustat memorial rather than to explain it. “If the Church of England is committed to building a better future for all citizens, it should not agree to the removal of historical evidence which, by demonstrating the sins and mistakes of the past, provides guidance on the way to conduct ourselves now and subsequently. In short, make Rustat’s crimes and sins visible in the chapel and on the website; do not obscure them. Some might consider that a religious as well as an academic duty.”

- Professor Goldman counsels against “judging the past by the standards of the present”. He argues:

- Professor Goldman submits the following as his suggested solution:

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, there was no real cross-examination of Professor Goldman. Mr Gau commended his evidence and submissions.

- Since the College Chapel is a Grade I listed building, this faculty application falls to be determined by reference to the series of questions identified by the Court of Arches in the leading case of Re St Alkmund, Duffield [2013] Fam 158 at paragraph 87 (as affirmed and clarified by that Court’s later decisions in the cases of Re St John the Baptist, Penshurst (2015) 17 Ecc LJ 393 at paragraph 22 and Re St Peter, Shipton Bellinger [2016] Fam 193 at paragraph 39). These questions are:

- When considering the last of the Duffield questions, the court has to bear in mind that the more serious the harm, the greater the level of benefit that will be required before the proposed works can be permitted. This will particularly be the case if the harm is to a building which is listed Grade I or II*, where serious harm should only exceptionally be allowed. I recognise that these questions provide a structure and not a strait-jacket: to adopt a well-worn phrase, these are guidelines and not tramlines. Nonetheless, they provide a convenient formula for navigating the considerations which lie at the core of adjudicating upon alterations to listed places of worship, namely a heavy presumption against change, and a burden of proof which lies upon the petitioners, with its exacting evidential threshold. Since my judgment in Re St Peter & St Paul, Aston Rowant [2019] ECC Oxf 3, (2020) 22 Ecc LJ 265, a practice has also developed of inquiring whether the same, or similar, benefits could be achieved in a manner less harmful to the heritage value of the particular church building concerned. At paragraph 7 of my judgment in that case I said the following (with reference to the fifth of the Duffield questions):