Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Patents Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Patents Court) Decisions >> Nicoventures Trading Ltd v Philip Morris Products SA & Anor [2021] EWHC 1977 (Pat) (14 July 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Patents/2021/1977.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 1977 (Pat)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation [2021] EWHC 1977 (Pat)

Claim No: HP-2020-000011

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (ChD)

PATENTS COURT

Sitting remotely at:

Royal Court of Justice

Rolls Building

7 Rolls Buildings

London EC4A 1NL

Date: 14 July 2021

Before:

THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE MARCUS SMITH

BETWEEN:

NICOVENTURES TRADING LIMITED

Claimant and First Part 20 Defendant

-and-

PHILIP MORRIS PRODUCTS SA

(a company incorporated under the laws of Switzerland)

Defendant/Part 20 Claimant

-and-

BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO (INVESTMENTS) LIMITED

Second Part 20 Defendant

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Mr Adrian Speck, QC and Ms Kathryn Pickard (instructed by Kirkland & Ellis International LLP) appeared for the Claimant/First Part 20 Defendant and the Second Part 20 Defendant

Mr Andrew Lykiardopoulos, QC, Mr Tom Alkin and Mr Edward Cronan (instructed by Powell Gilbert LLP) appeared for Defendant/Part 20 Claimant

Hearing dates: 18, 19, 20, 24 and 25 May 2021

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Approved Judgment

|

CONTENTS | ||

|

A. |

INTRODUCTION |

§1 |

|

B. |

THE EVIDENCE |

§10 |

|

C. |

THE RELEVANT TECHNOLOGY |

§17 |

|

(1) |

Conventional, combustible, cigarettes |

§17 |

|

(2) |

Heat, not burn |

§18 |

|

(3) |

Heating |

§20 |

|

(4) |

Heat, not burn products actually marketed before the Priority Date |

§24 |

|

(a) |

Premier and Eclipse |

§25 |

|

|

Figure 1: Diagram of the Premier heat, not burn product |

§26 |

|

|

Figure 2: Diagram of the Eclipse heat, not burn product |

§29 |

|

(b) |

Accord and Heatbar |

§32 |

|

|

Figure 3: Diagram of the Accord heat, not burn product |

§34 |

|

|

Figure 4: Diagram of the Accord "cigarette" compared to a conventional cigarette |

§35 |

|

(5) |

Pleaded prior art |

§38 |

|

(a) |

Deevi |

§39 |

|

|

Figure 5: The device envisaged by Deevi in its "simplest form" |

§43 |

|

|

Figure 6: Layout of the heater in Deevi |

§44 |

|

|

Figure 7: Cross-section of the heater in Deevi |

§44 |

|

(b) |

Monsees |

§45 |

|

|

Figure 8: Monsees design |

§45 |

|

(6) |

The Patents |

§47 |

|

D. |

THE SKILLED PERSON OR THE SKILLED TEAM |

§54 |

|

E. |

LACK OF INVENTIVE STEP OR OBVIOUSNESS: LAW AND APPROACH |

§60 |

|

(1) |

Introduction |

§60 |

|

(2) |

British American's case |

§62 |

|

(3) |

General points regarding obviousness |

§65 |

|

(a) |

Introduction |

§65 |

|

(b) |

The patent bargain |

§66 |

|

(c) |

Approaches to obviousness |

§68 |

|

(d) |

Collocation |

§72 |

|

(e) |

Prior art and its inter-relationship with common general knowledge in this case |

§78 |

|

(f) |

Philip Morris' approach to its patent portfolio |

§81 |

|

(4) |

Synthesis |

§82 |

|

F. |

THE DISCLOSURE IN THE PATENTS |

§83 |

|

G. |

THE CLAIMS IN ISSUE |

§93 |

|

|

Figure 9: Claims in issue |

§93 |

|

H. |

THE INVENTIVE CONCEPT(S) IN THIS CASE |

§96 |

|

I. |

COLLOCATION |

§97 |

|

J. |

OBVIOUSNESS |

§102 |

|

(1) |

Approach |

§102 |

|

(2) |

Feature B |

§105 |

|

(a) |

The importance of Monsees |

§105 |

|

(b) |

Common general knowledge in this regard |

§107 |

|

(c) |

Monsees |

§109 |

|

(d) |

Obviousness |

§111 |

|

(3) |

Feature A |

§115 |

|

(a) |

Approach regarding the "state of the art" |

§115 |

|

(b) |

Common general knowledge |

§117 |

|

(c) |

Deevi |

§120 |

|

(d) |

Obviousness |

§121 |

|

|

Approach |

§121 |

|

|

The inventive concept and unpacking it |

§127 |

|

|

Obviousness |

§129 |

|

|

Why was it not done before? |

§140 |

|

(4) |

Conclusion |

§147 |

|

K. |

OTHER MATTERS AND DISPOSITION |

§148 |

|

|

ORDER & ANNEX | |

A. INTRODUCTION

1. In these proceedings, the claimant, Nicoventures Trading Limited, seeks declarations of invalidity (and orders that they be revoked, if invalid) in relation to the following patents (collectively, the Patents): [1]

(1) European Patent (UK) No 3,248,483 (the 483 Patent);

(2) European Patent (UK) No 3,248,484 (the 484 Patent);

(3) European Patent (UK) No 3,248,485 (the 485 Patent);

(4) European Patent (UK) No 3,248,486 (the 486 Patent).

The proprietor of all these patents, and the defendant to the claim, is Philip Morris Products SA.

2. By an additional claim brought under Part 20 of the Civil Procedure Rules (the CPR), Philip Morris Products SA counterclaims for infringement in relation to all four patents. The defendants to this counterclaim are the claimant, Nicoventures Trading Limited, and a third party, British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited. The products said to infringe the Patents are referred to herein as the glo device.

3. Nicoventures Trading Limited and British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited are part of the same group of companies. No-one drew any distinction between the companies for the purposes of these proceedings. I shall refer to them together and without differentiation as British American.

4. I shall refer to the defendant, Philip Morris Products SA as Philip Morris.

5. The Patents share a common, uncontested, priority date of 29 October 2009 (the Priority Date). They were prosecuted as "divisional applications" divided out from a common parent application, EP 2,850,956 A1 (the Parent Application), which was itself divided out of WO 2011/050964 (the Grandparent Application).

6. In its written opening submissions, British American was critical of Philip Morris' approach to its patent portfolio. Without in any way adopting what British American says, I quote the following paragraphs:

“9. The specifications of the Patents are essentially the same. The only differences lie in the claims, the integers of which have been arranged in different combinations with only slight changes (if any) between them to create numerous variations on the same theme.

10. All four Patents were applied for on 1 June 2017, some 6 months after the first glo device was launched in Japan. They all derive from the [Grandparent Application], which was published as WO 2011/050964 on 5 May 2011.

11. It is apparent that in formulating its various Patents and their claims sets, Philip Morris has not been guided by what it considers its true invention (if any) to be. Instead, Philip Morris' motivation is to maximise its chances of a finding of infringement by mining its Grandparent Application for individual features, which it then crafts together in a myriad of different ways to create a claim set that (so far as possible) maps onto the resistive-heating glo device.

12. Philip Morris is continuing to pursue that approach, both by proposing additional features by way of amendment and by spinning out further patents from the original Grandparent Application. On the latter point, on 23 April 2021, the European Patent Office published its notice of intention to grant a fifth patent, European Patent (UK) No EP 3,248,487 (EP 487). EP 487 is to [be] yet another combination of the integers making up the claims of [the Patents] but, as it has not yet been granted, [British American] cannot yet apply for its revocation.

13. In approaching its patent portfolio in the way that it does, Philip Morris is taking advantage of the system of "divisionals". The divisionals system was put in place as a way to permit a patentee who has included more than one invention in its original application the opportunity to correct that and avoid the objection of multiplicity of inventions that would otherwise be raised by the patent office.

14. The system of divisionals allows a patentee who has filed a patent application to file further patent applications based on the original application and to claim the priority date of the original application. Provided that the original application is still pending (e.g., it has not proceeded to grant or been withdrawn), there is no limit to the number of divisional applications that the patentee can file.

15. The system also permits divisional applications to be based on applications which themselves are also divisional applications, leading to the monikers “Grandparent”, “Parent”, etc…”

7. It is thus clear that - given the number of divisional patents - some care needs to be taken when referring to the relevant specification and claims. The parties were agreed that although there were differences between the specifications in the Patents, the Parent Application and the Grandparent Application, primary reference could made to the specification in the 486 Patent. Save where the contrary is stated, all references in the Judgment to the specifications is to the specification in the 486 Patent.

8. As I have stated, these proceedings began as an action by British American for revocation of the Patents. Philip Morris defends the validity of the Patents, but has also made an application for the conditional amendment of the Patents. The amendments advanced are conditional in that they are only put forward if they are needed to save the Patents. These amendments are objected to by British American, who also contend that the amendments (even if not objectionable) would not save the validity of the Patents in any event. For its part, Philip Morris contends that British American are infringing the Patents, if they are valid and not revoked.

9. This Judgment considers the following matters in the following order:

(1) Section B describes the evidence that was before me.

(2) Section C describes the relevant technology. This Section, intended by way of background, describes the heat, not burn approach and technology; the heat, not burn products actually marketed before the Priority Date; the prior art relied upon by British American; and the technology described in the Patents. This Section make no findings as to:

(a) What constituted common general knowledge.

(b) What might (or might not) be obvious in light of this common general knowledge, and/or the prior art pleaded and relied upon by British American.

(c) The true meaning and construction of the Patents.

These are all matters considered in later sections of the Judgment.

(3) Section D considers the nature and characteristics of the skilled person or skilled team in this case.

(4) Section E sets out the law regarding obviousness and the approach that I take given the facts and circumstances of this particular case. The following sections then consider various matters relevant to obviousness, notably the disclosure in the Patents (Section F), the claims in issue (Section G), the inventive concepts in this case (Section H), collocation (Section I), culminating in the question of obviousness itself (Section J).

(5) Section K deals - very briefly, given my conclusions on obviousness - with the other matters in issue, and states how the claim and counterclaim are to be disposed of.

B. THE EVIDENCE

10. I heard evidence from two experts, Mr Jason Hopps, who was called by Philip Morris and Mr Martin Wensley, who was called by British American. Although British American was technically the claimant, the parties were agreed that the proceedings should be conducted as if Philip Morris were the claimant.

11. Accordingly, Mr Hopps was called to give his evidence first, which he did on Day 1 (18 May 2021) and Day 2 (19 May 2021). Mr Hopps is a research scientist with 15 years of experience in tobacco, tobacco product and electronic cigarette research and design. Although clearly knowledgeable across the multiple fields that this area of research entails, Mr Hopps' expertise was greatest in relation to tobacco and the manner in which - when heated or burned - it could create a pleasing sensation to the user, typically a smoker used to combustible cigarettes.

12. Mr Hopps provided two reports on which he was cross-examined:

(1) His first expert report (Hopps 1) dated 19 March 2021; and

(2) His second expert report (Hopps 2) dated 30 April 2021. This second report was responsive to Mr Wensley's first report, which I shall come to describe shortly.

13. Mr Wensley gave his evidence on Day 2 (19 May 2021) and Day 3 (20 May 2021). Mr Wensley is an engineer. He qualified with a degree in physics in 1980, and (from a career that started in architectural design and construction management) in 1990 transitioned into an engineering role. Mr Wensley has held a variety of positions of increasing seniority as an engineer, but none of them have been in the tobacco industry. Like Mr Hopps, he was cross-examined on two reports:

(1) Wensley 1 dated 19 March 2021; and

(2) Wensley 2 dated 30 April 2021.

14. That was the totality of the witness evidence before me. British American served, in the course of the proceedings, a product and process description in relation to the Glo Products (the PPD). [2] The PPD was produced and signed by Mr Tom Woodman, a senior manager in product development in British American. Philip Morris indicated that it did not need to cross-examine Mr Woodman, and he did not attend to give evidence before me. I accept the PPD as accurate.

15. Both Mr Hopps and Mr Wensley were not merely expert in the fields that I have described, but were sufficiently well informed about patents to address in a competent way the patent law issues that arose in the proceedings. Both Mr Hopps and Mr Wensley had a number of patents to their name. They gave evidence completely in accordance with their duties as experts and did their best to assist the court. I am very grateful to them. Whilst - as is clear from the substance of this Judgment - I do not accept the evidence of either expert unqualifiedly, that is in no way a reflection of the integrity of their evidence or their qualification as experts. In closing, both sides made criticisms of the other side’s expert: I do not consider that there was anything in these criticisms. As will be seen, a great deal of this Judgment focusses on the engineering aspects of heat, not burn devices, as opposed to the properties of the tobacco that would be heated by such a device (although that is, obviously, a point of some importance to the success of the device). I rely rather more on Mr Wensley in relation to these engineering aspects - in particular, in relation to the technical aspects considered in Section C below. That is, in part, because this reflects Mr Hopps’ different expertise; but it is also because Mr Wensley set these matters out in greater detail in his reports, and was not challenged on this detail.

16. Considerable reference was made to the evidence in proceedings before Meade J and Meade J’s decision in Philip Morris Products SA v. RAI Strategic Holdings Inc. [3] I was not assisted by this. Whilst the issues before me and before Meade J were - in some respects - similar, these common issues were factual in nature. Both Meade J and I are obliged to decide the issues before us on the evidence adduced before us. Mr Hopps, in particular, was often cross-examined through the prism of evidence that was produced (not by him) in the earlier Philip Morris case before Meade J. Whilst Mr Hopps did his best to answer questions so put, and whilst I have, of course, paid full account to Mr Hopps’ answers to these questions, given the complex and nuanced nature of the evidence before Meade J (in the earlier Philip Morris case) and me (in this case), I was not assisted by selected gobbets of earlier evidence being placed before Mr Hopps for his comment.

C. THE RELEVANT TECHNOLOGY

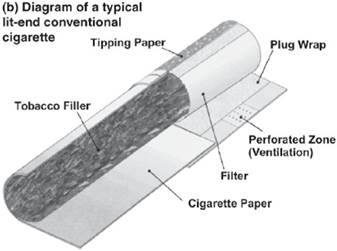

(1) Conventional, combustible, cigarettes

17. Conventional, combustible, cigarettes supply smokers with nicotine. When lit, the combustible cigarette burns, and produces heat. This heat vaporises chemicals in the tobacco - like nicotine, but other chemicals, also - to form a gas. As the smoker inhales, the gas travels along the interior of the cigarette, where it cools and forms a condensation aerosol with smoke particles. An aerosol is a liquid or solid suspended in a gas phase. The aerosol then enters the smoker's lungs, where the nicotine is absorbed. [4]

(2) Heat, not burn

18. The technology in this case concerns “heat, not burn” products, intended to produce a similar effect and experience to smoking combustible cigarettes. In the case of heat, not burn products, the tobacco is heated, rather than burned. The aim is to create a process that still produces a nicotine-containing aerosol for inhalation, but where this aerosol contains fewer of the undesired byproducts that would otherwise result from the combustion of tobacco. In other words, heat, not burn products involve producing an aerosol that is, or at least is intended to be, less harmful than the aerosol produced by combustible cigarettes, whilst providing the smoker with a similar experience. [5]

19. Providing a smoker with a similar experience involves seeking to replicate the experience of smoking a combustible cigarette. There are many aspects to this: [6]

(1) Nicotine delivery. It is necessary to mimic the pharmacokinetics of nicotine delivery, so that users of the heat, not burn product experience the same nicotine "hit" that they would experience with a combustible cigarette.

(2) The draw experience. Users will want to have a similar "draw" experience (that is, resistance to inhalation), including exerting a comfortable amount of force drawing the aerosol into their mouth and lungs.

(3) The sensory experience. Users will want a similar sensory experience to a combustible cigarette, including flavour and "throat hit" (the feeling produced at the back of the throat by the smoker when smoking a combustible cigarette).

(4) Convenience. The heat, not burn product should seek to provide the same convenience as a combustible cigarette. Thus, the device needs to be portable, and quickly, easily and conveniently activated on demand.

(5) Rituals. This is intended to refer to the other intangible benefits a smoker is perceived to derive from smoking - the overall experience needs to feel like that of smoking.

(3) Heating

20. A - perhaps the - critical aspect of heat, not burn smoking is the question of how the product is to be heated. In the case of the combustible cigarette, this is straightforward. The tobacco inside the cigarette burns in a consistent manner along the long axis of the cigarette. When the user puffs, air flow accelerates the burning, and liberates more aerosol. The process has been finely tuned over the years, and is not specifically relevant for present purposes.

21. In the case of heat, not burn products, heat is applied to tobacco that has been impregnated with propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin and/or other appropriate carriers to assist with aerosol generation. Factors that must be considered are (in addition to the composition of the tobacco): [7]

(1) The form of the tobacco. Thus, tobacco can be formed into “rolls” or “mats”, amongst other things, and these mats can be made up of tobacco differently formed, including shredded tobacco.

(2) The temperature to which the tobacco needs to be heated. Of course, this temperature will be lower than in the case of the combustible cigarette, but it will still be up to several hundred degrees Celsius.

(3) The positioning of the heater. Heat could be applied to the tobacco either externally (by surrounding or wrapping the tobacco) or internally (through the use of some kind of heat probe). As will be seen, a variety of different configurations has been used.

(4) The manner in which heat is applied (i.e., its speed and consistency) and how the heating process is commenced or activated, which are all factors related to the control of the heat.

(5) The power supply to supply energy for heating. Heat might be provided by electric power (which implies batteries, if the device is to be portable) or chemically (which implies a gas heater).

(6) Safety factors and factors of convenience. Safety issues are various. For example, it would be necessary to avoid “off-gassing”. Off-gassing is the production of a gas from a material, which is generally greater on heating. This is undesirable, and presents toxicity concerns. It would be important to avoid off-gasses emanating from the construction of the heat, not burn device. Equally, as I have described, heat, not burn devices involve the application of heat - perhaps for relatively short bursts, but perhaps longer - which could injure or seriously discomfort the user, unless appropriately protected. Thermal insulation - as well as having a safety/convenience aspect - would also ensure that the heat remained where it was supposed to be: by the tobacco product.

22. As is clear, application of heat to the tobacco product is critical, and so the component(s) used to generate and apply such heat are similarly important. There are several categories of heater, and within those categories, many individual products. For present purposes, it is necessary to identify and describe three classes of heater: [8]

(1) Electrical resistive heaters. The electricity would be supplied by a battery, most likely (if portability was an issue) a Lithium battery. A resistive heater relies on electrical resistance to generate heat. Electric current passing through a material encounters resistance, the amount of the resistance being dependent (amongst other things) on the materials involved. The resistance converts some of the electrical energy into thermal energy.

(2) Electrical inductive heaters. Induction heaters rely on electromagnetic induction. The induction heater applies a high-frequency alternating current to a coil to produce an oscillating magnetic field. The field itself does not directly heat anything, but rather induces an electric current in electrically conductive material, thereby causing the conductive material to heat.

(3) Chemical heaters. Chemical heaters rely upon a chemical reaction to produce heat, for example by burning a carbon fuel element. The chemical reaction, which gives off heat, can be used to heat the tobacco. Of course, given the nature of the device here under consideration (heat, not burn) the tobacco would have to be isolated from the burning fuel element so as to prevent the tobacco itself from burning.

23. Of course, the control systems needed to control the heat source (and so the heat) will vary according as to the heat source.

(4) Heat, not burn products actually marketed before the Priority Date

24. Before the priority date of the Patents, a number of heat, not burn products were produced and marketed. These products are described in the following paragraphs.

(a) Premier and Eclipse

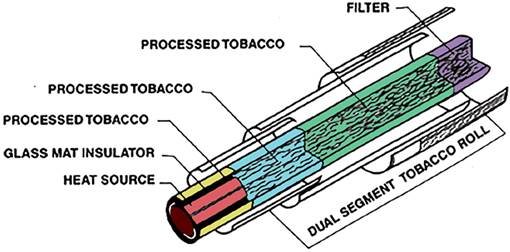

25. Premier and Eclipse were two single-use (i.e., disposable), heat, not burn products launched by RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company in the late-1980s and early-1990s. The Premier product looks very much like a combustible cigarette, but is very different in construction and operation. Describing it from its tip, and then proceeding down the device's long axis: [9]

(1) At the very end of the cigarette is a heat source, wrapped in a glass-mat insulator. The heat source was a chemical heat source, lit by the smoker in a conventional way.

(2) Next down the long axis is a hollow aluminium capsule, containing a substrate, and surrounded by a tobacco roll.

(3) Thereafter, there is a tobacco-paper filter and a filter.

The entire device is wrapped in outer-wrap paper or tipping paper.

26. Diagrammatically, the device looks like this:

Figure 1: Diagram of the Premier heat, not burn product

27. The Premier device works in the following way:

(1) As the smoker lights the cigarette, the heat source (coloured red) ignites and begins to burn. With each puff, a portion of the incoming air is drawn through the passageways in the heat source and heats the aluminum capsule (coloured blue). The heat is transferred to the tobacco roll (coloured orange) and the alumina substrate (coloured blue) both during puffing and between puffs.

(2) Another portion of the incoming air is heated by the heat source (coloured red). It passes through the glass mat (coloured yellow) and heats the tobacco roll (coloured orange) directly. The heat transferred to the alumina substrate (coloured blue) is sufficient to vaporise the glycerol, added flavour and the natural flavours, including nicotine, of the spray-dried tobacco. The heat transferred to the tobacco roll (coloured orange) is sufficient to vaporise its natural flavors, including nicotine.

(3) As the hot vapours exit the rear of the capsule and the tobacco roll (coloured orange), they enter the tobacco-paper filter (coloured green), where they begin to cool. The less volatile components condense to form very small liquid particles. These small particles and the vapour in which they are entrained constitute the smoke that then passes through the polypropylene filter (coloured purple) and out of the cigarette. This smoke provides the taste, sensations and enjoyment of other cigarettes without burning tobacco.

(4) During smoking, the only parts of the cigarette that burn are the carbon heat source (coloured red) and a small amount of paper around the end of the cigarette. When the carbon burns, the major products are water and carbon oxides. Therefore, after the lighting puffs, virtually no sidestream smoke is emitted from the lit end of the device when compared to other cigarettes. Since the tobacco and other components do not burn, the device does not burn down and produce loose ash as do other cigarettes.

(5) The insulator mat (coloured yellow) and paper that surround the heat source (coloured red) simulate the ash and fire cone of other cigarettes. The insulator mat (coloured yellow) also insulates the heat source (coloured red), improving performance and lowering the propensity for this cigarette to accidentally ignite combustible substances it may contact.

28. Premier was not a commercially successful product, and was shortly discontinued after its launch. [10]

29. Eclipse was a next generation version of Premier, broadly similar in concept. [11] Diagrammatically, it is set out below:

Figure 2: Diagram of the Eclipse heat, not burn product

30. The device works in a manner similar to that of the Premier product, save that the aluminium capsule and tobacco mat have been dropped from the design, in favour of two segments of processed tobacco (coloured blue and green).

31. Like Premier, Eclipse was not a commercial success.

(b) Accord and Heatbar

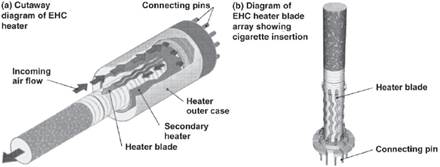

32. Accord and Heatbar were two, later, heat, not burn products launched by Philip Morris in the late-1990s and mid-2000s respectively. [12] These devices were not single use, but were intended to be reusable. The heating was electrical, powered by battery. The concept involved the insertion of a cigarette-like stick (but shorter and differently composed) into a heating device, that heated parts of the surface of the cigarette-like insertion sequentially and for relatively short bursts.

33. Unlike the Premier and Eclipse devices, these devices were not disposable, but were designed to heat (disposable) cigarette-like insertions.

34. The relevant parts of the Accord device looked like this:

Figure 3: Diagram of the Accord heat, not burn product

35. The disposable insert looked a lot like, but was very different from, a conventional, combustible, cigarette:

Figure 4: Diagram of the Accord "cigarette" compared to a conventional cigarette

36. The heating process was as follows. The heater contained an array of eight heater blades made from an iron-aluminide alloy, one blade for each of the eight possible puffs per cigarette. The heater was puff activated and the sequence of blade firing and energy delivery to the heater blades was controlled electronically. The energy to each blade was delivered in 1.93s, with different energy rates for the two heating phases. In the first heating phase, the most rapid heating occurred with 63% of the total energy being delivered in 41% of the heating period.

37. The Accord - which (like the Premier and Eclipse devices) was also not commercially successful - was succeeded by the Heatbar, which had a similar design, and which also failed commercially.

(5) Pleaded prior art

38. Two pieces of prior art were relied upon by British American. These were Deevi (US Patent No 5,322,075) (Deevi) and Monsees (US Patent Application No 2007/0283972) (Monsees). Deevi is dated 21 June 1994 (this is the date of the patent publication, not the priority date), whereas Monsees is dated 13 December 2007 (the date of the application publication, not the priority date).

(a) Deevi

39. Deevi is a patent for a heater for an electric, flavour-generating article, in which a flavour-generating medium - e.g., tobacco - is heated electrically to produce a flavour-containing aerosol for delivery to a consumer. The heat is provided by way of an electrical resistance heater.

40. The summary of the invention provides:

“…an electrical resistance heater manufactured by printing conductive and resistive materials on a flexible substrate. The heater can be manufactured using mass-production printed circuit techniques. The flexibility of the substrate allows the heater to be shaped into a tubular form suitable for incorporation into a smoking article of the same size and shape as a conventional cigarette.

The heater may include several heating elements which are connected in a two-dimensional array configuration. The two-dimensional array requires a minimum number of electrical connections to selectively concentrate power on an individual heater element.”

41. In the “Detailed description of the preferred embodiments”, Deevi discloses that the heater may be used in an electric flavour-generating article that includes a source of electrical energy, electrical or electronic controls for delivering electrical energy from the source of electrical energy to the heaters in a controlled manner, and a flavor-generating medium in contact with the heater. Deevi goes on to explain that the action of the heater on the flavour-generating medium causes a vapour or aerosol to be generated or released, which can be drawn in by the user. The flavour-generating medium can be any material that, when heated, releases a flavour-containing substance and includes tobacco and other aerosol-forming material, which give the user the perception of smoking a conventional cigarette.

42. The flavour-generating medium is deposited as a coating onto the heating elements. The device described in Deevi is, thus, a disposable unit at least so far as the heating elements are concerned. Once the coating on the heating elements has been vapourised, it cannot be replaced. By dividing the flavour generating medium into individual charges, each charge can represent one puff of the smoking article.

43. Below is a diagram of the device envisaged by Deevi in its “simplest form”:

Figure 5: The device envisaged by Deevi in its “simplest form”

More specifically as to the operation of this device:

(1) The device is effectively in three distinct sections, comprising (from the left):

(a) An optional mouthpiece (number 113, coloured green).

(b) A heater section (number 11), comprising various components, in particular a heater (number 110, coloured orange), in which the heating elements (number 201) are coated with a flavor-generating medium (number 202). The several heating elements (number 201) sequentially heat different portions of the medium to produce an aerosol. The aerosol then passes through the filter material (number 112, coloured purple) and the optional mouthpiece (already described) to the user.

(c) Deevi also discloses that section 11 is wrapped in a tube, which Deevi states can be made of heavy paper, to allow it to be inserted by a user into the next section (number 12), which is the power section. This contains, amongst other things, a power source (number 121, coloured yellow) and controls.

(2) Air enters the device via perforations (number 126) in the outer wrapper of sections 11 or 12, which could be conventional cigarette or tipping paper. In addition to air entering the device via these perforations, Deevi also discloses that air may enter through the (upstream) end of section number 12 and that channels may be provided for that purpose, which carry air around the power source (number 121, coloured yellow) and around other internal components of section number 12.

(3) Deevi discloses that it is important that the air enters section number 11 at a point at which it can fully sweep heater number 110 (coloured yellow) to carry the maximum amount of flavour-generating substance to the user's mouth.

(4) Section number 12, as stated, contains the power source (number 121, coloured yellow) and control components (coloured pink). The control components are made up of a push button (number 125), knob (number 122), and rotary switch (number 123). Deevi also discloses that section number 12 may be opened to replace the battery (to the extent rechargeable batteries are not used).

(5) In operation, the user connects section number 11 to section number 12 via a set of pins (number 114) in the heater (number 110) and a set of sockets (number 120) in the power source (number 121). The knob (number 122) controls the rotary switch (number 123) to select which heater element (number 201) to power. When the user presses the push button (number 125), the selected heater element (number 201) energises to heat the corresponding flavour-generating medium (number 202).

(6) When all ten charges in section number 11 have been heated, section number 11 is spent and can be unplugged from section number 12. A new section number 11 can then be plugged in.

(7) While the control system in this diagram is manual, Deevi notes that an automatic system may be used. Specifically, a “more preferred embodiment of an article according to the present invention includes controls that automatically select which charge will be heated, initiate heating in response to a certain stimulus (for example, the user's inhalation), and control the duration of the heating of each flavor charge”.

44. Turning more specifically to the design of the heater within the device described by Deevi, the heater is set out in the two diagrams below. The first (Figure 6) shows the layout of the heater, whilst the second (Figure 7) shows a cross-section of Figure 6:

Figure 6: Layout of the heater in Deevi

Figure 7: Cross-section of the heater in Deevi

As to this:

(1) The heating elements (number 201, coloured red) are formed on the flexible substrate (number 205, coloured orange). Deevi states that the flexible substrate typically is a non-conductive, heat resistant material, with a low dielectric constant. Deevi also states that the substrate must withstand 400-450°C temperatures to extract tobacco aerosol without releasing undesirable volatiles or otherwise degrading. Deevi discloses that “certain polyamide polymers have been found to remain stable and flexible under these extreme temperature conditions” and identifies two specific brands (Upilex by ICI; and Kapton by DuPont) as providing such stability at temperatures upwards of 500°C. Upilex and Kapton are both polyimides. Deevi further discloses that certain fibrous materials are suitable for use and identifies Nomex, a DuPont brand pure cellulose paper and cloth, and paper coated with an inorganic salt or sol-gel.

(2) Deevi discloses that the heater element (number 201, coloured red) is generally made of conductive ink with a resistance such that it produces heat when a voltage is applied (i.e., a resistance heater [13]). Deevi goes on to describe how a heater can be manufactured using a flexible substrate and conductive ink. The ink is made from a conductive material such as graphite, carbon black, or metal powder (with gold and silver being preferred). The ink also contains an adhesive, such as epoxy resin, to bind it to the substrate (number 205, coloured orange). Similarly, the ink contains a solvent such as alcohol to dissolve and disperse the ingredients into a solution.

(3) Deevi also describes insulating the substrate from the heater if a heat resistant substrate cannot be found. The insulator would serve to protect the substrate by reducing heat transfer to the substrate. Alternatively, Deevi describes using a thermally conductive support for the substrate should heating exceed a critical value. For example, aluminized paper could be used as a substrate with the aluminum sub-layer being used to conduct heat away from the paper and dissipating it, thereby keeping the paper from exceeding the critical value.

(4) As an alternative to a heater element made of conductive ink, Deevi discloses that a resistor may be deposited onto a polymeric substrate by thermal spraying onto the substrate a variety of transition metals, alloys, or oxide ceramics.

(5) Deevi discloses, by reference to the figures set out above, that a tubular shaped heater can be formed: "an edge 206 of substrate 205 could, for example, be bent over so as to come into proximity with edge 207 of substrate 205, and thus form a tubular-shaped heater shown as unit 110...".

(6) Each heater element (number 201, coloured red) is connected to a common connection (number 203, coloured purple) and heater element connection (number 204, colour blue). Pins (number 114, coloured yellow) provide electrical contacts for each heater element connection (number 204, coloured blue). Likewise, the common connection (number 203) and heater element connections (number 204) are electrically conductive. In operation, voltage is applied across the common connection (number 203, coloured purple) and one of the heater element connections (number 204, coloured blue), thereby causing the corresponding heater element (number 201, coloured red) to heat.

(7) Each heater element (number 201, coloured red) is covered with a flavour-generating medium (number 202, coloured green). Deevi discloses that the flavour-generating medium can be any material that, when heated, releases a flavour-containing substance and includes tobacco and other aerosol-forming material.

(8) When a heater element (number 201, coloured red) is activated, the corresponding flavour-generating medium (number 202, coloured green) vaporises to produce an aerosol. In operation, Deevi contemplates spiking the temperature to at least 450°C during a pulse of less than one second. Ten such heater elements are shown in Figure 6, thereby providing ten charges. When all ten charges are spent, the user discards and replaces section number 12 (i.e., the heater portion and charges are disposable).

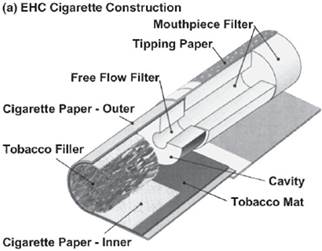

(b) Monsees

45. Monsees describes a heat, not burn design that can use chemical, alternatively, electrical heat. The focus in Monsees is on the use of chemical heating, in the form of a butane heater. Figure 8 below shows the general design of the device with chemical heating:

Figure 8: Monsees design

(1) The tubular case (number 12) includes a vaporization chamber (number 15, coloured green), in which the user can introduce a removable tobacco cartridge (number 30). The cartridge is heated using the heater (number 16, coloured red). The desired operating temperature is below 204°C, and preferably below 177°C. Monsees thus relates to a heat, not burn system.

(2) As the cartridge heats, vapour generates within the cartridge and in the space immediately above it. When a user inhales on the mouthpiece (number 11, blue), air enters via the air inlet (number 22), mixes with the vapour, and is delivered to the user via the inhalation passage (number 23). Once the cartridge is consumed, it is removed and disposed of.

(3) This configuration uses chemical heating. Specifically, the heater burns butane, which is stored in a tank (number 21). According to Monsees, “[b]utane was found to be the most energy-dense and practical fuel source. In alternate embodiments of the invention, the butane heating system is replaced by a battery-powered electric heater or other compact heat source”.

46. Monsees also disclosed various control systems, as well as insulation.

(6) The Patents

47. The Patents are entitled “[a]n electrically heated smoking system with improved heater”. As I have noted, the specifications of the Patents are substantially the same, [14] and (unless the contrary is stated) all references are to the 486 Patent.

48. Each of the Patents relates to “an electrically heated smoking system including a heater for heating an aerosol-forming substrate”, [15] preferably at a temperature that does not burn the aerosol-forming substrate. [16] Clearly, therefore, the Patents relate to a heat, not burn system.

49. The heating system described is unequivocally electrically powered.

50. The Patents disclose two “aspects” of the invention. The first aspect [17] describes an electrically heated smoking system in which the heating element acts as both a heater and a temperature sensor. This is achieved by using a heater that comprises one or more electrically conductive tracks on an electrically insulating substrate where the temperature coefficient of resistance of the electrically conductive tracks is such that they can act as both a resistive heater and as a temperature sensor. The Patents disclose a number of advantages of this first aspect in terms of: (i) reducing the number and size of components required and therefore the overall size of the system; (ii) the ability to incorporate all of the necessary electronics, wiring and connections on the same electrically insulating substrate as the heater; (iii) more straightforward and cost effective manufacture of the heater compared with some prior art heaters that required each heating element to be individually formed; and (iv) flexibility in the heater design.

51. The second aspect [18] describes a thermally insulating material for use in an electrically heated smoking system. This serves to reduce heat loss from the heater and also protect the user from burning. As to this, the specification provides: [19]

“...The thermally insulating material is preferably positioned around the aerosol forming substrate so as to provide the greatest thermal insulation. The thermally insulating material must be a material which will not degrade in the high temperatures reached in the electrically heated smoking system. Not all thermally insulating materials will be suitable. Preferably, the thermally insulating material comprises a metal or another non-combustible material. In one example, the metal is gold. In another example, the metal is silver. A metal is advantageous as it may reflect heat back into the electrically heated smoking system.”

52. It goes on to say: [20]

“Preferably, the thermally insulating material comprises a plurality of air cavities. The air cavities are arranged in a regular pattern. In one preferred embodiment, the air cavities are hexagonal and arranged in a honeycomb structure. The thermally insulating material may be provided on the electrically insulating substrate in addition to the electrically conductive tracks. This allows the electrically conductive tracks and thermally insulating material to be manufactured as one element. For some methods of manufacture, the electrically conductive tracks and the thermally insulating material may be made as part of the same process. Alternatively, the thermally insulating material may be provided in the electrically heated smoking system as a separate element.”

53. The Patents go on to refer to three manufacturing methods for the heater by reference to Figures 1, 2 and 3. The first is a technique similar to a screen printing process; the second is based on PCB (printed circuit board) manufacturing technology; and the third is based on photolithography technique. The Patents disclose that the second, PCB, manufacturing method can also be used to make the honeycomb structure of the thermal insulator.

D. THE SKILLED PERSON OR THE SKILLED TEAM

54. The person “skilled in the art” is expressly referred to in the statutory provisions relating to obviousness and insufficiency. The correct identification of such a person or team of persons can have important consequences for the identification of the common general knowledge in the art, the construction of the specification, and therefore for the issues of infringement and/or validity. [21] As Jacob LJ explained in Technip France SA's Patent: [22]

“The “man skilled in the art” is invoked at many critical points of patent law. The claims of a patent must be understood as if read by that notional man - in the hackneyed but convenient phrase the “court must don the mantle of the skilled man”. Likewise, many questions of validity (obviousness and sufficiency for instance) depend upon trying to view matters as he would see them.”

55. As Terrell notes, [23] disputes as to the identity of the person skilled in the art often involve the following questions:

(1) What is the relevant art?

(2) Should the “person skilled in the art” be taken as comprising a team, each member bringing a particular skill, and if so then what is the composition of that notional team?

(3) What are the attributes and qualification, and in particular the level of skill, of the notional skilled person or team?

On all such matters, evidence is admissible.

56. The general characteristics or attributes of a person skilled in the art were described by Lord Reid in Technograph v. Mills & Rockley [24] and expanded upon by Jacob LJ in Technip France SA's Patent: [25]

“It is settled that this man, if real, would be very boring - a nerd. Lord Reid put it this way in [Technograph]:

“…the hypothetical addressee is a skilled technician who is well acquainted with workshop technique and who has carefully read the relevant literature. He is supposed to have an unlimited capacity to assimilate the contents of, it may be, scores of specifications but to be incapable of a scintilla of invention. When dealing with obviousness, unlike novelty, it is permissible to make a "mosaic" out of the relevant documents, but it must be a mosaic which can be put together by an unimaginative man with no inventive capacity.”

The no-mosaic rule makes him also very forgetful. He reads all the prior art, but unless it forms part of his background technical knowledge, having read (or learnt about) one piece of prior art, he forgets it before reading the next unless it can form an uninventive mosaic or there is a sufficient cross-reference that it is justified to read the documents as one.

He does, on the other hand, have a very good background technical knowledge - the so-called common general knowledge. Our courts have long set a standard for this which is set out in the oft-quoted passage from General Tire v. Firestone Tire & Rubber, which in turn approves what was said by Luxmoore J in British Acoustic Films. For brevity I do not quote this in full - Luxmoore J's happy phrase "common stock of knowledge" conveys the flavour of what this notional man knows. Other countries within the European Patent Convention apply, so far as I understand matters, essentially the same standard.

The man can, in appropriate cases, be a team - an assembly of nerds of different basic skills, all unimaginative. But the skilled man is not a complete android, for it is also settled that he will share the common prejudices or conservatism which prevail in the art concerned.”

57. Both Mr Hopps and Mr Wensley gave evidence as to the nature of the skilled person or skilled team in this case:

(1) Subject to one minor point - which I discount - the experts agreed that the skilled person, in this case, would be a team of nerds, not a single nerd. Mr Hopps took the view that the Patents were directed to a team involved in the research and development of heat, not burn products. The development and design of such products would require expertise in various fields, including cigarette/tobacco development, material science and mechanical and electronic engineering. The team would be a specifically assembled skilled team within a tobacco company. [26]

(2) Mr Wensley identified the skilled person as a lead product engineer seeking to develop a heat, not burn device. [27] That person would be part of a larger team bringing a heat, not burn product to market: [28]

“This team could include, for example, tobacco chemists, graphical designers, tool designers, industrial engineers, electrical engineers, mechanical engineers, software engineers, etc. The Skilled Person would lead this multidisciplinary team in developing a [heat, not burn] product. For the purposes of the Patents, it is the lead product engineer (rather than the team) who is the Skilled Person.”

(3) With absolutely no disrespect to Mr Wensley, I found this distinction between a skilled person leading a team, and the skilled team, to be unhelpful. It seems to me that there should be no difference between a team lead by a non-heating engineer (say a technically unskilled manager) and a team lead by a heating engineer. The fact is that the team is a construct - just as is the skilled person - and to focus on who leads the team would begin to place a premium on precisely those sort of skills (inventiveness; curiosity; good communication) that an assembly of skilled persons might not have. It seems to me, therefore, better to suppose the assembly of nerds, having all the characteristics of the single skilled person, but walking in lockstep and communicating and pooling their common general knowledge as appropriate, but without originality and without the true hallmarks of leadership. [29] Mr Wensley did not particularly disagree with this approach: [30]

|

Q (Marcus Smith J) |

...is there any particular magic in who leads the team? I mean, you have defined the skilled person, in paragraph 24 of [Wensley 1], as the lead product engineer. Now, if we delete "skilled person" and insert "skilled team", really all I am interested in, and I raise this to see whether you disagree, is the qualities of the people in the team, and I am taking as read that whoever leads the team, whether they are an engineer or a tobacco specialist or, frankly, a management guru, they will use the team in an effective way to extract from the team the relevant knowledge that they need to achieve the goal, which in this case is the evolution of an innovative new product? |

|

A (Mr Wensley) |

My Lord, I think that is a very good description of it, and I agree with you. |

(4) There can be no doubt that to develop an effective, commercial, heat not, burn product requires a team with a range of skills. The commercial failures of the sophisticated heat, not burn products that made their way to market, but failed, is testimony to this. [31] However, given the subject-matter of the Patents, there is no doubt in my mind that it is the common general knowledge vesting in the "product engineer" that would be critical in this case. That is not, in any way, to diminish the general importance of (for example) tobacco chemists. It is simply - given the fact that this case turns on the engineering questions of heating and insulation - the primary focus must be on the product engineer and his or her knowledge.

(5) Of course, the common general knowledge of the product engineer would be supplemented by the other members of the team but - for the reasons I have given - I pay particular attention to Mr Wensley's description of this particular skilled person within the skilled team: [32]

“The Skilled Person would have at a minimum a Bachelor’s degree in the physical sciences, such as physics, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, or a closely related subject. The Skilled Person would also have at least 10 to 15 years of experience developing high-volume small consumer devices incorporating heaters. For example, heaters may be found in medical equipment (e.g., inhalers), laboratory equipment (e.g., sample heaters), outdoor equipment (e.g., access card readers), kitchen equipment (e.g., toaster ovens), clothing (e.g., heated gloves), etc. The Skilled Person would be familiar with small heaters, control circuitry, power supplies, casings and other components sufficient to put a product into the hands of a consumer.”

(6) Mr Hopps disagreed with aspects of Mr Wensley’s evidence. He did not accept Mr Wensley’s approach of a skilled person within a team. [33] That is, at the end of the day, a matter for me, but (as I have described) I have reached the same conclusion as Mr Hopps. Mr Hopps also did not accept that the team would be led by this person: [34] and, for reasons I have given, I agree that this is not an approach that assists.

(7) Mr Hopps emphasised the skills of the other team members - and I am happy to accept his evidence on this, and will refer to those skills as necessary - but disagreed with the level of expertise of the product engineer described by Mr Wensley: [35]

“I agree that such a multidisciplinary team would include people with expertise in the physical sciences, such as physics, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering or a closely related subject, but in my experience such individuals would not have “at least 10 to 15 years of experience developing high-volume small consumer devices incorporating heaters", including from a wide range of fields outside [heat, not burn], including medical, kitchen and outdoor products. Certainly no-one on the team at JTI working on [heat, not burn] products at the Priority Date had anything like the extensive heater experience to which Mr Wensley refers.”

(8) On this point, I prefer the evidence of Mr Wensley. Constructing a heat, not burn device requires (amongst other things) engineering expertise, and I am satisfied that the product engineer described by Mr Wensley would be part of this team in this case. I am also satisfied that such a person would have a general engineering expertise, and not a tobacco industry specific one. [36] I consider that the skilled team would have, as an element of its expertise, someone with a knowledge of the engineering aspects of heating and insulation generally. The fact is that heat, not burn products involve seeking to deploy technology from other fields to enable development of products intended to replace (and not develop) combustible cigarettes. Almost by definition, in terms of engineering, one will have to seek a person skilled in the art of applying heat from outside the tobacco industry.

58. It follows that, whilst I consider that both Mr Hopps and Mr Wensley would have a deserved place in any skilled team put together by a tobacco company for these purposes, it is Mr Wensley who had the greater relevant expertise in terms of this particular member of the team. However, as Mr Wensley himself accepted, his knowledge and certainly his inventiveness (Mr Wensley had a number of patents to his name) means that I must approach his evidence with a degree of caution, because it may go beyond what knowledge the skilled person would actually have. I stress that I say this with no disrespect to Mr Wensley, nor to the evidence that he gave. Mr Wensley did his best to “dial-back” his knowledge and originality - but, at the end of the day, these are matters to which I must apply a critical eye.

59. I consider this to be a case where a skilled team is the prism through which questions of common general knowledge, etc, must be understood. I shall refer to the Skilled Team as such. I should, however, make clear that - because of the pre-eminence of the product engineer in relation to the questions that arise, when I refer to the Skilled Team, I will generally be considering the product engineer within that team. Where the knowledge of some other member of the Skilled Team is relevant (for instance, the tobacco chemist) I endeavour to say so expressly.

E. LACK OF INVENTIVE STEP OR OBVIOUSNESS: LAW AND APPROACH

(1) Introduction

60. What is obvious - and what is not obvious - is not a matter than can be further deconstructed or defined. The word “obvious” means what it says. [37] The question of obviousness is approached in the following way. In light of the common general knowledge of the person skilled in the art, and the pleaded prior art, and having construed the inventive concept of the claim in question:

(1) What, if any, differences exist between the matter cited as forming part of the "state of the art" and the inventive concept of the claim?

(2) Viewed without knowledge of the alleged invention as claimed, do these differences constitute steps which would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art (i.e., the Skilled Team) or do they require any degree of invention?

61. Unless the prior art can properly be seen as part of a mosaic, each piece of prior art must be considered separately, to see if the invention claimed by the patent is actually inventive or whether it is, in light of the prior art, obvious.

(2) British American’s case

62. As regards all of the Patents, British American’s case on obviousness was as follows: [38]

(1) The alleged technical contribution comprised the bringing together of two features into an electrically heated smoking system, namely:

(a) At least one heater comprising one or more electrically conductive tracks on an electrically insulating substrate; and

(b) A thermally insulating material for insulating the at least one heater wherein the thermally insulating material comprises a metal.

British American referred to these two features as Feature A and Feature B, which is terminology that I shall adopt.

(2) Feature A was disclosed in Deevi. Feature B was disclosed in Monsees.

63. British American contended that these two aspects or features - Feature A and Feature B - were distinct:

“iv. There is no interaction between Feature A and Feature B within the electrically heated smoking system of [the 484 Patent]. Each of Feature A and Feature B performs its own proper function independently of the other. There is no synergy between them.

v. Accordingly, in assessing the question of inventive step, it is legitimate to consider separately whether an electrically heated smoking system with Feature A or Feature B would have been obvious to the skilled person at the priority date. In light of the prior art, the Claimant will say that the person skilled in the art would have considered the combination of Feature A and Feature B in the electrically heated smoking system of the claims to be no more than a collocation of known features and therefore obvious at the priority date.”

In short, British American contended that this was a case of collocation.

64. It will, accordingly, be necessary to consider the question of whether, as British American contended, Feature A and Feature B are aspects of the same (alleged) invention or separate (alleged) inventions.

(3) General points regarding obviousness

(a) Introduction

65. In the course of their submissions, and notwithstanding the fact that obviousness is a matter not particularly susceptible of further deconstruction, a number of points emerged on the question of obviousness, which I consider more specifically in the following paragraphs and sections. These points were as follows:

(1) The “patent bargain” that underlies the grant of a monopoly by way of a patent, and the control of the monopoly to avoid excessive anti-competitive effects. This is considered further in Section E(3)(b) below.

(2) The correct approach to the question of obviousness, and the factors that might be relevant to such a consideration. This is considered further in Section E(3)(c) below.

(3) The significance of collocation in terms of the Patents and - in particular - in relation to the prior art pleaded by British American (that is, Deevi and Monsees). This is considered further in Section E(3)(d) below.

(4) The significance of the dates for the prior art relied upon by British American and its interrelationship with the common general knowledge also relied upon by British American. This is considered further in Section E(3)(e) below.

(5) The significance, in the context of obviousness, of the use by Philip Morris of divisional patents. This is considered further in Section E(3)(f) below.

(b) The patent bargain

66. What is obvious is, rightly, coloured by the conflicting interests that arise where a monopoly is created. Monopolies are, as a general proposition, anti-competitive and so must be justified. The point was put very clearly by Arnold LJ in E Mishan & Sons v. Hozelock: [39]

“There is a good deal of scholarly literature on the justifications for the patent system. In simple terms, however, the patent system aims to incentivise technical innovation and investment in and disclosure of such innovation, by conferring limited monopolies. Monopolies are generally contrary to the public interest, however, because they prevent competition. Patent law contains a number of mechanisms which are designed to strike a balance between these conflicting considerations. Amongst these mechanisms are the requirements of novelty and inventive step (i.e., non-obviousness): in order not to fetter competition unduly, the public is deemed to have the right to do anything which is disclosed by, or obvious in the light of, any item of prior art, no matter how obscure, which was made available to the public anywhere in the world before the relevant date, without infringing a patent. For that reason, when attacking the validity of a patent, the party doing so is allowed to select the prior art used as the foundation for the argument with 20/20 hindsight. To that extent (but only to that extent), hindsight is not merely permitted, but an inherent feature of the current design of the European patent system (and, indeed, of most patent systems worldwide). It inevitably follows that some patents turn out to be invalid because, unbeknownst to the inventor, or indeed other persons skilled in the relevant art, prior art emerges when sufficient searches are carried out which anticipates or renders obvious the claimed invention.”

67. It is clear from this - and trite in any event - that the inventive step (i.e., non-obviousness) is a requirement that relates to technical obviousness, not commercial obviousness. [40]

(c) Approaches to obviousness

68. A common approach to the question of obviousness is to approach the matter through the Pozzoli stages of inquiry, which may be described as follows: [41]

(1) Identify the notional “person skilled in the art” and identify the relevant common general knowledge of that person. I have already considered the former question, and my conclusions as to the skilled team are set out in Section C above. I will come to the question of common general knowledge of this team in due course, as I will with the other Pozzoli stages described below.

(2) Identify the inventive concept of the claim in question or, if that cannot readily be done, construe it.

(3) Identify what, if any, differences exist between the matter cited as forming part of the “state of the art” and the inventive concept of the claim or the claim as construed.

(4) Viewed without any knowledge of the alleged invention as claimed, do those differences constitute steps which would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art or do they require any degree of invention?

69. The Pozzoli stages culminate in what is the statutory test of obviousness, and the first three questions are a means of disciplining the court's approach to that statutory fourth question. [42]

70. I shall approach the question of obviousness structured in this way. I shall also bear in mind the EPO’s problem/solution approach. The problem/solution approach involves:

(1) Determining the closest prior art;

(2) Establishing the objective technical problem to be solved; and

(3) Considering whether the claimed invention would have been obvious starting from the closest prior art and given the objective technical problem.

71. Neither approach can be applied in a literalist or mechanistic way. Obviousness involves a multifactorial assessment. Without in any way seeking to list all of the factors that the court may take into account, or even set out a limited number of particularly relevant factors fully, the following may be relevant to take into consideration:

(1) Whether something was obvious to try, in circumstances where the success of the trial was not guaranteed. [43]

(2) Hindsight and ex post facto analysis is to be avoided when considering what is, and what is not, obvious. [44] Lord Russell, in Non-Drip Measure Co Ltd v. Strangers Ltd put the point thus: [45]

“Whether there has or has not been an inventive step in constructing a device for giving effect to an idea which when given effect to seems a simple idea which ought to or might have occurred to anyone, is often a matter of dispute. More especially is this the case when many integers of the new device are already known. Nothing is easier than to say, after the event, that the thing was obvious and involved no invention. The words of Moulton LJ in British Westinghouse v. Braulik may well be called to mind in this connection: “I confess” (he said) "that I view with suspicion arguments to the effect that a new combination, bringing with it new and important consequences in the shape of practical machines, is not an invention, because, when it has once been established, it is easy to show how it might be arrived at by starting from something known, and taking a series of apparently easy steps. This ex post facto analysis is unfair to the inventors and, in my opinion, it is not to be countenanced by English patent law…””

(3) The age of the cited art and the question “why was it not done before”? [46] As Terrell notes, [47] “[t]he age of a piece of prior art may have a bearing on the issue of obviousness, though the weight to be attached to such consideration will depend on the circumstances. Where a piece of prior art was only available shortly before the priority date of the invention, then this may of itself explain why it had not already been taken up and modified by others; even obvious developments do not happen overnight. On the other hand, if sufficient opportunity to make a worthwhile invention had been available to others, then this raises the question: "why was it not done before?”” I shall, of course, be considering obviousness specifically in the context of the Patents’ claims, the common general knowledge and the pleaded prior art in due course. It is, however, worth noting at this stage that this factor was one on which Philip Morris placed particular weight, given the very early date of Deevi (1994). Thus, by way of example, paragraph 11 of Philip Morris’ written closing submissions states:

“This is a case where the secondary indicia of obviousness, (1) "what was done by others at the time?" and (2) the question of “why was it not done before if it was all in the [common general knowledge] anyway?” are particularly valuable. This is not a field in which an obvious development might be overlooked, for a lack of interest in the technology. The world's largest tobacco companies have been engaged in [heat, not burn] product development for decades. In the present case, the prior art is effectively ignored in the analysis.”

(d) Collocation

72. It is clear from British American’s plea of obviousness, set out in paragraphs 62 to 64 above, that it is British American’s case that Feature A and Feature B are distinct, and do not comprise aspects of the same invention. In short, the plea of obviousness contains within it a plea of collocation.

73. In Sabaf SPA v. MFI Furniture Centres Ltd, [48] Lord Hoffmann said:

“[24] …there is no law of collocation in the sense of a qualification of, or gloss upon, or exception to, the test for obviousness stated in section 3 of the Act. But before you can apply section 3 and ask whether the invention involves an inventive step, you first have to decide what the invention is. In particular, you have to decide whether you are dealing with one invention or two or more inventions. Two inventions do not become one invention because they are included in the same hardware. A compact motor car may contain many inventions, each operating independently of each other but all designed to contribute to the overall goal of having a compact car. That does not make the car a single invention.

[25] Section 14(5)(d) of the Act provides (following Article 82 of the EPC) that a claim shall “relate to one invention or to a group of inventions which are so linked as to form a single inventive concept”. Although this is a procedural requirement with which an application must comply, it does suggest that the references in the Act to an "invention" (as in section 3) are to the expression of a single inventive concept and not to a collocation of separate inventions.

[26] The EPO guidelines say that “the invention claimed must normally be considered as a whole". But equally, one must not try to consider as a whole what are in fact two separate inventions. What the Guidelines do is to state the principle upon which you decide whether you are dealing with a single invention or not. If the two integers interact upon each other, if there is synergy between them, they constitute a single invention having a combined effect and one applies section 3 to the idea of combining them. If each integer "performs its own proper function independently of any of the others", then each is for the purposes of section 3 a separate invention and it has to be applied to each one separately. That, in my opinion, is what Laddie J meant by the law of collocation.”

74. A good example of collocation arose in Williams v. Nye & Co. [49] In that case, Williams took out a patent for an improved mincing machine which was, in effect, a combination of a mincing machine and a filling machine, both of which were old technology. He brought an action for infringement against Nye & Co, who disputed the validity of the patent on the ground that the alleged invention consisted simply in joining two well-known machines, and was not in itself an invention. Cotton LJ said this: [50]

“Then in Nye's patent, when the cutting operation is entirely completed, there is simply a screw, which does nothing whatever except to force the meat forward, when cut, and is entirely separated from the cutting or mincing operation - for the same purpose as the screw which is used by the Plaintiff in his machine. In my opinion there is no invention in that. There is no difficulty said to have been experienced in continuing the shaft of this screw, and putting on the further side, that is to say, on the side furthest from the knives, that screw which is continued in Nye's patent without any actual break or division or any diaphragm existing, but still continued after the cutting and mincing process had been entirely at an end. If there had been any difficulty overcome by the Plaintiff in putting this continuation of the shaft so as to continue the screw, not for the purpose of being useful towards the cutting, but for the purpose only of being used for forcing the minced meat into the sausage skin, then the matter would stand, to my mind, on an entirely different footing. But here, as there is no difficulty at all said to have been overcome by the Plaintiff in putting the continuation of this shaft with a screw upon it after the cutting process had been performed, and therefore necessarily on the further side of the diaphragm with these holes, in my opinion, although this is a new machine –that is to say, a machine in the sense that it had never been seen in its actual form by the public at the time when the Plaintiff produced it - it is not new in the sense of being a substantial exercise of invention. Therefore, in my opinion, it is not a proper subject matter of a patent. It is difficult to express in words with preciseness what is meant by ingenuity and what is meant by invention ; but I express my opinion that in order to maintain a patent there must be a substantial exercise of the inventive power or inventive faculty. Sometimes very slight alterations will produce very important results, and there may be in those very slight alterations of very great ingenuity exercised and shown to be exercised by the Patentee. That is my opinion.”

Lindley LJ was of the same view: [51]

“Therefore what has the Plaintiff done? He has simply taken, so far as I can see, Gilbert and Nye's invention, and has substituted Donald's cutter for Gilbert's cutter. That is the whole of what he has done. I do not think a patent can be granted for that considering that the object was perfectly well known; that the utility of the forcing nozzle was known; that the object of it had been attained before, and there is nothing which amounts to what is understood to be an invention.”

75. There can be many permutations: the combination of two non-inventions may be inventive; or an invention may be inventively combined with a non-invention; or there may be a single, non-divisible, invention. As Lord Hoffmann said in Sabaf, you have to decide what the invention is. This is reflected in the EPO Guidelines: [52]

“The invention claimed must normally be considered as a whole. When a claim consists of a “combination of features”, it is not correct to argue that the separate features of the combination taken by themselves are known or obvious and that “therefore” the whole subject-matter claimed is obvious. However, where the claim is merely an “aggregation or juxtaposition of features” and not a true combination, it is enough to show that the individual features are obvious to prove that the aggregation of features does not involve an inventive step (see G-VII, 5.2, last paragraph). A set of technical features is regarded as a combination of features if the functional interaction between the features achieves a combined technical effect which is different from, e.g. greater than, the sum of the technical effects of the individual features. In other words, the interactions of the individual features must produce a synergistic effect. If no such synergistic effect exists, there is no more than a mere aggregation of features…”

76. The success or otherwise of British American’s plea of collocation rather fundamentally affects the question of obviousness. If that plea were to succeed - a point that is considered in Section I below - then Feature A and Feature B would have to be considered separately, and the question of obviousness considered separately in relation to each Feature. In particular - as British American’s pleading makes clear - if this is a case of collocation, then:

(1) Deevi is relevant only to Feature A, and is not relied upon by British American in relation to Feature B.

(2) The converse is the case as regards Monsees, which is relevant only to Feature B and is not relied upon by British American in relation to Feature A.

77. The question of collocation is thus important in terms of the focus of the question of obviousness, and is considered, as I say, in Section I below.

(e) Prior art and its inter-relationship with common general knowledge in this case

78. In Philip Morris’ written closing submissions, considerable stress was placed by Philip Morris on what was said to be British American’s lack of reliance on its pleaded prior art. Thus, Philip Morris’ written closing submissions say this about the prior art (Deevi and Monsees) relied upon by British American:

“12. In reality, both pieces of prior art were used simply as hooks to run a case that it was all obvious over what was commonly known. We discuss the problems with this approach below. However, it is important from the outset for the Court to be very clear as to why pleaded starting points are required in the assessment of obviousness. Without a specific starting point for an obviousness attack it is easy to make things look obvious in hindsight, when they were anything but obvious at the time.

13. Floyd J (as he then was) explained that starting from the [common general knowledge] is often favoured by parties attacking a patent because "the starting point is not obviously encumbered with inconvenient details of the kind found in documentary disclosures, such as misleading directions or distracting context". Accordingly, where a party wishes to advance a case of obviousness on the [common general knowledge] alone, they have to plead a starting point in the [common general knowledge]. That was not done in the present case. Plainly, the only real [common general knowledge] starting point in the present case would have been Accord. That would have been hopeless.