Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Intellectual Property Enterprise Court

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Intellectual Property Enterprise Court >> KF Global Brands Ltd v Lead Wear Ltd & Ors [2023] EWHC 1303 (IPEC) (02 June 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/IPEC/2023/1303.html

Cite as: [2023] EWHC 1303 (IPEC)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2023] EWHC 1303 (IPEC)

Case No: IP-2022-000020

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

Intellectual property enterprise court

The Rolls Building

7 Rolls Buildings

London, EC4A 1NL

Date: 2 June 2023

Before:

RECORDER DOUGLAS CAMPBELL KC

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between:

|

|

kf global brands limited |

Claimant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

(1) lead wear limited (2) kamrul hassAn (3) mohammed abdul kader |

Defendants |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Mr Ian Silcock (instructed by Birkett Long LLP) appeared on behalf of the Claimant

Mr Joshua Marshall (instructed by E1 Solicitors Limited on behalf of the First and Third Defendants, and by Law Valley Limited on behalf of the Second Defendant) appeared for the Defendants

Hearing dates: 20-21 April 2023

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

approved Judgment

This judgment was handed down remotely at 10.30am on Friday 2 June 2023 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by email and release to the National Archives.

RECORDER DOUGLAS CAMPBELL KC:

Introduction

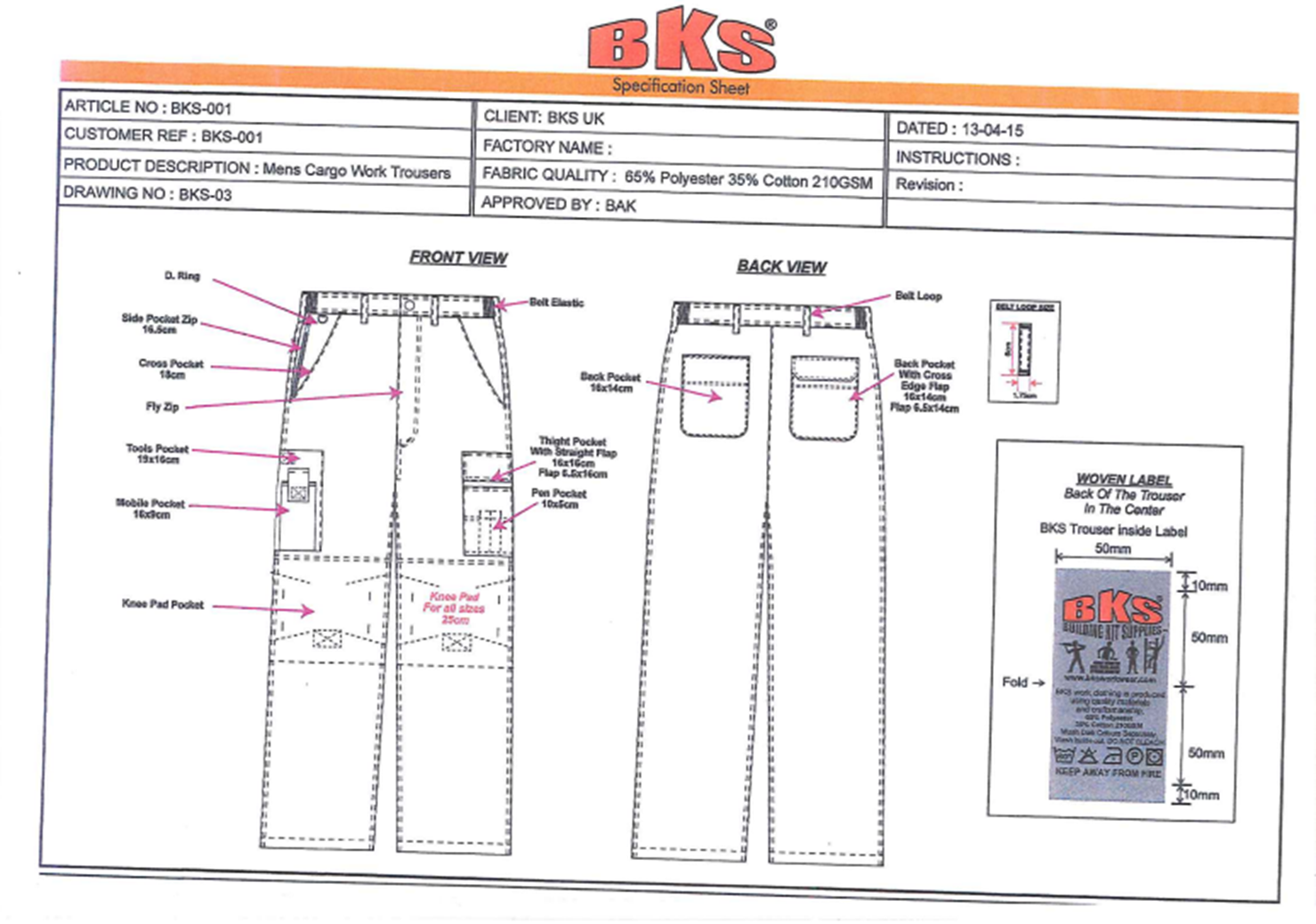

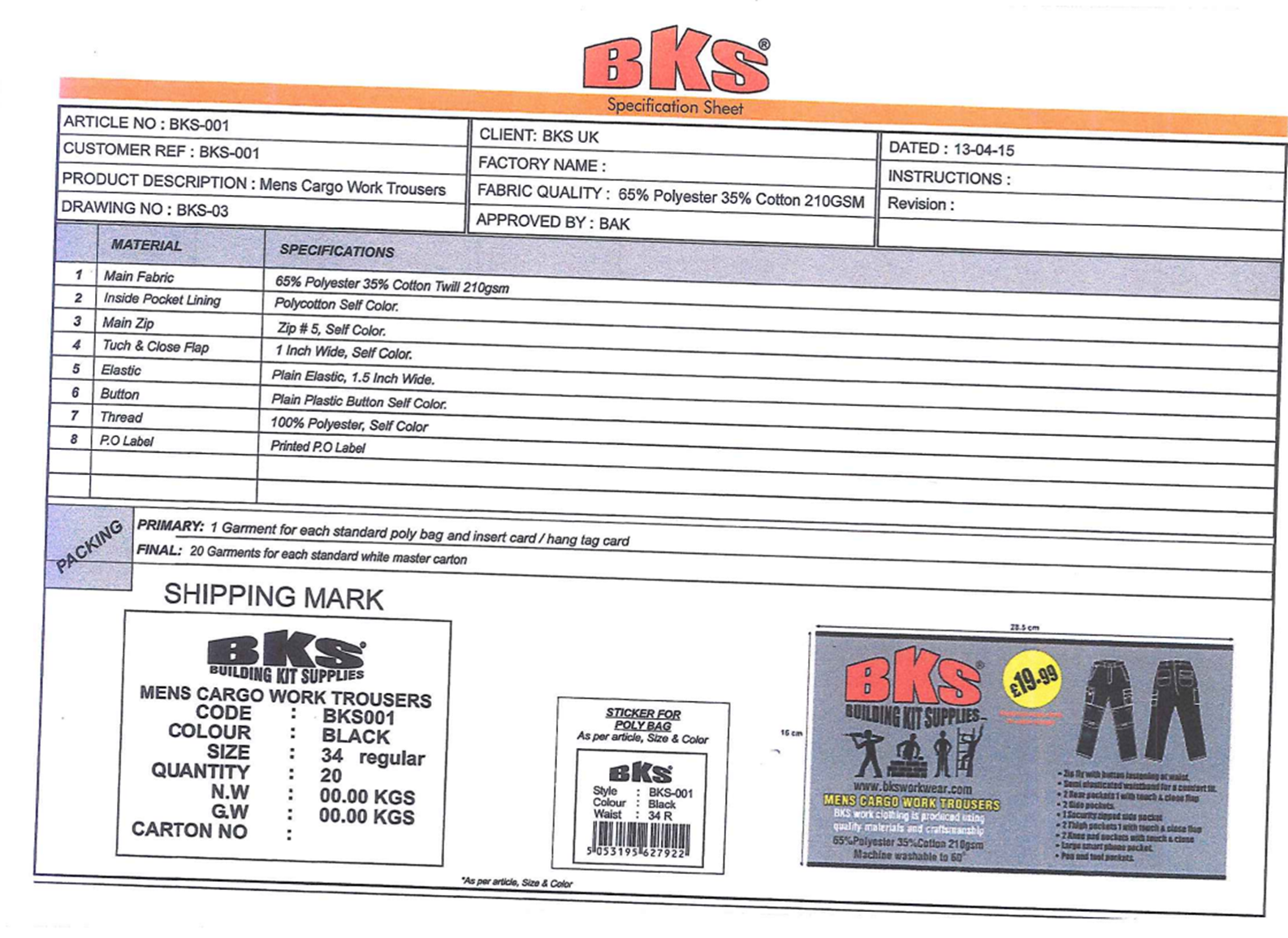

1. This is an action for infringement of the UK unregistered design right (“UKUDR”) which is alleged to subsist in the design of the Claimant’s BKS-001 cargo trousers. The term “cargo trousers” was used during the trial to mean a type of work trousers featuring a large number of pockets. The only design document relied upon is shown at Annex 1.

2. The case management conference was heard before HHJ Hacon on 21 October 2022 and identified 8 issues for trial. However as so often happens in this Court, by the time of the trial the list of issues had narrowed somewhat. Before me the live issues were as follows:

1) Subsistence. At the time of its alleged creation, was the Claimant’s design original?

2) Primary infringement, within s 226 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (“the Act”).

3) Secondary infringement, within s 227 of the Act.

4) If liability is established, should additional damages be awarded pursuant to s 229(3) of the Act?

3. This meant that I did not need to consider issues as to ownership of any design right, nor as to joint liability of the Third Defendant for acts done by the First Defendant. As regards the latter it was accepted that if the First Defendant was liable for any such acts, the Third Defendant was jointly liable in respect thereof.

4. There were 3 different versions of the alleged infringing products, which were referred to as the First, Second, and Third Samples respectively. They were made for the Defendants in Bangladesh by a company called (somewhat incongruously) S&S Swimwear.

5. Most of the argument on infringement focussed on the First Sample, which was purchased before sending the letter before action. I attach the Claimant’s markup of some photographs of that sample at Annex 2. The Third Sample is essentially the same as the First Sample, save that a particular label known as the “OEKO-TEX” label has been removed. Little time was spent on the Third Sample.

6. The Second Sample was purchased after sending that letter, but before issuing proceedings. I attach the Claimant’s markup of some photographs of that at Annex 3.

The witnesses

7. I heard evidence from three witnesses. Mr Balal Ahmad Khan is (with his brother Shoaib Khan) a director of the Claimant. He gave evidence about the creation of the BKS-001 design. Mr Mohammed Abdul Kader is the Third Defendant and also the sole director and shareholder of the First Defendant. He gave evidence about the creation of the First Defendant’s cargo trousers which were alleged to infringe. Mr Kamrul Hassan is the Second Defendant. He purchased 500 pairs of the First Defendant’s cargo trousers and sold them via his own eBay page.

8. Both sides’ counsel were to some extent successful in discrediting the evidence of the other side, as I shall explain in more detail below.

9. I will now deal with each of the issues in turn.

Subsistence

Legal context

10. A design will only qualify for UKUDR protection under s 213 of the Act if it is “original” in two distinct senses.

1) The first is set out in s 213(1). This refers to “original” in the copyright sense, meaning originating with the author rather than being copied by the author from another: see Arnold J (as he then was) in Whitby Specialist Vehicles Ltd v Yorkshire Specialist Vehicles and Others [2016] FSR 5 at [43].

2) The second sense is set out in s 213(4). This provides that a design is not original if it is “commonplace” in the design field in question at the time of its creation. This was also considered by HHJ Hacon in Action Storage at [37].

11. The main point taken by the Defendants in this case concerned originality in the copyright sense. It is well established that the bar is a low one, and “anything in the creation of the design requiring more than slavish copying will result in that design being original”: see HHJ Hacon in Action Storage Systems v G-Force Europe.com Ltd [2017] FSR 18 at [19].

12. However whilst a small change to an existing design for part of an article may well create an existing design right for that part, it does not automatically create a fresh design right in the design of the whole article. This point arose in each of Raft Ltd v Freestyle of New Haven [2016] EWHC 1711 (IPEC), HHJ Hacon; Neptune (Europe) v DeVol Kitchens [2018] FSR 3, Henry Carr J; and Shnuggle Ltd v Munchkin Inc [2020] FSR 22, HHJ Melissa Clarke. Of these, Neptune (which cites Raft) is probably the clearest example of the principle in operation.

13. Neptune concerned various glazed cabinets, one of which (“Design 12”) featured a straight top to the glazing. It looked like this:

However, it was accepted during the trial that Design 12 was a modification to an earlier design which had arched, as opposed to straight, tops to the glazing but which was otherwise the same design.

14. Henry Carr J held as follows:

132 DeVOL submits that, whatever may be the position in copyright law, where a design is produced by making changes to an existing design, the question arises whether a new design right subsists in the new design, or only in those parts of the design that have been changed; Ultraframe v Eurocell [2005] R.P.C. 7 at [129]–[131]; Raft v Freestyle [2016] EWHC 1711 (IPEC) in which changes to an existing design which were “minor and localised” did not give rise to “a new originality” in the design as a whole.

133 I accept DeVOL’s submission on this issue. UK unregistered design right, in contrast to copyright, has a relatively short duration. Protection lasts for a maximum of 15 years from the end of the calendar year in which the design was first recorded in a design document or an article was first made to the design, whichever occurred first. If articles made to the design are put on sale within the first five years from the end of that calendar year, then the design right lasts for only 10 years from the end of the calendar year of first sale. During the last five years of the term of design right licences of right are available. It is important to prevent “evergreening” of such design rights, where small changes are allowed to prolong the duration of the right beyond that fixed by the legislation. Where changes are relatively minor, no new design right will arise in the design as a whole.

134 Applying this analysis to Design 12, the modification from arched tops to straight tops in the glazing did not give rise to any new design right in the design as a whole. It was necessary for Neptune to rely upon the earlier design with arched tops, and the date of commencement of protection was the year in which articles made in accordance with the earlier design were first put on sale.

15. Thus where a new design is produced by making changes to an existing design, it is for the Court to decide whether the changes are relatively minor. If so then no new design right will arise in the new design as a whole but merely in those parts which have changed. It might still be open to the creator of the minor design changes to rely on the design right in the existing design, but only if he or she happens to own that design right too.

16. In the end little was said about “commonplace” beyond the point (also made in Neptune, at [60]) that it provides a useful crosscheck on the breadth of a claim to infringement.

Analysis

17. The Claimant relied on the combination of 12 features pleaded at paragraph 6.2 of the Re-Amended Particulars of Claim. I will not set them all out here, but essentially these are the features highlighted in the relevant drawings shown in the Annexes.

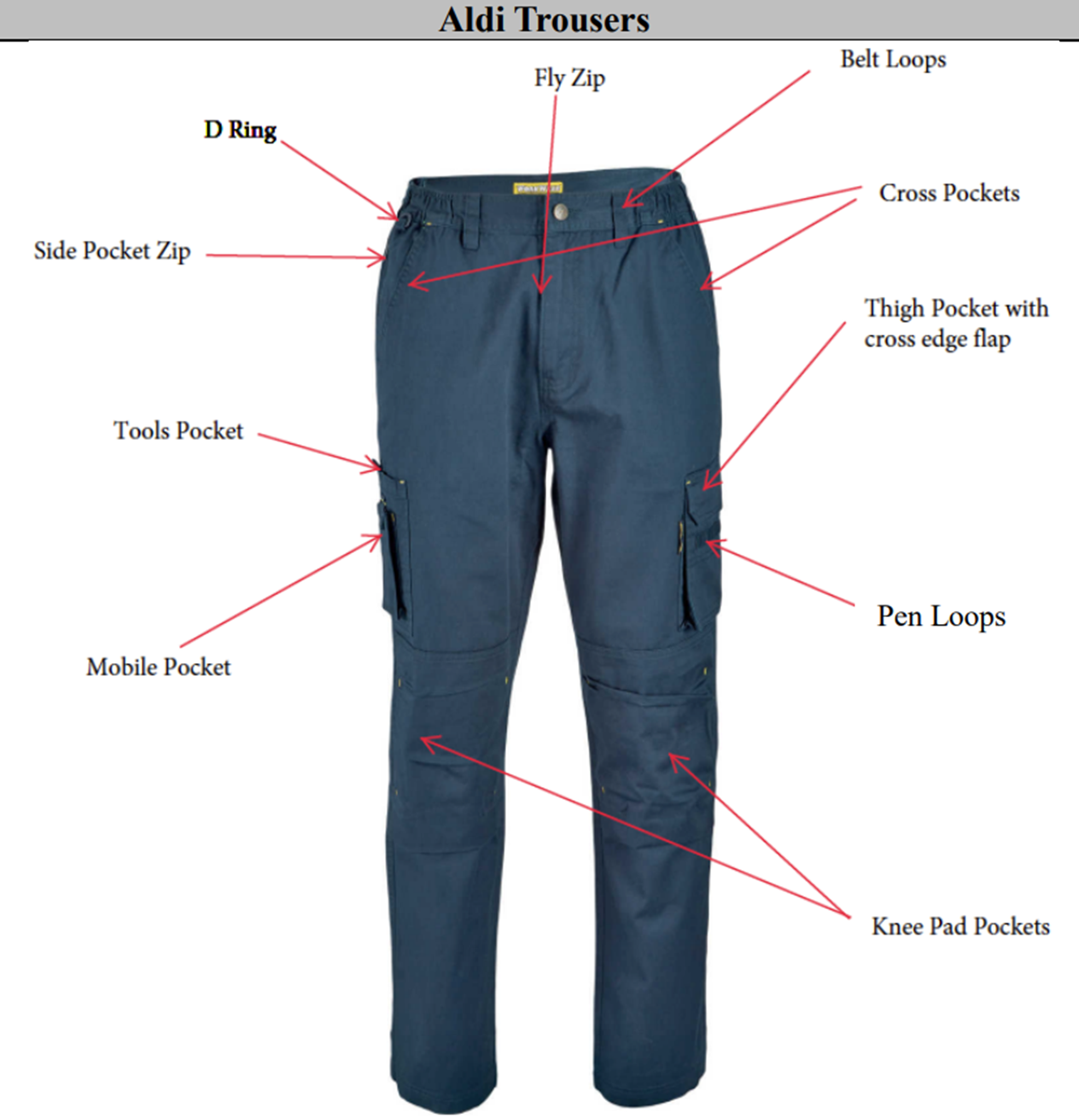

18. The Defendants’ pleaded case was that the BKS-001 design as shown in Annex 1 was (a) copied from an earlier design known as the Aldi design, annotated images of which are attached at Annex 4, and was (b) commonplace at the time of its alleged creation having regard to both the Aldi design and also a number of items of prior art. However, all of their submissions at trial were directed to point (a) and I was not addressed on any of the remaining prior art. The topic of originality over the Aldi design was explored in detail with Mr Khan during his cross-examination, as follows.

19. Mr Khan said that he (Mr Khan) dictated the design to a Mr Naeem Ali of Ali Textiles, who created the actual drawing when they were both present in Mr Khan’s offices in the UK. Mr Khan said that copies of the drawing would have been sent by Ali Textiles by emails or WhatsApps in April 2015 but that he could not find any of those. He had instead found the drawing which was used for the case on a USB stick.

20. Mr Khan agreed that the BKS-001 design was originally sold in cotton and that the fabric did not change to a 65/35 polyester cotton mix until a few months after the trousers were first offered for sale. He could not give any satisfactory explanation as to why the drawing which was dated 13 April 2015 referred to a 65/35 polyester cotton mix.

21. Mr Khan was shown various contemporary disclosure materials, including an email from the Claimant’s factory asking the Claimant to approve a “bend card” to be applied to the Claimant’s trousers. This bend card did not have a domain name on it, but the bend card shown on page 2 in the BKS-001 drawing did. Mr Khan was unable to explain why there was this difference.

22. Mr Khan was asked about the relationship between his design and the Aldi trousers design, which he denied copying. Mr Khan said that his father bought a sample of the Aldi trousers for £8.99 while members of Ali Textiles were visiting him in London, and that he (Mr Khan) showed those trousers to Ali Textiles in his offices. Thereafter Mr Khan’s evidence became more confused.

A) Mr Khan did agree that the Aldi trousers were physically in his office at the same time that he was dictating the design of his trousers to Mr Ali. However his evidence about whether the Aldi trousers were in front of Mr Ali (which would have been logical) kept changing as his cross examination continued.

B) Mr Khan said that Mr Ali did not take the Aldi trousers back to Pakistan “because they had no luggage space”. However the trousers are not bulky items.

C) Instead, Mr Khan cut 5 or 6 material samples out of the Aldi trousers so that the samples could be sent to “a lab in Pakistan” for analysis. It is not clear to me why the nature of the material (cheap cotton) was such that a laboratory was needed, nor was I shown any laboratory results.

D) Mr Khan could not explain why his brother had sent an email to Ali Textiles on 30 January 2015 (and copied to Mr Khan himself) saying “Please can you complete the sample you have of the navy blue Aldi trousers and send it to us to confirm”. Mr Khan instead suggested that the reference to Aldi was a “code”, and that “the sample” meant the 5 or 6 material samples which he had cut out for the laboratory analysis rather than any sample trousers. If so then the email is oddly worded.

E) Nor could Mr Khan explain his own email to Ali Textiles dated 9 March 2015 saying “You need to make the drawings for the trousers to go on the packing card like the Aldi ones”. There was a similar email from Mr Khan dated 1 April 2015 saying “Can you please draw a white outline on the trousers, like the Aldi trouser card”. On Mr Khan’s original story, Ali Textiles had never seen the Aldi trousers but his emails assume that they knew what the Aldi packing card (ie bend card) looked like. Mr Khan’s evidence about whether Ali Textiles had seen the Aldi packing card when in Mr Khan’s offices was again confused.

23. I did not believe Mr Khan’s evidence on this. I find that he not only showed Mr Ali the sample Aldi trousers but he gave them to Mr Ali to take back to Pakistan. I find that this was all done so that Mr Khan could produce a competing product at the same or a similar price.

24. Mr Khan was then shown an email from Ali Textiles to himself dated 1 April 2015 enclosing the BKS trousers bend card, plus a photograph of the BKS trousers. It was put to him that the BKS trousers shown therein were the same as the Aldi trousers, save that the pen loops had been replaced with a pen pocket (and there was also an immaterial change to belt loops on the back, which I will ignore). Mr Khan denied this but the materials speak for themselves and I found his denials unconvincing.

25. Finally Mr Khan was shown a photograph of the trousers the Claimant was selling on eBay on 25 April 2016, obtained using a Wayback Machine internet search. The only difference between the Claimant’s trousers and the Aldi trousers was again that the pen loops had been replaced with a pen pocket. Mr Khan’s attempt to explain this away was again confused.

26. I reject the Claimant’s case that the BKS-001 design document accurately depicts the design of the Claimant’s trousers as at April 2015. I find that the only material difference between the Aldi design and the BKS-001 design as at April 2015 (which was sometimes called “the Claimant’s bend card design” during the trial) was the change from pen loops to a pen pocket. Otherwise the BKS-001 design as at April 2015 was a copy of the Aldi design.

27. Furthermore this difference is so minor that it does not create a new design right in the BKS-001 design as a whole, and the Claimant only relies on that design as a whole. The Claimant did not rely on any design right in the pen pocket itself. I presume this is for the good reason that it thought any case relying on the pen pocket alone would fail, but the reasons do not matter. It follows that the BKS-001 design as at April 2015, ie the only design relied upon, is not original, and the claim must fail.

28. It seems entirely possible to me that there was a second version of the Claimant’s BKS-001 design at some point, most probably some time after 25 April 2016 given the Wayback Machine photograph. This second version may well be the one which is shown in the pleaded BKS-001 design drawing.

29. However no such second version is pleaded and as the Defendants correctly submit, I know nothing about who created it or when, or why the Claimants might own title to design right therein. It is not fair on the Defendants to try and construct a case which is not merely unpleaded, but which is contrary to the case which the Claimant has pleaded. Indeed the Claimant repeatedly doubled down on its case that there was only ever a single version of the BKS-001 design, long after it must have become apparent to the Claimant that such a case was unsustainable. I will disregard any such second version.

30. In case I am wrong, I will go on to consider infringement.

Primary infringement, s 226 of the Act

Legal context

31. Section 226 requires “copying the design so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to that design”: see s 226(2). This is not the same test as in copyright law: see L Woolley Jewellers v A&A Jewellery [2003] FSR 15 at [19], [21]-[22]; Neptune at [52]-[53].

32. Design right is then infringed by anyone who, without the licence of the design right owner “does, or authorises another to do” anything which would amount to infringement: see s 226(3). It was not disputed that the test for “authorising” was the same as in copyright law: see CBS Songs v Amstrad Consumer Electronics [1988] RPC 567, ie the grant or purported grant to do the act complained of.

33. There was a dispute about what sort of acts actually amounted to such authorisation. The parties agreed that simply ordering a pre-existing product did not amount to authorisation to make that product, because that product had already been made. Nor was it disputed that where a party had contributed something to the design of an article it might be liable as authorising the manufacture thereof: see eg Pensher Security Door Co Ltd v Sunderland City Council [2000] RPC 249, CA. The dispute was whether ordering products which did not yet exist, but which were shown in a pre-existing catalogue, amounted to authorising the manufacture of the particular products which were ordered. However because of the next point it is not necessary to resolve this.

34. It was not disputed that primary infringement requires an act to be done in the UK (or alternatively, authorisation to do an act in the UK), where the “UK” includes for this purpose territorial waters and fixed Continental Shelf installations. This is implicit from the nature of the 1988 Act, which is a UK statute, but is in any event made clear from s 228 which defines an infringing article and contains the following provisions:

(2)An article is an infringing article if its making to that design was an infringement of design right in the design.

(3)An article is also an infringing article if—

(a)it has been or is proposed to be imported into the United Kingdom, and

(b)its making to that design in the United Kingdom would have been an infringement of design right in the design or a breach of an exclusive licence agreement relating to the design.

Section 228(2) applies to articles made in the United Kingdom, and s 228(3) applies to articles made elsewhere. See also Russell-Clarke & Howe on Industrial Designs, 10th Edition, at 4-091 to 4-092.

35. In his reply speech in closing Counsel for the Claimant applied to amend the Particulars of Claim to introduce an allegation that “if and to the extent that that acts of primary infringement and/or authorisation complained of herein were carried out in Bangladesh, the same were and are actionable by the Claimant and/or its predecessors in title (and the same are entitled to the same or equivalent remedies and relief) under the laws of Bangladesh as under the laws of England”. I refused that application for reasons I gave at the time: see [2023] EWHC 1047 (IPEC). Essentially this application was extremely late and allowing it would have been unfair to the Defendants.

Analysis

36. The Claimant’s case on infringement had two main limbs. The first was to compare what appear to be its current commercial products (and which may be made to the second version of the BKS-001 design discussed above) with the Defendant’s products. The problem with this is that it is not the right comparison to make. The Claimant should have used its first BKS-001 design for the purposes of comparison.

37. The second was an allegation that the text of the First Defendant’s eBay advertisement for its cargo trousers dated August 12, 2021, and in particular the list of specific features, was copied from a pre-existing listing page of pricedrop247 (a licensee of the Claimant) advertising the Claimant’s work trousers. I agree with the Claimant that this text was copied. There are just too many similarities in the arrangement and order of the words, plus the placing of full stops and capital letters, for these similarities to be due to coincidence.

38. Mr Kader was noticeably reluctant to answer Counsel’s question as to whether he believed these similarities to be coincidence. The substance of the question had to be put a considerable number of times before he finally said “it is probably coincidence”. I found his use of the word “probably” odd. Later, and for no obvious reason, Mr Kader went out of his way to mention a policy on eBay whereby any seller could use anybody’s listings but then went on to say that he had not in fact done that. I found it odd that he specifically wanted to mention this if it was irrelevant to anything he had done.

39. The combination of matters set out above meant that I did not believe Mr Kader’s denials. I find that he copied the text in question. Counsel for the Defendants sought in closing to explain away Mr Kader’s position by taking me to fresh evidence but I must take Mr Kader’s evidence as it was and not as the Defendants would like it to have been.

40. It might be thought that once I have found that Mr Kader copied the text relating to the Claimant’s product, the Claimant must win on infringement of design right. This is wrong for two reasons. First, these are completely different legal and factual issues. Copyright is not even claimed in the relevant text. Secondly, the Claimant has already lost on the issue of originality. If and insofar as Mr Kader ever asked S&S Swimwear to copy a second version of the BKS-001 design (as to which I make no findings, but which was effectively the case put by the Claimant) then such is irrelevant.

41. Furthermore the Claimant also loses on the territoriality point. The Defendants’ products were made by S&S Swimwear in Bangladesh, and the only potential authorisation to do anything was an authorisation to make those products in Bangladesh. Hence it does not matter whether or not the products appeared in a pre-existing S&S Swimwear catalogue (although no such catalogue was ever shown to me) or if they were overruns from products which S&S Swimwear had made for other customers (as Mr Kader said for the first time in his cross-examination).

42. The Defendants made submissions about how if (contrary to their case) the first version of the BKS-001 design was original then none of their trousers were made to that design anyway. It is not necessary to consider these submissions.

43. The upshot is that none of the Defendants’ sample products infringe.

Secondary infringement, s 227 of the Act.

44. Since none of the Defendants’ products are infringing articles the issue of secondary infringement does not arise. Nonetheless the point of “reason to believe” was argued in some detail so I will address it.

Legal context

45. Section 227 provides as follows:

Secondary infringement: importing or dealing with infringing article.

(1)Design right is infringed by a person who, without the licence of the design right owner—

(a)imports into the United Kingdom for commercial purposes, or

(b)has in his possession for commercial purposes, or

(c)sells, lets for hire, or offers or exposes for sale or hire, in the course of a business,

an article which is, and which he knows or has reason to believe is, an infringing article.

46. The effect of these provisions and the application thereof was analysed in Action Storage by HHJ Hacon: see [83]-[87], [103]-[107].

Analysis

47. Given the close involvement of the First and Third Defendants in the creation of the Defendants’ products by S&S Swimwear, if I had concluded that the relevant products were infringing articles I would also have concluded that they both knew (and did not merely have reason to believe) they were such. It would not have been necessary to rely on the letter before action which the Claimant sent to these Defendants as providing such a reason to believe.

48. The Claimant did not suggest that the Second Defendant knew that the products were infringing, which was realistic. The Second Defendant had no involvement with S&S Swimwear at all. Instead the Claimant relies on (a) the price and nature of the goods, and (b) the letter before action sent to the Second Defendant as providing a reason to believe they were infringing.

49. I was not satisfied that there was anything about the price and nature of the goods which gave Mr Hassan reason to believe they were infringing, merely that they were cheap at less than £10.49. There was a suggestion that Mr Hassan should have done a Google search, but I do not see why a failure to do such a search equates to a “reason to believe” that the Defendants’ products were infringing.

50. That leaves the letter before action. In many cases such a letter will be sufficient to fix a Defendant with “reason to believe” for the purposes of s 227, assuming that the relevant goods are in fact infringing. However that is not necessarily so. Sometimes a letter will have so little relevant detail that it will merely put a Defendant on notice that a claim is being made. The letter before action in this case fell into the latter category.

1) All it did was to allege that the Claimant is the owner of “the design right of BKS-001” and to identify the Defendant’s alleged infringing products by reference to a screenshot of the Defendants’ own eBay page.

2) It did not provide any of the Claimant’s BKS-001 design documents nor any particulars of the claim to ownership of any design right therein. Mr Hassan told me that he typed “BKS-001” into Google and he found biker jackets and bikers gloves, but not trousers; and that he could not find “KF Global” as a company on eBay either. He was not challenged on that evidence.

3) Nor did the letter before action include any screenshots or details of the Claimant’s eBay listing page beyond an assertion that this existed.

4) The letter did at least say that the Claimant had been selling its trousers since November 2015, but that statement was false because the Claimant was not incorporated until 2016.

51. In this case, the Claimant did not properly clarify the nature of its claim until after the case management conference. Had it mattered, I would have held that the Second Defendant did not have reason to believe the goods were infringing before then. As it happens, the Second Defendant stopped selling the products complained of shortly after the case management conference in any event.

Additional damages

52. Since there is no infringement this does not arise, and given that it is such a fact-sensitive question there is no point in considering it.

Conclusion

53. The action fails and will be dismissed. I will hear counsel as to the form of order I should make.

Annex 1 - Claimant’s design drawing

Annex 2 - the First Sample

Annex 3 - the Second Sample

Annex 4 - the Aldi trousers

Annex 5

The Claimant’s cargo trousers as shown on eBay on April 25, 2016 (from Wayback Machine)