Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court) Decisions >> SciPharm SarL v Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust [2023] EWHC 569 (Comm) (16 March 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2023/569.html

Cite as: [2023] EWHC 569 (Comm)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2023] EWHC 569 (Comm)

Claim no. LM-2019-000185

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

LONDON CIRCUIT COMMERCIAL COURT (KBD)

Royal Courts of Justice,

Rolls Building

Fetter Lane,

London,

EC4A 1NL

Date: 16 March 2023

Before:

MR ANDREW HOCHHAUSER KC

SITTING AS A DEPUTY JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

SciPharm S.a.r.l |

Claimant |

|

|

- and – |

|

|

|

Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust |

Defendant |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Mr Ali Reza Sinai (instructed by BBS Law incorporating OGR Stock Denton LLP) for the Claimant

Dr Andrew Lomas (instructed by Clifford Chance LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 3 and 5 July 2021 (reading), 6, 7, 8 and 20 July 2021

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

APPROVED JUDGMENT

This judgment was handed down by the judge remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email and release to The National Archives. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 10.30am Thursday 16 March 2023

Table of Contents

The Drug Development Process. 9

The Claimant’s submissions in relation to the ambit of Defendant’s obligations under the DA.. 28

The Claimant’s submission in relation to the Implied Terms. 33

The Defendant’s submissions in relation to the ambit of Defendant’s obligations under the DA.. 34

The Defendant’s submission in relation to the implied term.. 38

Discussion and conclusion in relation to the Defendant’s obligations under the DA.. 39

My findings in relation to the implied terms for which the Claimant contends. 42

The Defendant’s submissions. 51

Losses not incurred by the Claimant 52

Matters alleged to be outside the ambit of the DA.. 53

Other items which fall to be deducted. 53

The Claimant’s submissions. 55

Can the Claimant claim the costs of the Chirogate invoices paid by CompLex?. 56

MR ANDREW HOCHHAUSER KC:

The Claim

1. The Claimant, SciPharm S.a.r.l, a company incorporated under the laws of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, claims damages from the Defendant, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, which at, the material time, as well as owning the renowned eye hospital in London, had a small pharmaceutical manufacturing division, trading as Moorfields Pharmaceuticals, for an alleged breach of a pharmaceutical drug development agreement made on 20 December 2011 (the “DA”), relating to a product called Treprostinil (the “Product”) for the treatment of lung disease. The DA was initially made between the Defendant and an Austrian company by the name of CompLex Vertriebs GmbH (“CompLex”), ultimately owned by the same investors as the Claimant, which transferred its interest therein to the Claimant with effect from 16 November 2012. This was done, with the consent of the Defendant, for the purpose of holding the pharmaceutical drug’s intellectual property rights in Luxembourg. The Claimant was substituted in the DA by novation, although the DA continued in the terms set out in the original document, where the Claimant is referred to as COM, and the Defendant as CMO, an abbreviation for “contract manufacturing organisation”.

2. The principal issues for resolution are:

(1) whether the loss of a good manufacturing practice (“GMP”) licence by the Defendant constituted a breach of the DA; and

(2) if the Defendant was in breach of the DA, what sums (if any) are recoverable by the Claimant as losses flowing from that breach.

3. The detailed issues, approved by the Court, are contained in Annex 1 to the Costs and Case Management Order of Mr Stephen Houseman KC, sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court, dated 4 December 2020, which I will consider in turn below.

4. On 28 January 2020, the Defendant’s application for summary judgment under CPR Part 24 on the grounds that the claim stood no real prospect of success came before HHJ Pelling KC. The application failed. The judgment is reported at [2020] EWHC 269 (Comm).

Representation

5. The Claimant was represented by Mr Ali Reza Sinai of Counsel and the Defendant was represented by Dr Andrew Lomas of Counsel. I am grateful to them for their helpful, detailed written and oral submissions.

Witnesses of fact

The Claimant’s witnesses

6. The following witnesses of fact gave evidence on behalf of the Claimant:

(1) Dr Georg Michael Strieder (“Dr Strieder”), who is now a retired consultant in GMP and regulatory affairs. At the relevant time, he was employed by an Austrian company, Orpha Trade GmbH (“Orpha Trade”) as Director of Technical Business Development. In that capacity, he was instructed by CompLex to act as a consultant on their behalf to locate a manufacturer for the Product, which they wished to develop and to obtain a Marketing Authorisation Licence (“MAL”), from the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (“AGES”). He gave background to the DA. He assisted in relation to GMP compliance and making the marketing authorisation application in Austria (the “MAA”). He gave his evidence in English, which he spoke fluently;

(2) Mr Michael Hendrikus Martinus Beckers (“Mr Beckers”), the Managing Director of the Claimant;

(3) Ms Regina Schuller (“Ms Schuller”), who when giving evidence was the Head of Partnering Development at Orpha Trade, but at the material time she was employed by Amomed Pharma GmbH (“Amomed”), a wholly-owned subsidiary of CompLex, and after the novation of the DA, she assisted the Claimant with the development of the Product, liaising closely with Diapharm GmbH (“Diapharm”), a regulatory consulting company based in Austria and Germany used by the Claimant, which filed the MAA with AGES on 25 February 2014. She had, however, no direct contract with anyone from the Defendant;

(4) Ms Bianca Tan (“Ms Tan”), who when giving evidence was the Head of Treprostinil and Medical Device Development for Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG, but at the material time was employed by CompLex and assisted the Claimant with the development of the Product after the novation of the DA. She had primary responsibility for the clinical trials. She was not, however, involved in the negotiations leading up to the DA. She gave evidence in relation to the parties’ performance under the DA and provided details of how she prepared the Schedule of Loss, which is now in its fourth iteration, earlier versions having been corrected.

7. I formed the view that each of the witnesses was truthful and was doing their best to assist the court. As Dr Lomas fairly stated at paragraph 13 of his written closing submissions: “No criticism of their honesty is made. They answered questions fairly, and generally avoided adopting the role of advocate for the Claimant”. It must be remembered however, the events in question took place many years ago and furthermore much of the evidence related to events after the DA had been entered into and was of no assistance to its construction.

8. I also bear in mind the dicta of Leggatt J (as he then was) in Gestmin SGPS S.A. v Credit Suisse Limited, Credit Suisse Securities (Europe) Limited [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) concerning the reliability of oral evidence based on recollection of events occurring several years ago:

“Whilst everyone knows that memory is fallible, I do not believe that the legal system has sufficiently absorbed the lessons of a century of psychological research into the nature of memory and the unreliability of eyewitness testimony” [15];

“Memory is especially unreliable when it comes to recalling past beliefs. Our memories of past beliefs are revised to make them more consistent with our present beliefs. Studies have also shown that memory is particularly vulnerable to interference and alteration when a person is presented with new information or suggestions about an event in circumstances where his or her memory of it is already weak due to the passage of time” [18];

“Considerable interference with memory is also introduced in civil litigation by the procedure of preparing for trial…The effect of this process is to establish in the mind of the witness the matters recorded in his or her own statement and other written material, whether they be true or false, and to cause the witness's memory of events to be based increasingly on this material and later interpretations of it rather than on the original experience of the events” [20];

“In light of these considerations, the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is, in my view, to place little if any reliance at all on witnesses' recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known probable facts… Above all, it is important to avoid the fallacy of supposing that, because a witness has confidence in his or her recollection and is honest, evidence based on that recollection provides any reliable guide to the truth” [22]

(Emphasis added).

9. I have adopted the approach indicated in paragraph 22 of the Gestmin decision in relation to all the Claimant’s witnesses of fact. Fortunately, in this case a great deal of the relevant evidence consists of the DA, contemporaneous documents, correspondence and emails.

The Defendant’s witness

10. There was only one witness of fact, who gave oral evidence on behalf of the Defendant, Mr Richard Macmillan (“Mr MacMillan”), its General Counsel. He assumed that role on 23 September 2019, some days after the Claim Form in this matter was served. He therefore had no direct knowledge of any of the matters which are the subject matter of this claim. His witness statement consisted of a commentary on the witness statements of Dr Strieder, Ms Tan and Mr Beckers. That commentary consisted principally of submissions by reference to documents. He took instructions from Mr Jonathan Wilson, the Defendant’s Chief Financial Officer, but Mr Wilson also had no personal involvement in this matter at the relevant time. I found his evidence of little assistance in the determination of the issues in this case.

11. There was a potentially significant witness, Ms Margaret Beveridge (“Ms Beveridge”). She was called by neither party, although in closing Mr Sinai accepted that the Claimant could have called her. At the time of the hearing, she was a semi-retired business consultant, living in Kilmarnock, Scotland, where she worked from home. She commenced employment with the Defendant on 18 April 2010 as a Business Development Manager. She remained in that role until she was made redundant in June 2015. She played an important role in relation to the discussions which led to the DA and drafted a 5 year plan on the basis that the Defendant would be the commercial manufacturer of the Product.

12. Although Ms Beveridge made a witness statement dated 29 May 2018, it was not revealed to the Defendant until about May 2021, first in correspondence and then exhibited to the fourth witness statement of Stephen Ian Silverman, a partner in the Claimant’s solicitors, BBS Law incorporating ORG Stock Denton LLP, dated 12 May 2021, in relation to a disclosure application made by the Defendant. In paragraph 15 of that statement, she said that it was standard industry practice for the GMP status to be maintained beyond the production of clinical and stability batches for the licence application and “[the Defendant] knew that a requirement for a successful licence application was the maintenance of GMP status”. By an Order of HHJ Pelling KC dated 30 April 2021, the Claimant was ordered to produce attendance notes of certain aspects of conversations with Ms Beveridge, on the basis that there had been selective waiver of privilege in relation to the same. No notice was served by the Claimant under the Civil Evidence Act 1995 and Ms Beveridge’s evidence was not tested by cross-examination. I therefore attach little weight to it, save insofar as its contents were confirmed by other evidence or admitted by the Defendant.

The Expert Evidence

13. At the Costs and Case Management Conference on 4 December 2020, a single joint expert in the field of pharmaceutical drug development was ordered to produce a report dealing with the issues listed at Annex 2, “identifiable from the face of the pleadings” (the “Annex 2 Issues”) of the Order dated 4 December 2020 of Mr Stephen Houseman KC, sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court (the “CCMC Order”). The Defendant initially opposed the appointment of an expert and objected to the provision of the witness statements or any other documents, save the pleadings.

14. The parties agreed to appoint Dr Michael John Desmond Gamlen FRPharmS, FRSC, BSc, PhD (“Dr Gamlen”) as the single joint expert and a joint Letter of Instruction was produced dated 16 January 2021. He has worked as a pharmaceutical consultant, having previously had a long career in the field of pharmaceutical development and pharmaceutical outsourcing. He has a familiarity with drug development projects, such as the one in this case, and is an experienced expert witness. However, despite being asked to provide an opinion on the issues in Annex 2, he appears to have misunderstood his task, and initially on 16 February 2021, he provided a report which addressed the issues in Annex 1, which contain those issues I have to decide. On 21 February 2021, he produced a report addressing the Annex 2 Issues. Thereafter, as permitted by the CCMC Order, the parties put a series of questions to Dr Gamlen, and he gave oral evidence at the hearing.

15. Under the terms of the CCMC Order, the only documents Dr Gamlen saw before he gave oral evidence were the pleadings and with the agreement of the parties, the DA and the AGES Day 70 Preliminary Assessment Report (the “Day 70 Report”). The result was that, on at least one occasion, when shown other documentation he changed his response. [1] He also had a tendency to determine issues of interpretation which were my province, rather than his. Generally, however, I found his evidence to be helpful and reliable, once he had the benefit of material which enabled him to give an informed answer, although I do accept the point made on behalf of the Defendant that on several occasions Dr Gamlen was asked to opine on broader questions that fell outside the ambit of his instructions.

The Drug Development Process

16. In his judgment on the Part 24 application, at [3] HHJ Pelling KC referred to the “various highly complex steps that have to be taken in order to validate a pharmaceutical product prior it being submitted for manufacture … there is a highly regulated process which leads to validation. It is only if validation is obtained that the developer of the drug can then proceed to manufacture and sell it.”

17. There are two separate aspects of the drug development process:

(1) manufacture of the drug for clinical trials tested on patients who have consented to participate. The data from these trials is used to create the Investigational Medicinal Product (the “IMP”) and the Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (the “IMPD”);

(2) in parallel, validation batches of the drug are produced whereby specific data is collected on the manufacturer’s processes and this information is submitted to the market regulator as part of a MAA. It is intended to demonstrate that the proposed manufacturer named in the application form can consistently reproduce the drug in question under the same manufacturing conditions. The marketing authorisation process is decentralised, and each member state grants its own marketing authorisation number. A detailed application of the validation process under a MAA is described in the Guidance produced by the European Medicines Agency. Of particular importance is the fact that validation is specific to the designated manufacturing site; thus, validation data submitted by the Defendant could only be used for the purposes of validating the Defendant’s manufacturing site and processes.

18. At the heart of this dispute is the ambit of the Defendant’s obligations under the DA. The Defendant contends that, properly construed, it was limited to a simple “fill / finish” agreement to produce 12 clinical study batches, which obligation it discharged. The Claimant’s position is that, on the contrary, there were continuing obligations placed upon the Defendant which it could not fulfil because of the loss of its GMP licence. It contends that the parties were to use the data which the Defendant processed and collected from the initial 12 validation batches, in order to submit those processes for validation in the MAA application, test them for stability and administer the batches (as well as future batches) to conclude the clinical trial dossier. The Defendant was therefore in repudiatory breach of both express and implied terms of the DA.

19. Before turning to the terms of the DA, I should add that it is common ground that, whilst it was clearly envisaged that the Defendant would become the manufacturer of the Product, there was no obligation on the Defendant to do so and no supply agreement was ever entered into between the parties. The Defendant submits that this is fatal to the Claimant’s case because each new manufacturer has to undergo a validation process de novo and any change in formulation, batch size or manufacturing process (even by the same manufacturer) would require validation de novo. It contends that without a supply agreement, there was no contractual obligation on the Defendant to manufacture any further Product, to be the Claimant’s manufacturer or to assist with a MAA or otherwise. The Claimant’s case is that the absence of a supply agreement does not detract from its case, which is founded on alleged repudiatory breaches of the DA alone, which, it says, caused the Claimant substantial loss.

The Background to the DA

20. In about 2011, for reasons which are unclear, the previous manufacturer was unable to continue to manufacture the Product. Consequently CompLex, which was interested in developing it commercially, instructed Orpha Trade to find a new manufacturer for it. As a result, Dr Strieder entered into discussions with Ms Beveridge and Ms Sophia Titus, who was employed by the Claimant as a project manager, to ascertain whether the Defendant would be interested in manufacturing small batches of the Product for CompLex, which was looking for someone to take the third party manufactured active pharmaceutical ingredient (“API”) in order to develop and thereafter manufacture the Product (the “Project”).

21. Dr Strieder’s evidence, which I accept, was that if the application for a MAL was successful, the manufacturer of the Product for the purposes of obtaining the MAL would then become the commercial manufacturer. The discussions with Ms Beveridge proceeded on this basis because she had been recruited as a Business Development Manager to expand into this area. I also accept that, although the Claimant’s initial quotation did not refer to regulatory steps, in the course of discussions, Dr Strieder made it clear that CompLex was interested in instructing a manufacturer to develop the Product for both clinical trials and for validation in relation to the MAA in a range of concentrations and strengths. This was consistent with the desire of both CompLex and the Defendant that the Defendant should become the manufacturer of the Product, following a successful MAL. The manufacture was also intended to include “compassionate use” in situations where a physician had approved use of an unlicensed/unapproved medicine for those patients having a medical need and for which there was no other suitable licensed medicine available.

22. Throughout 2011 discussions between Dr Strieder and Ms Beveridge continued, with the exchange of scope of work proposals and technical submissions to which Ms Titus contributed. Ultimately, on 20 December 2011, the Defendant entered into the DA with CompLex. As stated earlier, on 16 November 2012, the benefit of the DA was transferred from CompLex to the Claimant.

The Development Agreement

23. The DA is a detailed and professionally drafted technical agreement, containing 16 clauses and seven annexes. The following express terms of the DA were relied upon by one or other, or both, parties and are of importance:

(1) By clause 1, the parties recorded the background to the DA. In particular, by clause 1.4 it is recorded that:

“It is the intention of COM to enter into further supply agreements with COM or affiliated companies of COM once the PRODUCT is successfully registered in at least one of the European member states.”

(2) By clause 2.1, a number of terms are defined including (emphasis added):

“DEVELOPMENT under this agreement shall mean all work necessary to fulfil the demands of the Guideline on the Requirements to the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Quality Documentation Concerning Investigational Medicinal Products in Clinical Trials (October 2006) by the EMEA CHMP and the Notice to Applicants, Volume 2B, incorporating the Common Technical Document (CTD Part 3.2.P) [2] (May 2008) by the European Commission except for chapter 3.2.P.2. The approach in the case of the PRODUCT is a transfer of the production process from a former manufacturer. Nevertheless, all measures to ensure a smooth production of three validation batches - including but not limited to filtration studies, stress tests, analytical method transfer - are an integral part of the DEVELOPMENT to be performed by CMO. The general approach to obtain the sterile PRODUCT is a standard approach in parenteral manufacturing.

The services are referring to the quotations.

PRODUCT shall mean the finished medical product as defined and specified in Annex ./1.

DOSSIER means such package of technical, clinical and chemical information as is necessary for, or useful in connection with, developing the PRODUCT (EMEA Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD) and ICH-M4 Common Technical Document - Format) and includes, without limitation, data in support of formulation, analytical methods and stability concerning the PRODUCT in possession of COM and the chemical, pharmaceutical and biological documentation (including any expert report) and any certificate of free sale.”

(3) By clause 3, the subject matter of the DA is set out, including:

a. By clause 3.1 (emphasis added):

“CMO shall develop for COM the PRODUCT as described in Annex ./1 according to the information therefore provided by COM. CMO shall perform the DEVELOPMENT in accordance with the directives given by COM in writing and in accordance to the development plan given to CMO to COM (Annex ./2). The DEVELOPMENT comprises all necessary development steps for the manufacture and the chemical-pharmaceutical part including long-term stability and quality control. Additional subject matters have to be agreed on in writing and signed by both Parties. It is agreed and understood between the Parties that, contingent on the development character of this project, CMO does not assume any responsibility for the successful DEVELOPMENT of the PRODUCT and the regulatory approval of the product.” [3]

b. By clause 3.3:

“CMO shall perform the DEVELOPMENT of the PRODUCT exclusively for COM. The resulting formulation is exclusive as well. If COM fails to achieve market authorisation for the PRODUCT in at least one of the European Union member states within five years after the signature of this agreement the exclusivity shall be terminated.”

(4) By clause 4, various undertakings are given by the Defendant including:

a. By clause 4.1:

“CMO shall perform all DEVELOPMENT under this Agreement according to the state of the art, in accordance with European current Good Manufacturing Practice (European cGMP) and in compliance with all applicable governmental regulations, as defined by COM and provided to CMO.”

b. By clause 4.4:

“CMO shall use all reasonable endeavours to complete the DEVELOPMENT in accordance with the development plan Annex ./2” (emphasis added)

c. By clause 4.5:

“CMO commits to co-operate with COM to achieve Clinical Study Approval and Marketing Authorisation for the PRODUCT. If any competent governmental authority asks for information related to the DEVELOPMENT of the PRODUCT, CMO shall within 15 working days hand over to COM all available information in written form and at no further cost. If required by any governmental authority, CMO will use its best effort to support any activities. All related costs will be charged separately if not originally part of the DEVELOPMENT or caused by mistake by CMO. If further activities are necessary, CMO shall within 10 working days provide a detailed and mandatory timetable by when this work will be completed.”

d. By clause 4.6:

“CMO shall hand over to COM the DOSSIER in relation to the PRODUCT upon completion of the DEVELOPMENT or upon written demand by COM according to the development plan, Annex ./2

The DOSSIER shall under no circumstances be subject to any right of retention by CMO” (emphasis added)

(5) By clause 10.6, the parties agreed an exclusion clause that stated:

“In no event will either PARTY be liable to the other PARTY for any indirect or consequential loss or damages, including without limitation, direct or indirect loss of profits, arising from or in connection with this AGREEMENT and/or any WORK ORDER.”

(6) By clause 12, the parties agreed various provisions as regards to termination including:

a. By clause 12.1

“This Agreement will come into force on the effective date. This Agreement shall remain in effect for the term defined in the development plan (Annex ./2).”

As will be seen, Annex./2 sets out a series of items of work, with illustrative development timelines. Thus, the end date is when all those work items in Annex./2 are completed.

b. By clause 12.3

“Upon the negligently or wilfully caused failure in fulfilling the development plan or any other material breach or default of this Agreement by either party, the other party shall have the right to terminate this Agreement in whole or in relation to parts thereof by giving thirty (30) days prior written notice. Such termination shall become effective immediately unless COM or CMO shall have cured any such breach or default prior to the expiration of the thirty (30) day period referred to above.”

c. By clause 12.4

“Notwithstanding the above clause 12.3, COM shall have the right at any time to terminate this Agreement in whole within thirty (30) days by giving written notice therefore to CMO.”

d. By clause 12.5

“Upon termination, COM agrees to pay CMO for the DEVELOPMENT which has been performed by CMO prior to termination of the Contract and to pay reasonable and evidenced costs relating to the cessation of the DEVELOPMENT, but such costs will in no case exceed the total payments to be paid by COM as defined in Annex 3.”

(7) Clause 16.6 provided that:

“This Agreement embodies the entire understanding of the parties and shall supersede all previous communications, representations or understandings, either oral or written, between the parties relating to the subject matter hereof. Changes in this Agreement (including this phrase) have to be done in writing.” (emphasis added)

(8) There are then a series of Annexes, the most important of which is Annex./2. This sets out the development plan (the “Development Plan”) and defines the DEVELOPMENT services to be undertaken by the Defendant for the IMPD, as well as what is described as “illustrative development timelines” for the same, which stated “Timelines will be agreed between the parties following signature of contract by both parties.”. That timeline expressly refers to the preparation of Module 3 documentation, which is only relevant to manufacturing for commercial exploitation from the site mentioned in the MAA. The timelines were slightly amended subsequently due to delays in API shipment: this amendment was recorded under Annex./7.

(9) The Development Plan in Annex./2 states that master batch records must be prepared in accordance with cGMP requirements, requires the preparation of the process validation protocol, the execution of process validation and the preparation of an analytical validation report. Process validation relates to the preparation of validation batches for a commercial manufacturing licence application. §9.1 of Annex./2 includes stability testing, which is also expressly included in clause 3.1. The Plan in Annex./2 also thereafter requires stability studies of the finished product over 36 months and the preparation of the IMPD for submission of clinical trial phases I-III with a “Production Timeline” of the end March 2012 for the release of three batches of each dose, at which time the stability study was meant to commence. The Development Plan also includes the preparation of Module 3 documentation, which is only relevant to manufacturing for commercial exploitation from the site mentioned therein.

(10) §9.1 of Annex./2 includes stability testing, which is also expressly included in clause 3.1.

(11) The Defendant thereafter drafted a detailed development plan called P-258 (the “Detailed Development Plan”), the contents of which are very similar to those contained in Annex 2, but which develop various of the obligations in further detail and, as envisaged by the opening words of Annex ./2 in relation to timelines, which stated: “Timelines will be agreed between the parties following signature of contract by both parties”, set out specific timelines, assigning responsibility to various departments for particular steps and indicating that “Unless stated, the next step cannot be carried out until the previous one has been completed.” The precise date of the document is unclear. It was suggested by Dr Lomas that it possibly preceded the DA, and therefore was to be treated as a pre-contractual document, excluded by reason of clause 16.6 of the DA. In my judgment, however the wording of the document in §2.0, entitled ‘BACKGROUND’, begins: “Moorfields Pharmaceuticals have been contracted by Orpha Trade to manufacture a medicine for clinical trial supplies.”, makes clear that the DA had already been entered into and therefore has to be regarded as part of the DA, pursuant to the provisions of Annex.2./. I would draw attention to the following aspects of the Detailed Development Plan:

a. The formulations are set out at §2.3;

b. §3.2 is entitled ‘Phase 2 Clinical / process validation batch manufacture’ and provides:

“[the Defendant] will manufacture a 3 batch campaign for each strength. The purpose of these can be seen in Table 5. [The Defendant] will generate a Process Validation protocol. Analytical Development will generate a stability protocol.”

c. Tables 5 to 8 then set out various technical details relating to the manufacture of the validation batches. As set out above, Table 5 defines the purpose of the validation batches as being:

|

Table 5: Phase 2 Testing | ||

|

|

Purpose |

Testing |

|

Batch 1 |

Stability samples Process Validation samples Finished product release samples Sterility validation samples Endotoxin validation samples |

Mixing validation, pH adjustment volumes, weight per mL, filter discard (confirmation), fill volumes |

|

Batch 2 |

Stability samples Process Validation samples Finished product release samples |

Confirmation of parameters determined above |

|

Batch 3 |

Process Validation samples Finished product release samples |

Confirmation of parameters determined above |

|

Batch 4 |

Finished product release samples |

Finished product samples |

d. Table 9 details various “design inputs” including:

“Regulatory and statutory requirements of intended markets: This is for clinical trial in Europe and is therefore governed by European legislation”.

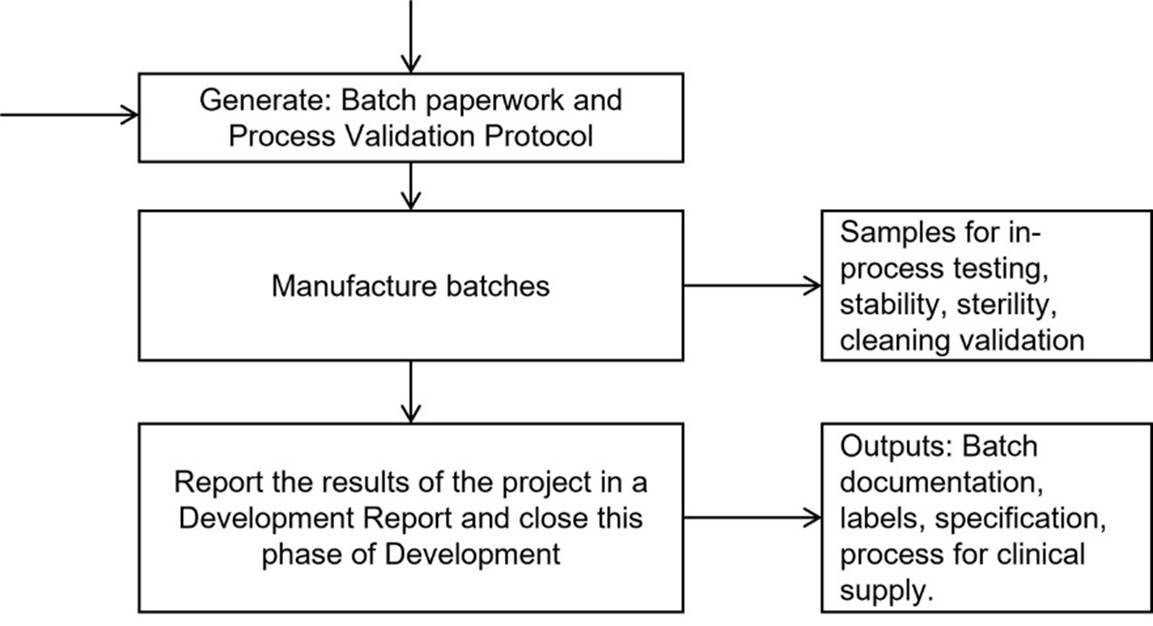

e. Figure 2 turns the Detailed Development Plan into a flow chart, which includes the generation of “Batch paperwork and Process Validation Protocol” and ends with the generation of a “Development Report” (which correlates with Step 12 in Table 11):

The Implied Terms in the DA alleged by the Claimant

24. Whilst acknowledging that, given the terms of the DA, there is limited scope or need for the implication of terms, the Claimant contends that there were also terms to be implied into the DA. Paragraph 25 of the Particulars of Claim formulated the matter in this way:

“The parties’ intention and agreement, as reflected in the express terms of DA, by standard industry practice and by implication for business efficacy and/or to give effect to the parties’ intention was that [the Defendant] would:

(i) develop and manufacture process validation batches of the Drug for the purpose of submitting an application to European regulators for a commercial manufacturing licence. Process validation requires the approval of the manufacturing equipment and methodology and demonstrates that the commercial batch size is consistently reproducible under the validated controlled conditions. The parties’ subsequent conduct is evidence of the contractual intention as it existed when the DA was entered into. The Claimant submitted a manufacturing licence application to the Austrian regulator (referred to in more detail below) which included process validation data prepared by [the Defendant]. This was only required for the commercial manufacture of the Product since there would have been no requirement for validation data in respect of clinical trials to be included within the Claimant’s application, given that a standard sterilisation process was described in the pharmacopoeia;

(ii) develop and manufacture batches of the Drug to be used in clinical trials;

(iii) carry out stability testing on sample batches at regular intervals for up to 36 months;

(iv) be named as the commercial manufacturer in the Claimant’s manufacturing licence application;

(v) continue to develop the Drug until the Claimant’s application was finally determined, although [the Defendant] did not guarantee that the final Product could be successfully manufactured or that a manufacturing licence would be obtained;

(vi) as the commercial manufacturer named in the manufacturing licence application, co-operate with the Claimant at no additional cost in responding to the regulator’s questions and requests for information, and make any changes to the Drug determined necessary by the regulator as part of the licence application process;

(vii) maintain its European current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) accreditation throughout the Development and until final determination of the Claimant’s manufacturing licence application;

(viii) carry out the Development exclusively for the Claimant for at least 5 years, and longer if a manufacturing licence was obtained in that period. In that event, the parties’ intention was for MP to be the licensed commercial manufacturer of the final approved Drug for sale and commercial exploitation;

(ix) prepare the Module 3 documentation for the licence application. MP’s Sophia Titus (described in Annex 6 of the DA as the Project Manager CTM and as a Responsible Person) contacted the Claimant 26 March 2013 to state that Premilla Pillay (described in Annex 6 of the DA as the Regulatory Manager and as a Responsible Person) was leaving and seeking permission to outsource the Module 3 report to an external consultant so that the report could be ready in time for filing the licence application. The Module 3 Report, including the required data for commercial manufacturing in Section 3.2.P.8.2 concerning the Post-Approval Stability Protocol and Stability Commitment, was eventually produced by MP and invoiced thereby to the Claimant on 28 May 2013.”

25. Suffice it to say that the basis upon which these terms fall to be implied and their content is hotly contested by the Defendant.

Events after the DA

26. On 7 March 2012, Dr Strieder carried out a GMP audit of the Defendant’s site.

27. On 17 August 2012, the Claimant purchased 150 grams of API (in three batches of 50 grams) from Chirogate International Inc (“Chirogate”), a Taiwanese supplier, for US$932,880 whilst the DA was still in the name of CompLex, and this was shipped directly from Taiwan to the Defendant in London. This API was used to manufacture the 12 validation batches between November 2012 and January 2013, although subsequent batches were manufactured for clinical trials until November 2013, shortly before sterile manufacturing was suspended at the Defendant’s site, following critical inspections by the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (the “MHRA”) starting in December 2013, which identified failures to comply with GMP.

28. By an additional scope of works order dated 1 November 2012, the size of the vials was changed to 20ml, and stability testing was extended to 36 months. It was one of a number of additional scope of works orders, which effectively supplemented Annex./2.

29. On 16 November 2012, the DA was transferred to the Claimant.

30. On 22 November 2012 the Defendant’s Validation Protocol was signed off. This was a validation document for the process validation batches, being three active batches for each concentration of the solution.

31. On 17 January 2013, there was a telephone conference call between Dr Strieder and an Andrew Froome and Sophia Titus on behalf of the Defendant. Amongst other things, the Defendant was informed by Dr Strieder that Orpha Trade /the Claimant wished to file the MAA, accompanied by three months of stability data. If possible, the Claimant wanted to have the first draft of Module 3 by the end of March 2013, with the process validation report.

32. On 28 February 2013, the Defendant produced its Validation Summary Report.

33. On 11 March 2013, additional work was agreed for the generation of the drug product section of Module 3 at a price of £6,573.

34. In November 2013, section 3.2.P.3.1 of CTD Module 3 named the Defendant as the proposed manufacturer and stated that the Product would be manufactured in accordance with GMP.

35. On 19 December 2013, without prior notice to the Claimant, the Defendant voluntarily suspended manufacturing. It appears that the Defendant was unable to carry out aseptic filling and sterile terminalisation in the preparation of the vials containing the Product in accordance with GMP. Although it was frequently stated on behalf of the Defendant that its remedial action plan would result in a successful further audit by the MHRA, and the resumption of manufacturing, this did not happen and, eventually, in January 2015, the Defendant closed its site.

36. Ms Tan’s evidence, which I accept, was that when the Defendant lost its GMP status, the Defendant’s staff with whom she was dealing, including Ms Beveridge, appreciated the serious impact the suspension of manufacturing would have on the Project. There was a need for a continuous supply of the Product under the DA for the clinical trials. Once a patient had been included in the trial and commenced taking the Product, he or she needed to receive the Product for life. An interruption in its supply could have been life-threatening. Immediate emergency measures had to be taken, such as re-labelling existing batches destined for other use and extending the shelf-life of available vials. The re-labelling exercise and liaising with clinical trial centres in different European Union (“EU”) member states took considerable time. On 10 February 2014, Mr Skelton, the Defendant’s Quality Assurance Manager, issued new certificates of analysis for the batches manufactured in November 2013 with their shelf-lives extended to June 2014 to cater for the suspension of manufacturing.

37. As stated at paragraph 6(3) above, on 25 February 2014, Diapharm filed the MAA in Austria in relation to the Product. The Defence challenged the basis on whose behalf that application was made. In my judgment, it was clearly made on behalf of the Claimant, as the email dated 10 September 2014, from Dr Risse, an employee of Diapharm, to Ms Beveridge stated. This was the conclusion of Dr Gamlen, at paragraph 30 of his initial report, addressing the Annex 1 issues, where he stated that it is not unusual for such applications to be filed by local agents to ensure that local requirements are met.

38. On 27 February 2014, the Hungarian regulator confirmed to Dr Risse that frozen samples could be sent directly from the UK to Hungary, and he requested the Defendant to send samples directly to Hungary. This was done. This therefore indicates that the Defendant submitted samples for the purpose of validation in respect of a MAA.

39. At this stage the Defendant had the acquired Development know-how and technology and there was no other way to manufacture clinical trial batches. In order to guarantee a continuous supply of Product to the clinical study and to proceed with the MAA process, a new manufacturer had to be found. There was little available choice of alternative manufacturers.

40. Following a request from AGES, on 13 March 2014 Mr Skelton confirmed that the Defendant was licensed for manufacturing with batch certification.

41. Following inspections on 6 and 7 May 2014, the MHRA wrote to the Defendant notifying it of on-going failures to comply with the GMP.

42. On 28 May 2014, the MHRA agreed that in view of the dangers to patients, previously manufactured Product could continue to be supplied to patients provided certain conditions were satisfied, including confirmation from the Claimant as the sponsor. The MHRA accepted that the timelines for transferring the drug to another manufacturer would not alleviate the potential shortages of supply, however they expressly wrote that reinstatement of manufacture of the Product “is not authorised”. The MHRA expressly requested the parties to provide plans of how the Product could be transferred to an alternative manufacturing site whilst maintaining continuity of supply.

43. The Defendant’s own risk assessment carried out in about mid 2014 stated:

“Moorfields has undertaken a comprehensive search of small scale sterile manufacturers but to date a suitable site has not been found - due to limited capacities, capabilities and the timelines for the transfer of manufacturing…. Moorfield has therefore not been able to identify to date a manufacturer that has the capabilities, plus the ability to commence immediately the transfer of the manufacturer of Treprostinil clinical supplies. Notwithstanding that, even with an immediate start, the continuity of clinical supplies would be compromised, which would result in a medically critical situation….

Patients who have been recruited into clinical study, and who respond positively, are maintained through compassionate supply. This continued compassionate supply is diluting the availability of previously manufactured stock and this reducing the supplies available to continue active recruitment. Active recruitment is required to successfully compete the clinical programme.

Moorfields and SciPharm have worked closely to develop and manage the production process, to complement and satisfy the ongoing clinical requirements. Based on the timelines and assumptions, Moorfields and SciPharm believe that the process to transfer the production elsewhere would inevitably have an impact on the clinical programme. Transfer would not ensure continuity of supply and would result in a medically critical shortage of study medication and compassionate supplies. To ensure continuity of supplies, it will be necessary to utilize the stock already held at Moorfields and for Moorfields to manufacture a further batch.”

44. Unfortunately, the Defendant’s request for permission from the MHRA to manufacture an emergency batch for patients who faced stock shortages was unsuccessful. Recipharm AB, a Swedish manufacturing company based in Solna (“Recipharm”) was identified as the only other available manufacturer worldwide to manufacture Product in the time available before stocks were depleted, but, even with an immediate start, there was still the problem of ensuring continuity of supply. Since no manufacturing had been undertaken by the Defendant since 2013, the result was that there would be a critical shortage of the 10 mg strength of the Product by Q4 2014. It was therefore necessary for the Defendant to manufacture a further batch of the 10 mg strength which could be released in early Q4 2014.

45. The only solution available to achieve this was for Recipharm to manufacture an emergency batch at increased cost, requiring the Defendant urgently to transfer the technology to Recipharm, on the basis that aseptic filling and sterile terminalisation would be undertaken in Sweden, and labelling, packaging and batch release would be done by the Defendant.

46. On 25 June 2014, the Claimant entered into a new development agreement with Recipharm (the “New DA”), in materially the same terms as the DA.

47. On 29 July 2014, AGES produced its Day 70 Report on the MAA. It named the Defendant as the proposed manufacturer for both dosage and batch release. It stated that the MHRA’s statement on the Defendant’s non-compliance with GMP was a “major objection” and they wrote to Diapharm posing 63 technical questions on the drug substance and product before a decision would be taken on the MAA.

48. On 1 August 2014, Dr Strieder sent the Defendant AGES’ list of 63 questions to the Defendant and requested answers by mid-August 2014. On 14 August 2014 the Defendant sent its replies to the 63 questions. In response to question 33, it stated that it, rather than Orpha Trade, should be named as the manufacturer and the role of Orpha Trade should be explained by the Claimant.

49. From the minutes of a meeting held on 30 September 2014 between representatives of the parties, which minutes were amended by Ms Tan and Dr Strieder, it appears to have been agreed that final answers to the questions posed by AGES would be submitted by the first week of December 2014.

50. In October 2014 two anonymous whistleblowing letters were sent to the MHRA, one from “a number of staff”, complaining of bad working practices, poor leadership, staff bullying, resignations and a series of GMP breaches.

51. Pursuant to requests made by the Defendant on 6 and 8 October 2014, on 28 October 2014, the MHRA wrote to the Defendant that they had reviewed the outsourcing proposal and did not object to the technology transfer to Recipharm. The parties interpreted this as permission for Recipharm to manufacture and for the Defendant to pack, label and release the batches.

52. However, on 6 November 2014, Philip Greaves, the Director of Quality wrote to Dr Strohmaier, the Managing Director of the Claimant, and Ms Tan to state that, as a result of the whistleblowers’ complaints, the MHRA had inspected the Defendant on 30 October 2014 and had upheld some of the allegations. He attached a copy of the inspectors’ report and that said the Defendant was waiting for a decision. Mr Greaves stated that until they had heard back from the MHRA, even existing supplies labelled and prepared for dispatch would not be released.

53. On 13 November 2014, the MHRA wrote to the Defendant, giving notice that in view of the deficiencies in relation to GMP inspected on 30 October 2014 and which had been continuing since 19 December 2013, the decision had been taken to suspend that part of the Defendant’s manufacturing licence which authorised aseptic manufacture and terminal sterilisation processes with immediate effect until 12 February 2015. The MHRA wrote that there was a risk to public health arising from a lack of sterility assurance and that undertaking further terminal sterilisation would constitute a criminal offence.

54. In late November 2014, the Defendant audited Recipharm for the technology transfer and the emergency batch was manufactured by Recipharm and released by the Defendant.

55. In response to a request from Dr Strohmaier on 26 January 2015 as to whether the Defendant expected to regain full operational capacity, on 27 and 28 January 2015, the Defendant indicated that it planned to cease all production of pharmaceutical products. An email dated 28 January 2015 from Tim Record, the Defendant’s Operations Manager, pasted a copy of a formal announcement which included the statement: “Given the length of the suspension, the board has concluded that re-instating manufacturing after such a lengthy pause would be too costly and complex.”

56. On 3 February 2015, a telephone conference call took place between Dr Strohmaier, Dr Strieder and Ms Tan on behalf of the Claimant and Mr Record, Mr Froome and Ms Beveridge on behalf of the Defendant, when the Claimant was informed that the Defendant would cease all activities around the end of April 2015, including manufacturing, packaging and stability and would close its production facility. As a result, the Defendant could no longer complete the stability testing on manufactured batches and the Claimant was required to transfer stability testing and packaging to another manufacturer.

57. On 7 May 2015 the Defendant’s then solicitors sent a draft Deed of Termination seeking to terminate the DA and to release the Defendant from all liability. The Claimant did not execute that document.

58. On 15 December 2015 the Claimant sent a letter before claim to the Defendant.

59. In November 2016, Recipharm prepared a new Validation Report and a new Module 3 submission for the Claimant.

60. After a period of postponement, on 14 June 2018, the MAA was reinstated, with Recipharm being named as the commercial manufacturer for compounding, filling, sterilisation, packaging and labelling. It named Amomed as the manufacturer for batch release and the marketing authorisation holder. The MAA was carried through to market authorisation.

61. From the beginning of 2019, marketing authorisations were given in various EU member states in the name of Amomed. The Claimant relied upon the Hungarian licence in respect of the 10 mg solution, as an example of a MAA, which, whilst showing Amomed as the licence holder, expressly states that the “applicant submitted an application for marketing authorisation” on 25 February 2014, this being the original application filed by Diapharm which was stayed and then reinstated with Recipharm as manufacturer.

62. On 13 September 2019 the Claimant issued its claim.

63. I would add, for completeness that the Product is also used to treat Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (“CTREPH”). The Claimant filed an entirely separate marketing authorisation application in respect of CTREPH that has no relevance to this claim. There are a number of documents in the bundles which refer to this. That application was withdrawn due to a technicality, was re-submitted and has been authorised since 2020.

The Law

64. I turn to the principles to be applied when construing contractual agreements.

65. First, in relation to construction of express terms, there is a helpful summary contained in the judgment of Stuart-Smith LJ, who gave the only reasoned judgment in European Film Bonds A/S v Lotus Holdings [2021] EWCA Civ 807 at [43]-[44], with which Sir Nicholas Patten and Asplin LJ agreed, where he stated:

“43. The Judge, having referred to Rainy Sky SA v Kookmin Bank [2011] UKSC 50, Arnold v Britton [2015] UKSC 361 at [15] and Wood v Capita Insurance Services Ltd [2017] UKSC 24, summarised the relevant principles of contractual construction at [52] as follows:

“(1) The court's task is to ascertain the objective meaning of the language which the parties have chosen to express their agreement. It has long been accepted that this is not a literalist exercise focused solely on a parsing of the wording of the particular clause, but that the court must consider the contract as a whole and, depending on the nature, formality and quality of drafting of the contract, give more or less weight to elements of the wider context in reaching its view as to that objective meaning.

(2) Interpretation is a unitary exercise; where there are rival meanings, the court can give weight to the implications of rival constructions by reaching a view as to which construction is more consistent with business common sense. But, in striking a balance between the indications, given by the language and the implications of the competing constructions, the court must consider the quality of drafting of the clause.

(3) The court must also be alive to the possibility that one side may have agreed to something which with hindsight did not serve his interest. This exercise involves checking each suggested interpretation against the provisions of the contract and investigating its commercial consequences. Similarly, the court must not lose sight of the possibility that a provision may be a negotiated compromise or that the negotiators were not able to agree more precise terms.

(4) Textualism and contextualism are not conflicting paradigms in a battle for exclusive occupation of the field of contractual interpretation. Rather, the lawyer and the judge, when interpreting any contract, can use them as tools to ascertain the objective meaning of the language which the parties have chosen to express their agreement. The extent to which each tool will assist the court in its task will vary according to the circumstances of the particular agreement or agreements.

(5) Account should be taken of the fact that negotiators of complex formal contracts may often not achieve a logical and coherent text because of, for example, the conflicting aims of the parties, failures of communication, differing drafting practices, or deadlines which require the parties to compromise in order to reach agreement. There may often therefore be provisions in a detailed professionally drawn contract which lack clarity and the lawyer or judge in interpreting such provisions may be particularly helped by considering the factual matrix and the purpose of similar provisions in contracts of the same type.

43. The provenance of each element of this statement of principles is clear and uncontroversial. The principles were adopted by the parties for the purposes of the appeal. With one minor gloss, I fully endorse that approach: it is quite unnecessary for the Court to provide yet another iteration of the relevant principles or to cite chunks of the leading authorities which underpin the Judge's formulation. The only gloss that I would apply is to recognise that most iterations of these principles, even at the highest level, have subtle differences of emphasis. It is usually clear that these differences are because the Court will have in mind the facts of the particular case and so may highlight aspects of the general principles that are particularly relevant to the case that it has to decide. That said, I would normally include in any iteration of the principles, the principle derived from ICS v West Bromwich Building Society [1998] 1 WLR 896, 912H, reaffirmed with slight refinements many times since, that interpretation is the ascertainment of the meaning which the document would convey to a reasonable person taking into account facts or circumstances which existed at the time that the contract was made, and which were known or reasonably available to the parties to the contract.”

66. In relation to whether terms fall to be implied into a contract, there was a helpful and uncontroversial summary of the relevant authorities contained in paragraphs 116 to 118 the Defendant’s written submissions as follows:

“116. As for implication of terms, in Philips Electronique Grand Public SA v British Sky Broadcasting Ltd [1995] EMLR 472, 481, Sir Thomas Bingham MR explained that it was “difficult to infer with confidence what the parties must have intended when they have entered into a lengthy and carefully-drafted contract but have omitted to make provision for the matter in issue", because “it may well be doubtful whether the omission was the result of the parties' oversight or of their deliberate decision”, or indeed the parties might suspect that "they are unlikely to agree on what is to happen in a certain ... eventuality" and "may well choose to leave the matter uncovered in their contract in the hope that the eventuality will not occur.

117. Sir Thomas went on to say this at p.482 (emphasis added):

“The question of whether a term should be implied, and if so what, almost inevitably arises after a crisis has been reached in the performance of the contract. So the court comes to the task of implication with the benefit of hindsight, and it is tempting for the court then to fashion a term which will reflect the merits of the situation as they then appear. Tempting, but wrong… [I]t is not enough to show that had the parties foreseen the eventuality which in fact occurred they would have wished to make provision for it, unless it can also be shown either that there was only one contractual solution or that one of several possible solutions would without doubt have been preferred ...”

118. The judgment of the Supreme Court in Marks and Spencer plc v BNP Paribas Securities Services Trust Company (Jersey) Ltd & Anor (Rev 1) [2015] UKSC 72 restated the law at [14] to [32] citing, inter alia, Philips Electronique, to which Lord Neuberger added the following comments:

[21] In my judgment, the judicial observations so far considered represent a clear, consistent and principled approach. It could be dangerous to reformulate the principles, but I would add six comments on the summary given by Lord Simon in BP Refinery as extended by Sir Thomas Bingham in Philips and exemplified in The APJ Priti. First, in Equitable Life Assurance Society v Hyman [2002] 1 AC 408, 459, Lord Steyn rightly observed that the implication of a term was "not critically dependent on proof of an actual intention of the parties" when negotiating the contract. If one approaches the question by reference to what the parties would have agreed, one is not strictly concerned with the hypothetical answer of the actual parties, but with that of notional reasonable people in the position of the parties at the time at which they were contracting. Secondly, a term should not be implied into a detailed commercial contract merely because it appears fair or merely because one considers that the parties would have agreed it if it had been suggested to them. Those are necessary but not sufficient grounds for including a term. However, and thirdly, it is questionable whether Lord Simon's first requirement, reasonableness and equitableness, will usually, if ever, add anything: if a term satisfies the other requirements, it is hard to think that it would not be reasonable and equitable. Fourthly, as Lord Hoffmann I think suggested in Attorney General of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd [2009] 1 WLR 1988, para 27, although Lord Simon's requirements are otherwise cumulative, I would accept that business necessity and obviousness, his second and third requirements, can be alternatives in the sense that only one of them needs to be satisfied, although I suspect that in practice it would be a rare case where only one of those two requirements would be satisfied. Fifthly, if one approaches the issue by reference to the officious bystander, it is "vital to formulate the question to be posed by [him] with the utmost care", to quote from Lewison, The Interpretation of Contracts 5th ed (2011), para 6.09. Sixthly, necessity for business efficacy involves a value judgment. It is rightly common ground on this appeal that the test is not one of "absolute necessity", not least because the necessity is judged by reference to business efficacy. It may well be that a more helpful way of putting Lord Simon's second requirement is, as suggested by Lord Sumption in argument, that a term can only be implied if, without the term, the contract would lack commercial or practical coherence.

[…]

[29] …the process of implication involves a rather different exercise from that of construction. As Sir Thomas Bingham trenchantly explained in Philips at p 481:

“The courts' usual role in contractual interpretation is, by resolving ambiguities or reconciling apparent inconsistencies, to attribute the true meaning to the language in which the parties themselves have expressed their contract. The implication of contract terms involves a different and altogether more ambitious undertaking: the interpolation of terms to deal with matters for which, ex hypothesi, the parties themselves have made no provision. It is because the implication of terms is so potentially intrusive that the law imposes strict constraints on the exercise of this extraordinary power.”

67. Applying those principles, I turn to the central issues of the ambit of the Defendant’s obligations under the DA. Both Counsel have made lengthy written and oral submissions, before, at and after the hearing. I do not intend to reproduce them at length, but instead produce a summary of the principal points taken. Suffice it to say that I have re-read the transcripts of the hearing and have carefully considered all the parties’ written submissions.

The Claimant’s submissions in relation to the ambit of Defendant’s obligations under the DA

68. In summary the Claimant’s submissions were as follows:

(1) Properly construed, the Defendant’s obligations went further than simply one of “filling and finishing” the manufacture and delivery of the twelve validation batches. The DA set out a long term commitment between the parties to develop the Product through clinical trials and the marketing authorisation process, until the Product, clinically tested on patients and authorised for commercial sales on the market, was developed;

(2) The parties were to use the data which the Defendant processed and collected from the initial 12 validation batches in order to submit those processes for validation in the MAA, stability test those batches over 36 months and administer the batches (as well as future batches) to conclude the Dossier;

(3) Clause 4.1 contained an undertaking from the Defendant to perform “all Development” in accordance with GMP. As Dr Gamlen said: “the requirement for the manufacturer to maintain their GMP status during, and after completion, of the development work is absolute” [4];

(4) It is clear that the DA required development for a MAA. Mr Sinai relied upon the following:

(i) In clause 2.1, the definition of “Development” expressly referred to “all work necessary to fulfil the demands of the… Common Technical Document”, which is the MAA. The definition of “Development” excludes the work required for Part 3.2.P of the CTD (which is one sub-part of Module 3 of the application form). Since only this aspect was excluded, the rest of Module 3 was necessarily included in the DA. In addition, Module 3 is expressly included in the Illustrative Development Timelines of Annex 2. Furthermore, nothing turns on the exclusion of Part 3.2.P because the Defendant costed Module 3 in a subsequent scope of work document and the Claimant paid for that work, including Part 3.2.P. It therefore fell within the additional work agreed between the parties envisaged in clause 3.1 of the DA. In the event, the Defendant prepared all of Module 3, which included the data and analytical test reports that the Defendant carried out on the validation batches that it manufactured;

(ii) In clause 2.1, the definition of “Dossier” expressly included information in connection with the “Common Technical Document” and importantly includes “any expert report”. The reference to an expert’s report in the definition of Dossier in the DA is proof that it was for an MAA. As Dr Gamlen stated “All of the documentation that… I have been shown confirms that this was, indeed, preparation for market authorisation” [5];

(iii) In clause 3.1, the Development is stated to comprise “long-term stability and quality control” [emphasis added]. The latter is a reference to the MAA;

(iv) Looking at the contract as a whole, the indicia are that the Defendant’s obligation was more than a “fill and finish” obligation:

(a) clause 1.4 refers to a supply agreement “once the product is successfully registered”. Those words must refer to market authorisation;

(b) under clause 3.3 the Defendant agreed to perform the Development of the Product exclusively for the Claimants for 5 years (being the time that it usually takes to bring a drug to the market) in order for the Claimant to “achieve market authorisation” in at least one European member state. Should that not happen, the DA would be terminated;

(c) clause 4.5 provided that the Defendant “commits to co-operate with [the Claimant] to achieve Clinical Study Approval and Marketing Authorisation for the Product.” [emphasis added]. It follows that the on‑going work required for the MAA under clause 4.5 to “achieve market authorisation” is part of the “Development” and therefore must be performed “in accordance with GMP.” This clause expressly included the provision of information, in written format and at no extra cost, to the market regulator. It also included further “activities” if required by the regulator, albeit the Defendant was entitled to be remunerated if such activities were not initially costed. As stated above, further information was sought by the regulator and more work was required at Day 70 of the MAA which the Defendant was unable to provide and undertake in view of the suspension of its manufacturing licence, in breach of the obligation contained in Clause 4.1 recited above;

(5) Mr Sinai contended that accepting the Defendant’s interpretation of clause 4.1 makes no business sense, because it means that the Claimant was paying for process validation batches and data which then could not be used in the MAA, if the Defendant decided to close its facility or relinquish its manufacturing licence. The Defendant’s interpretation is commercially unrealistic because it would mean that:

(i) The Claimant incurred very significant expenditure for creation of validation batches but took all the risk that such batches could not be used for the precise purpose for which they were created, simply because of circumstances brought about entirely by the Defendant;

(ii) The Defendant gave an express undertaking to manufacture validation batches in accordance with GMP, but its obligation had lapsed by the time that its validation batches and its processes came to be assessed by the regulator;

(6) Paragraph 9.1 of Annex 2 (and therefore a term of the DA) included stability testing (which is also expressly included in clause 3.1 on the Subject Matter of the DA). Testing was extended to 36 months by an additional scope of works on 1 November 2012. Stability testing (and therefore the Development) was not completed and had to be transferred to Recipharm when the Defendant closed its site at the end of April 2015;

(7) Dr Gamlen was not prepared to accept that the Development Plan in Annex 2 of the DA was “doomed to fail” as work required for a MAA. He said that Annex 2 was not of itself sufficient, but the issue would depend on what was actually included as the specific requirements of the process validation and the skill with which the process validation protocol is written; [6]

(8) The Dossier was not limited to the IMPD. Mr Sinai relied upon the following:

(i) Dr Gamlen confirmed that process validation is not required for a standard sterilisation process and only for a generic MAA, that the clinical trials were in phase 2 for which process validation would not be required [7], and there was no reason that he could think of as to why an IMPD would have to be filed in CTD format ab initio [8];

(ii) As stated at paragraph 68(4)(ii) above, the definition of “Dossier” expressly refers to an expert’s report: Dr Gamlen said that the reference to an expert’s report in the definition of Dossier is proof that the Dossier was for a MAA [9].

(9) The references in the DA to “quality control” and “regulatory approval” are not references to IMPD. Mr Sinai relied upon the following:

(i) the references to “registration” and “market authorisation” in the DA;

(ii) when looking at the wider context and factual matrix:

(a) the Defendant’s Detailed Development Plan P-258 refers to “licence submission” at paragraph 1.0 entitled “SCOPE” and at paragraph 6.0 to “Design Inputs: Quality Target Product Profile”. According to Dr Gamlen, these are only relevant to MAA [10] ;

(b) the parties wanted the Defendant to become the commercial manufacturer of the licensed product and it is admitted that Ms Beveridge prepared the 5 year plan for commercial manufacturing. Mr Sinai accepted, however, that the 5 Year Plan was a hope which in the absence of a commercial manufacturing agreement is equally consistent with a fill and finish function. The highest he put it was that, when the DA was entered into a commercial manufacturing agreement was definitely “on the radar”;

(10) Finally, Mr Sinai relied on the parties’ subsequent conduct as evidence of their contractual intention as it existed when the DA was entered into. In particular he pointed to:

(i) A letter dated 9 May 2014 from Alan Krol, the Defendant’s Managing Director, which stated: “we are unable to inform you as to precisely how long we will cease manufacturing and the impact that this will have on our contract with you.”;

(ii) An email dated 14 August 2014 from Ms Krupa Gokani, a Project Manager of the Defendant to Dr Strieder, where the Defendant sent its replies to AGES’ Product questions for the MAA (without any further charges as this was included in the DA);

(iii) The agenda for the meeting of 30 September 2014 in London where one discussion item for the afternoon was “additional work required by Moorfields including request from Diapharm for QA/regulatory information”;

(iv) An email from Dr Strieder to Diapharm dated 1 October 2014 following the meeting in London where he wrote that it was decided that Diapharm’s answers would be responded to jointly by the Claimant and the Defendant by the end of November 2014;

(v) The draft Deed of Termination sent on May 2015 seeking to terminate the DA and to release the Defendant from all liability, which document is wholly inconsistent with the Defendant’s Defence herein and the assertion that its obligations were limited to “fill and finish” of the 12 validation batches already manufactured.

The Claimant’s submission in relation to the Implied Terms

69. In closing Mr Sinai submitted that on the basis of Dr Gamlen’s evidence, the Court should have no difficulty implying that the requirement to maintain GMP until final determination of the MAA is both necessary for business efficacy and so obvious as to go without saying:

(i) If the GMP licence of the named manufacturer and site were suspended, then the process validation data was not going to be approved; Dr Gamlen stated: “the link between the process validation data and the physicality of the site is absent” [11];

(ii) Dr Gamlen confirmed the opinion in paragraph 34 of his first report that “the requirement for the manufacturer to maintain their GMP status during, and after completion, of the development work is absolute” [12];

(iii) When questioned by me about clause 4.1 of the DA, Dr Gamlen said that all the data which is submitted for a market authorisation application would have to be generated under GMP [13];

(iv) It was Dr Gamlen’s opinion that it is standard to state in section 3.2.P.3 of the CTD that the named manufacturer would manufacture the Product in accordance with GMP [14];

(v) Dr Gamlen confirmed the point made in paragraph 25(v) of the Amended Particulars of Claim that it is standard industry practice for the named manufacturer to continue to develop the Product until the Claimant’s MAA was finally determined [15].

The Defendant’s submissions in relation to the ambit of Defendant’s obligations under the DA

70. Mr Lomas relied upon the fact that the DA is a detailed and professionally drafted agreement. Thus, the focus of the interpretive exercise should be to analyse the text used rather than to resort to extraneous matter. In this regard he relied upon the cases of Rainy Sky, Arnold v Britton and Wood v Capita referred to at paragraph 65 above. There is no ambiguity in the express terms which needs resolving.

71. On the Defendant’s case, the entire scope of the DEVELOPMENT must fall within the four corners of the Development Plan at Annex./2, as updated by mutually agreed Work Orders. He submitted that this is ultimately a matter of interpretation, in circumstances where there is no sole or predominant purpose ascribed to the batches produced by the Defendant under the DA, the definition of “DEVELOPMENT” under the DA merely requires “all work” to be done, i.e., batches to be manufactured (and related data to be generated) that was necessary to “fulfil the demands” of:

(1) the Guideline on the Requirements to the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Quality Documentation Concerning Investigational Medicinal Products in Clinical Trials (October 2006) by the EMEA CHMP; and

(2) the Notice to Applicants, Volume 2B, incorporating the Common Technical Document (CTD Part 3.2.P) (May 2008) by the European Commission except for chapter 3.2.P.2.

72. The extent of “all work” was clarified as being: (i) “the transfer of the production process from a former manufacturer”; and (ii) the manufacture and analysis of three batches. The scope of the Defendant’s obligations in respect of DEVELOPMENT is then defined by Clause 3.1 by reference to Annex./2. Annex./2 sets out nine discrete activities compromising the totality of the DEVELOPMENT, which he describes in detail at paragraph 128(b) of the Defendant’s opening written submissions. I do not reproduce them here. Suffice it to say, he submitted there is nothing in the DA that even mentions a MAA, let alone supports the contention that the Defendant was under an obligation to support one. The reference to an IMPD was indicative that the work concerned was at a far more embryonic stage of drug development, where clinical trials had not yet even been approved to start.

73. Manifestly, the three batches (and the related analytical data) did fulfil the demands of both documents: clinical trials were conducted, the data (including stability data) was used for the IMPD, and the Defendant was contracted under a separate work order (as an obligation outside the scope of the DA) to produce a first draft of Module 3 in reliance on the batches and the data, i.e. the data was manifestly considered by the Claimant as meeting the demands of the CTD and was able to be “plugged in” to the Notice to Applicants and the CTD.

74. To succeed the Claimant must either (i) establish that the DEVELOPMENT does not end until final determination of an MAA; or (ii) imply into clause 4.1 words that make retaining GMP status after DEVELOPMENT a free-standing obligation.

75. There is no basis on the face of the DA to read in an obligation on the part of the Defendant to maintain GMP until final determination of a generic MAA. Nor is there any commercial rationale for implying, as standard, a term to the same effect: industry practice was not followed in a key respect: the Claimant did not mitigate the risk of the Defendant not becoming manufacturer by entering into a supply agreement, so there is no basis to presume that the parties intended industry practice to apply in other areas. Thus, in the absence of an obligation, there can be no finding of breach.

76. It is important to note that in this context the definition of DEVELOPMENT is limited only to work for filing an IMPD - namely an application to approve using Investigational Medicinal Products in Clinical Trials. This is supported by: (i) the existence of and interpretation of the term DOSSIER at Clause 2.1, and the obligation at Clause 4.6 for the Defendant to hand this to the Claimant. DOSSIER is clearly a reference to an IMPD; and (ii) the fact that an IMPD often follows the same format of the CTD (also known as Module 3).

77. Specifically, there is no mention of an MAA or securing an MA at all: this is entirely rational as both of these are activities that would only take place after clinical trials had been successfully concluded. Further, the general definition of DEVELOPMENT in clause 2.1 is circumscribed by reference to the Defendant’s obligations to perform only certain DEVELOPMENT activities by reference to clause 3.1. Dr Lomas highlighted the particular words in that clause as follows:

“[the Defendant] shall perform the DEVELOPMENT in accordance with the directives given by [the Claimant] in writing and in accordance to the development plan given by [the Claimant] to [the Defendant] (Annex./2). The DEVELOPMENT comprises all necessary development steps for the manufacture and the chemical-pharmaceutical part including long-term stability and quality control. Additional subject matters have to be agreed on in writing and signed by both Parties. It is agreed and understood between the Parties that, contingent on the development character of this project, [the Defendant] does not assume any responsibility for the successful DEVELOPMENT of the PRODUCT and the regulatory approval of the product”.

78. An IMPD is a dossier comprising one of several pieces of IMP related data required in support of a clinical trial application, which is required ahead of the performance of a clinical trial in one or more EU member states. It is not a MAA, which can only be filled after completion of successful clinical trials, which often take many years to conclude.