Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court) Decisions >> Port De Djibouti SA v DP World Djibouti FZCO [2023] EWHC 1189 (Comm) (22 May 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2023/1189.html

Cite as: [2023] EWHC 1189 (Comm)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

KING'S BENCH DIVISION

COMMERCIAL COURT

IN THE MATTER OF THE ARBITRATION ACT 1996

AND IN AN ARBITRATION CLAIM

Rolls Building, Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| PORT DE DJIBOUTI S.A. |

Claimant/Respondent in the Arbitration |

|

- and - |

||

| DP WORLD DJIBOUTI FZCO |

Defendant/Claimant in the Arbitration |

____________________

Graham Dunning KC and Catherine Jung (instructed by Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan UK LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 8 and 9 March 2023

Further written submissions received: 17 March, 30 March and 5 April 2023

Draft judgment circulated to the parties: 11 May 2023

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- The Claimant, Port de Djibouti SA ("PDSA") brings this jurisdictional challenge under section 67 of the Arbitration Act 1996, in respect of certain determinations made by Professor Dr Maxi Scherer, sitting as a sole arbitrator, in her final partial award of 7 July 2021 (the "Award"). The arbitration was seated in London and conducted under the 2014 LCIA Rules.

- On PDSA's case, the jurisdiction issue arises from the arbitrator's determination that, on the proper construction of the arbitration agreements, PDSA remained a "Shareholder" (under the applicable contract terms) in the parties' joint venture company, Doraleh Container Terminal S.A. ("DCT"), after a Presidential Ordinance of 9 September 2018 by which the Republic of Djibouti ("the Republic") took ownership of PDSA's shares in DCT.

- In brief outline, PDSA submits that:

- Again in brief outline, the Defendant DP World Djibouti FZCO ("DP World") submits that:

- I have concluded that the arbitrator did have jurisdiction in relation to all the matters she dealt with, and that PDSA's claim must therefore be dismissed.

- PDSA is a Djiboutian company and legal successor to Port Autonome International de Djibouti ("PAID"). As of 14 November 2016, 76.5% of its shares were indirectly owned by the Republic.

- DP World is a UAE company which operates ports in various countries.

- In 2004 the Republic granted DP World the exclusive right inter alia to develop, build and operate a container terminal in the port of Dolareh, Djibouti (the "Terminal").

- DCT, a Djiboutian company, was established in 2006 to hold the rights to develop and operate the Terminal. PAID and then PDSA held 66.66% of the shares in DCT and DP World held the remaining 33.34%.

- On 30 October 2006, DCT entered into a 30-year concession agreement with the Republic to develop and operate the Terminal (the "Concession Agreement").

- As recorded in the Award , various contracts were concluded in 2007 to progress the venture. On 22 May 2007, the Republic, DCT and PAID entered into a Port Services Agreement. Also on 22 May 2007, PAID and DP World (but not the Republic) entered into the two contractual instruments in issue in these proceedings, namely the JVA and the Articles.

- According to DP World at least, although it was the minority shareholder in the joint venture, it was agreed and insisted upon by the international financial institutions financing the construction of the terminal that DP World would have the right to appoint a majority of the directors on the board of DCT, so that it (rather than the Republic) would control and manage DCT. Those and other protections were expressly incorporated into the JVA and Articles; and, in order to ensure that they were preserved, both contracts also incorporated detailed share transfer provisions, including a requirement that any transferee of shares enter into a deed of adherence binding it to the terms of the JVA.

- The JVA and the Articles are governed by Djibouti law. However, it is common ground that on this jurisdictional challenge, the court is to apply English principles of interpretation on the basis that PDSA did not invoke any principles of Djiboutian law in its Part 8 arbitration claim form and indicated in its responsive evidence that it was not itself relying upon any principles of foreign law (as recorded in a judgment of HHJ Pelling KC dated 30 March 2022).

- Clauses 19 and 20 of the JVA include the following provisions:

- Article 52.1 of DCT's Articles of Association states:

- Clause 1.2 of the JVA defines the term "Shareholders" as follows:

- A series of provisions in the JVA refers to the concept of 'holding' shares. For example, the definition of "Government Shareholders" indicates that it means PAID and its transferees "so long as they may hold Shares in the Equity Share Capital" of DCT, and the "Government Shares" are defined to mean "the Shares held by the Government Shareholders in the Equity Share Capital of [DCT] from time to time".

- The "Parties" to the JVA were defined as "PAID, DPW Djibouti, the Company and any other Persons who may become parties to this Agreement by the execution of a Deed of Adherence ".

- The JVA provisions on share transfers, which I consider in more detail in section (H) below, include the following:

- Article 5A.1.xxviii of the Articles similarly defines "Shareholders" as:

- The definitions in JVA and the Articles are expressed to apply "unless repugnant to the context of their usage".

- Article 11, dealing with transfers of shares, includes the following provisions:

- The recitals to the prescribed form of deed of adherence, in JVA Annexure 4, contemplate that the deed will be entered into before the proposed share sale and purchase occurs.

- It appears that relations between the parties subsequently soured. DP World complains that since 2013, by a series of measures including the events precipitating the arbitration, the Republic and PDSA have sought to oust DP World from its role in managing the terminal without compensation, renege upon the terms of the contracts in place between the two sides, and grant rights over the terminal to a Chinese rival of the group of which DP World forms part (and, as of 2012, minority shareholder in PDSA) in breach of those contracts.

- On 28 July 2018 PDSA purported to terminate the JVA with immediate effect, on the alleged basis that DP World had failed to act in the best interests of DCT.

- By a letter dated 8 August 2018, PDSA called for an extraordinary general meeting of DCT's shareholders to remove the DP World-appointed directors from the board.

- DP World on 31 August 2018 obtained without notice injunctive relief from this court (Bryan J), inter alia restraining PDSA from treating the JVA as terminated and from voting in favour of the removal of DP World's directors from DCT's board.

- On 5 September 2018 DP World commenced the arbitration, claiming inter alia that PDSA's purported termination was unlawful and of no legal effect (the "JVA Termination Claim").

- The Presidential Ordinance was issued four days later, on 9 September 2018. It stated:

- A press release issued by the Republic the following day explained that the purpose of the Presidential Ordinance was to ensure that "the DCT company cannot under any circumstances 'come back' under the control of DP World DP World's 'strategy', which consists in trying to oppose the will of a sovereign state, is both unrealistic and destined to fail".

- The Presidential Ordinance was ratified by the Djiboutian Parliament (a constitutional requirement) on 28 October 2018 by "Law 29", the provisions of which were expressed to be backdated to apply "as of 09 September 2018".

- The change in ownership effected by the Presidential Ordinance was apparently registered in the Djiboutian Company Register on 17 October 2018 (although the document stating this was itself dated 6 August 2019). No share transfer was recorded in DCT's share register.

- At the return date hearing on 14 September 2018 (at which PDSA did not appear), DP World sought and obtained from Teare J the continuation of the interim injunction granted by Bryan J the previous month. The injunction was continued on terms that restrained PDSA and its "Affiliates" (as that term was defined in the JVA and Articles, which extended to the Republic) from taking any steps to effect a transfer of shares in DCT in the absence of a deed of adherence.

- Following the Presidential Ordinance, DP World amended its Request for Arbitration inter alia to advance further claims that PDSA (i) remained a shareholder in DCT notwithstanding the Presidential Ordinance (the "Share Transfer Claim"), and (ii) had breached various provisions of the JVA and Articles, in particular by reason of the Share Transfer (the "Breaches Claims", referred to in the arbitration as the "JVA and Articles Breaches Claims").

- The substantive relief which DP World sought in the arbitration, by way of partial award, was encapsulated in §§ 231 and 232 of its Reply. I quote those paragraphs below with definitions interpolated for ease of reference:

- The alleged breaches involved in the Breaches Claim were listed in § 64 of DP World's written opening in the arbitration, which stated:

- PDSA raised a partial jurisdictional objection that the arbitrator had no jurisdiction over claims arising from allegations of breach occurring after the Presidential Ordinance on 9 September 2018 because it ceased to be a Shareholder on that date.

- In its Rejoinder, for example, PDSA said:

- The Award recorded inter alia that:

- A 3-day hearing took place in January 2021, covering all of the issues (both in relation to jurisdiction and merits) raised in the parties' statements of case. During the course of Day 1, counsel for PDSA said:

- At the end of Day 1, following PDSA's oral opening, the arbitrator specifically asked PDSA's counsel by reference to the "Relief Sought" section of DP World's Reply quoted above to which claims PDSA advanced an objection to jurisdiction. The arbitrator said, "what I would like to do is make sure that for every claim of [DP World] I understand whether or not there is actually a jurisdictional objection or not". The first two exchanges between the arbitrator and PDSA's counsel were then set out in the Award, in subsections headed "Tribunal's Jurisdiction", in the parts of the Award dealing with the JVA Termination Claim and the Share Transfer Claim (Award §§ 216 and 403).

- In relation to the JVA Termination Claim the following exchange was recorded:

- In relation to the Share Transfer Claim, the following exchange was recorded:

- It will be noted that when putting this question the arbitrator did not read out the last eight words of § 231(d) of DP World's Reply, "and that PDSA remains a shareholder of DCT".

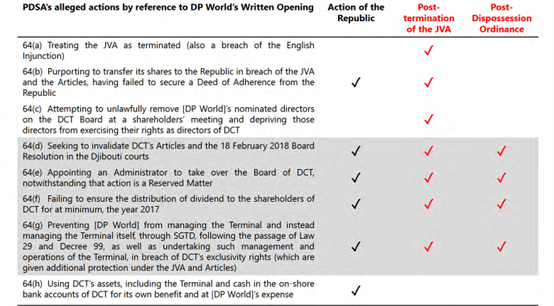

- In relation to the JVA and Articles Breaches Claims, the exchange between the arbitrator and PDSA's counsel referred to a slide in which PDSA had listed the alleged breaches set out in § 64 of DP World's written opening (quoted above) and indicated, by a red tick in the right-hand column, which of them PDSA said post-dated the Presidential Ordinance and thus fell outside the arbitrator's jurisdiction. The slide was as follows:

- The exchange between counsel and the arbitrator was:

- As noted later, DP World was in fact unsuccessful on the merits in relation to the alleged breaches listed as 64(d), (e), (f) and (g) in its written opening and in PDSA's slide.

- In the Award, which addressed issues of both jurisdiction and merits, the arbitrator substantially upheld the JVA Termination Claim, the Share Transfer Claim and (in part only) the Breaches Claims. I quote below the relief granted in Section VI of the Award, with definitions incorporated for ease of reference:

- The arbitrator's essential conclusions leading to this relief can be summarised as follows.

- After setting out in detail the relevant events and the parties' contentions, the arbitrator analysed the JVA Termination Claim in section E of her Award. She found that the purported termination of 28 July 2018 was unlawful, and declared that the JVA remained valid and binding (Award §§ 352 and 395, and section VI § (b)). As recorded in Award § 216, there was no jurisdictional challenge to this claim, which related to matters pre-dating the Presidential Ordinance.

- The arbitrator dealt with this claim in section F of her Award (§§ 396 to 463), addressing DP World's claim for a declaration that:

- As to jurisdiction, the arbitrator noted that "the Respondent's jurisdictional challenge only concerns claims post-dating the 9 September 2018 Share Transfer, whereas the Share Transfer Claim concerns the Share Transfer that occurred on 9 September 2018", quoting the exchange which I quote in § 43 above, and concluded that the jurisdiction challenge therefore did not affect the arbitrator's jurisdiction, as such, to hear the Share Transfer Claim (Award §§ 403 and 404).

- The arbitrator then considered an argument raised by PDSA based on the act of state doctrine, concluding that the doctrine was not engaged because:

- Under the heading "Share Transfer and Breach of JVA and Articles", the arbitrator concluded that the JVA and the Articles made signature of a deed of adherence a necessary pre-condition of any share transfer (Award § 433) and that the share transfer in the present case was in breach of JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7 of DCT's Articles of Association (Award § 444).

- The arbitrator then proceeded to consider the legal consequences of the fact that the share transfer breached the share transfer restrictions in the JVA and the Articles. She concluded that, pending a signed deed of adherence, PDSA was still deemed to be a shareholder in DCT for the purposes of the JVA and the Articles. It is appropriate to set out in full these paragraphs of the Award:

- As discussed in section (F) below, PDSA argues that the arbitrator's conclusion that it remained a shareholder in DCT (i) was a jurisdictional finding and (ii) was incorrect.

- In section G of the Award (§§ 464-544), the arbitrator considered DP World's Breaches Claims.

- As to jurisdiction, the arbitrator said:

- As to the merits, the arbitrator rejected the Breaches Claims, other than DP World's claim that the JVA and Articles were breached because the share transfer (which the arbitrator defined as "[t]ransfer of [PDSA's] shareholding interest in DCT to the Republic pursuant to the Presidential Ordinance") lacked the required deed of adherence. She considered that claim in Award §§ 481-502.

- In the light of the arbitrator's previous findings, the only live defences PDSA could put forward to this claim were that (i) the requirement to sign a deed of adherence was an obligation imposed on the transferee (the Republic) not the transferor (PDSA), and (ii) the Presidential Ordinance was a force majeure event excusing PDSA from liability. As to those defences, the arbitrator concluded that:

- As discussed in section (G) below, PDSA argues that the arbitrator lacked jurisdiction to make these findings because (i) they included findings of breach post-dating the Presidential Ordinance, (ii) the effect of the Presidential Ordinance was (contrary to the arbitrator's earlier findings) that PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder and (iii) the alleged breach thus fell outside the scope of the arbitration agreements.

- PDSA accepts that the arbitrator had jurisdiction to decide that the share transfer effected by the Presidential Ordinance constituted a breach of Clause 14.5 of the JVA and Article 11.7 of the Articles since no deed of adherence was signed by the Republic (Award §§ 433 and 443-444), i.e. that the share transfer effected through the Presidential Ordinance on 9 September 2018 was in itself a breach of contract. PDSA states that, as a matter of ratione temporis analysis, that was a matter that did not post-date PDSA ceasing to be a "Shareholder", so (as recorded in the Award at §§ 402-404) PDSA did not take jurisdictional objection to it.

- However, PDSA submits that the arbitrator lacked jurisdiction to decide, in the second part of her analysis of the Share Transfer Claim, that it remained a Shareholder after the Presidential Ordinance, because:

- I consider point (i) above in section H below. However, points (ii) and (iii) are logically prior, in the sense that they raise the question of whether or not the arbitrator's jurisdiction over this part of the Share Transfer Claim is contingent on PDSA actually having remained a Shareholder after the Presidential Ordinance.

- DP World's submission, in essence, is that it is not so contingent: the question of whether PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder is a "dispute between the Shareholders" within the scope of the arbitration agreements regardless of whether or not the answer to that question is yes or no.

- PDSA submits as follows:

- I do not accept those submissions.

- First, whether or not it is also a jurisdictional issue, the question of whether PDSA remained a Shareholder was a substantive issue between the parties, and had been one ever since the Presidential Ordinance was made. DP World's Amended Request for Arbitration dated 30 November 2018, following publication of the Ordinance, alleged that PDSA remained a Shareholder and remained contractually liable as such under the JVA and the Articles: see § 117, Section J and the relief sought in § 172(d) of the Amended Request. For example, § 136 stated that "[DP World's] position is that [PDSA] is bound by the provisions of the Articles and the JVA at all relevant times as a shareholder of DCT", and § 138 made clear that DP World disputed PDSA's stance to the contrary. Moreover, DP World's claim that PDSA remained a shareholder underlay DP World's substantive claims in section K of the Amended Request that PDSA was contractually liable for the Republic's subsequent actions after the making of the Presidential Ordinance.

- Secondly, the present case is not directly analogous with cases, such as contract formation cases and cases where an arbitration agreement has been terminated or revoked, where the actual or putative arbitration agreement may never have come into existence at all, or may have ceased to exist for all purposes. Nor are investor/state cases analogous: there, a claimant must establish that it is an 'investor' in order to be able to invoke at all the dispute resolution mechanism of a treaty to which it is a non-party. In the present case, there is no dispute that (i) the arbitration agreements did come into existence and (ii) those agreements did not cease to exist for all purposes if and when PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder. It is common ground that the arbitration agreements continued to apply to alleged breaches occurring before PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder. The current question is: to precisely which categories of matters do the arbitration agreements continue to apply, even if PDSA did cease to be a Shareholder upon issue of the Presidential Ordinance. The answer to that question has to be found in the parties' agreements, particularly the arbitration provisions themselves. That is a question of construction of the provisions, whether it be labelled a question of scope or a question of party consent. In this somewhat nuanced situation, I suspect that the metaphor of an arbitration 'shop' is not particularly instructive: but, if one does seek to apply it, then the position here is that (i) an arbitration shop has opened for business, (ii) it remains open, on any view, at least for some purposes, and (iii) in order to identify which those purposes are, it is necessary to construe the arbitration agreements which the parties have undoubtedly entered into.

- Thirdly, the question of whether the arbitrator had jurisdiction to decide whether PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder is certainly a jurisdictional question, on which the court has the final say. However, it does not follow that the substantive question of whether or not PDSA did cease to be a Shareholder is itself a jurisdictional question in that particular context. That depends on whether the arbitrator's jurisdiction to decide the issue was contingent on the answer, i.e. whether the arbitrator had jurisdiction to decide whether PDSA remained a Shareholder only if PDSA did (in the court's view, ultimately) remain a Shareholder.

- Fourthly, in my judgment the answer to the latter question is no, essentially for two reasons.

- Fifthly, the conclusions set out above do not require the arbitration agreements to be interpreted as including any special drafting of the kind referred to in § 66.vii) above. This is not a case of the parties having conferred on the arbitrator power to determine questions of party consent so as to confer on herself a jurisdiction that it would not otherwise have. On the contrary, the present issue concerns whether, in the court's view, the arbitrator had jurisdiction to decide the substantive question about whether PDSA had ceased to be a Shareholder, and whether any such jurisdiction was contingent on the answer to that question. In my judgment, the arbitrator did have such jurisdiction, and it was not contingent on the answer to the question. The arbitrator had such jurisdiction whether or not PDSA in fact (as ultimately found by the court) ceased to be a Shareholder upon issue of the Presidential Ordinance.

- Sixthly, I do not agree that the arbitrator herself treated the question of whether PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder as a jurisdictional issue in the context of the Share Transfer Claim. As summarised earlier, she treated it as the second limb of the Share Transfer Claim (the first being the alleged breaches of JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7), but still as a merits issue, which it was. The arbitrator treated the cessation question as a jurisdictional issue only in the context of the Breaches Claims, when she considered in Award § 471 her jurisdiction to address those claims.

- For these reasons, I conclude that the arbitrator had jurisdiction to determine the Share Transfer Claim, in all its aspects, regardless of whether PDSA did or did not cease to be a Shareholder upon the issue of the Presidential Ordinance.

- For completeness, I consider in section (H) below whether PDSA did cease to be a Shareholder for the purposes of the JVA and the Articles, concluding that it did not. This part of the jurisdiction challenge therefore fails on that ground too.

- In those circumstances it is not strictly necessary to address two further points which DP World made in this context, namely that (i) the arbitrator's conclusion about whether PDSA remained a Shareholder was no more than an aspect of the relief granted following her prior findings of breach, so that no section 67 jurisdiction question arises at all, and (ii) PDSA is estopped by those prior findings of breach from objecting to the arbitrator's conclusion, derived therefrom, that PDSA remained a Shareholder. Briefly, my views on those two matters are as indicated below.

- On the first point (no section 67 issue arises), DP World submits as follows:

- I would not have accepted step (iv) in the above line of argument. I would agree that the question of whether PDSA remainder or ceased to be a Shareholder is closely linked to the question of whether PDSA was in breach of JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7, i.e. the matters on which the arbitrator made findings in the first section of her reasoning about the Share Transfer Claim. However, her conclusion that, in the light of those breaches, PDSA remained a Shareholder was nonetheless a distinct substantive legal conclusion about the parties' rights, obligations and status, which depended in part on the further steps in the arbitrator's reasoning set out in Award §§ 460 and 461. As I have indicated earlier, the question of whether PDSA remained a Shareholder was in itself one of the substantive matters referred to the arbitrator for decision, and I would have concluded that it was a "matter" submitted to arbitration within sections 30 and 67 of the Act.

- PDSA also submitted that its challenge raised a question about whether there was a valid arbitration agreement, within section 30(1)(a). There undoubtedly was, and remains, a valid arbitration agreement in the present case. However, to the extent that questions about whether a dispute falls within the scope of an arbitration agreement can, at least on one view of the taxonomy of section 30, be regarded as falling within s. 30(1)(a) rather than s. 30(1)(c) (see Obrascon Huarte Lain v Qatar Foundation [2020] EWHC 1643 (Comm) § 19 and NDK Ltd v Huo Holding § 22), a challenge to the arbitrator's jurisdiction over the question of whether PDSA remained a Shareholder might alternatively be regarded as raising a section 30(1)(a) issue.

- On the second point (estoppel), DP World submits that as part of the first limb of the Share Transfer Claim, to which no jurisdictional objection was made, the arbitrator found that "both the JVA and Articles make the signature of a deed of adherence a necessary pre-condition of any share transfer", and that as that pre-condition had not been satisfied, "the Share Transfer in the present case was in breach of Clause 14.5 of the JVA and Article 11.7 of the Articles" (Award §§ 433 and 444). Those determinations are, in consequence res judicata. It is a legal nonsense to suggest that the arbitrator nonetheless lacked jurisdiction to decide on what were, in her words, "the legal consequences of the breach of the share transfer restrictions contained in Clause 14.5 of the JVA and Article 11.7 of the Articles" namely that PDSA remained a Shareholder. Thus in substance PDSA is seeking to obtain a reversal of the arbitrator's binding findings on the question of breach.

- I would not have accepted that submission. As noted above, though closely connected with the question of breach, the impact on PDSA's status as a Shareholder was a further substantive question. It was in principle open to PDSA, whilst bound by the findings of breach of JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7, to argue that they did not have the legal consequence which the arbitrator found, and (had grounds for such an objection existed) to challenge the arbitrator's jurisdiction to determine that issue.

- I consider later, in section G below, whether an estoppel could arise from the arbitrator's finding that PDSA remained a Shareholder.

- PDSA contends that at Award § 500, the arbitrator found that PDSA was in breach of Article 14.5 of the JVA and Article 11.7 of the Articles for failing to obtain the Republic's signature to a deed of adherence after the Presidential Ordinance. PDSA submits that the arbitrator lacked jurisdiction to determine that issue, because it related to a matter occurring after PDSA ceased (by reason of Presidential Ordinance) to be a Shareholder.

- PDSA says the fact that the arbitrator's findings include events post-dating the Presidential Ordinance is clear from the last sentence of Award § 500: "It clearly could have done so, even in the light of the Presidential Ordinance ". Moreover, it had been DP World's case that PDSA was in breach both before and after the Presidential Ordinance: see, e.g., DP World's Reply at § 164 ("PDSA was contractually obliged to procure the signing of a Deed of Adherence by any transferee. Undeniably, it failed to do so before purporting to transfer its shares to the Republic") and § 175 ("PDSA does not deny that it breached its obligation under the Articles and the JVA in failing to procure the signing of a Deed of Adherence by the Republic following the attempted transfer on 9 September 2018"). PDSA's Rejoinder indicates that it understood DP World's case in the same way, contending for example that any post-Ordinance breach was excused by Presidential Ordinance as a force majeure event (an argument which the arbitrator rejected on the facts, as noted earlier).

- I quote Award §§ 500-502 below in full including the footnotes:

- The arbitrator thus restated her finding of breach in the first sentence of § 500, by reference (as footnote 514 indicated) to her findings in Award §§ 442-444. In those paragraphs, the arbitrator held that (a) JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7 required the transferee to sign a deed of adherence, (b) "It is uncontested that, in the case at hand, no such deed of adherence was signed or provided by the Republic", and (c) that failure was not cured by the Republic's subsequent public claims to be a shareholder in DCT.

- DP World argues that the finding of breach restated in the first sentence of Award § 500 referred to the breach committed as at the date of the Presidential Ordinance (as to which no jurisdiction objection was or is taken), and that the last sentence of § 500 did not find any new breach but merely stated that PDSA had not cured the original breach. Similarly, § 502 in substance merely cross-referred to the findings made in §§ 442-444.

- In my view, Award § 500 indicates that the arbitrator found there to be a single breach ("this contractual breach") which began when PDSA failed to procure a deed of adherence by the time of the Presidential Ordinance and continued thereafter. The analysis of force majeure and, in particular, the statement that PDSA could still have procured a deed of adherence "even in the light of the Presidential Ordinance", make little sense unless the arbitrator was concluding that the breach continued after the date of the Ordinance.

- However, I do not consider that the arbitrator lacked jurisdiction for that finding, for three reasons.

- First, even if PDSA did cease to be a Shareholder upon issue of the Presidential Ordinance, the finding of a breach that began on or before the date of the Ordinance and continued thereafter was still a "dispute between the Shareholders" for the purposes of the arbitration agreements. The general considerations referred to in §§ 71.i)(b) and 71.ii) above apply again here. The breach commenced, on any view, while PDSA remained a Shareholder; and its continuation after the date of the Ordinance (even if PDSA thereupon ceased to be a Shareholder) remained at least "connected with" a breach that occurred while PDSA remained a Shareholder, and remained a "dispute between the Shareholders" within the arbitration clauses. A rational businessman would not expect a claim relating to the breach's initial occurrence, but not a claim regarding its continuation, to be subject to arbitration .

- Secondly, I conclude in section (H) below that PDSA did not cease to be a Shareholder for the purposes of the JVA and the Articles. This part of the jurisdiction challenge therefore fails on that ground too.

- DP World advanced a third reason why the PDSA's jurisdiction challenge in relation to the Breaches Claim should fail, namely that PDSA is estopped by the arbitrator's findings on the Share Transfer Claim.

- DP World's initial contention was that PDSA is issue estopped by the arbitrator's findings, in the first part of her consideration of the Share Transfer Claim, that the transfer involved breaches of JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7. However, I agree with PDSA that that point would not assist, because those findings did not in and of themselves amount to a finding that PDSA remained a Shareholder: it is only the arbitrator's further finding, in the second part of her analysis, that PDSA remained a Shareholder that directly bears on the jurisdiction challenge regarding the Breaches Claims.

- I raised with the parties the question of whether an issue estoppel could arise, in the context of the Breaches Claim, from the arbitrator's conclusion (when considering the substantive merits of the Share Transfer Claim) that PDSA remained a Shareholder, if that finding was itself within the arbitrator's jurisdiction. I have concluded in section (F) above that the arbitrator's conclusion that PDSA remained a Shareholder following the Presidential Ordinance was within her jurisdiction, and that she had jurisdiction to reach a conclusion on that issue regardless of whether PDSA did or did not in fact (ultimately in the court's view) remain a Shareholder. I have also already concluded that the arbitrator's finding that PDSA did remain a Shareholder was a finding on the merits, even though the arbitrator also treated it as a jurisdictional finding in the context of the Breaches Claims. The parties are, DP World submits, bound by that conclusion, even in the context of the jurisdictional issue concerning the Breaches Claim.

- DP World refers to the decisions in Westland Helicopters Ltd v Al-Hejailan [2004] 2 Lloyd's Rep 523 and C v D1 [2015] EWHC 2126 (Comm). In Westland Helicopters, Westland argued that an arbitrator had no jurisdiction to award interest because (i) he had no jurisdiction to award any principal sum calculated by reference to a notional annual retainer; and (ii) there being no jurisdiction in respect of (i), there could be no jurisdiction to award interest on that impermissible principal sum (§ 30). However, Westland had not challenged the arbitrator's jurisdiction to resolve the dispute by reference to a notional annual retainer, so his decision to that effect was binding on the parties (§ 33). Accordingly, Colman J stated:

- In C v D1, the claimant sought to challenge an arbitral tribunal's conclusion that it had jurisdiction under the arbitration clause in a contract (the SPA) to determine claims arising from alleged breaches by the claimant of an earlier contract (the PSC). The tribunal decided:

- DP World submits that those two cases show that a section 67 challenge cannot be used as a means of attacking a prior merits decision which was itself within the tribunal's jurisdiction, or in respect of which jurisdiction was not objected to or challenged.

- The situation in the present case is not completely analogous to that in Westland Helicopters or C v D1. In both of those cases, the finding by which the claimant was held to be bound (even in the context of a jurisdiction challenge) was a pure merits finding to which no jurisdiction objection had been taken at all. In the present case, the arbitrator's conclusion that PDSA remained a Shareholder (a) is the subject of a jurisdiction challenge, at least before this court, and (b) was regarded by the arbitrator as a jurisdictional finding in relation to the Breaches Claims.

- However, I do not see why the underlying principle should not equally apply here. If an arbitrator has made a finding on a substantive issue between the parties, it is difficult to see why its binding effect in the context of a jurisdiction challenge to some other part of the arbitrator's award should depend on whether (a) no jurisdiction objection has ever been made to the finding on the substantive issue or (b) there has been a challenge but the court has concluded that the arbitrator had jurisdiction. Either way, the arbitrator has made a finding on an issue between the parties that the arbitrator had jurisdiction to determine. In principle one would expect that finding to be binding for all purposes, following the logic of the two cases discussed above, even if the finding also has relevance to a jurisdiction issue (regarding some other part of the case) which prima facie would ultimately be for the court to determine.

- PDSA submits that (i) the arbitrator's finding that PDSA remained a Shareholder was a purely jurisdictional one, and (ii) alternatively, if it went to both merits and jurisdiction, then it was a 'doubly relevant' fact that there needed to be asked twice, citing The Newcastle Express §§ 74 and 75. I have already quoted § 75 of that case, but for ease of reference I quote both paragraphs below:

- I do not accept PDSA's submission that the above considerations are relevant to the issue in the present case. They indicate, in brief, that (a) the question of whether an arbitration agreement has been formed and subsists is in principle separate from the question of whether the substantive contract has been formed and exists, though (b) in some cases, the same factual issue will be relevant to both questions, for example where the question is whether any contract was executed at all or whether a purported contract is vitiated by forgery or lack of mental capacity. However, such cases are unlikely to involve the situation arising in the present case, where the arbitrator has made a finding on the merits, which the court concludes was made within his/her jurisdiction, but which also has a bearing on the arbitrator's jurisdiction over some other aspect of the dispute. Nothing in The Newcastle Express touches on any such question.

- It is very likely, in a contract formation case, that the jurisdiction issue will be whether the arbitrator had any jurisdiction at all in respect of the dispute. That was the situation in The Newcastle Express, where the court concluded that the charter was 'fixed on subjects', which were never lifted, meaning that the parties never formed the intention to create legal relations with respect to the envisaged contract, including the arbitration agreement that would have formed part of it.

- In the present case, by contrast, it is common ground that an arbitration agreement was made and subsisted at least for certain purposes, and I have concluded that those purposes included determination of the question of whether PDSA remained a Shareholder. The arbitrator's finding on that question accordingly fell within her jurisdiction, and, as it appears to me (following Westland Helicopters and C v D1), binds the parties both as a finding on the merits and as a finding relevant to the arbitrator's jurisdiction to determine the Breaches Claims. That constitutes a further reason why the arbitrator did have jurisdiction to determine the one Breaches Claim on which she found in DP World's favour.

- In the preceding sections of this judgment, I have concluded that the arbitrator had jurisdiction to determine both limbs of the Share Transfer Claim and the one Breaches Claim on which she upheld DP World's claim, regardless (in both cases) of whether PDSA did or did not in fact remain a Shareholder once the Presidential Ordinance had been issued.

- In this section, I consider for completeness whether PDSA did remain a Shareholder following the issue of the Ordinance. For these purposes I accept PDSA's submissions that:

- I have cited the basic provisions of the JVA and the Articles relevant to shareholders and share transfers in section (B)(3) above. PDSA's submissions may be summarised as follows.

- First, the JVA distinguished "Parties" to the JVA from "Shareholders". The "Parties" were defined as named entities and any subsequent party who signed a deed of adherence:

- By contrast the definitions of "Shareholder" in both the JVA and the Articles, quoted earlier, imposed a further attribute, namely an ownership requirement. They referred, respectively, to "shareholders in the Equity Share Capital of the Company" and "subscribers holding Shares in the Capital of the Company". Unless contractually provided otherwise, an entity cannot be a "shareholder[] in Equity Share Capital" or "hold[] Shares" without owning shares in the company. (The terms "Equity Share Capital", "Shares" and "Capital" were also defined: "Equity Share Capital from time to time, shall mean the total issued share capital of the Company" (JVA § 1.2); "Shares means the issued equity shares of par value FD 25,000 per share in the Capital of the Company, whether they be DPW Shares or Government Shares" (Article 5A.1.xxxi); and "Capital from time to time, shall mean the total issued Share capital of the Company") (Article 5A.1.vi ).)

- Likewise, the definitions of "Shareholder" refer to the "Person[s] to whom Shares are issued or Transferred". An entity which receives shares pursuant to a share issue or a share transfer will own those shares.

- These points were re-emphasised at the end of each definition, which stated that an entity's status as a "Shareholder" continues only "while any Shares are held by such Persons".

- The definitions of "Government Shareholders" and "DPW Shareholders" in the JVA and the Articles are also consistent with a contractually stipulated property ownership requirement. They provide that listed entities will only be (DPW/Government) "Shareholders" "so long as they may hold Shares in the [Equity Share] Capital of the Company".

- These provisions are also consistent with the provision in JVA § 19.1 that "a Shareholder will cease to have any further rights or obligations under this Agreement on ceasing to hold any Shares ".

- Thus in order to be a "Shareholder", it was necessary to own equity in DCT's share capital. Following the Presidential Ordinance, PDSA no longer satisfied that requirement (as held by the arbitrator) and was therefore not a "Shareholder".

- Secondly, the JVA and the Articles define "Transfer" as follows:

- Consistently with that definition, the JVA envisages various types of "Transfers", including:

- Thirdly, and further to the above, whilst the parties could contractually dictate who were to be treated as "Parties" by dictating that such an entity would have to sign a deed of adherence (which is what the arbitrator found) and could dictate the timing of the transfer of ownership in such a scenario, they could not dictate in a situation of automatic, immediate and compulsory transfer by law the timing of the transferring of ownership in the equity. The arbitrator expressly recognised this in accepting that:

- Fourthly, the provisions in the definitions of "Shareholder", JVA § 14.5 and Article 11.7 that make any Transfer conditional upon execution by the transferee of a deed of adherence are concerned with the question of whether the transferee becomes a Shareholder. They do not, and could not, prevent a shareholder who loses ownership of its shares by compulsory transfer from thereby ceasing to be a Shareholder.

- Fifthly, JVA §§ 14.6(a) and (d), and the corresponding provisions in Articles 11.2, 11.8(i) and 11.8(iv), are concerned with registration on the share register and ensuring compliance with the second component of the definition of Shareholder, viz execution of a deed of adherence. They do not affect the first component, namely that a Shareholder must actually own the shares in question.

- Sixthly, the arbitrator concluded that PDSA was "deemed" to remain a Shareholder. However, the only deeming provision in the JVA has no application to the present case (and there was no attempt by the arbitrator to explain how it could possibly apply). Clause 14.6(c) provides:

- However, that provision is by its own plain terms incapable of applying to an immediate, automatic and non-voluntary transfer of ownership by operation of law to divest ownership, with PDSA having no control over the transfer or its timing: because such a transfer did not involve a person "executing an instrument of transfer" (the "Transfer" had already happened). Indeed, the arbitrator correctly found that the Presidential Ordinance would necessarily override any inconsistent provision in the agreements. In other words, in such a non-contractual situation, the parties recognised in the JVA that they could not regulate the timing of the transfer of share ownership with the signing of a deed of adherence. The JVA specifically contemplated this situation by defining "Transfers" to go beyond any form of voluntary or contractual transfer but to include an immediate, automatic and compulsory transfer of shares.

- By including the 'deeming' provision in Article 14.6(c), the parties recognised that they were altering though only in respect of voluntary Transfers the position that would otherwise prevail, namely that following a transfer a shareholder would cease to be a Shareholder (as defined) because it would no longer own shares in the company.

- Thus, in a situation of compulsory automatic transfer:

- Seventhly, there is nothing commercial surprising about a result in which an entity that has involuntarily been deprived of its shares should cease to incur the liabilities of a Shareholder and party to the contracts.

- For all these reasons, PDSA submits, the arbitrator was wrong to assume that the fact that the Republic did not become a Shareholder meant that PDSA remained a Shareholder.

- In my view, PDSA's analysis of these provisions is incorrect. In simple terms, I consider that the contractual regime is designed to, and does, have the effect that unless and until a deed of adherence has been executed, the original shareholder remains a Shareholder and subject to the duties thereby arising.

- By way of context, I note that the share transfer provisions in both the JVA and the Articles stated that the restrictions on Transfer in § 14 and Article 11 respectively "are serious and are for the protection of the legitimate interests of [all the Shareholders and] the Company". Requirements for any transferee to enter into a deed of adherence are a well-established feature of shareholders' agreements in order to "ensur[e] continuity": see, e.g., NDK Ltd v Huo Holding Ltd (No. 1) [2022] EWHC 1682 (Comm) at § 42(v)(a) and NDK v Huo (No. 2) [2022] EWHC 2580 (Comm) § 16.

- It is also significant that JVA § 14.5 makes a deed of adherence "a condition of any transfer of Shares" and Article 11.7 makes it "a condition of any Transfer of Shares", whether permitted or required. The use of the defined term "Transfer", at least in Article 11.7, which includes transfers by operation of law, confirms that the deed of adherence condition applies to such transfers too; and that is reinforced by the stipulation in Article 11.2 that any "Transfer" of shares is subject to JVA § 14, and by the stipulations in JVA § 14.1(b) and Article 11.3(ii) that the restrictions in JVA § 14 and Article 11 respectively apply both to conventional transfers and to transfers by operation of law.

- Further, JVA § 14.6(a), Article 11.2 and Article 11.8(i) have the effect that the directors must not register any transfer unless that condition has been fulfilled. It follows that the entity whose shares have purportedly been transferred must remain the registered shareholder.

- The clear effect and intention of these provisions is that, for the purposes of the JVA and the Articles, the shares are not to be regarded as having been transferred until a deed of adherence has been executed; and that unless and until that occurs, the original shareholder will remain the Shareholder: thus preserving continuity and avoiding the peculiar results of (a) there being no counterparty to the JVA and (b) for the purposes of the JVA and the Articles, the shares purportedly transferred having no holder at all.

- I do not consider that view to be inconsistent with the definitions of Shareholder. Those definitions themselves emphasise the importance of a deed of adherence upon any transfer. The words "while any Shares are held by such Persons" simply express the point that once an entity has transferred away all of its shares, in accordance with the JVA/Articles, it will then cease to be a Shareholder. They do not import any additional requirement of share ownership as a matter of property law; nor do they mean that one can be regarded as ceasing to 'hold' shares even though the JVA and Articles require the directors to refrain from registering any transfer. Nor do the words "shareholders in the Equity Share Capital of the Company" import any such additional requirement. The existence or otherwise of a shareholding is to be assessed applying the detailed provisions of JVA § 14 and Article 11.

- The conclusion above is also not inconsistent with the arbitrator's acceptance that the Presidential Ordinance overrode the provision in Article 11.2 that any Transfer in contravention of the restrictions shall be "void". It was the validity of the Presidential Ordinance "and the transfer of ownership resulting from it" which the arbitrator concluded she could not question (Award § 458). However, the Presidential Ordinance did not alter the parties' agreements as to the circumstances in which any Transfer of shares would or would not be regarded contractually as altering Shareholder status for the purpose of the JVA and the Articles.

- I do not agree that JVA § 14.6(c) implies that a person whose shares have been transferred by operation of law, rather than by execution of an instrument of transfer, ceases to be a Shareholder. In my view, that provision simply spells out one consequence of the effect of the other provisions I have referred to above, making clear that even where an instrument of transfer has been executed, that does not in itself alter the shareholding: the transferor remains the Shareholder until the transferee has been registered.

- PDSA submits that its approach is consistent with JVA § 3, which did not condition the (original) Parties to the JVA becoming "Shareholders" on the registration of their shareholding. Instead, once the DCT Board had issued a resolution issuing the Shares to the Parties, they became "Shareholders". I disagree. JVA § 3.1(b)(1)-(3) provided for the Board to allot shares to "the Government Shareholders" and the "DWP Shareholders" (as already defined) and then for a shareholders' meeting to pass resolutions inter alia that shares should be allotted to DP World and PAID, and that "[t]he names of such allottees shall be entered in the register of members as the holders of the number of Shares allotted to them respectively". If anything, that provision underlines the importance of registration.

- PDSA also suggested (in oral reply submissions) that JVA § 14.2(f) was at least consistent with its approach:

- PDSA suggested that § 14.2(f) contemplates a "Transfer" taking place, followed by a deed of adherence, indicating that a party could cease to be a Shareholder before a deed of adherence is executed, but for the deeming provision in § 14.6(c) (which, as noted earlier, does not apply to transfers by operation of law). However, that suggestion simply begs the question of whether, upon the "Transfer" referred to in § 14.2(f), the transferring Government Shareholder would immediately cease to be a Shareholder. Nothing in the contractual provisions in my view points to that conclusion.

- Equally, I do not consider that JVA § 19 assists PDSA. It begs the question of whether PDSA did cease to be a Shareholder. In my view, it did not.

- For these reasons, I do not consider that PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder for the purposes of the JVA and the Articles (including their arbitration clauses) by reason of the Presidential Ordinance.

- DP World submits that PDSA has lost the right to pursue its challenge, because the arbitrator gave PDSA an express opportunity to clarify the extent to which it advanced any jurisdictional objection to DP World's claims and the relief it sought in respect thereof; and PDSA not only failed to object, but in fact positively confirmed that it was advancing no challenge to the three claims that succeeded, nor the relief sought in relation to them.

- Pursuant to section 73(1) of the Arbitration Act:

- In National Iranian Oil Company v Crescent Petroleum Company International Limited [2022] EWHC 2641 (Comm) Butcher J, after reviewing the authorities, provided the following helpful summary of the principles:

- The emphasis upon fairness and efficiency was also reflected in the Departmental Advisory Committee report that preceded the Arbitration Act, which explained that:

- DP World relies on the exchanges with the arbitrator referred to in section (D) above. It submits that the relief granted by the arbitrator in relation to the JVA Termination Claim and the Share Transfer Claim was substantively identical to that sought by DP World as set out in § 231 of DP World's Reply, except that in relation to the Share Transfer Claim the arbitrator declined to declare the share transfer to have been "invalid". PDSA stated expressly to the arbitrator that it made no jurisdictional objection regarding either of those claims.

- Further, DP World says, the only one of the Breaches Claims that succeeded was that set out in § (d) of the operative part of the Award: "declares that the Respondent breached Clause 14.5 of the JVA and Article 11.7 of the Articles". That corresponded to the claim referred to in § 64(b) of DP World's written opening and its slide ("purporting to transfer its shares to the Republic in breach of the JVA and the Articles, having failed to secure a Deed of Adherence from the Republic"), as to which PDSA told the arbitrator it had no jurisdictional objection. It was not one of the four claims, marked with a tick, which PDSA submitted to the arbitrator were outside her jurisdiction. The arbitrator found against DP World on those four claims and awarded no relief in respect of them.

- In relation to the Share Transfer Claim, as I note in § 44 above, the arbitrator in the exchange quoted in § 43 above did not read out the final eight words of § 231(d) of DP World's Reply, "and that PDSA remains a shareholder of DCT". In those circumstances it is an overstatement, in my view, to suggest that PDSA positively indicated to the arbitrator that it made no jurisdictional objection to that part of DP World's claim. On the other hand, those words clearly formed part of DP World's claim, and PDSA did not distinctly or openly raise any jurisdictional objection to the claim for a declaration that it remained a Shareholder. I do not consider that PDSA was entitled to assume that the arbitrator deliberately omitted to read those words out because she recognised that PDSA challenged her jurisdiction to decide whether PDSA remained a shareholder.

- The fact that PDSA said it objected to jurisdiction in respect of "claims under the Articles against PDSA arising out of events that occurred after the Dispossession Ordinance" or "claims under the JVA after the passage of the Dispossession Ordinance" (as it was put in DP World's Rejoinder, quoted earlier) was not sufficient to indicate that it objected to jurisdiction over that part of the Share Transfer Claim. Nor is there any indication in the Award that PDSA challenged her jurisdiction to decide, as a substantive issue, whether it remained a Shareholder after the Ordinance. The fact that she understood her jurisdiction over some of the Breaches Claims to turn on the answer to that issue is not the same thing. If PDSA's position was that the question of whether it remained a Shareholder was itself a post-Ordinance event that the arbitrator lacked jurisdiction to decide, then it needed distinctly to say so.

- Consequently, I conclude that PDSA has, in any event, lost the right to object to the arbitrator's jurisdiction in respect of the whole of the Share Transfer Claim, including the question of whether PDSA remained a Shareholder after the Presidential Ordinance.

- The position in relation to the Breaches Claim is more finely balanced. The claim on which DP World succeeded was expressed in § 64(b) is one that occurred, once and for all, when the purported share transfer took place: "purporting to transfer its shares , having failed to secure a Deed of Adherence". On the other hand, it is part of PDSA's case on the present challenge that DP World's case included a failure to secure a deed of adherence after the date of the Presidential Ordinance. I have concluded that the arbitrator's findings are best regarded as being that a breach occurred at the moment of the Ordinance and continued thereafter. On balance, I consider that the reservations PDSA made clear to the arbitrator were sufficient to preserve any right to challenge jurisdiction, if and insofar as the arbitrator were to find that there was a breach post-dating the Presidential Ordinance, including a continuing breach commencing on that date.

- For these reasons, I conclude that the arbitrator had jurisdiction over all the matters she determined, and that the claim must therefore be dismissed.

Mr Justice Henshaw:

(A) INTRODUCTION

(B) BACKGROUND

(1) The parties and the key contracts

(2) The arbitration agreements

(3) Key provisions relating to shareholders and share transfers

(4) Subsequent events

(C) DP WORLD'S CLAIMS IN THE ARBITRATION

(D) PDSA'S JURISDICTION OBJECTION BEFORE THE TRIBUNAL

(E) THE TRIBUNAL'S CONCLUSIONS

(1) JVA Termination Claim

(2) Share Transfer Claim

(3) Breaches Claims

(F) JURISDICTION OVER THE SHARE TRANSFER CLAIM

(G) JURISDICTION OVER BREACHES CLAIMS

(H) WHETHER PDSA CEASED TO BE A SHAREHOLDER

(1) PDSA's submissions

(2) Analysis

(I) LOSS OF THE RIGHT TO OBJECT

(J) CONCLUSIONS

(A) INTRODUCTION

i) Presidential Ordinance No. 2018-001/PRE dated 9 September 2018 (the "Presidential Ordinance") immediately, automatically and compulsorily transferred to the Republic ownership of PDSA's shares in DCT. As was common ground before the arbitrator, under the applicable Djibouti law that meant that PDSA no longer owned equity in the share capital of DCT, such ownership having been vested in the Republic.

ii) The arbitration agreements in the parties' Joint Venture Agreement ("JVA") and in DCT's Articles of Association ("the Articles") were, by their terms, limited to disputes between "Shareholders".

iii) Under the contractual definitions, a person/entity could not be or remain a "Shareholder" unless it (a) actually owned equity in the share capital of DCT and (b) (unless it was an original signatory party to the JVA) had signed a deed of adherence and thereby agreed to be bound by the obligations of the JVA.

iv) Even though the Republic signed no deed of adherence, and therefore did not itself become a "Shareholder", PDSA ceased to be a Shareholder upon the Presidential Ordinance because it removed PDSA's equity ownership.

v) As a result, under the JVA terms, PDSA had no further rights or obligations under the JVA (including the arbitration agreement), save that it remained liable for any allegation of breach that occurred before it ceased to be a Shareholder (for which purposes the arbitration agreements would remain an applicable right and obligation).

vi) Consequently, the arbitrator had no jurisdiction to rule on contentions of contractual breach post-dating the Presidential Ordinance, nor on the question of whether PDSA remained a Shareholder thereafter. The arbitrator's contrary conclusion was a jurisdictional finding and was wrong.

i) It is undisputed that PDSA was a party to the arbitration agreements in the JVA and Articles, and that DP World validly commenced the arbitration against it by invoking those arbitration agreements.

ii) Properly analysed, PDSA has accepted that the arbitrator had substantive jurisdiction to determine the claims on which DP World actually succeeded in the Arbitration. Those include DP World's claim that the transfer of ownership effected by the Presidential Ordinance was made in breach of the JVA and Articles, both of which contained provisions stipulating that signature of a deed of adherence by the putative transferee (i.e. the Republic) was a "condition of any transfer of Shares".

iii) PDSA's challenge falls outside the scope of section 67, because it does not concern an issue going to the arbitrator's "substantive jurisdiction" (as that term is defined in the Arbitration Act). PDSA's real objection is not to the arbitrator's substantive jurisdiction but to the relief that the arbitrator awarded in respect of DP World's claims.

iv) In reality, what PDSA is in fact seeking to do is to challenge the arbitrator's findings on the merits of the dispute.

v) In any event, PDSA has lost the right to pursue its challenge, pursuant to section 73(1) of the Arbitration Act. PDSA was given the express opportunity by the arbitrator, before the Award was issued, to clarify the scope of the jurisdictional objection it pursued. Not only did PDSA fail to raise any objection to the claims on which DP World succeeded and the relief DP World sought in respect thereof, but it in fact positively confirmed that the arbitrator enjoyed jurisdiction.

vi) In any event, PDSA's challenge would fail as a matter of substance, because:

a) PDSA did not cease to be a Shareholder for the purposes of the JVA and Articles, despite the transfer of ownership to the Republic as a matter of property law; and

b) even if it did, the arbitrator retained jurisdiction to determine all the claims on which it found in DP World's favour, including the claim that PDSA remained a Shareholder following the Presidential Ordinance.

(B) BACKGROUND

(1) The parties and the key contracts

(2) The arbitration agreements

"19.1 This Agreement shall commence on the date of execution of this agreement and, unless terminated by the written agreement of the parties to it, shall continue for so long as two or more parties continue to hold Shares in the Company but a Shareholder will cease to have any further rights or obligations under this Agreement on ceasing to hold any Shares except in relation to those provisions which are expressed to continue in force and provided that this Clause shall not affect any of the rights or liabilities of any parties in connection with any breach of this Agreement which may have occurred before that Shareholder ceased to hold any Shares."

"20.1 In the event of any dispute between the Shareholders arising out of or relating to this Agreement, representatives of the Shareholders shall, within 10 Business Days of service of a written notice from any Shareholder to the others (a "Disputes Notice") hold a meeting (a "Dispute Meeting") in an effort to resolve the dispute. In the absence of agreement to the contrary the Dispute Meeting shall be held at the registered office for the time being of the Company."

20.3 Any dispute which is not resolved within 20 Business Days after the service of a Disputes Notice, whether or not a Dispute Meeting has been held, shall, at the request of either party made within 20 Business Days of the Disputes Notice being served, be referred to arbitration under the rules of London Court of International Arbitration ."

"All disputes which could arise during the course of the Company or its liquidation, either between the Shareholders themselves regarding the Company affairs, or between the Shareholders and the Company, are subject to arbitration, in accordance with the Rules of the International Court of Arbitration of London, the State and the artificial persons of Djiboutian public law, Shareholders of the Company expressly waiving any privilege of jurisdiction or enforcement."

(3) Key provisions relating to shareholders and share transfers

"Shareholders means:

(i) any shareholders in the Equity Share Capital of the Company who are Parties to this Agreement, being PAID and DPW Djibouti [i.e. DP World] as of the date hereof; and

(ii) any Person to whom Shares are issued or transferred in accordance with this Agreement from time to time and who has executed a Deed of Adherence;

while any Shares are held by such Persons; and Shareholder means any of them (as the context requires)."

"14.1 General

(b) The restrictions on Transfer contained in this Clause 14 shall apply to all Transfers, operating by law or otherwise.

(d)The provisions of this Clause 14 are serious and are for the protection of the legitimate interests of all the Shareholders and the Company.

14.5 Deed of adherence

It shall be a condition of any transfer of Shares (whether permitted or required) that:

(i) The transferee, if not already a party to this Agreement, enters into an undertaking to observe and perform the provisions and obligations of this Agreement in the Agreed Form set out in Annexure 5 [sc. 4] hereto (a "Deed of Adherence"); and

(ii) The relevant transferor of Shares assigns its obligations under any guarantee or encumbrance to which it is a party, to the transferee.

14.6 Registration of transfers

(a) The Directors shall only register any Transfer made in accordance with the provisions of this Agreement.

(c) A person executing an instrument of transfer of a Share is deemed to remain the holder of the Share until the name of the transferee is entered in the register of members of the Company in respect of it.

(d) Upon registration of a Transfer of Shares, and provided that the requirements of Clause 15.5 [sc. 14.5] have been complied with, a Shareholder's benefit of the continuing rights under this Agreement shall attach to the transferee who may enforce them as if it had been a party to this Agreement and named in it as a Shareholder."

"(a) The subscribers to these Articles of Association holding Shares in the Capital of the Company, and

(b) Any Persons to whom Shares are issued or Transferred in accordance with these Articles and who have executed a Deed of Adherence;

while any Shares are held by such Persons; and Shareholder means any of them (as the context requires)."

"11.2 Any Transfer of Shares is subject to Clause 14 of the [JVA]. Any Transfer of the Shares of the Company in contravention of this Article 11 or the provisions of the [JVA], shall be void and unenforceable and the Board of Directors shall not register such Transfer under Article 11.1".

"11.3 Consequently

(ii) The conditions provided by the present Article 11 are applicable to any legal or conventional Transfer;

(iv) The provisions of this Article 11 are serious and are for the protection of the legitimate interests of the Company."

"11.7 Deed of Adherence

It shall be a condition of any Transfer of Shares (whether permitted or required) that:

(i) The Transferee, if not already a Party to this Agreement, enters into an undertaking to observe and perform the provisions and obligations of these Articles under a Deed of Adherence; and

(ii) The relevant transferor of Shares assigns its obligations under any guarantee or encumbrance to which it is a party, to the transferee."

"11.8 Registration of Transfers

(i) The Directors shall only register any Transfer made in accordance with the provisions of these Articles and the [JVA].

(iii) A person executing an instrument of Transfer of a Share is deemed to remain the holder of the Share until the name of the transferee is entered in the register of members of the Company in respect of it.

(iv) Upon registration of a Transfer of Shares, and provided that the requirements of [the JVA] have been complied with, a Shareholder's benefit of the continuing rights under this Agreement shall attach to the transferee who may enforce them as if it had been a party to this Agreement and named in it as a Shareholder."

(4) Subsequent events

"Article 1: The ownership of the shares held by the company [PDSA] in the capital of the company [DCT] is transferred to the State to ensure protection of the nation's fundamental interests.

Article 2: The State will compensate the company [PDSA] within a maximum period of two months in exchange for the shares transferred to the State. The compensation terms will be determined by decree.

Article 3: The State representatives in the corporate bodies of the company [DCT], in respect of its stake in the share capital, will be appointed by decree.

Article 4: This order shall take effect upon signature and shall be published under the emergency procedure."

(C) DP WORLD'S CLAIMS IN THE ARBITRATION

"231. Without prejudice to its right to amend, supplement or restate the relief to be requested in the arbitration, DPWD respectfully requests that the Tribunal, by way of a partial award, to:

(a) DISMISS PDSA challenge to the admissibility of DPWD's claims;

(b) UPHOLD its jurisdiction to determine DPWD's claims under DCT's Articles;

(c) [JVA Termination Claim] DECLARE that, notwithstanding PDSA's purported termination of the JVA on 28 July 2018, the termination of the JVA is unlawful and consequently, the JVA remains valid and binding;

(d) [Share Transfer Claim] DECLARE that notwithstanding the Presidential Ordinance, the purported transfer of shares from PDSA to the Republic is in breach of the JVA and Articles and, consequently, invalid and unenforceable and that PDSA remains a shareholder of DCT;

(e) [Breaches Claims] DECLARE that PDSA has also breached Clauses 4.3(c), 5.2(a), 7, 8.5, 9.3, 11.1, 13.1, 14.1(a), 14.3(b),14.5, 15.1(a), 15.1(i), 15.1(j), 16.1, 17.1, 17.2(d) of the JVA and Articles 11.1, 11.2, 11.7, 17, 21.5, 23, 42A, 47.1 of the Articles;

232. In addition, DPWD respectfully requests that the Tribunal:

(a) DECLARE that PDSA is liable to indemnify DPWD for any damages resulting out of the wrongful termination;

(b) ORDER PDSA to pay to DPWD compensation for damages DPWD has incurred as a result of PDSA's wrongful actions in an amount to be quantified at a later date;

(c) DECLARE that PDSA remains party to the JVA and the Articles."

"64. DPWD has described each breach committed by PDSA (or through its affiliate the Republic) in its Statement of Case: ΆΆ 153173. In summary, PDSA is liable for breaches of Clauses 4.3(c), 5.2(a), 7, 8.5, 9.3, 11.1, 13.1, 14.1(a), 14.3(b),14.5, 15.1(a), 15.1(i), 15.1(j), 16.1, 17.1, 17.2(d) of the JVA and Articles 11.1, 11.2, 11.7, 17, 21.5, 23, 42A, 47.1 of DCT's Articles in respect of the following actions:

(a) treating the JVA as terminated (also a breach of the English Injunction);

(b) purporting to transfer its shares to the Republic in breach of the JVA and the Articles, having failed to secure a Deed of Adherence from the Republic;

(c) attempting to unlawfully remove DPWD's nominated directors on the DCT Board at a shareholders' meeting and depriving those directors from exercising their rights as directors of DCT;

(d) seeking to invalidate DCT's Articles and the 18 February 2018 Board Resolution in the Djibouti courts;

(e) appointing an Administrator to take over the Board of DCT, notwithstanding that action is a Reserved Matter;

(f) failing to ensure the distribution of dividend to the shareholders of DCT for at minimum, the year 2017;

(g) preventing DPWD from managing the Terminal and instead managing the Terminal itself, through SGTD, following the passage of Law 29 and Decree 99, as well as undertaking such management and operations of the Terminal, in breach of DCT's exclusivity rights (which are given additional protection under the JVA and Articles);

and

(h) using DCT's assets, including the Terminal and cash in the on-shore bank accounts of DCT for its own benefit and at DPWD's expense." (footnotes omitted)

(D) PDSA'S JURISDICTION OBJECTION BEFORE THE TRIBUNAL

"As PDSA set out in its Statement of Defence, the Tribunal does not have jurisdiction to hear DP World's claims under the Articles, insofar as they relate to events that occurred after the passage of the Dispossession Ordinance on 9 September 2018. As shown in Section III above, upon the passage of the Dispossession Ordinance, PDSA was dispossessed of its shares as a matter of law and fact. As a result, PDSA ceased to be a 'Shareholder' (as defined in the Articles). Since the arbitration clause in the Articles is limited to disputes either 'between the Shareholders themselves regarding the Company affairs' or 'between the Shareholders and the Company', the Tribunal has no jurisdiction to hear any claims under the Articles against PDSA arising out of events that occurred after the Dispossession Ordinance.

In the event that the Tribunal finds that the JVA was wrongfully terminated and that the effect of this is that the JVA remains valid and binding, the Tribunal would also lack jurisdiction for any of DP World's claims under the JVA after the passage of the Dispossession Ordinance. This is because the arbitration clause in the JVA also applies only to disputes between 'the Shareholders arising out of or relating' to the JVA (JVA, C-1, Clause 20). 'Shareholders' is defined in the JVA, inter alia, as 'any shareholders in the Equity Share Capital of [DCT] who are parties to' the JVA " (§§ 89-90)

"188. The Respondent disputes the Tribunal's jurisdiction in the following terms:

"Declare that the Tribunal does not have jurisdiction to hear DP World's claims under the Articles post-dating the dispossession of PDSA's shares in DCT; [ ] and

Declare that the Tribunal does not have jurisdiction to hear DP World's claims under the JVA post-dating the dispossession of PDSA's shares in DCT." (footnote omitted)

"So upon the issuance of that ordinance, PDSA no longer have the quality of a shareholder in DCT which is a necessary component of the Tribunal's jurisdiction . Thus, for events which occurred after the ordinance, this Tribunal is not the available forum; for events which occurred before the ordinance, the Tribunal remains an available forum, in principle."

and:

"Let me turn now to the jurisdiction consequences of the dispossession of PDSA which took effect on 9 September 2018. As of that date, we respectfully submit, the Tribunal is to find that PDSA was no longer a shareholder in DCT and, as we see on the slide that is now on your screen, the arbitration clause in DCT's articles applies only to disputes between shareholders, so far as company affairs are concerned, or between shareholders and DCT itself. That is the effect of article 52.1 of DCT's articles of association. Exactly the same conclusion applies, Madam with respect to clause 20.1 of the JVA."

"THE ARBITRATOR: If I look now at the claimant's request for relief in the statement of reply, the first declaration other than not challenging admissibility and upholding jurisdiction is regarding the termination of the joint venture agreement. My understanding here is that there is no challenge regarding the jurisdiction of this Tribunal regarding that particular claim and I would like to confirm that with the respondent.

DR PETROCHILOS: Madam President, let me perhaps take that starting with your latter point. Your understanding is correct. The termination pre-dates the dispossession arguments and therefore temporally it is within your jurisdiction."

"THE ARBITRATOR: Let me now go to the next claim by the claimant, which is the one that, notwithstanding the presidential ordinance, the purported transfer - - and I'm here quoting from the claimant's request for relief - - the purported transfer of the shares from the respondent to the Republic is in breach of the JVA and the articles and, as a consequence, is invalid and unenforceable.

My understanding is that you have of course a number of objections to, you know, making that particular claim, but am I right that you are not objecting to the jurisdiction on the basis that that is not postdating 9 September?

DR PETROCHILOS: That is correct, Madam President."

"THE ARBITRATOR: So what we have left with is the list of various other breaches, and I would like here to take your list that you have put, for instance, on slide 46 of the presentation that we just went through. It very helpfully lists the various actions on the left-hand side and you've identified those that are in your submission post 9 September, post ordinance, presidential ordinance, and so these concern - - and I believe here the numbers are referenced in the claimant's skeleton. These are 64(d), 64(e), 64(f) and 64(g). So in your submission it is these four claims that there is a jurisdictional challenge, not for the others?

DR PETROCHILOS: Madam, the issue of the temporal limitation, post termination of the JVA, applies to a number of claims. Forgive me, the issue of the post dispossession ordinance applies to a number of claims and these are the four claims that you have identified. I am confirming it in long form so you have it on the record. So they are 64(d), (e), (f) and (g), that is correct."

(E) THE TRIBUNAL'S CONCLUSIONS

"VI. AWARD

NOW THEREFORE THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL DECIDES, HOLDS, AND ORDERS AS FOLLOWS:

a. Decides that it has jurisdiction to hear the Claimant's claims under the JVA and the Articles;

b. [JVA Termination Claim] Declares that notwithstanding the Respondent's purported termination of the JVA on 28 July 2018, the termination of the JVA is unlawful and consequently, the JVA remains valid and binding;

c. [Share Transfer Claim] Declares that notwithstanding the Presidential Ordinance, the purported transfer of shares from the Respondent to the Republic is in breach of the JVA and Articles and, consequently, unenforceable and that the Respondent remains a shareholder of DCT;

d. [Breaches Claims] Declares that the Respondent breached Clause 14.5 of the JVA and Article 11.7 of the Articles;

e. Declares that the Respondent is liable to indemnify the Claimant for any damages resulting out of the wrongful termination;

f. Declares that the Respondent remains a party to the JVA and the Articles;

g. Order the Respondent to pay to the Claimant GBP 1,644,165.78 as Legal Costs and GBP 91,743.75 as Arbitration Costs; and

h. Reserves its decision on other matters. "

(1) JVA Termination Claim

(2) Share Transfer Claim

"notwithstanding the Presidential Ordinance, the purported transfer of shares from PDSA to the Republic is in breach of the JVA and Articles and, consequently, invalid and unenforceable and that PDSA remains a shareholder of DCT." (as quoted in Award § 396)

"this Tribunal has not been asked to, and will not, make any determination on the lawfulness or validity of any foreign act of state, such as the Presidential Ordinance or Law 29 confirming it. Rather, this Tribunal accepts as a given the lawfulness and validity of the Presidential Ordinance or Law 29 under Djiboutian law and decides only on the contractual rights of the Parties to this arbitration under the JVA and the Articles" (Award § 412)

" the Tribunal will take the validity and the lawfulness of the Presidential Ordinance as a given under Djiboutian law and assess whether the Share Transfer it effected was in breach of the JVA and Articles" (Award § 419)