Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Kanval v Kanval [2021] EWHC 853 (Ch) (12 April 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2021/853.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 853 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWHC 853 (Ch)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

CHANCERY DIVISION

PROPERTY TRUST AND PROBATE LIST (ChD)

Royal Courts of Justice

Rolls Building,

Fetter Lane,

London, EC4A 1NL

Date: 12 April 2021

BEFORE:-

MR RECORDER RICHARD SMITH

(Sitting as a Judge of the Chancery Division)

BETWEEN:-

Claim No PT-2018-000579

IMRAN KANVAL

Claimant

- and -

RIZWAN KANVAL

Defendant

AND BETWEEN:-

Claim No PT-2017-000201

JAVAID KANVAL

Claimant

- and -

(1) RIZWAN KANVAL

(2) PRINCE EVANS SOLICITORS

Defendants

Nigel Woodhouse (instructed by Steadfast Solicitors) for the Claimants

Elizabeth Fitzgerald (instructed by Dewar Hogan) for the Defendant/ First Defendant

APPROVED JUDGMENT

HEARING DATES: 2-5 and 12 February 2021

Table of Contents

(b) The parties’ cases in outline. 4

(i) Imran and Javaid’s case. 4

(c) The ‘beneficial interest’ question.. 5

(d) Common intention constructive trusts - legal principles. 6

(i) Express agreement to share beneficial ownership.. 6

(ii) Inferring a common intention to share beneficial ownership.. 6

(iii) ‘Ambulatory’ beneficial ownership.. 7

(e) Preliminary observations on the evidence. 8

(ii) ‘Case building’/ ‘reverse engineering’. 8

(v) November 2017 family meetings. 9

(vi) Evidence of Imran, Javaid and Rizwan.. 10

(i) Imran and Javaid buy Osterley - June 1999.. 11

(ii) Javaid, Urfan and Raza move into Osterley - 1999.. 11

(iii) The brothers’ contributions to the Osterley household expenditure. 12

(iv) Osterley renovations - 2000-2002/ Abid moves in - 2001.. 12

(v) The Osterley “house notes”. 13

(vi) The sale of Osterley - January 2004.. 15

(c) Pre-Sutherland (2004-2006). 15

(i) The alleged ‘buy out’ of Raza’s share in Osterley.. 15

(ii) The Kanval brothers’ Queen’s Drive rental 16

(iii) The Kanval parents’ Princess Gardens rental 16

(d) Sutherland - 2006-2011.. 16

(i) The Sutherland purchase - 2006.. 16

(ii) Rizwan and Urfan’s involvement in the Sutherland acquisition.. 16

(iii) Reasons for Rizwan being on the Sutherland mortgage. 17

(iv) The alleged Sutherland agreement 18

(v) The Sutherland finances - 2006-2010.. 18

(vi) The Devonport renovations - 2007-2010.. 18

(vii) Imran’s financial position in 2010.. 19

(viii) The crowded conditions at Sutherland - 2010.. 19

(ix) The first disputed family meeting - February 2010.. 19

(x) Imran moves out of Sutherland - May 2010.. 20

(xi) The Devonport sale proceeds - July 2010.. 20

(xii) Imran and Javaid’s case on the Devonport sale proceeds. 21

(xiii) The second disputed family meeting - August 2011.. 22

3. ALLEGED AGREEMENT TO SHARE IN SUTHERLAND.. 26

(a) Factors supporting the alleged Osterley/ Sutherland agreement. 26

(iii) The nature of the brothers’ contributions. 27

(b) Factors militating against the alleged Osterley/ Sutherland agreement. 28

(ii) Use of bank accounts not controlled by the brothers. 28

(iii) Ignorance of Osterley sale proceeds/ equity share. 29

(iv) Use of the Devonport sale proceeds. 29

(v) Javaid’s renewal of his Albany Road tenancy.. 30

(vi) Cumbersome nature of the alleged Osterley/ Sutherland agreement 31

(vii) Lack of legal documentation.. 31

(c) The Defendant’s ‘vague’ case on the alleged Osterley agreement. 32

(vii) Conclusion on the Defendant’s evidence. 37

(d) Difficulties with the Claimants’ evidence. 37

(e) The Spreadsheet re-visited.. 38

(f) The two November 2017 family meetings. 39

4. CONCLUSIONS ON BENEFICIAL OWNERSHIP.. 41

5. DISPOSAL OF EQUITABLE INTERESTS - FORMALITIES. 43

6. DISPOSAL OF IMRAN’S SHARE.. 44

(a) Rizwan’s new-found wealth - August 2011.. 44

(b) The third disputed family meeting - September 2011.. 44

(c) Imran had no reason to sell 45

(d) Imran’s ‘disinterest’ in investing in Range Road.. 47

(e) Imran’s explanation for why Rizwan paid him £65,000.. 48

(h) Conclusion as to the sale of Imran’s share. 51

(i) The sale of the other brothers’ shares. 52

7. DISPOSAL OF JAVAID’S SHARE.. 52

(a) Effect of my findings on Javaid’s case concerning his Sutherland share. 52

(b) The fourth disputed family meeting - October 2011.. 52

(c) The status of the £37,770 payment to Javaid.. 53

(a) Javaid’s deceit case in outline. 53

(b) Deceit - legal principles. 54

(i) Nature of the representation.. 54

(v) Continuing representations. 56

(vi) Duty of disclosure in fiduciary relationships. 57

(c) Javaid’s first deceit claim - Rizwan’s available funding.. 57

(ii) Javaid’s first deceit claim - discussion.. 58

(iii) Javaid’s first deceit claim - inducement/ materiality.. 59

(d) Javaid’s second deceit claim - intention to ‘take over’ the mortgage. 60

(ii) Javaid’s second deceit claim - discussion.. 63

(iii) Javaid’s second deceit claim - inducement/ materiality.. 64

9. JAVAID’S BREACH OF CONTRACT CLAIM... 66

10. FINAL CONCLUSIONS AND DISPOSAL.. 66

1. INTRODUCTION

(a) Background

2. The immediate Kanval family members and their role (if any) in these proceedings are identified in the table below. I refer in this judgment to each family member by forename.

|

NAME

|

ROLE |

|

Kanval brothers | |

|

Javaid (04.02.1970) |

Claimant/ witness for Claimants |

|

Kamran (14.08.1971) |

None |

|

Imran (26.08.1972) |

Claimant/ witness for Claimants |

|

Urfan (20.08.1973) |

Witness for Defendant |

|

Rizwan (13.02.1977) |

Defendant/ witness for Defendant |

|

Raza (03.07.1978) |

Witness for Defendant |

|

Amar (13.11.1979) |

None |

|

Abid (10.05.1984) |

Witness for Defendant |

|

Kanval parents | |

|

Abdul (father) |

None (died 2017) |

|

Naseem (mother) |

Witness for Defendant |

3. These proceedings comprise two closely related actions, one by Imran against Rizwan, the other by Javaid against Rizwan and their former solicitors. They follow a prior reference to the First-Tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) as a result of Imran’s application to register a restriction against Sutherland. Given the Tribunal’s more limited jurisdiction, that reference was stayed to allow the dispute to be resolved in the Chancery Division. On 1 June 2019, the two actions were ordered to be case managed and heard together. Javaid’s claim against the Second Defendant was subsequently compromised. The trial therefore concerned only the claims by Javaid and Imran against Rizwan.

4. The evidential phase of the trial took place in person over four days between 2 and 5 February 2021. I heard closing arguments remotely on 12 February.

(b) The parties’ cases in outline

(i) Imran and Javaid’s case

5. Imran and Javaid claim that they were (and remained throughout) the joint legal and beneficial owners of 24 Osterley Views, Norwood Green, UB2 4UN (“Osterley”). They purchased this property using their own funds and their joint mortgage. Rizwan, Urfan, Raza and Abid came to live with them. Since the first three worked, they contributed to the household expenses but none of them enjoyed a beneficial interest in Osterley. Osterley was sold in 2004. Following a period spent by the family in rented accommodation, part of the Osterley sale proceeds were used to purchase Sutherland. On this occasion, Javaid and Rizwan acquired legal title and held the mortgage jointly. However, it was agreed with Rizwan that the beneficial ownership of Sutherland would be held on the same basis as Osterley, namely for the joint benefit of Imran and Javaid.

6. In 2011, legal title to Sutherland was transferred into Rizwan’s sole name. Javaid claims that this followed his offer to sell Rizwan his 50% share for £175,000. In the event, Rizwan said he could only afford £15,000. Javaid therefore agreed to sell Rizwan a small part of his 50% interest on the basis that Javaid would come off the Sutherland legal title and mortgage. Javaid now seeks to set aside that sale for deceit. Imran claims that he never parted with his 50% beneficial share in Sutherland and Rizwan therefore continues to hold this for his benefit.

(ii) Rizwan’s case

7. Rizwan’s account is very different. He claims that, following their purchase of Osterley, Javaid and Imran agreed that the working brothers who contributed to the household expenditure - Imran, Javaid, Rizwan, Urfan and Raza - would enjoy a beneficial interest in the property proportionate to their contributions and that Abid would enjoy a fixed share. Save in respect of Raza, the same agreement was later expressly repeated for Sutherland.

8. Javaid moved out of Sutherland in 2010, having indicated his desire to realise his beneficial interest in due course and purchase a new house. Rizwan agreed in 2011 with all the brothers, including Imran and Javaid, to acquire their beneficial interests in Sutherland. The brothers’ shares were calculated by Javaid who committed them to a spreadsheet which he presented at a family meeting in August 2011 (“the Spreadsheet”). Having bought out all the brothers’ shares on the basis of the Spreadsheet, Rizwan is now the sole legal and beneficial owner. Rizwan denies Javaid’s deceit claims.

9. Imran and Javaid deny any agreement for all the brothers to share beneficially in Osterley or Sutherland, they claim that the Spreadsheet has been fabricated and, save for the sale of the small part of his 50% share in Sutherland (of which Javaid now seeks rescission), they deny that they have parted with their beneficial interests.

(c) The ‘beneficial interest’ question

10. The ascertainment of the beneficial interests enjoyed in Sutherland is therefore the key issue for my determination. The resolution of that issue and the related factual disputes will also supply the proper context within which the alleged disposal of Imran and Javaid’s interests, and Javaid’s related deceit claims, fall to be considered.

11. One notable feature of this case is that neither party argues that the beneficial ownership of Sutherland upon purchase in 2006 followed legal title. Imran and Javaid claim that Sutherland was held for their joint benefit even though Imran was not on the legal title. Rizwan claims that Sutherland was held for the benefit of Imran, Javaid, Rizwan and Urfan in proportion to their respective financial contributions (with Abid enjoying a fixed share) even though none of Imran, Urfan and Abid was on the legal title.

12. Both parties say that the respective beneficial interests they contend for arose under a common intention constructive trust, whether expressly by agreement or inferentially by conduct. Given the different outcomes asserted, it is perhaps unsurprising that they have presented different accounts of their dealings. Those conflicting accounts and the parties’ related submissions occupied by far the greatest time at trial and, therefore, this judgment. However, I have not addressed every twist and turn of the evidence rather than those issues that are material to my conclusions.

(d) Common intention constructive trusts - legal principles

13. Although the ascertainment of the parties’ beneficial interests in Sutherland turns largely on the resolution of their factual disputes, and the parties were largely agreed on the applicable principles, I summarise here the legal framework within which I have applied my factual findings to reach my conclusions later in this judgment.

(i) Express agreement to share beneficial ownership

14. As Lord Bridge stated in Lloyds Bank Plc v Rosset [1991] 1 AC 107 at [132E-F]:-

“The first and fundamental question which must always be resolved is whether, independently of any inference to be drawn from the conduct of the parties in the course of sharing the house as their home and managing their joint affairs, there has at any time prior to acquisition, or exceptionally at some later date, been any agreement, arrangement or understanding reached between them that the property is to be shared beneficially.”

15. The starting point in the analysis is therefore whether there was an express agreement, arrangement or understanding between the parties that Sutherland was to be shared beneficially. According to Lord Bridge, a finding of such an agreement must be based on evidence of “express discussions” between the parties. In this case, both parties contend that there were such discussions albeit, as noted, in very different terms. The party asserting the claim for a beneficial interest must also show detrimental reliance to give rise to a constructive trust. The parties were agreed that matters could also be approached in terms of a proprietary estoppel, albeit this added little to the analysis which they, therefore, confined to one based on constructive trusts.

(ii) Inferring a common intention to share beneficial ownership

16. Lord Bridge went on to state that, in the absence of an express agreement or arrangement, an intention to share the beneficial interest could be inferred from the parties’ conduct but he doubted whether anything less than “direct contributions to the purchase price by the partner who is not the legal owner, whether initially or by payment of mortgage instalments” would suffice (at [133B]). However, the law appears to have moved on since Lord Bridge’s indication as to the narrow basis on which a constructive trust might be inferred (see Stack v Dowden [2007] UKHL 17 per Lord Walker at [25-26], [34-36], per Lady Hale at [63] and per Lord Neuberger at [139]); see too Abbott v Abbott [2007] UKPC 53 per Lady Hale at [19]: “[t]he parties’ whole course of conduct in relation to the property must be taken into account in determining their shared intentions as to ownership”.

17. The process is the ascertainment of “the parties’ shared intentions, actual or inferred with respect to the property in light of their entire course of conduct in relation to it”. That search is “for the result which reflects what the parties must, in the light of their conduct, be taken to have intended”; it “does not enable the court to abandon that search in favour of the result which the court itself considers fair” (Stack v Dowden per Lady Hale at [60-61]; see too Jones v Kernott per Lord Walker at [51-52]).

18. The court may only impute an intention to the parties in respect of the quantification of the shares. It may not impute an intention that the beneficial interest is to be shared in the first place. It is still a question of the parties’ actual shared intentions, express or inferred, whether the beneficial interests are to be shared at all (see Jones v Kernott per Lord Walker at [33]; see too Geary v Rankine [2012] EWCA Civ 555 per Lewison LJ at [21]).

(iii) ‘Ambulatory’ beneficial ownership

19. Rizwan claims that the precise shares in which Osterley and, later, Sutherland were held were never the subject of an express common intention rather than a general intention that they would each share according to their respective contributions. There is no conceptual difficulty with an “ambulatory” constructive trust, albeit “compelling evidence” might be required to infer an intention to change beneficial shares subsequent to acquisition (see Stack v Dowden per Lady Hale at [62] and per Lord Neuberger at [138]).

(iv) Burden

20. Although the principles summarised above were largely common ground, the parties did differ when it came to the question of burden, specifically the onus on the non-legal owner to show that beneficial ownership of the property did not follow legal title. That burden has been described as a “heavy” one (see Stack v Dowden per Lord Walker at [33] and per Lady Hale at [68]; see too Jones v Kernott per Lord Collins at [60]).

21. The Claimants emphasise the (apparently uncontroversial) fact that, prior to the agreement alleged by Rizwan to share in the beneficial ownership of Osterley, Imran and Javaid were sole legal and beneficial owners. Since that alleged agreement is said by Rizwan merely to have been repeated with respect to Sutherland, the “heavy” burden of showing that the beneficial interest does not follow the Sutherland legal title falls on him. By contrast, the Defendant emphasises the (again uncontroversial) fact that Rizwan is now sole legal owner of Sutherland and says that the “heavy” burden therefore falls firmly on the Claimants.

22. In my judgment, the parties’ arguments overlook three important points: first, this case is concerned with the beneficial ownership of Sutherland, not Osterley; second, this is not a case in which Rizwan is, and has always been, the sole registered proprietor of Sutherland, with the Claimants seeking to persuade the Court that the parties intended for them to share in the beneficial ownership. To the contrary, the Claimants say that they have always enjoyed joint beneficial ownership and that nothing has changed in that regard (save with respect to a small part of Javaid’s beneficial interest); third, it is common ground, albeit for different reasons, that the beneficial interests in Sutherland upon acquisition in 2006 did not follow legal title.

23. To my mind, the pertinent questions are which of the parties, if any of them, is right as to why the beneficial interest in Sutherland diverged from legal title in 2006, who enjoyed that beneficial interest then and what, if anything, has happened to it since. The prior arrangements with respect to Osterley will obviously be relevant to those questions, as will Rizwan’s subsequent acquisition of legal title to Sutherland. As noted (at [16] above), “[t]he parties’ whole course of conduct in relation to the property must be taken into account in determining their shared intentions as to ownership”. However, in the more unusual circumstances of this case, it seems to me that burden will not play as significant a role as otherwise it might.

(e) Preliminary observations on the evidence

(i) The witnesses

24. At trial, I heard evidence from eight fact witnesses, namely the six brothers identified as witnesses in the table (at [2] above), Naseem and Mr Kin Ching Yeung, whom I shall refer to in this judgment by his nickname, “Danny”. One consequence of the Tribunal proceedings was that, for most witnesses, two written statements had been prepared, the first for the Tribunal, the second for the Court. Both were referred to at trial. I refer in this judgment to paragraphs of the Tribunal statements as, for example, “(Javaid TWS at [X])” and the High Court statements as “(Javaid WS at [X])”.

(ii) ‘Case building’/ ‘reverse engineering’

25. The Claimants characterised key aspects of the Defendant’s evidence as brief or vague. They argued that this afforded Rizwan a ‘blank canvas’ to develop his evidence or ‘case build’. Other aspects were said to be ‘reverse engineered’, with Rizwan adapting certain parts of his story - conveniently, but implausibly - to meet difficulties elsewhere. I address those criticisms below as they arise in my analysis of the evidence.

(iii) Naseem’s evidence

26. Naseem’s statements were in English. The Claimants say that these were neither in her own words, nor in her own language (Urdu) and were, therefore, not compliant with CPR, Part 32. Nor did Naseem have personal knowledge of the arrangements with respect to Osterley. Finally, following cross-examination, it was not apparent what first hand evidence she could give. As such, little or no weight should be accorded to her evidence.

27. I agree that the circumstances in which Naseem’s statements were prepared should have been explained in the documents themselves. However, she provided an explanation in oral evidence from which it became apparent that she struggles to read and write in Urdu and that she required someone to assist to write down her account for her. She explained that Raza did so and that they took a number of weeks to complete the task. Given these difficulties and her candid explanation, which I accept, I consider it would be wrong to accord her statements no weight.

28. Naseem gave oral evidence in Urdu, through a translator. Although she was clear in her recollection on a number of points, including to an impressive level of detail for some, other aspects of her evidence were confused and difficult to follow. This was not due to a lack of cogency or co-operation on her part. Rather, in some instances at least, the questions put to her (by both parties) could have been framed more obviously as such and in briefer terms to meet the different needs of this particular witness, including her language, age and inexperience of formal settings such as these proceedings. Again, I therefore consider it would be wrong to attach no weight to her oral testimony but I have obviously only paid regard to those aspects on which I was sure as to her level of comprehension.

29. I also consider unfair the criticism that it was not apparent what first hand evidence she could give. There were a number of matters within her direct knowledge on which she could and did give evidence. To the extent she recounted matters she had heard second hand - and on some aspects she did - I have reflected this in my assessment of the evidence and accorded it appropriate weight in light of that limitation.

(iv) Raza’s evidence

30. In closing argument, the Claimants invited me to exercise caution when considering Raza’s evidence in light of a previous conviction connected with fraudulent invoicing. It was suggested that this might indicate a propensity to dishonesty. However, it does not follow from Raza’s admitted dishonesty that he has, or may have, a propensity to lie. In my judgment, the Claimants were right not to put this point too highly. I was also invited to discount Raza’s evidence based on his prior legal training but I found that submission unpersuasive.

(v) November 2017 family meetings

31. In assessing the witnesses’ evidence, I have paid particular regard to those documents the authenticity of which is not disputed. These include the transcripts of two family meetings held in November 2017 secretly recorded by Imran. The statements he recorded have their limitations: they were made out of court and not on oath, when litigation was already on foot and in a contentious environment and somewhat unfocused manner. However, they do concern important disputed matters in the case. I have therefore had regard to them in considering the accuracy of the witnesses’ accounts, particularly of the Defendants’ witnesses, since they were speaking most freely, unaware at the time that they were being recorded.

32. In referring to the transcripts, I have ascribed the rubric “T1” to the first meeting on 11 November 2017 and “T2” to the second on 18 November 2017.

(vi) Evidence of Imran, Javaid and Rizwan

33. Imran, Javaid and Rizwan stuck to their accounts throughout their oral evidence, albeit this sometimes suffered from (different) shortcomings. Imran, for example, downplayed a number of matters, some of little consequence to his case. Javaid was more measured but I also found him well prepared and unusually familiar with some of the documents such that, on occasion, I could not distinguish his true recollection from reconstruction. Initially, I found Rizwan to be a straightforward and direct witness, answering questions candidly and making appropriate concessions. However, as his evidence continued, his answers became increasingly prolix and justificatory in tenor. Despite these matters, I cannot say that any of them was obviously untruthful. The accuracy of their evidence therefore falls to be assessed by reference to, amongst other things, its consistency, plausibility and probability, the contemporaneous documents, the undisputed facts, motives and the evidence of the other witnesses.

2. THE EVIDENCE

34. I now analyse the evidence, approaching matters chronologically by reference to four broad phases.

(a) Pre-Osterley

35. In 1980 or 1981, Abdul and Naseem purchased 56 Devonport Road, Blackburn, Lancashire (“Devonport”).

36. In 1997, Imran moved to London, intending to undertake a PhD, later deciding to work instead, initially at the accountancy firm, Gambrill & Co. and, from 1998, as a bookkeeper at a firm called Marble City. After completing his PhD, Javaid joined Imran in London in 1998. They were both in their late twenties at the time. Javaid secured employment in London quickly, initially as an analyst at Hay’s Distribution before moving to Iron Trades in 1998.

37. Imran and Javaid initially shared a bedsit in Brent but decided to buy a property together in London in the expectation that the market would go up. Their budget was around £150,000. While looking for potential properties, they found Osterley. Although a bigger and more expensive property than they had been looking for, they decided to buy it. None of the other Kanval brothers was involved in their property search or the Osterley purchase.

(b) Osterley - 1999-2004

(i) Imran and Javaid buy Osterley - June 1999

38. Imran and Javaid completed the Osterley purchase on 1 June 1999. The property was registered in their joint names. The purchase price was £195,000. The associated purchase costs were £2,815.62. Imran and Javaid financed the purchase with a mortgage from Abbey National for £184,980 and £12,835.62 from their own funds, comprising their own savings and (part of) two personal loans for £10,000 each.

39. The Osterley mortgage was interest only, with initial monthly payments of £969.04 paid from Javaid’s personal HSBC account. Imran and Javaid took out separate endowment policies at an initial monthly cost of £138.65 each.

(ii) Javaid, Urfan and Raza move into Osterley - 1999

40. Shortly after the Osterley purchase, Imran and Javaid were joined by some of their brothers. Rizwan moved into Osterley in around June 1999. He was 22. On the evidence, it was common ground that Rizwan was invited to stay at Osterley because of the better opportunities afforded to him in London. Rizwan was followed by Urfan who came to London in around July 1999. Urfan was 26. Javaid said he was surprised to see Urfan turn up at Osterley (Javaid WS at [13]). However, I consider it unlikely that Urfan would have turned up unexpectedly. I preferred Urfan’s evidence that he was invited to move into Osterley for the same reasons as Rizwan. Raza moved into Osterley in around December 1999. He was 21. He too confirmed in oral evidence that Imran and Javaid had invited him to stay. Although none of them had jobs in London lined up before they arrived, Rizwan, Urfan and Raza soon found full-time employment, albeit Urfan ‘temped’ for some time.

41. In his statement, Rizwan said that, after he moved in, Imran and Javaid agreed with him and Urfan that the brothers would all be “equity holders” in Osterley based on their financial contributions (Rizwan TWS at [3]). Urfan said that, when he moved into Osterley, it was “explicitly agreed” that, by contributing to the mortgage and other household outgoings, the brothers would acquire a “beneficial interest” (Urfan WS at [3]). Raza too said that Imran, Javaid, Rizwan and Urfan agreed that the brothers would receive an “equitable stake” proportionate to their financial contributions to the Osterley expenditure (Raza TWS at [4]). The alleged agreement to share in the beneficial ownership of Osterley is a central issue in the case, with Rizwan, Urfan, Abid and Raza claiming the same arrangements obtained with respect to Sutherland (Rizwan TWS at [9]; Urfan WS at [3]; Abid TWS at [3]; Raza TWS at [8]). Since this came in for sustained criticism, I address in some detail below the written and oral evidence of Rizwan, Urfan, Abid and Raza concerning the alleged agreement for Osterley and the ‘renewal’ of that agreement for Sutherland. For present purposes, it suffices to say that Imran and Javaid reject their accounts (Imran WS at [46]; Javaid WS at [16, 23-24]). They did not agree to share the Osterley equity but they were happy to allow their brothers to stay until they “got themselves on their feet and were able to purchase their own properties”. In the meantime, Javaid charged them “rent” (Javaid WS at [15, 17]).

(iii) The brothers’ contributions to the Osterley household expenditure

42. I first examine a key aspect of that alleged agreement, namely the brothers’ contributions to the Osterley and Sutherland household expenditures. It is common ground that all the working brothers shared in the household expenditure for Osterley and, later, Sutherland, that they paid their respective contributions to Javaid and that he organised the household finances and settled most of the expenses. However, there was some debate as to whether, before January 2002, the brothers made fixed monthly contributions or whether these were variable throughout according to the actual expenditure incurred each month.

43. Imran and Javaid said that the brothers initially made a fixed payment towards the expenses (Imran WS at [36]; Javaid WS at [17-19]). Urfan and Raza said the same in oral evidence. Rizwan said the payments were variable from the outset. He relied on a schedule prepared by reference to cheque debits in his bank statements and his corresponding cheque stubs from which he had identified his payments for “mortgage”. However, for the early period, Rizwan was missing the relevant cheque stubs as a cross-check against the cheque debits listed in his schedule. If all the payments relied on by Rizwan had been made towards the household expenditure, I agree with the Claimants that Rizwan would, in fact, have been overpaying, perhaps significantly, for some months. This seems unlikely. I therefore prefer the evidence of Imran, Javaid, Urfan and Raza that the brothers initially made fixed monthly contributions to the Osterley expenditure. I accept that these were £450 each per month, later increased to £550. I also reject Rizwan’s evidence that £5,000 paid to him by Javaid in April 2004 represented an overpayment to the Osterley expenses (Rizwan WS at [15]).

(iv) Osterley renovations - 2000-2002/ Abid moves in - 2001

44. Renovation work on Osterley started in late 1999 or early 2000, with the smaller jobs tackled first, building up in 2002 to the more ambitious works.

45. In mid-2000, a £10,500 loan was taken out to fund some of the renovation works (Javaid WS at [loan table, loan 3]).

46. In about mid-2001, Imran stopped working at Marble City to concentrate full-time on the Osterley improvements. Imran did not contribute to the household expenditure during this period. Having sat exams in Blackburn, Abid (then 17) came down to London in Summer 2001 to help with the renovations.

47. There was some debate as to whether all the brothers assisted with the renovations. Imran said that the brothers would sometimes help but (Javaid and Abid apart) they did not do a lot (Imran WS at [32]) and, in oral evidence, that Rizwan and Raza, in particular, were not much help. It would not, of course, have been possible for them to dedicate as much time and effort to the renovations as Imran. Imran had temporarily given up work for that purpose. Although the brothers may well have exhibited varying degrees of enthusiasm, they all shared the same house and they all benefitted from the improvements. In this regard, I found more persuasive the oral evidence of Urfan and Abid that all the brothers ‘mucked in’ even if, as Urfan put it, Imran was the “lead architect”.

48. In August 2001, Imran and Javaid obtained a £19,376 mortgage extension, adding approximately £80 to the monthly mortgage cost. This too was used to pay for the household improvements. Imran and Javaid’s monthly endowment payments increased to £233.67 each. In the same month, Imran and Javaid opened a new joint RBS account referred to at trial as the “house account”. This received the funds from the mortgage extension and, going forwards, handled the household expenditure and brothers’ respective contributions. However, the mortgage continued to be paid from Javaid’s personal HSBC account. Imran explained that the house account also operated as a ‘personal bank’ for the brothers (Imran WS at [39]). So, for example, in 2009, Imran borrowed £25,000 from RBS to make an investment. The monthly loan payments (£353.10) were then taken from the house account. Imran also used the account to make certain payments to his credit card. He would then ‘repay’ the account by depositing into it.

49. After returning to Blackburn to get his exam results, Abid moved back permanently to Osterley later in 2001, attending college in London. Naseem joined him, with Amar and Abdul joining later. Abid, Amar, Abdul and Naseem did not contribute to the household expenses.

50. Javaid got married in Pakistan in November 2001.

51. In early 2002, Javaid started charging the brothers a variable monthly amount based on the actual monthly household expenditure rather than a fixed sum, with the aim of splitting the outgoings between all the working brothers (Javaid WS at [48]).

52. Abid said that Imran, Javaid, Rizwan and Urfan all agreed to give him a fixed 8% share in Osterley (Abid WS at [3]). In oral evidence, Abid said that Raza was also present when they agreed this in early 2002. Imran and Javaid deny this alleged agreement as well (Imran WS at [47]; Javaid WS at [42]) and were critical in submission of Abid’s related evidence. I address those criticisms below as they arise in my analysis.

(v) The Osterley “house notes”

53. Each month, Javaid prepared manuscript notes showing the household expenditure and corresponding contributions due from the brothers. Javaid prepared these from 1999 but only retained the notes from January 2002 to May 2004. Javaid said he prepared these documents for himself although Rizwan and Urfan both testified that Javaid showed them to the brothers. Since they explained how the brothers’ contributions were calculated, I consider it likely that Javaid did show them. Although the notes are difficult to follow in parts, they provide useful insights into the organisation, payment and reimbursement of the household expenditure. For example, these show:-

a. Outstanding amounts due from the brothers brought forward from prior months.

b. Loan payments due. For February 2002, for example, these were:-

JAVAID 200-99

HOUSE 239-39

IMRAN 269-00

RAZA 151-00

c. The monthly household expenditure. For February 2002, for example, this was:-

FOOD (JAVAID, URFAN, RIZWAN, RAZA) = 320-00

CARPET 75-00

ENDOWMENT 229-28 x 2

MORTGAGE 1028-64

COUNCIL TAX 119-00

GROUND RENT 100-00/12

SERVICE CHARGE 774-46 x 2/12

BILLS (ELECTRICITY, WATER) = 21-00 + 266/6

HOUSE INSURANCE 250-00/12

CAR INSURANCE 400-00/12

CAR MOT + ROAD TAX + REPAIR 300-00/12

d. The payments made (or to be made) by the brothers, split between Imran, Javaid, Rizwan, Urfan and Raza.

54. The monthly loan payment for “HOUSE - £239-39” (to which the brothers contributed) corresponds to loan 3 in Javaid’s loan table. As noted (at [45] above), this was taken out to fund the Osterley renovation works.

55. The other notes show other costs shared by the brothers such as telephone, television licence, furniture, petrol and other household expenses, some very small. They also show payments and receipts by both cash and cheque, monies owing between the brothers, personal expenses incurred by the brothers and expenses incurred by, and payments to, other members of the Kanval family, as well as payments to Pakistan.

56. In May 2002, a second mortgage extension of £32,000 was obtained, adding £120 to the monthly mortgage cost, bringing the outstanding mortgage balance to approximately £240,000. This was used to pay off some of the loans identified in Javaid’s loans table. The increased interest (and endowment) payments on account of both mortgage extensions were recorded in the monthly expenditure in the house notes and formed part of the variable contributions paid by the brothers each month.

57. In this regard, there was some debate about the brothers’ financial contributions to the Osterley renovations. From reading Imran’s and Javaid’s statements, I had originally understood their evidence to be that the brothers did not contribute financially to these. In oral evidence, Imran accepted that all the brothers did contribute through the apportionment of certain costs of borrowing used to fund the works. Javaid accepted this too but denied that all the renovation costs were shared. He pointed, for example, to the cost of the stairs and splashbacks removed in one set of the house notes from the split of expenses between the brothers. Rizwan, Urfan and Raza testified to their understanding that the renovation costs were all split.

58. In the absence of a detailed accounting, it is not possible to isolate the precise Osterley renovation costs and the amount reimbursed by the brothers. However, this is not necessary. The Claimants accepted in closing submission that the brothers all contributed to some of the renovation costs. I agree and, based on the evidence, I consider it likely that their related contributions were significant. However, I also accept that Imran and Javaid (who ‘fronted’ the renovations costs and related borrowings) may have suffered a shortfall against their total outlay. The Osterley refurbishment was completed in 2002.

59. In August 2002, Raza married and moved out of Osterley. In December 2002, Javaid’s wife moved into Osterley, followed by Imran’s wife in August 2003.

(vi) The sale of Osterley - January 2004

60. Osterley was sold in January 2004. The completion statement shows a sale price of £357,000 and the redemption of the Abbey National mortgage (with an outstanding principal of £248,222.22). Deducting the other transaction costs left a completion balance of £91,284.26 payable. This was paid into the house account. In March 2004, £80,000 of that sum was paid into a Halifax savings account in Javaid’s name, yielding a higher rate of interest.

61. Further sums relating to Osterley were paid after completion, including £5,000 retention monies and a £4,625 refund by Abbey National of an early redemption penalty for the mortgage. These were paid into the house account.

(c) Pre-Sutherland (2004-2006)

(i) The alleged ‘buy out’ of Raza’s share in Osterley

62. Raza and Urfan claim that, following the sale of Osterley, the value of Raza’s beneficial share of Osterley was ‘paid out’ to him, partly through satisfaction of debts due from Raza to Urfan, partly by payment of money to Raza (Urfan TWS at [14]; Raza TWS at [6]). The Claimants deny this and say that the only sum paid out to Raza was the repayment of a loan to Imran (Javaid WS at [58]). They also submit that Raza and Urfan’s related evidence has changed to make the facts ‘fit’ the story better. Again, I address their criticisms below in my analysis of the evidence.

63. In February 2004, Rizwan and Urfan married their respective wives in Pakistan.

(ii) The Kanval brothers’ Queen’s Drive rental

64. In February 2004, Imran, Javaid, Rizwan and Urfan moved into a rented property identified by Rizwan at 12 Queen’s Drive, West Acton, London (“Queen’s Drive”). The initial deposit and six months’ rent were paid from the house account using some of the Osterley sale proceeds. Javaid again organised the household finances and, as with the mortgage on Osterley, the Queen’s Drive rent (and other household expenses) were split between the four working brothers. This included ongoing payments for the two Osterley endowment policies until surrendered later in 2004, realising £4,557.13 and £4,472.01 respectively. Those sums were also paid into the house account.

(iii) The Kanval parents’ Princess Gardens rental

65. Following a trip to Pakistan, Abdul, Naseem and Amar moved into a different rented property at 57 Princess Gardens, West Acton, London (“Princess Gardens”) in May 2004. The deposit and a rental payment were paid from Javaid’s Halifax savings account. Imran and Javaid said that they also helped their parents with the further rent on Princess Gardens to the tune of some £22,600 and that their father promised to pay them back from the sale of Devonport (Imran WS at [53]; Javaid WS at [65]). Naseem disputed this and said that Abdul and Amar used to receive benefits and that her husband paid money to Javaid in cash or by cheque. In closing argument, both parties agreed that the issue of the Princess Gardens rent was a ‘distraction’ with which the Court need not be troubled. I agree.

(d) Sutherland - 2006-2011

(i) The Sutherland purchase - 2006

66. On 31 May 2006, the purchase of Sutherland was completed. Unlike Osterley, which had been registered in Imran’s and Javaid’s names, legal title to Sutherland was registered in the names of Javaid and Rizwan. The Sutherland purchase price was £485,000. This was funded with a Halifax mortgage of £440,970. The deposit, purchase expenses and balance of the purchase price (£56,203.56 in aggregate) were paid from Javaid’s Halifax savings account. The mortgage was again interest only, with initial monthly payments of just over £1,600 paid from the house account.

(ii) Rizwan and Urfan’s involvement in the Sutherland acquisition

67. Certain aspects of the evidence concerning the acquisition of Sutherland were controversial, including the extent of Rizwan’s involvement in the purchase. It is common ground that Imran found Sutherland. Imran testified that it was only after he and Javaid decided to buy Sutherland that they discussed this with the rest of the family. Rizwan’s evidence was different. He said the decision to buy another property was a collective one, taken by the family much earlier while they were still renting Queen’s Drive. Rizwan also underlined his involvement in the purchase by pointing to an e-mail from Javaid with a suggested approach to be made by Rizwan to the vendors about the purchase price. Rizwan took this forward with the agents by negotiating a reduction. Imran said that Rizwan “wanted to be involved” and only got involved in the negotiation “at my instructions”. Javaid said that Sutherland was not intended as a family home and he expected Rizwan and Urfan to move on shortly after the Sutherland purchase (Javaid WS at [67]).

68. I prefer Rizwan’s evidence in this regard: first, the email from Javaid and Rizwan’s response was forwarded by Javaid to Imran and Urfan with the comment “[f]or your reference and whether you wish to add any further comments.” If Rizwan and Urfan had not been meaningfully involved in the decision to buy Sutherland, it is unlikely that Javaid would have provided this exchange for Urfan’s information, let alone invited his further comment; second, if Rizwan and Urfan were expected to move out in short order, it is unlikely that Rizwan would have agreed to go onto the mortgage and assume long-term personal liability for the Sutherland borrowings.

(iii) Reasons for Rizwan being on the Sutherland mortgage

69. The brothers’ explanation for Rizwan going onto the Sutherland legal title (and, therefore, mortgage) also differed. Imran put this down to tensions with the wife of the proprietor of Gambrill & Co., the accountancy firm where he was working. According to Imran, the proprietor - “Laurie” - was absent from the business for health reasons. Laurie’s wife had expressed concerns about how the firm could sustain all the outgoings and that the Kanvals might be taking over the cash generating part of the business. Imran, in turn, was concerned that Laurie might pursue him and that is why he did not want the house (and, therefore, mortgage) in his name. The Claimants accepted in closing argument that Imran’s explanation was “unusual”.

70. Rizwan’s explanation was that Imran could not be on the mortgage because of historical debts, loan defaults and Imran’s unpredictable income. Imran testified that he had only one loan at the time, he denied any default and he said he was being paid regularly. Urfan also testified on this aspect. He was unaware that Imran had debt problems and, having worked at Gambrill & Co. himself at the relevant time, he could see that Laurie’s wife might have been suspicious. However, he offered a different insight into why Imran could not go onto the mortgage, again informed by his inside knowledge of Gambrill & Co.’s operations. Urfan worked at the firm all the time and was therefore paid regularly. Imran did not and his remuneration was therefore less regular.

71. It was suggested in closing argument that this different treatment of Urfan and Imran by the same firm made no sense. That submission overlooked Urfan’s evidence about their different working and, therefore, remuneration patterns. Urfan’s related evidence was balanced and straightforward. Imran’s was convoluted. I prefer Urfan’s and I find that Imran did not go onto the mortgage (and therefore legal title) because his income was unpredictable at the time and he could not satisfy the Halifax’s related lending requirements, not least for a mortgage more than double the size of that for Osterley.

(iv) The alleged Sutherland agreement

72. The final controversy surrounding the acquisition of Sutherland concerned what, if anything, the brothers agreed concerning the beneficial ownership of the property. As I have noted, Rizwan, Urfan, Abid and Raza said that the alleged agreement for Osterley also obtained with respect to Sutherland (at [41] above). Rizwan testified that, when the brothers decided to buy another house, it was expressly agreed that they would carry forward their interest from Osterley into any new property (save for Raza who had been paid out the value of his share in Osterley). The “established mechanism” for Osterley would also work in the same way such that the brothers would again enjoy a share in the new property proportionate to their contributions. Urfan testified similarly. He said that, when they were planning to market Osterley, they decided to rent while they waited to buy a new property for which they would use the Osterley proceeds and that they would share in the new property on the same basis as Osterley. Abid was away at university at the time of the Sutherland purchase. However, he said he knew that his brothers had decided to put the Osterley proceeds into the new property and that it was their collective decision to move and buy this together. Imran and Javaid claim that it was made clear to Rizwan when he went onto the mortgage (and legal title) that he would have no interest in Sutherland. Rizwan understood and agreed this (Imran TWS at [21]; Imran WS at [61]; Javaid TWS at [18]); Javaid WS at [69]). Like Osterley, Sutherland would be held for their joint benefit alone.

(v) The Sutherland finances - 2006-2010

73. Imran, Javaid, Rizwan, Urfan and their respective wives and children and Abid, Abdul and Naseem moved into Sutherland in around May 2006. Although there are no longer any house notes for Sutherland, it is common ground that the household expenditure was organised and reimbursed in the same manner as Osterley (and Queen’s Drive), with the working brothers dividing the expenses between them. The amount they paid again varied from month to month depending on the actual expenditure incurred.

74. Abid did not start contributing to the Sutherland expenses until late 2006, initially £800 per month, later reduced to £400 because he did not have a room of his own, later increased to £600 when Javaid moved out and Abid secured a room (Abid TWS at [3]). Raza moved in and out of Sutherland on two occasions when Javaid charged him £800 per month, later £400. He has since moved back into Sutherland again (Raza TWS at [7]).

(vi) The Devonport renovations - 2007-2010

75. In 2007, renovation works commenced on Devonport. As with the Osterley renovations, there was some dispute about the level of the brothers’ assistance with the work. Imran claims he bore the greatest burden, with the other brothers assisting early on but, Javaid apart, later losing interest. Rizwan, Urfan, Abid and Naseem testified that all the brothers helped. In my view, nothing turns on this, neither party pressed the point in closing and it is not necessary for me to resolve it. The Devonport renovations were completed in around January 2010.

(vii) Imran’s financial position in 2010

76. There was some debate about Imran’s financial position around this time. Rizwan said he discovered from Javaid that the house account was funding Imran’s business ventures and that Imran had not made regular payments into the house account for some time (Rizwan WS at [19-20]). Urfan said that Javaid was angry with Imran about misusing the house account and how this had caused Javaid problems with his credit rating (Urfan TWS at [11]). In oral evidence, Imran denied that he was having financial problems, that his financial position affected Javaid’s or that Javaid was fed up with him. Javaid accepted that Imran had started to take a lot from the house account for his own private use but denied this caused an issue. Javaid merely asked Imran to account for the money he had used.

(viii) The crowded conditions at Sutherland - 2010

77. It is no exaggeration to say that, by 2010, Sutherland was ‘bursting at the seams’. By that stage, Sutherland was occupied by 16 people, namely:-

a. Imran his wife and child;

b. Javaid, his wife and child;

c. Rizwan, his wife and two children;

d. Abdul and Naseem;

e. Urfan, his wife and child; and

f. Abid (who slept in the lounge).

(ix) The first disputed family meeting - February 2010

78. This is the cramped context in which Rizwan says the first of four family meetings - all hotly disputed by Imran and Javaid - took place. The first was said to have taken place in February 2010, attended by Imran, Javaid, Rizwan, Urfan, Abid, Abdul and Naseem. Rizwan says that Javaid called the meeting, explained that his growing family needed more space and announced his intention to move out and rent a property for a year or so. This would allow enough time for arrangements to be put in place for his share in Sutherland to be bought out so that he could purchase another property. If he was not bought out, Sutherland would have to be sold (Rizwan TWS at [10]).

79. Urfan did not refer to this meeting in his written evidence but Abid and Naseem did (Abid TWS at [5]; Naseem TWS at [8])). In oral evidence, Abid said that this took place in about January or February 2010. Imran and Javaid deny the meeting and testified that Javaid left Sutherland for the simple reason that his family needed more space. They also said that Javaid had, in fact, approached Rizwan and Urfan in 2010 about them moving out but this had merely caused family tensions (Imran WS at [76]; Javaid WS at [79]).

80. In March 2010, Javaid’s wife gave birth to twins.

(x) Imran moves out of Sutherland - May 2010

81. In May 2010, Javaid moved out of Sutherland and into nearby rented accommodation in Albany Road. Urfan moved out of Sutherland at around the same time. He rented as well. Both stopped contributing to the Sutherland household expenditure. The house account was closed and, as Javaid confirmed in oral evidence, Rizwan then arranged for the monthly Halifax mortgage payment to be made from his own account.

82. According to Rizwan and Abid, with Javaid and Urfan now gone, Abid agreed to increase his contributions from £400 per month, Imran agreed to pay what he could and Rizwan agreed to increase his payments from £800 to make up the shortfall (Rizwan TWS at [11]; Rizwan WS at [24]; Abid TWS at [4]). Imran testified that Rizwan took over financial responsibility for the mortgage, with a monthly payment of £2020. In May 2010, Imran paid £1,500 towards the Sutherland expenditure, to include £600 that Rizwan had paid in March 2010 to “offset against his loans”. Imran also testified that he contributed £800 thereafter, albeit not every month, and he denied defaulting on his loans, save on one payment.

83. I found Imran and Javaid’s evidence on this aspect problematical: on their case, they remained joint beneficial owners of Sutherland and, to use Javaid’s rubric, the ‘landlords’. If correct, they remained responsible for paying the mortgage and other household expenses and yet they passed that responsibility to one of their ‘tenants’ and required him (and Abid) to take on an even greater financial burden. Javaid did not seem to see the problem. His response in oral evidence to Rizwan and Abid paying more to the Sutherland expenses was to say “as they should”, resonating with his unrealistic view that they were merely paying ‘rent’ (at [41] above).

84. Imran did see the problem but more as a personal reflection on his financial difficulties rather than as one of the supposed joint owners of Sutherland. He initially tried to deflect his passive role in the management of the Sutherland household expenditure by saying that he had diabetes. As with his explanation for not going onto the Sutherland mortgage at the outset in 2006 (at [69-71] above), this was unconvincing. When questioned further, Imran accepted the (again) more plausible explanation: Imran was self-employed and he received money irregularly.

(xi) The Devonport sale proceeds - July 2010

85. In July 2010, Abdul and Naseem sold Devonport, realising net sale proceeds of £107,266.50. The Devonport sale is not immediately relevant to the present dispute but both parties rely upon it to support their arguments concerning the alleged agreement with respect to the beneficial ownership of Sutherland. The sale is also relevant in a different sense. Standing back from the detail of the evidence, the division of the Devonport sale proceeds between some of the Kanval family members seems to have marked the start of the breakdown of the relationship between Imran, Javaid and Rizwan.

86. Imran testified that his father wanted to give him the entirety of the Devonport sale proceeds. Although a very generous offer, Imran said he did not want to take it up unless his father told everyone else about the decision first (Imran WS at [83]). Naseem testified that Imran was offered £10,000 but he declined this. He was not offered the whole amount.

87. There is no dispute that Rizwan was paid £45,000 from the sale proceeds and he used this to pay down the Sutherland mortgage by £44,747. Rizwan also received a further payment of £4,740. He could not explain this in oral evidence. Nor, initially, could Naseem although she did go on to testify that Rizwan had paid for a flight to Pakistan in June 2010 when a fight broke out in her in-laws’ family. Rizwan also received further payments of £7,000 and £3,000. Rizwan and Naseem both testified that Abdul had asked Rizwan to hold onto this for him until it was needed back.

88. Urfan also received £10,000 from his parents. Although the Claimants submitted that Rizwan produced no documentary evidence of the payment, this does not appear to be disputed by the Claimants (Imran TWS at [34]; Javaid TWS at [31]). Urfan testified that he later paid this back to his mother.

89. Finally, it is common ground that Javaid received £40,000, albeit £2,230 of this represented repayment of Javaid’s expenses on the Devonport renovation.

(xii) Imran and Javaid’s case on the Devonport sale proceeds

90. Javaid and Imran testified that the intention of the Devonport renovation and sale was to allow the other brothers to buy their own properties but that Rizwan prevented this by ‘misleading’ his father to part with a large chunk of the sale proceeds to pay down the Sutherland mortgage. Based on a conversation with his father, Javaid said that Rizwan had managed to obtain the £45,000 payment by telling Abdul that the mortgage was in default and that the family might be ‘kicked out’ of Sutherland. Imran’s evidence was to the same end, albeit he was not privy to the conversation between Javaid and his father, only learning this later. Both testified that using the money to pay down the mortgage by nearly £45,000 made very little difference to the monthly mortgage payments. However, the Claimants submitted that such a large payment against the capital would benefit someone who intended to redeem the mortgage, as Rizwan did the following year. Javaid testified that he received the £40,000 from his father to prevent Rizwan’s demands of Abdul for more money (Imran WS at [84-86]; Javaid WS at [86-90]).

91. Attempting to unravel these points, I do not accept Javaid’s testimony that he received the £40,000 to prevent Rizwan obtaining further money from Abdul. Unsurprisingly, Rizwan denied this but so too in oral evidence did Naseem - she was effectively one of the donors. Moreover, Imran and Javaid offered alternative explanations in their original statements. Imran explained that the £40,000 payment to Javaid represented (roughly) £27,500 for the historical rent on Princess Road (at [65] above), £2,500 for money spent by Javaid on Devonport and £10,000 to use towards a deposit for a house (Imran TWS at 34). Javaid said that the £40,000 payment was “part repayment and part gift” (Javaid TWS at [35]).

92. Although Imran attempted in oral evidence to reconcile the different explanations, and the Claimants disavowed in closing argument the historical rent explanation, I found both efforts unpersuasive. I accept that Javaid was upset when he learnt that Abdul had paid money to reduce the mortgage. Rizwan said as much in oral evidence when he explained that the £40,000 payment was made to “calm down Javaid”. Rizwan said Javaid needed calming that “there will be a deposit for him when he buys.” Naseem confirmed in oral evidence that Abdul paid Javaid the money to use as a deposit for a new house. Imran’s original statement also indicates the partial use of those monies for that purpose. Finally, Urfan stated in oral evidence that he accompanied his father to the bank when he transferred the £40,000 to Javaid and Abdul suggested to Urfan investing his £10,000 share into Javaid’s future property. In my view, that was the straightforward and correct explanation for Javaid receiving the £40,000 - to buy a house.

93. I also do not accept Javaid’s evidence that Rizwan ‘misled’ his father about the Sutherland mortgage. On the Claimants’ case, they were the sole beneficial owners of Sutherland and they, not Rizwan, would benefit from any mortgage reduction. Moreover, it is common ground that the mortgage payments were only reduced slightly such that, even on Rizwan’s case, the benefit to him was not significant. It therefore makes no sense for Rizwan to have gone out of his way to dupe his father into making a payment which would be of no or limited personal gain. Although Rizwan did take over legal ownership of Sutherland in late 2011, he could not have known this more than a year before it happened.

94. Nor do I accept that the intention of the Devonport sale was to allow the ‘other brothers’ (ie: Rizwan and Urfan) to buy their own properties. In this regard, I prefer Abid’s more considered oral evidence that his parents’ philosophy was to enable their children to buy a property, “depending if they wanted to move out or not.” When the Devonport refurbishment began, and for some considerable time thereafter, none of the Kanval brothers living at Sutherland had apparently intimated a desire to leave. By the time Devonport was sold, both Javaid and Urfan had moved out but they were still only renting. They later received nearly 50% of the Devonport sale proceeds between them. Javaid confirmed in oral evidence that he used his share of the Devonport sale proceeds in the later purchase of his new house.

95. In May 2011, Javaid renewed his tenancy on Albany Road.

(xiii) The second disputed family meeting - August 2011

96. Rizwan claims that a further family meeting was held in August 2011 attended by Imran, Javaid, Rizwan, Urfan, Raza, Abdul and Naseem. In his statement, he put the meeting at 3 August but changed this to 6 August in oral evidence, apparently realising it must have taken place at the weekend. Rizwan said it was here that Javaid presented the Spreadsheet showing each brother’s equity interest in Sutherland. Rizwan says he agreed to take over the mortgage and utility bills if the other equity holders agreed to give up their interest in Sutherland in return for a fixed payment calculated on the basis of the Spreadsheet. Imran, Javaid, Urfan and Abid agreed to this proposal. Rizwan had also offered to give up his interest for £40,000 but Javaid declined this, preferring to buy his own property closer to his work.

97. In oral evidence, Rizwan also explained how he was surprised to see that the Spreadsheet showed Imran and Javaid with a higher equity share (26.2%) than him (20.0%), both because Imran had not contributed financially when he had taken time off to work on the Osterley renovations and because Rizwan had borne the burden of paying the Sutherland mortgage once Javaid had left in May 2010. Rizwan said that he was paying too much towards the mortgage himself. Javaid had done a ‘hardstop’ by ceasing to contribute and Imran was in financial difficulties and could not make the payments. Rizwan testified that he therefore queried the percentage shares. He also queried the suggested value of Sutherland put by Javaid at £650,000, with Rizwan suggesting £575,000 instead. Nevertheless, since Javaid was looking to buy and required a deposit, he accepted Javaid’s value of £53,265 for his share.

98. No date was agreed for payment of the £53,265. It was a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’. He expected he would have the money by the end of the month but there were no guarantees. He had been waiting for money from the sale of his shares in Asperity Employee Benefits Ltd (“Asperity”) for some time and his prior expectations in that regard had been disappointed. As for the other brothers (Imran, Urfan and Abid), their shares were agreed to be those stated on the Spreadsheet but, again, the payment date was not agreed. It was understood that they would be paid “as and when”.

99. Urfan, Raza, Abid and Naseem referred to this meeting in their statements in similar terms (Urfan TWS at [3-6]; Abid TWS at [6]; Raza TWS at [8]; Naseem TWS at [10]) and in oral evidence, with some differences between their accounts. Urfan put the month of the meeting at August 2011 because of the date on the Spreadsheet which Javaid produced at the meeting. Urfan said that he had questioned why his equity share shown on the Spreadsheet (18.6%) was lower than the others. Javaid told him it was because of gaps in Urfan’s contributions. Urfan did not recall any haggling at the meeting although he did refer in his statement to the difference between Rizwan and Javaid on the Sutherland value. Urfan also confirmed his understanding that he would receive the value of his share when Rizwan was in funds. Urfan testified that Javaid’s use of the £40,000 from his parents to buy out his share was not discussed at the August meeting.

100. Abid said he remembered the meeting being in August 2011 because Javaid had popped over to Sutherland in July while the family was on holiday to organise the meeting and said he would prepare the Spreadsheet. Javaid later presented this at the meeting. Abid said there was no haggling about the equity shares but Rizwan did believe he deserved more. However, there was haggling about the value of Sutherland as used in the Spreadsheet. Abid’s 8.9% share on the Spreadsheet was higher than the 8% originally ‘gifted’ so he was not ‘going to complain’.

101. In oral evidence, Raza said that the meeting took place in August 2011 but he did not mention the month in either of his statements, merely stating it took place in “late 2011”. Although Raza did not have an interest in Sutherland, he had come back to see everyone and was told there was a family meeting. He was not surprised this issue came up. He knew Javaid was looking to buy a property. Raza too said that Javaid produced the Spreadsheet at the meeting.

102. Finally, Naseem’s related oral evidence was brief but she too confirmed that Javaid came to the house and gave the “paper” to everyone - apparently referring to the Spreadsheet. Javaid said that his share was valued at £55,000, less for the other brothers. Naseem was shown the Spreadsheet in the witness box. Although she could not read the whole document, she was able to read that part with the names of her sons and the allocation of their shares. She confirmed that this was the document produced by Javaid at the meeting.

(xiv) The Spreadsheet

103. The ‘original’ of the Spreadsheet produced by the Defendant on disclosure was made available at trial and inspected by the parties then and by me. On its face, this looked like an A4 print out of a landscape document produced electronically. It had fold lines and staining. According to Urfan, this was the copy of the Spreadsheet which he had retained after Javaid gave it to him at the August 2011 meeting. The Spreadsheet has the following heading:-

![]()

104. The Spreadsheet has the following footer:-

![]()

105. These references suggest that the document was created electronically as an excel spreadsheet on 31 July 2011 and that the version produced at trial was created or printed on 3 August 2011 at 17:35 hours.

106. The remainder of the document is contained within a rectangle and is divided into four sections. The first section comprises a row running along the top left side of the rectangle:-

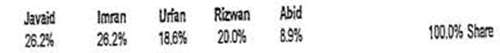

107. On its face, this suggests a division of Sutherland ownership into percentage shares, with Javaid and Imran each allocated 26.2%, Urfan 18.6%, Rizwan 20.0% and Abid 8.9%. Beneath that row is the following:-

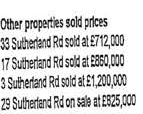

108. This appears to list comparable properties in Sutherland Road and their respective sold or sale prices. Beneath that are the following workings:-

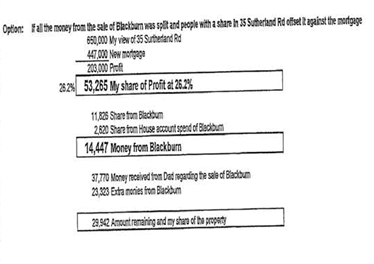

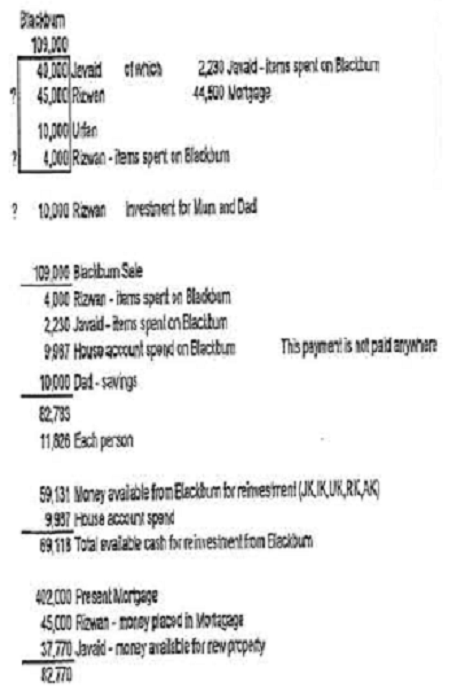

109. On its face, the author of the Spreadsheet indicates “My view of 35 Sutherland Rd” - apparently its market value - as £650,000. The workings that follow then set out the additional money required for the purchase of “My share of Profit at 26.2%” in Sutherland assuming a prior share in the Devonport sale proceeds, a “New mortgage” balance of £447,000 (apparently disregarding the £45,000 paid down by Rizwan on the existing mortgage) and the prior receipt of £37,770 “from Dad regarding the sale of Blackburn.” The final section of the Spreadsheet (to the far right) contains further workings, principally about the Devonport sale proceeds:-

110. The reference in these workings to “£11,826 Each person” corresponds to, and appears to show the underlying calculation for, the “£11,826 Share from Blackburn” indicated in the prior workings, apparently assuming a prior split of the Devonport sale proceeds between seven (presumably Javaid, Imran, Rizwan, Urfan, Abid, Abdul and Naseem). It also records “£37,770 Javaid - money available for new property”, corresponding to “40,000 Javaid of which 2,230 spent on Blackburn” in the same workings and to “37,770 Money received from Dad regarding the sale of Blackburn” in the prior workings.

111. Putting the different sections together, the Spreadsheet therefore appears to indicate the allocation to Javaid of a 26.2% share in Sutherland, the calculation of the value of that share at £53,265 and one option for its realisation, including the use (after deduction of a prior split of the Devonport proceeds) of the £37,770 paid to Javaid. As already noted, Javaid and Imran vehemently deny that Javaid prepared the Spreadsheet or that there was any meeting in August 2011 at which this was produced.

3. ALLEGED AGREEMENT TO SHARE IN SUTHERLAND

112. Having reviewed the evidence to August 2011, I now turn to the central question of whether, as Rizwan alleges, there was an agreement for all the brothers to share in the beneficial ownership of Sutherland or whether, as Imran and Javaid allege, it was understood and agreed by Rizwan that Imran and Javaid were the sole beneficial owners. I should add that a number of matters post-dating August 2011 are relevant to that question as well. I have taken fully into account “[t]he parties’ whole course of conduct in relation to the property …… in determining their shared intentions as to ownership” (at [16] above) but, for convenience only, I have addressed those later matters below in their correct chronological order.

(a) Factors supporting the alleged Osterley/ Sutherland agreement

113. Since the agreement alleged by Rizwan with respect to Sutherland was said merely to repeat the agreement for Osterley, I accept the Claimants’ submission that Rizwan can only prevail on this central question if he satisfies me of the existence of the latter. I now examine the various matters relied on by the parties in support of their rival contentions on that central question, together with those further matters I consider material.

(i) Limited equity

114. Imran and Javaid did not come to Osterley with a large cash deposit. Although they used some savings to acquire Osterley, the vast majority of the purchase price came from secured and unsecured loans. They were highly leveraged. They acquired very limited equity in Osterley and they were not making capital repayments on the (interest only) Abbey National mortgage. They would therefore be making only a limited sacrifice by agreeing to share the beneficial ownership more widely among all the brothers.

(ii) Interdependence

115. When they came to Osterley, Imran and Javaid had not long been in London themselves and had not long finished their studies. Before they bought, they were sharing a bedsit. Although I accept that they opened up Osterley to their brothers to share with them the opportunity living in London afforded, I am satisfied that Imran and Javaid would have had difficulty managing Osterley financially without the other brothers’ contributions. The flat was more expensive than the price at which they were looking to buy and, even then, it apparently needed renovation to the extent that Imran later had to give up work for a not insignificant period. Imran and Javaid could have rented rooms in the flat and Javaid said he had looked into that possibility but it seems doubtful at least whether they could have secured suitable tenants or rented when Osterley needed renovation, this would be disruptive to any tenants and the flat did not have some basic household items such as mattresses and certain furniture which were only bought later. By contrast, their younger brothers would be more likely to put up with more basic conditions and disturbance and would be able to help in the renovations at no cost. In this regard, I accept Rizwan’s evidence that Imran and Javaid could not have managed Osterley by themselves. They needed their other brothers just as much as the other brothers needed Imran and Javaid.

(iii) The nature of the brothers’ contributions

116. I reject the suggestion that the brothers’ financial contributions were, as Javaid put it, ‘rent’. Rents are determined by market forces and not generally fixed by reference to, or do not vary with, the level of household expenditure. That the brothers’ contributions were much more than ‘rent’ and, in fact, evidenced their common intention to share rateably in Osterley (later Sutherland) is evident from the following:-

a. The brothers contributed to the fullest range of household expenditure, including that necessary to maintain ownership of the flat, namely the mortgage, the endowments, the ground rent and the service charge;

b. The expenses also included items of a ‘capital’ nature such as the Osterley renovation costs. Although Imran and Javaid may not have recouped all they money they ‘fronted’ for the renovations, as noted (at [58] above), their brothers contributed significantly towards them. Those renovations likely increased the value of Osterley;

c. To the same end, the brothers also contributed, without charge, their time and labour to assist in those renovations;

d. The contributions also reflected the shared familial nature of their arrangements, with all the brothers contributing to family expenses beyond those immediately benefitting Osterley or themselves;

e. Despite the informality of their dealings and forbearance for late payment, the expenses were carefully recorded in the house notes down to the smallest of items, split between the working brothers, payment demanded monthly and payment shortfalls carried forward;

f. A ‘landlord’ does not generally pay rent to himself but Imran and Javaid shared with all the other working brothers in the mortgage, food and utility bills; and

g. When Raza moved out in 2002, he ceased contributing to the Osterley household expenditure. Abid apart, his brothers who remained shared the increased financial burden by paying a larger share.

(b) Factors militating against the alleged Osterley/ Sutherland agreement

117. The above matters are consistent with an agreement for the brothers to share in the beneficial ownership of Osterley and, later, Sutherland in proportion to their respective contributions. However, the Claimants identified a number of matters arising in the evidence which they say indicated otherwise.

(i) Fixed contributions

118. The Claimants argued that a fixed payment regime such as that initially operating at Osterley militated against shared beneficial ownership. Whether that is so will depend on the nature and amount of the payments concerned, as well as the context in which they were made. Having regard to the level of costs shown in the later house notes, but factoring in the reduced mortgage and endowment payments for much of the earlier period, I consider it likely that, with five working brothers contributing, their fixed payments generally did cover the Osterley expenses. Moreover, as I have found, the brothers contributed to the fullest range of expenses, including those incidental to the ownership of Osterley and those of a capital nature.

119. In these circumstances, the fact that, for some months, there may have been shortfalls (for example, on account of the increasing level of renovation costs or exceptional items such as the unexpected service charge referred to in evidence) does not prevent a finding of a common intention to share in the Osterley equity in proportion to their contributions. To the contrary, the fact that the brothers moved, without apparent demur, to a variable split of the expenses once such shortfalls became more likely with the increasing financial impact of the Osterley renovations is consistent with such an intention.

(ii) Use of bank accounts not controlled by the brothers

120. In a similar vein, the Claimants argued that the use of Javaid’s personal HSBC account for payment of the Osterley mortgage and of the house account in the joint names of Imran and Javaid for payment and reimbursement of the house expenses also militated against a common intention to share in the beneficial ownership. However, as Imran explained, the brothers used the house account as their ‘personal bank account’. Although not signatories to, or exercising formal authority over, that account, they were still able to use it, apparently freely, for their benefit. In my view, this too is consistent with such a common intention. The same cannot be said for Javaid’s HSBC account, from which the mortgage payments were made. However, the brothers all paid into the house account, including for the mortgage. The fact that the person in charge of the household expenses then paid that particular expense from a different account in his name seems of little consequence, as shown by the later switch to the house account for payment of the Sutherland mortgage (at [66] above) and, later still, once Javaid had moved out, to Rizwan’s account (at [81] above).

(iii) Ignorance of Osterley sale proceeds/ equity share

121. Urfan testified that he did not know the precise amount of the Osterley sale proceeds and how the majority had been paid into Javaid’s Halifax savings account. However, he knew the price at which Osterley had been marketed. Likewise, he did not know, or enquire about, the size of his share in Osterley. He said he did not need to know because he was not in a position to buy a property. Similarly, when Raza moved out of Osterley in 2002, there was no attempt by him to ‘tally up’ his share and obtain payment for it then. Nor was he informed of the amount he contributed to Osterley, although he testified that Javaid did inform him of the value of his share. Finally, Rizwan confirmed that a running tally of the brothers’ relative contributions to Osterley was not maintained. He said this was not required because Javaid had all the information. He also could not recall if he knew that the majority of the Osterley sale proceeds had been paid into Javaid’s Halifax savings account. He was also unaware of the later payment of the £5,000 retention.