Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Original Beauty Technology Co. Ltd & Ors v G4K Fashion Ltd & Ors [2021] EWHC 3439 (Ch) (20 December 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2021/3439.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 3439 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWHC 3439 (Ch)

Case No.IL-2018-000105

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (ChD)

Royal Courts of Justice, Rolls Building

Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL

Date: 20 December 2021

Before:

DAVID STONE

(sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between:

|

|

(1) ORIGINAL BEAUTY TECHNOLOGY COMPANY LIMITED (2) LINHOPE INTERNATIONAL LIMITED (3) RETAIL INC LIMITED (in liquidation)

|

Claimants |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

(2) CLAIRE LORRAINE HENDERSON (3) MICHAEL JOHN BRANNEY (4) OH POLLY LIMITED

|

Defendants |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Ms Anna Edwards Stuart and Mr David Ivison

(instructed by Mono Law Limited) for the Claimants

Mr Chris Aikens (instructed by Fieldfisher) for the Defendants

Hearing dates: 25, 26, 27 and 29 October 2021

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Approved Judgment

Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment is to be handed down by the deputy judge remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email and release to BAILII. The date for hand-down is deemed to be 20 December 2021.

DAVID STONE (sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court):

- Damages inquiries are rare in intellectual property cases. This case may help explain why. What ought to have been a comparatively simple exercise of trying to put the Claimants into the position they would have been in had the infringement not occurred became marred in detail and side issues. This judgment is therefore of necessity longer than I would wish.

- The Claimants (by which I mean the First and Second Claimants, the Third Claimant being in liquidation and taking no part in proceedings) sell bandage and bodycon dresses and other garments under the brands House of CB and Mistress Rocks. House of CB competes with the Defendants (where it is necessary to distinguish between them I will do so), who also sell bandage and bodycon dresses and other garments, but under the brand Oh Polly. 15,393 Oh Polly garments sold by the Defendants infringed unregistered design rights owned by the First Claimant. The Claimants therefore sought damages under three heads:

- Before me, the parties referred to (a) and (b) above as “standard damages” and (c) as “additional damages”. The Defendants denied that lost profits damages were payable at all. The Defendants accepted that a reasonable royalty was payable, but they valued that royalty at approximately £15,000, or £1 per infringing Oh Polly garment. The Defendants also accepted that additional damages were payable, but they said that I should order no more than a 20% uplift on the reasonable royalty, which they submitted is approximately £3,000, or 20p per infringing Oh Polly garment. On the other hand, the Claimants submitted that they should receive approximately £275,000 in standard damages, to be “topped up” to approximately £500,000 with additional damages to reflect the flagrancy of the infringement. Thus, the parties were far apart.

- This is the ninth judgment I have given in these proceedings. I do not set out here all the relevant background, which can be found in those earlier judgments. For present purposes, it is sufficient to record as follows.

- After a trial over eight days, on 24 February 2021 I gave judgment in relation to the alleged infringement of UK unregistered design rights (UKUDR) and Community unregistered design rights (CUDR) in 20 selected garments (the Selected Garments) out of a total of 91 garments, which rights the Claimants said were infringed by the Defendants. That judgment can be found at [2021] EWHC 294 (Ch) (the Main Judgment). I found that seven of the Selected Garments infringed both UKUDR and CUDR, and that 13 infringed neither right. I dismissed the passing off claim. I set out below some of my other findings from that judgment relevant to this damages inquiry.

- A form of order hearing took place on 1 April 2021: I gave a short ex tempore judgment (which can be found at [2021] EWHC 836 (Ch)) rejecting the Defendants’ request for declarations of non-infringement. An issue arose after the form of order hearing in relation to the various colourways of some of the seven infringing Selected Garments, and I dealt with that in a judgment which can be found at [2021] EWHC 953 (Ch). I dealt with a further issue relating to costs where a Part 36 offer has been made: that judgment can be found at [2021] EWHC 954 (Ch). Following the Claimants’ election of a damages inquiry in relation to the infringing Selected Garments, I heard a CMC on 24 June 2021. I allowed the Claimants to amend their pleadings for the reasons set out at [2021] EWHC 1848 (Ch). Following these amendments, the Defendants then admitted that a number of the further pleaded garments infringed.

- The Claimants’ Points of Claim in the damages inquiry were served on 20 August 2021. Points of Defence were served on 7 September 2021. There was a hearing before me on 10 September 2021 at which I ordered the Claimants to provide responses to the Defendants’ Request for Further Information dated 24 August 2021: that was duly done on 17 September 2021. Also on 10 September 2021, I refused the Defendants’ request to institute the disclosure pilot and refused most of the Defendants’ requests for specific disclosure. That judgment can be found at [2021] EWHC 2555 (Ch). The Court of Appeal refused the Defendants’ application for permission to appeal.

- On 1 October 2021, I refused the Defendants’ application to vacate the hearing of this damages inquiry, for the reasons set out at [2021] EWHC 2632 (Ch). The Court of Appeal refused the Defendants’ application for permission to appeal.

- On 15 October 2021, I refused the Defendants’ application for specific disclosure in relation to this damages inquiry: see [2021] EWHC 2748 (Ch).

- The inquiry was heard remotely at the request of the parties, over five days. The parties used the CaseLines database so that documents were available electronically to the court and to witnesses. The Claimants were represented by Ms Anna Edwards-Stuart and Mr David Ivison of counsel (instructed by MonoLaw) and the Defendants were represented by Mr Chris Aikens of counsel (instructed by Fieldfisher).

- For ease of reference, each garment in the proceedings has a number. The Claimants’ garments in which they assert UKUDR and CUDR are pre-fixed with the letter C. Where a part design is claimed, an asterix is used. The Defendants’ garments which are alleged to infringe mostly have the corresponding number, prefixed with the letter D (thus, D2 was alleged to infringe design rights in C2 etc). The evidence occasionally used the names of the garment (the Claimants’ garments having girls’ names, and the Defendants’ garments being named with puns or plays on words).

- The Claimants relied on two witnesses of fact.

- Ms Joanna Richards is actively involved in running the House of CB business. She primarily gave evidence in relation to her views on a hypothetical negotiation for a reasonable royalty, and the impact of the dispute on the Claimants. Ms Richards had also given evidence at the liability trial: she was cross-examined in that trial, and at this inquiry. Counsel for the Defendants submitted that Ms Richards “was a thoroughly unhelpful witness”, but said further that, “for the most part”, that was not her fault. He submitted that her role at House of CB was limited, and that she did not make key decisions in relation to the business. Even if these submissions were true, I do not consider that this criticism can be made of Ms Richards. I found her to be an honest witness, doing her best to assist the court. The areas where counsel for the Defendants said she lacked knowledge turned out to be largely irrelevant to the issues to be determined in the inquiry.

- Further, on 21 October 2021, the Defendants’ solicitors wrote to the Claimants’ solicitors in the following terms:

- The Claimants’ solicitors did not respond to this letter, which was issued one clear day before the inquiry began.

- Under cross-examination, it became apparent that Ms Richards did not know which garments were manufactured at what factory. She had not researched the issue in order to be able to answer the Defendants’ questions. Ms Richards gave evidence that the factories concerned made the decisions on where garments were to be manufactured, and they had all closed more than two years ago.

- Counsel for the Defendants criticised Ms Richards trenchantly for “not check[ing] where the garments were manufactured even though she knew [the Defendants] wished to have that information”. Counsel for the Claimants submitted that I should reject this criticism of Ms Richards: witnesses should be cross-examined on their evidence, she submitted, and Ms Richards had given none in relation to the factories. It is not for witnesses to have to study up on things outside their knowledge in order to be able to answer questions under cross-examination - and they should not be criticised for failing to do so. I accept those submissions.

- Further, counsel for the Claimants submitted that this was the third occasion on which the Defendants had sought to discover which factory made which garment. First, the Defendants had made an application for specific disclosure, which I had already rejected. Second, the Defendants had asked for the information in an RFI, which I had already dismissed. It therefore follows that I accept her submission that no criticism can be made of Ms Richards for not having to hand information outside her knowledge that the Defendants had twice failed to secure by other means, and which was, in any event, of limited, if any, relevance to this inquiry.

- Mr David Waters is an accountant at UKTS Limited, and has acted as the UK accountant for the First Claimant since it was incorporated in July 2011, providing accounting and taxation advice. Mr Waters provided calculations as to the Claimants’ lost profits. He was cross-examined. Counsel for the Defendants described Mr Waters as a fair witness who did his best to help the court. I agree with that assessment.

- The Defendants relied on one witness of fact.

- Dr Michael Branney is the Third Defendant and the managing director of the Oh Polly business. He also gave evidence at the liability trial. Relevantly for present purposes, he gave an affidavit on 26 May 2021 setting out Island Records v Tring information to enable the Claimants to make an election of an account of profits or a damages inquiry. He then made two further witness statements, a third on 22 July 2021 and a fourth on 18 August 2021 providing further details of sales of the infringing Oh Polly garments. His fifth witness statement, his evidence in the damages inquiry, was filed on 4 October 2021.

- As a defendant in the proceedings, he had also signed each of the pleadings filed on behalf of the Defendants.

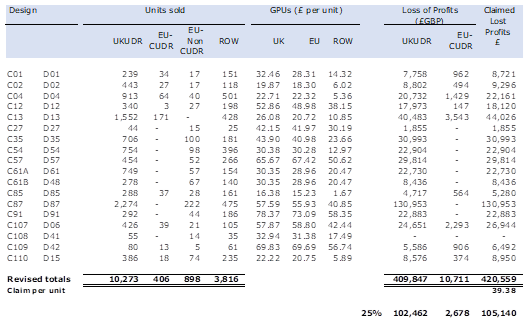

- Counsel for the Claimants described Dr Branney as “a dishonest litigant and witness”. I have regretfully come to the conclusion that Dr Branney was a dishonest witness, and that his evidence is not to be believed unless corroborated by independent means (such as contemporaneous documents). Given that finding, I need to set out in some detail the relevant background. There are two issues, which are interlinked. One relates to the cessation or otherwise of sales of certain Oh Polly garments. The other relates to the total number of infringing Oh Polly garments sold by the Defendants which Dr Branney set out in his Island Records affidavit.

- The Defendants’ Defence was signed by Dr Branney in January 2019. An Amended Defence was signed by Dr Branney in January 2020. Both included at paragraph 76 a statement that the Defendants “have ceased all sales” of certain garments “and do not intend to recommence sales of such garments”.

- The Amended Defence to the Points of Claim was signed by Dr Branney on 21 October 2021. Paragraph 19G of the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim states:

- The reference to 66 of 87 garments was a reference to Annex D89 to the original Defence to the Particulars of Claim, referred to at paragraph 76 of the original Defence. Of the 66 garments listed in Annex D89, twelve remain in issue in the litigation: D2, D6, D12, D13, D15, D27, D35, D41, D42, D54, D57 and D61.

- During Dr Branney’s cross-examination, it emerged that sales of many of the 66 garments referred to in the Defence, the Amended Defence and the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim had not in fact ceased, but rather, after a brief hiatus, had commenced again. Of the garments still relevant in these proceedings, only sales of D41 had in fact ceased by January 2019 and not recommenced. Sales of D54 and D57 had ceased some time earlier at the end of their sales cycle.

- Dr Branney stated under cross-examination that he had instructed that the garments be removed from the Oh Polly website but that it later transpired that a person in his team responsible for merchandising had put the garments back on sale without his knowledge. He had discovered on or about 26 September 2021 that sales had not ceased as claimed.

- The result of sales not having ceased as claimed was the second issue to which the Claimants referred, namely, that the total sales of infringing garments set out in Dr Branney’s Island Records affidavit and his third and fourth witness statements did not record the additional sales after January 2019. Those figures (which were supposed to include all sales by the Defendants of the infringing garments) were therefore wrong.

- Dr Branney’s position was that he did not know at the time they were signed that:

- As set out above, it was Dr Branney’s evidence that he discovered the additional sales on or about 26 September 2021. However, whilst he raised these additional sales with those advising the Defendants (it is to be recalled that Dr Branney is the Third Defendant), no letter was written to the Claimants alerting them to the issue. Rather, Dr Branney, having raised it with his legal team, took two steps. First, he signed the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim on 21 October 2021. This document repeated the statement that sales of the relevant garments had ceased by January 2019, a statement which by this time Dr Branney knew to be false. Second, he signed a fifth witness statement that does not mention the discovery of the extra garment sales after January 2019. In relation to total sales and his Island Records affidavit and third and fourth witness statements it says this (references to the CaseLines database omitted, emphasis added):

- The Defendants rely on the last sentence, which I have italicised, to submit that they brought to the Claimants’ attention the under-reporting in Dr Branney’s Island Records affidavit and third and fourth witness statements.

- Then, at paragraphs 10, 11 and 12 of his fifth witness statement, Dr Branney recorded the steps taken since his third and fourth witness statements to develop a software program to allow for the interrogation of all individual sales records by stock keeping unit (SKU). He defined the software program as “the Program”. He then went on to discuss the different systems used by the Defendants, including Linnworks, Braintree and Magento, and concluded at paragraph 16 (emphasis added):

- The Spreadsheet referred to is a document provided to the Defendants in a Civil Evidence Act notice. I return to that document below.

- Again, the Defendants relied before me on the italicised phrase to support their submission that the discrepancies in garment figures were brought to the Claimants’ attention. In his closing skeleton argument, counsel for the Defendants wrote:

- For the reasons set out below, I consider that assertion to be unsupportable.

- Dr Branney was well aware of the need to be honest and frank in his evidence. First, he had given evidence in the liability trial about which I was critical. At paragraphs 60 and 61 of the Main Judgment, I said this:

- Dr Branney was therefore aware of the importance of honest evidence and the importance of being careful before signing a statement of truth.

- Second, the evidence of the Second Defendant, Ms Henderson, in the liability trial had been criticised (I found that she had lied) and contempt proceedings have been threatened by the Claimants. This became a major issue in the proceedings over the spring for reasons unrelated to the inquiry, with significant correspondence exchanged between the parties. Dr Branney gave instructions on that correspondence. So, again, he was well aware of the possibility of contempt proceedings against untruthful witnesses.

- Third, Dr Branney said that he had been very careful with his evidence. He said he had been “very careful” to check through the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim, since it was a document verified by a statement of truth.

- Unfortunately, I am unable to conclude otherwise than that Dr Branney has fallen short in his honesty to the court. At least by the time he signed his fifth witness statement, he knew that his Island Records affidavit and his third and fourth witness statements were incorrect, and yet he made no attempt to draw this to the attention of the court or the Defendants. I do not for one moment consider that the italicised phrases I have highlighted above were sufficient. They merely say that the figures presented are presented with greater confidence/certainty. They do not even suggest that the previous figures were wrong, and there is no mention at all of the additional sales of infringing garments after it was claimed that sales had ceased. Rather, I understand Dr Branney’s witness statement simply to refer to the Spreadsheet of figures provided to the Claimants via a CEA Notice. He, and the Defendants, then left it to the Claimants to interrogate those figures should they wish. It should be noted that one sheet in the Spreadsheet contains 22,263 lines of data, which would not have been easy to interrogate - it was only through the Claimants’ detailed review of those data that Dr Branney’s earlier inaccurate affidavit and witness statements came to light.

- Counsel for the Claimants also pointed to paragraph 129 of counsel for the Defendants’ opening skeleton argument where he addressed the timing of the infringements for the purposes of additional damages. That document records:

- It is usual for Defendants to review counsels’ skeleton arguments prior to submission to the court, and I can only assume that Dr Branney reviewed this document, which is dated 22 October 2021. Again, by this point, Dr Branney was well aware that, whilst sales stopped in January 2019, for most of the relevant garments they had commenced again. The skeleton argument makes no reference to that fact - indeed, it seeks to make a virtue from the cessation of sales.

- Counsel for the Claimants also submitted that Dr Branney was given an opportunity to explain himself early in his cross-examination, but chose not to do so. She asked him:

- Even as late as this point, over a month after discovering the error and whilst giving testimony to the court, Dr Branney did not acknowledge that the Defendants’ pleadings in the liability trial and in this inquiry were wrong, and that his affidavit, and now three witness statements (his third, fourth and fifth) were wrong/misleading. I add that shortly after having taken the affirmation, Dr Branney was asked by counsel for the Defendants if there were any corrections he wished to make to his fifth witness statement. He made one. He was then asked: “Subject to those corrections, are the contents of this statement true to the best of your knowledge and belief?” Dr Branney answered “Yes, they are, my Lord”.

- Dr Branney was cross-examined further in relation to the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim. He said he checked it “very carefully”. That document includes the statement “by the time of the service of the original Defence in January 2019, the Defendants had stopped selling 66 of the 87 garments then in issue”. This statement was untrue, and by the time he signed the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim, Dr Branney knew it to be untrue. He did not in cross-examination suggest that he had overlooked this statement - rather, he said “I did not understand that I was signing as if it was a previous date” and “as I stated before, I did not understand that I was signing it as if I had gone back to that date, and I was satisfied that as of 21st October 2021 it was absolutely true”. So on his own testimony, he considered the false statement, and concluded that whilst it had not been true when the Amended Defence was signed in January 2020, sales had ceased by October 2021 and that was enough. But that is not what the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim says - it says that garment sales had stopped in January 2019, which by this time Dr Branney knew not to be true.

- I am prepared to accept Dr Branney’s evidence that he was not aware that the Amended Defence in the liability trial was wrong at the time he signed it under a statement of truth. I am also prepared to accept that Dr Branney was unaware that his Island Records affidavit and his third and fourth witness statements were false at the time they was executed and filed. But by the time Dr Branney (a) signed his fifth witness statement; (b) signed the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim; and (c) gave his oral testimony under affirmation, he was well aware that his affidavit and witness statements were wrong and misleading and that the statement that sales had ceased in January 2019 was wrong, and he chose not to correct those errors in a way which would have been readily perceptible by the Claimants. It is also, regretfully, my finding that those omissions were dishonest.

- The affirmation Dr Branney took on giving his oral testimony included a solemn and sincere affirmation to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Dr Branney has not done so. He has failed to comply with his affirmation. He was not honest with the court until asked specific questions about the additional sales. He had plenty of opportunities to come clean about the errors, but chose not to do so. I therefore find that his evidence is not to be trusted, and I will accept it only where the Claimants wish to rely on it, or it is corroborated by an independent source. It does not matter that the correct figures were eventually provided, nor that the Claimants have not suggested that they might have elected differently had the Island Records affidavit been correct, and it does no credit to the Defendants’ counsel for suggesting as much in his closing skeleton argument. This was a serious failure to correct two errors once they had been discovered.

- Mistakes sometimes occur. But when a material mistake in a pleading, an affidavit or a witness statement is discovered, the relevant party/ies and/or deponent/s have a duty to bring that mistake to the attention of all other parties, and of the court, as soon as practicable. What should have happened in this case is that, having discovered the additional sales on 26 September 2021, the Defendants should have written through their solicitors to the Claimants, setting out the errors, and then sought to agree a way forward, which may have included amended pleadings (this at least was done, on the final day of the inquiry) and a further witness statement setting out in detail how the error occurred and how it was discovered.

- After the conclusion of the inquiry, and after the above paragraphs of this judgment had been written, I received a sixth witness statement from Dr Branney. That witness statement sought to explain his oral evidence under cross-examination. Dr Branney wrote:

- Dr Branney had no permission to file such a further witness statement. The Claimants objected to it. I decline to admit it into evidence. Many witnesses who are cross-examined before the court would welcome an opportunity, after reflection, to explain in writing comments they have made under cross-examination, without fear that they will be further cross-examined on that written explanation. It was inappropriate for Dr Branney to seek to do so. I should add that, even if I had taken his sixth witness statement into consideration, it would not have made a difference to the conclusions I have reached above.

- Counsel for the Defendants submitted that even if I were to find that Dr Branney was a dishonest witness, it does not matter, because the Defendants relied on little of his evidence. I do not accept that the Defendants have relied on little of Dr Branney’s evidence, and where they have, I have disregarded it as I have set out below.

- Because of the seriousness of the issues surrounding the pleadings and Dr Branney’s affidavit and witness statements, at the close of the evidence I invited the Defendants’ legal advisors to submit a witness statement to “explain what happened in a full and frank way”. A twelfth witness statement of Mr James Seadon of the Defendants’ solicitors was filed and served prior to closing speeches, but the witness statement only dealt with the under-reported numbers issue, not the cessation of sales issue. Counsel for the Defendants made submissions about the conduct of the Defendants’ advisors in his closing speech, but, during the Claimants’ counsel’s closing speech later in the day, counsel for the Defendants interrupted to say that he may have misspoken earlier in the day, and that nothing in his closing speech was intended to add to the evidence which had been provided in Mr Seadon’s twelfth witness statement. With my permission, Mr Seadon then filed a thirteenth witness statement to deal with the cessation of sales issue. That witness statement arrived on time and after the inquiry had concluded.

- In relation to Dr Branney’s Island Records affidavit, Mr Seadon gave evidence that Dr Branney's fifth witness statement was intended to be the correction to the sales figures given earlier.

- In relation to the recommencement of sales issue, Mr Seadon wrote:

- Further, Mr Seadon wrote:

- I accept Mr Seadon’s explanation, although it strains credulity that any legal professional (solicitor or barrister) can have considered that the steps that were taken to correct Dr Branney’s false Island Records affidavit were sufficient in this case. This has been hard-fought litigation, where very few stones have been left unturned. I am told that in the period between the discovery of the additional sales (26 September 2021) and the start of the inquiry (25 October 2021), almost exactly one month, Mr Seadon’s firm sent 50 letters to the Claimants’ solicitors. I have not counted them myself, but in the context of this litigation, that seems plausible. In any of those, the undercounted garments issue could have been raised - and, in my judgment, should have been raised in terms. The steps taken were wholly inadequate for the reasons I have set out above, and which Mr Seadon now acknowledges.

- Mr Seadon’s explanation does not excuse Dr Branney, who had an obligation to tell the truth, regardless of the (in my judgment, incorrect) advice he was given. Dr Branney ought to have spoken up earlier, and at the very latest when he was questioned under his affirmation.

- The Claimants relied on one expert witness, Mr Matthew Geale, a partner at Armstrong Watson LLP. Mr Geale is a forensic accountant with many years of experience. He has previously given expert evidence before this court in other matters and also in other tribunals. His report ran to 103 pages. Mr Geale reviewed the evidence as he understood it, and provided his opinions as to losses and royalties. He also provided his views on the hypothetical negotiation of a reasonable royalty. He was cross-examined.

- Counsel for the Defendants described Mr Geale as having given “exemplary expert evidence” except in one respect - he criticised Mr Geale’s evidence on licences with royalty rates based on a percentage of the licensor’s selling price, for which he did not provide any examples. I accept that criticism. I make some further comments below on the expert evidence in this case more generally.

- The Defendants’ relied on the expert evidence of Mr David Dearman, a Senior Managing Director at Ankura Consulting (Europe) Limited. Mr Dearman is also an experienced forensic accountant. He provided two reports, the first of which ran to 397 pages, and the second of which totalled 21 pages. He gave evidence about the Claimants’ claim for damages based on lost profits, and gave his views on a reasonable royalty. In his second witness statement, he responded to Mr Geale’s evidence on the likely reasonable royalty and the differences in price between the parties’ respective garments. He was cross-examined.

- The Claimants did not criticise Mr Dearman’s honesty (in my view, quite rightly), but did submit that he did not perform properly the role of independent assistant to the court. In particular, the Claimants’ counsel submitted that he had “clearly gone out of his way to develop support for the Defendants’ case”, including by adopting Dr Branney’s evidence without question (despite having described it as “extreme”) whilst ignoring the Claimants’ position, presenting conclusions on the parties’ sales data that simply could not be supported, and suggesting “obviously un-comparable licences” were comparables for the purposes of determining a reasonable royalty.

- I have no doubt at all that Mr Dearman was presenting his evidence honestly. However, he based his opinions heavily on Dr Branney’s evidence, which I have held cannot be relied on unless independently verified. He accepted under cross-examination that he had based his evidence on Dr Branney’s evidence, and had not relied on Ms Richards’ evidence. He also, in my judgment, had a tendency to argue the Defendants’ case, giving answers under cross-examination that set out that case, rather than responding to the questions put to him.

- He was also asked to examine matters beyond his expertise, and issues that were ultimate questions for me. For example, at paragraph 7.1.2 of his first expert report, Mr Dearman said:

- With respect to Mr Dearman, that was simply not within his expertise as a forensic accountant, and was, in any event, the ultimate question for me on which he should not have been asked to opine.

- For these reasons, I have treated his evidence with some care.

- I reiterate Jacob LJ’s comments in Rockwater Ltd v Technip France SA and Anor [2004] EWCA Civ 381 at paragraph 12. That was a patent case, but his comments about the role of expert evidence are apposite in this case:

- It is not the role of expert evidence in damages inquiries to proffer answers to the questions that are those for the court. For example, and as both counsel agreed, it is for the court to assess the hypothetical negotiation between two willing parties in order to try to reach a reasonable royalty. Here, experts can set out what they have observed in other licences, but they are of limited if any help to the court in suggesting what these particular parties might have agreed. They can model various outcomes - but if those models are based on contested facts which the court does not find to be accurate, then their models are of limited use. Similarly, expert forensic accountants can provide only limited (if any) evidence on whether an infringing garment purchased from the Defendants was a sale lost by the Claimants. Therefore, in my judgment, whilst both experts tried to do their best with the instructions they were given, and answered honestly the questions put to them, both were asked to go beyond their proper tasks and to stray into matters that are for the court to decide. Their written evidence was exceedingly long for a case of this type, and ought to have been significantly shorter, dealing only with matters within their competence.

- For ease, I set out below factual findings from the Main Judgment which are relevant to the issues in the inquiry:

- I turn first to standard damages.

- The parties agreed on the law to be applied in the assessment of standard damages. Kitchin J (as he then was) set out the principles in Ultraframe (UK) Limited v Eurocell Building Plastics Limited and Anor [2006] EWHC 1344 (Pat) at [47] (whilst that case involved patent infringement, the parties agreed that the judgment applies equally here):

- HHJ Hacon added to those principles in SDL Hair Limited v Next Row Limited [2014] EWHC 2084 (IPEC) at [31]:

- In relation to lost profit damages, the parties were in agreement that I should, on the basis of Allied Maples, apply a two-stage approach:

- Counsel for the Claimants submitted that for the purposes of the second stage, it does not matter whether at the previous stage the court was, for example, 51% sure or 100% sure that some loss had been sustained under the head claimed: the court is simply concerned with finding a figure to compensate for the head of loss which it has already found to have been sustained. Counsel for the Defendants did not object to that approach, and I accept it. I was further referred to the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Parabola Investments Limited and Anor v Browallia Cal Limited [2010] EWCA Civ 486 at [23]:

- Counsel for the Claimants submitted that the second stage of this exercise may be artificial and difficult, because the court is called upon to make findings about what would have happened in a hypothetical world in which the defendants had not infringed. That does not mean, she said, that the court can throw up its hands and declare the exercise too difficult. Rather, she said, the court’s task is to do the best job it can with the material the parties have put before it. I accept that submission. She referred me to the speech of Lord Wilberforce in General Tire and Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Company [1975] WLR 819 at page 826:

- Counsel for the Claimants also referred me to the judgment of Jacob J (as he then was) in Gerber Garment Technology Inc v Lectra Systems ltd and Anor [1995] RPC 383:

- HHJ Hacon dealt with the applicable principles for loss of royalties in Henderson v All Around the World Recordings Limited [2014] EWHC 3087 (IPEC) at paragraph 18 (again, the parties agreed that these principles, albeit set out in the context of performers’ rights, are also applicable to the unregistered design rights in this case):

- As mentioned above, I was also referred to the judgment of Jacob J in Gerber v Lectra from which the principles in Ultraframe were derived. Again, Gerber was a damages inquiry for patent infringement, but the parties agreed it is applicable here. The judge held at paragraphs 413 to 420:

- I was also referred to McGregor on Damages (21st Edition) at paragraph 14-046:

- Further guidance on the hypothetical negotiation is to be found in the speech of Lord Wilberforce in General Tire at page 833:

- As Warren J noted in Field Common Limited v Elmbridge BC [2008] EWHC 2079 (Ch) at [78] (emphasis in original):

- Counsel for the Claimants submitted that as I consider the hypothetical negotiation in this case, both sides’ needs, means, and concerns must be taken into account. If, for example, the licensor will itself suffer as a result of granting a licence, this, she said, will be material, citing Mr Anthony Mann QC (sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge) (as he then was) in AMEC Developments Limited v Jury’s Hotel Management (UK) Ltd [2001] 82 P & CR 22 at [12]:

- Further, she submitted that the hypothetical negotiation is a prospective one: it takes place before any acts which would otherwise constitute infringement are committed. Save for the actual number of sales made by a defendant, events which, in fact, took place after the hypothetical negotiation would have happened are strictly irrelevant - and so the infringer’s actual profit is not a factor which the parties would have taken (or been able to take) into account. After all, the exercise is not an ex post facto account of profits which have already accrued to a defendant - necessarily, by the time a damages inquiry takes place the claimant has elected not (or is not entitled) to pursue that kind of relief. She referred me to the judgment of Neuberger LJ (as he then was) in Lunn Poly Limited and Anor v Liverpool & Lancashire Properties Limited and Anor [2006] EWCA Civ 430, commenting on the judgment of Mr Mann QC I have referred to immediately above:

- In Pell Frischmann Engineering Limited v Bow Valley Iran Limited and Ors [2009] UKPC 45, the Privy Council approved Neuberger LJ’s analysis in Lunn Poly and noted:

- Citing both Lunn Poly and Pell McGregor on Damages concludes at paragraph 14 - 55:

- In reaching my conclusions on standard damages, I have kept all of the above front of mind. I have particularly kept in mind that damages are to be assessed liberally, with the object to compensate the claimant and not to punish the defendant. As to lost sales, the court should form a general view as to what proportion of the defendant’s sales the claimant would have made. Where damages are difficult to assess with precision, the court should make the best estimate it can, having regard to all the circumstances of the case and dealing with the matter broadly, with common sense and fairness. Not much in the way of accuracy is to be expected bearing in mind all the uncertainties of quantification.

- The Claimants’ case on lost profit damages was as follows:

- The Defendants agreed with this approach, but disputed the value of P. It was also agreed between the parties that it is not possible to state the value of P definitively without interviewing the customers for the 15,393 infringing garments, or at least undertaking a statistically significant survey of them, which would have been disproportionate.

- The Claimants’ pleadings valued P at 1 (that is, every infringing sale made by the Defendants was a sale lost by the Claimants). By their closing submissions, the Claimants submitted that P = 0.25 (that is, for every hundred infringing sales made by the Defendants, 25 were sales lost by the Claimants). Put another way, absent the Defendants’ infringement, the Claimants would have made 25% of the sales that the Defendants did in fact make of the infringing garments. The Defendants maintained throughout that P = 0, that is, that none of the 15,393 infringing sales was a sale lost by the Claimants.

- As set out above, I must follow a two stage approach, first determining if any of the Defendants’ infringing sales was a sale lost to the Claimants. If I find that even a single sale was lost, I must then move on to the second stage. However, if I find that no infringing sales were lost, then P = 0, and no lost profits damages will be awarded.

- The parties agreed that there was no direct evidence from consumers on the value of P - no-one was brought forward to say “I bought the Defendants’ infringing garment instead of the Claimants’ garment from which the Defendants’ garment was copied”. This was unsurprising. It was also not a topic on which the experts could give meaningful evidence (consumer behaviour being outside their field of expertise). The Claimants relied on findings from the Main Judgment to support their position that P > 0, namely:

- There is no doubt in my mind that at least some of the infringing sales were sales lost by the Claimants. It is therefore clear to me that P > 0. As the parties each relied on the same evidence and submissions in relation to both stages of the relevant test, I will discuss the submissions of both sides in the context of establishing the value of P.

- I was not assisted in the task of determining P by the diametric positions initially taken by the parties, with the Claimants suggesting that P was the maximum it could be (1), and the Defendants insisting that P was the minimum it could be (0). By their closing submissions, the Claimants had shifted, suggesting that P = 0.25. The Defendants continued to maintain that P = 0.

- Whilst there were 18 infringing garments, I have not assessed a different value for P for each garment. Counsel for the Claimants did not urge me to do so. Counsel for the Defendants submitted that P = 0 for each garment, and urged me to look at each design/garment pair individually to assess lost sales. Whilst not calculating a different value for P for each design/garment pair, I do accept counsel for the Defendants’ submission, and I have done that. I have also, as requested, reviewed carefully the helpful table provided by the Defendants and Mr Dearman’s Appendix C which compares the sales data as between the Claimants’ and the Defendants’ garments. It would, in my judgment, be inconsistent with the authorities I have cited above and grossly disproportionate to come up with 18 different values for P. I have therefore given P a single value, but I have taken into account the review I was asked by the Defendants to undertake, as well as the other submissions made on their behalf.

- The following facts were common ground:

- Further, the Claimants have conceded that there would have been no substitute sales as between C108* (a swimsuit) and D41 (a jumpsuit).

- I turn now to the Defendants’ submissions that P = 0:

- I have dealt above with the Defendants’ submissions, some of which I have not accepted, and some of which I have taken into account. I agree with the Claimants that P is clearly less than 1. I also consider that P is less than 0.25, but not significantly less than 0.25. I am mindful of the need to be “liberal” in my assessment of P (Ultraframe), forming a “general view” (Ultraframe), and that “one cannot expect much in the way of accuracy” (Gerber). I must engage in a “process … of judicial estimation of the available indications” (General Tire), involving “the exercise of a sound imagination and the practice of the broad axe” (Watson, Laidlaw & Co Limited v Pott, Cassels and Williamson (1914) 31 RPC 104). This cannot be a scientific exercise, but I must do the best I can.

- Keeping all that in mind, in the exercise of my judicial estimation, taking into account the matters I have referred to above, and my findings from the liability trial, I have reached the conclusion that P = 0.2.

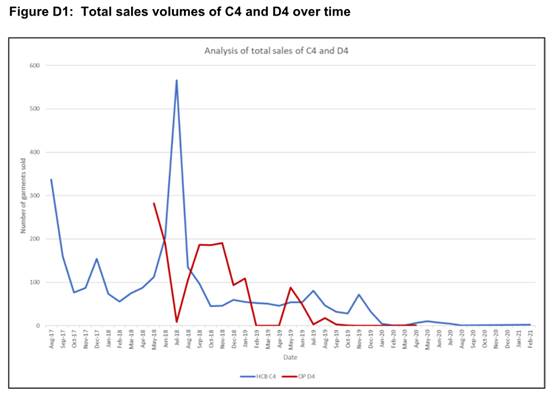

- In their closing skeleton, the Claimants provided the following table to show their calculation of P at 0.25. C108*/D41 do not appear in the table. A deduction has been applied to reflect the Sirens licence and the Linhope licence (both of which were raised by the Defendants as needing to be accommodated, and which the Claimants sensibly did). The Claimants only claim lost profits in respect of those of the Defendants’ infringing garments sold in the UK (which infringed UKUDR) and those in the EU in colourways which infringed CUDR.

- A further adjustment to this table is required. Both Mr Waters and Mr Geale accepted that the appropriate sales price to use for the Claimants’ garments is the weighted average sales price across the Claimants’ sales from the first infringing sale, rather than from the first of the Claimants’ sales.

- Taking a value of P at 0.2 rather than 0.25, and adjusting for the matter set out in the previous paragraph, I award the Claimants £74,847.92 in lost profits.

- I add for completeness that the Defendants criticised the Claimants’ profitability figures on a number of additional bases. The Defendants criticised the omission of the Sirens licence and the Linhope licence, which the Claimants addressed prior to their counsel’s closing speech, and the timing of the weighted average to which I have referred above. I do not accept the Defendants’ further criticisms, including that the Claimants had not disclosed all the base documents from which their figures were calculated and that therefore the Claimants’ manufacturing costs could be called into question. I rejected the Defendants’ application for disclosure of those documents by order of 10 September 2021, and no suggestion was made that the sample invoices which were disclosed were not representative. The Claimants were aware of their continuing obligation to disclose known adverse documents. I also reject the Defendants’ submissions that some of the lost sales would have been in-store sales, and that the profit lost on those sales was of the Third Claimant (no longer taking part in proceedings), rather than the First or Second Claimant. It seems to me that I must compare like with like, and where both sides operate lucrative online businesses, with overlapping customers, that is where the lost sales are likely to fall. I had no evidence to the contrary.

- It is common ground between the parties that at least some damages should be awarded on the basis of a reasonable royalty. The Claimants put the figure at £170,000 at the highest (or £11 per garment). They offered me a variety of hypothetical agreements which they submitted the parties could have reached:

- The Defendants put the figure at around £15,000, or £1 per garment. They submitted a number of hypothetical agreements which the parties could have reached:

- It should be remembered that damages on the basis of a reasonable royalty can apply only to any sales which have not been compensated for as lost sales. Given my findings above, this includes (a) all sales outside the UK/EU; (b) all sales of garments to customers in the EU (excluding the UK) where the garment did not infringe UCDR; (c) all sales of D41; and (d) 80% of sales to customers in the UK and EU (in the latter case where the relevant garment did infringe UCDR).

- I have set out above the law on assessment of a reasonable royalty. The parties were largely in agreement on the law, but took very different approaches to its application in this case. The difficulty of the situation is well-known, as the various judgments excerpted above attest. Here, the assessment was complicated further, because:

- Put briefly, Ms Richards and Dr Branney, on their own evidence, would not have got close to an agreement. My task, as the parties urged me, and the authorities require me, is to bridge that gap and declare what agreement the parties would hypothetically have reached - in effect forcing one or both sides to breach their declared negotiating positions. Each side advocated that the other side’s red lines were not real or not relevant, but that their own were.

- To complicate things further, I was offered a very broad smörgåsbord of approaches from which to choose, some of which seemed to me to be far-fetched, and some of which were closer to commercial reality. Much of the “evidence” with which I was presented was really submissions.

- The parties agreed that there would have been only one hypothetical negotiation: I was not asked to assess a different royalty rate for each garment. I was also asked to do that as at the date of the first infringement - that is 11 August 2016. Given that the Defendants were still launching infringing garments in 2018 and still selling them in 2020, that date does seem to me rather artificial, but it does have the benefit of simplicity.

- The Defendants raised in closing a pleading point that it was not open to the Claimants to claim a fixed fee per design. Dr Branney gave evidence of the fixed fees he would have been willing to pay for a partial design (up to £1,000) and a whole design (up to £3,000). I do not consider that the Claimants are precluded from that position only because it is not set out in those terms in their pleaded case - it does fall within the broader statement of the relief they have sought.

- I set out below some data points that, if not agreed, are at least broadly agreed:

- There was a debate before me as to whether or not I should take into account in the assessment of a reasonable royalty the (agreed) fact that the House of CB and Oh Polly businesses competed. Put shortly, the Defendants’ position was that this was already accommodated in the lost profits analysis which I have set out above. My finding that 80% of the Defendants’ infringing sales would not have been sales lost by the Claimants deals with the issue, and so, the Defendants’ submitted, the competition between the businesses is irrelevant to this head of damage. On the other hand, the Claimants submitted that whilst the parties entered the hypothetical negotiation knowing no sales of the Claimants’ garments were at risk, the negotiation does not occur within a vacuum, but in the actual circumstances as they existed. Therefore, the Claimants submitted that the position of the parties as competitors is of “great relevance even if the fact that the licensed garment[s] will compete must be ignored.”

- The Claimants put their argument as follows: no sensible businessperson does anything which will assist a competitor’s business unless there is a very good reason to do so. Helping a competitor today helps it weather future financial challenges, giving the competitor more profit to invest in expanding its business, making it better able to fulfil the requirements of the market. Here, House of CB and Oh Polly were (it is agreed) competing in the same market for the same consumers. There was evidence before me in the liability trial of customers buying from both House of CB and Oh Polly. Each, I found, sells a “lifestyle” or “brand”, and I found those “lifestyles” and “brands” to be very similar. The Claimants therefore submitted that House of CB, a major clothing brand with annual turnover of millions of pounds, would simply not license designs to a direct competitor for small sums of money. Similarly, the Claimants submitted, the Defendants would not have expected to get away with paying a small sum for trending designs already being marketed by a premium brand.

- Counsel for the Defendants described this as a “simple but fundamental error of law”, because reasonable royalty damages are only available in respect of sales of garments which did not result in any lost sales - lost sales damages are already covered by the lost profit calculations I have set out above. He submitted that “as a matter of logic”, it is not legitimate to assume that the parties would be competing. He cited as support for this conclusion paragraph 47(v)(c) of Ultraframe, which I have set out above, and the judgment of Jacob J in Gerber v Lectra, which I have also set out above. Importantly, the judge said in relation to the 13 sales in issue before him:

- However, the judge’s statement does not seem to me to go as far as counsel for the Defendants suggested. The Claimants accept that their lost profits are irrelevant to this part of the assessment. Their argument, though, is a different one. As Newey J set out in 32Red (also set out above):

- Counsel for the Defendants also relied on Jacob J’s further comments in Gerber when talking about how the “available profits” of the Defendants should be split:

- It is important to note that the judge here was talking about division of “available profits” - this was one of the many possibilities put to me. I accept the Defendants’ submission that I ought not take into account competing sales if I decide that the parties would have agreed to split the Defendants’ profits. However, I do not understand either of the judge’s comments relied on by the Defendants as applying generally to the assessment of a reasonable royalty.

- In summary, I accept (as do the Claimants) that I ought not take into consideration the sales lost to the Defendants. However, in my judgment, I am able to take into account the positions of the actual parties, and that position includes the (agreed) fact that they were, at the relevant time, very keen competitors. However, whilst taking it into account, it has not made a meaningful difference to my assessment.

- As counsel for the Claimants put it in her closing skeleton argument:

- As set out at paragraph 19(ix) of 32Red, the parties to the hypothetical negotiation would have taken into account the availability or otherwise of a non-infringing course of action. The Claimants submitted that as at 11 August 2016, the Defendants had no alternative:

- It should also be remembered that none of these approaches would have guaranteed availability to the Defendants of designs from a leading, on trend business. In copying designs which the Claimants had already launched, the Defendants were getting their pick of finished designs which had already been launched by a successful business. That was something that none of the possible lawful alternatives set out above would have provided.

- As set out above, Ms Richards gave evidence on behalf of the Claimants, and Dr Branney gave evidence on behalf of the Defendants. Mr Geale gave evidence that both Ms Richards and Dr Branney were adopting positions most favourable to themselves, and Mr Dearman accepted in cross-examination that the positions each adopted were “certainly extreme”. Further, Ms Richards was not criticised for how she gave her evidence, but she was clear that she would not have been the person in the House of CB business who would have conducted the negotiation, so there is a limit as to what her evidence can tell me. I have concluded above that Dr Branney was not an honest witness. Finally, as I have set out above, and as Dr Branney accepted in cross-examination, in order to come to a hypothetical agreement, I must breach the red lines of one or both sides. Therefore, I have come to the conclusion that the fact evidence on both sides is of limited assistance to me. It provides some information on the parties’ starting positions, but it does not assist me materially in determining where the parties would have ended up.

- For completeness I need to deal briefly with an issue on cross-examination that was argued before me. Counsel for the Defendants submitted in his closing skeleton that the court was precluded from setting a royalty on the basis of the Defendants’ increasing their prices to £55 per garment because that scenario was not put to Dr Branney in cross-examination. I do not accept that submission. The hypothetical negotiation is exactly that - it is a likely outcome that the court must determine on the basis of the facts before it. As I have said, it involves breaching the red lines of one or both sides. Dr Branney accepted that his may have to be breached. It is not the case that counsel must put to the fact witnesses for each side in an inquiry all the various possible permutations of a hypothetical negotiation to gauge their reaction. I have to bring the two sides together and reach a hypothetical agreement, even if both sides say they would never have reached that agreement.

- Mr Dearman adduced evidence of what he described as “comparable licences” to support his conclusions on where the parties would land at the end of a hypothetical negotiation. Counsel for the Claimants criticised this reliance on the following grounds:

- I add to these criticisms, all of which I accept, that many of the licences related to territories other than the UK/EU, and several of the licences were not recent (including one from 1996, pre-dating on-line commerce).

- There is a difference between this case and that of a licensing business such as Ralph Lauren agreeing terms for use of its trade marks on sheets and towels. Mr Dearman’s analysis is therefore of limited assistance to me, so I must treat his conclusions with some circumspection. What the licences do is provide a general sense of the commercial reality, and a sense of the lower and upper ranges of agreed percentages (Mr Geale agreed that the normal range for trade mark licences was 3-6%). These licences also demonstrate the importance in the commercial world of minimum royalty payments and they highlight that net sales is the usual basis for calculating royalties.

- The Defendants denied that a reasonable royalty is owed on garments they sold outside the UK/EU. Put briefly, their argument, based on Dr Branney’s evidence, was that, rather than pay a reasonable royalty on these garments because they were shipped through the Defendants’ distribution centre in the UK, the Defendants would instead have changed their distribution model by making arrangements to ship the relevant garments from its factories in China or Bangladesh directly to the customer. Dr Branney accepted that there was some administrative burden to doing so. There was no other evidence to support Dr Branney’s assertion, and I reject it as fanciful. It would make no economic sense to set up different arrangements for what turned out to be 3,842 garments sold outside the UK/EU in order to avoid paying a reasonable royalty on them, especially if that royalty was less than $10 per garment (the additional cost Dr Branney estimated for the new arrangement). But even if the reasonable royalty were greater than $10 per garment, I do not consider that the Defendants would have decided to change their arrangements. There would have been additional administrative costs; the Defendants would lose control over the presentation of the shipped goods, something I was told during the liability trial was important to consumers; such an arrangement would complicate returns (about 30% of purchases are returned); and a customer ordering two garments might receive them separately without understanding why. I reject Dr Branney’s evidence on this point. The Defendants were at pains to point out that the 15,393 garments were a tiny part of their business - less than 0.5%. It is to me inconceivable that the Defendants would have gone to the additional trouble and expense of re-arranging their distribution network so as not to pay a reasonable royalty on 3,842 garments, or less than 0.1% of their business.

- I also reject the Defendants’ reliance on the Claimants’ operation of what was described as a similar model in respect of sales outside the UK/EU, because it is not true. As the Defendants acknowledged, the Claimants operated a fulfilment centre in China, with all the attendant costs - they did not have garments shipped to customers directly from the factories.

- The Defendants submitted that the parties to the hypothetical negotiation would have distinguished between the full garment designs and the partial garment designs which they infringed. It was submitted that this was the only approach available to me as a matter of law and as a matter of fact. I reject both submissions. As a matter of law, I accept that the licence relates to the rights infringed. Therefore, in the hypothetical negotiation, the parties may or may not distinguish between partial designs and whole designs. But that is a question for the facts of this case. On the facts of this case, I have set out above Dr Branney’s evidence on trends. He gives examples of “trends” - a square neckline with straps; or a y-neck with a harness; or a ruched asymmetric hemmed skirt. He says “generally it is rarely a specific dress”. A “y-neck with a harness” is a part of a design - it could as readily be applied to a jumpsuit, a dress, a top or a swimsuit. So I also reject the Defendants’ submissions on the basis of their own evidence.

- I have set out above the partial designs labelled C27*, C61* and C110*. The others were C1*, C57*, C108* and C109* which I set out below. Again, it is obvious that what matters about the infringing garment is the copied design - in each case, the Defendants’ infringing garment copies the whole part, and the remainder of the garment is standard or usual, with limited or no design input.

- Doing the best I can with the volume of evidence before me, much of which, as I have explained, is of limited or no assistance, it seems to me that the following evidence is relevant to the issues I have to determine and, being consistent with commercial reality, is more likely to be accurate:

- Taking this into account, the Defendants’ expert’s proposals can readily be rejected. As set out above, the Claimants would not have been keen to agree a calculation based on the Defendants’ net profits (over which they had no control and which could be time consuming and complicated to calculate). Had the Claimants been prepared to agree a calculation based on net sales or gross profits, then, in my judgment, they would not have agreed the percentages suggested by Mr Dearman - it would simply not have been worth their while to go through the whole exercise for £15,000, given the large size of their business. In my judgment, the Claimants would simply have walked away from that low offer, however it was calculated, as just not worth the effort of licensing the designs, and monitoring the Defendants’ sales or profits. I reject the Defendants’ three submitted positions as divorced from reality.

- These three positions are also more beneficial to the Defendants than Dr Branney’s evidence. Dr Branney’s opening position (which Mr Dearman acknowledged to be extreme) and from which Dr Branney accepted he would need to compromise was:

- I also reject the Claimants’ primary position of calculating a reasonable royalty on the basis of the Claimants’ normal sales price. Whilst this would have given the Claimants certainty, it was not something the Defendants could hope to make any money out of, given their generally lower sales price for garments, and/or their lower cost of manufacture, which, I have accepted, they could not lower further. I also reject the Claimants’ proposal based on anticipated gross profit as being most unusual in the market. I reject, too, their proposals based on absorbing the Defendants’ additional profits from a forced price-rise - this was an option that appeared nowhere in the evidence.

- In my judgment, the hypothetical deal reached by the parties would have been as follows:

- As will be apparent, the above hypothetical licence does not rely on the Defendants’ profitability, although I do consider that the Defendants would have been alive to profitability in their calculations as to what they could afford. This means that I do not need to deal with the various submissions made by the parties on dividing the Defendants’ actual profit between them because, in my judgment, that is not what the parties would have agreed.

- Therefore, I assess the reasonable royalty at £75,276.64.

- I turn now to additional damages. The Defendants concede that the Claimants are entitled to additional damages as a result of the flagrancy of the Defendants’ infringement. However, the Defendants suggest that an uplift of 20% of the standard damages award would be appropriate - on this submission, a figure of approximately £3,000, or 20p per garment. The Defendants submitted that this would be (a) proportionate to the scale of the infringement; (b) punitive; and (c) serve as a deterrent to the Defendants and to other potential infringers. On the other hand, the Claimants seek a figure that, in short, “tops up” the standard damages awarded so that the Claimants receive (a) the total they would have received if they, rather than the Defendants, had made all the infringing sales (in excess of £500,000) or (b) the total revenues received by the Defendants for the infringing sales (£451,188). Once again, the parties were far apart.

- Again, the parties were agreed as to the law I should apply. The court is empowered to award “such additional damages as the justice of the case may require” “having regard to all the circumstances”: section 229(2) of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (the CDPA).

- The leading case on the award of additional damages is Phonographic Performance Limited v Ellis (trading as Bla Bla Bar) [2018] EWCA Civ 2812. Whilst that case involved copyright infringement, the wording of sections 97(2) and 229(3) of the CPDA is the same. Lewison LJ (with whom King and David Richards LJJ agreed) set out the relevant principles as follows:

- The requirement that an award of additional damages be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” is taken from Directive 2004/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the enforcement of intellectual property (the Enforcement Directive) transposed into domestic law by the Intellectual Property (Enforcement etc) Regulations 2006.

- There was also some discussion before me as to what is meant by an abuse of rights. Lewison LJ raised the point in Bla Bla Bar as follows:

- No further explanation was given as to what was meant by an abuse of rights, and, whilst counsel for the Defendants repeated the warning often, he did not point me to any further authority as to what it means. For my part, I do not consider that I need to reach a view on that point, other than to ensure that in reaching my conclusion on an appropriately “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” award, I do not stray so far that the award becomes egregious.

- Other than these general principles, the parties were unable to point me to useful guidance in the authorities on how to determine the quantum of additional damages. I was, however, given as examples a number of cases in which additional damages were awarded, although none were in relation to facts identical to those in this case. The Defendants provided a table of cases which they said provided some guidance, and which I include here. However, as none of those cases involved facts close to those in this case, these examples can only be that.

- What these cases demonstrate is that some judges have calculated additional damages on the basis of a “percentage uplift” on the standard damages awarded, but they do not establish that as a rule. Indeed, there would not appear to be a conventional approach to the assessment of additional damages. Nugee J (as he then was) demonstrated one method in the last of the cases in the table above, Reformation Publishing. This was a copyright case in the IPEC. The hearing did not last more than a day. In his written judgment, having awarded £38,750 in standard damages, the judge said this (at paragraphs 92 and 93):

- Counsel for the Claimants urged on me the following conclusions from some of the cases above:

- The Claimants submitted that the level of additional damages should reflect the per-unit profit which the Claimants were making while selling the infringing garments. Counsel for the Claimants conceded that this approach was “novel”, but submitted that it was not incompatible with any existing authority on additional damages. She submitted that such an award would send a clear message to would-be copyists that the consequences of copying a successful and profitable competitor’s work can be serious - and the more successful and profitable the competitor, the greater the risk to the copyist. Alternatively, the Claimants suggested I award additional damages in the sum of the net revenue generated for the Defendants by the infringing garments.

- The Claimants asked me to take into account the following factors:

- The Defendants accepted that an award of additional damages in this case is appropriate, and that such an award may be partly punitive - it should serve to produce a deterrent effect both on the Defendants and other would-be infringers of design rights. The Defendants submitted that I would achieve this aim by applying an uplift of 20% on the award of standard damages. Their submission was that standard damages should be approximately £15,000, so the uplift of 20% would be £3,000 (or 20p per garment). I have found that the standard damages award should be £150,124.56. 20% of that figure would therefore be £30,024.91 (or £1.95 per garment). I can readily dismiss these submissions. These amounts are trifling in the context of the Oh Polly business, which turned over £39 million in the 2020 financial year. In my judgment, such a small award of additional damages, even when coupled with the standard damages I have awarded, would go no way to punishing these Defendants, nor deterring them, or other copyists, from infringing in the future. The Defendants’ suggested award would not be effective, proportionate or dissuasive, and I reject it.

- Counsel for the Defendants submitted a number of factors which I should not take into account in reaching an award:

- Given that I was addressed by counsel for the Defendants on each of these issues, for the avoidance of doubt, I record that I have not taken into account the following matters in reaching my conclusions on additional damages, without reaching any view in law as to whether in other cases these factors might be taken into account:

- In my judgment, taking into account all the relevant circumstances of the case, an award of £300,000 in additional damages would be appropriate. In reaching this amount, I have taken into account only the acts of infringement, being the 15,393 infringing garments sold by the Defendants: this was serious infringement on a large scale. It was also flagrant infringement, carried out over four years. I have taken into account the Defendants’ approach to their infringement, including continuing to deny copying (other than in relation to C35) through the liability trial. I have taken into account the need to punish the Defendants in a way that is effective, proportionate and dissuasive. Given the profit made from these infringing garments, and the size of the Defendants’ business, in my judgment, only an award of this size will be sufficient to punish them for what they have done, and to deter them from infringing again. No lesser amount would achieve that. This is what the justice of the case requires. I have considered carefully whether that award is proportionate, and in my judgment it is. I also do not consider it to be egregious or an abuse of rights.

- Whilst I have not taken any of the following into account in reaching the award, I am encouraged by the following:

- There was a dispute over whether the interest rate should be 1% over base rate or 1.5% over base rate, on which I was not addressed orally. If the issue remains in dispute, it can be determined in due course.

- In my judgment:

- The total payable is therefore £450,124.56, which is to be paid within 21 days.

(a) their lost profits on garments which, but for the Defendants’ sales, would have been made by the Claimants;

(b) a reasonable royalty on the Defendants’ sales not covered by (a) above; and

(c) additional damages pursuant to my earlier finding that the Defendants’ infringement was flagrant.

Background

Fact Witnesses

Joanna Richards

“We refer to your second letter dated 12 October 2021, wherein you state that “the issue of which factory makes which garments is utterly irrelevant to any issue still in dispute in these proceedings”.

For the avoidance of doubt our clients reject this proposition. We hereby put you on notice that at trial we will be asking Mr Waters and/or Ms Richards where each of the garments were manufactured and about the relationship between the factory (or factories) and the Claimants. It appears from their evidence that they already know of such matters, but if they do not, we ask that they have that information available to them at trial.”

David Waters

Michael Branney

Cessation of Sales

“However, the latest Infringing Garment in time was first offered for sale on 25 June 2018, which is only 10 days after the claim form and particulars of claim were sent to the registered address of the First to Third Defendants. By the time of the service of the original Defence in January 2019, the Defendants had stopped selling 66 of the 87 garments then complained about.”

(a) the Amended Defence was wrong (because sales had in fact recommenced); and

(b) his Island Records affidavit and third and fourth witness statements were wrong (because they did not include all the Defendants’ sales of infringing garments).

“8. I have previously provided evidence on the number of units sold, the gross profits per item and estimated net profits per item for the designs referred to in these proceedings as D2, D4, D12, D13, D35, D61, D85, D87 and D91 in my affidavit of 2 May 2021 [his Island Records affidavit]. I have also provided evidence on the number of units sold and the gross profits per item for the designs referred to in these proceedings as garments D1, D6, D15, D27, D41, D48, D54 and D57 in my third and fourth witness statements, dated 22 July 2021 and 18 August 2021 respectively. The methodologies used at the time to calculate these figures can also be found in the respective affidavit and witness statements.

9. The Defendants were directed by the Order of the Deputy Judge dated 30 July 2021 to use our best endeavours in the time available to ensure that the figures provided for gross profits (with respect to garments D1, D6, D15, D27, D41, D48, D54 and D57) were as accurate as possible. I complied with the 30 July 2021 Order to produce figures to the best accuracy possible in the time provided. However, I am now in a position to state various financial figures with greater certainty.”

“The Program has allowed me to record (in the Spreadsheet) the number of units sold, gross profit per item and net profit per item for each of the Infringing Garments with greater confidence than previously possible.”

“As soon as [Dr] Branney realised the [Island Records] affidavit contained incorrect figures, he corrected them by serving his 5th statement which referred to the accurate numbers in the spreadsheet provided under cover of CEA Notice.”

“However, I consider Dr Branney’s failing here to be maladroit, rather than malevolent. He had not designed the garments in issue - Ms Henderson had. He was working from documents and from Ms Henderson’s explanations. He ought to have been more careful before signing the statement of truth, but I do not consider that this means I should discount his evidence completely. Counsel for the Claimants described Dr Branney’s evidence as that “of a person willing to say whatever needed to be said to achieve his objective.” Having watched him give evidence, I consider that Dr Branney was an active advocate for the Defendants. I have therefore approached his evidence with caution, but I reject counsel for the Claimants’ submission that I should dismiss it altogether.”

“Further, by the time of the service of the original Defence in January 2019, [the Defendants] had stopped selling 66 of the 87 garments then complained about. That is not the behaviour of a cynical infringer with no regard for the law that should be punished out of all proportion to the scale of the infringements.”

“Q: It is right, is it not, Dr Branney, that in the course of this litigation, the Defendants have stated that they have stopped selling some of the garments even though they did not accept that those garments were infringing the Claimants’ rights; correct?

A: That is correct, my Lord.

…

Q: …this is paragraph 19G we have just been looking at. What you are saying here is that it is not entirely fair for the Claimants to say that the Defendants did not cease copying their designs until after these proceedings were launched because in fact, you say, the last infringing garment in time was only launched shortly after the claim was issued; correct?

A: That is correct.

Q: That by the time the original Defence was served you had in fact stopped selling 66 of the 87 infringing garments then in issue; correct?

A: My Lord, that is correct.”

“I have had the opportunity to review the transcripts from my cross-examination (which were provided to me by Fieldfisher) and I wish to clarify what exactly I meant in response to some of the questions that were put to me”.

The Defendants’ Legal Advisors

“With the benefit of hindsight, my firm should have appreciated that the later sales meant that paragraph 76 of the Original Defence was wrong, we should have brought this to the attention of the Claimants promptly and we should not have included the last sentence of paragraph 19G of the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim.”

“It would also have been appropriate to flag prominently in correspondence and/or in Dr Branney’s witness evidence that it had become apparent that the sales information previously given, in the belief it was true, was incorrect. Although the correct figures were indeed provided before trial, I accept that a prominent correction would have been appropriate together with a clear explanation for how the wrong figures were provided in the Affidavit (albeit innocently)”.

Expert Witnesses

Matthew Geale

David Dearman

“In this section of my report I have been asked to give my opinion on what the Claimants and the Defendants would have agreed as a reasonable royalty on sales of Infringing Garments in circumstances where the Defendants had sought a licence from the Claimants to use the Infringed Designs prior to the acts of infringement and where the parties were willing licensors and licensees respectively”.

“I must explain why I think the attempt to approximate real people to the notional [person] is not helpful. It is to do with the function of expert witnesses in patent actions. Their primary function is to educate the court in the technology - they come as teachers, as makers of the mantle for the court to don. For that purpose it does not matter whether they do not approximate to the skilled [addressee]. What matters is how good they are at explaining things.”

Additional Factual Background

(a) “The First Claimant, through its then solicitors, first wrote to the First and Third Defendants on 19 April 2016, alleging passing off, and that eight Oh Polly garments (sold in various colourways) infringed its UKUDR and CUDR.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 4).