David Stone (sitting as Deputy High Court Judge) :

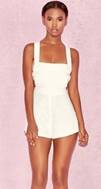

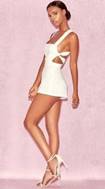

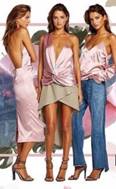

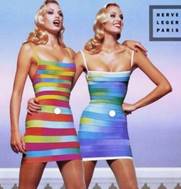

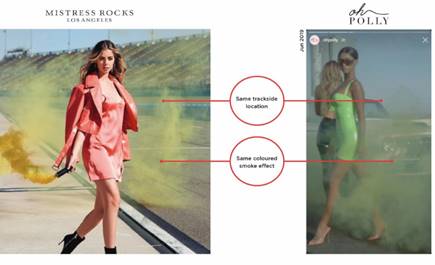

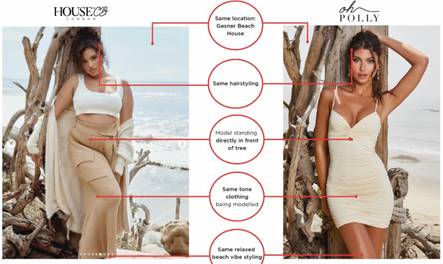

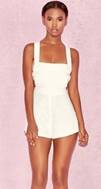

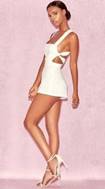

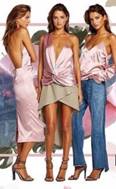

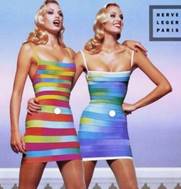

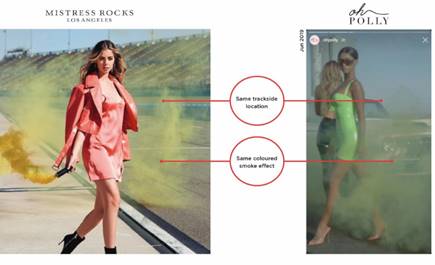

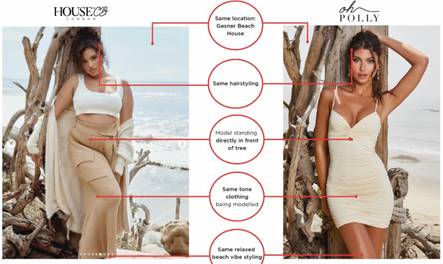

1. “Bodycon” and “bandage” are two dress styles made popular by celebrities including Jennifer Lopez, Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian. As the name suggests, bodycon dresses emphasise body contours, highlighting the wearer’s bust and buttocks, and minimising the waist. Bandage dresses have a similar effect, being made of thick, stretchy material like bandages. The Claimants sell bodycon and bandage garments under the main brand House of CB with a sister brand Mistress Rocks, mostly online, but with some bricks and mortar stores in the United Kingdom and the USA. They say that the Defendants, competitors who sell bodycon and bandage garments online under the brand Oh Polly, have copied 91 of their garment designs, including dresses, jumpsuits and tops, thereby infringing their unregistered design rights under UK and EU law. Further, the Claimants say that the Defendants have copied their business model, social media, marketing, packaging and presentation (including using the same models and the same locations for photoshoots) such that consumers will be deceived into thinking that Oh Polly is a sister brand to House of CB, so as to amount to passing off.

2. The Defendants deny design infringement, saying that, whilst on some occasions, House of CB garments were “referenced” in the production of Oh Polly garments, they were not copied. Thus, the Court is asked to determine when “referencing” or “inspiration” - a common feature of the fashion industry - ends, and unlawful copying begins. On the passing off case, the Defendants admit that there are some similarities between the two businesses, but say those similarities are common amongst many online fashion businesses, and no consumers have thought or will think that Oh Polly is a sister brand to House of CB.

3. By and large, it is sufficient throughout this judgment to refer to the two sides, without specifying any particular claimant or defendant. For completeness, I note as follows:

i) The First Claimant is a Hong Kong-registered company that operates the websites at

www.houseofcb.com and

www.mistressrocks.com. In addition to its e-business, the First Claimant has also entered into agreements with franchisees, including the Third Claimant, which sell its garments through bricks and mortar stores.

ii) The Second Claimant is also a Hong Kong-registered company, which owns various registered trade marks (which are not in issue in these proceedings). It licenses those trade marks to the First Claimant.

iii) The Third Claimant operates bricks and mortar retail stores in the United Kingdom, with stores in London, Sheffield and Manchester.

iv) The First Defendant is a company registered in England and Wales - it carried on the Oh Polly business from 2015 until 2017, when the business was transferred to the Fourth Defendant. It now has a share of a warehouse and receives rent from the Fourth Defendant.

v) The Second Defendant, Ms Claire Henderson, is the CEO of the Oh Polly business.

vi) The Third Defendant, Dr Michael Branney, is the Managing Director of the Oh Polly business. Each of Ms Henderson and Dr Branney owns 50% of the First and Fourth Defendants. They have admitted for the purposes of these proceedings that they would be jointly liable with the First and Fourth Defendants for any acts of unregistered design right infringement and/or passing off.

vii) The Fourth Defendant is a company registered in Scotland - it carries on the Oh Polly business today, and has since 2017.

4. The progress of the matter from complaint to trial was not particularly happy. The First Claimant, through its then solicitors, first wrote to the First and Third Defendants on 19 April 2016, alleging passing off, and that eight Oh Polly garments (sold in various colourways) infringed its UK unregistered design rights (UKUDR) and Community unregistered design rights (CUDR). A further letter before action was sent on 25 November 2016, this time relying on 19 designs, none of which had been included in the initial letter. The Defendants did not respond to that letter.

5. Eighteen months later, on 6 June 2018, a further letter before action was sent, this time to the Second, Third and Fourth Defendants, listing 87 garments that were said to infringe the First Claimant’s UKUDR and CUDR. Only 9 of the 19 garments referred to in the letter of 25 November 2016 were included in this list. Without waiting for a response, the Claim Form in these proceedings was issued the next day.

6. The Defendants did not respond to the claim, and the Claimants issued an application for judgment in default. After a compromise, directions were agreed for the service of a Defence. There was a hearing on 21 November 2018 before Zacaroli J, who made orders to keep confidential the names of the designers of garments on which the Claimants relied. The Defence was finally filed on 25 January 2019, some six months following service of the Claim Form. The Claimants filed their Reply some five months later on 14 June 2019, together with draft Amended Particulars of Claim. That latter document abandoned design infringement in relation to 15 of the 87 pleaded garments, and added a further 23 new garments, four of which claims were abandoned prior to the formal application to amend.

7. The first CCMC took place before Deputy Master Nurse on 15 October 2019, who accepted on case management grounds that the case ought to be “streamlined” and listed this trial. The Amended Defence was served on 31 January 2020. A second CCMC took place before Deputy Master Nurse on 7 April 2020 at which streamlining was ordered - each side was directed to select 10 garments to be dealt with at this trial (along with the passing off claim), with the design infringement claims in relation to the remaining 71 garments stayed. Each side selected 10 garments on 13 May 2020, but the Claimants did not like the garments selected by the Defendants, and issued an application to have the trial of the Defendants’ 10 selected garments stayed. That application was heard by Deputy Master Lloyd on 20 August 2020 and dismissed with costs.

8. The selected garments for this trial each have a number, with C representing the Claimants’ garment in which UKUDR and CUDR are asserted, and D representing the Defendants’ garment which is alleged to infringe. The garments in this trial are: C2/D2, C3/D3, C4/D4, C7,/D7, C9/D9, C12/D12, C13/D13, C17/D17, C21/D21, C35/D35, C47/D47, C49/D49, C61/D61, C63/D63, C66/D66, C77/D77, C81/D81, C91/D91, C93/D93 and C102/D102. Images of each garment appear below. Each of the garments also has a name - in the case of the Claimants, usually a woman’s name, and in the case of the Defendants, usually a pun, innuendo or play on words. For clarity and simplicity, I have used the garment numbers rather than names.

9. Fact evidence was finally exchanged on 2 October 2020, just two months before the trial. I heard the Pre-Trial Review on 26 October 2020, and made orders for a Re-Amended Defence, a Re-Amended Reply and reply evidence. I also lifted Zacaroli J’s confidentiality order for reasons I gave at the time.

10. In the end, at this trial, the Court was asked to assess 20 garments for infringement, each in relation to both UKUDR and CUDR. In relation to CUDR, several of the garments were available in multiple colourways, each of which had to be assessed. The Defendants relied on 108 prior designs in an attempt to invalidate the Claimants’ UKUDR and CUDR. As will become apparent from the length of this judgment, that task involved comparing each of the Claimants’ 20 designs against the prior designs for validity under UKUDR and then under UCDR (the latter sometimes involving multiple colourways). It then involved comparing each of the Claimants’ 20 designs against each of the 20 allegedly infringing garments, in each case under the two different legal regimes (UKUDR and CUDR, with the latter involving multiple colourways). That involved something over 270 comparisons under two different legal regimes.

11. By the end of the trial, counsel for the parties agreed that the designs in issue fell within only three “buckets”, to which I return below. I am therefore moved to repeat what Henry Carr J said in Neptune (Europe) Limited v Devol Kitchens Limited [2017] EWHC 2172 (Pat) (Neptune), at paragraph 4:

“At the pre-trial review, I ordered that the issues of liability in relation to the unregistered design rights were to be tried based upon 3 designs selected by Neptune and 3 designs selected by DeVOL. With hindsight, it would have been better if I had limited the parties to a single design each, as the same issues could have been fully argued. In future (irrespective of whether the claim is part of the Shorter Trial Scheme) where multiple designs are in issue, it would be sensible to confine the liability trial to an appropriate, and limited, selection.”

12. If the garments before the Court in this trial are representative of the 91 garments in issue in the proceedings (and the Claimants say they are), then this trial could readily have been heard in relation to three garments only, so as to dispose of the remaining 88 garments by consent (or by relisting any garments that could not be agreed). This would have saved the parties considerable time and costs.

13. The trial was heard remotely because of Covid-19 precautions, using photographs of the various garments rather than the garments themselves. At the request of the Defendants, the Court reconvened following closing speeches for a viewing of the 20 garments relied on by the Claimants and the 20 garments alleged to infringe, with only counsel and the transcript writer present. Whilst unusual, this was a useful exercise and enabled me to compare the garments side by side, allowing counsel to draw to my attention similarities and differences. I also had the garments available to me whilst preparing this judgment. Whilst what was made available to me may have been the only articles the parties could obtain, in a case such as this in future it would be preferable for the physical examples provided to be in comparable sizes, and comparable colourways. There are additional challenges when comparing one example in size XS and one in size XL.

14. This judgment contains an unusually large number of pictures, aimed at reducing the word count necessary to describe each garment. I regret that a number of the images have cropped the model’s head and in using these, I mean no disrespect to the models: these were, unfortunately, the only images available to me. I also note that some of the garments were described as “nude” in colour. Criticisms of that usage have been made for at least 10 years. I have, however, adopted and capitalised the parties’ use.

15. I have excerpted below social media posts from members of the public who were not called to give evidence and likely do not even know that these proceedings are underway. To preserve their anonymity, I have not referenced their social media handles, but they were in evidence before me. When quoting from social media posts, I have not used “[sic]”: the text and emojis are reproduced exactly.

16. The trial occurred prior to the United Kingdom’s departure from the EU-wide design regime established by Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (the Design Regulation), but this judgment is to be handed down following that exit. I was asked by counsel for both sides to decide the case on the basis of the law as it was at the time of the trial, and hence I refer to the Design Regulation, rather than to the relevantly identical UK law which replaced it at 11pm on 31 December 2020. It should also be noted that at the time of the trial, this court was sitting as a Community Design Court, but it had ceased to be such a court by the time of hand-down. As no pan-EU remedies were sought, this makes no difference, and the parties did not ask for hand-down to take place prior to 31 December 2020.

17. There were no major disputes between the parties as to the applicable law, so this case turns entirely on its facts.

18. Ms Anna Edwards-Stuart and Mr David Ivison appeared for the Claimants. Mr Chris Aikens appeared for the Defendants.

19. The Claimant relied on four witnesses, each of whom was cross-examined remotely at trial. Some witnesses gave evidence from outside the jurisdiction: I was assured by counsel for the parties that local laws had been complied with. I am grateful to the firms of legal advisors who hosted the witnesses to enable them to give their evidence remotely.

20. Ms Connor Walker founded what is now the House of CB business now owned by the Claimants when she was 17 years old and travelling in Asia with her parents. As Connor Walker’s cousin Kirsty Walker also gave evidence, I will use both women’s first names without thereby meaning any disrespect.

21. Connor Walker remains heavily involved in the business, and continues to design garments for the House of CB brand. She gave evidence of the development of the business from that owned by a teenager selling dresses on eBay to the multi-million Pound business it is today.

22. Counsel for the Defendants submitted that Connor Walker was not a helpful witness describing her as “visibly impatient”. He pointed to what he said were inaccuracies in her evidence and/or issues on which she failed to accept matters put to her, and submitted that I should approach her evidence with some caution. I disagree. Connor Walker was clearly trying her best to assist the court. She did come across as impatient with some of the allegations put to her, but no more so in my judgment than some-one who feels that her designs and her business model have been copied by a third party. I have carefully reviewed the five examples of alleged inaccuracies presented by counsel for the Defendants, and I do not consider that they demonstrate unhelpfulness or the unreasonable refusal to accept matters which he submitted. Further, none of the examples given could be said to go to any key issue in the case.

23. Ms Joanna Richards is Connor Walker’s mother and is actively involved in running the House of CB business. Ms Richards’ witness statement addressed the appearances and features of the House of CB and Oh Polly websites, and the models and packaging they use.

24. Counsel for the Defendants submitted that Ms Richards tended to argue the case, and that I ought to treat her evidence with caution. Again, I disagree. I found her to be an honest and straightforward witness. Whilst she occasionally came across as feeling aggrieved by the Defendants’ actions, that cannot be held against her. She accepted under cross-examination inaccuracies as they were put to her.

25. Ms Georgina Douek is a designer employed by Sirens Design. Sirens Design is a design agency set up and owned by the Claimants to design garments for House of CB and Mistress Rocks: I return to it below. Ms Douek gave evidence that she was the designer of five of the garments in issue at this trial (C4, C12, C17, C61 and C93). She was also involved in the design of C21. Her statement also described the general design process at Sirens Design. No criticism was made of the way in which Ms Douek gave her evidence.

26. Ms Kirsty Walker is Ms Richards’ niece and Connor Walker’s cousin. She is a Warehouse Supervisor employed by Stocks Away Limited since 2014. She supervises a team who dispatch House of CB garments to consumers and deal with returned goods. No criticism was made of the way in which she gave her evidence.

27. Counsel for the Defendants criticised the Claimants for the witnesses they did not call:

i) the four other designers involved in the design of garments in issue in this trial: Rheanna Donaldson, Julia Kasper, Justin Ruddle and Alcy Lynch; and

ii) any individual who had actually been misled or confused that Oh Polly is a sister brand of House of CB.

I return to these criticisms below.

28. The Defendants served witness statements from eight witnesses, six of whom were cross-examined.

29. Ms Claire Henderson is the Second Defendant and CEO of the Fourth Defendant. Her brother Mr Joe Henderson did not give evidence, but he is relevant to the proceedings. I will refer to her as Ms Henderson and to him as Mr Henderson.

30. Ms Henderson gave evidence that she designed 17 of the 20 Oh Polly garments in issue in this trial. Her two witness statements set out her “design process” generally, as well as specifically in relation to the 17 designs.

31. Counsel for the Defendants accepted that “on some occasions” Ms Henderson “could have answered the specific questions put to her in a more straightforward and direct way and that she had a tendency to repeat herself”.

32. Counsel for the Claimants went further than that: she described Ms Henderson’s oral evidence as “a disaster”. It was, she said, impossible to get a straight answer from Ms Henderson in response to any question which she perceived as being problematic for the Defendants’ case. I accept that submission. Ms Henderson’s answers were rambling, obfuscatory and at times incoherent. She repeated some answers many times, even when not relevant to the question and having several times been requested by me to answer the question put to her. On this basis alone, I would have approached her evidence with some caution.

33. However, I have come to the conclusion, regrettably, that I must accept counsel for the Claimants’ submission that Ms Henderson has lied to the court. I therefore need to set out three issues in detail.

The Dropbox Exhibits

34. In her first witness statement, Ms Henderson gave evidence that between August 2015 and January 2018, she was designing 40 to 50 garments per month. She maintained an archive of images of tens of thousands of third party garment designs (potentially as many as 50,000) that she had downloaded from the Internet. Ms Henderson gave written evidence that to come up with an Oh Polly garment, she would research trends and then “conceptualise… the appearance of my own design in my head”.

35. I set out in full paragraph 37 from Ms Henderson’s first witness statement:

“Say there was a particular trend, for example Kim Kardashian wore a lace up dress which started to trend, I would have an image of the sort of design I wanted to produce as my own version of that popular or trending style. At this point, I might go through my saved pictures and set up a new folder on my laptop and put into that folder all the images of dresses that were very similar, that had a particular colour or maybe that had a little design feature that I thought would work well with the lace up design I had in my head. Other times, it was quicker to do an internet search to find an image similar to the concept I had in my head for illustration purposes, rather than go back through images I’ve already saved. Instead of printing material out, my moodboard is a folder of images. From there, I use the images as a reference point for the design of the garment I had conceptualised in my head and which I wanted to produce.”

36. Ms Henderson referred to these mood board folders in her discussion of the design process for each of the particular garments in issue. For example, in relation to D4 she said (at paragraph 51 of her first witness statement):

“In 2018, bralettes were really in style and the single-shoulder, knotted effect appeared to be a trend, particularly for swimwear, as evidenced by the images I had saved and are visible at CLH16.”

37. Exhibit CLH16 is headed “Bralettes and Shoulder Knots” and shows a list of links to images held in Dropbox as part of Ms Henderson’s archive. The dates on which those Dropbox images were saved are given - in CLH16, the last date given is 3 June 2016 (D4 was conceived in March 2018). There are also a series of images set out in CLH16. I will refer to CLH16 and the similar exhibits for different garments as the Dropbox Exhibits.

38. In relation to D7, having referred to images of Liz Hurley and Mariah Carey in strappy dresses, Ms Henderson wrote at paragraph 53 of her first witness statement:

“Both garments are fairly basic, as evidenced by the research I had done and the images I had saved, which are visible at CLH18.”

39. Dropbox Exhibit CLH18 is similar in presentation to CLH16. It is headed “Neckline and Strappy Back Dresses”, and lists two Dropbox addresses, one saved on 6 April 2016 and one saved on 21 April 2016. Neither shows Liz Hurley or Mariah Carey. D7 was conceived in October 2017.

40. Ms Henderson’s first witness statement made similar claims in relation to D2, D9, D12, D13, D17, D21, D35, D47, D49, D61, D66, D77, D81 and D91, for each of which she provided a Dropbox Exhibit in a relevantly identical format and with similar content. A Dropbox Exhibit was therefore provided by Ms Henderson in relation to 16 of the 17 designs in issue before me for which Ms Henderson was identified as the designer: there is no Dropbox Exhibit for D63.

41. Thus, as I understood Ms Henderson’s written evidence prior to the start of the trial, it was that she created digital mood boards - and they were represented by the Dropbox Exhibits. As it turned out, and as Ms Henderson’s oral testimony stood at the conclusion of her second day of cross-examination, the Dropbox Exhibits were not that at all. Rather, they were documents created for the purposes of these proceedings, which recorded garments that Ms Henderson had found in her archive on a review conducted whilst preparing her written evidence. They captured garments which she may have looked at - or at least, documents which looked like the garments in issue in this trial. An excerpt from her cross-examination is set out below:

“Q. And if you scroll down you can see those two images there which, presumably, correspond to the two Dropbox links?

A. Yes, I believe so.

Q. Ms. Henderson, do you say that in the course of preparing, of creating the design for [D7] you actually looked at either of the two dresses in the top image or the dress on the bottom image?

A. My Lord, I think I would have been familiar with them, yes, because usually my process, as I have set out numerous times now, when I am looking at creating a new design, I will also, let us just say, for example, that I have the Mariah Carey image and the Liz Hurley image and I like those and that is a design that I want; I will still refer to my Dropbox to see if there is any features that maybe in my Dropbox I have saved that I like. So I will refer to those, yes.

Q. Ms. Henderson, you did not answer my question.

A. Sorry, what was the question?

Q. My question was, in the course of designing [D7] ----

A. Okay.

Q. ---- did you, as a matter of fact, go back to your Dropbox and look at any of the dresses that we see on page I1300 or I1302, "yes" or "no"?

A. I believe I would have, yes, my Lord. I believe I would have.

Q. I am not asking you what you believe. Did you, Ms. Henderson, "yes" or "no"?

A. I believe, based on the process that I used to work, I would have seen these, yes. I do not believe that the process to create this garment would be any different to the process that I used to create every garment. So with that regard, yes, I would have seen these images. To the best of my knowledge, yes, I believe I would have seen these images.

Q. The answer, Ms. Henderson, is you do not know?

A. It is not the answer, my Lord. If it was the answer I would be honest and that is what I would say.

Q. You do not know because you have just said you "believe". You do not say you know, you do not remember?

A. I believe I would have because that is the process that I use for every single garment that I produce. That is the purpose of me having my Dropbox and having all the folders. It is so that I can refer back to them on a frequent basis which is what I do. It is what I did all day every day.

Q. I will ask you one more time, Ms. Henderson.

A. Okay.

Q. Are you confident, as a matter of fact, that you looked at each of these dresses in the course of designing D7?

A. I am confident, yes.

Q. Are you confident yes or no?

A. Yes, I am confident, my Lord. I am confident based on how I design a garment. I am confident. That is how I design a garment. I have something in mind, even if I have a specific, even if my idea and I have an illustration and it is very clear, I will always, always, always go back to my Dropbox, because there may be another add-on feature in my Dropbox that will help enhance the design. I refer back to my Dropbox for colours. I am always within those folders, always.”

42. At the end of her cross-examination, I asked Ms Henderson some questions about one of the Dropbox Exhibits:

“Q. Did you prepare that document?

A. I put the images together. I had phone calls with [Dr Branney] over the course of about one week and we put the images together. So it was myself who went through my Dropbox because, obviously, [Dr Branney] is not so aware and then he would put he had put them together for the lawyers, I believe, yes.

Q. Roughly when did that happen?

A. I think it was about June time, June/July, yes, maybe like June when I, before I left, so probably about June, maybe.

Q. All right, and that is true for each of the documents you were taken to that looks like this, so each of the lists of computer codes?

A. We went through all of the designs, my Lord, yes. It took quite a while. But in putting the document together that was [Dr Branney] who had actually put it together, if you know what I mean. I did not sit here putting it together. I just went through on phone calls and confirmed the images with him and then sometimes he would show me an image just to confirm if it was from my laptop.”

43. Having seen Ms Henderson give her oral evidence and having reviewed each of the Dropbox Exhibits, they are, in my judgment, documents put together for the purposes of these proceedings, as Ms Henderson accepted by the end of her testimony. They were created in June or July of 2020 when Ms Henderson was preparing her evidence for this trial. They were created by Ms Henderson and Dr Branney. I have no confidence at all that these are images of garments Ms Henderson referred to in the creation of the garments in issue in this trial. Ms Henderson’s own evidence was that she was designing 40 to 50 garments a month in the relevant time frame. She had tens of thousands (possibly as many as 50,000) images of garments in her Dropbox. It is simply not possible that she was able to reconstruct the list of images from which she took inspiration, nor did she, under cross-examination, make that case. They are therefore not the “new folders” or “moodboards” that Ms Henderson referred to in paragraph 37 of her first witness statement. Therefore, even if Ms Henderson’s first witness statement is not technically inaccurate (and I consider that it is), it certainly gives a misleading picture of what the Dropbox Exhibits represent.

44. That misleading impression is amplified by the Re-Amended Defence and the Amended Annexes to the Defence. The Re-Amended Defence notes at paragraph 38(a) that Annexes D1 to D106 contain “Particulars of the design of each of the Oh Polly garments alleged to infringe, namely the dates of design, who created it, their employment status, and images of any third party, Oh Polly or House of CB designs referenced during the design process that the Defendants have been able to provide” (emphasis added). This document was signed by Ms Henderson and by Dr Branney under a statement of truth on 28 October 2020, after they had prepared the Dropbox Exhibits, and shortly before the trial.

45. For each design, each Amended Annex has a Section 5 titled Particulars of Defendants’ Design. That section includes: 1. Date of design; 2. Designer/status; and 3. Designs referred to. Under the last of those headings, the images taken from the Dropbox Exhibits are set out. This is, in my judgment, an express representation that the designs shown were actually referred to by the named designer at the time of the listed “date design conceived” and prior to the listed date the design was finalised. In every case, that representation is incorrect for the reasons I have given. Ms Henderson was the named designer in relation to the 17 garments: she, and only she, knew authoritatively the third party garments to which she had referred.

46. There are several other reasons for suspecting the Dropbox Exhibits:

i) There is a Dropbox Exhibit for design D35. The Defendants admitted that D35 was copied from the Claimants’ C35 garment, and that no other garments were “referenced” by Ms Henderson when designing D35. Yet a Dropbox Exhibit exists, allegedly setting out the other documents referred to. Like others of the Dropbox Exhibits, that for D35 includes images for garments that are very dissimilar to the garment Ms Henderson said she then designed. For example, shown below are images of C35, D35 and some of the images shown in the Dropbox Exhibit for D35:

C35 D35

Excerpted images from the Dropbox Exhibit for D35

In cross-examination, Ms Henderson first said that she had “referenced” the images in the Dropbox Exhibit for D35, before later admitting that she had not “referenced” these images at all. Given the similarities between D35 and C35 (they are close to identical) and the very great differences between D35 and the images shown in the Dropbox Exhibit for D35, her later admission, which is consistent with the pleadings, seems significantly more likely, and I so find;

ii) The computer file references shown in the Dropbox Exhibits identify different folders and sub-folders which are not named after the Defendants’ garments or features of those garments;

iii) The dates on which the computer files were saved span a period of many months and hence do not suggest that they were accessed and saved over a short space of time during what Ms Henderson described as her research;

iv) The dates on which the computer files were saved are in all cases months, and in some cases years, prior to the pleaded date of creation of the Defendants’ garments;

v) Some of the Dropbox Exhibits included images which did not reflect the features of the garments for which they were alleged to have been research, or, indeed, the heading of the document. For example, the Dropbox Exhibit for D49, a satin mini dress, does not contain any images of satin mini dresses, even though it is headed “Satin mini dressed [sic]”. Instead, it contains images of tops, pantsuits and two dresses to the knee and below the knee, in a variety of fabrics; and

vi) The Defendants now admit that they referenced specific garments (some from House of CB, some from third parties) in relation to each of the Defendants’ garments, but those referenced garments do not appear in the Dropbox Exhibits.

47. Following cross-examination, the Defendants persisted with the argument that Ms Henderson created digital mood boards from which she was inspired, including mentioning as much in their counsel’s closing skeleton. In my judgment, there is no reliable evidence before me that Ms Henderson created mood boards, digital or otherwise, for the garments in this trial which she was said to have designed.

48. Ms Henderson knew that the Dropbox Exhibits were documents created for the purposes of these proceedings. She presented them, and allowed them to be presented, as “digital mood boards” that inspired her at the time she created the relevant designs, right up until her counsel’s closing speech. Her counsel accepted that it was “unfortunate that [Ms Henderson’s] precise methodology was not spelt out in [her] witness statement”. I agree. It was both unfortunate and misleading.

The Amended Defence

49. Counsel for the Claimants raised a point in relation to the pleadings that also goes to the reliability of Ms Henderson’s evidence. Ms Henderson signed the Defence under a statement of truth in early 2019. That document included the following statement:

“Save that garment C35 was referenced in the creation of the design for garment D35, the Defendants created the designs for the Oh Polly Garments independently and without copying any of the designs relied on by the Claimants.”

50. As will become apparent, the Defendants have now conceded that the Claimants’ garments were referenced by Ms Henderson on at least 9 occasions in relation to the 20 garments in issue in this trial. The Defence was later amended and re-amended, such that the Re-Amended Defence before me reads as follows:

“Whilst in some instances a House of CB garment was referenced in the creation of the design for the Oh Poly garment, in all cases other than D35, for which the allegation of copying is admitted, the Defendants created the designs for the Oh Polly Garments without copying any of the designs relied on by the Claimants.”

51. The Defence was therefore false at the time Ms Henderson signed it. Counsel for the Claimants submitted that Ms Henderson lied when she signed the Defence, and I accept that submission. Again, she had designed the garments in issue and if she was unable to recall her inspiration/references, she had access to her records (including the Defendants’ internal record keeping database, called Trello, to which I return below) and should have consulted them.

52. I therefore consider Ms Henderson also to have lied when she signed the original Defence.

Ms Henderson’s Design Process

53. It was common ground that Ms Henderson cannot draw. She also cannot use any of the available computer assisted design programs. Her evidence was that she designed by looking at trends from images she had collected in her Dropbox, designed the details of each garment in her head, and then looked for images of existing garments which she could use to show the factory what it was she wanted made. There are no documents which (and no other witnesses who) back up this aspect of her account of her design process.

54. As set out above, Ms Henderson admitted under cross-examination that the Dropbox Exhibits were post facto documents created for the purposes of this litigation. She was unable to identify clearly in relation to any of the Defendants’ 17 garments she designed the actual third party images she had looked at in advance of her designing, and there was no evidence, other than her say so, that she had conceived of the full design in her head prior to going looking for an image or images which would enable her to demonstrate to the factory what she wanted. Instead, the written record shows that in each of the 17 cases, Ms Henderson identified at least one garment (being a House of CB garment or a third party garment), an image of which she emailed to Dr Branney and/or Mr Henderson or otherwise provided directly to the factory. I consider her version of her design process to be a fabrication, concocted to get around the very real difficulty that Ms Henderson took images of the Claimants’ garments (and third party garments) and sent them to the factory to be made up.

55. I therefore, regrettably, accept counsel for the Claimants’ submission that Ms Henderson’s evidence cannot be trusted. In my judgment, she set out to deceive the Claimants and the Court in relation to her overall design process, and the design of the particular garments before me. In her oral testimony, she gave whatever answer she felt best at that moment to assist her case. That criticism also extends to her written testimony. I have therefore discounted her evidence completely unless it is corroborated by another witness or the documents before me.

56. Dr Michael Branney is the Third Defendant and Managing Director of the Fourth Defendant. Dr Branney is largely responsible for running the operations of the Oh Polly business. He manages the staff and the website. His first witness statement set out some of the background to the Oh Polly business, its structure and focus, its aims, and various aspects of the running of the business. Dr Branney’s first witness statement also addressed the allegations of similarities between the Oh Polly business and the House of CB business. His second witness statement responded to the written evidence of Connor Walker, Ms Douek, Ms Richards and Kirsty Walker.

57. Counsel for the Claimants criticised Dr Branney as an argumentative and difficult witness, prepared to advocate for himself and the Defendants. There is some force in those criticisms. More seriously, counsel for the Claimants also pointed to Dr Branney’s dishonesty in relation to the original Defence, and in particular the passage I have excerpted above in relation to Ms Henderson’s evidence, suggesting that he was “willing to tell lies to further his and the other Defendants’ interests”.

58. Prior to signing the Defence, Dr Branney had conducted a review of the Defendants’ internal records, including the Trello system to which I have already referred, and to which I return in more detail below. At the time of signing the Defence, Dr Branney “could not identify a House of CB image in the Trello card[s]”. He accepted under cross-examination that the Defence was “wrong”. But his explanations for how he failed to recognise the House of CB garments on at least nine occasions were unconvincing.

59. Dr Branney was taken to several Trello records in cross-examination, and asked to compare the images there with the images of the Claimants’ garments which had been annexed to the Particulars of Claim. I set out below the image or images from the Trello records which Dr Branney was shown, and the image from the Particulars of Claim that Dr Branney was shown:

Images from Trello cards Images from Particulars of Claim

60. I accept counsel for the Claimants’ submission that “a perfunctory glance reveals the garments in these images to be the same”. Dr Branney was unable to explain how he missed these three images of the Claimants’ garments when he signed the Defence and I do not accept the explanations he gave. The Defendants took over 6 months after receiving the Particulars of Claim to file their Defence, and had ample opportunity to get this right. However, I consider Dr Branney’s failing here to be maladroit, rather than malevolent. He had not designed the garments in issue - Ms Henderson had. He was working from documents and from Ms Henderson’s explanations. He ought to have been more careful before signing the statement of truth, but I do not consider that this means I should discount his evidence completely.

61. Counsel for the Claimants described Dr Branney’s evidence as that “of a person willing to say whatever needed to be said to achieve his objective.” Having watched him give evidence, I consider that Dr Branney was an active advocate for the Defendants. I have therefore approached his evidence with caution, but I reject counsel for the Claimants’ submission that I should dismiss it altogether.

62. Ms Alexandra McShane is employed by the Fourth Defendant as a Customer Services Manager. She described in her witness statement the Oh Polly customer services team and returns process, including describing items from other retailers returned wrongly to Oh Polly. She was not cross-examined, and I therefore accept her evidence.

63. Mr Ramsay Bell is Oh Polly’s Head of Development. He described in his witness statement the history of the Oh Polly website, and gave examples of third party websites with features similar to those relied on by the Claimants for their passing off case. He was not cross-examined, and I therefore accept his evidence.

64. Ms Arlene McNab is employed by the Fourth Defendant as an E-Commerce Manager. Her witness statement primarily described the rebranding process that Oh Polly went through in early 2018. In cross-examination, Ms McNab’s attention was drawn to some errors in her evidence. Counsel for the Claimants criticised the way in which Ms McNab’s written evidence had been prepared, but not the way in which she gave her oral testimony, which I therefore accept.

65. Ms Amy Johnston is a Senior Designer employed by the Fourth Defendant. She was the first specialist designer employed in the Oh Polly business (in November 2017). Her evidence covered the design of two of the Oh Polly garments in this trial (D3 and D93). Counsel for the Claimants accepted that Ms Johnston answered fairly the questions put to her in cross-examination, but she submitted that, in fact, Ms Johnston was “often little more than Ms Henderson’s amanuensis, using an iPad app to sketch out ideas supplied to her by Ms Henderson”. I return to this issue below in relation to D3 and D93.

66. Ms Megan Mitchell is a Creative Brand Specialist at Oh Polly. Her written evidence addressed Oh Polly’s social media activities and other aspects of Oh Polly’s marketing strategy. Counsel for the Claimants accepted that Ms Mitchell had given her oral evidence in a straightforward way, but criticised the preparation of her witness statement. For example, Ms Mitchell’s witness statement said that she had been “referred to the Particulars of Claim”, when in fact she had never seen the document. Counsel submitted that Ms Mitchell was “not particularly well-engaged with the production of her witness statement”. I accept that submission. However, whilst regrettable, I do not consider it makes any difference to the matters I need to decide.

67. Ms Shauni Connell is a Senior Womenswear Designer employed by the Fourth Defendant. Her witness statement described her creation of the design for D102. Ms Connell explained in a straightforward way the inspiration for her design for D102. Counsel for the Claimants submitted that D102 ended up closer to Ms Johnston’s sketches than Ms Connell’s, but accepted that her evidence was given honestly.

68. I understand the following account of the background facts not to be contested.

69. In 2009, Connor Walker began purchasing bandage dresses in China whilst accompanying her parents on business trips. She brought the dresses back to the UK and sold them through eBay. She called this business Celeb Boutique. In 2010, Connor Walker built the website at

www.celebboutique.com to move her business away from eBay. Through that website, she sold bandage and bodycon dresses. Connor Walker used social media to promote sales. In 2011, she started giving dresses to celebrities including reality television stars such as the cast of The Only Way is Essex. Later that year, the First Claimant was incorporated to manage the Celeb Boutique business.

70. Until 2012, the garments for sale through the Celeb Boutique business were purchased from wholesalers. Connor Walker now accepts that some of those garments were copies of third party designers, including a number of dresses copied from designs by Hervé Léger.

71. In 2012, Connor Walker moved Celeb Boutique towards designing its own garments. Siren Branding Limited was set up for that purpose. The design business of Siren Branding Limited was transferred to Sirens Design Limited in 2014: as it does not matter for the purposes of this case, I refer to both entities as Sirens Design. All rights in designs created by Sirens Design are owned by the First Claimant. Eventually, Celeb Boutique opened its own factory to manufacture the garments designed by Sirens Design on its behalf.

72. In July 2013, Celeb Boutique opened its first bricks and mortar store at Westfield Stratford City shopping centre in London.

73. Also in 2013, Connor Walker decided to rebrand the Celeb Boutique business as House of CB. “House of” was taken from the French term “Maison de” which is used by traditional couture houses. CB, the initials of Celeb Boutique, maintained some brand continuity. A new logo and a new website were developed, with

www.houseofcb.com going live in July 2014. The physical stores were rebranded at the same time. Following the rebrand, turnover increased significantly, as did the number of celebrities wearing the brand’s clothing (including Jennifer Lopez and members of the Kardashian family). The business expanded to the USA, and a physical store was opened in Los Angeles in June 2015 for which Khloe Kardashian hosted the opening party.

74. In April 2014, Connor Walker launched a sister brand: Mistress Rocks. Mistress Rocks is aimed at a slightly younger customer than House of CB. Mistress Rocks garments are also designed by employees of Sirens Design.

75. The clothing business that became Oh Polly also started out on eBay, with Ms Henderson selling some of her own clothing and other items while still at university. In 2013, Ms Henderson and Dr Branney started using the name Polly Couture for that business. It was a success. The First Defendant was incorporated in 2013 to conduct the eBay business.

76. In 2015, Ms Henderson and Dr Branney decided to set up their own business. They adopted the name Oh Polly for that business, and launched a website at

www.ohpolly.com in August 2015. The Fourth Defendant took over the business in June 2017. Ms Henderson’s evidence was that at the start of the Oh Polly business, she designed all the garments sold by the business, designing 40 to 50 garments per month. Ms Johnston joined Oh Polly as a designer in 2017. Oh Polly garments are made in factories in Bangladesh and China.

77. The Defendants used a software program to assist with the manufacture of garments, called Trello. Within the Trello system, there are “cards” which track the development of a garment from design through to the end of manufacture. Trello records for each of the Defendants’ garments were in evidence before me. In each case, the Trello records included images uploaded to Trello by Ms Henderson, Dr Branney and Mr Henderson. They also included images of various fittings for the garments, as well as instructions for the factory to make changes. The Defendants accepted that some of the Trello records were not complete - that is, there could have been additional images or instructions given and/or received which have not been recorded.

78. I need to say something about mood boards. The Claimants’ evidence was that they created mood boards for each collection by collating images from magazines and the Internet, fabric swatches and the like, and pinning them to foam boards fixed to the wall of the design studio. These mood boards set the tone for the garments then to be designed. This is common practice in the fashion industry. An image of Connor Walker at one of the Claimants’ mood boards is shown here:

79. The Claimants’ practice was for mood boards to remain in place for approximately six weeks whilst garments were designed and fitted. At the end of that time, the images and fabric swatches, etc, would be removed and thrown out.

80. Counsel for the Defendants was highly critical of the Claimants’ failure to preserve and disclose the appearance of the mood boards used in the design of the garments in issue in these proceedings. Even if it was not practicable to preserve the boards themselves (because they were fixed to the wall of the studio, and were needed for the next collection), he said photographs should have been taken of them, and the actual images/fabric swatches retained and disclosed.

81. Counsel for the Claimants’ answer was a simple one - the obligation on the Claimants was to preserve disclosable documents “as soon as litigation is contemplated”, and they have done so. The Claimants, she said, can only contemplate litigation in respect of a design after it has come to their attention that the Defendants have released a similar garment - by then, months, sometimes years or more, have passed - and hence the mood boards have already been disbanded. Further, counsel for the Claimants submitted:

“For their allegation of deliberate destruction of disclosable documents to be sustainable, it would have to be the Defendants’ position that the Claimants are obliged to ensure that their design companies preserve all of their mood boards for an indefinite period - even though they have no use for them - in case at some point in the future they come to suspect that the Defendants have copied another of their garments. That is clearly wrong.”

82. I agree with that submission. Whilst litigation against the Defendants was contemplated since 2016, and initiated in 2018, that does not place on a party an obligation to preserve all documents - only disclosable documents. A document will be disclosable only if it is relevant to proceedings. A mood board may be relevant to any infringed garments designed following consultation of the mood board, but, as set out above, that was not known at the time the mood boards in issue were taken down. The Claimants have in the last few years created thousands of garment designs - only 20 were in issue before me. By the time those 20 garments were identified (because of the allegation that the Defendants had copied them), the mood boards were already long gone. I do not consider that an allegation of infringement of UKUDR (or indeed CUDR) carries with it an obligation immediately to preserve all documents created by the claimant (or putative claimant).

83. I should add for completeness that I do not interpret the disclosure rules as imposing an obligation to create documents - only to preserve existing documents. I therefore cannot readily see how the Claimants can be criticised for not photographing the mood boards in the absence of a duty to preserve them.

84. Finally, although Connor Walker was skilfully cross-examined in relation to the mood boards, that line of enquiry went nowhere: Connor Walker was clear that there was no untoward motivation in removing the mood boards. Further, both Connor Walker and Ms Douek denied that the Claimants’ garments were copied from garments shown on the mood boards, and they were not moved from that position in cross-examination.

85. I understood the parties to be in agreement on the principles to be applied, subject to the small number of controversies I refer to below.

86. Sections 213 and 226 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA) provide as follows:

“213.- Design right.

(1) Design right is a property right which subsists in accordance with this Part in an original design.

(2) In this Part “design” means the design of the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of an article.

…

(4) A design is not “original” for the purposes of this Part if it is commonplace in a qualifying country in the design field in question at the time of its creation; and “qualifying country” has the meaning given in section 217(3).

…

226.- Primary infringement of design right

(1) The owner of design right in a design has the exclusive right to reproduce the design for commercial purposes—

(a) by making articles to that design, or

(b) by making a design document recording the design for the purpose of enabling such articles to be made.

(2) Reproduction of a design by making articles to the design means copying the design so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to that design, and references in this Part to making articles to a design shall be construed accordingly.

(3) Design right is infringed by a person who without the licence of the design right owner does, or authorises another to do, anything which by virtue of this section is the exclusive right of the design right owner.

(4) For the purposes of this section reproduction may be direct or indirect, and it is immaterial whether any intervening acts themselves infringe the design right.”

Subsistence

87. Subsistence of UKUDR therefore requires:

i) That the design be “original”;

ii) That the designer or his/her employer is a “qualifying person”, or that articles made to the design were first marketed in a way which qualifies them for protection;

iii) That the design not be excluded from protection (“must fit, “must match” etc);

iv) That the design has been recorded in a design document or an article has been made to the design; and

v) That the term of the design has not expired.

88. The Defendants seriously contested only the first of these - originality. To qualify for UKUDR, a design must be original in two senses:

i) The “copyright sense”; and

ii) Not commonplace within the meaning of section 213(4) of the CDPA.

89. Arnold J (as he then was) addressed originality in the copyright sense in Whitby Specialist Vehicles Limited v Yorkshire Specialist Vehicles and Ors [2014] EWHC 4242 (Pat) at paragraph 43:

“In order for design right to subsist, a design must be “original” in the copyright sense of originating with the author, and not being copied by the author from another: see Farmers Build Ltd v Carrier Bulk Materials Handling Ltd [1999] RPC 461 at 475, 482. In Magmatic v PMS at [84] I expressed the view that the test is whether sufficient skill, effort and aesthetic judgment has been expended on the new design to make it original. During the course of argument in the present case, the question was raised whether “original” should be interpreted in the same manner as the CJEU has interpreted the requirement for originality in the context of copyright, that is to say, as requiring creativity on the part of the designer: see C-429/08 Football Association Premier League Ltd v QC Leisure [2011] ECR I9083, Case C-145/10 Painer v Standard Verlags GmBH [2011] ECR I-12533 and Case C-604/10 Football Dataco Ltd v Yahoo! UK Ltd [EU:C:2012:115]. I shall assume, without deciding, that this is the correct approach.”

90. The parties were agreed that the outcome of this case did not depend on a distinction between the two approaches. As the parties referred to this as “originality in the copyright sense” I have adopted that expression. I have also used the expression “slavishly copied” to mean a design created without originality in the copyright sense.

91. In addition to being original, to qualify for UKUDR, a design must also not be “commonplace in a qualifying country in the design field in question at the time of its creation”. In Neptune, Henry Carr J said (at paragraphs 59 and 60):

“59. In Ocular Sciences [1997] RPC 289 Laddie J explained that the commonplace exclusion applies to “any design which is trite, trivial, common-or-garden, hackneyed or of the type which would excite no peculiar attention in those in the relevant art”. The analysis must be conducted by reference to material “shown to be current in the thinking of designers in the field at the time of creation of the designs”, per Jacob LJ in Lambretta Clothing v Teddy Smith Ltd [2004] EWCA Civ 886; [2005] RPC 6 at [56].

60. Following the amendment to s.213(2), it is more difficult for the claimant to define the shape of a design at a higher level of abstraction than its physical manifestation in the relevant article. As explained by Arnold J in the Whitby case at [45], this makes it harder for the claimant to prove infringement, and also makes it harder for the defendant to prove that the design is commonplace. Nonetheless, the commonplace exclusion remains a useful cross-check on the breadth of a claim to infringement - the more generalised the definition of the design relied upon, the more likely it is to encompass designs which would “excite no peculiar attention in those in the relevant art.””

92. I was also referred to the useful summary of the task facing a defendant set out by HHJ Hacon in Action Storage Systems Limited v G-Force Europe and Anor [2016] EWHC 3151 (IPEC) at paragraph 37:

“(1) A defendant alleging that a design is commonplace should plead the significant features of the design as he contends them to be, the prior art relied on in which those features are said to be found and the date from which each cited item of prior art was available to designers in the relevant design field.

(2) Prior art which renders a design commonplace will not be obscure. The evidential burden rests on the defendant to show that it is not.

(3) A design will be commonplace if it is shown to have been current in the thinking of designers in the field in question at the time of creation of the design, see Lambretta Clothing Co Ltd v Teddy Smith (UK) Ltd [2005] RPC 6 at [56]. Another way of looking at this is that a commonplace design will be one which is trite, trivial, common-or-garden, hackneyed or of the type which would excite no particular attention in those in the relevant design field, see Ocular Sciences Ltd v Aspect Vision Care Ltd [1997] RPC 289, at p.429, approved in Farmers Build Ltd v Carier Bulk Materials Handling Ltd [1999] RPC 13, at pp.477 and 479. A third way of characterising a commonplace design is that it will be ready to hand, not matter that has to be hunted for and found at the last minute, see Ultraframe (UK) Ltd v Eurocell Building Plastics Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 761; [2005] RPC 36, at [60].

(4) The design field in question is that with which a notional designer of the article in issue is familiar, see Lambretta Clothing at [45].

(5) A design made up of features which individually are commonplace is not necessarily itself commonplace. A new combination of run-of-the-mill features may not be commonplace. See Ocular Sciences at p.429, approved by the Court of Appeal in Farmers Build at p.476 and in Ultraframe at [64].

(6) If the designer of the accused article has expended sufficient skill and labour to make his design original (in the copyright sense) over a single piece of commonplace prior art, he is liable also to have succeeded in creating a design that is not rendered commonplace by that prior art.”

Infringement

93. In relation to infringement, two connected issues require consideration:

i) What is meant by reproduction in section 226(2) of the CDPA?

ii) When is an article produced exactly or substantially to a design within the meaning of section 226(2) of the CDPA?

94. As section 226(2) of the CDPA makes clear, reproduction requires copying. Copying is not defined in the CDPA. The Defendants accepted that a causal connection is required, but submitted that that is not, of itself, sufficient. Rather, counsel for the Defendants submitted that copying is only established where (1) the earlier design is the only cause of the design of the defendant’s article; and (2) the defendant had not already independently conceived of the idea of a design with the majority of the features present in the earlier design before they came across the earlier design. I do not consider that this definition assists me: indeed, I consider it flies in the face of common sense, and conflates two separate but connected elements of section 226(2). To take the two parts of the proffered definition in turn: first, an infringing design can be copied from two earlier designs. Counsel for the Claimants gave the example of a top and a pair of trousers which are separate garments, but which a defendant reproduces, stitched together, to create a jumpsuit. Both the top and the trousers have been copied. The next question is whether the jumpsuit has been made substantially to the design of either the top or the trousers - but both have been copied. It would deprive the CDPA of any force if a copying defendant is excused because s/he copied from more than one source.

95. The second part of the Defendants’ proffered definition is also unhelpful, and is aimed squarely at what are said to be the facts of this case. In most cases, the allegation that the junior product was completely and meticulously designed in the head of its creator prior to seeing the allegedly copied design will be a question of proof, so it does not sit well within a definition of copying. It is also not something that can be independently verified: of course, if Ms Henderson had created a drawing or other record of her thoughts prior to her accessing third party designs, then that could suggest no copying. I add that the definition proposed by the Defendants gets more and more improbable the more complex the article. Many of the garments in issue in this case are not simple dresses. Many have striking and unusual features. It strains belief to suggest that a defendant could have designed all those features in her head, before going looking for third party examples that reproduce most if not all of the features. I therefore reject the Defendants’ definition of copying: this second element may be pertinent to the facts of a given case on the issue of proof, but it is not appropriate to include it in the definition of copying.

96. The Claimants’ counsel put copying like this:

“Our position is that a simple causal link is enough to establish copying. If the claimant’s design has contributed to the defendant’s creation of its design there is copying. Whether or not that amounts to infringement will depend on whether or not - assessed quantitatively and qualitatively - what has been reproduced is sufficient”.

97. I accept that definition as adequate for the purposes of this case.

98. Section 226(2) also requires that the allegedly infringing design be made “exactly or substantially” to the design. This encompasses both exact replicas, and also reproductions which, though not exact, nevertheless create an article that is “substantially” to the design. In Neptune, Henry Carr J said at paragraphs 49 to 53:

“49. The correct approach to considering whether an allegedly infringing article is produced exactly or substantially to the design was set out by Aldous J in C&H Engineering v F Klucznik & Sons Ltd (No.1) [1992] FSR 421 at p 428:

“Under section 226 there will only be infringement if the design is copied so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to the design. Thus, the test for infringement requires the alleged infringing article or articles be compared with the document or article embodying the design. Thereafter the court must decide whether copying took place and, if so, whether the alleged infringing article is made exactly to the design or substantially to that design. Whether or not the alleged infringing article is made substantially to the plaintiff’s design must be an objective test to be decided through the eyes of the person to whom the design is directed.”

50. Neptune submits that this approach is over-simplistic, and that guidance can be found by analogy to infringement by reproduction of a substantial part of a copyright work. It relies upon a well-known passage in Lord Hoffman’s speech in Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd v Marks & Spencer Plc [2003] 1 AC 551 at pp.559–560, which explains that for the purpose of assessing whether a substantial part has been reproduced in a copyright claim, the Court should consider whether the original skill and labour, which was the reason for conferring copyright protection, has been copied:

“The House of Lords decided in Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 WLR 273 that the question of substantiality is a matter of quality rather than quantity … But what quality is one looking for? That question, as it seems to me, must be answered by reference to the reason why the work is given copyright protection. In literary copyright, for example, copyright is conferred (irrespective of literary merit) upon an original literary work. It follows that the quality relevant for the purposes of substantiality is the literary originality of that which has been copied. In the case of an artistic work, it is the artistic originality of that which has been copied.”

51. Mr Cuddigan submits that, by parity of reasoning, protection is conferred upon designs because of the originality of their shapes and/or configurations. Where there is copying of ideas expressed in a design which, in their conjoined expression, have involved original design skill and labour, and/or are the expression of the intellectual creation of their author, the resulting article will be substantially made to the design.

52. However, an attempt to equate infringement of UK unregistered design right with infringement of copyright was specifically rejected by the Court of Appeal in Wooley v A Jewellers [2002] EWCA Civ 1119; [2003] FSR 15, where it was held at [19] that:

“19 … As Aldous J observed in the passage I have set out in the Klucznik case, there is a difference between an enquiry into whether the item copied forms a substantial part of the copyright work and an enquiry whether the whole design containing the element which has been copied is substantially the same design as that which enjoys design right protection. The enquiry which the judge carried out was that set out in paragraph 119 of his judgment. At no stage did the judge refer to the different test applicable to design right infringement. On that test, it may not be enough to copy a part, even a substantial part. Regard has to be had to the overall design which enjoys design right. Here the judge was diverted to certain difficult questions arising as to substantiality in copyright infringement which may have no relevance to design right infringement.”

53. In contrast to copyright, it is not an infringement of a UK unregistered design to reproduce “a substantial part” of a design. The importance of this distinction may be illustrated by the facts of the present case. Apart from the features which Neptune has excluded, it relies upon the entirety of each of the articles of furniture which is said to embody the designs in issue, and does not rely upon parts or combinations of parts of such articles. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the differences as well as the similarities between Chichester and Shaker products. It will not be enough to show that a particular feature or combination of features (which in a copyright claim might constitute a substantial part) has been copied. Nor will it be enough to show that Neptune’s key features have been copied, since those features, whether alone or in combination, have not been pleaded as a design right.”

99. I have adopted this approach in my analysis of whether the Defendants’ garments were “made exactly or substantially” to the Claimants’ designs.

100. Of course, it will be necessary to examine individually each of the 20 garment designs relevant for this trial. There were, however, some general issues that applied to all or many of the designs which it is convenient to discuss first.

101. The Defendants accepted that if all 20 designs in issue in this trial were created by the designers identified by the Claimants, then as employees of Sirens Design, Sirens Design was the first owner of any UKUDR and that any such rights had been validly assigned to the First Claimant. However, in their pleadings, the Defendants did not admit that all of the 20 designs were created by the designers identified by the Claimants.

102. Ms Douek gave evidence, unchallenged by the Defendants, that she created five of the 20 garments in issue. For the remaining 15 designs, the Claimants’ evidence was that of Connor Walker, who stated that the designs were created by the named designer. Counsel for the Defendants challenged this evidence, submitting that the Claimants had not satisfied the burden on them to establish that each of the 15 garments was designed by an employee of Sirens Design, or, indeed, the named individuals. The Defendants put forward no evidence to the contrary, and Connor Walker was not moved from her position in cross-examination. An explanation was provided as to why the designers other than Ms Douek had not been called to give evidence: Julia Kasper could not be contacted; Rheanna Donaldson has been in dispute with the Claimants over copyright; Justin Ruddle has set up in competition to the Claimants and Alcy Lynch is similarly no longer employed by Sirens Design.

103. In my judgment, the Defendants’ submission goes nowhere, and I reject it. I accept Connor Walker’s evidence that the 15 garments were designed as she said. It is not incumbent on a UKUDR claimant to provide testimony from the designer of each design, so long as it has evidence of who created the relevant design.

104. Counsel for the Defendants rightly pointed out that the Claimants bear the burden of proof on this issue: they must establish that their designs have not been copied from anyone else. But here, again, the Defendants submitted that the Claimants’ assertion in the pleadings (supported by a statement of truth) was insufficient to meet that burden. First, it was said that the House of CB designers may have copied from the garments shown on the mood boards. I have set out above my comments in relation to the controversy over the Claimants’ mood boards: it goes nowhere. Connor Walker and Ms Douek each gave evidence that Sirens Design designers did not copy the garments shown on the mood boards, from which they were not shifted under cross-examination. Second, counsel for the Defendants submitted that the Claimants should have called evidence from each designer. As I have set out above, an explanation was given for why that had not occurred and I accept that explanation. Additionally, although this was already a lengthy trial, it would have been made longer by the cross-examination of a further four witnesses. Third, counsel for the Defendants submitted that the garments were similar enough to the prior designs identified by the Defendants to raise an inference of copying. As I set out below, I do not consider any of the Claimants’ designs to be sufficiently close to the identified prior designs to give rise to an inference that they were copied. There was here what counsel for the Claimants described as an inconsistency in the Defendants’ position (and which the Defendants described as a squeeze). This was put in the following terms in counsel for the Defendants’ closing skeleton argument:

“We recognise that potential inconsistency, but let us be crystal clear: it is a squeeze on subsistence and infringement. [The Defendants] say the evidence is now clear that there is no material difference between the design process that [the Defendants] follow and the design process that [the Claimants] follow: both are following trends and casting very wide nets for inspiration. They create either physical or digital mood boards from which the trends are visible and from which the designers take ideas and even design features. If that is by its nature copying, then [the Claimants] have no design rights. If it is not copying, then rights do subsist in [the Claimants’] designs but [the Defendants] have not infringed them because they have not copied the designs and the right is sufficiently narrow that the Defendants’ designs fall outside them.”

105. The challenge with this submission is its opening assumption - that there is no material difference between the Claimants’ and the Respondents’ design processes. As will be apparent from this judgment, that position is inconsistent with my findings on the very different ways in which the House of CB and 17 of the Oh Polly garments in issue in this trial were designed. I therefore reject the squeeze on the facts of this case. Further, I reject the squeeze as a question of law, because the test for subsistence of UKUDR is different from the test for infringement. For subsistence, the design cannot have been slavishly copied (ie, it must be the result of the author’s own skill) and it cannot be commonplace (trite, hackneyed etc). The test for infringement is different - the infringing design must have been copied, and it must be made exactly or substantially to the claimed design. I can well understand that a squeeze exists in CUDR, where the infringement test is the flipside of the validity test, but I do not interpret UKUDR as producing a squeeze of that nature.

106. A further point was made that earlier House of CB garments not in issue in these proceedings had been copied from third party designs (I mention above that some were copied from designs by Hervé Léger). Connor Walker owned up to this - but said that any copying stopped when House of CB employed its own designers to design original garments. Dr Branney put together a schedule (which was filed as part of his reply evidence) comparing House of CB garments with third party garments: I was asked to draw the conclusion that if House of CB had copied those designs, I should question whether the 20 pleaded designs in this case were original (in the copyright sense). Connor Walker gave sworn evidence that House of CB’s design strategy had changed some years earlier, and she was not shaken on that position in cross-examination. I therefore reject this submission.

107. The Defendants have provided prior designs against which I am asked to assess originality in the copyright sense, and commonplaceness. I set out below my conclusions in relation to each garment and each prior design. But I do not consider that there is an overall pleading point, evidentiary burden point, disclosure point or squeeze that renders the Claimants’ designs unoriginal in the copyright sense, or commonplace.

108. Significant energy was exerted pre-trial in relation to the 101 prior designs that were said to show that the Claimants’ 20 pleaded designs were commonplace. However, in his closing skeleton argument, counsel for the Defendants dealt with this issue in half a sentence. The rest of that sentence read:

“…but if the court holds that none of the [Claimants’] designs is commonplace over any of the prior art, nonetheless, [the Defendants’] reliance on that prior art in support of their case on commonplace is a useful cross-check on the breadth of [the Claimants’] claim to infringement.”

109. In his oral closing submissions, counsel for the Defendants said this:

“The consideration of originality and commonplace in the context of UKUDR frames the infringement analysis and that has always been our primary goal.”

110. Counsel for the Claimants rejected those statements on the basis that they do not accurately describe the law. I have rejected above the notion of a squeeze on both the facts of this case, and on the law. I have found (below) that none of the Claimants’ designs lacks originality (in the copyright sense) or was commonplace on the basis of the prior designs before the court. In most cases, the prior designs pleaded (on both issues) were very different indeed from the Claimants’ designs, and the pleaded case of lack of originality (in the copyright sense) seemed to me to be hopeless. Similarly, the garments submitted to show that the Claimants’ designs were commonplace were often very different indeed and it struck me as odd that many of these were pleaded in the first place.

111. Because I have found on the basis of the garments pleaded that they do not invalidate the Claimants’ UKUDR, I do not need to decide whether the prior designs were disclosed at the time pleaded by the Defendants and/or how well they were known. I simply record here that it was the Claimants’ position that it could not verify many of the disclosures that were relied on, and that none of the pleaded prior designs was very well-known among designers or customers at the relevant times.

112. I start with the 17 garments before me which the Defendants plead were designed by Ms Henderson.

113. The Defendants now admit that a House of CB or Mistress Rocks garment was referred to in the design process of 9 of the 20 garments in issue in this trial. However, the Defendants submitted that in every case other than C35:

“there has not been copying either because the idea for the garment was conceived before the House of CB / Mistress Rocks garment was referred to or one or more other garments were also referred in the process, or both.”

114. As set out above, I have rejected both these arguments on definitional bases. I also reject the former on the facts before me: as set out above, the only evidence before the Court that the “idea” for the garment was already conceived is that given by Ms Henderson herself, and I have rejected her uncorroborated evidence.

115. By way of example only, take D2. Ms Henderson found a picture of C2 on social media and took a screen shot. That screen shot was uploaded to Trello for the Defendants’ manufacturer to work from. There were no other drawings, patterns or plans. There was a third party garment also shown on the Trello records, but, as I have said, copying more than one design is still copying.

116. In relation to the other eleven garments where the Defendants did not admit referencing one of the Claimants’ garments, the Claimants’ position was that I should infer copying on the balance of probabilities because of:

i) The similarities between the designs in issue suggested that copying had taken place;

ii) Ms Henderson’s approach to design - that is, identifying images of garments that she liked and providing these to the factory to be reproduced;

iii) The incomplete nature of the Trello records and the likelihood that Ms Henderson passed images directly to the manufacturers; and

iv) The likelihood that the House of CB garment alleged to have been copied existed in Ms Henderson’s archive.

117. I discuss the first of these in my analysis of each of the garments, set out below. However, on the facts of this case, absent striking closeness between the designs in relation to features that were not well known, it does not seem to me that the remaining three points put forward by the Claimants are sufficient to prove copying, or to give rise to a presumption which the Defendants are required to rebut. Further, in nearly all the cases where a House of CB/Mistress Rocks garment was not referred to in the design process, there is an identified third party garment which, from the similarity of the garments and from the Trello records, appears to be the basis for the Defendants’ design. That is entirely consistent with my findings in relation to Ms Henderson’s “design process” - only here, instead of copying one of the Claimants’ garments, she has copied a third party garment. That does not necessarily mean that the Claimants’ garment was not also copied, of course, but in the absence of any evidence at all to support the copying of particular garments of the Claimants (including, for example, striking similarities between unusual aspects of the Claimants’ designs), it seems to me most likely that the situation is better explained by the Defendants having copied a third party garment, as opposed to the more roundabout route proposed by counsel for the Claimants.