Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Court of Justice of the European Communities (including Court of First Instance Decisions)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Court of Justice of the European Communities (including Court of First Instance Decisions) >> H&M Hennes & Mauritz BV & Co KG (Community design - Invalidity proceedings - Registered Community design representing handbags) [2015] EUECJ T-525/13 (10 September 2015)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/EUECJ/2015/T52513.html

Cite as: [2015] EUECJ T-525/13, EU:T:2015:617, ECLI:EU:T:2015:617

[New search] [Contents list] [Help]

JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

10 September 2015 (*)

(Community design - Invalidity proceedings - Registered Community design representing handbags - Earlier design - Ground for invalidity - Individual character - Article 6 of Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 - Obligation to state reasons)

In Case T-525/13,

H&M Hennes & Mauritz BV & Co. KG, established in Hamburg (Germany), represented by H. Hartwig and A. von Mühlendahl, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Yves Saint Laurent SAS, established in Paris (France), represented by N. Decker, lawyer,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 8 July 2013 (Case R 207/2012-3), relating to invalidity proceedings between H&M Hennes & Mauritz BV & Co. KG and Yves Saint Laurent SAS,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber),

composed of S. Frimodt Nielsen, President, F. Dehousse and A.M. Collins (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 30 September 2013,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 20 January 2014,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Court Registry on 24 January 2014,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge-Rapporteur, to rule on the action without an oral procedure pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court of 2 May 1991,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 30 October 2006, the intervener, Yves Saint Laurent SAS, filed an application for registration of a Community design (‘the contested design’) with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (OJ 2002 L 3, p. 1).

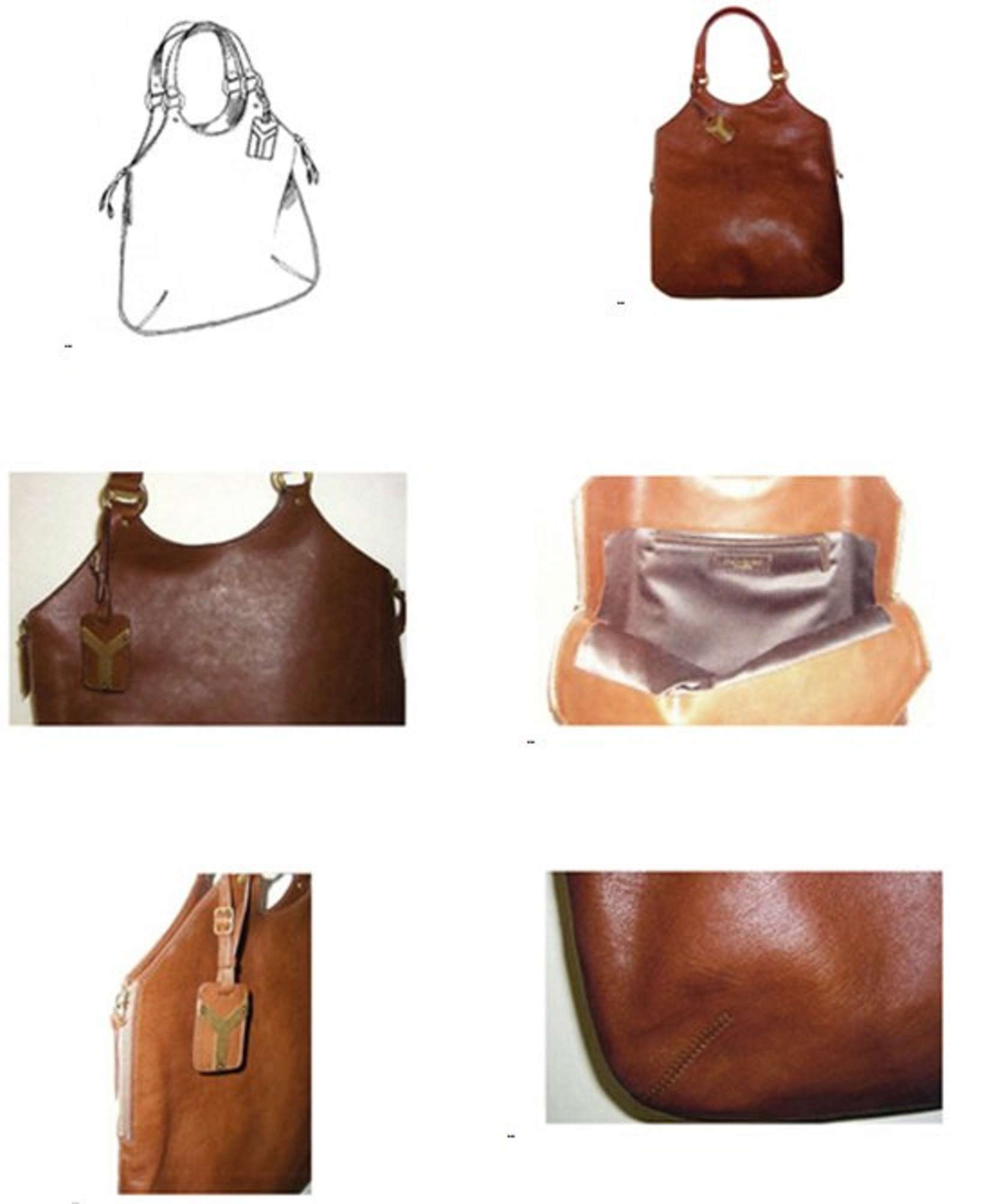

2 The contested design, which is intended to be applied to ‘handbags’ in Class 03-01 of the Locarno Agreement Establishing an International Classification for Industrial Designs of 8 October 1968, as amended, is represented according to six views as follows:

3 The contested design was registered under the number 613294-0001 and published in Community Designs Bulletin No 135/2006 of 28 November 2006.

4 On 3 April 2009, the applicant, H&M Hennes & Mauritz BV & Co. KG, filed with OHIM an application for a declaration of invalidity in respect of the contested design, based on Articles 4 to 9 of Regulation No 6/2002 and on Article 25(1)(c) to (f) or (g) of that regulation. In its application for a declaration of invalidity, the applicant confined itself to claiming that the contested design had no individual character within the meaning of Article 6 of that regulation.

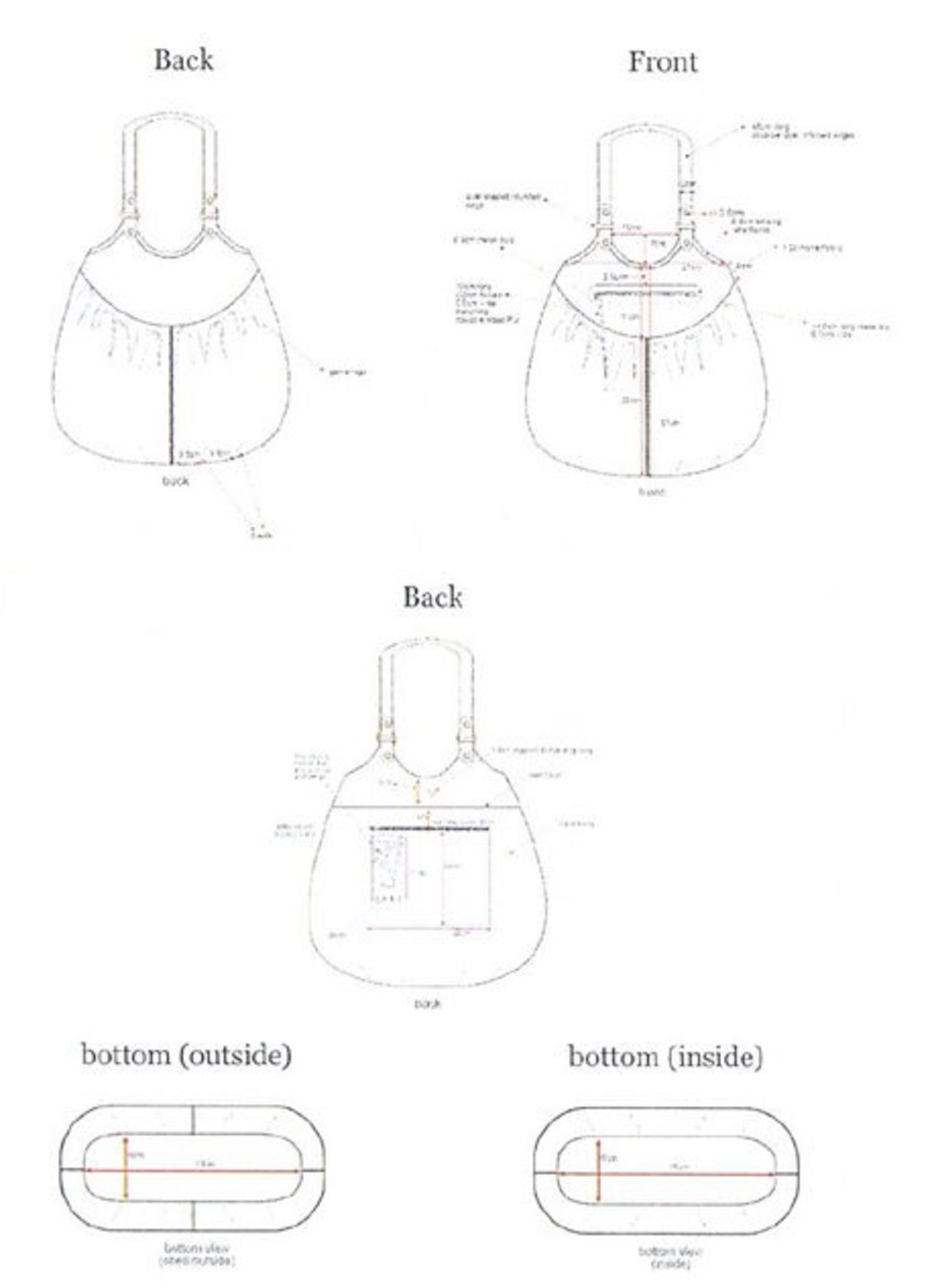

5 In support of its application for a declaration of invalidity, the intervener invoked, in order to substantiate the alleged lack of individual character of the contested design, the earlier design reproduced below:

6 By decision of 4 November 2011, the Cancellation Division rejected that application for a declaration of invalidity.

7 On 25 January 2012, the applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM, pursuant to Articles 55 to 60 of Regulation No 6/2002, against the decision of the Cancellation Division.

8 By decision of 8 July 2013 (‘the contested decision’), the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. After finding that the documents submitted by the applicant were capable of proving that the handbag which was the subject-matter of the earlier design had been made available to the public, the Board of Appeal examined the individual character of the contested design. It defined the informed user of that design as an informed woman, who was interested, as a possible user, in handbags. According to the Board of Appeal, the two designs at issue had features in common, in particular their upper contours and their handles in the form of straps attached to the body of the bags by a system of rings reinforced by rivets, but the differences as regards the shape, structure and surface finish played a decisive role in the overall impression produced by those goods. In that regard, the Board of Appeal found that the degree of freedom of the designer was high, but that, in the present case, it did not, from the point of view of the informed user, cancel out the significant differences in shape, structure and surface finish which differentiated the two bags.

Forms of order sought

9 The applicant claims that the Court should:

- annul the contested decision;

- declare the contested design invalid;

- order the intervener to pay the costs, including those incurred by the applicant before the Board of Appeal.

10 OHIM contends that the Court should:

- dismiss the action;

- order the applicant to pay the costs.

11 The intervener contends that the Court should:

- reject Annex A.6 to the application as inadmissible;

- dismiss the action;

- confirm the contested decision;

- declare the contested design valid;

- order the applicant to pay the costs, including those incurred by the intervener before OHIM.

Law

12 In support of the action, the applicant relies, in essence, on a single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002, which is divided into two parts. By the first part, it submits that it was erroneously concluded, and without sufficient reasons being given, in the contested decision that the high degree of freedom of the designer did not have any impact on the finding that the designs at issue produced a different overall impression on the informed user. By the second part, it claims that it was erroneously concluded in the contested decision, even though it was accepted that the designer had a high degree of freedom, that the differences between the designs at issue were significant enough to create a different overall impression.

13 In the context of the first part of the single plea, the applicant claims that the statement of reasons for the contested decision is insufficient. The Court deems it appropriate to examine that claim separately before analysing the arguments on the substance.

14 OHIM and the intervener dispute the applicant’s arguments.

The claim that the statement of reasons is insufficient

15 It must be borne in mind that, under Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002, decisions of OHIM must state the reasons on which they are based. That duty to state reasons has the same scope as that under Article 296 TFEU, pursuant to which the reasoning of the author of the act must be shown clearly and unequivocally. That duty has two purposes: to allow interested parties to know the justification for the measure taken so as to enable them to protect their rights and to enable the Courts of the European Union to exercise their power to review the legality of the decision. The Boards of Appeal cannot, however, be required to provide an account that follows exhaustively and one by one all the lines of reasoning articulated by the parties before them. The reasoning may therefore be implicit, on condition that it enables the persons concerned to know the reasons for the Board of Appeal’s decision and provides the competent Court with sufficient material for it to exercise its review (see judgment of 25 April 2013 in Bell & Ross v OHIM - KIN (Wristwatch case), T-80/10, EU:T:2013:214, paragraph 37 and the case-law cited).

16 It must also be borne in mind that the duty to state reasons in decisions is an essential procedural requirement which must be distinguished from the question whether the reasoning is well founded, which is concerned with the substantive legality of the measure at issue. The reasoning of a decision consists in a formal statement of the grounds on which that decision is based. If those grounds contain errors, those errors will affect the substantive legality of the decision, but not the statement of reasons in it, which may be adequate even though it sets out reasons which are incorrect (see judgment in Wristwatch case, cited in paragraph 15 above, EU:T:2013:214, paragraph 38 and the case-law cited).

17 In the present case, it is apparent from the contested decision that the Board of Appeal found that the differences between the designs at issue were so marked that the degree of freedom of the designer could not affect the finding as regards the different overall impressions produced by those designs. First of all, the Board of Appeal found, in paragraph 42 of the contested decision, that ‘the two bag designs [at issue] [did] indeed have features in common[,] but [that], for the reasons that [had] already been stated [in paragraphs 30 to 34], the differences as regards the shape, structure and surface finish of the bags [were] those that [had] a decisive influence on the overall impression from the point of view of the informed user’. Next, it pointed out, in paragraph 44 of the contested decision, that the degree of freedom of the designer was a factor which had to be taken into account when assessing the individual character of the design in accordance with Article 6(2) of Regulation No 6/2002 and served to reinforce or moderate the user’s perception in that regard. Lastly, it acknowledged, in paragraph 45 of that decision, that the designer’s degree of freedom, in the context of fashion items like handbags, was high, before stating that ‘that acknowledgment [could not] automatically imply, contrary to what the [applicant] seem[ed] to state, that the [contested] handbag [design] produced[ed] the same overall impression as the handbag which [was] the subject-matter of the earlier design’. It stated that ‘the starting point for the assessment of that overall impression, pursuant to Article 6(1) of [Regulation No 6/2002, was] the informed user’, that, ‘in the present case, that high degree of freedom [would] not in any way cancel out, from the point of view of the informed user, the significant differences in shape, structure and surface finish which differentiate[d] the two bags’ and that, ‘[i]n the case in point, therefore, the high degree of freedom of the designer [was] in no way incompatible … with the finding that the two bags produce[d] a different overall impression’.

18 It follows that, contrary to what the applicant claims, the Board of Appeal set out in a sufficiently clear and unequivocal manner the reasoning by which it found that, in the present case, the high degree of freedom of the designer did not have any impact on the finding that the designs at issue produced a different overall impression on the informed user. The claim that the statement of reasons is insufficient must therefore be rejected as unfounded.

The merits

19 As both parts of the single plea in law concern alleged errors made by the Board of Appeal in the application of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002 to the present case, the Court considers that it is appropriate to examine them together.

20 Under Article 6(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, a registered Community design is to be considered to have individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has been made available to the public before the date of filing the application for registration or, if a priority is claimed, the date of priority. Article 6(2) of that regulation states that, in assessing individual character, the degree of freedom of the designer in developing the design is to be taken into consideration.

21 It is apparent from recital 14 in the preamble to Regulation No 6/2002 that, when assessing whether a design has individual character, account should be taken of the nature of the product to which the design is applied or in which it is incorporated, and in particular the industrial sector to which it belongs and the degree of freedom of the designer in developing the design. In the present case, the contested design, like the earlier design, represents a handbag.

22 Furthermore, it is apparent from Article 6(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 and settled case-law that the assessment of whether a design has individual character is determined by the overall impression that it produces on the informed user (see judgment of 25 October 2013 in Merlin and Others v OHIM - Dusyma (Game), T-231/10, EU:T:2013:560, paragraph 28 and the case-law cited).

23 In the present case, the Board of Appeal defined the concept of the informed user, in relation to whom the individual character of the contested design must be assessed, as an informed woman who is interested, as a possible user, in handbags.

24 As regards the level of attention of the informed user, it must be borne in mind, in line with what the Board of Appeal stated, that, according to the case-law, the concept of the informed user may be understood as referring, not to a user of average attention, but to a particularly observant one, either because of his personal experience or his extensive knowledge of the sector in question (judgment of 20 October 2011 in PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic, C-281/10 P, ECR, EU:C:2011:679, paragraph 53).

25 It is also apparent from the case-law that, although the informed user is not the well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect average consumer who normally perceives a design as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details, he is also not an expert or specialist capable of observing in detail the minimal differences that may exist between the designs at issue. Thus, the qualifier ‘informed’ suggests that, without being a designer or a technical expert, the user knows the various designs which exist in the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include, and, as a result of his interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them (judgment in PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic, cited in paragraph 24 above, EU:C:2011:679, paragraph 59).

26 The Board of Appeal found that the informed user in the present case was neither an average purchaser of handbags nor a particularly attentive expert, but someone in between who is familiar with the product in accordance with the level of attention established by the case-law cited in paragraphs 24 and 25 above.

27 The applicant does not dispute the Board of Appeal’s findings regarding the definition and the level of attention of the informed user, which must be confirmed.

28 As regards the degree of freedom of the designer of a design, it is apparent from the case-law that that is determined, inter alia, by the constraints of the features imposed by the technical function of the product or an element thereof, or by statutory requirements applicable to the product. Those constraints result in a standardisation of certain features, which will thus be common to the designs applied to the product concerned (judgment of 9 September 2011 in Kwang Yang Motor v OHIM - Honda Giken Kogyo (Internal combustion engine), T-11/08, EU:T:2011:447, paragraph 32, and judgment in Wristwatch case, cited in paragraph 15 above, EU:T:2013:214, paragraph 112).

29 Therefore, the greater the designer’s freedom in developing a design, the less likely it is that minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce different overall impressions on an informed user. Conversely, the more the designer’s freedom in developing a design is restricted, the more likely it is that minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce different overall impressions on an informed user. Consequently, if the designer enjoys a high degree of freedom in developing a design, that reinforces the conclusion that designs that do not have significant differences produce the same overall impression on an informed user (judgments in Internal combustion engine, cited in paragraph 28 above, EU:T:2011:447, paragraph 33, and Wristwatch case, cited in paragraph 15 above, EU:T:2013:214, paragraph 113).

30 In the present case, the Board of Appeal correctly found that, in the context of fashion items like handbags, the designer’s degree of freedom was high. Moreover, the applicant does not contest that assessment. However, it submits, in essence, that the Board of Appeal erred inasmuch as the ‘freedom of the designer’ test should have been an integral part of the analysis of the individual character of the contested design and that the Board of Appeal inverted the steps involved in that analysis. Accordingly, the applicant maintains that the Board of Appeal’s approach of, first, comparing the two designs at issue in order to conclude that they did not produce the same overall impression on the informed user and, second, examining the argument relating to the freedom of the designer, is incorrect. Furthermore, it takes the view that the differences between the designs at issue are not significant enough to produce a different overall impression on the informed user.

31 First, it must be stated that a ‘two-step test’, such as advocated by the applicant, is not required by either the applicable legislation or the case-law.

32 The text of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002, concerning the assessment of individual character, lays down, in paragraph 1 thereof, the criterion of the overall impression produced by the designs at issue and states, in paragraph 2, that the degree of freedom of the designer must be taken into consideration for those purposes (see paragraph 20 above). It is apparent from those provisions, and in particular from Article 6(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, that the assessment of the individual character of a Community design is the result, in essence, of a four-stage examination. That examination consists in deciding upon, first, the sector to which the products in which the design is intended to be incorporated or to which it is intended to be applied belong; second, the informed user of those products in accordance with their purpose and, with reference to that informed user, the degree of awareness of the prior art and the level of attention in the comparison, direct if possible, of the designs; third, the designer’s degree of freedom in developing his design; and, fourth, the outcome of the comparison of the designs at issue, taking into account the sector in question, the designer’s degree of freedom and the overall impressions produced on the informed user by the contested design and by any earlier design which has been made available to the public (see, to that effect, judgment of 7 November 2013 in Budziewska v OHIM - Puma (Bounding feline), T-666/11, EU:T:2013:584, paragraph 21 and the case-law cited).

33 As is apparent from the case-law and from the case-law cited in paragraph 29 above and referred to by the applicant itself, the factor relating to the designer’s degree of freedom may ‘reinforce’ (or, a contrario, moderate) the conclusion as regards the overall impression produced by each design at issue. It is not apparent either from the alleged pattern which the applicant identifies in the case-law or even from the extract from the judgment of the Bundesgerichtshof (Federal Court of Justice, Germany) reproduced in paragraph 29 of the application that the assessment of the designer’s degree of freedom constitutes a preliminary and abstract step in the comparison of the overall impression produced by each design at issue.

34 It is also necessary to reject all of the claims relating to paragraph 44 of the contested decision that the applicant puts forward in paragraph 33 of the application. Those claims are based, in part, on a misreading of that paragraph and are, in any event, unsubstantiated. The Board of Appeal stated the following in paragraph 44 of the contested decision:

‘As regards the degree of freedom of the designer, the Board notes that it is indeed a factor which must be taken into consideration pursuant to Article 6(2) of [Regulation No 6/2002] when assessing individual character. … However, no “reciprocity” exists either in itself or automatically. In the judgment [in Internal combustion engine, cited in paragraph 28 above, EU:T:2011:447] which the [applicant] cites in support of its argument, the General Court stated that if the designer enjoys a high degree of freedom in developing a design, that “reinforces” the conclusion that designs that do not have significant differences produce the same overall impression on an informed user … The degree of freedom cannot therefore, on its own, give rise to an outcome as regards the assessment of individual character. That assessment must be based on the overall impression as Article 6(1) of [Regulation No 6/2002] states. Although it is certainly true, therefore, that the degree of freedom of the designer must be taken into consideration, the starting point for the assessment of the individual character of a design must, in any event, be the perception of the informed user. In other words, the degree of freedom of the designer must serve to temper the judgment - in the sense, as the General Court states, of “reinforcing” it or, on the contrary, of moderating it - arrived at on the basis of the perception of the informed user. The degree of freedom of the designer is therefore not, contrary to what the [applicant] seems to state, the starting point for the assessment of individual character but, as Article 6(2) of [Regulation No 6/2002] states, an aspect which must be “taken into consideration” when analysing the perception of the informed user.’

35 The Board of Appeal did not err in stating that the factor relating to the freedom of the designer could not on its own determine the assessment of the individual character of a design, but that it was, however, a factor which had to be taken into consideration in that assessment. Consequently, it correctly found that that factor was a factor which made it possible to moderate the assessment of the individual character of the contested design, rather than an independent factor which determined how different two designs have to be for one of them to have individual character.

36 Second, as regards the comparison of the overall impressions produced by the contested design and by the earlier design, the Board of Appeal stated, in paragraph 30 of the contested decision, that they differed as to three features which decisively influenced their overall visual appearance, namely the overall shape, structure and surface finish of the bag.

37 First of all, it pointed out that the body of the contested design had a perceptibly rectangular shape, on account of the presence of three straight lines that marked the sides and the base of the bag, which gave the impression of a relatively angular object. By contrast, the body of the earlier design had, according to the Board of Appeal, curved sides and a curved base and its silhouette was dominated by an impression of roundness. Second, the Board of Appeal took the view that the body of the contested design looks as if it is made from a single piece of leather without any visible division or seams except for on a short length at the lower corners. By contrast, the front and back of the earlier design were, according to the Board of Appeal, divided into three sections by seams, namely a curved upper section delimited by a collar and two lower sections of equal size delimited by a vertical seam. Third, the Board of Appeal stated that the surface finish of the contested design was totally smooth, apart from two faint seams at the lower corners. By contrast, the surface of the earlier design was, according to the Board of Appeal, covered with pronounced and raised decorative motifs, namely a collar edged with gatherings in the upper part of the bag, a vertical seam dividing the bag into two sections and pleats at the bottom of the bag. In respect of each of those three factors, the Board of Appeal concluded that the differences between the designs at issue were significant and therefore such as to markedly influence the overall impression of the informed user. In the case of the contested design, the Board of Appeal found that the impression produced would be that of a bag design characterised by classic lines and a formal simplicity whereas, in the case of the earlier design, the impression would be that of a more ‘worked’ bag, characterised by curves, the surface of which is adorned with ornamental motifs.

38 As regards the features that are common to the two designs at issue, namely their upper contour and the presence of a handle in the form of a strap or straps attached to the body by a system of rings reinforced by rivets, the Board of Appeal took the view that they did not suffice to confer on them, in the eyes of an informed user, the same overall impression. It stated in particular that the way in which those rings were used in the two bags was very different in that they were very visible and let light through in the contested design, which was not the case with regard to the earlier design, this being a detail which would be obvious to the informed user.

39 In that regard, it must be borne in mind that the assessment of the overall impression produced by a design on the informed user includes the manner in which the product represented by that design is used (see judgment of 21 November 2013 in El Hogar Perfecto del Siglo XXI v OHIM - Wenf International Advisers (Corkscrew), T-337/12, ECR, EU:T:2013:601, paragraph 46 and the case-law cited). In the present case, it must be pointed out that the straps and the handle of the designs at issue manifestly lend themselves to different uses inasmuch as the contested design represents a bag to be carried solely by hand, whereas the earlier design represents a bag to be carried on the shoulder.

40 In that context and in the light of the foregoing considerations, it must be held that the differences between the designs at issue are significant and that the similarities between them are insignificant in the overall impression which they produce. Consequently, the Board of Appeal’s assessment must be confirmed inasmuch as it found that the contested design produced an overall impression on the informed user which was different from that produced by the earlier design.

41 The foregoing assessment cannot be called into question by the applicant’s claims.

42 By a first claim, alleging that there was no contextual analysis of the features of the bags at issue, the applicant submits that the Board of Appeal did not examine the similarities between the designs at issue, identify the differences between them or analyse whether those differences or similarities were minor, average or major, in order, having regard to the high degree of freedom of the designer, to draw conclusions in respect of the overall impression produced. That claim must be rejected as having no factual basis on account of the considerations set out in paragraphs 36 to 38 above, which describe the progressive stages of the analysis carried out by the Board of Appeal in paragraphs 30 to 42 of the contested decision.

43 By a second claim, the applicant submits that the differences between the designs at issue, while not insignificant, are not, however, significant enough to create a different overall impression on the informed user. According to the applicant, the contested decision is silent in that respect and disregards the criteria established by the case-law.

44 It must be stated that that claim, assuming that it is admissible, is wholly unfounded. First, it is clear from paragraphs 37 to 42 of the contested decision that the Board of Appeal carefully examined the elements common to both of the designs at issue before concluding that the differences between them prevailed in the overall impression produced, a finding which has been confirmed by the Court (see paragraph 40 above). Second, as is apparent from paragraph 42 above, the Board of Appeal correctly applied the criteria established by the case-law in the present case.

45 The action must therefore be dismissed in its entirety, without it being necessary to rule on the admissibility of the third head of claim submitted by the applicant and the admissibility of the third and fourth heads of claim submitted by the intervener, as well as the admissibility of an annex to the application, which the intervener calls into question.

Costs

46 Under Article 134(1) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

47 Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

48 In addition, the intervener has contended that the applicant should be ordered to pay the costs which it incurred in the proceedings before OHIM. In that regard, it must be borne in mind that, under Article 190(2) of the Rules of Procedure, costs necessarily incurred by the parties for the purposes of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal are to be regarded as recoverable costs. However, that is not the case with regard to the costs incurred for the purposes of proceedings before the Cancellation Division. Accordingly, the intervener’s request that the applicant, having been unsuccessful, be ordered to pay the costs of the administrative proceedings before OHIM can be allowed only as regards the costs necessarily incurred by the intervener for the purposes of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal (see judgment in Wristwatch case, cited in paragraph 15 above, EU:T:2013:214, paragraph 164 and the case-law cited).

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders H&M Hennes & Mauritz BV & Co. KG to pay the costs, including those incurred by Yves Saint Laurent SAS in the course of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM).

Frimodt Nielsen | Dehousse | Collins |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 10 September 2015.

[Signatures]

* Language of the case: English.