Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions >> SS v The Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWHC 1402 (Admin) (05 June 2019)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2019/1402.html

Cite as: [2019] EWHC 1402 (Admin)

[New search] [Printable RTF version] [Help]

ADMINISTRATIVE COURT

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| SS |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| The Secretary of State for the Home Department |

Defendant |

____________________

Miss C Patry and Mr R Evans (instructed by The Treasury Solicitor) for the Defendant

Hearing date: 14th May 2019

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- By his decision letter dated 14 November 2018, the defendant concluded that the claimant's submissions did not amount to a fresh claim(s) because taken together with the previously considered material they did not create a realistic prospect of success and so the claimant was liable to enforced removal. He was removed on to Iraq on 18 November 2018.

- In particular and at the heart of this case the defendant, in making that decision, concluded that the claimant could obtain a Civil Status Identity Card ("CSID") in Baghdad and was therefore not at risk of any Article 3 ill-treatment.

- The defendant reached that conclusion in reliance upon his Country Policy and Information Note (Iraq: internal relocation, civil documentation and returns) ("CPIN") which he says is based on cogent and credible fresh evidence to the effect that the claimant could obtain a CSID on return to Bagdad.

- It is the claimant's case that the Country Guidance ("CG") cases establish that there was a real risk that the claimant would not be able to obtain a CSID and without one he would be at risk of Article 3 ill-treatment and so the November submissions created a realistic prospect of success and amounted to a fresh claim/fresh claims pursuant to the Immigration Rules.

- The issue is therefore whether the defendant's decision(s) to refuse to accept the claimant's further representations as amounting to a fresh claim were unreasonable because the claimant had a reasonable prospect of success in arguing before a First-tier Tribunal ("FTT") Judge that the CG should be followed and the CPIN does not amount to strong grounds and clear and cogent evidence justifying departure from it.

- The claimant is an Iraqi national born on 20 May 1985. He claimed asylum in the UK having arrived clandestinely when he was aged 17. That was refused but he was granted exceptional leave to remain and then on 22 May 2007 he was granted indefinite leave to remain. Applications for naturalisation were refused in January and May 2009.

- On 27 March 2009 the claimant was convicted of serious assault and robbery and sentenced to 5 years' imprisonment. A liability to deportation notice was served on 20 September 2011. The claimant's appeal against that was unsuccessful and he became appeal rights exhausted on 15 March 2013. The claimant failed to comply with reporting restrictions and was treated as an absconder on 3 July 2013. On 14 October 2015 he was encountered by Border Force attempting to enter the UK at Dunkerque. He was refused entry but did later re-enter and was recalled to prison on 19 December 2017.

- The claimant made an Article 8 claim which was refused on 2 August 2018 and on 6 August 2018 he was transferred to detention under immigration powers. His application for stateless leave was refused. On 1 November 2018 he was served with a notice of removal window. He made a judicial review claim on 6 November applying for a stay on removal. Permission and a stay on removal were refused by Upper Tribunal Judge Blum on 7 November. Further submissions were lodged on 9 November and rejected on 14 November. Also, on 14 November further submissions were lodged and rejected on 16 November. Again, on 16 November further submissions were lodged. Those submissions were rejected on 18 November. The claimant's application for a stay on removal was refused by Kerr J following an out of hours application and the claimant was removed to Iraq.

- The current judicial review proceedings were served on 10 December 2018 and permission was refused on the papers by Lang J on 21 January 2019. Following a renewal notice, permission was granted by Michael Kent QC (sitting as a deputy High Court Judge) following an oral renewal hearing. Michael Kent QC (see order in the main bundle ("MB") at p490) further ordered that the listing of this substantive hearing be expedited.

- I was told that there is a relevant CG case listed for a 5-day hearing on 24 June 2019 which will address the issue of obtaining a CSID among other matters. The defendant "floated" the idea of adjourning this case until the outcome of that one. The claimant's counsel resisted that on the basis that it may be 5 or 6 months before the decision in that case is promulgated, the claimant is in Baghdad at risk of ill-treatment and this hearing was expedited for that reason. In the circumstances, where the defendant was neutral on the issue and the claimant objected, I concluded there would be too great a delay for the claimant if the case was adjourned.

- In his Grounds the claimant raises challenges to the defendant's "removal window policy" contending that it operated in an unfair manner in this case. In the Reply to the defendant's Detailed Grounds it is set out that Walker J on 14 March in R (Medical Justice) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (CO/543/2019) ordered that the removal window policy be suspended. I was told that there is to be a hearing listed on 19/20 June for this court to consider that policy. I mooted the possibility of the sense in awaiting that outcome. However, on behalf of the claimant, Mr Lee made it clear that this case is not intended to be a full-blown attack on that policy. The claimant relies on a public law error which ties in with the fresh claim argument. The claimant's skeleton argument does not address the point substantially and so it seemed to be sensible, in light of the order for expedition, to hear this claim.

- The order of Michael Kent QC provided that the defendant was to serve evidence by 14 March 2019. The defendant made two applications to me to admit witness evidence out of time. The first dated 17 April 2019 (in the Supplementary Bundle ("SB") at p1) relates to the first statement of Diane Drew which sets out the circumstances in which the CPIN information relevant to this case came into being. It annexes copies of the emails/letters quoted in the CPIN. The application was not opposed. It is relied upon by the defendant to show the defendant's state of mind/knowledge at the time of the decision. The claimant accepts that he had sought some of the information in that statement. In light of the parties' positions I granted that application.

- The defendant made a second application in respect of Diane Drew's second witness statement. That application is dated 10 May. For the reasons given in the ruling I made at the time (which is annexed hereto) I refused that application.

- As set out above the claimant made 3 lots of further submissions following the refusal by Upper Tribunal Judge Blum to grant permission to bring judicial review proceedings and stay removal. The first (MB p54) were lodged by his then solicitors on 9 November 2018 and then two sets dated 14 November 2018 (MB p87) and 16 November 2018 (MB p199) were lodged by his current solicitors. Each was rejected by the defendant. The lack of a CSID card was raised in the submissions of 9 November, detailed further in the subsequent submissions and sequentially rejected. For the purposes of this judgment it is unnecessary to set out all the details of each of those six pieces of correspondence. By his submissions, the claimant relies on the Country Guidance as evidence of the contention that without a CSID he would face the risk of Article 3 ill-treatment, as evidence of the real risk that he would not be able to obtain a CSID and further the unlikelihood of his being able to obtain one within a reasonable timeframe. I can treat the three sets of submissions as one.

- It was further submitted on behalf of the claimant that he has particular characteristics which mean that if the CG was taken into account an appeal would have reasonable prospects of success. Those characteristics being that: he did not speak much Arabic; he is a Sunni Muslim and a Kurd; his home area of Mosul is in a contested area being in Ninewah governate; he has been in the UK for 16 years and has no familial support in Baghdad and has never lived there; he did not possess a current or expired Iraqi passport and in the event that he was returned on a laissez-passer he was undocumented; and he would be returned to Baghdad.

- The defendant agrees that his letter of 14 November 2018 at MB p74 is the substantive letter and deals with all the matters upon which the defendant's decision was made and upon which he relies. I therefore only need to refer to the contents of that decision.

- The defendant considered the submissions previously considered (relating to internal armed conflict, reintegration and Article 8) but rejected them for the same reasons as given by the IAC and the reasons given in the decision dated 2 August 2018 and the full consideration given to the submissions therein. At MB p79 the defendant considered the "Submissions that have not previously been considered but which do not create a realistic prospect of success". In summary under this heading, in reliance on the CPIN, the defendant did not accept the claimant's submissions that he would be unable to obtain a CSID card and further, the defendant did not accept that the claimant would become destitute on return because he would be able to obtain a CSID card. At paragraph 34 on p83(MB) the defendant sets out

- At paragraph 51 p84(MB) the defendant therefore sets out that the claimant's submissions do not meet the requirements of paragraph 353 of the Immigration Rules and do not amount to a fresh claim. Paragraph 353 provides:

- There is no dispute between the parties that paragraph 353 above sets out the criteria for a fresh claim and is the relevant test for me to consider here, namely whether the new submissions taken together with the previously considered material create a realistic prospect of success.

- Both parties rely on the decision of R (WM (DRC)) v SSHD [2006] EWCA Civ 1495. The key points as I find are: from paragraph 9 "the determination of the Secretary of State is only capable of being impugned on Wednesbury grounds"; and from paragraph 11 that "the question is not whether the Secretary of State himself thinks that the new claim is a good one or should succeed", but whether there is a realistic prospect of success on an application before an immigration judge and; in answering that question, the defendant must be informed by "anxious scrutiny" of the material.

- This is repeated in AK (Afghanistan) v SSHD [2007] EWCA Civ 535 at paragraph 23 where Toulson LJ said that the question which the defendant must ask himself is "whether an independent tribunal might realistically come down in favour of the applicant's asylum or human rights claim on considering the new material together with the material previously considered".

- The two key country guidance cases are AAH (Iraqi Kurds internal relocation) Iraq CG UKUT 00212 (IAC) ("AAH") and the Court of Appeal's decision in AA (Iraq) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] EWCA Civ 944 ("AA"). They are in the Authorities Bundle ("AB") at tabs B and C. AAH supplements the guidance in AA. Although it is not appropriate to quote the guidance in full or repeat the lengthy extracts from the submissions/skeletons, it is necessary to set out, firstly from the headnote in AAH, the following:

- Paragraph 5 of the judgment sets out detailed evidence which the tribunal heard in relation to the issue of obtaining a CSID. This detailed evidence came from an expert, Dr Fatah. He described how births, marriages and deaths are recorded in the family registration book held in the Civil Registration office of the governate where a person's family registration is held. They are described as huge ledgers containing handwritten entries, but they are not a readily searchable database (paragraph 20).

- A CSID card is a crucial document for adult life in Iraq (paragraph 23) Without one, an individual cannot legally work or find accommodation. One cannot vote or access services such as education and healthcare, receive a pension or food aid, confidently cross a checkpoint, withdraw money from your own bank or even purchase a Sim card for mobile phone. A CSID enables the holder to obtain other documents such as a passport and a driver's licence or to obtain food rations.

- Dr Fatah said that a CSID is to be obtained from the office of the civil registrar in the individual's relevant district. Under ISIL control, all recording of official events was banned and some civil register offices such as that in Mosul were damaged or destroyed. The effect is that there is a huge backlog given that for three years from 2014 to 2017 no marriages, births or deaths were recorded. In Mosul alone, there are 1.5 million Iraqis who will need their records updated.

- In order to obtain a CSID one needs other documents including a birth certificate. The easiest way to get a new CSID is on production of an old or damaged CSID. It is clearly important to obtain one as a matter of urgency, given its crucial nature.

- Without access to food rations, healthcare or government humanitarian services and without assistance from family and friends those with no CSID would be pushed to the very margins of society and most likely end up on the streets or in a squatter tent or the like with no prospect of finding work and poor food security (paragraph 19(iii)).

- In AAH the then Secretary of State accepted that returnees who were not in possession of a CSID and who are unable to obtain one would face a real risk of destitution in all parts of Iraq such that Article 3 ECHR would be engaged.

- At paragraph 100 the decision records that a critical part of a decision-maker's enquiry will relate to documents and the first question to be asked is whether the proposed returnee is in possession of a CSID and, if he is not, whether it is reasonably likely that he will be able to obtain one.

- The situation is complicated not just by the fact that the Iraqi civil registration system is in disarray but that the willingness of officials to assist undocumented IDPs is not promising. Dr Fatah gave evidence that IDPs attempting to recover lost documents are being met with "indifference, corruption, incompetence and even sarcasm" by the authorities.

- In the AA case (at page 1097), items 9 to 11 of the Guidance Annex set out:

- In this case, as in AAH, the defendant does not dispute the importance of the CSID. At paragraph 7 (i) of the Detailed Grounds of Defence it concedes that "the obtaining of a CSID is of central importance". Similarly, there has been no challenge in this case to the claimant's submission that without a CSID the claimant would face the risk of Article 3 ill-treatment.

- The defendant does not dispute that a person's ability to obtain a CSID is likely to be severely hampered if they were unable to go to the Civil Status Affairs office of their governorate because it is in an area where Article 15 (c) serious harm is occurring. This includes Mosul from where the claimant originates (see defendant's skeleton argument paragraph 35 (ii)).

- Further in accordance with the CG cases, the defendant did not dispute that the "laissez-passer" which the claimant had would not enable him to obtain a CSID.

- I was referred to two documents at tabs S and T (AB). The first document (tab S), headed "Starred and Country Guidance Determinations" sets out that a reported determination of the tribunal bearing the letters CG shall be treated as an authoritative finding on the country guidance and thus unless it has been expressly superseded or replaced by any later CG, the determination is authoritative in any subsequent appeal so far as that appeal (a) relates to the country guidance issue in question and (b) depends on the same or similar evidence. 12.4 sets out that any failure to follow a clear apparently applicable country guidance case or show why it does not apply to the case in question is likely to be regarded as grounds for appeal on a point of law. At tab T is the Guidance Note 2011 No. 2, "Reporting Decisions of the Upper Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Chamber". It provides: -

- R (SG (Iraq)) v SSHD 2012 EWCA Civ 940 (AB tab K) concerned a stay pending appeal to the Court of Appeal where the court was looking at the status of CG. At paragraph 27 Stanley Burton LJ cited Irwin J (as he then was) in HM (Iraq) v SSHD 2011 EWCA Civ 1536 who said, when considering what the impact of a country guidance case should be: -

- Stanley Burton LJ went on at paragraph 44: -

- Further, he said: -

- In R (Madan) v SSHD [2007] EWCA Civ 770 (AB tab P) at paragraph 12 Buxton LJ said: -

- The claimant thus argues that CG has special status. It is not suggested that it is unassailable, but the claimant contends that neither is the defendant's new evidence unassailable, in particular when set against the existing CG. It would be an error of law not to follow the CG unless very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence is adduced by the defendant. The defendant contends that the CPIN does amount to such strong grounds based on clear, cogent evidence.

- The CPIN document dated October 2018 is at MB p416. It reiterates as far as a returnee obtaining a CSID in Iraq is concerned, the key points from AA and AAH. Again, it does not seem that: the importance of the CSID; the difficulties there may be in obtaining one; the unreasonableness of requiring somebody to travel to a contested area without a CSID; or that a person's ability to obtain a CSID is likely to be severely hampered if they are unable to go to the Civil Status Affairs office of their relevant governorate because it is in an area where Article 15(c) serious harm is occurring have changed and the defendant accepts these factors in the CPIN.

- There are two particular sections upon which the defendant in this case relies as showing that despite the CG determinations there is now fresh, credible and cogent evidence that a returnee could obtain a CSID within a reasonable time and that this applies to the claimant.

- The first section reads:

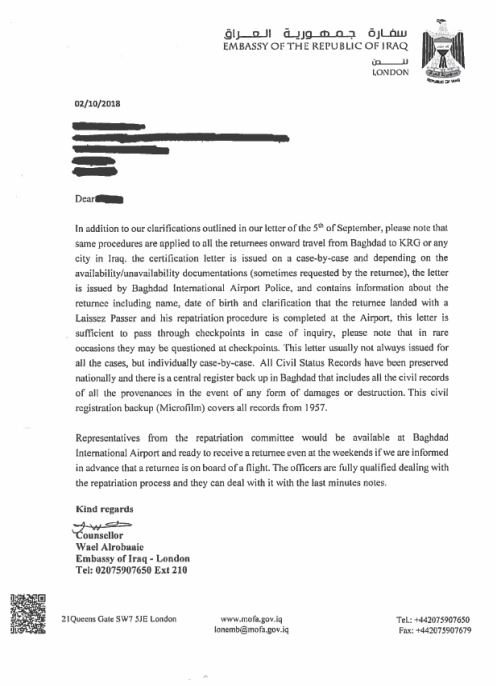

- The second section is Section 2.6.16 which reads:

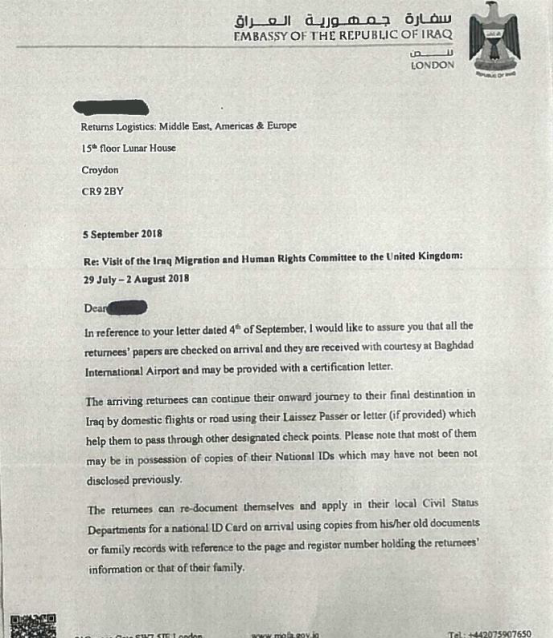

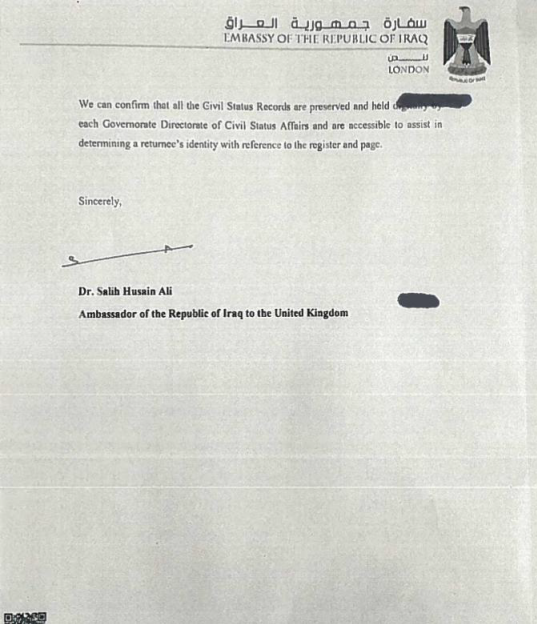

- The letter at Annex B copied below is from Counsellor Wael Alrobaaie form the Embassy of Iraq London.

- The witness statement of Diane Drew (SB p7) on behalf of the defendant dated 16 April 2019 sets out that she is Assistant Director of Home Office Returns Logistics currently employed in the Country Liaison and Documentation: Middle East, Europe and Americas team within the Returns Logistics section of Immigration Enforcement. She says that the main function of the team is to obtain travel documentation from diplomatic missions to facilitate the return of individuals who are in the United Kingdom unlawfully and to manage the returns process with receiving countries.

- She describes a visit from an Iraqi delegation to the UK between 29 July 2018 and 2 August 2018 and a discussion on 31 July 2018 as part of the agenda between Home Office officials from the special appeals team and Country Policy and Information Team ("CPIT") and the Iraqi delegation consisting of senior officials from National Security Department, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Chief of Police at Baghdad airport. The discussion was about the issue of CSIDs. Miss Drew sets out that during those meetings the delegation said that they felt strongly that the information in the country guidance caselaw is out of date, namely, that a CSID is easily obtainable. She says that the Chief of Police at Baghdad airport confirmed to herself and those in attendance at the meeting, that if a person holds a laissez-passer, that person is able to travel from Baghdad to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) using that laissez-passer.

- Following the delegation's visit Miss Drew's team sent a letter asking for further information about the ability of returnees to obtain a CSID to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Baghdad. No response was received and so the Iraqi Embassy in London was contacted which said that a request should be made to the Ambassador. This was done and on 5 September 2018 the Iraqi Ambassador in London sent the letter which forms Annex A in the CPIN.

- There were then meetings between the Returns Logistics team and the CPIT and in consequence Dr Wael Alrobaaie from the Iraqi embassy in London sent a letter dated 2 October 2018 which is the Annex B letter. This identifies what a certification letter is and how it may assist to obtain a CSID.

- Miss Drew sets out that it was upon receipt of this letter that the CPIN was updated as identified above.

- She confirms that the claimant was given a laissez-passer to enable him to travel to Iraq on 18 November 2018. Thus, she sets out at paragraph 12 that it is her belief that the claimant can obtain a CSID card and can travel from Baghdad to KRI on the laissez-passer he travelled with to Baghdad. (I note that the claimant's home area is Mosul).

- Miss Drew exhibits the chain of correspondence. The letter of 5 September was written in response to the letter at SB p4 which asks if the laissez-passer (where a returnee has no other documents) is enough to enable somebody to get an internal flight from Baghdad to any other part of Iraq and travel by road through designated checkpoints. Dr Ali was asked for an explanation of the process of how to obtain a replacement CSID and for details of the records held and preserved which are accessible to assist in determining a returnee's identity with reference to the page and volume number of the book containing their family's information

- Thus, the defendant relies on this evidence which he says is credible and cogent and provides strong grounds to depart from the CG cases where there has been a change in the situation in Iraq. The defendant says that if a returnee does not have a CSID he can obtain one from the Civil Status Affairs office in their home governorate but if they cannot return alternate CSA offices have been established including in Baghdad and those alternative CSA offices do issue CSIDs. There is a central archive, but it does not provide CSIDs. The defendant accepts that to get a CSID another document would be of assistance (but not a laissez-passer). The defendant agrees that male family members who can attend may help. It is the defendant's case that these letters confirm that all the records that are in existence have been backed up and so there are now two different databases, firstly in the CSAs and secondly backed up on microfilm.

- The defendant contends that in the light of this cogent, credible, fresh evidence he does not need to follow the CG relating to obtaining a CSID and there is no requirement that the fresh evidence should be tested in court. The defendant's case is that the claimant does not need to return to Mosul, he can attend the CSA office in Baghdad. He can find his entry in the civil register because all the civil status records are preserved and held digitally by each governorate directorate of Civil Status Affairs and are accessible.

- The defendant goes as far at paragraph 35 of the skeleton argument as saying that he was not only entitled but was compelled to apply the amended and up-to-date CPIN.

- The defendant refers me to the case of Rasoul v SSHD PA/13927/2016, an appeal to the Upper Tribunal where the Upper Tribunal judge was satisfied that the most up-to-date evidence shows that there is a central register in Baghdad which includes all the civil records of all the provinces and "given that the appellant did give evidence that he had an Iraqi passport and ID documents previously, there are documents in existence which could prove his identity". The Upper Tribunal judge felt that the claimant in that case could approach the Iraqi authorities in the United Kingdom to obtain a replacement passport/laissez-passer and could approach the Iraqi Embassy in London and through them obtain a CSID to enable him to return to Iraq and travel from Baghdad to Kirkuk. It is apparent that the appellant in that case was still in the UK and had acknowledged that he previously had documentation. Further, he was intending to travel to Kirkuk which at the date of the decision on 8 January 2019 was no longer a contested area.

- The claimant contends that the proper place for the consideration of the defendant's new evidence is the First-tier Tribunal where he would have a realistic prospect of success in resisting the defendant's submissions that the new evidence overturns the country guidance. The claimant denies that the defendant is compelled to act on this new evidence and in any event raises doubts about its cogency and credibility in particular in the claimant's individual circumstances. The claimant refers to the vague terminology used in the correspondence from the Embassy and points out that the information provided is in very general terms. The evidence has not been tested by reference to questions such as: why is there still a crisis of undocumented people in Iraq if there is an accessible, searchable database of records? What is the mechanism at the alternative CSA offices for obtaining records? When did this database came into existence? It is not clear if it is searchable. It is not clear how it is searchable. The defendant acknowledges that it will not contain all of the records that have ever existed since 1957 but only those that were in existence at the time that those records were "backed up". The completeness of the database is therefore unknown. It is not clear how this new evidence contained in brief and general sentences in two pieces of correspondence would compare on analysis with the CG cases.

- The claimant refers me to another decision of the Upper Tribunal Omar Rasoul Ali v SSHD PA/05814/2017 where the correspondence from Dr Ali was put before the Judge. In that case it was not suggested that the appellant could obtain a CSID from the Iraqi Embassy in the United Kingdom by the defendant, but it was submitted that he could do once he arrived in Baghdad. The defendant referred to the delegation visit identified by Miss Drew. The two letters (from Dr Ali and Counsellor Alrobaaie) are set out and in that case, it was suggested that those statements be accepted in preference to the expert opinion of Dr Fatah in AAH. The judge in that case considered that the letters are couched in generalities and do not address the particular facts of an individual appellant and refer to a case-by-case approach. The correspondence does not express a firm and binding government undertaking. Whilst not questioning the bona fides of the Ambassador the Judge did not consider that the letters provided a fair and robust foundation sufficient to sustain a departure from the recent CG in AAH. He referred to the categorisation by the Upper Tribunal of Dr Fatah's evidence as "measured, detailed and well-sourced". The Judge considered that this correspondence "evidences a direction of travel which is to be welcomed" but he did not consider that "as currently constituted it amounts to cogent evidence constituting strong grounds for departing from the country guidance in AAH".

- These are both unreported determinations, but I was referred to them in light of the guidance in paragraph 12 of Madan cited at paragraph 39 above.

- The defendant contends that there are limitations to the evidence of Dr Fatah in the two CG cases, but I was referred to the assessment of it set out at paragraph 59 above.

- The defendant has referred me to the decision in R (Mohammed Safeer) v SSHD 2018 EWCA Civ 2518 which sets out at paragraph 19 that the basic rule is clear, namely that "where there is a dispute on the evidence in a judicial review application then in the absence of cross-examination the facts in the defendant's evidence must be assumed to be correct".

- It does not seem to me that this principle is controversial. However, neither does it seem to me that it takes this matter much further. There is no direct challenge to the evidence of Miss Drew herself. The Administrative Court is not an appropriate venue for the testing of evidence by oral evidence and cross-examination. There is no dispute or challenge and I accept that there was the Iraqi delegation visit. I accept that she wrote the correspondence referred to and that she received the replies that she has referred to. However, the rule or principle cannot go further so as to mean that the court is bound to accept the truth of the contents of the letters from others which she exhibits. The point may not in fact be material in this case on analysis, even taking the information at face value.

- The claimant urges me to treat the evidence of the Iraqi authorities with some caution particularly in light of paragraph 111 of AAH where it was noted that despite the Home Office being assured by the Iraqi authorities that they would "assist with any onward travel documentation", the court had seen no evidence that that had happened or what that documentation might be.

- I have no grounds to doubt the bona fides of the authors of the 2 letters, but it would be wrong to ignore either the evidence of Dr Fatah about the approach of officials in Iraq (see paragraph 30 above) or the lack of evidence in AAH of actual assistance. I have to assess what the letters say, and decide whether when the defendant made the decision not to treat the claimant's submissions as a fresh claim it was reasonable to conclude that the contents of that correspondence from the Iraqi Embassy (leading to the updated CPIN) was sufficiently clear and cogent fresh evidence as to amount to strong grounds not to follow the CG and that therefore the claimant had no reasonable prospect of persuading a tribunal judge that the CG should be followed rather than the CPIN in the circumstances which pertained to the claimant himself.

- Following the decision in R (Lumba) v SSHD [2011] UKSC 12, a public law error that bears on a decision to detain can render that detention unlawful. I was referred also to R(Lauzikas) v SSHD [2018] EWHC 1045 Admin (AB tab A) where Michael Fordham QC concluded that a public law error that arose in a decision distinct from the decision to detain could render that detention unlawful, (paragraph 54): -

- At paragraph 38 in respect of a distinct decision Michael Fordham QC referred to Lumba again and identified from that case that: -

- Further, at paragraph 42: -

- From paragraph 53 (i) comes the proposition that the refusal of a putative fresh claim is an example of a relevant distinct decision public law breaches in the making of which could render detention unlawful.

- Finally, from Lauzikas at paragraph 19: -

- The claimant says that had his application been treated as a fresh claim, he would have had an in country right of appeal. The public law breach in refusing to treat his application as a fresh claim clearly bore on the defendant's decision to detain him, that decision being based on the imminence of and the lack of barriers to his removal and therefore his detention was unlawful. The question then is whether or not he would have been detained anyway and the answer to that dictates whether any damages would be nominal or substantial.

- The claimant argues that given that there would have been an in country right of appeal, there would in fact then have been a barrier to the claimant's removal which would have been such that he may have been released. The date of the conviction which gave rise to the decision to deport was 27 March 2009, more than nine years previously. In the absence of any offending since 2009 the claimant contends that his detention was not inevitable, and it is not inconceivable that he would have been released since he could only have been detained with a view to removal.

- The claimant refers me to the defendant's documents at MB pp349 357 where one of the reasons justifying detention of the claimant on the review dates was the lack of barriers to removal. At the top of p350 is a reference to the fact that whilst the claimant posed a high risk of absconding, the officer did not agree with the risk assessment that he posed a high risk of reoffending in the absence of any further offending since 2009. It goes on to read "Therefore, if removal from the UK is not imminent, then risk of reoffending should not be used as an argument to maintain detention". Further "if no travel document is agreed, then consideration must be given to his release". The conclusion was that he should remain in detention "due to the fact [his] detention is to specifically progress his removal from the United Kingdom". At p357 the reviewer identifies that the claimant's suitability to remain in detention would need to be assessed immediately if either there was difficulty obtaining travel documents or he was successful in his stateless application. Similarly, at p359 it is set out "if no travel document is agreed, then consideration must be given to his release".

- It is the defendant's case (again following the decision in Lauzikas) that not all public law errors render detention unlawful and in this case the decision to refuse to treat the claimant's representations as a fresh claim was not a distinct decision which bore on detention. The defendant says that even if the fresh claim decision had been made differently, detention would still have been lawful because the claimant would have remained in detention pending his appeal.

- The defendant says that the detail for example in the entry at p347 is important because there is no conceivable basis on which he would release an individual with those risk factors. He was a foreign national offender. There would have been a reasonable prospect of removing him "in due course" and even applying Hardial Singh considerations where there is some prospect of a detainee being removed there are many cases where they remain in detention pending appeal.

- The defendant goes on to say that in any event even if I conclude that the decision was unlawful, and it bore on the claimant's detention I should consider whether he would have been detained in any event the answer to which will decide whether any damages would be nominal or substantive. In light of his assessment as being at a high risk of absconding, high risk of reoffending and a high risk of harm as identified in the documents at MB p346 onwards he would have been detained in any event. Looking at page 351 the high risk of reoffending was reasserted particularly in light of the fact that the claimant re-entered the UK when he was subject to an enforced deportation order. That is further demonstrated by the fact that on 6 August 2018 he was released from prison but detained with a view to deportation.

- There is no dispute between the parties or in the CG and I find the matters set out at paragraphs 24, 27 and 28 above are proved, namely that a CSID card is a crucial document for adult life in Iraq and without it a person would face a real risk of destitution such that Article 3 would be engaged. It is similarly not disputed that one needs to obtain a CSID reasonably quickly in order to avoid such destitution/Article 3 ill-treatment. It was submitted and I find that this is the reason why the ability to obtain a CSID within a reasonable timeframe is "front and centre" of the two CG cases. The CG as I find sets out in strong terms and significant detail the difficulties in obtaining a CSID in the absence of other identity documents (in particular a previous CSID or birth certificate) and without being able to trace one's family's page and volume number in the ledgers held at the CSA offices.

- I find and it is not disputed that the CG has a special status and if it is not followed in the absence of anything else it would amount to a ground of appeal on a point of law (even though based on a finding of fact). The CG remains in place until it is expressly superseded or replaced. The relevant CG in this case was as recent as 12 June 2018 and the new evidence upon which the defendant relies came to light in September/October 2018 and the CPIN was created in October 2018 (a mere four months later).

- I find that given the recent nature (at the time of the defendant's decision in this case) of the CG even in a situation which might be evolving/changing, it would require very careful consideration and scrutiny even of fresh clear and cogent evidence for it to be relied on as "strong grounds" sufficient to supersede such recent CG.

- I accept (as did the claimant) that the CG is not, however, unassailable where there are strong grounds not to apply it based on fresh cogent and reliable evidence. Equally, I accept that the defendant has to look at all the available material and information when considering whether or not the CG with its special status, remains applicable. I do not accept, as was submitted on behalf of the defendant that he is "compelled to apply" the CPIN. The CPIN is additional information to be taken into account where appropriate following an analysis of the relevance/importance of the information to an individual case and by comparison with the current CG.

- Given the crucial importance of the CSID and as set out at paragraph 100 of the decision in AAH, it was a critical part of the defendant's enquiry when considering the claimant's further submissions to ask whether the claimant, not being in possession of CSID, was reasonably likely to be able to obtain one and to obtain one in a reasonable timeframe.

- In the decision letter (see paragraph 17 above) the defendant simply asserts that the claimant's submission that he could not obtain a CSID had no realistic prospect of success because "country information shows that your client can obtain a CSID card".

- This view is supported in even more confident terms by Miss Drew in her witness statement where she says at paragraph 5 that she was told by "the delegation" that "a CSID is easily obtainable".

- It seems that the defendant has acted on that oral information and sought confirmation of it, and having obtained the two letters, amended the CPIN and then relied on it in preference to the CG in making the decision in the claimant's case.

- An analysis of the two short sections of the two letters relied on in the CPIN shows, as I find, that they do not amount to clear cogent evidence amounting to strong grounds to say that a CSID is now "easily obtainable" in Iraq by a returnee. They are limited to the facts they state. One has to consider to what extent that could or should alter or amend the CG.

- The defendant specifically does not suggest that the claimant could go to Mosul. The defendant asserts that the claimant could get a CSID from one of the alternative CSAs in Baghdad and that the databases referred to would help him with that. We know that the central archive does not issue CSIDs. There is no information in either letter about this "microfilm" database. It may not be searchable in which case it is of little use to somebody who does not know their "page and reference number". It is not clear from the evidence if it is the same central archive which was referred to by Dr Fatah in the CG cases. If it is the same then clearly it does not alter the position from the CG. If it is a new archive, recently created in the space of a few months, the defendant has not analysed or explored how it would enable the claimant to obtain a CSID.

- There is nothing in the new information to suggest that headnote item 1 (i) in AAH about the difficulty in obtaining a CSID without other documentation or about the need to "trace back" to the family record has changed. There is no reference to the length of time it would take to obtain a CSID and it still seems that family and birth details are required. Dr Ali does not refer to the microfilm back up in Baghdad but only to the local CSAs. He does suggest that they are held "digitally" which may mean the previous ledgers have been replaced but he still refers to the family records with reference to the "page and register number". It is known that many records were destroyed and it is known that many details of births etc have not been maintained. It is therefore not known what proportion of the original records have been preserved. There is no information about the records held in the alternative CSAs in Baghdad or if they are searchable or accessible or if they are, by whom they can be searched or accessed.

- The defendant accepts that the records can only be held digitally in so far as they existed at all. We do not know if the claimant's records exist. There is nothing to suggest that the ledgers containing handwritten entries referred to by Dr Fatah have altered in form even if now preserved "digitally". There is no reference to whether or not there remains a huge backlog for the three years from 2014 to 2017. There is no mention of when and how such a backlog might have been dealt with. The correspondence does not address Dr Fatah's evidence about the attitude of officials in assisting undocumented IDPs.

- Although not cited by the defendant in the CPIN, the correspondence makes it clear that for example a certification letter "is issued on a case-by-case and depending on the availability/unavailability documentations". I find that there is nothing in this correspondence to support the contention that there is any degree of certainty about the re-documentation of returnees.

- It seems to me therefore that the correspondence relied on and included in the CPIN, taken at its face value establishes no more than that there is a digital record in each governorate accessible to assist in determining a returnee's identity but it is not clear when this was created or if or how it can be searched or if it contains the claimant's records. There is a backup central register in Baghdad on microfilm but it is not clear whether that is searchable, what records it holds, whether it would include the claimant's records, whether it is the same as the archive referred to in the CG cases, or whether it is can be accessed by a returnee to establish identity sufficient to acquire a CSID.

- Whilst the defendant can rely on the CPIN, it must be seen as part of the totality of the evidence. I find that this new information whilst it may be relevant, is not sufficiently clear and coherent to constitute strong enough grounds to supersede the CG. It may supplement it. It certainly gives rise to the need for further enquiries.

- The information is that the only document the claimant had was a laissez-passer. If that was confiscated he would have no documentation at all. Even with it, it would not help with his identity documentation. It is for this reason that the CG remains that the laissez-passer does not count when considering how a returnee can obtain a CSID. Although the First-tier tribunal (MB p404) did not find that the claimant has no family in Iraq, it made no positive finding about what family he might have or where. The claimant indicated in his submissions that he had no family in Baghdad. The defendant does not suggest that he could in fact travel to Mosul. Even looking at the decision letter holistically as I am urged to do, I cannot find that the defendant considered the claimant's specific circumstances/characteristics either in accordance with the information in 1 (iii) of the head note to AAH or item 10 of the Guidance in AA.

- At paragraph 16 of the decision letter the defendant repeats what was set out some seven years previously to say that having no family or suitable accommodation or means of support would not be reasons for granting a person asylum and given the claimant's age he is capable of living independent from his family. They repeat the tribunal's finding about the claimant's lack of credibility on this point (made in respect of his situation seven years previously). Having cited the CG and the CPIN, the defendant answers all the points by saying that he can obtain a CSID. It does not indicate that the defendant has given any consideration as to how he would do that.

- The defendant's reference to the decision in Rasoul (above) is of limited assistance, in particular because although at the time of the decision that claimant's whereabouts were unknown, the court was considering the position of somebody attempting to obtain a CSID in the UK before returning to Iraq in which circumstances he would not be at risk of Article 3 ill-treatment. In SI (reported cases as evidence) Ethiopia [2007] UKAIT 00012 (AB tab O) at paragraph 21 it is set out that it might be appropriate not to follow a CG case on a relevant issue if, in the context of a particular case, there is fresh evidence compelling (my emphasis) a different view albeit "the wider the risk category posited the greater the duty on an immigration judge to give careful reasons [for not following a CG case] based on an adequate body of evidence". This confirms my view that in circumstances where the risk is of ill-treatment/destitution for an undocumented returnee to Iraq very careful scrutiny is requires and a comparison of the fresh evidence which must give rise to strong grounds.

- It seems to me moreover, by reference to the SI case and also to the Guidance Note referred to at paragraph 35 above that departure from the CG cases whilst contemplated by the courts has so far been considered in the context of a decision being made by the First-tier Tribunal judge rather than a decision-maker. This is further confirmed by the case of Madan (paragraph 39 above) which again refers to a judge in a judicial review application treading carefully before finding that the country guidance case is unreliable and sets out that the parties "will want to ensure that he is aware of any decisions in the AIT subsequent to the country guidance". Clearly, this does not mean that a decision maker cannot decide not to apply the CG (as in the case of SG cited at paragraph 36 above), but it does suggest that those decisions have been subject to appeals/judicial review on the basis that the decision was wrong. That a court may come to a different view about the application of the CG (given its special status) to that of a decision maker is therefore apparent.

- I find that the decision-maker on behalf of the defendant in this case did not adequately consider the particular conditions which the claimant would face to the standard required and as identified by Stanley Burton LJ at paragraphs 44, 46 and 47 of the decision in SG.

- I find that in this case if the CG had been applied unadorned and unamended the claimant submissions would undoubtedly have given rise to a fresh claim. As set out the claimant does not have to show that he would be bound to succeed and I find that it cannot be said in this case that an immigration judge would be bound to conclude that the CPIN and information available overrides the CG or would override it in the claimant's case. Indeed, by reference to the Omar Ali case it is apparent that a tribunal judge clearly could form the view that the CG guidance should be followed in preference to the CPIN because a judge did so in that case. In the circumstances I do not consider that the defendant can properly argue otherwise.

- Moreover, while there is no evidence to challenge the bona fides of the two authors of the letters even taking their contents at its face value, it is very limited information, and it still has to be compared with all the other evidence available in particular of course in the CG cases as well as the features referred to at paragraph 42 of the decision in MD (Ivory Coast) v SSHD [2011] EWCA Civ 989 which sets out that while diplomatic missions may be able to provide highly relevant information, that information must be assessed in light of all the relevant factors including "independence, reliability, objectivity and corroboration et cetera".

- In summary, therefore, I find that the defendant was wrong to apply the CPIN rather than follow the CG because: the information/evidence in the CPIN was limited in both scope and content; the new evidence is not clear as to its actual effect in Iraq; the decision-maker failed to consider how it would affect this claimant's ability to obtain a CSID within a reasonable timeframe and; the CG was recent, comprehensive, detailed and reliable in comparison.

- The defendant was wrong to consider himself compelled to apply the CPIN.

- Taking into account the contents of the CID records/detention reviews cited above it seems to me that this distinct decision (not to treat the submissions as a fresh claim) did bear on the decision to detain. It was considered as part of the overall picture and assessment and weighed against the presumption of release because the decision gave rise to a situation in which there were no barriers to the claimant's removal and his removal was likely to take place quickly. He was in fact held in immigration detention for a total of about 3 1/2 months and returned to Iraq 4 days after the decision.

- Had this been treated as a fresh claim so that he had an appeal pending then the defendant would have been bound to take into account how long he would be in detention before resolution of that appeal. Of course, as the defendant points out, some people are held in immigration detention for lengthy periods of time. I accept that the defendant was properly concerned about the risk presented by the claimant as an absconder and a foreign national offender. However, it must also be a feature of the decision that as an appeal rights exhausted detainee whose removal was planned take place soon, the risk of his absconding would be significantly greater than the risk of a person who had an appeal pending absconding. As set out above, his criminal offending was many years previously. I find therefore that the decision did bear on the decision to detain.

- The final question therefore is whether or not the claimant would inevitably have been detained. In Lumba, where a claimant had been detained for 54 months, Dyson LJ said at paragraph 144 "there must come a time when however great the risk of absconding and however great grave the risk of serious offending, it ceases to be lawful to detain a person pending deportation".

- The defendant in submissions stated that there was no conceivable basis on which he would release an individual with the claimant's risk factors. Even with these risk factors there must always be cases and situations in which the prospect of removal becomes too remote or too far in the future to justify continued detention. So, it is wrong to suggest that there would be "no conceivable basis" on which the claimant would be released. If that were the case there would be no need for detention reviews after the initial one.

- Given the age of the offending, the need for a reassessment of the absconding risk and the length of delay pending resolution of the appeal it is not possible to say that the claimant would inevitably have been detained in this case.

- However, given he was returned to Iraq on 18 November, he was only detained for 4 days after the relevant decision.

- In light of my findings in relation to the issues identified above I find that the defendant's decision to refuse to accept the claimant's further representations as amounting to a fresh claim was unreasonable. The decision was Wednesbury unreasonable in the sense that no reasonable Secretary of State could have concluded that the claimant's claim had no realistic prospect of success before the immigration judge. Informed by anxious scrutiny of the material, including both the CG and the CPIN, but also the information pertaining to the claimant himself, the defendant should have concluded that there was a realistic prospect of success.

- That decision was distinct from the decision to detain but bore on the decision to detain (and the consequent refusal to defer removal). I further find that it was not inevitable that he would have remained in detention had the further submissions been accepted as a fresh claim.

- Therefore, I make the quashing order, quashing the decision of the defendant to refuse to treat the claimant's representations as a fresh claim. Following discussions with counsel I agreed that in respect of any other relief sought I would be provided with written submissions following the handing down of this judgment and provide a supplementary judgment on those points, if necessary.

HHJ Coe QC :

The Main Issue

Background

Preliminary Matters/Defendant's Applications

Fresh Claims

"you stated that your client cannot obtain a CSID, but this assertion has no realistic prospect of success because country information shows that your client can obtain a CSID card. Further, your client waited until November 2018, to raise the submission after removal directions had been set, his credibility. That said as demonstrated above, your client can obtain a CSID card and as a result will not be destitute; your submissions are therefore, rejected."

"When a human rights or protection claim has been refused or withdrawn or treated as withdrawn under paragraph 333C of these Rules and any appeal relating to that claim is no longer pending, the decision maker will consider any further submissions and, if rejected, will then determine whether they amount to a fresh claim. The submissions will amount to a fresh claim if they are significantly different from the material that has previously been considered. The submissions will only be significantly different if the content: (i) had not already been considered; and (ii) taken together with the previously considered material, created a realistic prospect of success, notwithstanding its rejection."

The Country Guidance

"1. Whilst it remains possible for an Iraqi national returnee (P) to obtain a new CSID whether P is able to do so, or do so within a reasonable time frame, will depend on the individual circumstances. Factors to be considered include:

(i)Whether P has any other form of documentation, or information about the location of his entry in the civil register. An INC, passport, birth/marriage certificates or an expired CSID would all be of substantial assistance. For someone in possession of one or more of these documents the process should be straightforward. A laissez-passer should not be counted for these purposes: these can be issued without any other form of ID being available, are not of any assistance in 'tracing back' to the family record and are confiscated upon arrival at Baghdad;

(ii)The location of the relevant civil registry office. If it is in an area held, or formerly held, by ISIL, is it operational?

(iii)Are there male family members who would be able and willing to attend the civil registry with P? Because the registration system is patrilineal it will be relevant to consider whether the relative is from the mother or father's side. A maternal uncle in possession of his CSID would be able to assist in locating the original place of registration of the individual's mother, and from there the trail would need to be followed to the place that her records were transferred upon marriage. It must also be borne in mind that a significant number of IDPs in Iraq are themselves undocumented; if that is the case it is unlikely that they could be of assistance..."

"The CSID

9. Regardless of the feasibility of P's return, it will be necessary to decide whether P has a CSID, or will be able to obtain one, reasonably soon after arrival in Iraq. A CSID is generally required in order for an Iraqi to access financial assistance from the authorities; employment; education; housing; and medical treatment. If P shows there are no family or other members likely to be able to provide means of support, P is in general likely to face a real risk of destitution, amounting to serious harm, if, by the time any funds provided to P by the Secretary of State or her agents to assist P's return have been exhausted, it is reasonably likely that P will still have no CSID.

10. Where return is feasible but P does not have a CSID, P should as a general matter be able to obtain one from the Civil Status Affairs Office for P's home Governorate, using an Iraqi passport (whether current or expired), if P has one. If P does not have such a passport, P's ability to obtain a CSID may depend on whether P knows the page and volume number of the book holding P's information (and that of P's family). P's ability to persuade the officials that P is the person named on the relevant page is likely to depend on whether P has family members or other individuals who are prepared to vouch for P.

11. P's ability to obtain a CSID is likely to be severely hampered if P is unable to go to the Civil Status Affairs Office of P's Governorate because it is in an area where Article 15(c) serious harm is occurring. As a result of the violence, alternative CSA Offices for Mosul, Anbar and Saluhaddin have been established in Baghdad and Kerbala. The evidence does not demonstrate that the "Central Archive", which exists in Baghdad, is in practice able to provide CSIDs to those in need of them. There is, however, a National Status Court in Baghdad, to which P could apply for formal recognition of identity. The precise operation of this court is, however, unclear."

The Status of Country Guidance

"if there is credible fresh evidence relevant to the issue that has not been considered in the country guidance case or, if a subsequent case includes further issues that have not been considered in the CG case, the judge will reach the appropriate conclusion on the evidence, taking into account the conclusion in the CG case so far as it remains relevant. Further "country guidance cases will remain on the UTIAC website unless and until replaced by fresh country guidance or reversed by decision of a higher court. Where country guidance has become outdated by recent developments in the country in question, it is anticipated that a judge of the First-tier tribunal will have such credible fresh evidence as envisaged in paragraph 11 above".

" one would look for clear and coherent evidence coming after the country guidance decision was reached, before the starting point and guidance given in such a case should be departed from. It seems to me adventurous to seek to draw quite general conclusions as to the reliability of any case or of any decision and particularly a decision which is denominated as a country guidance case merely from the fact that permission to appeal has been granted".

"I would emphasise that in the present context the primary purpose of the system of immigration decisions and appeals is to ensure that those who seek the protection of this country are not returned to their country of origin if on their return they will risk death or ill-treatment or serious harm It is therefore important that those who make the decisions on claims for protection have available a reliable determination of conditions in the country of origin of those who seek protection so as to determine whether or not there is such a risk"

"46. The system of country guidance determinations enables appropriate resources, in terms of the representations of the parties to the country guidance appeal, expert and factual evidence and the personnel and time of the tribunal, to be applied to the determination of conditions in, and therefore the risks of return for persons such as the appellants in the country guidance appeal to, the country in question. The procedure is aimed at arriving at reliable (in the sense of accurate) determination. 47. It is for these reasons, as well as the desirability of consistency, that decision-makers and tribunal judges are required to take country guidance determinations into account and to follow them unless very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence, are adduced justifying their not doing so".

"Country guidance cases have a special status, failure to attend properly to them being recognised by this court as an error of law even though country guidance cases deal only with fact They have that special status because they are produced by specialist court, after at least what should be a review of all the available material. And that in particular involves a judicial input from a background of experience, not least experience in assessing evidence about country conditions, that is not available to such judges as sit in the Administrative Court and in this court. A judge hearing a judicial review application will therefore wish to tread carefully before finding that a country guidance case is unreliable just on the basis of one or two subsequent reports. The parties appearing for him will in particular wish to ensure that he is aware of any decisions in the AIT subsequent to the country guidance case in which that case has been considered".

The CPIN

"2.6 .15 In September 2018, the Iraqi ambassador to the United Kingdom confirmed that "all the Civil Status Records are preserved and held digitally by each Governorate Directorate of Civil Status Affairs and are accessible to assist in determining a returnee's identity with reference to the register and page".

Annex A to the CPIN provides a copy of the letter dated 5 September 2018 from Dr Salib Hussain Ali, Ambassador of the Republic of Iraq to the United Kingdom which I have copied:

"In AA, the UT found: 'The evidence does not demonstrate that the "Central Archive", which exists in Baghdad, is in practice able to provide CSIDs to those in need of them. There is, however, a National Status Court in Baghdad, to which [a person] could apply for formal recognition of identity. The precise operation of this court is, however, unclear.' (paragraph 204 (13)). However, in October 2018, the Iraqi Embassy noted that 'there is a central register back up in Baghdad that includes all the civil records of all the provenances [sic] in the event of any form of damages or destruction. This civil registration backup (Microfilm) covers all records from 1957.' (see Annex B)."

The Status of Miss Drew's Evidence and the CPIN

Detention

" detention by the Secretary of State is rendered unlawful by a material public law breach in a distinct decision where that decision and that breach bear on the detention".

"What mattered was the nexus between the public law breach and the detention".

"a public law error in a distinct decision bearing on the detention can render the detention unlawful notwithstanding that the public law error was not bad faith or "jurisdictional" error, provided at least that it is substantive unreasonableness which renders the detention itself unreasonable"

"Turning to the remedy of damages, executive detention constitutes the tort of false imprisonment where there has been "the unlawful exercise of the power to detain", even if "it is certain that the claimant could and would have been detained if the power had been exercised lawfully", because detention by "a public authority" requires "power to detain" which has been "lawfully exercised": Lumba, para. 71 However, only nominal and not compensatory damages are recoverable where, had the power been exercised lawfully "it is inevitable that the [claimant] would have been detained" (the Lumba case, paras 95 and 169"

Analysis

Conclusion

Relief