Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Journals

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Journals >> Connolly and Gough, 'Retirement Age and Occupational Pensions: Experiences From Canada and Predictions for Britain'

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/other/journals/WebJCLI/2007/issue1/connolly1.html

Cite as: Connolly and Gough, 'Retirement Age and Occupational Pensions: Experiences From Canada and Predictions for Britain'

[New search] [Help]

|

[2007] 1 Web JCLI |

| |

|

|

|

Age Discrimination, The Default Retirement Age and Occupational Pensions: Experiences From Canada and Predictions for Britain

Michael Connolly

Dr Orla Gough

University Of Westminster

Copyright © Michael Connolly and Orla Gough 2007.

First published in the Web Journal of Current Legal Issues.

Summary

On 1st October 2006, the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006 come into force. Expectations of older workers will be dampened however with the inclusion of a “default retirement age”, entitling employers to retire workers aged 65 or over, without justification. A major reason given for this exemption is to preserve the stability of occupational pension schemes. In Canada, a challenge to a similar retirement exemption failed in the Supreme Court. The reason was based, in part, on the need to preserve the stability of pensions. This paper argues that the Canadian experience can be distinguished and that default retirement age in the British legislation is questionable under European law and is not necessary to preserve the stability of pension schemes.

Contents

1. Introduction

The “Framework” Directive’s 2000/78/EC prohibition of age discrimination had to be implemented by October 2006. The consequent Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006 (SI 2006/1031) allow employers to retire workers in two different circumstances. First, with a “default” retirement age of 65 which will enable employers to dismiss workers reaching that age on the ground of retirement, without objective justification. Second, employers will be able to retire their workers at any age, provided they can objectively justify such a policy. Should employers agree to keep on a worker beyond 65, the general principle against age discrimination will apply, save, of course, to cases of retirement.

The Government stated that a major reason why employers will wish to take advantage of the default retirement age would be to preserve the “stability” of their occupational pension plans. Of course, employers may have this in mind when justifying an earlier retirement age.

The aim of this paper is first, to question the legitimacy under the Directive of a default retirement age. Second, to explore whether a default retirement age is necessary to preserve the “stability” of occupational pension plans. A similar issue has arisen in the Canadian Supreme Court, and its experience will be used in the analysis. Third, to explore the legal possibilities of defending an employer’s mandatory retirement age below 65 against a claim of age discrimination, where the principal reason for the retirement is to protect an occupational pension scheme.

2. The EU Legislation

The starting point is the main text of the Framework Directive:

“Article 2

Concept of discrimination

1. For the purposes of this Directive, the “principle of equal treatment” shall mean that there shall be no direct or indirect discrimination whatsoever on any of the grounds referred to in Article 1.”

Article 1 refers to religion or belief, disability, age, and sexual orientation as the grounds covered by the Directive. The precise definitions of discrimination follow the models developed by the ECJ and used in the Equal Treatment (sex) Directive 76/207 and Race Directive 2000/43. Thus the Directive carries standard definitions of direct and indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation. Article 4(1) provides the now standard exception for “genuine and determining occupational requirements” with can be justified. The Directive departs from the norm with an extra derogation specifically for age. Article 6(1) provides:

“... Member States may provide that differences of treatment on grounds of age shall not constitute discrimination, if, within the context of national law, they are objectively and reasonably justified by a legitimate aim, including legitimate employment policy, labour market and vocational training objectives, and if the means of achieving that aim are appropriate and necessary.”

Three examples are provided by a non-exhaustive list:

“(a) the setting of special conditions on access to employment and vocational training, employment and occupation, including dismissal and remuneration conditions, for young people, older workers and persons with caring responsibilities in order to promote their vocational integration or ensure their protection; (b) the fixing of minimum conditions of age, professional experience or seniority in service for access to employment or to certain advantages linked to employment; (c) the fixing of a maximum age for recruitment which is based on the training requirements of the post in question or the need for a reasonable period of employment before retirement.”

Article 6(2) provides that an occupational pension scheme, in itself, may discriminate on grounds of age:

“ ... Member States may provide that the fixing for occupational social security schemes of ages for admission or entitlement to retirement or invalidity benefits, including the fixing under those schemes of different ages for employees or groups or categories of employees, and the use, in the context of such schemes, of age criteria in actuarial calculations, does not constitute discrimination on the grounds of age, provided this does not result in discrimination on the grounds of sex.”

What is notable about this exception, is that discrimination need not be justified. Occupational pension schemes are ring-fenced from the Directive. However, Article (2) does not legitimise dismissal, or retirement per se, although of course, an age-discriminatory pension scheme may form the background to justifying a dismissal. Finally, Recital 14 of the preamble, states: “This Directive shall be without prejudice to national provisions laying down retirement ages.”

3. Default Retirement Age

On 14 December 2004, the Government announced that it will introduce a “default” retirement age of 65, enabling employers to dismiss workers reaching that age on the ground of retirement, without objective justification. This was qualified with an aspiration to abolish the default age after 5 years:

“Ultimately

we look forward to a future where people have complete choice about when to

stop working, and retirement ages become a thing of the past. If the formal

review of the legislation suggests that we should abolish compulsory retirement

ages, then that is what we will do.”

(Written statement to Parliament, House of Commons Hansard Written Ministerial

Statements for 14 Dec 2004 (pt 4), Columns 127WS-130WS; or Lords Hansard Text

for 14 Dec 2004 (241214-41), Colums WS78-WS81. See also, ‘Equality and diversity:

coming of age. Consultation on the draft Employment Equality (Age) Regulations

2006’ (July 2005) DTI, URN 05/1171, at para 6.1.24.)

Regulation 30 provides the exception for retirement, whilst Schedule 6 provides a “right to request” deferred retirement procedure and Schedule 8 adds sections 98ZA to 98ZH to the Employment Rights Act 1996, with provisions necessary to protect employers from unfair dismissal claims in cases of retirement.

Should employers agree to keep on a worker beyond 65, save for retirement, the general principle against age discrimination will apply. So, for instance, discriminatory discipline, pay, harassment, and job classification would remain unlawful.

This arrangement has necessitated some delicate and convoluted drafting to avoid two clashes with the parent Directive. First, it must not breach the Directive’s non-regression principle. Second, the Directive does not appear to grant Member States a blanket derogation, and so it will have to be justified under Article 6(1).

A. Non-regression and Unfair Dismissal

Any Government measure may be attacked under the non-regression principle, expressed in Article 8, if the Directive is used to reduce protection against discrimination. The obvious area of concern here is the existing age restrictions to unfair dismissal rights, where section 109, Employment Rights Act 1996 (ERA 1996) excludes from claiming unfair dismissal, those over the employer’s “normal retiring age”, or in the absence of that, 65. This has allowed, for instance, police officers and teachers to negotiate for retirement well below 65, which is normally coupled with an occupational pension. Where the normal retiring age is above 65, unfair dismissal rights will apply right up to that normal retiring age; the “default” age in section 109 ERA 1996 does not prevail over the normal retiring age (Nothman v Barnett LBC [1979] ICR 111, HL, at 116.) Where the employer’s normal retiring age is a sham, the statutory age of 65 will apply. (Whittle v MSC [1987] IRLR 441 EAT, where 90per cent stayed beyond the contract retiring age of 60. See also May v Harrison (2003) UKEAT/0128/03/ZT, EAT.)

Beyond that, the law becomes complex. The “normal retiring age” is not found by a strict contractual test, but by the “reasonable understanding or expectation of the employees holding that position at the relevant time.” (Waite v GCHQ [1983] ICR 653 HL, per Lord Fraser, at 662-663.) Thus it is possible for a worker’s contractual retiring age to differ from his normal retirement age. (Although the normal retiring age cannot be lower than the contractual retiring age: Bratko v Beloit Walmsley Ltd [1995] IRLR 629 EAT.) Difficulties arise when an employer tries to change the normal retiring age. Of course, there is no problem where the change is agreed. Further, the courts will allow an employer unilaterally to change the normal retiring age, so long as this does not amount to a breach of contract (Waite v GCHQ [1983] ICR 653 HL). This is possible where, for instance, the contractual retirement age is 60, but in practice the employer retires its staff at 65. Here the employer is free to reduce its workers’ normal retiring age (and with it their unfair dismissal rights) to as low as the contractual one of 60 (Brooks v BT [1992] ICR 414 CA, at pars 35 and 45).

So an agreement to reduce the normal retiring age (be it contractual or not) from, say, 70 to the default age of 65, will not reduce workers’ age discrimination rights to below that which existed before the Directive. A similar reduction imposed by the employer, which is not in breach of contract, similarly will not reduce its workers’ rights. However, as the law stood before the Directive, an employer cannot impose a reduction which amounts to a breach of contract, for example, where the normal and contractual retirement age is 70, and the employer reduces it to 65. In such a case, the workers’ unfair dismissal rights remain up to the age of 70 (Bratko v Beloit Walmsley Ltd [1995] IRLR 629 EAT.)

Therefore the Directive does not permit the Government to legislate for a default retirement age that authorises employers unilaterally to reduce their normal retiring age where this is in breach of contract. The default retirement age then becomes confined to those employers who had never set a normal retiring age, but in practice dismiss those aged 65, as permitted by the unfair dismissal “default” age in section 109, ERA 1996. The major impact will be on those approaching 65, who held a reasonable expectation that the Directive would give them the right to carry on working. This was encouraged, not least, by the Government’s previous announcement of a default retirement age of 70 (Equality and Diversity: Age Matters (2003), DTI/Pub 6559/10k/06/03/NP. URN 03/20, 2003; pp 20, 25 para 4.25, 32 para 5.8).

Schedule 8, paragraph 23 amends the Employment Rights Act by inserting sections 98ZA-98ZH, which exclude from the unfair dismissal provisions a variety of retirement scenarios. First, where the is no normal retirement age, a worker cannot be retired before aged 65 (s 98ZA), but can be afterwards (s 98ZB). Second, where there is a normal retirement age, a worker cannot be retired before that normal retirement age (s 98ZC), but can be afterwards (s 98ZD). Where the normal retirement age is below 65, section 98ZE(2) cryptically provides that “If it is unlawful discrimination under the 2006 Regulations for the employee to have that normal retirement age, retirement of the employee shall not be taken to be the reason (or a reason) for dismissal.” Presumably this alludes to the scenario where the employer cannot objectively justify its normal retirement age, which, being under 65, is prima facie direct age discrimination. Where the normal retirement age is lawful (it has been justified), then a worker may be retired accordingly. For these exclusions to apply, the employer must have followed the procedures (notification, consideration of the request not to retire, and subsequent appeal) set out in Schedule 6 of the 2006 Regulations (see below).

It appears from this that an employer can unilaterally move its normal retirement age as before. The legislation does not expressly state whether this cannot be done below any contractual retirement age but in the absence of an express provision, and bearing in mind that such a provision would breach the non-regression principle, the presumption must be that the common law position persists.

B. Blanket Derogation and Recital 14

Such a broad exception appears to fall short of a proper implementation of the Directive. The only part of the Directive that supports a blanket derogation is Recital 14 of the preamble. However, if this recital does not validate the default retirement age, the Government would be bound to justify it under Article 6(1). So, much turns on the precise meaning of Recital 14.

The history of the legislation is inconclusive on this matter. It shows that the UK Government pressed for age to be given a unique status in discrimination law, by proposing the following recital regarding derogation:

“Age has a special

status in that certain differences of treatment on age in employment practices

are legitimate; such differences may vary across Member States in the light

of their constitutions, traditions and practices and their labour market conditions;

it is therefore essential to distinguish between legitimate differences and

discrimination which must be prohibited.”

(Proposal for a Council Directive establishing the general framework for equal

treatment in employment and occupation - political agreement, 12270/00 ADD

1 (12 October 2000).)

Accordingly, the UK proposed a new Article 6(1): “Member States shall define those differences of treatment which constitute discrimination for the purposes of Article 2.” (Ibid) Although a list of some “differences in particular”[1] was proposed in a new Article 6(2), Article 6(1) provided essentially an unlimited exception, without justification, which could include a national default age.

These proposals were rejected. The final version contained a conventional definition of discrimination for age (Article 2), with the ordinary exception for determining occupational requirements (Article 4(1)), and the extraordinary Recital 14 and Article 6. This suggests, on the one hand, the UK intended a default retirement age to be permissible, whilst the other States did not. It also suggests, albeit less convincingly, that the rejection of the UK’s original proposals, and the acceptance of Recital 14, amounted to a compromise, by which all exceptions, bar a national retiring age (and pension scheme ages), had to be justified. But it remains odd why the retirement exception was isolated in the preamble. Thus, the history sheds little light on the true meaning of the recital.

So we turn to a reading of the face of the Directive. The most obvious problem is that Recital 14 conflicts with the fundamental principle of equal treatment stated in Article 2(1), which states that there “shall be no discrimination whatsoever” on the grounds set out. (Emphasis supplied. The phrase is used in the Equal Treatment Directive (Art 2(1)), but oddly, “whatsoever” does not appear in the Race Directive 2000/43, the Equal Pay Directive 75/117, nor Articles 39 (nationality) or 141 (equal pay) EC Treaty.) Further, if the recital were read as a free-standing exception, ECJ jurisprudence suggests that such exceptions must be “interpreted strictly”, “in view of the fundamental importance of the principle of equal treatment.” (Marshall v Southampton and SW Hants AHA Case C-152/84 ECJ, [1986] IRLR 140, at 148.) A strict interpretation is unlikely to yield a blanket omission from protection of a large class of people who are the most vulnerable to age discrimination. A reading of some other recitals helps a little. Recital (4) reminds us that the right against discrimination is “universal”, suggesting a group (ie those over a certain arbitrary age) should not be excluded from the protection of the Directive. Recital (11) states that discrimination on any of grounds protected “may undermine ... the objectives of the EC Treaty”. Recital (7) states that one objective of the EC Treaty is to achieve “coordination between employment policies of Member States”, whilst Recital (8) stresses “the need to pay particular attention to supporting older workers” with a “coherent set of policies”. These suggest that Recital 14 should not give excessive latitude to Member States.

Meanwhile, other exclusions mentioned in the preamble have corresponding paragraphs/provisions in the main body. So Recitals 12 (nationality), 13 (state social security schemes), and 19 (disability and age in the armed forces), serve to amplify the exclusions allowed by, Article 3, paragraphs 2, 3, and 4, respectively. There is no such corresponding Article (suggesting a default retirement age) to Recital 14. If anything, Recital 14 appears to amplify Article 3(3), which relates to state social security schemes, which of course, may have retirement age factors built in. (Although it must be noted that Article 3(1) seems to be amplified adequately by Recital 13.) Further, there are two specific age-discrimination exceptions contained in the main text, provided by Article 6. It would be anomalous to put a third exception in preamble. All this points to the Recital having little meaning, and certainly not one allowing a blanket retiring age.

The deciding factor must be that if Recital 14 were read to permit a blanket default retirement age, it would be incompatible with the substantive text of the Directive, especially the fundamental principle of equal treatment in Article 2. In which case, the rule is “... the preamble to a Community act has no binding legal force and cannot be relied on as a ground for derogating from the actual provisions of the act in question.” (Gunnar Nilsson, Per Olov Hagelgren and Solweig Arrborn Case C-162/97, 1998 ECR I-7477, ECJ, at para 54. See also Opinion of A-G Tizzano in R v Sec of State for Trade and Industry ex p BECTU C Case-173/99 [2001] ECR I-4881, at para 39.) Accordingly, the Government could not argue that is free to legislate for a default retirement age. Such legislation can only be made under Article 6(1), and so must be objectively justified.

C. Objective Justification

If the Recital cannot be used for a default age, the Government would be bound to justify any default age as being in pursuit of a legitimate aim, appropriate and necessary, in accordance with Article 6(1) of the Directive. The Government stated that a major reason why employers will wish to take advantage of the default retirement age would be to preserve the “stability” of their occupational pension plans. In addition, the impact of the exception may be softened by an employer’s “duty-to-consider” a request for deferred retirement. This needs to be explored, to establish more precisely the impact of the exception, before considering the “pensions stability” claim.

Part of an argument to justify the default retiring age would be that its indiscriminate effect is softened by giving employees a “right to request” deferred retirement, apparently along similar lines to right of parents of young children to request flexible working. (Written statement to Parliament, House of Commons Hansard Written Ministerial Statements for 14 Dec 2004 (pt 4), Columns 127WS-130WS; or Lords Hansard Text for 14 Dec 2004 (241214-41), Colums WS78-WS81.)

Section 80F, ERA 1996, gives an eligible employee a right to request flexible working. The employer may refuse a request if “he considers” one or more of specified grounds applies. These grounds are: (i) the burden of additional costs, (ii) detrimental effect on ability to meet customer demand, (iii) inability to re-organise work among existing staff, (iv) inability to recruit additional staff, (v) detrimental impact on quality, (vi) detrimental impact on performance, (vii) insufficiency of work during the periods the employee proposes to work, (viii) planned structural changes. (ERA 1996, s 80G (b)). The employer also must provide an explanation (SI 2002/3207, Reg 5(b)(2)). An employee may complain to an employment tribunal only if the decision is based on “incorrect facts” (ERA 1996, s 80H (1)(b)) or the employer has not followed the prescribed procedure (ERA 1996, s 80H (1)(b), and SI 2002/3236). The subjective element “he considers” means the employee cannot challenge the business ground(s) given by the employer. The remedy is compensation capped to a maximum of eight weeks’ pay, with a week’s pay itself capped at £290. (Employment Rights (Increase of Limits) Order 2005, SI 2005/3352, Sch, Article 3, in force 1 Feb 2006. It is set by the Secretary of State each year according with retail prices.)

Schedule 6, paragraph 2, of the Age Regulations provides that the employer must give notice in writing of the employee’s right to make a request and the date on which it intends the employee to retire, not more than one year and not less than six months before that date. Paragraphs 3 to 9 provide , in essence, following an employee’s request, the employer should hold with him a meeting (at which the employee may choose to be accompanied), or at least receive from him representations. If the employer wishes to go ahead with its decision to retire the employee, it must confirm this in writing. The employee has a right to appeal. The remedy for dismissal without following the procedure is unfair dismissal (ERA 1996, s 98ZG.), although this does not apply if the employee was prevented from being accompanied. (In which case the remedy is a maximum of two weeks pay, capped at £290 per week: Age Regulations, 2006, Sch 6, para 12, and SI 2005/3352, Sch, Article 3, in force 1 Feb 2006.) However, only a failure to comply with the notice procedure takes the dismissal out of the retirement exemption, enabling the victim to claim discrimination.

This duty-to-consider deferred retirement is less onerous that the duty associated with the right to request flexible working, principally because the employer need not provide a reason for its decision. The Government hope that the procedure will “promote a culture change ... and move to a position where fixed retirement ages are relied on only where they can be objectively justified.” (‘Equality and diversity: coming of age. Consultation on the draft Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006’ (July 2005) DTI, URN 05/1171, at para 6.3.8.)

Whilst this may result in a reconsideration in a few cases, it is hard to imagine it justifies the enormous amount of bureaucracy imposed by the convoluted procedure laid down by Schedule 6, which imposes no duty of substance on the employer. So long as employers follow the procedure, they may retire its workers at will.

This scheme would have to undergo major changes genuinely to soften the impact of the national default retirement age. First, and most obviously, there would need to be different, legitimate, grounds for refusal. In this context, one of which would have to be the prevention of adverse consequences for occupational pension schemes. Second, except for the notice requirement, the remedy for dismissal without the procedure is limited to unfair dismissal, where compensation is capped at £58,400 (SI 2005/3352, Schedule, in force 1 Feb 2006.) In Marshall v Southampton & SW AHA (No 2) Case C-271/91, ECR I-4367, at para 32, the ECJ held that the equivalent Art 6 in the Equal Treatment Directive 76/207 made upper limits on compensation for sex discrimination unlawful. Thus this cap is likely to breach Article 9, which requires member states to provide a judicial process for victims of discrimination.

To accord with the Directive the proposed “right to request” would have to be broadened so much it would bear little resemblance to its supposed counterpart for flexible working. If it were so broadened, it would put the employer in a position of having to justify each individual retirement. This then shifts the national default retiring age into the same class as any individual employer’s retiring age. In other words, the default retirement age loses any distinguishable meaning. This conclusion means any meaningful “right to request” cannot justify the default retirement age.

4. Justification and Occupational Pensions

The second possible justification, and one put forward by the Government, relates to the stability of occupational pension schemes. In a Written Statement to Parliament, the Government justified the default age because:

"... significant numbers of employers use a set retirement age as a necessary part of their workforce planning. While an increasing number of employers ...[have] no set retirement age for ... their workforce, some nevertheless still rely on it heavily.

Furthermore, ... if all employers only had the option of individually justified retirement ages at the time the legislation was introduced, this could risk adverse consequences for occupational pension schemes and other work related benefits. Some employers would instead simply reduce or remove benefits they offer to employees to offset the increase in costs.”

(See note 1. Column 128WS. In its press release on the same day, the Government stated that there was ‘a danger that, without [a default age] ... there could be adverse consequences for occupational pension schemes and other work-related benefits.’ DTI Press Release 14th December 2004. See www.dti.gov.uk/pressroom/index.html. See also ‘Equality and diversity: coming of age. Consultation on the draft Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006’ (July 2005) DTI, URN 05/1171, at para 6.1.15.)

Clearly one major concern is the consequences on pension schemes. As seen above, Article 6(2) of the Directive has provided that the pension scheme, in itself, may discriminate on grounds of age. This, unlike Article 6(1), does not require the derogation to be justified. So claims for direct or indirect age discrimination by the pension scheme are not possible. But Article 6(2) cannot be used, in itself, to justify age-related dismissal, or retirement. So the issue remains that the default retirement age must be justified, according to the “legitimate aim by appropriate and necessary means” rubric, provided by Article 6(1). What follows is an explanation of the operation and coverage of occupational pensions, the Canadian experience, and the likely result should a challenge be defended on the ground of preventing “adverse consequences” on pension schemes (the “occupational pensions” defence).

A. Occupational Pensions in the UK

There are two main types of occupational pension schemes: the defined benefit (DB) scheme and the defined contribution (DC) scheme. Although there are a number of hybrid schemes that combine the features of both DB and DC schemes, DB schemes still account for 89 per cent of scheme members (National Association of Pension Funds (2003) Annual survey of occupational pension schemes, NAPF, London).

With a DB scheme, it is the pension benefit that is defined. In the UK most DB schemes are known as occupational final salary schemes, since the pension is some proportion of final salary, where the proportion depends on years of service. A typical scheme in the UK has a benefit formula of one-sixtieth of final salary for each year of service up to a maximum of 40 years’ service, implying a maximum pension of two-thirds of final salary, with the pension indexed to inflation to a maximum of 5 per cent per annum. In the public sector one eightieth is more common, but members accrue a lump-sum benefit in addition to their pension, so that the overall rates of accrual are similar. In addition to the pension most final salary schemes provide extra benefits, for example, death-in-service and early retirement benefits.

In a DC scheme, what is defined is the contribution rate into the fund, for example, 10per cent of earnings, and the resulting pension depends solely on the size of the fund accumulated at retirement. Such schemes are also known as money purchase schemes and in the UK they are better known as personal pension schemes. The accumulated fund must be used to buy a life annuity from an insurance company, although up to 25 per cent of the fund can be taken as a tax-free lump sum on the retirement date. In 1995, as a result of falling interest rates, the UK government was pressed into allowing income drawdown (meaning you can take certain amounts from your pension between the ages of 50 and 75): it became possible to delay the purchase of an annuity until annuity rates improved (or until age 75 whichever was sooner).

Usually employees are expected to contribute about 5 per cent of pay to a DB occupational scheme while the employer meets the “balance of the cost”. In 2002, employers on average contributed about 12 per cent of pay to DB schemes (National Association of Pension Funds (2003) Annual survey of occupational pension schemes, NAPF, London). In theory, the employer has an open-ended commitment to the pension scheme. The financially significant risks are from lower than expected investment returns and increasing longevity. An employer might be expected to make additional contributions to meet any shortfall in assets relative to liabilities. To a certain extent the employer can control this cost either by limiting salary growth or by closing the scheme. Since 2003, solvent employers have been obliged to pay to buy out defined benefit liabilities if they wind up a scheme, making it unlikely that many employers would pursue this course lightly.

During the 1950s and most of the 1960s the number of people in occupational pension schemes grew rapidly to reach about half the number of employees in employment, at which level it has broadly remained (see Figure 1). Since the early 1990s no company has set up a DB scheme and an increasing number of companies are closing DB schemes to new employees in favour of DC schemes (The Economist (2002) “End of the party”, 2 March, p 37). In so far as DB schemes constitute all public sector pension schemes and all large and very large schemes in the private sector (GAD (2005) Occupational pension schemes 2004 – The twelfth survey by the Government Actuary, London: The Government Actuary’s Department) their closure is having a downward impact on the number of active members of occupational pension schemes in the private sector (Figure 1). Furthermore, where DB schemes are offered by employers their membership cannot be made a condition of employment. (Membership could be made a condition of employment until 1987, when compulsory membership was prohibited under the 1986 Social Security Act.)

Figure 1 Number of active members of occupational pension schemes

Source: Eleventh Survey by the Government Actuary Department 2003

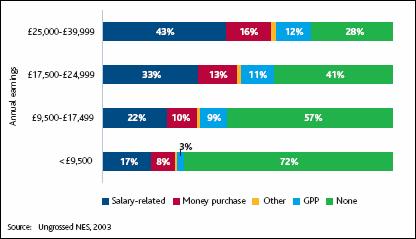

Current coverage of pension schemes is not universal, and decreases further down the income distribution scales. As shown in Figure 2, of those earning between £25,000-39,000 only 28 per cent have no private pension coverage; this increases to 72 per cent of those earning less than £9,000. Put another way, those with higher earnings are much more likely to be members of an occupational pension scheme with 82.1 per cent of those in the highest earning, ten percent of the population, having either an occupational pension scheme or an occupational pension and a personal pension. (Disney and Emmerson 2002)

Figure 2: Participation in private sector employer-sponsored schemes, by earnings band (2003)

Source: Turner (2004) Pensions: Challenges and choices – The first report of the Pensions Commission

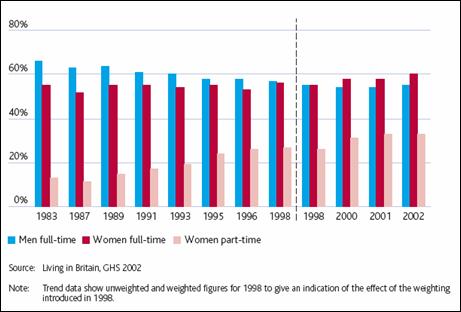

Pension coverage is traditionally highest among men who work full-time as shown in Figure 3. Between 1983 and 2002 there was an 11 per cent drop in the percentage of full-time men who are members of employers’ pension schemes. The trend in proportions of women employees who are members of employers’ pension schemes has been changing since 2000 with women who work full time having a high propensity of belonging to an occupational pension scheme. Women working part-time, however, still have the lowest coverage.

Figure 3: Percentage of employees that are members of current employer’s pension scheme, by sex and full-time/part-time status

Source: Pensions Commission (2004) Pensions: Challenges and choices – The first report of the Pensions Commission

Amongst ethnic minority groups, both men and women are less likely to have private pension coverage than their white counterparts. The extent of the difference is most marked for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis. (Ginn and Arber 2001)

The pension commission report attributes this to economic inactivity rates of the two groups, higher unemployment and self-employment rates particularly amongst Pakistanis, and patterns of employment of Bangladeshis. (Pensions Commission (2004) Pensions: challenges and choices - the first report of the pensions commission, TSO, London. No general table available for breakdown.) Therefore occupational pension membership is not inclusive of all employees and the data presented in Figure 3 is not representative of the whole working population, in 1995 only 46per cent of the working population were members of occupational pensions. (GAD (2001) ‘Occupational Pension Schemes 1995, Tenth Survey by the Government Actuary’, London: The Government Actuary’s Department.)

B. Occupational Pensions and the Canadian Experience

The Government may take some encouragement from a decision of the Canadian Supreme Court, where the total exclusion of those over 65 from age discrimination protection within section 9(a) of the Ontario Human Rights Code, 1981, was unsuccessfully challenged as being contrary to Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In McKinney v University of Guelph [1990] 3 SCR 229, several university academics claimed that inter alia, section 9(a), Ontario Human Rights Code 1981, which excluded those aged over 65 from protection under the Code’s age discrimination law, violated the non-discrimination tenet in section 15(1) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Supreme Court of Canada, by a majority of five-to-two, rejected their claim, principally on the basis that a general retirement age of 65 was necessary to preserve the stability and integrity of pension schemes. There are significant parallels between this case and a challenge made to the UK Government’s default retirement age.

Section 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms provides:

“Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

Section 1(1) of the Charter provides that a discriminatory law may be justified:

“The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

The Supreme Court has developed a two-part test of justification, often referred to as “the Oakes test”, following its inception in R v Oakes [1986] 1 SCR 103. In Andrews v Law Society of British Columbia [1989] 1 SCR 143, the Court expressed it thus (at 153-155):

“The first hurdle to

be crossed in order to override a right guaranteed in the Charter is that

the objective sought to be achieved by the impugned law must relate to concerns

which are ‘pressing and substantial’ in a free and democratic society.

Second, the means chosen to attain those objectives must be proportional or

appropriate to the ends. The proportionality requirement, in turn, normally

has three aspects: the limiting measures must be carefully designed, or rationally

connected, to the objective; they must impair the right as little as possible;

and their effects must not so severely trench on individual or group rights

that the legislative objective, albeit important, is nevertheless outweighed

by the abridgment of rights.” (Citing R v Edwards Books and Art Ltd

[1986] 2 SCR 713, at 768.)

This roughly equates to the Directive formula. The first part compares to the “legitimate aim”. The second “proportionality” part, encompasses the appropriate means (“rationally connected”) and the necessary means (“minimal impairment”), whilst in addition, it requires the defendant to weigh the objective against the discriminatory effect of the measure.

“In the view of these scholars, the repercussions of abolishing mandatory retirement would be felt ‘in all dimensions of the personnel function: hiring, training, dismissals, monitoring and evaluation, and compensation’. These authors observed:

‘In short, a number of issues regarding the design of occupational pension plans would have to be addressed if mandatory retirement were not permitted. So, too, would the wage policy followed by many employers, especially when the pension benefit is linked to the employee’s earnings. The use of the occupational pension plan as a vehicle for deferring a portion of the employee’s total compensation to the employee’s later work years may be reduced. As before, not permitting mandatory retirement is likely to require compensating adjustments elsewhere in the compensation package and in the set of work rules that govern the workplace.’

In tinkering with mandatory retirement, we are affecting an institution closely intertwined with other organizing rules of the workplace.”

The plaintiff’s expert confined his evidence to effect upon pension plans of removing the MRA. He highlighted the experiences of Quebec and Manitoba, where the MRA was removed and no “instability” was apparent in the pension plans as a result. He testified that deferred retirement would invoke some administrative costs for actuarial adjustments, which would “pale into insignificance compared to administrative costs resulting from pension legislation.” Second, he noted that the removal of the MRA did not necessarily alter the normal retiring age in the pension plan. In Quebec and Manitoba, for example, legislation requires that a normal retiring age be stated in the pension plan. (Affidavit of Peter C. Hirst, Case on Appeal Vol 7, Tab 2, respectively paras 11 and 14.)

Before applying the justification test, the majority noted that age differed from other grounds of discrimination. First, because “There is a general relationship between advancing age and declining ability” Second, discrimination on other grounds is “generally based on feelings of hostility and intolerance.” This should “neutralise” any suspicion of laws that discriminate on the ground of age ([1990] 3 SCR 229, at 297). This is demonstrated in case law. In Law v Minister of Pensions [1999] 1 SCR 497, a state pension scheme that reduced payments to widows under 45 years of age was held not even to infringe section 15 of the Charter, because this difference in treatment on the ground of age did not violate “the essential human dignity and freedom” of the claimant (para 106). Contrast Andrews v Law Society of British Columbia [1989] SCR 143, where a citizenship requirement to practise law could not be justified under section 1 of the Charter, because it was “not carefully tailored to achieve that objective and may not even be rationally connected to it”; it could be better achieved by an examination of the particular qualifications of the applicant (at 156). Similarly, the US Supreme Court has held that age discrimination does not warrant heightened (as for race) or intermediate (sex) scrutiny under the Constitutional principle of equal protection of the laws, because, older people have not experienced a “history of purposeful unequal treatment or been subjected to unique disabilities on the basis of stereotyped characteristics not truly indicative of their abilities.” Massachusetts Board of Retirement v Murgia, 427 US 307, at 313 (Sup Ct 1976)). In any case, the comments in McKinney set the tone for the scrutiny, suggesting that it would be less stringent than for other grounds of discrimination.

The majority considered that the main objective was the “integrity” of the pensions system, additionally noting the importance of the freedom of employers and workers to contract for a MRA, and the concerns of workers who wished to take advantage of the normal retiring age and accompanying benefits. These were pressing and substantial objectives, whilst The object of reducing Canada’s youth unemployment “should not be accorded much weight.” ([1990] 3 SCR 229, at 302.)

The majority, without lengthy explanation, found that the legislation “obviously achieves” the main objective (of “stability in pension arrangements”) and was therefore rationally connected to that goal.

On the second, “minimal impairment” point, the majority noted the “permissive” nature of section 9(a); the Ontario Legislature is “not imposing its will in the area” of mandatory retirement, which is negotiated by employers and workers in the private sector. Indeed the Canadian labour movement favoured a mandatory retirement age of 65 (at 312-313).

The majority were, on this point, heavily influenced by the evidence of Gunderson (above) that stated that if the MRA were removed a whole raft of established employment practices would unravel. Such decisions over this, and any conflicting economic evidence, should be left to the Legislature - which should have “reasonable room for manoeuvre” (at 314-315) - and not the “heavy hand of the law.” (Per Sopinka, J, ibid, at 316.)

A second issue of minimal impairment raised was that section 9(a) was not proportionate (or had “overbreadth”) because it removed all age discrimination rights for those over 65, and thus went further than necessary merely to retain MRA. Workers kept on beyond 65, could suffer discrimination without redress. The majority was dismissive of this, calling the argument “a fussy concern”, although it noted that age related harassment was covered by a general provision against harassment. Otherwise the argument was “fanciful.” (At 315-316.)

On the third, “Objective v Abridgement of Rights” point, the majority noted that section 15(2) of the Charter allowed for positive discrimination in certain circumstances (which disadvantages certain groups to achieve a goal), so section 1 envisages some circumstances where certain groups will be disadvantaged in pursuit of a greater goal (at 317). Finally, as the Charter expressly does not apply to private matters, it would be wrong to allow it to operate through the “back door” to bind private employers (at 318).

In summary, the majority allowed the legislature “reasonable room for manoeuvre”, deferred to it where economic/expert evidence clashed, and was highly influenced by Gunderson’s evidence of the interconnection of the MRA with pensions and other established employment practices.

As noted above, the general approach to age discrimination was less stringent than the Supreme Court would take for other grounds of discrimination. In particular, the Court gave the Legislature “room for manoeuvre,” which resembles the “margin of appreciation” given by the European Court of Human Rights to defendant states, or the margin of discretion given by the ECJ to Member States trying to justify indirect discrimination (eg Handyside v UK (1976) 1 EHRR 737, and see generally, O’Donnell 1982; Morrisson 1973. Note that this discretion “cannot have the effect of frustrating the implementation of a fundamental principle of Community law such as that of equal pay for men and women.” R v Secretary of State for Employment ex p Seymour-Smith and Perez Case C-167-97 [1999] 2 CMLR 273, [2000] ICR 244, at para 75.)

However, the ECJ affords Member States no such margin of discretion in cases of direct discrimination: any infringement must be justified within specific derogations provided in the relevant Directive. (Johnston v Chief Constable of the Royal Ulster Constabulary Case C-222/84 [1986] ECR 1561, [1987] QB 129, paras 53, 57 and 60; Maria Luisa Jimenez Melgar v Ayuntamiento de Los Barrios Case C-438/99 2001 ECR I-6915, at para 33.) For direct discrimination, these are usually specific job-related exceptions, where the ground of discrimination (eg sex or race) is a “genuine and determining occupational requirement”. (See eg Race Directive 2000/43/EC, Art 4. Equal Treatment Directive, 76/207/EC, Art 2(6).) In addition, the exception must be proportionate. The same job-related exception is available for age discrimination by employers, under Article 4(1) of the Framework Directive. Of course, this cannot be used by a State to justify a default retirement age which will be applicable to all jobs, no matter what the occupation. But the Directive does offer the State a broad scope to discriminate, on the ground of age only, by Article 6, which represents the EU’s “less stringent” approach to age discrimination seen in McKinney. Article 6 is non-specific, allowing age discrimination where it can be justified in pursuit of a “legitimate aim”. Some examples are offered, such as an employment policy, but they are non-exhaustive. However, Article 6 also contains the standard proportionality rubric, and the difference between this and the Canadian Supreme Court’s approach is likely to be in the strictness of the application of the “proportionality” question. ECJ case law on discrimination suggests a very strict approach.

The first thing to note is that a default retirement age is a more refined exception than Ontario’s crude exclusion of all age discrimination rights for those over 65. Under the Government’s proposal, workers over 65 will still be able to claim for age discrimination, for say, discriminatory discipline, pay, harassment and job classification. This makes it easier to justify the measure.

However, whereas the majority in McKinney found this proportionality argument “fanciful,” ([1990] 3 SCR 229, at 315-316) they failed to address other issues of proportionality. Whilst they appreciated the freedom to contract for a MRA, a freedom supported by trade unions, they did not appreciate the workers who do not have occupational pensions, collective bargaining, and all the other benefits and practices noted. Further, it is probably the case that these workers are the poorest, being women in segregated occupations or immigrants (noted in the dissent of Wilson, J, at 415-416). The rights of those workers were subjugated for the benefit of those in far more secure and better-paid employment.

The objection to private application by the “back door” does not apply in Britain. Unlike the Canadian Charter, the Directive, through each Member State, is intended to bind state and private employers to the equal treatment principle. Thus, no such argument should be presented here.

The Canadian Court showed a good deal of deference to the provincial legislature that passed the disputed law, stepping back from what it saw as quasi-political decision-making, or using the “heavy hand of the law”. Again, this contrasts with the position in the UK. Although the Directive allows each Member State to achieve the goals of the Directive in its own way, any shortfall of the Directive’s aims and principles in this transposition are treated seriously by the ECJ. For instance, the original section 6(3) of the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 provided exceptions in all cases where the number of employees did not exceed five, and also where the employment was for the purposes of a private household. These exceptions were held to be contrary to the Equal Treatment Directive (Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom Case 165/82 [1984] ICR 192.) The ECJ reasoned that in small undertakings it was not always the case that the sex of the worker would be an occupational determining factor, for the purposes of the exception provided by Article 2(2) of the Directive. Similarly, the blanket exception for private households was too general. The householder’s privacy should be just one factor in a decision. In other words, section 6(3), was disproportionate. No deference was given to the UK parliament that had passed the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. The 1986 Sex Discrimination Act therefore repealed the provisions held unlawful by the European Court and introduced a new s 7(2)(ba) to the 1975 Act which is couched in more restrictive terms.

For two reasons the ECJ should not take the “less stringent” approach to age discrimination demonstrated in McKinney. First, leeway is already given by the special provision in Article 6. This indicates that the Directive itself has accounted for any distinctive characteristics of age discrimination. The leeway given by Article 6 does not signal that courts should adopt a less stringent approach. This is because Article 6 is clearly defined. This is especially so with article 6(1), which carries the standard formula for justification. Second, the ECJ has shown little sympathy for benign-motive discrimination (see eg Johnston v Chief Constable of the Royal Ulster Constabulary Case C-222/84 [1987] QB 129, especially paras 53, 57 and 60; Maria Luisa Jimenez Melgar v Ayuntamiento de Los Barrios Case C-438/99 2001 ECR I-6915, at para 330), whereas the majority in McKinney clearly took the view that as age discrimination was not “generally based on feelings of hostility and intolerance,” they were entitled to adopt a less stringent approach (([1990] 3 SCR 229, at 297). This difference of approach can be explained, in part at least, by the different roles of the respective courts. The Canadian Supreme Court was acting as a guardian of the individuals’ constitutional rights against the state, whereas the ECJ will be overseeing an individual’s employment rights, which are more precisely defined. This was demonstrated in the first age discrimination case to reach the ECJ, Mangold v Helm Case C-144/04, [2006] IRLR 143. Here, German law exempted from regulation fixed-term employment contracts for any worker over 52. The purpose was to help unemployed older workers back to work. The ECJ held that the German Government should have a “broad margin of discretion” to implement this social policy, but as it was not tailored for those unemployed older workers it could not be deemed “necessary” to achieve the goal. This shows that the ECJ will take the same approach to age discrimination as it does to any other ground, and is in marked contrast to the Canadian Supreme Court’s approach.

C. The “Occupational Pensions” Defence

Although the issues in McKinney resemble a challenge to a default retirement age, there are important differences. First, the ECJ will take a more stringent approach to justification of age discrimination and will not show such deference to the UK Parliament. Second, there were a number of disproportionate features to the Ontario Human Rights Act’s exception, which the majority swept aside, or failed to consider at all. These factors would each be taken seriously by the ECJ, as shown in Mangold. The only difference in the Government’s favour is that the default retirement age is more refined than the sweeping denial of all age discrimination rights to those over 65, although, as we shall see, this does not prevent the default retirement age’s other disproportionate effects.

The impact of the age discrimination principle absent a default retirement age on pension schemes generally will the same with DC and DB pensions (see above ‘A. Occupational Pensions in The UK’). It is anticipated that the normal retirement age (NRA) of pension schemes will rise to 65 based on evidence presented by the Government Actuary Department indicating an increase in pension schemes’ NRA since 1985. (GAD (2001) ‘Occupational Pension Schemes 1995, Tenth Survey by the Government Actuary’, London: The Government Actuary’s Department.) Pension schemes with a NRA of 65 or above are more cost effective for employers and therefore more sustainable. And new Inland Revenue proposals allow employees to carry on working for their employers beyond the NRA of both DB and DC pension schemes.

There are two possibilities: Some workers will draw their pension at the scheme’s NRA and carry on working. This option will have no more impact than the worker who simply retires and draws the pension. Other employees may work beyond 65 and defer drawing their pension until they wish, simply providing more years’ contribution. Here a scheme’s stability is not affected because individuals will be contributing for longer and drawing their pensions for a shorter number of years.

However, there is a negative effect of the default retirement age on minorities and women. Membership of pension schemes is skewed towards male workers on above-average income. Employees of low income, ethnic minorities and, to a lesser degree, women are less likely to be in occupational pensions (see Figure 3, above). This pension disadvantage implies dependence on means-tested benefits and poverty in later life especially as government policy shifts towards private sector pension provision. (Ginn and Arber 2001) Age discrimination legislation without the default retirement age entitles this category of employee to remain in the labour market, in order to boost a low income. The default retirement age disentitles them from doing this.

This evidence shows that the default retirement age is not an appropriate method to preserve the stability of pension schemes because the age legislation absent the default retirement age will have no adverse effects on DC or DB pensions schemes, whether drawn or deferred. Further, it is a disproportionate method because a significant proportion of workers affected by the default retirement age do not have occupational pensions, and yet have their discrimination rights removed for the benefit of others. This is aggravated by the fact that this category contains a disproportionate amount of the low-paid, ethnic minorities, and (to a lesser degree) women. Thus the default retirement age struggles to look like an appropriate or necessary means of preserving the stability of occupational pensions.

5. Justifying Retirement Under 65

Article 6(1) (set out above), permits Member States to legislate for a “legitimate aim” including employment policy and labour market objectives. Regulation 3 of the Age Regulations 2006 defines direct and indirect age discrimination and carries a common defence of objective justification. Thus, unlike other grounds of discrimination (sex, race, etc), direct age discrimination can be justified. The employer must show that the treatment was a “proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.”

Thus it is theoretically possible for an employer to insist upon a mandatory retirement age for reasons associated with its occupational pension scheme. However, this is rather fanciful, as standard actuarial opinion would favour an increase in retirement age on grounds of fiscal prudence, because workers generally would be drawing pensions for a shorter number years. Thus, employers providing pension schemes with NRAs of below 65 will suffer no financial consequences if their employees express a desire to work beyond the NRA.

6. Conclusion

A nationwide default retirement age clearly is a major inroad into the age anti-discrimination principle. It need not breach the non-regression principle of the parent Directive, but the Directive affords Member States no blanket power to introduce such a major exception. Instead it must be objectively justified in the normal way. Unlike the Canadian Supreme Court, the ECJ will treat this question with the same rigour as other grounds of discrimination, such as sex. Contrary to the Government’s view, the evidence is that if the age legislation were introduced without a default retirement age it would have no adverse consequences for occupational pension schemes. Further, the default retirement age has a disproportionate effect on those without occupational pensions, who tend to be the low paid, women in part-time work, and ethnic minorities. As such, the “occupational pensions” defence is unlikely to justify the default retirement age.

Bibliography

Disney, R. and Emmerson, C. (2002) Choice Of Pension Schemes And Job Mobility In Britain, London: Institute of Fiscal Studies

Ginn, J. and Arber, S. (2001), Pension prospects of minority ethnic groups: inequalities by gender and ethnicity, British Journal of Sociology, 52, 519

Morrisson, CC. (1973) ‘Margin of appreciation in human rights law’ 6 Human Rights J 263

O’Donnell, T, (1982) ‘The margin of appreciation doctrine: standards in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights’ 4 Human Rights Q 474

[1] ‘Member States may provide that the following differences in particular do not constitute discrimination: (a) the implementation of special conditions regarding access to employment, employment or working conditions, including dismissal and pay, or vocational training for younger people, (...) older workers or those with caring responsibilities in order to facilitate their professional integration or to ensure their protection; (b) the fixing for occupational social security schemes of ages for admission or entitlement to retirement or invalidity benefits, including the fixing of different ages for employees or groups of categories of employees under occupational social security schemes on grounds of physical or mental occupational requirements, and the use, in the scope of such schemes, of age criteria in actuarial calculations, provided this does not result in discrimination on the grounds of sex; (c) the fixing of (...) appropriate conditions regarding age, professional experience or seniority in the job, to take up a post or benefit from (...) particular advantages related to a post; (d) the fixing of a maximum age for recruitment which is based on the training requirements of the post in question or the need for a reasonable period of employment before retirement; (e) the implementation of special conditions to ensure a balanced age structure in an organisation, or to ensure a smooth transition from working life to retirement; (f) the fixing of retirement ages and of employment rights linked to such ages and benefits calculated by reference to those ages.’