Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Journals

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Journals >> Migdal and Cartwright, `Electronic delivery in law: what difference does it make to results?'

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/other/journals/WebJCLI/2000/issue4/migdal4.html

Cite as: Migdal and Cartwright, `Electronic delivery in law: what difference does it make to results?'

[New search] [Help]

|

[2000] 4 Web JCLI |  |

|

Electronic delivery in law: what difference does it make to results?

Stephen Migdal

Principal Lecturer in Law, University of The West of England

<sd-migdal@uwe.ac.uk>

Martin Cartwright

Principal Lecturer in Law, University of Wolverhampton

<in5067@wlv.ac.uk>

Copyright © 2000 Stephen Migdal and Martin Cartwright.

First Published in Web Journal of Current Legal Issues in association with

Blackstone Press Ltd.

Summary

This article details research which attempts to assess what effect electronic delivery of law modules has on actual student assessment performance. The authors reviewed the assessment results of students who had taken both conventionally and electronically delivered modules and compared and contrasted individual student performances in all the modules studied by them in a particular semester. As far as the authors' researches were able to ascertain this was a relatively unique piece of research as far as legal study is concerned. We found that weaker students (those who might ordinarily fail or scrape a bare pass) were achieving a mark some 10% higher than that achieved in the conventionally delivered modules; pushing those students into the lower second category - the assessment criteria for such classification demanding evidence of deep as opposed to surface learning. However there was little or no difference in the marks achieved by upper second quality students.

The authors acknowledge that many factors affect the quality of assessment performance and that, whilst the article addresses some of the variables, any specific conclusions based on results alone are open to question. Furthermore, we accept the limitations of a small and narrow statistical sample and that therefore this can only be a survey rather than a controlled experiment. Nevertheless we believe that as part of the debate on the role of C & IT it has a useful role to play.

Inevitably an article such as this trespasses on many pedagogical issues deserving debate which goes beyond the objectives of this discussion.

Key Words

Electronic delivery; effect on results, value in promoting deeper learning, improved performance of weaker students; the importance of some degree of face to face tuition.

Contents

- Introduction

- Our Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Assessment and Assessment Criteria

- Results

- Other Published Work

-

Conclusions

- (a) Improved performance at the bottom end

- (b) Little difference at the top end

- (c) Assessment regime makes no difference

- (d) Is the key student centred delivery?

- (e) Can the continuance of face to face expository lectures be justified?

- (f) The crucial importance of face to face contact and the campus experience

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

Introduction

Over the past two years the authors have undertaken a number of empirical studies assessing the pedagogic advantages and disadvantages of delivering modules electronically via CD Rom, the internet and floppy disk (see: Migdal and Cartwright (1997) and (1998)). Our particular conclusion was that, at the very least, electronic delivery is a more than adequate substitute for the surface knowledge type lecture and should so be used to free up reflective study time for both student and tutor. But can it do more than this? Can C & IT facilitate deeper learning and understanding? We believed so although it is important to emphasise at the outset that an affirmative answer to this question would do nothing to detract us from our firmly held subscription to the view that it could never replace face to face contact completely (see our conclusions).

Our conclusions as to deep learning capabilities of C & IT learning were, however, based on somewhat qualitative subjective criteria; namely the evaluations of staff and students. (For similar qualitative research findings see: Widdison and Schulte R (1998), Widdison and Pritchard (1995).) We wondered whether quantitative evidence in support might be found by comparing individual student assessment performance across conventionally and electronically delivered modules. In short, does electronic delivery produce more effective learning i.e. better results?

Of course we were very wary of making assumptions that there was some, or any, correlation between assessment grades and the subject delivery method. However, as we now explain, we felt sufficiently able to divorce some of the major variables so as to justify proceeding with the research. Tutor motivation engendering student enthusiasm must be major contributors to student success. And tutor commitment to electronic delivery might consciously or sub-consciously lead to "generous" marking (the self-fulfilling prophecy argument). However we deliberately chose to examine results that pre-dated the decision to undertake the research. Accordingly, when delivering and marking their courses, tutors were unaffected by knowledge of the research. Furthermore, and most significantly, when delivery methods moved from conventional to electronic the external examiners responsible for approving grades remained the same. It is a safe assumption that they remained objective when confirming improved grades.

But what of the other side of the coin: student demotivation arising from the boredom of expository lectures as graphically stated by Gibbs (1995 at p.2)

"traditional teacher centred methods and syllabus centred methods have not always led to quality in learning but to passive, bored students giving back to teachers what they have been given in a worthless grade-grubbing way irrelevant to their future lives".

Would any differential in results reflect rather more the shortcomings of more conventional delivery than the advantages of electronic delivery? Research shows (Gibbs 1992 at p.4) that

"a surface approach does tend to produce marginally higher scores on tests of factual recall immediately after studying".

The issue therefore is not the results themselves but what they represent in terms of understanding and appreciation. The assessment criteria reproduced below (in appendix II )show that a grading above a third demands evidence of deeper learning. We acknowledge that an assessment grading does not necessarily equate with the reality of the student's depth of learning. Furthermore we recognise that the type of assessment may well impact upon the quality of result. (See, generally, Brown and Knight (1995).)

Although there is some published comparative research in other disciplines we found a paucity of it in law. We suspect that this deficiency is only partly due to a concern as to what results might actually prove. Primarily we believe it is due to the inability to compare "like with like". The School of Legal Studies at the University of Wolverhampton, as far as we can ascertain, was and is in a fairly unique position as regards the number and spread of electronically delivered modules being offered together. We were not compelled to compare students in different years of study, of different sexes, of different ages and with different social pressures on their studies. We were able to compare the same student's performance in conventional and electronically delivered modules thereby removing numerous other obvious variables that might affect performance.

We conducted research into the results of students at Wolverhampton University during the academic year 1997/98; comparing and contrasting assessment performance in electronically and conventionally delivered modules undertaken by the same student during the same academic year. We looked at student performance in 7 modules. The largest module had 74 registered students and the smallest had 13 (see Graph 1 - Figure 1 below). In all we looked at 295 student performances. This was a small and narrow sample (students from one institution only) and we were aware of the dangers of arriving at definitive conclusions based on such a sample. We also accept that this was, in essence, a survey rather than a controlled experiment (The authors have now embarked on a full-scale controlled experiment; the results of which will be published in 2001). We were mindful of Richardson's "health warning" (1994) against drawing any valuable conclusions on teaching and learning from empirical research. We were seeking to investigate the impact of C & IT by examining both the results of individual students undertaking the modules in our investigation and the overall module results. However, we are firmly of the view that the differences in student performance between the modules could not be explained by natural variation alone and that differences in student performance may be the consequence of the use of C & IT. At the very least our findings point towards the need for further research in this area.

Top | Contents | Bibliography

Our Hypothesis

(1) Modules using C & IT as a central part of the delivery method may result in better assessment performances than those delivered conventionally i.e. without any electronic component.

(2) Accepting, however, that the key to effective learning is the student centred nature of the delivery method rather than the method itself C & IT student centred modules produce a better assessment performance whatever the teaching and learning approach. Accordingly surface knowledge-giving expository lectures can and should be abolished. Here we are using "student centred" according to the Gibbs' definition (1995 at p.1.) namely where

"the emphasis is on:

- learner activity rather than passivity, and what the student does in order to learn rather than on what the lecturer does in order to teach;

- students' experience on the course, outside the university and prior to the course rather than on knowledge alone;

- process and competence, on how students do things, rather than just on content and what they know;

- and, most importantly, where the key decisions about learning are made by the student or by the student through negotiation with the teacher rather than solely by the teacher. These decisions include:

- what is to be learnt (the goals);

- how and when it is to be learnt (the methods and schedule);

- with what outcome (the assessment product or evidence);

- what criteria and standards are used to assess the outcome;

- what judgments are made (the marks or grades);

- by whom these judgments are made."

(3) The assessment criteria governing the study demanded that higher marks (lower second and above) cannot be achieved by those demonstrating only surface knowledge. Accordingly if the study revealed a lower second or better than average performance this is some evidence in support of the proposition that C & IT delivered modules may produce deeper learners.

Top | Contents | Bibliography

Methodology

We compared the students' average result in their electronically delivered module(s) with their average result in their non-electronically delivered modules. In an attempt to exclude some variables we also compared the average mark in the C & IT modules with the average mark in Law of Medicine (100% coursework assessed but not student centred) and with Health & Safety Law (100% coursework assessed and paper student centred).

The electronic modules considered were:

Public International Law

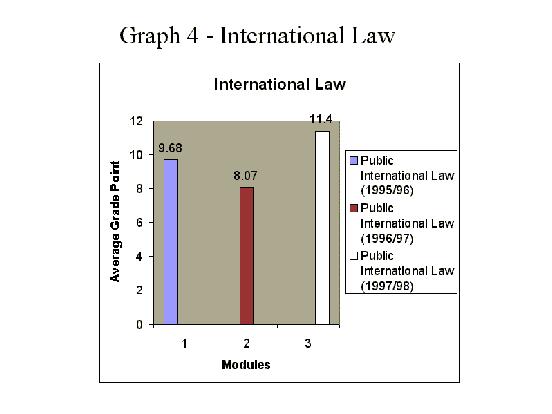

This module was conventionally taught in the academic years 1995/1996 and 1996/1997. That is by way of two, information giving, lectures per week followed by a fortnightly seminar. The module was taught over a whole academic year (30 weeks) and was assessed by way of a three hour unseen examination. The School of Legal Studies embraced modularity and semesterisation in 1997/98 and a slimmed down version of the module was then taught over a single semester (14 weeks). The assessment was then based on coursework. There was no examination. The module was delivered on a "workplan" method whereby students were given study plans in each of 5 topic areas. The plans contained study questions as well as study tasks which each student was required to complete (for a description of the workplan method see Migdal and Cartwright (1991)). Students were assessed on the basis of their performance in each workplan.

The improvement in student performance indicated by Graph 4 - figure 4 may be attributable to the change from a year long module to a semester based one or to the change in assessment strategy. But, it should be noted that the teaching team on this module remained the same and it had the same set of external examiners. We are of the view that the dramatic improvement in student performance in 1997/1998 could be accounted for by the change in delivery method from conventional to electronic. The teaching team on the module certainly took this view

Housing Law

Poverty Law

These two modules are both semester based modules. They are taught on the using the "workplan" method. Assessment in respect of both modules was by way of workplan performance and 3,000 word assignment. Poverty Law had 67 students registered on module. Housing Law had 65 students registered.

Nationality and Immigration Law

This is a 2nd/3rd year single semester module. As with the Poverty and Housing Law modules it is taught using the workplan method however 100% of the assessment is based on the students' performance on the workplans. There is no written assignment. 74 students were registered on the module.

The non-electronic modules were:

Law of Medicine

This was a single semester module taught traditionally that is, by way of two weekly lectures and fortnightly seminars. The assessment was, however, by way of 100% coursework - two 3,000 word written assignments. There were 65 students registered on the module.

Health and Safety Law

A single semester module delivered using a student centred approach. Students were given workplans and study tasks and paper based study materials. Assessment was by way of 100% coursework. There were 13 registered students.

Assessment and Assessment Criteria

The University of Wolverhampton uses an alpha numeric grading scale for all its undergraduate programmes (see Appendix I). The School of Legal Studies has established Assessment Criteria in respect of all modules in its portfolio, a copy of which can be found in Appendi xII.

Results

FIGURE 1

Figure One indicates the number of students that were involved in our study. The largest module had 74 registered students, the smallest had 13. Altogether the study examined 295 student module performances.

Commentary

Housing Law, Poverty Law, Nationality and Immigration Law and Public International Law were all delivered electronically. Two comparator modules were examined. Law of Medicine was delivered conventionally - two information giving lectures per week and a fortnightly seminar. Health & Safety used a paper based student centred delivery method.

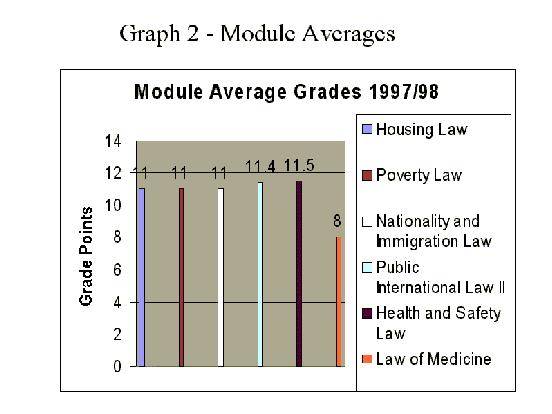

FIGURE 2

Figure Two shows the average module grade achieved by students on the modules in the study.

Commentary

It will be noted that there is little difference between the average grade in the electronic modules and that achieved in the paper-based student centred Health & Safety. All achieving an average of 11+ i.e. lower 60's in percentage terms. However the conventionally delivered Law of Medicine achieves a much lower average of 8 i.e. 50% in percentage terms and this despite the fact that this module was assessed by way of 100% coursework, providing some evidence that it is not the assessment method that determines performance.

FIGURE 3

Figure 3 shows the average grades in Housing and Welfare Law, Poverty Law and Housing Law during the period 1995 to 1999.

Commentary

Housing and Welfare Law split into two modules (Housing and Poverty) in 1997. Prior to that it had been a paper based student centred module. It will be noted that there has been a considerable improvement in the performance of students on Poverty Law and Housing Law (1997 to 1998) in comparison with the results in Housing and Welfare Law (1995 to 1997), some evidence, perhaps, that electronic student centred delivery achieves better results than its paper-based equivalent. The Housing Law result for 1998/99 appears disappointing in comparison. However, this result must be seen in the context of an overall poor result in the semester to which this module contributed. In fact, when compared with the other modules delivered during this semester, the Housing Law average is up to two grade points (6%) better than the average for other modules.

FIGURE 4

Figure 4 shows the average grades in Public International Law.

Commentary

This graph illustrates a dramatic improvement in the overall scores of students accessing this module in 1997/98 compared with the overall grades in previous years when it was conventionally taught (i.e. information giving lectures and seminars)

FIGURE 5

FIGURE 6

Figures 5 & 6 attempt to illustrate the impact of student performance of undertaking modules which are delivered using Communications and Information Technology by showing the average grades of 65 students.

Commentary

The graph also seeks to show the impact in respect of different student ability ranges. The overall average in the C&IT modules is greater by some 3 whole grade points (in percentage terms this equates to about 10%) than the overall average.

The most interesting finding is the different impact of accessing C&IT modules on students of different ability ranges. It seems that the good student (i.e. in the upper second category and above) is only marginally affected by undertaking C&IT modules. The average in these modules being 12.2 against the average in their non C&IT modules of 11.41 i.e. approximately 2%.. However, the further one goes down the ability range the more dramatic the difference. Thus students whose final overall grading is a fail grade of 4.2 achieved an average in C&IT modules of 8.5 compared to 3.9 in non C&IT modules - a difference of 4.6 or approximately 14%.

Top | Contents | Bibliography

Other Published Work

As already stated we have struggled to find other studies in which a comparison has been made between the results of individual students undertaking both electronically delivered and non-electronically delivered modules at the same time. Indeed studies comparing assessment performance generally are rare but those that have occurred have compared performance as between electronically delivered courses rather than on an individual student basis.

Huddersfield University's Web Based CPE

Fairhurst (1999) reports both better individual subject and overall performance from students studying the CPE by way of on-line delivery (ODL).

Average per Subject (ODL and Conventional)

Pass-rate per Subject (ODL and Conventional)

The students studied four modules over one year and there were twelve days of face to face tuition; otherwise contact was by e-mail. Thirteen students were on the ODL course (although only 8 completed the assessments at the end of the year) and fourteen students were on the conventionally delivered course.

Fairhurst makes the following observations on the better assessment performance by the ODL students:

" Firstly, the requirement that ODL students regularly submitted tutorial work should have ensured that they covered the whole syllabus and that any mistakes or misconceptions were rectified in the tutor's feedback (this was not a requirement for students on the conventional part-time course). However there is a caveat to this in that, in practice, six of the eight ODL students who completed the year soon began to fall behind with tutorial submission and some of the later tutorials were not submitted.Secondly, the academic qualifications of the ODL students were generally higher than those of the conventional part-time students, and therefore the ODL students might be considered to be academically stronger; this underlying factor could have had a significant effect on the data.

Nevertheless, a 100% pass rate in the first year of operation is indicative of the fact that the ODL course was educationally successful."

The Sydney College of Law Electronic Professional Program

In 1998 the Sydney College of Law delivered modules to 36 students on its Legal Practice Programme electronically by distance learning (a pilot run contemporaneously with its conventional face to face course) and compared results.

The profile of results of students undertaking the electronic course revealed:

- a higher percentage of failures (8% compared to 2%)

- a higher percentage of credits and passes (67% compared to 48%) but

- a lower percentage of distinctions and high distinctions (25% compared to 52%).

Whilst these first time results are completely contradictory to our findings (students in all ability ranges fared less well when studying purely electronically), Mulcahy was recently able to report that:

"Now that the EPP has been delivered several times, assessment results from EPP students ... [show that] in some modules there do seem to be higher failure rates among EPP students. However, in other modules the results of EPP students appear to be better."

Three of the fifteen weeks (20%) of the EPP program were delivered on-campus. All other tutor contact was limited to e-mail and telephone.

Despite the first year results, both the students and the Directorate of the Sydney College of Law so preferred the electronic course that it is now part of its established programme. Students enjoyed the freedom that electronic delivery gave them and appeared to be prepared to risk sacrificing better grades for this freedom. The Directorate, whilst recognising the value of being involved in an innovative educational programme, also saw significant resource saving benefits. Furthermore (an intrinsic benefit that is often overlooked) the students involved in the pilot had enhanced IT skills which were highly valued by their Principals once they entered practice.

A Non-Law Experience

Other disciplines are making similar findings as regards the enhanced performance of weaker students. Coleman (1999) writing in THES of his experiences of using electronic delivery on the lst year computer engineering course at Newcastle University observed:

"While it is too early to draw any strong conclusions an analysis of student performance suggests that the courseware may be better than the original lecturing in bringing weaker students up to the standard of the others."

Top | Contents | Bibliography

Conclusions

(a) Improved performance at the bottom end

The most significant and surprising result was that it was the weaker student whose performance increased most. We say "surprising" because the commonly expressed view is that the good student does well from student-centred electronic delivery but the weak student struggles. In our survey the weak student increased his mark by more than a whole degree classification. Why such improved performance? The traditional view is that weaker students depend upon the placebo of the conventional lecture to learn and repeat the law, at best, sufficiently adequately to merit a bare pass. They do not use the library; they either do not read textbooks or get little, if anything, from them. They acquire and repeat surface knowledge only.

Electronic delivery is pushing their performance into the waters of deeper knowledge. It may be objected that it is not so much improved performance in the electronic module(s) but decreased performance elsewhere. That because electronic delivery makes students more responsible for their own learning the weak student is forced to spend a disproportionate amount of study time on the electronic module at the expense of the conventionally delivered modules. What cannot be denied, however, is that the quality of performance increases.

Of course, for some time now there have been such significant financial and domestic demands on students, that it is doubtful whether there is such a thing as a "full-time" student. It may well be, therefore, that the improved performance of the apparently weaker student is attributable to the accessibility of teaching and learning materials - attendance at face-to-face lectures and visits to the library that would otherwise clash with work/domestic demands are available electronically on demand. This is a matter that we are addressing in our current research.

(b) Little difference at the top end

Good students do well whatever the delivery method.

(c) Assessment regime makes no difference

We have tried to deal with the argument that modules assessed purely by seen assignments produce higher grade profiles by reference to the medical law results. This was taught conventionally but was assessed by way of 100% coursework. The results, if anything, were worse than in more traditionally assessed modules.

(d) Is the key student centred delivery?

We accept that student-centred delivery methods, whether electronically or paper based, (see the good results in Health & Safety Law for example) do result in improved performance. However the Housing Law graph shows an increased performance of one grade point and a classification (C10 to B11) when moving from paper based to electronically delivered student centred delivery.

(e) Can the continuance of face to face expository lectures be justified?

Whilst by this research we have attempted to exclude some of the variables referred to at the beginning of this article, we accept that others remain. Nevertheless we believe the research has value. What it does show is that student performance is not worse; in other words traditional information giving lectures can be dispensed with without any adverse effect on student performance (save, perhaps, for the strategic learner).

Of course such a conclusion states nothing new. There is a large amount of longstanding literature about the inadequacies of the learning experience of those suffering "traditional" lectures (see, for example, Biggs. (1985) Cohen Stanhope and Conway (1992) Marton and Wenestam (1978)).

Sadly law lecturers in particular have been slow to abandon expository lectures. It may well be that the imperative to do so will come not from the availability of C & IT but rather the practicalities of academic life in this climate of increased student numbers but reduced resources which can only be exacerbated by government commitment to increased access, lifelong learning and so forth.

(f) The crucial importance of face to face contact and the campus experience

A common early error of those jumping upon the C & IT bandwagon (including your authors) was that electronic delivery might well be a complete substitute for other forms of learning. This cannot be the case. Snowballing, pyramiding, buzz groups and so forth are most successful in a face to face context (see, for example: Alldridge and Mumford (1998) and Jones and Scully (1998)). Furthermore the value of the social interaction arising from what we term "the campus experience" has to be emphasised.

We do not include video and audio conferencing in our definition of face to face contact. Burge and Howard (1990) found that such inhibited interaction (see also: Boyd (1999)).

The Wolverhampton courses averaged 17% of face to face contact and those of the Sydney College of Law's 20%. The Huddersfield project does not specify its twelve days as a percentage but Fairhurst concluded that the face to face tuition:

" proved to be a vital element in the learning experience of students, providing the opportunity for tutors to motivate the students and for the students to engage in face to face interaction with their fellow students and tutors."

This clear link between social interaction and deep learning has been recognised for some time. See, for example, Entwhistle and Ramsden (1983) and Garrison (1992). Indeed our own research revealed that one of the commonest student complaints about pure electronic delivery is the feeling of isolation (see: Migdal and Cartwright (1998)).

The importance of the campus experience is clearly shared by the American Bar Association which refuses to recognise any distance learning programme unless it contains a minimum of 20% of on-campus delivery (see: the memorandum to the Deans of ABA Approved Law Schools). This is important and perhaps comforting in the face of the threat to traditional providers of legal education from the virtual global providers. Whilst our professional bodies must eventually recognise, as qualifying law degrees, some electronically delivered programmes we are convinced that, as in the USA, a significant on-campus component will be required.

Appendix I

DEFINITIONS

i. "The Alpha Numeric Grading System "

| A14 - A16 | = | first |

| B11 - B13 | = | upper second |

| C 8 - C10 | = | lower second |

| D 5 - D 7 | = | third |

| E 3 - E 4 | = | fail |

| F 1 - F 2 | = | fail |

Each grade point broadly approximates to 3%

ii. "Weaker students " = third class and below

"Average students" = lower second

"Better students " = upper second and above

iii. "Electronic delivery"

1 x 1 hour whole group overview presentation plus 1 x 30 minute small group (5/6) workshop in every nine hours of study

Accordingly face to face contact was less than 17% of designated (i.e timetabled) study time.

All other delivery is via HTML floppy disks containing study programmes with hypertext links to study materials.

Appendix II

The Assessment Criteria

Upper Second Class (B13, B12 & B11)

Upper Second Class work demonstrates work of a very good standard. Again it will reflect the achievement of all of the outcomes specified in respect of coursework for this module. In essence, a B grade is awarded for doing the same sorts of things as for a First, but not doing them quite as well; or for doing many of the things which warrant an A grade but not doing them all. Written communication skills, analysis of cases and issues and the use of a wide range of sources are all very important in obtaining an Upper Second Class mark.

Presentation will be to a high standard, with very few grammatical, punctuation, typographical or spelling errors. There will be proper footnoting and citations. The structure of the argument must be completely clear and logical. Identification and examination of the key issues is essential.

Lower Second Class (C10, C9 & C8)

Lower Second Class work is work of a good average standard. All of the attributes required to achieve the module's specified outcomes for coursework will be evident. In addition, presentation will be good or very good, but there will be occasional lapses in grammar, punctuation and spelling. Footnoting and proper citations are required, as is a bibliography of all sources used in the argument. Written style will tend to be more narrative than analytical, though cases/judgements and materials relied upon still will be subjected to some comment. The structure of the argument will be clear. The main issues will be clearly identified, but may not be as thoroughly explained and analysed as they need to be. Some subsidiary issues may be missed. The range of sources drawn on and incorporated into the argument will not be as wide as for an Upper Second Class grade.

Third Class (D7, D6 & D5)

Third Class work is work of a satisfactory standard, including work which is a bare pass only. Evidence of the achievement of the module's specified outcomes for coursework will be found. Presentation will be acceptable but there may be a number of grammatical and other errors. Not all key issues will have been identified and explained, though a majority of the issues will be. There will be a bibliography, but footnoting may be minimal and citations may not be given in full. The range of sources used is generally not very wide. There is some analysis of relevant authority, but the style tends to the narrative. Legal principles will be correctly stated.

Bibliography

Alldridge P and Mumford A "Gazing into the future through a VDU: Communications, Information Technology and Law Teaching" (1998) Journal of Law & Society 25 (1) 116

Biggs J.B. (1985) "The role of metalearning in study process British Journal of Educational Psychology" Vol 55 pp185-212

Boyd W "But what is it good for? Using interactive video in legal education and practice" (1999) (3) JILT: <http://www.law.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/99-3/boyd.html>).

Brown S and Knight P "Assessing Learners in Higher Education": Chapter 3: Kogan Page (1995))

Burge P and Howard R "Audio-conferencing in graduate education - a case study American Journal of Distance Education (1990) Vol 4 issue 2 pp3-13.

Cohen G, Stanhope N and Conway M "How long does education last? (1992) The Psychologist Vol 5 No 2

Coleman N: "A Microchip off the old block" Times Higher Education Supplement 12th. March 1999

Entwhistle N and Ramsden P (1983) Understanding Student Learning, London. Croom Helm

Fairhurst J "Evaluation of an Internet-based PgDL (CPE) Course" (1999) JILT Vol 3 <http://www.law.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/99-3/fairhurst.html>

Garrison D.R. (1992) Critical Thinking and Self Directed Learning in Adult Education: an analysis of responsibility and control issues Adult Education Quarterly Vol 42 Issue 3 pp136-148.

Gibbs G "Assessing Student Centred Courses" Oxford Centre for Staff Development (1995)

Gibbs G "Improving the Quality of Student Learning" Technical and Educational Services Limited (1992)

Jones R and Scully J "Hypertext within Legal Education" (1998) Vol. 2 Journal

of Information law and Technology

<http://elj.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/cal/2

jones/>

Marton, F and Wenestam CG " Qualitative differences in the understanding and retention of the main points in some texts based on the principle-example structure" in Gruneberg, Morris and Styles: Practical Aspects of Memory, Academic Press (1978)

Memorandum to the Deans of ABA Approved Law Schools at <http://www.abanet.org/legaled.distance.html>.

Migdal S and Cartwright M "Pure Electronic Delivery of Law Modules - Dream

or Reality?" (1997)

<http://elj.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/cal/97_2migd/#article99.htm>

Migdal S and Cartwright M "Information Technology in the Legal Curriculum - Reactions and Realities" The Law Teacher (1998) Vol 32 Number 3).

Migdal S and Cartwright M "Student Based Learning - A Polytechnic's Experience" The Law Teacher (1991) Vol 25 No 2 120

Mulcahy K "The College of Law's Electronic Professional Program": The Second Annual Learning in Law Initiative Conference, Warwick January 2000

Richardson J : "Using Questionnaires to Evaluate Student Learning: Some Health Warnings" from "Improving Student Learning": Oxford Centre for Staff Development. Ed: Graham Gibbs (1994).

Widdison R and Schulte R, 'Quarts into Pint Pots? Electronic Law Tutorials Revisited', (1998) (1) The Journal of Information, Law and Technology <http://elj.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/cal/98_1widd/>

Widdison R and Pritchard F (1995) 'An Experiment with Electronic Law Tutorials' 4(1) Law Technology Journal 6)