1. Introduction

“Piracy is a business model. It exists to serve a need in

the market – consumers who want TV content on demand. And

piracy competes for consumers the same way we do: through quality,

price, and availability.”1

Consumer

options for consuming creative content in digital form, such as

music, movies, books, and television shows, have increased

significantly with the development of the Internet. Entrants into

the distribution stage of production have developed new business

models to deliver digital content in general and copyrighted digital

content in particular. The objective of this paper is to analyse the

development of competition in the delivery of digital content to

consumers. In particular, the focus is on new technologies that

facilitate online dissemination of digital content to consumers

through the use of peer-to-peer (P2P) networks and video hosting

sites that have proliferated over the Internet since the late 1990s.

The role of copyright as a potential competitive weapon by incumbent

disseminators is joined in the analysis. P2P file sharing networks

and video sharing web sites are viewed as entrants into the market

for the dissemination of digital content to consumers. The incumbent

technologies for distributing content have reacted aggressively to

this new source of competition and have pursued legal, economic, and

moral strategies to combat the use of authorised and unauthorised

content by the distribution entrants. Perhaps the most important

point to keep in mind is that online distribution, both authorised

and unauthorised, is here to stay.

Section

II presents background information depicting a stylised view of the

value chain/production process and models the consumer’s

choice problem by identifying characteristics of online distribution

platforms that factor into the consumer’s decision making

process when the consumer accesses digital content. Section III

describes the varying technological designs that entrants utilised

to distribute digital content to consumers. Section IV analyses

legal strategies that copyright owners have pursued to address the

threat of competition and poses four questions that software

developers of new online distribution platforms need answered

clearly and with predictability to spur technological advancement.

The answers to the questions posed require an extended discussion of

the legal and economic issues surrounding the entrants’

technology and business models. Section V offers a conclusion.

2. Background and Consumer Choice

Problem

Diagram

1 is an overview of the stages in the production and delivery of

content. The production process/value chain in general includes the

creation of content, negotiations between the content creator and

the publisher of the content, the distribution of content for access

to consumers, and the consumption of content by consumers.

DIAGRAM

1. Stages of Production/Value Chain

Content

creators include artists who write and record songs, write

television shows, author books, and write movies. Historically,

content creators aspired to earn a living from the work, although

there is an increasing body of content that is now make freely

available to the public. Content is then published by music

companies, book publishers, movie studios or television production

companies that put the content in form consumers will find

interesting. Frequently, the ownership of the copyright ends up in

the possession of a firm who is also integrated into the

distribution stage of production. The distribution stage provides

the delivery service of content to consumers. It should be noted

that access to copyrighted and non-copyrighted content is an

essential input into the distribution stage of production.

Firms in

the distribution stage differentiate their service over a set of

characteristics/attributes that they hope is important to consumers

when they decide how to gain access to their preferred content.

Bakker identifies eight different aspects upon which paid download

services (such as Apple’s iTunes music store) and peer-to-peer

file sharing services (such as LimeWire and Kazaa) compete to

attract consumers.2

Sag develops a benefit-cost model comparing the net benefits from

unauthorised downloading to the net benefits from legally acquired

music.3

In particular, Sag categorises benefits in terms of functional

value, normative value, and law-abidingness value and costs in terms

of monetary cost, search costs, expected costs from computer

viruses, and expected cost of sanctions.

In

general, alternative online delivery services for content, such as

licensed services, unlicensed file sharing services, and video

sharing services, offer consumers different bundles of

characteristics from which to choose. Building on the Bakker and Sag

models, the following set of characteristics are likely to be

considered by a consumer when choosing between alternative

distribution services:

Price

Selection of content

Quality

Speed of access

Security

Legal liability

Ease of use/portability

Search cost

Unbundled access to content

Sense of community

Extra features

It should

be noted that each characteristic may not be relevant to a consumer

for all forms (e.g., music versus television show) of content.

Bakker

was interested in identifying the aspects/characteristics that were

of most importance when a consumer chooses between paid legal

download services and file- sharing services. His research revealed

that the online distribution market is composed of two distinct

types of consumers, file sharers and paid downloaders. File sharing

services are attractive to a younger, more computer savvy audience

that displays both patience and persistence, whereas the paid

download service attracts a more mature consumer. Thus, online

distributors need to understand this market segmentation indicating

two different types of consumers and develop appropriate business

strategies to target each segment. The focus of Sag’s model

was to analyse the impact on consumer behavior from a litigation

strategy that targeted marginal file sharers.

Felten

sketched a theoretical model of consumer behavior in which he

further disaggregated the market segment consisting of file

sharers.4

Specifically, he decomposed file sharers into two types, free riders

(young people with few moral qualms about file sharing) and samplers

(older, more risk-averse, people who were morally conflicted about

file sharing). This decomposition enabled Felten to explain

disparate findings in empirical studies examining the impact of file

sharing on music sales.

None of

these models factors into the consumer decision making process the

entry of video sharing web sites, such as YouTube and MySpace, which

concentrate their efforts on building a sense of community among

users of the service. These sites provide access to copyrighted

(often unauthorised) content and, more importantly, user-generated

content. The characteristics/attributes identified above provide a

conceptual framework for analysing the competition between the

content providers’ sanctioned online providers of content and

the new entrants in the form of peer-to-peer file sharing networks

and video sharing web sites.

3. Architecture of Entrants’

Networks into Online Distribution

A

distinguishing characteristic of a P2P file sharing network is that

content is not stored at a server within the network but rather on

peer computers at the edges of the network. A user wishing to

utilise a P2P file sharing network needs a software application

program downloaded from a P2P software provider’s web site

that will enable the user to locate others users on the network, an

ability to locate content available from the network edges, and a

communications protocol to exchange files.

The

emergence of Napster in May 1999 introduced the world to a hybrid

version of a peer-to-peer file sharing network for distributing

digital content, in Napster’s case music MP3 files. Napster’s

network facilitated the sharing of (mostly unauthorised) music files

in unprecedented magnitudes. Napster’s architecture contained

a central server that indexed the files that were available on peer

computers from the network. The most noteworthy P2P innovation of

the network was decentralisation in storage of shared files.5

Individual computers at the edges of the network hosted the sought

after content. So when a user downloaded a file, the copy of that

file was uploaded from a peer in the network, not a central server.

Thus, Napster facilitated the exchange of music files by providing a

central index of the content and arranging for the connection

between the downloading and the uploading peer computers. This

architecture, containing a centralised index, meant legally that

Napster exercised “control” over the network and when

copyright holders notified Napster that copyrighted content they

owned was available on the network without their permission, they

than possessed “actual knowledge” of infringing

activity. Control and actual knowledge led the court to conclude

that Napster was liable for indirect copyright infringement because

its service facilitated direct infringement by its users. The

“original” Napster eventually shut down operations in

2001 after attempting to install filtering mechanisms.

Software

developers of peer-to-peer file sharing technology learned key

design lessons from the Napster decision. Developers began to

disaggregate the functions necessary (such as search for files and

sources of downloaded files) for a P2P network. P2P file sharing

networks were introduced that did not contain a central index of

available content and developers relinquished control over the

behavior of the peers in the network once a peer downloaded the

client software, hoping to have the courts view the software as a

product (like a VCR) and not a service capable of an ongoing

relationship. Companies such as Kazaa, Grokster, and LimeWire

emerged as successors to Napster in terms of facilitating the P2P

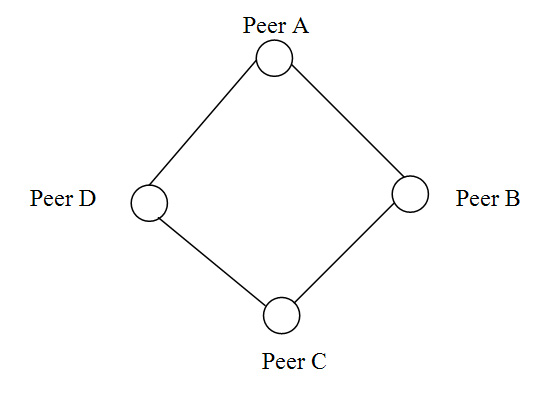

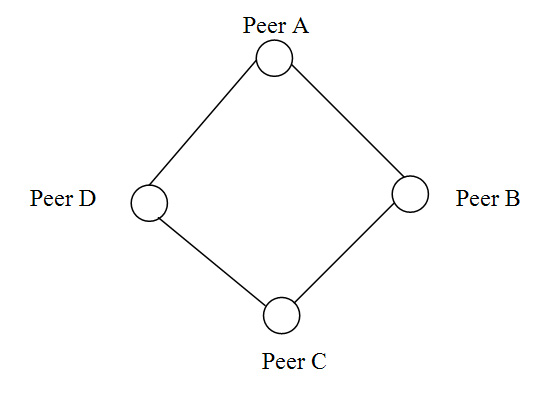

sharing of content, mostly presumptively copyrighted. Diagram 2

shows alternate network designs.

DIAGRAM 2. 6

Pure Peer Network (early Gnutella)

Hierarchical Peer Network (Kazaa, Grokster, Lime Wire)

Centrally Coordinated Peer Network (Napster)

Client Server Network (YouTube, MyMP3.com)

An

example of a pure P2P file sharing network was the original design

of Gnutella (released March 2000) in which the search function and

content storage were totally decentralised, meaning that each

function was conducted at the individual peer level. This design

suffered from several technical weaknesses that have diminished its

role as a competitive distribution platform.

The

client server network, utilised by emerging video sharing web sites

such as YouTube and Grouper and licensed distributors such as

iTunes, is at the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of control

for peer interaction only occurs with a central server and the

server hosts the content and provides search functionality. Thus,

there are no P2P aspects to this design.7

The centralised control of all functions is an operational strength

of the design. Somewhere between the two polar designs is the

original Napster’s centrally coordinated peer design with

centralised search functionality but peer storage of content. Also,

in the middle of the spectrum is Kazaa and Grokster’s file

sharing networks that feature a hierarchical peer design. The search

functionary is carried out, not centrally, but rather at peer

supernode computers and files are hosted and exchanged through

supernodes among peers. There are benefits and costs to each design

but the focus of the paper is how legal decisions influence the

design of network architectures that are emerging as competitors in

the online distribution market. Wu characterises the behavior of

developers who design application software with this overriding

architectural objective as “…designing code to avoid

copyright infringement.”8

In 2001,

copyright owners sued the P2P file sharing companies Grokster and

StreamCast Networks (makers of the Morpheus software) that utilise a

hierarchical peer design and won a significant legal decision in the

June 2005 Supreme Court’s Grokster decision. The

Supreme Court did not evaluate in its main opinion the merits of the

hierarchical peer design but instead imported from patent law the

theory of active inducement, applied it to the facts of the case,

and found reason to remand the case back to district court. The

decision means that for future copyright cases of this nature, first

the court will examine the intent behind the development of a new

technology before it proceeds to determine whether a dual use

technology that facilitates both infringing and non-infringing uses

is legal. The Grokster decision hinged on the “bad”

behavior of the companies rather than on the architectural design of

the software they distributed.

In

September 2006, a set of copyright owners sued in the southern

district court of New York the P2P file sharing company LimeWire

that offers client software that utilises the revised Gnutella

network hierarchical design with a decentralised search index. Thus,

the court may get another chance to analyse LimeWire’s file

sharing technology design using the Sony decision of 1984 and

its “capable of substantial non-infringing use” rule.

In

response to the Napster and Grokster legal decisions,

P2P file sharing software developers have continued to adapt P2P

code. Choi examines how P2P file sharing developers continue to

decentralise the functions of P2P networks.9

Specifically, Choi characterises the tactics of file sharing

software developers to disaggregate the search and delivery

functionalities to insulate the networks from legal challenge as a

“guerrilla movement” against copyright owners. For

example, BitTorrent file sharing software provides an efficient way

(swarming) to share (especially large such as video) files among

peer computers and discourages free-riders through a tit-for-tat

element of the protocol but at a time and patience cost for users.10

A downloader must first find a web site that lists “torrent”

files. A “torrent” file contains metadata that contains

information about the location of a computer that hosts the

particular file and the location of a “tracker” server

that is concurrently coordinating exchanges of the file. The

downloader then clicks on the requested file to enter the exchange

process. Search engines such as Isohunt, Torrentspy, Torrentbox, and

Pirate Bay provide directions to files that are shared across the

network.

The

disaggregation of the search and file transfer functions make the

process of file sharing for users more complex and costly in terms

of time but to date less susceptible to legal challenge. Although

copyright owners have shut down some of these tracking/index sites,

Choi argues persuasively that, “While trackers can be shut

down and removed from the Internet, this process is about as tedious

as shutting down individual direct infringers.”11

That is, the comparative cost advantage of pursuing intermediaries

as indirect infringers compared to direct infringers diminishes as

the networks become increasingly decentralised.12

Thus, the cost effectiveness of continuing lawsuits alleging

indirect liability is in doubt. On the other hand, the more involved

search process increases the relative cost of utilising an

unauthorised P2P file sharing program to an end user. This may

persuade consumers to turn to legal download services for content.

Video

sharing web sites such as YouTube use a centralised server client

network and have emerged as significant competitors in the

distribution stage of production of content, copyrighted and

user-created. Users upload content for aggregation on the web site

and the site provides a search function for users. YouTube is

different from existing distribution channels for it is designed to

accommodate a more participatory role by end users in modifying and

enhancing existing content as well as creating new content. End

users are not expected to be mere passive consumers of static

content. Sites such as YouTube hope to utilise Section 512,

contained in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, for

insulation from legal liability.13

Section 512 seemingly provides a safe harbor for web sites that

store materials on behalf of users as long as they follow a set of

legal and technical requirements for removing infringing material

when notified by the copyright owner. Nevertheless, in many cases,

these sites end up hosting infringing material. YouTube has actively

sought licensing deals with copyright owners to reduce the

likelihood of lawsuits even though it presumptively qualifies for

the safe harbor.

Diagram

3 identifies representative competitors for three alternatives

network designs that provide online distribution of content:

Diagram

3. Representative Competitors

|

Licensed/Authorized Online Distributors

|

Unlicensed/Unauthorized P2P File Sharing Distributors

|

Video Sharing Websites

|

|

iTunes

eMusic

Yahoo Music

Rhapsody

Zune

MovieLink

CinemaNow

Vongo

Guba

(new) Napster

iMesh

Peer Impact

Shared Media

Mashboxx

|

Bit Torrent

LimeWire (currently sued and countersued)

Grokster (shut down)

eDonkey (shut down)

WinMX (shut down)

i2hub (shut down)

Napster (shut down)

Aimster (shut down)

|

YouTube

MySpace

MSN

AOL

Yahoo

blip.tv

Veoh

Joost

Grouper

Bolt

TVV

Revver

|

Sources: (i) Center for Democracy and Technology,

Post-Grokster Secondary Liability Developments,

January 2007.

(ii) Andrew Currah, “Hollywood versus the Internet: the media

and entertainment industries in a digital and networked economy”

(2006) 6 Journal of Economic Geography, 449.

(iii) Various issues of the Wall Street Journal.

The arrow

next to BitTorrent indicates that the company who developed the

open-source communications protocol that is widely used by P2P

clients to share files is now soliciting licensed copyright deals to

transform itself into an authorised online distribution medium.

The

diagram indicates an increasingly competitive environment in the

distribution of online content. Generally, as competition increases,

consumers benefit from lower prices, increased output, and a more

rapid pace of technological change. To stem the tide of entry into

distribution, the extant content distributors are pursuing an

aggressive legal strategy with multiple tactics. On one hand, in the

view of copyright owners, the goal of such a legal strategy is to

prevent unlicensed competitors from utilising intellectual property

without permission or authorisation. On the other hand, such a

strategy tends to increase the uncertainty on the part of technology

developers as to the legality of innovative methods of online

distribution and, thus, may tend to reduce innovation in the

market.14

In order to examine potential sources of uncertainty, an analysis

of the legal and economic environments facing technological

innovators is necessary.

4. Legal and Economic Environment

4.1 Indirect Liability Strategies

Online

entrants offer services that are utilised by customers who engage in

both non-infringing and infringing activities. Direct copyright

infringement may occur when a customer reproduces, distributes,

publicly displays, creates derivative work, or publicly performs

copyrighted content without the authorisation or permission of the

copyright owner. Indirect copyright infringement may occur when the

developer of a product/service/device utilised by a customer

facilitates the unauthorised direct infringement of copyrighted

content. To build a successful business, researchers and developers

of new dual use technologies rely on established legal rules for

assurance that their product is immune from indirect liability. That

is, in order to provide a legal environment conducive to innovation,

it must be clear under what circumstances a developer is responsible

for the direct infringement acts of its customers. The following

four questions provide a framework to understand the settled ground

rules for competition as well as the unresolved issues for which

uncertainty still exists.

QUESTION

1: Is the product/service capable of substantial non-infringing

uses?

Suppose a

developer creates a product, such as a photocopier, MP3 player,

computer, or digital video recorder that can be used by its

customers for both non-infringing and infringing uses. One key legal

issue is whether or not the developer is indirectly liable for the

acts of direct infringement by its customers. Indirect liability, in

general, asks whether the developer created a product to

intentionally encourage or induce direct infringement and profited

from that direct infringement. The Supreme Court addressed this

issue in 1984. The Sony rule, created as a result of a

lawsuit between Sony and Universal City Studios involving the analog

videocassette recorder (the Sony Betamax), concluded that “the

sale of copying equipment, like the sale of other articles of

commerce, does not constitute contributory infringement if the

product is widely used for legitimate, unobjectionable purposes.

Indeed, it need merely be capable of substantial non-infringing

uses.”15

Thus, a developer of a technology that a customer may use to

infringe directly on copyright must be confident that the product is

also capable of substantial non-infringing uses. If this is

demonstrated, the product is free from liability even though the

developer knows or has reason to know that the product can be used

for infringing purposes. If it is not capable of substantial

non-infringing uses such as in the case of cable descramblers, it is

likely that the developer of the product will be subject to

liability for indirect infringement and thus in the long run its

business model is not likely to be economically viable. The

extension of this rule from an analog device such as a videocassette

recorder or a copying machine to digital services offered by Napster

or peer-to-peer software providers such as Grokster, Lime Wire, or

BitTorrent, and perhaps to video sharing sites such as YouTube, has

proven both interesting and controversial.

There

still exists uncertainty with how words in the Sony rule

should be or will be interpreted. Is there a need to quantify the

meaning of “substantial” and should or will a future

court set a benchmark for the ratio of non-infringing uses to

infringing uses? It appears based on the opinions in the Sony

and Grokster16

cases that a product must have at a minimum ten per cent of its uses

non-infringing to be safe from indirect liability. The plain meaning

of the word “capable” suggests that one should count

current uses and potential future uses, although one circuit court

argued that one should only include probable uses.17

Which party in litigation bears the burden to demonstrate whether

the product is or is not capable of substantial non-infringing uses?

Finally, and an issue to be explored in more detail below, should

the developer of the technology be responsible to have considered

alternative cost effective designs of the product that would have ex

ante reduced or eliminated infringing uses?

QUESTION

2: Does the design of the service enable the developer to have

actual knowledge of infringement and control to eliminate or reduce

economically the infringing uses of the product/service?

Peer-to-peer

software developers learned several key lessons from the litigation

over Napster’s design. Napster’s architecture

decentralised the storage of files but maintained a site and

facilities that included a central server that indexed music files

that were available to be shared by its customers. This design

subjected Napster to charges of facilitating direct infringement by

its customers. Copyright owners successfully sued Napster for

indirect infringement and the decision rested on the ability of

Napster to eliminate the infringing uses of its service when it

received actual knowledge of direct infringement activity by its

customers. The court concluded that Napster could and should

redesign its service to block the exchange of any infringing music

files while continuing to allow permissible uses.18

The centrally coordinated peer network employed by Napster gave it

control over the acts of direct infringement by its customers and

copyright owners gave Napster notice of the infringing acts of its

customers at a time when Napster could do something about it. Thus,

peer-to-peer developers learned to create software that could not

easily be redesigned to give control over customers or actual

knowledge of infringing activity. In short, the lesson learned was

to design code to relinquish control over peer-to-peer software and

thus, how consumers used the software.

This led

to the introduction of the hierarchical peer design. Based on the

rules learned in response to the first two questions, developers

were led to believe that, if they developed a service that was

capable of substantial non-infringing uses, utilised a design that

decentralised the search function, stored files at peer computers,

and had no ability to reduce or eliminate direct infringing acts,

then the service would be immune from indirect liability. Moreover,

if the developer’s company ceased business, customers could

still use the software to share files. But, in a surprising decision

to the legal and technology communities in 2005, the Supreme Court

created a new theory of indirect copyright liability.

QUESTION

3: Did the developer of the service engage in behavior to actively

induce copyright infringement?

The

significance of the Grokster decision is that the behavior of

the developer may be subject to indirect liability under an active

inducement theory. Specifically, a developer’s actions and

motives are scrutinised for signs of “clear expression or

other affirmative steps taken to foster infringement.” If the

developer’s firm is found liable for inducement infringement,

than a service’s design and capability for substantial

non-infringing uses are irrelevant. This means that a developer

cannot design its dual use service to eliminate control and actual

knowledge as Grokster did and at the same time take active steps to

solicit customers based on the potential for the service to infringe

copyright. The court identified three possible elements of intent to

infringe:

advertise the ability of the service to infringe on copyright,

fail to proactively filter out infringing uses,

rely on a business plan that is directly linked to the volume of

infringing activity.

According

to the Court, element ii or iii alone is not sufficient to establish

intent to infringe.

There are

several outstanding issues concerning interpretation of the rule on

active inducement. First, in the case of Grokster, the Court found

evidence of all three elements of inducement and concluded that

there was “bad behavior” by the defendants. It is not

clear whether all three elements must be present or perhaps only two

of them or element i alone for “bad behavior” and thus

intent to infringe liability. It is unknown the range of behaviors

(e.g., anti-spoofing features, use of encryption, private viewing

groups) that could be considered evidence of inducement.19

Hopefully, according to one prominent legal scholar, courts will

apply high standards to demonstrate inducement liability.20

Second, elements ii and iii are not necessarily independent. If a

developer planned on building a business model based predominantly

on facilitating infringement, the developer would not likely filter

the service. Thus, the conclusion that each element ii and iii alone

is insufficient for inferring intent to infringe is based on an

incomplete analysis. Third, there is no quantification standard of

what it means to rely on infringement as a major revenue source in a

business model. Most services will experience an increase in revenue

from increased use of the service regardless of whether it is from

non-infringing use or infringing use. Fourth, the Grokster

rule emphasises affirmative steps suggesting that proactive

filtering efforts are unnecessary for immunisation. However,

copyright owners may try to expand the scope of the rule to infer

intent from design by arguing that a failure to filter proactively

is an indication of intent to infringe. Each of these unresolved

issues creates uncertainty on the part of developers regarding what

are the ground rules for an innovator in terms of permissible

designs and business models.

It is

likely that future indirect liability lawsuits will include an

intent to infringe component. Thus, it is likely that the active

inducement theory will increase the costs of litigation.21

All of a developer’s internal and external correspondences

will be analysed for signs of promoting infringement. Wu suggests

that it will be more difficult for defendants to win on summary

judgment and thus face the increased costs and uncertainty of a

trial.22

It also might encourage developers to pay off copyright owners for

peace thus making it more difficult for small innovators to survive.

Summarising,

if a developer whose behavior provides no clear evidence of intent

to induce infringement and who produces a product that is capable of

substantial non-infringing uses, then the developer should be free

of indirect liability based on a combination of the Sony and

Grokster rules. This may be the case that applies to the

pending lawsuit against the most popular peer-to-peer company

LimeWire that is widely thought to be used for direct infringement.23

It is also true that LimeWire has failed to take any steps to filter

the files shared on its network but it does employ a design that is

decentralised like Grokster, thus foreclosing actual knowledge of

infringement and lack of control over its customers. In August 2006,

copyright owners sued LimeWire for various counts of indirect

infringement.24

LimeWire has also countersued the plaintiffs for anticompetitive

activities in the online distribution of music market.25

A

remaining scenario involves a developer who provides a service with

no obvious intent to infringe, that is capable of substantial

non-infringing uses, but who may possess actual knowledge of

specific acts of direct infringement.26

The Grokster opinion left this scenario unanswered. However,

the legality of this scenario is relevant to determining the

viability of emerging competitors in the online distribution market.

QUESTION

4: What are the ground rules for indirect liability of a video

sharing web site?

Viacom’s

$1 billion lawsuit against YouTube may be decided based on

legislatively created Section 512 rules contained in the Copyright

Act and/or judicial created rules outlined above.27

YouTube utilises a centralised server client architecture

suggesting that it possesses the right and ability to control the

actions of its customers. Viacom sued YouTube for three counts of

direct infringement and three counts of indirect infringement (one

each for inducement, contributory, and vicarious liability) while

YouTube is likely to seek immunisation based on Section 512 (c),

although the law is undeveloped as to whether Section 512 can

provide a safe harbor for direct infringement liability. Viacom

seeks damages from YouTube and, more significantly, a redesign of

the technology to proactively limit or reduce the placement of

infringing content on the web site. It appears that copyright owners

view YouTube today as a piracy business similar to Napster and

Grokster, that is, an online competitor that has built its business

model on facilitating or turning a blind eye to its customers’

access to significant amounts of infringing copyrighted content.

But, with the proper redesign, YouTube could transform itself into a

legitimate distribution platform for copyrighted content as well as

user-generated content.

The

developers of the YouTube video sharing technology created a service

that its customers can use for both non-infringing and infringing

purposes. Given the relatively large volume of user-created content

uploaded to the web site, it would appear that the service is

capable of substantial non-infringing uses and thus should pass a

reasonable interpretation of the Sony test for a new dual use

technology.28

In light

of the original purpose of video sharing sites, YouTube should be

viewed as a legitimate business and not as a business intended to

facilitate predominantly copyright infringement as many viewed

Napster, Grokster, and their ilk. Thus, invoking the Grokster

rule, there appears to be little evidence of “clear expression

or other affirmative steps” taken by YouTube with the intent

to facilitate direct infringement by its customers. YouTube appears

to meet the criteria of a good-faith innovator.29

It has not promoted its service to target an audience predominantly

interested in infringing behavior and its business model is not

based on generating revenue tied to massive infringement. Although,

it does not proactively filter uploaded content (other than for

pornographic and hateful material), this, by itself, according to

the Grokster opinion, is not sufficient to suggest an act of

active inducement. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that

YouTube acts in good faith with no intent to induce direct

infringement. But, the interrelationship between the design of the

service and the burden of responsibility for filtering is a

continuing critical issue for innovators.30

Copyright

owners would like it to be the responsibility of video sharing sites

(and peer-to-peer networks as well) to police sites proactively for

infringing content. At first glance, this would seem to be

consistent with the approach taken in the Napster litigation. The

courts found that, given the design of its network, Napster had

control over how its customers used its service and if copyright

owners properly notified Napster of the presence of infringing files

on its index, it was deemed responsible for blocking access to those

files. It is important to recall that Napster was required to

respond to notification of infringing files and not to proactively

screen its index before such notification. In the case of YouTube,

it is unambiguous that when properly notified of the presence of

infringing content on its web site, the content is expeditiously

taken down in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Section

512 of the Copyright Act. Thus, the position that the web site must

proactively police the site for infringing content would alter the

existing burden of responsibility in the rules that technology

developers must follow.31

A complicating factor in the analysis is the assertion that YouTube

does proactively filter content if it has negotiated a licensing

agreement with a copyright owner.32

Thus, it may be possible to conduct such preemptive filtering but

it does not appear to be required by law to do so. Hopefully,

developers will continue to be free to invent new distribution

platforms without worrying about whether the innovation negatively

impacts the business models used by existing distribution channels.

Requiring developers to consider ex ante alternative designs of

their technology based on fear of litigation ex post opens up the

door to second guessing by courts and complicates the innovative

process by seemingly requiring the presence of lawyers on the

research and development teams. In turn, uncertainty about the

ground rules is likely to decrease the amount of online innovation

and solidify the position of entrenched incumbents.

The

design of new video sharing sites appears to be following the

decentralisation pattern of peer-to-peer networks. YouTube bundles

together the hosting of the uploaded video files on its own servers

and an index to locate those files. But, entrants such as

YouTVpc.com unbundled its service for it is only a video linking

site whereas content is stored at remote sites such as Dailymotion

in France and Ouou.com in China.33

Copyright owners have initiated legal action against linking sites

but have discovered that sites have re-entered the linking market

after being shutdown.

In sum,

the following rules provide a relatively certain environment for

innovators of dual use technologies that should promote competition

and the progress of science and the useful arts:

Create

a dual use technology that is capable of substantial non-infringing

uses for this technology should create significantly increased

value for society.

Create

a technology with good intent to satisfy a market associated with a

non-infringing purpose.

If

the developer of a technology is notified by copyright owners of

specific instances of infringement when and if the developer can

intervene to prevent that infringement, the developer’s

design should be adjusted to reduce or eliminate the infringing

uses without interfering with the non-infringing uses if it can be

accomplished in a cost-effective manner. This process implies that

it is the responsibility of copyright owners to monitor networks

and sites.

A

developer of a new technology is not under any obligation to design

a product/service ex ante in a particular way to accommodate the

desires of incumbent competitors.34

Rather, the design should be consistent with the existing

legislative and judicial rules as they are understood. A new

technology that merely redistributes existing value should not be

subject to liability for that reason alone.

4.2 Direct Liability Strategies

Starting

in 2003, copyright owners pursued a strategy of suing individuals

who used free peer-to-peer services alleging direct infringement of

the reproduction and presumptively distribution rights.35

Legal action against individuals is not confined to the United

States. The International Federation for the Phonographic Industry

has brought legal action against more than 3,800 individuals in

sixteen countries besides the United States.36

Copyright owners face a daunting task for it is estimated that

about 15 million United States households used unlicensed

peer-to-peer networks in 2006 to download a song.37

In any file sharing transaction, there is an uploading peer

computer (supply side) and a downloading peer computer (demand

side).38

Three economic effects could result when a consumer downloads

content from peer-to-peer networks:

(1) Downloaded content substitutes for purchases that the consumer

otherwise would have been willing to make at market prices

(substitution effect),

(2) Downloaded content represents consumption of content that the

consumer possesses a willingness to pay that is less than the market

price but above the marginal cost of distribution (consumer welfare

effect), or

(3) Downloaded content represents sampling of content that may

eventually lead to a willingness to pay for the content at market

prices as a result of experiencing the content (sampling effect).

Reason

(1) is damaging in the short run to the copyright owners’

profitability and should be the focus of a litigation strategy if

the goal of the campaign is to recapture lost sales. In addition, in

the long run, this drop in revenue may diminish the incentive to

create new content. Reason (2) represents increased consumer welfare

with no resulting loss of revenue to content owners since consumers

value the product at less than the market price but above the zero

marginal cost of distribution.39

Thus, downloading that meets this condition results in an increase

in consumer welfare for it causes a reduction in deadweight loss.

Reason (3) represents potentially increased revenue for copyright

owners and increased utility for consumers.40

A goal to

reduce infringement in general is aimed at reducing downloading for

all three reasons while a more focused goal to maximize profits

would target litigation efforts against consumers predominantly

using peer-to-peer networks for reason (1). Pursuing the latter goal

of reducing the substitution effect means that litigation efforts

would attempt to raise the expected cost of using peer-to-peer

networks or video sharing web sites for those marginal consumers

most likely to have a willingness to pay market prices. After

building a consumer choice model for file sharing and analysing the

music industry’s litigation strategy that focused its

litigation resources on high volume uploaders, Sag offers the

following demand side recommendation: “It makes much more

sense for the recording industry to target more marginal file

sharers because they are more likely to be persuaded to stop file

sharing and start buying music.” Hence, this recommendation is

reflected in the title of his article designating such presumably

marginal file sharers as twelve year-olds and grandmothers.41

Focusing

on a supply side strategy, Bhattacharjee, Gopal, Lertwachara, and

Marsden provided empirical evidence on the effect of the music

industry’s legal actions on individual file sharing behavior

in the time period 2003-04.42

The hypotheses in the study are that an event that is perceived to

increase the threat of legal action against individual file sharers

is expected to reduce the number of music files shared and to reduce

the frequency of time that an individual is online.

The

authors followed 2,056 users of the Kazaa P2P file sharing program

and examined their behavior before and after the following events:

(1) announcement of intention to pursue legal action (6/26/2003),

(2) lawsuits filed against 261 individuals (9/8/2003), (3) court

ruling against the legal process the music industry used

(12/19/2003), and (4) additional lawsuits filed using the more

complex legal process (1/21/2004). The focus of the legal action was

directed toward the supply side of the market and in particular on

those who share large amounts (referred to as substantial sharers)

of copyrighted music. The good news for the record industry is that

the empirical analysis finds general support for the two hypotheses.

Individuals reduced sharing activity and substantial sharers

decreased the number of files shared (to below the threshold/threat

level, 800 or 1,000 files shared) in response to the three negative

events for file sharers. The bad news is that there still existed a

large supply of copyrighted files. The authors conclusion is that,

“At the present time, what we can say is that the previously

substantial sharers are still tending to still actively share

(albeit fewer files), and downloading options still abound for those

seeking to download.”43

In sum, a reasonable conclusion is that the supply side strategy is

generally ineffective for it probably disproportionately directs

litigation resources on individuals unlikely to switch to paid

licensed online services and it does not significantly reduce the

ability of downloading consumers to find content, especially popular

content.

Currently,

copyright owners are focusing direct litigation attention on

university and college students who they consider as major users of

unauthorised peer-to-peer networks and who use these services as

substitution for purchasing copyrighted content. The new approach is

first to send pre-lawsuit letters to colleges and universities who

in turn are expected to notify students that copyright owners have

identified them as engaging in direct infringement. The copyright

owners offer college students discounts on settlements before

proceeding to the second step of a copyright suit. In addition, if

universities fail to employ voluntarily technology to filter their

students’ data packets, then they might lose their safe harbor

as an Internet Service Provider under Section 512 because copyright

owners threatened to go to Congress to narrow the safe harbor.44

An

advantage of direct suits compared to indirect suits is that they

attack only presumptively infringing use and do not have the

potential to reduce or eliminate non-infringing uses at the same

time. But such suits come at a considerable cost estimated to be

about $250,000 for a low-stakes case.45

Perhaps more of a long term concern to copyright owners is that the

risk of legal action against file sharers does not seem to be

changing the attitude of college students toward file sharing. It is

estimated that, although aware of the issue, 67% of college students

are not concerned with the ramifications of illegal downloading.46

5. Conclusion

Consumers

of digital content are experiencing increasing options for

accessing content online. Some of theses options are

licensed/authorised by copyright owners while others are

unlicensed/unauthorised. Unlicensed peer-to-peer networks and video

sharing sites are likely to continue to be significant challengers

to the copyright owners’ preferred/sanctioned methods of

centralised distribution for the online distribution of all forms of

digital content. The increasing decentralisation and growth of

peer-to-peer networks and video sharing web sites demonstrate that

these distribution platforms are resilient to copyright owners’

legal challenges and attempts to pollute shared file networks.

Legal

decisions centering on the rights of copyright owners influence the

path and nature of technological innovation in online distribution.

Software developers react to legal rules by attempting to redesign

online networks to insulate themselves from the costs of indirect

liability litigation. At the same time, legal decisions influence

the nature and extent of competition in the provision of online

distribution of digital content. In general, legal decisions have

resulted in technological innovation in network design becoming

increasingly decentralised. However, recent court decisions leave

unanswered key questions as to the legality and responsibilities of

certain network designs. The Viacom-YouTube litigation promises to

address some of these questions.

Copyright

owners will continue to assess the benefits and costs of alternative

legal strategies to protect their intellectual property. As the

probability of judicial wins on the indirect liability front

diminishes, it is likely that direct infringement suits targeted

against individuals that are willing to pay market prices for

digital content but instead substitute non-paying delivery services

will become more attractive.