Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) >> Gonzalez & Ors v Financial Conduct Authority (FINANCIAL SERVICES - market abuse - placing and cancellation of "large" orders in BTP Futures on the Eurex Exchange which overlapped with small orders placed by the applicants on the opposite side - whether "large" orders give false or misleading impression or signal to other market participants - whether placed as part of an abusive scheme to facilitate execution of small orders or a legitimate trading strategy being pursued) [2025] UKUT 214 (TCC) (01 July 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/TCC/2025/214.html

Cite as: [2025] UKUT 214 (TCC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number [2025] UKUT 214 (TCC)

UT (Tax & Chancery) Case Number: UT-2022-000134

UT-2022-000135

UT-2022-000137

Upper Tribunal

(Tax and Chancery Chamber)

FINANCIAL SERVICES - market abuse - placing and cancellation of “large” orders in BTP Futures on the Eurex Exchange which overlapped with small orders placed by the applicants on the opposite side - whether “large” orders give false or misleading impression or signal to other market participants - whether placed as part of an abusive scheme to facilitate execution of small orders or a legitimate trading strategy being pursued - held - references against prohibition orders dismissed - amount of penalties determined

Hearing venue: The Rolls Building

London

EC4A 1NL

Heard on: 27 to 31 January 2025, 3 to 7, 11 to 14 February 2025

Judgment date: 01 July 2025

Before

JUDGE JEANETTE ZAMAN

MEMBER GARY BOTTRIELL

MEMBER PETER FREEMAN

Between

(1) MR JORGE LOPEZ GONZALEZ

(2) MR POOJAN SHETH

(3) MR DIEGO URRA

Applicants

and

THE FINANCIAL CONDUCT AUTHORITY

Respondent

Representation:

For Mr Urra, Andrew George KC and Ava Mayer, counsel, instructed by Mishcon de Reya LLP

For Mr Lopez, Ben Jaffey KC and Celia Rooney, counsel, instructed by Stephenson Harwood LLP

For Mr Sheth, Alex Bailin KC and Jason Mansell, counsel, instructed by Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP

For the Authority: Sharif Shivji KC, Lara Hassell-Hart and Nicholas Wright, counsel, instructed by The Financial Conduct Authority

Decision Notices and Authority’s amended statements of case. 4

Traders’ Replies and outline of trading strategies relied upon. 11

Non-disciplinary references. 16

Burden and Standard of proof 17

Outline of evidence before the Tribunal 18

Pace of Authority’s investigation and particularisation of its case. 20

Lack of information that would have been available to the Traders during the Relevant Period. 22

Passage of time, memory and witness evidence. 27

Potential witnesses who were not called by the Authority. 30

EGBs, market making, BTPs and BTP Futures. 37

The Traders - roles at MHI and experience. 39

MHI and the EGB Trading Desk. 41

Interviews with Compliance. 50

Investigation by MHI Compliance. 51

Interviews by the Authority. 55

Traders’ explanations of rationale for the Large Orders. 56

Trading Activity of the Traders in the Relevant Period. 59

Trading Activity of the Traders outside the Instance Pool 64

Trading Activity of other participants in the market 65

Evaluation - Whether Large Orders are likely to impact the market 66

Tribunal’s assessment of the Experts. 67

Summary of evidence of Mr Creaturo. 69

Whether Large Orders may influence other market participants. 73

Conclusions on market impact 75

Evaluation - Whether traders committed market Abuse. 77

Criteria used to identify the Instance Pool 80

The Trading Strategies - contemporaneous explanations. 84

Information Discovery Strategy - plausibility. 89

Information Discovery Strategy - operation. 95

Conclusions on the Information Discovery Strategy. 104

Anticipatory Hedging Strategy - plausibility. 104

Anticipatory Hedging Strategy - operation by Mr Lopez. 113

Conclusions on the Anticipatory Hedging Strategy. 117

Placing of concurrent Large Orders. 118

Plausibility of Authority’s case that the Traders conducted an abusive scheme. 130

Trading Activity of the Traders in the Relevant Period. 138

Conclusions on Market Abuse. 147

Step 2: The seriousness of the breach. 162

Step 3: Mitigating and aggravating factors. 163

Step 4: Adjustment for deterrence. 164

Step 5: Settlement Discount 164

Authority’s determination of the penalties to be imposed. 164

Assessment of the financial penalty. 164

Statement of agreed background facts. 174

Hedging and trading BTP futures on EUREX.. 175

DECISION

Introduction and summary

1. On 31 October 2022 the Financial Conduct Authority (the “Authority”) through its Regulatory Decisions Committee (“RDC”) issued Decision Notices to each of Diego Urra (“Mr Urra”), Jorge Lopez Gonzalez (“Mr Lopez”) and Poojan Sheth (“Mr Sheth”) (together, the “Traders”). In those Decision Notices the Authority decided to make orders prohibiting each of the Traders from performing any function in relation to any regulated activity carried on by an authorised person, exempt person or exempt professional firm pursuant to s56 Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA 2000”), and imposed penalties on each of them pursuant to s123(1) FSMA 2000.

2. Each of the Traders referred their respective Decision Notices to the Tribunal. This decision concerns the subject matter of those references, which were heard together.

3. The Traders were traders at Mizuho International Plc (“MHI”). The Authority’s case is that the Traders pursued an abusive trading strategy in relation to Long-Term Italian Government Bond Futures (“Futures” or “BTP Futures”) on 233 occasions (between the three of them) between 1 June 2016 and 29 July 2016 (the “Relevant Period”). This abusive strategy is alleged to have involved placing orders of at least 200 lots (the “Large Orders”) which gave the false or misleading impression and/or signal that the Traders wanted to buy or sell a specified number of Futures, when in fact their objective was to facilitate the execution of other (genuine) smaller orders (generally of fewer than 200 lots) on the opposite side of the order book (the “Small Orders”). The Authority’s case is that this constituted market abuse within s118 FSMA 2000 and market manipulation within Article 12 of Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 (the “Market Abuse Regulation”). The Tribunal uses “market abuse” to refer to both market abuse and market manipulation within these regimes.

4. Each of the 233 occasions is referred to as an “Instance”, ie that is the term used to capture the trading activity on which the Authority relies. The 233 Instances are together the “Instance Pool”, those Instances involving orders placed by one Trader are “Single Trader Instances”, and those where orders (whether Small Orders or Large Orders) are placed by more than one of the Traders are “Multi Trader Instances”. There are a total of 341 Large Orders in the Instance Pool.

5. The Traders do not dispute the details of the activity within the Instances. They deny they committed deliberate market abuse, and submit they did not act dishonestly or lack integrity, as alleged by the Authority. The Traders each say that they placed each large order (ie the Large Orders and other large orders outside the Instance Pool) in pursuit of a legitimate trading strategy, they intended to trade their Large Orders and there was no collaboration (such that the Authority’s approach of identifying and relying on Multi Trader Instances is misguided). They have put forward their explanations for their trading strategy (for Mr Urra and Mr Sheth, the Information Discovery Strategy, and for Mr Lopez, the Anticipatory Hedging Strategy) and sought to explain their trading by reference to available evidence (and drawing attention to information that is no longer available).

6. The parties have produced a Statement of Agreed Background Facts (“SOABF”) which is set out at Appendix 1 and forms part of this decision. We use the terms as defined in the SOABF in this decision. The SOABF covers the cash BTP market, client RFQs, hedging and trading in Futures on the Eurex Exchange (“Eurex” or “the Exchange”), MHI and the EGB Desk, and includes a glossary.

7. On terminology in relation to the orders placed by the Traders, the parties have at various times used different defined terms for what we have referred to above as the Small Orders and Large Orders (which was adopted by the Authority and Mr Bailin by the time of the hearing, with Mr George and Mr Jaffey referring to the Large Orders as “Larger Orders” and “Relevant Orders” respectively). The Authority had previously defined these as the “Genuine Orders” and the “Misleading Orders”, and that is the language used in their statements of case (and subsequent amendments thereto). The Tribunal recognises that the terms Small Orders and Large Orders are not neutral - the Traders’ position is that the orders which are relied upon by the Authority as having given a false impression and/or signal, whether of 200, 450 lots or 500 lots, are not “large” but medium-sized.

8. The Tribunal has recognised throughout that whilst the Authority’s case is that the Traders individually and acting together committed market abuse by placing orders they did not wish to trade but whose purpose was to facilitate the execution of the Small Orders, we need to reach a conclusion in relation to each of the Traders. We have taken account of and assessed the activity of each trader individually as well as alongside that of the other Traders in the Instances when assessing their explanations for their trading.

9. For the reasons set out below, the Tribunal has concluded that the Traders each deliberately engaged in market abuse, and that this conduct was dishonest and lacked integrity. The Traders’ references against the prohibition orders are dismissed. The Tribunal determines that the appropriate action for the Authority to take is to impose a financial penalty of the following amount on each of the Traders and the references are remitted to the Authority with the direction that effect be given to our determinations:

(1) Mr Urra - £223,400;

(2) Mr Lopez - £100,000; and

(3) Mr Sheth - £57,600.

10. The Tribunal is grateful to the parties for their written and oral submissions. We have not found it necessary to refer expressly in this decision to all of the evidence and submissions but we have taken them all into account.

11. There was, as is to be expected, some overlap between the submissions made on behalf of each of the Traders, albeit that some submissions were distinct (eg the difference in the trading strategies between Mr Urra and Mr Sheth on the one hand and Mr Lopez on the other, the size and number of Large Orders placed by Mr Lopez, the issue of Mr Sheth’s level of experience and the submissions in relation to Mr Sheth’s placing of multiple overlapping Large Orders). We do specifically refer to some of the submissions as having been made by counsel for one of the Traders; we do not lose sight of the fact that the same or a similar submission was also made on behalf of another Trader.

Decision Notices and Authority’s amended statements of case

12. The Authority issued Decision Notices to each of the Traders on 31 October 2022.

13. Whilst the Authority relied on a different number of Instances for each Trader, the basis of the Authority’s decision was the same for each Trader, being that:

(1) The Traders undertook an abusive trading strategy in Futures on the Eurex Exchange, alone and in collaboration with each other. They would place a large sized order on one side of the order book for the purpose of creating the impression of increased supply or demand, with the objective of assisting the execution of a smaller genuine order they wished to trade on the opposite side of the order book. Once the smaller genuine order had been executed, they would cancel the large order. Through the placement of these large misleading orders the Traders falsely represented to the market an intention to buy or sell when their actual intention was the opposite. The only purpose of the large orders was to assist the execution of the smaller genuine orders that the Traders wanted to trade. The abusive trading strategy was such that it was unlikely the large misleading orders would themselves trade; notably, they were placed away from the touch and were quickly cancelled.

(2) This conduct gave false and misleading signals (there being no material difference between this concept and that of a false and misleading impression) to the market as to demand and supply. It amounted to market manipulation. The Traders frequently repeated this pattern of abusive conduct during the Relevant Period.

(3) The Traders knew that placing large orders on the opposite side of the book to assist the execution of other orders they or another Trader genuinely wanted to trade would result in false and misleading signals to the market; and they knew that this would be likely to impact the trading activities of other market participants. Their conduct constituted deliberate, intentional and repeated market manipulation and was dishonest.

14. The Authority considered that the conduct of each Trader in deliberately engaging in market manipulation was dishonest and lacked integrity. This dishonest conduct was highly likely adversely to impact other market participants and was repeated many times over a period of two months. As a result, they were each not a fit and proper person to perform any function in relation to any regulated activity carried out by an authorised person, exempt person or exempt professional firm.

15. The Authority decided to make orders prohibiting each of the Traders from performing any function in relation to any regulated activity carried on by an authorised person, exempt person or exempt professional firm, and imposed penalties on each of them: £395,500 on Mr Urra, £100,000 on Mr Lopez and £100,000 on Mr Sheth.

16. The Authority’s amended statements of case for each Trader are dated 6 December 2024 (together, the “Amended Statements of Case”) and are substantially similar to each other, in that the Authority relies on the same features as supporting its allegations of an abusive trading strategy in respect of the Large Orders in the Instance Pool and then identifies the number of occasions on which each Trader is alleged to have committed market abuse.

|

|

Single Trader Instances |

Multi Trader Instances |

No of Large Orders in Instance Pool |

|

Mr Urra |

31 |

97 |

135 |

|

Mr Lopez |

41 |

84 |

55 |

|

Mr Sheth |

47 |

57 |

151 |

18. The Amended Statements of Case proceed by identifying the “Facts and Matters relied upon by the Authority” and starts by setting out matters under the sub-headings of “The BTP and BTP Futures Market”, “The EGB Desk and its Mandate”, “BTP Trading and the EGB Desk’s process”, “Trader Remuneration” and “Training and Awareness of Market Abuse”. The Amended Statement of Case in respect of Mr Urra’s reference then sets out the following:

“Abusive Trading Strategy

58. During the Relevant Period, Mr Urra undertook an abusive trading strategy, both alone, and in collaboration with Mr Lopez and/or Mr Sheth. The abusive strategy involved placing orders for the purpose of giving the false or misleading impression and/or signal that the Traders wanted to buy or sell a specified number of BTP Futures lots (the “Misleading Orders”), when in fact the Traders did not intend to trade these orders, but instead intended or hoped to facilitate the execution of other genuine orders on the opposite side of the order book (the “Genuine Orders”). Misleading Orders which appeared to increase supply would encourage other market participants who wanted to sell to cross the spread and trade with existing buy orders in anticipation of the market moving lower (and vice versa for Misleading Orders which appeared to increase demand and might prompt the market to move higher).

…

61. That the trading carried out by Mr Urra (alone or in collaboration with Mr Sheth and/or Mr Lopez) gave or was likely to give a false or misleading impression and/or signal as to the supply of, demand for, or price of, BTP Futures, and was therefore abusive, is to be inferred from one or more of the following features:

61.1 The Misleading Orders were orders of BTP Futures showing 200 lots or more on the Exchange (“Large Orders”). Large Orders were rarely placed on the Exchange (see further paragraph 63.1 below) and were large compared to the Genuine Orders. They therefore gave or were likely to give an impression and/or signal of significant supply/demand to other market participants on the opposite side of the order book from the Genuine Orders.

61.2 None of the Misleading Orders were placed as Iceberg Orders, whereas some of the Genuine Orders (despite typically being significantly smaller) were placed as Iceberg Orders. By showing the full size of the Misleading Orders, this gave or was likely to give an impression and/or signal of significant supply/demand to other market participants on the opposite side of the order book from the Genuine Orders.

61.3 The vast majority of Misleading Orders were placed near enough to the Best Bid or Best Offer to be visible to other market participants (and thereby increase the pressure on the order book) but not so close that they were likely to be traded.

61.4 None of the Misleading Orders fully executed, and only 3 partly executed. In those 3 cases, only a very small minority of the order traded (under 10%) before being cancelled. Moreover, in each instance where the Misleading Orders began to trade, they were cancelled under 10 seconds later. By contrast, in each trading instance particularised in Amended Annex I, the Genuine Orders together mostly or fully executed prior to the cancellation of the Misleading Orders; the overall execution rate across the total volume of Genuine Orders before the cancellation of the Misleading Orders was 95%.

61.5 The Misleading Orders always overlapped with at least one Genuine Order on the other side of the book. Save for one instance, the last Misleading Order(s) on the order book in a particular instance were cancelled after the majority of the Genuine Order had filled, on average 5 seconds after.

61.6 The Traders have not matched executed BTP trades or RFQs against the placing of their Misleading Orders in the BTP Futures market.

61.7 The volumes of the Misleading Orders were particularly large sizes, frequently placed in round numbers and/or repeated numbers of lots. Of the 36 Misleading Orders placed by Mr Urra acting individually across 31 instances, for example, 13 were lots of 444, 9 were lots of 450, 5 were lots of 490, and 3 were lots of 400. It is inherently unlikely when placing genuine orders for hedging purposes that there would be so many identical orders, since market-makers will seek to hedge the precise residual risk on their books from time to time.

61.8 The Misleading Orders were not netted off against the Genuine Orders on the other side of the book (for example, if the Genuine Order was to buy 10 lots and the Misleading Order was to sell 500 lots, they could have placed a sell order of 490 lots, but did not do so). It was more costly to trade on both sides than to net off, and in addition there was potential additional risk from movements in the price from failing to net off.

61.9 The volume and repeated pattern of these types of orders over the Relevant Period by all the Traders (alone and in conjunction with one another) indicates a deliberate strategy.

62. In relation to each of the occasions where Mr Urra is averred to have carried out the strategy in collaboration with Mr Lopez and/or Mr Sheth…, it is inferred from the contemporaneous activity of the other Traders in each of the instances specified and the matters pleaded at paragraph 55 above that they were working together to a common strategy.

63. That the Traders’ conduct was abusive is also to be inferred by comparing their behaviour with the trading and order placement of BTP Futures on the Exchange by other market participants during the Relevant Period. The former was markedly different from the latter:

63.1 Large Orders of BTP Futures were rarely placed on the Exchange by other market participants. Including MHI, 47 market participants placed Large Orders during the Relevant Period, accounting for 0.02% of the total number of orders placed on the Exchange during the Relevant Period.

63.2 Despite MHI being a small market player, trading less than 0.43% of the total traded volume of BTP Futures, the Traders placed more Large Orders than any of the other market participants and accounted for 23.24% of the total volume of Large Orders placed across the Relevant Period. However, the Traders rarely executed BTP trades or received client orders in BTPs that they could have wanted to hedge with these Large Orders.

63.3 While … the Traders placed significantly more Large Orders than other market participants, they had much lower execution rates of their Large Orders. The Traders partially or fully executed only 1.5% of their Large Orders, cancelling 98.5% without them having begun to execute (Mr Urra himself executed 0.8% of the total volume of Large Orders that he placed). By comparison, other market participants partially, or fully executed 72.28% of their Large Orders, cancelling only 27.72% of their Large Orders without them having begun to execute. It would likely have been possible for the Traders to execute a larger proportion of their Large Orders if it had been their intention for them to execute.

63.4 When the Traders placed Large Orders, they rarely priced them competitively, placing only 1.93% of them at the Best Bid or Best Offer price. In contrast, other market participants placed 80.34% of their Large Orders at Best Bid or Best Offer prices, or at improved prices. By placing their Large Orders away from the Best Bid or Best Offer price, the Traders were less likely to execute them.

…”

19. We refer to the features set out by the Authority at [61] in its Amended Statement of Case above as the “Criteria”. These Criteria were used by the Authority to identify the Instance Pool from the totality of the trading activity of the Traders during the Relevant Period.

20. The Authority then disputes the explanation provided by Mr Urra for his trading strategy pleading that it is “inherently improbable” and particularises its case using F150 as an example of a Single Trader Instance, and F31 and F209 as Multi Trader Instances before then setting out its position on the alleged breaches:

“Section 118 of FSMA

…

104. The Misleading Orders were not placed for legitimate reasons, nor did they conform with accepted market practice. In placing the Misleading Orders, Mr Urra gave or was likely to give a false or misleading impression as to the supply of, or demand for, the BTP Futures to which the Misleading Orders related. This was because in placing the Misleading Orders, Mr Urra signalled that he wanted to buy or sell a specified number of BTP Futures. In fact, he did not wish to trade in that manner and the purpose of placing the Misleading Orders was to facilitate the execution of Genuine Orders at a more advantageous price, or on a more timely basis, than would otherwise have been achieved but for his having misled other market participants by the Misleading Orders.

…

Articles 12 and 15 of the Market Abuse Regulation

…

107. Mr Urra’s misleading orders were not placed for legitimate reasons, nor did they conform with an accepted market practice as established in accordance with Article 13 of the Market Abuse Regulation. In placing the Misleading Orders (alone or in concert with Mr Lopez and/or Mr Sheth), Mr Urra gave or was likely to give a false or misleading signal as to the supply of, or demand for, the BTP Futures to which the Misleading Orders related. This was because in placing the Misleading Orders (alone or in concert with Mr Lopez and/or Mr Sheth), Mr Urra signalled that he wanted to buy or sell a specified number of BTP Futures. In fact, he did not wish to trade in that manner and the purpose of placing the Misleading Orders was to facilitate the execution of Genuine Orders at a more advantageous price, or on a more timely basis, than would otherwise have been achieved but for his having misled other market participants by the Misleading Orders.

…

Fitness and Propriety

109. Mr Urra’s conduct in deliberately engaging in market manipulation was dishonest and lacked integrity. This dishonest conduct was highly likely to adversely impact other market participants and was repeated many times over a period of two months. As a result, he is not a fit and proper person to perform any function in relation to any regulated activity carried out by any authorised person, exempt person or exempt professional firm.”

21. The Authority has pleaded its case on a substantially similar basis in respect of Mr Lopez and Mr Sheth, and in particular has relied on the Criteria and the comparison with trading and order placement by other market participants. In its Amended Statements of Case for Mr Lopez and Mr Sheth the Authority has used examples of Instances relevant to each Trader. We do not set those out here.

22. In addition to the number of Instances relied upon against each Trader, the only point of substantive difference in the Authority’s decision and pleadings relates to Mr Sheth, who had placed multiple concurrent Large Orders on the same side in some of the Instances (the “Multiple Large Orders”). The Authority alleged that each of these are Large Orders and its Amended Statement of Case in respect of Mr Sheth, having said his explanation for his trading strategy is “inherently improbable” sets out the following:

“64. …Mr Sheth has also suggested that in some cases, where he placed multiple, overlapping Large Orders, these were in fact intended to be amendments to an existing Large Order. Whether or not this is true does not affect the Authority’s assessment of the purpose of the placement of a Large Order on the opposite side of the order book to a small order.”

23. The 233 Instances have been set out in Annex 1 to the Amended Statements of Case as lists of the trading activity which occurred in each Instance (this Annex being the same for each Trader, albeit that the Authority does not rely on each Instance against each Trader).

24. Whilst the Authority has amended its statements of case since they were first served on 24 February 2023, and significant changes have been made to the level of detail provided in relation to the specific trading activity relied upon, the allegations set out above, in particular as to an “abusive trading strategy”, “deliberately engaging in market manipulation” and “dishonest and lacked integrity” have been pleaded throughout.

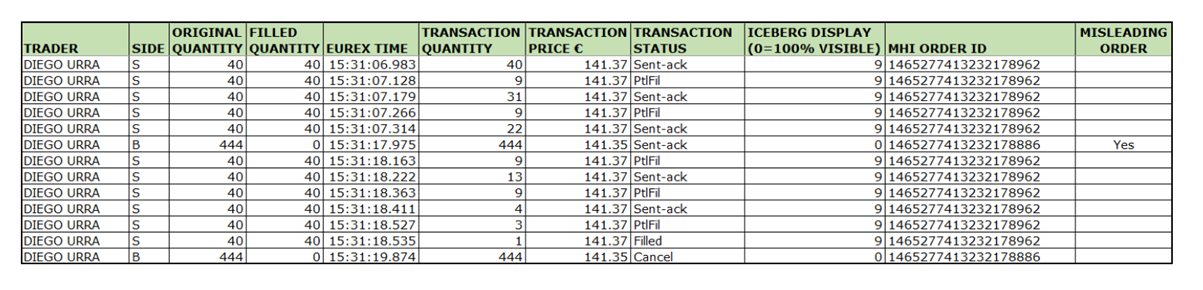

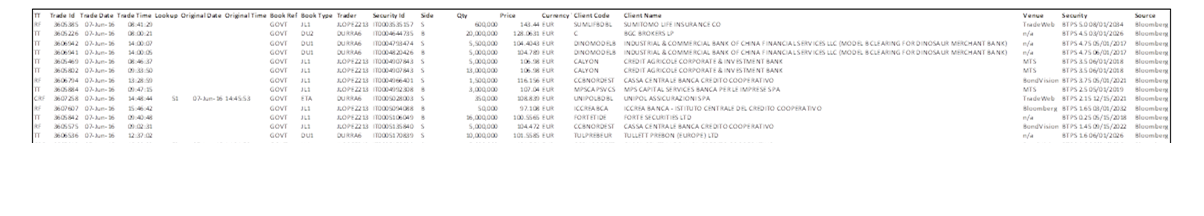

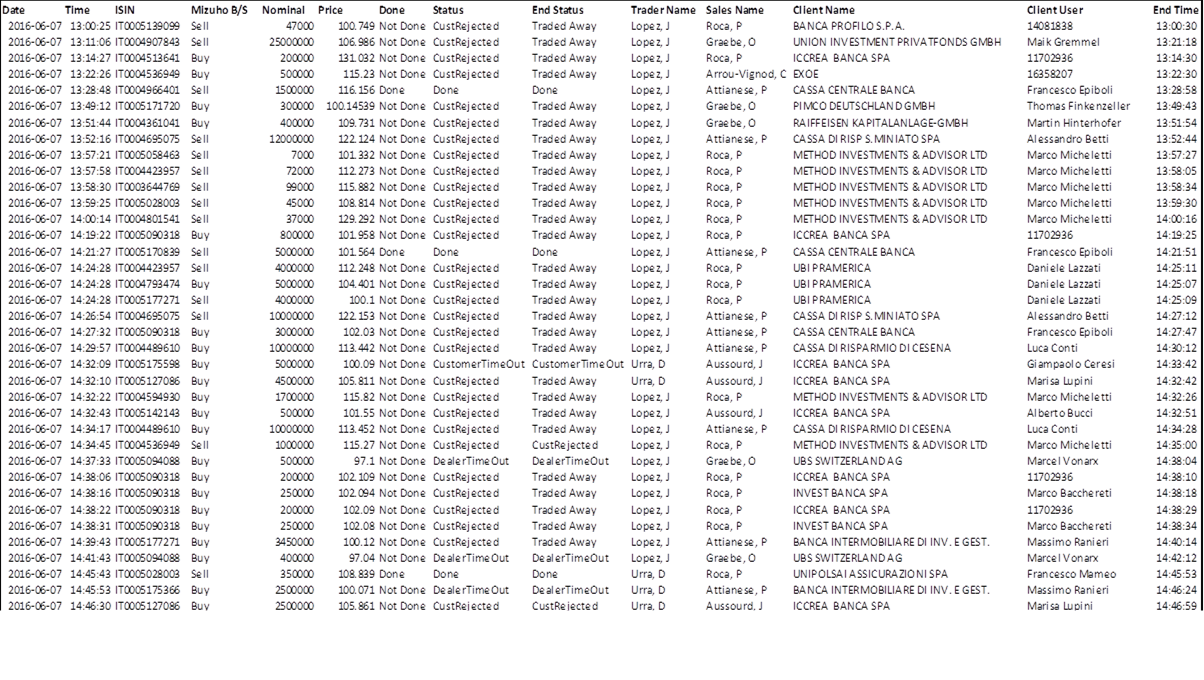

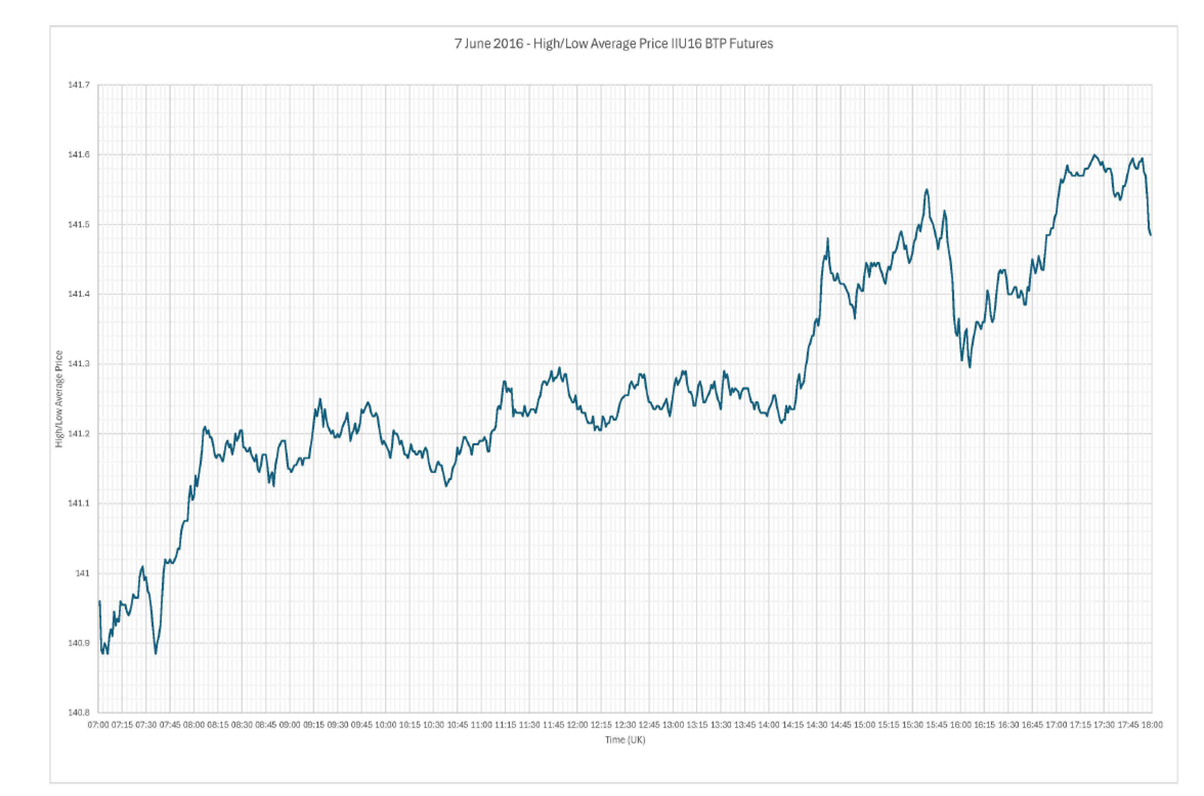

25. The Authority has further particularised its case since it first served its statements of case, and, since February 2024, has particularised each of the Instances. We have set out in Appendix 2 the Authority’s particularisation of one instance (F7, the first Specified Instance) to illustrate the data provided (but it should be noted that the narrative was only provided for the “Specified Instances”, namely those Instances which the Authority was directed by the Tribunal in June 2024 to identify to the Traders before the hearing and on which it would cross-examine the Traders). Appendix 2 also includes the daily price graph, Electronic RFQs submitted to the Desk and the executed cash bond transactions for that day, 7 June 2016.

26. By way of further explanation, for each Instance the Authority provided:

(1) overview table - A summary of the relevant Instance, identifying the Trader(s) involved and the date and time of the Instance;

(2) table of all trading activity by the Traders between the identified start and end time of the Instance relied upon by the Authority - Where an order had been iceberged, the placing of the subsequent slices are shown as a new order (and we refer to an order of, eg, nine lots which is iceberged to show slices of three lots as “iceberged to three”). Times of day in the trading activity are set out in Continental European Time (“CET”), and that is used throughout this decision notice;

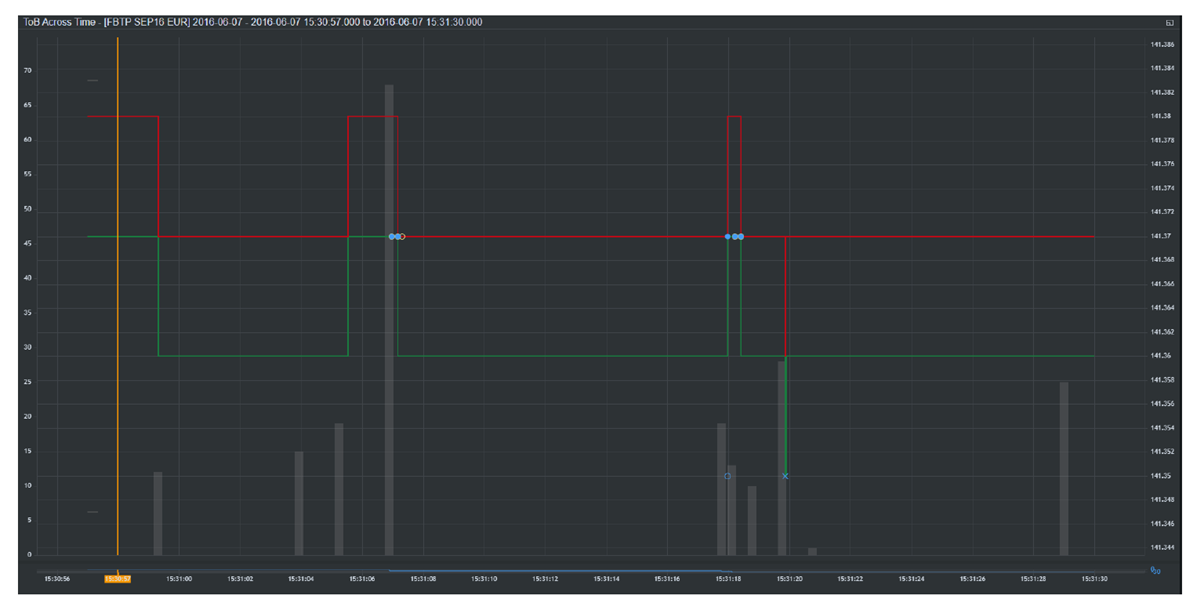

(3) “Spread graph” - This shows the Best Bid and Best Offer, highlighting the Traders’ orders and trades. These graphs were produced from Eurex data using the Authority’s data analysis system. Best Offer is shown by a red line, Best Bid by a green line, order entry is a circle, order amendment a diamond and order cancellation a cross. Where an order trades, that is shown by a solid circle. The grey shaded columns are levels of traded volumes; and

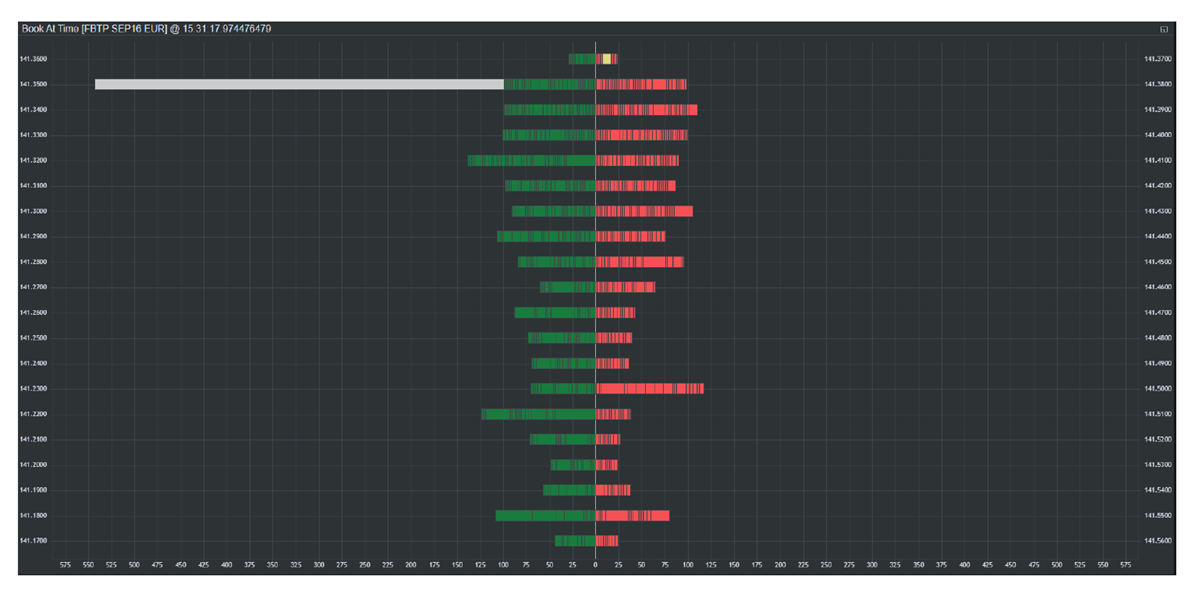

(4) “Replay graph” or “stack” - This shows the (visible) orders on Eurex at the point of entry of the Large Order, showing the size of orders and the Bid/Offer prices. Where an Instance includes more than one Large Order, there is a separate Replay graph for each Large Order entered. These graphs were also produced from the Eurex data using the Authority’s data analysis system. The offers on the buy side from other market participants are shown in green on the left-hand side, with the Best Bid at the top. The offers on the sell side from other market participants are shown in red on the right-hand side, with the Best Offer at the top. The Large Order on which the Authority relies is grey. Some Replay graphs had bars in blue (orders to buy) or yellow (orders to sell), and those are existing orders which had been placed by MHI on the book at that time. Where the Authority relied on more than one Large Order in an Instance, the most recent would be shown in grey but existing Large Orders would then be shown in blue or yellow (as applicable).

27. The basis on which the Authority has pleaded its case against the Traders is set out above. The Authority has not pleaded in its Amended Statements of Case that the Traders’ conduct was reckless, nor has it applied to the Tribunal to amend further its Amended Statements of Case to plead recklessness in the alternative.

28. The Authority served its written skeleton argument on 20 January 2025 in accordance with the Tribunal’s directions, and that included the following:

“42. In order to establish market abuse, the Authority does not need to go further than that and show that the Traders knew that they were committing market abuse or that they were acting in a way which was dishonest or reckless.

43. Whether the Traders behaved recklessly or dishonestly is however a consideration which arises in relation to the prohibition order … as well as being relevant to the level of penalty…”

29. Then, in a footnote to the Authority’s summary of the principles relevant to the imposition of a penalty, the skeleton included:

“FN147. For the avoidance of doubt, the Authority does not positively say that the Applicants’ conduct was reckless in circumstances where it is alleged to have been deliberate and dishonest. If, however, under its broad powers under s. 133(5), the Tribunal finds that market abuse is made out against the Applicants, but that their conduct fell short of being dishonest, the Tribunal will nevertheless have to address whether to apply a penalty against the Applicants and, if so, at what level. In order to address that question, it will have to consider the nature of their conduct, including whether it was reckless, on any view.”

30. In their opening submissions Mr George, Mr Jaffey and Mr Bailin each objected to this inclusion of a reference to recklessness in the Authority’s skeleton on the basis that the Authority has throughout imposed sanctions and pleaded its case on the basis that the Traders’ conduct was deliberate and dishonest. The parties made submissions in closing as to the jurisdiction of the Tribunal by reference to the decision of the Court of Appeal in Financial Conduct Authority v Bluecrest Capital Management (UK) LLP [2024] EWCA Civ 1125 and the Authority’s obligations under The Tribunal Procedure (Upper Tribunal) Rules 2008 (the “Upper Tribunal Rules”), in particular under paragraph 4(2)(c) of Schedule 3 that the Authority’s statement of case “set out all the matters and facts upon which the respondent relies” as well as to the principles relevant to the exercise of the Tribunal’s discretion to allow amendments and the Tribunal’s role under s133(4) to (7) FSMA 2000 on a reference.

31. On the basis of our decision on the Authority’s pleaded case, the Tribunal has not needed to address these issues further and does not do so.

Traders’ Replies and outline of trading strategies relied upon

32. The Traders have each denied being engaged in an abusive scheme. The Traders submit that they intended to trade each of the orders they entered and that the Large Orders (as well as all of the large orders which are outside of the Instance Pool) were placed pursuant to a legitimate trading strategy.

33. The strategies relied upon by the Traders were, in outline, as follows (this description being based on their Replies and the Traders’ subsequent witness statements):

(1) Mr Urra’s evidence was that he was pursuing what we refer to as an “Information Discovery Strategy” - MHI was a small market player, with less visibility over market activity and had an information disadvantage. He believed that clients might split a large order across more than one market maker and not tell each one that a larger order was being worked. By withholding the size of the total order, clients could benefit from more favourable pricing, before the market makers recognised the true extent of the trading activity. The risk to the EGB Desk was that it would not have a complete understanding of the price request and the market, and as a result the EGB Desk would misprice the trade. In this situation, other market makers, dealing with a possibly much larger part of the same client order, might now be exposed to significant risk and be looking to hedge their position promptly. He tried to test ways to exploit that situation, and theorised that what he described as a medium-sized order for Futures offered at a premium might be tempting for such a market maker. He had practical experience of such trades having occurred previously. In anticipation of demand, he placed a medium-sized order for Futures, with a direction based on the direction he expected the market maker would want to trade, and selected its price at a level he thought would be of interest to the market maker but represented a good deal for him if the order was transacted.

(2) Mr Sheth’s evidence was that he was also pursuing this “Information Discovery Strategy”, which he said had been shown to him by Mr Urra in May 2016 when Mr Urra had placed an order (on 12 May 2016) of 450 lots in Futures which filled. Mr Urra had explained to him that there were two reasons for the strategy - to obtain information as to whether there was hidden liquidity in the cash market and to create profitable positions - and had encouraged him to try it. Mr Sheth explained the Multiple Large Orders he placed as being “poor practice” and a mistake, arising as a result of his inexperience and lack of training in operating Bloomberg Escalator.

(3) Mr Lopez’s evidence was that he was pursuing an “Anticipatory Hedging Strategy”. He was looking ahead to what he predicted to be likely client demand, ie RFQs from clients, with particular emphasis on those of medium-size, and seeking to position his trading book and inventory of bonds to service that demand and be able to offer competitive prices. This was a constant process of assessing the levels at which anticipatory hedges would be attractive, relative to the RFQs he expected the Desk to receive.

34. We refer to the Information Discovery Strategy and the Anticipatory Hedging Strategy together as the “Trading Strategies”, recognising that these are strategies that the Traders say there were pursuing and that the Authority does not accept that they were pursuing any such strategies: the Authority submitted they are fabrications designed to fit the facts which are now known.

35. We set out here the relevant legal principles in relation to market abuse and dishonesty.

37. Until 2 July 2016, s118(1) FSMA 2000 provided:

“For the purposes of this Act, market abuse is behaviour (whether by one person alone or by two or more persons jointly or in concert) which -

(a) occurs in relation to –

(i) qualifying investments admitted to trading on a prescribed market,

(ii) qualifying investments in respect of which a request for admission to trading on such a market has been made, or

(iii) in the case of subsection (2) or (3) behaviour, investments which are related investments in relation to such qualifying investments, and

(b) falls within any one or more of the types of behaviour set out in subsections

(2) to (8). …”

38. “Prescribed market” and “qualifying investments” were defined by Articles 4 and 5 respectively of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Prescribed Markets and Qualifying Investments) Order 2001/996. The Eurex Exchange was a prescribed market and Futures were a qualifying investment.

39. Sections 118(2) to (8) of FSMA made provision as to the types of behaviour that constituted market abuse. Section 118(5) provided:

“(5) The fourth is where the behaviour consists of effecting transactions or orders to trade (otherwise than for legitimate reasons and in conformity with accepted market practices on the relevant market) which -

(a) give, or are likely to give, a false or misleading impression as to the supply of, or demand for, or as to the price of, one or more qualifying investments …”

40. The Market Abuse Regulation came into effect on 3 July 2016 and directly applied to the UK for the remainder of the Relevant Period.

41. Article 15 of the Market Abuse Regulation provided: “A person shall not engage in or attempt to engage in market manipulation.” Market manipulation was defined in Article 12 and Article 12(1) provided:

“For the purposes of this Regulation, market manipulation shall comprise the following activities:

(a) Entering into a transaction, placing an order to trade or any other behaviour which:

(i) gives, or is likely to give, false or misleading signals as to the supply of, demand for, or price of, a financial instrument …;

…

unless the person entering into a transaction, placing an order to trade or engaging in any other behaviour establishes that such transaction, order or behaviour have been carried out for legitimate reasons, and conform with an accepted market practice as established in accordance with Article 13”.

42. Article 12(2)(c) provided that the following behaviour shall, inter alia, be considered as market manipulation:

“the placing of orders to a trading venue, including any cancellation or modification thereof, by any available means of trading, including by electronic means, such as algorithmic and high-frequency trading strategies, and which has one of the effects referred to in paragraph 1(a) or (b), by:

…

(ii) making it more difficult for other persons to identify genuine orders on the trading system of the trading venue or being likely to do so, including by entering orders which result in the overloading or destabilisation of the order book; …”

43. Futures were financial instruments and the Eurex Exchange was a regulated market for this purpose (Article 2 of the Market Abuse Regulation).

44. Annex I of the Market Abuse Regulation sets out, without prejudice to the forms of behaviour set out in Article 12(1), further indicators of manipulative behaviour relating to false or misleading signals and to price securing which were to be taken into account by the Authority when transactions or orders to trade are examined. These included, at A(f) of Annex I:

“the extent to which orders to trade given change the representation of the best bid or offer prices in a financial instrument…or more generally the representation of the order book available to market participants, and are removed before they are executed”

45. Article 4 and Section 1 of Annex II of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/522 set out the practices which specify indicators A(a) to A(g) of Annex I of the Market Abuse Regulation. Paragraph 6 of Section 1 of Annex II provided that such practices included:

“(a) Entering of orders which are withdrawn before execution, thus having the effect, or which are likely to have the effect, of giving a misleading impression that there is demand for or supply of a financial instrument […] at that price - usually known as ‘placing orders with no intention of executing them’…

(g) The practice set out in Point 5(e) of this Section, usually known as ‘layering’ and ‘spoofing’;”

46. Point 5(e) was set out as:

“(e) Submitting multiple or large orders to trade often away from the touch on one side of the order book in order to execute a trade on the other side of the order book. Once the trade has taken place, the orders with no intention to be executed shall be removed - usually known as layering and spoofing…”

47. The Authority’s case here is that the Traders were spoofing.

48. The essential ingredient of market abuse under both s118 FSMA 2000 and the Market Abuse Regulation (for present purposes) is the giving of (or likelihood of giving) a false or misleading impression or signal as to supply, demand or price.

49. The question of what impression or signal has been given (or is likely to have been given) is an objective question. The Authority is not required to establish that a trader intended to manipulate the market, or to give any particular signal to others in the market (Financial Conduct Authority v Da Vinci Invest Ltd [2015] EWHC 2401 (Ch) (“Da Vinci”) at [107] and [156] and Winterflood Securities Ltd v Financial Services Authority [2010] EWCA Civ 423 at [17] and [25]).

50. The question of whether the signal that is given (or is likely to be given) is false or misleading may, however, entail a subjective analysis, as explained by Andrew Baker J in Burford Capital Ltd v London Stock Exchange Group plc [2020] EWHC 1183 (Comm) (“Burford”) in the context of the Market Abuse Regulation:

“50. Thus, the essential ingredient is the giving of (or likelihood of giving) false or misleading signals as to supply, demand or price. Contrary to a submission by Mr Dhillon QC, that cannot always be an entirely objective enquiry, as it depends upon the signal given out (or likely to be given out) by a particular activity or behaviour. Depending on what that signal is (an objective question, to be sure), falsity might involve some subjective enquiry. The point of substance, therefore, is whether, as Mr Dhillon contended, there is no subjective element in the supply, demand or price signalling involved in this type of case (or, therefore, in considering whether there was any false or misleading signal).

51. I do not accept that contention. A seller wishing to sell at £10 who offers to sell at £10 but, finding no takers at that price, withdraws his offer because he does not want to sell for less, and a seller who has no intention to sell at £10 but who offers to sell at £10 to initiate or exacerbate a price trend, then withdraws his offer, appear to the outside observer to have behaved identically. If their behaviour fell to be judged entirely by that appearance, they would have to be either both guilty or both innocent of a charge of market manipulation. But in reality, surely the former is innocent, the latter guilty, and that is because although the signals sent out were the same (eg their initially signalled intention to sell at £10), the truth or falsity of those signals turns on their actual intentions, which differed radically.

52. It is no defence for the guilty seller to say that he did not appreciate he was sending out a false signal, or in some other way that he did not intend to manipulate. In that sense, the manipulation does not have to be deliberate; and that is the relevant proposition to derive from Financial Conduct Authority v Da Vinci Invest Ltd [2015] EWHC 2401 (Ch), [2016] 3 All ER 547, [2016] Bus LR 274, per Snowden J at [104]–[108], decided under s 118 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (‘FSMA 2000’) implementing the EU Market Abuse Directive (European Parliament and Council Directive 2003/6/EC), which was the EU law predecessor to MAR. That is a different point, however, and the conclusion in that case, that there had been market abuse, required (and was justified by) the finding as to the actual purpose behind the relevant order activity (ibid, at [163]): ‘The purpose of the Traders was not in truth to sell or buy as indicated by the orders they placed. Instead, the Traders intended to cause a movement in the market price of the share … and to induce other market participants to place similar larger orders, with which the Traders could then trade aggressively in the opposite direction’.

53. Again, in my simple example, the time at which and market circumstances in which the initial offer to sell at £10 was placed might afford an argument that a seller looking to sell but unwilling to sell below £10 would have assessed that there was no sensible prospect an offer to sell at £10 might be matched and so would not have placed the offer. That might be an aspect of assessing the genuineness of the offer in fact placed, but it could not be a conclusion that foreclosed the inquiry. That MAR adopts that approach is confirmed by Pt A of Annex I, with its list of ‘non-exhaustive indicators’ to be ‘taken into account’ when examining transactions or orders to trade for the purpose of applying art 12(1)(a).”

51. Having considered the expert evidence, Andrew Baker J then emphasised:

“80. Then finally, to be clear, and applying what I said in paras [50] to [51] above, it is not the case that to find a pattern of repeated placement, cancellation and replacement is to find spoofing or layering, because the question remains one of intention to trade. For example, a trader wishing to sell off or reduce a long position, in response to the Muddy Waters tweets or simply in response to the price falling, might generate such a pattern as part of a best-execution strategy that aimed to maximise his average price traded while still selling the volume he wishes to sell. That execution strategy might or might not hit both of those targets; but if that is what he is doing, though he generates one of Prof Mitts’ patterns, he never gives out a false supply or pricing signal to the market since each of his sell orders is placed intending it to trade, each cancellation is a response to the lack of matching demand, and each replacement order is again placed intending it to trade.

81. Before getting into the detail, therefore, I am clear that Prof Mitts is wrong to opine that ‘repeatedly placing and cancelling orders in a very short time is strong evidence of manipulative intent’, or that ‘a wave of abnormal order cancellations [ie sell-side cancellations in statistically atypical volumes] at or above the best offer … indicates intentional manipulation of Burford’s share price’. Mitts 1 set out the logic for those claims, but it immediately betrays their error. The logic set out is that there is no economic justification for a short seller to place a large volume of sell orders above the best offer. The opinion that logic might justify, a more limited opinion than that expressed by Prof Mitts, is that a short seller repeatedly placing and cancelling orders in a very short time, above the best offer, is strong evidence of manipulative intent.”

52. Dishonesty is not part of the applicable test for determining whether a person has committed market abuse. It was the basis of the Authority’s pleaded case in relation to the imposition of the prohibition orders, with the Authority alleging that the Traders were dishonest and lacking integrity.

53. The judgment of the Supreme Court in Ivey v Genting Casinos Ltd [2017] UKSC 67 (“Ivey”) is the leading authority on the meaning of dishonesty, and Lord Hughes set out the approach as follows:

“74 …When dishonesty is in question the fact-finding tribunal must first ascertain (subjectively) the actual state of the individual’s knowledge or belief as to the facts. The reasonableness or otherwise of his belief is a matter of evidence (often in practice determinative) going to whether he held the belief, but it is not an additional requirement that his belief must be reasonable; the question is whether it is genuinely held. When once his actual state of mind as to knowledge or belief as to facts is established, the question whether his conduct was honest or dishonest is to be determined by the fact-finder by applying the (objective) standards of ordinary decent people. There is no requirement that the defendant must appreciate that what he has done is, by those standards, dishonest.”

54. Section 133(4) FSMA 2000 provides that, on a reference, the Tribunal may consider any evidence relating to the subject matter of the reference whether or not it was available to the decision-maker at the material time. This is not an appeal against the Authority’s decision on each of the references but a complete rehearing of the issues which gave rise to the decision and which the applicant wishes the Tribunal to consider. Section 133(5) to (7) provides as follows:

“(5) In the case of a disciplinary reference or a reference under section 393(11), the Tribunal must determine what (if any) is the appropriate action for the decision-maker to take in relation to the matter, and on determining the reference, must remit the matter to the decision-maker with such directions (if any) as the Tribunal considers appropriate for giving effect to its determination.

(6) In any other case, the Tribunal must determine the reference or appeal by either -

(a) dismissing it; or

(b) remitting the matter to the decision-maker with a direction to reconsider and reach a decision in accordance with findings of the Tribunal.

(6A) The findings mentioned in subsection (6)(b) are limited to findings as to -

(a) issues of fact or law;

(b) the matters to be, or not to be, taken into account in making the decision; and

(c) the procedural or other steps to be taken in connection with the making of the decision.

(7) The decision-maker must act in accordance with the determination of, and any direction given by, the Tribunal.”

55. Pursuant to s133(7A), “disciplinary reference” includes a decision to take action under s66 FSMA 2000, ie to impose a financial penalty on a person. The term does not include a decision to impose a prohibition order under s56. Thus, these references are disciplinary references in respect of the penalties imposed and non-disciplinary references in respect of the prohibition orders.

56. In the case of a non-disciplinary reference, the Tribunal must determine the reference by either: “(a) dismissing it; or (b) remitting the matter to the decision-maker with a direction to reconsider and reach a decision in accordance with the findings of the Tribunal” (s133(6)). It does not itself determine what the appropriate action is for the Authority to take.

57. Otherwise than in cases where the Tribunal dismisses the reference, its powers are confined to giving directions to the Authority to remake its decision in light of the matters within the scope of s133(6A) which the Tribunal considers appropriate (Page v Financial Conduct Authority [2022] UKUT 124 (TCC) (“Page”) at [113]).

58. Accordingly, as set out in in Carrimjee v Financial Conduct Authority [2016] UKUT 447 (TCC) at [39] to [40] and Page at [114] to [115], under s133(6), the Tribunal has various options when dealing with a “non-disciplinary” reference:

(1) It will dismiss the reference if either:

(a) having reviewed all the evidence and factors taken into account by the Authority in making its decision, and having made findings of fact in relation to that evidence and such other findings of law that are relevant, it concludes that the decision to prohibit is one which was reasonably open to the Authority; or

(b) it concludes that the seriousness of the Tribunal’s own findings would lead inevitably to the Tribunal reaching the same decision as the Authority in the event the decision was remitted back to the Authority, even where the Tribunal has not accepted all the factors relied upon by the Authority in reaching its original decision to make a prohibition order, such that it can be said to have taken into account irrelevant considerations.

(2) It will remit the decision to the Authority with directions if it is not satisfied that the decision made is one which, in all the circumstances, is within the range of reasonable decisions open to the Authority.

59. The Tribunal may have regard to any evidence, whether or not it was available to the Authority at the time.

60. A reference of a decision to impose a financial penalty is a “disciplinary reference” and the Tribunal has the power to determine at its discretion what (if any) is the appropriate action for the Authority to take, including a determination as to whether or not to impose a financial penalty and, if so, the amount of such penalty.

61. As the Tribunal indicated in Tariq Carrimjee v Financial Conduct Authority [2015] UKUT 79 (TCC), the Tribunal is not bound by the Authority's policy when making an assessment of a financial penalty on a reference, but it pays the policy due regard when carrying out its overriding objective of doing justice between the parties. In so doing the Tribunal looks at all the circumstances of the case.

62. Similarly, in Westwood Independent Financial Planners v Financial Conduct Authority [2013] 11 WLUK 630, the Tribunal held at [181]:

“In considering the appropriate level of a penalty we are not bound by the Authority’s tariff for particular misconduct, or even the factors the Authority takes into account, but may reduce or increase a penalty which is the subject of a reference on any grounds we think fit, within the parameters of the proper exercise of judicial discretion. In practice, the Tribunal respects the Authority’s tariff, in the interests of consistency between applicants, while departing from it in an appropriate case.”

63. This approach was adopted by the High Court in Da Vinci where Snowden J said in the context of the imposition of a penalty for market abuse at [201]:

“It was the FCA's submission, and I accept, that in determining any penalty under section 129, the starting point for the court should be to consider the relevant DEPP penalty framework that was in existence at the time of commission of the market abuse in question. To do otherwise would risk introducing an inequality of treatment of defendants depending upon whether the proceedings were taken against them under the regulatory route or the court route and depending upon how long the proceedings had taken to come to a conclusion. By the same token, however, in common with the Upper Tribunal, the court is not bound by that framework, or by the FCA's view of how it should be applied. But if the court intends to depart from the framework in a particular case, it should explain why it considers it appropriate to do so. It occurred to me that in this regard there is some analogy with the approach of the criminal courts to the application of the sentencing guidelines produced by the Sentencing Council.”

64. The burden of proof is on the Authority to establish the matters on which they rely, namely that the Traders deliberately engaged in market abuse and their conduct was dishonest and lacked integrity.

65. The standard of proof is the civil standard of the balance of probabilities.

Evidence including witnesses who had not been called, information that is no longer available and relevance of delay

66. The Traders made submissions in relation to the witnesses who had not been called by the Authority to give evidence before this Tribunal, the information that would have been available to the Traders during the Relevant Period but which is no longer available or has not been disclosed to them and the time which has passed since the Relevant Period (more than 8.5 years by the time of the hearing). They submitted that the Tribunal should draw adverse inferences from the Authority’s failure to call witnesses, and that the delay and absence of information that would have been available to the Traders at the time was unfair and prejudicial to the Traders, particularly in circumstances where the Authority’s case was based on detailed trading activity within the Instance Pool and they were cross-examined on the reasons for placing particular orders within that Instance Pool.

67. We first set out a summary of the evidence which was produced, before then addressing these submissions and setting out the Tribunal’s approach to the evidence.

68. When considering the parties’ submissions in relation to the evidence the Tribunal keeps in mind throughout that in regulatory proceedings the Authority is not an ordinary litigant but is instead engaged in a “common enterprise” with the court in ensuring that the objects of the legislation are achieved and that public confidence is maintained in the integrity of the financial markets (Financial Conduct Authority v Seiler [2024] EWCA Civ 852 at [51]).

Outline of evidence before the Tribunal

69. We heard evidence from the Traders, each of whom had provided witness statements and were cross-examined by Mr Shivji on behalf of the Authority and, in the case of Mr Urra, also by Mr Bailin on behalf of Mr Sheth. The latter cross-examination was confined to whether Mr Urra recalled either showing the Information Discovery Strategy to Mr Sheth and/or a subsequent discussion with Mr Sheth in relation to which Mr Sheth’s evidence was that he expressed his frustration that the strategy was not working.

70. In cross-examination Mr Shivji put the Authority’s case to each of the Traders, both in general terms by reference to the Authority’s allegations that their Trading Strategies were fabricated, and specifically by reference to some of the Instances and other trading activity to which the Traders had referred in their witness statements. The Tribunal does not at this stage set out its conclusions on the credibility of each of the Traders. They each denied market abuse, giving evidence that they had an intention to trade all of their Large Orders and did not collaborate to commit an abusive scheme. The Tribunal’s assessment of that evidence is made in the light of all of the evidence.

71. The Tribunal also heard evidence from Mr Fernando Fernandez-Maquieira, a broker in the EGB market, who had provided a witness statement and was cross-examined by Ms Hassell-Hart on behalf of the Authority. Mr Fernandez-Maquieira had worked with traders for 20 years and Mr Urra had been a client of his. He had first met Mr Urra whilst Mr Urra was at Credit Suisse, and Mr Urra remained a client during his time at MHI between 2012 and 2019. Mr Fernandez-Maquieira’s role was to help the traders find buyers and sellers for their orders. He gave evidence in relation to order size (both in the EGB futures market generally and sizes transacted by MHI), the splitting of orders and his opinion on the plausibility of Mr Urra’s Trading Strategy. The Tribunal accepts that Mr Fernandez-Maquieira gave his evidence honestly and sought to assist the Tribunal. However, the Tribunal has not relied on his evidence when making findings of fact as his evidence was given by reference to the long period of time during which he worked with Mr Urra and he was not able to be specific about order sizes by reference to particular periods of time as he no longer has access to the data relating to his transactions with MHI during the Relevant Period.

72. Mr Simon Virciglio, who is a former broker in the EGB market, had provided a witness statement in the context of Mr Urra’s reference and was willing to attend and be cross-examined but the Authority, Mr Lopez and Mr Sheth agreed he did not need to attend for cross-examination. Mr Virciglio’s evidence was essentially a character reference for Mr Urra, referring to him being held in high regard, straightforward, fair, meticulous and focused on his trading strategies. He also described both Mr Lopez and Mr Sheth as straightforward and honest. It was common ground between the parties that none of the Traders had previously been subject to any compliance investigation or disciplinary proceedings and, with no disrespect intended to Mr Virciglio, the Tribunal places no weight on his evidence.

73. The Tribunal also had the benefit of expert evidence from:

(1) Mr Stephen Creaturo, who is a Financial Markets Advisor at Valere Capital Partners LLP, and had been instructed as an expert by the Authority; and

(2) Mr Andrew Kasapis, who is a Senior Director at Kroll Advisory Ltd, and had been jointly instructed by the Traders as an expert.

74. Mr Creaturo and Mr Kasapis both produced expert reports for the Tribunal and the Tribunal was also taken to the expert reports which Mr Kasapis had prepared before the RDC. Mr Creaturo and Mr Kasapis both addressed the matters identified in the agreed list of issues, namely:

(2) Is the trading activity (both in the individual trader and the multi-trader Instances) identified in the Instance Pool explained by/consistent with an intention to pursue the alleged trading strategies identified by each Trader?

(3) Whether the large orders outside the Instance Pool are explained by/consistent with an intention to pursue the alleged Trading Strategies.

(4) Are the Specified Instances representative of the Instance Pool as a whole?

75. The evidence in the hearing bundles included:

(1) trading activity in relation to the 233 Instances in the Instance Pool as illustrated in Appendix 2 (albeit that the narrative was only provided for the Specified Instances);

(2) daily price graph (London time) for Futures on each trading day in the Relevant Period (which had been exhibited by Mr Lopez) - the price movements for each day were shown on a single page, with 15 minute intervals marked;

(3) list of trades in BTPs entered into by the Desk between 1 June and 31 July 2016;

(4) Electronic RFQs received by the Desk in BTPs between 1 June and 31 July 2016;

(5) a list of the 93 RFQs that came into the Desk during the Relevant Period which would have required hedging with a Futures order of 200 lots or more (which had been exhibited by Mr Lopez);

(6) floor plans for the relevant part of MHI’s offices during the Relevant Period;

(7) records of training undertaken by the Traders, with copies of slides from some of that training;

(8) the MHI Compliance Report (as defined below);

(9) transcripts of the Authority’s interviews with other employees of MHI namely Christian Heiberg (Head of Fixed Income Trading), Dinesh Joshi (Head of Compliance), Anthony Algeo (Executive Director, Compliance), Graham Halliday (COO Front Office), Mehdi Barouti and James Hill (the other traders on the Desk); and

(10) materials produced by the Authority, including summaries of data obtained by the Authority from the Exchange in relation to orders placed by other market participants (the “SMARTS data”).

Pace of Authority’s investigation and particularisation of its case

76. The Traders drew attention to the length of time since the Relevant Period and submitted that the delays by the Authority in its investigation and in particularising its case have resulted in unfairness and prejudice.

77. On 26 July 2016, the Exchange sent a letter to Mizuho Securities USA Inc (“MSUSA”) (which was the member firm on the Exchange) querying the trading rationale for two identified episodes of trading which had taken place on 29 June 2016 (the “Eurex Letter”). MSUSA forwarded this letter to MHI on 28 July 2016. MHI then interviewed Mr Urra (on 29 July and 5 August 2016) and Mr Sheth (on 3 and 9 August 2016) before responding to Eurex on 22 August 2016.

78. MHI’s Compliance team continued its own review of the trading activity (as part of which it interviewed Mr Lopez on 29 September 2016) and produced a report on “A Review of European Government Bond Desk Dealing Practice on the EUREX Exchange” in October 2016 (the “MHI Compliance Report”). That report was sent to the Traders on 13 October 2016 and they were informed by MHI that they would be the subject of a disciplinary investigation in relation to orders for Futures placed on Eurex. MHI sent this report to the Authority (which had already been informed of the Eurex Letter).

79. The matter was referred to MHI’s Head of Human Resources (“HR”) for a disciplinary investigation. MHI held further meetings with each Trader - Mr Urra and Mr Lopez were each interviewed on 18 October 2016, Mr Sheth was interviewed on 14 October 2016, and there were disciplinary meetings with each Trader on 2 November 2016.

80. On 10 November 2016, MHI’s CFO wrote to each of the Traders to inform them of the outcome of the disciplinary process. MHI took no disciplinary action against Mr Lopez. MHI issued a first warning to Mr Sheth in respect of his “poor practice” in placing multiple orders instead of amending existing orders and a final warning to Mr Urra in respect of his management of Mr Sheth. There were no findings of market abuse against any of the Traders.

81. Mr George submitted that the Authority’s investigation then progressed at an exceptionally slow pace:

(1) The Authority had been sent the MHI Compliance Report in October 2016 but it did not appoint investigators until 16 March 2017.

(2) The Authority then requested the Eurex trading data on 25 April 2017, with the assistance of the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority of Germany (“BaFin”), which was received on 19 September 2017.

(3) The Authority didn’t interview the Traders until the first half of 2018 - Mr Lopez on 18 and 19 January 2018, Mr Sheth on 15 March 2018 and Mr Urra on 16 April 2018.

(4) It was not until April 2019 that the Authority indicated that it intended to engage an independent expert. They instructed their first expert, Mr Santacana, in June 2019, whose expert report was then produced on 30 September 2020.

(5) The Authority served Annotated Warning Notices on the Traders in October 2020.

(6) The Traders each provided a response in December 2020, but the Enforcement and Market Oversight Division (“EMO”) didn’t serve its Enforcement Submissions Document on each of the Traders until 19 May 2021.

(7) The Warning Notices were issued to each Trader on 16 July 2021.

(8) The RDC hearings took place in March 2022.

(9) The Authority issued its Decision Notices for each of the Traders on 31 October 2022.

82. The Traders referred these matters to the Tribunal on 28 November 2022, and the references were heard from 27 January to 14 February 2025. Mr George referred to the decision of the Tribunal in Seiler, Whitestone and Raitzin v Financial Conduct Authority [2023] UKUT 133 (TCC) (“Seiler UT”) where the Tribunal had (at [59]) described the delays as unsatisfactory and recorded that in that case the lapse of time between the events in question and the hearing of the references was longer than any other comparable proceedings in the experience of that Tribunal, noting that such record has now been surpassed in these proceedings.

83. Alongside their submissions in relation to what they described as the slow progress of the Authority towards the issue of Decision Notices, the Traders drew the Tribunal’s attention to how the Authority’s case has been particularised and submitted that the Authority’s failure to particularise the Instance Pool at an early stage has also hindered the Traders’ ability to recollect the specific trading activity on which the Authority now relies:

(1) The Eurex Letter asked about two Instances, which are now referred to as F174 and F176.

(2) The Traders were interviewed by the Authority in 2018, but at that time the Authority put a limited number of Instances to them - they had been provided with bundles containing trading data for approximately 11 Instances each, which were the subject of the interviews.

(3) The Traders submitted that the first time the Traders were told in any detail of the allegations against them was when the Authority issued the Annotated Warning Notices in October 2020.

(4) The Authority’s first statements of case were served in February 2023, which annexed a table listing the 233 Instances, of which only a small number were particularised.

(5) On 2 February 2024 the Authority revised the number of Instances relied upon against each Trader and provided “further particulars” for each alleged Instance of market abuse.

(6) Following a contested application which was determined at a case management hearing on 20 June 2024, the Tribunal ordered the Authority to: (1) identify ten individual instances per Trader and ten Multi Trader Instances (these being the Specified Instances); (2) provide narratives detailing each Specified Instance; and (3) limit cross-examination of the Traders to these Specified Instances and any further Instances or trading activity outside of the Instance Pool identified by the Traders.

(7) The Authority identified the Specified Instances on 4 July 2024 and filed narratives on 18 July 2024.

84. Mr Shivji submitted that this is a particularly technical and complex matter and the Authority had sought to conduct a thorough and fair investigation. It was inevitable that it was always going to take some time for the Authority to analyse the data - the Authority received approximately 16.5m lines of data from Eurex alone. The Authority submitted that the relevance of the delay must be set in its proper context, saying the Traders’ central complaint was understood to be that the passage of time meant that they have difficulty recalling what happened and why; this was described as “uncontroversial” by the Authority. On the facts, Mr Shivji submitted that even if the Authority had been able to move much more quickly - which was not accepted - this would not have improved the evidence before the Tribunal. The Traders acknowledged that their recollection of the specific trades was poor even in September and October 2016; and on any view the hearing before the Tribunal would be taking place years after the end of the Relevant Period.

85. The hearing took place over a period of three weeks. Having heard the submissions of the parties, the evidence of the Traders and the two experts, during the course of which the Tribunal was taken to a large amount of data in relation to the trading activity, the Electronic RFQs received by the desk and the cash bond transactions which were executed - which was itself only a small portion of that which was in the hearing bundle - the Tribunal accepts that a thorough investigation would take time. However, whilst we have not heard from any witnesses from the Authority who could have explained the progress of the various steps in the investigation (an approach which was itself criticised by the Traders in their opening submissions), the Tribunal considers that there were some delays that are unexplained and are not a consequence of the complexity of the underlying activity. Those which potentially had the most significance are those which occurred in the early stages, in particular:

(1) the delay between the Authority receiving the MHI Compliance Report in October 2016 (having already been informed of the receipt of the Eurex Letter at the end of July or beginning of August 2016) and appointing investigators in March 2017, which in turn delayed the request for Eurex trading data and contributed to the Traders only being interviewed by the Authority in 2018; and

(2) the delay in deciding to engage an independent expert and the period of time which followed until production of the first expert report in September 2020, ie more than four years after the end of the Relevant Period.

86. Progress thereafter was not swift. But it is these delays which meant that it was more than four years after the Relevant Period that the Authority served the Annotated Warning Notices on the Traders, and whilst the Authority has subsequently amended the number of Instances on which it relies against each Trader, it was not until this time that the Traders would have understood the breadth of the case being made against them and, importantly, that the Authority was not only challenging whether the Traders were pursuing a legitimate trading strategy but also alleging that they had each (individually and together) engaged in market abuse on a large number of occasions throughout a period of two months.

Lack of information that would have been available to the Traders during the Relevant Period

87. The Traders have each emphasised in their witness statements and during cross-examination that they no longer have access to the full range of information that would have been available to them during the Relevant Period and which would have formed part of the rationale for their trading activity and that this, as well as the delays by the Authority in disclosing the information which is now available, has hindered their ability to recall matters.

88. The Traders have referred to having requested information from the Authority at various times during the Authority’s investigation, eg Mr Urra asked for specified categories of information on 4 April 2018. Similar requests have been made by Mr Lopez and Mr Sheth. Some, but not all, information that has been requested has been provided by the Authority. The Traders have not made an application to the Tribunal for disclosure by the Authority.

89. The Authority’s disclosure obligations are set out in the Upper Tribunal Rules. Paragraph 4(3) of Schedule 3 requires that the Authority provide a list of any documents on which the Authority relies in support of the referred action and any further material which in the opinion of the Authority might undermine the decision to take that action; and the secondary disclosure obligation in paragraph 6(1) then requires that the Authority disclose any further material which might reasonably be expected to assist the applicant’s case as disclosed by the applicant’s reply.

90. In late 2020, the Authority provided to the Traders:

(1) Electronic RFQs received by the Desk for BTPs in the Relevant Period;

(2) a record of all orders for Futures placed by the Traders during the Relevant Period - this includes orders which filled or partially filled as well as those which were cancelled, and identifies the Trader who placed the order, timing, direction (ie buy/sell), size and amendments made to the order; and

(3) records of executed cash trades in BTPs entered into by the Desk in the Relevant Period.

91. On 1 August 2023, the Authority provided to the Traders a copy of the full Eurex dataset it had received from BaFin. This dataset listed all orders, including enters, fills, partial fills, amendments and cancellations, in Futures by all market participants during the Relevant Period.

(1) records of RFQs received over the phone (“Voice RFQs”);

(2) records of RFQs sent electronically through Bloomberg message/chat functionality (“Bloomberg/Chat RFQs”);

(3) records of the information broadcast to the Traders on the squawk box;

(4) records of the cash bond market, including interdealer market order books from Euro MTS (multiproduct), MTS Spain (Spanish bonds), Brokertec (multiproduct) and SENAF (Spanish bonds);

(5) content of the Traders’ books of inventory at MHI; and

(6) records of communications, including telephone calls, emails and messages, including with the sales team.

93. In their written closing submissions the Traders adopted different positions from each other in relation to the disclosure which had been made by the Authority:

(1) Mr George set out a chronology of Mr Urra’s requests for information, summarising responses and what had been received, and, when outlining the “considerable amount” of information that is not before the Tribunal, said it is “not clear” whether any of this information is available to the Authority and has not been shared.

(2) Mr Jaffey submitted that the Authority has never produced a range of relevant secondary disclosure that is “understood to be in its possession” including evidence of voice orders placed with the Desk, the squawk box data and the relevant part of MTS (most relevantly the Eurobond book), which would have provided information on a number of issues, including the cash position at any given period of time.

(3) Mr Bailin submitted that there is now a question as to whether the Authority has properly discharged its obligations of disclosure, referring to the Enforcement Submissions Document which had been submitted to the RDC which confirmed that various communications were provided by MHI and reviewed by the EMO, namely telephone calls on fixed office lines, audio recordings from a dealer board system, emails and Bloomberg messages. EMO’s review of these had been aimed at finding any communications that explained the rationale behind the placing of the Large Orders. None of this information has been disclosed. Mr Bailin submitted that it seems clear that the communications review has not been undertaken in respect of all of the Instance Pool, or all of the Specified Instances, and did not look at the rationale for the Small Orders. The current position, he submitted, was that the Authority “simply do not know with regard to the communications review whether there is material which meets the statutory test for disclosure”.