Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) >> L-L-O Contracting Ltd & Ors v Revenue and Customs (Stamp Duty Land Tax - failure to claim multiple dwellings relief - claims for relief for overpaid tax - paras 34 and 34A Schedule 10 Finance Act 2003 - Case A - whether HMRC liable to give effect to the claims) [2025] UKUT 127 (TCC) (15 April 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/TCC/2025/127.html

Cite as: [2025] UKUT 127 (TCC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

UT Neutral citation number: [2025] UKUT 127 (TCC)

UT (Tax & Chancery) Case Number: UT/2024/000013

UPPER TRIBUNAL

TAX AND CHANCERY CHAMBER

Hearing venue: Rolls Building

Fetter Lane

London

EC4A 1NL

Heard on:12 February 2025

Judgment date: 14 April 2025

Stamp Duty Land Tax - failure to claim multiple dwellings relief - claims for relief for overpaid tax - paras 34 and 34A Schedule 10 Finance Act 2003 - Case A - whether HMRC liable to give effect to the claims

Before

JUDGE JONATHAN CANNAN

JUDGE ANDREW SCOTT

Between

L-L-O CONTRACTING LIMITED

AND OTHERS

Appellants

and

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HIS MAJESTY’S

REVENUE AND CUSTOMS

Respondents

Representation:

For the Appellant: Patrick Cannon, Counsel instructed by Goldstone Tax Limited

For the Respondent: Nicholas Macklam, Counsel instructed by the General Counsel and Solicitor for His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

DECISION

Introduction

1. These appeals concern the appellants’ entitlement to multiple dwellings relief for the purposes of stamp duty land tax (“SDLT”). More particularly, the appellants’ entitlement to claim repayment of overpayments of SDLT resulting from failures to claim multiple dwellings relief. In a decision released on 13 October 2023, the First-tier Tribunal (“the FTT”) struck out the appellants’ appeals against decisions of HMRC to refuse repayment (“the Decision”).

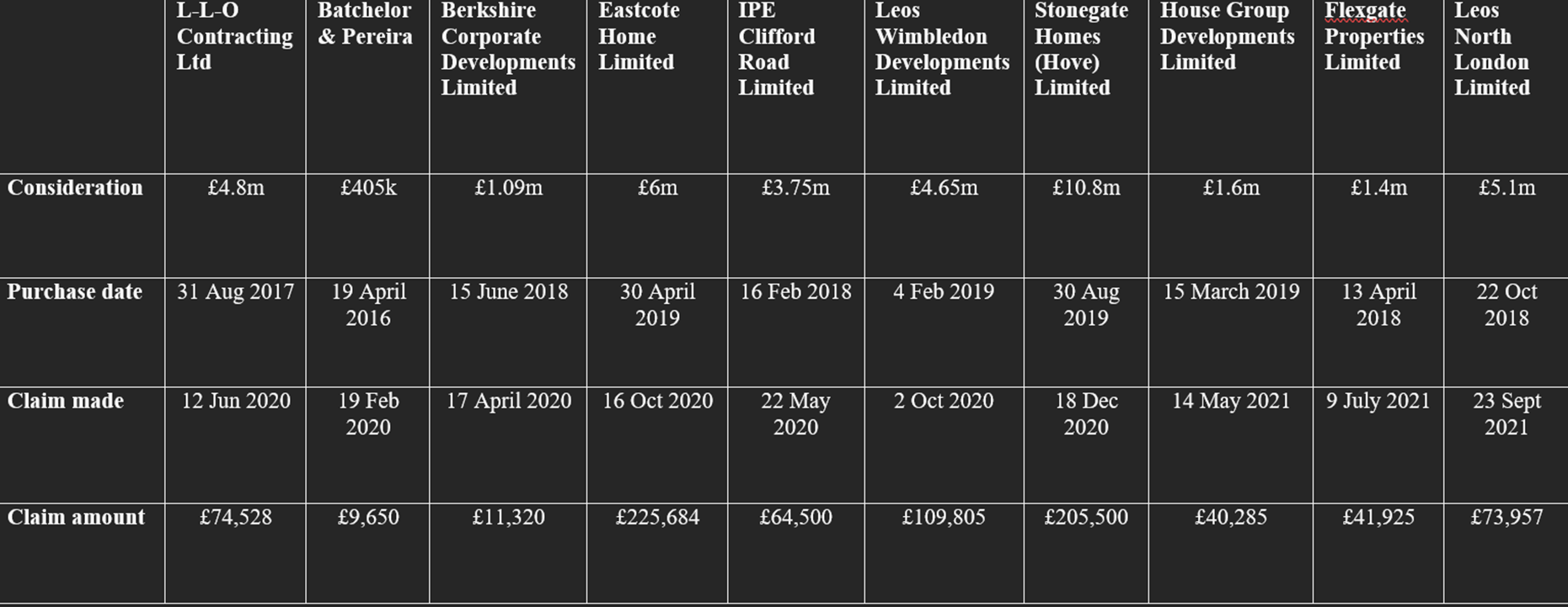

2. We have identified each of the appellants in the Annex to this decision together with the amount each appellant is claiming from HMRC. The claims relate to property purchases between April 2016 and August 2019.

3. Section 58D Finance Act 2003 (“FA 2003”) provides for relief in the case of a transfer which involves multiple dwellings and also provides how that relief is to be claimed:

58D Transfers involving multiple dwellings

(1) Schedule 6B provides for relief in the case of transfers involving multiple dwellings.

(2) Any relief under that Schedule must be claimed in a land transaction return or an amendment of such a return.

4. A land transaction return is due 14 days after the effective date of the transaction, which is usually the date of completion. This is the “filing date”. The time limit for amending a return is 12 months from the filing date. The form of land transaction return requires purchasers to answer a question as to whether they are claiming any relief and if so to identify that relief by reference to a code. The appellants did not make claims for relief in their land transaction returns or in any amendment of those returns. Instead, they made claims pursuant to paragraph 34 Schedule 10 FA 2003 which provides as follows:

Claim for relief for overpaid tax etc

34(1) This paragraph applies where —

(a) a person has paid an amount by way of tax but believes that the tax was not due, or

(b) a person has been assessed as liable to pay an amount by way of tax, or there has been a determination to that effect, but the person believes that the tax is not due.

(2) The person may make a claim to the Commissioners for His Majesty's Revenue and Customs for repayment or discharge of the amount.

(3) Paragraph 34A makes provision about cases in which the Commissioners for His Majesty's Revenue and Customs are not liable to give effect to a claim under this paragraph.

(4) The following make further provision about making and giving effect to claims under this paragraph —

(a) paragraphs 34B to 34D, and

(b) Schedule 11A.

(5) …

(6) The Commissioners for His Majesty's Revenue and Customs are not liable to give relief in respect of a case described in sub-paragraph (1)(a) or (b) except as provided —

(a) by this Schedule and Schedule 11A (following a claim under this paragraph), or

(b) by or under another provision of this Part of this Act.

5. Paragraph 34B(1) provides that the time limit for making a claim under paragraph 34 is 4 years from the effective date of the transaction.

6. Paragraph 34A makes provision for situations in which HMRC are not liable to give effect to a claim. Those situations are described as Cases A to G. For present purposes Cases A to C are relevant:

34A(1) The Commissioners for His Majesty's Revenue and Customs are not liable to give effect to a claim under paragraph 34 if or to the extent that the claim falls within a case described in this paragraph.

(2) Case A is where the amount paid, or liable to be paid, is excessive by reason of —

(a) a mistake in a claim or election, or

(b) a mistake consisting of making or giving, or failing to make or give, a claim or election.

(3) Case B is where the claimant is or will be able to seek relief by taking other steps under this Part of this Act.

(4) Case C is where the claimant —

(a) could have sought relief by taking such steps within a period that has now expired, and

(b) knew, or ought reasonably to have known, before the end of that period that such relief was available.

7. Schedule 11A contains procedural provisions for making and dealing with claims, other than claims which are required to be made in a return or by way of amendment to a return. This includes provisions for the form of claims, enquiries into claims and appeals against closure notices.

8. The FTT was not concerned with the underlying entitlement of the appellants to multiple dwellings relief. It was concerned with various issues which had been directed to be heard as preliminary issues. The preliminary issues were addressed on the assumption that the appellants were otherwise entitled to multiple dwellings relief but had failed to claim the relief in a land transaction return or in an amendment to a land transaction return. It was further assumed that the appellants did not know and could not reasonably have known prior to expiry of the time limit to amend their land transaction returns that multiple dwellings relief was available.

9. We can summarise the preliminary issues before the FTT as follows:

Issue 1(a) - Whether a claim for overpayment relief can validly be made pursuant to paragraph 34 Schedule 10 in respect of multiple dwellings relief notwithstanding the provisions of section 58D(2).

Issue 1(b) - If so, where a claim has not been made in a return or an amendment to a return, whether it can be said that there has been an overpayment of tax for the purposes of paragraph 34 Schedule 10.

Issue 2 - If so, whether Case A excludes a claim for such relief under paragraph 34 if the taxpayer had no actual awareness or knowledge of the potential availability of multiple dwellings relief at any time up to the expiry of the time limit for amending the return.

10. In the event, it was common ground before the FTT that the answer to Issue 1(a) was “yes”. We take that to mean that a claim for overpayment relief arising out of a failure to claim multiple dwellings relief would in principle fall within paragraph 34, subject to paragraph 34A. The FTT went on to hold in relation to Issue 1(b) that there was an overpayment of tax where a valid claim to multiple dwellings relief was not made in a return or an amendment to a return. There is no challenge to that finding by HMRC. The issue on this appeal concerns the FTT’s finding on Issue 2.

11. The FTT held in favour of HMRC on Issue 2. It found that Case A excluded relief for overpayment of tax because there had been a mistake consisting of failing to make a claim. The taxpayer’s awareness or knowledge of the potential availability of multiple dwellings relief was irrelevant. The FTT rejected the appellants’ argument that a taxpayer who fails to make a claim in a return or an amendment to a return as a result of a lack of awareness does not make a mistake.

12. In light of its findings on the preliminary issues, the FTT held that HMRC were not liable to give effect to the appellants’ claims for repayment. It therefore struck out the appeals on the ground that they had no reasonable prospect of success.

13. The Upper Tribunal granted permission to appeal on various grounds. Essentially, the appellants say that the FTT wrongly construed the restriction in Case A. It is argued that a taxpayer does not make a mistake in failing to make a claim for multiple dwellings relief where the taxpayer did not know that such a claim could be made.

The FTT Decision

14. Issue 2 turned on the meaning of the word “mistake” in paragraph 34A(2)(b). The FTT’s reasoning for finding that the appellants had made a mistake consisting of failing to make a claim for multiple dwellings relief, with references to relevant paragraphs in the Decision, may be summarised as follows:

(1) As a matter of ordinary language, supported by dictionary definitions, a person can make a mistake by omitting to do something. That is the case whether or not the person was aware that they could do the thing in question. In other words, a mistake can be made as a result of oversight or ignorance, as well as for other reasons (see [27] - [29]).

(2) A more limited meaning of the word “mistake” in paragraph 34A(2)(b) would undermine the statutory requirement in section 58D(2) that a claim for relief must be made in a return or in an amended return. In particular, if a taxpayer who was unaware of an entitlement to claim multiple dwellings relief did not make a mistake in failing to make a claim, that would reward ignorance of the law because it would give a much longer time limit to make a claim (see [30(1)]).

(3) Case C concerns reliefs which do not require a claim or election. It excludes claims under paragraph 34 if the taxpayer could have sought relief within a relevant time limit and knew or should have known before the time limit expired that the relief was available. If Parliament had intended that Case A should not exclude claims by taxpayers who were not aware that a claim could be made then it would have included a similar exception (see [30(2)]).

(4) The FTT rejected a submission on behalf of the appellants that if HMRC were correct, the word “mistake” in paragraph 34A(2)(b) would be superfluous and perform no function (see [31] and [32]).

(5) The FTT rejected a submission that HMRC’s interpretation of paragraph 34A(2)(b) would leave little scope for overpayment relief to operate (see [33]).

(6) The Explanatory Notes to what became Finance (No 3) Act 2010 which introduced amendments to overpayment relief in paragraphs 34 and 34A supported HMRC’s interpretation (see [34] - [38]).

(7) Whilst Issue 2 had not been directly considered in any authority, existing case law supported HMRC’s interpretation (see [39] - [45]).

15. Mr Cannon, who appeared for the appellants, took issue with each aspect of the FTT’s reasoning.

Discussion

16. The approach we must take in construing paragraphs 34 and 34A Schedule 10 is well established. We must give effect to Parliament’s purpose. That purpose is to be found primarily in the words of the provisions themselves which must be read in the context of FA 2003 as a whole. External aids to construction including Explanatory Notes may be relevant but play a secondary role.

17. The relevant interpretative principles were described by the Supreme Court in R (otao PACCAR Inc and others) v Competition Appeal Tribunal and others [2023] UKSC 28 as follows:

40. The basic task for the court in interpreting a statutory provision is clear. As Lord Nicholls put it in Spath Holme [2001] 2 AC 349, 396, “Statutory interpretation is an exercise which requires the court to identify the meaning borne by the words in question in the particular context.”

41 As was pointed out by this court in Rossendale Borough Council v Hurstwood Properties (A) Ltd [2022] AC 690, para 10 (Lord Briggs and Lord Leggatt JJSC), there are numerous authoritative statements in modern case law which emphasise the central importance in interpreting any legislation of identifying its purpose. The examples given there are R (Quintavalle) v Secretary of State for Health [2003] 2 AC 687 and Bloomsbury International Ltd v Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [2011] 1 WLR 1546. In the first, Lord Bingham of Cornhill said (para 8):

“Every statute other than a pure consolidating statute is, after all, enacted to make some change, or address some problem, or remove some blemish, or effect some improvement in the national life. The court’s task, within the permissible bounds of interpretation, is to give effect to Parliament’s purpose. So the controversial provisions should be read in the context of the statute as a whole, and the statute as a whole should be read in the historical context of the situation which led to its enactment.”

In the second, Lord Mance JSC said (para 10):

“In matters of statutory construction, the statutory purpose and the general scheme by which it is to be put into effect are of central importance . . . In this area as in the area of contractual construction, the notion of words having a natural meaning is not always very helpful (Charter Reinsurance Co Ltd v Fagan [1997] AC 313, 391C, per Lord Hoffmann), and certainly not as a starting point, before identifying the legislative purpose and scheme.”

The purpose and scheme of an Act of Parliament provide the basic frame of orientation for the use of the language employed in it.

42 It is legitimate to refer to Explanatory Notes which accompanied a Bill in its passage through Parliament and which, under current practice, are reproduced for ease of reference when the Act is promulgated; but external aids to interpretation such as these play a secondary role, as it is the words of the provision itself read in the context of the section as a whole and in the wider context of a group of sections of which it forms part and of the statute as a whole which are the primary means by which Parliament’s meaning is to be ascertained: R (Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2023] AC 255, paras 29—30 (Lord Hodge DPSC). Reference to the Explanatory Notes may inform the assessment of the overall purpose of the legislation and may also provide assistance to resolve any specific ambiguity in the words used in a provision in that legislation. Whether and to what extent they do so very much depends on the circumstances and the nature of the issue of interpretation which has arisen.

18. The purpose of paragraph 34 is clearly to make provision for overpayment relief where a taxpayer has overpaid tax that was not due, but subject to certain restrictions in paragraph 34A. We do not accept Mr Cannon’s submission that the FTT failed to give effect to that purpose by unfairly characterising taxpayers who were unaware that they could make a claim as being rewarded for their ignorance with an extended time limit. We might not have described such taxpayers as being rewarded for their ignorance, but that was simply a shorthand for taxpayers being placed in a better position where they lacked knowledge.

19. The FTT considered the dictionary meaning of the word mistake at [27] - [29] and then considered the statutory context at [30] - [33]. It stated at [30(1)] as follows:

(1) If the word “mistake” had the limited meaning contended for by Mr Cannon, this would undermine the statutory requirement clearly set out in s 54D(2) that the claim must be made in (or by amendment to) the SDLT return. It would also reward ignorance of the law by allowing a much longer time limit: para 34B(2) allows four years for an overpayment claim compared to the one year allowed by para 6(3) for amending an SDLT return.

20. The FTT identified that section 54D(2) required a claim to be made in a land transaction return or by amendment to such a return. It had in mind that there was a time limit of 12 months from the filing date to amend a land transaction return. Thus, there is a time limit of 12 months from the filing date for the taxpayer to make a claim for multiple dwellings relief. If the appellants’ arguments were right, a taxpayer with no knowledge of the existence of multiple dwellings relief would have four years to make a claim for overpayment relief under paragraph 34, whereas a taxpayer who was aware of the relief but who mistakenly failed to make a claim would not be able to claim overpayment relief.

21. In our view, the FTT was right to characterise this as placing taxpayers without knowledge of the possibility of a claim for relief in a better position than taxpayers who were aware of the possibility but mistakenly failed to make a claim. We do not consider that the FTT’s construction of the word mistake is inconsistent with the purpose of the provisions, which is to give relief for overpayments but subject to restrictions. Parliament provided a shorter time limit in relation to claims for multiple dwelling relief. There is no indication that it intended to provide a longer time limit where a taxpayer had no knowledge of the possibility of a claim once the time to amend the return had expired. Indeed, on the appellants’ case a taxpayer could first become aware of the possibility of a claim for multiple dwellings relief 13 months after the filing date, but would then have some 3 years to make a claim under paragraph 34. We do not consider that can have been the intention of Parliament in Case A when read in context.

22. The Court of Appeal in Candy v HM Revenue & Customs [2022] EWCA Civ 1447 recognised that the time limits for claiming SDLT reliefs are hard-edged and that failure to claim relief in time can result in a relief not being available:

50. …It is of the essence of a self-assessment system that tax effects can be undone by administrative failure and merely meeting the substantive conditions for the grant of a relief is rarely enough to secure that a taxpayer receives the relief in question. Where the relief requires a claim, and the claim is not made in accordance with any procedural requirements, the taxpayer will not be given the relief.

51 Moreover, hard-edged time limits are a common feature of the self-assessment scheme. Where they govern the availability of a relief, they have the inevitable potential to cause hardship.

23. It is not necessary to consider the facts of Candy, which did not concern multiple dwellings relief. However, the Court of Appeal also noted at [47] the desirability of certainty and finality in relation to the self-assessment system for SDLT, subject to the possibility of a claim under Part 6 Schedule 10 which includes overpayment relief pursuant to paragraph 34:

47. …There are strict time limits for delivering returns: at the material time returns had to be submitted 30 days after the effective date of the transaction (that period is now 14 days). Returns must comply with the requirements of Schedule 10 FA 2003, including the time limits imposed for amending returns in paragraph 6(3), and those imposed on HMRC for opening an enquiry in paragraph 12. As Mr Afzal emphasised, the self-assessment system imposes hard-edged deadlines, both on taxpayers and HMRC, for the sound administration of the tax system and to achieve certainty and finality. If HMRC make no enquiry and a taxpayer has not amended his or her return once the time limits have expired, the self-assessment return becomes final. So, if HMRC fail to open an enquiry in time, the correct amount of tax will not be recoverable by HMRC in respect of an insufficient self-assessment (unless the case falls within the exceptions in Part 5 Schedule 10 FA 2003, which has its own time limits). Likewise, if a taxpayer has mistakenly overpaid tax or been subject to an excessive assessment but made no in-time amendment, the tax cannot be reclaimed unless Part 6 of Schedule 10 FA 2003 provides a remedy.

24. We agree with the FTT that the hard-edged time limits and procedural requirements described in Candy would be significantly undermined if taxpayers could fail to claim multiple dwellings relief within the 12-month time limit to amend a return, and then claim overpayment relief with the benefit of a 4-year time limit.

25. It is also worth noting that taxpayers have an option as to whether to make a claim for multiple dwellings relief. As the Upper Tribunal observed in HM Revenue & Customs v Ridgway [2024] UKUT 36 (TCC) at [105], it may not always be in the best interests of a taxpayer to claim the relief. It is therefore incumbent on taxpayers to make a claim in accordance with the specific procedural requirements and within the specific time limits. The purpose and rationale behind Case A is clear. It prevents the time limits and procedural requirements in relation to claims being undermined and it promotes certainty and finality in the administration of SDLT. Where a mistake consists of a failure to make a claim for whatever reason, relief is not available.

26. Mr Cannon submitted that the appellants’ construction of Case A would limit claims by taxpayers who were aware they could make a claim but who through some mistake failed to make a claim. However, there was no reason for it to limit claims by taxpayers who were unaware they could make a claim. He submitted that it is reasonable to regard Parliament as having intended to make such a distinction. Such taxpayers would have 4 years to make a claim for overpayment relief. We do not accept that submission which finds no support in the language of paragraph 34A(2)(b). It amounts to re-writing rather than construing the legislation.

27. Mr Macklam invited us to take into account the historical context of paragraph 34A. Paragraphs 34 and 34A were introduced into SDLT with effect from April 2011. The previous regime, known as “error or mistake relief” was in paragraph 34 which as originally enacted provided as follows:

34 Relief in case of mistake in return

(1) A person who believes he has paid tax under an assessment that was excessive by reason of some mistake in a land transaction return may make a claim to the Inland Revenue for relief against any excessive charge.

(2) The claim must be made not more than six years after the effective date of the transaction.

…

(4) No relief shall be given under this paragraph —

(a) in respect of a mistake as to the basis on which the liability of the claimant ought to have been computed when the return was in fact made on the basis or in accordance with the practice generally prevailing at the time when it was made, or

(b) in respect of a mistake in a claim or election included in the return.

28. It can be seen that the present form of overpayment relief extended the restrictions on relief by reference to Cases A to G. In particular, Case A restricted relief not only to a mistake in a claim included in a return but also to a mistake consisting of failing to make a claim. Cases B and C restricted overpayment relief where the taxpayer could obtain or could have obtained relief by taking other steps. Similar amendments were made in 2009 to the provisions permitting recovery of overpaid direct taxes in section 33 and Schedule 1AB Taxes Management Act 1970 and recovery of overpaid corporation tax in paragraphs 51 and 51A Schedule 18 Finance Act 1998. It is not necessary for us to describe those provisions or amendments in detail.

29. In our view the amendments provide no basis on which to distinguish a failure to make a claim where the taxpayer was aware of the possibility of relief from a failure to make a claim where the taxpayer was unaware of the possibility of relief until after expiry of the time limit to amend the land transaction return. Both scenarios involve a mistake consisting of failing to make a claim and simply describe different types of mistakes. Use of the word “mistake” by Parliament does not exclude the latter scenario from the statutory restriction.

30. In short, the FTT did not fail to give sufficient weight to the purpose of paragraph 34. The purpose of paragraph 34 was to provide for overpayment relief, but not in the circumstances of Case A.

31. Nor do we consider that the FTT misinterpreted the dictionary definitions of the word “mistake”. It dealt with dictionary definitions at [27] - [29]:

27. The Cambridge Dictionary defines “mistake” as “an action, decision, or judgment that produces an unwanted or unintentional result”; it defines “error of omission” as “a mistake that consists of not doing something you should have done, or not including something such as an amount or fact that should be included”.

28. The extract from the Oxford English Dictionary included in the Bundle defines a mistake as “a misconception about the meaning of something; a thing incorrectly done or thought; an error of judgement”. The full entry continues by adding the following further definitions: “misapprehension, misunderstanding; error, misjudgement” and “something chosen through an error of judgement; a badly selected thing, a regrettable choice”.

29. I agree with [HMRC’s advocate] that these definitions do not support Mr Cannon’s submission that, as a matter of ordinary language, a person only makes a “mistake” when he has an “awareness” of something and goes on to make an incorrect decision: the definitions above include an “unwanted…result”, a “thing incorrectly done” and “a badly selected thing”. They therefore refer to the outcome of a person’s decision, and do not import any requirement that he had any sort of prior awareness before making the decision. I therefore find that, as a matter of ordinary language, a person can make a “mistake” by omitting to do something of which he was unaware. In other words, a “mistake” can be made by oversight and/or by ignorance, as well as for other reasons.

32. Mr Cannon submitted that the definitions relied on by the FTT were by reference to positive actions rather than negative failures to act. As such, he characterised the FTT’s analysis as being “irrational in the Edwards v Bairstow [1956] AC 14 sense”.

33. We do not see the relevance of Edwards v Bairstow where the appellants are challenging the meaning given to a word used in a statute, and criticising the construction of that word adopted by the FTT. Statutory construction is a matter of law. If the FTT has adopted the wrong construction then it will have erred in law. It adds nothing to the appellants’ arguments to describe the FTT’s approach as irrational.

34. In any event, we consider the FTT was right to find that the dictionary definitions of the word “mistake” do not support the appellants’ case that a person only makes a mistake where they have an awareness of something and make an incorrect decision. We were not taken to the dictionary entries referred to by the FTT. However, we are satisfied that in ordinary language a person may be described as making a mistake where that person’s act or omission gives rise to an unwanted outcome. It is a “thing incorrectly done”. That is so whether the unwanted outcome was the result of oversight or ignorance. In the present context, where it is said to be a matter of ignorance, the mistake may properly be viewed as being the result of a failure to research or take advice, but it is a mistake nonetheless.

35. We agree with Mr Macklam that it is difficult to conceive of a word more apposite than “mistake” to describe the appellants’ failure to claim multiple dwellings relief, irrespective of what they knew or ought reasonably to have known as to the possibility of making such a claim. There is nothing unnatural, artificial or contrived about describing the failures to make claims for multiple dwellings relief in these cases as mistakes. We do not consider that Parliament would use the word “mistake” to identify a taxpayer who is aware of the relief but fails to claim it through oversight, thereby differentiating a taxpayer who is unaware of the relief and fails to claim it and makes no mistake.

36. In this regard, the FTT compared Parliament’s approach in Case A to the approach in Case C. The FTT concluded at [30(2)]:

(2) The different wording used in Case A and Case C support HMRC’s position because:

(a) Case C concerns reliefs which do not require a claim or election. [HMRC’s advocate] said that there were a number of such reliefs, and identified s 5(1)(ab), (use for a relievable trade); s 67 (reorganisation of Parliamentary constituencies) and s 71 (registered social landlords). Mr Cannon did not dispute any of those examples or the general principle that not all reliefs require a claim or election.

(b) Case C provides that HMRC is not liable to give effect to a claim if the person could have sought relief but (i) is now out of time to do so, and (ii) knew or ought reasonably to have known that the relief was available. In other words, HMRC do have to consider claims made by those who are out of time to benefit from that type of relief, if it was not reasonable for the taxpayer to have known the relief was available.

(c) Had Parliament intended that Case A should likewise exclude persons who could not reasonably have known about a relief for which a claim or election is required (such as MDR) within the statutory time limits, a similar exception would have been included in Case A, but there is no such wording.

37. Mr Cannon submitted that there is no equivalence between Case A and Case C. They are directed at materially different situations. Case A deals with situations where positive action in the form of a claim or election is required. Case C deals with cases where no claim or election is required. It was understandable that Parliament would limit the restriction in Case C to situations where the taxpayer knew or should have known that a relief was available in situations where that relief did not have to be claimed. There is no such limitation in Case A because Parliament used the word “mistake” to exclude from the restriction persons who failed to make a claim as a result of ignorance.

38. Mr Cannon referred to section 60 FA 2003 as an example of a relief which does not require a claim. Section 60 provides for exemption from SDLT where an interest in land is purchased by way of a compulsory purchase facilitating development. If a land transaction return does not calculate the SDLT taking into account the exemption then the purchaser may want to claim overpayment relief. Relief would be excluded by Case B if the purchaser was still in time to lodge an amended return. If the purchaser was out of time to amend the return then Case C might exclude relief but only if the purchaser knew or ought to have known that the purchase was exempt from charge.

39. We do not consider that this distinction between Case A and Case C explains why Parliament would choose to make reference to what the taxpayer knew or ought reasonably to have known in Case C, but choose not to do so in Case A. We agree with the FTT that the difference in wording is significant. When Parliament intended to introduce a carve out in paragraph 34A, it did so in Case C but not in Case A. The FTT was right to treat the existence of an express carve out in Case C as supporting its interpretation of Case A.

40. Mr Cannon submitted that on HMRC’s construction the word “mistake” in section 34A(2)(b) was superfluous. If any failure to make a claim would fall within Case A, regardless of the reason for that failure, there was no reason for Parliament to include within Case A “a mistake consisting of … failing to make … a claim”. The FTT rejected the same submission at [31] and [32] of the Decision:

31. Mr Cannon submitted that HMRC’s argument “leaves no function for the word mistake” and that had Parliament intended Case A to include a failure by a taxpayer to make a claim when he was entirely ignorant of that possibility, the legislation would not have referred to “mistake” at all, but simply said that Case A applied where a person “failed to make” a claim. He said Parliament could have achieved the meaning contended for by HMRC if the references to “mistake” had been omitted, as set out below:

“Case A is where the amount paid, or liable to be paid, is excessive by

reason of —

(a) a mistake in a claim or election, or

(b) a mistake consisting of the making or giving, or failing to make or give, a claim or election.”

32. I disagree. Case A starts from the position that the amount of SDLT is “excessive”. For that to be the position requires not only a “claim” or a failure to make a claim; it also requires that there is something wrong: in ordinary language a “mistake”.

41. It is well established that in statutory interpretation there is a presumption that all words in the statute should be given some meaning or have substantive effect (see Candy at [54]).

42. It does not seem to us that the words struck through by the FTT in the passage above properly reflect Mr Cannon’s submission. As we understand the submission, he does not take issue with the reference to a mistake in paragraph 34A(2)(a). Nor does he specifically take issue with the reference to a mistake in sub-paragraph (b) to the extent that it relates to the making or giving of a claim or election. It is only in the context of the taxpayer failing to make or give a claim or election that he says the word mistake is otiose if the FTT was right as to the meaning of the word. The word is not otiose if it is construed as identifying that only a taxpayer who knew or should have known about the availability of multiple dwellings relief is caught by the restriction. A taxpayer who had no knowledge of the availability of the relief would not make a mistake in failing to claim the relief.

43. In oral submissions, Mr Cannon canvassed the hypothetical example of a taxpayer purchasing a residential property without any knowledge that multiple dwellings relief was available. In the following 12 months he becomes aware that relief would have been available and intends to amend his return. However, at the last minute some circumstance beyond the taxpayer’s control prevents him from lodging the amendment. As we understood Mr Cannon’s reliance on this example, it was to the effect that the taxpayer’s failure to make the claim in an amended return could not be described as a mistake. In those circumstances, Case A should not be construed as restricting a claim to overpayment relief.

44. In the example given, it is clear to us that the failure to make the claim in the amended return was not a mistake. However, the failure to make the claim in the original return was a mistake. It is possible that in some circumstances questions might arise as to the cause of the failure to make the claim and whether it amounted to a mistake. However, that is not the case before us and we express no view on how a claim for overpayment relief might be dealt with in those circumstances. We do acknowledge that it is difficult to envisage circumstances where a failure to make a claim for multiple dwellings relief in the original land transaction return would be anything other than a mistake. However, we are not satisfied that this means that we should try and give the word mistake in paragraph 34(2)(b) some meaning different to its ordinary and natural meaning. Parliament may have considered that for drafting purposes there was no need to distinguish circumstances where there was a mistake in making a claim and circumstances where no claim at all was made, applying the word mistake to both. Alternatively, Parliament left open the possibility that there could be circumstances where the failure to make a claim was something other than a mistake in which case relief would not be restricted.

45. In any event, even if the word “mistake” is otiose in the context of a failure to make a claim, we are not persuaded that this in itself should cause us to construe the provision as excluding from the restriction in Case A those taxpayers who fail to make a claim because they are unaware of the availability of multiple dwellings relief. We agree with Mr Macklam that the FTT was right to reject the Appellants’ submission. The legislation must be construed in its context, without an excessive focus on single words.

46. The FTT addressed the significance of the Explanatory Notes accompanying the amendments to paragraph 34 and the introduction of paragraph 34A at [34] - [38] of the Decision. It referred to the following paragraphs from the Explanatory Notes:

4. New paragraph 34 provides that a person may make a claim for repayment of an amount that they have overpaid by way of SDLT or for discharge of an amount that has been over-assessed as SDLT, subject to restrictions set out in paragraph 34A.

5. New paragraph 34 further provides that the Commissioners for HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) are not liable to give relief in respect of an overpayment or overassessment of SDLT except as required under Part 4 of FA 2003 - the SDLT legislation.

6. New paragraph 34A sets out cases in which the Commissioners are not liable to give relief

• Case A is where the overpayment or over-assessment is attributable to a mistake concerning a claim or election;

• Case B is where it is possible to take other steps under the SDLT legislation to remedy the overpayment or over-assessment;

• Case C is where the claimant could have taken other steps under the SDLT legislation when they first knew, or ought reasonably to have known, of the overpayment or over-assessment;

…

21. Currently, if a person finds that they have overpaid SDLT due to a mistake in a return which has become final, they may make a claim for relief unless the mistake relates to a claim or election or the return was made in accordance with the practice generally prevailing at that time.

…

23. The new rules cover any situation in which a person overpays or is over assessed an amount in respect of SDLT including amounts paid under a contract settlement with HMRC. However, a claim will only be possible where there was no other means of reclaiming the overpayment or reducing the assessment in the SDLT legislation when the person first became aware or ought to have become aware that they could recover the overpayment.

47. The FTT found at [37] and [38] that the Explanatory Notes supported HMRC’s interpretation of paragraph 34A rather than the appellants’ interpretation:

37. [HMRC’s advocate] submitted that the Notes supported HMRC’s view of the meaning and purpose of Case A. Mr Cannon sought to rely on para 23, with its reference to the new rules covering “any situation in which a person overpays or is over assessed an amount in respect of SDLT”.

38. I again agree with [HMRC’s advocate]. It is clear from para 6 of the Notes that Case A covers all overpayment claims where the overpayment “is attributable to a mistake concerning a claim or election”; para 21 reflects this when it says that the overpayment claims can be made “unless the mistake relates to a claim or election”. Para 23 must therefore be read subject to that exception.

48. Mr Cannon submitted that the FTT was wrong to find that the Explanatory Notes supported HMRC’s interpretation. Whilst it does not affect our conclusion on these appeals, we agree with that submission. It is true that the language used in the Explanatory Notes is arguably wider than the language used in Case A. At [6] it refers to an overpayment which is attributable to “a mistake concerning a claim”. Similarly, at [21] it refers to a claim being possible “unless the mistake relates to a claim”. In our view these references are simply a shorthand to describe the statutory language in paragraph 34A(2)(a) and (b). They shed no light on the meaning of the provisions, in particular on what is meant by a mistake in paragraph 34A(2)(b). As such the references cannot be said to support HMRC’s case.

49. Mr Cannon did not seek to persuade us that the Explanatory Notes supported the appellants’ interpretation of paragraph 34A(2)(b).

50. Finally, we should briefly mention existing case law which the FTT considered at [39] - [45] of the Decision. The Upper Tribunal in Candy v HM Revenue & Customs [2021] UKUT 170 (TCC) did not consider in detail the possibility of the taxpayer in that case claiming overpayment relief, although it did make reference to paragraphs 34 and 34A:

112 It is of the very essence of a self-assessment system that tax effects can be undone by administrative failure. Mr Thomas correctly pointed out that, in other contexts where SDLT reliefs were available such as section 58D or 62 of FA 2003, the relevant facts would be known at the effective date of the transaction (and so a return could include a claim for relief). That may be so; but it does not follow that merely meeting the conditions for the relief is enough to secure that the taxpayer actually gets the relief. The relief requires a claim; and if the claim is not made in the return, the taxpayer will not get it. And nor can para 34 of Schedule 10 to FA 2003 (as it currently stands) ride to the taxpayer’s rescue in such a case: see para 34A(2)(b).

51. The Court of Appeal did not expressly say that no claim for overpayment relief could be made in such a case, but simply noted at [47] (quoted above) that overpaid tax cannot be reclaimed unless Part 6 Schedule 10 provides a remedy.

52. The present arguments were not put to the Upper Tribunal in Candy, and we have reached our conclusion based on the detailed submissions we have heard. At most, what is said by the Upper Tribunal in the last sentence of [112] is consistent with the conclusion we have already reached. Likewise, what was said by the FTT in Smith Homes 9 v HM Revenue & Customs [2022] UKFTT 5 (TC) at [81] and [82] and in Secure Service Limited v HM Revenue & Customs [2020] UKFTT 59 (TC) at [47] and [48] merely fortifies us in the conclusion we have already reached.

Conclusion

53. For the reasons given above we are satisfied that the FTT was right to find that each of the appellants had made a mistake consisting of failing to make a claim for multiple dwellings relief. Their claims for overpayment relief were therefore excluded by Case A. There was no error of law in the FTT’s Decision and we dismiss the appeals.

JONATHAN CANNAN ANDREW SCOTT

UPPER TRIBUNAL JUDGES

![]() RELEASE DATE: 15 April 2025

RELEASE DATE: 15 April 2025

ANNEX