Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Awinoron & Anor v London Borough of Barking and Dagenham (RESTRICTIVE COVENANT - MODIFICATION - erection of enclosed porch extension across part of previously shared communal porch - erection of boundary fence to front garden severing previously shared communal access - restriction preventing alteration or addition without written consent - whether restriction should be deemed obsolete - whether restriction secures practical benefits of substantial value or advantage - whether money would be adequate compensation for loss or disadvantage) [2025] UKUT 139 (LC) (22 May 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2025/139.html

Cite as: [2025] UKUT 139 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 84 OF THE LAW OF PROPERTY ACT 1925

B e f o r e :

____________________

| TEGA AWINORON AND EDWARD EDIRIN OTOMIEWO |

Applicants |

|

| - and - |

||

| LONDON BOROUGH OF BARKING AND DAGENHAM |

Objector |

|

16 Urswick Road, Dagenham, Essex, RM9 6EA |

____________________

Ms Natalie Pratt, instructed by Legal Services, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

12 February 2025

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- Urswick Road sits within an extensive area of terraced and semi-detached housing built between the wars by the London County Council and known as the Becontree Estate ("the estate"). Ownership of the estate subsequently passed to the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham ("the objector"). Through the Right to Buy Scheme, introduced in the Housing Act 1980, some of the properties have been sold into private ownership, subject to restrictive covenants in favour of the objector.

- The applicants are the owners of 16 Urswick Road ("the property") who seek modification of a restrictive covenant burdening the property to enable them to retain a porch and boundary fence ("the works") erected in 2021 in breach of the covenant. The objector owns and lets the adjoining property at 18 Urswick Road ("No 18"), which has been affected by the works.

- This application was made on 10 June 2024, during a period when the applicants were subject to injunction proceedings ("the proceedings") by the objectors. On 15 July 2024 the objector was granted an injunction by District Judge Goodchild in the County Court at Romford requiring demolition of the works and restoration of the communal porch to its original condition. I understand that enforcement of the injunction is the subject of an appeal.

- I carried out an inspection of the works at the property and No 18 on 11 February 2025 accompanied by the first applicant, Ms Tega Owinoron and Mr Grant Rome, Landlord Services Manager for the objector. Ms Anisa Osman was also in attendance for the objector. I also walked along other roads in the estate to see other properties with single private porches, as referred to by Ms Owinoron in her witness statement.

- At the hearing on 12 February 2025 the applicants were represented by Mr Ashley Thompson, who called Ms Owinoron to give evidence. The objector was represented by Ms Natalie Pratt, who called Mr Rome to give evidence. Mr Rome had been in the objector's employment since 1983, and had worked in the housing department since 1990, but had not visited the property or No 18 before the works commenced.

- It had been intended that a transcript of the judgment of District Judge Goodchild handed down on 15 July 2024 would be included in the hearing bundle, but it had not become available by the date of the hearing. Directions were agreed that the transcript should be provided by 28 February 2025, with submissions for the applicants to be made by 7 March 2025 and submissions in response for the objector by 14 March 2025.

- The property was first transferred into private ownership by a deed of transfer ("the transfer deed") between the Mayor and Burgesses of the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham ("the Corporation") and Stephen Francis O'Donnell ("the transferee") dated 25 October 1982. Clause 4 of the transfer set out the transferee's covenants and stated, so far as relevant:

- The property was purchased by the applicants on 11 December 2015. The applicants' register of title states in the Charges Register that the transfer contains restrictive covenants, but does not provide details. The extract below, from title plan dated December 1982, shows the property and No 18 within a terrace of eight houses on Urswick Road.

- It can be seen from the plan that the terrace between numbers 14 and 28 Urswick Road includes three pairs of properties with shared open porches and undivided front gardens, the property and No 18 being one of those pairs. The design was repeated for the terrace on Nuneaton Road and I observed during my walk around other neighbouring roads that it was typical of many terraced properties in the estate, including 30 to 44 Urswick Road, even though that is not obvious on the plan. Some designs of shared porch, for example in Nuneaton Road, had an arched external opening. Others, including the one shared by the property and No 18, had a square external opening with a decorative ledge feature on each side.

- Photographs of the property and No 18 which pre-date the works show that the shared front porch was, unusually, enclosed by glazed double doors. These were in place when the applicants purchased the property in 2015. The photographs revealed that the glass was broken and the doors appeared to be in some disrepair. Mr Rome was unable to comment on the history of that earlier alteration, for which there was no consent on file, but he could confirm that the work would not have been done by the objector. The entrance through and behind the glazed doors had remained a communal one.

- Ms Owinoron explained that she and her husband had suffered from anti-social behaviour by their neighbours at No 18 ("the neighbours"), with whom they shared the front porch. People coming and going through the porch were noisy and it became unkempt with litter. The property had an open parking area in front of the house, whilst the front to No 18 was enclosed with a timber fence and had only a pedestrian gate. The applicants suffered further nuisance from the neighbours using the open parking area as an access to No 18, from their children riding bikes and playing in that area and, on occasion, from use of the area by the neighbours to park a car. The transfer deed included reciprocal rights of access over any existing pedestrian accessway, which would apply to the shared path to the communal porch, but not the remaining frontage of the property.

- The applicants saw that some other houses in the estate had added on private porches and in May 2021 they spoke to the neighbours to say that it was their intention to do the same. Ms Owinoron says that she and her husband believed the neighbours were owners of No 18. On 13 July 2021 the applicants' builder began work and explained to the neighbours the detail of proposed works. The neighbours then contacted the objector. Later that day, whilst at work, Ms Owinoron received a telephone call from Ms Eleanor Small, who worked for the objector, saying that consent was required for the works. Ms Owinoron took Ms Small's telephone number in order to ring her back after work. Meanwhile, she asked the builder to cease works.

- Ms Owinoron was unable to get any response from Ms Small's number when she rang back and was unable to trace her at the objector's offices. The objector says that their former Landlord Services Officer, Mr Joe Costello, sent an email on 14 July 2021 requesting that the works cease. However, Mr Costello has left the objector's employment and there is no evidence provided to me of the contents of that email.

- On 15 July 2021 the applicants applied, through an architectural agent, to the objector's planning department for a Lawful Development Certificate ("LDC") for the construction of a front porch, assuming that this was the consent required. In cross-examination Ms Owinoron agreed that Mr Costello had contacted her in early August to say that the objector was not going to give consent for the works. She agreed that a visit was made to the property by Mr Costello, when voices were raised between him and the second applicant. The LDC was granted on 16 August 2021 and Ms Owinoron assumed this was the consent previously referred to by Mr Costello as being withheld.

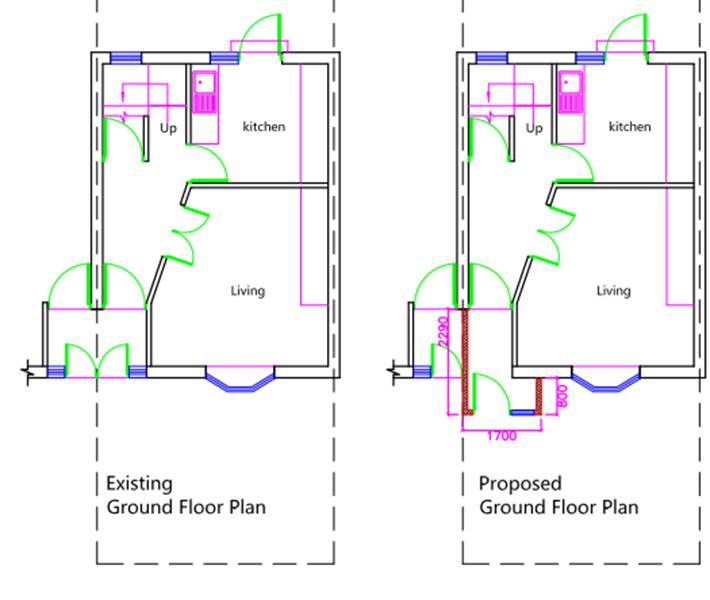

- The approved floor plan and front elevation drawings are shown below.

- Messages were sent to the objector's offices by Ms Owinoron on 26 and 27 August 2021 stating the applicants' intention to proceed with the works, having received the LDC, and asking if she should inform "the council (housing)" before starting work and whether building control was needed. A reply provided the email address for building control. On 6 September 2021 at 15.45, in response to an email from Mr Costello, Ms Owinoron sent a copy of the LDC (which she described as "the council permission letter"). At 15.49 he replied: "I have received your email but am strongly advising you not to start the work as I believe you have been granted permission in error. My manager is looking into it as a matter of urgency." At 17.43 Ms Owinoron replied: "I don't agree that the planning permission from the council was an error because alot of people in the area have done the same thing and I don't see any reason why mine should be any different."

- Ms Owinoron heard nothing further and gave instructions for work to proceed. By 18 September 2021 the works were completed. Preparatory work had involved dismantling the existing glazed doors enclosing the porch, the ledge walls on either side, and the glazing above the doors and the ledge walls. The new porch structure to the property is 1700mm wide and projects 800mm forward of the property. In front of No 18, the wall to the left of the entrance was made good as a vertical side to an open entrance measuring 930mm in width. The quarry tile floor of the original porch does not extend over the newly exposed floor area, which has been poorly repaired with cement. A narrow fence has been erected from the pavement through to the side of the new porch, down the centre of the previously shared concrete path. This has narrowed the pedestrian entrance to the front garden of No 18 so that wheelie bins cannot now be moved through it.

- The photograph below shows the way in which the objector's property at No 18 has been affected by the works. Mr Rome reported that the neighbours in No 18 now found the house colder without the original enclosed porch. However, on my site inspection it was apparent that the front door to No 18 is an exterior door of the sort present on the majority of the objector's other houses, all of which have open fronted porches. He also reported that the neighbours suffered from a restricted access through the narrower porch which made it difficult to bring furniture in and out. On my site inspection I noted, and pointed out to Mr Rome, an accessibility handrail that is located on the left hand interior wall of the entrance to No 18, which I consider will contribute to difficulties in moving furniture through that area.

- On 30 December 2021 the objector issued a claim for an injunction, requiring the applicants to demolish the works and reinstate the communal entrance. The applicants first instructed solicitors to represent them for the pre-trial review of the proceedings in June 2024, at which point this application was made. The history of the proceedings is not relevant to this application until on 15 July 2024 District Judge Goodchild at the County Court at Romford granted the objector both mandatory and prohibitory injunctive relief in relation to the breach of covenant at clause 4(iii) of the transfer deed. A transcript of the judgment was made available after the hearing.

- Section 84(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925 gives the Tribunal power to discharge or modify any restriction on the use of freehold land on being satisfied of certain conditions.

- Ground (a) of section 84(1) is satisfied where it is shown that by reason of changes in the

character of the property or neighbourhood or other circumstances of the case that the

Tribunal may deem material, the restriction ought to be deemed obsolete. - Ground (aa) of section 84(1) is satisfied where it is shown that the continued existence of the restriction would impede some reasonable use of the land for public or private purposes or that it would do so unless modified. By section 84(1A), in a case where condition (aa) is relied on, the Tribunal may discharge or modify the restriction if it is satisfied that, in impeding the suggested use, the restriction either secures "no practical benefits of substantial value or advantage" to the person with the benefit of the restriction, or that it is contrary to the public interest. The Tribunal must also be satisfied that money will provide adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which that person will suffer from the discharge or modification.

- In determining whether the requirements of sub-section (1A) are satisfied, and whether a restriction ought to be discharged or modified, the Tribunal is required by sub-section (1B) to take into account "the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permissions in the relevant areas, as well as the period at which and context in which the restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances."

- If the applicant is able to establish that the Tribunal has jurisdiction to modify the covenant, the Tribunal must then decide whether to exercise its discretion to do so. If it does, the Tribunal may also direct the payment of compensation to any person entitled to the benefit of the restriction to make up for any loss or disadvantage suffered by that person as a result of the discharge or modification, or to make up for any effect which the restriction had, when it was imposed, in reducing the consideration then received for the land affected by it.

- If the applicant agrees, the Tribunal may also impose some additional restriction on the land at the same time as discharging or modifying the original restriction.

- Initially the application was for modification under section 84(1) grounds (a) and (aa) of both clause 4(iii) ("the alterations covenant") and clause 4(iv) ("the nuisance covenant"). Mr Thompson explained that the nuisance covenant was included because it made reference to actions which may "...tend to depreciate the value of any adjoining or neighbouring property" and he said it would make sense to modify the two covenants hand-in-hand, even though the objector had not pursued breach of the nuisance covenant in the injunction proceedings. In closings, he confirmed that the applicants no longer sought modification of the nuisance covenant. I will therefore refer simply to "the covenant" as meaning the alterations covenant.

- For the application under ground (a) Mr Thompson cited the case of Adams v Sherwood [2018] UKUT 411 (LC) where the Tribunal (Deputy President Martin Rodger QC and Mr Andrew Trott FRICS) identified four connected matters to be considered for an application under ground (a):

- For the applicants, Mr Thompson agreed that the purpose of the covenant was to preserve the aesthetic of the community, i.e. to maintain the character of the neighbourhood, but disputed the objector's submission that the purpose was also to guard against unwanted changes to the character and amenity of the objector's own property, since that was prevented by the nuisance covenant.

- He submitted that the covenant was imposed over 42 years ago, when the objector owned a sufficient number of properties to warrant the imposition of a scheme of restrictive covenants to control the aesthetics of the neighbourhood. In cross-examination Mr Rome had been unable to confirm the proportion of properties remaining in the objector's ownership, but acknowledged that probably more than 50% of the stock had been sold. The applicants had identified 12 properties in the neighbourhood, within a radius of 0.6 miles, where similar works had been undertaken to provide private porches which required a previously open shared porch to be split. The objector had confirmed that none of the properties adjoining those 12 remained in its ownership. There has been significant change to the makeup and character of the neighbourhood, by virtue of the sale of more than 50% of the properties, and Mr Thompson submitted that since the objector only enforces the covenant where it owns a neighbouring property, the original purpose of the covenant can no longer be achieved and it should be deemed obsolete.

- For ground (aa), it had been agreed by the objector that the use is reasonable, as evidenced by the LDC, and that the use is impeded by the covenant. It was submitted for the applicants that the objector could not demonstrate that the covenant secured for it practical benefits of substantial value or advantage. It has only a reversionary interest in No 18, and the tenant in occupation has lifetime security, so the only practical benefit secured is in limiting injury to its reversionary interest. In Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council v Alwiyah Developments (1986) 52 P&CR the Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the Lands Tribunal that restrictions preventing development of land adjoining houses belonging to Stockport MBC did not secure to it practical benefits of substantial value or advantage. The restrictions secured the benefit of good views from some of the houses and modification to permit development would only result in diminution in value of the reversionary interest when the occupants of those houses exercised their Right to Buy under the Housing Act 1980. The Lands Tribunal awarded compensation of £2,250, being the future market value loss of 11 houses which benefited from the view.

- Similarly in Re Da Costa's Application (1986) 52 P & CR 99 the Lands Tribunal (V.G. Wellings Esq, QC) held that where a house had the benefit of a restriction over neighbouring land, but the freeholder held only a reversionary interest in it, the restriction did not secure practical benefits of substantial value or advantage. Money would be adequate compensation for injury to the reversionary interest caused by modification of the restrictions.

- In this case the objector relied on the written evidence of the neighbours, which was produced for the proceedings but only appended to Mr Rome's statement for this application, to assert that the works have caused access difficulties and a loss of amenity to the occupiers of No 18. It was submitted that the Tribunal should give little or no weight to that evidence, which could not be tested. The objector had also asserted that retention of the works would constrain its ability to allocate No 18 as housing for tenants with disabilities, but no evidence had been adduced to support that assertion. The applicants accepted that the works had involved some alteration to the wall and floor of the entrance to No 18, but Ms Owinoron had pointed out the poor state of the previous glazed double doors, which indicated that the objector was not supporting its tenants by taking good care of its property.

- Mr Thompson submitted that modification to permit the works would cause no loss of value to the objector's reversionary interest, and the objector had adduced no evidence to demonstrate such a loss, so the Tribunal could modify without awarding more than de minimis compensation.

- Ms Pratt reiterated that the covenant was not an absolute prohibition on alterations, but a requirement for the permission of the objector to be obtained first. The objector is the original covenantee and is best placed to understand the purpose of the covenant, which she said was two fold. The first purpose was to maintain the character of the neighbourhood and keep the buildings of original and uniform design. She submitted that the first purpose can still be served generally because the requirement to seek the objector's permission for alterations gives it the opportunity to review a proposal to ensure that it would not alter the original design of the property and upset the character of the neighbourhood. The applicants had alleged that there were sufficient porch constructions to have created a change in the character of the neighbourhood, but 12 properties across 10 roads (and only one in Urswick Road) is a small number spread across a wide area. They were examples where the objector had not been asked to give permission because it did not own neighbouring property benefiting from the covenant.

- The second purpose was to assist the objector in guarding against unwanted changes to the character and amenity of its own property. The breach of the covenant had affected the objector's property at No 18 by removing an enclosed porch and narrowing the entrance to a single door, reportedly causing the neighbours to suffer access issues and a decreased temperature at the property. The clause therefore continues to have a purpose in guarding against unwanted changes to the objector's property. That purpose can still be fulfilled, as Mr Rome explained when he described how a similar situation had arisen on the estate at Green Lane, some two miles away, where a private porch had been constructed in a communal entrance to the objector's property without its consent. The objector sent a letter before action, met several times with the owner and the builder and it was agreed in February 2023 that the porch would be restored to its previous communal arrangement. Mr Rome also referred to a similar breach at Valence Wood Road, also some two miles away, where a single porch was in the process of construction in a communal entrance. The objector had advised the owner that it would enforce the covenant if building works were not stopped and the communal porch reinstated. Negotiations were said to be in progress. It had been submitted by the applicants that these two examples were outside the immediate neighbourhood of the property but, in response, Ms Pratt pointed out that only three of the applicants' 12 porch examples were located on roads nearby.

- In summary, Ms Pratt submitted that there had been no change in the character of the property or the neighbourhood or other material circumstance by reason of which the covenant ought to be deemed obsolete. Changes in the character of the property had been made in breach of covenant and District Judge Goodchild would not have granted injunctive relief to remedy the breach of covenant if it was, or ought to be deemed, obsolete. The applicants had not sought to appeal the grant of injunctive relief so have impliedly acknowledged that it is not obsolete.

- Responding to the application under ground (aa), Ms Pratt submitted that impeding the works secured practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to the objector in preserving the character of the neighbourhood and in guarding against unwanted changes to the character and amenity of its own property. The objector may only have a reversionary interest, but it has a duty to its tenants, who suffer from the impact of the works. Being able to preserve the communal porch is a practical benefit of substantial advantage which allows the objector to allocate housing to vulnerable people with disabilities. Restricted access constrains the future occupancy of the objector's property.

- Ms Pratt submitted that money would not be adequate compensation for loss or disadvantage suffered by reason of modification. District Judge Goodchild had accepted that damages in lieu of an injunction would not be an adequate remedy for the harms suffered by the breach of covenant, taking into account day-to-day harm said to be caused to the neighbours, and the lack of evidence from the applicants as to a suitable sum.

- The submissions of both parties on ground (a) have merit and the answer on obsolescence is not clear cut. The original purpose of the covenant in preserving the character of the neighbourhood, that is its visual amenity and appearance, is obvious and undisputed. Ms Pratt described it as keeping the buildings in their original and uniform design. However, the ownership structure of the neighbourhood has changed over the 42 years since the covenant was imposed, in locations and at times beyond the control of the objector. This was apparent to me when I walked the neighbourhood and saw alterations which have given rise to a variety of styles of doors and windows, bay window additions, porch additions and removal of fences so that front gardens could be paved and used for parking. Under the terms of the deed of transfer the objector could have enforced the covenant over any of the sold properties to prevent the alterations described. It has chosen not to do so and has thus allowed the appearance of the neighbourhood to change over time. Photographs of the property before the works show that, in addition to the unauthorised glazed double porch, it had a bay window addition and a paved front garden, so the appearance of the property had also changed before the works took place. It is ironic that the objector has sought through the proceedings to have the applicants reinstate what was already an unauthorised modification.

- I consider that, by reason of changes in the character of the property and the neighbourhood since the covenant was imposed, the original purpose of the covenant in preserving the character of the neighbourhood as a whole can no longer be achieved.

- However, turning to the secondary purpose of the covenant, in assisting the objector to guard against changes to the character and amenity of its own property, I can see that this has a particular relevance on the estate where communal porches are an original defining feature. Mr Rome confirmed that the objector only enforces the covenant where it retains ownership of an adjoining property. The existence of unauthorised changes to the property before the works suggests that, even when it does own adjoining property, the enforcement is selectively focused on changes which have a direct impact on the objector's property.

- The photograph included above shows the impact which the works have had on No 18. However unsightly the split porch arrangement looks, as Ms Owinoron pointed out in photographs attached to her evidence, and as I saw for myself, the situation is not uncommon on the estate. It is apparently possible to live with a narrower entrance created by a split porch and, whilst the change may be unwanted, for reasons that I have already explained I am not persuaded that the split porch at No 18 creates a particular problem for the neighbours. However, the applicants have gone too far in carrying out work to the objector's property without consent, which is an act of trespass.

- In contrast, the erection of a dividing fence has created significant problems for the neighbours. The original layout involved a wide communal path to the porch, with shared access rights. The gatepost which the applicants have moved to the centre line does appear from the title plan to have been originally on their property but, by moving it and erecting a boundary fence, they have deprived the neighbours of the benefit of shared access along the communal path.

- It is obviously essential for the objector to guard against changes such as those which have taken place at the property and No 18, insofar as they have an impact on its tenants. The fact that the objector continues to take enforcement action in response to similar situations means that the secondary purpose of the covenant, assisting it to guard against changes to the character and amenity of its retained property, can still be achieved.

- Overall, I consider that the covenant ought not to be deemed obsolete.

- Turning to ground (aa), Ms Pratt submitted that the practical benefits secured to the objector in general by the covenant were the same as those relied on in the objection under ground (a), that is the ability to preserve the character of the neighbourhood and the ability to guard against unwanted changes to the character and amenity of its own property. For the reasons explained in my review of ground (a) above, I am persuaded that the ability to guard against unauthorised changes to its retained property is a practical benefit to the objector in this case. That benefit takes into account the objector's duty as landlord to ensure that their tenants they do not suffer from the impact of such changes. Mr Thompson is correct in saying that the objector produced no evidence to support its additional submission that impeding the works in this application, and preserving the communal porch, secures practical benefits through the ability to allocate housing to a full range of tenants, including those with access difficulties. It is not obvious that the original glazed porch would have been suitable for disabled access, but the point is one to which I give some weight, bearing in mind that there is already an access rail in the porch to No 18.

- I have heard no evidence on whether the practical benefit secured to the objector is of substantial value, and no evidence on whether money would be an adequate compensation for the loss which would arise from modification. Ms Pratt relied on the finding of District Judge Goodchild that damages would not be an adequate remedy for the harms suffered by the breach of covenant. Mr Thompson simply submitted that modification would cause no loss of value to the objector's reversionary interest.

- Ms Pratt submitted that the covenant secured to the objector a practical benefit of substantial advantage, but I am not persuaded that there is sufficient evidence to call the advantage substantial. However, even where the advantage of a benefit is not substantial, I only have jurisdiction under section 84(1) to modify a restriction if money would be an adequate compensation for the loss suffered by modification. The lack of evidence on this from either party, supported by the conclusions previously drawn by District Judge Goodchild, lead me to conclude that this case is a rare example of one where the advantage of a practical benefit cannot be measured in monetary terms.

- I consider therefore that I do not have jurisdiction to modify the covenant to permit the works.

- It was the crux of the objector's case that even if I found that one of the grounds for modification was made out, I should refuse to exercise my discretion to grant it because the breach had been cynical in nature. Although I have concluded that I do not have jurisdiction to modify, and discretion does not therefore need to be exercised, I will comment on the nature of the breach, in recognition of the unfortunate circumstances in which the applicants find themselves.

- Use of the phrase "cynical breach" in this context arose in the decision of the Supreme Court in Alexander Devine Children's Cancer Trust v Housing Solutions Ltd [2020] 1 WLR 4783 (SC) which considered in particular how an applicant's conduct should be taken into account by the Tribunal in the exercise of its discretion. The Tribunal, at first instance, had described the behaviour of Millgate as "highhanded and opportunistic". At [36] Lord Burrows said:

- The evidence of Ms Owinoron suggests that the applicants had suffered from anti-social behaviour in shared use of the communal porch and access path, so their determination to erect a private porch and a dividing fence is understandable in that context. It was naïve of them to carry out so little due diligence about the ownership of No 18 before commencing the works, but the fact that they applied for a LDC immediately they were told they needed consent points to misunderstanding rather than opportunism. When the applicants recommenced and completed the works they had the benefit of a LDC and nothing in writing to explain the effect of the covenant. By this stage they must have understood that the objector would try to prevent them from completing and retaining the works, even if the reason was still not clear to them. Their determination to proceed was a challenge to the objector's opposition, but the works were carried out for peace of mind, not for profit.

- It is unfortunate that the objector's approach to estate management in this case did not include informed engagement with the applicants at the outset, when the works were commenced and then paused, so that they could have understood properly the nature of breach they were about to commit.

- I determine that I have no jurisdiction to modify the covenant under ground (a), that it ought to be deemed obsolete.

- I determine further that I have no jurisdiction to modify the covenant under ground (aa) because it secures to the objector a practical benefit of advantage, and money would not be an adequate compensation for the disadvantage it would suffer from modification.

RESTRICTIVE COVENANT – MODIFICATION – erection of enclosed porch extension across part of previously shared communal porch – erection of boundary fence to front garden severing previously shared communal access – restriction preventing alteration or addition without written consent – whether restriction should be deemed obsolete – whether restriction secures practical benefits of substantial value or advantage – whether money would be adequate compensation for loss or disadvantage – application refused

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Adams v Sherwood [2018] UKUT 411 (LC)

Alexander Devine Children's Cancer Trust v Housing Solutions Ltd [2020] 1 WLR 4783 (SC)

Re Da Costa's Application (1986) 52 P & CR 99

Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council v Alwiyah Developments (1986) 52 P&CR

Introduction

Factual background and chronology

"4. THE Transferee for himself and his successors in title HEREBY COVENANTS with the Corporation TO THE INTENT that this covenant shall bind the property into whosoever hands the same may come for the benefit of so much of the remainder of the housing estate of the Corporation in which the property is situate as for the time being remains vested in the Corporation or any part thereof or such part thereof as may hereafter be disposed of by the Corporation with the benefit of this covenant that the Transferee and his successors in title will observe and perform the following restrictions conditions exceptions reservations and covenants:

...

(iii) Not at any time to suffer or permit the exterior of the property or any part thereof (including the gardens):

...

(b) to be altered or added to without the previous consent in writing of the Corporation (which may be subject to conditions) such consent not to be forthcoming unless the Corporation shall first have received written application therefor accompanied by such fee as may be prescribed from time to time by the Corporation

(iv) Not to do or permit or suffer to be done on or in respect of the property any act or bring or allow to remain on the property any thing which may be or grow to be a nuisance to the occupiers of the adjoining or neighbouring property or which may otherwise cause damage in any way to or affect the stability of or depreciate or tend to depreciate the value of any adjoining property

..."

Legal background

The application and submissions

"35. In determining whether the 1929 covenant can be discharged under ground (a) it is therefore necessary to consider a number of connected matters. It is first necessary to identify the purpose or object of the covenant, which may be stated in the instrument imposing the restriction or may be inferred from the nature of the restriction or from the known circumstances. Next it is necessary to ask whether the character of the property or the neighbourhood has changed since the covenant was imposed. Thirdly, whether the restriction has become obsolete by reason of those changes, in the sense that the object for which the restriction was imposed can no longer be achieved. Fourthly, and finally, whether some material circumstance other than a change in the character of the property or the neighbourhood has had that effect."

The objection and submissions

Discussion

Discretion

"36. I interject here that the description of Millgate's behaviour as "highhanded and opportunistic" is what some commentators, especially in the context of breach of contract, have described as "cynical": see, for example, Peter Birks, "Restitutionary Damages for Breach of Contract: Snepp and the Fusion of Law and Equity" [1989] LMCLQ 421. In line with this, I shall use the phrase "cynical breach" as a useful shorthand description of the conduct of Millgate in deliberately committing a breach of the restrictive covenant with a view to making profit from so doing."

Determination

Mrs D Martin TD MRICS FAAV

22 May 2025

Right of appeal

Any party has a right of appeal to the Court of Appeal on any point of law arising from this decision. The right of appeal may be exercised only with permission. An application for permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal must be sent or delivered to the Tribunal so that it is received within 1 month after the date on which this decision is sent to the parties (unless an application for costs is made within 14 days of the decision being sent to the parties, in which case an application for permission to appeal must be made within 1 month of the date on which the Tribunal's decision on costs is sent to the parties). An application for permission to appeal must identify the decision of the Tribunal to which it relates, identify the alleged error or errors of law in the decision, and state the result the party making the application is seeking. If the Tribunal refuses permission to appeal a further application may then be made to the Court of Appeal for permission.