Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Kay v Cunningham & Anor (RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - MODIFICATION - building scheme - covenant not to use historic house other than as a single private residence - Law of Property Act 1925, s.84) [2023] UKUT 251 (LC) (24 October 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2023/251.html

Cite as: [2023] UKUT 251 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

Neutral Citation Number: [2023] UKUT 251 (LC)

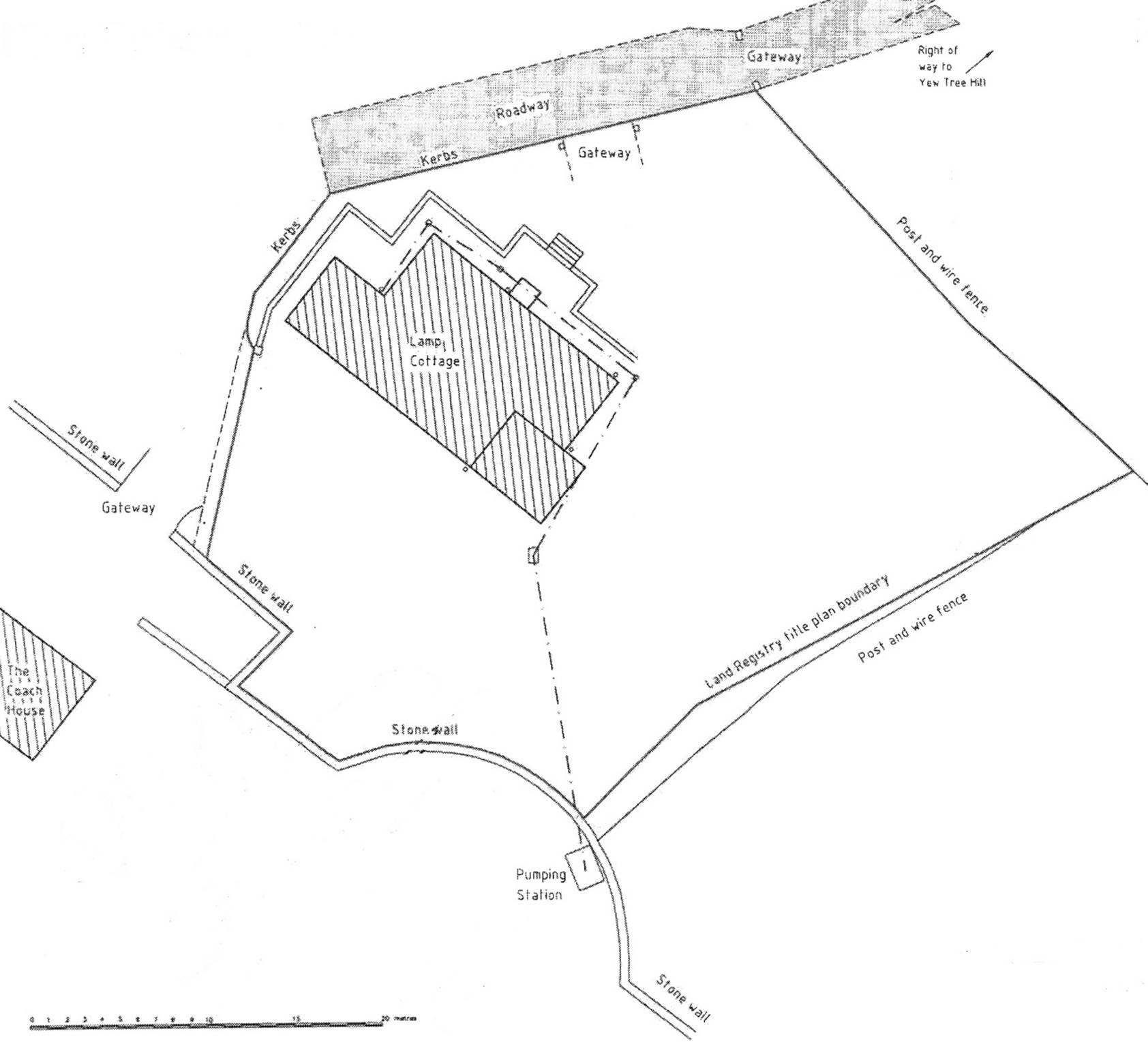

UTLC Case Number: LC-2022-579

Derby Civil Justice Centre and the Royal Courts of Justice

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 84 OF THE LAW OF PROPERTY ACT 1925

RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - MODIFICATION –– covenant not to use historic house other than as a single private residence - proposal to use five bedrooms for bed and breakfast purposes - whether covenant secures practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to neighbouring owner - application granted subject to acceptance of further restriction by applicant - Law of Property Act 1925, s84(1)(a)(aa)(b) and (c)

BETWEEN

|

|

PETER MARTIN KAY |

Applicant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

JOANNE SARAH CUNNINGHAM (1) BARRY NIX (2) |

Objectors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Re: Lea Hurst, Lea Shaw, Holloway, Matlock, DE4 5AT |

|

Mr Mark Higgin FRICS

26-27 July and 23 August 2023

Decision Date: 24 October 2023

David Peachey instructed by A City Law Firm Limited for the applicant

Andrew Francis instructed by BRM Law Limited for the objectors

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2023

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Alexander Devine Children’s Cancer Trust v Housing Solutions Ltd [2020] UKSC 45

Chatsworth Estates Ltd v Fewell [1931] 1 Ch 224

Hodgson v Cooke [2023] UKUT 41 (LC)

Re Bass Ltd’s Application (1973) 26 P&CR 156

Re The Trustees of Green Masjid and Madrasah [2013] UKUT 355(LC)

Introduction

1. Lea Hurst is a substantial house the origins of which date from the 17th century although it was considerably enlarged and refashioned in 1825. It was briefly the childhood home of Florence Nightingale but remained in the ownership of the Nightingale family until the First World War when ownership passed to the inheritors of Louis Hilary Shore Nightingale. It was sold in 1946 and a nursing home was established at the house by the Royal Surgical Aid Society.

2. The current owner of Lea Hurst and the applicant in this case is Mr Peter Kay. In 2019 Mr Kay decided to let rooms in the house on a bed and breakfast basis. Such a use breaches a covenant imposed in an earlier transfer of the house not to use Lea Hurst other than as “a single private residence”. The application now before the Tribunal seeks the modification of the covenant in order that the bed and breakfast activity can continue.

3. The application is objected to by Mrs Joanne Cunningham and her husband Mr Barry Nix, who live at Cressbrook Hall, some 20 miles north west of Lea Hurst. They also own Lamp Cottage, a detached house which occupies a site adjacent to land forming part of the Lea Hurst estate but some distance from the house itself. Lamp Cottage has the benefit of the covenant.

4. At the hearing of the application the applicants were represented by Mr David Peachey and the objectors by Mr Andrew Francis. Evidence of fact for the applicants was given by Mr Kay himself and Mr Anthony Jurkiw who is an adjoining landowner. I was also provided with a witness statement by Mr Jeremy Keck who acquired Lea Hurst in 2004. Mr Keck was abroad at the time of the hearing and therefore unable to attend. Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix also appeared as witnesses of fact. Expert valuation evidence was given by Mr Hugh Broadbent BA (Hons) MRICS for the applicant, and Mr Ruaraidh Adams-Cairns BSc FRICS for the objectors. I am grateful to them all.

5. On the day before the hearing, I inspected Lea Hurst and viewed the land that forms the estate with Mr Kay, Mr Peachey, Mr Francis and Ms Jacqueline Watts, solicitor for the applicant. I then visited Lamp Cottage where Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix were present, and I was accompanied by Mr Peachey, Mr Francis and Ms Watts.

The Facts

6. Before I describe the events that gave rise to the application it is germane to set out the position on the ground at Lea Hurst. It is located in the village of Holloway, a little over 3 miles southeast of Matlock and 5.5 miles north of Belper.

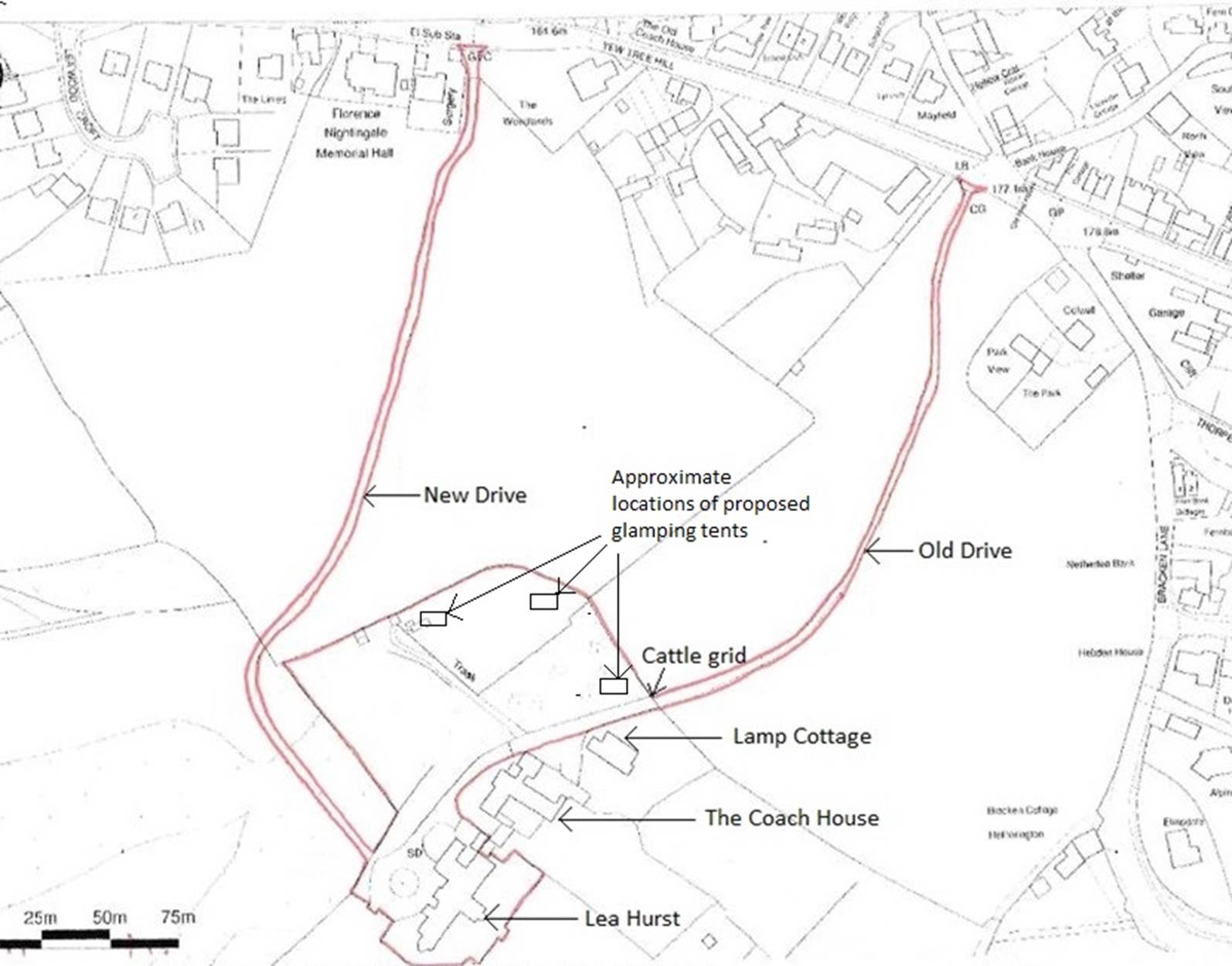

7. The house itself is an imposing Grade II listed dwelling constructed of local gritstone with a pitched slate roof. It is largely arranged over two floors but there is additional accommodation at second and third floor levels. In all, there are 15 bedrooms many of which have en-suite facilities. The house has formal gardens which face southeast, with views over the Derwent Valley, and substantial areas of grassland. The estate as a whole amounts to approximately 19 acres. Prior to 2005, when the nursing home use of the estate finished, it also comprised two additional buildings, The Coach House, an ‘L-shaped’ former coach house latterly used as ward space, and Lamp Cottage which was built in the 1960s as a house for the nursing home manager. The plan below shows the spatial relationship between the three buildings and the location of a cattle grid next to Lamp Cottage. The plan also shows the intended sites of three glamping tents, the relevance of which will become apparent later in the decision.

8. The plan also shows the means of access to the three buildings. These are labelled the ‘new’ and ‘old’ driveways. Paradoxically the ‘old’ driveway was not the original access, but it was the access that was in use while the Estate was used as a nursing home and continues to serve all three properties. It is owned by Mr Kay. At the point where it enters the forecourt of Lea Hurst a pair of high electric gates have been installed, thereby preventing any unwanted vehicular or pedestrian access. A cattle grid has also been installed adjacent to Lamp Cottage and close to the point where the driveway crosses the boundary between the grounds immediately surrounding the house and the wider estate. The ‘new’ driveway is actually a reinstatement of the original driveway used by the Nightingale family which was restored by Mr Kay in 2016. It has a crushed stone surface and there are three electric field gates over its course, presumably to restrict the movement of grazing livestock.

9. Mr Keck purchased Lea Hurst, The Coach House and Lamp Cottage from the Royal Surgical Aid Society in 2004 following the closure of the nursing home. Owing to changes in his personal circumstances his plans for the Estate altered and he put it back on the market. Mrs Cunningham (the first objector to the application) purchased The Coach House and Lamp Cottage. Her motivation for doing so and the circumstances of the sale will be explored later in the decision.

10. After the disposal of The Coach House and Lamp Cottage to Mrs Cunningham, Mr Keck sold the remainder of the Estate to Mr Robert Aram who spent three years converting Lea Hurst back into a family home. In the meantime, Mrs Cunningham had moved into Lamp Cottage and embarked upon its renovation. By 2008 these works were complete and Mrs Cunningham and her family had moved into The Coach House where renovation works were underway. Lamp Cottage was put on the market at £895,000 but in the midst of the banking crisis failed to find a buyer. Mrs Cunningham was assisted in negotiating the acquisition and in funding the works by her future husband and fellow objector, Mr Barry Nix, who moved to the Coach House in 2008.

11. In his witness statement Mr Nix explained that Lamp Cottage was let on a 12 or 18 month basis from 2010 and following that tenancy, shorter term lettings commenced in 2012/13. The property was used by the family during holiday periods and consequently was not available continuously for short term occupation. Lettings ceased in July 2022. Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix decided to market The Coach House for sale in early 2019 and an offer of £2.0m was received in February 2021, but later withdrawn. It was sold in August 2021 to Robert and Julia Dyas for £1.9m. The plan below shows Lamp Cottage and its immediate surroundings.

12. Mr Kay purchased Lea Hurst in February 2011 for £1.7m although he and his family did not move in until April 2014. He had an interest in the historical significance of the house and spent £1.0m on renovations using traditional and sympathetic techniques.

13. Aside from the completion of the new driveway Mr Kay also built a new double garage and created a room in the location of a covered walkway that previously linked Lea Hurst.

14. It is not in dispute that Mr Kay’s use of part of Lea Hurst as letting rooms is allowable in planning terms under permitted development rights. The rooms used for letting are situated on the first and second floors and are accessible from the main staircase. The first floor accommodation consists solely of the Florence Nightingale Suite, a double room with its own bathroom which is not en-suite. The second floor rooms comprise a family suite of two rooms and a bathroom, the Shore Suite and the Parthenope Suite which are both double rooms with en-suite facilities. Guests also have use of a study and balcony on the first floor, and lounge space on the ground floor. Mr Kay’s website, which is still available to view, describes the Florence Nightingale Suite as the Honeymoon Suite although weddings do not take place at the house. An earlier iteration of the site advertised ‘business facilities’ including meeting rooms, conferencing and events.

15. Mr Kay’s wish to make greater use of the Estate took another turn in the Spring of 2020 when he began to formulate plans for glamping tents in the former walled garden, now a grassed area to the north west of Lea Hurst and adjacent to the old driveway. A planning application was submitted in July 2020 and the plan after paragraph 7 above shows the intended locations of the three proposed tents.

16. A brochure appended to Mr Nix’s witness statement showed the tents to be ‘The Master Safari Lodge’ made by a company named Bond Fabrications. The brochure depicts one of a number of models measuring 11 x 6 metres and mentions that a four bedroomed glamping tent would comfortably sleep 8-12 people. The tents can also be supplied in a dormitory configuration sleeping up to 16 people. One of the tents would have been located close to Lamp Cottage. There appears to have been some confusion as to the exact nature of what was proposed, the highway authority having referred to ‘pods’ in their pre- application comments on the scheme, but in reality, the proposal was for tents. In the event, the planning application was refused in June 2021 and the notion of using the land for that purpose was dropped, Mr Kay describing the plans as “just an idea we had during the Covid-19 lockdown”.

17. In early 2020 Mr Kay was approached by Bagshaws, a firm of Land Agents with offices in Derbyshire, to submit parcels of land, comprising 6.9 acres of the Lea Hurst Estate, to Amber Valley Borough Council as part of their Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment. The land was situated to the north of the house and is transected by the new and old driveways. The assessed capacity of the land was 113 units but it was judged to be unsuitable for development owing to landscape and heritage issues.

18. In November 2021 Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix commenced proceedings in the Manchester Business and Property Court seeking, amongst other things, an injunction restraining Mr Kay from using Lea Hurst for any other purpose than as a single private residence. By an order dated 14 October 2022 the case was stayed until the outcome of this application is known. Mr Kay has not taken down his website or disabled links to third party sites such as Tripadvisor and both are still available to use.

The covenant

19. The covenant was imposed in a transfer dated 13 July 2005 between Mr Keck and Mrs Cunningham. It is as follows:

“not to use Lea Hurst other than as a single private residence” A second covenant relates to nuisance but does not form part of the application. It is worded as follows:

“not to do anything in or on the retained land and Lea Hurst that may be or may grow to be a nuisance annoyance or disturbance to the property”

The statutory provisions

20. Section 84(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925 gives the Tribunal power to discharge or modify any restriction on the use of freehold land on being satisfied of certain conditions. The applicant in this case relied on grounds (a), (aa), (b) and (c).

22. Ground (aa) is fulfilled where it is shown that the continued existence of the restriction would impede some reasonable use of the land for public or private purposes or that it would do so unless modified. By section 84(1A), in a case where condition (aa) is relied on, the Tribunal may discharge or modify the restriction if it is satisfied that, in impeding the suggested use, the restriction either secures “no practical benefits of substantial value or advantage” to the person with the benefit of the restriction, or that it is contrary to the public interest. The Tribunal must also be satisfied that money will provide adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which that person will suffer from the discharge or modification.

23. In determining whether the requirements of sub-section (1A) are satisfied, and whether a restriction ought to be discharged or modified, the Tribunal is required by sub-section (1B) to take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permissions in the area, as well as “the period at which and context in which the restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances.”

24. Ground (b) is fulfilled where it can be demonstrated that the persons of full age and capacity entitled to the benefit of the restriction have agreed, expressly or by implication, by their acts or omissions to the modification of the restriction.

25. The condition in ground (c) is satisfied where it can be shown that the proposed discharge or modification will not injure the persons entitled to the benefit of the restriction.

26. The Tribunal may also direct the payment of compensation to any person entitled to the

benefit of the restriction to make up for any loss or disadvantage suffered by that person as a result of the discharge or modification, or to make up for any effect which the restriction had, when it was imposed, in reducing the consideration then received for the land affected by it. If the applicant agrees, the Tribunal may also impose some additional restriction on the land at the same time as discharging the original restriction.

27. Should an applicant establish that the Tribunal has jurisdiction to modify the covenant, he has at that point only cleared the first hurdle; he then needs to persuade the Tribunal to exercise its discretion. This is a distinct and separate exercise although the Tribunal will not normally refuse modification if it is satisfied that jurisdiction has been made out. I now turn to the detail of the application.

The application

28. The application was made on 18 November 2022. The applicant wishes to use Lea Hurst to provide bed and breakfast services to paying guests and to that end seeks to modify the existing covenant as follows:

“(a) not to use Lea Hurst other than as a single private residence with or without additional accommodation of paying guests; and

(b) not to allow more than five rooms at a time to be used as bedrooms for the accommodation of paying guests in Lea Hurst.”

Mr Peachey said that Mr Kay only sought the modification to the extent necessary to enable the proposed, limited and ad hoc use of Lea Hurst. He was open to alternative or additional provisions and simply wanted a small number of people to experience Lea Hurst whilst generating funds to help preserve the house for future generations.

The objections

29. In their notice of objection Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix objected to all of the grounds advanced by the applicants. In relation to ground (a) they stated that there had been no changes to the character of Lea Hurst or of the benefited land in the 18 years since the imposition of the covenant.

30. As far as ground (aa) is concerned, the objectors accept that the covenant impedes the proposed use but deny that the proposed use is reasonable. They assert that the

covenant secures to them practical benefits of substantial value and advantage in upholding the peace and quiet, amenities and value of the benefited land. They also fear that alteration of the covenant will create an unfavourable precedent for future modifications. Furthermore, they deny that money would be an adequate compensation for the effect of the proposed modification. They regard any reliance on the public interest grounds as set out in s. 84(1A)(b) as fundamentally misconceived and dispute that the application under ground (b) is supported by any factual evidence. Similarly, in their objection to the application ground (c) the objectors dispute the applicant’s characterisation of Lamp Cottage as being not used as a private residence.

31. Mr Francis submitted that the conduct of Mr Kay amounted to a ‘cynical breach’ of the covenant. The fact that Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix had to obtain an injunction to restrain breaches of the covenant demonstrated that Mr Kay chose to ignore warnings in full knowledge of his obligations. A further reason for refusal is that the first objector is the original covenantee under the 2005 transfer and is entitled to rely on it.

Evidence for the applicant

Mr Peter Kay

32. In his witness statement Mr Kay explained that in August 2019 he began to make incidental use of Lea Hurst to generate a modest income to try to offset the cost of running and maintaining the house and estate. At the hearing he commented that these costs amounted to yearly outgoings of approximately £50,000 excluding any significant repairs. He had received enquiries about the house from nurses and former nurses and he decided to rent out a few rooms on an ad hoc bed and breakfast basis to explore whether such a venture could generate the required financial support. His intention was to make the most of the connection to Florence Nightingale and styled the rooms as ‘The Florence Nightingale Suites at Lea Hurst’.

33. At the end of 2020 he heard through a third party that Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix were seeking to sell The Coach House and Lamp Cottage. The 2005 transfer of these properties placed obligations on Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix to repair stonework on the shared driveway, work which in his view had been long outstanding. Mr Kay instructed his solicitor to write to them requesting that the matter be dealt with before they departed. Mr Kay speculated that his request had upset Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix who subsequently started legal action to enforce the covenant that burdened Lea Hurst. Mr Kay did not consider that Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix were genuinely upset about the use of Lea Hurst as a bed and breakfast venture. At the time they were living in The Coach House and letting out the adjacent Lamp Cottage to paying guests through an agency. More than a year had elapsed between the arrival of Mr Kay’s first guests and the initiation of legal action against him.

34. Mr Kay considered that the foremost concern about his activities would be that noise from his guests would be a nuisance. However, his guests would be staying in his family home, and it would be contrary to his own interests to allow any noisy or disruptive behaviour; parties would not be permitted. He drew attention to an incident in July 2021 when he had been disturbed by a party at Lamp Cottage and complained to Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix. Their response, through their solicitors, was that the two houses were too far apart and separated by The Coach House for the sound to have caused a nuisance. This being the case Mr Kay could not understand how his guests could be heard at Lamp Cottage.

35. Mr Kay rejected the contention that he had ‘cynically breached’ the covenant. He said that he did not recall being told when he bought Lea Hurst that he could not use the property for a commercial use. He took the view that Lea Hurst had always remained a residence and that the use he had made of the house was within the covenant. He intended to use no more than five rooms as he was committed to running the operation between himself and his wife and not employ any outside staff. In his words, ‘we still want to feel like the house is our family home’. It was also his intention that the guests did not impact on the homely feel of the interior of the property, and he found it hard to see how they could affect the residents of Lamp Cottage.

36. Mr Kay considered that Lamp Cottage had not been occupied since spring 2022 when the last paying guests had departed. He described the distance between Lamp Cottage and Lea Hurst as being ‘approximately 75 metres as the crow flies’. He noted that the two houses are separated from one another by Leylandii hedges surrounding Lamp Cottage, a two metre high garden wall that runs along the boundary of The Coach House adjacent to Lamp Cottage, and a further substantial stone wall together with mature yew and leylandii hedging that constitutes the boundary between The Coach House and Lea Hurst. Mr Kay said that Lamp Cottage is now surrounded on two sides by three metre tall leylandii trees planted approximately seven years ago by Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix. He observed that Lea Hurst does not overlook Lamp Cottage, or The Coach House and that Lamp Cottage is only visible from the balcony of one room on the upper floor at the rear of Lea Hurst.

37. Regarding The Coach House, Mr Kay recalled that this property was purchased by Robert and Julia Dyas in August 2021. He said that his relationship with Mr Dyas was pleasant and appended messages from Mr Dyas to his witness statement which gave qualified approval to Mr Kay’s continued use of Lea Hurst for bed and breakfast purposes. The messages made plain Mr Dyas’s reluctance to becoming embroiled in the dispute but culminated in the following (timed at 18:32 on 22 August 2022):

“We can agree in principle to this, but would need to have legal advice to fully interpret the implications before formal written agreement. Hope that makes sense”.

38. In support of his contention that the surrounding area had changed over the last ten years Mr Kay provided details of six other properties that had commenced use as holiday lets or bed and breakfast establishments since 2011. All were located within a mile of Lea Hurst. He also drew attention to Lea Hall, which he described as a substantial Grade II* house once in the ownership of Florence Nightingale’s great uncle and the temporary residence of Florence’s immediate family in the 1820s when Lea Hurst was being refurbished. This house, which is 1.5 miles from Lea Hurst, has operated as a holiday let sleeping 22 since 2018.

39. Mr Kay confirmed in his witness statement that Metro Bank hold a charge over Lea Hurst and at the hearing he was candid about the terms of his mortgage and the amount outstanding. It is not necessary to record the details here. It is pertinent however to document that the bank restricts the period over which the property can be fully or partially let. In this case it is 90 days. They are aware of Mr Kay’s use of the property and have not objected.

40. The final component of Mr Kay’s evidence related to the new driveway which is single tracked and solely for the use of the occupants and visitors at Lea Hurst. A neighbouring landowner, Mr Jurkiw, had granted a right of way over part of his land to facilitate the connection of the driveway from Lea Hurst to the public highway at Yew Tree Hill. The driveway is some 500 metres in length and Mr Kay said that at no point along its length was Lamp Cottage visible as it was screened by mature trees. At its closest point it is more than 100 metres from Lamp Cottage.

Mr Jeremy Keck

41. In his witness statement Mr Keck described how in 2004 he had approached the Royal Surgical Aid Society via a third party and agreed a price for Lea Hurst in an ‘off market’ transaction. Mr Keck had previous experience of running care homes and mentioned that the Society felt it necessary to prevent him from selling the three buildings as a nursing home for a higher figure than his purchase price, although he provided no details about the means by which the restriction was to be achieved.

42. He explained that he never had any intention to operate Lea Hurst as a care home, his intention being to live in the house and to sell The Coach House and Lamp Cottage. Unfortunately, his plans did not wholly come to fruition as his wife was diagnosed with cancer shortly after the purchase and he decided to sell the entire estate. He was successful in selling The Coach House and Lamp Cottage to Mrs Cunningham. Mr Keck described Mrs Cunningham as being concerned that he might use Lea Hurst as a care home. In his view the covenant was not meant to prevent the use of a few bedrooms for paying guests.

Mr Anthony Jurkiw

43. Mr Jurkiw is resident at Nightingale Park Farm which as its name suggests adjoins Lea Hurst. In his witness statement he provided a brief history of Lea Hurst as he interpreted it. It is not necessary to set out the details as they align with the factual accounts provided by the other witnesses of fact. Mr Jurkiw said that he suggested to Mr Kay in 2016 that he should restore the original access to Lea Hurst and granted the right of way over his land. He supported the use of Lea Hurst for bed and breakfast purposes.

Evidence for the objectors

Mrs Joanne Cunningham

44. In her witness statement Mrs Cunningham recalled that in early 2005 she was newly divorced and had been living in rented accommodation. She was keen to find a family home for herself and her three children. She was aware that Mr Keck was trying to sell but she could not afford to purchase all three buildings. Her intention was to buy The Coach House and Lamp Cottage which would respectively provide a family home and a residential development property for resale. Mrs Cunningham was mindful that the Estate was in the Lea/Dethick/Holloway Conservation Area and the buffer zone for the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site. She was also conscious of the Listed status of Lea Hurst. This context provided what Mrs Cunningham described as “a very strong degree of protection from any further/future development”.

45. She described the Estate as very private with access along a 200 metre private driveway which was also gated. At the time she was a single mother of three young children and privacy and security were absolutely essential to her. Mrs Cunningham was concerned that Lea Hurst and the land that formed the Estate might be developed commercially, perhaps with the house being divided into smaller units, or as a hotel, amongst other possibilities. To protect the tranquil family location and her significant capital investment she insisted that the transfer should include a number of covenants that would benefit both The Coach House and Lamp Cottage, including one which explicitly prevented Lea Hurst and its grounds from being used for anything other than a single private residence. Mrs Cunningham acquired the properties in her own name but later transferred Lamp Cottage to Haddon Grove Ltd, a company in which she and Mr Nix were directors and shareholders. Lamp Cottage was transferred to Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix personally in October 2020.

46. During cross examination Mrs Cunningham was shown a Heritage Statement dated February 2023 for Alstonefield Hall in Staffordshire, a large historic house which she owns with Mr Nix. The statement was prepared in connection with a planning application to undertake remedial works and an extension. The extension was described in the statement as follows:

‘At present, the house is not large enough to meet the needs of the owner, who has a large family that he wishes to ensure can be accommodated at the house for family occasions. In addition, to enable the house to remain in use for its owners during their old age, an accessible ground floor bedroom with on suite bathroom are highly desirable.’

In response to a question from Mr Peachey about her retirement plans, Mrs Cunningham said that she was not intending to live at Alstonefield Hall but did consider it a few years earlier. She stated that she wanted to retire to Lamp Cottage but was not sure when. She denied that her intended move back to Lamp Cottage was a means to support her case.

Mr Barry Nix

47. Mr Nix confirmed Mrs Cunningham 's evidence about the series of events that led up to the acquisition of The Coach House and Lamp Cottage by Mrs Cunningham. Mr Nix said that he had advised Mrs Cunningham to ensure that Lea Hurst was only used as a single private dwelling and that if the covenant was intended to prevent use as a nursing home it would have said exactly that. Its purpose was to prevent any commercial activity.

48. He said that the relationship between Mr Kay and himself was initially amicable and they had often shared the costs of works to such as repairs to gates and a sewer pump. According to Mr Nix, Mr Kay started what Mr Nix described as ‘development creep’ in late 2019. This involved the advertising of ‘Airbnb/hotel suites’ at Lea Hurst and the first guests arrived prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

49. Mr Nix recalled that he first heard about Mr Kay’s plans for glamping pods in April 2020 as Mr Kay was soliciting Derby County Council Highways Authority with a pre-application submission for four pods. The planning application was subsequently amended to three tents and presented to Amber Valley Borough Council in July 2020. The application included a Travel Plan Statement which Mr Nix said clearly showed the true intentions of Mr Kay. It contained the following statement:

“The aim is to expand upon the existing bed and breakfast business and to provide an alternative accommodation for guests”.

This was, said Mr Nix, clear acceptance of his breach of the covenant but more importantly a reflection of his desire to make Lea Hurst ‘a very substantial money-spinning commercial enterprise’. Mr Nix estimated that the tent closest to Lamp Cottage would be at a distance of 10-20 metres. He speculated that Mr Kay had focused his initial planning enquires on the Highway Authority because he knew he would encounter difficulties with access.

50. He also noted that Mr Kay had offered to reduce the number of letting rooms in the house to take account of the additional capacity that three glamping pods would entail. Mr Nix described the offer as ‘disingenuous and a lie’ since it equated a suite for two people with a facility that could accommodate many more. He also drew a distinction between the pods mentioned by Council Officers and the tents that were the subject of the application, describing them as being ‘the equivalent of a four bedroom bungalow that can sleep up to 16 guests’. He calculated that there would be an additional 48 guests as well as 14 in the house. It is not clear how Mr Nix arrived at these figures, as the tents were only capable of sleeping 16 each in dormitory configuration and there was a maximum of 10 bed spaces at the house.

51. Such was Mr Nix’s concern at the proposals that he commissioned his own report into the traffic issues. The investigation was carried out by VIA Solutions, and they reported in October 2020. They noted that the County Council’s pre-application response used the term ‘glamping pods’ and that the applicant had advised the Highway Authority that the removal of permitted development rights to convert 3 bedrooms into guest accommodation would be balanced by a package of measures which maintained parity in terms of traffic generating uses to avoid further substantive concerns. VIA concluded that the actual proposals for glamping tents would accommodate between two and four times the number of people that would use glamping pods. They further concluded that the County Council had either been misinformed by the applicant or had misunderstood as to what was actually proposed on the site. Mr Nix interpreted these conclusions as an example of Mr Kay ‘doing whatever he can do to get his own way even if it means deceit’.

52. Mr Nix’s concerns did not stop there. Alongside what he described as Mr Kay’s ‘industrial glamping expansion of his B&B business’ Mr Kay was simultaneously exploring the possibility of securing a housing allocation on his land under the Council’s Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment. In his witness statement Mr Nix postulated that up to 200 houses could be built on a site that was located only 25 metres from Lamp Cottage. Documents attached to his statement made reference to a capacity of 113 houses. Mr Nix said that Mr Kay had not contacted him about any of his proposals and that it was clear that he was pushing for a rapid commercial expansion of the whole site. Mr Nix said he believed that Mr Kay was ‘fully aware that he was breaking the restrictive covenants with his B&B and his proposed developments’. He speculated that the ‘timing of his applications (during the COVID-19 crisis) was a deliberate and calculated attempt to try and push through these applications with as little resistance as possible. All of this is in breach of the restrictive covenants for which he has demonstrated a total disregard. He appears to have just decided the covenants do not apply to him’. At the hearing Mr Nix said that he did not engage with Mr Kay about the use of Lea Hurst because he was focused on fighting the glamping application, but he agreed that there was no obligation on Mr Kay to discuss his plans with him.

53. Mr Nix then turned to the use of the old driveway. He questioned why Mr Kay had directed his guests to use this means of access when the new driveway was available for use. He also remarked about the cattle grid immediately outside Lamp Cottage and stated that there had been a large increase in traffic using this route. The inference was that there had been a corresponding increase in noise as vehicles passed over it. On my inspection it was noted that all but one of the bolts securing the grid to its concrete sump were missing. Mr Nix was unaware that this was the case and consequently had not sought to secure it in an attempt to reduce the clatter of vehicles passing over it. He said at the hearing that it was installed in 2009 and he had not had cause to complain about the noise and none of the paying guests at Lamp Cottage had mentioned it either. He denied that he had left it in its current state in an attempt to improve his case.

Expert Evidence

54. Mr Broadbent gave evidence on behalf of the applicant. He qualified as chartered surveyor in 2013 and has been a director of Chartex, a Derbyshire based, general practice surveying and valuation company, since 2008. He has experience of both commercial and residential valuations, on freehold and leasehold properties as well as historic, SIPP and probate valuations.

55. Mr Adams-Cairns gave evidence on behalf of the respondent. He is a director of Savills UK Limited, head of Savills Litigation Support Department and past head of both Residential Valuations and the Savills Valuation Group.

56. Prior to the hearing they had discussed their respective valuations and reached a consensus that the value of Lamp Cottage, lay between £810,000 and £840,000.

57. Mr Broadbent’s report was concise but contained his views on the selection of comparables and an explanation of how he had arrived at his opinion of value in relation to Lamp Cottage. He originally put the value in the range £865,000 to £890,000. He provided details of five comparables, all situated within five miles of Lamp Cottage. He had analysed the transactions and arrived at a range from £3,411 to £6,512 per m2 on a gross internal basis. This sample contained a bungalow which had the highest analysis by a considerable margin. Mr Broadbent’s original conclusion was that the value for Lamp Cottage laid between £3,500 to £3,600 per m2. He had not inspected any of the properties.

58. In arriving at his opinion of value Mr Adams-Cairns had been assisted by three comparables; a detached house in a suburban position in Ashbourne, a detached house in a village three miles north west of Matlock and a period farmhouse in four acres of land just to the west of Belper. He too had not inspected any of them. His original conclusion was that the value of Lamp Cottage lay in the range £750,000 to £800,000 and he had settled on the mid-point of £775,000. At the hearing he explained that he had changed his mind about the value simply as a means to take account of a revision in the floor area, his original valuation having been based on a smaller, incorrect figure.

59. Although they had reached agreement about the approximate value of Lamp Cottage the expert’s views on the effect of modifying the covenant were divergent.

60. Mr Broadbent briefly explained that in his experience relatively minor issues

with noise, flooding, radon, mining or pollution have little effect on value. Valuation in reality, he said, is not that sensitive. At the hearing he described his approach to valuation as holistic and remarked that some factors that it might be expected to affect value, do not.

61. His view was that the shared private driveway was more likely to have an adverse effect on value, given the future maintenance liability, than any minor changes in occupancy at Lea Hurst. He also thought that Lamp Cottage and Lea Hurst were sufficiently far apart for any ‘minor noises’ not to cause any disruption and that in terms of traffic Lea Hurst would generate significant traffic movements if it was fully occupied. He considered that the current proposals were ‘much less than this’. He thought that the foot path that passed close to Lamp Cottage was more likely to have a detrimental effect that anything emanating from the neighbouring land.

62. He additionally said that a requirement for planning permission would offer some protection to the occupants of Lamp Cottage since it would usually be a requirement unless the proposed use was incidental to the main activity. In his view use of 30% of Lea Hurst for paying guests would be incidental, especially as the occupancy rate of these areas would generally be below the 100% occupancy of the areas that the family lives in. Mr Broadbent did not adduce any planning evidence to support this supposition or any calculations to verify that the areas involved actually amounted to 30% of the floor space. He did not say how he had treated areas that were shared between guests and the Kay family.

63. He concluded that the use of Lea Hurst for bed and breakfast would cause no disruption to Lamp Cottage because the additional use would be minimal, and the access would not be past Lamp Cottage. Furthermore, there would be no significant disturbance from the proposed activity and therefore no negative impact on the value of Lamp Cottage.

64. Mr Adams-Cairns approached the question of the effect of modifying the covenant by undertaking two valuations. The first, at £775,000, represented the market value of the freehold interest with vacant possession on the basis of a special assumption that the covenants were in place and had not been breached.

65. Mr Adams-Cairns then embarked on a further valuation, the basis of which was that the covenants at Lea Hurst has been modified to permit bed and breakfast use but also taking account of future uncertainty from possible additional commercial use and development.

66. This latter valuation was based on the assumption that the guests to Lea Hurst would only use the new driveway, a maximum of 5 bedrooms or 10 guests would be allowed, noisy or disruptive behaviour would not be tolerated, and no parties would be permitted. He went on to say that a prudent purchaser would be reassured by the restrictions but the nature of Lea Hurst meant that there were some additional considerations. These included the potential for further development including, but not limited to, a larger paying guest enterprise, a boutique hotel, a wedding venue and a luxury conferencing site. He noted that the scale of the building and that the number of rooms was more appropriate to a commercial use than a normal home. Finally, the high cost of owning and maintaining the house could mean that in the absence of paying guests the property could fall into disrepair. He thought that any owner of a house of this nature would seek to maximise the income generating potential and the capital value of the estate but in so doing would almost inevitably breach the covenants.

67. At the hearing Mr Adams-Cairns said that he had not been involved in selling a large house in Derbyshire since the 1980s but he had nevertheless formed the view that disposing of a house of the nature of Lea Hurst in this part of Derbyshire for a large price was likely to be problematical. He thought that it would be difficult for Mr Kay, if he came to sell, to recoup his financial and emotional expenditure. The corollary of this situation was that exploiting any development potential would be very important to him.

68. In his view the likely effect on Lamp Cottage of the uncertainty over future developments would be to reduce both the number of potential purchasers prepared to proceed and the amount they would be prepared to offer. Mr Adams-Cairns thought that there would be additional factors that would be in the mind of the prospective purchaser. The first of these was the degree of protection offered by the planning system. He acknowledged that the planning history of Lea Hurst demonstrated that the planning authority had been robust in their refusal of permission to develop the site, including the refusal of consent to convert the house into a museum, the refusal of the glamping pods and the fact that consent was only granted for the new driveway on appeal. However, he observed that the mere act of making a planning application on a neighbouring property can impact on marketability and lead to caution on the part of purchasers.

69. Traffic movements were the next item on Mr Adams-Cairns’ list of deleterious factors that could affect Lamp Cottage. He acknowledged that it was intended that guests at Lea Hurst would use the new driveway but thought this arrangement would be impractical because the new driveway has three locked gates and is narrow with no passing places.

In fact the gates are electrically operated and controlled from the house. Mr Adams-Cairns assumed that anyone parking at Lea Hurst would favour returning to the

public highway by following the old driveway which is shorter and has no gates. However, there is an electrically operated gate between Lea Hurst and the old driveway which is again controlled by Mr Kay. He also thought that any commercial enterprise would favour a one-way system using the new drive to come into the site and the old driveway to leave. He said that purchasers are inevitably influenced by passing traffic and traffic noise, the drive is very close and fear of the unknown, as in this case, can be greater than the eventual reality. His conclusion was that one-way system would be inconvenient and irritating for the owner of Lamp Cottage and that increased traffic would be passing nearby, and vehicles crossing the cattle grid would have a detrimental impact on value although he did not quantify it.

70. The final factor that Mr Adams-Cairns considered was disputes between neighbours. He thought that a prudent purchaser would be concerned about the difficulty in ‘policing’ the number of bedrooms utilised, or the additional services offered, future discord and potential legal costs for enforcement action or a further application to modify or discharge the covenant.

71. Having considered these various factors Mr Adams-Cairns moved on to what he described as ‘valuation considerations’ which appeared to mean the uncertainties and risk associated with a purchase of Lamp Cottage and in particular the impact of future development. His conclusion was that a housing estate on the land next to Lamp Cottage might have an impact of 10 to 15% on its value but conversion of Lea Hurst to a hotel would potentially reduce the value by 7.5% depending on the nature of the hotel. Objecting to an application to modify or discharge the covenant might cost £100,000 in legal and other fees. On the other hand, either scenario might not come to pass. Ultimately, he settled on a figure of £50,000 which resulted on the basis of his original figures, in a value of £725,000. On the revised figures agreed with Mr Broadbent it amounted to 6% of the mid-point value between £810,000 and £840,000. He stated that in his opinion such a discount would be broadly in line with what he would expect from the lower selling prices achieved for houses close to hotels, public houses and incompatible commercial uses. He noted that this was less than the discount which could result from new roads, industrial uses or adjacent new, comparatively low value housing developments, through which access is obtained.

72. At the hearing Mr Peachey asked Mr Adams-Cairns whether a prospective purchaser of Lamp Cottage who had no knowledge of the issues around the development of the Estate, would make any adjustment to his offer if he were to be faced just with the modification as sought. His answer was that the modification would have no effect. It was clear therefore that Mr Adams-Cairns considered that the only factor that would affect the value of Lamp Cottage was the uncertainty over what Mr Kay would do in terms of developing the Estate.

Discussion

73. I will deal firstly with ground (a) (obsolescence as a result of changes in the character of the property or neighbourhood). Mr Peachey submitted that the division of Mrs Cunningham 's plot in 2016 constituted a significant change to the neighbourhood. It could similarly be said that the earlier change of use of Lamp Cottage from a family home to a property for holiday letting was a change of similar magnitude but neither involved any physical alteration to the two properties, there was simply a change in the manner of occupation of one of them.

74. Mr Kay considered that the opening of several bed and breakfast establishments in the wider locality was an indication of the changing character of the neighbourhood but equally there could have been a number of properties that had reverted to residential use over the same period. The net effect was not quantified. The most obvious physical change to the locality was the reinstatement of the original driveway but in the context of the whole estate its effect was, in my view, minimal. Mr Francis drew attention to the comments of Farwell J in Chatsworth Estates Ltd v Fewell [1931] 1 Ch 224, where he said at 229:10:

“To succeed on [ground (a)] the defendant must show that there has been so

complete a change in the character of the neighbourhood that there is no longer

any value left in the covenants at all.”

In my view none of the alterations referred to by the applicant are sufficiently impactful to lead me to the conclusion that the covenant should be deemed obsolete.

75. Mr Peachey submitted that the covenant could no longer achieve the purpose originally sought by Mrs Cunningham, namely that it ensured privacy and tranquillity for her young family, when she insisted on its inclusion in the 2005 transfer. Mr Peachey’s contention was that since Mrs Cunningham’s family were now adults the covenant was defunct. However, that argument ignores the second limb of Mrs Cunningham's original justification, that the covenant protected her investment by preventing development of the Lea Hurst estate. Moreover, the benefit of the restriction is not personal to Mrs Cunningham and her current circumstances cannot be determinative; the restriction provides continuing protection for her and for future owners. In the circumstances I consider that the case under ground (a) has not been made out.

76. Turning to ground (aa), Mr Francis had identified a series of ‘key markers’ which he considered to provide the context for the examination of the familiar questions posed in Re Bass Ltd’s Application (1973) 26 P&CR 156. The first of these observations was that the covenant is in absolute terms and was agreed by the transferors to protect the interests of Mrs Cunningham. As such, he submitted, it may be said to have greater weight than that of a transferee’s covenant because in a situation between a willing buyer and willing seller it was more usual on sale of part for the transferee to be willing to encumber the property than the transferor.

77. It seems to me that the circumstances under which the agreement was made simply reflect the respective negotiating strength of the parties to the transaction. I cannot discern any reason why a covenant demanded by a transferee should be more resilient to alteration than one granted by a transferor and Mr Francis did not suggest any. On the other hand, the fact that the covenant was given to Mrs Cunningham herself, and not to some previous owner, is a matter to which I would be prepared to attach some weight if one of the statutory grounds was made out and it came to the exercise of the Tribunal’s discretion.

78. Mr Francis said that there was a very special reason why the covenant was agreed to, namely that Mrs Cunningham did not want the risk and uncertainty of a non-restrictive user at Lea Hurst. Mr Francis said in applying the user covenant just to Lea Hurst, rather than to the estate as a whole, the parties had engaged in ‘bespoke tailoring’ and the ‘red line’ of the covenant preserved it by not being qualified.

79. He went on to say that the objectors were using the covenants for their intended purpose; the control of development on the site. Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix were entitled to be concerned about the future especially as it would be difficult to ‘police’ the covenant where it to be modified. He described their fear of the future as rational given the behaviour of Mr Kay and the nature of Lea Hurst.

Is the proposed use reasonable?

80. Mr Peachey submitted that it was reasonable for a private owner of a heritage country house to use a few rooms for an ad-hoc bed and breakfast business. The question of whether it is done to help with the upkeep of the property was not, he said, relevant. He pointed out that the use was allowed under permitted development rights.

81. Mr Francis noted the change of use did not require planning permission and therefore have not been the subject of any public scrutiny. In most cases the question of whether the use was reasonable could be answered by looking at the grant or otherwise of planning permission. Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix did not admit that the user was reasonable but tellingly did not provide a reason for their position beyond stating that the fact that the house had been expensive to restore and run was not relevant in any consideration of whether the proposed use was reasonable.

82. I agree with Mr Peachey, the proposed use is reasonable and the fact that it does not require planning permission is an indication that it is a minor alteration to the use of the premises and one that would not normally give rise to concerns, even in a situation where properties are conjoined.

Does the covenant impede the proposed use?

83. It is accepted by the parties that the covenant impedes the proposed use. However, Mr Francis considered that the nuisance and annoyance covenant would also impede the proposed use. However, the application relates only to the covenant restricting the use of the house to a private dwelling and in the context of that covenant it is clear to me that the proposed use is impeded. There is no need for the purposes of the application to consider whether the nuisance and annoyance covenant would be breached.

Does prevention of the intended use secure practical benefits?

84. Mr Francis identified three practical benefits, firstly the protection of the amenity of peace and quiet, secondly the protection of ambience and thirdly the ability to control the use of Lea Hurst in absolute terms and the certainty this engendered.

85. The lack of a covenant governing the use of The Coach House is illuminating. It is immediately adjacent to Lamp Cottage and they share the same access route. If noise from whatever source was truly a concern it would be reasonable to assume that in agreeing to a sale of the property Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix would have ensured that the use of the property would have been restricted in the same terms as Lea Hurst.

86. It seems to me that noise arising from the proposed modification which could potentially disturb the occupants of Lamp Cottage might emanate from two sources; vehicles using the ‘old’ driveway and people in the gardens and outdoor space at Lea Hurst. The ‘old’ driveway serves three properties, Lea Hurst, The Coach House and Lamp Cottage. Lea Hurst has the benefit of the ‘new’ driveway and it is reasonable to assume that some traffic will use that route. Mr Kay had directed his guests to use that route and is prepared to agree to a limitation to that effect. It appears that there is just as great a risk of traffic noise at Lamp Cottage from the occupiers of The Coach House. It is currently in the ownership of Mr and Mrs Dyas and it is quite possible, in view of the fact that it contains six bedrooms, that they could decide to use it for holiday lettings or for bed and breakfast purposes. It is equally plausible that a future owner might have a large family with adult children who would have their own cars.

87. It was alleged that the cattle grid which is located just a few metres to the north of Lamp Cottage causes disturbance but none of the short term occupiers at Lamp Cottage had complained about it, and neither had Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix when they lived next door at The Coach House. If it actually was a nuisance, I would have expected measures to have been initiated to deaden the sound of vehicles traversing it, but nothing had been done about securing the grid to its concrete setting or fitting any kind of sound mitigation.

88. As far as noise from the garden of Lea Hurst is concerned, Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix denied that their clients holding a party in the garden of Lamp Cottage could be heard at Lea Hurst. Mr Kay put the distance between Lea Hurst and Lamp Cottage at 75 metres and the gardens of the properties are separated by The Coach House, two boundary walls and planting. It would be counter intuitive to expect sound of the same magnitude emanating from Lea Hurst to be audible at Lamp Cottage. On the other hand, I do not doubt Mr Kay’s sincerity when he says that he would not tolerate rowdy or boisterous behaviour in his home, but his successors in title might not be so sensitive. However, taking all of the circumstances into account, in my judgement the likelihood of the occupants of Lamp Cottage being disturbed by guests at Lea Hurst is negligible. The owner and occupier of The Coach House which is adjacent to Lea Hurst (unlike Lamp Cottage) have not objected to the modification and have given their tacit approval.

89. To some extent the factors that underpin peace and quiet are to be found in the preservation of ambience, the second benefit said by Mr Francis to be provided by the covenant. Mr Francis did not define ambience, but it seems to me to relate to the character and atmosphere of a particular setting. In the context of Lamp Cottage both components rely, to some degree, at least, on the physical setting adjacent to Lea Hurst and the wider estate. As the proposed modification will not alter the built environment of Lea Hurst it is difficult to comprehend how this aspect of ambience might be affected. Mr Peachey said that there was no evidence that the guests were even noticed when they were at Lea Hurst. This being the case it seems unlikely that they would have any impact on atmosphere.

90. The third of Mr Francis’s practical benefits is the ability to control the use of Lea Hurst and the certainty that arises as a result. The efficacy of this benefit is tempered by the planning context in which Lea Hurst exists. Applications to use Lea Hurst as a museum and the grounds for glamping have been turned down and a housing allocation rejected. It seems to me that the Listed status of Lea Hurst and its relationship to the wider planning environment places strict limits on the use of the house and the wider estate which render the protection offered by the covenant less important than it otherwise would be. That is not to say that it has no practical benefit as there could be instances, as in the current case, where the covenant prevents something that planning regulations permit. However, in the case of significant change that will have an impact on neighbours, the planning system and the way it applies to Lea Hurst, fulfils the same function as the covenant. Even if that were not the case any other proposal to develop the house or the estate would require a further application to the Tribunal and any such application would be determined on the facts and circumstances of that case.

Are the practical benefits of either substantial value or substantial advantage?

91. Mr Francis focused on the question of substantial advantage which he said attached to the protection secured by the covenant against the ‘precedent effect’ or what has come to be known as ‘the thin edge of the wedge’. He did not have in mind the circumstances that relate to ‘building scheme’ cases where, in his words, the fear is that a modification will result in the floodgates being opened to other applications in a similar vein. Instead, he had in mind the removal of the fear of what the applicant would do next if the modification were permitted. In Mr Francis’s evocative phraseology this was the opening of a door rather than floodgates.

92. I think the fears of Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix are misplaced. I have already alluded to the protection afforded by the planning system and the modification of the covenant to allow the use sought by Mr Kay would leave its primary purpose and effectiveness untrammelled. As the owner of Lea Hurst, Mr Kay is entitled to explore development proposals and is under no obligation to discuss them with his neighbours. The covenant does not prevent him from doing so, but it does provide a measure of comfort that every change will require an application for modification. Mr Peachey said that the ‘fat end of the wedge’ was the letting of seven rooms (the maximum under permitted development) and I am inclined to believe that his submission on this point is to be preferred.

93. Mr Adams-Cairns attempted to quantify the benefits secured by the restriction in value terms but conceded that the prospective purchaser when faced solely with the acquisition of Lamp Cottage with modification in place but ignoring the attempts at development, would not reduce his bid. Mr Francis disputed that this approach was appropriate; in his submission the proper measure was a comparison before and after modification assuming that the objectors are the willing buyers. Mr Adams-Cairns endeavoured to put a price on the uncertainty and the difficulty in ‘policing’ the covenant that he said that would ensue from modification and his analysis led him to a figure of £50,000. He said that he was guided by the costs that objecting to an application would entail and by the reductions in value that would accrue from various types of development on adjacent sites. Notwithstanding his long experience I would have been assisted by details of the examples he sought to rely on. Unfortunately, this evidence was missing from his report, and in any case related to actual developments rather the prospect of something being built, and I therefore have no means by which to judge whether his assessment was correct. Without this information his view amounts to little more than conjecture. In my view this is not a case where the practical benefits, such as they are, can be described as being substantial in value or advantage.

94. I do not accept that the covenant in its modified form would be difficult to ‘police’. Prospective guests will expect to be able to visit the website and see photographs and details of the rooms and facilities. It will be obvious how many rooms are being offered to guests and their availability. Mr Nix admitted as much at the hearing. It follows that I consider that ground (aa) is satisfied and I have jurisdiction to allow the application. As a corollary ground (c) is also made out.

95. Mr Kay did not pursue his application under ground (b).

96. Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix did not seek compensation and I have heard no evidence in this regard. In the circumstances it is not necessary for me to devote any further consideration to the matter.

Discretion

97. One of the grounds of the application having been satisfied it does not follow as a matter of course that the Tribunal will exercise its discretion to allow the modification or discharge of the covenant.

98. Mr Francis submitted that in the event that the Tribunal found itself in a position to use its discretion, there were several factors that should cause it not to do so. The first of these was that Mrs Cunningham is the original covenantee. This is certainly the case and is a factor I bear in mind, even though Lamp Cottage has been through two further transfers since Mrs Cunningham acquired it in 2005, firstly to Haddon Grove (a company in which Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix were shareholders) in 2016, and then back to Mrs Cunningham and Mr Nix in a personal capacity in 2020. It is also relevant that Mrs Cunningham only lived at Lamp Cottage between 2005 and 2008 and although she said that it was the couple’s intention to retire to the property their acquisition of Alstonefield Hall and their plans to make it suitable for retirement purposes casts doubt on their intentions.

99. Mr Francis’s second factor was that Mr Kay had been in knowing breach of the covenant and it would be unjust and inappropriate to allow the application. Mr Peachey rejected this contention and drew attention to the Tribunal’s decision in Hodgson v Cooke [2023] UKUT 41 (LC) where at paragraph 61 it said:

‘There is no doubt they were in breach and have remained so throughout the continuance of the application. But this case involves no opportunism or secrecy and the applicants are private individuals making use of their own home to make a living, not large scale property developers intent on a substantial profit.’

100. Mr Francis, in his third factor, thought that the Tribunal should exercise its discretion with caution, relying on the comments of Burrows JSC in Alexander Devine Children’s Cancer Trust v Housing Solutions Ltd [2020] UKSC 45, at [52]:

‘I also accept that the Upper Tribunal in the Trustees of the Green Masjid case was correct to say, at para 129, that once a jurisdictional ground has been established, the discretion to refuse the application should be “cautiously exercised”’

101. In Re The Trustees of Green Masjid and Madrasah [2013]UKUT 355(LC) the Tribunal (A J Trott FRICS) said at paragraph 129:

‘the purpose of section 84 of the 1925 Act is to enable applicants to obtain modification or discharge of restrictive covenants in circumstances where they can demonstrate statutory jurisdiction. Having satisfied me on the facts, and on the law as applied to those facts, that the Tribunal has such jurisdiction in this case, I am loath to exercise my discretion so as to deny the applicants the relief that they seek. Where jurisdiction has been established I consider that the discretion of the Tribunal to refused the application should only be cautiously exercised. It should not be exercised arbitrarily and, in my opinion, should not be exercised as, effectively, a punishment for the applicants’ conduct unless such conduct, in all the circumstances of the case, is shown to be egregious and unconscionable. On balance I do not consider the applicants’ conduct as so brazen as to justify refusal of the application.’

Mr Kay said that he did not consider that letting a few rooms breached the covenant and that Lea Hurst remained his home. However it must have been clear to him once High Court proceedings had commenced and he had made the application that his continued use of the property for bed and breakfast purposes violated the covenant. Notwithstanding Mr Kay’s attitude and his obvious reluctance to cease trading, in my view this is a situation that has more in common with Hodgson than Alexander Devine. His conduct was, in my view neither egregious nor unconscionable and, because the application concerns the future use of the house, rather than the physical development of the site, the Tribunal is not being presented with a fait accompli.

102. Both parties made submissions in relation to the risk of a claim to enforce the nuisance covenant if the restrictive covenant were to be modified. Mr Peachey thought that the assertion was flawed on the basis that it was not supported on the evidence. I agree, there was no evidence that any activity associated with the letting of rooms in Lea Hurst had caused a nuisance or was likely to in the future. Mr Peachey went further, relying on the Tribunal’s decision in Re O’Byrne [2018] UKUT 395 (LC) and further submitted that this argument only supported Mrs Cunningham’s and Mr Nix’s case if they would successfully obtain an injunction preventing nuisance, but the Tribunal does not have jurisdiction to determine whether such a claim would succeed. He also drew attention to the Tribunal’s conclusion at paragraph 78 of that decision that the correct approach is to modify the covenant and then ‘[leave] it to the parties to take such action as they thought appropriate’.

103. In coming to a decision to exercise my discretion in favour of Mr Kay I have balanced his behaviour in not recognising that he was in breach of the covenant, when it should have been self-evident that he was, against his apparently sincere desire to preserve a heritage asset and make it available for use albeit on a small scale to the paying public. He has spent a considerable sum to put Lea Hurst into a state where it can be enjoyed as a family home and small scale bed and breakfast establishment and I am inclined to believe that his motivation was, in part at least, altruistic rather than wholly pecuniary.

Determination

104. I am satisfied that grounds (aa) and (c) have been made out and that I should exercise my discretion to grant the modification. There is no credible evidence that shows that modifying the covenant in the terms sought by Mr Kay will have any effect on the interests of Mrs Cunningham or Mr Nix.

105. Subsection (1C) of the 1925 Act enables the Tribunal in modifying a covenant to add further provisions as appear to the Tribunal to be reasonable. It apparent to me that an additional precaution against disturbance can be achieved by restricting the movements of vehicles of paying guests to the new driveway and I have already mentioned Mr Kay’s acquiescence to such a stipulation. The parties are therefore invited to submit an agreed form of words that the Tribunal may incorporate into an order modifying the covenant.

Mark Higgin FRICS

24 October 2023

Right of appeal

Any party has a right of appeal to the Court of Appeal on any point of law arising from this decision. The right of appeal may be exercised only with permission. An application for permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal must be sent or delivered to the Tribunal so that it is received within 1 month after the date on which this decision is sent to the parties (unless an application for costs is made within 14 days of the decision being sent to the parties, in which case an application for permission to appeal must be made within 1 month of the date on which the Tribunal’s decision on costs is sent to the parties). An application for permission to appeal must identify the decision of the Tribunal to which it relates, identify the alleged error or errors of law in the decision, and state the result the party making the application is seeking. If the Tribunal refuses permission to appeal a further application may then be made to the Court of Appeal for permission.