Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Warren James (Jewellers) Ltd v Watford Borough Council (COMPENSATION - compulsory purchase - redevelopment of retail centre - relocation of jewellery business - disturbance - temporary & permanent loss of profit) [2023] UKUT 153 (LC) (20 July 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2023/153.html

Cite as: [2023] UKUT 153 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

Neutral citation number: [2023] UKUT 153 (LC)

UTLC No: LC-2021-571

Royal Courts of Justice, Strand,

London WC2A 2LL

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

IN THE MATTER OF A NOTICE OF REFERENCE

COMPENSATION - compulsory purchase - redevelopment of retail centre - relocation of jewellery business - disturbance - temporary loss of profit - permanent loss of profit - compensation determined at ££647,510.95

BETWEEN:

WARREN JAMES (JEWELLERS)

LIMITED

Claimant

-and-

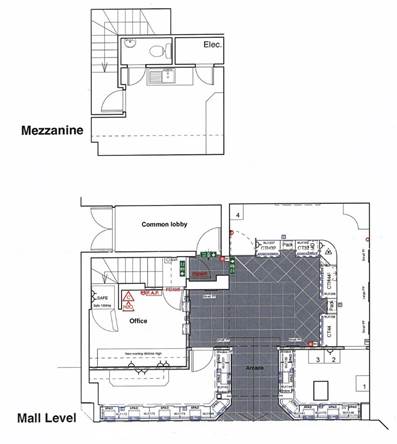

WATFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL

Respondent

Re: 18 Charter Place,

Watford,

WD17 1JY

Mr Mark Higgin FRICS FIRRV and Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

Heard on 17, 18 and 20 January and 9 March 2023

Decision Date:

Mr Jonathan Easton for the claimant, instructed by TLT LLP

Ms Rebecca Clutten for the respondent, instructed by Womble Bond Dickinson (UK) LLP

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2023

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Director of Buildings and Lands v Shun Fung Ironworks Ltd [1995] 2 AC 11

J Bibby & Sons Ltd v Merseyside County Council [1980] 39 P&CR 53

Service Welding Ltd v Tyne and Wear County Council (1979) 38 P&CR 352 (CA)

Introduction

1. The claimant, a national jewellery retailer, operated a retail store in 18 Charter Place, Watford (“the reference property”), which was acquired by the respondent for a town centre regeneration scheme under the Watford Borough Council (Land at Charter Place and High Street, Watford) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 (“the Order”). The claimant’s leasehold interest was acquired by a General Vesting Declaration on 17 November 2015, which is the valuation date.

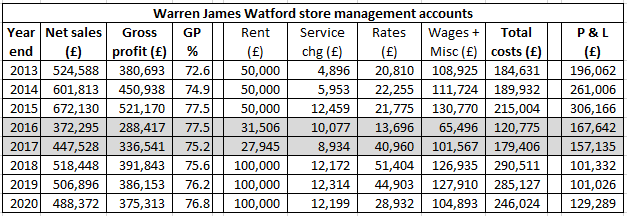

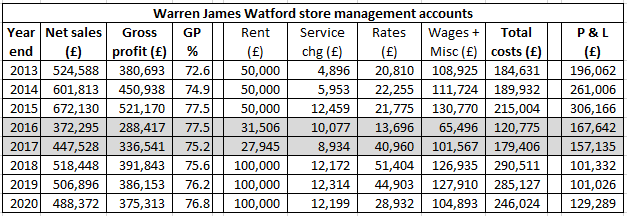

2. On 16 June 2016 the claimant relocated to 23/24 Intu Watford (“the relocation property”) from where it recommenced trading on 1 July 2016. For simplicity and consistency we will refer in this decision to ‘Intu Watford’ notwithstanding that the shopping centre was launched as the Harlequin Centre and latterly renamed Atria Watford. Compensation for relocation costs and pre-reference professional fees had been agreed. The issues remaining in dispute related to claims for temporary and permanent loss of profits, the latter arising from increased overheads in the relocation property. The respondent accepted that there was a temporary loss of profit for which compensation was due, although disputed the amount claimed, but denied that compensation was due for permanent loss of profit.

3. We made an accompanied inspection of the relocation property and the surrounding retail area on the morning of 12 January 2023. We returned to Watford on 1 February 2023 for an unaccompanied external inspection of properties in the High Street, Watford which had been referred to in expert evidence.

4. The claimant was represented by Mr Jonathan Easton and the respondent by Ms Rebecca Clutten, and we are grateful for their submissions. The hearing took place in court on 17, 18 and 20 January, with closing submissions heard by remote video link on 9 March 2023.

The facts

The claimant’s business

5. Warren James (Jewellers) Limited (‘Warren James’) was founded in 1979 by Ann Jones and John Coulter who remain sole owners and joint Managing Directors. Mr Guy Lightowler, who is the Commercial Director and joined the company 20 years ago, gave evidence as a witness of fact. His role and responsibilities encompass all commercial matters, but he is answerable to the Managing Directors and enjoys the benefit of their considerable retail experience.

6. He described the company as being extremely successful with one of the strongest balance sheets and strength of covenant of any high street retailer. He claimed that Warren James are the largest jeweller in the United Kingdom and the ‘most profitable by any measure’, but did not adduce any evidence in support of this statement.

7. He put the success of the business down to hard work and a detailed knowledge of their products, shops, managerial employees, and every high street and shopping centre of any significance. He also explained that the business centred on procedures and systems to achieve scale. In retail parlance this ‘cookie cutter’ approach involved the standardisation of shop window displays as well as commonality of products and training. The company also had a simplified management structure with no area managers. Unlike some of the competition Warren James sold the same range of products in all locations and Mr Lightowler said that these various methodologies enabled the company to trade profitably in smaller towns where stores might otherwise not be viable. At the hearing he explained that Warren James looked for locations where footfall was strong but rents were lower than the prime pitch.

The reference property (18 Charter Place)

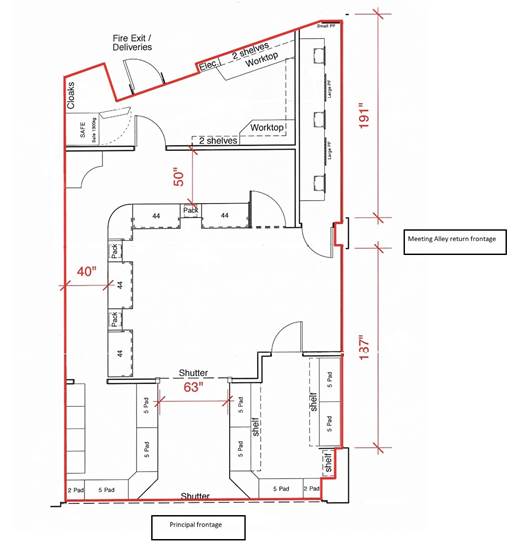

8. The reference property was a ground floor shop unit in the Charter Place shopping centre. Floor plans and photographs provided by the claimant at the hearing show that it had a glass ‘arcade’ frontage some 6.35 metres in width with the claimant's corporate signage above. The arcade is a glass corridor at right angles to the shop front about 1.6 metres wide and 2.85 metres deep, the purpose of which is to create additional window display space. The plans show that the reference property had a shutter at the inner end of the arcade and another across the full width of the frontage. It occupied a corner position and had a return frontage to Meeting Alley, the glazed parts of which extended to about 9.6 metres. Internally, most of the floorspace was used for sales although a small workroom was created by partitioning an area at the rear of the unit. A remote store room extending to about 25.5 m2 was located to the rear of the property, as were kitchen and toilet facilities shared with another retailer.

9. The respondent provided, as part of its valuation evidence, some photographs of the interior. These showed the claimant’s shop fittings in what we assume to be their usual corporate style. The walls were either plastered or panelled, the floor was carpeted, and the ceilings were either plastered or comprised of suspended acoustic tiles. Air conditioning cassettes were installed in at least part of the premises. The photographs were labelled ‘pre- possession’ and were taken in November 2015. The interior fittings appeared to be in good condition, but we have no information about their age. We were also provided with a ‘shopfit plan’ dated 8 May 2012 but it is unclear what shop fitting took place at that point although it would seem likely that having commissioned an architectural practice to produce plans, some work was undertaken.

10. Mr Lightowler explained that Warren James had been contemplating opening a shop in Watford for about 15 years before finally doing so in 2002. The company found the occupational costs of locating in Intu Watford were disproportionately high relative to the anticipated turnover. He explained that in addition to the usual overheads of rent, rates and service charges, locating in the centre would mean that the company would incur additional costs in complying with Intu’s rules relating to longer opening hours, fitout specifications, mandatory tenants’ association membership and marketing fees.

11. Ultimately the company decided to locate in Charter Place, some 42 metres from the doors to Intu Watford. The shop was in a position that Mr Lightowler described as a ‘clever pitch’ meaning that it benefitted from high footfall, but the occupational costs were said to be less than half of those for an equivalent unit in Intu Watford and the projected turnover not much different. He recounted that this assessment of profitability turned out to be correct and the shop was a ‘resounding success’.

12. The reference property was occupied under a 15 year lease from 9 September 2002 on full repairing and insuring terms. The landlord was Watford Borough Council. The lease contained no break clause and was not contracted out of Part II of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. We understand that the rent had never altered from its initial level. The occupational costs for the year ending 31 March 2015 were as follows:

b. Rates £21,775

c. Service Charge £12,459

Total £84,234

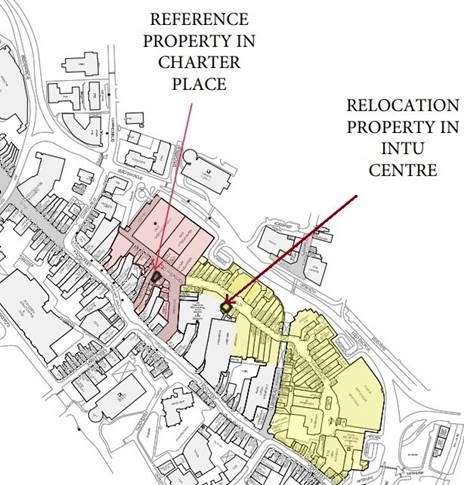

The plan below shows the layout of the reference property:

|

Retail provision in central Watford

13. To provide some context to the situation on the ground in Watford at the valuation date and afterwards, it is worth identifying the principal retail areas in the town. The High Street, which obviously predates the original Charter Place development runs on a north west/south east axis. Although it extends over a total length of 650 metres the core retail area is to be found between its junctions with Clarendon Road and King Street.

14. Charter Place in its original guise was a pedestrianised shopping centre which was completed in the mid-1970s. It was built on two levels on a site behind the eastern side of the High Street and contained a mixture of shop units, large retail stores, an indoor market hall, a YMCA and a 741 space multi-storey car park. The central walkway which contained most of the facilities including stores for Argos, Wilkinsons and Top Shop and was aligned parallel to the High Street. This area was linked to the High Street by two further pedestrian thoroughfares (Meeting Alley and Charter Way), and it was at the junction of the former and the main retail area that the reference property was located. The design of the centre was such that the access to the first-floor shops was by means of walkways a few metres in width which effectively acted as canopies for the shops located underneath. Customers of the ground floor shops such as the reference property itself were consequently afforded protection from the weather, albeit limited as the centre was not fully enclosed. Escalators and stairs which were open to the elements linked the two levels.

15. The development of Intu Watford in the early 1990s fundamentally altered the retail landscape in the town. Mr Lightowler described Watford town centre as being dominated by it. The Centre was built on a site to the south of Charter Place and east of the High Street. Largely enclosed and on two levels, it was anchored by a John Lewis department store and had mall access to the larger stores such as Marks and Spencer whose previous principal frontage was on to the High Street. It contains a total of 145 stores. At the valuation date it had three multi-story car parks providing 1433 spaces with access for shoppers directly into the malls. The only direct entry point into the centre from the High Street is at the southern end, adjacent to the junction of the High Street, Queens Road and King Street. In its original configuration access at the northern end could be gained from Charter Place on both levels, glazed doors delineating the extent of both schemes. The plan below shows the relative positions of the reference and relocation properties.

The Scheme

16. The demolition of Charter Place commenced in December 2015 and the new scheme opened in September 2018. It is now part of Intu Watford, and consists of a large store occupied by Next, approximately 15 shop units, 2 leisure units and a selection of food and beverage outlets. The original multi-storey car park has been retained and the covered market has been relocated elsewhere in the town centre.

Temporary closure

17. The claimant stopped trading from the reference property on 15 November 2015 and their interest in it was acquired on 17 November 2015. Trading is understood to have commenced from the relocation property on 1 July 2016. Following negotiations between the parties, the following heads of claim have been resolved:

a. £131,618.85 in respect of relocation, strip out of unit and general costs.

b. £11,618.10 under the head of pre-reference professional fees.

c. Statutory occupier’s loss payment in the sum of £1,760.00.

18. The temporary loss of profit suffered by the claimant as a result of relocation is not agreed.

The relocation property (23/24 Intu Watford)

19. The relocation property is a shop unit on the ground floor of Intu Watford. It is located at the northern end of the Centre, close to doors that mark the entry and egress point into what was Charter Place and is now the extension to The Atria. The relocation and reference properties were some 111.5 meters apart when following the pedestrian route through the mall and into Charter Place. The relocation property is situated on the western side of the mall between Marks and Spencer and the former BHS. Other nearby retailers include L’Occitane and Trespass. The BHS store was subsequently divided between The Entertainer, Deichmann and Flannels although the latter store only has frontage to the High Street. At the time of the relocation Next occupied a large unit on two floors opposite the relocation property but have now moved to a significantly larger store in the Atria extension.

20. The relocation property itself is arranged over ground and mezzanine levels. It has an overall frontage of 9.35 metres and is 7.24 metres deep. A common lobby is located at the left hand rear of the unit, together with a staircase to the mezzanine level. Taken as one, these elements measure approximately 4.7 metres by 2.8 metres and mean that the depth of the sales area is reduced to about 4.45 metres across about 50% of its width. The left-hand side is further encumbered by reduced headroom caused by the presence of the mezzanine floor. The claimants have used part of this lower headroom space to create an office and have utilised the understairs area for storage. The mezzanine floor contains a kitchen and staffroom, a toilet and a cupboard.

21. During our inspection we noted that the floor surface of the mall outside the property slopes with the level being some 200 mm lower at the southern end in comparison with the northern. The floor levels in the unit have been adjusted to cope with this disparity, notably with a step concealed in the window display. We also noticed that the floor in the unit slopes away downwards from the frontage.

22. Internally the floor has a polished stone tiled finish to the public areas and a granolithic surface elsewhere. The walls are either panelled or plastered. The ceilings are mostly finished with a plaster skim and have recessed lighting. The ground floor is equipped with air conditioning cassettes fed from a landlord provided central infrastructure. Mr Lightowler commented that the shopfit was amongst the most difficult that Warren James had encountered, partly because Intu had insisted on certain features including bespoke 13.5 mm glass in the shop front.

23. The claimant occupied the relocation property on a lease with a 10 year term from 20 June 2016. The lease was effectively on full repairing and insuring terms and was not contracted out of Part II of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. It contained a break clause in favour of the tenant in year 5 of the term but should the tenant activate the clause a penalty of £25,000 would be incurred. The rent comprised a basic rent and a turnover addition, this latter element became payable when 7% of the gross turnover exceeded the basic rent. The first 6 months were rent free. The occupational costs for the year ending 31 March 2018, that is the first full year of occupation, were as follows:

a. Basic rent £100,000

b. Rates £51,404

c. Service Charge £12,172

d. Merchants Association fees £1,393

Total £164,969

The plan below shows the layout of the ground and mezzanine levels of the relocation property:

Break and rent free regrant

24. The claimant exercised the break clause in the lease of the relocation property on 12 October 2020, incurring a £25,000 penalty. The lease was determined on 23 June 2021. The claimant also negotiated a further two year lease outside the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 with effect from this same date, at a £nil rent (“the 2021 Lease”). From 23 June 2021, the claimant was only liable to pay the service charge, insurance rent and business rates. The 2021 Lease contains a rolling mutual break, determinable on six weeks’ notice from 23 March 2022. Neither party exercised the break, but the 2021 Lease in any event determined on 22 June 2023.

The legal framework

25. Section 5 of the Land Compensation Act 1961 (“the 1961 Act”) sets out the six rules for assessing compensation. The claim in this case is for compensation arising from disturbance and is made under rule 6. Rule 2 is also provided to aid understanding:

“ …

(2) The value of land shall, subject as hereinafter provided, be taken to be the amount which the land if sold in the open market by a willing seller might be expected to realise:

…

(6) The provisions of rule (2) shall not affect the assessment of compensation for disturbance or any other matter not directly based on the value of land.”

26. Section 47(3) of the Land Compensation Act 1973 provides that when assessing compensation in respect of land subject to a business tenancy:

“(3) Regard must be had to—

(a) the likelihood of the continuation or renewal of the tenancy,

(b) in the case of a tenancy to which Part 2 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (security of tenure for business tenants) applies, the right of the tenant to apply for the grant of a new tenancy,

(c) the total period for which the tenancy may reasonably have been expected to continue, including after any renewal, and

(d) the terms and conditions on which a tenancy may reasonably have been expected to be renewed or continued.

27. The principle of equivalence, which requires a claimant to be fully and fairly compensated for their loss following compulsory acquisition, was reviewed in detail by Lord Nicholls in Director of Buildings and Lands v Shun Fung Ironworks Ltd [1995] 2 AC 11. He confirmed that compensation should cover disturbance loss as well as the market value of the land itself, provided that three conditions are satisfied. Firstly, there must be a causal connection between the acquisition and the loss in question. Secondly, the loss must not be too remote from the acquisition. Thirdly, the claimant must have complied with their duty to mitigate their loss. To quote Lord Nicholls (at page 6):

“The law expects those who claim compensation to behave reasonably. If a reasonable person in the position of the claimant would have taken steps to reduce the loss, and the claimant failed to do so, he cannot fairly expect to be compensated for the loss or the unreasonable part of it. Likewise if a reasonable person in the position of the claimant would not have incurred, or would not incur, the expenditure being claimed, fairness does not require that the authority should be responsible for such expenditure.”

28. We were referred to two further cases of particular relevance to this case where loss is claimed to have arisen from increased overheads in a relocation property.

29. In Service Welding Ltd v Tyne and Wear County Council (1979) 38 P&CR 352 (CA) the acquiring authority successfully appealed, by case stated, a decision of the Lands Tribunal (V G Wellings QC) that the claimants were entitled to compensation for disturbance in respect of interest charges incurred in financing construction of a new factory into which they relocated. Bridge LJ (with whom Megaw and Templeman LJJ agreed) stated at [357]:

“What the authorities (to which I need not refer in detail) very clearly establish, however, is that when an occupier, whether residential or business, does, in consequence of disturbance, rehouse himself in alternative accommodation, prima facie he is not entitled to recover, by way of compensation for disturbance or otherwise, any part of the purchase price that he pays for the alternative accommodation to which he removes, whether that accommodation is better or worse than, or equivalent to, the property from which he is being evicted. The reason for that is that there is a presumption in law—albeit a rebuttable presumption—that the purchase price paid for the new premises is something for which the claimant has received value for money. If he has made a good bargain and acquired premises that have a value in excess of what he has paid for them, that is not something for which the acquiring authority is entitled to any credit. If the claimant has made a bad bargain and has paid a great deal more for the new premises to which he is moving than they are really worth, that is not something for which the acquiring authority can properly be charged.”

30. In J Bibby & Sons Ltd v Merseyside County Council [1980] 39 P&CR 53 the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal of the claimants against the decision of the Lands Tribunal (W H Rees FRICS) that they were not entitled to compensation for increased operating costs resulting from relocating to an office building of five floors, when only two were required for occupation. However, Brandon LJ (with whom Megaw and Eveleigh LJJ agreed) considered at page 60 instances when it would, in principle, be right to award compensation in respect of extra operating costs, the presumption of value for money having been rebutted:

“It seems to me that it would be right to award compensation in respect of such items if it were shown, first, that the claimant, as a result of the compulsory purchase, had no alternative but to incur the increased operating costs concerned and, secondly, that he had no benefit as a result of the extra operating costs that would have made incurring them worthwhile.”

The claim

31. The claimant adduced expert accounting evidence to support a claim for temporary loss of profit at £287,552 and permanent loss of profit at £1,386,925. The respondent’s accounting expert assessed the claim for temporary loss of profit at £150,093 and the claim for permanent loss at nil.

32. It was the respondent’s case that the claimant had received value for money in taking on the relocation premises with higher overhead costs, because there were benefits in that property which made incurring them worthwhile. Moreover, the claimant had not discharged the burden of proof upon it that no alternative relocation properties were available which would not have required higher overhead costs to be incurred.

33. Both parties adduced expert valuation evidence to assess, first, whether the claimant had paid market value for the relocation property and, second, whether there may have been less expensive suitable alternative properties available at the time of relocation which the claimant could have taken.

34. We first review the accounting evidence to determine the temporary loss of profit suffered by the claimant. We then review the valuation evidence to determine whether any permanent loss of profit is eligible for compensation in the light of the guidance in Service Welding and Bibby. Finally we return to the accounting evidence, to determine the permanent loss of profit.

Accounting evidence

35. Mr Easton called Mr Gareth Woodward of BTG Advisory in Manchester to provide expert accounting evidence. Mr Woodward qualified as a chartered accountant in 1978 and since 1990 has worked full time as a forensic accountant, including the provision of expert evidence.

36. Ms Clutten called Mr David Epstein to give expert accounting evidence. Mr Epstein is a consultant in the forensic accounting services department of Moore Kingston Smith in London, and has over 30 years of experience in forensic accounting and dispute resolution.

37. The two experts agreed that their findings had been limited due to a lack of disclosure by the claimant of comparator stores data, and the general lack of detailed profit and loss accounts for individual stores. The lack of disclosure resulted from a failure to reach a consensus with the respondent on commercial confidentiality. The claimant had made available audited accounts for the company as a whole, and a simple set of annual management accounts for the Watford store covering the accounting years ending 2013 to 2020. Whilst some criticism was made by Mr Epstein of the management accounts, figures from those accounts were used by both experts in their assessments of loss, so we set them out below for clarity. The two years of partial trading caused by relocation are highlighted.

Assessment of temporary loss of profit

38. The starting point for this assessment is to estimate what profit would have been achieved in the no-scheme world at the reference property in the years when trading was affected by acquisition and relocation, so that a comparison can be made with the actual profit achieved in those years. The comparison can be made either on a net profit basis, or on a gross profit basis with adjustment for different overheads as necessary. Mr Woodward adopted the net profit approach and Mr Epstein the gross profit approach.

39. Mr Woodward assessed the no-scheme world net profit using the financial results achieved by the claimant at the reference property in the year ending 31 March 2015 (“YE 2015”), the last full year of trading before the acquisition and relocation. As the figures above show, annual net sales amounted to £672,130, of which 77.54% was stated to be gross profit (sales less cost of sales) of £521,170. From the gross profit £215,004 was deducted for overheads to account for rent (£50,000), service charge (12,459), rates (£21,775), wages (£99,987) and miscellaneous items (£30,783), leaving a net profit of £306,166. In accounting terms this is described as EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation).

40. Trade in YE 2016 was affected by cessation of business in the reference property on 15 November 2015. Trade did not recommence in the relocation property until 1 July 2016, so YE 2017 was also affected. To calculate the claim for loss of profit in the two affected years Mr Woodward assumed that in the no-scheme world profits of at least £306,166 (as in YE 2015) would have been achieved in each affected year. The actual profit for each year was shown in the management accounts at £167,642 and £157,135 respectively so the claim for temporary loss of profit was assessed as set out below, although we note that Mr Woodward’s assessment of £287,522 differs by £33 from that shown below:

YE 2016 loss: £306,166 - £167,642 = £138,524

YE 2017 loss: £306,166 - £157,135 = £149,031

Total temporary loss: £287,555

41. For the respondent, Mr Epstein was concerned that the management accounts provided by the claimant in support of the claim were potentially unreliable since auditors had stated in a letter only that the information in the claim “agreed materially” with the accounting records. Moreover, the data was not supported by any sworn witness statement. He had a particular concern that the gross profit percentages of 77.54% for YE 2015 and 77.47% for YE 2016 were very different from those in the claimant’s audited accounts for the same years at 49.78% and 47.67% respectively. However, it had been explained to him that the audited accounts differed because deductions for wages and store occupancy costs had been made from the product margin on sales.

42. Mr Epstein adopted Mr Henderson’s view that money spent on overheads in the relocation property would have represented value for money, so his approach to assessing temporary loss was based on gross profit. From the management accounts he took actual net sales achieved in the affected years and compared these with the level of sales predicted for those years in the no-scheme world. To assist him in predicting sales in the no-scheme world Mr Epstein analysed the claimant’s company wide data on net sales, and the number of stores fully operational in each year, to assess the average sales per store from YE 2013 through to YE 2020, together with the year on year percentage change. He compared this with the actual sales and year on year change in Watford, as set out below:

|

Year end |

Watford net sales (£) |

% change |

National number of stores |

Average sales per store (£) |

% change |

|

2013 |

524,588 |

|

115 |

468,265 |

|

|

2014 |

601,813 |

+14.7 |

117 |

571,516 |

+21.8 |

|

2015 |

672,130 |

+11.7 |

128 |

628,961 |

+10.1 |

|

2016 |

372,295 |

-44.6 |

154 |

555,669 |

-11.6 |

|

2017 |

447,528 |

+20.2 |

184 |

552,998 |

-0.5 |

|

2018 |

518,448 |

+15.8 |

210 |

515,504 |

-6.8 |

|

2019 |

506,896 |

-2.2 |

222 |

469,706 |

-8.9 |

|

2020 |

488,372 |

-3.6 |

220 |

436,699 |

-7.0 |

43. Mr Epstein observed that sales for YE 2015 were the highest of any year, both at the property and across all stores, and that average sales per store fell year on year thereafter. Monthly sales data supplied for the reference property showed that sales for April to September 2015 were 5% below the same period in 2014. Although sales in October and half of November 2015, i.e. the six weeks leading up to vacation of the property, were significantly higher than for the same period in the previous year, he considered that this would be explained by the pre-vacation clearance sale. Mr Epstein therefore concluded that in the no-scheme world sales at the reference property would have fallen after YE 2015, which caused him to avoid using the YE 2015 sales as a benchmark for future years.

44. In the absence of sales data from a basket of comparator stores, Mr Epstein looked at the average growth in sales across all stores between YE 2013 and YE 2015, which was 34.0%, and compared it with the growth in sales at the reference property over the same period, at 28.1%. He concluded that sales growth at the reference property was either broadly equivalent to (YE 2015) or below (YE 2014) that of an average store, so that using growth figures for an average store would not understate estimated sales in the no-scheme world. He therefore made a forecast of what sales would have been in the no-scheme world after YE 2015 by applying the year on year percentage change of an average store to the YE 2015 sales figures. These results were then compared with sales actually achieved in those years, to assess the extent of sales lost over the years affected by relocation, revealing that by YE 2019 post-relocation sales were better than the forecast.

45. For the three years when sales were lost, Mr Epstein assessed the loss of gross profit by applying a percentage of 65% to the lost sales figures. He declined to rely on the figure of 77% shown in the Watford store management accounts, since this was not substantiated by audited evidence and was significantly higher than any gross profit percentage that he had observed in the branch management accounts of other retail jewellers. His figure of 65% was taken from the top of the range of gross profit figures (55% to 65%) which he had observed in such accounts. He therefore assessed the loss of gross profit at £258,336, as shown below:

|

Year end |

Actual sales (£) |

Year-on-year variation of average store |

Forecast of sales (£) |

Lost sales (£) |

Lost gross profit at 65% (£) |

|

2015 |

672,130 |

|

|

|

|

|

2016 |

372,295 |

-11.65% |

593,827 |

221,532 |

143,996 |

|

2017 |

447,528 |

-0.48% |

590,976 |

143,448 |

93,241 |

|

2018 |

518,448 |

-6.78% |

550,908 |

32,460 |

21,099 |

|

2019 |

506,896 |

-8.88% |

501,988 |

- |

|

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

258,336 |

46. Having established a figure for loss of gross profit over the three affected trading years, Mr Epstein made a deduction for costs saved during the period when the business was closed for trading between 15 November 2015 and 1 July 2016. For the majority of that period until the new lease took effect on 20 June 2016 (218 days), no property overheads or wages were incurred. The saving was assessed at £103,937, being a proportional amount (218/366) of the annual costs in the reference property for rent (£50,000), service charge (£12,500), business rates (£22,000) and wages (£90,000). For the further 11 day period until trading recommenced, Mr Epstein assessed the costs saved at £ 4,306, being a proportional amount (11/366) of rent (£50,000), net additional service charge in reference property (£3,282) and wages (£90,000). The saving on rent occurred because of the six month rent free period in the relocation property, by comparison with the no-scheme world situation in the reference property. The total of costs saved therefore amounted to £108,243 (£103,937 plus £4,306).

47. Mr Epstein’s assessment of the claim for temporary loss of profits was:

Loss of gross profit: £258,336

Less costs saved: £108,243

Temporary loss of profits: £150,093

Discussion of temporary loss of profit

48. The experts agree that a temporary loss of profit was suffered by the claimant as a result of the relocation and interruption to trading. We consider that assessment of the temporary loss should be confined to the two partial trading years of YE 2016 and YE 2017. The figures in the management accounts show clearly the reduced sales and gross profit figures in those years, together with reduced overheads incurred as a result of partial closure in each year. The six month rent free period in the relocation property, from 20 June to 20 December 2016, contributed helpfully to the reduced overheads in YE 2017 and mitigated the loss suffered to some extent. We understand that the itemised disturbance costs incurred by the actual relocation and fitting out of the relocation property have been agreed separately at £131,618.85.

49. In order to assess the profit which would have been generated in the no-scheme world at the reference property, for a limited period of temporary loss, we prefer Mr Woodward’s net profit approach, which is grounded in the management accounts available to us for the Watford store. Mr Epstein’s gross profit approach has merit, but we consider that a hypothesis based on sales trends taken from the notional performance of a national average store is too far removed from the reality of trade in Watford to be relied on, particularly as national store numbers rose from 128 to 154 and then to 184 over the two year period. However, the weakness of Mr Woodward’s approach was that he assumed the net profit of £306,166, achieved in YE 2015 when net sales were at their highest level for at least three years, would have been matched in the following two years in the no scheme world. We find this to be unrealistic given the volatility of the retail sector. Mr Lightowler told us that budgets are not produced for individual stores but, even if they were, we consider it would be a bold business that assumed a continuation of profits from a high point. Ms Clutten submitted that past performance has not been an accurate or reliable guide to future performance of the claimant’s business, at national or store level, and this is not surprising, but we must use what we have available. We adopt a more cautious assumption than Mr Woodward for the two affected years, basing our assessment of performance in the no-scheme world on the average net profit achieved in the three years prior to relocation, which is £254,411. Our assessment of the temporary loss on a net profit basis is therefore:

YE 2016 loss: £254,411 - £167,642 = £86,769

YE 2017 loss: £254,411 - £157,135 = £97,276

Determination of temporary loss: £184,045

Valuation expert evidence

50. Mr Easton called Mrs Kate Okell MRICS to give expert valuation evidence on behalf of the claimant. Mrs Okell has over 15 years' experience in compulsory purchase surveying and is currently a partner at Axis Property Consultancy LLP, based in Manchester. She is a member of the RICS Expert Working Group on Compulsory Purchase and a member of the Compulsory Purchase Association.

51. Ms Clutten called Mr Mark Henderson MRICS IRRV(Hons) as valuation expert for the respondent. He is an International Partner at Cushman & Wakefield. He has been in practice for over 45 years, the first 6 years of which was with the District Valuer’s Office and the remainder with DTZ who merged with Cushman & Wakefield in September 2015. During his career he has specialised in the field of statutory valuation, including compulsory purchase and compensation.

52. Mr Henderson confirmed that Cushman & Wakefield had been advising on this case since July 2013 and that overall responsibility for the compulsory purchase elements of the instruction had rested with him throughout this period.

Value for money?

53. We have already alluded to the concept of ‘value for money’ in paragraph 29 above and this concept is central to a claim for permanent loss. Mrs Okell described the respondent's position as being ‘that the claimant is deemed to have obtained value for money for the relocation property and therefore the increased occupational costs are not to be taken into account in the assessment of compensation’. There is a presumption that when alternative premises are taken, either freehold or by lease, the claimant obtains value for money in respect to the purchase price or rent payable and suffers no continuing financial loss once any short term disturbance claim has been accounted for. However, this presumption is rebuttable, and we have already set out above the comments of Brandon LJ in Bibby in that connection.

54. In determining whether the claimant should be compensated for permanent loss of profit arising from the additional overheads incurred in the relocation property we must first determine if there were any suitable alternatives available and therefore any possibility of not incurring the increased operating costs associated with it. If there were no alternatives to the property to which the claimant ultimately relocated, we must determine whether there is any benefit to be derived from the extra costs associated with it. If not, then the claimant should be compensated.

Relocation options

56. Mrs Okell summarised details of alternative properties considered within the Intu Centre, together with some footfall data provided to the claimant by the Pragma consultancy, in a table appended to her report and the salient detail is reproduced below:

|

Comparison of Alternative Units within Intu Watford | ||||

|

Address |

Approx. Size |

Occupational Costs |

Location |

Weekly Footfall (as assessed by Pragma) |

|

18 Charter Place (The reference property) |

758 sq. ft |

Rent: £50,000 S/C: c.£12,459 Rates: c.£21,775 Total: £84,234 (for Y/E 31.03.15) |

Ground Floor Unit Corner Location |

43,000 at Meeting Alley 48,000 at The Mall |

|

19 (Formerly Café L’antico) |

869 sq. ft |

Rent: £40k pa base S/C: c.£5,629 Rates Payable: c.£14,280 Merchants Association: £819 Insurance: £145 Total: £60,873 |

Ground Floor Unit on Queens Road |

19,000 (c.40% of The Mall’s footfall) |

|

142a (Formerly Carrera Jeans) |

620 sq. ft |

Rent: £82,500 pa base Service Charge: £7,523 Rates Payable: £29,580 Merchants Association: £995 Insurance: £102 Total: £120,700 |

Upper Floor Unit within Intu Shopping Centre |

41,000 (c.85.5% of The Mall’s footfall) |

|

31a (Formerly Blott) |

906 sq. ft (taken from VOA assessment) |

Not known |

Ground Floor Unit within Intu Shopping Centre |

Not known but close to the reference property so likely to be similar |

|

27 or 27a (Former Rush Hair) |

1,343-1,674 sq. ft (taken from VOA assessment)

|

Not known |

Ground Floor adjacent to eastern entrance. Closest in proximity to existing unit. Would have been impacted by building works. |

Not known but close to the reference property so likely to be similar |

|

49 |

2,046 sq. ft |

Rent: £165,000 pa base Service Charge: £23,209 Rates Payable: £83,868 Merchants Association: £3,458 Insurance: £329 Total: £275,864 |

Ground Floor Unit within Intu Shopping Centre |

Not known |

|

23/24 (The relocation property) |

775 sq. ft |

Rent: £100,000 Service Charge: £12,172 Rates: £51,404 Merchants Association: Not known Insurance: Not known Total: £163,576 Plus Merchants Association & Insurance |

Ground Floor Unit within Intu Shopping Centre |

Not known but close to the reference property so likely to be similar |

57. No. 19 (former Café L’Antico) is a ground floor unit located on Queens Road and although it forms part of the Intu Watford centre it is outside the enclosed part of the scheme. Mrs Okell noted that this property had about 60% lower footfall than the reference property due to an inferior position in what she described as a ‘service business’ location. The unit was also larger than the reference property but had a narrower frontage with less display space. At the time the research was being conducted the unit was still occupied by another party although the landlord had indicated that possession could be obtained.

58. The former Carrera Shoes at No.142a was on the upper floor of the centre and had footfall which was some 95% of that at the reference property when measured at the Meeting Alley frontage. Mrs Okell noted Pragma’s comments that footfall was ‘fairly low during the week but high at the weekend’. She considered the unit to be less prominent due to poor lighting, low ceiling and presence of two structural pillars which obscured the frontage. It was a smaller unit than the reference property with a narrow frontage and less display space. The occupational costs were approximately 30% higher. Again, this unit was occupied but Intu had advised that they could potentially secure possession.

59. Mrs Okell said that No.31a had been suggested as a relocation possibility by the claimant in a letter to Intu dated 28 July 2015, but Intu responded stating that the unit was already under offer at a rent higher than their estimated rental value.

60. Similarly, the former Rush Hair unit (No.27) was put forward by the claimant on 13 August 2014. Mrs Okell noted that the proposal was on the basis of reducing the size of the unit to keep the rent low, but Intu responded to say that reducing rent was not an option. Although the unit was again raised by the claimant in July 2015, nothing further was achieved as Intu had the unit under offer at a rent higher than their estimate of rental value.

61. No.49 was suggested by the claimant in a letter of 28 July 2015 and an offer made. The claimant indicated that they wished to reduce the unit in size to 800 sq. ft, a similar reduction in floorspace having been achieved to the adjacent unit which was occupied by Thomas Sabo. Intu replied two days later stating that the unit was under offer at rent higher than their estimate of rental value.

62. We note that Mr Lightowler had appended projections of turnover and profitability for units 142a, 31a and 19 to his witness statement. He anticipated sales 35%, 25% and 50% lower at the three locations respectively and estimated that profitability would be reduced by 89%, 82.5% and 98.3% when compared to the average of the three previous years.

63. Mr Henderson acknowledged in his report that the claimant shortlist included unit 31A, unit 27, unit 142A and unit 49. He explained that the former Café L’Antico at 19 Queens Road had also been offered by Intu, as had unit 109 and unit 162, but the latter two were considered unsuitable by the claimant. In his report Mr Henderson did not provide his views on the suitability of any of these units but did note that Intu had “given its blessing” to the claimant to instruct Pragma to advise on options for relocation. In cross examination he conceded that the available alternatives in Intu Watford were not suitable for the claimant.

64. Pragma undertook a footfall study at Charter Place and outside Nos 19 and 142a between 10 and 13 September 2015 and additionally analysed footfall data supplied by Intu. Mr Henderson said that Pragma had initially stated that their report would include a range of flow computations and profit and loss estimates to be based on data supplied by the claimant. In the event the data was not forthcoming and the report therefore focussed on footfall and a review of the competition. The report concluded that footfall in the mall directly outside the reference property was 48,000 per week and that the subsidiary frontage in Meeting Alley the weekly figure was 43,000. The corresponding figures for unit 19 and unit 142A were 19,000 and 41,000 respectively. Mr Henderson explained that Intu monitored footfall levels in the centre using a camera system. This showed that at the time that Pragma undertook their research footfall outside the lower mall entrance to Marks & Spencer, very close to the relocation property was 68,000, some 41.6% higher than at the reference property.

65. Mr Henderson noted that Pragma concluded that neither of these two relocation options were suitable since they were less prominent and had lower footfall. Mr Henderson observed that Pragma thought that the claimant should concentrate on the potential to relocate to the ground floor of Intu Watford as it had the highest footfall. They commented that there was an additional potential for the claimant to locate on the High Street where a higher proportion of their target customers were likely to be encountered, footfall was expected to be stronger and competition weaker.

66. Mr Henderson said he was surprised that the relocation property was not included in the report. E-mail correspondence between the agents for the claimant and Intu was appended to Mrs Okell’s report and this clearly showed that discussion about the relocation property commenced in August 2015 and that the Pragma Report was delivered in draft on 18 November 2015. Mrs Okell noted that Intu’s rental expectations for the relocation property were not communicated until after Pragma had started work. The relocation and reference properties were close to one another in any case.

67. Mrs Okell thought that the difference in footfall could be explained by the significant number of vacant units and lack of proactive management in Charter Place. Mrs Okell said that Charter Place was arguably “in the shadow of the scheme” and it was reasonable to assume that Charter Place footfall had been adversely affected as a result. She concluded that footfall would have been higher prior to the scheme and the difference between the two locations would not have been significant. No other evidence was adduced to support this opinion. We have already described the retail facilities in Watford and although Intu Watford is regarded as the primary retail location in the town it is by no means the only location a retailer looking for space would consider. Mr Henderson said he had not been provided with any evidence as to whether there were any suitable location options outside Intu Watford. Mrs Okell addressed this point in her supplemental report and confirmed that although consideration had been given to units outside Intu Watford, no suitable units had been found.

68. She did not reveal which units had been considered and it was not clear whether she knew the locations. Nevertheless, she had conducted an exercise using “CoStar” which she described as ‘industry recognised software’, to research retail lettings which had taken place between 1 January 2015 and 1 January 2017.

69. The search turned up 15 properties, four of which related to shops in Intu Watford which Mrs Okell excluded as the claimant was actively considering units in the Centre. Only five of the remainder related to shop units in the town centre. Two of these were located in the Parade, an area of the town described by Mrs Okell as tertiary. Two further properties were in Market Street which runs perpendicular to the High Street and contained a mixture of local independent traders and service-style businesses. Mrs Okell thought that Market Street could not be compared with Charter Place as a retail location. The final property was in Beechen Grove and thus was outside the recognised retail core. It was situated beneath a block of flats and lacked retail adjacencies. Mrs Okell recognised that the search was not evidence of the claimant’s search for units outside Intu Watford, but she considered that it provided a good indication of what was available at the time the claimant was seeking a relocation property. She went on to conclude that there were no suitable alternative premises for the claimant to relocate to. We have some concerns about the efficacy of this exercise, as the database will only be as good as the data inputted. Mrs. Okell admitted as much at the hearing and also acknowledged that there might be properties that were available ‘off market’. However, if that were the case, we would have expected Mr. Appleby to be aware of them and to have brought them to the attention of Mr Lightowler.

70. By the end of November 2022, when Mrs Okell and Mr Henderson were compiling their preliminary statement of agreed facts and issues, they had determined that a further five properties had been available for consideration by the claimant. Details appended to the statement showed that CoStar had once again been used as the means of searching.

71. The first of these was 52 High Street Watford which was located on the western side of the High Street close to the junction with Clarendon Road. Arranged over basement and ground floor it extended to 2,315 sq.ft, some three times the size of the reference property. After being on the market for three months it let on a term of a year at £105,000 per annum. The rate liability was £47,081 per annum. This property was in a part of the High Street that was affected by the redevelopment of both Charter Place and an immediately adjoining building.

72. The second option was 68 High Street, a ground and first floor retail unit forming part of a block built in 1931. The block is arranged over four floors and has distinctive black timber and cream plaster elevations. There was some conjecture at the hearing over the planning status of the building and specifically whether it was listed although nothing was provided in evidence to enlighten us. The property offered 1,680 sq.ft of floor space and was let on a three-year term from October 2015 at £50,000 per annum. According to the CoStar details no rent free period was granted. In common with 52 High Street this property was situated directly opposite Charter Place and would, to some extent, have been affected by the redevelopment and the associated street works.

73. The third option was 122 High Street, a modern unit at the southern end of the street and near to the junction with King Street. The CoStar details described it as having a floor area of 1,700 sq.ft on the ground floor only but when we inspected we found that Waterstones, who were ultimately the occupier, were trading on two floors. It was unclear whether the lease covered both floors but that would seem to be a reasonable assumption in the circumstances. We found the letting details difficult to reconcile. Despite being on the market for 11 months it eventually let on a 10 year term at a headline rent of £110,000 per annum against an asking rent of £75,000 per annum. Nine months rent free was conceded which was said to have reduced the net effective rent to £99,351 per annum.

74. The fourth shop was 140 a High Street which was at the southern extremity of the High Street and therefore in a secondary position. In our view it was not a suitable option for relocation and can be excluded from consideration.

75. The final possibility was confusingly listed as 1 Clarendon Road but in reality, was round the corner at 5 Parade. This property was a conventional shop unit on two floors although the sales area only extended as far as the ground floor. According to the CoStar particulars the floor area amounted to 2,739 sq.ft. and the property was let to Greggs for a 10 year term from August 2015. The rent achieved was £55,000 per annum with a six month rent free period. The asking rent had been £57,500 per annum. The property is adjacent to Pret a Manger, Shoe Zone and Ladbrokes. Starbucks are situated on the opposite side of Parade which itself is pedestrianised.

The deal for the lease of the relocation property

76. Mrs Okell said that the relocation property became available very late in the CPO process. Mr Appleby identified the unit as a possibility in August 2015 and discussions about it continued through September. It was made clear by Mr Sanderson, of Intu’s advisors CWM Retail Property Advisors LLP, that the unit was already under offer but there was some doubt that the transaction might not complete. Mr Sanderson also said that the unit was not being openly marketed but there was additional interest from MenKind.

77. Mrs Okell’s report contained copies of emails and correspondence between Mr Lightowler, Mr Appleby and Mr Sanderson in relation to the various properties under consideration. In an email of 16 October 2015 Mr Sanderson set out in the briefest of terms his client’s requirements in relation to the proposed occupation. These were for a base rent of £100,000 per annum, a rent-free period of 6 months and a tenant only break clause with a penalty of 50% of the incentive, namely £25,000. In an email of 19 October Mr Appleby asked for heads of terms. On the same day Mr Sanderson reported to various individuals at Intu (a copy of the email was appended to Mr Henderson’s report) that he had been able to ‘improve the terms further’. Specifically, he said that:

‘ in terms of the deal we are now a decent way ahead of your ERV1 and based on the previous analysis sheet this shows just less than £240 ZA headline, which because we have conceded only six months rent free and penalised the break with a three month penalty, we should be able to treat as ‘net’ as well.’

Note 1: Estimated rental value

78. For his part, notwithstanding that he had attached this correspondence to his report, Mr Henderson said that having been provided with Intu’s tenancy schedules and transactions relating to the time of the letting he was satisfied that the lease terms were ‘at a market level’ and in line with levels established through other lettings of comparable units in the centre.

79. The claimant entered into an agreement for lease on the terms stated above on 24 March 2016 and on 12 October 2020 exercised the five year break clause by serving the requisite notice and paying a penalty of £25,000. This brought the lease to an end with effect from 23 June 2021. The claimant negotiated with the landlord for a new two year lease outside Part II of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 and this lease took effect from 23 June 2021 as well. The lease was at nil rent and the only outgoings were the service charge, insurance rent and business rates. This lease contained a rolling mutual break with effect from 23 March 2022 on six weeks’ notice.

Comparison of reference and relocation properties

80. Both Mrs Okell and Mr Henderson included a tabular comparison of the attributes of the two properties in their expert reports. The factors they considered can broadly be divided between the characteristics of the properties themselves and the physical environment in which they are located. As far as the properties are concerned, the configurations differed markedly. Mrs Okell noted that the reference property was set out over a single floor while the relocation property, which she considered less convenient, had two floors, the upper of which had restricted headroom in part. She also noted the that the relocation property had less window display space as it lacked a return frontage and part of the primary frontage was compromised by the presence of the bulkhead for the mezzanine floor. Mr Henderson did not initially comment on the configuration of the unit other than noting Mr Lightowler’s conclusion that the layout of the unit was poorer than the reference property. He did however state that in his view the relocation property had a longer frontage that was better lit and occupied a more prominent position. In his supplemental report he refuted Mrs Okell’s assertion that the relocation property was materially less convenient, noting that the mezzanine level amounted to only 12.3 m2 and expressed an opinion that it was better configured by virtue of a wider frontage and a larger Zone A area. Mr Henderson’s calculations of the respective floor areas for the reference and relocation properties can be summarised as follows:

|

Accommodation |

Reference Property |

Relocation Property |

|

GF Zone A (m2) |

41.0 |

51.4 |

|

GF Zone B (m2) |

29.4 (incl. ancillaries) |

7.3 |

|

Mezzanine (m2) |

- |

12.3 |

|

Total Size (m2) |

70.8 |

70.4 |

81. Mrs Okell thought that the two units were broadly similar in terms of fit out. This was disputed by Mr Henderson who identified the fit out at the reference property as being a third of the way through its life whilst that in the relocation property was brand new.

82. Turning to the question of location Mrs Okell acknowledged that the position of the relocation was superior, describing it as a prime trading location in comparison to the reference property which she thought to be fringe of prime. Confusingly she also said the properties were in very similar trading locations, presumably inferring that there was not much difference between the two. She conceded that the shopping environment in Charter Place was less attractive than Intu Watford due to its age and design.

83. Mr Henderson focussed on retail adjacencies noting that with regard to the main frontage the reference property was located next to vacant units whilst the immediate neighbour on the return frontage was a small mobile phone shop. Large stores occupied by Argos and Wilko were situated on the opposite side of the main thoroughfare.

84. The relocation property on the other hand was within Intu Watford and benefited from a ground floor location immediately adjoining BHS, very close to M&S and opposite Next. He considered that these major retail occupiers attracted high levels of footfall which would draw customers to the area in which Warren James had relocated. He noted that Pragma had identified the area between Next and M&S as the ‘prime zone’ and recommended that Warren James should relocate to that part of the mall.

85. Mr. Henderson also said that the BHS store had closed in August 2016, a little over a month after Warren James had commenced trading in Intu Watford. He speculated that the loss of BHS, the closure of the doors to Charter Place, and the creation of an access way to the Charter Place car park had affected footfall until the Intu Watford extension had opened in September 2018. An important ‘cut through’ between the mall and the High Street was also lost when BHS closed. The BHS store was subsequently redeveloped but it was not until spring of 2019, nearly three years later, that the store was split up and the resultant units that faced on to the mall were occupied by Deichmann (a discount shoe retailer) and The Entertainer (a toy shop). The closure of BHS was unrelated to the scheme.

86. Mr Henderson conceded that there were a greater number of jewellery competitors in Intu Watford than elsewhere in the town centre but thought that shoppers wanting to compare the offerings of the various retailers would be attracted to the vicinity. He noted that the reference property was only 42 metres from the doors of Intu Watford and was itself near to competitors. He went on to say that most of the competitors were on the first floor of Intu Watford or at the southern end of the mall. This statement appeared to contradict his earlier comment about the proximity of the competition. Mr Henderson also emphasised that Intu Watford was covered and protected from the elements whilst shops in Charter Place did have canopies over their frontages but were subject to the vagaries of the weather.

87. As far as the terms of occupation were concerned Mrs Okell acknowledged that the lease at the relocation property had a shorter term but benefitted from a tenant’s break clause. It also had a turnover ‘top up’ provision and contained an obligation to join the Merchant’s Association which required an annual membership fee. The opening hours were also more onerous than those stipulated at Charter Place.

88. Whilst Mrs Okell acknowledged that not all benefits reflected in the additional rent would necessarily result in higher turnover, for example better and more convenient staff welfare facilities would not, she maintained that any benefit that the claimant had derived would not render the extra occupational costs incurred at the relocation property worthwhile.

89. Summarising the evidence for the claimant, Mr Easton submitted that although there were differences between the reference property and the relocation property, the benefits had been overstated by the respondent and would not justify a reasonable, knowledgeable and successful retailer such as the claimant incurring them. The claimant had therefore not obtained value for money.

90. In contrast Ms Clutten submitted that we should adopt Mr Henderson’s opinion that the additional occupational costs including rent, rates, and service charge were value for money in line with the presumption confirmed in Bibby. Furthermore, the claimant had failed to provide any evidence to rebut the presumption and the additional costs should not therefore be compensatable.

Rating assessments and reliefs

91. Mr. Henderson carried out a comparison of the rating assessments relating to both the reference and the relocation properties. In relation to the 2010 rating list he noted that the compiled list assessment for the reference property was rateable value £47,250 in comparison to the relocation property which began the 2010 rating list at rateable value £111,000 and was subsequently reduced to rateable value £103,000 with effect from 11 January 2016.

92. Regarding the 2017 rating list, which has a valuation date of 1 April 2015, the relocation property was initially assessed at rateable value £75,000 but altered to rateable value £69,500 with effect from the compiled list date to take account of the building works in Charter Place. This concession was removed in December 2020 thereby reinstating the original rateable value of £75,000 with effect from first September 2018.

93. Mr. Henderson explained that the Valuation Officer (‘VO’), who is responsible for the maintenance of the rating list and assessing each property within it, is an independent valuer and uses evidence of net effective open market rental values to arrive at his opinion of value. He concluded that the rateable value would therefore reflect the Valuation Officer’s opinion of the merits of the two properties, and this suggested that he considered the reference property was inferior to the relocation property, as reflected in its net effective rental value.

94. At the hearing we asked Mr Henderson why there was a disparity between the 2017 rating list assessment of rateable value £75,000 and the agreed headline rent of £100,000 per annum bearing in mind that the latter was agreed only six months after the valuation date for the 2017 rating list. Mr Henderson considered that the VO were often very conservative in their approach and this was evident in the level of assessment.

No-scheme world lease and rent assumptions

95. Neither Mrs Okell nor Mr Henderson had devoted much attention to the question of what would have happened to the rent payable at the reference property in the no scheme world had it been the subject of a lease renewal in 2017. We viewed this as an important consideration and asked them both to comment on it.

96. In his first report Mr Henderson said that the passing rent, notwithstanding that it was effective from 2012, reflected the plans to redevelop Charter Place and a lack of active asset management. Rent reviews had not been implemented and there were a number of empty units. When we asked for his opinion on the likely terms of a lease renewal in the no-scheme world he considered that a public body such as Watford would have required a longer term of 10 years, with no rent free period and no break, as per the original lease. He agreed that the reference property had been a ‘clever’ choice, as described by Mr Lightowler, because it was parasitic on the adjacent Intu Watford whilst benefitting from a lower Zone A rent.

97. Mrs Okell considered that whilst the renewal would have provided an opportunity for rental uplift, it was unlikely to have been significant. She disagreed with Mr Henderson about lease length and considered that a shorter lease of six years with a three year break clause would have been more likely.

98. Neither Mrs Okell nor Mr Henderson provided any details or analysis in relation to other shops in Charter Place so we have no means of judging whether the terms under which the reference property was occupied were particularly advantageous. It is therefore impossible to come to any judgement about whether the claimant’s level of profit was unusually good as a result of beneficial lease terms, or eminently achievable by another similar business.

Discussion

Relocation options

99. Mr Henderson conceded in cross examination that available alternative properties within Intu Watford were not suitable for the claimant, so we need say nothing further in this regard. We therefore turn to relocation options outside Intu Watford.

100. We take the view that only four of the five properties identified by the parties in November 2022 are worthy of consideration in this context as the property located in the Lower High Street cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be considered comparable with Charter Place. The same can be said of the properties, other than those in Intu Watford, that were the outcome of Mrs Okell’s original search.

101. There are several metrics which can be utilised to assist in reaching a judgement as to whether any of these properties were suitable to the extent that they provided equivalence for the claimant’s business. The first of these is occupational costs. Nos. 52 and 122 High Street had the highest costs at £152,081 and £144,264 per annum respectively. No service charge details were provided. No.5 Parade is closely aligned with the reference property. The costs were stated as totaling £89,826 per annum including the service charge. No meaningful comparison is possible with No.68 as we have only been provided with the rent payable of £50,000 per annum.

102. The second is location. We have, unfortunately, not been provided with any information about footfall in Watford town centre other than in Charter Place and Intu Watford. Equally, neither party has provided any analysis of the transactions that were concluded. Our assessment cannot therefore be described as empirical.

103. Numbers 52 and 68 High Street are situated in a part of the High Street that was affected by works associated with the scheme. The positive aspect of this location is that once the scheme had been completed there were a number of bus stops nearby, but the buses disgorge their passengers on to the eastern part of the street where they are immediately confronted with the facilities of Intu Watford. Moreover, both units occupy sites on the less attractive western side of the street which contains a mixture of occupiers including banks, restaurants and bars. The adjacencies were not therefore exclusively retail in nature, and we conclude that both positions are inferior to Charter Place.

104. From a positional perspective 122 High Street seemed to us to be a better prospect. We observed on our inspection that this part of the High Street had a reasonable level of footfall, perhaps resulting from those using the lower entrance to Intu Watford, the presence of Marks and Spencer and Primark, and possibly McDonald’s and Costa Coffee, both of whom have large units at this end of the High Street.

105. We reached a similar conclusion about 5 Parade which appeared to benefit from footfall generated from those entering the town from the northern parts of Parade and possibly from Clarendon Road. Although this unit was located close to a number of food and beverage outlets, and was subsequently let to Greggs, it was also close to the extension to Intu Watford and in a pedestrianised part of the town centre.

106. The next aspect of our comparison was configuration and size. All of the units were on two floors, with what appeared to us, to be equal floor space on each level. Each was substantially larger than either the reference or relocation properties, in some cases nearly three times as large. We note that the claimant does not stock an extensive number of products and has no requirement for a large stockroom. We consider that whilst each had adequate frontage and no visible disabilities in terms of layout, they were all too large for the claimant’s business and had they acquired any of them the claimant would be paying for floorspace that they had no requirement for. All of the shops lack any kind of protection from the weather, a notable disadvantage when much of the shop’s stock is displayed in the window. We note that most of the claimant’s competition is in Intu Watford which is fully enclosed.

107. The final criterion is security. We acknowledge that a shopping centre location would usually afford better security to both retailers and their customers, but since jewellers often base themselves in normal shopping streets it would not appear to be a locational prerequisite. All four units are in shopping streets but two are close to restaurants and bars, whose clientele might congregate outside, which might have discouraged the claimant’s customers from lingering in front of the window display.

108. Notwithstanding that two of the locations benefited from reasonably prominent positions with good levels of footfall and those individual properties fulfil some of the selection criteria, none have the optimum combination of physical attributes and outgoings that would make them suitable for the claimant’s business.

109. We therefore conclude from the evidence we heard and the benefit of our inspections that there was no equivalent, alternative store to which the claimant could have relocated in lieu of the relocation property.

The deal for the lease of the relocation property (did the claimant pay too much?)

110. We have already concluded that we lack the information with which to form a view as to whether the claimant was benefiting from a concessionary rent at the reference property. In relation to the relocation property we know that the landlord of Intu Watford considered that the rent achieved was in excess of the estimated rental value of the unit. However, it is not clear by how much. We also know that there was interest in the unit from at least one other party and the experts agreed that the initial rent for the property of £100,000 per annum was likely to have represented the open market rental value at that point in time.

111. We note that the rateable value is £75,000 and that the antecedent valuation date for rating purposes is only a few months ahead of the valuation date in this case. Mr Henderson explained this discrepancy as being possibly due to use of historic data and a conservative attitude on the part of the VO. We have seen no evidence to substantiate this point. We note that the initial rent included a rent free period of six months and taking the whole of that concession over the period to the first review the equated rent is £90,000 per annum. At the hearing the experts agreed that it would not be unreasonable to make the assumption that the inclusion of a break clause in favour of the tenant would have inflated the rent by about 5%. Stripping out this element results in a figure of £85,714 per annum which, although it is closer to the rateable value, is not wholly aligned.

112. Having considered these various aspects, and the opinions of the experts, we conclude that there is no convincing evidence that the claimant paid more than the market rent for the relocation property.

Comparison of reference and relocation properties as value for money

113. The floor areas referred to in paragraph 80 indicate that the two properties were very similar in size, but they failed to take into account the remote store room of 25.5m2 at the reference property and it is evident that the relocation property is smaller in overall size than the reference property if the remote store room is included in the comparison. It has a larger frontage to the mall, but lacks a return frontage resulting in a lower overall figure. It is compromised by changes in floor level and the bulkhead forming part of the mezzanine intrudes in to the sales space, resulting in a shop that appeared to us to be more difficult to fit out and operate. Notwithstanding these deficiencies, the property was identified by the claimant as suitable for their business and had previously operated as a jewellery shop.

114. That said, and having taken into account all of the attributes of the properties under consideration, we conclude that the relocation property was the only suitable option that was available at the time to the claimant. It was in a better position than their former premises, the retail shop was comparable in overall size and was capable of accommodating their corporate fit out merchandising albeit the end result involved a degree of compromise. It had a wider primary frontage than the reference property. Mr Henderson correctly pointed out that the Zone A area was 25% larger but did not acknowledge the disabilities inherent in its layout. It seems to us, on the evidence of Intu Watford itself, that retailers prefer rectangular sales floors with the smaller side forming the frontage. A shop configured with the larger side comprising the frontage will necessarily have a larger Zone A area leading to a higher rent in comparison to an identically sized shop of conventional layout. Additionally, in this case part of the ground floor sales area has been lost to an access area and the headroom compromised in part by the presence of the mezzanine. Regarding shop fitting, we have limited information about the quality of the fit out in the reference property although from photographs taken just before possession was secured, and included in Mr Henderson’s supplemental report, it appears contemporary in design and in good condition. Accordingly, we perceive there to be no material difference between it and the relocation property at the valuation date in this regard.

115. The annual occupational costs associated with the relocation property were £162,112 as an average for the two years to 31 March 2019. This figure includes the annual cost of membership of the Merchants Association. We have ignored YE 2020 because the 2020 rate liability we have been provided with appears to be erroneous and would lead to an unreliable result.

116. These compare to the reference property average of £79,383 for the three years to 31 March 2015, that is the last three full years of trading prior to the compulsory acquisition. We have used these three years. Even after taking inflation in to account it is obvious that after the relocation the claimant’s occupational costs were nearly 90% higher than before. We have no expert evidence to guide us, but take the view that in the no scheme world the costs at the reference property would not have been significantly different to those in 2015. The rent had not increased over the life of the lease, and neither expert stated that the lease renewal would have generated an increase of significance. The same can be said for the rate liability after the 2017 revaluation, although a lower rateable value in the 2017 List would not necessarily have resulted in an appreciably lower liability owing to the incidence of the transitional scheme.

117. Although we regard the relocation property as superior to the shop it replaced, the claimant operates a retail business and the primary measure of whether value for money was achieved must be the extent to which the profit margin altered after the move to new premises. We therefore turn to the evaluation of that loss and the quantification of the compensation that should follow.

Assessment of permanent loss

118. For clarity, we produce here again the management accounts for the Watford store for the trading years 2013 to 2020: