Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> The Propane Company Ltd v Bunyan (RATING -rateable property - preliminary issue - whether stables in separate ownership from a house were an appurtenance belonging to or enjoyed with the house - section 66(1)(b) Local Government Finance Act 1988) [2022] UKUT 237 (LC) (30 November 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2022/237.html

Cite as: [2022] UKUT 237 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

Neutral citation number: [2022] UKUT 237 (LC)

UTLC No: LC-2021-261

Royal Courts of Justice,

Strand, London WC2

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

RATING - rateable property - preliminary issue - whether stables in separate ownership from a house were an appurtenance belonging to or enjoyed with the house - section 66(1)(b), Local Government Finance Act 1988 - ownership not determinative - part of hereditament was domestic property - appeal allowed in part

AN APPEAL AGAINST A DECISION OF

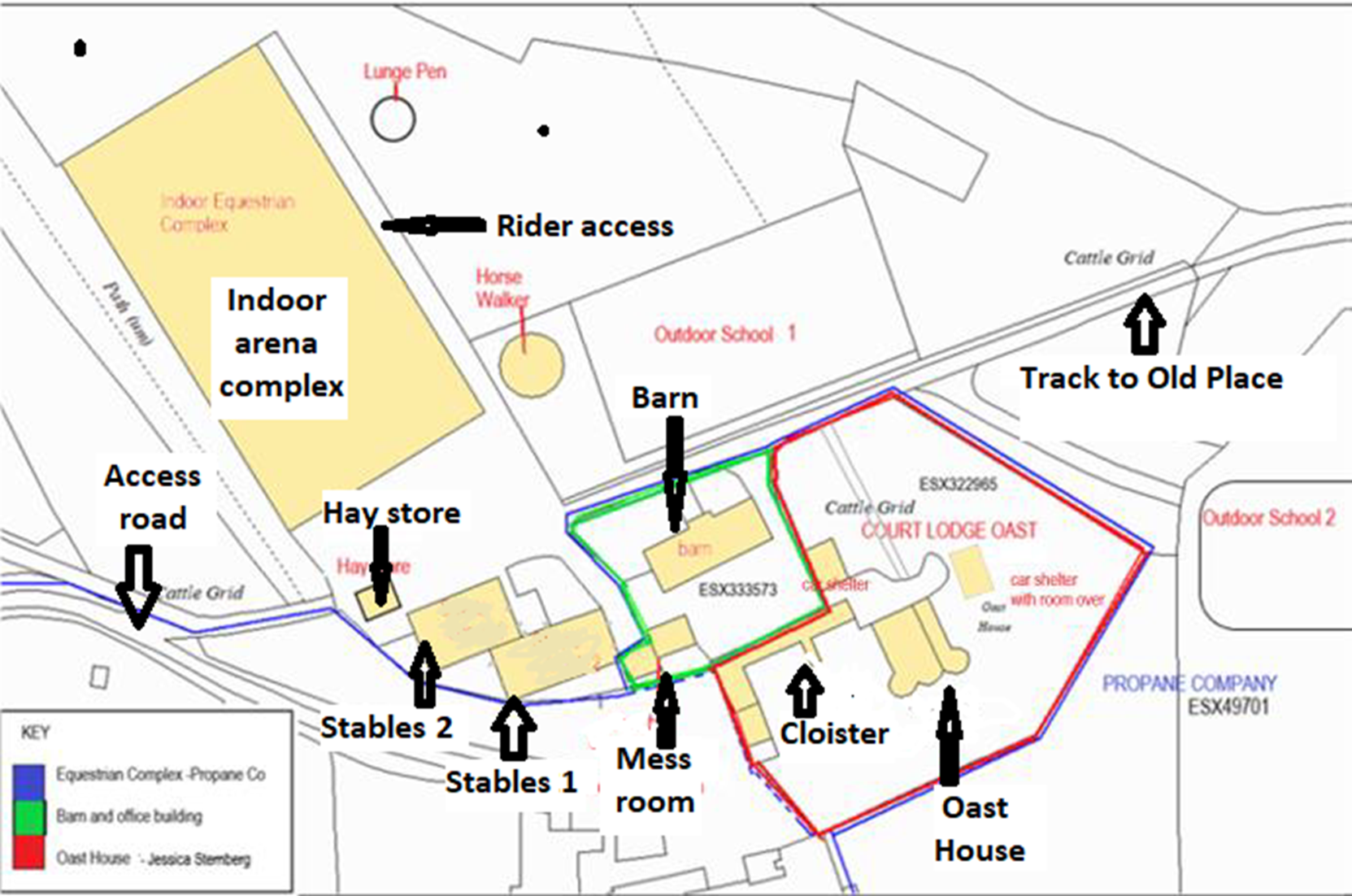

THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL FOR ENGLAND

BETWEEN:

Re: Court Lodge Farm,

Sandhurst Road,

Bodiam,

Robertsbridge,

East Sussex, TN32 5UJ

Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

Heard on: 14 July 2022

Decision Date: 30 November 2022

Cain Ormondroyd, instructed by Altus for the appellant

Mark Westmoreland Smith, instructed by HMRC Solicitors for the respondent

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2022

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Attorney General ex rel Sutcliffe v Calderdale Borough Council (1982) 46 P & CR 399

Clymo v Shell-Mex &B.P. Ltd [1963] RA 191

Corkish (VO) v Bigwood [2019] UKUT 191 (LC)

Cornwall v Alexander (VO) [2014] RVR 504

Head (VO) v Tower Hamlets LBC [2005] RA 177

Martin v Hewitt [2003] RA 275

Introduction

1. This preliminary issue arises in an appeal against a decision of the Valuation Tribunal for England (“the VTE”) dated 24 March 2021 (“the VTE decision”) in which it allowed in part an appeal against the rateable value of £20,250 entered in the 2010 list for stables and premises (“the hereditament”) at Court Lodge Farm, Bodiam in East Sussex. The VTE reduced the assessment to £19,750 with effect from 1 April 2015, but determined that stables in the ownership of the appellant could not be considered a domestic appurtenance to an adjacent dwelling in separate ownership.

2. The Propane Company Limited (“the appellant”) is a family company of the Sternberg family, members of which are directors of it and live in residential property within the farming estate.

3. The appellant contends that buildings comprising 20 stables, a grooms’ mess room and hay store (“the stables”) are and were used exclusively in connection with private equestrian pursuits carried on by the Sternberg family, and are an appurtenance to the adjacent dwelling known as the Oast House, thus falling to be treated as domestic property. The respondent contends that the stables cannot be an appurtenance to the Oast House, which was and is in separate ownership, and are therefore non-domestic property.

4. Following a case management hearing on 26 November 2021 the Deputy President, Martin Rodger QC, ordered that the Tribunal would determine as a preliminary issue: “whether at the material date any part of the non-domestic hereditament constituted domestic property under section 66(1) Local Government Finance Act 1988”.

5. I carried out my inspection on 13 July 2022, accompanied by Mr Philip Emerick for the appellant and Mr Paul Stearn MRICS for the respondent. I was shown the stables, the adjacent equestrian arena and facilities, the garden and buildings around the Oast House and also the house and buildings at Old Place Farm.

6. At the hearing Mr Cain Ormondroyd appeared for the appellant and called The Honourable Francesca Sternberg as a witness of fact. Mr Mark Westmoreland Smith appeared for the respondent and relied on written evidence of fact provided by Mr Paul Stearn, valuation officer for the case. I am grateful to them all for their assistance.

7. After the hearing I asked counsel for both parties to make further submissions on how separate occupation of the stables and the Oast House affects the preliminary issue.

The statutory framework

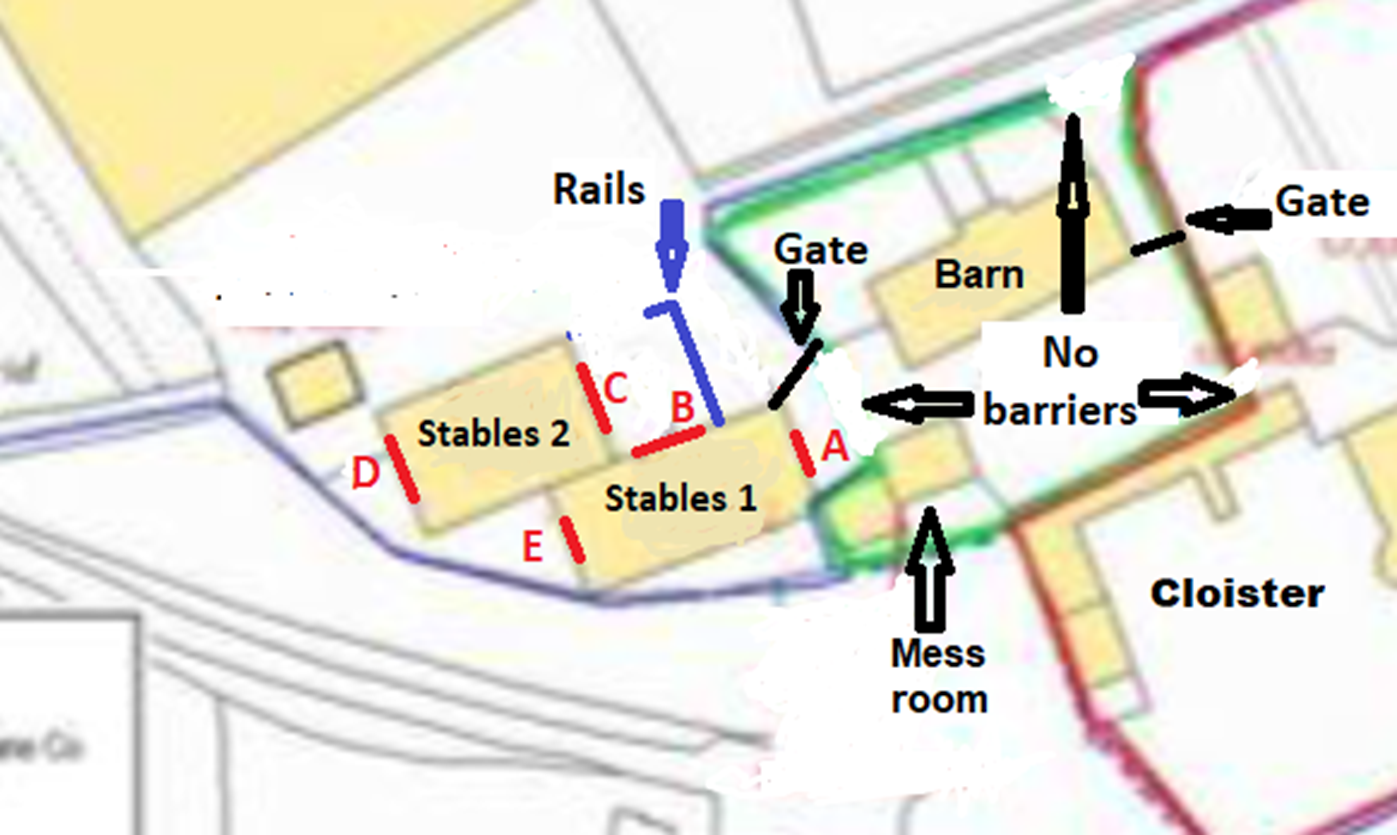

8. The Local Government Finance Act 1988 (“the 1998 Act”) states, so far as relevant to this preliminary issue:

“64(8) A hereditament is non-domestic if either—

(a) it consists entirely of property which is not domestic, or

(b) it is a composite hereditament.

64(9) A hereditament is composite if part only of it consists of domestic property.”

“66(1) … property is domestic if-

(a) it is used wholly for the purposes of living accommodation,

(b) it is a yard, garden, outhouse or other appurtenance belonging to or enjoyed with property falling within paragraph (a) above…”

9. Statute requires that the appeal property be valued reflecting certain matters, including the state and condition, as they existed on the material day, which for the 2010 Non-Domestic Rating List is 1 April 2010.

10. The Non-Domestic (Alteration of Lists and Appeals (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2015 limit the effective date in respect of proposals received on or after 1 April 2015 to no earlier than 1 April 2015.

Rating history

11. The hereditament was first entered into the rating list for Rother District Council by Valuation Officer Notice (“VON”) dated 6 October 2013 at a rateable value of £25,000, with effect from 1 April 2010. Following representations made on behalf of the appellant, the rateable value was subsequently reduced by VON dated 16 July 2014 to £20,250 with effect from 1 April 2010.

12. A proposal was made on behalf of the appellant on 28 September 2017 on the grounds that the rateable value of £20,250 was incorrect and excessive by reason of a VTE decision of 21 June 2017. The decision concerned Stables at Bourne Hill House, Horsham, West Sussex, where it was determined by the VTE that stables forming part of a significant equestrian area were within the curtilage of the house and therefore domestic property. The Valuation Officer did not consider the proposal well founded and refused to alter the rating list. The disagreement was referred to the VTE as an appeal against the refusal and was heard on 25 February 2021. The VTE decision was that the stables were not domestic property, although the appeal was allowed in part by a reduction of £50 for each of the six loose boxes situated within the arena, which had been established to be temporary not permanent.

13. Meanwhile, the VTE’s Bourne Hill House decision was appealed by the Valuation Officer and the appeal was heard by this Tribunal on 19 February 2019. By its decision dated 21 June 2019, Corkish (VO) v Bigwood [2019] UKUT 191 (LC) (“Bigwood”), the Tribunal upheld the decision of the VTE that the stables in that case were domestic property and dismissed the appeal.

The facts

14. The appellant owns and runs the farming business conducted from the Sternberg family estate across 3,500 acres in East Sussex and Kent. The Court Lodge Estate is an 800 acre block of farm land which includes the Oast House and equestrian buildings at Court Lodge Farm, in East Sussex, together with further houses and buildings at Old Place Farm, in Kent. A mile-long track through the estate connects the two farm centres, crossing the Kent Ditch which forms the county boundary. The equestrian centre and associated paddocks and facilities at Court Lodge Farm extend to approximately 3.5 acres. The Oast House is a five-bedroom detached house in the personal ownership and occupation of a member of the Sternberg family.

15. At 1 April 2010 the directors of the appellant were Francesca and her sister The Honourable Rosanne Sternberg, together with Mr James Corrin and Mr Stephen Harlow in their roles as advisers to the family. Rosanne’s daughter, Jessica Sternberg became a director on 25 March 2013.

16. The Sternberg family are keen equestrians who specialise, and compete internationally for Great Britain, in the Western riding sport of reining. To be eligible to compete, individuals must be non-professionals who earn no income from training or showing astride in any equestrian discipline. Therefore, no commercial enterprise is run at Court Lodge Farm and the only family member who has worked commercially in the sport is Francesca’s husband, Mr Douglas Allen. All the family horses are kept in the two stable blocks at Court Lodge Farm, although a few loose boxes are available at Old Place for isolation or to keep a horse overnight if someone has chosen to ride home rather than drive.

17. It was agreed that the layout of the site on the date of my inspection, which was unchanged from the photograph provided by Mr Stearn in his written evidence, should be taken as representative of the layout at the material day, being 1 April 2010. The buildings at Court Lodge Farm are shown on the plan below, with coloured lines indicating separate titles but not necessarily hard boundaries on the ground. The buildings remaining in dispute between the parties are labelled Stables 1, Stables 2, Hay store and Mess room. Originally the Barn was also treated by the respondent as non-domestic, but that point was conceded before the hearing. The VO accepts that it is now domestic property and at the material day was either domestic or agricultural. The appellant accepts that the indoor arena complex (“the arena”) and other facilities on the north side of the track are non-domestic.

18. The parties helpfully provided an agreed chronology of ownership and occupation, which I now summarise. The appellant acquired Court Lodge Farm in 1983 (through its subsidiary Court Lodge Farm Ltd) and shortly afterwards transferred ownership of the Oast House (outlined red and comprising the Oast House, the cloister and two out buildings) to Rosanne. The appellant acquired the adjoining Old Place Farm on 30 April 1991, whereupon Francesca moved into the farmhouse at Old Place, where she has remained, although with no formal agreement for occupation. On 13 May 2009 Rosanne transferred ownership of the Oast House to Jessica and moved overseas. The transfer was subject to a restriction preventing disposal without the consent of Rosanne, care of the appellant, and subject to an option to purchase in Rosanne’s favour. On 13 December 2010 the appellant transferred ownership of the land outlined green ( a courtyard with the Barn and Mess room) to Jessica, subject to a right of pre-emption in its favour. Land and buildings remaining in the ownership of the appellant are outlined blue and include Stables 1, Stables 2, the hay store, indoor arena and land to the north. At the material day the appellant owned the stables, together with the area outlined green, and Rosanne owned the Oast House.

19. When Court Lodge Farm was acquired, there was a range of stables and open storage buildings in the grounds of the Oast House, which are now a cloister feature of the garden. There was also a dilapidated stable building on the site of Stables 1. Stables 1 is a steel portal frame building housing 10 loose boxes, a tack room and grooms’ rest room. Its exact date of construction is not available, but is assumed to be in the mid-1980s. Stables 2 is similar in construction to Stables 1 but simply houses 10 loose boxes. It was constructed in 1991, after Francesca had moved to Old Place and needed provision for her horses also to be stabled at Court Lodge Farm. At that time only a small indoor arena, some stalls and a grain store existed on the site of the current arena.

20. Francesca confirmed that it was the intention of the family to buy back the Oast House and the courtyard should Jessica decide to sell her the freehold interest in them. Both titles are subject to rights of pre-emption, but for the Oast House the right is in favour of Rosanne, who lives overseas. However, she remains a director of the appellant and has obligations to it. The appellant company would always wish to have a house at Court Lodge Farm.

21. The enlargement below shows the layout of the area between the disputed buildings and the Oast House. Where there is no hard boundary on the ground, title boundary lines have been removed. The courtyard area between Stables 1, the Mess room, the Barn and the back of the cloister in the Oast House garden, can be closed off from the access track by two gates as indicated. Otherwise there are no barriers within that area, which is open through to the Oast House with a common brick surface. The access doors to the two stables buildings are indicated on the plan in red, at points A to E, with no direct access from one building to the other. Doorways A to D have sliding doors and doorway E is a roller shutter. Doorway A provides access into the courtyard. Doorways B and C give access to a small area which is part enclosed with rails and can be closed off when necessary with a chain across the gap. Beyond that is the large open concrete yard in front of the arena, through which access to the remainder of the property passes. Doorway D opens out to a concrete area next to the Hay store and is accessible by tractors.

22. In 2006 planning consent was granted for the arena as it stands today, labelled on Google maps as Bodiam International Arena. In 2010 consent was granted for minor amendments to the original design, subject to conditions which included a restriction on the number of events which could be held annually, based on historic use. This amounted to 17 events per year, each lasting three to four days. The arena building is of steel portal frame construction measuring 74.46m long by 36.58m wide. The majority of the space is dedicated to a riding arena with a special deep sand surface suitable for reigning. Riders enter the arena half way down the long east side, through an area fenced off to allow space for six demountable loose boxes and for storage. An area the full width of the building on its south side is dedicated to administrative use, with a viewing gallery above it.

23. The building described as the Mess room was used between 2010 and 2015 for a grooms’ mess room, tack room and hay store, with one room also used as a farm office. The farm office was relocated to the arena in 2011. In 2013 planning consent was granted for residential conversion for a holiday let, but work on the conversion did not commence until 2021.

24. The two stables buildings and the arena were erected at the cost of the appellant. As at 1 April 2010 both sets of stables were full with horses used for competing by Francesca, her husband and Jessica, together with a pony or two for use by Francesca’s children. The horses were owned by and registered in the names of the various family members. Some horses were bought in but many were bred by the family specifically for the sport of reining. The individual stalls were allocated as necessary between the family’s horses without permanent allocation to any family member. The keep of the horses, including feed, bedding, farrier and vet bills were all paid by the appellant. Grooms were paid by the appellant but hiring was done by Francesca and Jessica, who also gave directions to the head groom and allocated horses to individual stalls within the stables.

25. An extract from the appellant’s accounts for 2009 to 2013 shows income and expenditure for the family’s equestrian activities, conducted under the name of Sterling Quarter Horses. Income was received from livery, training, horse sales, breeding and arena hire. Commercial income included arena hire, livery and training, all of which was generated at the arena, with liveries only ever stabled in the six stables within that building. Income from horse sales and breeding was not considered to be commercial income.

26. Electricity and water at Court Lodge Farm have always been shared between all the equestrian buildings and the Oast House, with only one meter on site for each service. The cost of both services is paid by the appellant and then apportioned in the accounts between the arena, the stables, and the Oast House using an agreed formula.

The issue

27. The issue to be determined is whether at the material day any part of the non-domestic hereditament (the stables and premises) constituted domestic property by virtue of being an appurtenance enjoyed with property used wholly for the purposes of living accommodation at the Oast House and/or at Old Place.

Submissions for the appellant

28. The appellant relies on the Tribunal’s decision in Bigwood, in which authorities relevant to the meaning of “appurtenance” in s.66(1)(b) were reviewed, and the Tribunal upheld the decision of the VTE, on the facts of that case, that the private equestrian facilities of substantial scale at Bourne Hill House were domestic rather than non-domestic property.

29. By contrast, the VTE decision for the hereditament found that the stables did not fall within s.66(1)(b) as an “appurtenance belonging to or enjoyed with…” domestic property because the stables were in separate ownership from the Oast House. Mr Ormondroyd submitted that the VTE’s reliance on Land Registry entries was flawed since the actual conveyancing history cannot be determinative. s.66(1)(b) refers to an appurtenance “belonging to or enjoyed with” property falling with s.66(1)(a), so he submitted that the appurtenance does not have to belong to the property with which it is enjoyed. Nor does statute impose a requirement that the appurtenance be occupied with the property which it serves. If that were the case, the requirement that it be enjoyed with the domestic dwelling would be redundant. Insofar as it is necessary to consider occupation, at the material day the stables were jointly occupied by Jessica and Francesca Sternberg and their immediate family. Alternatively, the stables were occupied by the appellant as agent for them.

30. Bigwood has provided recent guidance on appurtenance. As stated at [36]: “The question was whether the facilities came within sub-section 1(b) as being an “appurtenance belonging to or enjoyed with” the house.” The VO had submitted that an appurtenance must fall within the curtilage of the living accommodation. Having reviewed authorities on the meaning of “curtilage” in listed building cases the Tribunal said at [54]:

“…we do not consider it safe to substitute a different word used in a different context when considering whether the equestrian facilities in this case are appurtenances… for the purpose of rating. The better approach, as urged by the Court of Appeal in Clymo v Shell-Mex & B.P. Ltd [1963] RA 191 at 202 is that “the question to be answered is whether the land is properly to be described as an appurtenance in all the circumstances of the case.” In considering that question we take into account the nature and function of the buildings and other facilities themselves, their proximity to each other and the general layout of the site.”

31. Mr Ormondroyd drew attention to the Tribunal’s statement at [55] regarding size: “…there is no rule that a large building, such as a barn or stable, cannot be appurtenant to a smaller building, such as a house”. At [59], having reviewed higher authority, it continued: “In general, therefore, stables are a category of building which falls readily within the scope of appurtenant property.” And at [64] it stated: “More important than the size of the facilities is their function of accommodating horses belonging to the owners of a private family home, which they keep for their own and their family’s pleasure including for competition. We do not regard that function as different in kind from stables attached to a house belonging to any other equestrian enthusiast and used by their family.”

32. It was Mr Ormondroyd’s case that the same criteria should be applied in this case to find that the stables are domestic property. He accepted that ownership is a relevant consideration but submitted that it is not determinative or even particularly important. As the Tribunal noted in Bigwood at [50] in Attorney General ex rel Sutcliffe v Calderdale Borough Council (1982) 46 P & CR 399, a case concerning the curtilage of a listed building, Stephenson LJ identified three relevant factors in determining whether a structure was within the curtilage of an existing building, namely: the physical ‘layout’ of the listed building and the structure; their ownership, past and present; and their use or function, past and present. But these are relevant factors, not tests as they were later described by the President of the VTE in Cornwall v Alexander [2014] RVR 504.

33. Taking each of those relevant factors in turn, Mr Ormondroyd submitted that the layout of the buildings comprising the hereditament shows that the stables are in the curtilage of the Oast House. Past ownership confirms this since, prior to purchase by the appellant in 1983 and transfer of the Oast House to one of its directors, there was unity of ownership of the Oast House and the area where the stables are now sited, on which stood dilapidated stables at that time. Finally, the use and function of the stables in both the past, prior to purchase, and at the material day has been associated with the house. Does separate ownership prevent common use and function? It could if there was an unconnected third party owner, but having separate ownership has not undermined the physical and functional relationship on this hereditament.

34. Regarding enjoyment with the Oast House, Mr Ormondroyd submitted that both the stables and the arena are enjoyed with it, but the difference is that the arena is used for limited commercial purposes. This involves Francesca’s husband training people on their own horses and up to 17 competition events per year. Horses brought for training are stabled in the six temporary boxes inside the arena building. Horses brought for events are accommodated in rows of temporary stalls erected on land away from the arena. There is therefore no link between the commercial activities and the stables. They are used by the occupier of the Oast House for her own purposes. Whilst Jessica may have no proprietary right to use the stables she does not need one and has never been prevented from doing so. Just as Francesca has occupied her house at Old Place for 30 years without any formal documentation of rights, it is a family arrangement. The appellant pays the bills and costs of the stables and provides staff to do maintenance work, all as a benefit to its directors. It serves the purpose of the family and is not separate from it.

35. The stables are also used by Francesca, who lives at Old Place, but this does not make them non-domestic. There is no requirement that the stables should be enjoyed with only one dwelling or be in common occupation with another dwelling. In Allen v Mansfield District Council [2008] RA 338 the Tribunal (HHJ Huskinson) found at [26] that a district heating system was not appurtenant to living accommodation unless it was situated within an identifiable curtilage used wholly for the purposes of living accommodation to which it belonged or with which it was enjoyed but, if that condition was satisfied, it would not cease to be satisfied merely because the system served other dwellings outside the property within whose curtilage it lay.

36. Drawing a comparison with the findings in Bigwood, Mr Ormondroyd submitted that the stables at this hereditament are a category of building within the scope of appurtenant property and their function is to accommodate horses belonging to the owners of private family homes at the Oast House and Old Place. Moreover, there is proximity to the Oast House and the general layout does not separate them. Separate ownership is heavily relied on by the respondent as a reason for the stables being non-domestic property, but this must be considered in the round in the context of other factors. Historically the area where the stables are located was in the same ownership as the Oast House and separate ownership has not affected their use and function.

Submissions for the respondent

37. Mr Westmoreland Smith submitted that with regard to curtilage within which the stables could be appurtenant property, the only realistic candidate for living accommodation was the Oast House. The appellant had suggested that the house at Old Place, which is in common ownership with the stables, could also be considered as relevant living accommodation, but it is a mile away up a track and in another county. The stables cannot be within its curtilage, as concluded by the Tribunal in Martin v Hewitt [2003] RA 275 where three boathouses on the shores of Lake Windermere were found not to be domestic property because they were a substantial distance from the living accommodation of their owners and therefore not appurtenances within the curtilage of those houses.

38. Regarding the requirement that the appurtenance should belong to or be enjoyed with living accommodation, the respondent suggested that because, as owner of the Oast House, Jessica has no personal right to use the stables which belong to the company they cannot be enjoyed with it. They are enjoyed with the arena, where the horses are ridden.

39. Looking at their function, the stables support the Sternberg family in their sport of reining and the arena is integral to that. The current arena replaced an earlier indoor arena on that site. The accounts of the appellant give a feel of the activities on the site. The sale of horses belonging to family members involves using the arena to ride and show them for sale. The arena and stables are for specialist horses and there is no material boundary between them. They have a shared access road. Both the stables and the arena are owned by the appellant, who covers all the costs of keeping the horses, including the wages of staff. There is one meter and one bill for each of the services on site. Those using the stables do not spring from one single identifiable accommodation and the Oast House is not owned in common with the stables. The stables are not enjoyed with the Oast House, but with the arena, which ties everything together by providing the facility to train the horses kept in the stables. The stables are in close proximity to the arena and have access to it (from Doorways B and C).

40. Mr Westmoreland Smith submitted that the need for an appurtenance to be within the curtilage of the house was folded into the Bigwood decision by reference to case law. The concept of curtilage had not been jettisoned. In Methuen-Campbell v Walters [1979] QB 525 (at 543H) LJ Buckley said “In my judgment, for one corporeal hereditament to fall within the curtilage of another, the former must be so intimately associated with the latter as to lead to the conclusion that the former in truth forms part of the latter.” In Bigwood at [61] the Tribunal referenced that observation, stating that the size of the equestrian buildings and the professional use of the facilities did not prevent them from being “intimately associated” with the house so as to form “part and parcel” with it. That is not the case at this hereditament.

41. Mr Westmoreland Smith accepted that an appurtenance could be enjoyed with living accommodation as an alternative to belonging to it. In the Lands Tribunal decision of Head (VO) v Tower Hamlets LBC [2005] RA 177 it was held that district heating systems integral to the council’s residential buildings were appurtenant to living accommodation, even though not to any individual hereditament, and therefore fell to be treated as domestic property. However, in Allen the Tribunal found at [26] that a district heating system was not appurtenant to living accommodation unless it was situated within an identifiable curtilage used wholly for the purposes of living accommodation to which it belonged or with which it was enjoyed. In this case the stables are not integral to the curtilage of the Oast House.

42. In Bigwood the key difference from this hereditament was the unified ownership between the house and the equestrian facilities. No reference was made to ownership in the decision as it was not relevant to that case. However, in Cornwall v Alexander, the President of the VTE, Professor Graham Zellick QC, had concluded from his summary of case law relevant to the meaning of “curtilage” that there were three tests: physical layout, ownership (past and present) and use or function (past and present). In this case ownership of the Oast House at the material day is a problem for the appellant because Jessica, as owner of the Oast House, did not become a director until 25 March 2013. There was therefore no connection between the ownerships at the material day. Moreover, although Rosanne has an option to purchase the Oast House, the appellant does not. It only has an option to purchase the courtyard area (outlined green on the plan above).

43. Mr Westmoreland Smith concluded that the stables are not in the curtilage of the Oast House. They are entered from the appellant’s land, not from the Oast House and are more closely associated with the arena than the house. The stables are close to the Oast House, but closer to the arena. Although the access road passes between the stables and the arena there is only a physical barrier between them when a chain is hung across the opening beside Stables 2. The users of the stables come from Old Place as well as the Oast House and the unifying factor is the arena where horses from the stables are ridden.

44. He submitted that there is no prospect of the stables passing in any conveyance of the Oast House as they are in different ownership and not part and parcel of it. They therefore fall outside of ss.66(1)(b).

Discussion

45. In Bigwood the Tribunal reviewed authorities on the meaning of “curtilage” in the context of listed buildings, but noted that the context of the 1988 Act is different and avoided further reliance on that word. Mr Westmoreland Smith’s submissions nevertheless insisted on addressing the question of whether the stables were in the curtilage of the Oast House. That is not the statutory question. At [54] the Tribunal in Bigwood stated that in considering whether the equestrian facilities were appurtenances for the purposes of rating they took into account “…the nature and function of the buildings and other facilities themselves, their proximity to each other and the general layout of the site.” I will use these criteria to consider first whether the disputed buildings are capable of being considered appurtenances for the purposes of rating, before moving on to the issue of separate ownership of the living accommodation with which they are enjoyed.

46. This is a case where a site inspection can create a fresh perspective. It was apparent on site, as illustrated in the enlargement plan at paragraph 21, that although the two stables buildings are treated as a single entity by the parties, there are notable differences between them in the context of this preliminary issue. I look first at the nature and function of the buildings and facilities, both in the past and at the material day.

47. Stables 1 was constructed at some time in the mid-1980s, to replace an older, dilapidated stables building. As I understand the evidence, until 1991 Stables 1 was used exclusively by Rosanne, who lived at the Oast House. The 10 stables were sufficient for her use as a rider and competitor and the functional link of use and enjoyment between the two buildings was established by that date. The provision of stabling at the hereditament was extended in 1991, by the construction of Stables 2, because Francesca had moved to Old Place and additional stabling was needed to accommodate her family’s horses.

48. Once Stables 2 had been constructed, twice as many horses could be stabled at Court Lodge Farm and, from 1991 onwards, the use and enjoyment of all the stables was shared between Rosanne, her sister Francesca and their respective families. So, the functional link with the Oast House continued through to the material day, with an additional functional link of use and enjoyment with the living accommodation at Old Place.

49. Turning now to the proximity of buildings to each other and the general layout of the site, the enlargement plan shows that there is an open space and ungated connection between Stables 1 and the Oast House through the courtyard. Access to the courtyard can also be gained from the cloister building in the Oast House garden. Standing in the courtyard the connection between the two buildings is apparent and, in my view, this layout reinforces the functional link between the Oast House and Stables 1 which has existed since the stables were constructed. At the material day, the Mess room in the courtyard between the two buildings was in use as a grooms’ rest room, tack room and hay store associated with both Stables 1 and Stables 2.

50. As the Tribunal confirmed in Bigwood, in the context of this sort of building, size is less important than function so, had their proximity and layout been different, it might have been possible to conclude that both stable buildings and all 20 stables had a functional link with the Oast House. But the Stables 2 building is situated outside the gated area and has no direct connection with Stables 1, the courtyard or the Oast House. The Hay store sits beyond Stables 2 and has no obvious functional link with the Oast House.

51. I therefore consider that at the material day Stables 1 and the Mess room were appurtenant to the Oast House, by reason of their historic and continuing nature and function, their proximity to each other and the general layout of the site. Stables 2 and the hay store were not appurtenant to the living accommodation and are not domestic property within the meaning of s.66(1).

52. I now consider whether the fact that Stables 1 and the Mess room were in separate ownership from the Oast House, with which they were and are enjoyed, prevents them from being appurtenances, and therefore domestic property, for the purposes of the 1988 Act. Does separate ownership trump the finding on other well established criteria? This seems to me to be a matter of degree, very much depending on the identity of the different owners.

53. It was not, in the end, Mr Westmoreland Smith’s submission that an appurtenance cannot be domestic property if it is enjoyed with living accommodation held in separate ownership. He accepted that s.66(1)(b) allows “enjoyed with” with as an alternative to “belonging to”. His submission was that in order to be called appurtenant to living accommodation the property must sit within its curtilage, and the definition of curtilage itself requires consideration of ownership. He relied on the criteria originally stated by Stevenson LJ in Sutcliffe, when considering the concept of curtilage for a listed building. Those criteria were physical layout, ownership (past and present) and use or function (past and present). In Sutcliffe common ownership was a factor which underpinned the decision to include 15 cottages within the curtilage of a listed mill building. Separation of ownership was not an issue that was considered, and the decision concerned listed buildings, so it can take us no further in the context of the 1988 Act.

54. Considering the separation of ownership in this case, I bear in mind that at the material day the appellant owned not only the stables but also the courtyard area outlined green, which was not transferred to Jessica until nine months later in December 2010. Within the courtyard stand two buildings: the Barn and the Mess room. Both buildings were originally treated by the respondent as non-domestic but, by the date of the hearing, the respondent had conceded that the Barn was domestic property. I agree with this concession, which is supported by its function and the physical layout of the courtyard, and I apply the same approach to the Mess room.

55. Stables 1 is different because at all times since its construction it has been in separate ownership from the Oast House. However, in this case the appellant is a company which manages the commercial and financial affairs of one family. Mr Ormondroyd describes it as the agent for the family. The owner of the Oast House at the material day was a member of that family, although not at that time a director of the appellant. Her mother, the former owner of the Oast House, was a director of the appellant at the material day and retained a personal right of pre-emption over the Oast House. The separate ownerships have not diluted the functional link which has existed between the Oast House and Stables 1 since that building was constructed in the mid-1980s because in this case the separate ownerships are hand in glove.

56. In Bigwood at [54] the Tribunal explained why it was appropriate to focus on the word “appurtenance” rather than “curtilage” in the context of the 1988 Act and I have already concluded that Stables 1 and the Mess room were appurtenances to the Oast House at the material day. The separate ownership of the Oast House did not prevent those buildings from being enjoyed with it for the purposes of s.66(1)(b) at the material day and does not prevent them from being appurtenances.

Disposal

57. For these reasons I find that Stables 1 and the Mess room were appurtenances to living accommodation at the Oast House at the material day and therefore fall to be treated as domestic property. Stables 2 and the Hay store were not appurtenances and fall to be treated as non-domestic property with the arena.

Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

Member, Upper Tribunal

(Lands Chamber)

Right of appeal

Any party has a right of appeal to the Court of Appeal on any point of law arising from this decision. The right of appeal may be exercised only with permission. An application for permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal must be sent or delivered to the Tribunal so that it is received within 1 month after the date on which this decision is sent to the parties (unless an application for costs is made within 14 days of the decision being sent to the parties, in which case an application for permission to appeal must be made within 1 month of the date on which the Tribunal’s decision on costs is sent to the parties). An application for permission to appeal must identify the decision of the Tribunal to which it relates, identify the alleged error or errors of law in the decision, and state the result the party making the application is seeking. If the Tribunal refuses permission to appeal a further application may then be made to the Court of Appeal for permission.