Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Allen v Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums (RATING - VALUATION) [2022] UKUT 206 (LC) (03 August 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2022/206.html

Cite as: [2022] UKUT 206 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

UT Neutral citation number: [2022] UKUT 206 (LC) UTLC

Case Number: LC-2020-75

LC-2020-77

LC-2020-78

AIT North Shields

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

RATING - VALUATION - rateable value of museums - socio-economic value - value to the occupier

AN APPEAL AGAINST A DECISION OF THE

VALUATION TRIBUNAL FOR ENGLAND

BETWEEN:

|

|

MR JUSTIN ALLEN (VALUATION OFFICER) |

Appellant |

|

|

-and- |

|

|

|

TYNE & WEAR ARCHIVES AND MUSEUMS

|

Respondent |

Re: Shipley Art Gallery, Prince Consort Road, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear NE8 4JB

Laing Art Gallery, Higham Place, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8 AG

South Shields Museum, 6 Ocean Road, South Shields, Tyne and Wear, NE33 2HZ

Judge Elizabeth Cooke and Mr Mark Higgin FRICS

Heard on: 17-18 May 2022

Decision Date:

Paul Reynolds, instructed by the HMRC Solicitor, for the appellant

Jenny Wigley QC, instructed by Stuart Ward Solicitors, for the respondent

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2022

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

BNPPDS Limited & BNPPDS Limited (Jersey) as Trustees for BlackRock UK Property Fund v Andrew Ricketts (VO) [2022] UKUT 129 (LC)

Hoare (VO) v National Trust [1998] EWCA Civ 1525

Hughes (VO) v York Museums and Gallery Trust [2017] UKUT 200 (LC)

London County Council v Churchwardens of Erith [1893] AC 562

Stephen G Hughes (VO) v Exeter City Council [2020] UKUT 7 (LC)

Introduction

1. The Brazilian Salmon Pink Tarantula (Lasiodora parahybana) devours its prey by dissolving the victim in digestive fluid before sucking the results into its mouth. This gruesome fate awaits the unlucky crickets that are kept in a basement storeroom at South Shields Museum and Art Gallery as an amuse bouche for the arachnids that live (in cases) on the ground floor. A Tyneside museum might seem an unlikely location to find a collection of venomous spiders but their presence is indicative of some of the issues that underlie these appeals, in particular the value of the museums to their localities and communities and the extent to which that value should be reflected in their rateable value.

2. These appeals relate to the appropriate 2010 rating list values for the Laing Art Gallery (‘the Laing Gallery’) in Newcastle, the Shipley Art Gallery (‘the Shipley Gallery’) in Gateshead, and the South Shields Museum (‘South Shields Museum’).

3. The appeals arise from a decision of the Valuation Tribunal for England (“VTE”) dated 3 December 2020 which determined each of the assessments at a nominal level. In doing so the VTE cited the decision of the Tribunal (the President, the Hon Sir David Holgate and Andrew Trott FRICS) in Hughes (VO) v Exeter City Council [2020] UKUT 7 (LC)) (“Exeter Museums”). That decision, together with Hughes (VO) v York Museums and Gallery Trust [2017] UKUT 200 (LC) (“York Museums”), provided a comprehensive review of the law relating to the valuation of museums for the purposes of non-domestic rates and remains the leading authority on the point.

4. It is perhaps therefore a surprise that another appeal has been added to that collection. The appellant Valuation Officer (“the VO”) argues that it is possible, and consistent with the decision in Exeter Museums, to refine the existing methodology for valuing museums by assessing their “socio-economic value”, meaning their non-financial benefit to the public and their economic value to public authorities. That value, he says, when taken into account in calculating rateable value, yields a positive value for all three properties. Accordingly it is for the Tribunal to consider the expert evidence of socio-economic value put forward by the VO and to decide whether it has the effect of converting what would otherwise be a nominal rateable value into a higher one.

5. We visited all the three museums on 16 May 2022. For comparison we also visited two other museums in the centre of Newcastle, the Discovery Museum and the Great North Museum: Hancock.

6. The appellant was represented by Paul Reynolds of counsel, and the respondent by Jenny Wigley QC. We are grateful to both for their assistance.

The appeal hereditaments

7. All three museums are operated by the respondent, Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums (“TWAM”), a body created by four local authorities in Tyneside (Newcastle City Council, Gateshead Council, South Tyneside District Council and North Tyneside District Council) to which they have delegated their function under sections 12 and 14 of the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964 of providing a museums service. Jacqueline Reynolds-Sinclair, Head of Finance, Governance and Resources at TWAM, who gave evidence on behalf of the respondent, explained that TWAM achieves economies of scale, and that its effectiveness is recognised by the Arts Council which provides some of the funding for the museums. Without the joint committee the museums would not be able to attract the same level of funding and indeed, according to Ms Reynolds-Sinclair, would struggle to operate.

8. TWAM is not a legal person. It cannot enter into contracts or employ staff, and so the participating local authorities do so on its behalf. Mr Reynolds observed therefore that it cannot be the occupier of the museums for the purposes of non-domestic rates, which must instead be the relevant local authority, and Ms Wigley QC did not express disagreement. The parties agree that this makes no difference to the arguments in the appeal and are both content for TWAM to be the respondent.

9. None of the three museums charges for admission.

10. All three museums operate at a deficit; the agreed figures provided to us, which we believe are for 2008, are £789,481 for the Laing Art Gallery, £420,103 for the Shipley Art Gallery, and £481,070 for the South Shields Museum.

11. When we visited the museums, we were impressed by the wide range and high quality of exhibits, from a Tintoretto to tarantulas, from fabrics to photography, by the enthusiasm of the staff who showed us round, and by the huge range of interests catered for. It was also very noticeable that all three museums devoted space and equipment to children and school parties and obviously attached great importance to education and the well-being of children. Equally noticeable was the huge amount of space devoted to storage in each museum, perhaps most of all at the Shipley Art Gallery where we were told that about 5% of the collection is on display at any time.

Laing Art Gallery, Higham Place, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8AG

12. Most of this Grade II listed gallery was purpose built in 1903-04 but it also incorporates an older Victorian building originally used in part as stabling. The gallery was extended in 1996 to provide a new entrance, lifts, and a mezzanine level with a multi-purpose meeting room. In its original configuration the gallery had a central courtyard which has been infilled to provide galleries at ground and first floor levels with offices above. On the ground floor are a shop and café, and there is an education area for school visits as well as extensive storage, and workspace for research. The gross internal area of the building is 4,621m².

13. The gallery is in Newcastle city centre, approximately 0.5 miles north east of Newcastle railway station and just to the west of the A167(M) road which bisects central Newcastle on a north/south axis. There is no dedicated parking although there are several public car parks nearby.

14. The gallery was initially funded by a benefactor, Mr Alexander Laing. The funds were given for the specific purpose of providing the city with an art gallery, although no collection was provided with the funding. The 1996 extension which cost £1,301,500 was 75% grant funded by the Foundation for Sports and the Arts, the European Development Fund, and the Heritage Lottery Fund. The City Disability Fund provided a further £33,700 and the balance was met by Newcastle City Council. The freehold is held on trust by Newcastle City Council for the Laing Gallery, which is a registered charity.

Shipley Art Gallery, Prince Consort Road, Gateshead, Tyne and Wear NE8 4JB

15. Shipley Art Gallery was also purpose-built, in 1915. It is Grade II listed, in the classical style with a substantial projecting porch, Corinthian columns and bow-ended side wings. The main structure contains single storey tall galleries whilst stores, ancillary offices, and workshop accommodation are provided in the basement. The building’s gross internal area is 1,948 m².

16. The property is in Gateshead approximately 2.5 miles south of Newcastle city centre. It occupies a prominent position, in a parkland setting just off the Durham Road. Rough surfaced parking for users of the park is located close to the gallery and there is limited on street parking nearby.

17. The gallery was built with funds provided by a local solicitor John Shipley, who also bequeathed his art collection to Gateshead for display to the public. The freehold is owned by Gateshead Council.

South Shields Museum, 6 Ocean Road, South Shields, Tyne and Wear, NE33 2HZ

18. This Grade II listed property was originally built as the South Shields Literary, Mechanical and Scientific Institute in 1860. Arranged over basement, ground, and first floors it was built in the Italianate style with brick and stone elevations and a pitched slate roof. It was subsequently donated to the local council and became a free public library in 1876. It remained in that use until 1976 when the library was relocated. The property then was converted to a museum and gallery. It was extended in 1996 and again in 2004.

19. The ground floor has a large display area, including the showcases for snakes and the previously mentioned spiders (the museum has a zoo licence), and a small café. On the first floor there is more exhibition space, a meeting room, and a staff area with a kitchen and stores. The basement contains stores, a preparation area for the café, and a reception area for deliveries. Its gross internal floor area is 1,367m².

20. The 1996 extension created a new entrance and disabled access, and cost £1,475,621. Grants and donations made up 94.4% of the project funding with significant contributions from South Tyneside Council, the Heritage Lottery Fund, Tyneside Enterprise Partnership, European Regional Grant and Catherine Cookson Charitable Trust.

21. The property is in South Shields town centre about 7 miles east of Newcastle city centre (much further by car because it is on the south side of the River Tyne). The freehold is held by the South Tyneside District Council.

The appeals

22. The properties were assessed for the purposes of the 2010 Rating List as follows:

Laing Art Gallery - £193,000

Shipley Art Gallery - £94,500

South Shields Museum and Art Gallery - £62,500

The decision of the VTE on 3 December 2020 determined a nominal rateable value of £10; the effective date is 1 April 2015 for all three properties because of the limitation on backdating imposed by legislation. The VO concedes that the original assessments were too high but argues that the assessments should be amended as follows:

Laing Art Gallery - £46,800

Shipley Art Gallery - £3,500

South Shields Museum and Art Gallery - £12,900

The legal background

23. Schedule 6 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988, as amended by Section 1(2) of the Rating (Valuation) Act 1999, sets out the basis on which the rateable value of a non-domestic hereditament is to be determined. It is equal to the rent at which the hereditament might reasonably be expected to let from year to year at the material day (in this case 1 April 2010) but having regard to values at the antecedent valuation date (in this case 1 April 2008). It is assumed to be in a state of reasonable repair (excluding any repairs which a reasonable landlord would consider uneconomic), with the tenant paying all usual tenant’s rates and taxes and bearing the cost of repairs, insurance and any other expenses necessary to maintain the hereditament.

24. There is no legal rule prescribing the method by which that rental value is to be determined; it is a matter of valuer judgment. In the majority of cases the best approach is to look at the rental evidence from comparable properties. As the Tribunal (the Deputy President, Martin Rodger QC and Peter McCrea FRICS) put it in York Museums:

“113. The best evidence of rental value is provided by rents for comparable properties agreed in the open market. The greater the adjustments required to be made to mirror the statutory valuation assumptions or other differences, the less reliable a guide the comparable may be, but valuation by the comparative method always has the advantage over other methods of being rooted in evidence of the behaviour of real landlords and tenants in the market in which it is to be assumed the subject premises are being let.”

25. Where there is no rental market for the property in question, alternative methods are used. One is the receipts and expenditure method, which the Tribunal explained in York Museums as follows:

"119. The receipts and expenditure method seeks to arrive at the annual rental value of premises by assessing the gross receipts which a prospective tenant would expect to achieve from a business carried on at those premises, and by deducting operating expenses, including the cost of repairs, and a sum to reflect the return on capital and profit the tenant would require, to determine the surplus which it is assumed the tenant would be prepared to pay to the landlord in rent in return for the annual tenancy. Another way of looking at the assessment is to regard its first stage as being the ascertainment of a net profit (or “divisible balance”) which may then be apportioned between the tenant, to provide a return on capital and a profit (in aggregate, the tenant’s share) and the landlord, as the rent in return for the annual tenancy (the landlord’s share).”

26. Related to it is the shortened receipts approach:

“128. … which seeks to determine the rent at which a hereditament would be expected to let by basing the assessment on a percentage of turnover, rather than on a full appraisal of both receipts and expenditure. Where, in respect of a particular mode of occupation, a consistent relationship can be demonstrated between the turnover of businesses of that type and the levels of profit they generate, a shortened approach can be useful”

27. The other alternative method is the contractor’s basis, which has been described as a method of last resort and which is used where there is no rental market for the property and where the receipts and expenditure method is inappropriate. It is based on the calculation of the replacement capital cost of the hereditament and the assumption that the rental value is related to that cost, being the sum that would be paid by a tenant who did not have the funds to construct the hereditament.

28. As we said above, this is the third occasion in recent years where a case has come before the Tribunal relating to the rating assessment of a museum or gallery. In York Museums the Tribunal examined the appropriate methods of valuation before determining that one of the museums in question (The Yorkshire Museum) should be assessed at a rateable value of £1 on the basis of a receipts and expenditure approach. Four other museums were determined at higher figures. The Valuation Office Agency (“VOA”) did not appeal that decision.

29. However, the VOA pursued a second appeal in Exeter Museums in respect of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery at Exeter (“the RAMM”). Once again, the method of valuation was in dispute and the Tribunal conducted an exhaustive appraisal and analysis of all the available valuation methods before concluding that the receipts and expenditure method was the most appropriate in the circumstances of the case.

30. It was agreed that that method produced a negative figure, even on the assumption that the museum charged for admission. Notional total receipts were agreed at £1,307,500 based on 182,000 adult visits at £5 each and 68,000 child visits at £2.50 each. A further £100,000 of other income was added. Expenditure was £2,300,000 and the outcome was therefore a negative figure of £992,500 and a nominal rateable value. The receipts and expenditure calculations in the York Museums case made the same assumption that in the imaginary world of the rating hypothesis the museums would charge for admission.

31. It is well-established that just because a hereditament cannot be occupied profitably its rateable value is not necessarily nil (London County Council v Churchwardens of Erith [1893] AC 562).

32. It is equally well-established that where - as will typically be the case for purpose-built museums - the actual occupier is the only possible occupier, and therefore the only hypothetical tenant, that does not necessarily mean that the hypothetical tenant will offer a nominal rent and the landlord will accept it; but it does mean that the affordability of the rent is relevant. In Exeter Museums the Tribunal said at paragraph 71:

“in this case it is common ground between the parties that the Respondent would be the only bidder for the hypothetical letting. Accordingly, its financial ability (or otherwise) to pay the rent contended for is a relevant consideration in deciding how much weight to give to the valuation opinions advanced before us. Furthermore, we should have regard to the circumstances of the Respondent. It is a local authority which is subject to democratic accountability. It also has legal responsibilities with regard to the setting of its budget and financial management. … In effect, the authority has a duty to exercise financial prudence in determining its expenditure and the use of its resources.”

33. In both the York Museums and the Exeter Museums cases it was acknowledged that the motivation of the occupier is not profit but the provision of a non-financial benefit to the public. The cultural and educational value that a museum confers on its visitors and even on those who do not visit it has a value to the occupier. In York Museums at paragraph 124 the Tribunal said:

“124. A particular problem with the receipts and expenditure basis is the difficulty of its application where the hypothetical tenant can be assumed to have a motive for taking the tenancy which is not, or is not only, the making of a profit….

125. A variety of different solutions to the problems of valuation have been adopted. … [S]ometimes an allowance or “overbid” has been assessed as representing the additional amenity value to the district which motives a public provider.

34. In neither case was there evidence to indicate what that overbid would be. To calculate it requires an assessment of the socio-economic value of the hereditament to the occupier, and then a judgment as to how much of that value would be reflected in the rent that the hypothetical tenant was willing to pay.

35. We need to pause here and say a word about terminology. The term “socio-economic value” means the value placed on a combination of benefits such as cultural education, community, mental health and well-being which do have a broad economic effect (better mental health means less cost to health services) but are not commercial objectives. The assessment of socio-economic value is an attempt to put a monetary value on benefits which do not represent money in the pocket of the occupier of the hereditament but which that occupier values and might well spend money to gain. Hence it is said that the occupier may have a “socio-economic motivation”. The term “social value” is used in some sources and by some experts as a synonym for “socio-economic value” and in this judgment unless we say otherwise the two terms mean the same.

36. In Exeter Museums at paragraph 97 the Tribunal said:

“We have not been referred to, nor are we aware of, any valuation technique which enables the socio-economic motivation for a local authority’s occupation of a hereditament to be directly estimated as an annual letting value, or component thereof.”

37. Nevertheless at paragraph 162 the possibility was left open:

“there is no legal principle or valuation practice which would preclude the modification of the R & E method for properties of the unusual kind we have in this appeal, e.g. by use of an appropriate overbid or uplift, or a revenue-based method (e.g. percentage of gross receipts), or perhaps a percentage or amount related to outgoings, to reflect a socio-economic or cultural motivation to occupy, so long as all relevant considerations are taken into account and weighed.”

38. Indeed, the absence of evidence to support such a modification was seen as something of a missed opportunity:

“223. Neither expert considered alternative approaches to valuing by reference to trading potential, such as an overbid or a percentage of revenue…

By not exploring such alternatives we think the experts failed to consider properly the totality of the circumstances and conditions under which RAMM was occupied and therefore did not fully consider the value of the occupation to the hypothetical tenant.”

39. Despite that lack of exploration the Tribunal acknowledged that the RAMM had a socio-economic value, but concluded that there was no evidence to support the idea that it would give rise to an overbid from the occupier. At paragraph 225 the Tribunal emphasised that what is relevant to rateable value is value to the occupier itself, rather than value to the public:

“the fact the socio-economic and cultural benefits were enjoyed by the public generally and not just by RAMM was legally relevant. But we must keep firmly in mind the principle that it is the value of the occupation of the hereditament to the hypothetical tenant that determines the rateable value. In our judgment, although economic advantages for businesses and persons in a district, city or region which do not benefit the occupier of a hereditament financially may nevertheless hold some value for that occupier, they do not generally have as much value as those that do. The figures relied upon by Mr Singh QC were essentially generalised benefits throughout the local economy and not sums of money receivable by the Respondent. Such benefits do not equate to value to the occupier resulting in an increase in the rent he would be prepared to pay, pound for pound. In the circumstances of this appeal, they do not hold the same value to the Respondent as revenues it may earn through its occupation of the hereditament.

The appellant’s case in the present appeals

40. It is against this background that the VO formulated his approach to these appeals. At first sight they have a remarkably similar factual background to that of Exeter Museums. All three museums make no charge for admission, and operate at a deficit, albeit a less dramatic one than that suffered by the RAMM (see paragraphs 10 and 29 above). In each case there is only one tenant in the market, namely the actual occupier. It is agreed that a receipts and expenditure valuation of each of the three yields a nominal rateable value. It is fair to say that if the VO is to achieve a different outcome from that in the Exeter Museums he will have to produce something of a rabbit from the valuation hat.

41. Mr Reynolds told us that the facts of these appeals are “starkly different to those in Exeter”. By that he meant, if we have understood correctly, that the lower deficit in the case of each of the three museums, together with the evidence he adduced of their socio-economic value, mean that they have a positive rateable value. He argued that the VTE had ignored what the Tribunal said in Exeter Museums, namely, that it was established practice to consider an overbid and there could be no objection in principle to the use of valuation judgment to assess whether the value of any relevant socio-economic benefit might give rise to a positive rateable value.

42. The VO’s case is this: that the receipts and expenditure method, without more, does not represent the rateable value of these three hereditaments because it is premised on their commercial potential. These hereditaments are occupied by the relevant local authorities - which exist to benefit the public - for socio-economic reasons, and if their socio-economic benefits are assessed and balanced against their running costs they can be seen to have a positive rateable value.

43. Crucial to Mr Reynolds’ argument is that the methodology for the assessment of socio-economic value has moved on in the last few years, so that he was able to adduce additional evidence to supply what was missing in Exeter Museums.

The arguments for the appellant

(1) The occupier’s socio-economic motivation

44. It was common ground that the local authorities have a socio-economic motivation for their occupation of these museums. Mr Reynolds referred to Ms Reynolds-Sinclair’s evidence; she said:

“I and the Respondent are more concerned with the ‘socio’ impact of what we do rather than any economic impact which it might create… The Respondent is a mission driven not for profit organization, our mission is to help people determine their place in the world and define their identities, so enhancing their self-respect and their respect for others. As such it prioritises social impact.”

45. In 2006/7 the Treasurer’s Report and Accounts for TWAM (then known as “TWM”, Tyne and Wear Museums Services), said at its paragraph 9.2:

“TWM … remains true to its beliefs that: We make a positive difference to people’s lives; We inspire and challenge people to explore their world and open up new horizons; We are a powerful learning resource for all the community…; We act as an agent of economic regeneration and help build and develop communities and the aspirations of individuals.”

46. Mr Reynolds argued that the local authority’s motivations for occupation of the museums have to be taken into account in assessing rateable value; it is not driven by profit or by its own economic benefit. It places value on others deriving social and economic benefit from its activities in a broad sense. It is the only tenant in the market, imagined by the rating hypothesis, for these purpose-built museum buildings but the landlord is not powerless in the imaginary negotiation; the tenant has reasons for wanting to continue to occupy. However, as it is the only potential occupier its ability to afford the proposed rent is relevant.

(2) the assessment of socio-economic value

47. In order to explain how socio-economic value can be assessed, Mr Reynolds called Dr Daniel Fujiwara who is Chief Executive Officer at Simetrica-Jacobs and a Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He used the term “social value”, rather than “socio-economic value” for consistency with HM Treasury Green Book (2020), which describes best practice in social value measurement and is used in assessing proposals for public spending, taxation and changes to the use of public assets and resources. It says:

“The appraisal of social value, also known as public value, is based on the principles and ideas of welfare economics and concerns overall social welfare efficiency, not simply economic market efficiency. Social or public value therefore includes all the significant costs and benefits that affect the welfare and wellbeing of the population not just market effects.”

48. Dr Fujiwara explained that social value measures the impact of an activity on people’s wellbeing, and that it includes economic impacts (for example on jobs), environmental impacts (such as carbon emissions) and wider societal impacts (health, crime, culture and education). [1] The key framework for understanding the different elements of social value is the Total Economic Value (“TEV”) framework, which analyses it in terms of use value and non-use value. Use value comprises direct use (visiting a museum), indirect use (the enjoyment of the museum café or shop), and option value (knowing one can visit the museum in the future). Non-use value comprises existence value, (knowing the museum exists), bequest value (knowing that it will be available to future generations) and altruistic value (knowing that the cultural institution is available to other people alive today). These are all primary impacts, which can be financial or non-financial. Secondary impacts are “spill over effects”, usually financial in nature, such as improvements in mental health which benefit the taxpayer by reducing health care costs. TEV focuses on the benefits to individuals including visitors to museums, the taxpayer, employees, and local businesses - all of which, he said, coincide with the interests and objectives of local authorities although they are not benefits to the museum per se.

49. Dr Fujiwara went on to consider the various methods of measuring use and non-use value. Crucial to them is an assessment of willingness to pay; at the hearing he explained in very helpful detail how realistic information can be derived from visitor surveys which ask people how much they would pay to visit the museum if it charged an admission fee, as a measure of the value they attribute to what the museum has to offer.

50. Social value analysis and data are used by the Government to determine what projects to invest in for the good of society. Obviously, value has to be balanced against cost, and obviously a benefit cost ratio greater than one would signify that a proposal would create more social value than it costs; a benefit cost ratio equal to or greater than 4 is regarded as very high.

51. Turning to the specifics of social value for museums, Dr Fujiwara acknowledged the use of the Association of Independent Museums toolkit (“the AIM toolkit”) by museums to estimate their economic impact on the local economy, often as a way of attracting grant funding. However, according to Dr Fujiwara the AIM toolkit differs from social value analysis, which is conducted at national level, because it focuses only upon effects on the local area. Social value also estimates a much broader set of outcomes including healthcare expenditure savings, enjoyment, learning and knowledge benefits. Finally, the AIM Toolkit only covers positive impacts whereas social value must take into account negative impacts (although Dr Fujiwara was unaware of any study of museums that has done so). In summary, the AIM toolkit covers a narrower subset of social value in relation to the economic impacts of museums and does not cover all of the elements recommended in the HM Treasury’s Green Book.

52. Dr Fujiwara explained that Simetrica-Jacobs has collected research reports for a series of arts, culture and heritage institutions and put together the Culture and Cultural Heritage Capital Evidence Bank. The Arts Council for England (“the ACE”) has produced step-by-step guidance on how museums can use the Evidence Bank in business cases to secure funding.

53. So although Dr Fujiwara did not provide an assessment of the socio-economic value of the three museums involved in these appeals, he provided a method for doing so which takes in all the elements of socio-economic value in accordance with current research and economic theory and consistent with the HM Treasury Green Book. Material from the Evidence Bank was annexed to his report for the use of the parties to the appeal in conjunction with information specific to the appeal properties themselves such as visitor numbers and the number of residents in their area.

(3) The valuation evidence: Mr Allen’s first report

54. It will be recalled that the VO’s case is that the receipts and expenditure method does not itself provide the answer to rateable value where the motive for occupation is not economic, and that it has to be supplemented by consideration of the socio-economic value of the hereditament. That value therefore has a place within, and supplements, the valuer’s more traditional methodology.

55. Mr Reynolds called Mr Justin Allen MRICS as an expert witness. He has been employed by the VOA since 1987 and currently works in the National Valuation Unit specialising in the rating valuation of classes of property not commonly let at a rent in the open market.

57. He looked first at ten comparable properties. Very few rented comparables are available; most museums are freehold or held on long leases with a peppercorn rent. There is no market and very little evidence of demand for new lettings. But Mr Allen took us through a range of properties which demonstrate that demand and provide examples of direct and indirect investment in museums by the payment of rent, capital investment in improvements, substantial investment in extensions, and new museums. He did not claim that this evidence was going to provide the answer, only that it could inform valuer judgement.

58. We do not propose to rehearse the comparables here. They included the Castle Museum at Abergavenny, the Bath Postal Museum, Chard Museum, the Museum of Carpet at Kidderminster and the Museum of Cambridge, all significant local rather than national institutions. Mr Allen demonstrated that the payment of rent and operation at a deficit are not mutually exclusive. The rents paid were in the range of £1,989 and £9,000 per annum, and there was no discernible relationship between the rents and gross receipts or the rating assessments. In some cases a surplus was being achieved and rents were being paid. In other cases that was not so. To take just a couple of examples, the Ashby de la Zouche Museum is occupied on a 25-year lease from 2006 at an initial rent (funded by the local authority) of just over £8,000 per annum; in 2007/8 it produced a surplus of £139. The Museum of Bath at Work is a much bigger museum, held on a full repairing and insuring lease for 30 years from 2003; the rent in 2008 was £7,500 per annum. In the year ending 31 January 2008 the museum incurred a deficit of £11,870.

59. In cross-examination Mr Allen agreed that of his ten comparables, one was not an arms-length lease; in two cases it was not known whether or not the museum made a profit; four were making a surplus. So of the ten, only three could support his reasoning, out of the many thousands of museums in the country.

60. Mr Allen then turned to the receipts and expenditure method, which he regarded as useful where the occupier trades at a profit. The receipts and expenditure calculation agreed by the parties and used by the VTE in these appeals yielded a nominal valuation even though it included notional receipts (that is, admission charges that are not in fact made); yet that outcome, he suggested, is ‘clearly at odds with the reality’ that some museums are occupied for a substantive rent even though they are not occupied with a view to profit.

61. Mr Allen argued that that reality is explained by the fact that an overbid is being paid.

62. In order to assess that overbid, in his first report, Mr Allen turned to what he described as the ‘well established and accepted methodology’ of adopting a percentage of gross receipts. In support of his approach Mr Allen relied upon two agreements relating to the The Historic Dockyard, at Chatham and the Mary Rose Museum at Portsmouth. These had been agreed at 2.5% of fair maintainable trade and 2.5 % of gross receipts respectively.

63. Mr Allen also referred to the decision of the Tribunal in York Museums and in particular to the Heritage Centre, where the Tribunal's determination of the rateable value at £10,000 was “clearly informed by the (notional) gross receipts” (being 9.3% of gross receipts) - although he stressed that the Tribunal had not expressed its decision in those terms. He said, “The Tribunal’s approach to the Heritage Centre reflects the pragmatic valuer judgement applied to the valuation of an unusual property taken by surveyors both in the hypothetical world of rating and real world of the landlord and tenant transactions.” He went on to set out details of several properties where he had analysed passing rents in terms of a percentage of gross receipts and these varied between 4.4% and 45%; after removing the significant outliers from his sample he concluded that they demonstrated a range of percentages from 4 to 15%, notwithstanding that none of his sample had a ratio as low as 4%.

64. Finally in his first report Mr Allen turned to the museums’ requirement for storage. It is not in dispute, and we observed ourselves, that museums typically display only a small proportion of their collections and need considerable storage space, perhaps 25% of the building. That being the case Mr Allen felt that it would be useful to see the rental value of such storage as an analogy, and for that purpose agreed with Mr Hunter a storage rate of £35 per square metre. On that basis, 25% of the gross internal area of the Laing Museum has a rental value of £40,434; of Shipley, £17,045; and of South Shields, £11,961.

65. The material set out above led Mr Allen to conclude his first report by adopting the following valuations:

Laing Gallery: £46,800 (5% of gross receipts, taking into account its location and architecture)

Shipley Gallery: £3,500 (2.5% of gross receipts, reflecting location and lower visitor numbers)

South Shields: £12,945 (3% of gross receipts reflecting higher admissions than Shipley and a lower deficit).

(4) The valuation evidence: Mr Allen’s second report

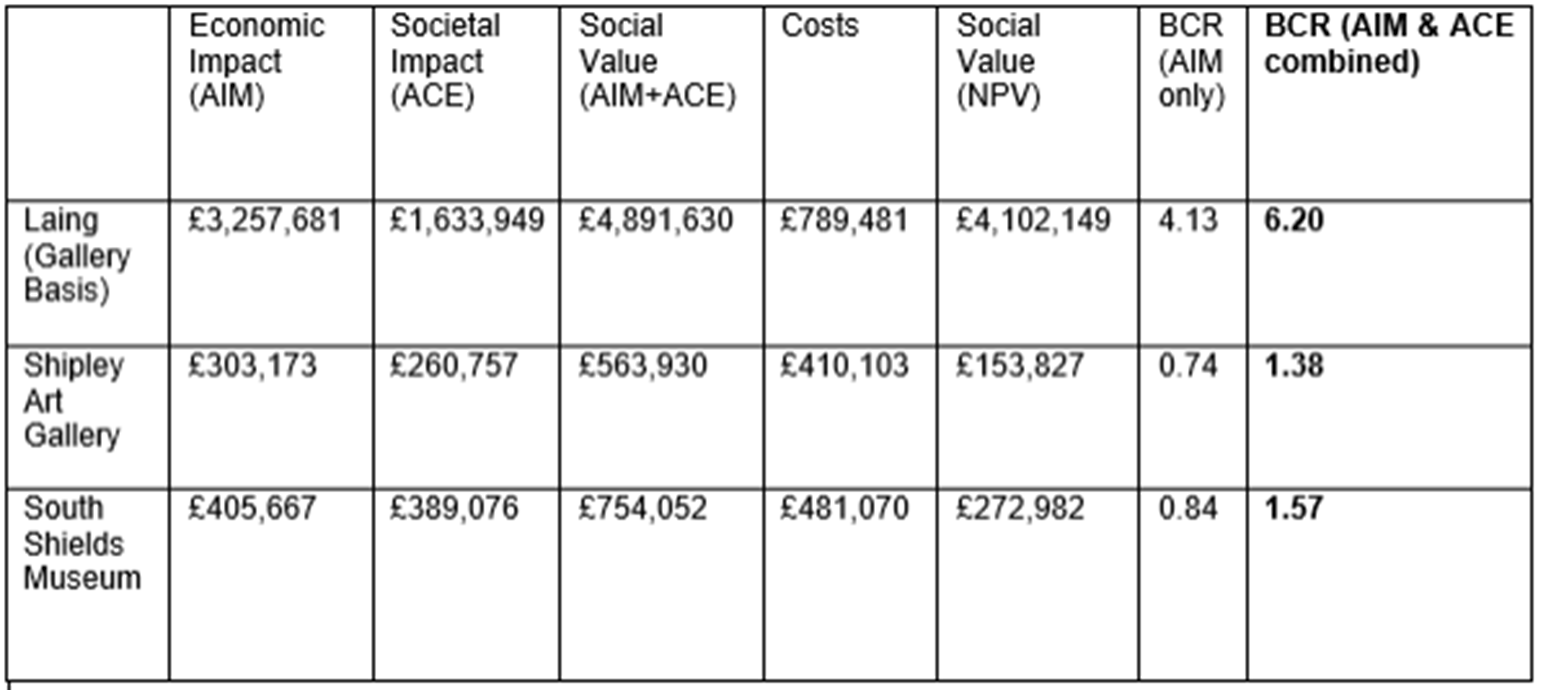

66. Mr Allen filed a supplemental report on 21 April 2022, after reading Mr Hunter’s report and with the benefit of Dr Fujiwara’s report. He made an assessment of the socio-economic value of the three museums, using both the AIM Toolkit (see paragraph 51 above) and Dr Fujiwara’s methodology with the assistance of the ACE guidance (paragraph 52 above), taking on board Dr Fujiwara’s view that that guidance was designed for use by lay persons without expertise in quantifying socio-economic benefit. His results are set out in the table below.

67. In the table Mr Allen has labelled the result from the Toolkit as “Economic Impact” and that from the ACE guidance as “Societal Impact; we do not think that is correct, since according to Dr Fujiwara the AIM Toolkit measures socio-economic benefit but looks at a narrower range of benefits than does the ACE guidance; but nothing turns on that. Mr Allen’s table adds the costs associated with each museum so that the benefit cost ratio can be seen.

68. If Mr Allen’s proposed rateable values (from his first report, see paragraph 65 above) are added to the costs of each museum, the resulting benefit cost ratio becomes 5.85 for the Laing Gallery, 1.36 for the Shipley Gallery and 1.53 for South Shields.

69. Mr Allen then turned again to the issue of affordability. He rejected the idea that amongst all the other costs of running a museum, a hypothetical tenant would object to the idea of paying a rent. He took the view that there are significant differences between the appeal properties and those considered in the York Museums and Exeter Museums decisions. To take just one example, the VO’s proposed rent for the RAMM of £690,000 would have represented a 45 - 50% increase in the total annual net budget for that museum. By contrast in the present case, Mr Allen was able to look at his proposed rateable value as a percentage of the museum’s deficit in 2007/8, and as a percentage of the relevant local authority’s total revenue expenditure for 2012/13 (the earliest publicly available date):

|

|

Proposed RV |

% of deficit |

% of local authority net revenue expenditure |

|

Laing Gallery |

£46,800 |

5.9% |

0.00017% |

|

Shipley |

£3,500 |

0.8% |

0.00001% |

|

South Shields |

£12,900 |

2.7% |

0.000058% |

70. Mr Allen observed that in the years following the AVD the three museums had undergone significant cost-cutting exercises, including staff reductions and reduced opening hours (see the evidence of Ms Sinclair-Reynolds and Ms Ollerhead, below), which could not have been foreseen at the AVD or the Material Date; he rejected the idea that rent would have been the straw that broke the camel’s back. He demonstrated that at the AVD TWAM’s budget and the constituent local authorities’ contributions were increasing from year to year (before the 2010 austerity budget); the hypothetical tenants had the capacity to pay the rents he proposed.

(5) Mr Reynolds’ arguments about social value

71. We revert now to the legal argument.

72. Mr Reynolds relied upon the “significant net socio-economic value” revealed by Mr Allen’s calculations. He added a very important point:

“£1 of net socio-economic value will not equate to an increase of £1 in the RV. Similarly, it is likely that socio-economic value will not increase the rent to the same extent as would financial profit under R and E. The VTE… determined that between 30-40% of the divisible balance would be made available as rent …As can be seen from [Mr Allen’s calculations] the proposed RV is a far lower proportion of the net socio-economic value.”

73. He added that:

“Local authorities have expansive motivations and objectives to broadly promote education, community, economic and social success in their area. It is wrong to see the generation of social value as benefiting people within the area or region, rather than the local authority occupier. In generating social value for the people within its region the museum will be generating social value for the local authority occupier.”

(6) Further argument about the storage analogy

74. Mr Reynolds developed the argument about the storage analogy by considering the potential storage costs that the hypothetical tenant of the museums would face if it chose not to take a lease of the hereditaments:

“If museums ceased to occupy their existing buildings, they would be forced to choose between closing down permanently and disseminating their collections or putting the collections into storage in the hope of identifying some way of keeping them accessible to the public in the local region. There is good reason to believe that having worked so hard to establish the museums service in the North-East the local authorities would not readily surrender their works to the National Collection, other institutions … or back to their original owners”.

75. Mr Reynolds added that the relevance of this was not that storage costs would directly correspond to rateable value, but that the need for and cost of storage would be a factor that the occupier would take into account.

The arguments for the respondent

(1) The respondent’s case

76. It was the respondent’s case that there are no valuation methods for measuring the socio-economic benefit as a benefit to the occupier, nor any evidence that a museum occupier would pay rent to obtain that benefit, nor that the actual occupiers in this case would be willing or able to pay a rent over and above the funding already necessary to keep operating the museums at a loss. The only reliable method of valuation for the appeal properties is the receipts and expenditure method; and even on a notional receipts basis that method yields a nominal rateable value.

(2) Valuation evidence for the respondent

77. Mr Colin Hunter MRICS IRRV (Hons) appeared as an expert for the respondent. He is a Divisional Director in the Leeds office of Lambert Smith Hampton. He has extensive experience of valuing museums and advises the Museums Association and the National Museums Directors Council.

78. Mr Hunter’s report, like Mr Allen’s first report, was written in December 2021 when Dr Fujiwara had not yet been instructed.

79. Like Mr Allen, Mr Hunter discussed a number of comparable properties but he stressed that they are unusual; most museums are freehold or held on a long peppercorn lease. His view was that rent is paid when the property is capable of generating a surplus and the key to willingness to pay is therefore affordability.

80. As to receipts and expenditure, he agreed that even with a notional income the outcome at these three sites is a nominal rateable value.

81. Mr Hunter then turned to the consideration of a possible overbid, and to that end he used the 2019 edition of the AIM Toolkit (see paragraph 51 above) as a measure of socio-economic benefit. The toolkit relies upon visitor numbers and notional receipts as a measure of benefit; a percentage of that benefit - which Mr Hunter thought might be 1% to 2.5% - would represent the overbid (yielding a benefit cost ratio between 1:100 and 1:40). However, he then subtracted the contribution already being made by the local authority to ascertain whether any contribution it has made to eliminate a deficit would equate to or outweigh the overbid that socio-economic benefit justifies.

82. Mr Hunter arrived at the following net overbids:

The Laing Art Gallery -£621,462

Shipley Art Gallery -£431,007

South Shields Museum and Gallery -£487,139

83. His conclusion was that none of the three councils supporting these TWAM sites would make an overbid to increase the running costs when the benefits are so small.

84. That calculation was hotly contested by Mr Allen in his second report and in cross-examination at the hearing.

(3) Legal submissions about valuation

85. Mis Wigley QC cited London CC v Churchwardens of Erith [1893] AC 562, at 591:

“… the whole of the circumstances and conditions under which the owner has become the occupier must be taken into consideration, and no higher rent fixed as the basis of assessment than that which it is believed the owner would really be willing to pay.”

86. Miss Wigley QC did not dissent from the proposition that these museums are occupied, and funded, by the local authorities for their socio-economic value. But it remains the case as the Tribunal said in Exeter Museums (at paragraph 225) that there is no currently recognized method for expressing the valuation impact of socio-economic benefits on rental value. There is no evidence that rent paid for any of the comparable properties referred to by either of the experts was agreed by the tenant because of the museum’s socio-economic value. In almost all cases where rent is paid there is a surplus. And there is no evidence or methodology connecting any perceived overbid with an assessment of socio-economic value.

87. Miss Wigley QC expressed disquiet at the use of gross receipts (the shortened method; see paragraph 26 above) where there is no body of evidence derived from comparable properties. In any event the use of a percentage of gross profits to make that connection is arbitrary. Miss Wigley QC cited Hoare (VO) v National Trust [1998] EWCA Civ 1525 where Schiemann LJ said at paragraph 51:

“I content myself with recording my total inability as at present advised to understand the theoretical justification for arriving at the amount of the overbid by starting at the gross receipts figure rather than a profit figure. The fact that one can adjust the percentage of that gross receipts figure in order to arrive at the hypothetical rent does not detract from the arbitrariness of starting with that gross figure. Moreover the amount of the percentage reduction seems to me equally arbitrary. The resulting valuations give a wholly misleading picture of scientific rigour. One suspects that what the valuer does is to use his evaluation of all the facts of the case and arrive at an intuitive figure and then build a theoretical structure to justify it. I cannot see any rational hypothetical tenant, who (unlike the Trust) is prepared to make an overbid, using that theoretical structure to arrive at the amount of his overbid in his negotiations with the hypothetical landlord. Nor can I see the hypothetical landlord having such calculations in mind.

88. Miss Wigley QC observed that Mr Allen’s gross receipts figures were calculated in his first report without the benefit of any calculation of the museums’ socio-economic value, although that value then became an ex post facto justification for the figures.

Affordability

89. It was the respondent’s case that rent would not have been affordable for these museums at the AVD.

90. Miss Wigley QC called Jacqueline Reynolds-Sinclair, Head of Finance, Governance and Resources at TWAM gave evidence on behalf of the respondent. She is an accountant by profession and a member of the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy. Ms Reynolds-Sinclair provided a detailed overview of the funding and operation of TWAM and of the three museums, explaining that funds derive from the local authority constituents of TWAM, from Newcastle University, and from the Arts Council. The museums have to bring in 20% of their budget through fund-raising, catering, charging for some services, bequests and so on. The buildings are listed, and any necessary work on them is delayed until it is absolutely necessary; there are no funds for preventive maintenance.

91. Ms Reynolds-Sinclair explained that between 2005/6 and 2008/9 costs had not reduced but income had declined. Approximately 67% of TWAM’s expenditure was on staff, 20% on buildings and 13% on services. This split has created difficulties for TWAM because the structure of its funding means that it is not possible to close museums; if one museum were to close then the relevant local authority and Newcastle University would expect its funding to be returned.

92. Since 2010, in response to declining funding, staff numbers had been cut, reductions in building maintenance had occurred and shortened opening hours were introduced. Visitor numbers across all three sites declined in the period 2006 to 2009. The museums are wholly reliant on grant funding, and the affordability or otherwise of rent would be entirely dependent on additional fundraising or on an internal reallocation of expenditure which would have impacted on another part of the service.

93. Ms Reynolds-Sinclair acknowledged that the motivation for the operation of the museums is the generation of socio-economic benefits; the museums are already funded by the local authorities and the Arts Council in order to generate that benefit. TWAM does not and would not pay a rent to reflect that benefit, because that benefit does not generate an income that would fund a rent.

94. Miss Wigley QC also pointed out that the hypothetical landlord would be aware of the loss-making nature of the museums, and of the local authorities’ motivation and of their cash-strapped position. The landlord would also be conscious of the repairing liabilities for these listed buildings and would be keen to have a tenant take them on. A peppercorn rent would be the realistic outcome.

The storage analogy

95. Miss Wigley QC called Lisa Ollerhead, Chief Executive of the Association of Independent Museums. She discussed the difficulties that face museums in managing their collections when they cannot be placed on display, either because they are not suitable for display or because a building has temporarily or permanently closed. Storage may be the only option, although there are alternatives. For example, objects may be loaned for temporary exhibition elsewhere. But museums do not pay for storage because they cannot afford to do so. It was established in cross-examination that that is not a universal rule.

96. Miss Wigley QC argued that to value the museums by reference to storage costs contravenes the principle that the hereditaments are to be valued in their existing mode and category of occupation, as museums. As to the hypothetical tenant’s motivation, the required assumption is that the premises are vacant and to let. The tenant is not already there. Either it has not yet acquired a collection or it will be in storage, or it may be intending to exhibit items owned by others.

97. She also pointed out that there is no correlation between the storage values put forward by Mr Allen and the proposed rateable values.

Discussion and determination

98. The crux of the VO’s case is that the socio-economic value of the three museums is measurable and would inform the rental bid of the hypothetical tenant leading to a positive rateable value, which can be calculated as a percentage of gross receipts. Such a rent would be affordable; it is consistent with reality, as can be seen by the rents paid for comparable properties, and it is not wholly out of kilter with the storage value of 25% of the gross internal area of the three museums.

99. We can address the peripheral points before we come to the central point.

Affordability

100. We accept that TWAM, or its constituent local authorities, was not insolvent at the AVD and therefore could have paid a rent. It could equally have chosen to pay for many other things that it was not paying for at the time. But if it paid a rent or undertook any other new financial commitment it would have cut something else back. In 2008 the local authorities were not as hard-pressed as they were after 2010, and if they had been forced to pay rent for these museums that would probably not have led to their closure. But that does not tell us that the hypothetical tenant would have agreed to pay rent. The local authorities have many competing demands on their budgets; museums are important but they are unlikely to have been first in the queue for additional resource, particularly as they were already being subsidised. The hypothetical landlord knows all this. Rent would be affordable, but that gets us nowhere.

101. The function of argument about affordability, where there is only one potential tenant, is that it serves to rule out unaffordable rents. If a rent is unaffordable it is ruled out because the hypothetical tenant could not pay it. But if a rent is affordable, that does not mean that it is the rent that the hypothetical tenant would agree to pay, and so the affordability of rent takes matters no further.

Storage

102. The “storage analogy” generated a great deal of discussion and challenge. Yet it is well-established that these hereditaments have to be valued as museums and not as storage facilities, and neither Mr Allen nor Mr Reynolds suggested otherwise.

103. The storage “analogy” was used, we think, in two ways. Mr Allen in his first report used the storage value of 25% of the gross internal area of the museums as a point of comparison; he sought to draw attention to what the storage areas in the museums were in fact worth to the hypothetical tenant, so that that value could stand as something of a sense-check for the eventual valuation. The use of 25% of the area seemed to us to be arbitrary; far more importantly, we do not think that the use of storage value as an analogy or a sense-check in this way is a permissible approach; it comes too close to valuing these hereditaments in a different mode or category than that of museums. They have to be valued as museums and as a whole; looking at the value of just one part of what their internal space is used for is bound to yield unrealistic results and a false analogy.

104. Mr Reynolds took the storage point further and argued that the cost of storage would be in the mind of the hypothetical tenant, who has to store the collection somewhere. This too is beyond the scope of the hypothetical letting and we accept Miss Wigley QC’s argument that the premises are vacant and to let and the hypothetical tenant does not yet have a collection to house.

Valuation using gross receipts

105. Mr Allen calculated rateable value using a percentage of gross receipts. The Tribunal has considered the so called ‘shortened method’ on a number of occasions and recently identified its shortcomings in BNPPDS Limited & BNPPDS Limited (Jersey) as Trustees for BlackRock UK Property Fund v Andrew Ricketts (VO) [2022] UKUT 129 (LC). This ‘method’ is in our view only appropriate after a rigorous analysis of the available rental evidence, or a significant number of assessments agreed on the full receipts and expenditure basis. Although the experts had a number of rents to inform their judgement, none were capable of reliable analysis, and we had no evidence of full receipts and expenditure valuations on comparable properties. So the use of the shortened method has to be regarded with extreme caution in this case.

Socio-economic value

106. So we come to the central point.

107. We make no comment on the accuracy or otherwise of Mr Hunter’s use of the AIM Toolkit. It is clear that there is room for considerable argument about how it is used and there would be no purpose in our attempting to resolve that. Nor can we comment on the values generated by Mr Allen from the ACE guidance on the basis of Dr Fujiwara’s evidence, nor on what Dr Fujiwara himself told us. These museums have a socio-economic value, and Dr Fujiwara’s methodology is the most up-to-date method of putting a figure on it and is based on an impressive foundation of research. We accept that it values a wider range of benefits than does the AIM Toolkit. It is startling that the values generated by Mr Allen’s calculation differ so dramatically from those generated by the AIM Toolkit, and that indicates to us that there is scope for considerable disagreement about how both these calculations are executed. Again, there would be no point in our investigating or resolving that in view of what we say in the following paragraphs. We accept that the ACE guidance is the industry standard for compliance with the HM Treasury Green Book requirements for measuring social value, for the purposes of public expenditure and also for use by museums in applying for funding.

108. There are two difficulties with using it to calculate the rent that the hypothetical tenant would pay.

109. The first is that the figures generated by the ACE guidance represent value to as many people as possible. The methodology aims to maximise value by capturing as much of it as possible, at a national as well as a local level, in order to inform not only national government spending but also to attract the generosity of grant providers. It is not concerned with the specific value of a museum to its local authority. Of course, the local authority funds its museum in order to generate socio-economic value, but there is no methodology available to translate that social value to the public into value to the local authority itself. This is more than a theoretical point; it is fundamental to the rating hypothesis.

110. Second, there is no methodology available to translate that value to the local authority into willingness to pay any rent at all, let alone how much, on the part of the local authority. Mr Allen offered none. His initial argument was that since some museums pay rent despite making a loss, there must be an overbid representing a payment for social value. But that inference is not based on evidence. It is not obvious to us at all that where rent is paid for a museum that operates at a deficit the reason for that rent is an overbid based on socio-economic value. There may be all manner of reasons why that rent is paid and we are not going to speculate. Furthermore, the sample of comparable properties is too small, there is far too little evidence available for each property, and what evidence there is would appear to indicate that none of the properties in the sample is particularly comparable either to the other “comparables” or to the appeal hereditaments. Having made that inference Mr Allen chose a percentage of gross profits to represent the overbid that is assumed to be paid, but there is no reason why - even if it is accepted that the hypothetical tenant would agree to make an overbid - Mr Allen’s figure should represent it.

111. Later in the proceedings Mr Allen was able to calculate a figure for socio-economic benefit. But his rateable values did not change. They cannot because there is no way to derive value to the occupier from socio-economic benefit, and no way to derive the amount of the overbid from the value to the occupier.

112. We remain stuck, two steps away from a rateable value, because the value of the socio-economic benefits generated by these three museums does not tell us their value to the hypothetical tenant; nor does it tell us anything about the rent that the hypothetical tenant would be willing to pay for the hereditament in order to obtain that value.

113. We doubt that those two steps are able to be taken. Certainly there is no methodology available at present to achieve either. And whilst we understand how the socio-economic value of a museum to the public can be quantified, we do not understand how it is possible to quantify the value to the local authority of that public benefit. There is no rental market in which local authorities’ willingness to pay can be demonstrated; from the few transactions that involve a rent, no useful evidence can be gleaned as can be seen from the “comparables” provided here. And whilst there has been extensive research of the public’s willingness to pay for visits to museums which are currently free, there has been no such research of local authorities’ willingness to pay rent, which is perhaps unsurprising.

114. Obviously local authorities pay for socio-economic value by funding museums; but there is no evidence from which we can conclude that the hypothetical tenant local authority would pay rent for these museums in addition to the funding and support they already provide.

115. Accordingly the factor that is supposed, on the VO’s case, to generate a different outcome for these appeals from the Tribunal’s decision in Exeter Museums cannot do so. The VTE was correct that there was no material on which it could use anything other than the receipts and expenditure method, which it is agreed generates a nominal rateable value. The appeals fail.

Judge: Elizabeth Cooke Member: Mr Mark Higgin FRICS

3 August 2022

Right of appeal

Any party has a right of appeal to the Court of Appeal on any point of law arising from this decision. The right of appeal may be exercised only with permission. An application for permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal must be sent or delivered to the Tribunal so that it is received within 1 month after the date on which this decision is sent to the parties (unless an application for costs is made within 14 days of the decision being sent to the parties, in which case an application for permission to appeal must be made within 1 month of the date on which the Tribunal’s decision on costs is sent to the parties). An application for permission to appeal must identify the decision of the Tribunal to which it relates, identify the alleged error or errors of law in the decision, and state the result the party making the application is seeking. If the Tribunal refuses permission to appeal a further application may then be made to the Court of Appeal for permission.

[1] Dr Fujiwara added that the term “socioeconomic benefit” is used to describe a sub-set of these values, excluding the environmental benefits. That is not the sense in which we use that term; as we said, we use “socio-economic value” (or benefit) as a synonym for social value (paragraph 35 above).