Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Nathwani & Anor v Kivlehan & Ors (RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - modification - restricting building to single storey dwelling house) [2021] UKUT 84 (LC) (22 April 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2021/84.html

Cite as: [2021] UKUT 84 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2021] UKUT 84 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LP/29/2019

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - modification - covenants restricting building to single storey dwelling house - planning permissions for two/three storey modern house - whether covenants secure practical benefits of substantial value or advantage - s.84(1)(aa), Law of Property Act 1925 - application refused

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 84 OF THE LAW OF PROPERTY ACT 1925

|

BETWEEN: |

MR NILESH NATHWANI (1) MRS PANNA NATHWANI (2) |

|

|

|

|

Applicants |

|

|

and |

|

|

|

Mr Thomas Kivlehan and Mrs Karen Kivlehan (1) Mr Steve Powell (2) Mr Vu Nguyen and Ms Kim (3) Mr Simon Coussins (4)

|

Objectors |

|

|

|

|

Re: Southernhay,

Woodlands Road,

West Byfleet,

KT14 6JW

Mr A J Trott FRICS and Mrs D Martin MRICS FAAV

20-21 January 2021 by remote video platform

Mr Tom Weekes QC for the applicants, instructed by Mills & Reeve LLP

Ms Katharine Holland QC and Mr Admas Habteslasie for the objectors, instructed by Berkeley Rowe Solicitors

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2021

The following case is referred to in this decision:

Re Foggs’ Application [2018] UKUT 114 (LC)

Introduction

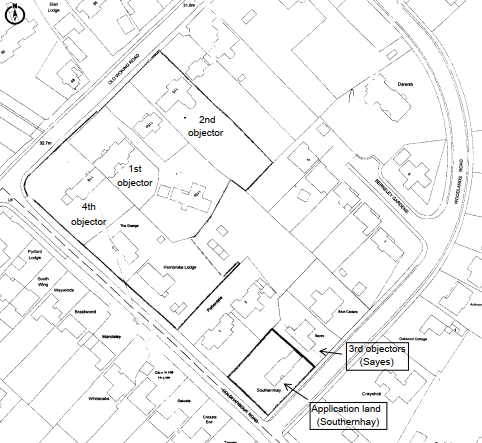

1. Mr Nilesh and Mrs Panna Nathwani (“the applicants”) are the freehold owners of a plot of land (“the application land”) on which stood, until mid-2017, a bungalow (“the bungalow”) known as Southernhay, Woodlands Road, West Byfleet, Surrey KT14 6JW.

2. The applicants obtained planning permission from Woking Borough Council (“WBC”) on 17 December 2015 (“the 2015 permission”) to demolish the bungalow and replace it with a house of modern design including a monopitch roof. The house was single storey at its north eastern end rising to three storeys to the south west. On 30 March 2017 the planning permission was varied (“the 2017 permission”) to authorise construction of a modified design, by which the height of the monopitch roof at the lower end was raised from 3.4m to 4.1m allowing a second storey at that end.

3. The bungalow was demolished in mid-2017 but the applicants are prevented from building either of the houses with planning permission by the existence of restrictions imposed by covenants dated 20 June 1966 (“the 1966 covenant”) and 22 February 1967 (“the 1967 covenant”) both of which restrictions limit development on the application land to a single private dwelling house of one storey only.

4. The 1966 covenant benefits the owners of certain properties which are located on Old Woking Road, now separated from the application land by other dwellings. It was contained in a deed of release and variation of an earlier covenant dated 21 November 1952 (“the 1952 covenant”). The 1952 covenant restricted development on land which included the application land, and two adjoining properties on Woodlands Road known as Sayes and Blue Cedars, to “…a single dwelling private detached dwellinghouse with garage…”. The 1966 covenant released that restriction so far as the application land was concerned and substituted a restriction of development on the application land to:

“one single private dwelling house of one storey only and usual outbuildings thereto.”

5. The 1967 covenant, contained in a conveyance, benefits the owners of Sayes and Blue Cedars. Only Sayes shares a boundary with the application land. The 1967 covenant states, insofar as relevant:

“… AND the Purchaser HEREBY COVENANTS with the Vendor to the intent that the burden of such covenant may run with the land hereby transferred and every part thereof and to the intent that the benefit thereof may be annexed to and run with the land of the Vendor edged with blue on the said plan annexed hereto and every part thereof to observe and perform the restrictions and stipulations following namely:-

(i) neither the Purchaser nor his successors in title to the land hereby transferred will erect or cause to be erected on the land hereby transferred any buildings or erections whatsoever other than one single-storey detached private dwelling house only…”

6. The applicants applied to the Tribunal on 12 December 2019 for modification of the restrictions on grounds (aa) and (c) of section 84(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

7. There were four objections to the application, from:

(i) Mr Thomas Kivlehan and Mrs Karen Kivlehan (“the first objectors”), freeholders of 117 Old Woking Road, West Byfleet who benefit from the 1966 covenant;

(ii) Mr Stephen Powell (“the second objector), freeholder of Barn End, 115 Old Woking Road, West Byfleet, who benefits from the 1952 covenant only;

(iii) Mr Vu Nguyen and Ms Kim Vo (“the third objectors”) freeholders of Sayes (“Sayes”), Woodlands Road, West Byfleet who benefit from the 1967 covenant;

(iv) Mr Simon Coussins (“the fourth objector”) of Milestones, 119 Old Woking Road, West Byfleet - who benefits from the 1966 covenant.

8. The applicants were represented at the hearing by Mr Tom Weekes QC, who called Mr Nathwani and Mr Paul Uttley as witnesses of fact, and Mr Bruce Maunder Taylor FRICS as an expert witness.

9. The first, second and fourth objectors did not take part in the hearing. The third objectors were represented at the hearing by Ms Katharine Holland QC and Mr Admas Habteslasie. They called Mr Nguyen as a witness of fact and Mr Christopher Magowan MRICS as an expert witness.

10. We made an unaccompanied inspection of the application land and Sayes on 17 March 2021. By that time a wooden frame had been erected on the application land, at the boundary with Sayes, which was said by the applicants to indicate the position and height of the end wall of the consented 2017 house. Tape was strung across to indicate the lower height of the 2015 house. The footprint of the consented house and of a proposed single storey alternative house were marked out with tape. The third objectors disputed the accuracy of the dimensions marked out, and it would have been more useful to us if these visual aids had been marked out by the parties or their expert witnesses in an agreed position. We also made roadside inspections of the properties belonging to the first, second and fourth objectors.

Factual background

11. The respective locations of the application land and the properties owned by each objector are shown on the plan below. The building shown on the application land is the bungalow and attached double garage which existed before demolition. The garage was at the north east end, adjacent to the boundary with Sayes, and had a hipped roof on that elevation.

12. The history of the conveyances of the plots, and the associated restrictions, is complicated, involving demolition of some earlier properties and reuse of property names in different plots. Careful study of the title documents, after the hearing, revealed that the property belonging to the second objector was included in the 1952 covenant, but had been sold away before the 1966 covenant was imposed and so does not benefit from the restriction imposed by that covenant.

13. The applicants purchased the application land in November 2014 for £742,842 and it was Mr Nathwani’s evidence that his intention was to redevelop it for profit, as one of several development projects that he has undertaken in recent years. The applicants employed Form Architecture to design a new house of contemporary design, and the project was led by Mr Paul Uttley, a chartered town planner. On 17 December 2015 Woking Borough Council granted planning permission, notwithstanding strong local opposition to the proposal as being out of keeping with the character of the local area and with policies in the emerging Pyrford Neighbourhood Plan (“the neighbourhood plan”).

14. In his witness evidence Mr Uttley explained that the siting of the new house on the plot was influenced by the location of several mature trees, on the western part of the plot, which were subject to an area tree preservation order. This led to the house being designed in an L shape with the main part of the house and new garage sitting over the footprint of the previous bungalow and garage, close to the boundary with Sayes to the north east. In the 2015 permission the design of the monopitch roof slopes from 8.9m high down to 3.4m at the north eastern elevation of the garage adjoining Sayes. The central part of the structure is two storey, but with provision for a second floor gallery/library at the highest end and a loft over a double garage at the lowest end. The construction materials include white rendered walls and large glazing panels.

15. The revised design, which gained planning permission on 30 March 2017, provided for an increase in height at the north east elevation to 4.1m, allowing a redesign of the first floor to incorporate the master bedroom above the garage, where previously there was a loft. In due course, contractors instructed by the applicants demolished the bungalow and marked out the footprint of the new house.

16. On 14 July 2017 solicitors acting for the third objectors gave notice of the 1967 covenant to the applicants’ solicitors and construction work was stopped. Negotiations took place between the applicants and the third objectors over possible repositioning of the proposed new house further from the boundary with Sayes, but no agreement was reached.

17. It was agreed by the two valuation experts in November 2020 that the market value of the freehold interest in Sayes, assuming that the 2017 planning permission had not been granted, was £1,200,000.

The law

18. Section 84 of the Law of Property Act 1925 provides, so far as is relevant:

“84(1) The Upper Tribunal shall … have power from time to time, on the application of any person interested in any freehold land affected by any restriction arising under covenant or otherwise as to the user thereof or the building thereon, by order wholly or partially to discharge or modify any such restriction on being satisfied-

…

(aa) that (in a case falling within subsection (1A) below) the continued existence thereof would impede some reasonable user of the land for public or private purposes or, as the case may be, would unless modified so impede such user; or

…

(c) that the proposed discharge or modification will not injure the persons entitled to the benefit of the restriction;

and an order discharging or modifying a restriction under this subsection may direct the applicant to pay to any person entitled to the benefit of the restriction such sum by way of consideration as the Tribunal may think it just to award under one, but not both, of the following heads, that is to say, either—

(i) a sum to make up for any loss or disadvantage suffered by that person in consequence of the discharge or modification; or

(ii) a sum to make up for any effect which the restriction had, at the time when it was imposed, in reducing the consideration then received for the land affected by it.

(1A) Subsection (1)(aa) above authorises the discharge or modification of a restriction by reference to its impeding some reasonable user of the land in any case in which the Upper Tribunal is satisfied that the restriction, in impeding that user, either -

(a) does not secure to persons entitled to the benefit of it any practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to them; or

(b) is contrary to the public interest;

and that money will be an adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which any such person will suffer from the discharge or modification.

(1B) In determining whether a case is one falling within section (1A) above, and in determining whether (in any such case or otherwise) a restriction ought to be discharged or modified, the Upper Tribunal shall take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permissions in the relevant areas, as well as the period at which and context in which the restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances.

(1C) It is hereby declared that the power conferred by this section to modify a restriction includes power to add such further provisions restricting the user of or the building on the land affected as appear to the Upper Tribunal to be reasonable in view of the relaxation of the existing provisions, and as may be accepted by the applicant; and the Upper Tribunal may accordingly refuse to modify the restriction without some such addition.”

The application

19. The applicants sought modification of the restrictions under the 1966 and 1967 covenants, to allow implementation of both the 2015 permission and the 2017 permission, under grounds (aa) and (c). However, Mr Weekes confined his submissions to ground (aa) as this sets the lower hurdle.

20. Once it had been established that the second objector did not benefit from the 1966 covenant, but continued to benefit from the unmodified 1952 covenant, the application was widened to seek modification of the 1952 covenant to allow implementation of the 2015 and 2017 permissions. Mr Weekes submitted that the construction of the original bungalow on Southernhay in the 1960s, along with the construction of Sayes and Blue Cedars houses in 2008 (replacing an earlier single house), meant that the benefit of the covenant restricting density could no longer be enforced. Moreover, in impeding the construction of houses under the 2015 and 2017 permissions it did not secure to the second objector any practical benefits of substantial value or advantage.

21. It was not disputed by the third objectors that the proposed use was reasonable nor that the restrictions impede that user. Submissions were therefore focused on the extent to which impeding the proposed use secures practical benefits to the third objectors and on the value or advantage to them of any such benefits.

22. Mr Weekes submitted that the judgement to be made on practical benefits secured by the restrictions is a comparative one, between the houses with the benefit of the 2015 and 2017 permissions and a prospective single storey house which would not be impeded by the restrictions. The applicants provided a design for an alternative single storey house (“the alternative house”) in a contemporary style similar to those with permission, which they said they would submit for planning permission should the Tribunal refuse their application. The house was designed in an L-shape with a wall 18.9 metres long running alongside the boundary with Sayes. This compares with a wall length of 8.16m metres in the 2015 and 2017 permissions.

23. Mr Nathwani gave evidence that, should we grant the application for modification, the new house would be built and sold on. Should we refuse the application, he and his wife would seek planning permission for the alternative house.

24. In cross examination about the negotiations he had had with the third objectors regarding a relocation of the proposed new house five metres away from the boundary with Sayes, Mr Nathwani stated that he had a lengthy meeting on the subject with his architects and was advised that it could not be done because of the protection zone required around the mature trees on the site.

25. Mr Nathwani conceded that the application land had been purchased with knowledge of the 1967 covenant, but as it was an old covenant he took the calculated risk that it would not be enforced, in view of the fact that all the surrounding properties were two storeys in height.

26. Mr Uttley spoke to the documents submitted with the two planning applications, including the substantial arboricultural method statement by Arbor Cultural, dated 26 October 2015, which underpinned condition 6 of the 2015 consent. The document provided a survey and classification of 13 individual trees and three groups of trees on the application land. The recommended work was limited to removal of one of the individual trees, crown lifting of four others and otherwise a retention of all existing trees and groups for screening and amenity.

27. In cross examination Mr Uttley was asked how the planning guidance provided by the neighbourhood plan, which was adopted by WBC on 9 February 2017, had been taken into account in drawing up the designs in the 2015 and 2017 permissions. He responded that when the application for the 2015 permission was in process the neighbourhood plan had not been adopted. The 2017 permission was for a minor material amendment to an earlier permission so the neighbourhood plan did not feature it the application.

Expert evidence for the applicants

28. Mr Maunder Taylor has been a chartered surveyor for over 40 years and is a partner in the firm of Maunder Taylor based in Whetstone, London, specialising in the valuation of residential and commercial property. He was instructed to report on the impact, on those benefiting from the 1966 and 1967 covenants, of modification to permit the 2017 house by comparison with a single storey dwelling such as the alternative house. He had inspected the application land in November 2018, June 2019 and August 2020. During the latter inspection he was able to gain internal and external access to Sayes.

29. Mr Maunder Taylor concluded that modification of the 1966 covenant would have no impact on the properties on Old Woking Road which benefited from it as they are separated from the application land by other buildings and trees. He also concluded that modification of the 1967 covenant would have no impact on the property Blue Cedars, which is located on the far (eastern) side of Sayes. His report therefore focused on the impact which modification of that covenant would have on Sayes, in particular on its amenity, by reference to the use and enjoyment of the garden and rooms facing the boundary with the application land.

30. The external south west wall of Sayes, which faces the boundary with the application land, is set back approximately 4.5 metres from the boundary fence. It contains ground floor windows to the study, kitchen and conservatory and a single first floor window to a bathroom. The 4.5 metre strip comprises a shrub border against the boundary fence, a strip of mown grass and a pathway against the house on which are sited a water butt, dustbins and a barbecue, together with gas and electricity meters. It is fairly described as a utility area. The main garden area to the north west of the house is somewhat shielded from the boundary with the application land by a glazed conservatory and mature trees and shrubs.

31. Mr Maunder Taylor surmised that Sayes was designed so that the amenity value would be derived from aspects looking away from the application land. He relied on drawings provided in Mr Uttley’s evidence, which had been submitted with the planning applications in 2015 and 2017, showing that light to the study and kitchen windows of Sayes would not be adversely affected by the height of either of the permitted houses. We will return to this evidence later.

32. Finally, following on from his observations on impact, Mr Maunder Taylor concluded that modification of the 1967 covenant to allow building of the 2017 house would have no adverse impact on the market value of Sayes. It was his opinion that in preserving the many mature trees and shrubs on the application land, the design provided valuable protection for neighbouring properties such that a high quality house of modern design and construction, whilst different from other properties in the immediate locality, would be of overall benefit to the area.

The objections

33. Mr Nguyen gave evidence that he and his wife had bought Sayes in September 2012, when the bungalow still existed on the application land. They had been attracted by the setting with plenty of space between neighbouring properties. When the applicants bought the application land in 2014, and applied to WBC for planning permission in 2015 to demolish the bungalow and build a house, the third objectors and many local residents lodged objections to that application. The chairman of the Pyrford Neighbourhood Forum had also contested the application on behalf of 37 local residents. The decision by WBC to grant permission in December 2015 was the subject of an official complaint in respect of the lack of independence of the contracted planning officer who oversaw the application and advised the planning committee.

34. My Nguyen explained the concerns he and his wife had when the application was made in November 2016 to vary the 2015 permission by increasing the height of the elevation against the boundary with Sayes. A planning officer had visited in March 2017 to take light measurements but, despite further objections, the application received permission on 28 March 2017. Mr Nguyen lodged a formal complaint, requested a review and eventually made a complaint to the Local Government Ombudsman, about various aspects of the application and decision making processes in 2015 and 2017. We saw evidence that the conclusion in each case was that there was no evidence of fault by WBC.

35. In June 2017 Mr Nguyen was made aware by a neighbour of the existence of the 1967 covenant and his solicitors informed the applicants of this in July 2017, at which point the bungalow had been demolished but all further building work stopped. Negotiations with the applicants took place to discuss the possibility of moving the proposed house further into the application land, away from the boundary with Sayes. No resolution was reached and the applicants proceeded with their application to the Tribunal for modification.

36. Ms Holland submitted that the practical benefits of substantial value and advantage secured to the third objectors by the restrictions were the protection of outlook, particularly from the study window, the protection of access to sunlight - for Sayes generally but especially the study window - and the protection of visual amenity.

37. Ms Holland used dimensions provided by Peter Huf Architecture, for Mr Magowan’s report, to compare the dimensions of the end wall of the 2017 house, at 4.14 metres high and 8.16 metres wide, with the previous end wall of the garage to the bungalow, at 2.14 metres high and 5.83 metres wide. She pointed out that the proposed new wall would also be closer to the boundary than the previous end wall of the garage and submitted that the combined effect of proximity, height and length would be substantial. Ms Holland referred us to two 3D models in video form, prepared for the third objectors by Peter Huf Architecture. These sought to compare the impact on Sayes, including the views from the study, kitchen and conservatory, of the proposed 2017 house and the original bungalow/garage. The models were not contested by the applicants, save to point out that they showed only built structures, without any of the existing trees and shrubs which screen the application land from inside the conservatory at Sayes.

38. Ms Holland explained that the impact on the study window was particularly important to Mr Nguyen, who spends some 10 hours per day in that room. The effect of the proposed house would be to replace the current view of sky and trees by “an imposing and incongruous solid wall”. She considered that the original bungalow was the logical point of comparison for judging the practical benefits secured to the third objectors by the restriction, and whether those benefits were of substantial value or advantage.

39. The proposed alternative house was, she submitted, of diminished relevance due to its lack of planning permission. Given the complaints which had resulted from the grant of the 2015 and 2017 permissions, arising especially from the lack of consideration of the character of the local area and the neighbourhood plan, Ms Holland submitted that the prospect of the applicants obtaining permission for the alternative house was doubtful.

40. Ms Holland submitted that the relevance of the alternative house was diminished further because plans showed its wall along the boundary with Sayes to be of similar height to the two storey end wall of the 2017 house; it also included a roof terrace, which suggested it could not be described as single storey.

41. The position of the third objectors was that ground (aa) had not been made out, even if the alternative house was the basis for comparison. The impact by comparison with the alternative house would be less severe than by comparison with the bungalow, but the 1967 covenant would nonetheless secure practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to them.

Expert evidence for the third objectors

42. Mr Magowan has been a chartered surveyor for 23 years and is director of Magowans (London) Ltd, based in Twickenham, Middlesex. He is an RICS Registered Valuer with further expertise in building disputes, leasehold reform, party wall matters and boundary disputes. He was instructed to report on the diminution in value of Sayes arising out of the grant of the 2017 permission for a property of a height which would be in contravention of the 1967 covenant.

43. Mr Magowan carried out a comparative valuation exercise and in his report of September 2020 placed a value on Sayes of £1,200,000 before considering the impact of the proposed new house on the application land. We note that the application land was a bare site at that date and it was not clear in his report what assumptions Mr Magowan had made in reaching this value about the existence of, or prospective erection of, a single storey house which would not contravene the 1967 covenant. However, in answer to questions from the Tribunal Mr Magowan confirmed that the value of £1,200,000 did take into account the uncertainty over any future single storey house which might be built in compliance with the covenant. That value was agreed by Mr Maunder Taylor.

44. To assist him in his assessment of the impact of the 2017 house, Mr Magowan relied on a technical impact assessment of light issues at the boundary with Sayes, prepared by Peter Huf Architecture. This assessment pointed out an error in material used by Form Architecture in support of the revised design approved in the 2017 permission. The British Research Establishment (“BRE”) guidelines for planning of sunlight and daylight state that obstruction to sunlight may become an issue if a new development subtends an angle greater than 25 degrees to the horizontal, measured to the centre of an existing window. Drawings prepared for the 2017 permission showed that the angle of 25 degrees was not exceeded, but the measurement was made to the top of the study window at Sayes, not the centre. It therefore understated the impact of the 2017 house on the availability of sunlight to the study window. Had the correct point of measurement been used the angle of 25 degrees would have been exceeded.

45. The Peter Huf assessment was not an expert report permitted by the Tribunal, which gave rise to a last minute dispute between the parties as to its admissibility, and whether expert evidence in response could be introduced by the applicants. The applicants had become aware of the Peter Huf assessment on 2 October 2020, but had not made an application to admit their own expert evidence in rebuttal until 7 January 2021. We refused to admit the applicants’ evidence so close to the date of the hearing, which would have left insufficient time for the objectors to respond. However, we did admit, with the exclusion of a paragraph containing opinion evidence, a supplementary witness statement by Mr Uttley. In this he acknowledged that an error had been made in that the 25 degree angle had been incorrectly drawn from a height of two metres above ground level, as would be appropriate had Sayes been a new house, rather than from the centre of the existing study window.

46. It was Mr Magowan’s opinion that the actual market value of Sayes in September 2020 was £1,120,000, a reduction of 6.7% or £80,000 as a result of the 2017 permission. His reasons included the anticipated loss of light to the south west elevation of Sayes, and the close proximity of the proposed house to the boundary. The plans showed a gap of just 0.36 metres from the side of the upper part of the new house to the boundary fence so that the vast majority of the gap between the two houses would be on the Sayes side of the boundary. Not only would the massing so close to the boundary be obtrusive, but the likelihood of needing access through Sayes to carry out maintenance in the future would also have a negative impact on value. Mr Magowan’s opinion of the overall negative impact on value had taken into account the counter-balancing effect of the right of the owner of the application land to carry out tree planting on the boundary which could also have an impact on the light available to Sayes.

47. Mr Magowan had only been asked to consider the impact of the 2017 permission and in cross examination he conceded that if the 2015 permission was implemented, creating a lesser effect on the light available to Sayes because of the lower height of its north eastern elevation, the impact on value would be less. He estimated the reduced loss in value at £70,000. When asked to consider the likely impact on value of the proposed alternative house, Mr Magowan hesitated to commit to an opinion which he had not been asked to consider previously but suggested that a loss of perhaps £50,000 would be expected.

48. In cross examination Mr Magowan agreed that the gross internal area (“GIA”) of the study, at 8.8 sq m, is 4.7% of the total GIA of Sayes at 187 sq m and when pressed he placed a figure of around £100,000 (just over 8% of the total) on the contribution made by the study to the value of Sayes. When asked to explain how, therefore, he arrived at his opinion of loss of value at £80,000, Mr Magowan said that it was based on experience and judgement, taking account of the fact that possibly half of the ground floor rooms would be affected by the proposed development. He took into account more than just the impact of daylight on the study.

49. It was Mr Magowan’s view that the contemporary design of the 2017 house did not have a greater adverse impact on the value of Sayes than would a contemporary mock Georgian design. In forming his opinion he placed less weight on daylight issues, and more on the mass and proximity of the proposed 2017 house which would be a dominating physical structure along the boundary.

Discussion

Does impeding the proposed use secure practical benefits to the first, second and fourth objectors?

50. We have said earlier that Mr Powell, the second objector and freeholder of Barn End at 115 Old Woking Road, benefits only from the 1952 restriction. The freeholders of 117 Old Woking Road (the first objectors) and of 119 Old Woking Road (the fourth objector) benefit from the 1966 covenant. Our site inspection confirmed our understanding from the plan included above that all three properties are so separated from the application land, by other dwellings and mature trees, that impeding the proposed user would not secure to them any practical benefits.

Does impeding the proposed user secure practical benefits to the third objectors at Sayes?

51. We heard much cross-examination of Mr Uttley on the documents provided in the planning applications and whether they did or did not deal adequately with local planning policy and BRE guidelines. However, as we made clear at the time, we have before us two planning permissions which we must take at face value. The third objectors have accepted that both these planning permissions are reasonable uses of the application land, notwithstanding the criticisms of the planning process and documentation submitted in support of the 2017 application. Instead the third objectors relied on those matters in the context of the Tribunal’s discretion to modify the covenants.

52. The applicants have conceded that an error was made in the drawing showing that an angle of 25 degrees to the study window of Sayes was not exceeded. Mr Uttley told us that the measurements had been made at the request of the case officer following a site visit. Had the angle been correctly drawn from the centre of the window, therefore exceeding 25 degrees, then the requirement for further light evidence to be provided would have been a matter for the judgement of the case officer. The height of the end wall in the 2017 permission is therefore a contentious planning issue and it would be likely to have some (possibly limited) greater impact on daylight and sunlight available to the study than would be recommended by BRE guidelines.

53. During our site visit we saw the height of the proposed 2017 end wall represented by a timber frame. We measured the length of the frame at 7.86 metres, whilst the plans show a length of 8.16 metres, so we agree with the third objectors that the frame did not represent the full extent of the 2017 house. We were told that the frame was positioned, by reference to the site datum, to represent the part of the 2017 house which would be closest to the Sayes boundary, i.e. the end wall of the cantilevered first floor. We measured the gap from the frame to the fence at 0.76 metres, so agree with the third objectors that this distance does not represent that shown on the plan at 0.36 metres. If the position on site is accurate the difference would be in their favour, but the application for modification is made on the basis of the approved plans and we must therefore assume that the shorter distance is the correct one. This would also apply to the 2015 house, the height of which was represented on site by horizontal black and yellow tape fixed (we were told) 0.7 metres below the top of the frame.

54. Building footprints were laid out on the application land purporting to show the extent of the 2017 house and also that of the proposed alternative house with its very much longer wall of over 18 metres alongside the boundary with Sayes. We noted on site that the wall of the alternative house would require removal of at least two trees from a group at the boundary with Sayes, which provide useful screening opposite the conservatory. This group, labelled G3 in the arboricultural method statement approved by the 2015 permission, was placed in category C2 for trees of low quality with a life expectancy of at least 10 years, so the main objection to their removal would be the loss of screening for Sayes. Although the alternative house is stated to be single storey, the plans show the wall alongside Sayes to be the same height as that of the 2017 house, at around 4.1 metres, which is surprising.

55. The third objectors were concerned to compare the footprint of the proposed 2017 house with that of the previous bungalow, whilst the applicants were concerned to compare it with the footprint of the proposed alternative house. The bungalow has been demolished and the alternative house does not have planning permission, so neither of those footprints is determinative in our decision making. The previous bungalow was dated and therefore not a good benchmark for a contemporary replacement single storey dwelling within the restrictions of the 1967 covenant. However, the proposed alternative house seems to us to have been designed to illustrate the worst possible alternative scenario of a very long wall, more than double the length of and equal in height to the 2017 house, which would require removal of some screening trees. These would be contentious issues during the planning process for a house that, in any event, may well not conform with the restriction of the 1967 covenant to a single storey house.

56. Mr Maunder Taylor concluded that the 2017 house would have no adverse impact on Sayes by comparison with the alternative house. We agree with that conclusion, because we think that the impact of the alternative house might be equal to or more than that of the 2017 house, but as an extreme and unlikely outcome we give it little weight in judging the benefit secured by the restrictions in impeding the construction of the 2017 house.

57. Mr Magowan considered that the 2017 house would have an adverse impact on value of £80,000 as a result of its mass and proximity, rather than a particular impact on daylight. Mr Magowan gave an opinion in cross examination that the alternative house could still have a devaluing effect, in the region of £50,000, for the same reasons, although we bear in mind that this was not a considered view.

58. During our site visit we formed a similar view to Mr Magowan regarding the impact of mass and proximity. Standing in the side garden of Sayes, the proposed side wall of the 2017 house felt overbearing in height. Moving into the garden at the back of the house the visibility and impact was reduced, but only because of the benefit of screening trees. Inside Sayes there is no doubt that the wall of the 2017 house would dominate the study window, blocking out the current view of trees and some sky. Its impact on the kitchen window would be less severe and on the conservatory quite small, but only because of the screening trees on the boundary.

59. The impact of the 2015 house would be a little less overbearing, because of its lower height adjacent to the boundary, but its height at the far end would still be 8.9 metres and the view from the study in Sayes would be of a roof sloping steeply up to that end. Again, the view from other windows and from the garden would depend heavily on the retention of screening trees

60. The most significant impact would be made by the proposed alternative house, but the argument that it is the natural alternative if the application for modification fails is not supported by a planning permission and lacks credibility. The house would appear to have the maximum adverse effect on Sayes while remaining compliant with the covenanted restrictions (although it is debatable whether compliance has been achieved). A more sensitively designed and sited single storey house would inevitably have much less impact on the third objectors and their enjoyment of Sayes and would be more likely to obtain planning consent. We therefore doubt that there is much realistic prospect of the proposed alternative being constructed and we do not regard it as a relevant comparator when quantifying the benefits secured by the restrictions.

61. The retention of screening trees on the boundary with Sayes is not secured by the restrictions and is not guaranteed. Retention could be secured only if the trees are sufficiently important to be covered by an area tree preservation order or by the landscaping conditions of a planning permission. Whilst condition 6 of both the 2015 and 2017 permissions requires compliance with the arboricultural method statement prior to commencement of development and, in the 2017 permission, during development, we see no mechanism for securing the retention of screening trees once the development is completed. At some point the group could be removed, potentially for good reason, exposing the third objectors to a view of the full mass and height of either the 2015 or 2017 house. These are matters over which the third objectors have no control, which is why the issue of height has such importance to them.

62. We conclude that impeding the proposed use of the application land for either the 2015 house or the 2017 house does secure practical benefits to the third objectors, by limiting the height of any neighbouring house, and thus protecting them from an overbearing new structure which would, to a greater or lesser extent, affect sunlight and daylight to the study and the outlook from windows and the garden on that boundary elevation. Whilst the restriction cannot protect the third objectors from the proximity of a new structure, for both the 2015 and 2017 houses it is their proximity to the boundary that exacerbates the impact of their height and mass.

Are the practical benefits secured of substantial value or advantage?

63. The base value of £1,200,000 agreed by the two experts is stated to be “assuming that planning permission has not been granted for the new build house at Southernhay”. We are confident that it reflects the prospect that a new single storey house would still be built on the application land. Mr Magowan was not able to give us any detailed analysis of the four comparable sales upon which he based his opinion of value, nor any detailed analysis of the way he arrived at his figure. However, he told us he had considerable experience of the local residential property market, having valued about 10 residential properties in the locality over the last two years, and before that had carried out up to 20 mortgage valuations per week across Surrey, so we accept that he is able to exercise judgement on market value from his professional experience.

64. It was Mr Magowan’s considered opinion that the loss of value which followed from the 2017 permission was £80,000 (6.7% of £1,200,000). His opinion, given in cross-examination, that the loss following from the 2015 permission might be £70,000 (5.8% of £1,200,000) was a recognition that the impact on value of a lower end wall might be a little less. We accept Mr Magowan’s figures as reasonable and realistic.

65. Ms Holland referred to the Tribunal’s decision in Re Foggs’ Application [2018] UKUT 114 (LC) where a restriction which inhibited development which would result in a diminution in value of 5% was held to secure a practical benefit of substantial value. But whether a practical benefit is substantial is not simply a matter of arithmetic, and will depend on the circumstances. There are some similarities between this case and Fogg, but we do not consider 5% to be a rule of thumb, or threshold, by which we should be bound in this or any future case. Nonetheless, we consider that a loss of value of between £70,000 and £80,000 is substantial.

66. On that measure, and in the light of our inspection, we consider that by impeding the construction of either of the houses the restrictions secure practical benefits of substantial value. Whether impeding them secures practical benefits of substantial advantage is a separate consideration and we are satisfied that by preventing the implementation of both permissions the restrictions secure benefits of substantial advantage to the third objectors in their enjoyment of sunlight and daylight to the study, the outlook from the study, kitchen, conservatory and garden, and the avoidance of an overbearing vertical wall in close proximity to the boundary.

Disposal

67. We are not satisfied that ground (aa) has been established and we therefore refuse the application to modify the 1967 covenant. Since the 1967 covenant continues to impede the proposed use we do not need to consider modification of the 1952 and 1966 covenants.

68. This decision is final on all matters except the costs of the application. The parties may now make submissions on such costs and a letter giving directions for the exchange and service of submissions accompanies this decision. The attention of the parties is drawn to paragraph 24 of the Tribunal’s Practice Directions of 19 October 2020.

|

|

|

|

|

A J Trott FRICS |

|

Mrs D N Martin MRICS FAAV |

|

|

Dated: |

22 April 2021 |