Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Haandrikman v Heslam (LAND REGISTRATION - ADVERSE POSSESSION) [2021] UKUT 56 (LC) (19 March 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2021/56.html

Cite as: [2021] UKUT 56 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2021] UKUT 56 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LREG/49/2020

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

LAND REGISTRATION - ADVERSE POSSESSION - successive periods of adverse possession - transmission of title - section 75 of the Land Registration Act 1925 - significance of fencing and of grazing

AN APPEAL AGAINST A DECISION OF THE FIRST TIER TRIBUNAL (PROPERTY CHAMBER)

|

BETWEEN: |

MRS TANYA HAANDRIKMAN |

|

|

|

|

Appellant |

|

|

and |

|

|

|

EDWYN HeSLAM |

Respondent |

|

|

|

|

Re: Land on east side of Fortuna Villa,

Bridgefoot,

Workington, CA14 1YF

Judge Elizabeth Cooke

4 March 2021

by remote video platform

Mr Richard Oughton for the appellant, instructed by Hill Dickinson LLP

Mr James Fryer-Spedding for the respondent, instructed by Arnison Heelis

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2021

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Asher v Whitlock (1865-66) LR 1 QB 1

Batt v Adams (2001) 82 P& CR 32

Chambers v Havering [2011] EWCA Civ 1576

Collingwood King v Newcastle Diocese [2019] UKUT 176 (LC)

Inglewood Investments Company Limited [2002] EWCA Civ 1733

Site Developments (Ferndown) Limited and others v Cuthbury Limited and others [2010] EWHC 10 (Ch)

Introduction

1. This is an appeal about adverse possession. The appellant, Mrs Haandrikman, appeals the decision of the First-tier Tribunal (“the FTT”) that the respondent, Mr Heslam, be registered as proprietor of a strip of land, 75m by 12m, adjoining his garden. The strip is part of a railway, dismantled long ago following the Beeching reforms; the appellant was, until the FTT’s decision, the registered proprietor, as was her father before her.

2. The appeal raises two technical issues which, I have found, were argued before the FTT but were not considered in the FTT’s written reasons for its decision. Despite that, the appeal fails; although there was no explicit discussion of those two issues I find that the judge was entitled to reach the conclusion to which he came.

3. I heard the appeal by remote video platform on 4 March 2021; the appellant was represented by Mr Richard Oughton and the respondent by Mr James Fryer-Spedding, both of counsel; I am grateful to them both.

4. In the paragraphs that follow I set out the factual and legal background to the appeal and then look at the grounds of appeal in turn.

The factual background

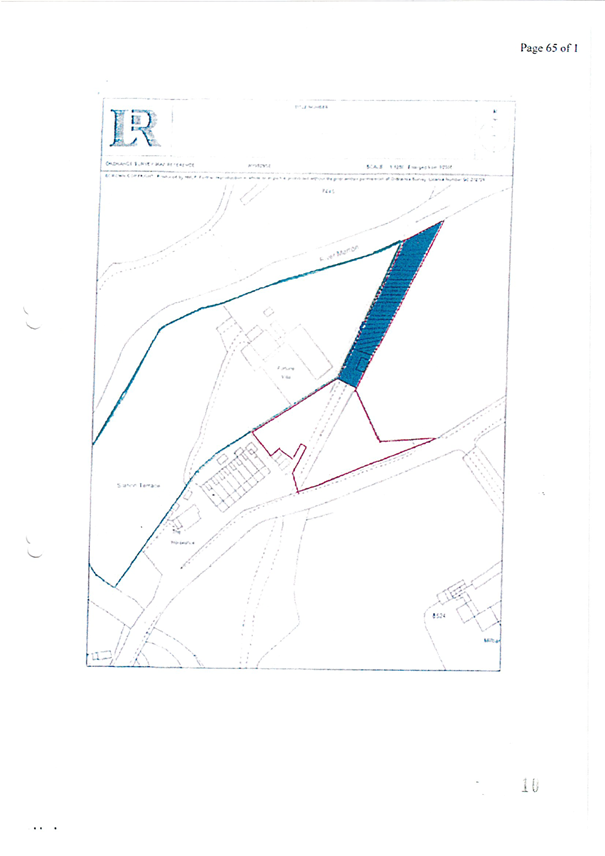

5. I take the following account from the facts found by the FTT, from which there is no appeal. On the following page is a plan; the respondent’s home, Fortuna Villa and its surrounding land, is the larger area edged in bold in the upper and left area of the plan, the disputed strip is shaded, and the respondent’s registered title as it stood before the FTT’s order comprised the disputed strip together with the smaller area edged in bold to the south of the strip. I use the label “Fortuna Villa” to mean both the house and its land.

6. Fortuna Villa was purchased by Mr and Mrs Atkinson in 1959.

7. The FTT found as a fact that by 1978 Mr and Mrs Atkinson had put up a fence along the southern boundary of the strip, closing it off from the appellant’s land. There had been for years before then a fence along the boundary next to the field to the east, and the FTT found that a section in that fence could be opened to allow passage from the field, over the strip and into Fortuna Villa. The FTT found that from 1978 Mr and Mrs Atkinson were in adverse possession of the strip, because of the southern fence which shut out the appellant and others and because Mr and Mrs Atkinson’s son Michael grazed sheep on the strip. He rented the field to the east and used to take his sheep over the strip on to Fortuna Villa. The trees and vegetation to the west of the strip had gaps so that the sheep could get through to the strip while they were grazing at Fortuna Villa.

8. As I said above, the strip is part of a disused railway. In 1987 it was purchased from British Railways Board by Thomas Bailey, the appellant’s father, and he was registered early in 1990 as proprietor with possessory title. Title was possessory because the Railway Board, aware of possible encroachment on the strip, sold him “such right title or interest as they may have” in it; it was upgraded to title absolute in 2005.

9. At some point in 1991 or 1992 Michael Atkinson moved to France. His father Mr Atknison died in 1990 and in 1994 Mrs Atkinson sold Fortuna Villa to Mr Hicks and Miss Ives, and that transfer gave rise to first registration.

10. Mrs Atkinson made a statutory declaration at the time of that sale, relating in part to a right of way over a different area but also intended to establish title to the disputed strip. Because she referred only to Michael driving his sheep over the strip, and did not say that anything was done on the strip itself, HM Land Registry did not accept the statutory declaration as evidence that adverse possession had been taken of the strip. At the hearing before the FTT, however, other witnesses were able to fill in more of the facts and hence the judge’s findings.

11. The FTT found that from 1994 to 2001 Mr Goulding grazed sheep on the strip as licensee of Mr Hicks: at paragraph 31 the judge recorded “There was grazing of sheep from 1994 until 2000 or early 2001, and mowing and maintaining the land where required. Mr Hicks deposited building materials on the land.”

12. In 2001 Fortuna Villa was sold to Mr and Mrs Hoyle.

13. Mr Heslam bought Fortuna Villa in 2012. In 2017 he applied to be registered as proprietor of the strip. The appellant objected and the matter was referred by the registrar to the FTT. Hence the appealed decision.

The legal background

14. There is no dispute between the parties as to the legal basis for the acquisition of title by adverse possession, dependent as it is upon both factual possession and the intention to possess. Nor is there any dispute about the theoretical basis of a squatter’s title, established long ago by Asher v Whitlock (1865-66) LR 1 QB 1, which is that by adverse possession the squatter obtains a legal estate in fee simple, which exists alongside that of the paper owner whose title is unregistered. The squatter’s title is weaker than the paper title but stronger than anyone else’s, until the day 12 years later when sections 15 and 17 of the Limitation Act 1980 bars the paper title with the result that the squatter has the strongest title and can regard himself as the owner of the land.

15. Now we travel back into the world of title registration, but in the past, because the legal background to the present appeal is the law as it stood before 13 October 2003 when the Land Registration Act 2002 came into force. The relevant statute is the Land Registration Act 1925. If the dispossessed owner’s title was registered then, of course, section 17 of the Limitation Act 1980 has no effect on the register. Instead, section 75 of the 1925 Act provides that once the squatter has achieved 12 years of adverse possession then the registered proprietor holds the title on trust for the squatter.

16. It appears that the FTT took the view that Mr and Mrs Atkinson completed their 12 years in 1990 after Mr Bailey’s title was registered; it follows that from that point onwards Mr Bailey held his registered title upon trust for them. Had the Atkinsons completed their 12 years prior to that registration the analysis would be different, but there is no need to explore that.

17. The coming into force of the 2002 Act had no effect upon trusts created by section 75 of the 1925 Act, and the transitional provisions in paragraph 18 of Schedule 12 to the 2002 Act have the effect that the beneficiary of that trust can apply to be registered as proprietor, and does not have to meet the more stringent requirements for registration by virtue of adverse possession found in Schedule 6 of the 2002 Act.

18. That is Mr Heslam’s position. He says that title to the strip was acquired by adverse possession by his predecessors in title long before 2003, that Tom Bailey and later his daughter, the appellant, held the registered title upon trust, and that he is entitled to registration as the beneficiary of that trust.

19. The FTT agreed. The judge said at paragraph 32:

“I am satisfied that the Applicant’s predecessor’s in title had obtained the benefit of the trust under section 75 of the Land Registration Act 1925 in or about 1990. From that time onwards, the registered proprietor - initially Tom Bailey but latterly the Respondent - held the title on trust for the squatter. I shall therefore direct the Chief Land Registrar to give effect to the Applicant’s application…”

The first ground of appeal: transmission of the benefit of the trust in 1994

20. The first ground of appeal is that the title acquired by Mr and Mrs Atkinson by adverse possession was not passed to Mr Hicks and Miss Ives in 1994.

21. In order to understand that ground of appeal we have to go back into the mechanics of adverse possession; those mechanics are unpleasantly complicated because by the end of 1990 the Atkinsons held two interests: their legal fee simple acquired by adverse possession on common law principles (which co-existed with the registered legal title of Mr Bailey) and their equitable interest under the section 75 trust.

22. A legal estate in land can only be transferred by deed (section 52 of the Law of Property Act 1925) and an equitable interest can only be assigned in writing (section 53(1)(a) and 53(1)(c) of the Law of Property Act 1925. Nevertheless successive squatters can take over from each other without the need for a deed or for writing. In Site Developments (Ferndown) Limited and others v Cuthbury Limited and others [2010] EWHC 10 at paragraph 173 Vos J, as he then was, explained that the starting point is the ability of successive squatters to aggregate their possession:

“173 … As Megarry & Wade on the Law of Real Property 7th edition 2008 describes the position at paragraph 35-022: “ If a squatter is himself dispossessed the second squatter can add the former period of occupation to his own as against the true owner. This is because time runs against the true owner from the time when adverse possession begins, and so long as adverse possession continues unbroken, it makes no difference who continues it.”

23. In Site Developments one squatter had completed 12 years’ possession before another, KIL, took over. Vos J continued :

“175 [Counsel for the registered proprietor] has argued, ingeniously, that, once the 12 year period expires as it did here (notionally anyway before the first known transfer on 5 June 1975), the squatter's … right became an accrued rather than an inchoate right, which can only be transferred formally by writing in compliance with section 53 of the Law of Property Act 1925 as a beneficial interest in land under the trust arising under section 75 of the Land Registration Act 1925 . In my judgment, this response does not work for the Defendants, because a squatter can rely on any period of 12 years arising whenever it asserts its claim. Mr Wilson might be right if the squatter wanted to assert its 12 years at some stage in the past, but CREL asserts its rights through KIL, which acquired the Brown Land on 4 April 1986. If, as a matter of fact, KIL's transferor relinquished possession to KIL at that time, KIL has since passed the rights it acquired formally to CREL. In short, KIL could rely on the 11 years and 364 days possession immediately preceding the transfer to it, and then later assign its 12 years possessory rights whether from one day after the transfer to it, or from later on, to CREL. “

176. The question then resolves itself into one of fact…. In my judgment, as a matter of fact, each successor company relinquished possession of the Blue Land to its successor, when it transferred the Brown Land. There is no evidence that any of the transferors sought to retain any interest in Blue Land thereafter.”

24. Accordingly, successive squatters in unregistered land, under the 1925 Act regime, can pass title to each other after 12 years have elapsed just as can successive squatters before 12 years elapse, without the need for formal transfer of their legal estate or of the beneficial interest under the section 75 trust.

25. The first ground of appeal is that the FTT did not explain how title passed from the Mrs Atkinson to Mr Hicks and Miss Ives in 1994, and that in fact it could not have done so because there was no grazing on the land after Michael Atkinson left, and the presence of the southern fence was by itself insufficient to amount to adverse possession. Unless Mrs Atkinson remained in adverse possession of the strip until Mr Hicks and Miss Ives took it over, the beneficial interest under the trust was not transferred to them.

26. Mr Oughton acknowledges that the judge found that Mrs Atkinson was in adverse possession until 1994 but argues that once grazing had stopped there was insufficient material for him to make that finding. Fencing, he says, does not amount by itself to adverse possession; therefore Mrs Atkinson was not in adverse possession once the grazing stopped and so did not transmit to her purchasers her beneficial interest under the section 75 trust (which remains in her estate). If that were correct then the respondent’s claim must fail because Mr Hicks and Miss Ives were not in possession for 12 years before the 2002 Act came into force and so the respondent would be unable to take advantage of the 1925 Act’s provisions and the transitional provisions (paragraphs 14 and 16 above).

27. Mr Oughton’s argument about fencing rests on the maxim that “a fence to keep people out is good evidence of adverse possession, but a fence to keep animals in or out is not good evidence” (Jourdan and Radley-Gardner, Adverse Possession, 2nd edition 13-16); he points out that Mrs Atkinson in her 1994 statutory declaration said that the southern fence was put up “to prevent dogs, which were kept by a neighbour on part of the railway line to the south of our land, straying on to our land.” Mr Oughton says that the reference to “our land” was a reference to Fortuna Villa, not to the disputed strip.

28. He acknowledges that in Hounslow v Minchinton (1997) 74 P & CR 221Millett LJ cast doubt upon the status of fencing for animals:

“Mr Lewison relied upon the fact that [the Defendant’s] enclosure of the land was in order to keep the dogs in rather than other persons out. But their motive is irrelevant. The important thing is that they were intending to allow their dogs to make full use of what they plainly regarded as their land, and which they used as their land.”

29. However, Mr Oughton cites two further decisions of the Court of Appeal which did not follow Millett LJ and held that a fence to keep animals in or out was not good evidence of adverse possession: Inglewood Investments Company Limited [2002] EWCA Civ 1733 and Batt v Adams (2001) 82 P & CR 32. But in Chambers v Havering [2011] EWCA Civ 1576 Etherton LJ discussed the point and preferred the view of Millett LJ.

30. Mr Oughton submits that in no reported decision has fencing alone been found to amount to adverse possession; there is always some other activity going on, and there was none here. He also cites Collingwood King v Newcastle Diocese [2019] UKUT 176 (LC), a case on unusual facts where the land said to have been adversely possessed was a vault beneath the floor of a church, where the Tribunal (HHJ Hodge) said:

“Factual possession requires some dealing with the land as an occupying owner, yet there is no evidence that anyone representing the Respondents has ever even entered the vault.”

31. In response Mr Fryer-Spedding starts from the FTT’s unequivocal finding, at its paragraph 31, that:

“The owners and occupiers of Fortuna Villa have been in exclusive factual possession of the Disputed land for nearly 40 years before the events of October 2017.”

32. That finding of course includes the period from 1991 to 1994. The judge appreciated that use of the land was not and could not be intense; this was land of limited usefulness, being formerly a railway line and therefore without good quality soil at the surface. Mr Fryer-Spedding points out that the southern fence was substantial, and referred me to the photographs in the bundle which show that it was a post and wire fence with pig netting and with barbed wire along the top. Judge Rhys found that it kept people out and that it was therefore far more than just a fence to deter dogs.

33. Mr Fryer-Spedding argues that there is no conflict between the Court of Appeal authorities on the significance of fencing, and refers to paragraph 40 of Chambers v Havering LBC where Etherton LJ said this:

“Each case turns on its own particular facts. In a case of adverse possession, where the defendant relies upon the existence of fencing, the Judge will plainly have to consider its significance. In some cases, it will be cogent evidence, perhaps the most cogent evidence, of adverse possession where its effect is wholly to exclude the paper owner, even if it was erected to keep animals inside rather than to exclude people, including the paper owner. In other cases, when considered in the context of the evidence as a whole, fencing may be not be inconsistent with the absence of actual possession and of an intention to possess on the defendant's part, even where the fencing physically excludes the paper owner. … If … the Judge … was saying that Mr Chambers' repair and replacement of fencing was, as a matter of law, incapable of constituting evidence in support of Mr Chambers' assertion of adverse possession, merely because he repaired and replaced the fencing to keep his animals from escaping from the disputed land as opposed to excluding the Council, then that was incorrect. I do not myself think he was saying the latter.”

34. I agree that there is no need to choose between the authorities on this point. Every case turns on its facts; what is manifestly not correct is to argue that fencing a piece of land to keep animals out can never as a matter of law amount either to factual adverse possession or to evidence of an intention to possess.

35. In this case the strength of the fencing was significant, as was its effect on the rest of the world; it completely blocked access to the disputed land for the registered proprietor and indeed for anyone seeking to enter from the south. I do not accept that Mrs Atkinson, in her 1994 statutory declaration, meant to say that the idea was just to keep the dogs off Fortuna Villa rather than off the disputed land; although her statutory declaration did not persuade HM Land Registry at the time, the point of her making that declaration was to establish title to the strip and so her references to “our land” included it.

36. Perhaps the appellant’s case is strongest when put like this: imagine circumstances where the Atkinsons bought the land in 1991, put up the southern fence in 1991, and never grazed it. Would that have been sufficient to amount to adverse possession against the registered proprietor? In light of the nature of the fence and its effect it may have been, but that is irrelevant because it is not what happened. Adverse possession was taken by virtue of both fencing and grazing in 1978, and nothing happened after Michael stopped using the land for his sheep to change that position. As Etherton LJ put it in Chambers v Havering at paragraph 57:

“… in my judgment continuous use is not the test. It is the taking of possession that is critical. If possession passed to Mr Chambers at any point then he would not have needed continuous use to have maintained possession: Bligh v Martin [1968] 1 WLR 804 , 811; Generay Ltd v The Containerised Storage Company Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 478 § 49.”

37. I find that the judge was entitled, on the evidence before him, to reach the conclusion that Mrs Atkinson remained in adverse possession following her husband’s death and after grazing had ceased. Adverse possession was taken by the Atkinsons as a result of enclosure - keeping the world out, not just the neighbour’s dogs - and of grazing which, taken together, amounted to almost all that could be done with this small and poor quality patch of disused railway. As the judge said at his paragraph 32:

“Given the nature of the land, and its enclosure, the fact that the user is sporadic and relatively light does not in any way detract from the finding of exclusive factual possession.”

38. Grazing was indeed sporadic, but the fact that the land was transferred during a period when grazing was not happening does not mean that adverse possession had ceased. Mrs Atkinson remained in exclusive factual possession and, as Vos J put it (paragraph 23 above) relinquished possession to Mr Hicks and Miss Ives.

39. The FTT in its decision did not spell out the mechanics of transmission. The judge had to assess factual evidence, given by 19 witnesses over three days; there was major conflict not only between the appellant’s and the respondent’s witnesses but also between the two statements of one witness who gave evidence for both parties. Understandably the judge devoted most of his judgement to resolving the factual evidence. The findings of fact that he made led him to the conclusion that title was passed from Mrs Atkinson to Mr Hicks and Miss Ives; he did not explain how that happened or address Mr Oughton’s argument about that, but the conclusion he reached did indeed follow from the findings of fact that he made and his conclusion was undoubtedly correct. This ground of appeal fails.

The second ground of appeal: grazing sheep is not adverse possession

40. I can deal with the second ground of appeal much more briefly because it turns out to have little or no substance.

41. Mr Oughton had two arguments. The first was that the FTT should not have found that sheep had been grazed on the strip during Mr and Mrs Atkinson’s ownership because Mrs Atkinson in her 1994 statutory declaration did not refer to grazing on the strip, and hers was the only contemporary evidence. There is no permission to appeal findings of fact. Mr Oughton’s argument appears to be that the judge made an error of law because the evidence was insufficient to support his finding. However, a number of other witnesses also mentioned grazing on the strip and there is no possible basis for the Tribunal to interfere with the factual finding on this point.

42. The issue on which permission was granted was that there is authority to the effect that grazing does not amount to adverse possession. Mr Oughton in seeking permission to appeal argued that those authorities were referred to before the FTT and were not mentioned by the judge in his decision.

43. The difficulty that Mr Oughton has here is that he cannot point to a time where the FTT found that the only act of adverse possession being carried out was grazing. He did not try to argue that that was the case after 1994, because there was a finding of fact that Mr Hicks and Miss Ives also mowed and maintained the strip (see paragraph 11 above). His argument is ineffective so far as the period of Mr and Mrs Atkinson’s ownership is concerned because of the existence and significance of the fence. At no time during the relevant period was there nothing but grazing going on by way of adverse possession.

44. Accordingly I accept that Mr Oughton raised before the FTT his argument that grazing alone could not constitute adverse possession, and the judge did not refer to the relevant authorities in his decision; but he did not need to because the point did not arise on the basis of the other findings of fact that he had made.

45. Accordingly the second ground of appeal cannot succeed.

Conclusion

46. The appeal is dismissed; the decision of the FTT stands, along with its direction to the registrar to register the respondent as proprietor of the disputed strip.

Judge Elizabeth Cooke

19 March 2021