Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> London Borough of Lewisham v Pearmain (COMPENSATION - Compulsory Purchase) [2021] UKUT 154 (LC) (25 June 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2021/154.html

Cite as: [2021] UKUT 154 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2021] UKUT 154 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LC-2020-105

(Formerly ACQ-126-2020)

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

COMPENSATION - Compulsory Purchase - pre-fabricated bungalow acquired by General Vesting Declaration - market value - comparable evidence of bungalows, flats and terraced housing - limitations on secured borrowing restricting potential purchasers - compensation for disturbance on temporary and permanent relocation

IN THE MATTER OF A NOTICE OF REFERENCE

BETWEEN:

|

LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM Acquiring Authority

-and-

LORRAINE PEARMAIN Claimant |

|

|

|

|

Re: 14 Meliot Road,

London,

SE6 1RY

Determination by written representations

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2021

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Director of Buildings and Lands v Shun Fung Ironworks Ltd [1995] 2 AC 11

Introduction

1. This is a reference to determine the amount of compensation payable to Ms Lorraine Pearmain (“the claimant”) following the compulsory purchase by the London Borough of Lewisham (“the acquiring authority”) of her freehold interest in 14 Meliot Road, London SE6 1RY (“the property”).

2. The property was acquired pursuant to the London Borough of Lewisham (Excalibur Estate, Lewisham - Phase 3) Compulsory Purchase Order 2015, which was confirmed on 7 December 2015. The acquiring authority made a General Vesting Declaration on 20 December 2017 and the vesting date of 30 March 2018 is the valuation date for compensation.

3. The matter was referred to the Tribunal by solicitors for the acquiring authority on 8 September 2020.

4. Expert written evidence for the claimant was provided by Mr Tom Olden MRICS of Olden Property Consulting Limited. Expert written evidence for the acquiring authority was provided by Mr David Conboy MRICS of Newsteer Real Estate Advisers.

Background

5. The Excalibur Estate (“the estate”) lies approximately 1.7 miles south east of Catford town centre in the borough of Lewisham. It covers an area of 15.25 acres (6.17 hectares) which was originally amenity space for the surrounding Downham Estate of local authority houses and flats built between the wars. Between 1945 and 1946, 186 prefabricated bungalows were built to provide temporary accommodation for families displaced by bomb damage in World War II. The estate became an established community and the bungalows remained in good habitable condition through to the 21st century when the acquiring authority approved a plan for redevelopment.

6. Redevelopment of the estate, in partnership with London & Quadrant Housing over five phases, involves demolition of all bar six of the original bungalows (those six having been listed Grade II in March 2009) to provide 371 new residential units. The property was located centrally within the estate and was demolished as part of Phase 3 of the redevelopment.

7. The property was a detached bungalow of 764 sq ft (62.59 sq m) gross internal area (“GIA”) providing a central hallway, dual aspect reception room, kitchen with door to rear garden, two double bedrooms, bathroom and incorporated WC. It was a ‘Uni-Seco’ construction of resin bonded plywood timber frame, clad in asbestos cement sheeting with a wood wool core. The claimant had undertaken significant improvement works to the property in recent years, including a new roof, dry lining and insulation of the walls, new double glazed uPVC windows and a new rear door. Gas central heating had been installed, with recent new radiators. New flooring had been laid throughout, and a new kitchen and worktops installed. It is agreed that the interior of the property was in good condition and decorative order at the valuation date.

8. The plot area of 2,740 sq ft (254.63 sq m) included a small fenced and paved front garden and a private rear garden with an outbuilding and two wooden sheds. The plot was accessible on foot from a pathway between two rows of bungalows and had on-street parking available nearby within the estate.

9. It is agreed that, in the absence of the scheme underlying the acquisition, a lapsed planning permission for demolition and replacement with a three bedroom brick bungalow would have been available.

10. I visited the estate on 27 May 2021, by which date the property had been demolished and the Phase 3 site was surrounded by hoardings. However, I was able to walk through streets not yet acquired and view the remaining bungalows. I also walked past the five comparable bungalows relied on by the claimant’s expert and five of the properties referred to in expert evidence for the acquiring authority.

Statutory provisions for assessment of compensation

11. Section 5 of the Land Compensation Act 1961 (“the 1961 Act”) sets out the rules for assessing compensation, of which the relevant rules at the valuation date were:

“(1) No allowance shall be made on account of the acquisition being compulsory:

(2) The value of land shall, subject as hereinafter provided, be taken to be the amount which the land if sold in the open market by a willing seller might be expected to realise:

…

(6) The provisions of rule (2) shall not affect the assessment of compensation for disturbance or any other matter not directly based on the value of land.”

Summary of the dispute

12. It is agreed that the claimant is entitled to compensation for the market value of her property at the valuation date, in the ‘no-scheme’ world assuming that the scheme of acquisition did not exist, but the amount of that compensation is not agreed. When the value for compensation is determined, it is agreed that the claimant is entitled, under the Land Compensation Act 1973, to a ‘home loss payment’ at 10% of that value.

13. It is also agreed that the claimant is entitled to receive compensation for disturbance costs and losses incurred as a consequence of the acquisition and her relocation, initially to temporary accommodation whilst her compensation dispute is resolved and then to a permanent new location, but some items of her claim are challenged.

14. The respective positions are summarised below:

Market value

Evidence for the claimant

15. Mr Olden is an RICS Registered Valuer who set up his own firm in 2014. He has worked in both the public and private sectors advising on compulsory purchase schemes and valuations in and around London. In his report Mr Olden identified no evidence of similar property sales which were unblighted by redevelopment proposals. It is his opinion that the scarcity of detached properties, and particularly bungalows, within the borough of Lewisham gives the property a particular value unrelated to sales of flats or terraced houses of similar size. A detached property provides a private garden, the ability to extend the property, outside storage space, a private entrance and fewer neighbours in close proximity.

16. Mr Olden made enquiries of a mortgage specialist and does not consider that there would have been undue difficulty in obtaining secured lending against the property as a result of its construction, albeit it would be from a specialist lender who would put in place a mortgage retention fund for completion of recommended works. Mr Olden provides a list of works carried out to the property by the claimant’s husband, which addresses substantially the list of works recommended in a report to Lewisham Borough Council in June 2005 on the Uni-Seco properties on the estate.

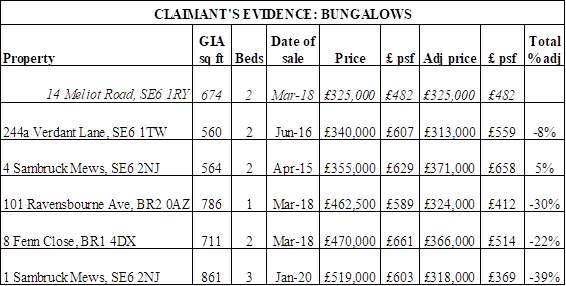

17. The scarcity of bungalows, and therefore sales, in the locality is apparent in the evidence of only five sales relied on by Mr Olden, from locations up to two miles away and with sale dates between April 2015 and January 2020. Their details are summarised in the table below, in ascending order of price before adjustment, showing Mr Olden’s valuation of the property in context.

18. Mr Olden has adjusted his evidence from the date of sale to the valuation date of March 2018 using the UK House Price Index for sales of detached houses in Lewisham, but the only significant index adjustment (above 3%) is an increase of 19.3% to the sale price of 4 Sambruck Mews in April 2015. 10% was then deducted from all the evidence to account for their locations not being on an estate and a further 10% for the fact that they were all of traditional rather than pre-fabricated construction. Where on-site parking was available £10,000 was deducted, although this seems to have been overlooked for 101 Ravensbourne Avenue which has a garage. Finally, adjustments of between 10% and 15% were made for size difference.

19. The five adjusted prices produce an average of £338,000, and Mr Olden gives his opinion of the value of the property at £325,000.

20. Mr Olden had received evidence from Mr Conboy of the sale of 7 Persant Road on the estate in May 2010 for £110,000. This property was listed in March 2009 and has not been acquired for the redevelopment scheme, so is said by Mr Conboy not to be a blighted sale. However, Mr Olden points out that even in 2010 the need for regeneration of the estate was well known, with a long history of consultations and reports in the context of the acquiring authority’s Decent Homes Strategy, and therefore the property sale price would have been blighted. Mr Olden comments that few details are available of 7 Persant Road, the sale of which is therefore of little assistance in valuing the property some eight years later.

21. In response Mr Olden refers to the sale of 7 Baudwin Road on the estate for £125,000 in in August 2004 which, after indexation, would be equivalent to £287,000 at the valuation date. The property was acquired by the acquiring authority in February 2013 for £240,000 which, after indexation, would be equivalent to £403,200 at the valuation date. However, he draws no further inference from that evidence.

Evidence for the acquiring authority

22. Mr Conboy is an RICS Registered Valuer and head of compulsory purchase at Newsteer. His professional experience includes advising local authorities and developers utilising compulsory purchase powers and also advising claimants who have had their interests acquired. He has valued eight other properties on the estate for the acquiring authority and reached agreement with the owners on their value for compensation.

23. In his report Mr Conboy considers that the non-traditional construction of the property, and the presence of asbestos, would have been a deterrent to many prospective purchasers in the market. He also considers, based on conversations with mortgage brokers, that only a few specialist lenders would be prepared to lend against the property and, even then, if their valuer reported a limited market for resale that might deter them from lending at all. Mr Conboy acknowledges that the property was subject to a mortgage at the date of valuation but considers that new purchasers would have had difficulty securing a loan against it. Any such loan would be at a low loan-to value ratio and a higher rate of interest than for other properties. He estimates that a mortgage retention for required works would be in the order of £40,000 which, in addition to the higher deposit required for a lower loan-to-value ratio, is an unusually large cash commitment for a prospective purchaser at this level of the market.

24. In his overall assessment of the property Mr Conboy considers that the positive aspects of the property, as a detached bungalow in good decorative order, would be outweighed by the negative aspects of non-traditional construction, limited life expectancy, lack of off-street parking and access to the property only by a shared narrow footpath. That negative balance would affect saleability and make it very difficult to obtain a mortgage, leaving only cash investor purchasers in the market.

25. Like Mr Olden, Mr Conboy was unable to identify any recent comparable evidence of a market sale of a Uni-Seco bungalow, but unlike Mr Olden he has relied on a range of evidence of other types of property sales within the locality, comprising 12 two-bedroom terraced houses and five flats of two or three bedrooms.

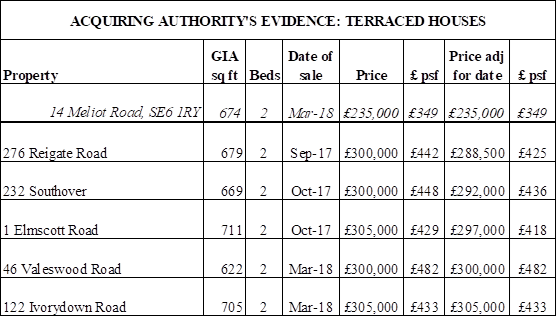

26. The 12 houses were located within or at the end of terraces in large housing estates and were offered in varying states of condition. The dates of sale were between September 2017 and August 2018 and Mr Conboy adjusted the sale prices to the valuation date using the UK House Price Index. Five houses of comparable floor area to the property sold for adjusted prices of between £288,500 and £305,000 (£418 - £482 per sq ft), as summarised in the table below with Mr Conboy’s valuation of the property shown in context.

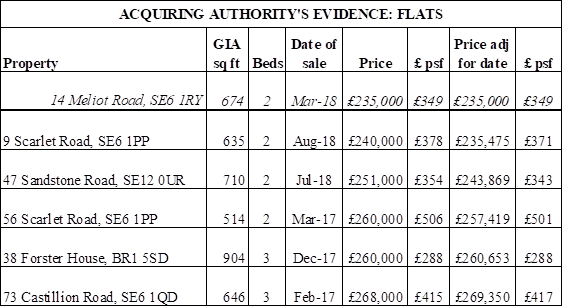

27. Mr Conboy’s evidence of flat sales between February 2017 and August 2018 ranged in price from £240,000 to £268,000 but (it is not clear why) he did not adjust this evidence for date of sale. I have used the index provided in evidence to assess the adjusted figures, which range from £235,475 to £269,350 (£288 - £501 per sq ft) as shown in the table below, with Mr Conboy’s valuation of the property shown in context.

28. Mr Conboy uses this evidence to show that at (or around) the valuation date a two to three bedroom flat of traditional construction in close proximity to the property could have been purchased within a range of £240,000 to £270,000. He considers that a cash investor purchaser would only consider the property as an investment if its price sat below the alternative of a similar sized flat in the same locality and places a value of £235,000 on it. He also shows this figure in the context of typical price ranges for two bedroom flats and two bedroom semi-detached houses (of which no evidence was provided) as reflecting a discount of 6-10% and 28-33% respectively.

29. Turning to the evidence of bungalow sales relied on by Mr Olden, Mr Conboy considers that all except 244a Verdant Lane are unsuitable as comparables because of their higher value locations, and that the 10% adjustment for an off-estate location made by Mr Olden is far too small to reflect that advantage. By contrast, 244a Verdant Lane sits in a rear garden development behind higher value houses, but adjacent to the Downham housing estate so its location is somewhat comparable. It sold for £340,000 in June 2016 and no adjustment is required for the date of sale as the index in March 2018 had returned to the same level as in June 2016.

30. Mr Conboy adjusts upwards from the sale price of £340,000 by £20,000 for the lack of road frontage to establish a benchmark figure for a brick built bungalow. He adjusts upwards again by £20,000 for its smaller size than the property. He then adjusts downwards by 10% for the estate setting of the property and 30% for the non-traditional construction, plus a further £10,000 for lack of parking, to reach an adjusted value of £234,000 (£ 418/sq ft) which supports his valuation of the property at £235,000.

31. Mr Olden comments in response that an adjustment of £20,000 is insufficient to take account of the size difference between 244a at 560 sq ft and the property at 674 sq ft.

32. As stated earlier, Mr Conboy refers to the sale of 7 Persant Road on the estate for £110,000 in May 2010 as a sale of a similar property which he describes as unblighted because the scheme of redevelopment for the estate was still subject to a ballot of residents to be held in July 2010. Mr Conboy does not index the sale price but compares it with the range of prices achieved at that date for semi-detached houses and terraced houses in the locality, to show a discount of 34-38% and 28-32% respectively. He carries out a similar exercise for the sale of 7 Baudwin Road in August 2004, to show a discount of 24-28% on semi-detached houses and 20-24% on terraced houses.

33. Mr Conboy’s evidence goes on to consider prices agreed in compensation for other properties on the estate, whilst acknowledging those have little weight as evidence. He also carries out a residual valuation of the site as a development opportunity based on the lapsed planning consent for demolition and replacement with a three bedroom brick bungalow, which reveals a value far below that of £235,000 proposed for compensation.

Discussion

34. The essential difference between the approach of the two experts lies in their assessment of the market for the property in the no-scheme world at the valuation date. Mr Olden makes no concession for the difficulty a purchaser would have in obtaining a mortgage and values the property as a detached bungalow by reference to sales of similar sized bungalows, which are scarce. His evidence of five sales is spread across dates from April 2015 to January 2020 and the adjustments, for date of sale, location and construction in particular, rely heavily on a subjective assessment of those factors.

35. Sambruck Mews is a small development of four bungalows set back behind a gated access drive from Inchbery Road within the Culverley Green Conservation Area. The semi-detached Edwardian villas on Inchbery Road have interesting architectural details and are typical of the conservation area. My inspection revealed that the close of four bungalows benefits from the premium environment, without detracting from it, and is barely comparable in any respect with the setting of the estate. It is also located much closer to amenities of Catford town centre.

36. The evidence of 1 Sambruck Mews, sold in January 2020, can be given little weight in assessing a market value 22 months earlier in March 2018. Moreover, it is a three bedroom bungalow and 28% larger than the property. The sale of 4 Sambruck Mews in April 2015, three years before the valuation date, is also offered as evidence. The sale price of £355,000 was indexed upwards by 19.3% to account for that period and by 10% for size, offsetting downward adjustments for construction, location and parking to show a deceptively small net adjustment of 5%. This plethora of subjective adjustments reinforces the fact that the property is not a suitable comparable and therefore very little weight can be attributed to the sale as evidence.

37. 101 Ravensbourne Avenue was sold at the valuation date for £462,500 (£589/sq ft) but is located furthest from the property, in a pleasant residential area close to Bromley, less than half a mile from Ravensbourne station. It has a larger GIA than the property with only one bedroom because the second bedroom was converted into dining space. The plot is small, with little garden, but it does benefit from a garage and easy road access. In order to make it comparable with the property Mr Olden has adjusted by 30% to a value of £324,000 (£412/sq ft).

38. 8 Fenn Close also sold at the valuation date, for £470,000 (£661/sq ft), the highest unit price of all the bungalow comparables. It is situated at the end of a close of modern detached houses, half a mile from Sundridge Park station. The sales brochure refers to full refurbishment prior to sale. Mr Conboy has adjusted down by 22% to £366,000 (£514/sq ft).

39. The adjustments made by Mr Olden to the sales of 101 Ravensbourne Avenue and 8 Fenn Close are said by Mr Conboy to understate significantly the value of their good locations. Based on my own observations during inspection, I would agree with that comment and would go further to say that the differences are so great that the two sales can provide no more than a benchmark of bungalow prices at the valuation date.

40. That leaves 244a Verdant Lane, which is sufficiently close to the property for Mr Conboy also to consider it worthy of analysis, albeit his adjustments to the sale price of £340,000 produce a net reduction of 31% compared with Mr Olden’s net reduction of 8%. I agree with Mr Olden that Mr Conboy’s upward adjustment of £20,000 is not adequate to reflect the fact that the property was 20% larger than 244a. Substituting Mr Conboy’s £20,000 uplift for size with Mr Olden’s 15% increase, but retaining Mr Conboy’s other adjustments would give an adjusted price of £257,900. I consider this to be evidence which can be given strong weight.

41. Turning to Mr Conboy’s indicative evidence of sales of two bedroom flats and mid-terrace houses in the area I consider that, apart from the similar area of living space provided, there is little rationale for comparing a two storey mid-terrace house with a detached bungalow. The rational for comparing the single storey living space of a flat with a similar single storey living space in its own grounds is a little stronger.

42. I place minimal weight on 38 Forster House, which at 904 sq ft is a three bedroom maisonette with 34 % more floor space than the property. Of the remaining four flats, 47 Sandstone Road is some distance from the property, but the Scarlet Road and Castillion Road flats are very close, providing good evidence from the locality. 56 Scarlet Road is much smaller than the property and 73 Castillion Road is similar in size but has three bedrooms, so the best comparable flat sale is 9 Scarlet Road. This sold for a price, adjusted to the valuation date, of £235,475 (£371/sq ft).

43. I accept Mr Conboy’s evidence that the most likely purchaser of the property at the valuation date would be a cash investor, aware of the limitations of construction and life expectancy, but confident that there would be some tenants interested in renting a well maintained detached bungalow with the benefits of a garden and privacy. The investor would also be aware of the potential for extension and/or redevelopment on the plot and the value would therefore exceed that of 9 Scarlet Road and be more aligned with the adjusted price of 244a Verdant Lane.

44. I determine the market value of the property for compensation at £258,000 (£383/sq ft) and the associated home loss payment, 10% of market value, at £25,800.

Disturbance compensation

45. The principle of equivalence, which requires a claimant to be fully and fairly compensated for his loss following compulsory acquisition, was reviewed in detail by Lord Nicholls in Director of Buildings and Lands v Shun Fung Ironworks Ltd [1995] 2 AC 11. He confirmed that compensation should cover disturbance loss as well as the market value of the land itself, provided that three conditions are satisfied. Firstly, there must be a causal connection between the acquisition and the loss in question. Secondly, the loss must not be too remote from the acquisition. Thirdly, the claimant must have complied with their duty to mitigate their loss. To quote Lord Nicholls (at page 6):

“The law expects those who claim compensation to behave reasonably. If a reasonable person in the position of the claimant would have taken steps to reduce the loss, and the claimant failed to do so, he cannot fairly expect to be compensated for the loss or the unreasonable part of it. Likewise if a reasonable person in the position of the claimant would not have incurred, or would not incur, the expenditure being claimed, fairness does not require that the authority should be responsible for such expenditure.”

46. The claimant has relocated temporarily to accommodation provided by the acquiring authority at 18 Persant Road. It is her intention to purchase a replacement property once her compensation claim has been determined. She has therefore incurred costs associated with her temporary relocation and will incur further costs on her subsequent move to a permanent address. In addition there is a dispute as to the amount of professional fees which should be reimbursed to the claimant.

Temporary relocation costs

47. The total claim for temporary relocation costs amounts to £7,869.94 of which six items are agreed at a total of £3,415.99. The three items in dispute concern fixtures and fittings, a replacement sofa and replacement carpets.

48. The claimant paid the former occupant of 18 Persant Road for fixtures and fittings, including a refrigerator, wardrobe, curtains, fire and surround, fitted kitchen, light fittings and garden fencing, having been told that these items would otherwise be removed. An undivided lump sum of £2,500 was paid and the claim is for £2,000, to exclude a £500 allowance for the refrigerator. Mr Olden says that it was reasonable for the claimant to pay for these items to ensure that the property was in a habitable condition. Had some or all of the items been removed, it would have been more expensive for the claimant or the authority to replace them, so the potentially larger cost was mitigated.

49. The acquiring authority’s position, explained by Mr Conboy, is that under the terms of the tenancy the former occupier was not entitled to remove the fencing and fitted kitchen, which the claimant would have been told had she consulted with the landlord before paying for them. In the event that the former occupier had removed the fitted kitchen the landlord would have been obliged to install a replacement kitchen, to make 18 Persant Road habitable, so it was not the claimant’s responsibility to pay anything for it.

50. Regarding the wardrobe, curtains, fire and surround and light fittings, Mr Conboy says that the claimant could have brought similar items from the property on relocation but, now that she has paid for them, she has received value for money and can relocate them to her next property.

51. In considering the conditions for an eligible claim, I am satisfied that there was a causal connection between the expenditure and the acquisition of the property, and that in principle the loss is not too remote. However, the claimant has a duty to mitigate their loss and it would have been wise for the claimant to consult the council before paying a substantial sum to the previous tenant for the fitted kitchen and fencing. It is also a fair point that she now has the benefit of the other items which she can take with her on further relocation. I therefore assess that a reasonable claim for fixtures and fittings is represented by a contribution towards the costs incurred at £1,000.

52. The claimant could not relocate her old sofas from the property as they would not fit through the door of 18 Persant Road. The claimant spent six weeks without a sofa before purchasing a replacement from Ikea at a cost of £1,553.95, which is her claim. The residual value of her previous sofas, which had cost £4,500, is stated to be £2,000 but it is not clear what happened to these sofas after they were removed from the property when the acquiring authority took occupation.

53. There is disagreement between the parties as to whether there was a solution available to resolve the problem of relocating the old sofas. The acquiring authority say that their removals contractor was instructed to remove a window at 18 Persant Road, in order to relocate the sofas, but was prevented from doing so by the claimant cancelling their appointment. The claimant says that the contractors did not have the required insurance to remove the window. Email correspondence reveals that the claimant’s own removals company could have obtained the required insurance by pre-arrangement. Thus, whilst the claim has a loose causal connection with the acquisition, the claimant could have taken steps to mitigate her loss. Moreover, not only has she received value for money with her newly purchased sofa, it is not clear that she has foregone the residual value of her old ones. No compensation is awarded for this head of claim.

54. £900 is claimed for the cost of laying new carpets to the lounge, bedrooms and hall at 18 Persant Road to replace those in situ which were in poor condition and ‘threadbare’. The condition is disputed by the acquiring authority, who have asked for evidence of the poor condition. The acquiring authority also question why money has been spent on temporary accommodation, albeit the claimant has now been there over three years whilst disputing her compensation.

55. No evidence of the condition of previous carpets has been supplied, but I am satisfied that the expenditure meets the causal connection condition and was not too remote from the acquisition. Whether a reasonable person should have mitigated their loss by tolerating carpets which seemed to them to be in poor condition is a subjective judgement and I exercise discretion in favour of the claimant to award compensation of £900. The carpets will remain in situ when she relocates and the benefit will be retained by the acquiring authority and their next tenant.

56. In summary the amount of compensation awarded for temporary relocation costs is £5,315.99, reflecting the agreed amount of £3,415.99, together with £1,000 towards fixtures and fittings and £900 for carpets.

Permanent relocation costs

57. The principle of reimbursing the claimant for future relocation costs has been agreed between the parties, together with many of the itemised costs, including fees, totalling £3,250. difference between the parties is the amount of removal costs, although these can only be estimated at this stage. The claimant has received an informal quote for the cost of removal to Pembrokeshire of £2,880 (£2,400 plus VAT), which is the amount of her claim. Mr Conboy proposes that a sum of £2,000 would be reasonable. I determine that the claimant should receive the actual removal cost that she incurs in relocating, up to a ceiling of £2,880.

58. The parties have included in their assessments of the disturbance claim sums for SDLT, which in each case has been related to the assessment of market value. The actual amount of SDLT payable in future by the claimant will depend on the purchase price of her replacement property so I cannot determine a figure in this decision. However, I am satisfied that the principle of the claim is accepted by the respondent.

59. The total of permanent relocation costs awarded is £6,130, reflecting £3,250 previously agreed and £2,880 for removal.

Professional fees

60. Pre-reference professional fees have been agreed at £5,295.40 reflecting £3,695.40 for valuation advice up to 24 November 2020 and £1,600 for first stage legal fees.

Decision

61. I determine that the compensation payable to the claimant shall be as follows:

|

Head of claim |

Compensation |

|

Market value |

£258,000.00 |

|

Home loss payment |

£25,800.00 |

|

Disturbance: temporary relocation |

£5,315.99 |

|

Disturbance: permanent relocation |

£6,130.00 |

|

Professional fees |

£5,295.40 |

|

TOTAL before statutory interest |

£300,541.39 |

Costs

62. The claimant has incurred valuation fees of £3,071.25 plus VAT and legal fees of approximately £2,000 plus VAT in making and progressing this reference, which become costs of the reference. Ordinarily these would be reimbursed by the acquiring authority, but any submissions on costs should be made in accordance with rule 10(10) of the Tribunal’s Procedure Rules.

63. The acquiring authority made the reference and so will be responsible for the Tribunal’s fee.

Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

Member, Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

25 June 2021