Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Patrick v Thornham Parish Council (LAND REGISTRATION - PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE - FIRST REGISTRATION) [2020] UKUT 36 (LC) (19 February 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2020/36.html

Cite as: [2020] UKUT 36 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2020] UKUT 36 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LREG/151/2018

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

LAND REGISTRATION - PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE - FIRST REGISTRATION - JURISDICTION - ADVERSE POSSESSION - BOUNDARY DISPUTES

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPEAL AGAINST THE DECISION OF THE FIRST TIER TRIBUNAL (LAND REGISTRATION CHAMBER) UNDER S.11 OF THE TRIBUNALS COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

|

BETWEEN: |

|

|

|

|

MR JOCELYN BROWNLOW PATRICK |

Appellant |

|

|

and

|

|

|

|

(1) THORNHAM PARISH COUNCIL (2) STEPHEN WILLIAM BETT (3) JOHN STEPHEN GETHIN |

Respondents |

Re: All that land known as field 222, North of The Green,

Thornham,

Hunstanton,

Norfolk

Before: Judge Elizabeth Cooke

Determination of a preliminary issue

on written representations

Mr Paul Letman for the Appellant, instructed by Kenneth Bush Solicitors

Mr Andrew Gore for the Respondents, instructed by Hayes + Storr Solicitors

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2020

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Bean v Katz [2016] UKUT 168 (TCC)

Derbyshire County Council v Fallon [2007] 3 EGLR 44

Essex County Council v Essex Incorporated Congregational Church Union [1963] AC 808

Hallman v Harkins [2019] UKUT 245 (LC)

Inhenagwa v Onyeneho [2017] EWHC 1871 (Ch)

Jayasinghe v Liyanage [2010] EWHC 265 (Ch)

Lowe v William Davis Ltd [2018] UKUT 206 (TCC)

Maslyukov v Diageo Distilling Ltd [2010] RPC 21

Silkstone v Tatnall [2011] EWCA Civ 801

Introduction

1. Right up against the sea defences in the village of Thornham, on the north coast of Norfolk, is a field belonging to the appellant, Mr Patrick. As he puts it, King Neptune is his neighbour. The field is bounded on the south and east by ditches that drain into the sea to the north, and drainage is an important matter for the local landowners. The appellant has applied for first registration of his title to the field. Objections were made to his application for registration and the matter was referred to the Land Registration Division of the First-tier Tribunal (“the FTT”) pursuant to section 73 of the Land Registration Act 2002 (“the 2002 Act”).

2. The appellant has permission to appeal the FTT’s decision on that reference. On a practical level the appeal is about the ownership of the ditches to the south and east of the field, but legally the issues are not so straightforward. It has been agreed that the Tribunal will first determine a preliminary issue as to whether it has jurisdiction to hear that appeal, and this is my decision on that issue.

3. The appellant has been represented on the appeal by Mr Paul Letman, and the respondent by Mr Andrew Gore, both of counsel. I am grateful to them both.

The factual background and the procedural history

The field and the application for first registration

4. The appellant bought the field in 1984 from Mr Henry Bett (the second respondent’s father); it is not in dispute that it was conveyed to him on 16 October 1984.

5. I conducted a site visit on 4th June 2019; I am grateful to the parties and to their representatives for their assistance on that occasion. I was very struck by the dominance of water in the landscape and the instability of features such as hedges and ditches. I wonder whether the field will still be there in a few decades’ time. My description of the land is informed by what I have seen.

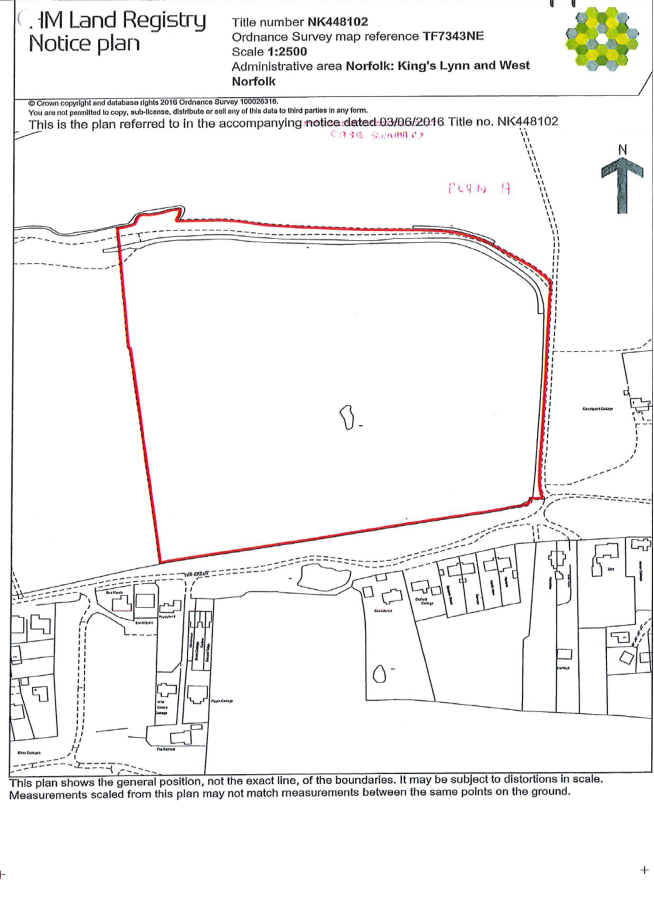

6. The field is rectangular, with the long sides on the north and south. Between the southern ditch and a road running east-west there is a grassy area known as The Green; it is a broad roadside verge rather than a conventional village green. To the east of the field there is an unmetalled track known as Shore Road running north-south. To the north the field is bounded by the sea wall - that is, a raised bank of earth that keeps the sea out. Beyond that, to the north, is a tidal area. The west side of the field borders another of the appellant’s fields. The FTT’s decision states that the land he seeks to register is as shown on the first of the two plans annexed to that decision, and which I have reproduced below; it is the plan that was attached to HM Land Registry’s case summary as a plan of the land sought to be registered.

<

<

7. It is important to note the words at the bottom of the plan:

“This plan shows the general position, not the exact line, of the boundaries. It may be subject to distortions in scale. Measurements scaled from this plan may not match the measurements between the same points on the ground.”

8. That is consistent with the “general boundaries rule” set out in section 60 of the 2002 Act which states:

“(1) The boundary of a registered estate as shown for the purposes of the register is a general boundary, unless shown as determined under this section.

(2) A general boundary does not determine the exact line of the boundary.”

9. In 1984, when the appellant bought the field, Thornham was not yet in an area of compulsory registration. He applied for voluntary registration of title in May 2015. HM Land Registry gave notice of the application to the owners of the adjoining land to the east and south, pursuant to rule 30(a) of the Land Registration Rules 2003.

10. Two objections were communicated to HM Land Registry on 21 June 2016 (I do not know why there was such a long time between the application for first registration and the giving of notice to neighbours), by letter from the solicitors who represent all the objectors. It is relevant to quote the letter, which said:

“1. Our clients agree the northern boundary.

2. The eastern boundary abuts the highway, the Local Highways Authority have set the line of the road. The road is 40 feet wide, which was set by the Enclosures Award. Therefore Patrick’s boundary must be at least 20 feet to the west of the centre of the road.

3. The south eastern corner of the boundary is incorrect. The boundary is curved with a small patch of rough land between the edge of the road and the boundary, as shown on the enclosed copy photograph and the old OS plan. The key point is the ditch is on the Common side, (our Clients’ side) and not Patrick’s side of the boundary, and the copy photograph enclosed proves this.

4. Our clients have no dispute over the southern ditch, provided Patrick accepts that the ditch forms part of our clients’ title, and therefore as green strip of common land between the highway and his boundary.”

11. Points 2 and 3 were made on behalf of the first respondent, Thornham Parish Council, which owns land to the east of Shore Road. In his written submissions Mr Gore concedes that point 3 is ambiguous but says that it was correctly understood by the appellant to state that the first respondent claims to own the ditch that runs north-south on the eastern side of the field, parallel with Shore Road. As will be seen the FTT made a decision about the southward and eastward extent of the field, so that there was no need for a separate decision about the corner.

12. Point 4 was made on behalf of the second and third respondents, Mr Stephen Bett and Mr John Gethin, who are the trustees of common land which includes The Green. Their case is that the ditch along the south of the field belongs with The Green.

13. Because it was not possible to dispose of those objections by agreement the matter was referred to the FTT pursuant to section 73(7) of the 2002 Act, about which there is more to say below.

14. It is important to note that the appellant’s title to the vast majority of the field is not in dispute. The dispute was about the ditch to the south, and about the position of the eastern boundary. Both ditches are some metres away from the edge of the road. It is equally important to note that the plan that accompanied the notice sent to the respondents by HM Land Registry as the proposed title plan gave no information about the ownership of the ditches because, as the plan itself stated, the red line on the plan denoted only a general boundary. It does not indicate exactly where the eastern boundary is, let alone how far it might be from the centre of Shore Road. The solid line inside the red edging on the eastern side of the field may or may not follow the ditch; similarly the red line to the south may or may not follow the ditch; in neither case does the plan show whether the ditch belongs with the field.

15. The respondents say that because this is an application for first registration the Tribunal is not concerned with the general boundaries rule. Certainly the rule does not apply to unregistered land; but the dispute in this case is about the land that is going to be registered, and the title plan proposed to be used. In any event the applicant has not produced any more precise plan. The FTT’s decision was about the proposed title plan and gave a direction to the registrar that referred to the plan, and it is that decision and direction that is or are under appeal.

The decision of the First-tier Tribunal

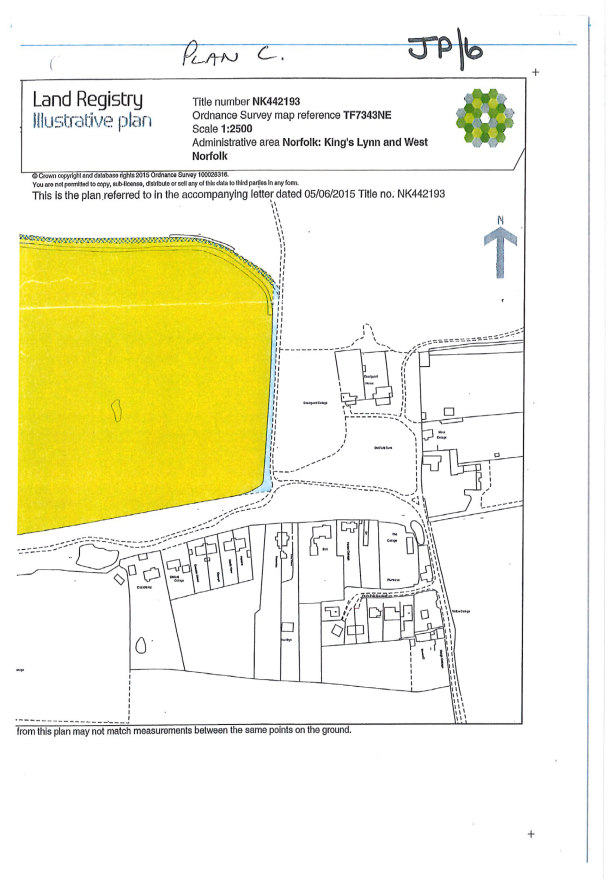

16. The FTT conducted a site view on 22 May 2018 and a hearing on 23 and 24 May 2018. In his written decision the judge identified the land sought to be registered by reference to the plan that I have already reproduced, and referred to it as “the red land”. He set out the two objections to the first registration, explaining that the respondents accept that the appellant is entitled to be registered with title to the majority of the red land but that the first respondent “asserts that it has a paper title to a strip along the eastern edge of the red land (“the eastern strip”) and denies that its title has been defeated by any adverse possession of Mr Patrick”. The judge annexed a further plan showing the eastern strip coloured blue, and I reproduce that plan here:

17. The provenance of that plan has not been explained; it will be recalled that the original objection to HM Land Registry was expressed in terms of a measurement from the centre of the road. It will be seen that the blue strip runs between the solid line (inside the red edging) and the pecked line that marked the outside edge of the red edging. There appears to have been no argument before the FTT, nor was there any decision made by the FTT, as to what those two lines represent (I note that Shore Road, being unmetalled, does not have a clearly defined edge; there is a grass verge in which the stumps of old trees can be discerned, then vegetation in the form of bushes and saplings). Beyond that there is a ditch. Nor was there any evidence, or any decision made, about the width of the eastern strip.

18. The judge explained that the appellant put his case in two ways: first that he had a paper title to the southern ditch and the eastern strip, and second, if it was found that he did not have a paper title, that he was entitled to be registered with a possessory title to both by virtue of adverse possession. The parties’ arguments on those issues, and the reasons why the judge decided as he did, are not relevant to my decision on this preliminary issue; what matters is whether the FTT has made decisions about the southern ditch and the eastern strip that can be appealed to the Tribunal, and that depends upon the precise nature of what the judge decided and its legal effect (and not upon whether what he decided was right or wrong as a matter of fact or law).

19. The judge found that the appellant did not have a paper title to the eastern strip.

20. Then he considered the paper title to the southern ditch. Before doing so he said this:

“41. A question not raised by anyone at the hearing (including myself) is what was the purpose of the trustees telling Land Registry in their letter dated 21 June 2016 that the trustees objected to the original application, but only in respect of the ditch on the southern side (the southern ditch)?

42. This is because the ditch is too small to be shown by a line drawn on an Ordnance Survey plan. Indeed Land Registry wrote to the respondents on 2 April 2017 stating:

… pursuant to s60 of the Land Registration Act 2002 the red edging on a title plan will not determine the ownership of a boundary feature such as a ditch.”

21. The judge set out section 60, as I did at paragraph 8 above, and pointed out that a party who wishes to have an exact line of a boundary recorded must apply in form DB1 for a determined boundary. He then said:

“45. It therefore seems to me that, whether or not I find that the ditch belongs to Mr Patrick, the southern line on plan 1 is the correct line to be drawn. That line does not determine whether or not Mr Patrick owns the ditch.

46. There are cases where the differences between the general boundary and the true boundary are so great that it is a worthwhile exercise to alter the register to show a more accurate general boundary. This is not such a case. However, the parties have spent time and resources on this question, so I will endeavour to decide it.”

22. The judge referred in a footnote to Derbyshire County Council v Fallon [2007] 3 EGLR 44 where Nugee J at paragraph 33 said:

“if the registrar or Adjudicator has determined that the boundary is in the wrong place, it can be expected that the filed plan will be altered to show the boundary more accurately.”

The judge did not say why he felt that it was not worthwhile to direct the registrar to indicate, whether on the plan or by way of a note on the register, whether the ditch belonged to the appellant.

23. The judge found that the appellant did not have a paper title to the southern ditch.

24. Next the judge turned to adverse possession, and found that the appellant had not acquired title by adverse possession either to the eastern strip or to the southern ditch.

25. The judge concluded:

“86. I will therefore direct the chief land registrar to give effect to the original application, save for the land coloured blue on plan 2”,

adding in a footnote that the land coloured blue “is the eastern strip. Although I have found that Mr Patrick does not have either a good paper or possessory title to the southern ditch, I have explained in paragraph 45 above that this has no effect on the position of the general boundary shown on the title plan”.

26. The appellant applied to the FTT for permission to appeal both the decisions on the paper title and the decisions on adverse possession. The FTT gave permission in respect of grounds 2, 3 and 4, which referred to the paper title to the southern ditch and to the decisions about adverse possession, and refused permission on ground 1 which was about the paper title to the eastern strip.

27. The appellant filed a Notice of Appeal with the Tribunal in respect of grounds 2 to 4, but also renewed his application for permission to appeal on ground 1. On 21 December 2018 the Deputy President directed that the permission application and the appeal were to be consolidated, that the permission application would be determined at the hearing of the appeal and that, if permission was granted, that ground would be considered as part of the appeal. The appeal was listed for hearing on 5 June 2019.

28. At the start of the hearing, having seen the land the previous day and reflected on the papers, I asked counsel (with apologies for springing the point upon them) to consider whether the Tribunal could hear the appeal in respect of the southern ditch, in view of the nature of the decision made by the FTT. It was agreed that the appeal should be adjourned in order to enable counsel and the parties time to think about that and about whether the eastern strip might give rise to a similar problem.

29. The parties subsequently agreed that the question whether the Tribunal has jurisdiction to hear an appeal of the decisions about the southern ditch or the eastern strip would be determined as a preliminary issue, and on 19 September 2019 I directed that that preliminary issue would be determined on written representations. I have received helpful written representations from both counsel.

30. Mr Letman for the appellant, now says that the FTT had no jurisdiction to make decisions either about the southern ditch or about the eastern strip; alternatively if it had, he says that those decisions do not create an issue estoppel (which would mean that they are of no legal effect and do not prevent the litigation of the dispute in the future).

31. In the paragraphs that follow I examine first the authorities relating to the jurisdiction of the FTT and then consider the parties’ arguments about jurisdiction. I then move on to issue estoppel which, as will be seen, is relevant only to the southern ditch.

The jurisdiction of the FTT

32. The FTT is, of course, a creature of statute with no inherent jurisdiction. It is worth going through the statutory provisions and authorities about the scope of its jurisdiction in land registration references.

33. Section 73(7) of the 2002 Act provides that where the registrar is not satisfied that an objection is groundless, and it is not possible to dispose of an objection by agreement:

“… the registrar must refer the matter to the First-tier Tribunal.”

34. Section 108(1) of the 2002 Act says that the FTT:

“has the following functions:

(a) determining matters referred to it under section 73(7)…”

35. When a reference is made the registrar sends a notice of reference to the FTT, accompanied by a case summary, pursuant to rules 3 and 5 of the Land Registration (Referral to the Adjudicator to HM Land Registry) Rules 2003. The case summary sets out the parties’ names, addresses, and legal representatives, summarises the core facts, the application and the objections, and sets out a list of accompanying documents (which will usually be those sent by the applicant to the registrar). The applicant and the objector are given the opportunity to comment on a draft of the case summary before it is sent to the FTT, pursuant to rule 3(2) of those rules.

36. That is what goes in to the FTT when a reference is made. What comes out? Rule 40 of the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Property Chamber) Rules 2013 sets out what the FTT is to do in disposing of a land registration reference:

“40(1) The Tribunal must send written notice to the registrar of any direction which requires the registrar to take action.

(2) Where the Tribunal has made a decision, that decision may include a direction to the registrar to—

(a) give effect to the original application in whole or in part as if the objection to that original application had not been made; or

(b) cancel the original application in whole or in part.

(3) A direction to the registrar under paragraph (2) must be in writing, must be sent or delivered to the registrar and may include—

(a) a condition that a specified entry be made on the register of any title affected…

37. So the FTT is not limited to saying yes or no to an objection. It may direct the registrar to give effect to, or to cancel, the application in whole or in part; and the power to add a condition that a specified entry be made on the register enables further nuance in the direction given to the registrar. For example, the registrar may be directed to register a determined boundary in accordance with the application made save for one section of the boundary, where the registrar is directed to follow a different line (Bean v Katz [2016] UKUT 168 (TCC)). It is perhaps worth adding that it is the FTT’s practice to give a direction to the registrar, and to hand down separately a decision that sets out the reasons for that direction; the decisions seen on Westlaw, Bailii and the like are the latter, not the direction itself, but the decision normally sets out what that direction is.

38. In Jayasinghe v Liyanage [2010] EWHC 265 (Ch) the applicant wanted to have a Form A restriction entered on the objector’s title to protect her claimed beneficial interest. The registered proprietor objected on the ground that she had no such interest. The deputy adjudicator (in the days before the adjudicator’s jurisdiction was transferred to the FTT) decided that she had no beneficial interest in the property and directed that her application be cancelled. She appealed on the basis that he had no jurisdiction to make that decision; she argued that the adjudicator was empowered by the statute only to decide if the restriction should be entered, and to that end all he had to do was to decide if she had an arguable claim (since a “claim” can be protected by a restriction, section 42(1)(c) of the Land Registration Act 2002). The High Court rejected that argument.

39. Briggs J explained that the rules governing procedure before the Adjudicator (their modern counterpart is the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Property Chamber) (Rules 2013) enabled the adjudicator “to resolve, where necessary, disputes about substantive rights, rather than merely to conduct a summary process designed to ascertain whether there exists an arguable claim” (paragraph 14). Accordingly, what was referred to the adjudicator was not merely the question whether the applicant had a right or claim, but whether the entry of a restriction was necessary or desirable to protect it. “Both of those questions fall within what is described in section 73(7) as “the matter” to be referred to the adjudicator” (paragraph 16). He went on:

40. So the adjudicator, and now the FTT, is to dispose of the objection, and to determine the matter referred. What is “the matter”? In Jayasinghe:

41. To summarise: the High Court in Jayasinghe held that the nature of the matter referred is fact-specific (paragraph 18), and that the disposal of objections is an integral part of the matter referred (paragraph 31).

42. In Silkstone v Tatnall [2011] EWCA Civ 801 the appellants had objected to the cancellation of a unilateral notice protecting their claimed right of way over the registered proprietor’s title. Because they had difficulty in tracking down a witness, they purported to withdraw their case on the day of the hearing, with the express intention of pursuing their case in court at a later date. The deputy adjudicator refused them permission to withdraw, conducted a trial, and decided that they had no easement; that decision of course meant that the objectors would be unable to bring a fresh action later. On appeal they argued that he had no jurisdiction to determine the reference in those circumstances. In the High Court the appeal was dismissed; Floyd J said:

43. The Court of Appeal likewise dismissed the appeal. Rimer LJ said:

“A reference to an adjudicator of a “matter” under section 73(7) confers jurisdiction on the adjudicator to decide whether or not the application should succeed, a jurisdiction that includes the determination of the underlying merits of the claim that have provoked the making of the application.”

44. However, the FTT’s jurisdiction is conferred by statute and is not without limits. The FTT must decide, and may only decide, the matter referred to it. As Morgan J put it in Inhenagwa v Onyeneho [2017] EWHC 1871 (Ch) at paragraph 62, the FTT:

“should not determine the merits of other disputes between the same parties, even disputes relating to the same registered title, if those disputes are different from the matter referred for determination.”

45. It follows from that that the FTT does not have jurisdiction to make decisions that cannot be the subject of an entry in the register, such as the quantification of beneficial interests (Hallman v Harkins [2019] UKUT 245 (LC)). Moreover, where the FTT does not have jurisdiction the parties cannot confer jurisdiction upon it by consent. As the Deputy President put it in Hallman at paragraph 53:

“The respect which a statutory tribunal is required to show to the limits of its jurisdiction, and the inability of the parties to enlarge those limits, are illustrated clearly by the decision of the House of Lords in Essex County Council v Essex Incorporated Congregational Church Union [1963] AC 808, which concerned the powers of the Lands Tribunal, conferred by the Town and Country Planning Act 1959, to determine disputes over the purchase by a local authority of land affected by certain planning proposals. The Tribunal was empowered by the relevant statutory provision to “consider the matters set out in the notice served by the claimant and the grounds of objection specified in the counternotice” served by a local authority. An objection to a purchase notice served by a land owner on an authority had been determined by the Tribunal and by the Court of Appeal, and had reached the House of Lords, despite the objection not having featured in the authority’s counter-notice. Lord Reid, (with whom the other judges agreed) said, at p.816, that the Lands Tribunal “had no jurisdiction to do anything more in this case than to determine whether the objection in the appellants’ counternotice should or should not be upheld.” It did not matter that the land owner had failed to raise the jurisdictional point at an earlier stage because, as Lord Reid explained:

‘ … it is a fundamental principle that no consent can confer on a court or tribunal with limited statutory jurisdiction any power to act beyond that jurisdiction…’”

The parties’ arguments about the FTT’s jurisdiction

46. The appellant argued that the FTT had jurisdiction only to determine the application for first registration on the basis of the appellant’s paper title, because that was what he had applied for. The “matter” to be referred is defined, says Mr Letman, in the notice of referral sent by HM Land Registry to the FTT, and the accompanying case summary, which said that the applicant claimed to have acquired title to the property by virtue of the 1984 conveyance. Accordingly, says Mr Letman, “it is submitted that ‘the matter’ referred was solely the appellant’s application for first registration of his title by virtue of the 1984 Conveyance.” The FTT had no business making decisions about the southern and eastern boundaries because the general boundaries rule was going to apply. Nor had it any jurisdiction to make any findings about title by possession; it had jurisdiction only to decide whether the appellant had a paper title to the field because that was what he produced to HM Land Registry.

47. In support of that argument Mr Letman relies on the House of Lords’ decision in Essex County Council v Essex Incorporated Congregational Church Union [1963] AC 808. It will be clear from what I said at paragraph 45 above that that is an important decision on the limits of a statutory jurisdiction; but when we turn to the specifics of the jurisdiction in issue in that case some caution is necessary.

48. As Mr Letman says, the Essex case concerned the jurisdiction of the Lands Tribunal conferred by the Town & Country Planning Act 1959, in connection with the compensation of landowners affected by certain planning proposals. The statutory scheme provided for an owner to serve a notice requiring the purchase of the affected land and the acquiring authority to serve a counter-notice setting out its grounds of objection. If the parties could not agree, the matter could then be referred to the Lands Tribunal under section 41(2) of the 1959 Act for it to ‘consider the matters set out in the notice ... and the grounds of objection specified in the counter-notice.’ Section 41(4) provided that ‘If the tribunal determines not to uphold the objection, the tribunal shall declare that the notice ... is a valid notice.’

49. The acquiring authority’s counter-notice relied upon one ground of objection (item (f) in the statutory list); but before the Tribunal the authority raised and relied upon ground (e). That ground was rejected by the Tribunal, and the authority appealed. The House of Lords held that the Tribunal had had no jurisdiction to consider ground (e). It concluded that the tribunal ‘had no jurisdiction to do anything more in this case than to determine whether the objection in the appellant’s counter-notice should or should not be upheld’ (Lord Reid at p.820) (and as noted above, that jurisdiction could not be widened by the consent of the parties).

50. Mr Letman submits that the same principle applies to the FtT and in turn to this Tribunal so that neither can have jurisdiction beyond ‘the matter’ referred to the FTT (under rule 5 of the Land Registration (Referral to the Adjudicator to HM Land Registry) Rules 2003) for decision. That of course is right, but it begs the question: what is the matter referred? The Town and Country Planning Act 1959 was very specific: the statutory conferral of jurisdiction to consider “the grounds of objection specified in the counter-notice” precluded any jurisdiction to consider grounds of objection that were not set out in the counter-notice. By contrast the “matter” referred to the FTT is not defined in that way in the 2002 Act. The 2002 Act does not say that the FTT is restricted to consideration of a particular document, such as an objection, the application, or the case summary.

51. I acknowledge that Morgan J in Inhenagwa at paragraph 42 says “ ‘The matter’ referred to the adjudicator is defined in the notice of referral given by r.5 of [the Adjudicator to Her Majesty’s Land Registry (Practice and Procedure) Rules 2003]”; but in using the word “defined”, Morgan J must be taken to have meant something other than a definition of the scope of the matter. Rule 5 of those rules (which have now been superseded) sets out what the adjudicator was to do on receipt of a notice of reference, but does not state what “the matter” is.

52. Nor can the matter referred be defined by the case summary provided to the FTT by HM Land Registry on making the referral. As we have seen (paragraph 35 above), that document sets out the core facts, the application and the objections, but it is simply a summary. The statute does not define the FTT’s jurisdiction by reference to that summary.

53. That is why there has been litigation about the scope of the “matter”, and that is why the higher courts have said that the FTT has jurisdiction to decide “the underlying merits of the claim that have provoked the making of the application” (Rimer LJ in Silkstone, quoted above at paragraph 43).

54. Mr Letman argues that the FTT had no jurisdiction to consider adverse possession because the application referred only to the paper title. As Mr Gore points out, it has been the practice of the FTT to permit evidence of adverse possession on a reference relating to first registration, where the paper title has been challenged. I have been referred to one decision in which that was done, and I am aware of others. But the question is whether that practice is correct, and the FTT’s own decisions are not authoritative on the point. I take the view that the practice is clearly correct. The application is for first registration. It was made on Form FR1 as is usual, and the evidence provided to the registrar was the paper title. But title to unregistered land is founded ultimately on possession and where a paper title is challenged a landowner has to resort to proof of possession. The idea that he cannot do so in this case because he did not mention adverse possession on his application form - before any challenge was raised - is implausible. What is said to the registrar in an application form does not restrict the parties’ arguments in subsequent litigation. There is no authority for the idea that it restricts the jurisdiction of the FTT. What does confine its jurisdiction is the requirement that it confine itself to the matter referred to it, namely the appellant’s claim for first registration of title to the field, in the manner described in the authorities, particularly Jayasinghe and Silkstone.

55. Mr Letman then says that the position of the southern and eastern boundaries was outside the FTT’s jurisdiction because the general boundaries rule made them irrelevant. On that basis of course the referral was pointless. The argument ignores both the fact that the disposal of objections is “an integral part of the matter referred to the Adjudicator under section 73(7)” (Briggs J in Jayasinghe at paragraph 17, quoted at paragraph 39 above), and the FTT’s power to make directions about the general boundaries. It can require the registrar to alter the plan so as to make it more accurately reflect the general boundaries, as it did in Fallon (paragraph 22 above). Accordingly, since there were directions that the FTT could make about the boundaries despite the general boundaries rule, and since the objections related to those boundaries, the FTT’s jurisdiction was squarely engaged.

56. In my judgment the FTT had jurisdiction to make a decision about the extent of the land claimed, including the position of its general boundaries, and to do so on the basis of the full range of the respondent’s arguments, both as to paper title and as to possessory title in the alternative. That is not where the difficulty lies. The question is whether the FTT did in fact make an appealable decision about either the southern ditch or the eastern strip, as I shall explain on considering the two decisions.

The eastern strip

57. The FTT made a direction to the registrar about the eastern strip. Its order changed the plan that was to become the title plan. In order to make that order the FTT made findings about the extent of the paper title and about the appellant’s case on adverse possession. I have already explained why in doing so the FTT was making findings about the “matter” referred to it. The effect of the order certainly did not determine the exact line of the boundary pursuant to section 60 of the 2002 Act; the judge did not say that he was creating a determined boundary, and the plan is not sufficiently accurate to do so. Accordingly the effect of the direction was to make the line on the plan represent more accurately the general boundary (as did the direction in Fallon, see paragraph 22 above). The plan, as amended pursuant to the FTT’s direction, shows that the extent of the land is smaller than that applied for, and that its eastern extremity probably does not line up with the edge of the road (insofar as that road has a clean edge, which inspection demonstrates to be limited). I see no difficulty in finding that there was jurisdiction to make this order. The decision fell squarely within the matter referred to the FTT. It made an order within its jurisdiction and that order can be appealed. What exactly that order meant can be explored on appeal.

58. The appellant has permission to appeal the FTT’s findings about adverse possession of the eastern strip but the FTT refused him permission to challenge its decision about his paper title to the eastern strip. I have not yet heard submissions about whether he should have permission to appeal on that ground.

59. I would add, however, that the determination of an appeal about the eastern strip in the absence of precise plans will still result only in a general boundary and is therefore unlikely to resolve the parties’ dispute. I fail to see how a decision on appeal can determine ownership of the eastern ditch, any more than did the decision of the FTT, since it is not known where the ditch lies in relation to the lines on the plan used by the FTT.

60. Mr Gore says that the parties agree that the line on the plan marking the western extent of the eastern strip denotes the ditch, but Mr Letman says that there is no agreement that the ditches were shown on the plan. No doubt there has been a misunderstanding between counsel about whether there was such an agreement; but at any rate no such agreement is recorded in the FTT’s decision, and it is not clear to me what effect, if any, such an agreement would have if it happened to be incorrect as a matter of fact. The FTT did not make a finding of fact that the line on the plan denotes the ditch. If it does, is it the centre of the ditch? Or one of its edges? If so, where was that edge when the plan was drawn? The FTT could have directed the registrar to add to the verbal description of the land a note to the effect that the eastern ditch was excluded; it did not do so. The registrar could make such a note of his own initiative, but it would be his own decision to do so (and any challenge to that decision could only be made by an application for permission to seek judicial review).

61. If the parties want to know whether the appellant owns the eastern ditch they will need to take a different course. One way forward would be to compromise the appeal, allow the registration to proceed, and for one or other party to apply for the determination of the boundary under section 60 of the 2002 Act on the basis of accurate plans. The preparation of plans will be expensive (as has been the parties’ failure to have accurate plans prepared to date) and it will be for the parties to decide whether it is worth taking that step.

The southern ditch

62. It follows from what I said at paragraph 56 that the FTT did have jurisdiction to make a decision about the southern ditch. But it did not express its finding in a direction to the registrar.

63. Mr Gore argues that in making its finding that the appellant does not own the southern ditch the FTT determined one of the questions it was asked to decide. That determination, he says, can be reflected on the register by a note in the verbal description of the land to the effect that the southern ditch is not included in the registered title. The FTT could have made such a direction, but it chose, deliberately (see paragraph 21 above), not to do so, and no requirement or expectation that the registrar make any entry about the ditch was expressed in the decision. If the registrar chooses to make such an entry that is his own decision, and can be challenged by judicial review. The direction that the FTT did make was about the field as a whole and about the eastern ditch, and there is nothing in that direction that the appellant could point to as a proposition about the southern ditch that he disagrees with and that he wishes to appeal.

64. Section 111 of the 2002 Act gives a right of appeal to “a person aggrieved by a decision of [the FTT]” and that section 11 of the Tribunals Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 gives a right of appeal “on any point of law arising from a decision made by [the FTT]” (emphasis added). In the absence of any direction about the southern ditch, did the FTT make a decision about the southern ditch that is capable of being appealed?

65. In order to answer that question I have to explore the nature of the FTT’s finding about the southern ditch, and in particular to decide whether it created an issue estoppel. If it did, it binds the parties in any future proceedings and (to anticipate the words that I quote at paragraph 76 below) “then it may be that the Upper Tribunal will be prepared to hear an appeal against those findings of the FTT.” If it did not then it has no legal effect and so, as I shall explain, is unlikely to be appealable. It will be helpful first to look at the relevant authorities about issue estoppel.

Issue estoppel: the law

66. In Inhenagwa Morgan J had to consider whether the FTT had made a decision in a land registration case that created an issue estoppel in the county court. The action in the county court was brought by a claimant who had applied to HM Land Registry for a restriction to protect her claimed beneficial interest in property registered in the name of her sister. I refer to the parties as Rita (the claimant) and Rose (her sister), as did Morgan J. The FTT found that Rita was entitled to the entry of a restriction to protect her right to apply for rectification of the register, because the property had originally been registered in the names of Rita and Rose, but Rose had forged Rita’s signature on a transfer into Rose’s sole name. The FTT made a number of further findings of fact about what had happened between the two sisters, including in particular discussions between them when the property was purchased. In the county court the claimant sought rectification of the register, a declaration that she and her sister owned the property in equal shares, and an order for sale. The recorder held that the FTT had already made a decision as to the claimant’s beneficial interest (that the claimant held a half share), and that there was no need for her to hear evidence and nothing for the county court to determine as to the beneficial ownership.

67. On appeal, Morgan J in the High Court found (at paragraph 55) that the FTT had not in fact made a decision about the beneficial ownership. However, it was argued that the FTT’s findings of fact (about what happened when the property was purchased and the dealings between the two sisters) themselves created an issue estoppel. Accordingly Morgan J went on to consider the status of those findings.

68. At paragraph 47 Morgan J said:

“Before the result of earlier proceedings before a judicial tribunal can give rise to an issue estoppel, there must obviously be “a decision” on the point that is later in issue. Further, the matter which was decided on the earlier occasion must be the identical issue to that which is involved in the subsequent litigation. Yet further, the decision on a point in the earlier proceedings must have been necessary to the result of the first proceedings before it will give rise to an issue estoppel.”

69. Morgan J referred to and quoted from a number of authorities to support those propositions, and I need not travel the same ground here. The following passage from Spencer Bower and Handley, Res Judicata 4th edn, (London, LexisNexis, 2009) at p.179 will suffice:

“Only determinations which are necessary to the decision, which are fundamental to it and without which it cannot stand - will found an issue estoppel. Other determinations, without which it would still be possible for the decision to stand, however definite be the language in which they are expressed, cannot support an issue estoppel between the parties between whom they were pronounced.”

70. In the light of that, Morgan J analysed the factual findings of the FTT as follows:

“58. … the relevant findings of fact were not necessary to the decision as to whether the 202 transfer was a nullity and whether Rose was entitled to the rectification of the register. Instead, the adjudicator made these findings as part of the background to the 2002 transfer in order to make her findings as to that transfer. … the findings of fact related to “evidentiary facts” and not to “ultimate facts”.

71. Accordingly, the findings of fact that the FTT had made in Inhenagwa did not create an issue estoppel.

Did the FTT’s findings about the southern ditch create an issue estoppel?

72. Turning to the present appeal, in order to decide whether the decision about the southern ditch created an issue estoppel it is helpful to work backwards from the FTT’s determination of the reference itself. It directed the registrar to give effect to the application for first registration, albeit with an adjustment to the eastern strip. The decision that the judge made about the southern ditch was not, obviously, an “ultimate fact” that he needed to decide before he could make that direction. It was not even an evidentiary finding. Indeed, I think the judge himself recognised this when he made the comments that I quoted above at paragraph 21.

73. Accordingly I take the view that the decision the FTT made about the southern ditch did not create an issue estoppel and cannot be appealed. Its status is that of an expression of personal opinion by the judge. It has no legal effect.

74. And that is why I expressed doubt, at the original hearing of this matter, as to whether it was possible for me to hear an appeal of the decision about the southern ditch.

Can the Tribunal hear an appeal from the decision about the southern ditch?

75. Lowe v William Davis Ltd [2018] UKUT 206 (TCC) was an appeal from a decision of the FTT on a determined boundary application. The facts need not concern us here; but Morgan J’s observations about issue estoppel are important. He started (at paragraph 56) from Inhenagwa and the proposition that “not every finding of a court or a tribunal which is within its jurisdiction gives rise to an issue estoppel”. That, as discussed, is the position here; the FTT had jurisdiction to make a decision about the southern ditch, but it chose to do so in a way that did not create an issue estoppel.

76. At paragraph 58 Morgan J said this:

“If the FTT makes findings which are within its jurisdiction and those findings will give rise to an issue estoppel in other proceedings, then it may be that the Upper Tribunal will be prepared to hear an appeal against those findings of the FTT. However, if the relevant findings do not affect the order made by the FTT and could not themselves be the subject of an order of the FTT and do not give rise to an issue estoppel, then I would question whether those findings could, or should, be made the subject of an appeal to the Upper Tribunal. … In Maslyukov v Diageo Distilling Ltd [2010] RPC 21 at [55]-[57], it was held, in relation to a statutory scheme which had many similarities to the scheme with which I am concerned, that certain findings of fact by the lower tribunal did not give rise to an issue estoppel and there was no ability to appeal against those findings when the ultimate decision in the case went in favour of the intended appellant. I consider that that authority should be followed in an ordinary case of a proposed appeal to the Upper Tribunal where the proposed appeal related to a finding which was not binding on the appellant.

77. Morgan J went on to consider special circumstances that might justify such an appeal; the example he gave was a decision in care proceedings in which the court had made findings of fact which did not create an issue estoppel between the parties but would have had a disastrous effect upon the reputation and career of an individual.

78. The decision relating to the southern ditch did not create an issue estoppel. The parties are free to take fresh proceedings about its position, for example by an action for a declaration as to the position of the boundary or by making an application to HM Land Registry for a determined boundary under section 60 of the 2002 Act which could then be referred to the FTT. But the FTT’s finding about the southern ditch did not create an issue estoppel; nor therefore would any decision about it by the Tribunal. In those circumstances it is pointless for the finding to be appealed and I find that it was not an appealable decision.

79. It may be helpful to repeat what the Deputy President said in Hallman v Harkins about a decision made by the FTT that was not binding on the parties:

“76. … All that has been achieved by it is the creation of expectations and concerns in the minds of two parties which may or may not prove to be justified on proper consideration of all the relevant circumstances.

78. It is not the function of courts or tribunals to express non-binding opinions, and parties who would be assisted by an informed view may utilise one of the forms of alternative dispute resolution available to them.”

Conclusion

80. It follows from what I have said above that the conclusion of the preliminary issue is as follows:

a. The FTT did not make an appealable decision about the southern ditch of the field, and the judge’s expression of his view about the ownership of the ditch did not create an issue estoppel.

b. The FTT made an appealable decision about the eastern strip.

81. I invite the parties to agree directions as to the future progress of the appeal of the decision about the eastern strip. Those directions are to provide for the respondents to make submissions about the outstanding permission application in relation to the paper title; they are also to include the provision of agreed up-to-date plans at a larger scale than those made available to the FTT, indicating the position of all the physical features that the parties will be referring to in the appeal. However, I express the hope that before doing that the parties will give proper consideration to my comments at paragraphs 59 and 60 above.

Judge Elizabeth Cooke

19 February 2020