Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Witt v Woodhead (LAND REGISTRATION - BOUNDARY DISPUTES - construction of conveyance - straight line boundary) [2020] UKUT 319 (LC) (18 November 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2020/319.html

Cite as: [2020] UKUT 319 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2020] UKUT 319 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LREG/51/2019

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

LAND REGISTRATION - BOUNDARY DISPUTES - construction of conveyance - straight line boundary - usefulness of computer-generated lines - party wall - fence posts

AN APPEAL AGAINST A DECISION OF THE FIRST TIER TRIBUNAL (PROPERTY CHAMBER)

|

BETWEEN: |

|

|

|

|

Mr Shaun Charles Witt |

Appellant |

|

|

and |

|

|

|

(1) Adrian Paul Woodhead (2) Jennifer Aimee Woodhead

|

Respondents |

|

|

|

|

Re: 82 & 84 Heatherstone Avenue,

Dibden Purlieu,

Southampton,

Hampshire, SO45 4JZ

Judge Elizabeth Cooke

28 August 2020, Royal Courts of Justice

and

30 October 2020 by Skype for Business

Mr Simon Williams for the appellant, instructed by Clive Sutton solicitors.

Ms Tahina Akther for the respondents, instructed by Scott Bailey

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2020

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Bean v Katz [2016] UKUT 168 (TCC)

Hawkes v Howe [2002] EWCA Civ 1136

Lanfear v Chandler [2013] EWCA Civ 1497

Lowe v William Davis Ltd [2018] UKUT 206 (TCC)

Pennock v Hodgson [2010] EWCA Civ 873

Introduction

1. This is an appeal from the decision of the Land Registration Division of the First-tier Tribunal (“the FTT”) on Mr and Mrs Woodhead’s application for a determined boundary pursuant to section 60 of the Land Registration Act 2002. The FTT directed the registrar to give effect to the application as if the objection made by their next-door neighbour, Mr Witt, had not been made. Mr Witt has appealed that decision.

2. Permission to appeal was granted by HHJ David Hodge sitting as a Deputy Judge of this Tribunal, and he directed that the appeal be by way of re-hearing.

3. I had the benefit of a site visit on 15 August 2020; I am grateful to the parties for letting me see inside their houses and in their gardens. The appeal was listed for hearing in the Royal Courts of Justice on 28 August 2020; it should have been listed for two days, and at the end of the day it was agreed that the second day’s hearing would take place by remote video platform, which it did on 30 October 2020. The appellant, Mr Witt, was represented by Mr Simon Williams, and the respondents. Mr and Mrs Woodhead, by Ms Tahina Akther; I am grateful to them both. In writing this decision after the second day’s hearing I am grateful to the parties for arranging for me to have a transcript of the first day.

4. I heard evidence from Mr and Mrs Woodhead and from Mr Witt. I accept that they all told the truth as they saw it. Inevitably recollections can fade when events took place a couple of decades ago, and that causes difficulties when significance is attached, now, to details that may scarcely have been noticed at the time. The parties have had a bitter disagreement about the state of the fencing in the back garden, and that has coloured their views of each other and of past events. They all did their best, but I am not able to accept all the factual evidence I heard.

5. By way of expert evidence Mr and Mrs Woodhead called Mr Kim Moreton MRICS of David J Powell Surveys Limited. Mr Witt called Mr Carl Calvert FRICS. Both are experienced surveyors, and were impressive witnesses of great technical ability and understanding who did what they were instructed to do with the impressive technology at their disposal. I am grateful to them both for their careful and clear explanations. It is worth noting that even though the expert evidence involved a detailed consideration of plans at various scales, there was no difficulty in hearing it remotely. In the end, I am not able to find that either drew a line that represents the boundary. That is because the boundary between these properties is a pretty much straight line created by the builders in 1960, rather than a perfectly straight line created by a computer programme in 2020.

6. In the paragraphs that follow I begin by reviewing the law relating to boundaries in registered land and to boundaries in general. I then describe the parties’ properties and the determined boundary sought by Mr and Mrs Woodhead, and I explain why Mr Witt objects to it. It became clear in the course of the hearing that two physical features are of particular importance to the parties; one is the mortar joint in the back wall of the houses, and the other is the fence post on the boundary at the bottom of the gardens. I discuss those features and the evidence about them; I then turn to the expert evidence, and finally to the fencing in the back garden before summarising my findings and my conclusion.

The law relating to the determination of boundaries

7. The boundary on a registered title plan is a general boundary. It does not purport to be exact, and title plans carry a warning to that effect. However, it is possible to apply to HM Land Registry for a determination of the exact boundary. Section 60 reads as follows:

“(1) The boundary of a registered estate as shown for the purposes of the register is a general boundary, unless shown as determined under this section.

(2) A general boundary does not determine the exact line of the boundary.

(3) Rules may make provision enabling or requiring the exact line of the boundary of a registered estate to be determined …”

8. An application to the registrar for a determined boundary must state or show what the applicant regards as the exact boundary. If an objection is made that the registrar does not regard as groundless, then the matter is to be referred to the FTT. The FTT will of course make findings about where the boundary is (Lowe v William Davis Ltd [2018] UKUT 206 (TCC)). It may direct the registrar to reject the application in whole or in part if it finds that the boundary sought is not the correct boundary, or to give effect to the application (in whole or in part) without regard to the objection; the FTT’s direction may include:

“a condition that a specified entry be made on the register of any title affected”

(rule 40(3)(a) of the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Property Chamber) Rules 2013). That means that if the FTT regards the boundary sought as partly correct, it may direct the registrar to give effect to it to that extent, but to reject it insofar as it is incorrect; and it may give a direction about the entry to be made with regard to that part of the boundary where the applicant’s plan was found wanting (Bean v Katz [2016] UKUT 168 (TCC)).

9. A decision about the position of a boundary will always start with the conveyance or transfer that created the boundary; the question is what the parties to that document intended. Any evidence about their behaviour is relevant only insofar as it casts light on their intention at that date. The behaviour of others is irrelevant unless it casts light on the intentions of those original parties. Insofar as that conveyance leaves matters uncertain, the Court of Appeal has held that the court is to put itself in the shoes of the first purchaser, looking at the land with the plan in her hand, and to ask what that purchaser, as a reasonable lay person, would think she had bought (Pennock v Hodgson [2010] EWCA Civ 873). It should be borne in mind that a carefully-drawn conveyance plan showing a straight boundary may not depict a perfectly straight line on the ground; a red line on a plan may be a metre wide on the ground because the conveyancers of the past did not have today’s computerised mapping tools; nor did the builders of the 1960s, with pegs and tape, have the use of today’s measuring instruments.

The properties, the DB plan, and the dispute

10. 82 and 84 Heatherstone Avenue are a pair of semi-detached properties, built in around 1960 by George Wimpey & Co Limited. The transfer of number 82 to the first purchaser shows the boundary as a straight line from front to rear; the transfer of number 84 is not available but it is agreed to have been in identical form. A T-mark on the plan indicates that the rear boundary is the responsibility of number 84. In an aerial view of the properties, with the road at the top of the page (south) and the back garden at the bottom of the page (north), number 82 is on the left, and number 84 on the right to the west.

11. Mr Witt bought number 84 in February 1996. Mr Woodhead bought number 82 in April 1996 with his first wife, Sarah Louise Woodhead; sadly Sarah died in 1997. In April 2013 the house was transferred into the names of Mr Woodhead and Mrs Jennifer Woodhead following their marriage.

12. Mr and Mrs Woodhead’s determined boundary application, made in 2017, was accompanied by a plan (“the DB plan”) which shows the boundary running from the centre of a fence post at the back of the two gardens (point D on the DB plan), which is agreed to be original, through the middle of the party wall and the chimney stack between the two houses, and to the corner of a low wall at the front of number 84’s front garden (point A on the DB plan).

13. Working now from front to back, we can begin with agreement; there is no dispute about the terminus at point A. It is also agreed that the boundary runs through the middle of the party wall between the houses.

14. However, both houses have been extended; each has a brick-built conservatory at the back. There is a mortar joint which Mr Witt says is the junction of the two extensions; he says it is on the boundary, being the point at which he says a line running through the middle of the party wall emerges from the building. The line on the DB plan emerges 4cm to the west (number 84’s side) of that joint (point C on the plan).

15. Moreover, Mr Witt says that the starting point of the boundary is not the centre of the fence post at the back of the gardens, but the number 82 face of the post; he says that since he is obliged to maintain the fence, the posts that supported the original chain link must have stood on his land. That fence is long gone, and there has been a succession of fences between the two gardens, and there is a long-running dispute about the position of the fences.

16. It was the FTT’s task, and it is the Tribunal’s task on this re-hearing, to decide whether and to what extent the DB plan is correct. There is no dispute about it from the front wall to the northern end of the original party wall, but from then on northward, through the extensions and the back gardens, it is not agreed.

17. The DB plan was drawn by Mr Moreton, the expert witness called by Mr and Mrs Woodhead. He explained at the hearing that he started from the 1960 conveyance plan which indicates a straight line boundary, and the Land Registry plan which does the same. He then measured physical and boundary features using a Leica TCR 1205 Total Station and Leica circular prism, steel tapes and surveyor’s staff. He started at the centre of the original fence post at the back, because in his experience the wire passing through the centre of the posts in a fence of that date can be relied on to represent the true intended boundary; and he was able to determine the position of the chimney stack from outside from a number of different observation points, and was therefore able to determine where the centre of the original party wall is. Measurements taken on site are then downloaded into an AutoCAD file to produce a straight line boundary, as shown on the DB plan. The straight line from the centre of the fence post through the middle of the chimney stack ends, coincidentally Mr Moreton says, at the corner of the front wall.

18. There is a second original fence post against the front wall of the houses, and the boundary line passes it on the number 84 side; Mr Moreton explained that the post may have shifted over the years.

19. The line passes 4cm to the west, the number 84 side, of the mortar joint on the back wall of the two houses; if the line is the boundary it gives Mr and Mrs Woodhead ownership of half the width of a brick, measured at the external wall, on the number 84 side of that joint. Since it is agreed that the boundary passes through the middle of the original party wall, it follows that they must own progressively less of the thickness of the brickwork as one passes from the exterior of the extension (a very thin triangle) to its junction with the original party wall.

The mortar joint

20. It is difficult to describe the mortar joint without saying that it is “between” the two properties at the back, and that might seem to beg the question which of course I do not intend. It is a vertical line of mortar on the back wall of the properties, to the west of number 82’s extension windows and to the east of what would have been the extension windows of number 84. Number 84 has had a second extension added later, but it is inset away from the boundary with number 82 and so can be ignored for present purposes. A photograph in the bundle appears to show that the mortar joint lies beneath the western end of number 82’s gutter and beneath the junction of the fascias of the two houses, but no measurements have been produced to show whether they actually line up. The bricks on either side of the mortar joint are slightly different in colour, consistent with their not having been built together.

21. The extensions to both properties were added in the 1970s (long before the parties purchased). The extension to number 84 was brick-built. Mr Witt has produced the plan drawn for the construction of his extension, which shows that it was built out from number 84’s side of the party wall and that that continuation is a cavity wall. I believe that it is not in dispute that it was built as just described, but for the avoidance of doubt I so find.

22. The number 82 extension was a conservatory, described in the estate agent’s particulars (when Mr Woodhead bought) as being made of wood and glass; it is Mr Woodhead’s case that it was made of wood on its north and east sides but had its own brick wall to the west, adjoining number 82 and continuing number 82’s half of the party wall.

23. In 1998 Mr Woodhead got planning permission to replace the conservatory with a brick built extension. The plans for the new extension show a brick wall to be built, adjoining number 82 and continuing number 82’s half of the party wall. If that is what happened, then it follows that the mortar joint is at the point when the two extensions abut each other. It is Mr Witt’s case that that is what happened.

24. Mr Woodhead says that is not what happened. Despite the plan, the western wall produced from his side of the party wall was there already; the conservatory had only two wooden walls (north and east) and its west wall was brick. So only the two wooden sides of the conservatory were replaced with brick. The mortar joint was created when the north (back) wall of his extension was built and joined to the existing brickwork, at the mortar joint, by means of a Furfix. A Furfix is a long metal strip that is fixed to a vertical flat face; it has projections, and the new bricks are fitted between these so that there is no need to damage the existing brickwork to key the new bricks in. I accept that the Furfix was used, because Mr Woodhead was there and saw how it was done, but it may not have been placed where Mr Woodhead says it was.

25. Much confusion has been caused because, if I have understood correctly, Mr Witt initially did not accept that Mr Woodhead’s extension had a western brick wall. He thought that there was only his cavity wall. When asked at the hearing why he thought that he said that Mr Woodhead had told him so when the extension was being built. However, I believe that it is now accepted by everyone that there are three layers of brick between the two houses where the extensions meet. Mr Moreton was able to put the matter beyond doubt by confirming tha the internal face of the west wall of number 82’s conservatory is in line with the internal face of the original wall (this is not obvious on inspection because there is partial wall at right-angles where they join).

26. The question is: what is the mortar joint?

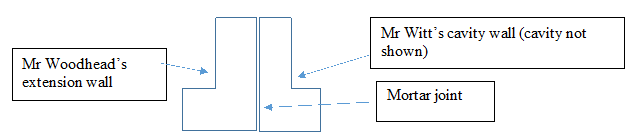

27. Witt says it is at the junction of the two extensions, built in accordance with their plans, like this:

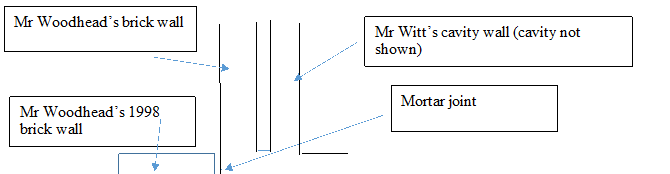

28. Mr Woodhead says that it represents the junction of his own west wall with the back wall of his extension, like this:

29. And that is why Mr and Mrs Woodhead have maintained in discussion with Mr Witt in recent years that the mortar joint is not the boundary because they own their brick wall whose edge lies to the west of it.

30. The expert witnesses were not instructed as building or construction experts, but I asked each of them whether they had a view as to which of these two explanations of the mortar joint is right. Mr Calvert regarded the joint as the junction of the two conservatories. Mr Moreton said that either explanation could be true. Neither was able to add anything to their views that might assist the Tribunal.

31. I find, on the balance of probabilities, that Mr Woodhead’s explanation is wrong. I do not find that he is deliberately not telling the truth, but memories fade over time, and of course he was not in the house when wooden conservatory was built and may have misunderstood what had happened at that stage. He may have misunderstood the purpose of the Furfix in 1998 (which, if Mr Witt is right, must have gone between the two extensions, within the mortar joint). I find that Mr Woodhead is wrong for the following reasons:

a. Mr Woodhead’s explanation means that the west wall of his extension, built with the conservatory in the 1970s, would have come to an end at the outer face of his building, and he has offered no explanation of how that was managed. It may be that the end of the number 82 wall was keyed into the number 84 wall but there is no sign of that.

b. Mr Woodhead was hesitant in giving oral evidence about this. When Mr Williams initially asked him whether the wooden part of the conservatory met the brick on the number 84 extension he said yes, absolutely it did. A couple of pages later in the transcript he corrected himself and said no, sorry, it touched his own brick.

c. Mr Woodhead’s explanation is inconsistent with the plans for his brick-built extension. They are not, of course, conclusive, but it seems more likely than not that they correctly depicted the west wall of the extension as to be constructed (in contrast to Mr Witt’s wall, described as “existing”).

d. I attach very little weight to the photograph that show the mortar joint as lying directly below the end of number 82’s gutters and the junctions of the two houses’ fascias, but it does add a little bit of evidential weight. Of course, as Ms Akther said when I mentioned this at the hearing, the parties are at the mercy of the builders who put in their gutters and fascias; but the most likely explanation for lying above the mortar joint is that that is where the two properties meet.

32. So I conclude that the two extensions were built as their plans indicate and meet at the mortar joint.

33. That does not necessarily mean that the mortar joint is on the boundary. But it makes it very likely. The plans indicate that the two extensions each continued their respective halves of the party wall. Number 84’s was built much earlier, and it is likely that it was built so that its eastern face (which starts at the agreed boundary point in the middle of the party wall, or fractionally offset to Mr Witt’s side) followed the boundary. It is not known what the boundary looked like in the 1970s, but it may still have been marked by the original chain link near the house and so have been relatively easy for the builders to see and follow.

34. On the balance of probabilities the mortar joint, which is where the two extensions meet, is on the boundary. Accordingly the DB plan is wrong, by 4cm, at point C.

The fence post at the bottom of the garden

35. We now have to look at the southern end of the boundary. It is agreed that it starts at the post at the end of the gardens, which is agreed to be original. Mr Witt says it starts on the number 82 face of the post whereas Mr Woodhead says it starts in the middle of the post.

36. Mr Witt relies on the fact that he has the fencing obligation. He has no easement to pass on to number 82 to mend the fence. Therefore the posts must have been entirely on his land so that he could maintain the fence without trespassing, and the chain link was attached on the number 82 side and marked the boundary.

37. There is no rule of law that the position of the boundary is determined by an obligation to fence, whether expressed in words as a covenant (as in this case, although of course positive covenants have no effect beyond the original covenantor) or simply denoted by T marks on the builders’ plans and the first conveyance. There is no presumption that T-marks indicte the ownership of the boundary feature (Lanfear v Chandler [2013] EWCA Civ 1497). There is sometimes said to be a rebuttable presumption that an owner of land will put the posts on his own land so that the fence stands on the boundary (Hawkes v Howe [2002] EWCA Civ 1136); as Ms Akther says, that is of no assistance if the fence was put up by the develop who owned both plots.

38. Mr Moreton expressed the view that the straining wire in the centre of the posts would have been the boundary, but it is difficult to attach any weight to that view in the absence of something to substantiate it.

39. There is very little to assist me here and all I can do is to determine what is the more probable answer. What Mr Witt describes would be a convenient arrangement to facilitate the maintenance of the fence. It is not in dispute than when the original chain link was replaced some years later the new green chain link was on the number 82 side of the original post at the end, and of the replacement posts further into the garden, although Mr and Mrs Woodhead say that they accepted that as a safety measure and not as a boundary marker; but their acceptance of that arrangement may be evidence that that had been the original arrangement.

40. In the balance of probabilities there is very little in the scales on either side; but what there is, namely the maintenance arrangement, outweighs the even more slender evidence for the boundary being in the middle of the posts. I find that the fence was attached to the number 82 side of the posts. The first purchaser, taking possession, walking down the garden with the plan in his hand to check what he had bought, would conclude that that fence, on his side of the posts, marked the boundary which his neighbour was to maintain and, satisfactorily, could do so without trespassing.

41. I find therefore that the northern end of the boundary is on the number 82 face of the original fence post at the bottom of the garden. That means that the DB plan is wrong, again by about 4cm, at point D.

The back garden fences

42. The evidence of conflict over the back garden fences tells the story of the deterioration in these neighbours’ relationship; in the early years of their ownership they were friends, and their children were friends, but things went sour largely, I find, because of the state of disrepair into which the back garden fences were allowed to fall. The photographs in the bundle bear witness to a messy boundary with detritus and vegetation that must have been a source of frustration to Mr and Mrs Woodhead, and which they believed was dangerous for their children. Mrs Woodhead first saw the property in 2002, and her evidence all related to the fencing.

43. It is agreed that the original fence was just the posts and chain link. By the time these parties arrived in 1996 there was a larch lap fence in the southern half of the garden, between the houses and a cherry tree halfway down the garden.

44. Mr Woodhead said that in the 1990s Mr Witt replaced the larch lap fence with a home-made close-boarded fence. He took the view that it encroached on his patio but he chose not to make a fuss about it. In the years that followed the chain link fence became rustier and more unsatisfactory. At some point it was replaced with the chain link that remains today, and the old posts were taken down; Mr Woodhead says that their stumps can still be seen in the ground. The current chain link is fixed to the number 82 side of the posts, as noted above.

45. In around 2011 the cherry tree fell over and damaged the fence. It has been removed, but a self-seeded ash tree stands in its place. The ash tree may be more or less on the boundary; the current fence curves around it.

46. In 2013 a storm destroyed the wooden fence, and Mr Woodhead says that Mr Witt promised to replace it, and spray-painted a line on number 82’s patio where he proposed to put the new fence. Mr Woodhead was not happy with that line.

47. In 2014 when Mr and Mrs Woodhead came back from holiday they found that some panels had been replaced, in line with the mortar joint. They were not happy about that. In 2015 they got quotes to replace the fence themselves, and Mr Witt was very unhappy about that, and put up some more panels which the Woodheads say encroached on their land. They instructed Mr Moreton to produce a plan of the boundary. In 2016 when they returned from holiday Mr Witt had replaced the fence with the one that now stands.

48. Mr Witt’s evidence is that the larch-lap fence had the boarding on the number 82 side of the panels (Mr Woodhead disagrees) and that his close-boarded fence and the later replacement panels lay along the same line. The close-boarded fence had its boards on the number 84 side, for convenience. The present fence is on the number 84 side of the original line, because it was easier to do it that way to avoid the earlier posts.

49. I can derive almost no assistance at all from the evidence about the fencing about the position of the boundary. The passage of time and the movement of vegetation and even of concrete posts means that today’s physical features are of no assistance in deciding the position of the boundary between the gardens. The only point that may be of assistance is that one of the photographs in the bundle appears to show an old post next to the houses whose number 82 side is in line with the mortar joint, which may offer some support for the conclusions I have reached about the mortar joint. If it does, it is of minimal value.

50. The evidence about the fencing assumed much greater importance before the FTT because it was part of Mr Wit’s case that if he was wrong about the original boundary, there was a boundary agreement to the effect that the boundary lay along the current fence. The FTT found no evidence of a boundary agreement, and I agree. But in light of what I have decided it is immaterial.

51. There is nothing before the Tribunal to show, on a scale plan, the exact position of the current fence, let alone of past fences. Even if there were, it is difficult to see how such evidence could assist in the determination of the boundary because of the tendency of fences to bend and break, of posts to shift, and of work to be done on a pragmatic basis to fit around earlier posts and vegetation. The fence as it stands clearly does not follow a straight boundary line because it curves round the ash tree. The evidence about the fencing in the back garden, extensive as it was, is irrelevant to what I have to decide.

The expert evidence

52. I have made findings of fact about the position of the boundary without reference to the expert evidence.

53. Mr and Mrs Woodhead instructed Mr Moreton to draw a plan for them in 2015, and I have referred above to Mr Moreton’s evidence about how he produced it because it became (with some additional annotations) the DB plan. The plan is accompanied by supporting notes, dated 15 May 2015, extending to two pages of text, with a number of photographs. The notes state that the boundary passes through the party wall of the houses and that the extension to number 82 “is correctly positioned within the boundary”. The notes do not say that the boundary passes 4cm to the west of the mortar joint; that derives from the plan itself. The DB plan is said to be accurate to + or - 1cm.

54. Mr Calvert produced a report for Mr Witt in November 2017. His instructions, he says at paragraph 5, were to survey the existing fence, to establish whether it is placed over the original concrete posts and, if not, by how much it deviates. His report focusses on the fences and states at paragraph 31.1 that “the mortar joint is not disputed.” He goes on to say that if the centre of the chimney stack is taken as the middle of the house and a straight line is drawn to the fence post at the back of the gardens, then it passes 14 cm to the number 82 side of the mortar joint.

55. At paragraph 33 Mr Calvert says again that it is common ground between him and Mr Moreton that a mortar joint is a reliable physical indicator of a boundary feature. In his conclusions he states that the boundary is the red line on his plan and that the mortar joint is 11cm on the number 84 side of the line.

56. In cross examination Mr Calvert explained that he started from the number 82 face of the original post. He could not access that face, only the number 84 face, and so constructed his starting point by calculation on the basis of the width of the post.

57. The experts made a joint statement on 20 August 2018, setting out what they agreed and disagreed. In that statement Mr Moreton expressed the view that there is no evidence that the extension of number 82 encroaches into the curtilage of number 84, and Mr Calvert stated that the extension of number 82 is 12cm inside the property of number 84.

58. Ms Akther cross-examined Mr Calvert on his three different figures, given without explanation, for the position of the mortar joint. Mr Calvert explained that his plan was accurate to plus or minus 2.5cm and therefore each time he took the measurement, at different points in his text, it was slightly different. I accept that, but it would have been helpful to have that spelt out in his report. I note that Mr Moreton too has arrived at more than one conclusion about the position of his line relative to the mortar joint; at the FTT hearing his evidence was that his line was 7cm to the number 84 side of the joint, whereas now it is 4cm.

59. Mr Calvert explained that his instructions were not to bother about the front garden, and as a result it is not known at what point his line meets the front boundary. It is a reasonable inference that it must emerge to the number 82 side, by more than 14cm, of the agreed point A at the corner of the wall.

60. On 4 December 2018 Mr Moreton produced an analysis of Mr Calvert’s evidence in order to explain the differences between their results. He suggested that if Mr Calvert had used a Leica Disto then he would have been vulnerable to collimation error, which occurs when measurement devices are not levelled, so that not all measurements are taken on the horizontal plane. Mr Calvert explained in a response dated 11 December 2018 that he had not used a Leica Disto and that there was no collimation error; he noted that he and Mr Moreton may have recorded slightly different positions of the post at point D because he was unable to access the number 82 face of the post.

61. Mr Moreton also produced a plan on which he demonstrated that if a line is produced from the post at the back of the garden and through the back wall of the houses where Mr Calvert says it passes, it runs to the east of the party wall and would mean that number 82 would not own their own living room wall. Mr Calvert says that that is wrong because the line Mr Morton has drawn on that plan does not start from the original fence post. He maintained that his line passes through the centre of the chimney.

62. Mr Calvert noted in his report that the extension to number 82 “does not have its own wall”. That is now agreed not to be true.

63. Mr Calvert produced for the FTT, and on appeal, a plan showing the relationship of the number 84 extension to the original party wall, and depicting no west wall of the number 82 extension. Now that it is agreed that the number 82 extension does have a west wall, the plan is for the most part uncontroversial. It serves as an illustration of how Mr Witt’s extension was constructed, and is consistent with what is shown on the plan drawn for the building of Mr Witt’s extension (paragraph 21 above). The plan notes the position of a nail in the soffit directly above the point where Mr Calvert says the original party wall reached the original north wall of the buildings and on his boundary line; but in the absence of any evidence about that nail I can attach no weight to what Mr Calvert’s plan says about it.

64. Mr Moreton and Mr Calvert are about 4cm apart at the starting point at the end of the gardens, because the original fence post is about 8cm thick. For their lines to have deviated so much (somewhere between 13 and 18 cm) at the back wall of the houses, one might suppose that they had reached different conclusions about the position of the centre of the chimney, since each was dependent upon that feature for the identification of the middle of the party wall. It is certainly obvious as a matter of basic geometry that if Mr Calvert’s and Mr Moreton’s lines both run straight from the post at the back of the garden through the centre of the chimney, they cannot meet at the agreed boundary point in the front garden. Mr Calvert’s line does not extend that far so the point is not apparent from his plan.

65. What the experts have in common is their use of, and expertise in analysing, a computer-generated line produced using tools that the builders of 1960 could not even have imagined. One can guess that the builders used pegs and a tape. It is not known whether the corner of the front wall as it now stands was the point they started from. It is not known whether the post at point D on the DB plan was placed precisely on the point they used at that end, if indeed they measured in that way. One can guess that the party wall they built will have been pretty much, but perhaps not precisely, on the straight line that that tape might have produced, if they used one. What they did do was to produce a party wall whose middle is the boundary, and to put up a chain link fence that was - as I have found - the boundary.

66. Neither expert has produced a line that replicates that boundary. Mr Moreton’s line gives Mr and Mrs Woodhead ownership of only half the thickness, at most, of their extension brick wall. Mr Calvert has produced a line that gives Mr Witt ownership of the brick wall of the Woodheads’ extension. There are two reasons for that; first, their methods do not purport to be accurate to a hair’s breadth; and second that they cannot replicate the builders’ methods. Both experts were impressive, both did what they had been instructed to do, but ultimately neither has produced evidence that outweighs what can be derived from the land itself, the building, the construction of the extensions, and some reasoning (such as it is) about the fence post.

Conclusion

67. In conclusion, the appeal succeeds. The boundary runs from the agreed point A at the front, through the middle of the original party wall, through the mortar joint, and to the eastern face of the fence post at the northern end of the gardens. That means that the DB plan is incorrect from the northern end of the original party wall, through the extensions, to the post at the end of the garden.

68. I see no purpose in directing the registrar to accept that part of the DB plan that is correct, since insofar as it is correct it is uncontroversial. Accordingly I direct the registrar to reject the application for a determined boundary.

69. That leaves the parties without a determined boundary. However, all my findings about the position of the boundary were made in order to decide what direction should be given to the registrar. They therefore create an issue estoppel between the parties, which means that they cannot be questioned in any future proceedings between the parties in which the position of the boundary is in question. The parties will of course have to sort out the fence in the back garden, and will be able to do so in the light of my findings.

70. That brings the reference to an end save for any question about costs; the Tribunal’s letter about costs procedure is sent to the parties with this decision.

|

|

|

Judge Elizabeth Cooke 18 November 2020

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|