Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Hopkins & Anor v Ure & Anor (RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - MODIFICATION - garden land - planning permission for new house - whether restrictions obsolete) [2020] UKUT 315 (LC) (23 November 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2020/315.html

Cite as: [2020] UKUT 315 (LC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2020] UKUT 315 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LP/15/2019

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 84 OF THE LAW OF PROPERTY ACT 1925

RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS - MODIFICATION - garden land - planning permission for new house - whether restrictions obsolete - practical benefits of substantial value or advantage - effect of proposed house upon privacy, overshadowing and massing - application refused - Law of Property Act 1925 section 84(1) (a) and (aa)

|

BETWEEN: |

(1) DENYER JILL GRENDON HOPKINS (2) MICHAEL HOPKINS

|

Applicants |

|

|

and |

|

|

|

(1) JEREMY URE (2) CATHERINE URE |

Objectors |

|

|

|

|

Re: Skelfleet,

Belmont,

Ulverston,

Cumbria

LA12 7HD

Peter D McCrea FRICS FCIArb

13 October 2020

Carlisle Magistrates Court, The Court House, Rickergate, Carlisle, CA3 8QH

Richard Moore, instructed by Progression Solicitors, for the applicants

Matthew Hall, instructed by FDR Law, for the objectors

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2020

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Adams & Anor v Sherwood & Ors [2018] UKUT 411 (LC)

Shephard v Turner [2006] EWCA Civ 8

Introduction

1. On a hill overlooking the South Lakeland market town of Ulverston, the Hoad Monument commemorates the life of Sir John Barrow, a founding member of the Royal Geographical Society. The monument is visible from a variety of locations in the town, not least from a nearby cul-de-sac known as Belmont which is in an elevated location to the north east of the town centre.

2. This short decision concerns an application for the discharge or modification of restrictive covenants attached to the separate garden of a house on Belmont known as Skelfleet. The applicants, Mrs Denyer Hopkins and Mr Michael Hopkins, have planning permission to erect a new house in this separate garden, but are prevented from doing so by covenants attached to the title. Of the various beneficiaries of the restrictions, the only objectors to the application are Mr Jeremy and Dr Catherine Ure, who own 2 Belmont. As I explain below, while 2 Belmont is the next but one house from Skelfleet, its separate garden adjoins the application land.

3. I carried out a site inspection on 12 October 2020 accompanied by representatives of the parties and was able to inspect the application land. I also saw the view of the application land from inside 2 Belmont, from its the front garden and from its separate garden directly adjoining the application land. I heard the application at Carlisle Magistrates Court the following day. The applicants were represented by Mr Richard Moore of counsel who called Mrs Hopkins, her architect Mr Robert Glass as a witness of fact, and Mr Matthew Parkinson MRICS who gave expert valuation evidence. The objectors were represented by Mr Matthew Hall of counsel who called Mr Ure, and Mr James Fish MRICS to give expert valuation evidence. I am grateful to all of them for their assistance.

The local geography

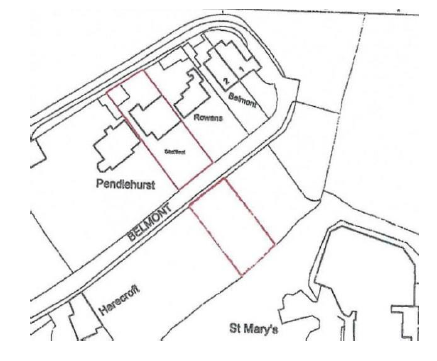

4. The four other houses in the immediate vicinity of Skelfleet are all elevated from the north-west side of Belmont and have far-ranging views over the town and towards the south Lakeland coastline. They are 1 and 2 Belmont, Rowans, and Pendlehurst, as shown on this plan, on which Skelfleet and its separate garden immediately opposite - which forms the application land - are both edged red.

Diagram, engineering drawing Description automatically generated

5. With the exception of Rowans (the freehold of which does not extend across the road) the plots are by bisected by Belmont, so that the freehold interest in each case comprises the main plot upon which the house sits, elevated on the north western side of the road, and at a lower level a further garden plot sloping down away from Belmont on its south eastern side. As I explained above, the garden immediately adjoining that of Skelfleet to the north east is owned by Mr and Dr Ure in connection with 2 Belmont.

6. At the top of Belmont, in addition to providing access to a couple of other properties, an unadopted road continues around the side of 1 Belmont to the rear of the houses listed above. 1 Belmont has a parking space across the road and a single attached garage. 2 Belmont has a parking space across the road and a space for two small cars at the rear. Rowans does not have any car parking spaces at the front and has a very shallow garage at the rear. Pendlehurst has a large garage to the rear and is on a large plot.

7. To the rear of Skelfleet there is one parking space and a single garage, with the possibility to create two or three further spaces but this would entail the demolition of a wall and the removal of an attractive greenhouse. To the front, on the opposite side of Belmont, there is a substantial parking apron with retaining walls providing parking space for two to three cars. The application land largely comprises the garden which slopes away from this parking area.

8. Currently, parking is not a real issue because some of the houses are unoccupied. Even so, when the bin lorry or recycling lorry make their collections, the driver must reverse up Belmont because there is insufficient room to turn around. Additionally, some visitors to the Hoad Monument come up Belmont by mistake and often turn around on the concrete parking apron of Skelfleet.

The restrictions

9. The plots were sold off by a common vendor, Mr Theophilus Jefferson, between 1871 and 1874. Each transfer included restrictive covenants in favour of Mr Jefferson and his successors in title. As regards the application land, the proposed development is prevented by restriction on the title imposed by conveyance dated 7 May 1874 between Mr Jefferson and Mr Richard Bailey. Of the restrictions binding Mr Bailey and his successors in title, those which are said to be the subject of this application are as follows:

“… and that he the said Richard Bailey his heirs or assigns shall not nor will at any time hereafter erect and build upon any one Lot of the said land hereby assured more than one dwelling house and that every such dwelling house shall be placed with the front thereof up to several building lines shown upon the said plan so that no building shall project further forwards than the building adjoining …”

10. The building line was broadly along the line of the front elevation of 1 and 2 Belmont. It was altered by a further deed dated 1 July 1904 which had the effect of staggering the building line so that each house to the south west of its neighbour was required to be situated slightly further back from Belmont. There is no dispute that the proposed development would breach the “one house” restriction, since Skelfleet is already built, and would be in front of the staggered building line.

The proposed development

11. On 9 January 2019, South Lakeland District Council granted planning permission for the erection of a single dwelling on the separate garden of Skelfleet. The proposed house was described with varying degrees of enthusiasm by the witnesses but on any view it would be of strikingly contemporary design, over two floors built into the slope so that the rear of the first floor would be broadly level with Belmont, whilst the ground floor below would be located further down the slope but still elevated from the garden itself owing to the sloping nature of the site. The elevations would be of zinc with larch or cedar and natural stone facing. The monopitch roofs would feature solar panels and a sedum roof. Both storeys would have balconies with glass balustrading overlooking the garden. There would be two car-parking spaces where the existing concrete apron is located and a single garage sufficient to accommodate a small or medium vehicle. Much of the existing garden plot would be given over to the house leaving a small area at the bottom of the garden which would be retained.

The application

12. The application is for both discharge and modification of the restrictions, relying on grounds (a) and (aa) of section 84(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

13. Ground (a) applies where the Tribunal is satisfied, that by reason of changes in the character of the property or the neighbourhood or other circumstances of the case which the Upper Tribunal may deem material, the restriction ought to be deemed obsolete.

14. So far as is material, ground (aa) requires that, in the circumstances described in subsection (1A), the continued existence of the restriction must impede some reasonable use of the land for public or private purposes. The circumstances in subsection (1A) which must be demonstrated are as follows:

“Subsection (1)(aa) above authorises the discharge or modification of a restriction by reference to its impeding some reasonable user of land in any case in which the Upper Tribunal is satisfied that the restriction, in impeding that user, either —

(a) does not secure to persons entitled to the benefit of it any practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to them; or

(b) is contrary to the public interest, and that money will be an adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which any such person will suffer from the discharge or modification.”

15. The Tribunal is required, when considering whether sub-section (1A) is satisfied and a restriction ought to be discharged or modified, to take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permission in the area as well as the period at which and context in which the restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances (section 84(1B)).

Evidence

16. Mrs Hopkins gave evidence on behalf of herself and her husband, explaining that the reason for the application was owing to Mr Hopkins’ illness which caused him loss of balance and the occasional fall. Having unsuccessfully put Skelfleet on the market, Mr and Mrs Hopkins decided instead to build a house on the garden plot across the road which would be designed to be more suitable for Mr Hopkins, including a lift. Their intention was that Mr Hopkins’ son would move into the existing house and be on hand to help if Mr Hopkins needed assistance.

17. She explained that the proposed new building was designed to have a minimal impact on the existing neighbourhood, partly in anticipation of planning objections but also to reduce the impact on their family who would continue to live in Skelfleet. For example, the solar panels on the roof of the property were redesigned to reduce their prominence and a flat sedum roof featured in the design to blend in with the surrounding environment. In terms of parking and traffic Mrs Hopkins said that the new development would cause no reduction in the number of available parking spaces - there would continue to be two on the apron and two at the rear of Skelfleet where her son-in-law’s intention was to create a further three new off-road parking spaces.

18. In cross-examination, Mrs Hopkins accepted that someone visiting without an arrangement or delivery drivers would need to park on the road. She also accepted that for the new house to be constructed, the existing foliage and trees between the proposed house and the objectors’ garden would need to be removed and, importantly, that there was not a great deal of room for new trees to be planted. Instead she suggested that the objectors could plant trees on their land to screen the new building. However she accepted that the objectors would still have a sense of being overlooked, if people were standing on the balconies looking across the objectors land, with the caveat that she and Mr Hopkins had no intention of doing that because the better view that would draw the eye was across the valley.

19. The Hopkins’ architect, Mr Robert Glass confirmed that his instructions were to design the house with a low roof pitch and to have minimal visual impact. A later amendment, at the request of the planning officer, was to alter the roof so that the solar panels were not visible when viewed from the Hoad Monument.

20. As regards the boundary to the objectors’ land, Mr Glass thought that there might be room for some replacement trees, but accepted that the plan he had prepared did not show the precise position of the boundary between the two sites. His evidence was that the existing hedge would not necessarily need to be removed to construct the new house. He accepted in cross examination that if standing in the objectors’ garden, the new development would amount to an imposing mass of building, and in practical terms no fence could built high enough to screen it.

21. Giving evidence on behalf of himself and his wife, Mr Ure said that they bought 2 Belmont in 2017, having spent six months searching for a South Lakes property in a quiet area with countryside views. He exhibited the sales particulars at the time which described the property as having “super panoramic views”. During the conveyancing process he and Dr Ure were informed that there was a restrictive covenant preventing additional buildings being constructed in front of the existing houses which helped to reassure them that not only did the property have a fantastic view but that over the years to come there would be minimal traffic and noise.

22. Mr Ure had concerns that although the existing application was for one dwelling, the removal of the restrictive covenant would ultimately open the floodgates to further applications and development. The loss of the view and increased noise would transform the very nature of the area and the property. There would also be an increase in traffic in the area. Mr Ure’s evidence was that should the application succeed he and Dr Ure would not be able to enjoy their lower garden as they do now, benefiting as it does from greenery on either side creating an open area and light feeling. The proposed development would change the dynamic of the garden making it feel more enclosed and overlooked. They would lose the peace and quiet of the current garden with a house directly neighbouring it and he was also concerned that they would lose sunlight in the summer evenings.

23. Even in the short term the works themselves would cause considerable disturbance. Whilst he and Dr Ure had been advised that any compensation would be based on the reduction in the value of his property, money would not be an adequate remedy to them as they feared it would be impossible to find another property that has the combination of views and a quiet road.

24. Turning now to the expert valuation evidence, helpfully it was common ground that the market value of 2 Belmont, without any discharge or modification of the covenant on Skelfleet, was £435,000.

25. For the applicants, Mr Parkinson’s opinion was that the effect on the value of 2 Belmont of the restrictions being discharged or modified to permit the proposed development would be a reduction of £5,000. His evidence was that there would be little overall effect on 2 Belmont from the proposed property because on either basis the effect on the general view to the distance was still minimal. In his experience modern houses in more traditional areas were becoming more prevalent and open plan accommodation was becoming more popular. He rejected the notion that the likely purchaser of a house such as 2 Belmont would be either put off or likely to lower their bid by the presence of the proposed new house. He accepted that there might be some light pollution from the new house but thought this was countered by the presence of a streetlight on Belmont itself.

26. Mr Parkinson confirmed that he did not gain access to 2 Belmont or its separate garden during his inspection. Instead he took photographs from 1 Belmont and considered the impact on the garden of no.2 from the application land and the public highway.

27. For the objectors, Mr Fish’s opinion of the effect on the value of no.2 Belmont as a result of the proposed dwelling being constructed would be a reduction in market value of just over 10%, to £390,000. Unlike Mr Parkinson, Mr Fish had viewed the application land both from inside 2 Belmont and from its separate garden. Mr Fish’s evidence was that the views from 2 Belmont were those of a garden area restricted to shrubs or trees and very much a naturalistic setting along the road. He described the proposed house as having a considerably angled roof and of varying construction materials which would cause a visual intrusion and impact on the desirability of views from the property.

28. In Mr Fish’s opinion, the proposed dwelling would cast a shadow within the lower garden space of the objector’s property. While natural light can pass through the current screen of foliage between the two plots, it would not pass through a solid structure. There would be a balcony on each storey, overlooking the garden plot of 2 Belmont. These factors would have a considerable impact on the enjoyment of the garden space, and an effect on the amenity value and desirability of the garden, particularly during the summer months.

Are the restrictions obsolete?

29. Mr Moore submitted that the restrictions ought to be considered obsolete because of the changing character of the area - comparing historic photographs with current photographic evidence, he submitted that when the restrictions were imposed the area in question looked out over open fields, whereas now the outlook has changed considerably. But he accepted that the purpose of the restrictions can still be achieved.

30. Referring to the decision of the Tribunal (Martin Rodger QC, Deputy President and Mr A J Trott FRICS) in Adams & Anor v Sherwood & Ors [2018] UKUT 411 (LC), Mr Hall submitted that an application under ground (a) requires four matters to be considered. It is first necessary to identify the purpose or object of the restrictions; and the applicants had accepted in their statement of case that the aim of the restrictions was to preserve views and prevent building on the lower plots. Next it is necessary to ask whether the character of the property or neighbourhood has changed since the restrictions were imposed; Mr Hall submitted that neither the applicants’ nor the objectors’ properties, nor the neighbourhood have changed in any material way since the restrictions were imposed or when the 1904 building line was established. The third question is whether the restrictions become obsolete by reason of those changes, in the sense that the object of the restrictions can no longer be achieved; and as indicated above Mr Moore had conceded that the object could still be achieved. Finally, it is necessary to consider whether there is some material circumstance other than a change in the character of the property or the neighbourhood that would cause the restrictions to be considered obsolete; and Mr Hall submitted that no other circumstance could be identified.

31. I accept Mr Hall’s submissions on ground (a). In fairness, Mr Moore did not pursue the ground with any vigour and made the obvious and sensible concession that the purpose of the restriction could still be achieved. The purpose of the restrictions, to preserve views from the properties at Belmont and to prevent building on the lower plots, can in my judgment still be achieved. While there has been development in the area since the restrictions were imposed, and the building line altered, the thrust of the restrictions is in my view still very much alive in the early 21st century. I can find no circumstances that would lead me to conclude that the restrictions are obsolete, and I therefore dismiss the application under ground (a).

Ground (aa) and practical benefit of substantial value or advantage

Is the proposed development “some reasonable user” of the land, and do the restrictions impede that user?

32. It was common ground that the proposed house would be a reasonable user of the land for the purpose of the Act, and that the restrictions impeded that use.

Does impeding the user secure practical benefits to the objectors?

33. Mr Moore accepted that in principle the preservation of a view, the reduction of noise and the prevention of an increase in vehicular traffic may all be of a practical benefit. However, he submitted that the practical benefits concerned must be connected to the restriction, even if collaterally. Relying on Shephard v Turner [2006] EWCA Civ 8, Mr Moore submitted that if the benefit relied upon could be diminished by a user which did not breach the restriction and was practically possible, then the covenant did not in fact secure a practical benefits.

34. Mr Moore submitted that the overall purpose of the restrictions was to ensure that only a limited number of large houses were built along Belmont, which were initially intended to have a uniform frontage. That restriction was done away with in 1904, which allowed for staggered building lines. He submitted that this is a minimalist covenant. Beyond building lines there was no attempt to control design nor of the size, beyond a minimum, or number of occupants of what was built.

35. The impact on 2 Belmont of the proposed development would, he submitted, be minimal. Many of the concerns of the objectors did not relate to the restrictions: a lawful use might result in an increase in noise, or an increase in traffic or congestion. As for Mr Ure’s concerns about noise and traffic from construction, it is the long term user that must be considered, not the short term and transient development works. Mr Moore submitted that the restrictions did not require the submission or approval of plans; the objectors’ concerns about the aesthetics of the proposed house are therefore not relevant.

36. As for the separate garden belonging to 2 Belmont, while Mr Parkinson and Mr Glass accepted that the development might cause a reduction in natural light at certain times, there was nothing preventing trees and plants growing to a similar or greater height than the proposed house.

37. In my view Shephard v Turner does not assist Mr Moore. He relied on the comments of Carnwath LJ (as he then was) at paras 37-41 but what Lord Carnwath explained was that if an equally damaging development could be carried out without breaching the relevant restrictions, and there is evidence that that is likely to happen then the apparent benefits of impeding the proposed development may be illusory. In this case, I am not satisfied there is a likely development which could be equally damaging that could take place without breaching the restrictions. It is possible that a house might be built if Skelfleet were demolished, but that would only satisfy the “one house” restriction, but still be in breach of the building line.

38. It is plain, in my view, that the restrictions secure to the objectors a practical benefit, in that they prevent the development of any house on the application land.

Substantiality

39. Since Mr Parkinson was unable to inspect the application site from the objector’s property, I place less weight on his evidence in that regard than that of Mr Fish. However, it is not necessary for me to consider whether Mr Fish’s opinion of the diminution in value of the objector’s property at just over 10% of its unaffected value represents a substantial reduction for the purposes of the Act. That is because the real issue in this application is whether impeding the proposed development secures to the objectors a substantial advantage. In my judgment it does.

40. It is necessary to consider the effect of the proposed development on all the land that benefits from the restriction. Having viewed the application site from the inside of 2 Belmont, in my judgment the presence of the proposed development when viewed from inside the house would be an irritation but that would not be material to the outcome of this application.

41. It is from the lower adjoining garden of 2 Belmont that there would be a significant detrimental effect the objectors’ property. What is now a secluded and green space would in my judgment be severely impacted by the presence of a house, of whatever design, immediately adjoining it. Both Mrs Hopkins and Mr Glass accepted that there could be overlooking from the new house. While Mrs Hopkins said that her family would not overlook the Ures’ garden, it is the long term and permanent effect that must be considered - once modified, the restrictions cannot be reimposed. There would also be an overbearing massing of a building which could not, in my view, be mitigated by tree planting. It is the combination of a substantial block of solid property adjoining the objector’s garden and the increased likelihood of all the activity that a house would bring that is the real issue in this case.

42. Having stood in the garden myself, I have no doubt that the ability to prevent the erection of a house in the land immediately adjoining secures to Mr and Dr Ure a practical benefit of substantial advantage. On that basis, the application under the ground (aa) also fails.

Conclusion

43. For the reasons given above the application is dismissed.

44. This decision is final on all matters other than the costs of the application. The parties’ attention is drawn to paragraph 15.11 of the Tribunal’s Practice Directions dated 19 October 2020 [1]. If costs cannot be agreed, the parties may make submissions on such costs and a letter giving directions for the exchange and service of submissions accompanies this decision.

P D McCrea FRICS FCIArb

23 November 2020