Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Russell Transport For London ((COMPENSATION - Land Compensation - dwelling house - depreciation in value as a result of physical factors) (Rev 1) [2020] UKUT 281 (LC)(17 November 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2020/281.html

Cite as: [2020] UKUT 281 (LC)(17 November 2020)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

UT Neutral citation number: [2020] UKUT 281 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LCA/291/2019

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

COMPENSATION - Land Compensation Act 1973 Part I - dwelling house - depreciation in value as a result of physical factors caused by use of highway improvements to remove the Archway Gyratory system

IN THE MATTER OF A NOTICE OF REFERENCE

|

BETWEEN: |

MARGARET RUSSELL |

|

|

|

|

Claimant |

|

|

and |

|

|

|

TRANSPORT FOR LONDON |

Respondent |

|

|

|

|

Re: 32 St Johns Way,

Archway,

London, N19 3RR

Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

8 to 10 September 2020

By Skype for Business

Mr Stan Gallagher for the appellant, instructed by direct access

Mrs Harriet Townsend for the respondent, instructed by TfL

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2020

No cases are referred to in this decision:

Introduction

1. This case concerns a claim for compensation under Part I of the Land Compensation Act 1973 (“the Act”) by Ms Margaret Russell (“the claimant”), the owner of 32 St John’s Way, Archway, London N19 3RR (“the property”).

2. The claim arose from a highway improvement scheme undertaken in 2016 by Transport for London (“the respondent”) to remove the Archway Gyratory system on the A1 in north London (“the works”). The works involved closure of one link of the gyratory, to create a public space, and the creation of two way traffic lanes elsewhere to replace the previous one way system. The works included improved provision for cyclists and wider pavements for pedestrians.

3. The property is located on St John’s Way, close to its junction with Archway Road where significant changes were made to road layout and traffic flow.

4. The agreed completion date for the works (the “relevant date” under section 1(9) of the Act) was 10 June 2017 and thus the “first claim day” (under section 3(2) of the Act) was 10 June 2018. This is the valuation date for the claim.

5. The claimant had purchased the property in August 2009 and it was not in dispute that she held a qualifying interest under section 2 of the Act. It was also not in dispute that she had made a valid claim for compensation under sections 3 and 9 of the Act.

6. Mr Stan Gallagher appeared for the claimant, instructed directly by the claimant. The claimant provided a witness statement and gave oral evidence. The claimant’s witness statement referred to a Noise Impact Assessment prepared jointly for her and for the owners of 20 St John’s Way by Mr Duncan Arkley of KP Acoustics. Mr Gallagher called expert valuation evidence from Mr Alan Cohen BSc FRICS, a Director of Talbots Surveying Services Limited.

7. Mrs Harriet Townsend appeared for the respondent, instructed by their in-house legal team. She relied on two witness statements which were not challenged by the claimant. Mr Jamie Forrester, a Senior Surveyor in the Estates Management Directorate of the respondent, provided annotated plans detailing the changes to the road layout arising from the works. Expert evidence on the noise impacts of the works was provided in writing by Mr Matthew Muirhead of AECOM, a multi-disciplinary engineering consultancy. Mrs Townsend called Mr Richard Alford BSc MRICS, a Director of Copping Joyce Surveyors Limited to give expert valuation evidence.

8. On the morning of 8 September 2020, accompanied by the claimant and Mr Morgan Francis of the respondent’s in-house legal team, I carried out an internal inspection of the property. I am grateful to the claimant, and her son, for allowing us to enter all the rooms of the property and for explaining the measures they have taken to deal with factors that they find intrusive. I am grateful to Mr Francis for explaining, by reference to plans of the road layout before and after the works, the detail of the changes made to the Archway Gyratory. I subsequently walked, unaccompanied, to the locations of nine comparable properties listed in the expert reports. I returned at 8.30 pm the same day to the road outside the property to view the traffic lights and pedestrian crossing lights after nightfall.

Factual background

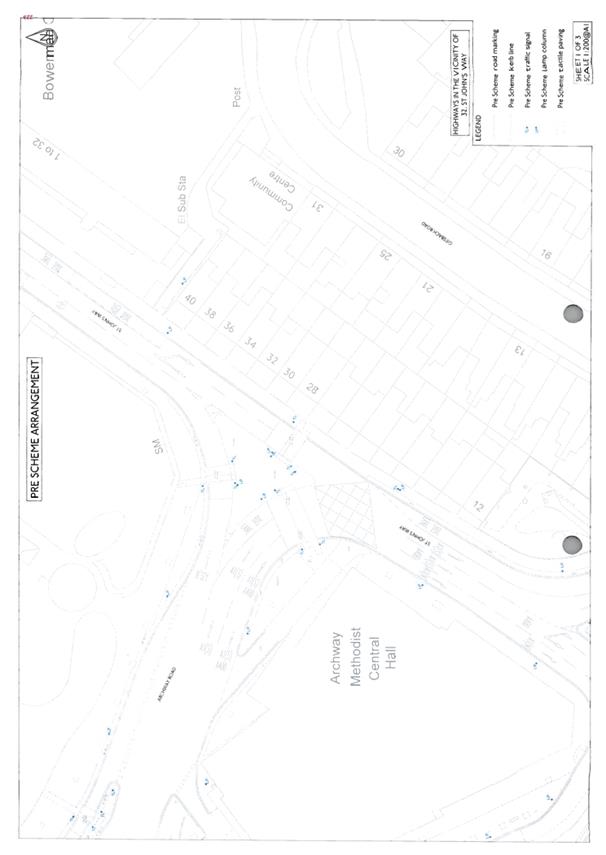

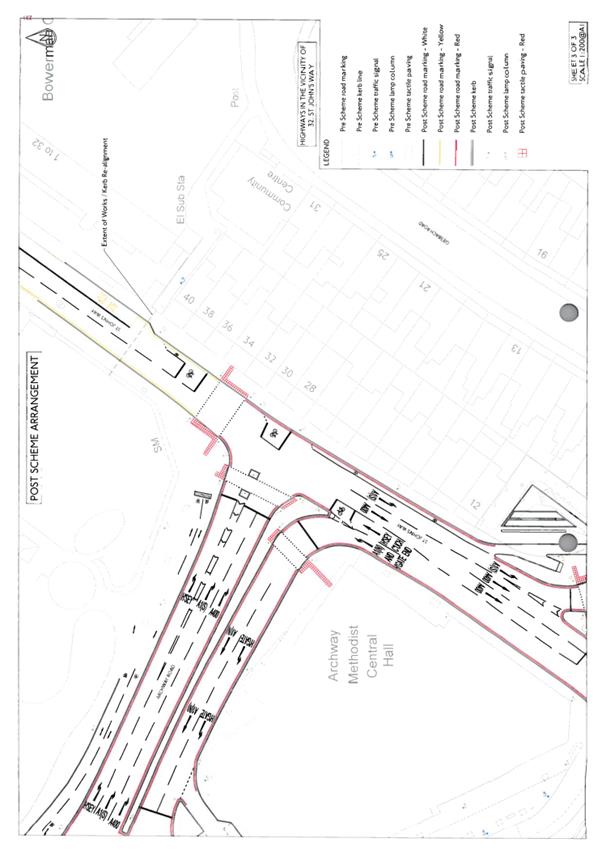

9. The parties provided initial and supplementary statements of agreed facts, which were most helpful in narrowing the issues in dispute. From those statements, the annotated plans of the scheme, the evidence of the claimant and my own inspection, I find the following facts.

10. The property is a substantial mid-terrace three storey Victorian house which sits within a parade of 15 similar houses (numbered 12 to 40 running northwards) on the south east side of St John’s Way, close to the junction with Archway Road, in the N19 postal district of the London Borough of Islington. It is of traditional solid brick construction with suspended timber floors and a pitched slate tiled roof. The windows are mainly double hung sash units, with secondary glazing to the bay windows on the road side at lower and upper ground floor levels.

11. The lower ground floor provides a bedroom, living room, kitchen and bathroom. This floor is occupied separately, by a member of the claimant’s family, but is connected to the rest of the house internally and externally. The upper ground floor provides a living room, kitchen/dining room and bathroom, and there are two bedrooms on the top floor. The gross internal area is 1,434 sq ft (133.1 sq m). When purchased in 2009 the property was described as having four bedrooms, and no living room on the lower ground floor. There is a rear garden at lower ground floor level and a small roof terrace at upper ground floor level. To the front there is a small garden area at lower ground floor level. There is no available parking, on or off street.

12. No planning consent exists for the property to be used as two flats, but it is not unusual for properties in the immediate area to be converted into flats and it is not expected that consent would be difficult to obtain. Conversion would require expenditure to create a separate access and to provide separate utility supplies. An independent heating system is already installed.

13. At the junction opposite the property, the A1 on Archway Road turns south onto St John’s Way. Before the works, two lanes of traffic flowed southwards past the property, continuing into the part of St John’s Way which is the A1. A single lane of traffic approached on the A1 from Archway Road, joining St John’s Way opposite No 36 to run northwards. A triangular island within the junction separated the north turning traffic, so that the centre of that lane was 19.6 m from the front of the property. After the works the traffic flow outside the property was reduced to a single lane in each direction, with the centre line of north turning traffic now 14.7 m from the front of the property. Plans showing the pre and post scheme layout are provided at Appendix 1 for clarity.

14. Immediately to the front of the property is a pavement which, before the works, was bounded on the road side by railings and had a kerb 6.9m from the front of the house. As part of the works, the railings were removed and the pavement was widened so that the kerb is now 9.1m from the front of the house.

15. The newly positioned traffic stop line, for traffic flowing south past the property, is outside No 38, 22.2 m further back from where it was previously outside No 28 and No 30. Facing the road from the door of the property the stop line is now three doors to the right, rather than two to the left and whereas previously traffic waiting in line at the lights would have queued outside the property, now traffic only passes the property when proceeding through on a green light.

16. The light controlled crossing has been moved from beyond the previous traffic stop line, outside No 26 and No 28, to a position in front of the property and No 34. It has been widened to allow both cyclists and pedestrians to cross, as part of the new system of cycle lanes. The lights visible from the property are a high level assembly of four lights on the far side of the road providing a red/amber pedestrian light above a row of three lights for a green cyclist, a green pedestrian and a number countdown. When observed by me, with Mr Francis, the crossing lights only operated when initiated by someone pressing the ‘wait’ button, so it is the red pedestrian light which is visible for the majority of the time, whether traffic is flowing or at a standstill. There is no ‘bleeping’ noise associated with this crossing.

Statutory provisions for entitlement to and assessment of compensation

17. Section 1 of the Act sets out the right to compensation as follows:

“1. -Right to compensation.

(1) Where the value of an interest in land is depreciated by physical factors caused by the use of public works, then, if -

(a) the interest qualifies for compensation under this Part of this Act; and

(b) the person entitled to the interest makes a claim after the time provided by and otherwise in accordance with this Part of this Act,

compensation for that depreciation shall, subject to the provisions of this Part of this Act, be payable by the responsible authority to the person making the claim (hereinafter referred to as “the claimant”).

(2) The physical factors mentioned in subsection (1) above are noise, vibration, smell, fumes, smoke and artificial lighting and the discharge on to the land in respect of which the claim is made of any solid or liquid substance.

(3) The public works mentioned in subsection (1) above are -

(a) any highway;

…

(4) The responsible authority mentioned in subsection (1) above is, in relation to a highway, the appropriate highway authority…

(5) …the source of the physical factors must be situated on or in the public works the use of which is alleged to be their cause.

…

(9) Subject to section 9 below, “the relevant date” in this part of the Act means -

(a) in relation to a claim in respect of a highway, the date on which it was first open to public traffic.”

18. Section 2 deals with the types of interest which qualify for compensation. It is not in dispute that the claimant had a qualifying interest at the relevant date. Sections 3, 4 and 16 deal with claims, the assessment of compensation, and referrals to the Tribunal, as follows:

“3. - Claims

(2) Subject to the provisions of this section and of sections 12 and 14 below, no claim shall be made before the expiration of twelve months from the relevant date; and the day next following the expiration of the said twelve months is in this Part of this Act referred to as “the first claim day”.

4. - Assessment of compensation: general provisions.

(1) The compensation payable on any claim shall be assessed by reference to prices current on the first claim day.

(2) In assessing depreciation due to the physical factors caused by the use of any public works, account shall be taken of the use of those works as it exists on the first claim day and of any intensification that may then be reasonably expected of the use of those works in the state in which they are on that date.

…

(4) The value of the interest in respect of which the claim is made shall be assessed—

…

(b) subject to section 5 below, in accordance with rules (2) to (4) of the rules set out in section 5 of the Land Compensation Act 1961;

16. - Disputes

(1) Any question of disputed compensation under this Part of this Act shall be referred to and determined by the Upper Tribunal.

…”

19. Of the rules referred to in section 4(4)(b) it is only rule (2) in section 5 of the Land Compensation Act 1961 which is relevant in this case:

(2) “The value of land shall … be taken to be the amount which the land if sold in the open market by a willing seller might be expected to realise…”

The issues

20. The dispute between the parties concerns the amount of compensation payable under the Act for the depreciation caused to the property by physical factors arising from the use of the works, and any anticipated intensification in use, as at the first claim day, 10 June 2018. Determination of the compensation requires a two stage process. First the physical factors arising from use of the works must be established, and then the impact on value of those factors is considered. Unlike the case where a new road is built, and the physical factors arising from it are new and easily identifiable, a claim for a road improvement scheme requires it to be established whether physical factors arising from the use of the improvement scheme have had a greater depreciating effect on value than those experienced with the original layout. Without evidence of an increase, or at least a change, in physical factors, there can be no claim for compensation.

21. Evidence was supplied on the change in traffic flows arising from the works, and on the extent of changes to noise and air quality levels. Mrs Townsend for the respondent submitted that the property’s location was already affected by noise and pollution, and that any small increases in these factors arising from the use of the works would be insufficient to have an additional impact on the value of the property in the open market. She conceded that the new pedestrian crossing had introduced artificial lighting sufficient to have a small adverse impact on the value of the property and the respondent’s valuation expert assessed the extent of that depreciation at £20,000.

22. By contrast, the claimant maintained that the additional levels of noise, pollution and artificial lighting were very significant to her enjoyment of the property and her valuation expert assessed the depreciation caused by the increase to be £200,000.

Evidence on physical factors

Traffic flow

23. Whilst traffic flow is not a physical factor in itself, it is the cause of noise and data on traffic flow is used to inform noise assessment calculations. A technical note, prepared in September 2019 by AECOM, Mr Muirhead’s firm, and appended to Mr Alford’s expert report, reviewed the data on traffic flows at the junction pre-construction and post-construction which had been supplied to the respondent by AECOM for noise assessment of the Archway project.

24. The resulting data on net changes to the flow and numbers of all vehicles between 2017 pre-construction and 2018 post-construction was not disputed. Mr Gallagher, for the claimant, submitted calculations made using that data which revealed an overall increase of 31.5% in vehicle numbers using the junction, albeit the numbers passing directly in front of the property had decreased. I calculate the decrease to be 12.4%.

Noise

25. Both parties referred to a document entitled Archway Gyratory: Noise and Air Quality Impact Assessment (“the 2016 impact assessment”) prepared for the respondent in February 2016. The author of the document was redacted in the bundle. Each party had instructed an acoustic expert, whose evidence was provided in a written report. There was little difference between the opinions of the two experts so they were not called for cross-examination. I am grateful to them for their helpful reports. Noise levels were measured on the logarithmic decibel scale, ‘A’ weighted to model the human ear, showing the noise level exceeded for 10% of an 18 hour period. The standard shorthand of “dB” was then used in the reports.

26. Mr Arkley had been jointly commissioned by the claimant and the owner of No 20 St John’s Way to assess noise levels at No 20, which is located opposite the new junction at its southern end and is near the point where AECOM had carried out post-scheme recording for the respondent.

27. The results of Mr Arkley’s surveys in November 2018 showed noise levels of 73 dB outside No 20, the same level measured by AECOM at its receiver outside No 18. However, in the modelling methodology also used by AECOM, noise levels had been predicted to increase from 76 to 77 dB outside No 20. Mr Arkley noted that the modelled post-scheme noise levels do not correlate closely with actual measured levels on site taken by either KP Acoustics or AECOM.

28. Mr Arkley viewed it as good practice to measure actual noise levels on site prior to commencing works in order gain a realistic understanding of the noise levels and the noise profile including traffic idling, stop/start revving and car horns. In this instance no pre-works survey had been done, so it was difficult to assess accurately the impact evidenced by his own post-works surveys.

29. In concluding, Mr Arkley stated that it was impossible to determine the extent of any increase since the measured level of noise is lower than the predicted level and no pre-works survey was undertaken against which it could be compared. In his opinion it was logical for noise levels to have increased noticeably as the volume of traffic has increased. A doubling of traffic noise would be represented as a 3 dB increase in road traffic noise level, which is typically the point at which a difference is clearly perceivable. He commented that the residents of St John’s Way had experienced an observable subjective increase in noise levels.

30. In his report for the respondent Mr Muirhead of AECOM explained very clearly the methodologies available to assess changes in road traffic noise arising from the works. The preferred methodology was noise modelling using annual average traffic data which, unlike surveyed measurements, is not influenced by extraneous non-traffic noise and can be calculated at all facades and floor levels of noise sensitive buildings. Modelling of the traffic noise levels at the property prior to the works had been assessed in the 2016 impact assessment at around 72dB; a relatively high noise level, typical for a property close to a major road, such as the A1, in central London.

31. Mr Muirhead noted that the post-scheme volume of traffic on the A1 links of the junction is approximately double the volume on those roads pre-scheme and, all other things being equal, a doubling in traffic volume results in a 3 dB increase in traffic noise level. Given the associated reduction in traffic on St John’s Way outside the property, the increase in noise level outside the property would be expected to be slightly less than 3 dB. This was borne out by the traffic noise modelling in the 2016 impact assessment, which had predicted changes outside the property of between 2.1 and 2.3 dB.

32. Mr Muirhead concluded that the noise environment at the property had previously been dominated by traffic and that noise levels increased by around 2.3 dB as a result of the gyratory works.

33. Using the table of subjective impression of noise provided by Mr Arkley, this would be described as between ‘imperceptible’ and ‘just barely perceptible’.

34. It was acknowledged by counsel for both parties, when raised by the Tribunal, that tables provided in the 2016 impact assessment described a change in traffic noise level of 1.0 - 2.9 dB as a ‘small’ magnitude of impact, the significance of which would be a ‘slight’ adverse effect for residential properties.

35. In her witness statement the claimant explained her perception that before the works traffic had flowed smoothly past the property in one direction only and she was able to open her front windows in hot weather without suffering disturbance from noise. In the new layout the traffic lanes seemed to be narrower, and vehicles turning south west at the junction had a sharper turn to make, which led to HDVs and buses turning into the cycle lane. There were frequent near collisions and use of horns. The claimant is also now aware of ambulance sirens since the new layout requires vehicles heading to Whittington Hospital to turn into St John’s Way and pass through the new junction to access Highgate Hill.

Air quality

36. The parties addressed the physical factors of smell and fumes under the general topic of air quality. The claimant submitted her own evidence of air quality outside the property, based on data from a website ‘Addresspollution.org’ which showed levels of nitrogen dioxide (“NO2”) outside the property to be 59.02 mcg/m3, compared with the ‘World Health Organisation’s annual legal limit of 40 mcg/m3’. In cross-examination it was pointed out to the claimant, as noted in the supplementary statement of agreed facts, that the data referred to was based on ‘the latest available annualised data from 2016’. She acknowledged that when she obtained the data in 2018 she had not realised it was out of date and that it was therefore of no assistance in assessing any increase arising from the works.

37. Evidence on air quality for the respondent was provided in an appendix to Mr Alford’s valuation report. A memo from AECOM to the respondent’s surveyor Mr Forrester referred to the London Borough of Islington (“LBI”)’s annual monitoring reports and the 2016 impact assessment. It confirmed information sourced by the claimant that close to busy roads in Islington the levels of NO2 were above the 40 mcg/m3 target before the works. However, the nearest monitoring site to the property was 100 m to the south east and revealed lower levels of NO2 after opening of the works due to lower traffic levels passing that point.

38. The memo therefore looked at the 2016 impact assessment which used a modelled location very close to the property. This predicted an increase in NO2 levels of 3.9 mcg/m3 on opening in 2017, reducing to 3.0 by 2020 in anticipation of some associated benefits from the Ultra Low Emission Zone (“ULEZ”). Both were classified as moderate adverse effects in a situation where the levels already exceed targets. Modelled changes to PM10 levels were 0.5 mcg/m3 on opening and in 2020. This was classified as a negligible adverse effect.

Artificial lighting

39. Evidence on the visibility of the light controlled crossing from inside the property was supplied in photographs taken by both the claimant and Mr Alford. No technical evidence on the impact of light was given by either party.

40. In her witness statement the claimant explained that the new pedestrian/cycle crossing lights situated on the opposite side of the road shine directly into her house at all times of the day and night, affecting the use and enjoyment of the front rooms at all three levels. The front room of the lower ground floor self-contained flat is used as a bedroom and it has been necessary to add frosting to the window of that room to block out the effect of the lights.

Conclusions on the increase in physical factors

41. The expert evidence on noise levels is not in dispute and shows an increase of around 2.3 dB from the use of the works. Standard classifications confirm that this level approaches the category of ‘just perceptible’ and would have a ‘slight adverse’ effect on residential property. I acknowledge that it is the perception of the claimant that the increase in noise levels is of more significance than those descriptions suggest.

42. The expert evidence on air quality, based on modelling, showed a moderate adverse effect from increased NO2 levels, in an area where the levels were already above the 40 mcg/m3 WHO target. Changes in PM10 levels were of negligible adverse effect in a situation where existing levels were within targets.

43. It is not in dispute that as a result of the works the property is affected by new intrusive pedestrian/cycle crossing lights.

44. I am satisfied that the works did cause an increase in the physical factors of noise, fumes and artificial lighting affecting the property. The next stage is to determine whether the increase in those factors has caused depreciation in the value of the property in the open market.

Evidence on the valuation impact of physical factor increases

Assessments of value required

45. It was common ground between the experts that the actual value of the property on the valuation date should be described as the “switched on” value and the hypothetical value of the property on the same date without the additional physical factors arising from the works should be described as the “switched off” value. The difference between the two values is the amount of compensation due to the claimant.

46. This follows the practice of valuers before the Tribunal in many previous cases and provides a helpful way of understanding the limitations on the compensation payable under the Act. It is usually the case that the depreciation caused by physical factors arising from use of the works when they are switched on is only a limited element of the overall loss of value to a property caused by those works. Any loss of value caused by physical changes to the appearance of the street and the outlook from the property, such as the removal of the safety railings from the front of the property and the installation of traffic light structures and a pedestrian/cycle crossing in their place, is not compensatable under the Act.

47. In this case the switched off valuation is even more nuanced because before the works were carried out the property was already affected by significant levels of noise, fumes and general street lighting. The valuation required here might be better described as a “turned down” value. It must assume that the volume is turned down slightly, the pollution is a little less adverse and there is a pedestrian/cycle crossing present but without any lights.

Agreed facts concerning the valuation evidence

48. Although the experts had initially and helpfully agreed the switched on value of the property at £770,000, thereby appearing to reduce the dispute to the assessment of the switched off value, that consensus was relatively short-lived.

49. The experts agreed sale dates and prices of eight transactions concerning comparable properties. Different floor areas had been used by each expert for analysis of three of those properties. Mr Cohen had used floor areas provided in sale particulars or by the agent who sold the property. Mr Alford used floor areas recorded on the EPC website. Compromise was reached on two of the three differences.

50. Having agreed Mr Cohen’s identified floor area for 89a St John’s Way, Mr Alford realised later that the agreed area was larger than one he had used to analyse the sale of that flat, so the price per sq ft would be lower, affecting his average of the three transactions of flats and therefore his view of the switched off value. Since his view of the switched on value was simply that it sat £20,000 below the switched off value, I was told on the first day of the hearing that he wished to change his view of the previously agreed switched on value from £770,000 to £758,000.

51. I acknowledge that Mr Alford believed he had a duty to correct his opinion of the switched off value once a factor in the underlying analysis had been changed, and that his methodology of a simple deduction to reach a switched on value required him to change that opinion in consequence. However, it is disappointing that a previously agreed figure ceased to be so.

52. No evidence was adduced to support the switched on value, so I can conclude only that it sits within the range £758,000 to £770,000. I adopt £770,000, noting that this figure had initially seemed reasonable to both experts and that Mr Alford’s last minute change was consequential rather than specific.

Valuation evidence for the claimant

53. The claimant’s expert, Mr Cohen, is a Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and an RICS Registered Valuer who has practised in the immediate locality for many years. He stated in oral evidence that during his career he had dealt with over 2,000 Part 1 claims under the Act, none of which had been referred to the Tribunal as they had been agreed on a percentage loss basis, ranging from 0.5% to 15% depending on distance from the scheme and whether the road was new.

54. In his expert report Mr Cohen referred to the works being completed on 10 June 2017, correctly calling this the relevant date for a claim under the Act. He did not appreciate that the compensation should be assessed at the first claim day, 12 months after the relevant date, and provided his opinion of value as at June 2017. In the joint statement of facts the valuation date was agreed to be 10 June 2018 and in oral evidence in-chief Mr Cohen asked to amend the date in his report stating that it was a typographical error.

55. But the market indexation evidence within Mr Cohen’s report was calculated to June 2017, and he commented on the state of the property market when the road was first opened (i.e. June 2017) giving his opinion of “…the value of [the] property on the date the scheme was first open to the public in a ‘no-scheme world’…”. I asked Mr Cohen at the end of his oral evidence if he had, in fact, provided a valuation as at June 2017 and he said he had not. My initial concern was not that values a year earlier would be significantly different, but that Mr Cohen’s understanding of the detailed requirements of a valuation under the Act might not be strong. I do not think that Mr Cohen was deliberately trying to mislead, but he did become confused when trying to reconcile his report with the statute.

56. Mr Cohen described the property in his report as in reasonable condition, with no indications of major defects or items of essential repair although some modernisation and improvement would be beneficial. He stated ‘Simple inspection confirms that the property is undoubtedly adversely affected by noise, vibration, smell, fumes, smoke and artificial lighting…’. His description of the changes resulting from works was ‘…post scheme there are three extra lanes of traffic, which has changed a three lane single direction road to a seven lane dual carriageway, which I estimate carries at least twice the volume of traffic’. These comments strike me as hyperbole and Mr Cohen neither supplied nor referred to any empirical evidence to support his assertions.

57. In cross-examination Mrs Townsend pressed Mr Cohen on the basis for his assertions and whether he had separated out the physical effects arising from the works. He held firm to his view that a hypothetical purchaser in the market does not have any evidence of acoustics or pollution and that his opinion of the effect of the scheme on the value of the property reflected that of the man in the street.

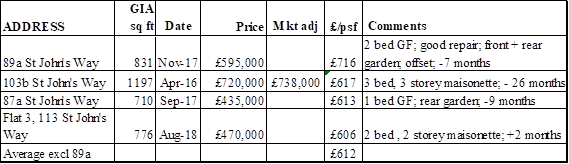

58. Mr Cohen provided evidence of six sales between April 2016 and August 2019 of houses at 21 Giesbach Road, 75 St John’s Way and 26 Grovedale Road and of flats at 103b, 87a and 89a St John’s Way. Descriptions, commentary and analysis of price per sq ft were provided for each and the individual transactions are reviewed below. He also referred to the marketing of 105 St John’s Way in 2018, which was withdrawn unsold.

59. Without providing any overall analysis of how the evidence informed his final opinion of value, Mr Cohen placed a value of £1,000,000 on the property in what he called the no-scheme world, i.e. the switched off value. His opinion of the “current value” following the scheme was in the range £750,000 - £800,000. This led him to place a figure of £225,000 on the “gross diminution in value as a result of the scheme”.

60. In an alternative approach, with which he was more familiar from his previous experience of claims, Mr Cohen applied a percentage reduction of 20% to his no-scheme value of £1,000,000 to assess compensation of £200,000. He framed this in the context that the most likely purchaser of the property post-scheme was an investor for letting purposes, looking for income and with no real hope of the value keeping pace with local property price inflation.

61. Mr Cohen concluded by averaging his two figures to arrive at a compensation figure of £212,500.

62. In cross-examination Mr Cohen admitted that in his previous experience of claims under the Act the maximum achieved in settlement of compensation was depreciation of 15%. When questioned about the range of settlements he had achieved between 0.5% and 15%, he explained that the highest level was for a property in close proximity to a new road scheme.

Valuation evidence for the respondent

63. The respondent’s expert, Mr Alford, is a Member of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and an RICS Registered Valuer who is Director and Head of Lease Consultancy in Copping Joyce Surveyors Limited in London. He is a specialist within his firm in expert witness work and has provided expert evidence for a number of different purposes. He had compulsory purchase practice experience from 1988 - 1990 when he acted for a number of home owners affected by works to the North Circular Road. During an earlier part of his career he had practiced in Islington and was familiar with the property market in the area.

64. In his report of November 2019, Mr Alford described the property location as noisy, with poor air quality, next to a busy section of the A1. With no car parking close to the property he viewed it as unlikely that a family would wish to live there, unless purchasing at a substantial discount. He felt that this was a situation unchanged by the works. He noted that a majority of properties in the same parade were split in two, with two storey maisonettes over ground floor flats, and that the property was already occupied in that manner. He concluded that the most likely purchaser of the property would be an investor, looking to complete the separation into two units for letting.

65. Mr Alford therefore first valued the property using the investment method. From comparable evidence of asking rents for flats in the immediate area, he estimated a total market rent of £32,760 per annum from two flats in the property, and an overall investment value of £819,000, based on a yield of 4% which had been derived from research published by Savills and Knight Frank. I note that the investment value from a low yield such as this is very sensitive to small adjustments in that yield. From this figure he deducted his estimate of £55,000 for the costs of separating the house into two flats, including gaining planning consent, to arrive at a market value of £764,000.

66. Mr Alford then used the comparable method to assess the value of the property as two flats, based on evidence of sales between September 2017 and January 2018 of flats at 87a, 89a and Flat 3, 113 St John’s Way. He adjusted the average price per sq ft of £645 down by 10%, to reflect the poorer location of the property, to reach a figure of £832,500. Deducting £55,000 (as above) for separation and planning, he reached a market value of £777,500.

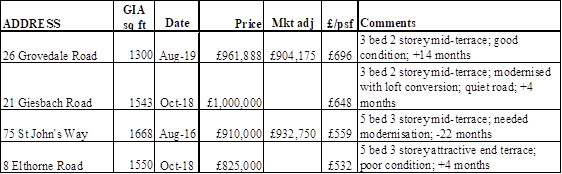

67. Finally, Mr Alford used the comparable method to assess the value of the property as a single house. He provided evidence of three sales at 21 Giesbach Road, 8 Elthorne Road, and 75 St John’s Way. Applying adjusted figures per sq ft to the floor area of the property he reached a value of £777,000.

68. Four of Mr Alford’s six comparable transactions are also used by Mr Cohen and all the transaction evidence is reviewed below.

69. In order to assess what, if any, difference to value would apply after the scheme, Mr Alford included evidence on traffic numbers and flow, noise and air quality, supplied to him by the respondent. He concluded that as the change in noise level was classified as barely perceptible, and the changes in air quality were marginal, the prime concern of a prospective investment purchaser would be the artificial light generated from the pedestrian/cycle crossing. He viewed this as a factor which might lead to frequent changes of tenant, with associated costs and voids, which an astute purchaser would anticipate and allow for by a deduction of £20,000.

70. In conclusion, Mr Alford placed a switched off value of £778,000 on the property and a switched on value of £758,000 with the works in use.

The transaction evidence for houses

71. Evidence was provided of four house sales within the locality but unaffected by the works. Date, price and floor area were agreed for 8 Elthorne Road, 21 Giesbach Road and 26 Grovedale, but there remained a difference of opinion over the floor area of 75 St John’s Way. Mr Alford continued to rely on the EPC area of 1,744 sq ft (giving a lower price per sq ft) and Mr Cohen on the area of 1,668 sq ft supplied by the selling agent. I prefer Mr Cohen’s figure as, in my own experience, EPC stated floor areas are notoriously unreliable. I give no consideration to the marketing of 105 St John’s Way referred to by Mr Cohen since that never resulted in a sale and is not market evidence.

72. I have previously noted that Mr Cohen provided no evidence in his report of adjustments made to the comparable evidence to arrive at his opinion of value, but in cross-examination he was able to shed more light on his thoughts, which assists me in my analysis below.

73. 8 Elthorne Road, is a five-bed end of terrace house of 1,550 sq ft sold in October 2018 for £825,000 (£532 per sq ft). It was agreed to be in poor condition, so the sale price required upward adjustment to be comparable with the subject property (in average/reasonable repair). Mr Alford adjusted up to £1,000,000, giving an adjusted price of £645 per sq ft, and then discounted by 15% for its superior location to get £548 per sq ft. Mr Cohen thought 8 Elthorne Road would be worth £1,200,000 when refurbished and that a maximum adjustment of 5% would be appropriate for location. This would give a figure of £735 per sq ft - the highest of any comparable considered.

74. 21 Giesbach Road is a three-bed mid-terrace house of 1,543 sq ft sold in October 2018 for £1,000,000 (£648 per sq ft). It was modernised and well maintained with the third bedroom in converted roof space. Giesbach Road has no through traffic and appears to be a desirable location. Mr Alford discounted the sale price by 15% to allow for location, to get a figure of £551 per sq ft. Mr Cohen maintained (without giving detail) that the road had a poor reputation and that the maximum discount for location should be 5% to give £616 per sq ft.

75. 75 St John’s Way, is a five-bed three storey mid-terrace house of 1,668 sq ft sold for £910,000 (£546 per sq ft) in August 2016. It was in need of modernisation and the experts agreed that at least £100,000 would have to be spent to bring it to the equivalent condition of the subject property. Assuming an adjusted value of £1,000,000 (£600 per sq ft) Mr Alford adjusted down by 10% for location to get £540 per sq ft. This required further adjustment upwards for market movement over the period to June 2018. Mr Alford used the Nationwide Property Index for Greater London to adjust upwards by 2.82% which gives £555 per sq ft. Mr Cohen adjusted down for location by 5% to get £570 per sq ft and then up by 2% for market movement, giving £581 per sq ft.

76. Finally, 26 Grovedale Road, is a three-bed mid-terrace house of 1,300 sq ft sold for £961,888 (£740 per sq ft) in August 2019. It was well maintained and in a superior location. Mr Cohen proposed a discount for location of 10% and a downward adjustment for market movement of 6% to give a figure of £626 per sq ft. Mr Alford did not give evidence on this sale.

77. Mr Alford’s adjusted prices range from £548 to £555 per sq ft. When applied to the floor area of the property at 1,434 sq ft the range of switched off values is £785,832 to £795,870.

78. Mr Cohen’s adjusted prices range from £581 to £735 per sq ft. When applied to the floor area of the property at 1,434 sq ft the range of values is £877,608 to £1,053,990.

79. This detailed and divergent analysis of agreed transaction evidence by two experts illustrates clearly how valuation opinions can differ widely on largely the same evidence.

The transaction evidence for flats

80. Evidence was provided of four flat sales within the locality but unaffected by the works. Date, price and floor area were agreed for all of them. Again, Mr Cohen provided his view in cross-examination on suitable levels of adjustment where required.

81. 87a St John’s Way, a one-bed ground floor flat of 710 sq ft, sold in September 2017 for £435,000 (£613 per sq ft). It was in a reasonable state of repair and away from the busy junction. Mr Alford made a 10% discount for location to get £551 per sq ft. Mr Cohen preferred 5% which gives a figure of £582 per sq ft.

82. 89a St John’s Way, a two-bed ground floor flat of 831 sq ft sold in November 2017 for £595,000 (£716 per sq ft). It was in a good state of repair and had the benefit of front and rear gardens in a location offset from its neighbour 87. Mr Alford made the same 10% discount for location to get £644 per sq ft and Mr Cohen would use 5% to get £680 per sq ft.

83. Flat 103b St John’s Way, a mid-terrace three-bed and two-bath maisonette of 1,197 sq ft over three floors in a reasonable state of repair, sold in April 2016 for £720,000 (£602 per sq ft). Mr Alford did not rely on this sale. Mr Cohen used it only as a whole transaction comparable but stated that he would use no more than a 5% discount for location, which gives £571 per sq ft. The sale was 26 months before the valuation date and should be adjusted upwards for market movement, for which I use 2.5% to get £585 per sq ft.

84. Finally, Flat 3, 113 St John’s Way, a two-bed mid-terrace maisonette of 776 sq ft over two floors sold in August 2018 for £470,000 (£606 per sq ft). Mr Alford made a 10% discount for the location, to get £545 per sq ft. Mr Cohen did not refer to this transaction in his evidence.

85. Mr Alford’s adjusted prices are £545, £551 and £644 per sq ft. When applied to the floor area of the property at 1,434 sq ft the range of values is £781,530 to £923,496, Mr Alford used the average of the three figures at £580.50 per sq ft giving a value of £832,500. From this he deducted £55,000 for the costs of converting the property properly into two flats, including the cost of obtaining planning permission. He rounded to £778,000 and this became his final stated opinion of the switched off value of the property.

86. Mr Cohen’s adjusted prices (following cross-examination) are £571, £585 and £680 per sq ft. When applied to the floor area of the property at 1,434 sq ft this gives a range of values from £818,814 to £975,120. Mr Cohen did not give an opinion of likely costs to convert the property into two lettable flats.

Discussion

87. Whilst the property is in single ownership at present, and occupied by members of the same family, it is clear to me from the way in which it is occupied and the evidence of other properties in St John’s Way, that its most likely purchaser would be an investor wishing to let it as two flats. Mr Alford valued the property on that basis and Mr Cohen stated in his report that the most realistic purchaser for the property was an investor for letting purposes, albeit that he believed this had only become the case after implementation of the works. I therefore look at the transaction evidence for flats first and then the evidence of houses as a check.

88. In comparison with the transaction evidence for houses, neither expert made adjustments for condition to the evidence for flats, leaving less scope for difference between them. In both analyses the highest figure is derived from the sale of 89a St John’s Way and this appears to be an obvious outlier. When I inspected the location of comparable properties I was struck by the fact that 89 is different. It is located on a bend in St John’s Way, offset from the properties on either side of it and with a front garden big enough to have a tree in it. This may not be the whole reason for difference but with evidence from three other sales giving a tight range between £545 and £585 per sq ft I will not give it weight in my assessment.

89. The transaction evidence for flats is summarised below, in descending order of price per sq ft, with one adjustment for market movement:

90. If I exclude the sale of 89a the average sale price of £612 per sq ft can be considered as a benchmark for further adjustment if appropriate. I make a downward adjustment of 5% for the less desirable location by a junction, to get £581 per sq ft and an overall figure for 1,434 sq ft of £833,372, which I round to £835,000.

91. In order to put that figure into a market context I also consider the transaction evidence for houses, which is summarised below in descending order of price per sq ft and with adjustment only for market movement:

92. There are clearly two clusters: the modernised properties in good locations and properties in need of modernisation. I would expect the price per sq ft for the property to be between the two clusters but closer to the lower end as it is in a poorer location and does require some modernisation. At £581 (from paragraph 90 above) it would fall into that category.

93. Looking at overall price and comparing a proposed £835,000 switched off value for the property with the range of house sales evidence, it would sit very close to the bottom end, just above 8 Elthorne Road which sold only four months later. Elthorne Road is slightly larger, with an extra bedroom, and although in poor condition is an attractive property in a good location at the end of a terrace. As a comparative investment it would stand up well beside the property.

94. 75 St John’s Way is the closest comparable in terms of location, although it is in a quieter end of the road away from the junction. It is larger overall and provides one more bedroom so the adjusted price of £932,750 sits appropriately above the proposed £835,000 for the property.

95. I conclude that £835,000 is the minimum which would be paid for the property as a switched off value. I acknowledge that an investment purchaser would typically expect to make a deduction for the costs of conversion into two flats, but note that the expenditure would also result in two flats of better condition than the property. The market for houses would support the value of £835,000 without deduction and I therefore assess the switched off value of the property at £835,000.

96. At this stage it is necessary to remember that section 1(1), 1973 Act gives a right to compensation “Where the value of an interest in land is depreciated by physical factors caused by the use of public works”. Not all of the changes to the setting and environment of the property caused by the works and which have had an adverse effect on its value fall within the scope of the “physical factors” listed in section 1(2), and it follows that not all of the deleterious changes are eligible for compensation. The works have created a bigger and busier junction, removed kerbside railings from in front of the property and spoiled the street outlook (even without lights) by the relocation of traffic light structures and installation of a pedestrian/cycle crossing. Loss of value caused by those changes contributes to the total diminution of £65,000 but cannot be compensated under the Act.

97. The diminution in value which is eligible for compensation is represented by the difference between the switched on value of £770,000 and the value of the property with the works completed and in use, but without the marginal increase in noise, smell, fumes and artificial lighting which the parties have agreed arise from their use. This distinction is too fine to be measured using market evidence which has already been adjusted to put a value on the property because of its less desirable location. As both experts have confirmed, no buyer looking at the property would consider the detailed noise and pollution evidence which has been provided in evidence. On the basis of the evidence, £835,000 is the value of the property had the works not been undertaken at all. In other words it is a ‘before’ value to be compared with the ‘after’ value of £770,000, and is not a base line from which to measure the diminution in value attributable only to the relevant physical factors. The only way of arriving at the diminution attributable to the physical factors alone is by applying valuation judgment to apportion the total diminution of £65,000.

Disposal

98. I determine that £39,000, equivalent to 60% of the total diminution, should be apportioned as compensation. This is 4.67% of £835,000 and therefore sits appropriately in the usual range of compensation payments arising under the Part I of the Act.

99. This decision is final on all matters save costs. A letter on costs accompanies this decision.

|

|

|

Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV 17 November 2020 |

Addendum on Costs

100. I have received submissions on costs from Mrs Townsend for the respondent, from Mr Gallagher for the claimant and from the claimant herself.

101. On 19 December 2019 the respondent wrote to the claimant with a sealed offer of £65,500 plus reasonable legal/professional costs within 21 days of acceptance. The offer was open for acceptance until 4.00 pm on 24 January 2020. The claimant made a counter-offer of £185,000 on 2 January 2020, which she reduced to £150,000 on 13 January 2020. No further offers were made.

102. The claimant requested mediation in email exchanges with the respondent’s in-house solicitor, Mr Francis, between 7 December 2019 and 13 January 2020. In an email of 10 January 2020 Mr Francis explained that mediation required the consent of both parties and should be meaningful and likely to produce a settlement. The draft statement of agreed facts and issues had been compiled and he believed that the valuation differences were not likely to narrow. He stated that the respondent had made an offer far in excess of its valuation, in order to protect the position on costs, but would not enter into a ‘bartering negotiation’.

103. The respondent submits that it is the more successful party in the case and seeks an order that the claimant pay its costs from 20 December 2019, assessed on the standard basis if not agreed. It also seeks that in any order for costs in the period prior to 19 December 2019, the fact that it is the more successful party should be taken into account, whilst making a reasonable allowance for expenditure incurred by the claimant in obtaining professional advice on value.

104. Mr Gallagher submits for the claimant that the rejection of mediation by the respondent should be taken into account on the question of costs, together with the claimant’s measure of success in achieving compensation for the impact of a wider range of physical factors than acknowledged by the respondent. He submits that the claimant should have her costs up to and including 19 December 2019, plus costs for the period from 20 December 2019 to 13 January 2020, and that thereafter there should be no order for costs.

105. In proceedings under the Land Compensation Act 1973 the Tribunal has a discretionary power to award costs, in accordance with s.29 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007. Rule 10(6)(b) of the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) Rules 2010 (“the Rules”) applies in proceedings for injurious affection of land and rule 10(8) requires the Tribunal to have regard to the size and nature of the matters in dispute. In exercising power under the Rules the Tribunal must seek to give effect to the overriding objective of dealing with cases fairly and justly.

106. The Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) Practice Directions 2020 (“the 2020 Practice Directions”) state at paragraph 24.10:

“... The general rule is that the successful party ought to receive their costs from the unsuccessful party. … The Tribunal will have regard to all the circumstances of the case, including the conduct of the parties; whether a party has succeeded on part of their case, even if they have not been wholly successful; and admissible offers to settle. The conduct which may be taken into account will include conduct during and before the proceedings; whether a party has acted reasonably in pursuing or contesting an issue; the manner in which they have conducted their case; whether or not they have exaggerated their claim; and whether they have unreasonably refused to engage in ADR or comply with a relevant pre-reference protocol.”

107. The claimant submits that because the respondent refused to acknowledge that she had any claim for compensation, despite the evidence of her noise expert and valuer, she had no option but to make a reference to the Tribunal. She did this as a litigant in person as her funds did not permit expense on a solicitor as well as a barrister for the hearing. It was only once the respondent had received the report of its own expert valuer, dated 13 November 2019, that it acknowledged her claim for compensation had some validity and entered into negotiations with her. It was therefore reasonable for her to commence proceedings in this Tribunal and to incur costs in obtaining evidence in support of her claim up to the point when she received the sealed offer from the respondent on 19 December 2019.

108. I consider that the claimant is entitled to her costs up to the date of the respondent’s offer. Up to that time she is entitled to be regarded as the successful party in the reference, having succeeded in obtaining an award of compensation which would not otherwise have been available to her. I have considered whether she should have her costs after that date. It is not clear to what extent the claimant incurred further costs in the period between receiving the offer on 19 December 2019 and the breaking down of attempts to settle on 13 January 2020. However, it would have been reasonable and fair for her to seek advice on the offer she had received and for her to recover her costs for a short period while she did so. That period must be taken to have come to an end on 2 January 2020 when she made her own offer of £185,000 which was clearly a rejection of the respondent’s offer.

109. I therefore award the claimant her costs on the standard basis up to and including 2 January 2020.

110. I now look at the appropriate award for costs incurred by the parties between 2 January 2020 through to the hearing on 8 September 2020. In respect of that period the respondent is the successful party, having achieved an outcome more favourable to it than its offer of £65,500 plus costs which the claimant had rejected. In principle the respondent is entitled to an order for the payment of its costs during that period unless there is some reason for the Tribunal to make a different order. In considering whether a different order is required, the most relevant consideration will be conduct and whether the respondent unreasonably refused to engage in mediation.

111. By 10 January, when mediation was refused, it will have been apparent to the respondent that the claimant was entitled to a five figure sum in compensation, but the scale of her claim was evidence that she was not well advised on the limitations of a claim under Part I of the 1973 Act. As a large and well-resourced organisation, in expensive litigation with a private individual who was obviously in receipt of bad advice, it would have been reasonable for the respondent to engage in mediation in an attempt to achieve a just settlement of the claimant’s claim and to mitigate its own costs in defending it. Mediation might not have resulted in settlement, but with the assistance of a skilful mediator it might have done. The claimant was clearly keen to achieve a settlement and mediation would have given space and scope for her to appreciate the limitations of her claim and form a more realistic assessment of its value. The respondent’s determination that it would not offer more than it considered the claim to be worth was not a good enough reason for rejecting mediation and in my judgment, in the circumstances of this case it was unreasonable.

112. It is not possible to quantify the chances of a successful mediation with any confidence but in my judgement the respondent’s negativity should be given considerable weight. Doing the best I can, I allow a discount of 25% for the refusal to engage in mediation and order that the claimant shall pay 75% of the respondent’s costs from 2 January 2020 through to the end of the hearing. Those costs are to be set off against the respondent’s liability to pay the claimant’s costs incurred before 2 January 2020. Each party shall pay their own costs of the submissions on costs exchanged after I handed down my decision. In the absence of agreement, the costs shall be assessed by the Registrar on the standard basis.

Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

9 February 2021

APPENDIX 1