Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) >> Fearon & Anor v The Environment Agency Re Tickenham Mill [2019] UKUT 97 (LC) (29 March 2019)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/LC/2019/97.html

Cite as: [2019] UKUT 97 (LC)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

UPPER TRIBUNAL (LANDS CHAMBER)

|

|

|

Neutral Citation Number: [2019] UKUT 97 (LC)

UTLC Case Number: LCA/63/2018

TRIBUNALS, COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007

COMPENSATION – Water Resources Act 1991 – the Upper Land Yeo – artificial watercourse – whether the raising of penning boards at a weir during the months of December to April amounted to an interference with Mill owners right to natural flow of water – Held – the natural flow was with the penning boards raised – no interference – claim for compensation dismissed.

IN THE MATTER OF A REFERENCE UNDER SCHEDULE 21 PARAGRAPH 5 OF THE WATER RESOURCES ACT 1991

|

BETWEEN : |

|

|

|

|

(1) MICHAEL FEARON (2) SYLVIA MARY FEARON |

Claimants |

|

|

and |

|

|

|

THE ENVIRONMENT AGENCY |

Respondent |

|

|

|

|

Re:Tickenham Mill,

232 Clevedon Road,

Tickenham,

Clevedon

Somerset

BS21 6RX

Before : His Honour John Behrens

Sitting at: Royal Courts of Justice, Strand, London WC2A 2LL

on

19 March 2019

John Bates (instructed on a Direct Access Basis) for the Claimants.

Ned Westaway (instructed by The Environment Agency) for the Respondent.

© CROWN COPYRIGHT 2019

The following cases are referred to in this decision:

Pearson v Foster [2017] EWHC 107 (Ch)

Baily & Co v Clark, Son & Morland [1902] 1 Ch 649

Tate & Lyle Industries Ltd v Greater London Council [1983] 2 AC 509

Armstrong v Sheppard [1959] 2 QB 384

Liggins v Inge 7 Bing 683.

Manolete v Hastings [2013] EWHC 842 (TCC)

DECISION

Introduction

1. This is a claim for compensation under para 5 of Sch 21 of the Water Resources Act 1991 “(WRA1991”).

2. The Claimants are the owners and occupiers of Tickenham Mill which comprises housing outbuildings and a garden. The Mill building spans a watercourse known upstream as the Upper Land Yeo. It is an artificial perched watercourse. At Tickenham Mill the watercourse divides into two – the Northern Channel which runs under the Mill Building and the Bypass Channel. These channels later merge into a single channel some 75m downstream. The water passing through the Northern Channel originally provided power to the Mill via a wheel which was replaced by a turbine. Attempts were made by the Claimants’ predecessor in title to restore the turbine without success. Mr Fearon has managed to make it operational and seeks to use it to generate power for the Mill and to take advantage of the Feed in Tariffs Scheme (“FITS”).

3. At the point where the watercourse divides at the mouth of the Bypass Channel there is a sluice (“Sluice C”). Sluice C is formed of a weir together with a penning mechanism. This mechanism is comprised of wooden penning boards fixed to lifting gear which can be manually operated to lower or raise the boards. When the penning boards are lowered they extend the height of the weir. This has the effect of holding back the water at a higher level in the channel upstream. It also has the effect of diverting a greater proportion of the flow in the main river towards the Northern Channel. Conversely when the penning boards are raised water flows over the top of the weir and the proportion of water flowing into the Bypass Channel increases.

4. The Environment Agency (“EA”) has sole responsibility and authority to operate Sluice C. Its policy is to lower the penning boards between April and December each year and to raise them between December and April. The rationale for this policy is as follows:

5. The boards are lowered between April and December to maintain a managed level of water in the Upper Land Yeo. This is to reduce the risk of bank collapse.

6. The boards are raised between December and April so as to reduce the flood risk to Tickenham Mill. When flows are at their highest the EA believes that there is a risk that they could cause flooding to Tickenham Mill and other properties upstream. Raising the boards reduces the risk.

7. The Claimants contend that the raising of the penning boards reduces the flow of water through the Northern Channel to such an extent that the turbine is inoperable. They contend that they are entitled to compensation for the loss of FITS for the periods between December and April in each of the three years commencing in December 2015.

8. The claim is disputed by the EA and raises a number of questions of law. It was allocated to the simplified procedure probably because of the amount originally claimed by the Claimants – some £10,000. In those circumstances it was necessary to deal with the facts and the law within a day. The matter came on for hearing on 19 March 2019. As Mr Fearon had increased the value of the claim to £44,000 in his witness statement and as there were substantial issues over quantum the convenient course was to deal solely with the question of liability. If and insofar as the claim succeeds the issue of quantum can be dealt with at a later date probably by a surveyor member of the Tribunal.

9. Two witnesses gave evidence before me - Mr Fearon on behalf of the Claimants and Mr Flagg, a Chartered Civil Engineer employed by the EA whose duties include responsibility as catchment engineer for flood risk management and water level management on the Upper Land Yeo. In the course of their evidence I was referred to a significant number of documents. The evidence on liability lasted for half a day. The submissions on the law and the facts (which were timetabled by me and were probably slightly shorter than either Counsel would have preferred) lasted a further half day whereupon the decision was reserved. Both Counsel produced detailed skeleton arguments upon what was, for me at least, an unfamiliar area of the law. I am most grateful to them.

Geography

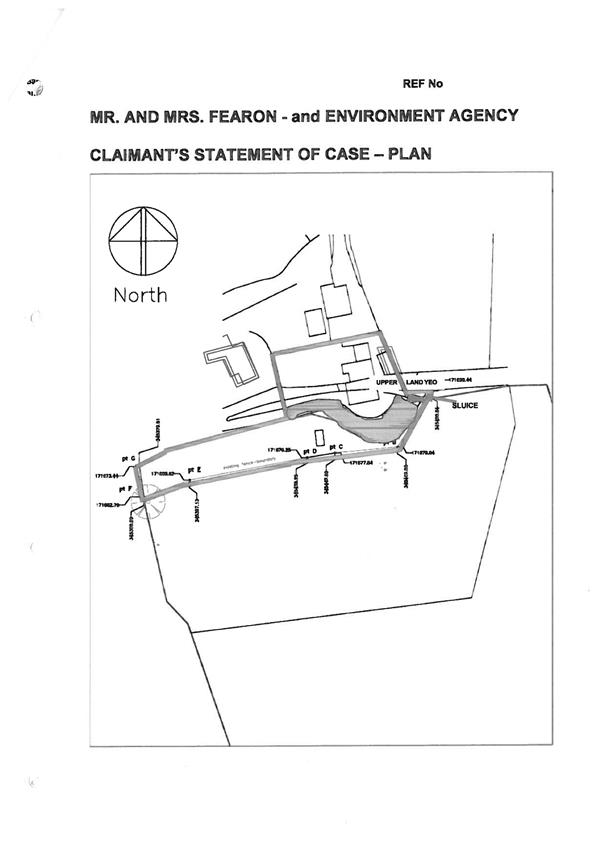

10. As an annex to this decision I have incorporated two plans. The first is the plan taken from the Claimants’ registered title of the land. It shows the two channels and Sluice C.

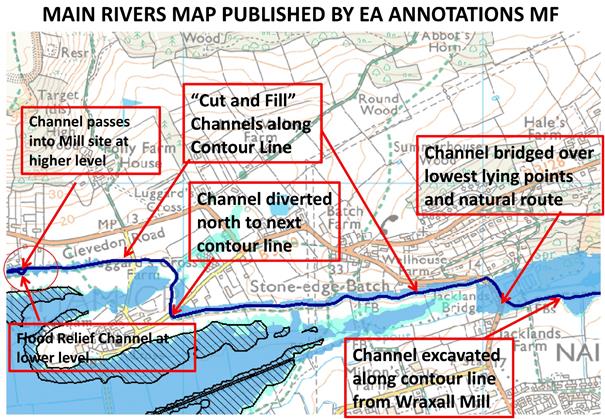

11. Water from upstream in the Upper Land Yeo approaches Tickenham Mill in a single channel approximately 6 m in width at the top. This stretch is a perched (non-natural) watercourse. The river is diverted from its natural course into an excavated channel at or upstream of Wraxall Gauging Station. It is then ducted through a cut and banked channel to Tickenham Mill. This can be seen in the second plan annexed to the decision which is the main Rivers Map as published by the EA with annotations by Mr Fearon. The route of the artificial watercourse from Wraxall Gauging Station can be seen on the plan. At the left hand side of the plan one can see the channel passing through Tickenham Mill and the Bypass Channel (described by Mr Fearon as the Flood Relief Channel) to the south.

History

12. It is not known when the Land Yeo was moved from its natural course, but it is thought likely that this happened more than 600 years ago. It is also thought likely that there has been some structure such as a Mill or pumping station at the site of Tickenham Mill for a very long time.

13. In 1938 a predecessor in title of the Claimants, the Clevedon Water Company (“CWC”) was granted a licence by the Somerset Rivers Catchment Board (“SRCB”) to construct a weir immediately upstream of the Mill building but downstream of Sluice C. This would have been an obstruction to the flow and would have increased the upstream water level.

14. The works carried out pursuant to the licence are shown schematically on a diagram prepared by Mr Flagg for the purpose of this hearing. They included the installation of a turbine in place of the mill wheel, the creation of a concrete sill, a culvert entrance to the mill and a small barrier (Sluice A) immediately in front of the entrance to the Mill. Although the details are not clear it is known that the turbine operated for some time. It had, however fallen into disuse by 1966.

15. During the 1950’s and 1960’s the Upper Land Yeo was treated as a highland catchwater. There were persistent complaints from farmers and landowners to the south of the river who blamed the waterlogging of land on Tickenham Moor on leaking and flooding from the Upper Land Yeo.

16. In the 1950’s SRB carried out dredging work in the Upper Land Yeo to increase the capacity of the river in an attempt to reduce the incidence of flooding. In the early 1960’s concerns over the stability of the left bank of the Upper Land Yeo upstream of Tickenham Mill led to bank strengthening works

17. In the same period improvements were made to the drainage of Tickenham Moor, Clevedon Moor, and Kenn Moor. In the mid 1960’s an assessment was made of the arrangement at Tickenham Mill. It was found to be inadequate to pass the flood flows that the improved river channel would be likely to convey.

18. In 1966 an agreement was made between the Bristol Water Company (“BWC”) – the successor to CWC – and SRA whereby in early 1968 works were carried out to modify the arrangement at Tickenham Mill so as to enable it to manage increased flows especially in flood conditions.

19. The works are shown schematically in a diagram prepared by Mr Flagg. In summary the width of the weir was increased from 8ft 3ins to 14ft 6ins and its height was lowered by 12 ins. A new mechanical penning system was introduced (Sluice C) with penning boards attached to a mechanism which allowed them to be lowered or raised to manage and control the flow and level of the river.

20. In addition to Sluice A and Sluice C there is also a maintenance sluice – Sluice B. This has been present prior to 1938. It is essentially a small control sluice just downstream of Sluice C which can provide additional capacity to the Bypass Channel in extreme flood conditions. It also allows for drainage for maintenance purposes. It is not relevant to any of the issues in this dispute.

21. In the course of his evidence Mr Fearon suggested that there must have been some form of penning boards on top of the weir before the 1968 operations. There is no reference to this in any of the records unearthed by Mr Flagg. The photograph relied on by Mr Fearon does not show the boards. In his Reply Mr Bates tried to place some reliance on a document introduced by Mr Fearon. At a hearing before the House of Commons Select Committee on 8 th July 1937 in relation to the Clevedon Water Bill Mr Pye agreed that when the surface water in the river falls below 30.52 feet the water wheel stopped working. By comparing this with the levels shown on Mr Flagg’s diagrams Mr Bates invited me to infer that there must have been boards present at that time. Whilst it is possible he is right, I am not satisfied on the balance of probability that there were any boards before the 1968 works. I note that a letter written by an Engineer from SRA to the Chief Engineer of BWC on 25 April 1968, there is reference to the “new penning door erected at the weir”. Whilst in no way conclusive this suggests to my mind that the penning board arrangement was new.

22. It was part of the 1966 agreement that BWC contributed £350 towards the cost of the modifications and that SRA would in future operate the sluice gates and the new penning boards erected at the weir.

Operation of the penning boards.

23. The EA and its predecessor SRA have had the sole responsibility and authority to operate Sluices B and C since 1968. As far as can be ascertained there has been no material change in the management and operation of Sluices B and C since then. There is, however, no documentary or other evidence of what happened between 1968 and 1989. Both Mr Fearon and Mr Flagg however were satisfied that since 1989 it has been the policy to lower the boards for the summer (April to December) and raise them for the winter (December - April).

24. There was some debate in the evidence as to the rationale for lowering and raising the boards. In his written evidence Mr Flagg referred to a 2002 Water Level Management Plan which recommended the raising and lowering of only one of the boards in April and November. This guidance has not been followed strictly in that both boards are raised and lowered. According to Mr Flagg this is to create a higher water level upstream in summer to maintain the moisture content of the banks and prevent cracking and to ensure that there is sufficient water above Jacklands Bridge which is further upstream. In any event the departure from the guideline is not relevant to the present dispute as the Claimants would like both boards lowered for the whole year.

25. Mr Fearon took issue with the EA’s rationale for raising the boards in December. First, he pointed out that there is no evidence of Tickenham Mill ever flooding. Second, he referred me to a Pre-Feasibility Report carried out by JE Jacobs (“the Jacobs report”) for the EA in respect of the Upper Land Yeo between Jacklands Bridge and Tickenham Mill. In para 4.3.7 the author expressed the view that the lowering and raising of the penning boards results in only a negligible change in capacity of the weir. Thus this has only a nominal effect upstream in the study reach. One of the options suggested by the author (Option 3) involved permanent removal of the penning boards [1] . This would have lowered the effective weir level in summer months. This would in the opinion of the author however only result in a small change to the levels.

26. Mr Flagg pointed out that the report had to be read in the context of its purpose which was to assess whether there was sufficient probability of flooding to justify further funding from DEFRA. The report concluded there was not. He disagreed with some of the analysis in the report. He justified the policy of raising the boards in winter on the following grounds:

27. If the boards are in the elevated position this can lead to overtopping of the left bank of the Upper Land Yeo. There were concerns about the integrity of the bank. His work with the EA over many years with many of the rivers showed that overtopping can lead to bank failure.

28. Further upstream there is an asset of the Internal Drainage Board which is used to feed water to the low lying moor. Raising the boards reduces the water level and facilitates this.

29. There is a trout farm close to Jacklands Bridge which has been prone to flooding. The owner has contacted the EA about flooding on a number of occasions. Raising the boards lowers the level and reduces the risk.

30. There is a risk of flooding to Tickenham Mill itself. Mr Flagg accepted that Tickenham Mill had not flooded in the past but still considered there was a risk.

The turbine

31. As already noted the turbine was installed by CWC in 1939. It had fallen into disuse by 1966. In 1981 BWC sold the site to Dr and Mrs Miller. The auction particulars describe it as a detached cottage with superb riverside position with enormous potential for a fine residential conversion. The Special Conditions attached to the draft Contract include a condition that the property is sold subject to Wessex Water Authority’s right of access to operate the sluices. However the actual contract is not in evidence. Furthermore, the conveyance makes no reference to the right.

32. In any event Dr Miller attempted to revive the turbine without success. Mr Fearon expressed the view that it was not correctly balanced. Dr and Mrs Miller sold Tickenham Mill to the Claimants in October 1988. In 2015 Mr Fearon upgraded the turbine, cleaned it out and employed a firm of engineers to connect it to generating equipment.

33. The Claimants started generating electricity in September 2015 and continued until the boards were raised on 2 nd December 2015. The flow passing through the turbine was so low that it was impractical to attempt to generate until the boards were lowered in April 2016. Some electricity was generated between April and June 2016. However, Mr Fearon found it very time consuming and relatively unproductive. The turbine has not been used since June 2016. The Claimants have received one payment of £545 under the FITS scheme.

Complaints

34. There has been extensive communication between Mr Fearon and the EA since 2015. In addition, there has been a site meeting attended by Mr Fearon, Mr Flagg, and other interested parties including the owner of the trout farm, representatives from the Internal Drainage Board and other environmental groups. The other interested parties did not agree that the EA should change their practice of raising the penning boards for the winter months. Mr Flagg said that the EA had carried out further investigations to improve its understanding of how the Upper Land Yeo operates in more detail. Without going into detail, it used a different model (JBA model for Clevedon) to make a more comprehensive assessment of the interaction of the assets. The EA also used telemetry in the river to observe actual water levels. The outcome of the work (which was shared with Mr Fearon) was that the lowering and raising of the boards does influence the water levels and in particular that leaving the boards lowered in winter would increase the flood risk.

Reasonableness

35. Whilst there may be room for differing views on the effectiveness of raising and lowering the boards, it is to my mind quite plain that the EA’s management of Sluice C by raising the boards in December and lowering them in April is reasonable. They have considered the position in detail, consulted interested parties and reached a perfectly rational solution. In his closing submissions Mr Bates made it clear that it was no part of the Claimants´ case that the EA´s practice or conduct was unreasonable. In my view he was right to make that concession.

Discussion

36. It is common ground between the parties that the EA’s management of Sluice C falls within the statutory powers at ss.165(1)(b) and (1D)(g) WRA 1991. Para.5 of Sch.21 provides:

“(1) Where injury is sustained by any person by reason of the exercise by the appropriate agency of any powers under section 165(1) to (3) of this Act, the appropriate agency shall be liable to make full compensation to the injured party.

37. It is also common ground that to demonstrate injury the Claimants must show that in the absence of statutory authority the EA would be liable in damages at common law.

Riparian rights

38. The first question to be decided is the nature of the Claimants’ rights as riparian owners of the artificial watercourse. Mr Bates referred me to the case of Pearson v Foster [2017] EWHC 107 (Ch) paras 63 – 69 where Newey J summarised the law:

39. The basic principle is that “[t]here is no natural right to water in an artificial watercourse” (Halsbury’s Laws of England, volume 87, at paragraph 999)”. [para 63]

40. There are, however, various cases in which riparian rights have been held to exist in respect of an artificial channel This is where it may have been made originally under such circumstances and have been so used as to give all the rights that the riparian owners would have had if it had been a natural stream. [para 64]

41. One of the cases cited by Newey J was the Court of Appeal decision of Baily & Co v Clark, Son & Morland [1902] 1 Ch 649. Newey J summarised it as follows:

In that case, the plaintiffs owned a mill which was situated on an artificial cut or channel from a natural river which ran for about a mile and a half before rejoining the river. As Stirling LJ commented (at 668), nothing was known as to the circumstances in which the watercourse was created:

“It has existed for hundreds of years, but we do not know who at the time of its construction were the owners of the properties which now belong to the plaintiffs and the defendants respectively, or indeed anything about the ownership at that time of any part of the land along the watercourse.”

The Court of Appeal concluded that the plaintiffs and other owners of property abutting on the watercourse were all entitled to use the water for reasonable purposes. Having noted that other adjoining owners had used water from the watercourse, Stirling LJ said (at 669):

“What ought the conclusion to be with regard to these acts of the riparian owners? It seems to me that they ought to be taken primâ facie to have been done in the exercise of a legal right rather than as having been done without any legal title. It ought therefore, I think, to be inferred that the owners of the lands abutting on this watercourse reserved to themselves at the time when the watercourse was constructed the right to a reasonable use of the water as it passed their lands, and that the plaintiffs are in like manner entitled to a similar right - a right to the use of the water for all reasonable purposes, and not merely for the purposes of their mill. In substance, over and above the special use of the water for the purposes of the mill, both the plaintiffs and the other adjoining owners are entitled to those rights to which the owners of lands adjoining a natural stream would be entitled inter se.”

42. Where the watercourse has been in existence for hundreds of years and nothing is known about the ownership at the time of its banks or the circumstances in which it was constructed the Court can infer that it was constructed on the basis that the riparian owners should have the same rights as if the watercourse had been natural.

43. In the light of this decision I am prepared to accept that the Claimants had the same rights over that part of the Upper Land Yeo within their curtilage as if it had been a natural watercourse. Mr Westaway classified those rights as quasi-easements.

Nature of Riparian Rights

44. In para 56 of the decision Newey J describes the rights in the following way:

It is Mrs Foster’s case that she enjoys riparian and milling rights. More specifically, she contends that, as the owner of a riparian property, she is entitled “to access to the water in contact with [her] frontage, and to have the water flow to [her] in its natural state in flow, quality and quantity so that [she] may take water for ordinary purposes in connection with [her] riparian tenement including the use of water power” (adopting words of Lord Templeman in Tate & Lyle Industries Ltd v Greater London Council [1983] 2 AC 509, at 531)

45. On this basis the Claimants are entitled to the water flow in its natural state in flow, quality and quantity. In order to succeed therefore the Claimants have to establish that that the natural state of flow at Sluice C is with the penning boards lowered. Mr Bates submitted that this was the position. Unsurprisingly Mr Westaway submitted that the natural state was with the penning boards raised. I unhesitatingly prefer the submissions of Mr Westaway. The penning boards only came into existence in the 1968 modifications. Furthermore, they have been raised for four months every year since 1989 and probably since 1968. In my view the natural state of the water flow is the water flow without the penning boards or with the penning boards raised.

46. On that basis the raising of the penning boards is not an interference (or intervention) with the Claimants’ quasi-easement and the Claimants claim for compensation must fail.

Other arguments.

47. Mr Westaway raised a number of other arguments as to why the Claimants’ claim must fail. In the light of my view on the nature of the Claimants’ rights it is unnecessary to decide them. In view of the fact that they raise quite difficult questions of law and the argument was necessarily somewhat curtailed by time constraints I prefer to express no concluded opinion on any of them. I will, however, summarise the arguments and add one or two preliminary comments of my own.

Estoppel

48. He asserted, in effect, that the Claimants were estopped from denying the EA the right to raise or lower the boards by virtue of the agreement in 1968 between BWC (the Claimants’ predecessor in title) and SRBC (the EA’s predecessor in title). He pointed out that SRA spent a significant sum in carrying out the modifications with the agreement of BWC.

49. He referred to two cases which he submitted supported his submission – Armstrong v Sheppard [1959] 2 QB 384 and Liggins v Inge 7 Bing 683.

50. To my mind there are potentially a number of difficulties with these submissions. First, as Mr Bates pointed out, the EA has no proprietary interest in Sluice C. It is by no means clear how far the doctrine of proprietary estoppel can apply in such a situation. Second it is equally not clear that the burden of the agreement would be binding on successors in title such as the Claimants. It has to be borne in mind that there is no reference to any right of access in the conveyances either to Dr and Mrs Miller or to the Claimants. Finally even if some form of proprietary estoppel were held to exist it does not follow that the discretionary remedy granted by the court would amount to a perpetual right to operate Sluice C.

Abandonment

51. Mr Westaway submitted that the long period of disuse (from the mid 1960’s to 2015) amounted to abandonment of the Claimants’ rights. Again, there are difficulties with this argument. First it is by no means clear that riparian rights can be abandoned. Mr Bates submitted that they could not be abandoned. Second it is very difficult to abandon an easement. Mere non use is not enough. It has to be coupled with an intention never to use the easement again. Third this is not a case of total abandonment but partial abandonment. Water has continued to flow through the Bypass Channel for the whole period. It must be even more difficult to establish partial abandonment of an easement.

Reasonableness

52. As already noted, Mr Bates did not assert that the EA’s conduct was unreasonable. I have held it was reasonable. Mr Westaway submits that that finding is a complete answer to the claim based on nuisance. In his submission unreasonable conduct on the part of the EA is a necessary element of the cause of action in nuisance. Mr Bates did not accept this. In his submission interference with the Claimants’ proprietary riparian rights was sufficient to constitute the tort however reasonable the conduct of the EA was held to be. He also referred me to the decision of Ramsey J in Manolete v Hastings [2013] EWHC 842 (TCC) at paras 21 – 27 as authority for the proposition that in a compensation claim it did not matter that the statutory body was acting reasonably. Indeed, they often would be. My very provisional view is that Mr Bates is correct on this point. However, it is a by no means straightforward area of law and I prefer to express no concluded opinion.

Conclusion

53. For the reasons set out above the Claimants have failed to establish an interference with their riparian rights and the claim to compensation fails.

Judge John Behrens

29 March 2019

ANNEX