[2017] UKSC 59

On appeal from: [2015] EWCA Civ 407

JUDGMENT

MT Højgaard A/S (Respondent) v E.ON Climate

& Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Limited and another (Appellants)

before

Lord Neuberger, President

Lord Mance

Lord Clarke

Lord Sumption

Lord Hodge

JUDGMENT GIVEN ON

3 August 2017

Heard on 20 June 2017

|

Appellants

John Marrin QC

Paul Buckingham

(Instructed by

Gowling WLG (UK) LLP)

|

|

Respondent

David

Streatfeild-James QC

Mark

Chennells

(Instructed by

Fenwick Elliott LLP)

|

LORD NEUBERGER: (with whom

Lord Mance, Lord Clarke, Lord Sumption and Lord Hodge agree)

The background

1.

These proceedings arise from the fact that the foundation structures of

two offshore wind farms at Robin Rigg in the Solway Firth, which were designed

and installed by MT Højgaard A/S (“MTH”), failed shortly after completion of

the project. The specific issue to be determined is whether MTH are liable for

this failure.

2.

As Jackson LJ said in the Court of Appeal, the resolution of that issue

turns on “how the court should construe the somewhat diffuse documents which

constituted, or were incorporated into, the ‘design and build’ contract in this

case”. Accordingly, I turn first to consider the relevant provisions of the

contractual documentation.

The relevant provisions of the Technical Requirements and

J101

3.

In May 2006, the appellants, two companies in the E.ON group (“E.ON”),

sent tender documents to various parties including MTH, who in due course

became the successful bidders. The tender documents included Employer’s Requirements,

Part I of which included the Technical Requirements (“the TR”).

4.

Section 1 of the TR set out the “General Description of Works and Scope

of Supply”. Part 1.6 set out the so-called Key Functional Requirements, which

included this:

“The Works, together with the

interfaces detailed in Section 8, shall be designed to withstand the full range

of operational and environmental conditions with minimal maintenance.

The Works elements shall be

designed for a minimum site specific ‘design life’ of twenty (20) years without

major retrofits or refurbishments; all elements shall be designed to operate

safely and reliably in the environmental conditions that exist on the site for

at least this lifetime.”

5.

Section 3 of the TR was concerned with the “Design Basis (Wind Turbine

Foundations)”. Part 3.1 was entitled “Introduction”, and it included the following

(divided into sub-paragraphs for convenience):

“(i) It is stressed that the

requirements contained in this section and the environmental conditions given

are the MINIMUM requirements of [E.ON] to be taken into account in the design.

(ii) It shall be the

responsibility of [MTH] to identify any areas where the works need to be

designed to any additional or more rigorous requirements or parameters.”

There were other references elsewhere to the stated

requirement being a minimum. Para 3.1.2 of the TR required MTH to submit a

detailed Foundation Design Basis document, which was required to contain, among

other things, a statement as to “the Contractor’s design choices, including,

but not limited to, … departures from, or aspects not covered by, standards, if

any”.

6.

Part 3.2 of the TR was headed “Design Principles”, and para 3.2.2 was

concerned with “General Design Conditions”, para 3.2.2.1 being directed to the

“Tender Stage Design”, and para 3.2.2.2 to the “Detailed Design Stage”. Para

3.2.2.2 is of central importance for present purposes, and, for convenience, I

shall treat it as divided into numbered sub-paragraphs. Para 3.2.2.2(i)

required MTH to prepare the detailed design of the foundations in accordance

with a document known as J101, using the “integrated analysis” method (which

was one of the four methods addressed in J101). Para 3.2.2.2(ii) went on to

state that:

“The design of the foundations

shall ensure a lifetime of 20 years in every aspect without planned

replacement. The choice of structure, materials, corrosion protection system

operation and inspection programme shall be made accordingly.”

7.

J101 was a reference to an international standard for the design of

offshore wind turbines published by Det Norske Veritas (“DNV”), an independent

classification and certification agency based in Norway. J101 included a

statement that its “objectives” included the provision of “an internationally

acceptable level of safety by defining minimum requirements for structures and

structural components”, as well as being “a contractual reference document”,

and a “guideline”. Section 2 of J101 contained design principles which were,

among other things, aimed at limiting the annual probability of failure to be

in the range of one in 10,000 to one in 100,000 - para C201. Section 7 of J101

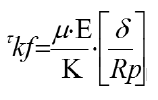

dealt with the design of steel structures, and para K104 provided:

“The design fatigue life for

structural components should be based on the specified service life of the

structure. If a service life is not specified, 20 years should be used.”

Section 9 of J101 dealt with the design and construction

of grouted connections. Part A included reference to shear keys, which, it was

explained, “can reduce the fatigue strength of the tubular members and of the

grout”. Part B of section 9 set out a number of equations applicable to such a

design, including one (“the Equation”) which showed how the interface shear

strength due to friction is to be calculated, namely:

Precisely what the Equation actually means need not be

spelled out. What is important for present purposes is that it was stated

beneath the Equation that δ should “be taken as 0.00037 Rp for rolled

steel surfaces” (Rp being the outer radius of the pile, and δ being the

height of surface irregularities).

8.

Para 3.2.3.2 of the TR required MTH’s design to accord with

“international and national rules, circulars, EU directives executive orders

and standards applying to the Site” and it went on to state that a defined

“hierarchy of standards shall apply”, as listed. Ignoring those standards which

were irrelevant or not in force, the first in the list was J101. Para 3.2.5

required the contractor to design and construct grouted connections in

accordance with J101. Para 3.2.6 stated that “[a]ll parts of the Works, except

wear parts and consumables, shall be designed for a minimum service life 20

years” (sic).

9.

Section 3b of the TR was headed “Design Basis for Offshore Substations

and Meteorological Mast”. Para 3b.5.1 stated:

“The design of the structures

addressed by this Design Basis shall ensure a lifetime of 20 years in every

aspect without planned replacement. The choice of structure, materials,

corrosion protection system operation and inspection programme shall be made

accordingly.”

Para 3b.5.6 provided that “[a]ll parts of the Works,

except wear parts and consumables shall be designed for a minimum service life

20 years.”

10.

Section 4 of the TR dealt with “Approvals and Certification”. Para 4.4.3

provided that MTH should obtain a Foundation Design Evaluation Conformity

Statement from the Certifying Authority within six months of the commencement

date.

11.

Section 10 of the TR covered “Structural Design and Fabrication” (Wind

Turbine Foundations), and para 10.1.1 required MTH to appoint “an accredited

Certifying Authority … to independently evaluate the adequacy of his foundation

design.” Para 10.5.1 was in these terms:

“The Contractor shall determine

whether to employ shear keys within the grouted connection. If shear keys are

used, the design and detailing shall take due account of their presence for

both strength and fatigue design to the satisfaction of the Certifying

Authority and the Engineer. If shear keys are to be omitted then the Contractor

shall demonstrate with test data that the grouted connection is capable of

transmitting axial loads at the grout/steel interface without dependence upon

flexural (normal) contact pressures, which may not always be present, to the

satisfaction of the Certifying Authority and the Engineer. Such demonstration

shall also account for joint performance under different temperature

conditions.”

12.

Para 10.24.9 of the TR stated that the “recorded potential difference

exceedance” was not so great as to “cause accelerated anode depletion to such

extent that the anode material provided is fully utilised before the end of the

structure operational 20 year life”.

13.

Having been selected as the contractor for the works, MTH duly set about

preparing its tender in accordance with Employer’s Requirements and J101. MTH’s

design provided for (i) monopiles with a diameter of just over four metres,

(ii) transition pieces about eight metres long, weighing approximately 120

tonnes, and (iii) grouted connections without shear keys. MTH explained at the

time that no shear keys were specified because, taking δ as 0.00037 Rp,

application of the Equation indicated that the grouted connections, as

designed, had more than sufficient axial capacity to take the axial load.

14.

After E.ON had accepted MTH’s tender, MTH duly commenced design work,

and in November 2006 it submitted a detailed Foundation Design Basis document,

as required by para 3.1.2 of the TR.

The relevant provisions of the contract

15.

On 20 December 2006 E.ON and MTH entered into a written contract (“the

Contract”) under which MTH agreed to design, fabricate and install the

foundations for the proposed turbines. Part C of the Contract contained a List

of Definitions. “Fit for Purpose” was defined as “fitness for purpose in

accordance with, and as can properly be inferred from, the Employer’s

Requirements”. “Employer’s Requirements” was stated to include the TR, which

were themselves attached as Part I of the Contract. And “Good Industry

Practice” meant “those standards, practices, methods and procedures conforming

to all Legal Requirements to be performed with the exercise of skill, diligence,

prudence and foresight that can ordinarily and reasonably be expected from a

fully skilled contractor who is engaged in a similar type of undertaking or

task in similar circumstances in a manner consistent with recognised

international standards”.

16.

Clause 2.1 of Part D of the Contract provided that any failure by the

Engineer or his Representative to spot defects or mistakes by the contractor

would not exempt the contractor from liability. Clause 5.3 of Part D stated

that in the event of inconsistencies, the order of precedence of the

contractual documents should be as follows:

(a)

the form of agreement;

(b)

the conditions of contact and the List of Definitions;

(c)

the commercial schedules and the schedule of prices, payment profile and

draft programme;

(d)

the Employer’s Requirements;

(e)

the annexes to the Employer’s Requirements;

(f)

volumes 2A, 2B and 3 of the contractor’s tender return.

17.

Clause 8.1 of Part D required MTH “in accordance with this Agreement,

[to] design, manufacture, test, deliver and install and complete the Works” in

accordance with a number of requirements, including

“(iv) in a professional manner

in accordance with modern commercial and engineering, design, project

management and supervisory principles and practices and in accordance with

internationally recognised standards and Good Industry Practice; …

(viii) so that the Works, when

completed, comply with the requirements of this Agreement …;

(ix) so that [MTH] shall

comply at all times with all Legal Requirements and the standards of Good

Industry Practice;

(x) so that each item of

Plant and the Works as a whole shall be free from defective workmanship and

materials and fit for its purpose as determined in accordance with the

Specification using Good Industry Practice; …

(xv) so that the design of the

Works and the Works when Completed by [MTH] shall be wholly in accordance with

this Agreement and shall satisfy any performance specifications or requirements

of the Employer as set out in this Agreement. …”

18.

Clause 30 of Part D of the Contract was headed “Defects after taking

over”. Clause 30.2 provided that MTH “shall be responsible for making good any

defect … or damage” arising from “defective materials, workmanship or design”,

“any breach by [MTH] of his obligations under this Agreement” or “Works not

being Fit for Purpose”, “which may appear or occur before or during the Defects

Liability Period”. That period was defined in clause 30.1 as being a period of

24 months from the date E.ON takes over the Works from MTH. Clause 30.3

required E.ON to give notice “forthwith” of any such defects to MTH. Clause

30.4 extended that Period in certain limited circumstances. Clause 30.10

required E.ON to produce a Defects Liability Certificate once the Defects

Liability Period has expired and MTH has satisfied all its obligations under

clause 30.

19.

Clause 33.9 of Part D of the Contract entitled MTH to apply, within 28

days of the issue of a Defects Liability Certificate, for a Final Certificate

of Payment, and to accompany the application with a final account; clause 33.10

provided for the consequential issue of a Final Certificate of Payment; and

clause 33.11 provided the Final Certificate of Payment is conclusive.

20.

Clause 42.3 of Part D of the Contract stated that:

“[E.ON] and [MTH] intend that

their respective rights, obligations and liabilities as provided for in this

Agreement shall alone govern their rights under this Agreement.

Accordingly, the remedies provided

under this Agreement in respect of or in consequence of:

(a) any breach of contract;

or

(b) any negligent act or

omission; or

(c) death or personal

injury; or

(d) loss or damage to any

property,

are, save in the case of …

Misconduct, to be to the exclusion of any other remedy that either may have

against the other under the law governing this Agreement or otherwise.”

Subsequent events

21.

MTH duly proceeded with the design and construction of the two wind

farms (“the Works”), and, on its instructions, Rambøll Danmark A/S supplied in

June 2007 a detailed design for the grouted connections, which did not include

shear keys. Pursuant to para 10.1.1 of the TR, MTH appointed DNV as the

Certifying Authority, and DNV evaluated and approved MTH’s foundation designs.

Pursuant to para 4.4.3 of the TR, DNV issued Foundation Design Evaluation

Conformity Statements for the various phases of the works. MTH began the

installation of foundations in the Solway Firth in December 2007, and completed

the Works in February 2009.

22.

During 2009 a serious problem came to light at Egmond aan Zee wind farm,

where the grouted connections did not have shear keys. Those connections

started to fail, and the transition pieces started to slip down the monopiles.

DNV carried out an internal review during late summer 2009, and discovered that

there was an error in the value given for δ in the note to the Equation

mentioned in para 7 above. It was wrong by a factor of about ten. This meant

that the axial capacity of the grouted connections in wind farm foundations at

various locations including Egmond aan Zee and Robin Rigg had been substantially

over-estimated.

23.

On 28 September 2009, DNV sent a letter to MTH and others in the

industry, alerting them to the situation (and DNV subsequently revised J101 to

correct the error). In April 2010 the grouted connections at Robin Rigg started

to fail, as they had done a year earlier at Egmond aan Zee, and the transition

pieces began to slip down the monopiles. Very sensibly E.ON and MTH deferred

any legal dispute and set about finding a practical solution to the problem. It

was agreed between the parties that E.ON would develop a scheme of remedial

works. Those remedial works were commenced in 2014.

24.

In order to ascertain who should bear the cost of the remedial works,

the parties embarked upon the present proceedings. In very summary terms, the

parties’ respective positions were as follows. MTH contended

that it had exercised reasonable skill and care, and had complied with all its

contractual obligations, and so should have no liability for the cost of the

remedial works. By contrast E.ON contended that MTH had been

negligent and also had been responsible for numerous breaches of contract, and

they claimed declarations to the effect that MTH was liable for the defective

grouted connections. The parties in due course agreed the

cost of the remedial works in the sum of €26.25m, leaving the court to decide

which of them should bear that cost.

25.

The case came before Edwards-Stuart J, and after an eight-day hearing in

November 2013, he gave judgment in April 2014 - [2014] EWHC 1088 (TCC). He

rejected the suggestion that MTH had been negligent, and he also rejected a

number of allegations of breach of contract made by E.ON. However, he found for

E.ON primarily on the ground that (i) clause 8.1(x) of the contract required

the foundations to be fit for purpose, (ii) fitness for purpose was to be determined

by reference to the TR, and (iii) para 3.2.2.2(ii) (and also para 3b.5.1) of

the TR required the foundations to be designed so that they would have a

lifetime of 20 years. He also held that this conclusion was also supported by

clauses 8.1(viii) and (xv).

26.

MTH appealed to the Court of Appeal, and after a two-day hearing in

February 2015, they handed down their decision two months later, allowing the

appeal for reasons given by Jackson LJ, with whom Patten and Underhill LJJ

agreed - [2015] EWCA Civ 407. Jackson LJ accepted that, if one was confined to

the TR, para 3.2.2.2(ii) appeared to be “a warranty [on the part of MTH] that

the foundations will function for 20 years”. However, in the light of the

provisions of the Contract, he said that there was “an inconsistency between

[paras 3.2.2.2(ii) and 3b.5.1 of the TR] on the one hand and all the other

contractual provisions on the other hand”, and that the other contractual

provisions should prevail. He went on to describe paras 3.2.2.2(ii) and 3b.5.1

of the TR as “too slender a thread upon which to hang a finding that MTH gave a

warranty of 20 years life for the foundations”.

The meaning of para 3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR

27.

The central question on this appeal is whether, in the light of para

3.2.2.2(ii) (and para 3b.5.1) of the TR, which refer to ensuring a life for the

foundations (and the Works) of 20 years, MTH was in breach of contract, despite

the fact that it used due care and professional skill, adhered to good industry

practice, and complied with J101. Before turning to that issue, however, it is

appropriate to deal with an argument raised by Mr Streatfeild-James QC in the

course of his excellent submissions on behalf of MTH. He suggested that it was

unlikely that the parties could have intended that there should be what Jackson

LJ characterised as “a warranty that the foundations will function for 20

years”, in the light of those parts of clauses 30, 33 and 42 of the Contract

set out in paras 18 to 20 above. In summary, he argued that (i) the effect of

clause 30 was that, subject to some relatively limited exceptions in clause

30.4, MTH was obliged to rectify any defect in the Works which occurred within

24 months of the Works being handed over, (ii) the effect of clause 42.3 was

that any claim by E.ON in respect of a defect appearing thereafter was barred,

and (iii) the notion that there was no room for claims outside the 24-month

period was reinforced by clauses 33.9 and 33.10.

28.

In my opinion, there is no answer to that analysis so far as it is

directed to the effect of clauses 30, 33 and 42 of the Contract. Clause 42.3

makes it clear that the provisions of clause 30 (and any other contractual term

which provides for remedies after the Works have been handed over to E.ON) are

intended to operate as an exclusive regime. And that conclusion appears to me

to be supported by the terms of clause 33.9 and 33.10, because they tie in very

well with the notion that there should be no claims after the Final

Certificate, which is to be issued very shortly after the 24-month period.

29.

Accordingly, if, as E.ON argue, para 3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR amounts to a

warranty that the foundations will last for 20 years, there would be a tension

between that provision and clauses 30, 33 and 42 of the Contract. However, I do

not consider that the tension would be so problematic as to undermine the

conclusion that para 3.2.2.2(ii) amounted to warranties as described by Jackson

LJ. In the light of the normal give and take of negotiations, and the complex,

diffuse and multi-authored nature of this contract, it is by no means

improbable that MTH could have agreed to a 20-year warranty provided that it

could have the benefit of a two-year limitation period, save where misconduct

was involved. It would simply mean that the rights given to E.ON by paras 3.2.2.2(ii)

were significantly less valuable than at first sight they may appear, because

any claim based on an alleged failure in the foundations which only became

apparent more than two years after the handover of the Works would normally be

barred by clause 42.3. In this case, of course, there is no problem, because

the foundations failed well within the 24-month period.

30.

However, in my view, although it would therefore be possible to give

effect to para 3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR as a 20-year warranty as described by

Jackson LJ, the points canvassed in paras 27 to 29 above justify reconsidering

the effect of para 3.2.2.2(ii). It appears to me that there is a powerful case

for saying that, rather than warranting that the foundations would have a

lifetime of 20 years, para 3.2.2.2(ii) amounted to an agreement that the design

of the foundations was such that they would have a lifetime of 20 years. In

other words, read together with clauses 30 and 42.3 of the Contract, para

3.2.2.2(ii) did not guarantee that the foundations would last 20 years without

replacement, but that they had been designed to last for 20 years without

replacement. That interpretation explains the reference in para 3.2.2.2(ii) to

design, and it obviates any tension between the terms of para 3.2.2.2(ii) and

the terms of clauses 30 and 42.3. Rather than the 20-year warranty being cut

off after 24 months, E.ON had 24 months to discover that the foundations were

not, in fact, designed to last for 20 years. On the basis of that

interpretation, E.ON’s ability to invoke its rights under para 3.2.2.2(ii)

would not depend on E.ON appreciating that the foundations were failing (within

24 months of handover), but on E.ON appreciating (within 24 months of handover)

that the design of the foundations was such that they will not last for 20

years.

31.

That, of course, raises the question as to what, on that reading, was

precisely meant by “ensur[ing] a lifetime of 20 years”, given that the forces

of nature, especially at sea, are such that a lifetime of 20 years, or any

other period, could never in practice be guaranteed. The answer is to be found

in J101. As explained in para 7 above, J101 requires the annual probability of

failure to be in the range of one in 10,000 to one in 100,000, and specifically

provides that, if a service life is not specified in a contract “20 years

should be used”, which ties in with the proposition, agreed between the

parties, that an offshore wind farm is typically designed for a 20-year

lifetime. This aspect could be expanded on substantially by reference to the

detailed terms, requirements and recommendations of J101. In particular, one of

the two so-called “Limit States” in terms of loadbearing requirements, FLS, is

calculated by reference to the design life of the structure in question: hence para

C201 of section 2 and para K104 of section 7 referred to in para 7 above.

However, the simple point is that J101, while concerned with making

recommendations and requirements linked to the intended life of a structure to

which it applies, makes it clear that there is a risk, which it quantifies, of

that life being shortened. That risk is, in my view, the risk which should be

treated as incorporated in para 3.2.2.2(ii) - if it is indeed concerned with

the designed life of the Works.

32.

It is unnecessary to decide whether para 3.2.2.2(ii) is a warranty that

the foundations will have a lifetime of 20 years or a contractual term that the

foundations will be designed to have such a lifetime. The former meaning has

been taken as correct by the parties and by the courts below, but, for the

reasons given in paras 28 to 31 above, I am currently inclined to favour the

latter meaning. On the other hand, as the TR were produced and, to an extent,

acted on before the Contract was agreed, it may be questionable whether it

would be right to interpret the TR by reference to clauses of the Contract.

However, it is clear that, if para 3.2.2.2(ii) is an effective term of the

Contract, it was breached by MTH whichever meaning it has, and therefore the

issue need not be resolved.

33.

I turn then to the central issue on this appeal.

The enforceability of para 3.2.2.2(ii) according to its

terms: introductory

34.

E.ON’s case is that para 3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR is incorporated into the

Contract, because (i) clause 8.1(x) of the Contract required the Works to be

fit for purpose, (ii) Part C of the Contract equated fitness for purpose with

compliance with the Employer’s Requirements, (iii) Part C also defined

Employer’s Requirements as including the contents of the TR, and (iv) the TR included

para 3.2.2.2(ii), which specifically refers to the foundations having a life of

20 years. On that basis, E.ON argues that para 3.2.2.2(ii) was clearly

infringed, and, as it was a term of the Contract, it must follow that MTH is,

as Edwards-Stuart J held, liable for breach of contract.

35.

By contrast, MTH supports the reasoning of Jackson LJ, and contends that

it is clear that the Contract stipulated that the Works must be constructed in

accordance with the requirements of J101 (and with appropriate care), and it is

unconvincing to suggest that a provision such as para 3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR

renders MTH liable for faulty construction, given that the Works were

constructed fully in accordance with J101 (and with appropriate care). MTH

contends that the references to a 20-year life in various provisions of the TR,

including para 3.2.2.2(ii), ultimately do no more than reflect the fact that,

as envisaged by J101, Part 1.6 of the TR specifies a “design life” for the

Works. MTH also adopts Jackson LJ’s description of the contractual

documentation as being “of multiple authorship [and]

contain[ing] much loose wording”, and that it includes many “ambiguities,

infelicities and inconsistencies” (quoting Lord Collins in In re Sigma

Finance Corp (in administrative receivership) [2010] 1 All ER 571, para

35). More specifically, MTH makes the points that the TR are “in their nature

technical rather than legal”, and that if the parties had intended MTH to

warrant that the foundations would have a 20-year lifetime, or that they would

be designed to have a 20-year life, a term to that effect would have been

included in plain terms, probably as a Key Functional Requirement in para 1.6

of the TR.

36.

As already explained, it appears to me that, if one considers the

natural meaning of para 3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR, it involved MTH warranting

either that the foundations would have a lifetime of 20 years (as Jackson LJ

accepted) or agreeing that the design of the foundations would be such as to

give them a lifetime of 20 years. As Mr Streatfeild-James realistically

accepted, the combination of the terms of clause 8.1(x) of the Contract and the

definitions of “Employer’s Requirements” and “Fit for Purpose” result in the

provisions of the TR being effectively incorporated into the Contract -

unsurprisingly as they are included in the contractual documentation as Part I.

In those circumstances, I consider that there are only two arguments open to

MTH as to why the paragraph should not be given its natural effect (and while

they are separate arguments, they can fairly be said to be mutually

reinforcing). The first argument is that such an interpretation results in an

obligation which is inconsistent with MTH’s obligation to construct the Works

in accordance with J101. The second argument is that para 3.2.2.2(ii) is simply

too slender a thread on which to hang such an important and potentially onerous

obligation.

The enforceability of para 3.2.2.2(ii) according to its

terms: inconsistency with J101

37.

There have been a number of cases where courts have been called on to

consider a contract which includes two terms, one requiring the contractor to

provide an article which is produced in accordance with a specified design, the

other requiring the article to satisfy specified performance criteria; and where

those criteria cannot be achieved by complying with the design. The

reconciliation of the terms, and the determination of their combined effect

must, of course, be decided by reference to ordinary principles of contractual

interpretation (as recently discussed in Wood v Capita Insurance Services

Ltd [2017] 2 WLR 1095, paras 8 to 15 and the cases cited there), and

therefore by reference to the provisions of the particular contract and its

commercial context. However, it is worth considering some of the cases where

such an issue has been discussed.

38.

Thorn v The Mayor and Commonalty of London (1876) 1 App Cas 120

has been treated as the first decision on this point (including in the

judgments discussed in paras 39 to 43 below), although it seems to me to be

only of indirect relevance. The contractor successfully tendered for work

involving the replacement of the existing Blackfriars Bridge pursuant to an

employer’s invitation, which stated that the work was to be carried out

pursuant to a specification. The specification included wrought iron caissons

which were to form the foundations of the piers “as shewn on [certain]

drawings” (p 121). It subsequently turned out that the caissons as designed

“would not answer to their purpose, and the plan of the work was altered”,

causing consequential expense and delay to the contractor (p 122). The

contractor’s claim was based on the contention that the employer had impliedly

warranted that the bridge could be built according to the specification. The

unanimous rejection of the existence of such a warranty by the House of Lords

does not directly relate to the issue in this case. However, it is worth noting

that, as reconstruction of the bridge had been completed, the employer was not

responsible for the contractor’s losses and expenses flowing from the defective

specification (at least on the basis of an implied warranty). Rather more to

the point, the speeches of Lord Chelmsford (at pp 132 to 133) and Lord O’Hagan

(at p 138) strongly indicate that a contractor who bids on the basis of a

defective specification provided by the employer only has himself to blame if

he does not check their practicality and they turn out to be defective.

39.

The Hydraulic Engineering Co Ltd v Spencer and Sons (1886) 2 TLR

554 appears to me to be more directly in point. In that case, the defendants

contracted to make and deliver to the plaintiffs 15 cast iron cylinders. The

contract provided that the cylinders would be cast according to specifications

and plans provided by the plaintiffs, and also that the cylinders would be able

to stand a pressure of 25 cwt per square inch. The Court of Appeal, upholding

Coleridge CJ, rejected the defendants’ contention that, because “the flaw was

the inevitable result of the plan upon which the plaintiffs ordered them to do

the work the defendants could not be held liable for a defect caused by that

plan” (to quote from the report of counsel’s argument). Lindley LJ said that

“it was manifest that the defendants thought that they could cast the cylinders

on [the] pattern [sent by the plaintiffs] without defects”. Although he

accepted that “the defect was unavoidable”, he said that “[t]here was no doubt

that it was a defect” and “the [defendants] were therefore liable”. Lord Esher

MR and Lopes LJ agreed.

40.

A similar view was taken in Scotland by the Inner House in A M

Gillespie & Co v John Howden & Co (1885) 22 SLR 527, where a

customer ordered a ship from shipbuilders pursuant to a contract which required

the ship “to carry 1,800 tons deadweight”, and which also required the ship to

be built according to a model approved by the customer. The ship as built was

unable to carry 1,800 tons deadweight, and the shipbuilders argued that they

should not be liable for damages because it would have been impossible to

construct a ship capable of carrying 1,800 tons according to the model approved

by the customer. Upholding the Sheriff-Substitute, Lord Rutherfurd-Clark (with

whom Lords Craighill and Young agreed) said at p 528 that “this [was] no

defence”, as “[t]he fact remains that the [shipbuilders] undertook a contract

which they could not fulfil and they are consequently liable in damages for the

breach”.

41.

The issue has also come up in the courts of Canada. In The Steel

Company of Canada Ltd v Willand Management Ltd [1966] SCR 746, the

respondents were claiming for repair work to three defective roofs on buildings

which they had constructed for the appellants. The respondents argued that the

defects were not their fault, as they had constructed the buildings under a

contract which required them to comply with the requirements of the appellants,

and the defects resulted from defects in those requirements. Reversing the

Ontario Court of Appeal, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected this argument on

the ground that the contract also contained a term that the respondent

guaranteed that all work would remain weather tight and that all material and

workmanship would be first class and without defect. In the course of giving

the judgment of the court, Ritchie J at p 751 rejected the respondents’

contention, which was supported by a decision of the courts of New York, that

they “guaranteed only that, as to the work done by it, the roof would be

weather-tight in so far as the plans and specifications with which it had to

comply would allow”, and at pp 753 to 754 approved a statement in the then

current (8th) edition of Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts, p 147, to

this effect:

“generally the express obligation

to construct a work capable of carrying out the duty in question overrides the

obligation to comply with the plans and specifications, and the contractor will

be liable for the failure of the work notwithstanding that it is carried out in

accordance with the plans and specification. Nor will he be entitled to extra

payment for amending the work so that it will perform the stipulated duty.”

42.

The reasoning of the Canadian Supreme Court was fairly recently applied

by the Court of Appeal for British Columbia in Greater Vancouver Water

District v North American Pipe & Steel Ltd 2012 BCCA 337, where a

“clear and unambiguous” provision whereby a supplier “warrant[ed] and

guarantee[d]” that the supplied goods were “free from all defects … arising

from faulty design” was held to apply in full, notwithstanding the immediately

preceding warranty by the supplier that the goods would “conform to all

applicable specifications”, and that those specifications were unsatisfactory

and led to the defect complained of.

43.

The law on the topic was well summarised by Lord Wright in Cammell

Laird and Co Ltd v The Manganese Bronze and Brass Co Ltd [1934] AC 402,

425, where he said that “[i]t has been laid down that where a manufacturer or

builder undertakes to produce a finished result according to a design or plan,

he may be still bound by his bargain even though he can show an unanticipated

difficulty or even impossibility in achieving the result desired with the plans

or specification”. After referring to Thorn as being “[s]uch a case”, he

mentioned Gillespie v Howden (1885) 12 R 800, where “the Court of Session

held it was no defence to a shipbuilder who had contracted to build a ship of a

certain design and of a certain carrying capacity, that it was impossible with

the approved design to achieve the agreed capacity: the shipbuilder had to

answer in damages”. Lord Wright then went on to explain that “[t]hough this is

the general principle of law, its application in respect of any particular

contract must vary with the terms and circumstances of that contract”.

44.

Where a contract contains terms which require an item (i) which is to be

produced in accordance with a prescribed design, and (ii) which, when provided,

will comply with prescribed criteria, and literal conformity with the

prescribed design will inevitably result in the product falling short of one or

more of the prescribed criteria, it by no means follows that the two terms are

mutually inconsistent. That may be the right analysis in some cases (and it

appears pretty clear that it was the view of the Inner House in relation to the

contract in A M Gillespie). However, in many contracts, the proper

analysis may well be that the contractor has to improve on any aspects of the

prescribed design which would otherwise lead to the product falling short of

the prescribed criteria, and in other contracts, the correct view could be that

the requirements of the prescribed criteria only apply to aspects of the design

which are not prescribed. While each case must turn on its own facts, the

message from decisions and observations of judges in the United Kingdom and

Canada is that the courts are generally inclined to give full effect to the

requirement that the item as produced complies with the prescribed criteria, on

the basis that, even if the customer or employer has specified or approved the

design, it is the contractor who can be expected to take the risk if he agreed

to work to a design which would render the item incapable of meeting the

criteria to which he has agreed.

45.

Turning to the centrally relevant contractual provisions in the instant

case, it seems to me that MTH’s case, namely that the obligation which appears

to be imposed by para 3.2.2.2(ii) is inconsistent with the obligation imposed

by para 3.2.2.2(i) to comply with J101, faces an insurmountable difficulty. The

opening provision of Section 3, para 3.1, (i) “stresse[s]” that “the

requirements contained in this section … are the MINIMUM requirements of [E.ON]

to be taken into account in the design”, and (ii) goes on to provide that it is

“the responsibility of [MTH] to identify any areas where the works need to be

designed to any additional or more rigorous requirements or parameters”. In

those circumstances, in my judgment, where two provisions of Section 3 impose

different or inconsistent standards or requirements, rather than concluding

that they are inconsistent, the correct analysis by virtue of para 3.1(i) is

that the more rigorous or demanding of the two standards or requirements must

prevail, as the less rigorous can properly be treated as a minimum requirement.

Further, if there is an inconsistency between a design requirement and the

required criteria, it appears to me that the effect of para 3.1(ii) would be to

make it clear that, although it may have complied with the design requirement,

MTH would be liable for the failure to comply with the required criteria, as it

was MTH’s duty to identify the need to improve on the design accordingly.

46.

As to the facts of the present case, para 3.2.2.2(i) could indeed be

said to require that (as recorded in the note to the Equation in J101) δ should

“be taken as 0.00037 Rp for rolled steel surfaces”, and, as explained above,

this was a mistake, in that it substantially over-estimated the connection

strength. However, given the terms of para 3.1(i), this figure for δ was a

“MINIMUM requirement”, and, if para 3.2.2.2(ii) was to be complied with, the

value of δ stipulated by J101 had to be decreased (as it happens by a

factor of around ten). Furthermore, para 3.1(ii) makes it clear that MTH should

have identified that there was a need for a “more rigorous” requirement than

δ being “taken as 0.00037 Rp” to ensure that the design was satisfactory,

or at least complied with para 3.2.2.2(ii).

47.

It is right to add that, even without para 3.1(i) and (ii), I would have

reached the same conclusion. Even in the absence of those paragraphs, it cannot

have been envisaged that MTH would be in breach of its obligations under para

3.2.2.2(i) if it designed the foundations on the basis of δ being less

than 0.00037 Rp for rolled steel surfaces. Accordingly, at least in relation to

the Equation, it represented a minimum standard even in the absence of paras

3.1(i) and (ii), and therefore there would have been no inconsistency between

para 3.2.2.2(i) and 3.2.2.2(ii). I also draw assistance in reaching that conclusion

from the cases discussed in paras 38 to 43 above. The notion that the

Contractor might be expected to depart from the stipulations of J101, where

appropriate, is also supported by para 3.1.2 of the TR, which specifically

envisages that the Contractor’s Foundation Design Basis document may include

“departures from … standards”, and J101 is expressly treated as a “standard” in

para 3.2.3.2. In addition, given that satisfaction of the Equation is required

to justify the absence of shear keys, E.ON’s contention is assisted by the

terms of para 10.5.1, which starts by stating that MTH “shall determine whether

to employ shear keys within the grouted connection”; had shear keys been

provided, the problems which arose would, it appears, have been averted.

The enforceability of para 3.2.2.2(ii) according to its

terms: too slender a thread

48.

MTH relies on a number of factors to support the contention that para

3.2.2.2(ii) of the TR is too weak a basis on which to rest a contention that it

had a liability to warrant that the foundations would survive for 20 years or

would be designed so as to achieve 20 years of lifetime. First, it is said that

the diffuse and unsatisfactorily drafted nature of the contractual

arrangements, with their ambiguities and inconsistencies, should be “recognised

and taken into account”. The contractual arrangements are certainly long,

diffuse and multi-authored with much in the way of detailed description in the

TR, and “belt and braces” provisions both in the TR and the Contract. However,

that does not alter the fact that the court has to do its best to interpret the

contractual arrangements by reference to normal principles. As Lord Bridge of

Harwich said, giving the judgment of the Privy Council in Mitsui

Construction Co Ltd v Attorney General of Hong Kong (1986) 33 BLR 7, 14,

“inelegant and clumsy” drafting of “a badly drafted contract” is not a “reason

to depart from the fundamental rule of construction of contractual documents

that the intention of the parties must be ascertained from the language that

they have used interpreted in the light of the relevant factual situation in

which the contract was made”, although he added that “the poorer the quality of

the drafting, the less willing any court should be to be driven by semantic niceties

to attribute to the parties an improbable and unbusinesslike intention”. In

this case, para 3.2.2.2(ii) is clear in its terms in that it appears to impose

a duty on MTH which involves the foundations having a lifetime of 20 years

(although, as discussed in paras 27 to 32, there is room for argument as to its

precise effect). I do not see why that can be said to be an “improbable [or]

unbusinesslike” interpretation, especially as it is the natural meaning of the

words used and is unsurprising in the light of the references in the TR to the

design life of the Works being 20 years, and the stipulation that the

requirements of the TR are “minimum”.

49.

Secondly, MTH argues that it is surprising that such an onerous

obligation is found only in a part of a paragraph of the TR, essentially a

technical document, rather than spelled out in the Contract. Given that it is

clear from the terms of the Contract that the provisions of the TR are intended

to be of contractual effect, I am not impressed with that point.

50.

Thirdly, MTH suggests that, given the other obligations with regard to

design, manufacture, testing, delivery, installation and completion expressly

included, or impliedly incorporated, in clause 8.1 of the Contract, it is

unlikely that an additional further and onerous obligation was intended to have

been included in the TR. The trouble with that argument is that it involves

saying that para 3.2.2.2(ii) adds nothing to other provisions of the TR or the

contract. I accept that redundancy is not normally a powerful reason for

declining to give a contractual provision its natural meaning especially in a

diffuse and multi-authored contract (see In re Lehman Bros International

(Europe) (in administration) (No 4) [2017] 2 WLR 1497, para 67). However,

it is very different, and much more difficult, to argue that a contractual

provision should not be given its natural meaning, and should instead be given

no meaning or a meaning which renders it redundant.

51.

Fourthly, MTH argues that, if the parties had intended a warranty or

term such as is contended for by E.ON, it would not have been “tucked away” in

para 3.2.2.2 of the TR, but would, for instance, have been a Key Functional

Requirement in Section 1.6 of the TR. Section 1.6 is concerned with general provisions

about the two proposed wind farms, and there is no reference in it to any

specific component, in particular the foundations. In any event, as mentioned

in para 4 above, the Key Functional Requirements include a requirement “for a

minimum site specific ‘design life’ of twenty (20) years without major

retrofits or refurbishments”, and there is no definition of that expression.

Jackson LJ said below, in para 91, “If a structure has a design life of 20

years, that does not mean that inevitably it will function for 20 years,

although it probably will.” Assuming (without deciding) that that is correct,

it seems to me that there is a powerful case for saying that, given a Key

Functional Requirement is that there is a minimum 20-year design life, it is

scarcely surprising that a provision dealing with the “General Design

Conditions” at the “Detailed Design Stage” includes a provision which has the

effect for which E.ON contends in this case.

52.

Fifthly, MTH contends that the TR are concerned in a number of places (eg

paras 1.6, 3.2.6 and 3b.5.6) with emphasising that the “design life” of the

Works or various components of the Works should be 20 years, which does not

carry with it a warranty that the Works, or foundations, will last for 20 years

or that they will be designed to last for 20 years, and so it is unlikely that

para 3.2.2.2(ii) was concerned with imposing a greater obligation on MTH. The

points I have already made at the end of para 49 and the end of para 50 above

appear to me to answer this contention.

53.

Sixthly, MTH points out that para 3.2.2.2(ii) was concerned with planned

maintenance and should not be given the sort of broad effect which E.ON’s case

involves. It appears to me that the reference to planned maintenance at the end

of the first sentence of para 3.2.2.2(ii) emphasises that the design of the

foundations should not simply be such as to last for 20 years, but should be

able to do so without the need for planned maintenance.

Conclusion

54.

In these circumstances, I would allow E.ON’s appeal and restore the

order made at first instance by Edwards-Stuart J.