Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

First-tier Tribunal (Tax)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> First-tier Tribunal (Tax) >> Mojarad & Anorr v Revenue And Customs (VAT - personal liability notices - dry cleaners - average ticket price) [2025] UKFTT 598 (TC) (29 May 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2025/TC09538.html

Cite as: [2025] UKFTT 598 (TC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation: [2025] UKFTT 598 (TC)

Case Number: TC09538

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL

TAX CHAMBER

Taylor House, London

Appeal reference: TC/2019/9354

TC/2019/9357

VAT - personal liability notices - dry cleaners - average ticket price - appeal dismissed

Heard on: 30 and 31 January 2025

Judgment date: 29 May 2025

Before

TRIBUNAL JUDGE ROSA PETTIFER

MS GILL HUNTER

Between

HAMID MOJARAD (1)

DAVID MOJARAD (2)

Appellants

and

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HIS MAJESTY'S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS

Respondents

Representation:

For the Appellants: Mr Dhiren Doshi of Doshi Accountants

For the Respondents: Mr Paul Marks litigator of HM Revenue and Customs' Solicitor's Office

DECISION

Introduction

1. Paradise Dry Cleaners Limited (the Company) was incorporated on 25 May 2004. The Appellants were directors of the Company. The Company traded as a dry-cleaning business.

2. HMRC issued the Company with:

(1) A VAT assessment on 17 February 2017 for the under-declaration of £102,170 of output tax for the periods 08/09 to 05/16 pursuant to s73 Value Added Tax Act 1994 (the Original Company Assessment). On 13 November 2017 HMRC varied the assessment amount to £46,292 (the Company Assessment); and

(2) An inaccuracy penalty on £53,639.16 on 23 May 2017 pursuant to Schedule 24 Finance Act 2007 (Schedule 24) on the basis that the under-declaration had been deliberate (the Original Company Penalty). HMRC amended this penalty on 19 March 2019 to £24,291 to reflect the reduction in the Company Assessment (the Company Penalty).

3. HMRC issued a Personal Liability Notice to each of the Appellants on 19 March 2019 for £12,145.50 pursuant to paragraph 19 Schedule 24 on the basis that the inaccuracies were attributable in equal part to each of the Appellants (the PLNs).

4. The Company Assessment, the Company Penalty and the PLNs relate to the Company's VAT returns from 08/09 until 05/16 ie 1 June 2009 until 31 May 2016 (the Relevant Returns).

5. For the reasons set out below the appeal is dismissed.

preliminary points

Documents and evidence

6. For the hearing we were provided with an updated hearing bundle of 372 pages and an authorities bundle of 323 pages. Both Mr David Mojarad and Officer James Ellis provided witness statements and were cross examined.

Parties' submissions

7. We are grateful to Mr Marks and Mr Doshi for their skeleton arguments, submissions, and willingness to engage with our questions and to the witnesses for their evidence. We set out below our summary of those submissions on the law and the facts. The parties should, however, be assured that when preparing this decision, the terms of the skeletons were reread and our notes of the hearing reviewed. Because we do not deal specifically with any point it does not mean that it was not considered in the round when reaching our decision.

Late appeal

8. It was common ground that the Appellants' appeals were late. It was also common ground that the Appellants had mistakenly understood that the PLNs were under appeal following the creditor's meeting on 20 March 2019 (the day after the PLNs were issued). However, in the circumstances the Appellants' mistake was reasonable. Further, that once the Appellants understood that the PLNs were not in fact under appeal they had acted promptly. Consequently, HMRC did not object to the lateness of the appeals. In these circumstances, we grant permission for these late appeals to be brought.

Jurisdiction and burden of proof

9. The parties' position before us was that the Company Assessment and the Company Penalty themselves cannot be challenged in these appeals: that is correct because these appeals are against the PLNs. However, the parties agreed that aspects of the Company Assessment and the Company Penalty can be considered in an appeal against the PLNs.

10. HMRC's position on burden of proof, with which Mr Doshi agreed, was:

(1) HMRC bore the burden of proof as to the conditions for making the Company Assessment.

(2) The Appellants bore the burden of proof to show that the Company Assessment was incorrect.

(3) HMRC bore the burden of proof as to the Company Penalty.

(4) HMRC bore the burden of proof as to the PLNs.

The parties' approach was that we only needed to consider those aspects of the Company Assessment and Company Penalty that the Appellants specifically challenged. We agree as these are appeals against the PLNs. We note also that the above does not address who bears the burden of proof in relation to the defence provided by paragraph 18(3) Schedule 24. Although for the reasons set out below that does not matter

11. The standard of proof is on the balance of probabilities.

the issues to be determined

12. The issues to be determined in this appeal are:

(1) Whether the quantum of the PLNs should be reduced because the quantum of Company Assessment was too high.

(2) Whether the Company and the Appellants' behaviour was deliberate, reckless or careless.

(3) Whether the Company is entitled to rely on the defence provided by paragraph 18(3) Schedule 24 with the consequence that if the Company Penalty falls away so do the PLNs.

(4) Whether the quantum of the PLNs should be reduced because the Company Penalty was too high - further reduction should have been given for the quality of the Company's disclosure.

13. During the hearing Mr Doshi confirmed that that the Appellants were no longer challenging the PLNs on the ground that they were issued out of time.

the law

The legislation

14. Section 97 Finance Act 2007 provides:

(1) Schedule 24 contains provisions imposing penalties on taxpayers who

(a) make errors in certain documents sent to HMRC...

15. Paragraph 1 Schedule 24 states:

(1) A penalty is payable by a person (P) where

(a) P gives HMRC a document of a kind listed in the Table below, and

(b) Conditions 1 and 2 are satisfied.

(2) Condition 1 is that the document contains an inaccuracy which amounts to, or leads to

(a) an understatement of a liability to tax...

(3) Condition 2 is that the inaccuracy was careless (within the meaning of paragraph 3) or deliberate on P's part.

16. A VAT return is included in the documents listed in the Table below paragraph 1 Schedule 24.

17. Paragraph 3 Schedule 24 is headed "degrees of culpability" and sub-paragraph 1 reads:

For the purposes of a penalty under paragraph 1, an inaccuracy in a document given by P to HMRC is

(a) 'careless' if the inaccuracy is due to failure by P to take reasonable care,

(b) 'deliberate but not concealed' if the inaccuracy is deliberate on P's part but P does not make arrangements to conceal it, and

(c) 'deliberate and concealed' if the inaccuracy is deliberate on P's part and P makes arrangements to conceal it (for example, by submitting false evidence in support of an inaccurate figure)."

18. Paragraphs 4 and 4A(1)(a) Schedule 24 relevantly provide that penalties are: 30% of the "potential lost revenue" (PLR) for careless action; 70% of the PLR for deliberate but not concealed action; and 100% of the PLR where the action is both deliberate and concealed.

19. Paragraph 5 Schedule 24 defines the PLR as "the additional amount due or payable in respect of tax as a result of correcting the inaccuracy or assessment".

20. Paragraph 10 Schedule 24 provides for reductions in penalties under the relevant provisions of Schedule 24 based on the quality of disclosure given by the person liable to the penalty. However, that paragraph also provides that for a deliberate but not concealed inaccuracy the minimum penalty is 35% of the PLR.

21. Paragraph 9(1) Schedule 24 provides a person "discloses the matter" by (in summary):

(1) telling HMRC about it;

(2) giving HMRC reasonable help in quantifying the inaccuracy; and

(3) allowing HMRC access to records to ensure the inaccuracy is fully corrected.

Paragraph 9(2) Schedule 24 tells us that:

Disclosure—

(a) is "unprompted" if made at a time when the person making it has no reason to believe that HMRC have discovered or are about to discover the inaccuracy, the supply of false information or withholding of information, or the under-assessment], and

(b) otherwise, is "prompted".

22. Paragraph 19(1) Schedule 24 provides:

Where a penalty under paragraph 1 is payable by a company for a deliberate inaccuracy which was attributable to an officer of the company, the officer is liable to pay such portion of the penalty (which may be 100%) as HMRC may specify by written notice to the officer.

23. Paragraph 18 Schedule 24 provides in relevant part:

(1) P is liable under paragraph 1(1)(a) where a document which contains a careless inaccuracy (within the meaning of paragraph 3) is given to HMRC on P's behalf.

.......

(3) Despite sub-paragraphs (1) and (2), P is not liable to a penalty under paragraph 1 or 2 in respect of anything done or omitted by P's agent where P satisfies HMRC that P took reasonable care to avoid inaccuracy (in relation to paragraph 1) or unreasonable failure (in relation to paragraph 2).

The meaning of deliberate

24. There is no statutory definition of deliberate for the purposes of Schedule 24. The parties' common position was that the meaning of "deliberate" to be applied in the Appellants' case should follow the principles established by Tooth v HMRC [2021] UKSC 17. In that case at [43], in the context of the Taxes Management Act 1970 (TMA), the Supreme Court said:

Deliberate is an adjective which attaches a requirement of intentionality to the whole of that which it describes, namely 'inaccuracy'.

The Supreme Court added at [47] (referring to the relevant section of the TMA):

...for there to be a deliberate inaccuracy in a document within the meaning of section 118(7) there will have to be demonstrated an intention to mislead the Revenue on the part of the taxpayer as to the truth of the relevant statement...

the facts

Background and correspondence

26. The Company was incorporated on 25 May 2004 with company registration number 05137138. It went into liquidation on 20 March 2019 was dissolved on 8 July 2024.

27. The Company was registered for VAT on or around 24 September 2004.

28. The Company operated from 58 Parkway, Camden, London, NW1 7AH (the Premises).

29. Capital Accountants (Capital) were the Company's accountants throughout the existence of the Company. Capital prepared the Company's VAT returns.

30. At all material times the Appellants were the only directors of the Company.

31. James Ellis and Steve Lazenby, both officers of HMRC, made an unannounced visit to the Company at its Premises from approximately 17:55 - 19:56 Tuesday 7 June 2016 (the First Visit).

32. James Ellis and Marie Evans both officers of HMRC made an announced visit to the Company at its Premises from approximately 11:00 - 12:15 Wednesday 8 June 2016 (the Second Visit).

33. On 1 August 2016 Officer Evans wrote two letters to Capital. The first, as it appeared in the bundle, explains that she was checking the Company's corporation tax return for 2015. The second explains why she considers that the Company's sales figures should be uplifted. That letter invites the Company to send in its comments to Officer Evans on the uplifted sales figures.

34. On 1 August 2016 Officer Ellis also wrote to Capital, drawing on parts of Officer Evans' second letter, explaining his intention to issue a VAT assessment to the Company and the reasons why. Officer Ellis invites the Company to comment on his findings and calculations.

35. On 8 November 2016 Mr Hamid Mojarad and Mrs N Fatemi of Capital met Officer Ellis and Officer Evans at Capital's premises. Mr David Mojarad was unable to attend that meeting as he was unwell. On 25 November 2016 Officer Evans posted her notes of the meeting to Capital asking for a signed copy of the notes to be returned if they were agreed. Capital nor the Appellants agreed the notes but they did not dispute them either.

36. HMRC issued the Original Company Assessment as set out above on 17 February 2017.

37. On 15 March 2017 the Company asked for a statutory review of the Original Company Assessment and some of the decisions made in relation to corporation tax by Officers Evans which are not the subject of this appeal.

38. HMRC issued the Original Company Penalty on 23 May 2017.

39. HMRC issued a review conclusion letter on 31 July 2017 (the Review Conclusion Letter). Following the Review Conclusion Letter HMRC varied the Original Company Assessment and issued the Company Assessment on 13 November 2017.

40. HMRC varied the Original Company Penalty and issued the Company Penalty and the PLNs on 19 March 2019.

41. Further correspondence between the parties ensued and ultimately the Appellants appealed the PLNs.

The unannounced First Visit

42. Officer Ellis and Officer Lazenby both typed up their notes of the First Visit. Officer Ellis produced his at 14:53 on 9 June 2016. Officer Lazenby also produced his on 9 June 2016 (although no time is recorded on them). Those notes record a number of questions asked by Officer Ellis and Mr Hamid Mojarad's responses. They also record observations of Officer Ellis and Officer Lazenby. The officers' records were not in dispute and so from them we find as fact that on the day of the First Visit:

(1) On arrival the only person at the Premises was Mr Hamid Mojarad.

(2) Mr Hamid Mojarad explained:

(a) The Company's trading hours were as stated on the door: 8:00 - 19:00 Monday - Saturday;

(b) Only Mr Hamid Mojarad and Mr David Mojarad worked for the Company. Mr David Mojarad worked in the mornings and Mr Hamid Mojarad started work later and finished at closing. That day Mr Hamid Mojarad had started work at 13:30.

(c) The Company had in use a yellow 'Counter Book 500 Dry Cleaning Tickets', which included a carbon copy imprint (the Yellow Book). The left-hand side of the 'tear-able' yellow ticket was kept by the Company and ultimately attached to the completed garment. The right-hand side of the ticket was given to customers. The tickets were sequentially numbered and also contained 3 smaller tickets which were attached to the garments before being washed, repaired or dry-cleaned. If someone required more than 3 items to be cleaned etc blank labels were used and the respective ticket number was entered on the label for identification purposes.

(d) The till was broken and the Company no longer used a till.

(e) Money was kept in a lockable 'cash draw' underneath the counter (the Cash Drawer).

(f) The Company only accepted cash and the occasional cheque, it did not accept cards.

(g) The Company operated a single business account with NatWest.

(h) The Company's only income was from its dry-cleaning business.

(i) Monday and Tuesday were quiet days and Saturday was a busy day. July through until October were the busiest times of year.

(j) Each service/product had a price but this could vary depending on, for example, the loyalty of the customer and number of items. Further that no price list was kept in the shop.

(k) Generally payment was received when customers collected an item, but occasionally they paid in advance on drop off. If a ticket stated paid then the customer had paid in advance ie on dropping off the items to be cleaned. Mr Hamid Mojarad said that he or his brother would know how much was paid for the job.

(l) Uncollected clothes were given to charity after 3 months. No records were kept in relation to this but there were 'quite a lot'.

(m) He did not deal with cash handling. Mr David Mojarad started the day with £100 in the cash draw removing cash during the day. When Mr Hamid Mojarad closed for the evening he left cash for Mr David Mojarad to deal with in the morning. Further cash was used for petty cash but a receipt was kept to support any cash purchases.

(3) A spike was kept on the counter and each ticket for items collected that day was put on it. This was not the total sales for the day because if someone came in and paid in advance the ticket would not be put on the spike. Further there were 15 tickets on the spike. The value of the 12 paid on collection tickets was £218.85 (although Mr Hamid Mojarad said one of the tickets was £5 and not £6.95 giving a paid on collection total of £216.90). There were 3 pre-paid tickets (ie where payment had been made on drop off) on the spike that Mr Hamid Mojarad ascribed a value of £63. [Mr David Mojarad later ascribed these a value of £72.95].

(4) There were 14 tickets for items dropped off that day 3 had been paid on drop off with the total of £124.50.

(5) The cash in the till at 19:20 was approximately £123.95 (copper coins were estimated to be £2). Officer Ellis observed that this was little more than the daily float value. Mr Hamid Mojarad stated that his brother must have removed money earlier in the day but there was no documentation of that nor did Mr Hamid Mojarad know how much Mr David Mojarad had taken. Mr Hamid Mojarad said that Mr David Mojarad did not like having too much money on site.

(6) Mr Hamid Mojarad provided Mr Ellis with an envelope that contained purchase invoices and business bank statements. Mr Hamid Mojarad explained that Capital would collect that envelope.

(7) Mr Hamid Mojarad also said that a copy of the 'ticket book' is kept, takings were recorded and that information was given to the agent [Capital]. When asked to find the previous ticket book Mr Hamid Mojarad could not find it, he also said that the old ticket books were not kept on the Premises.

The announced Second Visit

43. Officer Evans typed up her notes of the Second Visit at 14:30 on 9 June 2016. Those notes record a number of questions asked by the visiting officers and Mr David Mojarad's responses. They also record observations of Officer Evans. The officer's record was not in dispute and so from them we find as fact that on the day of the Second Visit:

(1) On arrival the only person at the Premises was Mr David Mojarad.

(2) There had been 3 additional drop offs the day before after the officers had left. None of those drop offs had been pre-paid.

(3) Mr David Mojarad explained:

(a) The book in which the days takings are recorded are given to Capital together with an envelope of receipts.

(b) That he cashed up. He did this either at the end of the day or in the morning. He did this by adding up all of the tickets on the spike and comparing that to the money in the till. He said that they usually matched although sometimes they were £1 - £2 out where a discount may have been given. He said that Mr Hamid Mojarad put a note by the till to notify of any advance payments although this didn't happen often. It is the money in the till that is written in the book.

(4) The only account customer was the council who paid by cheque into the business account.

(5) There were very few non-collections. There was a rack of uncollected clothes at the back of the shop. Those clothes had electronically produced tickets on from an electronic till that was not in use at the time of the Second Visit.

44. Mr David Mojarad was instructed to start a new ticket book.

observations and the parties' positions

45. Before we outline the parties' positions it is useful to make some observations.

The corporation tax enquiry

46. It is clear that whilst Officer Ellis was conducting his VAT enquiry into the Company, Officer Evans was conducting a corporation tax enquiry into the Company. Documents from both enquiries were included in the hearing bundle. Documents from Officer Evans' corporation tax enquiry include information about the Appellants' personal financial position and the financial position of the Company. Some of HMRC's pleadings and Mr Marks' submissions and cross-examination of Mr David Mojarad touched on those points. However, we were not taken through any of those points in a meaningful way, nor were we taken to any underlying documents. Accordingly, our decision is not based on these points.

Access to the Company's records

47. Mr Doshi said that the Appellants had no access to the Company's records as it was in liquidation. However, the Appellants did not produce anything to demonstrate that they had tried to obtain copies of the Company's records or potentially relevant evidence from the liquidator or even Capital. Additionally, we note that during the period of HMRC's enquiries and prior to the issue of the Company Penalty upon which the PLNs are founded the Appellants had access to the Company's records. Therefore, this point does not assist the Appellants.

The parties' positions

48. The substance of the Appellants' case focused on three points. First, neither their nor the Company's behaviour was deliberate. Second, that the PLR determined for the Company's Assessment, which also forms the starting point for the PLNs, is excessive. They say that this is because the average ticket price used by HMRC is excessive. The Appellants did not challenge the average number of sales per day. The Appellants did not take issue with the use of averages. Rather they took issue with the numbers used to calculate these averages. Finally, the Appellants say that greater reduction should have been given for the Company's disclosure in relation to the Company Penalty.

49. HMRC maintain the average ticket price and the average number of sales per day set out in the Review Conclusion Letter.

50. We set out the basis of HMRC's calculations and the detail of the Appellants' points below.

discussion

The Company's record keeping

51. It is useful to consider the Company's approach to record keeping and the way in which information about the Company's trade was given to Capital who, amongst other things, prepared the Company's VAT returns, as this informs some of our later discussion.

52. Officer Evans' detailed notes of the Second Visit set out what Mr David Mojarad said about his process of cashing up:

D said that he cashes up either at the end of the day or in the morning. He adds up all of the tickets on the spike and compares to the till. He said the [sic] usually match - maybe £1 - 2 out where they might give some discount on payment. I asked whether the advance payments mean that the till and tickets don't match. He then said it did. D said that his brother will put a note by the till to notify any advance payments. He said this doesn't happen often. The money in the till is the amount written in the book.

In this passage we understand and, insofar as necessary, find as fact that, 'advance payments' refer to items dropped off and paid for on the same day. That is because any tickets on the spike where payments have already been made (ie on drop off) will simply say paid and will not have a value written on them so do not need to be accounted for as part of the 'cashing up' process. Whereas cash paid for items dropped off and paid for on the same day needs to be accounted for separately (by way of 'a note by the till') because there would be no information about that cash on the spike. This approach was also set out in Mr David Mojarad's witness statement, dated 27 September 2018, where he explained that where customers paid in advance the money would be added up as part of the takings of the day. In light of Mr David Mojarad's explanation, on the day of the First Visit, the Cash Drawer should have contained:

|

The amount paid for collected items |

£218.85 |

|

The amount paid for pre-paid items dropped off on that day |

£124.50 |

|

Float |

£100 |

|

Total |

£443.35 |

However, on the day of the First Visit the actual amount in the Cash Drawer was approximately £123.95. During the First Visit nothing was found, or produced subsequently, to document or explain this discrepancy, as Mr David Mojarad suggested it would be. Nor was the discrepancy addressed during the hearing.

The average ticket price

53. Following the First and Second Visit HMRC calculated what they considered the Company's sales should be, for VAT purposes, by reference to average ticket prices and average number of sales per day, and compared the results of that exercise with the Company's declared sales. Both the Original Company Assessment and the Review Conclusion Letter concluded that the declared sales were insufficient, although at varying levels, meaning the Relevant Returns were inaccurate. Subsequent to the Review Conclusion Letter HMRC utilised an average ticket price of £19.65 to reduce the Company Assessment. This was calculated using the Yellow Book. That ticket book:

(1) Contained 465 tickets of which values could be ascribed to 375.

(2) The 375 tickets gave total sales of £7,370.95. Which is an average of £19.65 per ticket (where a price could be identified).

54. The Appellants' case is that the average ticket price should be less for the following reasons:

(1) Using an average ticket price of £19.65 (an average from 2016 prices) fails to take into consideration that it is unlikely that prices would have been static for 7 years. In particular Mr Doshi's skeleton argument made the following submissions:

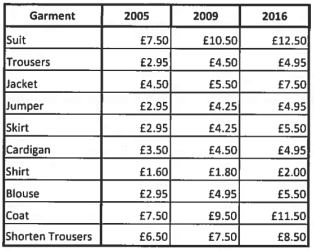

(a) The average ticket price should be amended in line with the price list provided in Mr David Mojarad's witness statement dated 27 September 2018 as follows:

Mr David Mojarad explained that he had created the price list from memory.

(b) That RPI should be used to reduce the average ticket price.

Each of the above methods yielded an amount by which the PLNs could be reduced. Mr Doshi added them together and divided them by 2 and concluded that that was the amount that the PLNs should be reduced by.

(2) The ticket book used from 8 June 2016 until 18 June 2016 provided an average ticket price of £13.97 in 2016. In reference to this second average ticket price Mr Doshi said again that RPI should be used to reduce the average ticket price and went on to set out an amount by which the PLNs should be reduced.

(3) HMRC's average ticket price was higher than normal because of the two May bank holidays: people had been spring cleaning and so brought in bulkier items that were more expensive to clean (eg curtains) and a larger number of items per ticket therefore increasing the average ticket price. In particular, Mr Doshi referenced two tickets placed on the spike on the day of the First Visit: £65 and £85. If these are removed then the Appellants say £291.80 (the value of the tickets on the spike) less these tickets (£150) all divided by 13 gives an average ticket price of £10.91. Nothing was said about RPI in relation to this lower average ticket price nor did Mr Doshi set out an amount by which the PLNs should be reduced in reliance on this amount.

55. Mr Doshi did not settle on one revised average ticket price and so we consider them all.

56. Turning to the evidence. The Appellants' position was that the Company did not produce price lists. That is the explanation for why the only price list available is from Mr David Mojarad's recollection. The price list was first produced alongside Mr David Mojarad's witness statement prepared for an appeal brought by the Company in relation to the Company Assessment and/or the Company Penalty on 27 September 2018. We neither heard nor saw any evidence about the price list other than its production. For example, there was no: explanation given as to why this fundamental aspect of the Appellants' case (which it would have also been in relation to the Company Assessment and Company Penalty) had only emerged in September 2018, over two years after the First Visit; evidence from Mr David Mojarad about why the changes were made in particular years or the basis on which he/he and Mr Hamid Mojarad changed the prices; no documentary or contemporaneous evidence supporting the price list; nor even confirmation as to when the prices were changed in 2016. Finally, we note that the price list involves a gap of four and then seven years between changing prices ie even on the Appellants' case seven years may elapse before prices are changed. Therefore we do not accept that the price list is a credible or reliable basis on which to calculate the average ticket price and do not accept Mr Doshi's submission that the prices must have changed in the preceding seven years.

57. Similarly in relation to RPI we heard no evidence nor were shown any documentary evidence that RPI had any impact on the Company's prices. Therefore we do not accept that RPI is a credible or reliable basis on which to calculate the average ticket price.

58. Mr David Mojarad's witness statement of 27 September 2018 states that over the 10 working days 8 - 18 June 2016 89 tickets were issued totalling £1,243.55, an average ticket price of £13.97. The Appellants did not produce any documentary evidence to support this statement, including the ticket book itself. The only explanation we received as to why was that, under cross-examination, Mr David Mojarad said he thought that he had given the new ticket book to Capital, although that is clearly not a complete explanation. The first reference shown to us of an average ticket price close to £13 is in an email dated 21 December 2016 from Mr David Mojarad in which he said the average ticket price from the new ticket book was around £13. Given HMRC's enquiries, the failure to provide the ticket book to HMRC or mention the average ticket price of £13.97 before December 2016 is in our view extraordinary. Further, the only contemporaneous evidence we were shown in relation to these dates was Officer Evans' notes of the Second Visit which recorded the value of the 4 tickets on the spike, which total £95.90 giving an average ticket price of £23.97. Therefore we do not accept that £13.97 is a credible or reliable average ticket price.

59. We have some sympathy with the broad proposition that for a dry cleaner May - June might involve a greater concentration of higher than average ticket prices because of the two bank holidays in May. However, in order to form part of our decision as to average ticket price we are required to consider the evidence before us. The Appellants' position is that we should simply discount the larger priced items and create a new average ticket price (£10.91, see above). Such an approach simply adopts the position that there would never be tickets with a higher than average ticket price which is implausible. Mr Doshi also said in submissions, which was not supported by any evidence, that May was like Christmas for dry-cleaners and the quantum of sales would be 25% higher. Again, the lack of any detailed evidence was notable, for example, in terms of what the spread of higher than average ticket prices are across the year, or anything that would assist in calculating, in a principled way, an average ticket price that accounts for a greater concentration of higher than average ticket prices in May - June. Therefore, we reject a revised average ticket price of £10.91.

60. Given our conclusions we do not make any findings about Mr Doshi's methods of calculation that produced the price list and RPI based reductions.

61. We heard no submissions on how the average ticket price should be varied to take account of uncollected and unpaid items nor discounts provided to certain customers.

62. Mr Doshi made the point that we did not have any documentary evidence from HMRC of the Yellow Book which HMRC had removed from the Company. However, the average ticket price that arises from the Yellow Book was first recorded in Officer Ellis' letter of 1 August 2016. That average price was discussed during the meeting on 8 November 2016 and Officer Evans' notes of that meeting record that the Yellow Ticket book was returned to Mr Hamid Mojarad. The purpose of returning the Yellow Book was to allow the Appellants to ascribe prices to the 90 tickets that did not have prices written on them. We note that this was never done. As set out above, the notes of that meeting were sent to Capital and whilst there is nothing to suggest that they were agreed, there is similarly nothing to suggest that they were disputed. Therefore, we find as fact that the Yellow Book was returned to Mr Hamid Mojarad on 8 November 2016 and so Mr Doshi's point can go nowhere. Finally, in our view the average provided by using the tickets from the Yellow Book is more reliable than the averages Mr Doshi suggests we adopt: it uses 375 tickets rather than 89 or 13 to generate an average price.

63. In light of the foregoing we uphold HMRC's average ticket price of £19.65. With the consequence that the PLR which flows through to the PLNs via the Company Assessment and Company Penalty remains the same.

Inaccuracy

64. Mr Doshi did make two submissions on the accuracy of the Relevant Returns. First he said that the Relevant Returns were accurate because the Appellants gave Capital the correct information. However, the only detailed evidence before us on this point was the evidence on average ticket price which we discuss above. It follows from our conclusion on the average ticket price that the Relevant Returns were inaccurate and we make that finding. Therefore, we reject Mr Doshi's submission.

65. Mr Doshi also observed that, on the day of the First Visit, the Company had not filed its VAT return that covered that day. Further, that a comparison exercise between what had been declared in the VAT return covering the day of the First Visit with what the HMRC officers had found on the day of the First Visit to see if they could be reconciled had not been performed. From what was before us Mr Doshi's observations appear to be correct and HMRC did not disagree. However, insofar as these observations were intended to be a submission on the accuracy of the Relevant Returns, the fact that Mr Doshi did not develop the latter point (including by reference to any evidence) means such a submission cannot succeed.

Deliberate behaviour

66. There was no dispute that the Company's disclosure was "prompted" because HMRC only became aware of the inaccuracies after the First Visit which was unannounced. HMRC concluded that the Company's behaviour had been deliberate but not concealed, and Mr Doshi submitted that the Company had not acted deliberately.

67. It was common ground that the Appellants were the controlling mind of the Company Therefore, our findings as to the Company's behaviour applies equally to the Appellants.

68. HMRC say the Company's actions were deliberate but not concealed because:

(1) The directors (ie the Appellants) paid business income directly into their private business accounts and did not declare these funds as part of the Company's sales.

(2) The directors (ie the Appellants) knowingly made incorrect declarations of sales over a sustained period of time, in order to artificially reduce sales, which is a deliberate act.

(3) The failure to maintain adequate business records means that the Relevant Returns could not be accurate. Further the relevant period of time indicates a persistence that goes beyond a careless mistake.

(4) A significant proportion of sales were under-declared over a lengthy and continued period.

(5) Whilst the actions of the Directors (ie the Appellants) were deliberate in nature, there was no evidence of pro-active steps made to further conceal these under-declared sales.

69. For the reasons set out above we do not accept HMRC's submissions in relation to the Appellants' private business accounts.

70. Mr Doshi made forceful submissions that, in essence, the Company really did not know what it was doing insofar as its tax affairs were concerned. In particular the Company relied wholesale on Capital to ensure that the Company's tax affairs were in order. That included: what it needed to provide to Capital to prepare accurate VAT returns and what records it should keep. Mr Doshi also said that none of the correspondence in the hearing bundle suggested that Capital were dissatisfied with what the Company had provided to them. Therefore, at worst the Company's behaviour was careless or reckless.

71. More particularly, the Appellants say that the Company did not know that the Relevant Returns were inaccurate because they say, in essence, that it did not know what it was doing and relied absolutely on Capital (see above). Mr David Mojarad also explained that the Company had relied on Capital in his evidence. However, as with other parts of the Appellants' case, the evidence we saw and heard did not contain any substantive detail, nor were we shown any documentary or contemporaneous evidence supporting the Appellants' position. For example, there was no: information about the basis on which Capital were acting for the Company, including their preparation of the Company's VAT returns; any advice from Capital about what records the Company should keep that might explain the very minimal records kept by the Company; or anything that explained why what the Company had sent to Capital translated into inaccurate VAT returns.. Therefore, we do not accept the Appellants' position.

72. It is the Appellants' case that the figure that they used for the Company's daily sales (sent to Capital) was the amount of cash in the Cash Drawer. Therefore, for the Company's VAT returns to be accurate it was critical that that figure matched the Company's daily sales. For the reasons set out above this was not the case on the day of the First Visit and the Appellants were aware of this. We have neither seen nor heard anything from either the Company or the Appellants to explain why this was the case.

73. In our view, given the number of years of inaccuracies and the amounts of the inaccuracies, the inaccuracies cannot sensibly be considered as a few minor discrepancies at the margins caused by a lack of knowledge or occasional oversight.

74. In light of the foregoing we conclude that the Company knew that the Relevant Returns were inaccurate and that HMRC would rely on them as to the amount of VAT due from the Company. Consequently, HMRC have shown that the Company's, and so the Appellants' behaviour was deliberate. This also means that the defence under paragraph 18(3) Schedule 24 is not available.

75. The Appellants did not challenge the attribution of 50% of the Company Penalty to each of the Appellants.

Reduction for disclosure

76. The penalty for a prompted disclosure where the behaviour is "deliberate but not concealed" is between 35% and 70% of the PLR, see paragraphs 4, 4A(1)(a) and 10 Schedule 24. Such penalties must be reduced according to the quality of disclosure, see paragraph 10 Schedule 24. There is no statutory provision as to how officers are to apply such mitigation. However, HMRC takes the following approach:

(1) 30% reduction may be applied for Telling;

(2) 40% reduction may be applied for Helping; and

(3) 30% reduction may be applied for Giving.

Mr Doshi took no issue with this approach.

77. HMRC applied the following reductions:

(1) 0% for Telling because there was no satisfactory explanation for the discrepancies.

(2) 25% for Helping as the Company cooperated with some aspects of HMRC's enquiry: attending some meetings and providing some information.

(3) 25% for Giving as the Company had provided some records. However, no further reduction had been applied because HMRC needed to issue a 'Notice to produce documents' in accordance with paragraph 1 Schedule 36 Finance Act 2008 on 16 December 2015.

78. Mr Doshi submitted:

(1) That the Appellants had informed HMRC as to how the business was operated and Capital explained how the Company's VAT Returns were filed and provided bank statements. Therefore, the reduction for Telling should be at least 20%.

(2) That the Appellants and their accountants had cooperated as fully as possible. Therefore, the reduction for Helping should be at least 30%.

79. The Appellants agreed with the 25% reduction for Giving.

80. The Company did not tell HMRC about the inaccuracies, nor, as we have found did it provide a satisfactory explanation for the discrepancies. Therefore, we uphold HMRC's decision that there should be no reduction for Telling.

81. Having reviewed the correspondence between the parties we do not accept Mr Doshi's submission that the Company and Capital had cooperated as fully as possible. Consequently, we prefer HMRC's position that the Company had cooperated with some aspects of HMRC's enquiry. Therefore, we uphold HMRC's decision that there should be a 25% reduction for Helping.

82. In light of the above we agree with the reduction applied to the Company Penalty. Consequently, the amount of each PLN remains £12,145.50.

conclusion

83. For the reasons given the appeal is dismissed.

Right to apply for permission to appeal

84. This document contains full findings of fact and reasons for the decision. Any party dissatisfied with this decision has a right to apply for permission to appeal against it pursuant to Rule 39 of the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Tax Chamber) Rules 2009. The application must be received by this Tribunal not later than 56 days after this decision is sent to that party. The parties are referred to "Guidance to accompany a Decision from the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber)" which accompanies and forms part of this decision notice.

Release date: 29th MAY 2025