Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

First-tier Tribunal (Tax)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> First-tier Tribunal (Tax) >> E-ZEC MEDICAL TRANSPORT SERVICES LIMITED v Revenue & Customs (VALUE ADDED TAX - non-emergency ambulance services) [2022] UKFTT 302 (TC) (25 August 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2022/TC08574.html

Cite as: [2022] STI 1215, [2023] SFTD 367, [2022] UKFTT 302 (TC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation: [2022] UKFTT 302 (TC)

Case Number: TC08574

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL

TAX CHAMBER

By remote video hearing

Appeal reference: TC/2019/02575 & TC/2021/11368

VALUE ADDED TAX - non-emergency ambulance services - whether zero rated under Item 4 Group 8 Schedule 8 VATA 1994 - Jigsaw Medical Services Ltd [2018] UKUT 222 (TCC) considered

Heard on: 8,9,10 &22 June 2022

Judgment date: 25 August 2022

Before

JUDGE GUY BRANNAN

Between

E-ZEC MEDICAL TRANSPORT SERVICES LIMITED

Appellant

and

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HER MAJESTY’S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS

Respondents

Representation:

For the Appellant: Melanie Hall QC and Stuart Walsh instructed by Pinsent Masons LLP

For the Respondents: Joanna Vicary, counsel, instructed by the General Counsel and Solicitor to HM Revenue and Customs

DECISION

Introduction

1. E-zec Medical Services Limited (“the Appellant”) appeals against decisions made by HMRC to the effect that its provision of non-emergency ambulance services (“the ambulance services”) is not zero rated under Item 11 Group 7 Schedule 9 of the Value Added Tax Act 1993 (“VATA”). The Appellant contends that its ambulance services are properly zero rated. The appeal principally concerns the proper construction and application of Note 4D to Item 4(a) Group 8 Schedule 8 VATA which, for convenience, I shall refer to respectively as “Note 4D” and “Item 4(a)” hereafter.

2. It is common ground that the ambulance services in question are exempt from VAT under Item 11 Group 7 Schedule 9 VATA. The dispute, as I have indicated, solely concerns the question whether the ambulance services are zero rated because, if so, the Appellant will be able to recover its input tax attributable to the ambulance services whereas it cannot do so if those services are merely exempt. The parties agreed that if the ambulance services are zero rated the zero rating takes precedence over exemption under section 30(1) VATA.

The evidence

3. I was provided with an electronic bundle of documents running to some 3,500 pages. On behalf of the Appellant, Mr Steve Shaw, formerly the managing director of Cartwright Vehicle Conversions Ltd (“Cartwright”), and Mr Andrew Wickenden, formerly the managing director of the Appellant, produced witness statements and were cross-examined. Mr Wickenden’s evidence included a number of videos showing the various configurations of non-emergency ambulances used by the Appellant. These videos were shown during the hearing, particularly during Mr Wickenden’s cross-examination.

4. I found both Mr Shaw and Mr Wickenden to be reliable and credible witnesses.

The legislation

5. Article 132(1)(p) of the Principal VAT Directive (“the PVD”) provides that Member States shall exempt the following:

“The supply of transport services for sick or injured persons in vehicles specially designed for the purpose, by duly authorised bodies”

6. Article 131 of the PVD provides as follows:

“The exemptions provided for in Chapters 2 to 9 shall apply without prejudice to other Community provisions and in accordance with conditions which Member States shall lay down for the purposes of ensuring the correct and straightforward application of those exemptions and of preventing any possible evasion, avoidance or abuse”

7. As regards UK domestic legislation, Section 31(1) VATA provides:

“A supply of goods or services is an exempt supply if it is a description for the time being specified in Schedule 9.”

8. Item 11, Group 7, Schedule 9 VATA “health and welfare” (“Item 11”) exempts:

“The supply of transport services for sick or injured persons in vehicles specially designed for that purpose”

9. In relation to zero rating, Section 30(1) provides:

“Where a taxable person supplies goods or services and the supply is zero-rated, then, whether or not VAT would be chargeable on the supply apart from this section-

(a) no VAT shall be charged on the supply; but

(b) it shall in all other respects be treated as a taxable supply;

and accordingly the rate at which VAT is treated as charged on the supply shall be nil.

10. Section 30(2) VATA provides:

“A supply of goods or services is zero-rated by virtue of this subsection if the goods or services are of a description for the time being specified in Schedule 8 or the supply is of a description for the time being so specified.”

11. During the relevant prescribed accounting periods Item 4(a) Schedule 8 Group 8 VATA provided zero rating for the following supplies:

“Transport of passengers in any vehicle, ship or aircraft designed or adapted to carry not less than 10 passengers.”

12. Note 4D Schedule 8 Group 8 VATA provides as follows:

“Item 4(a) includes the transport of passengers in a vehicle -

(a) which is designed, or substantially and permanently adapted, for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair or two or more such persons, and

(b) which, if it were not so designed or adapted, would be capable of carrying no less than 10 persons.”

13. Note 4D was inserted into VATA by the Value Added Tax (Passenger Vehicles) Order 2001, SI 2001/753. The Explanatory Note provided (in the last paragraph):

“The Order also allows zero-rating to apply where passengers are transported in vehicles which, but for the fact that they have been designed or adapted for wheelchair users, would have been capable of carrying 10 or more passengers.”

Agreed facts

14. Although a number of factual issues were in dispute, the parties helpfully produced an Agreed Statement of Facts in relation to facts which were not contested. The Agreed Statement of Facts was as follows:

Appellant and Background

1) The Appellant is registered for VAT with effect from 1 March 2004.

2) The Appellant is one of the largest providers of Non-Emergency Patient Transport Services (“NEPTS”) in the UK.

3) The Appellant provides NEPTS on behalf of various NHS trusts around England for sick and injured individuals to and from hospital and doctor’s appointments.

4) The Appellant operates a fleet of over 500 vehicles (in addition to employing sub-contractors) to deliver its NEPTS.

5) The Appellant operates its services from 29 bases across the UK employing over 1472 personnel, from Ambulance Care Assistants to Paramedics.

6) The Appellant’s main client is the NHS with the contracting parties being -

· A NHS trust;

· A NHS Foundation Trust; and

· A NHS Clinical Commissioning Group.

Non-Emergency Patient Transport Services (NEPTS)

7) NEPTS is defined by the Department of Health as “non-urgent, planned, transportation of patients with a medical need for transport to and from premises providing NHS healthcare and between NHS healthcare providers using a wide range of vehicle types and levels of care consistent with the patients’ medical needs”.

8) NEPTS involve transporting day patients, recurring treatment patients (such as patients undertaking dialysis and cancer treatments) and patients on daily discharge and often involves taking multiple passengers in one journey either from, or to, multiple destinations. This will include the transport of wheelchair users and stretcher-bound patients.

9) NEPTS is intended to improve access to healthcare for eligible patients with a qualifying medical need attending medical treatments, outpatient appointments and/or diagnostic services and should provide safe, timely and comfortable transport to eligible patients, without detriment to their medical condition. NEPTS aims to transport multiple patients to NHS and community premises for healthcare as safely and efficiently as possible.

10) The eligibility criteria to access NEPTS are set out in a document published by the Department of Health called “Eligibility Criteria for Patient Transport Services” dated 23rd August 2007 and in the NHS standard contract.

11) Patients access the NEPTS by undertaking a telephone initial assessment with the Appellant to determine eligibility.

12) Patients can book NEPTS directly with the Appellant if eligibility criteria are satisfied.

13) The Appellant is required to transport patients (and parents, carers etc.) with varying medical conditions and mobilities. Some patients may rely on a wheelchair for mobility and the vehicles need to be able to accommodate this.

14) On a typical day each vehicle of the Appellant will carry at least one wheelchair passenger.

15) On average, approximately 40% to 50% of all passengers carried by the Appellant (which includes the driver and any second E-zec crew member) require a wheelchair, bring their own wheelchair, require a bariatric wheelchair or require a stretcher.

Contracting for NEPTS

16) NEPTS are procured by the NHS through a competitive tender process.

17) The standard contract term is (usually) five years with an option to extend by a further two years.

18) The time taken to complete the tender response is typically several months.

19) If successful, a mobilisation period of 4 to 6 months then starts. This allows the supplier to obtain and configure the necessary vehicles.

20) The successful bidder will enter into an NHS standard contract.

21) All NEPTS providers must be registered with the Care Quality Commission (“CQC”) and meet the CQC’s standards.

22) Contracts do not specify how the vehicles used should be configured in terms of how many seats the vehicles must contain.

23) Contracts require the provider of NEPTS to ensure that the vehicles used can safely cater for patients with a variety of mobility requirements, including walking patients, bariatric patients, high dependency (“HDU”) patients (if applicable to the service provision) and those that use wheelchairs and stretchers.

24) The Appellant stipulates the number and type of vehicles to be used for the NEPTS during the tender process.

25) The service specifications of NEPTS are defined by a schedule to the contracts.

The Appellant’s Vehicles

26) The Appellant has used vehicles made by a number of different manufacturers to supply NEPTS.

27) The vehicle makes and models used by the Appellant now or in the past for NEPTS are Peugeot Boxer, Renault Master, Citroen Relay, LDV Convoy and Vauxhall Vivaro.

28) The Appellant has elected to register all of its current and past NEPTS vehicles as ambulances with the DVLA, although this is not a formal requirement of the NHS standard contract.

29) Vehicles of the type used by the Appellant cannot be purchased new from manufacturers pre-configured to the design and specifications required by the Appellant to provide its contracted services.

30) The Appellant places an order with a specialist converter (the majority of the Appellant’s orders have been placed with Cartwright Vehicle Conversions Ltd) for the number of vehicles it requires, of a specified make and model (typically Peugeot Boxer 435 L3 H2), to be converted in accordance with the Appellant’s instructions. The specialist converter then purchases the “base” panel vans directly from the manufacturer and carries out the conversion in accordance with the Appellant’s order. The specialist converter sells the converted vehicle to a third-party leasing company who then lease the vehicles to the Appellant.

31) For the purposes of the appeal, “base panel van” means a vehicle which is in a roadworthy condition (subject to registration and taxation) fitted with front seating only (driver and passenger), save any commonly available options - such as trim levels, audio or driver convenience upgrades.

32) The NEPTS contracts do not stipulate that each and every vehicle used to carry passengers must be capable of carrying wheelchair and stretcher patients. However, the Appellant instructs the specialist converter to include the adaptions necessary to safely carry wheelchairs and stretchers in all vehicles to cater for the multiple mobility requirements across its patient population. Having a single vehicle configured to accommodate different passengers with different needs allows for passenger maximisation.

33) There are a total of five specifications that the Appellant orders from the specialist converter and may use in the course of providing NEPTS, some or all of which will be used as required depending on the service specifications under a contract. These are:

· 8 seats (including driver), and facilities for up to two wheelchairs;

· 6 seats (including driver), and facilities for up to two wheelchairs and one stretcher;

· 5 saloon seats (plus driver), and facilities for up to one bariatric wheelchair and one bariatric stretcher;

· 4 saloon seats (plus driver), and facilities for up to one bariatric wheelchair and one bariatric stretcher;

· 5 seats (including driver), and facilities for up to one bariatric wheelchair and one bariatric stretcher (HDU).

34) The vehicles used by the Appellant (typically a Peugeot Boxer 435 L3 H2) are typically configured to include an interior seating specification of 8 seats (including driver): a driver’s seat and 7 seats in the rear of the vehicle.

35) The 1 or 2 front passenger seats in a base panel van delivered to the converter are removed and replaced with a wheelchair cage to safely carry folding wheelchairs. Folding wheelchairs are stored in the cage for patients who do not have their own or require temporary use of a wheelchair due to mobility issues developed on the day of transport - for example, following chemotherapy treatment.

36) The 7 seats in the rear of the vehicle are designed in a variety of ways; some are permanent and some removable, foldable and/or rotatable.

37) Each vehicle includes space from the rear doors through the central channel of the vehicle to transport 2 wheelchairs. Each vehicle is fitted with Unwin tracking restraints to lock wheelchairs in place and a wheelchair ramp.

38) If a patient required a stretcher they would also use the tracking and the 3 seats at the rear of the vehicle would be folded to accommodate this.

39) The maximum number of passengers (including driver) carried in the Appellant’s NEPTS vehicles is 8.

40) If an Appellant’s typically configured NEPTS vehicle with wheelchair and stretcher adaptions was simultaneously loaded with 10 persons (including driver) it would breach the 3500kg legal weight limit of the vehicle and invalidate the NEPTS vehicles insurance.

41) The European Commission classifies vehicles as part of emission standards and other vehicle regulations. Passenger cars receive an “M” categorization, while commercial vehicles receive an “N” categorization. Base panel vans without adaptions would receive an N categorization.

42) A M1 class vehicle is a four-wheeled passenger vehicle that has been designed or adapted to carry up to 9 passengers (including the driver). A M2 class vehicle is a four-wheeled passenger vehicle that has been designed or adapted to carry more than 9 passengers (including the driver). The makes and models of the base panel vans ordered by the Appellant are designed in such a way as to be capable of adaptions and internal configurations that can classed as either a M1, M2 or N1 vehicle.

43) All of the Appellant’s vehicles used to supply the NEPTS in relation to this dispute are of a type approved by Driving and Vehicle Licencing Agency as Category M1. Since such classifications began, the Appellant’s past NEPTS vehicles were also classified as M1.

44) If the Appellant carried more than 9 persons (including driver) in one of its vehicles it would exceed the maximum passenger capacity under the vehicle’s current category M1 classification.

45) The Appellant has not used and does not currently intend to use NEPTS vehicles to carry 10 persons (including driver).

Representative Vehicle

46) The Appellant’s Peugeot Boxer 435 L3 H2 base vehicle described at paragraphs 33) to 39)) is agreed to be a representative vehicle.

47) Aside from the Vauxhall Vivaro, it is agreed that base panel van models from other manufacturers used or previously used by the Appellant for NEPTS activities (Renault Master, Citroen Relay, LDV Convoy), which are, or were, of a similar design, similar dimensions and similar carrying capacity, are, or were, capable of being converted into the specifications identified in this agreed statement of facts.

48) Furthermore, such vehicles are, or will have been, restricted in their use in the same way as the Peugeot Boxer vehicle now typically in use. For those reasons, the parties agree that a Peugeot Boxer vehicle of the type typically used currently by the Appellant for NEPTS activities is a fair representation of the characteristics of such vehicles and the final determination of the appeal in respect of the Representative Vehicle will apply equally to in respect of all other base makes and models used by the Appellant as outlined in paragraph 47) above (with the exception of the Vauxhall Vivaro).

Additional facts taken from the evidence

15. As already indicated, the Appellant’s vehicles are converted by Cartwright Vehicle Conversions Ltd (“Cartwright”). The main features of the conversion carried out by Cartwright which are relevant to this appeal are:

(1) the addition to the vehicle of an aluminium flooring system (“the floor system”) which is bonded to the existing floor of the vehicle and fitted with recessed aluminium tracking (“Unwin tracking”) and restraints for seats, wheelchairs and stretchers. The flooring system is a “sandwich” consisting of a layer of aluminium, a thin layer of plywood (approximately 3 mm deep), a layer of foam and another layer of aluminium. There are eight tracks that are bolted through the “sandwich” allowing seats, wheelchairs and stretchers to be secured with fastenings using the tracks. The floor system is bolted to the frame of the vehicle. Cartwright acquires the floor system as a completed and assembled product from a company called NMI. The weight of the floor system is approximately 128 kg.

(2) A wheelchair ramp (“the ramp”), allowing a patient in a wheelchair to access the rear of the vehicle.

(3) A winch (“the winch”) to assist with the loading and unloading of wheelchairs and stretchers.

(4) The replacement of the two front passenger seats with a metal wheelchair pen or cage (“the wheelchair pen”).

16. There is no dispute that the winch and the ramp were adaptations for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair for the purposes of Item 4(a). The dispute concerns the flooring system and the wheelchair pen.

17. The Appellant would typically have around 80% of its vehicle capacity for the NHS Trust booked within three working days of the journey. However, patients may book NEPTS right up until the same day as their appointment and so it is only at that point that the Appellant can finalise the routes, calculate the total passenger numbers and fully assess the patients’ mobility needs. This is why it was important for the Appellant to have “vehicle multi-functionality” in its fleet of vehicles.

18. The route mapping exercise for the Appellant’s vehicles is complex and is carried out by a mix of automated software and a team of approximately 20 experienced operators.

19. To operate most efficiently the Appellant requires a fleet of vehicles configured in such a way that enables it to respond quickly and effectively to patient demand. The Appellant, therefore, takes the view that, although it reduces overall seating capacity, all of its vehicles should be adapted for wheelchair use. This was the most common vehicle configuration used amongst the leading providers of NEPTS

20. It would be an option for the Appellant to reconfigure part of its current fleet, or to order new vehicles to fulfil contracts, which include standard seating only. As Mr Wickenden explained, the vehicle is designed and supplied by the manufacturer as a “base” panel van ready for conversion to one of many variant options to cater for the user’s needs, but if the Appellant were to acquire or configure vehicles with only standard seating the vehicles would contain at least 10 seats.

21. A significant number of the Appellant’s passengers travel in standard seating so this could increase individual vehicle capacity on various routes. Mr Wickenden exhibited a table demonstrating the percentage of passengers across the mobility categories that utilised the Appellant’s NEPTS in 2020:

|

Description |

Activity |

% |

|

Walking Patient |

410,038 |

25% |

|

A wheelchair will be available to transfer if required |

579,617 |

35% |

|

Patient travels in own wheelchair |

281,482 |

17% |

|

A bariatric wheelchair will be available to transfer if required |

23,927 |

1% |

|

Stretcher ambulance |

140,237 |

9% |

|

Bariatric stretcher ambulance |

5021 |

0% |

|

Patient Escort |

200,901 |

12% |

22. Mr Wickenden noted that the table was slightly inaccurate because the Appellant’s crews were not included in the percentages. Nonetheless, Mr Wickenden said that the overall point was the same. The table showed that 25% of passengers using the Appellant’s NEPTS were categorised as “walker” patients. An additional 12% of passengers on journeys would be patient escorts or carers. Further, around half of the wheelchair patients travelled in standard seating with their wheelchair stored in storage installed in the front cabin of the vehicle during their journey.

23. The Appellant valued the greater flexibility a full fleet of wheelchair-adapted vehicles provides, over and above the additional seating capacity that a vehicle fitted only with standard seats would provide, it considered that it resulted in a more efficient and cost-effective service.

24. With the exception of the Vauxhall Vivaro, all of the vehicles are long-wheelbase vehicles. The Appellant had not claimed zero-rating for NEPTS supplied using the Vauxhall Vivaro because it did not consider this vehicle type would be capable of carrying ten or more passengers without the wheelchair adaptions. Each of the other vehicle makes and models were largely interchangeable in terms of their seating capacity and their ability to be configured as required to deliver NEPTS as outlined above.

25. The vehicles are purchased by the Appellant as a “base” panel van. “Base” state essentially means that the vehicle is in a roadworthy condition fitted with front seating only, save any commonly available options - such as trim levels, audio or driver convenience upgrades.

26. By designing the vehicles in this way, the shell can be adapted post-sale by the purchaser to meet their needs or the needs of their customers - for example, by adding rear seating and windows to use the vehicle as a minibus; or by leaving it largely untouched for trade use as a van. The standard build for the front seating in such vehicles consists of a driver’s seat, plus either one additional passenger seat or a two-seater bench; and whilst some vehicle models can be purchased with a glazing option, conversion companies typically do not purchase this option, preferring to add windows as part of their conversion.

27. The maximum seat capacity for the base state vehicle models used by the Appellant was generally between 12 and 14 seats before wheelchair adaptations.

28. The Appellant ordered the 8+2 configuration (i.e. eight seats including the driver but with the potential, on removing some of the seats, to accommodate two wheelchairs or a stretcher) because of the flexibility it provided. This was particularly valuable in more rural areas where the journey distance - both between patients’ premises and between the patients’ premises and the final destination - was significantly greater than in cities.

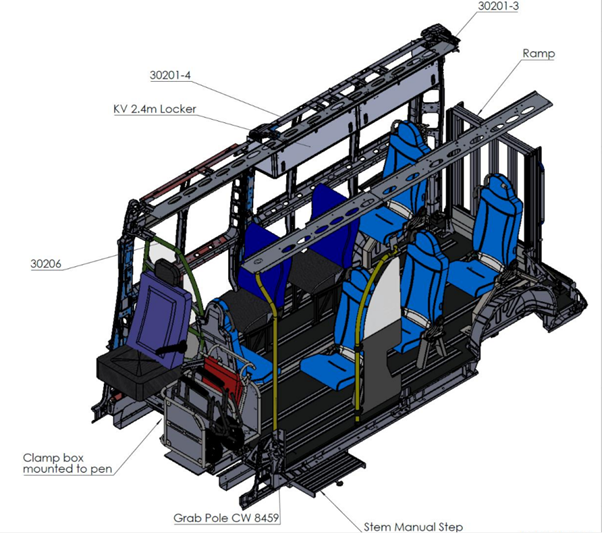

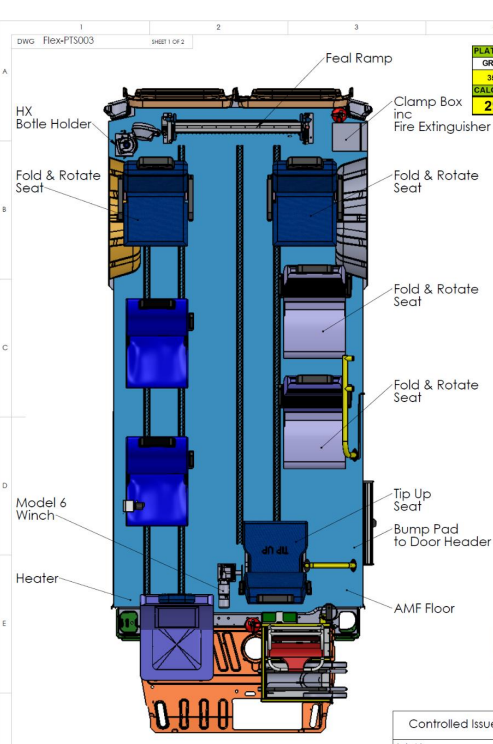

29. Diagrams (taken from the exhibits to Mr Wickenden’s first witness statement) showing the standard 8+2 configuration ordered by the Appellant in respect of the VAT periods under appeal are set out in Appendix 1.

30. Mr Wickenden’s evidence was that the 8+2 configuration could accommodate a driver and 7 patients in standard seats and two patients in wheelchairs simultaneously, but to do so - with the addition of the wheelchair ramp and tracking etc. - would breach the legal weight limit of the vehicle and invalidate the vehicle insurance policy in the event of an accident. This is because clause 1(f) of the General Exclusions to the Appellant’s fleet insurance policy excludes the insurer’s liability where the Appellant’s vehicle is “carrying a load in excess of that for which it was constructed or in excess of the maximum carrying capacity advised to us.” Mr Shaw’s evidence was that each of the vehicles Cartwright had converted for the Appellant had been prepared to carry up to a maximum of eight seated passengers (including the driver); with facilities to safely carry two wheelchair passengers. With the weight of the wheelchair adaptions, a vehicle carrying ten passengers (including the driver, seven seated passengers, and two wheelchair passengers), would almost certainly breach the 3,500kg maximum weight allowance of the vehicle, and so in practice would not be used to carry this many passengers. Mr Shaw said that without the wheelchair adaptions these vehicles could be driven with ten passengers (including the driver) comfortably within the vehicle’s maximum weight allowance of 3,500kg. Cartwright had experience of carrying out conversions on the Peugeot Boxer so that it became a minibus carrying 10 people.

31. A ten-seater minibus vehicle would, at the time of registration, be registered with the DVLA as an M2 category vehicle i.e. passenger vehicles comprising more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat, and having a maximum weight not exceeding 5,000kg. A vehicle’s classification can be changed from M1 to M2 after its initial registration with DVLA in circumstances where the vehicle has subsequently been converted to increase its seating capacity to 10 passengers or more.

32. Leaving aside the legal question which I shall consider below concerning which adaptations or modifications are relevant for statutory purposes, I accept the evidence of Mr Wickenden and Mr Shaw on these points.

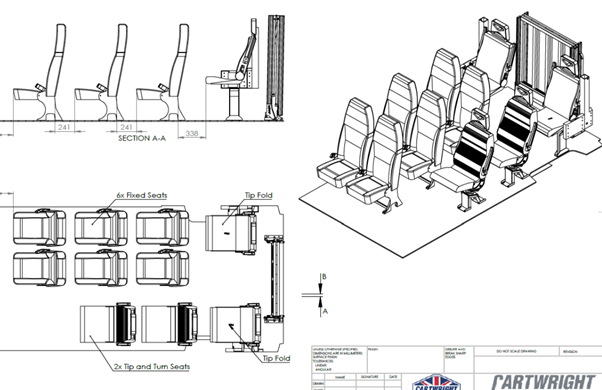

33. If the Appellant removed the ramp and replaced the tracking the vehicle capacity would be 10 seats - see photos and diagrams set out in Appendix 2 (taken from the exhibits to Mr Wickenden’s first witness statement). In that case, the vehicle would not breach any legal weight limit and the Appellant’s insurance policy would cover the supply of NEPTS in these reconfigured vehicles.

34. The Appellant also specified that Cartwright should remove the passenger seats from the front cab of its vehicles and replace them with wheelchair storage for 2 wheelchairs (the wheelchair pens): see the photos the photos set out at Appendix 3 (taken from the exhibits to Mr Wickenden’s first witness statement) which show “before” and “after” images. The Appellant carries 2 wheelchairs on-board should patients need to use them.

35. If the Appellant removed the wheelchair adaptions and storage from the vehicle and replaced it with standard seating, Mr Wickenden’s evidence, which I accept, was that the seating capacity would increase to 12 or 13 seats depending on whether a single or double front passenger seat was added. In fact, the holes for such seating were already pre-drilled. Removing the tracking and ramp from the vehicle would be a more time-consuming exercise but the adaptions were not irreversible.

36. If a stretcher was to be used in one of the NEPTS vehicles, it would result in the seating capacity of an eight-seater vehicle being reduced to six seats (including the driver) to make space for the stretcher - achieved by removing fixed seats or folding seats fitted to the vehicle, as appropriate. Fixing the stretcher within a NEPTS vehicle does not affect the vehicle’s capacity to carry two wheelchairs. The design of the vans that Cartwright convert make them very adaptable, and a standard van purchased by Cartwright from the manufacturers can be converted for several bespoke uses, including minibuses. The kerbside weight of an unconverted vehicle was approximately 2,000 kg. The weight of a converted NEPTS vehicle (excluding passengers) was 2,748 kg. The weight of:

(1) the ramp was 40-50 kg (including fixing brackets),

(2) the floor system (in excess of a standard plywood floor) was 60-65 kg,

(3) the wheelchair pen 16-20 kg,

(4) a small lightweight wheelchair was 30 kg,

(5) the winch 14-16 kg (including brackets and covers), and

(6) the locker storage for the wheelchair restraints was 2 kg.

37. The balance of the vehicle weight not attributable to wheelchair adaptations was 505-546 kg (i.e. 748 kg less 202-243 kg). The weight attributable to 10 passengers (assuming weight per passenger of 75 kg, which Mr Shaw stated to be the DVLA standard assumed weight) was calculated to be 750 kg. Although a small lightweight wheelchair weighed 30 kg, an electric wheelchair would weigh approximately 100 kg).

38. If 10 passengers were to be carried in a vehicle there would need to be two additional seats. The weight of those seats was unclear but the weight of two tip and fold seats would be between 40-60 kg heavier than that of two standard seats.

39. Thus the weight of the converted vehicle (2,748 kg) plus 10 passengers (750 kg) would be 3,498 kg. If two of the passengers were in wheelchairs (e.g. an electric wheelchair at 100 kg and the other in a standard wheelchair at 30 kg) the weight would be 3,628 kg.

40. The Appellant’s solicitors helpfully prepared a table which summarised a number of the above points:

|

Description |

Weight |

|

A. Vehicle kerb weight |

2000 kg |

|

B. Weight of converted vehicle |

2748 kg |

|

C. Wheelchair adaptations (as per the Appellant’s case): |

|

|

Ramp |

40-50 kg (including fixing brackets) |

|

Floor system |

128 kg[1] (being the difference between a plywood floor and the tracking floor system) |

|

Wheelchair pen |

16-20 kg |

|

Wheelchair pen: a small lightweight wheelchair |

30 kg |

|

Winch (including brackets and covers) |

14-16 kg |

|

2× Swivel seats (tip and fold) |

40-60 kg (in addition to the weight of 2× standard chairs) |

|

Locker storage for wheelchair restraints |

2 kg |

|

D. Balance of weight of adapted vehicle not attributed to wheelchair adaptations |

505-546 kg (i.e. 748 kg less 202-243 kg) |

|

E. Weight attributed to 10 passengers |

750 kg (75 kg per person) |

|

F. Weight of two wheelchairs |

130 kg (electric wheelchair: 100 kg and standard wheelchair: 30 kg) |

41. The floor system has become standard in the industry for NEPTS vehicles such as those used by the Appellant and other similar operators. It was easier to fit using than fixed points to secure a wheelchair. In Mr Shaw’s opinion, which I accept, the floor system using tracking was safer than having fixed points (i.e. effectively ring bolts) to secure a wheelchair in a vehicle.

42. Mr Wickenden, whose evidence on this point was not challenged, referred to a standard NHS contract. He said that NEPTS can and should encompass a wide range of vehicle types suitable to fulfil the needs of the service. As set out in the Service Specification for the specimen contract, the NEPTS provider’s vehicles must:

(1) be of a sufficient size to deliver the specified service. The fleet may be supplemented with short-term vehicles and sub-contractor vehicles to ensure the best value service and enable flexibility of capacity with minimum waste. The Appellant usually satisfied the NEPTS using its own vehicles and employed drivers but it did from time-to-time sub-contract work during particularly busy periods in accordance with the terms of the Contract;

(2) be equipped with satellite navigation and two-way radio or mobile telephone;

(3) be equipped with tracking services for service monitoring;

(4) be clearly marked with the provider’s logo and the national NHS logo and be readily identifiable as an NHS NEPTS vehicle; and

(5) be clean - internally and externally - including being decontaminated in line with infection prevention and control policies.

43. No specific service level requirements were stipulated in the specimen contract with regards to: the configuration of the vehicles; how many seats the vehicles must contain; or whether all vehicles are required to incorporate adaptations to cater for patients with special mobility requirements. That was left to the Appellant’s discretion. However, the specimen contract:

(1) required the Appellant to ensure that the vehicles used can safely cater for patients with a variety of mobility requirements, including walking patients, bariatric patients, HDU patients (if applicable to the service provision) and those that use wheelchairs and stretchers; and

(2) included an objective that the service is to optimise vehicle capacity and support a reduction in carbon emissions and the carbon footprint of patient journeys.

44. Mr Wickenden was cross-examined at length in relation to the video evidence exhibited to his witness statement. He maintained that it would be possible for a vehicle converted by Cartwright to seat 10 persons, but by so doing the weight limit of the vehicle of 3,500 kg would be breached. Ms Vicary, appearing for HMRC, challenged Mr Wickenden on this question. She suggested that by putting 10 seats in a converted vehicle, the Appellant’s crew could not adequately care for the type of passengers and patients that the Appellant was required to carry in their vehicles. She suggested to Mr Wickenden that the vehicle was too cramped with 10 seats to enable passengers to be carried in a dignified manner. Although the vehicles in the videos equipped with 10 seats were indeed more cramped, I do not consider that they were so cramped that the Appellant could not adequately carry 10 passengers (including the driver) bearing in mind the actual and intended uses of the vehicles.

45. Moreover, Mr Wickenden repeatedly made the point, with which I agree, that if wheelchairs and stretchers were not to be carried (in accordance with the statutory hypothesis in Note 4D(b)), the configuration of the seating would be entirely different. There would, for example, be no need for the bulky tip and fold seats - those seats were included on an NEPTS vehicle because of the need to carry wheelchairs: they folded back to make space for them. The tip and fold seats were, therefore, plainly installed to facilitate the accommodation of wheelchairs. His evidence in relation to the tip and fold seats was that they were there at the rear of the vehicle in order to enable, by being folded away, a wheelchair to be brought up the ramp and into the vehicle. His evidence in this respect was confirmed by Mr Shaw in cross-examination. I accept this evidence.

46. Mr Wickenden also explained, and I accept, that a large proportion of the Appellant’s passengers were able-bodied. In particular, he drew attention to renal dialysis patients (who often travel to hospital two or three times a week), chemotherapy patients and patient escorts. While some of the renal and chemotherapy patients had mobility issues, many did not. Obviously, the patient escorts did not have mobility issues. His criticism of HMRC’s assertion that 10 seats in the Appellant’s converted would be too cramped was that HMRC were over-estimating the mobility problems of the Appellant’s passengers, particularly when taking into account the statutory hypothesis that wheelchairs and stretchers in Note 4D(b) would not be carried (so that wheelchair-bound and stretcher patients would not be on board the vehicles). In my view, Mr Wickenden’s criticism was justified.

47. Mr Wickenden exhibited the Appellant’s vehicle fleet insurance policy. The policy provided cover for all vehicles operated by the Appellant. However, the policy would also cover its vehicles if the Unwin tracking system was removed and replaced with additional seating to increase the vehicle’s seating capacity to 10 or more seats.

the authorities

48. There are two authorities that have considered Item 4(a) Schedule 8 Group 8 VATA.

49. In Cirdan Sailing Trust v Customs and Excise Comrs [2005] EWHC 2999 (Ch), [2006] STC 185, the question was whether a boat, the ‘Duet’, fell within Item 4(a). The case did not involve wheelchair design or adaptation to the boat, so the court did not consider Note 4D. The issue was whether ‘Duet’ was “designed or adapted to carry not less than 10 passengers”. ‘Duet’ was capable of carrying 14 passengers on a day trip, but only had nine berths, two for crew and seven for passengers. Park J rejected the day trip figure as the applicable figure for the purpose of Item 4(a), holding as follows:

'[22] The area, however, where I respectfully differ from Mr McNicholas [counsel for the shipowner] is on his first proposition that Duet must be regarded as a ship designed or adapted to carry not less than ten passengers. That proposition is based on Mr Back's evidence that the vessel could carry 14 passengers on a day trip. However, it is also clear that the vessel could not carry 14 passengers, or at least could not do so in acceptable circumstances, on trips which involve one or more overnight periods. There are only nine berths on the boat, only seven of which are available for passengers. Thus Duet is a boat which it can be said is capable of carrying ten or more passengers on day trips, but is not realistically capable of carrying ten or more passengers on longer voyages which include overnight passages. I have to take that situation in conjunction with the feature that the normal use to which Duet has been put has not been a use for day trips. There may for all I know have been the occasional day trips, but the normal use has been for long voyages which typically include overnight passages.

[23] In my view the condition set out in item 4(a), which involves identifying the number of passengers a ship is designed or adapted to carry, must be applied in a sensible way by reference to the actual and anticipated ways in which the ship will be used. Further, where a vessel is equipped with a significant number of bunks it appears to me realistic to regard those bunks as giving an indication of what the vessel is designed or adapted to do. If a vessel was designed or adapted predominantly or solely for day trips it would be unlikely to have a considerable amount of its space occupied by bunks.”

50. In Davies (trading as Special Occasions/2XL Limos) v. Revenue and Customs Commissioners [2012] UKUT 130 (TCC), although the case did not concern ambulances, the Upper Tribunal considered the position under Item 4(a) of certain limousines, originally designed to carry not fewer than ten passengers, but subsequently adapted to carry only nine passengers. Item 4(a) itself was considered by the Upper Tribunal. It was argued at §4 before the Upper Tribunal that there were two distinct ways in which Item 4(a) might be satisfied:

“The first was that the vehicle had to have been designed to carry ten or more persons and, if so, it was then irrelevant that it might have been adapted to carry fewer persons. The second way in which the test could be satisfied was by showing that a vehicle initially designed to carry fewer passengers had been adapted, implicitly at the time the services were being provided, to carry ten or more persons. The supply of transport services would be zero-rated if either limb of the test was satisfied.”

51. At §§18, 22 and 23 the Upper Tribunal rejected this submission. The test, in Item 4(a), did not refer “just to the factual possibility that the vehicle might, at the point of the relevant supply of transport services, be in the configuration in which it was originally designed, or it might have been adapted for some different passenger carrying capability” (§18). Instead, the test looked at the configuration of the vehicle at the time the supplies in question were rendered (§22 and 23).

52. Both Cirdan and Davies were considered by the Upper Tribunal in Jigsaw Medical Services Ltd v HMRC [2018] UKUT 222 (TCC) in which I was a member of the Tribunal and Marcus Smith J was the presiding judge. In that case, the Upper Tribunal considered Note 4D in some detail when determining whether the supply of emergency ambulance services should be zero rated. The First-tier Tribunal (“FTT”) found that the emergency ambulances had front seats for the driver and passenger(s) and had three seats in the main rear compartment. There was also space for a stretcher which could be easily moved in and out of the ambulance via a ramp. In addition, there were fixings for a wheelchair so that a wheelchair could be securely fastened to the floor of the ambulance. The FTT had held [2017] UKFTT 537 (TC) at §37:

“In our view, the correct approach is to look at the vehicle itself and to determine whether or not that vehicle can, without complete rebuilding, be converted into a vehicle capable of carrying ten or more persons.”

53. Allowing HMRC’s appeal from the FTT’s decision, Upper Tribunal held that the supplies did not fall within the zero-rating provisions and analysed the relevant statutory provisions as follows:

“[22] We consider that the starting point for the purposes of construction is Item 4(a) and not Note 4D. The relevant statutory provision determining whether a supply is zero-rated or not is Item 4(a). Note 4D does not, of itself, determine zero-rating, but rather is a mandatory interpretive provision, requiring Item 4(a) to be read in a certain way.

[23] Accordingly, it is necessary to begin with Item 4(a), and to ask whether the vehicle in question is designed or adapted to carry not less than ten passengers. This test must be applied at the time the supplies in question were rendered; and (where variable numbers of passengers are capable of being carried) requires consideration of the actual and anticipated ways in which the vehicle is being used.

[24] Clearly, on this basis, the Supplies fall outside the ambit of Item 4(a). As Table 1 shows, none of the three vehicles used by Jigsaw could—at the time the Supplies were rendered—carry not less than ten passengers given their purpose. The maximum was seven or eight, depending on the vehicle.

[25] That, of course, is not the end of the story. It is necessary to read Item 4(a) in light of Note 4D. As to this:

(1) Note 4D(a) requires regard to be had to the question of whether the vehicle in question is designed or substantially and permanently adapted for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair.

(2) Unless this requirement is satisfied, consideration of Note 4D(b) does not arise at all. Here, of course, the requirement is met. All of the emergency vehicles constituting the Supplies were adapted for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair. Note 4D(b) is therefore engaged.

(3) Note 4D(b) asks whether, if the vehicle had not been designed or adapted for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair (the words 'not so designed or adapted' can refer to nothing else), the vehicle would be able to carry no less than ten persons.

(4) It is plain that this exercise (inevitably a hypothetical one) requires consideration of what might be achieved in terms of passenger capacity were the features enabling a wheelchair safely to be carried to be removed. In other words:

(a) One must first identify what was done to the vehicle to design it or adapt it for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair. We shall, as shorthand, refer to such design or adaptation as the 'wheelchair modifications'.

(b) Next, one must ask, supposing the wheelchair modifications were not undertaken, what could be done in terms of additional passenger capacity.

What is impermissible, in our judgment, is to postulate changes going beyond assuming that the wheelchair modifications were not undertaken. That seems to us to be inconsistent with the rule—articulated in Cirdan and Davies—that one looks at the vehicle as it actually was at the time the supplies in question were rendered and bearing in mind the actual and anticipated ways in which the vehicle is being used.

(5) To take a simple example: suppose a van has the capacity to carry 12 passengers provided there are no wheelchair modifications. The vehicle plainly falls within Item 4(a). Suppose, however, the consequence of making wheelchair modifications involves the removal of four seats. The capacity of the vehicle is now maximally nine (eight ordinary passenger seats plus one wheelchair passenger). Supposing the wheelchair modifications were not made, what would happen? Self-evidently, in this example, four ordinary passenger seats would be added back in, and the vehicle capacity would be 12.

(6) The short answer in the case of the Supplies is that no seating was actually taken out in order to configure an emergency vehicle with wheelchair modifications. All that was done was to add the restraints enabling a wheelchair safely to be carried.

[26] Such an approach is consistent with what we anticipate was the policy underlying Note 4D. This was to ensure that—in terms of zero-rating for VAT purposes, at least—the provider of transport supplies is not prejudiced when making wheelchair modifications.”

54. At §28 the Upper Tribunal considered the Explanatory Note mentioned at paragraph 11 above:

“An Explanatory Note is always admissible as an aid to understand the context of a statutory provision. Although we consider that the Explanatory Note in this case is consistent with our narrow construction of the statutory provisions, rather than the FTT's more expansive construction, we do not consider that, whatever its terms, an Explanatory Note can change an interpretation which, in our view, is so clearly mandated by the words used by Parliament.”

55. Finally, the FTT considered at §32 that its construction of Note 4D was consistent with the general principle that exemptions from VAT should be strictly construed.

Submissions and discussion

56. The burden of proof in this appeal lies on the Appellant and the standard of proof is the ordinary civil standard of the balance of probabilities.

57. I should make clear at this stage that HMRC, quite fairly, accepted that the phrase “safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair” included persons carried in the vehicle on a stretcher and in what follows references to persons in a wheelchair include references to persons on a stretcher.

58. In addition, HMRC accepted that the winch and the ramp were adaptations for the purposes of Note 4D. Therefore, the dispute before me, in so far as it related to questions of the weight of the modifications, really concerned questions of weight in relation to the floor system and the wheelchair pen. I should say, however, that as the evidence unfolded it became clear to me that the role of the two rear tip and fold seats were also wheelchair modifications for the reasons explained at paragraph 44 above. For simplicity, I shall refer to modifications and adaptations for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair, falling with Note 4D, as “wheelchair modifications”.

59. Moreover, I understood it to be common ground that:

(1) the floor system, the wheelchair pen, the winch and the ramp were “substantial” and “permanent” adaptations for the purposes of Note 4D (a) i.e. that they were not insubstantial or temporary adaptations even though they could, apparently, be relatively easily reversed; and

(2) the Appellant’s vehicles were actually used for the safe carriage of persons in wheelchairs, as well as by other passengers with either no or less significant mobility issues.

60. There was much discussion before me about the purpose of Item 4(a) and Note 4D. At one stage in her submissions, Ms Vicary argued that the purpose of these provisions was environmental in the sense that the purpose of Item 4(a) was to encourage public transport. Mrs Hall on the other hand argued that the defined social purpose (for the purposes of the Principal VAT Directive) of the provisions was to benefit wheelchair users.

61. In Jigsaw the Upper Tribunal at §26 said this about the policy behind the statutory provisions:

“[The policy underlying Note 4D] was to ensure that - in terms of zero-rating for VAT purposes, at least - the provider of transport supplies is not prejudiced when making wheelchair modifications.

62. In other words, a person supplying transport supplies should not be denied zero rating if the reason that they cannot transport at least 10 passengers is because of wheelchair modifications. Manifestly, the purpose is to encourage, or at least not discourage, the supply of transport services to persons in wheelchairs. The beneficiary of such a policy is not just the transport supplier or the NHS but also, indirectly, the wheelchair-bound passenger. I should also add that it seems to me that Parliament also lays emphasis on the need for safety and that part of the purpose of the legislation is to encourage the provision of safe transport for wheelchair users. The wheelchair modifications have to be those that are “substantially and permanently” adapted, not makeshift alterations.

63. Both Cirdan and Davies related to the interpretation of Item 4(a). They did not involve the carriage of wheelchairs and therefore did not consider Note 4D. Those cases stand as the authority for the proposition that in relation to Item 4(a) it is the actual or intended use or the configuration of the vehicle or vessel at the time the supplies are made that is relevant.

64. In Jigsaw the Upper Tribunal applied Cirdan and Davies to the interpretation of Note 4 D, saying at§25(b):

“What is impermissible, in our judgment, is to postulate changes going beyond assuming that the wheelchair modifications were not undertaken. That seems to us to be inconsistent with the rule - articulated in Cirdan and Davies - that one looks at the vehicle as it actually was at the time the supplies in question were rendered and bearing in mind the actual and anticipated ways in which the vehicle is being used.”

65. There is no doubt in my mind that the decision in Jigsaw is binding upon me, even though Mrs Hall argued that I was not bound by the decision because of the difference in the facts between the present case and those in Jigsaw.[2] It seems to me that §25 of Jigsaw contains the ratio or holding in that case. Equally, I have no doubt that it is correct, in interpreting Note 4D, to take account of the vehicle as it actually was at the time the supplies in question were rendered and bearing in mind the actual and anticipated ways in which the vehicle is being used. To hold otherwise would I think open the door to artificial and indeed absurd applications of Note 4D.

66. Note 4D requires me to hypothesise what the situation would be if the Appellant’s vehicles had not been adapted for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair bearing in mind that it is impermissible to go beyond the effect of the wheelchair modifications. In that hypothetical world, I am required to ask whether the Appellant’s vehicles would be “capable” of carrying no less than 10 persons.

67. Note 4D does not specify the type of modifications that might cause the carrying capacity of a vehicle to be reduced below 10 persons other than, in effect, it must be caused by a wheelchair modification. In particular, it does not require that seats must have been removed in order for wheelchair passengers to be carried.

68. I recognise that there are passages in Jigsaw, particularly §25(6), which may indicate that the removal of seating may be a relevant factor. However, I do not think that the Upper Tribunal intended the question whether seating had been taken out of a vehicle to be a legal test but rather one which was relevant on the facts of that case as to the actual and intended use of the emergency ambulances under consideration. Further, in §25(5) the Upper Tribunal gave a simple example involving a van that had the capacity to carry 12 people where four wheelchair modifications, were not carried out four passenger seats could be added back. But that was merely an example used in the face of the FTT’s expansive reasoning to the effect that the test was whether the vehicle, without complete rebuilding, could be converted into a vehicle capable of carrying 10 or more persons. The FTT’s test was wider than the statutory language permitted.

69. Moreover, confining the statutory hypothesis in Note 4D to situations where seats are taken out and then, notionally, added back would in many cases frustrate the purpose of the legislation. I would simply observe that seat removal is not a requirement that is mentioned in the legislation.

70. The evidence was clear that NEPTS ambulances, such as those operated by the Appellant, were the result of a conversion of a base panel van which was then customised to the requirements of the customer. As I understood it, this was standard practice in the industry because it was not possible to buy a ready-made NEPTS vehicle from a vehicle manufacturer. It is not a case of a pre-existing van with 10 or more existing seats being converted into an eight-seater ambulance. No seats are taken out in the conversion process (save perhaps in relation to the front row of seats replaced by the wheelchair pen). To deny zero rating in these circumstances - to make seat removal a pre-requisite - would mean that many or most customised NEPTS ambulances would fail the Note 4D test. This would be a strange and unrealistic conclusion.

71. In the present appeal Mrs Hall based her case “front and centre stage” on the question of weight. In short, her submission was that the weight of the wheelchair modifications was such that the Appellant’s vehicles could not carry 10 passengers and remain within the weight limitation of 3,500 kg for which the vehicle was designed. Without the wheelchair modifications, however, the vehicles were capable of carrying 10 passengers.

72. Ms Vicary, echoing the views expressed by HMRC in its review letter, argued that the purpose of Note 4D was to prevent zero rating being denied where the passenger transport service was provided in a vehicle that could carry less than 10 passengers only because of wheelchair adaptations. The evidence indicated that the vehicles were designed to carry a maximum of eight passengers (including the driver) and the wheelchair adaptations merely served to reduce this figure. In other words, the Appellant’s vehicles were designed to carry a maximum of eight people and if wheelchairs were to be carried some of those eight seats had to be folded out of the way so that the actual number of people that could be carried together with wheelchairs was less than eight to be carried, as the photographic evidence showed, some of the eight chairs had to be folded back (see Appendix 4).

73. To the extent that HMRC’s argument was based on a need for the Appellant to show that seats had been removed, I consider that argument to be misconceived for the reasons given above.

74. More generally, it seems to me that HMRC’s approach is incorrect. The fact that the conversion process assumed a maximum of eight passengers (including the driver) does not mean that the wheelchair modifications prevent the vehicle from carrying to be than 10 passengers. It does not engage with the Appellant’s argument that the reason that the maximum number of passengers in a converted vehicle was eight persons was because of the design weight limit of 3,500 kg. HMRC repeatedly put emphasis on the fact that the vehicles were intended only to carry a maximum of eight passengers. Put differently, I think HMRC are mistaken to assume that one must start with a 10 seater vehicle which is then reduced in passenger capacity by the wheelchair modifications so that if wheelchair passengers are not carried then the vehicle’s capacity or, more accurately capability, must revert to 10 persons. That is not the correct test.

75. Instead, consistent with Jigsaw, the test is whether, if the wheelchair modifications had not been made, the vehicle would be capable of carrying at least 10 persons, but taking account only of (and not going beyond) the wheelchair modifications that had been undertaken. That test has to be informed by the actual and intended use of the vehicle. Taking those two elements in turn, I have the following comments.

76. The statutory hypothesis to be applied by Note 4D must require consideration of whether changes to the existing or actual state of the vehicle can notionally be made. For example, additional seats will hypothetically have to be added, to the vehicle in order that it may “capable” of carrying not less than 10 passengers. The question is whether those changes can be made - is a vehicle capable of such an addition? I think it follows that, if other wheelchair modifications must be assumed not to have been made, hypothetical alterations to the vehicle which are directly related to those disregarded wheelchair modifications must also be contemplated. Thus, for example, if it is correct that the floor system is a wheelchair modification, as the Appellant contends, the assumption that the floor system should be disregarded does not mean that the vehicle is incapable of carrying no less than 10 passengers because it has no floor but asks rather whether the vehicle would be capable of being fitted with a floor[3] suitable for the carriage of no less than 10 passengers. To assume otherwise would frustrate the purpose of the legislation. It seems to me that that approach does not go beyond the statutory assumption that the wheelchair modifications were not undertaken but considers the capability of the vehicle absent those modifications, in accordance with Jigsaw.

77. Secondly, and possibly stating the obvious, in the hypothetical world of Note 4D(b), the actual and intended use of the vehicle must exclude the safe carriage of persons in wheelchairs. The use of the vehicle will otherwise be the same as the use to which the vehicles are currently put i.e. safely transporting the ambulance crew, sick and injured persons, and their escorts, for medical treatment and returning them to their homes. I also consider, in this context, that the multifunction capability of the vehicles was part of their actual or intended use.

78. In addition, Ms Vicary put forward two additional arguments which I was informed had only been advanced for the first time in her skeleton argument.

79. First, Ms Vicary submitted that the wheelchair pen was not a wheelchair modification in the sense that it was not an adaptation “for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair”. Thus, using the wheelchair pen to store wheelchairs for passengers who required wheelchair assistance to get to the ambulance but were then able to sit in one of the seats with the assistance of the crew, whilst their wheelchair was stored in the pen, was not a modification for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair - a test which contemplated that the wheelchair user would be carried in (“carriage”) their wheelchair during the journey.

80. In support of her submission Ms Vicary relied on the proposition that Item 4(a) and Note 4D must be strictly interpreted because they constitute an exemption to the general principle that VAT is chargeable on all supplies of goods and services for a consideration by a taxable person. However, as Ms Vicary recognised, a strict interpretation did not require an interpretation that defeated the intended effect of the exemption. For example, in C-334/14 De Fruytier EU:C:2015:437at §18 the CJEU said:

“The settled case-law further shows that the terms used to specify the exemptions in Article 13 of the Sixth Directive are to be interpreted strictly, since they constitute exceptions to the general principle that VAT is to be levied on all goods and services supplied for consideration by a taxable person. Nevertheless, the interpretation of those terms must be consistent with the objectives pursued by those exemptions and comply with the requirements of the principle of fiscal neutrality inherent in the common system of VAT. Thus, the requirement of strict interpretation does not mean that the terms used to specify the exemptions referred to in Article 13 must be construed in such a way as to deprive the exemptions of their intended effect.”

81. Ms Vicary submitted that the decision of the Court of Appeal in Expert Witness Institute v C & E Commissioners[2002] STC 42 at §17 should be understood in this light. Chadwick LJ said:

“It does not follow, however, that the court is required to give to the phrase 'aims of a civic nature' the most restricted, or most narrow, meaning that can be given to those words. A 'strict' construction is not to be equated, in this context, with a restricted construction. The court must recognise that it is for a supplier, whose supplies would otherwise be taxable, to establish that it comes within the exemption, so that if the court is left in doubt whether a fair interpretation of the words of the exemption covers the supplies in question, the claim to the exemption must be rejected. But the court is not required to reject a claim which does come within a fair interpretation of the words of the exemption because there is another, more restricted, meaning of the words which would exclude the supplies in question.”

82. Ms Vicary submitted that this passage could not properly be relied upon to argue that of two possible interpretations that are “fair” and that meet the intended effect of the exemption, the more restrictive interpretation was not also the right interpretation. To do so would deprive the requirement for a “strict” interpretation of meaning.

83. I reject those submissions. It seems to me that, as I have said, the purpose of Note 4D is to ensure that the providers of transport services are not prejudiced by the fact that their vehicles are incapable of carrying at least 10 passengers because of wheelchair modifications. There is no doubt on the evidence that the passenger-carrying capability of the Appellant’s vehicles was reduced because of the wheelchair pen - the front seats were removed. The statutory wording concerns adaptations “for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair”. In my view, the carriage of a person in a wheelchair comprehends the ambulance crew wheeling a passenger up to or into (using the ramp) the ambulance, seating the passenger in a chair and stowing the wheelchair in the wheelchair pen. In other words, the “safe carriage a person in a wheelchair” involves a whole journey from the patient’s front door into the medical facility and vice versa. A person “in a wheelchair” is a descriptive phrase but does not, to my mind, require one to assume that that person must always be seated in the wheelchair at all stages of the journey. It seems to me that it is perfectly possible for a person in a wheelchair to be safely carried in the Appellant’s vehicles by being seated in the ambulance and the wheelchair, for safety purposes, being safely stowed in the wheelchair pen.

84. HMRC’s narrower construction of the phrase “for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair” seems to me to be a highly restrictive interpretation and one which defeats the purpose of the Note 4D. HMRC’s interpretation discourages the providers of non-emergency ambulance transport from making provision for persons in wheelchairs who are sufficiently able-bodied decision to use an ordinary seat during the journey but require a wheelchair at each end of the journey. This, in my view, is the type of restricted interpretation of which Chadwick LJ spoke in Expert Witness Institute and one which significantly deprives Note 4D of its intended effect.

85. Even if I am wrong on this point, I think that Ms Vicary’s argument fails on the facts. True it is that the wheelchair pen is used in part to store wheelchairs for passengers who need a wheelchair to get to the ambulance but who are able to sit in an ordinary seat during the journey. But that is not the only use of the wheelchair pen. Mr Wickenden’s evidence was that some patients, particularly chemotherapy patients, were perfectly able-bodied on the outward journey but were so affected by their treatment that they need to be accommodated in a wheelchair or a stretcher on the return journey. Mr Wickenden made similar comments about some patients requiring blood transfusions. This point was recognised in paragraph 35) of the Agreed Statement of Facts.

86. It is, therefore, hard to see how the use of the wheelchair pen, providing safe stowage for wheelchairs on the outward journey ready for their use, if needed, on the return journey, can fail to be an adaptation for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair.

87. Secondly, Ms Vicary argued that the wheelchair modifications, particularly the floor system, did not have the “sole or predominant purpose” of ensuring the safe carriage of persons in wheelchairs, but instead served a number of different purposes. In that sense, Ms Vicary argued that the wheelchair modifications were not, in the statutory language, “for” the safe carriage of persons in wheelchairs. The floor system served not only to secure wheelchairs and stretchers but also secured a number of the seats in the 8+2 configuration and allowed those seats to be removed or moved backwards and forwards. The purpose of the flooring system, in Ms Vicary’s submission, was to allow the Appellant to use vehicles that had the maximum degree of flexibility as required by its contracts with the NHS rather than solely for the safe carriage of a person in a wheelchair.

88. In support of her submission Ms Vicary referred to Nestlé UK Ltd v HMRC [2018] STC 575, §65-66; HMRC Wetheralds Construction Ltd [2018] UKUT 173 (TCC) at §31 as further considered in Greenspace Limited v HMRC [2021] UKUT 290 (TCC) at §16. With respect, I did not find citations concerning the use of the word “for” in entirely different statutory contexts (fruit-flavoured powdered beverages and insulation for conservatory roofs), albeit within Group 8, of assistance. Mrs Hall was able to cite a number of instances in Group 8 where if Parliament wished to indicate exclusivity of purpose it was able to use appropriate language to do so (e.g. by the use of the word “solely”).

89. I reject Ms Vicary’s submission on this point. There is no need to read the words “solely or predominantly” into the statutory language. The floor system, particularly the tracking, was certainly used for securing wheelchairs and stretchers in a safe manner and was intended to be so used. Mr Shaw’s evidence, which I accept, was that the use of the tracking rails embedded in the floor system was safer than the use of fixed point fastenings (e.g. ring bolts) and was now the industry standard. In this context, it would seem strange if one of the statutory purposes (“safe carriage”) was thwarted by reading the words “solely or predominantly” into the legislation, denying zero rating, at least in part, because a safer system of securing wheelchairs was used. Looking at the evidence overall, it is clear that the floor system provided considerable flexibility in accommodating seats, wheelchairs and stretchers a purpose which seems to me entirely consistent with the statutory objective. I see no reason to give the statutory wording the highly restrictive meaning for which HMRC contend.

90. Finally, Ms Vicary argued that the wheelchair modifications undertaken by the Appellant were not the reason for its vehicles being configured to carry less than 10 persons. At 36) of the Agreed Statement of Facts it was apparent, Ms Vicary submitted, that the Appellant chose to configure its vehicles in five main specifications to enable it to cater for the various requirements of its contracts and the high levels of support required by its passengers. It was those requirements, both contractual and practical, which prohibited the Appellant from simply configuring its vehicles to carry no less than 10 persons. The Appellant would be unable to cater for the needs of its patients if it filled its vehicles with the maximum number of seats. The actual and anticipated use of the Appellant’s vehicles demanded that there should be sufficient space to enable the needs of its patients to be met and this was incompatible with the carriage of no less than 10 persons.

91. I think I can deal with this argument relatively briefly. It was manifestly the case that one of the purposes of the Appellant in converting its vehicles, adding the wheelchair modifications, was to enable passengers in wheelchairs to be safely transported. As the evidence showed, the exact make-up of passengers for a journey was settled very shortly before the journey commenced. There was, therefore, a commercial need for flexibility with seating arrangements and the capacity to accommodate wheelchairs. Certainly, there was a contractual requirement for flexibility in seating arrangements but there was also a practical necessity for flexibility in order to provide transport for wheelchair users. There is no doubt that such flexibility benefited (and was intended to benefit) not only the NHS but also its patients i.e. the Appellant’s passengers. The whole purpose of Item 4(a) and Item 4D was to encourage companies like the Appellant to provide transport for wheelchair users for the benefit not just of the NHS but also of its patients. HMRC’s argument seems to me to be completely uncommercial and frankly unrealistic. The flexibility and adaptability required for NEPTS vehicles as part of the actual and intended use of the vehicles. To deny zero rating on the basis that this flexibility was one of the Appellant’s purposes seems to me to run contrary to the very purpose of the provision.

92. I have, therefore, rejected HMRC’s main arguments. It is still necessary, however, to consider whether the Appellant has made good its case in relation to weight. Mrs Hall recognised this argument had never been previously advanced.

93. Mrs Hall submitted that the weight of a vehicle with wheelchair modifications was such that it could not lawfully carry 10 passengers because it would exceed the 3,500 kg weight limit of the vehicle[4] and the insurance for the vehicle would be invalidated. The kerb weight of a vehicle was approximately 2000 kg and its converted weight (including the wheelchair pen, the ramp, the floor system and the winch) was 2748 kg. If the weight of 10 passengers (at 75 kg per passenger) was added the total weight would be 3498 kg i.e. too close for comfort to the maximum limit, particularly if heavier wheelchairs had to be accommodated. If the wheelchair modifications (the floor system, the winch, the ramp and the wheelchair pen) were removed the weight would be decreased by between 202-243 kg (ramp 40-50 kg, floor system 60-65 kg, wheelchair pen 16-20 kg, lightweight wheelchair 30 kg, winch 14-16 kg, tip and fold seats 40-60 kg and locker 2 kg). However, it appears that the Appellant forgot that it would be necessary to add two additional standard seats (if 10 passengers were to be carried) although it was unclear from the evidence how much those seats would weigh[5], but it would appear to be considerably less than 200 kg. Indeed, Mr Shaw’s evidence, which I accept, was that the Appellant’s vehicles without the wheelchair adaptions could be driven with ten passengers (including the driver) comfortably within the vehicle’s maximum weight allowance of 3,500kg. Therefore, in my view, if the wheelchair modifications were disregarded, the vehicles would be able to carry 10 passengers (including the driver) without breaching the 3,500 kg weight limit.

94. Accordingly, I have come to the conclusion that the Appellant’s vehicles fall within Item 4(a) by virtue of Note 4D and that consequently the services supplied by the Appellant by means of these vehicles are zero rated. I therefore allow this appeal.

Right to apply for permission to appeal

95. This document contains full findings of fact and reasons for the decision. Any party dissatisfied with this decision has a right to apply for permission to appeal against it pursuant to Rule 39 of the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Tax Chamber) Rules 2009. The application must be received by this Tribunal not later than 56 days after this decision is sent to that party. The parties are referred to “Guidance to accompany a Decision from the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber)” which accompanies and forms part of this decision notice.

GUY BRANNAN

TRIBUNAL JUDGE

Release date: 25 AUGUST 2022

APPENDIX 1

APPENDIX 2

APPENDIX 3

APPENDIX 4

[1] Not in the original Table, but inserted from the evidence of Mr Shaw.

[2] although Mrs Hall argued that her case was consistent with the reasoning in Jigsaw.

[3] Mr Shaw’s evidence was that a standard plywood floor would be fitted.

[4] Mrs Hall referred to this as a DVLA weight limit, but it seems from the evidence of Mr Shaw to have been the maximum legal weight limit for this particular kind of vehicle. As far as I could ascertain, the weight limit of 3,500 kg was not a category M1 requirement. Mr Wickenden’s evidence on this point was consistent with Mr Shaw’s.

[5] Ms Vicary estimated standard seats to weigh 10 kg, but I think 20 kg would be a more realistic estimate.