Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

First-tier Tribunal (Tax)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> First-tier Tribunal (Tax) >> ACAMAR PRODUCTIONS LLP v Revenue & Customs (CORPORATION TAX - claims for losses in two partnership tax returns of an LLP) [2022] UKFTT 74 (TC) (17 February 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2022/TC08405.html

Cite as: [2022] UKFTT 74 (TC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

[2022] UKFTT 74 (TC)

TC 08405/V

CORPORATION TAX - claims for losses in two partnership tax returns of an LLP - whether the LLP was carrying on a trade - no, because, properly construed, the LLP’s activities amounted to investment and not trading - whether the LLP had a view to profit - no, because the LLP was indifferent as to whether or not it made a profit - whether the accounts of the LLP in its first period of account were prepared in accordance with GAAP - no, because the accounts did not properly record the substance of the relevant transaction - whether, assuming that the LLP was carrying on a trade and the accounts were prepared in accordance with GAAP, the losses shown in those accounts would have been deductible as a trading expense - no, because, even on the assumption that the LLP was trading, the expense in question would not have been wholly and exclusively incurred for trading purposes and would have been capital in nature - whether, on the assumption that the LLP was trading, certain expenses incurred in a later period of account in which a loss arose would have been deductible as trading expenses - certain of those expenses were deductible but others were not because they had not been wholly and exclusively incurred for trading purposes and the fact that they were not deductible meant that no loss would have arisen in the later period of account - appeal dismissed

|

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL TAX CHAMBER |

|

Appeal number: TC/2018/00414 |

BETWEEN

|

|

ACAMAR PRODUCTIONS LLP |

Appellant |

-and-

|

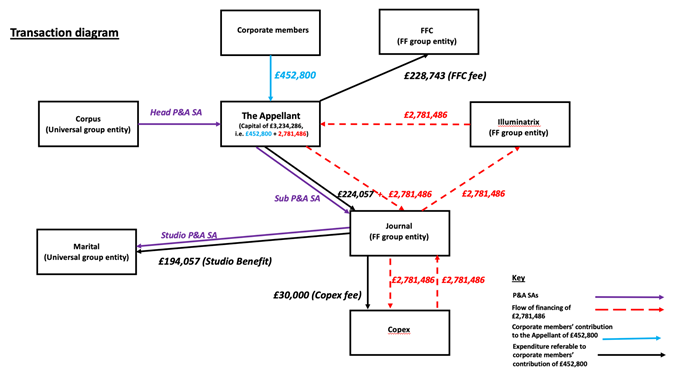

|

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HER MAJESTY’S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS |

Respondents |

|

TRIBUNAL: |

JUDGE TONY BEARE MR JULIAN STAFFORD |

The hearing took place on 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19 and 20 January 2022. With the consent of the parties, the form of the hearing was by way of a video hearing on Teams.

A face-to-face hearing was not held because of the COVID 19 pandemic and because the matters at issue were considered appropriate to be dealt with by way of a video hearing.

Prior notice of the hearing had been published on the gov.uk website, with information about how representatives of the media or members of the public could apply to join the hearing remotely in order to observe the proceedings. As such, the hearing was held in public.

The documents to which we were referred included four documents bundles (together, the “DB”) and three authorities bundles. Together, these contained the written evidence, legislation and case law relevant to the hearing.

Mr James Ramsden QC and Mr Sam Brodsky, instructed by RPC, for the Appellant

Ms Elizabeth Wilson QC and Mr Nicholas Macklam, instructed by the General Counsel and Solicitor to HM Revenue and Customs, for the Respondents

|

Heading |

page |

|

introduction |

1 |

|

background |

1 |

|

the issues |

2 |

|

the transaction |

3 |

|

the evidence |

7 |

|

the written evidence |

7 |

|

pre-transaction - the im and the related presentation to corporate members |

7 |

|

pre-transaction - the investment committee and the ic submission |

8 |

|

the transaction documents |

9 |

|

post-transaction documents |

17 |

|

the witness evidence |

18 |

|

findings of fact |

22 |

|

introduction |

22 |

|

the findings of fact |

25 |

|

discussion |

38 |

|

introduction |

38 |

|

the trade issue |

38 |

|

the case law |

38 |

|

conclusion |

39 |

|

the view to profit issue |

48 |

|

the case law |

48 |

|

conclusion |

49 |

|

the gaap issue |

52 |

|

the views of the experts |

52 |

|

conclusion |

59 |

|

the deductibility issue |

61 |

|

introduction |

61 |

|

wholly and exclusively - the case law |

63 |

|

wholly and exclusively – conclusion |

63 |

|

the tax year 2012/13 |

63 |

|

the tax year 2014/15 |

66 |

|

capital - the case law |

66 |

|

capital - conclusion |

68 |

|

conclusion |

71 |

|

right to apply for permission to appeal |

71 |

|

appendix |

72 |

DECISION

Introduction

1. This decision relates to an appeal against two closure notices, each dated 14 July 2017, amending the partnership tax returns of the Appellant in relation to the tax year ending 5 April 2013 (the “tax year 2012/13”) and the tax year ending 5 April 2015 (the “tax year 2014/15”). Each of those partnership tax returns disclosed a trading loss - £3,234,286 in respect of the tax year 2012/2013 and £45 in respect of the tax year 2014/2015. In each case, the trading loss disclosed in the relevant partnership tax return was allocated to the members of the Appellant in accordance with the terms of the document governing the Appellant. Each closure notice amended the relevant partnership tax return in such a way as to reduce the relevant loss to nil.

background

2. The Appellant was incorporated on 6 September 2012 as a limited liability partnership (an “LLP”) under the provisions of the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 (the “LLPA”). It was incorporated by Future Films group (the “FF group”) for the purpose of raising finance from investors wishing to invest in the film industry and entering into transactions relating to the film the Les Miserables. The latter was to be released by the Universal Studios group (the “Universal group” or the “studio”) shortly after the Appellant was formed.

3. On incorporation, the Appellant had two designated members - Future Films Corporate Productions Limited (“FFP”) and Prosper Capital Management Limited (“Prosper Management” and, together with FFP, the “Designated Members”).

4. Pursuant to Section 1 of the LLPA, an LLP is a body corporate with legal personality which is separate from that of its members.

5. Notwithstanding that that is the position as a matter of general law, Section 863 of the Income Tax (Trading and Other Income) Act 2005 (the “ITTOIA”) provides that, if an LLP carries on a trade or business “with a view to profit”, then, for income tax purposes, all of the activities of the LLP are treated as carried on in partnership by its members (and not by the LLP as such), anything done by, to or in relation to, the LLP for the purposes of, or in connection with, any of its activities is treated as done by, to or in relation to, the members as partners, and the property of the LLP is treated as held by the members as partnership property. Section 1273 of the Corporation Tax Act 2009 (the “CTA 2009”) makes an equivalent provision in relation to corporation tax. It follows from this that, as long as an LLP is carrying on a trade or business with a view to profit, it is effectively indistinguishable from a general partnership for income tax and corporation tax purposes in that it is effectively transparent for those purposes.

6. Section 25 of the ITTOIA provides that the profits of a trade must be calculated in accordance with “generally accepted accounting practice” as defined in Section 997 of the Income Tax Act 2007 (the “ITA”) (“GAAP”), subject to any adjustment required or authorised by law in calculating profits for corporation tax purposes. Section 26 of the ITTOIA provides that the same rules apply in calculating losses of a trade for income tax purposes as apply in calculating profits of a trade for income tax purposes, subject to any express provision to the contrary. Sections 46 and 47 of the CTA 2009 (and Section 1127 of the Corporation Tax Act 2010 (the “CTA 2010”)) contain equivalent provisions for corporation tax purposes.

7. For this purpose, GAAP is defined in Section 997 of the ITA and Section 1127 of the CTA 2010 as meaning, in relation to a company or other entity which does not prepare accounts in accordance with international accounting standards (“IAS accounts”):

(1) generally accepted accounting practice in relation to accounts of UK companies (other than IAS accounts) that are intended to give a true and fair view; and

(2) to have the same meaning in relation to individuals, entities which are not companies and companies other than UK companies.

8. Two of the adjustments required by law in calculating profits for income tax and corporation tax purposes are:

(1) Section 33 of the ITTOIA (and Section 53 of the CTA 2009), which provide that, in calculating the profits of a trade, no deduction is allowed for items of a capital nature; and

(2) Section 34 of the ITTOIA (and Section 54 of the CTA 2009), which provide that, in calculating the profits of a trade, no deduction is allowed for expenses not incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade and losses not connected with or arising out of the trade. In each case, the relevant provision goes on to provide that, if an expense is incurred for more than one purpose, the section does not prohibit a deduction for an identifiable part or identifiable proportion of the expense which is incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade.

9. As we outline in further detail in describing the transaction which is relevant to this appeal in paragraphs 18 to 22 below, the Appellant raised capital from various sources and entered into contracts in relation to the film. Those, and related, transactions gave rise to significant losses in the Appellant’s accounts. If the activities of the Appellant in entering into those transactions amounted to a trade with a view to profit, the accounts of the Appellant complied with GAAP, and the expenditure giving rise to the losses shown in those accounts was revenue (as opposed to capital) in nature and was incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade, then the losses shown in the Appellant’s accounts fell to be treated as trading losses made by the members of the Appellant.

the issues

10. The above means that, in order for the trading loss disclosed in each partnership tax return of the Appellant which is the subject of this appeal to be treated as a trading loss of the members of the Appellant:

(1) the Appellant must have been carrying on a trade during the tax year to which that partnership tax return related;

(2) the Appellant’s activities during that tax year must have been being conducted with a view to profit;

(3) the accounts for the period of account of the Appellant which formed the basis period for that tax year must have complied with GAAP; and

(4) the expenditure giving rise to the trading loss must have met the conditions to qualify as trading expenses. In particular, they must have had a revenue (as opposed to a capital) nature and they must have been wholly and exclusively incurred for the purposes of the trade.

11. The Respondents submit that the closure notices are correct because:

(1) in the case of the partnership tax return for the tax year 2012/13, the Appellant fails on all four of those grounds; and

(2) in the case of the partnership tax return for the tax year 2014/15, the Appellant fails on the first two and the fourth of those grounds. (Given the quantum of the loss disclosed in the partnership tax return for the tax year 2014/15, the Respondents have not taken issue with the Appellant in relation to whether or not the accounts for the period of account which formed the basis period for that tax year complied with GAAP.)

12. The Appellant disagrees.

13. As a result, the four issues which are in dispute in this appeal are as follows:

(1) did the Appellant’s activities during the relevant tax years amount to a trade (the “Trade Issue”)?

(2) did the Appellant carry on its activities during the relevant tax years, whether or not they amounted to a trade, “with a view to profit” (the “View to Profit Issue”)?

(3) did the Appellant’s accounts for its period of account ending 31 October 2012 - the basis period for the tax year 2012/2013 - comply with GAAP (the “GAAP Issue”)? and

(4) assuming that there are affirmative answers to each of the first three issues, did the expenditure for which relief is being claimed qualify as deductible trading expenditure (the “Deductibility Issue”)?

14. The GAAP Issue is a question of fact whereas the other three issues are mixed questions of fact and law.

15. It is common ground that the burden of proof in relation to each of the issues is on the Appellant. In other words, the Appellant needs to establish that, on the balance of probabilities, its position on each issue is correct and the Respondents were wrong to reduce the losses in respect of each partnership tax return to nil. Having said that, as will become clear from the terms of this decision, the answers to the issues in this case are in our view so clear that the question of which party has the burden of proof is moot.

16. This is a somewhat unusual case. So far as we have been able to determine, there is absolutely no disagreement between the parties as to:

(1) the proper construction of the relevant legislation;

(2) the proper interpretation of the relevant case law; or

(3) the transactions to which the Appellant was party.

17. The areas of disagreement are solely as to:

(1) the conclusions of fact which should properly be drawn from the transactions to which the Appellant was party;

(2) the application of the law to those conclusions of fact; and

(3) whether or not the accounting treatment adopted by the Appellant in respect of its period of account ending 31 October 2012 complied with GAAP.

the transaction

18. The transaction involved the following steps:

(1) on 25 September 2012, the Appellant issued an information memorandum (the “IM”) to potential investors in the Appellant;

(2) on 27 October 2012, Copex International Credit PCC, a bank unrelated to either the FF group or the Universal group, entered into a loan agreement with a member of the FF group named Journal Productions Limited (“Journal”) (the “Copex Loan Agreement”) pursuant to which, in return for an arrangement fee of £30,000, Copex granted Journal an interest-free loan facility of up to £3,000,000 for the sole purpose of enabling Journal to make a loan to another member of the FF group, Illuminatrix (ACA) Limited (“Illuminatrix”). The loan made by Copex under the Copex Loan Agreement was required to be repaid on the same day as the funds were drawn down;

(3) on 29 October 2012:

(a) a partnership deed was executed by the Appellant, the Designated Members and Illuminatrix (the “Partnership Deed”). The Partnership Deed provided that the Appellant was to carry on the trade of providing services in respect of one or more projects and Illuminatrix agreed to be (and was accepted as) a member of the Appellant;

(b) the six companies which had agreed to become investors in the Appellant as corporate members (the “corporate members” and each individually a “corporate member”) executed a deed of adherence and a power of attorney pursuant to which they became members of the Appellant;

(c) the Appellant entered into a consultancy agreement with another member of the FF group, Future Films Consultancy Limited (“FFC”) (the “Consultancy Agreement”) pursuant to which the Appellant engaged FFC to provide consultancy services to the Appellant in return for:

(i) an up-front fee equal to 8% of the aggregate capital contributions received by the Appellant; and

(ii) an annual fee thereafter;

(d) the Appellant, FFC and Prosper Capital LLP (“Prosper Capital”) entered into a sponsor and operator agreement (the “Sponsor and Operator Agreement”) pursuant to which the Appellant engaged Prosper Capital to provide sponsorship and operator services to the Appellant in return for a fee of 0.25% of the total partnership capital plus specified fees and commissions which were payable by Prosper Capital. We propose to say no more in this decision about the Sponsor and Operator Agreement as it has no bearing on the issues with which we are concerned;

(e) a member of the Universal group named Marital Assets LLC (“Marital”) entered into a distribution services agreement with another member of the FF group named TFFG Services Limited (“TFFG”) (the “Distribution Services Agreement”) pursuant to which Marital engaged TFFG to provide services to be mutually agreed in relation to the distribution arrangements for Les Miserables until completion and delivery of the film in return for a fee of £1. We propose to say no more in this decision about the Distribution Services Agreement. This is because:

(i) it was expressed on its face to end on “completion and delivery of the film”, and it was common ground at the hearing that the film had been completed and delivered by the day when the agreement was executed;

(ii) it was expressed as an agreement to provide services to be mutually agreed and no evidence was provided to us to show that any such services were so mutually agreed. It was therefore no more than an agreement to agree; and

(iii) neither Mr Stephen Margolis, the sole witness of fact, nor either party’s counsel, was able to shed any light on the role which the agreement was intended to play, or did in fact play, in the transaction. We have therefore concluded that it too has no bearing on the issues with which we are concerned;

(f) Journal and Illuminatrix entered into a loan agreement (the “Journal Loan Agreement”) pursuant to which Journal agreed to make a loan of £2,781,486 to Illuminatrix for the sole purpose of enabling Illuminatrix to make a capital contribution to the Appellant;

(g) a second company in the Universal group, Corpus Vivos Productions LLC (“Corpus”), and the Appellant entered into a head print and advertising services agreement (the “Head P&A SA”) pursuant to which the Appellant agreed to provide print and advertising services (“P&A services”) to Corpus in respect of Les Miserables in return for an upfront fee of £15 and future fees which were contingent on the success of the film and dependent on a formula (the “Waterfall”);

(h) the Appellant and Journal entered into a sub P&A services agreement (the “Sub P&A SA”) pursuant to which Journal agreed to provide P&A services to the Appellant in respect of Les Miserables in return for an upfront fee of £3,005,543; and

(i) Journal and Marital entered into a studio P&A services agreement (the “Studio P&A SA” and, together with the Head P&A SA and the Sub P&A SA, the “P&A SAs” and, individually, a “P&A SA”) pursuant to which Marital agreed to provide P&A services to Journal in respect of Les Miserables in return for an upfront fee of £2,957,543, which was to be discharged by the payment by Journal to Marital of £194,057 in cash and the assignment by Journal to Marital of its rights in respect of the loan of £2,781,486 made to Illuminatrix under the Journal Loan Agreement. (In the rest of this decision, we will refer to the £194,057 cash payment to Marital under the Studio P&A SA as the “Studio Benefit”);

(4) on 30 October 2012:

(a) Journal made a drawing of £2,781,486 from Copex under the Copex Loan Agreement;

(b) Journal made a loan of £2,781,486 to Illuminatrix under the Journal Loan Agreement;

(c) Illuminatrix contributed £2,781,486 to the Appellant as a capital contribution;

(d) the companies which had agreed to become corporate members contributed £452,800 in aggregate to the Appellant as capital contributions. The aggregate amount of capital contributed to the Appellant was therefore £3,234,286 (£2,781,486 plus £452,800);

(e) the Appellant paid the upfront fee of £3,005,543 to Journal under the Sub P&A SA;

(f) the Appellant paid a fee of £228,743 to FFC under the Consultancy Agreement. (This was not strictly in accordance with the terms of the Consultancy Agreement which, as noted in paragraph 18(3)(c) above, required the Appellant to pay to FFC, as the initial fee under the Consultancy Agreement, an amount equal to 8% of the aggregate capital contributions received by the Appellant. This formula would have produced some £30,000 more than was actually paid but, as nothing turns on this discrepancy for the purposes of this decision, we propose to say no more about it);

(g) Journal repaid the drawing of £2,781,486 from Copex under the Copex Loan Agreement and paid the arrangement fee of £30,000 which was due under that agreement; and

(h) Journal discharged the up-front fee of £2,957,543 which was due to Marital under the Studio P&A SA by paying the Studio Benefit to Marital and assigning to Marital its rights in respect of the loan of £2,781,486 made to Illuminatrix under the Journal Loan Agreement.

19. Thus, by 31 October 2012, which was the final day of the period of account of the Appellant which is the basis period for the tax year 2012/2013:

(1) the Appellant had:

(a) received £3,234,286 by way of capital contributions; and

(b) paid £3,005,543 of that amount to Journal and £228,743 of that amount to FFC;

(2) Journal had:

(a) drawn down a loan 2,781,486 from Copex under the Copex Loan Agreement;

(b) made a loan of £2,781,486 to Illuminatrix under the Journal Loan Agreement;

(c) received £3,005,543 from the Appellant under the Sub P&A SA;

(d) repaid, on the same day that it was drawn down, the loan of £2,781,486 from Copex under the Copex Loan Agreement;

(e) paid an arrangement fee of £30,000 to Copex under the Copex Loan Agreement;

(f) paid £194,057 (ie the Studio Benefit) to Marital; and

(g) assigned to Marital its rights in respect of the loan of £2,781,486 made to Illuminatrix under the Journal Loan Agreement; and

(3) Illuminatrix had:

(a) borrowed £2,781,486 from Journal under the Journal Loan Agreement;

(b) contributed capital of £2,781,486 to the Appellant; and

(c) acceded to the assignment by Journal to Marital of Journal’s rights in respect of the loan of £2,781,486 made to Illuminatrix under the Journal Loan Agreement.

20. It is common ground that the steps described above were all conceived and implemented as a single integrated transaction, by which we mean that there was no prospect that one of the steps comprising the transaction would have been implemented without the others. The transaction documents cross-referred to each other and were intended to take effect at the same time. They were, in effect, a single package.

21. To facilitate the reader’s understanding of the transaction described above, we have included, in the Appendix to this decision, a diagram of the structure following the above steps.

22. Further detail in relation to the documents which implemented the transaction is set out in paragraphs 28 to 41 below.

the evidence

23. The evidence in this appeal took the form of the written evidence in the DB and witness evidence.

The written evidence

24. The written evidence which we considered included:

(1) certain pre-transaction documents such as the IM, the related presentation to prospective corporate members, the presentation to an investment committee of the FF group (the “Investment Committee”) of a submission detailing possible outcomes of the transaction based on prior comparators (the “IC Submission”) and the minutes of the ensuing meeting of the Investment Committee;

(2) the documents implementing the transaction; and

(3) certain related post-transaction documents.

Pre-transaction - the IM and the related presentation to corporate members

25. The logical starting point in this regard is the pre-transaction documents.

26. The relevant points arising out of the IM and the related presentation to prospective corporate members are as follows:

(1) the section in the IM headed “V. ARRANGEMENT: KEY DETAILS - Commercial Structure” highlighted to prospective members:

(a) the gearing model which was to be used in the transaction, which meant that, for every 14 of cash invested in the Appellant by a corporate member, an additional 86 would be provided to the Appellant by a member of the FF group (in this case Illuminatrix); and

(b) the fact that the Appellant intended to conduct its business “over a minimum 5-year period”;

(2) the section in the IM headed “IX. PROJECT SELECTION” explained that the selection criteria for choosing a film would include “[targeted] returns of c.25% to be earned on provision of services”;

(3) the section in the IM headed “XI ACTIVITIES OF THE PARTNERSHIP ONCE A PROJECT IS COMPLETE - Profits and Losses” explained how:

(a) in the initial period of account of the Appellant, the corporate members in aggregate would be entitled to 90% of the profits and losses in the Appellant and the FF group member would be entitled to 10% of those profits and losses but that, in subsequent periods of account of the Appellant:

(i) the profits and losses would be shared in proportion to capital contributions - which is to say, 14% to the corporate members in aggregate and 86% to the FF group member - until the FF group member had received back its capital contribution; and

(ii) thereafter, the profits and losses would be shared as to 50% to the corporate members in aggregate and 50% to the FF group member; and

(b) the Appellant intended to apply any revenues to other projects and did not expect to make distributions to members prior to the winding up of the Appellant;

(4) the section in the IM headed “XII FINANCIAL ILLUSTRATION - Corporate Member Cash Flow and Project Revenues (£s)” contained a table showing how a corporate member investing in the Appellant would fare economically in comparison to its position in the absence of any such investment. The table took no account of any project revenues but simply focused on the tax advantage which the corporate member could anticipate obtaining if it were to invest in the Appellant. It highlighted that, assuming a 25% corporation tax rate, the corporate member could expect to realise additional cash of £85,000 on an investment into the Appellant of £140,000 (because of the gearing provided by the FF group member) assuming that GAAP required the entire cost of providing the services to be written off in the first period of account of the Appellant;

(5) the presentation related to the IM contained similar figures, albeit using a 24% corporation tax rate and this time including a cash receipt by the Appellant in the second year equal to 125% of the anticipated studio benefit and then further cash returns in each of years 3, 4 and 5 equal to 125% of the cash receipts in prior years; and

(6) that presentation also contained projections for how an assumed waterfall for the Appellant based on certain assumptions might operate, based on two recent films, Moulin Rouge and Chicago, as benchmarks although there was a disclaimer to the effect that the outcome shown in those projections were no more likely than any other outcome and did not represent the FF group’s opinion of the likely outcome.

Pre-transaction - the Investment Committee and the IC Submission

27. The relevant points arising out of the IC Submission and the minutes of the meeting of the Investment Committee are as follows:

(1) the meeting took place on 24 October 2012, which was just three days before the execution of the first transaction document - namely the Copex Loan Agreement;

(2) the term of the transaction in the IC Submission was described as perpetuity but with an initial cycle of five years. The submission set out four possible scenarios for the film - described as “Downside”, “Base Case”, Management Case” and “Upside Case” respectively and based on box office returns on budget of 79%, 270%, 358% and 682% respectively. The first two cases showed negative returns to the Appellant of 100% and 47% respectively whereas the latter two cases showed positive returns to the Appellant of 18% and 33% respectively. Each case assumed contingency payments of 20%;

(3) in the section headed “Counsel” in the IC Submission, reference was made to the film’s producing an IRR in the Base Case of 31.6% “on the Day 1 Services” (which Mr Margolis explained meant the amount of the Studio Benefit). (Based on a later appendix in the submission, it appears that the reference to the “Base Case” in this section should have been to the “Management Case”;)

(4) the terms of the waterfall described in the IC Submission differed slightly from the terms of the Waterfall as eventually agreed. (The terms of the Waterfall as eventually agreed are set out in paragraph 30(9) below but the two differences were that:

(a) at stage 8 of the Gross Receipts part of the draft waterfall, the Appellant was going to be entitled to receive 18.37% of “Gross Receipts” (as defined) whereas, in the Waterfall as eventually agreed, that figure was 6.02%; and

(b) in the Net Receipts part of the draft waterfall, the Appellant was going to be entitled to receive 1% of the “Net Receipts” (as defined) whereas, in the Waterfall as eventually agreed, that figure was 0.32%;) and

(5) the minutes of the Investment Committee’s meeting noted that, with the exception of a slight increase in the production budget since the last transaction by an FF group entity in relation to Les Miserables had been implemented, “there [had] been no change in the status of the Film”. The minutes went on to conclude that, on the basis of the box office returns obtained by Moulin Rouge and Chicago, the Appellant “has the potential to recoup net profits in the region of $2.2m (based on the model and assumptions) if it achieves the upside case, but even if does not perform this well the [Appellant] should still realise returns”.

The transaction documents

28. We now summarise those terms of the documents which gave effect to the transaction which we consider to be material to our decision.

29. The most significant of the transaction documents so far as this decision is concerned are the P&A SAs.

30. The Head P&A SA provided that, inter alia:

(1) Corpus engaged the Appellant to provide those services which might be mutually agreed by the parties from time to time from the list of services set out in exhibit A to the agreement and/or such other P&A services as might be requested by Corpus from time to time in accordance with the “Approved Marketing Plan”. It went on to say that, at the date of the agreement, the services would in any event include those services which were marked with an asterisk in exhibit A (clause 2.1).

The definition of the “Approved Marketing Plan” was set out in clause 4.3. That clause stipulated that:

(a) Corpus, on the request of the Appellant, would submit a marketing plan substantially in the form of exhibit B to the agreement to the Appellant prior to the release of the film in the US and that that would be the “Approved Marketing Plan”;

(b) the Appellant would perform the services in accordance with the plan;

(c) any changes to the plan requested by the Appellant would be subject to the prior approval of Corpus; and

(d) if Corpus were to notify the Appellant of changes to the plan, the Appellant would render the services in accordance with the revised plan as long as that did not lead to an increase in the services budget.

Exhibit A contained a long list describing more than fifty categories of possible services and included an asterisk marked against two of those categories - namely, creative advertising and publicity.

Exhibit B set out the media services and non-media services which were to be included in the Approved Marketing Plan;

(2) exhibit B also set out a list of “Material Elements”, of which one was the Approved Marketing Plan. The elements included a number of items which were said to be “to be determined”. The agreement provided that Corpus would have sole discretion and approval of the Material Elements and, to the extent that they formed part of the services supplied by the Appellant, required the Appellant to implement any changes to the Material Elements as requested by Corpus (clause 2.4);

(3) Corpus was required to be informed of the progress of the services. The Appellant had the right to sub-contract the services to any person approved by Corpus and the agreement provided that both Journal and Marital were approved sub-contractors for this purpose (clause 2.5);

(4) the services budget was £3,005,543 and it would be allocated in accordance with schedule 1 (clause 3.1). Schedule 1 contained the same list of possible services as were set out in exhibit A and allocated part of the total services budget to each of creative advertising and publicity - the two items marked with an asterisk in exhibit A;

(5) the Appellant was required to provide all funds necessary for the performance of the services up to the amount of the services budget and, to the extent that the services budget was exhausted, Corpus would be entitled to, or to authorise Marital to, perform further and additional services in respect of the film. Corpus was also entitled to, or to authorise Marital to, perform, complete and pay for any P&A services which were not to be performed under the agreement but the Appellant would not have any obligation to Corpus in connection with that (clause 3.2);

(6) Corpus would have reasonable access to the books and records in respect of the services (clause 3.3);

(7) the services would be performed until the earlier of confirmation from Corpus that they had been completed or 31 March 2014 (or such other date as might be nominated by Corpus) (clause 4.1);

(8) Corpus would, on the written request of the Appellant, make available to the Appellant or its designee, such advertising and promotional materials relating to the film as Corpus had in its possession and that, for this purpose, Marital was the Appellant’s designee (clause 4.5);

(9) Corpus would pay the Appellant £15, together with the services fee set out in schedule 2 (clause 6.1). Schedule 2 set out the terms of the Waterfall.

In broad terms, the Waterfall was divided into two sections - an allocation of “Gross Receipts” and an allocation of “Net Receipts”, in each case, only during the “Term”. For this purpose, the “Term” was defined as the period commencing on the first release of the film and ending on 31 October 2017, which meant that it was five years from inception of the structure.

The terms of the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall stipulated that, prior to any payment to the Appellant in respect of Gross Receipts (at stage 4), there were to be allocated to Corpus:

(a) a distribution fee equal to 30% of the Gross Receipts;

(b) an amount equal to the “Distribution Expenses” (as defined) incurred by Corpus minus an amount equal to the Studio Benefit received by Marital at inception; and

(c) all payments due to third parties in respect of the film including contingent compensation, deferments and participations.

The stage 4 payment which would then become due to the Appellant out of Gross Receipts was a capped amount of £9,703. That was followed by allocations to Corpus, at stages 5 and 6, of amounts equal to the film’s production costs.

The first meaningful payment to the Appellant under the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall arose at stage 7. At that stage, the Appellant would become entitled to 85% of the Gross Receipts, subject to a cap equal to 125% of the Studio Benefit plus 25% of £9,703 (the capped amount payable to the Appellant at stage 4). At stage 8, the Appellant would become entitled to 6.02% of the Gross Receipts, subject to a cap equal to all amounts due under the Journal Loan Agreement including the principal amount of £2,781,486 and interest thereon.

No further payment in respect of Gross Receipts would be made to the Appellant after stage 8.

The terms of the Net Receipts element of the waterfall entitled the Appellant to 0.32% of the “Net Receipts” (as defined).

Paragraph 5 of schedule 2 required Corpus to prepare regular reports on how the Waterfall was operating so far as the Appellant was concerned and paragraph 6 of schedule 2 entitled the Appellant, no more than once annually, to audit the financial records of the studio in order to verify that the Waterfall was being applied correctly;

(10) Corpus would be entitled to retain from any monies otherwise payable to the Appellant under clause 6.1 all losses suffered by Corpus as a result of a default by the Appellant or any permitted sub-contractor (other than Marital) which did not derive directly or indirectly from a default by Corpus or Marital (clause 6.2);

(11) notwithstanding anything to the contrary in the agreement, a breach or default under any of the transaction documents by the Appellant, Journal, any member of the Appellant or any permitted sub-contractor other than Marital would not give rise to a termination right to Corpus or enable Corpus to make a claim against the Appellant to the extent that it was caused by Corpus or Marital (clause 11.2);

(12) all obligations of Corpus under the agreement would automatically terminate upon the termination of the Studio P&A SA or the engagement of Marital under that agreement (clause 11.3);

(13) on termination, each party would be released from all obligations to the other provided that, inter alia, as long as Marital had received the Studio Benefit, the Appellant would be entitled to retain its rights under stages 4 and 7 of the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall (clause 11.4);

(14) each party would indemnify the other and its affiliates and members for losses caused by reason of a breach of the agreement by that party provided that:

(a) the Appellant would have no obligation to indemnify Corpus and its affiliates or members for any breach by the Appellant caused by Corpus or Marital;

(b) Corpus would have no obligation to indemnify the Appellant or its affiliates or members for any breach by Corpus caused by a permitted sub-contractor other than Marital (clause 12.1(a)); and

(c) Corpus would have no obligation to indemnify the Appellant or its affiliates or members for any tax liability;

(15) the Appellant was precluded from assigning its rights under the agreement other than by way of security to Corpus and Marital but the Appellant was permitted to sub-contract its obligations under the agreement to a permitted sub-contractor (which included Journal and Marital) and Corpus was entitled to assign its rights under the agreement to an affiliate or another member of the Universal group or to its lenders by way of security (clause 13); and

(16) the liability of the Appellant under the agreement would be capped at the amount which it had received by way of the fee for its services (clause 17.5).

31. The Sub P&A SA provided that, inter alia:

(1) the Appellant irrevocably engaged Journal to provide those services which might be required by the Appellant from time to time from the list of services set out in exhibit A to the agreement and/or such other P&A services as might be requested by the Appellant from time to time in order to enable the Appellant to comply with its obligations to Corpus under the Head P&A SA. It went on to say that, at the date of the agreement, the services would in any event include those services which were marked with an asterisk in exhibit A and that the services would in any event not exceed the services budget. In addition, Journal would be responsible for arranging for the services and would co-ordinate with the Appellant and Marital to enable the Appellant to fulfil its obligations to Corpus under the Head P&A SA. The Appellant was precluded from appointing any other contractor to perform the services without the prior approval of Journal (clause 2.1). Exhibit A was in the same form as exhibit A to the Head P&A SA;

(2) Corpus was to have sole control of the “Material Elements” and any change to the technical, financial and business elements and decisions in relation to the services were subject to the Appellant’s confirmation that Corpus was satisfied with them (clause 2.2). The Material Elements, including the Approved Marketing Plan, were then set out in exhibit B, which was the same as exhibit B to the Head P&A SA;

(3) Journal was required to keep the Appellant and Corpus informed of the progress of the services. Journal was permitted to sub-contract the services to any person approved by the Appellant and Marital was an approved sub-contractor for this purpose (clause 2.3);

(4) the services budget was £2,975,543 and it would be allocated in accordance with schedule 1 (clause 3.1). Schedule 1 contained the same list of possible services as were set out in exhibit A and allocated part of the total services budget of £2,975,543 to each of creative advertising and publicity - the two items marked with an asterisk in exhibit A;

(5) to the extent that the services budget was exhausted, Corpus would be entitled to, or to authorise Marital to, perform further and additional services in respect of the film. In addition, Corpus was entitled to, or to authorise Marital to, perform, complete and pay for any P&A services which were not to be performed under the agreement but neither Journal nor the Appellant would have any obligation to the other in connection with that (clause 3.2);

(6) the Appellant would have reasonable access to the books and records in respect of the services (clause 3.3);

(7) the services would be performed until the earlier of the confirmation from the Appellant that they had been completed or 31 March 2014 (or such other date as might be nominated by the Appellant) (clause 3.3);

(8) the Appellant would submit a marketing plan substantially in the form of exhibit B to the agreement to Journal prior to the release of the film in the US and that would be the “Approved Marketing Plan”. Then:

(a) Journal would perform the services in accordance with the plan;

(b) any changes to the plan requested by Journal would be subject to the prior approval of the Appellant; and

(c) if the Appellant were to notify Journal of any changes to the plan requested by Corpus, Journal would render the services in accordance with the revised plan as long as that did not lead to an increase in the services budget.

(clause 4.3). As noted in paragraph 31(2) above, exhibit B was in the same form as exhibit B to the Head P&A SA;

(9) the Appellant was required to provide to Journal or its designee, such advertising and promotional materials relating to the film as the Appellant had in its possession and that, for this purpose, Marital was Journal’s designee (clause 4.5);

(10) the Appellant would pay Journal the services fee set out in schedule 1 and, to the extent that the services were able to be provided at a lesser cost than the services budget, Journal would be entitled to retain any underage. Schedule 1 set out the services fee of £3,005,543 and included line items for the Marital margin of £28,850.18 and the Journal margin of £30,000;

(11) all obligations of the Appellant would automatically terminate upon the termination of the Studio P&A SA or the engagement of Marital under that agreement (clause 11.3); and

(12) Journal was precluded from assigning its rights under the agreement other than by way of security to Marital, the Appellant or Illuminatrix but Journal was permitted to sub-contract its obligations under the agreement to a permitted sub-contractor (which included Marital) and the Appellant was precluded from assigning its rights under the agreement other than by way of security to Corpus (clause 13).

32. The Studio P&A SA provided that, inter alia:

(1) Journal irrevocably engaged Marital to provide those services which might be required by Journal from time to time from the list of services set out in exhibit A to the agreement and/or such other P&A services as might be requested by Journal from time to time in order to enable Journal to comply with its obligations to the Appellant under the Sub P&A SA. It went on to say that, at the date of the agreement, the services would in any event include those services which were marked with an asterisk in exhibit A and that the services would in any event not exceed the services budget. In addition, Marital would be responsible for arranging for the services and would co-ordinate with Journal and the permitted sub-contractors to enable Journal to fulfil its obligations to the Appellant under the Sub P&A SA. Journal was precluded from appointing any other contractor to perform the services without the prior approval of Marital (clause 2.1). Exhibit A was in the same form as exhibit A to the two other P&A SAs;

(2) Corpus was to have sole control of the “Material Elements” and any change to the technical, financial and business elements and decisions in relation to the services were subject to Journal’s confirmation that Corpus was satisfied with them (clause 2.2). The Material Elements, including the Approved Marketing Plan, were then set out in exhibit B, which was the same as exhibit B to the other two P&A SAs;

(3) Marital was required to keep Journal informed of the progress of the services and Marital was permitted to sub-contract the services to any person approved by Journal provided that:

(a) that right of approval did not extend to any end-supplier or end-services provider;

(b) Universal Pictures, a division of Universal City Studios, LLC, was an approved sub-contractor for this purpose; and

(c) no permitted sub-contractor would be entitled to sub-contract onward without the prior approval by Corpus of the relevant onward sub-contractor

(clause 2.3);

(4) the services budget was £2,975,543 and it would be allocated in accordance with schedule 1 (clause 3.1). Schedule 1 contained the same list of possible services as were set out in exhibit A and allocated part of the total services budget of £2,975,543 to each of creative advertising and publicity - the two items marked with an asterisk in exhibit A;

(5) Journal would pay Marital the services fee set out in schedule 1 (which was an amount equal to the services budget and included a line item for the Marital margin of £28,850.18) and specified that:

(a) the services fee was to be discharged by the cash payment by Journal to Marital of the Studio Benefit and the assignment to Marital of Journal’s rights under the Journal Loan Agreement;

(b) to the extent that the services budget was exhausted, Corpus would be entitled to, or to authorise Marital to, perform further and additional services in respect of the film; and

(c) Corpus was entitled to, or to authorise Marital to, perform, complete and pay for any P&A services which were not to be performed under the agreement but that neither Marital nor Journal would have any obligation to the other in connection with that

(clause 3.2);

(6) Journal would have reasonable access to the books and records in respect of the services (clause 3.3);

(7) the services would be performed until the earlier of the confirmation from Journal that they had been completed or 31 March 2014 (or such other date as might be nominated by Journal) (clause 4.1);

(8) Journal would submit a marketing plan substantially in the form of exhibit B to the agreement to Journal prior to the release of the film in the US and that would be the “Approved Marketing Plan”. Then:

(a) Marital would perform the services in accordance with the plan;

(b) any changes to the plan requested by Marital would be subject to the prior approval of Journal; and

(c) if Journal were to notify Marital of any changes to the plan requested by Corpus, Marital would render the services in accordance with the revised plan as long as that did not lead to an increase in the services budget

(clause 4.3). As noted in paragraph 32(2) above, exhibit B was in the same form as exhibit B to the other P&A SAs;

(9) to the extent that the services were able to be provided at a lesser cost than the services budget, Marital would be entitled to retain any underage (clause 6.1);

(10) the agreement would terminate automatically in the event of Marital’s insolvency (clause 11.1);

(11) if Marital failed to perform its obligations under the agreement, then Journal could terminate the agreement (clause 11.2);

(12) the agreement would terminate automatically upon any termination of the Head P&A SA (clause 11.3); and

(13) Marital could terminate the agreement if Journal failed to pay the Studio Benefit to Marital by 31 October 2012 (clause 11.4).

33. The DB contained a number of other relevant transaction documents in addition to the P&A SAs. These included:

(1) the Copex Loan Agreement;

(2) the Journal Loan Agreement;

(3) the Partnership Deed;

(4) the Consultancy Agreement; and

(5) various security documents.

34. The Copex Loan Agreement included conditions precedent to the drawdown (in schedule 2 to the agreement), one of which was that each of Journal, Illuminatrix and the Appellant was required to have signed a letter of instruction to Copex to the effect that the £2,781,486 which it was about to receive into its account with Copex as part of the circular flow of monies on the drawdown date had to be paid on to the account at Copex of the next entity involved in that flow.

35. The Journal Loan Agreement provided that, inter alia:

(1) the loan made under the agreement could be used only to make Illuminatrix’s capital contribution to the Appellant (clause 2.3);

(2) the execution of the Partnership Deed, the P&A SAs and the transaction security documents were conditions precedent to drawdown (clause 3.1);

(3) Illuminatrix was required to pay interest on the loan on 31 October 2013 and thereafter on each 31 October until the repayment date but, if, on any interest payment date, Illuminatrix had received insufficient distributions from the Appellant to pay the interest which was then due, the relevant interest would be payable on the repayment date (clause 3.4.4);

(4) Illuminatrix was required to pay all distributions which it received from the Appellant to Journal immediately upon receipt of the distributions (clause 4.2); and

(5) Journal was permitted freely to assign its rights under the agreement (clause 12.4).

36. The Partnership Deed provided that, inter alia:

(1) the purpose of the Appellant was to carry on the trade of providing services in respect of one or more projects involving films (clause 2.2);

(2) the profits and losses were to be allocated to members in the same proportions as those to which we have referred in paragraph 26(3) above (clause 8);

(3) all income and capital proceeds of the Appellant would be used by the Appellant to meet expenses and then retained by the Appellant until the Appellant was wound up (clause 9); and

(4) in each period of account of the Appellant ending on or after 31 October 2017, the Designated Members would review the then current trading position of the Appellant and consider whether or not to propose a resolution to the members to wind up the Appellant (clause 14).

37. The Consultancy Agreement provided that, inter alia:

(1) the Appellant engaged FFC to provide the Appellant with consultancy services and such other services as might be agreed between the parties (clause 2.1);

(2) the Appellant would pay consultancy fees to FFC in an amount equal to 8% of the aggregate capital contributions received by the Appellant in its first period of account (including the capital contribution of Illuminatrix) and an annual fee thereafter (clause 4); and

(3) the consultancy services would be as set out in schedule 1. That schedule set out the range of consultancy services to be provided, including identifying and evaluating suitable projects, carrying out the work needed for the Appellant to be able to enter into a project and perform its services in connection with it, monitoring and managing the provision of services by the Appellant, arranging for the exploitation of the library of film rights or rights in projects and executing, delivering and performing all contracts, and engaging in all activities, necessary to achieve the other services.

38. The security documents included various agreements to secure the obligations of the various FF group entities to Corpus and Marital.

39. The most significant of these was the agreement executed on 28 October 2012, pursuant to which each of the Appellant, Illuminatrix, Journal, Corpus and Marital executed payment directions to the effect that, prior to the repayment of the loan made under the Journal Loan Agreement, a designated share of the Appellant’s return under the Waterfall (corresponding to Illuminatrix’s share (86%) of the stage 8 payments under the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall) would be paid by Corpus directly to Marital, in satisfaction of Corpus’s obligation to the Appellant under the Waterfall, the Appellant’s obligation to make a distribution to Illuminatrix and Illuminatrix’s obligation to Marital to repay the loan made under the Journal Loan Agreement.

40. There were a number of other security documents under which, inter alia:

(1) the Appellant charged its rights under the transaction documents to Corpus to secure its obligations to Corpus under the Head P&A SA and the obligations to Corpus of each party to the transaction documents apart from Corpus and Marital;

(2) Journal charged its rights under the transaction documents to Marital to secure its obligations to Marital under the Studio P&A SA and the obligations to Marital of each party to the transaction documents apart from Corpus and Marital;

(3) subject to the prior charge in favour of Corpus, the Appellant charged its rights under the transaction documents to Journal to secure its obligations to Journal under the Sub P&A SA;

(4) Illuminatrix charged its membership interest in the Appellant to Marital to secure its obligations to Marital under the Journal Loan Agreement, Journal’s obligations to Marital under the Studio P&A SA and the obligations to Marital of each party to the transaction documents apart from Corpus and Marital; and

(5) subject to the prior charge in favour of Marital, Illuminatrix charged its membership interest in the Appellant to Journal to secure its obligations to Marital under the Journal Loan Agreement.

41. The overall effect of the security package was broadly to ensure that the Universal group was not exposed to the insolvency of any of FF group entities and, in particular, that Corpus could pay Illuminatrix’s share of the stage 8 payments under the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall (if any) directly to Marital even if one or more of the Appellant and Illuminatrix were to be insolvent.

Post-transaction documents

42. In addition to the pre-transaction and transaction documents, the DB contained various post-transaction documents pertaining to the transaction.

43. For instance, it contained:

(1) several updates sent by Mr Lipman to the corporate members in the Appellant during 2013 and 2014, which described the box office returns from the film very positively. The report for July 2013 noted that the film had achieved a 518% return on budget, placing it significantly above the Base Case and the Management Case considered by the Investment Committee and only just below the Upside Case considered by the Investment Committee. It said that receipts were not yet high enough to generate a return under the Waterfall but noted that the figures did not take into account home video sales and other media receipts and that things were still at an early stage. The report for October 2014 was similarly optimistic, noting that the box office returns were still at the same level and that the small payment under Stage 4 of the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall had been received. It went on to say that FFC anticipated that stage 7 of the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall would shortly be reached and that the film needed to generate only $8m more in gross receipts before that became due; and

(2) several reports from Corpus to the Appellant setting out how the Waterfall was operating in the light of revenues and expenses to the relevant date. These showed that the expenses and contingent payments arising in connection with the film were considerably greater than had been anticipated by the Investment Committee at the time of its meeting.

44. The DB also contained the accounts of Illuminatrix for its accounting reference period ending 13 September 2013. In the accounts:

(1) Mr Margolis was recorded as the sole director of the company during the relevant period;

(2) the company’s investment in the Appellant had been written down to nil; and

(3) the notes to the accounts stated that this was because the directors considered the value of the investment to be nil.

The witness evidence

45. There were two accounting expert witnesses, whose testimony we will set out and discuss in the section of this decision dealing with the GAAP Issue. In this section of the decision, we will confine ourselves to the evidence of Mr Margolis, who was the sole witness of fact at the hearing.

46. The relevant parts of Mr Margolis’s testimony were as follows:

(1) he was the director and sole owner of the companies in the FF group and had been involved in the film business for almost 30 years. He had not had primary responsibility for the present transaction. That had rested in the hands of four colleagues - Mr Thomas Gardner, Ms Patricia Jackson, Ms Katrina Stagner and Mr Kwesi Dickson. Mr Gardner’s and Ms Jackson’s background was in film finance, Ms Stagner’s background was in media law and Mr Dickson’s background was in film production. Mr Dickson’s prior experience meant that he had an understanding about the distribution of films;

(2) from his experience in the industry, Mr Margolis knew that studios were much more interested in the distribution of films than in the production of films. In relation to distribution, the studios liked risk-sharing deals in which, in exchange for initial finance, they would give away some of the potential box office upside through a waterfall. In this regard, studio films were a better bet for a group like the FF group than independent films. This was because the risk to the FF group was lower. However, he recognised that the group’s negotiating position with the studios was weaker and therefore that the group’s share of returns would not be as high. He was also aware of what he called “studio accounting” - the fact that it was the studio that was in control of reporting on the revenue and expenses in relation to a film for the purposes of operating the waterfall in connection with that film;

(3) he added that the studio would have had “a huge department dealing with the distribution of the movie” (Transcript Day 3 page 78 lines 18 and 19) and that it was likely that Marital would have sub-contracted its obligations under the Studio P&A SA either to that department or to specialist third parties outside, but overseen by, the studio;

(4) the Appellant was the thirteenth in a line of similar partnerships (referred to as “Spotlight” partnerships), two of which had already participated in similar transactions with the studio in relation to Les Miserables. Each of the transactions was effected using template documents developed by the FF group with the assistance of the law firm DLA Piper UK LLP. As he saw it, the transaction involved the provision by the Appellant of P&A services to the Universal group in relation to Les Miserables in return for potential returns through the Waterfall. If the film was successful and generated profits for the Appellant, then it could use those profits to invest in future deals;

(5) Les Miserables had been chosen as the appropriate film as a result of his discussions with Mr Marc Palotay of the studio, with whom he had a long-standing relationship. Les Miserables was a classic story and the film had a stellar cast and director. It could therefore be expected to have a long “tail” - by which Mr Margolis meant that it would continue to generate receipts long into the future and not solely from the immediate box office revenue, just as had been the case with other successful films such as The Shawshank Redemption and Gone with the Wind;

(6) however, the precise terms of the deal done by the Appellant were negotiated by Mr Gardner and Ms Jackson. In this regard, the decision to enter into the deal and the terms of the Waterfall were the result of a decision of the Investment Committee - of which he was not a member - following the presentation to the Investment Committee of the IC Submission;

(7) once the transaction had been implemented, the Appellant received regular updates from the studio on the receipts and costs associated with the film. A Mr Reece Lipman had been seconded by the FF group to the Appellant to manage the relationship with the studio and it was Mr Lipman who was responsible for overseeing the fulfilment of the P&A services by the Appellant under the Head P&A SA through the sub-contracting arrangements. Mr Lipman was also responsible for receiving the reports on the progress of the Waterfall from Corpus and reporting on the progress of the Waterfall to the corporate members;

(8) as it happened, in this case, the film had not given rise to meaningful returns for the Appellant through the Waterfall. However, this was due not to any shortfall in the box office receipts from the film as compared to those which the Investment Committee had predicted but rather to a large overspend on expenses and participations, which were much greater than the Investment Committee had predicted. Control over how much was spent on marketing and advertising the film was solely in the hands of the studio and the studio could be expected to act in its own interests. There was absolutely no doubt that the studio was “entitled to do what it [wanted] in relation to the distribution and promotion of its picture” (Transcript Day 3 page 87 lines 2 to 5). Moreover, the mere fact that a film was successful did not mean that the spending would be reduced because the push for awards would be likely to involve more marketing expenditure. One therefore had to trust the studio and hope that the eventual returns would justify any increase in spending;

(9) he was unable to explain why, at the same time that Mr Lipman was telling the corporate members that the box office returns from the film were such that payments under the Waterfall could be expected imminently, he had decided to write down Illuminatrix’s investment in the Appellant to nil. However, he did say that, following those reports, when the corporate members had not received any distributions from the Appellant, he had received complaints from certain corporate members about that;

(10) he accepted that, at inception, and during the tax years which were the subject of the appeal, the transaction had had a five-year term as set out in the P&A SAs. However, he said that, subsequently, in 2015, he had reached an oral agreement with Mr Palotay to the effect that the studio would continue to make payments under the Waterfall in perpetuity. That agreement had been reached shortly before Mr Palotay had died. The agreement arose as a result of a dispute between the parties caused by the insolvent liquidation of Journal for reasons unconnected with the transaction. Under the terms of the transaction documents, and the documents for similar transactions between other “Spotlight” entities and the studio, that triggered a right for the studio to terminate the deals and so Mr Margolis had sought to renegotiate them. It was in the course of that renegotiation that Mr Palotay had agreed that the Waterfall could be extended in perpetuity. Mr Margolis accepted that this agreement was not recorded in writing despite the fact that the DB contained emails between the two groups following Mr Palotay’s death recording the terms of the arrangement which they had reached as a result of the dispute over Journal’s insolvency. However, he said that he had continued to get reports from the studio until as recently as 2019 and that this was an indication that the studio had agreed to the extension;

(11) he added that the present proceedings had caused him to look during the course of giving his evidence at the reports provided to the Appellant by the studio over the term of the transaction and to compare some of the information in those reports with information in the public domain in relation to other films. Having done so, he had realised that the studio must have been over-stating its expenditure and under-stating its income in those reports and that, as he put it himself, “I just don’t believe their report and I should be having a conversation with Universal as a result of this…I think almost certainly I’ll be giving Universal a call after we’ve been through these proceedings” (Transcript Day 3 page 16 lines 2 and 3 and page 21 lines 21 and 22);

(12) he confirmed that both the gearing and the accounting write-down in the first period of account of the Appellant were essential to the transaction and that accounting advice in relation to the write-down had been obtained from Mazars but said that he would have hoped that, when negotiating the Waterfall and agreeing terms with the studio, the relevant personnel acting for the Appellant would have been focused more on maximising the profitability of the Appellant than in ensuring that the terms of the Waterfall justified the write-down;

(13) as regards the deliberations of the Investment Committee, he said as follows:

(a) he explained that the reason for the two changes to the terms of what became the Waterfall as between the time of the meeting of the Investment Committee and the execution of the transaction documents was that less money was raised from corporate members than had been anticipated. Thus, the studio was able to negotiate more favourable terms for itself than was initially expected;

(b) he accepted that the terms of the Waterfall were based on the economic reality that the Appellant was providing only the Studio Benefit (and not £3,005,543) to the studio and said that the terms of the Waterfall would have been more favourable to the Appellant if it had been based on a benefit to the studio of £3,005,543;

(c) he was unable to explain why the contingency payments estimated in the submission to the Investment Committee and in the minutes of the Investment Committee had been 20% instead of the 30% figure assumed for the same film in the two earlier transactions entered into by “Spotlight” entities in relation to Les Miserables. At one stage, he said that he could only imagine that, between the date of those earlier transactions and the transaction into which the Appellant had entered, more information had emerged which had suggested that that reduction was appropriate and, at another, he hypothesized that the Investment Committee might have relied on an industry average in reaching the lower figure;

(d) he explained that the Investment Committee would not have been able to obtain a meaningful estimate of the marketing and distribution costs from the studio because the studio would have been wary of being seen to have made binding representations in relation to those costs; and

(e) he said that the reference in the minutes of the Investment Committee to the film’s still generating “returns” if it failed to achieve the “Upside Case” simply meant that the film would in that case give rise to cash receipts and not necessarily profit. Those cash amounts could then be used for further transactions, as shown in the presentation to prospective members referred to in paragraph 26 above;

(14) as for the fact that a payment under stage 7 of the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall would potentially involve a payment by Corpus of an amount equal to 125% of the Studio Benefit, Mr Margolis rejected Ms Wilson’s characterisation of the transaction as in that event failing to achieve its purpose for the studio. Ms Wilson had posited that, in that case, instead of being an outright permanent receipt, the Studio Benefit would have become an expensive borrowing for the studio. He said that, as he saw it, the Appellant was providing P&A services to Corpus on a risk-sharing basis and that, if stage 7 of the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall was reached, the film would have been spectacularly successful so that the studio would not have minded repaying the Studio Benefit at a premium of 25% in that event;

(15) he accepted that he had not seen the Approved Marketing Plan or the letter referred to in paragraph 30(1)(a) above which Corpus was required to send to the Appellant in relation to the creation of the Approved Marketing Plan and that, despite frequent requests by the Respondents for those documents, they had not been provided to the Respondents. He put the absence of those documents down to the fact that:

(a) Mr Lipman was overseeing the services and in regular touch with the studio orally; and

(b) there had been a computer upgrade and an office move for the FF group since the period in question;

(16) similarly, he confirmed that:

(a) he had not seen any of the cost statements or reports mentioned in clause 3.3 of each P&A SA;

(b) he did not think that the Appellant had ever exercised the audit right set out in paragraph 6 of schedule 2 to the Head P&A SA;

(c) he did not know whether the costs which had been included in the reports provided by Corpus during the term of the transaction included a proportion of studio overheads;

(d) Marital was not obliged to use the Studio Benefit in providing the services under the Studio P&A SA; and

(e) the Appellant could not do better under the Head P&A SA by performing the services itself or by finding a sub-contractor other than Journal and Marital to perform the services;

(17) he said that the whole of the stage 4 payment under the Gross Receipts part of the Waterfall which had been received by the Appellant in its period of account ending 31 October 2014 had been used by the Appellant to meet its expenses. Those were:

(a) fees of £5,000 to Shipleys LLP for auditing the accounts of the Appellant and preparing the partnership tax returns; and

(b) fees of £4,528 in respect of the annual service charge due to FFC under the Consultancy Agreement.

(We were shown the invoices in relation to those fees in the DB.) As a result of those fees, none of the receipt in question had been paid to any of the members; and

(18) more generally, he said that the length of time which had passed since the transaction had been implemented had contributed to the absence of documentation.

findings of fact

Introduction

47. Before setting out our conclusions of fact, we should make some general observations about the evidence of Mr Margolis. Although Mr Margolis provided us with some helpful general information on the film industry and the manner in which it operates, we were not persuaded by much of his evidence in relation to the two issues which are key to this decision - namely:

(1) the purpose of the Appellant in entering into the transaction; and

(2) the nature of the transaction.

48. We reached this view for essentially four reasons.

49. The first was that, by his own admission, Mr Margolis was some way removed from the transaction in terms of the detail. Much of his evidence was therefore speculative in nature, based on his general experience of similar deals and not this specific transaction. Mr Margolis himself had not had any meaningful involvement in the transaction so that he could not speak with any authority about the assumptions underlying the recommendation by the Investment Committee that the Appellant should enter into the transaction on the terms which it did or the financial implications of the transaction for the Appellant.

50. In particular, Mr Margolis was unfamiliar with the basis for the assumptions underlying the Waterfall and did not know why the terms of the Waterfall changed in the five days between the Investment Committee’s recommendation and the execution of the Head P&A SA. As such, he was forced to guess, based on his general experience of deals such as the present one, what was going through the minds of the people who actually implemented the transaction. For example, when asked whether the desire to obtain the accounting loss in the first period of account of the Appellant had informed the negotiation on the terms of the Waterfall, he was able to say only that he “hoped” that it had not.

51. We really needed to hear evidence from the individuals who were actually involved in implementing the transaction on behalf of the Appellant - one or more of Messrs Gardner, Dickson and Lipman, Ms Jackson or Ms Stagner. In addition, given that each of the issues but, in particular, the Trade Issue, the View to Profit Issue and the GAAP Issue, turned on the economics of the Waterfall and the nature of the transaction, we would ideally have heard evidence from someone from the studio, who might have shed some light on how the studio viewed the transaction. Whilst that evidence would not have been of direct relevance to the question of the Appellant’s purpose in entering into the transaction, it would have shed considerable light on the true nature of the transaction and on the likelihood of the Appellant’s making a profit from the transaction.

52. Ms Wilson and Mr Macklam invited us to draw an adverse inference from the failure of any of those individuals to attend the hearing. Mr Ramsden objected to that, pointing out that no explanation of why the individuals were not giving evidence had been requested. We do not draw an adverse inference from the failure of the relevant individuals to attend and give evidence at the hearing. There are all sorts of perfectly reasonable explanations as to why they did not. However, in the context of proceedings in which the burden of proof is on the Appellant in relation to each of the issues, we would say that it is, to put it mildly, surprising that sole reliance has been placed on Mr Margolis. We cannot help but contrast the relative paucity of witness evidence in this case with the witness evidence in the similar case of Eclipse Film Partners (No 35) LLP v The Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs [2015] STC 1429 (“Eclipse”), where the taxpayer called four witnesses.

53. The lack of additional witness evidence ties in with the second reason for our reluctance to accept Mr Margolis’s evidence in relation to the purpose of the Appellant in entering into the transaction or the nature of the transaction and that is that his evidence was inconsistent with the written evidence before us. It was inconsistent in two respects - that which was there and that which was not there.

54. As regards that which was there, we were provided with the terms of the transaction documents and, in particular, the three P&A SAs. These showed very clearly that all responsibility for the distribution and marketing activities in relation to the film remained within the Universal group because of the manner in which the three documents interacted. The terms of the Waterfall in the Head P&A SA also served to cast doubt on Mr Margolis’s proposition that the Appellant entered into the transaction to make a profit. For reasons on which we expand below, we believe that there was no meaningful prospect that the Waterfall would give rise to a profit for the Appellant.

55. As regards that which was not there:

(1) Mr Margolis testified that Mr Lipman had played an ongoing role in liaising with the studio in relation to the provision of the services but there was not a single piece of written evidence in the DB to support that proposition. If that had been the case, we would have expected to see frequent exchanges of emails between Mr Lipman and his contact at the studio to that effect. In the absence of any such written evidence and any oral evidence from Mr Lipman himself, Mr Margolis’s testimony on that subject lacks credibility;

(2) Mr Margolis said in his evidence that he had agreed with Mr Palotay shortly before the latter’s death an extension to the term over which the Waterfall would continue to operate. Whilst it was of limited relevance to the issues which we were considering - because our decision necessarily relates to the position in the two tax years in question and we are required to identify the purpose of the Appellant in entering into the transaction and the nature of the transaction in those tax years - no written evidence of that agreement was provided to us. That was the case despite the fact that:

(a) the dispute between the parties which had led to the oral agreement was settled by way of exchanges of emails in writing, none of which mentioned the extension of the term; and

(b) there was no commercial reason for the studio to agree to such an extension.

As such, we did not think that Mr Margolis did enough to persuade us that, on the balance of probabilities, that extension occurred; and

(3) Mr Margolis said that he had received complaints from certain corporate members in relation to their failure to receive any distributions of profit from the Appellant. This point was of some significance in the context of whether or not the Appellant was trading with a view to profit and so we would have expected to see some written evidence to that effect but no such written evidence was provided. As such, we are not persuaded that any such complaints were made.