Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

First-tier Tribunal (Tax)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> First-tier Tribunal (Tax) >> Wilkinson v Revenue & Customs (SDLT - Multiple Dwellings Relief) [2021] UKFTT 74 (TC) (16 March 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2021/TC08059.html

Cite as: [2021] UKFTT 74 (TC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

[2021] UKFTT 74 (TC)

SDLT - Multiple Dwellings Relief - whether part of a large residential property was suitable to be used as a single dwelling - no - appeal dismissed.

|

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL TAX CHAMBER |

|

Appeal number: TC/2020/01097 |

BETWEEN

|

|

paul and jane wilkinson |

Appellants |

-and-

|

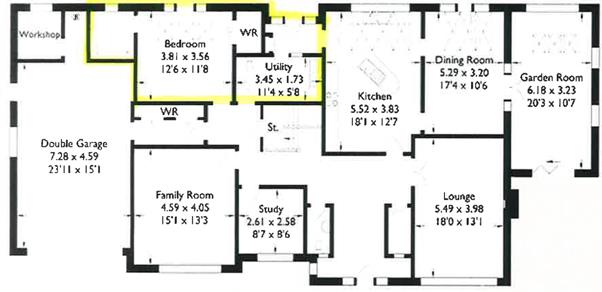

|

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HER MAJESTY’S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS |

Respondents |

|

TRIBUNAL: |

JUDGE tracey bowler

|

The hearing took place on 8 February 2021. With the consent of the parties, the form of the hearing was V (video) and the Tribunal video platform was used. A face to face hearing was not held because of the measures required by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Prior notice of the hearing had been published on the gov.uk website, with information about how representatives of the media or members of the public could apply to join the hearing remotely in order to observe the proceedings. As such, the hearing was held in public.

Mr Patrick Cannon, Counsel, instructed by the Wilton Group for the Appellant

Dr Jeremy Schryber, litigator of HM Revenue and Customs’ Solicitor’s Office, for the Respondents

DECISION

Introduction

1. The Appellants appeal under paragraph 35 of Schedule 10 Finance Act 2003 (“FA 2003”) against a closure notice issued by the Respondents, (“HMRC”) under paragraph 23 Schedule 10 FA 2003 refusing a requested repayment of £10,000 of stamp duty land tax (“SDLT”). The Appellants had claimed that multiple dwellings relief (“MDR”) applied to their purchase of a property. The issue in dispute is whether the Appellants purchased one or two dwellings and in particular whether one large house should properly be treated as two dwellings.

Background

2. On 6 November 2017, the Appellants purchased a property known as “Oatlands”, X Road, Lancaster (“the Property”) for £875,000. (There is no reason for the full address to be stated and I have therefore partially anonymised it.)

3. On 7 November 2017, the Appellants filed an SDLT return for the acquisition of the Property, self-assessing the SDLT due as £35,750 on the basis that the Property did not qualify for MDR.

4. On 9 November 2018, the Appellants’ representatives sent a letter to HMRC to amend the SDLT return by adding a claim for MDR. The stamp on it shows that it was received by HMRC on 23 November 2018. The letter stated that the purchase comprised the purchase of the main house together with a separate annex. The amount of SDLT self-assessed was reduced by £10,000 to £25,750.

5. On 13 August 2019, HMRC sent a notice of enquiry to both Appellants, informing them that HMRC would be enquiring into their SDLT return under paragraph 12 Sch 10 FA 2003. The Appellants have not sought to claim that the notice was sent out of time.

6. On 2 October 2019, the Appellants’ representatives replied to HMRC providing a floor plan and photographs of the Property.

7. On 29 October 2019, HMRC issued the Closure Notice, concluding that the acquisition of the Property did not qualify for MDR.

8. On 28 November 2019, the Appellants’ representatives appealed the Closure Notice and requested a review.

9. On 10 December 2019, HMRC sent their “view of the matter” letter to the Appellants informing them that HMRC’s decision had not changed.

10. On 7 January 2020, the Appellants’ representatives sent a letter to HMRC requesting a statutory review.

11. On 13 February 2020, HMRC sent a review conclusion letter to the Appellants informing them that the Closure Notice had been upheld.

12. On 13 March 2020, the Appellants appealed to the Tribunal.

grounds of appeal

13. The Appellants’ grounds of appeal submitted with their appeal can be summarised in essence as:

(1) the Appellants acquired two “dwellings” as defined by paragraph 7(2) schedule 6B, FA 2003 so that MDR was properly claimable;

(2) that was because the Property included a separate en-suite bedroom and utility area which affords the occupier of that area the facilities required for day-to-day domestic existence and which should therefore be treated as a “dwelling” in its own right.

14. Since lodging the grounds of appeal the Appellants have claimed that there is an alternative basis to conclude that the Property consisted of two “dwellings” as the ensuite bedroom could be treated as a “dwelling” in its own right without access to the utility room.

burden of proof

15. The burden is on the Appellants to show that they were entitled to MDR and consequently to the refund of the SDLT claimed.

16. The standard of proof is the ordinary civil standard, which is the balance of probabilities.

evidence

17. The evidence consists of: the bundle of documentary evidence running to 110 PDF pages as set out in the index; a separate 2 page PDF consisting of land registry plans; and the oral evidence of Mr Wilkinson.

18. Mr Wilkinson provided clear, straightforward and open evidence at the hearing. He clarified the layout of the Property and I find that he was entirely open about the extent to which, for example, doors could be locked. I therefore make the following findings of fact on the basis of both his oral evidence and the documentary evidence provided by the Appellants.

findings of fact

19. The Property was sold by its previous owners as one large six bedroom residential property.

20. A floor plan for the Property’s ground floor is shown in the Appendix to this decision. The area marked in yellow shows the relevant ensuite bedroom with attached shower room (together referred to as “the Bedroom”), utility room (“the Utility Room”) and a lobby between the Utility Room and the external door. Together they are referred to as the “Disputed Area”. The remainder of the ground floor of the Property together with the first floor is referred to as the “Main Property”.

21. The Bedroom has French windows which open onto a back patio area. At the time of the purchase of the Property the French windows were lockable.

22. The ensuite bathroom attached to the Bedroom includes a toilet, basin and shower. There is no separate fresh water supply in the Bedroom.

23. The Bedroom has a walk-in wardrobe marked as “WR” on the plan with at least one electrical plug socket in the wardrobe and a light fitting. However, the wardrobe has no plumbing or other utility connections within it.

24. The door from the Bedroom to the hall area in the Main Property did not have a lock at the time of the purchase.

25. The door from the Utility Room to the hall area in the Main Property was not lockable at the time of the purchase.

26. Beside the Utility Room and within the Disputed Area there is a small lobby. There is a door from that lobby to the outside patio area which is lockable and the door from the Utility Room to the lobby has a lock which can be turned, but no key. However, the door from the lobby in the Disputed Area into the kitchen in the Main Property is not lockable.

27. It is not possible to access the Utility Room directly from the Bedroom. To go from one to the other it is necessary either to go outside via the back patio or to use the hallway which is part of the Main Property. There was no delineation or fencing off of part of the back patio/garden behind the Disputed Area to limit its use to the occupants of the Disputed Area. Use of that area would be shared with the occupants of the Main Property.

28. The Utility Room has a large stainless steel kitchen sink with drainer, a work surface, a toilet and electrical sockets. It currently contains a washing machine, tumble dryer and microwave.

29. The controls for:

(1) the water pump for the Property;

(2) the central heating for the ground floor of the Property excluding the kitchen, dining room and sun lounge;

(3) the hot water for the Property including the hot water in the kitchen

are all found in the Utility Room.

30. The fuse board and circuit breakers for the Property are located in the workshop in the garage. There is one stopcock in the kitchen and an external stopcock in the road at the bottom of the drive which was put in place by the water company when installing a water meter.

31. The Property is set in large gardens in a corner plot between the main road onto which the front of the Main Property faces and a side-lane running roughly perpendicular to the main road. The main access for the Property is from the front/main road. However, there is also a side gate giving access from the side lane. There is a fence from the boundary of the Property at the side gate to the closest side wall of the Property. It would therefore be possible to access the Bedroom by entering through the side gate and walking through a part of the garden and part of the back patio, without being seen from the front of the property.

32. The patio and back garden area are not separated for use individually by the Main Property and the Disputed Area.

33. The vendors of the Property told the Appellants that their son had spent some time using the Bedroom with its independent access as his accommodation while attending university. The vendors’ daughter had also used the Bedroom as accommodation for exchange programme students. However, there is no evidence to show the extent to which either the vendors’ son or the exchange students lived independently from those in the rest of the Property. The evidence is therefore insufficient to show that the Disputed Area or the Bedroom was previously used as a separate dwelling.

The Law

34. By virtue of section 42 FA 2003 SDLT is charged on land transactions. Under section 43 FA 2003 an acquisition of a major interest in land is a land transaction and under Section 49 FA 2003 a land transaction is a chargeable transaction if it is not exempt.

35. Section 44 FA 2003 sets out the rules to determine the effective date of the chargeable transaction, which in this case, in accordance with Section 119 FA 2003, is the date of completion. SDLT arises at that point.

36. Section 58 FA 2003 is the enabling section for MDR set out in schedule 6B. The relief was inserted by section 83 of the Finance Act 2011.

37. MDR applies where the subject of the land transaction is an interest in at least two “dwellings”. Paragraph 7 of Schedule 6B sets out the meaning of “dwelling” and states in sub-paragraph (2) that:

“a building or part of a building counts as a dwelling if

(a) it is used or suitable for use as a single dwelling…”

38. Paragraph 7(4) provides that land that subsists, or is to subsist, for the benefit of a dwelling is taken to be part of the dwelling.

39. In this case it is not argued that the Disputed Area is used as a single dwelling. The issue is whether it is suitable for use as a single dwelling.

The Appellants’ case

40. Mr Cannon referred to his skeleton argument in which he submits that:

(1) “dwelling” must take its ordinary everyday meaning, so a self-contained unit that provides an occupier with the means for a private domestic existence by having its own means of lockable entry and exit and living, sleeping, food preparation and bathing facilities, or which is suitable for doing so, will, in principle, qualify as a “dwelling”;

(2) it is a matter of “suitability” for use as a dwelling rather than actual use at the effective date that is determinative;

(3) there is nothing in principle to prevent the constituent parts of a dwelling being a dwelling even if parts of it are physically separate from the other, provided that each part is private and accessible only by the occupants of the other part of the dwelling. He relies on the example of historic rows of cottages sharing outhouse toilets when considering the dwelling consisting of the Bedroom and Utility Room;

(4) alternatively, the Bedroom should be treated as a separate dwelling. The existence or otherwise of a kitchen should not determine whether the area is a separate dwelling. Appliances could be placed in the Bedroom to allow the occupier to prepare and consume food and to wash up. He refers to a book (which he clarified at the hearing was published in 1961) called “Cooking in a Bedsitter” as evidence that meals can be prepared using a single cooking ring in even the “daintiest” of lodgings. HMRC’s own published guidance only notes that there should be space and infrastructure in place, such as plumbing for a sink and power source for a cooker. An occupant of the Bedroom could install a kitchen sink and a food preparation area in the walk-in wardrobe. In addition, it is becoming increasingly common for people to rely upon delivery and/or ready-made meals heated in a microwave such that formal kitchen facilities are often redundant and not seen as necessary for a self-contained dwelling;

(5) in HMRC’s guidance SP1/04 entitled Stamp Duty Land Tax: Disadvantaged Area Relief it was stated that, in the context of that relief, whether a building qualified as being suitable for use as a dwelling would depend upon the precise facts and circumstances. The removal of a bathroom or kitchen facilities would not be viewed as rendering the building unsuitable for use as a dwelling;

(6) in the case of Uratemp Ventures Limited v Collins [2001] UKHL 43 the House of Lords addressed the meaning of “dwelling” in the context of section 1 of the Housing Act 1988 and Lord Irvine stated that:

“Dwelling” is not a term of art, but a familiar word in the English-language which in my judgement in this context connotes a place where one lives, regarding and treating it as home. Such a place does not cease to be a “dwelling” merely because one takes all or some of one’s meals out; or brings takeaway food in to the exclusion of home cooking; or at times prepare some food for consumption in heating devices falling short of a full cooking facility.”

(7) Similarly, in the same case Lord Millett made clear that it had never been a legislative requirement for cooking facilities to be available for premises to qualify as a dwelling. In the First-Tier Tribunal decision of Carson Contractors Ltd v HMRC (2015) UKFTT 530, when considering a VAT case, the Tribunal did not require there to be facilities for the preparation of food;

(8) further guidance is provided in the approach taken when applying Council Tax legislation and to the VAT provisions dealing with the zero rating of supplies in relation to a “building designed as a dwelling or number of dwellings”;

(9) case law has considered the extent to which a lockable separating door is required in the context of VAT and Council Tax. The presence of one indicates a dwelling, but its absence is not fatal to such a classification, particularly given the decisions in Ramdhun v Coll (LO) [2014] EWHC 946 (Admin) and Jorgensen (LO) v Gomperts [2006] EWHC (Admin) 1885;

(10) similarly, relying on Ramdhun, shared utility meters are not fatal to there being a self-contained unit;

(11) in the SDLT context, Judge Citron in the First Tier Tribunal case of Fiander v HMRC [2020] UKFTT 190 (TC) decided that the utility metres, Council Tax status, lack of separate postal address and restrictive covenant issues were found to have little weight in deciding whether the part of the property was a “dwelling”;

(12) the marketing of the Property as a single dwelling is irrelevant. HMRC’s own guidance notes that an estate agent’s main objective is to sell the property, not define the dwellings;

(13) the floor plan shows that the Disputed Area is a clearly distinct unit of accommodation, albeit physically joined to the main dwelling.

41. At the hearing Mr Cannon submitted that it was not clear that the word “single” added much to “dwelling” in the legislation. Either a property is a dwelling or it is not.

42. He submitted that in Fiander Judge Citron adopted an unnecessarily narrow interpretation of “suitability” as a dwelling and in fact a wider approach should be adopted, more in line with “capable” of being a dwelling. The Bedroom would be suitable for use as a dwelling with minor modifications, such as the provision of a sink, cooker, microwave and fridge in the current walk-in wardrobe. Alternatively, if a sink could not be placed there a person could take a plastic washing-up bowl from the bathroom to the cupboard area. Ultimately, however Uratemp shows that the lack of kitchen facilities is not determinative.

43. Suitability should not be determined simply by reference to the position at the effective date of the transaction, but should take into account the ability to make minor modifications. HMRC’s own guidance reflects this approach when it is said that the removal of white goods in the sale of a house does not stop it being suitable for residential use as fresh appliances may be added. Similarly, a bolt could be fitted to either side of interconnecting doors.

44. He also submitted that the Fiander approach to the use of “single” was incorrect as the statement therein that “Use as a “single” dwelling excludes, in our view, use as a dwelling joined to another dwelling” would appear to suggest that flats in a block of flats would not be single dwellings.

45. In response to a question raised by me as to whether the existence or lack of rights-of-way across the Property to access the Disputed Area was relevant, Mr Cannon submitted that there would be an ability to access through a lease or licence of the Disputed Area with the express grant of access rights, or the presumption of them to allow access.

46. In response to the identification of the heating and hot water controls in the Utility Room, Mr Cannon submitted that he knew of blocks of flats where there was a single supply of heating and hot water dealt with through a communal service charge. The controls in the Utility Room should not therefore be relevant.

47. In response to a point raised by Dr Schryber, Mr Cannon submitted that the fact that the Appellant relied on alternative arguments about which parts of the Disputed Area should be treated as a dwelling was not because the Appellant was being inconsistent, but simply that there were two equally valid approaches which could be taken.

48. In response to a submission by Dr Schryber Mr Cannon submitted that there was no evidence from a fire regulations expert to show that placing bolts in the doors between the Disputed Area and the rest of the house would contravene fire regulations.

49. The fact that an entrance, such as that using the side gate, was shared should not be determinative as many blocks of flats will have communal shared entrances. Similarly the shared fuse board should not be determinative.

50. It was not correct to take HMRC’s broad brush evaluative approach to conclude that if something looks like a dwelling, it should be a dwelling. Instead, a property’s features and facilities should be addressed to ask whether in reality it is suitable for separate occupation.

HMRC’s case

51. Dr Schryber referred to his skeleton argument in which he submits that:

(1) at the effective date of the transaction the Property was a single dwelling of which the Disputed Area formed part and not two dwellings;

(2) the following factors indicate there were not two dwellings at the effective date of the transaction: the Disputed Area was not in fact being used as a separate dwelling; the Bedroom and the Utility Room do not interconnect and must be accessed by going outside or through the main hallway of the Property; the Disputed Area has no real unity, coherence or identity separate from the rest of the Property; there is a lack of security and privacy between it and the rest of the Property; access to the Disputed Area via the side gate and the rear of the Property is not a practical design for two separate dwellings; and the Utility Room offers very limited food preparation, storage and consumption facilities and with the presence of a WC raises hygiene concerns;

(3) a realistic view of the floor plan shows one dwelling;

(4) account should be taken of the fact that the Property was marketed as one detached house, there was no separate Council Tax or postal address; and there were no separate utility supplies, control or metering;

(5) HMRC’s guidance (which was not in place at the time of the transaction) states that where a building is considered to contain more than one dwelling, evidence will be needed to show that each one is sufficiently independent to count as a separate dwelling in its own right. A wide range of factors should be considered and where adjoining dwellings have interconnecting doors it is relevant whether they can be locked or are readily capable of being made secure from both sides;

(6) the decision in Fiander is not binding, but is instructive and has subsequently been adopted in Merchant and Gater v HMRC [2020] UKFTT 299 (TC).

52. At the hearing Dr Schryber submitted that close examination of the evidence shows that HMRC acted timeously after the Appellant’s representatives submitted the amendment to the SDLT return claiming MDR. Although the amendment was dated 9 November 2018, the evidence of the date of postage shows 21 November 2018 which was consistent with the amendment bearing a stamp showing receipt on 23 November 2018.

53. He also submitted that it must be determined whether the Property consisted of one or two dwellings at the time of the transaction by which the Appellants bought the Property. In doing so, all relevant facts and circumstances should be considered. It was then necessary to step back and assess the evidence in the round taking a realistic view of the facts. Factors like a lack of kitchen are important, although not determinative in themselves. The Disputed Area should be considered with its characteristics at the effective date of the transaction and not after modifications such as the fitting of bolts in doors. In particular, in the context of adding bolts to doors and other suggested modifications the Appellants had not provided evidence to show that the modifications would comply with fire or other regulations.

54. When considering case law the statutory context and the purpose of the relevant legislation should be borne in mind. The Council Tax and VAT cases consider statutory tests which are not the same and where the context is different. The Uratemp case in particular was addressing the protection of potentially vulnerable occupiers.

55. Dr Schryber submitted that the approach set out by Judge Citron in paragraphs 51 and 52 of Fiander was correct. “Single” was a word inserted in the legislation for a reason. In a Council Tax case two households were considered to arise in one property where there is no physical barrier, whereas in the context of MDR the use of the word “single” would mean there was just one single dwelling. In paragraph 52 of Fiander the reference is to self-sufficiency rather than physical separation.

56. Dr Schryber confirmed that the Respondents do not argue that dwellings must be physically separated from each other.

57. Dr Schryber submitted that Mr Cannon’s reference to outhouse toilets should not be taken to mean that in the 21st century a property is suitable as a dwelling if it is necessary to go outside to access the kitchen.

58. Dr Schryber submitted that the fact that the Appellants relied on either the Bedroom or the Bedroom and Utility Room constituting the dwelling meant that the Appellants themselves are unable to properly delineate an area in the Property as a separate dwelling. He submitted that the facts in this case were some way from the obvious position where two flats in a block or two semi-detached houses would be two separate dwellings.

59. Dr Schryber submitted that at the effective date of the transaction there was no right of way or access delineated for the Disputed Area and that was because it formed part of one single dwelling with the Main Property. It was not equivalent to properties such as flats sharing a communal entrance. The lack of separate controls for hearing and hot water was significant.

60. While it was possible for a person to live on microwave meals and takeaways, and wash-up in the small bathroom sink on a temporary basis, those elements of the Disputed Area were not consistent with a single dwelling for an objective observer. The approach adopted in paragraph 61 of Fiander was advocated. It was not generally appropriate for a person to be expected to live on takeaways and delivered meals.

61. Overall, the Property was laid out as one dwelling and not two.

Discussion

Closure notice validity

62. No issue has been raised by the Appellants regarding the validity of the closure notice in the grounds of appeal or in Mr Cannon’s submissions. I have therefore proceeded on the basis that the closure notice is valid. For the avoidance of doubt any potential issue about the timeliness of HMRC’s action I find to have been answered by Dr Schryber’s submissions at the hearing, recorded above.

Did the purchase of the Property qualify for MDR?

The time at which qualification for MDR should be shown

63. SDLT is payable on land transactions. It is the transaction itself which triggers the charge. In a case such as this Section 119 FA 2003 provides that the effective date of the transaction (which triggers the reporting/notification requirements set out in the legislation) is the date of completion. The tests for MDR to be applied must therefore be satisfied at the date of completion.

Used or suitable for use as a single dwelling

64. In this case it is not argued that the Disputed Area or part thereof was used as a single dwelling at the date of completion.

65. It is therefore necessary for the Appellants to show that the Disputed Area or part thereof was suitable for use as a single dwelling at the time of completion. I conclude that the test must therefore be applied as at that date according to the attributes of the property at that time. “Suitable” should not be read as encompassing properties which have the capacity to be used as dwellings after modification.

66. Mr Cannon submitted that minor modifications should be taken into account in assessing suitability. He submitted that if a property was sold with its white goods removed it would still be suitable to use as a dwelling. In the same way a property without locks on its doors could have those added.

67. I do not agree with that proposition. There are notable differences between replacing white goods removed from an area and putting locks on doors. Firstly, replacing the white goods restores the property to a previous state. A person deciding whether to reside in the property would be able to take account of the existence of the white goods and know they could move into the property and put themselves in that position. Putting locks on previously unlockable doors does not replace the locks. The equivalent for the locks would be if the vendor had removed the locks themselves and the purchaser had to replace them.

68. Second, placing locks on the doors changes the nature and function of the doors. The lockable doors provide a means of privacy and security not afforded by the doors without locks. There may be regulations such as fire regulations which need to be satisfied in order to fit locks.

69. I have been referred to the decision in Fiander which is not binding on me. I respectfully agree that the test of “suitability for use” is an objective test, and I am of the view that the test should be applied with regard to all of the features and circumstances of a property including, potentially, its location. So, for example, what is required for a property to be suitable as a single dwelling in the midst of the Scottish Highlands where it may take an hour or more to reach amenities such as food shops is likely to be different to what would be needed for a property to be suitable for use as a single dwelling in the heart of a city such as London.

Relevance of the use of “single”

70. There was some discussion with the representatives at the hearing about whether the word “single” adds anything to “dwelling”. Mr Cannon submitted that it was difficult to see how it did. I consider that it does perform a function for the following reasons.

71. It is well accepted that in applying legislation it should be assumed that words have been included by the draftsman and enacted by Parliament for a purpose. The Oxford English dictionary defines “dwelling” as a “place of residence”. The use of the adjective “single” qualifies “dwelling”, informing the reader as to the type of dwelling being identified. I consider that the use of the word “single” shows that the dwelling must have some sense of unity. It should have coherence as one identifiable property. Therefore five individual flats in a block will be five “single dwellings”, even if they share a communal entrance and hallway.

72. In Fiander it was stated that:

“By requiring that the building or part be suitable for use as a “single” dwelling, the statutory language emphasises suitability for self-sufficient and stand-alone use as a dwelling. Use as a “single” dwelling excludes, in our view, use as a dwelling joined to another dwelling.”

73. To the extent that the last sentence is read to mean that two single dwellings cannot be physically joined, for example by means of a dividing wall, I respectfully disagree. When the provisions were introduced it was widely recognised that it was expected that they would be used to assist the private lettings market by enabling landlords to buy blocks of flats for letting with reduced SDLT costs. The legislation is not restricted on its face to stand-alone properties and I see no reason to apply such a restriction.

74. However, I respectfully agree with the statement that the property must be “self-sufficient”, just as each individual flat in a block of flats would be “self-sufficient”. Indeed, that concept of self-sufficiency results from the use of the word “single” as I have described above.

Application of the principles to the Disputed Area as a whole

75. I now turn to consider the application of the rules to the alternative bases on which the Appellants have claimed MDR, starting with the initial basis of the entire Disputed Area, as shown marked yellow in the plan in Appendix 1, consisting of the Bedroom, its ensuite shower room, the Utility Room and the lobby area between the Utility Room and the external door.

76. The following features support concluding that the Disputed Area is suitable for use as a single dwelling:

(1) the Disputed Area includes areas for basic human needs: sleeping, personal hygiene, washing of laundry and preparation of food and access to drinking water;

(2) the Bedroom is comfortably big enough to have room for somewhere to sit;

(3) it can be accessed through the French windows in the bedroom without the need to access the Main Property;

(4) alternatively, it can be accessed through the external door to the lobby beside the Utility Room. Although that is also an area accessed by the Main Property, that lobby can be viewed as the equivalent of a communal lobby or entrance in a block of flats.

However, the fact that the doors between the Bedroom and the hallway of the Main Property, the Utility Room and the hallway of the Main Property and the lobby by the Utility Room to the kitchen are not lockable weighs heavily against finding that it is suitable for use as a single dwelling.

77. In Ramdhan the High Court stated that:

common sense would suggest that there are many different ways in which separateness (and a sufficient degree of privacy) can be achieved such as to give rise to a rational conclusion that there are two or more self‑contained units in a property, for instance by stairs or simply by geographical separation.

78. I respectfully agree with the panel in Fiander when expressing concern about the direct application of statements made in that case addressing a different term - separate living accommodation - rather than “single dwelling”. It is also important to recognise the context and purpose of the differing legislative provisions: in Ramdhan the test is used to impose Council Tax, whereas the provisions before me concern the application of a relief from tax.

79. However, whether or not the approach adopted in Ramdahn is adopted, at the time of completion of the Property there was no “separateness” achieved for the Disputed Area whether by lockable doors or other features.

80. I have explained above why I consider that the assessment of the Disputed Area should be as at the date of completion without modifications such as the addition of locks. However, even if such modifications could be taken into account I find that, as identified by Dr Schryber, in this case the Appellants have not shown that fitting locks would be possible under fire regulations. The burden of proof is on the Appellants to show that the Disputed Area is suitable for use as a single dwelling; it is not for HMRC to provide fire regulation evidence as suggested by Mr Cannon.

81. I also consider that the following features of the Disputed Area are particularly relevant to the assessment of whether it is suitable for use as a single dwelling and weigh against such a conclusion:

(1) the fact that the occupier of the Disputed Area would need to walk outside to go from the Bedroom to the Utility Room and the Utility Room. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that the Utility Room has not been shown to be suitable for sitting in to eat as it contains a toilet and on the basis of the photographs and plan has insufficient space for seating. The occupier would therefore need to carry food prepared in the Utility Room back to the Bedroom to eat. This consequently undermines the coherence of the Disputed Area as a single dwelling; and

(2) the fact that the hot water control and part of the control for the central heating is located in the Utility Room with no separate control for the Main Property. Realistically arrangements would have to be put in place to allow the Main Property access to those controls and to agree the settings to be applied to the hot water and heating, or to agree that the occupier of the Disputed Area controlled those settings. No such arrangements were in place at the time of the purchase of the Property and the feasibility of the occupiers of the Main Property being satisfied to proceed on any such basis must be in very real doubt if the Disputed Area was occupied by people with no family connections or other bonds. I am satisfied that the phrase use as a “single dwelling” implies that the property in question should be capable of being occupied by independent third parties. Mr Cannon submitted that the situation would be comparable to blocks of flats where the occupants do not control the heating and hot water settings, but I do not agree. This is equivalent to one flat having control of another’s heating and hot water; not a pre-set system independent of each occupier’s whims.

82. I respectfully agree with the panel in Fiander that the existence of shared utility meters is more neutral in this assessment. (In contrast, if there had been separate utility meters that would have been an important feature weighing in favour of finding that the property was suitable for use as a single dwelling.)

83. Similarly, the lack of a separate postal address or Council Tax assessment has little impact. Those are features which would be expected where a property is already used as a single dwelling rather than simply being suitable for use as such.

84. I conclude that given the features described, those which weigh against the Disputed Area being found to be suitable for use as a single dwelling outweigh the features which are in favour of finding it to be so. As a result I conclude that the Disputed Area is not suitable for use as a single dwelling.

Application of the principles to the Bedroom alone

85. The alternative basis relied upon by the Appellants to claim MDR is that the Bedroom (including the ensuite shower room) is suitable for use as a single dwelling.

86. The following features support concluding that the Bedroom is suitable for use as a single dwelling:

(1) the Bedroom includes areas for the basic human needs of sleeping and personal hygiene;

(2) the Bedroom is comfortably big enough to have room for somewhere to sit;

(3) it can be accessed through the French windows in the Bedroom without the need to access the Main Property;

87. Mr Cannon sought to argue that it is not necessary for a property to include a kitchen in order for it to be treated as suitable for use as a single dwelling, relying, in particular, on the Uratemp case and the potential for an occupant of such a property to rely on having sufficient space to use a microwave, ready meals and deliveries. HMRC have conceded that the lack of a kitchen is not necessarily determinative and I agree with that approach.

88. With sufficient space in the Bedroom’s walk-in wardrobe to be able to plug in a microwave and to prepare food it would be entirely possible for meals to be prepared without even having to rely upon ready meals and deliveries. However, at the time of completion of the purchase the walk-in wardrobe was set up as just that. While it had a plug socket the evidence does not show that it had a surface on which a microwave could be placed and food prepared. For the reasons explained earlier the relevant time is the time of completion of the purchase with the features present at that time.

89. Even if I took into account the possibility of providing such a surface in the walk-in wardrobe, there is no plumbing for a sink in the wardrobe. Washing-up would therefore need to be done in either the small hand basin in the ensuite shower, or as Mr Cannon suggested, by filling a plastic washing-up bowl and carrying it across the bedroom from one side to the other to get from the shower room to the wardrobe area. The suitability as a single dwelling is being stretched to, if not beyond, its reasonable limits.

90. Overall the lack of food preparation and washing up facilities weighs against the Bedroom being suitable for use as a single dwelling, although it is not determinative.

91. I consider it also to be relevant, although not argued before me, that the Appellants have not shown that there would be access to fresh drinking water in the Bedroom alone. It is more likely than not that the cold water in the shower room would be tank fed.

92. The Property is not in a city centre where it may be easiest for a person with sufficient means to access take-away meals, food deliveries and a launderette, but it is also not remote. Its location on the outskirts of Lancaster does not have a significant impact on the features needed to make it suitable for use as a single dwelling.

93. However, a significant issue for the Bedroom is that faced by the Disputed Area in not having a lockable door or other feature separating it from the Main Property. As explained in the context of the Disputed Area I consider this to be a fundamental issue in determining whether the Bedroom is suitable for use as a single dwelling.

94. In addition, the Bedroom has no access to the heating and hot water controls located in the Utility Room. I refer to the conclusions reached above in the context of the Disputed Area. In this case the occupier of the Bedroom would have no ability to control the hot water feeding the ensuite bathroom and limited ability to control the heating (other than via direct control of any radiators). For the same reasons stated above, I find this weigh against concluding that the Bedroom is suitable for use as a single dwelling.

95. I conclude that given the features described, those which weigh against the Bedroom being found to be suitable for use as a single dwelling outweigh the features which are in favour of finding it to be so. As a result, I conclude that the Bedroom is also not suitable for use as a single dwelling.

conclusion

96. For all these reasons the appeal is DISMISSED. The decision made by HMRC that the chargeable transaction by which the Property was purchased does not qualify for MDR is confirmed.

Right to apply for permission to appeal

97. This document contains full findings of fact and reasons for the decision. Any party dissatisfied with this decision has a right to apply for permission to appeal against it pursuant to Rule 39 of the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Tax Chamber) Rules 2009. The application must be received by this Tribunal not later than 56 days after this decision is sent to that party. The parties are referred to “Guidance to accompany a Decision from the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber)” which accompanies and forms part of this decision notice.

TRACEY BOWLER

TRIBUNAL JUDGE

RELEASE DATE: 16 MARCH 2021

Appendix

(not to scale)