Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

First-tier Tribunal (Tax)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> First-tier Tribunal (Tax) >> Mehrban v Revenue & Customs () [2021] UKFTT 53 (TC) (25 February 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2021/TC08039.html

Cite as: [2021] UKFTT 53 (TC), [2021] STI 1438

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

[2021] UKFTT 53 (TC)

TC08039

[2012] UKUT 770 (TCC)

Pattullo v HMRC [2016] UKUT 270 (TCC), Anderson v HMRC [2018] UKUT 159 (TCC), HMRC v Tooth [2019] EWCA Civ 826 considered and applied.

|

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL TAX CHAMBER |

|

Appeal number: TC/2017/05544 TC/2018/03918 TC/2018/05308 |

BETWEEN

|

|

KASHIF MEHRBAN |

Appellant |

-and-

|

|

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HER MAJESTY’S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS |

Respondents |

|

TRIBUNAL: |

JUDGE ASIF MALEK JULIAN SIMS |

The hearing took place on 30 November 2020 - 2 December 2020. The form of the hearing was V (video). A face to face hearing was not held because it was just, proportionate and in the interest of justice for the hearing to be conducted by video. The documents to which we were referred to are (a) bundle of documents produced by the Respondent, (b) a bundle of documents produced by the Appellant and (c) skeleton arguments produced by both parties.

Prior notice of the hearing had been published on the gov.uk website, with information about how representatives of the media or members of the public could apply to join the hearing remotely in order to observe the proceedings. As such, the hearing was held in public.

Mr. Alexander Gow, an accountant, for the Appellant

Mr. J Nicholson, litigator of HM Revenue and Customs’ Solicitor’s Office, for the Respondents

DECISION

Introduction

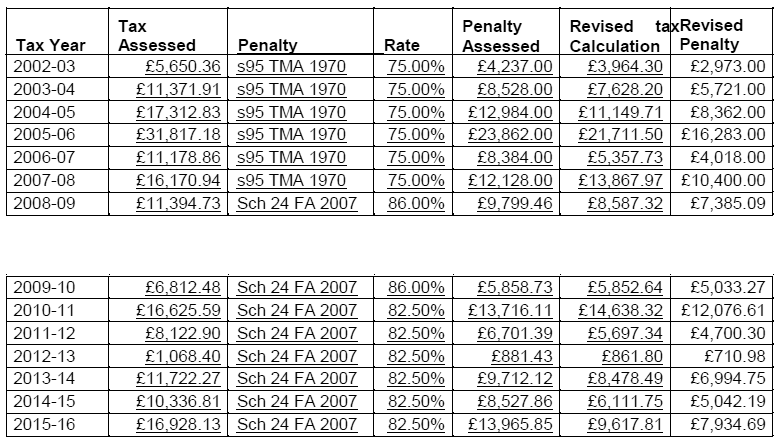

1. These are appeals against assessments made by the Respondent under section 29 of the Taxes Management Act 1970 (the “TMA 1970”) on 21 April 2017. The years in question are the tax years 2002/03 to 2015/16 and the total amount assessed was £176,513.39. In addition the Respondents assessed the Appellant to penalties in the sum of £70,123 on 22 September 2017 under section 95(1) of the TMA 1970 and £69,162.95 on 21 September 2017 under schedule 24 of the Finance Act 2007.

2. By the time of the hearing the Respondents no longer sought to maintain these assessments and penalties, but invited us to revise them as follows:

[table and figures taken from the Respondent’s skeleton argument]

3. Before us, it was submitted on behalf of the Respondents, that we were entitled to increase or decrease the assessment further to our power under section 50 of the TMA 1970. No issue was taken with this submission on behalf of the Appellant. We accordingly proceeded to hear the appeals on that basis.

The law

Legislative framework

4. Section 29 of the TMA 1970 provides:

“(1) If an officer of the Board or the Board discover, as regards any person (the taxpayer) and a [year of assessment]-

(a) that any [income which ought to have been assessed to income tax, or chargeable gains which ought to have been assessed to capital gains tax,] have not been assessed, or, or

(b) that an assessment to tax is or has become insufficient, or

….

the officer or, as the case may be, the Board may, subject to subsections (2) and (3) below, make an assessment in the amount, or the further amount, which ought in his or their opinion to be charged in order to make good to the Crown the loss of tax…

(3) Where the taxpayer has made and delivered a return under [section 8 or 8A] of this Act in respect of the relevant [year of assessment], he shall not be assessed under subsection (1) above-

(a) in respect of the [year of assessment] mentioned in that subsection; …unless one of the two conditions mentioned below is fulfilled.

(4) The first condition is that the situation mentioned in subsection (1) above [was brought about carelessly or deliberately by] the taxpayer or a person acting on his behalf…”

5. Section 29 of the TMA 1970 is circumscribed by sections 34 and 36 of the TMA 1970. That is to say that there are no separate time limits for assessments raised pursuant to section 29. In broad terms, with effect from 1 April 2010, the normal time limit for raising an assessment of four years is extended to six years for careless behaviour and to twenty years in the case of deliberate behaviour. Prior to 1 April 2010 the time limit for raising a discovery assessment where there has been fraudulent or negligent conduct was 20 years after 31 January following the end of the year of assessment concerned.

Burden and standard of proof

6. It was accepted before us that it was for the Respondents to show, in respect of the section 29 TMA 1970 assessments, that they had made a discovery that income which ought to have been assessed has not been assessed and that this was brought about by the careless or deliberate conduct of the taxpayer or someone acting on his or her behalf.

7. If the Respondents are able to satisfy us that they have properly made a discovery, as set out above, the burden then shifts on the Appellant to show that the assessment made is incorrect.

8. The burden of proof, in respect of any penalties, is upon the Respondents.

9. The standard of proof in each case is the “balance of probabilities”.

Evidence: documents, witnesses and findings of fact

Documents

10. As might be expected in appeals relating to assessments covering such a prolonged period of time, as in this case, there were a large amount of documents for us to review. Unfortunately, the way that the bundle containing these documents was prepared for this Tribunal was wholly inadequate. The bundle that we had contained multiple paginations and multiple copies of the same document. In addition, the Appellant had his own bundle which was sent to us part-way through the hearing and his advocate did not have or use the bundle that was before us. This all made the hearing more time consuming and difficult then it needed to be. Despite these difficulties we were able to adequately view the relevant documents and given the generous time allocated for the hearing we were able to finish the hearing well within time.

11. More disturbingly it was alleged by the Appellant that a large amount of documents pertinent to this appeal (including z till receipts for the relevant periods, etc) were “uplifted” by the Respondents and subsequently lost. This is not denied by the Respondents. It is difficult to overestimate the significance of this from an evidential point of view. It is likely that the Appellant has been hampered in his preparation of his appeal by the loss of those documents. It is, of course, impossible for us to tell to what extent without seeing the documents. However, we are obliged, in our view, to take this into account when we come to assessing the evidence.

Witnesses

12. The Respondents called Ms. Gregson, Mr. Goodliffe, Ms. Hillard, Mrs. Goodliffe, Mrs. Russon and Mr. Metcalfe. The first three carried out “test purchases” (about which more later), Mrs. Goodliffe works in the VAT compliance team and Mrs. Russon and Mr. Metcalfe work in the Fraud and Bespoke Avoidance team. There were in the bundles before us witness statements produced by the latter three. We allowed these statements to stand as the witnesses’ evidence in chief. The first three witnesses did not produce witness statements. However, these witnesses were tendered largely to introduce their notes of the test purchases that they had carried out. They were asked to confirm that they had written the respective documents to be found at pages 139-148 of the bundle and then tendered for cross examination. No objection was taken by the Appellant to proceeding in this way.

13. The Appellant relied upon his own witness statement and we accepted this statement as his evidence in chief.

14. All the witnesses gave evidence after providing the relevant affirmation in line with the current guidance on remote hearings. There was an opportunity for witnesses to be cross-examined and we also had an opportunity to put questions. Whilst there was some difficulty with Mrs. Goodliffe’s connection for a period during the hearing, we were able to properly assess all the evidence before us and neither the parties nor the witnesses were, in our judgment, hampered to any great extent in being able to fully participate in the hearing.

15. The findings in relation to each witness are set out below.

Findings of fact

16. Needless to say, we have read all the statements, heard all the evidence and reviewed the documents that we have been taken to. It is, of course, neither necessary nor desirable for us to burden this judgment with all the factual detail that was before us. What follows below is a summary of our pertinent and relevant findings.

17. The Appellant owns and operates a retail store at 112 Burnley Rd, Accrington BB5 6DW which, at the relevant time sold newspapers and magazines, alcohol, tobacco products and other general household goods. In addition, the Appellant operated a “Paypoint” and “Payzone” terminal (which allowed customers to make bill payments in store) and a national lottery terminal.

18. The Appellant is not married, has no children and lives a modest lifestyle. He has not travelled abroad for over 30 years. He works 7 days a week for 364 days a year and takes no holidays.

19. On 21 March 2013, Mrs. Goodliffe (along with three colleagues) made an unannounced visit to the Appellant’s business premises for the purposes of checking the credibility of the Appellant’s VAT and income tax returns. She, or one of her colleagues, was told by the Appellant’s father (who was working at the time) that the till used in the business was unreliable.

20. On 21 May 2013 Mrs. Goodliffe undertook a second unannounced visit to the Appellant’s business premises. Not finding the Appellant at the premises she asked him to call her back. When he did on the following day she conducted an interview with him over the telephone. Her note of this call [page 642] shows that the Appellant told her that he has a daily float of £100 in the till, that all sales including Payzone and lottery are rung through the till, he does a daily Z read from the Payzone and lottery machines and takes out the equivalent cash, deducts £100 for his float and the remainder represents his Gross Daily Takings (“GDT”). He records his GDT on a scrap piece of paper and writes the weekly total in a simplex D book as a bulk entry for the whole of the week. She ended the call by telling the Appellant that a visit would be booked and that all his business records were required.

21. Mrs. Goodliffe thereafter analysed the Appellant’s VAT returns and formed the view that the DGT had not been recorded everyday with only a weekly total being noted in the business records and that DGT of approximately £400 declared for a shop open 17 hours a day were not credible.

22. Following receipt of records from the Appellant’s accountant on 19 July 2013, Mrs. Metcalfe and Mr. Cullen undertook a late night cash up exercise on 12 September 2013. This revealed an excess of £400 in the till. The Appellant’s explanation was that he had left the additional cash in the till in order to pay for a delivery from KAKA cash & carry that day, but that he had only received around £500 in stock as opposed to the £1,500 that was expected.

23. On 25 September 2013 Mrs Goodliffe analysed purchases made by the Appellant over the past four years establishing to her satisfaction that at no time had there been such a large purchase previously. She concluded that the Appellant’s explanation for the additional cash in the till was not credible.

24. On 7 January 2014 Mrs Goodliffe and Mr Cullen carried out a further visit to the Appellant’s premises and asked him to complete self-invigilation sheets noting down all sales.

25. On 28 January 2014 Mrs Goodliffe attended the Appellant’s premises to collect the invigilation sheets to be told by the Appellant that he had stopped completing them. Mrs Goodliffe handed the Appellant a covering letter explaining how to complete the self-invigilation sheets, provided him with a further 100 sheets and confirmed the dates for which the sheets needed to be completed.

26. On 29 January 2014 Mrs Goodliffe formed the view that the completed invigilation sheets were inaccurate and that test purchases needed to be undertaken to establish whether or not the Appellant was accurately completing the invigilation sheets.

27. Test purchases were conducted during the period 12 February 2014 and 25 February 2014. These purchase were, for obvious reasons, conducted by other HMRC officers; however, Mrs Goodliffe co-ordinated these and was provided with a report by each officer.

28. On 20 March 2014 Mrs. Goodliffe collected the remainder of the invigilation sheets from the Appellant and compared these with the test purchases, concluding on 25 March 2014 that 70% of the test purchases had not been recorded on the invigilation sheets and as such she suspected that the DGT were understated by a comparable amount.

29. Mrs. Goodliffe also analysed information obtained from Bestways cash & carry which showed purchases made by the Appellant for the period 1 January 2013 - 31 March 2013 to be £25,294.19. The Appellant’s business records showed purchases in the sum of £6,482.55 for the same period. She, accordingly, came to the conclusion that purchases had been suppressed by the Appellant for the same period in the amount of £18,811.64.

30. By this time Mrs. Goodliffe had concluded that both purchases and sales had been understated by the Appellant and she made a referral to the fraud investigation team for the Appellant to be investigated under the COP 9 procedure.

31. On referral to her, Mrs. Russon, an officer in the Fraud and Bespoke Avoidance Team, first conducted a review of the Appellant’s tax affairs in June 2014. She opened an investigation under COP 9 writing to the Appellant on 12 September 2014 to inform him that the Respondents suspected that he had committed tax fraud and invited him to enter into a Contractual Disclosure Facility (“CDF”) to avoid criminal prosecution by making a complete and accurate disclosure of all tax irregularities.

32. The Appellant made a disclosure statement on 7 November 2014. In this statement he accepted that during the period November 2009 and November 2013 his sales were understated by approximately £125 per week and that his cost of sales figure had been overstated. He accepted that his taxable profits had been understated.

33. There then follows correspondence between Ms Russon, the Appellant and the Appellant’s advisors for the period 25 November 2014 - May 2016. The general purpose of the correspondence was for Ms Russon to obtain further information. There was a delay in the provision of some of the information on the part of the Appellant due to his ill-health.

34. Between May 2016 - August 2016 Ms Russon (together with Mr Metcalfe- an officer of the Respondents and a direct taxes specialist) analysed the information. In June 2016 Ms Russon concluded that there had been a loss of tax caused to the Respondents and she believed that the Appellant had suppressed both sales and purchase information and had, as a consequence, under-declared his income on his returns for 2002/03 - 2015/16.

35. On 30 August 2016 Ms Russon wrote to the Appellant setting out her view and the assessments that she intended to issue.

36. There then followed further correspondence between the parties culminating in an assessment under section 29 of the TMA 1970 made by Mr Metcalfe on 21 April 2017. The Appellant was informed of the Respondents decision to impose penalties by letter dated 22 September 2017.

discussion

Discovery assessments

37. Discovery has featured in the tax system for at least two hundred years (see the 1803 Act (43 Georgii III cap 122)). However, its nature has significantly changed over the years. The advent of self-assessment represented a key turning point. Prior to self-assessment the tax-payers obligation was to submit a return and it was for the Inspector to make an assessment of the amount due. After the introduction of self-assessment the burden of assessment fell on the taxpayer.

38. The change to self- assessment necessitated a change in the way that discovery operated. Parliament saw fit to impose limits on discovery in recognition of the additional burdens. In particular it sought to impose strict time limits. In Tower McCashback LLP v HMRC [2010] EWCA Civ 32 the Court of Appeal, at paragraph 24 of their judgment, summarised the position as follows:

“As I have already observed, apart from a Closure Notice, and the power to correct obvious errors or omissions, the only other method by which the Revenue can impose additional tax liabilities or recover excessive reliefs is under the new s.29. That confers a far more restricted power than that contained in the previous s.29. The power to make an assessment if an Inspector discovers that tax which ought to have been assessed has not been assessed or an assessment to tax is insufficient or relief is excessive is now subject to the limitations contained in s.29(2) and (3) (s.29(1)). S.29(2) prevents the Revenue making an assessment to remedy an error or mistake if the taxpayer has submitted a return in accordance with ss.8 or 8A and the error or mistake is in accordance with the practice generally prevailing when that return was made. S.29(3) prevents the Revenue making a discovery assessment under s.29(1) unless at least one of two conditions is satisfied (s.29(3)). The prohibition applies unless the undercharge or excessive relief is attributable to fraudulent or negligent conduct (s.29(4)) or having regard to the information made available to him the Inspector could not have been reasonably expected to be aware that the taxpayer was being undercharged or given excessive relief (s.29(5)). There are statutory limitations as to the time at which the sufficiency or otherwise of the information must be judged. These provisions underline the finality of the self-assessment, a finality which is underlined by strict statutory control of the circumstances in which the Revenue may impose additional tax liabilities by way of amendment to the taxpayer's return and assessment.”

39. A review of the subsequent case law gives us the following principles:

(1) “…no new information, of fact or law, is required for there to be a discovery. All that is required is that it has newly appeared to an officer, acting honestly and reasonably, that there is an insufficiency in an assessment. That can be for any reason, including a change of view, change of opinion, or correction of an oversight. The requirement for newness does not relate to the reason for the conclusion reached by the officer, but to the conclusion itself.” (emphasis added) [HMRC v Charlton Corfield & Corfield [2012] UKUT 770 (TCC).]

(2) The above paragraph was cited with approval by Lord Justice Floyd in HMRC v Tooth [2019] EWCA Civ 826 wherein he also distinguished between what must be discovered and the reasons for making the discovery. At paragraphs 60 & 61 of the his judgement he said:

“60. Both parties accepted that the legal approach to whether there is a "discovery" is correctly set out in this first passage from the decision of the UT in Charlton & others v RCC [2012] UKUT 770 (TCC); [2013] STC 866 at [37], where the tribunal said:

"37. In our judgment, no new information, of fact or law, is required for there to be a discovery. All that is required is that it has newly appeared to an officer, acting honestly and reasonably, that there is an insufficiency in an assessment. That can be for any reason, including a change of view, change of opinion, or correction of an oversight."

The UT continued in a second passage:

"The requirement for newness does not relate to the reason for the conclusion reached by the officer but to the conclusion itself. If an officer has concluded that a discovery assessment should be issued, but for some reason the assessment is not made within a reasonable period after that conclusion is reached, it might, depending on the circumstances, be the case that the conclusion would lose its essential newness by the time of the actual assessment."

61. I agree with the UT's approach in both passages. The requirement for the conclusion to have "newly appeared" is implicit in the statutory language "discover". The discovery must be of one of the matters set out in (a) to (c) of section 29(1). In the present case the officer must have newly discovered that an assessment to tax is insufficient. It is his or her new conclusion that the assessment is insufficient which can trigger a discovery assessment. A discovery assessment is not validly triggered because the officer has found a new reason for contending that an assessment is insufficient, or because he or she has decided to invoke a different mechanism for addressing an insufficiency in an assessment which he or she has previously concluded is present.

(3) In the same case ( HMRC v Tooth [2018] UKUT 38 (TCC)) the Upper Tribunal explained at paragraph 79 “…the same officer (or officers) cannot make the same discovery twice. We see no reason, however, why the same officer cannot, for different reasons, discover that one of the situations set out in section 29(1)(a), (b) or (c) pertains a second time. Suppose an officer discovers that an assessment to tax has become insufficient for a certain reason, but HMRC decides not to issue an assessment because the point is controversial and the amount small. Suppose that officer then - for different reasons - discovers that the assessment has become insufficient. We consider that this, second, discovery could justify the making of an assessment. The position is, obviously, a fortiori where two different officers are independently involved. Again, provided the basis for the discovery is different, there is a statutory basis under section 29(1) for issuing two assessments. What, however, if two different officers independently make the same discovery? In our judgment, as a matter of ordinary English, a discovery can only be made once. We accept that section 29(1) TMA is framed by reference to the subjective state of mind of an officer or the board, but what is a “discovery” is an objective term. It seems to us that in this case, the first officer makes the discovery; the second officer simply finds out something that is new to him. In particular if one officer is made aware of, and accepts, the conclusion of another officer it cannot be said that the first officer made a discovery”

(4) A discovery can become stale. In Pattullo v HMRC [2016] UKUT 270 (TCC) the Upper Tribunal held at paragraph 52 “The context makes it clear that an assessment may be made if and when it is discovered that the assessment to tax is insufficient. It would, to my mind, be absurd to contemplate that, having made a discovery of the sort specified in s 29(1), HMRC could in effect just sit on it and do nothing for a number of years before making an assessment just before the end of the limitation period specified in s 34(1)”. However, it circumscribed the application of the doctrine in the next paragraph as follows “… the word “if”, as used in this way in the sub-section, does not mean “immediately”. Mr Gordon was right, in my view, to accept that the discovery could be kept fresh for the purposes of being acted upon later. As he accepted, each case would turn on its particular facts. He gave the example of notification being given to the taxpayer of the discovery in the expectation that matters could be resolved without the need for a formal assessment to be made. No doubt there are many other examples which could be given. The UT in Charlton at para 37 recognise that the decision in each case will be fact sensitive. I do not think it would be helpful to try to define the possible circumstances in which a discovery would lose its freshness and be incapable of being used to justify making an assessment. But I consider that Mr Gordon was right to accept that it would only be in the most exceptional of cases that inaction on the part of HMRC would result in the discovery losing its required newness by the time that an assessment was made”. The issue of staleness was more recently considered in Clive Beagles v HMRC [2018] UKUT 380 (TCC) where the Upper Tribunal rejected the submission that there was no concept of staleness and followed Patullo.

(5) In Anderson v HMRC [2018] UKUT 159 (TCC) the Upper Tribunal set out the following key principles in relation to discovery after reviewing the authorities, which we readily adopt:

“ (1) s 29(1) refers to an officer (or the Board) discovering an insufficiency of tax;

(2) the concept of an officer discovering something involves, in the first place, an actual officer having a particular state of mind in relation to the relevant matter; this involves the application of a subjective test;

(3) the concept of an officer discovering something involves, in the second place, the officer’s state of mind satisfying some objective criterion; this involves the application of an objective test;

(4) if the officer’s state of mind does not satisfy the relevant subjective test and the relevant objective test, then the officer’s state of mind is insufficient for there to be a discovery for the purposes of sub-s (1);

(5) s 29(1) also refers to the opinion of the officer as to what ought to be charged to make good the loss of tax; accordingly, the officer has to form a relevant opinion and such an opinion has to satisfy some objective criterion;..”

(6) In Anderson the Upper Tribunal also elaborated upon the test to be applied and suggested the following formulations:

(a) For the subjective element for a discovery assessment to be satisfied “The officer must believe that the information available to him points in the direction of there being an insufficiency of tax.”, and

(b) For the objective element “as regards the requirement for the action to be “reasonable”, this should be expressed as a requirement that the officer’s belief is one which a reasonable officer could form. It is not for a tribunal hearing an appeal in relation to a discovery assessment to form its own belief on the information available to the officer and then to conclude, if it forms a different belief, that the officer’s belief was not reasonable.”

(7) There is a very real “moment” of discovery. The Upper Tribunal in HMRC v Charlton Corfield & Corfield [2012] UKUT 770 (TCC) explained it as follows:

“…the word ‘discovers’ does connote change, in the sense of a threshold being crossed. At one point an officer is not of the view that there is an insufficiency such that an assessment ought to be raised, and at another he is of the view”.

What was the nature of the discovery?

40. Although this was not a point explicitly addressed by either of the party it is one that we need to consider first and foremost. There can be little doubt that a discovery must pertain to either s.29(1)(a), (b) or (c). In the present case it was implicit from the Respondents’ skeleton argument [paragraph 53] that they referred to section 29(1) (b) - i.e. “that an assessment to tax is or has become insufficient …”. Yet, it is arguable, given what is said at paragraph 49 of the same skeleton argument, that the Respondents proceed on the basis that the discovery was one of an income that ought to have been assessed not being so assessed under section 29(1)(a). For the purposes of this appeal nothing turns on the distinction.

When was the discovery made and by whom?

41. In our view, having established the nature of the discovery the next point of order must be to establish when the discovery was made and by whom. This must be right if there is to be a “threshold” to be crossed and if we are to examine the state of mind of an actual officer.

42. In the present case the Respondents’ skeleton argument at paragraph 53 says only this:

“The Respondents submit that a discovery of an insufficiency of tax was made following the self-invigilation exercise, test purchases, unannounced visits, purchase review, subsequent enquiries by HMRC officers and the exchange of correspondence.”

43. During closing we pointed out to Mr. Nicholson that, given the period over which the enquiry into the Appellant’s affairs was conducted, this represented a wide range of time and invited him to “pin his colours to the mast”. Mr. Nicholson first volunteered that it might have been Mr. Metcalfe who first made the discovery just prior to the assessments being issued. He then thought that it might be Mrs. Russon when she formed her suspicions that the Appellant had been involved in fraud. He also submitted that if there had been delay then it had been caused by the Appellant and that the discovery was not “stale” by the time the assessment was raised. Mr. Gow had nothing to say on the point at all.

44. Based upon our findings of fact, as set out above, we have concluded that Mrs. Goodliffe was the first officer who might have made a discovery. By around 25 March 2014 she had:

(1) concluded that the DGT were not being recorded on a daily basis, and that the DGTs being declared were not credible,

(2) conducted a cash-up exercise which had revealed excess cash of around £400 in the till on the evening concerned,

(3) obtained invigilation sheets from the Appellant and concluded that they were inaccurate,

(4) conducted test purchases which revealed that sales appeared to be understated by about 70%, and

(5) concluded that purchases had been suppressed in the Appellant’s records by around £18,811.64 over a three month period.

45. In fact not only did she come to the above conclusions, but also decided that the Appellant ought to be referred for investigation for fraud under the COP9 procedure.

46. It is clear that, by this point, Mrs. Goodliffe had come to the view that the information available to her, at the very least, pointed to there being an insufficiency of tax or a failure to assess income to tax which ought to have been assessed. Otherwise why continue with the investigation and why involve a specialist colleague from another department?

47. We next consider the objective element of the test. We ask ourselves the question was the view formed by Ms Goodliffe one which a reasonable officer could form? It clearly was and is supported by the fact that two other officers (Ms Russon and Mr Metcalfe) also formed the same view. For our part we find it difficult to imagine how, based upon what was known to Ms Goodliffe at the time, another officer could have come to a different view.

48. Therefore, in our judgment Ms Goodliffe discovered that there had been an insufficiency in the tax charged, at the very latest on or around 25 March 2014.

49. Before closing on this topic we should further like to say a word or two about the test for discovery as set out in the authorities we have referred to, and in particular as postulated in Anderton. The current authorities envisage a low bar or threshold vis a vis the subjective element of the test. The matter need only “newly appear” to the discovering officer or put in another way s/he need only believe that the information available points to an insufficiency. There is no requirement for the officer to think or express himself in probabilistic terms or harbour deep or well-founded suspicions. Indeed, it might be possible for a Tribunal to conclude that a discovery had been made by an officer even when the officer thought that s/he had not yet made a discovery, or as may well be the case in this appeal, the relevant officer had not properly addressed his/her mind to it. This is because of the ease with which a discovery can be made. The wide ranging effect of such a test is only emolliated by the second, objective, part of the test. That is to say the officer must act reasonably and honestly. Whether an officer has done so will depend upon all the circumstances of the case.

Could the discovery have been made by Ms. Russon or Mr. Metcalfe in addition or as an alternative?

50. In our view the authorities, as they currently stand, are clear that a discovery can only be made the once. If a different officer makes the same discovery (even independently) then the second officer simply finds out something new to him and it is the first officer, in time, that makes the discovery. Whilst, of course, it may be the case that the reasons for the discovery may be different or may change over time - the discovery itself remains unaffected. The reasons are merely a different route to the same destination.

51. In the present case Mrs. Russon and Mr. Metcalfe did not make a discovery. They merely found out something new - namely that the Appellant’s assessments to tax had become insufficient or that the Appellant had failed to assess income to tax which ought to have been so assessed. In addition they may have had supplemental reasons for reaching the conclusion that Ms Goodliffe had reached; but that does not add anything more to the debate.

Can a discovery become “stale”; and if so, did it do so in the present case?

52. Having found that Mrs. Goodliffe discovered that there was an insufficiency of tax on or around 25 March 2014 we turn next to the question of whether that discovery had become “stale” by the time that the assessments were made on 21 April 2017. This represents an interval of over three years and, on the face of it, an exceptional period of delay.

53. There has been some doubt cast on whether or not staleness as a concept exists. In our view there can be little doubt. The word “discover” connotes an element of newness or freshness. It would be an absurdity to hold otherwise. Our view on this issues is clearly supported by the authorities cited earlier in this judgment.

Can the ‘discovery clock’ be paused by virtue of the conduct of one of the parties?

54. It was submitted before us that the delay was not caused by the Respondents, but by the Appellant. As such the Respondents had not “sat on their hands”. This is a crucial point - must there be some sort of delay or poor conduct attributable to the Respondents before this Tribunal can conclude that the discovery is stale? We do not understand the decision in Patullo in this way. At paragraph 52 Lord Glennie simply makes the point that it would be absurd to allow HMRC to make an assessment just before the end of the limitation period specified by s 34(1) where they had delayed for a number of years and had simply sat on the discovery and done nothing else. He says nothing else in this regard. However, he is at pains to point out that he thought it would be unhelpful to define the possible circumstances in which a discovery would lose its freshness and that each case is fact sensitive.

55. It seems to us that examining the cause of the delay on the part of the Respondents in making an assessment following a discovery is unlikely to ever be helpful. The delay could be for a number of reasons ranging from a lack of resources through to waiting for further information or a decision. Take the example of a request for further information. The Respondents might seek to augment their discovery with requests for information. Those requests may turn into formal notices to provide information. Those notices might then be appealed. This is all likely to cause significant delay. However, that in our view, is completely irrelevant. The officer either had enough information to make a discovery or he did not. If he did then the information requested is otiose and the delay can be put squarely at his door. If he did not then he will not have made a discovery until he has had sufficient information.

56. In coming to this view we have regard to the precise words used in s.29 of the TMA 1970. The operative word being “discover”. Much ink has already been spilt in trying to decipher this word’s exact meaning in a number of decisions. For us the matter is straight forward. For there to be a discovery there must be something that ‘newly appears’. If there is nothing which ‘newly appears’ there can be no discovery. There is nothing implied or explicit which would lead us to the conclusion that we ought to weigh in the balance the conduct of the parties in coming to a decision as to whether or not something ‘newly appeared’ to an officer. It either did or it did not. Of course, there might well be some conduct on the part of the taxpayer (for example a failure to provide information or to co-operate) which might go to whether or not a discovery had been made. That must clearly be right. However, that is not the same as saying that because the taxpayer has caused delay the Respondent’s discovery has not gone stale.

57. We can find succour for this line of reasoning by making a comparison with decisions in the civil courts. The fact that an assessment becomes stale is closely analogous to the situation where there is an applicable limitation period in civil actions. There is a similar, but distinct, concept of laches which can be relied upon in equitable claims. The policy reasons for the existence of the defence of limitation was aptly summarised by Lord Sumption in Birmingham City Council v Abdulla [2012] UKSC 47. Whilst recognising the fact that Lord Sumption’s was not the majority decision and that the case concerned the limitation period applicable to claims brought under the Equal Pay Act 1970, we can do no better than to repeat his summary at paragraph 41 of his judgment:

“Limitation reflects a fundamental and all but universal legal policy that the litigation of stale claims is potentially a significant injustice. Delay impoverishes the evidence available to determine the claim, prolongs uncertainty, impedes the definitive settlement of the parties’ mutual affairs and consumes scarce judicial resources in dealing with claims that should have been brought long ago or not at all”

58. Before us the argument is made that there is conduct (causing delay) on the part of the Appellant which would mean that the discovery was not stale. We take this, essentially, as an argument that there should be a suspension of the running of time. That is to say that the clock measuring staleness should be stopped or suspended until the conduct is purged.

59. In the main work on limitation periods (a book of the same name by Andrew McGee) in the 8th edition one can see at paragraph 2.031 that the author is of the view that the general rule is that the English Law of limitation does not permit the running of time to be suspended once it has started, subject to five exceptions. He refers to the case of Prideaux v Webber (1661) 1 Lev. 31 as an example where even the suspension of the King’s law (during the commonwealth) did not prevent time from running. We probably do not need to go back quite so far in time in order to make good the general rule: that once started limitation periods are, generally, not suspended. There are five possible exceptions to the general rule which are interesting but remain well confined statutory exceptions. They are not relevant here.

60. Proceeding on the basis that staleness is akin to a limitation defence we can see no reason why the time limit, once started, ought to be suspended.

61. It might also be argued that the Respondents needed to be satisfied as to the amount of the “insufficiency” and that they needed to be sure that there was an “insufficiency” before making an assessment. In either case a hasty assessment is likely to mean an inaccurate assessment with the tendency for the Respondents to over and more frequently assess. It is clear that the Respondents are not obliged to make an assessment immediately upon discovery. However, to retain its newness the assessment must be made relatively soon thereafter. We accept that one officer might be more cautious than another and may even want to check that he has made a discovery with another. This is the subjective element of the test- it must “newly appear” to the particular officer. However, he must act objectively reasonably. If he remains unsure that a discovery has been made and it is objectively reasonable for him to hold that view then he is unlikely to have made a discovery. However, once he makes the discovery he cannot then be heard to say that he needs to delay because he must calculate the amounts due or to be sure that he has made the right decision. At this point he will have a reasonable period of time within which to make any calculations and assuage any doubts, but that cannot, after taking into account the nature and complexity of the assessments being made, be anything other than a relatively short period of time.

62. Suppose that the officer makes an assessment which is wrong and in that assessment he underassesses the taxpayer? Whilst that looks, at face value, like a good reason why the officer should be given significant latitude in complex cases, it misses the point. In these circumstances it is likely that the officer will have discovered something new to be able to make a fresh discovery enabling him/her to make a further assessment (providing always that it is objectively reasonable for him/her to do so).

63. In the present case there was a significant delay of over 3 years between the discovery and the assessment. We have concluded above that once the discovery clock has started it is not paused by reason of the fact that the officer seeks further information which is not forthcoming. Accordingly, we reject the Respondents submission on this point and conclude that by the time that the assessments were made the discovery had become stale. The Respondent is not, therefore, entitled to raise assessments under s.29 of the TMA 1970.

Remaining issues

64. Given our decision above it is not necessary for us to go on to deal with the other issues thrown up by this appeal.

conclusion and other practical matters

65. For the reasons that we give above we allow the appeals. However, we are aware that the law considered in this decision (namely discovery assessments under s.29 of the TMA and in particular the concept of staleness) relates to an area where there is an emerging body of case law which must, necessarily, affect our decision. We have considered the case law as it is at the date that this decision has been promulgated; but we are aware, in particular, that

(1) the decision in Tooth has been appealed to the Supreme Court and is due to be heard soon,

(2) The decision in Clive Beagles v HMRC [2018] UKUT 380 (TCC) has been appealed to the Court of Appeal, and

(3) In Beagles the Upper Tribunal concluded that given the state of the authorities on the question of whether a discovery is capable of becoming “stale” it is a matter best left to the higher courts.

66. Accordingly, we should have no hesitation in granting permission for the Respondents to appeal our decision to the Upper Tribunal in the event that such permission is sought.

67. It is also worth noting that the parties spent a considerable amount of time, both at the hearing, and in preparation, in dealing with all of the other factual and legal issues that necessarily arose in this appeal. It seems to us that much time, energy and expense could have been saved if the “discovery issue” had been dealt with as a preliminary issue under Rule 5(e) of the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) Rules Consolidated version - as in effect from 21 July 2020 (the “Rules”). Even where the preliminary issue hearing does not dispose of the entire matter it will dispose of at least one of the issues and make it easier for the First Tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) to list, what will then have become, a shorter hearing. By analogy such an approach has served the Civil Courts well in cases where limitation is an issue. In such cases preliminary “limitation hearings” are the rule rather than the exception. We commend such an approach to the Respondents in future hearings involving “discovery” assessments.

Right to apply for permission to appeal

68. This document contains full findings of fact and reasons for the decision. Any party dissatisfied with this decision has a right to apply for permission to appeal against it pursuant to Rule 39 of the Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Tax Chamber) Rules 2009. The application must be received by this Tribunal not later than 56 days after this decision is sent to that party. The parties are referred to “Guidance to accompany a Decision from the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber)” which accompanies and forms part of this decision notice.

ASIF MALEK

TRIBUNAL JUDGE

RELEASE DATE: 25 FEBRUARY 2021