Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

First-tier Tribunal (Tax)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> First-tier Tribunal (Tax) >> Chelmsford City Council v Revenue & Customs (VAT - Local authority - sports and leisure facilities - whether economic activity) [2020] UKFTT 432 (TC) (17 October 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2020/TC07909.html

Cite as: [2021] SFTD 337, [2020] UKFTT 432 (TC)

[New search] [Contents list] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

[2020] UKFTT 432 (TC)

VAT - Local authority - sports and leisure facilities - whether economic activity - Art 9 PVD - whether engaging as a public authority - Art 13 PVD - Note 3 Group 10 sch 9 VATA 1994

|

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL TAX CHAMBER |

|

Appeal number: TC/2011/7816 |

BETWEEN

|

|

CHELMSFORD CITY COUNCIL |

Appellant |

-and-

|

|

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HER MAJESTY’S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS |

Respondents |

|

TRIBUNAL: |

JUDGE PETER KEMPSTER JUDGE ANNE SCOTT JUDGE ALASTAIR RANKIN

|

Sitting in public at Taylor House, London on 23-26 September 2019

Amanda Brown and Adam Rycroft, KPMG LLP for the Appellant

Raymond Hill of counsel (instructed by the General Counsel and Solicitor to HM Revenue and Customs) for the Respondents

DECISION

Background

1. A dispute has arisen between local council authorities across the UK and the Respondents (“HMRC”) concerning the VAT liability of charges paid by members of the public for access to sports and leisure facilities provided by those authorities. HMRC contend that the charges should bear VAT at the standard rate; the local authorities disagree.

2. In case management of the appeals (of which there is a large number) it was directed that:

(1) Consideration may need to be given to the statutory provisions relating to local authorities in the constituent parts of the UK, which vary by jurisdiction.

(2) A single lead case (Tribunal Procedure Rule 5(3)(b) refers) should be identified for each of the three territorial jurisdictions: England & Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

(3) The nominated lead cases were the Appellant for England & Wales; Midlothian Council (TC/2011/7844) for Scotland; and Mid Ulster District Council (formerly Magherafelt District Council) (TC/2011/687 & TC/20102/9253) for Northern Ireland.

(4) The Tribunal panel to hear all three lead appeals would consist of three Judges, together qualified in the three jurisdictions. The then Chamber President confirmed the panel as constituted, and nominated Judge Kempster as the presiding member (Senior President’s Practice Statement of 10 March 2009, paras 7 & 8, refers).

(5) For administrative reasons, the appeal of Mid Ulster District Council would be heard first, followed by a hearing of the other two lead cases together. The Tribunal’s decisions on the three appeals would be released together.

Introduction

3. By a voluntary disclosure submitted in December 2010 the Appellant (“the Council”) (previously called Chelmsford Borough Council) claimed repayment of VAT allegedly overpaid in VAT accounting periods between 2006 and 2010, totalling around £0.9 million. [1] The claim was rejected by HMRC, and the Council appeals to the Tribunal.

4. In brief summary, the Council contends (and HMRC disputes) that the charges in dispute do not attract VAT on three alternative grounds:

(1) Its supplies of sporting and leisure activities to members of the public are not “economic activities”, and are therefore outside the scope of VAT;

(2) Its supplies of sporting and leisure activities to members of the public are provided by the Council in its role as a public authority acting under a special legal regime, and therefore it is not a taxable person in respect of those supplies; or

(3) Its supplies of sporting and leisure activities to members of the public are provided by the Council in its role as a public authority, and therefore it is not a taxable person in respect of those supplies, by virtue of Note 3 Group 10 sch 9 VAT Act 1994.

Legislative provisions

VAT Legislation

5. Article 2 Principal VAT Directive (2006/112/EC) (“PVD”), provides, so far as relevant:

“1. The following transactions shall be subject to VAT: …

(c) the supply of services for consideration within the territory of a Member State by a taxable person acting as such; …”

6. Article 9 PVD provides, so far as relevant:

“1. 'Taxable person' shall mean any person who, independently, carries out in any place any economic activity, whatever the purpose or results of that activity.

Any activity of producers, traders or persons supplying services, including mining and agricultural activities and activities of the professions, shall be regarded as 'economic activity'. The exploitation of tangible or intangible property for the purposes of obtaining income therefrom on a continuing basis shall in particular be regarded as an economic activity. …”

7. Article 13 PVD provides, so far as relevant:

“1. States, regional and local government authorities and other bodies governed by public law shall not be regarded as taxable persons in respect of the activities or transactions in which they engage as public authorities, even where they collect dues, fees, contributions or payments in connection with those activities or transactions.

However, when they engage in such activities or transactions, they shall be regarded as taxable persons in respect of those activities or transactions where their treatment as non-taxable persons would lead to significant distortions of competition. …

2. Member States may regard activities, exempt under Articles 132, …, engaged in by bodies governed by public law as activities in which those bodies engage as public authorities.”

8. Article 132 PVD provides, so far as relevant:

“Exemptions for certain activities in the public interest

1. Member States shall exempt the following transactions:

…

(m) the supply of certain services closely linked to sport or physical education by non-profit-making organisations to persons taking part in sport or physical education; …”

9. Article 133 PVD provides:

“ Member States may make the granting to bodies other than those governed by public law of each exemption provided for in points (b), (g), (h), (i), (l), (m) and (n) of Article 132(1) subject in each individual case to one or more of the following conditions:

(a) the bodies in question must not systematically aim to make a profit, and any surpluses nevertheless arising must not be distributed, but must be assigned to the continuance or improvement of the services supplied;

(b) those bodies must be managed and administered on an essentially voluntary basis by persons who have no direct or indirect interest, either themselves or through intermediaries, in the results of the activities concerned;

(c) those bodies must charge prices which are approved by the public authorities or which do not exceed such approved prices or, in respect of those services not subject to approval, prices lower than those charged for similar services by commercial enterprises subject to VAT;

(d) the exemptions must not be likely to cause distortion of competition to the disadvantage of commercial enterprises subject to VAT.

Member States which, pursuant to Annex E of Directive 77/388/ EEC, on 1 January 1989 applied VAT to the transactions referred to in Article 132(1)(m) and (n) may also apply the conditions provided for in point (d) of the first paragraph when the said supply of goods or services by bodies governed by public law is granted exemption.”

10. The relevant UK VAT legislation, which (save as below) does not need to be quoted here, is in ss 1, 4, 5(2), 24, 41A, and 42 VAT Act 1994 (“VATA”).

11. Section 33 VATA provides, so far as relevant:

“Refunds of VAT in certain cases.

(1) Subject to the following provisions of this section, where—

(a) VAT is chargeable on the supply of goods or services to a body to which this section applies, …, and

(b) the supply, … is not for the purpose of any business carried on by the body,

the Commissioners shall, on a claim made by the body at such time and in such form and manner as the Commissioners may determine, refund to it the amount of the VAT so chargeable.

(2) Where goods or services so supplied to … the body cannot be conveniently distinguished from goods or services supplied to … it for the purpose of a business carried on by it, the amount to be refunded under this section shall be such amount as remains after deducting from the whole of the VAT chargeable on any supply to … the body such proportion thereof as appears to the Commissioners to be attributable to the carrying on of the business; but where—

(a) the VAT so attributable is or includes VAT attributable, in accordance with regulations under section 26, to exempt supplies by the body, and

(b) the VAT attributable to the exempt supplies is in the opinion of the Commissioners an insignificant proportion of the VAT so chargeable,

they may include it in the VAT refunded under this section.

(3) The bodies to which this section applies are—

(a) a local authority …”

12. Group 10 sch 9 VATA provides, so far as relevant:

“Sport, sports competitions and physical education

Item No …

3 The supply by an eligible body to an individual of services closely linked with and essential to sport or physical education in which the individual is taking part.

NOTES

…

(2A) Subject to Notes (2C) and (3), in this Group “eligible body” means a non-profit making body …

…

(3) In Item 3 “an eligible body” does not include (a) a local authority; …”

Local Authority Legislation

13. Section 19 Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976 (“LGMPA”) provides, so far as relevant:

“Recreational facilities.

(1)A local authority may provide, inside or outside its area, such recreational facilities as it thinks fit and, without prejudice to the generality of the powers conferred by the preceding provisions of this subsection, those powers include in particular powers to provide—

(a)indoor facilities consisting of sports centres, swimming pools, skating rinks, tennis, squash and badminton courts, bowling centres, dance studios and riding schools;

(b)outdoor facilities consisting of pitches for team games, athletics grounds, swimming pools, tennis courts, cycle tracks, golf courses, bowling greens, riding schools, camp sites and facilities for gliding;

(c)facilities for boating and water ski-ing on inland and coastal waters and for fishing in such waters;

(d)premises for the use of clubs or societies having athletic, social or recreational objects;

(e)staff, including instructors, in connection with any such facilities or premises as are mentioned in the preceding paragraphs and in connection with any other recreational facilities provided by the authority;

(f)such facilities in connection with any other recreational facilities as the authority considers it appropriate to provide including, without prejudice to the generality of the preceding provisions of this paragraph, facilities by way of parking spaces and places at which food, drink and tobacco may be bought from the authority or another person;

and it is hereby declared that the powers conferred by this subsection to provide facilities include powers to provide buildings, equipment, supplies and assistance of any kind.

(2)A local authority may make any facilities provided by it in pursuance of the preceding subsection available for use by such persons as the authority thinks fit either without charge or on payment of such charges as the authority thinks fit.

(3)A local authority may contribute—

(a)by way of grant or loan towards the expenses incurred or to be incurred by any voluntary organisation in providing any recreational facilities which the authority has power to provide by virtue of subsection (1) of this section; and

(b)by way of grant towards the expenses incurred or to be incurred by any other local authority in providing such facilities;

and in this subsection “voluntary organisation” means any person carrying on or proposing to carry on an undertaking otherwise than for profit. …”

14. In relation to swimming facilities, s 221 Public Health Act 1936 provides, “A local authority may provide public baths and washhouses, either open or covered, and with or without drying grounds; or any of those conveniences.” Section 222(1) ibid provides “a local authority may make such charges for the use of, or for admission to, any baths, or washhouse under their management as they think fit.”

15. Section 3(1) Local Government Act 1999 mandates a general duty for best value: “A best value authority must make arrangements to secure continuous improvement in the way in which its functions are exercised, having regard to a combination of economy, efficiency and effectiveness.”

16. Section 111 Local Government Act 1972 states the subsidiary powers of local authorities thus:

“(1)Without prejudice to any powers exercisable apart from this section but subject to the provisions of this Act and any other enactment passed before or after this Act, a local authority shall have power to do any thing (whether or not involving the expenditure, borrowing or lending of money or the acquisition or disposal of any property or rights) which is calculated to facilitate, or is conducive or incidental to, the discharge of any of their functions.

…

(3)A local authority shall not by virtue of this section raise money, whether by means of rates, precepts or borrowing, or lend money except in accordance with the enactments relating to those matters respectively. …”

Case law authorities

17. The following cases were cited, and those referred to in this decision notice use the marked abbreviations:

Bromley LBC v GLC [1982] 1 All ER 129 (“Bromley”)

C-89/81 Staatssecretaris van Financiën v Hong-Kong Trade Development Council

C-102/86 Apple and Pear Development Council v Customs and Excise Commissioners [1998] STC 221

Joined cases C-231/87 and C-129/88 Ufficio Distrettuale delle Imposte Dirette di Fiorenzuola d’Arda v Comune di Carpaneto Piacentino and Ufficio Provinciale Imposta sul Valore Agtgiunto di Piacenza v Comune di Rivergara and others [1991] STC 205 (“Carpaneto No 1”)

C-4/89 Comune di Carpaneto Piacentino and others v Ufficio provincial imposta sul valore aggiunto di Piacenza [1990] ECR I-1869 (“Carpaneto No 2”)

Credit Suisse v Allerdale Borough Council [1996] 4 All ER 129 (“Credit Suisse”)

C-155/94 Wellcome Trust Ltd v Customs and Excise Commissioners [1996] STC 945 (“Wellcome Trust”)

C-230/94 Enkler v Finanzamt Homburg [1996] STC 1316

C-247/95 Finanzamt Augsburg-Stadt v Marktgemeinde Welden (“Marktgemeinde”)

Halki Shipping Corp v Sopex Oils Ltd [1998] 2 All ER 23

C-216/97 Gregg v Customs and Excise Commissioners [1999] STC 934

Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales v Customs and Excise Commissioners [1999] STC 398 (“ICAEW”)

C-446/98 Fazenda Pública v Câmara Municipal do Porto [2001] STC 560 (“Fazenda Pública”)

C-142/99 Floridienne SA v Belgium [2000] STC 1044 (“Floridienne”)

Edinburgh Leisure & others v CCE (2004) VAT Tribunal Decision 18784 (“Edinburgh Leisure”)

C-284/04 T-Mobile Austria GmbH and Others v Republic of Austria [2008] STC 184 (“T-Mobile”)

C-288/07 Revenue and Customs Commissioners v Isle of Wight Council and others [2008] STC 2964 (“Isle of Wight”)

C-554/07 Commission v Ireland [2009] ECR I-128 (“Ireland”)

C-246/08 Commission v Finland [2009] ECR I-10605 (“Finland”)

C-102/08 Finanzamt Düsseldorf-Süd v SALIX Grundstücks-Vermietungsgesellschaft mbH & Co. Objekt Offenbach KG (“SALIX”)

C-180/10 & C-181/10 Jarosław Słaby v Minister Finansów and Emilian Kuć and Halina Jeziorska-Kuć v Dyrektor Izby Skarbowej w Warszawie (“Słaby”)

CEC v Yarburgh Children’s Trust [2002] STC 207

C-378/02 Waterschap Zeeuws Vlaanderen v Staatssecretaris van Financiën

CEC v St Paul’s Community Project Limited [2005] STC 95 (“St Paul’s”)

C-255/02 Halifax plc & others v CEC [2006] STC 919

C-262/04 Meilicke & others v Finanzamt Bonn-Innenstadt

C-369/04 Hutchison 3G UK Ltd & others v CEC [2008] STC 218 (“Hutchison”)

C-408/06 Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft v Franz Götz (“Götz”)

Boyle v Secretary of State for Northern Ireland [2010] NICA 5

C-263/11 Ainārs Rēdlihs v Valsts ieņēmumu dienests (“Rēdlihs”)

Prudential Assurance Co Ltd & another v RCC [2014] STC 1236 (“Prudential”)

C-174/14 Saudaçor—Sociedade Gestora de Recursos e Equipamentos da Saúde dos Açores SA v Fazenda Pública [2016] STC 681 (“Saudaçor”)

C-263/15 Lajvér Meliorációs Nonprofit Kft v Nemzeti Adó- és Vámhivatal Dél-dunántúli Regionális Adó Foigazgatósága ECLI:EU:C:2016:392 (“Lajvér”)

R. (on the application of Durham Company Limited (trading as Max Recycle)) v Revenue and Customs Commissioners [2017] STC 264 (“Durham Company”)

HMRC v Longridge on the Thames [2016] STC 2362 (“Longridge”)

C-520/14 Gemeente Borsele v Staatssecretaris van Financien [2016] STC 1570 (“Gemeente Borsele”)

C-344/15 National Roads Authority v The Revenue Commissioners ECLI:EU:C:2017:28 (“NRA”)

C-633/15 London Borough of Ealing v Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs [2017] STC 1598 (“Ealing”)

Newey (trading as Ocean Finance) v RCC [2018] STC 1054

R. (on the application of Durham Company Limited (trading as Max Recycle)) v Revenue and Customs Commissioners [2018] UKUT 188 (TCC) (“Durham PTA”)

Wakefield College v HMRC [2018] STC 1170 (“Wakefield College”)

Pertemps Limited v HMRC [2018] SFTD 1410 (“Pertemps”)

RCC v Frank A Smart & Son Ltd [2019] STC 1549

Evidence

18. The Tribunal approved the taking of a transcription of the proceedings, with copies thereof made available to all parties and the Tribunal.

19. We had documentary evidence contained in three volumes, and two volumes of authorities.

20. We took oral evidence from the following witnesses for the Council:

(1) Mr Jonathan Lyons is the Council’s Leisure & Heritage Services Manager. He adopted and confirmed (with a minor amendment) a formal witness statement dated 16 September 2016.

(2) Mr Philip Reeves is the Council’s Principal Accountant. He adopted and confirmed a formal witness statement dated 15 September 2016; he updated certain facts and figures, which are mentioned in his evidence below as relevant.

21. Mr Lyons’s evidence included the following:

(1) He has been with the Council for 30 years in various roles in sports development and sports and leisure management. Prior to that he had at one time briefly worked in a privately operated health and fitness club. During the period covered by the appeals he was Sport and Recreation Manager, and is currently Leisure & Heritage Services Manager. He is responsible for the Council’s four leisure centres and the Community Sport & Wellbeing Team.

(2) The Council's designated area of responsibility has a population of around 174,000. The area extends beyond the city of Chelmsford, incorporating both rural areas, containing small villages and hamlets, and the town of South Woodham Ferrers which is 13 miles away from Chelmsford. North to south the area extends to around 22 miles.

(3) The main fee generating leisure activities provided by the Council are swimming, ice skating, tennis, squash, table-tennis, badminton, football, gym and exercise classes, athletics and children's soft play. The Council offers a range of paid-for activities for children during school holidays. The Council also provides pitches for hire in its parks and gardens for the playing of football, rugby, hockey, netball, cricket, tennis and bowls. The services are provided through the Council's four leisure centres at Riverside Ice & Leisure Centre (“Riverside”), South Woodham Ferrers Leisure Centre, Dovedale Sports Centre and Chelmsford Sport & Athletics Centre, and in the Council's parks, gardens and pavilions. Most people using swimming and fitness facilities were local residents; those using the ice rink came from a wider area.

(4) The services provided through the leisure centres are offered on a 'pay for play' basis, meaning the public can turn up, without having any prior membership, and pay for access to swimming, ice skating, tennis, squash, table tennis, badminton, football, gym and exercise classes, athletics and children's soft play for one session. The only exception to this is the gym where it is necessary to have undertaken an induction for which there is a fee. The price of some activities, such as swimming, varies between sites due to differences in the facilities on offer. The Council operates price concessions for groups such as the under-16s, the over-60s, those on benefits, students in full time education, persons registered as disabled, those on apprenticeships, and foster carers.

(5) From 1 April 2011 the Council introduced the 'Leisure Plus Card', to help ensure that participation in sport and the arts remains affordable to local people; the main benefit of a Leisure Plus Card is a discount of £1 on pay-per-play prices. The Council also operates membership schemes which give access to a range of the Council's facilities for a monthly subscription; this reduces the cost for regular customers of pay-per-play prices; the membership schemes encourage healthy lifestyles as members are encouraged to come as often as they like; the Council aims to encourage those on membership packages to use them fully; attendance is monitored and if attendance is low then the individual is contacted to encourage them to attend by offering a consultation or assistance.

(6) The Council provides the services in view of the social benefits brought by participation in sport and leisure activities. The participation by the local population is recognised as providing wider benefits in terms of health and wellbeing, education, reduction in crime and tackling social exclusion. All of the decisions made by the Council in relation to sport and leisure take into account these social benefits. The social objectives are reflected in the Corporate Plan, which is the Council's high level statement of intent which sets out the corporate priorities; the current Corporate Plan identifies six key objectives for the area and its residents including 'Promoting healthier and more active lives'. The objectives are also reflected in the Council's Community Plan "Chelmsford Tomorrow 2021" dated April 2008, which outlines how the Council will work with partner organisations to achieve its objectives; these included increasing adult participation in sport from a baseline of 21.1% to 24.1% by 2011 (as measured by Sport England); a figure of 26.8% was secured by 2011 which represented the highest increase in Essex.

(7) The social objectives are also reflected in the Council's strategy documents relating to leisure. During the relevant period the Council had two different strategies: "A Strategy for Sport & Recreation in Chelmsford 2006-2010" and "Be Moved - A Strategy for the future of Sports and Arts in the heart of Essex - Chelmsford 2012-2016". The 2006-2010 document identifies five key aims being to: (1) improve the physical, social and mental wellbeing of individuals and the community as a whole; (2) target those groups that participate the least; (3) promote social inclusion; (4) encourage lifelong learning; and (5) increase the percentage of the population actively benefiting from the Council's leisure facilities. The key decisions such as pricing and capital investment are made with a view to achieving the social objectives.

(8) Because the Council is directed to social objectives, it cannot measure its performance purely on a financial basis. The Council does not provide the services with a view to profit. A service operating at a significant loss can be identified as very successful if it is achieving its social objectives. It used to be that the Council had to justify its spending decisions in what were termed 'best value' reviews; those reviews would take into account the social value for providing the services. More recently the cuts in central government grants have acted as the spur to reducing costs; the challenge has been to reduce costs without impacting service levels.

(9) One of the key decisions the Council makes is setting its fees for the services. The fees are set at a level that will allow for participation in sport and leisure across the whole of the population. The level of participation is one of the key performance indicators the Council measures itself against, as the more people participate in sport and leisure, the more they and the area stand to gain. The number of customer sports visits is recognised as a key indicator of performance; according to a survey carried out in around 2013, Chelmsford had a 9% higher than average increase in adult participation in sport and exercise.

(10) Other providers provide activities of swimming, ice skating, tennis, squash, table tennis, badminton, football, gym and exercise classes, athletics and children's soft play:

(a)Swimming - Swimming is provided by for profit ("FP") and not-for-profit ("NFP") providers. The most common FP's are gyms and hotels. Gyms (eg Virgin Active in Chelmsford) tend not to provide access to swimming on a pay-per-play basis but only as part of a membership package. Hotels typically provide access to guests as part of their room charge and do not offer pay-per-play prices. Hotels may also provide membership packages to allow local residents to use the facilities - for example, Pontlands Park Hotel has a leisure centre known as Reflections within its grounds offering swimming and gym facilities; this offers various membership packages rather than operating a pay-per-play system for accessing the facilities; the facilities are marketed and run to provide an exclusive spa type feel for the customer. The swimming provided by FP's is not directed to social need; it is highly unlikely that a gym or hotel would provide swimming sessions for the disabled or provide free swimming to the over-60's. Gyms and hotels tend to operate shorter and shallower pools that are less expensive to run; for example, Virgin Gym offers a four lane 20 x 10 metres pool with a uniform depth of 1.2 metres and a smaller children's pool of 5 x 5 metres. At Riverside the Council offers a six lane 33 x 13 metres pool which ranges in depth from 0.9 metre to 3.3 metres, a 20 x 10 metres Learner Pool and a diving pit with 1 metre, 3 metres and 5 metres diving boards. The deeper pools are typical of local authority activities; the depth allows for the pools to be used for a range of activities including competitive swimming, diving, canoeing, scuba diving, aqua fitness classes and synchronised swimming. The Council also provided an outdoor pool up until September 2014 which was open four months of the year and attracted people who would not normally swim; outdoor pools are not commonly provided by FP operators. There are some FP operators who block book and use facilities to provide swimming and coaching - for example, AquaAcademy which is a swim school for children and adults operated by an FP out of facilities at three schools in Chelmsford. There are also NFP's providing regular swimming using block bookings - for example, Chelmsford Swimming Club ("CSC") operates on this basis out of Riverside; the Council sees organisations such as CSC as partner clubs providing access to a range of experienced coaches, many of whom are volunteers, who can help develop the sport and act as a bridge between amateur and professional levels of sport. The Council has worked with CSC to develop its programme of Swim Fit sessions which is aimed at those who wish to develop their swimming but do not wish to compete or to make a large commitment of their time. NFP swimming clubs can also operate out of other venues such as schools or colleges. Finally, there is another category of provider in the form of leisure trusts which are NFP providers independent from local authorities; a significant proportion of local authorities in England & Wales now provide leisure services to the local population through these trusts; one advantage over provision by a local authority is that the trust will be exempt from VAT and so will not have to charge VAT on its leisure services. Neighbouring local authorities use this model - eg Rochford District Council provides public leisure facilities in partnership with Fusion; the overall activity will remain loss-making and Fusion will effectively be funded by its partners by being granted use of the local authority's facilities to deliver the services at very low or nominal rates.

(b) Ice skating - Ice skating is provided by both FP and NFP providers. An example of an FP provider is Silver Blades, whose nearest centre is based in Gillingham; as Silver Blades is an FP it will apply VAT to its general access charges, but will not charge VAT on block bookings in line with the exemption referred to in HMRC guidance. An example of an NFP provider is Lee Valley Leisure Trust which operates an ice rink in Hertfordshire in participation with Lee Valley Regional Park Authority; as Lee Valley Leisure Trust is an NFP its supplies of ice skating will be exempt from VAT.

(c)Tennis, Squash and Badminton - There are some FP's such as racquet clubs and gyms offering racquet sports as part of the package of membership benefits. Some hotels will also offer racquet sports such as a tennis court and less commonly badminton or squash - for example, Down Hall Country House Hotel offers two outdoor tennis courts free of charge to its guests; it is not common for these to be provided on a pay-per-play basis. There are also a number of NFP sports clubs (eg Marconi Social Club, The Grove Tennis Club and Danbury Tennis Club) offering racquet sports; some of those will have their own facilities, otherwise they will block book facilities from the likes of schools. As those clubs are NFP’s their provision to members will be exempt from VAT. Previously there was also provision by NFP leisure trusts such as Fusion from a health and racquet sports club called Clearview Health and Racquets Club in Little Warley, Chelmsford; however this has since been taken over by an FP provider, Virgin Active.

(d) Football - There are a number of FP providers of football pitches typically directed towards the playing of five-a-side football in the local area - eg Futuresoccer, Leisure Leagues and Power Play (Power Play uses school facilities). Again, the FP providers will provide block bookings on a VAT exempt basis in accordance with HMRC guidance, while individual bookings will be standard rated for VAT. There are no known FP providers of eleven-a-side football pitches though those facilities will be available for hire through NFP organisations such as schools or small community football clubs. There is also provision by NFP leisure trusts such as Fusion, which identifies that five-a-side pitch hire is provided in Rochford at Clements Hall Leisure Centre.

(e)Gym and exercise classes - There are a number of FP gyms operating in the local area - eg Nuffield Health. A gym will typically contain running machines and the like directed to cardio-vascular fitness and weights directed toward strength. Private gyms do not generally offer access on a pay-per-play basis. Increasingly, particularly during the last five years, low-cost gyms have been starting up which offer membership for around £15 per month - eg The Gym Group; those gyms differ in having much lower staff levels than the high end gyms like Virgin. There are very few NFP providers offering gym facilities; there is a gym provided at Anglia Ruskin University which is largely aimed at students but is available to both students and the public; the University is an NFP organisation and membership subscriptions should be exempt from VAT. There is also provision by NFP leisure trusts such as Fusion in both Braintree and Southend which provide gym facilities at Braintree Sport and Health Club and Southend Leisure and Tennis Centre.

(f) Athletics - There are no FP providers of athletics facilities operating independently of local authorities. There are other NFP providers such as NFP leisure trusts and also providers such as Chelmsford Athletics Club which uses the Council's facilities at the Chelmsford Sports and Athletics Centre.

(g) Children's soft play - There are a number of FP providers of soft-play which can be accessed on a pay-per play basis - eg Mayce Playce Soft Play Centre. NFP providers in the form of leisure trusts like Fusion will also provide soft play - eg Edmonton Leisure Centre in Enfield.

(11) The Council does not act as a business would because it does not aim to make a profit in its provision of leisure services. The Council is interested in financial performance and so its net expenditure, but that is to be weighed against social benefits achieved from participation in sport. The Council, year on year, will incur substantial net expenditure in respect of its provision of leisure services; this ranged from funding of £4,924,820 in 2006-07 to £2,501,000 in 2013-14. The Council cannot provide leisure services as a trading activity as it does not have power to do so - a local authority can only undertake a trade through a subsidiary company.

(12) In some instances the social benefit of providing a particular service will be assessed as being so high that the services will be provided free of charge or for nominal fees. The weekly block booking of the swimming pool and the Athletics Centre is provided for free for use by the disabled swimming and athletics clubs. The Council also provides a scheme for free swimming to the over-60's between 6:30am and 2pm Monday to Friday although participants have to pay a £10 annual administration charge. The Council provides a free programme of guided walks branded as 'Heart and Sole' and free two hour multi-activity play sessions for children during school holidays. Free access is a way of reaching out to vulnerable groups, or a way of increasing participation in under-represented parts of the community. Many activities are also provided at low rates - for example the Council provides a range of activities on a Sunday night aimed at 12 to 18 year olds which cost £1 to attend; these low rates are justified in view of specific social objectives such as the reduction of crime; this particular scheme is funded through a grant provided by Essex County Council. The Council also provides a range of leisure facilities to the public on an open access basis - so members of the public are free to use the tennis courts, outdoor gyms, BMX track, skate parks and basketball courts in the Council's parks and gardens.

(13) The Council does not expect a market return on its capital funding of leisure services. Capital funding is considered by reference to a range of different factors including the availability of grant funding from outside bodies, the public demand for a specific site and social benefit. Some of the Council's previous capital projects have benefitted from substantial funding from Sport England. The Sports and Athletics Centre received grant funding of approximately £2,200,000, whilst the South Woodham Ferrers swimming pool received a grant of approximately £2,300,000. The Athletics centre attracted funding partly because of its location in a deprived ward; the Council recognises that siting a leisure centre in an area of deprivation is likely to bring higher social benefits. The Council will fund capital projects in areas where public demand is not met by private operators - eg swimming in South Woodham Ferrers.

(14) The Community Sport & Wellbeing Team is made up of around six officers who are responsible for promoting and developing the Council's leisure services. Their remit is, amongst other things, to advise and support local sports clubs and coaches, work with schools and implement schemes aimed at promoting health or increasing participation amongst vulnerable groups. The Council runs its leisure department in a way which actively promotes other organisations.

(15) Leisure services are provided by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department under authority delegated from the Council. Mr Lyons manages affairs on a day to day basis. Any price rises for leisure services in excess of inflation have to be considered and approved by the Council. The Council maintains a level of oversight through the Overview and Scrutiny Committee.

(16) The Council also has regard in providing the services to statutory obligations. The 'best value' reviews were undertaken to ensure the Council was meeting its statutory obligations. The Council must also now have regard to obligations arising under the Health and Social Care Act 2012, which established health and wellbeing boards to take on the statutory function of public health from the government with effect from April 2013; the Council is part of the Essex County Council Health and Wellbeing Board Structure. The Council recognises that the promotion of health is one of the key benefits to be derived from participation in sport and leisure pursuits; as well as the general effects of such participation the Council has specific initiatives such as a GP exercise referral scheme, and the Bodycare programme aimed at children and teenagers, which are focused on improving the health and wellbeing of the population.

(17) If VAT were not to be charged on the services then it would not lead to any differences in prices charged, which are set at a level designed to increase participation. VAT is not generally identified as a separate item to customers save in relation to the hire of sports pitches (where the VAT is passed back as it is considered fair to community sports organisations such as sports clubs as the Council benefits from their commitment to a longer booking). The approach would be different if all prices were to be exempt. Any VAT saving arising from these claims would be used by the Council to make up deficits in other areas. It is not a case of the Council taking the saving away from Leisure and Heritage Services; the department will not keep any surplus on the account at the end of the year. Mr Lyons did not believe there is any correlation in the industry between VAT and the price charged; NFP organisations like Fusion already provide services on an exempt basis, but the prices charged by Fusion are comparable to those of the Council.

(18) In recent years the Council has been subject to cuts in the grants received from central government. That has put pressure on budgets including the budget for sport and leisure facilities. The Council has not sought to reduce the budget by increasing prices but by finding schemes to bring about savings in costs. Despite the reduction in costs the core prices have remained largely unchanged save for the standard inflationary increases.

(19) If a resident tried the Council facilities but then joined another provider then Mr Lyons regarded that as a success - it was another person taking up sport because of the Council.

(20) In reply to questions in cross-examination:

(a)During the periods under appeal the Council’s net expenditure on sports and leisure facilities was in the region of £4.4 million to £9.9 million, before central government support. In 2005-06 expenditure on sports and leisure facilities was £9.97 million with income of £5.53 million (of which £3.25 million was fees and charges).

(b) Sports and leisure was one of the major operational functions of the Council.

(c)The “Be Moved” 2012-2016 strategy document stated that the sports and leisure facilities (being the four leisure centres plus community activities such as healthy walks and children’s play schemes) received 1.3 million visits per annum. A similar number of visits was reported for 2015-16; Riverside would account for the largest share of these (around 0.75 million). The total borough population was about 175,000, including about 110,000 in the City itself and about 20,000 in South Woodham Ferrers. That was proof of engagement with the community, in that there were over 8.000 visits per thousand of population.

(d) In setting charges for swimming and ice skating consideration was taken of peak and off-peak sessions; for exercise classes and badminton, longer sessions cost more; canoeing was more expensive than swimming, and ice discos more expensive than ordinary skating; higher quality facilities cost more (eg the 3G pitches at Riverside). There were additional charges for skate hire, racket hire etc. A slight discount was offered for booking a series of sessions. The charges took into account the customer’s perception of value but not the cost of provision - for example, swimming was more expensive to provide than squash, but court charges were greater than pool charges; also the crèche was costly to provide but the charge was cheap.

(e)There was always a balancing exercise between cost of provision and charges made. In Mr Lyons’s 30 years with the Council the overriding factor had always been to encourage participation; charges would be held if it was felt that an increase would deter participation; in recent years, increases had been only inflationary.

(f) On memberships, people would choose based on the activity and frequency of attendance; membership included a Leisure Plus Card, which reduced the cost of pay-per-play sessions; full membership involved no extra fees for the activities covered by the membership. Most users were pay-per-play. It was correct that private providers such as Virgin Active offered membership packages.

(g) On concessions, there was no formal means-testing; instead they were by reference to targeted categories, eg over-60s, or GP referrals; this was common practice for local authority service provision.

(h) Facilities which were provided free of charge were the adiZone basketball court (but a full size court would be paid for); BMX; unbooked tennis courts; health-walking; and skateboarding. Parks facilities were under a separate budget. Over-60s swimming was promoted as free but it required a Leisure Card and payment of an administration fee (about £10); it was very good value and attracted around 2,500 visits each month from around 1,000 users.

(i) The Council offers a range of discounts, for example, to those referred from the NHS or talented young sports people called sports ambassadors.

(j) Marketing of the facilities was important to establish what users wanted, and to reach groups who do not usually attend. It was important to encourage people to come in the first place, and then attend more often; that got more people exercising and encouraged a healthy lifestyle.

(k) For children’s parties, the Council’s facilities offered a different experience - eg trampoline parties. These represented only a tiny fraction of total income, and were only held at times when facilities were underused. It was also another way of getting people through the doors to participate.

(l) It was correct that there was an overlap with other providers (both FP and NFP) for some services. Although the charges of such providers might appear similar to those of the Council, the facilities were often very different (eg staffing and equipment). It was a matter of customer choice. The Council prioritised pay-per-play, while other providers insisted on memberships. The Council aimed to provide something for everyone, and ensure that customers knew that they would be looked after.

(m) People not using the Council’s facilities might look to Rochford (which uses Fusion, an NFP leisure trust), or Maldon (a private operator). For tennis there were a number of clubs with varying facilities (eg floodlighting); tennis players tended to go where their friends went.

22. Mr Reeves’s evidence included the following:

(1) He has over 20 years’ experience of local government finance, including 13 years with the Council, and is currently the Council’s Principal Accountant. He is responsible for producing the Council 's budget reports and medium term financial strategy.

(2) At the start of the relevant period the executive functions of the Council were arranged into nine directorates each reporting to the Chief Executive. The relevant services were provided through the directorate for Leisure and Cultural Services; that directorate was principally responsible for leisure centres but also for theatres, museums, special events and arts development.

(3) Every year the Council prepares a budget in advance of the financial year. The budget must be approved by the Council's highest decision making body which is a full Council meeting of all 57 elected members. The Council is required by law to set a balanced budget. The Chief Finance Officer has a duty to make a report to the Council if the budget has illegal expenditure or is unbalanced. The Council is not allowed to borrow to finance revenue expenditure; borrowing is only permitted for capital expenditure.

(4) The budget identifies the net amount of revenue expenditure that needs to be financed after taking account of any use of balances; that net budget requirement is then funded in part from the formula grant from central government (around half); the remainder is funded through Council Tax. The budget is broken down by reference to each directorate, including Leisure and Cultural Services. Revisions are made to the budgets during the course of the year. The Leisure and Cultural Services budget is broken down by reference to sites, such as the leisure centres, and also in some cases by reference to activities such as “Arts Development”. Estimated expenditure is identified against each of the leisure centres.

(5) The actual expenditure for Leisure and Cultural Services is substantial and is significant in the overall finances of the Council; for 2004/05 it was £4.94 million. In the same year the Operational Services directorate incurred similar expenditure (£4.92 million), and the only directorate with higher expenditure was Strategic Housing and Environmental Services (£5.83 million).

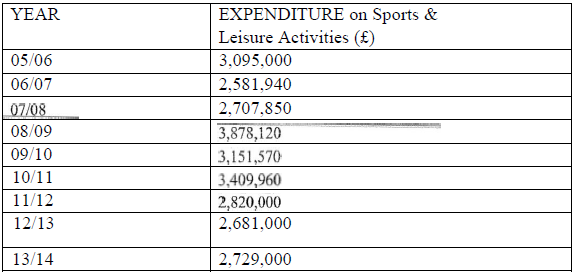

(6) A summary of the actual expenditure on sports and leisure across the period is:

(7) In 2007/08 responsibility for museums, accounting for around £750,000 of the budget, was taken out of the Leisure and Cultural Services directorate.

(8) The funding requirement of the Council is identified in terms of it representing “expenditure” and not as a “loss”. The reason the Council is willing to expend money from the budget to fund these services is because the Council recognises that expenditure on leisure services achieves its objectives in terms of wider social benefits; these include health and wellbeing, inclusion, equality and education. The fact that the Council has to pay for the services, after taking into account fees and charges, is not viewed in negative terms.

(9) The Council financially appraises any new leisure services (eg Melbourne Park Athletics Centre) but it will not require a surplus of income over expenditure as a condition for undertaking a new activity. All services are provided within the context of the responsibility the Council has for dealing with public funds and therefore the Council minimises expenditure by maximising the financial position of the provision of any services to the extent that does not conflict with the Council's other objectives. Where the two are in conflict then financial considerations are generally recognised as secondary; for example, the Council would not agree to increase fees to reduce expenditure on a service if the result of that increase was expected to exclude vulnerable groups from accessing the services.

(10) Where the cost of providing particular services changes to any material degree then it is for the Council to decide how to address those changes. The Council can decide to reduce/increase Council tax, to cut/increase the existing services, or to increase/reduce fees. The Council is not restricted in making these decisions to use money saved in Leisure and Cultural Services in that Directorate; it can notionally use money saved in one area in any way it considers appropriate. The same cannot be said of all savings; in some cases fees, such as those for Building Control, are linked to the costs; if savings were achieved in those areas the Council would have to either reinvest those savings to provide enhanced services or reduce the fees for those services.

(11) During the period covered by these appeals the Council has been subject to substantial reductions in the support from central government and the consequent need to make savings efficiencies, spend-to-save schemes and additional income so as to keep any overspend to a minimum. The reduction in funding from central Government has been significant: whilst in 2005/6 the Council received £8.53 million in grant from central Government, in 2014/15 that had reduced to £6.44 million. If any saving had arisen in those years then it would have been used by the Council to support its existing expenditure in other areas; the Council would not use any savings from reduced costs in providing the services to fund a reduction of the fees.

(12) The capital scheme for Leisure and Cultural Services is stated in an annual capital budget, which identifies items of planned capital expenditure and any ongoing capital expenditure projects. For example:

(a)In 2005-06 there was significant planned capital expenditure of £1.3 million in relation to Phase 4 of the Melbourne Park Athletics Centre; also Phase 2 of the Melbourne Indoor Athletics Centre and South Woodham Ferrers Swimming Pool.

(b) In 2009 a capital scheme commenced for the undertaking of essential repairs to Riverside which was budgeted for £1.44 million.

(c)In 2010 an improvement programme commenced for Riverside which was budgeted to cost £1.57 million.

(d) In 2011 a capital scheme was set up for track resurfacing works at the athletics centre budgeted for £102,000.

(e)In 2012 capital schemes were introduced for the athletics centre for replacement equipment (£100,000) and replacement plant (£98,000). Capital schemes were introduced for Riverside comprising replacement of equipment (£225,000), plant replacement (£490,000) and a combined heat and power system (£200,000). Capital schemes were introduced for South Woodham Ferrers comprising replacement of equipment (£100,000), replacement of the all-weather pitch (£150,000) and plant replacement (£196,000).

(13) New capital expenditure must be justified against the Council's stated Corporate Values. These corporate values reflect the social objectives sought to be achieved by the Council in providing leisure services; financial issues, such as the need to minimise costs, rank as secondary considerations. For example, in the 2005/06 budget the capital spend for the South Woodham Ferrers swimming pool is identified as corresponding with the values of "Working in partnership", "Delivering quality services which meet local needs" and "Enhancing healthy living". There is no expectation by the Council of a return on the capital expenditure on leisure centres. The financial appraisal of projects is with a view to minimising costs, at least where that can be achieved without compromising the objective of providing the services.

(14) In the private sector it would be typical to produce and analyse costs and expenditure by reference to particular activities; also, to identify the capital expenditure and to assess the return on capital as part of financial monitoring. The Council operates differently from the private sector as it does not allocate costs to activities but operates on a broader level, aggregating costs to locations. Such private sector information is not of significant value to the Council's management as profit on an activity is not an objective. The Council does not require a positive return on capital invested whilst a private sector business will only undertake the investment if it produces a positive return on capital. For example, the Council is currently developing proposals to spend £40 million on a replacement swimming pool complex; there are many requirements for the scheme but none are that it should produce a return on capital; the Council expects to minimise the cost of leisure services but not to profit from them.

(15) A significant proportion of local authorities now provide their sport and leisure services through sport and leisure trusts or private providers. The trusts are charitable organisations and so their provision of sport and leisure services are exempt from VAT. Local authorities such as the Council will consider from time to time alternative structures for providing leisure services and, in particular, the provision through a trust. In 2015 Sport England published "Leisure Management Delivery Options Guidance", which refers to the various delivery options available to local authorities as being in-house management, outsourcing to an existing trust or private contractor, establishing a new trust, mutual or other form of social enterprise, transfer of assets, or establishing a new joint venture. One of the disadvantages of outsourcing to an existing leisure trust, as stated in that document, is that "The Local Authority loses direct control of services and manages through a lease and contract" but it "retains ultimate liability for the operational performance and capital liabilities of the services".

(16) The Council constantly strives to deliver savings. In this respect the Council has obligations in relation to the spending of public money and is required to reduce costs if that can be achieved without compromising services. The Council has previously reviewed its own leisure services and considered externalising them. In the course of that assessment the Council considered the potential savings that could be delivered. The main reason for retaining the services was that the Council would lose control by externalising them which could impact the Council's ability to meet its objectives.

(17) If, during the course of a year, VAT ceased to be due on leisure services, or a substantial repayment was made in that respect, then it would give rise to an expectation of a surplus on the budget. That would in turn cause the Council to revise the budgeted expenditure for Sport and Leisure downwards. The difference may be used first to offset any unplanned expenditure of the Council. Any unused surplus is carried into the general pool of funding for the next year. In no circumstances would the repayment be carried forward for use by the Sport and Cultural Services directorate.

(18) In reply to questions in cross-examination:

(b) While it was difficult to give an accurate figure for the percentage of costs covered by fees charged (because that was not how the Council analysed matters), an estimate of one third was reasonable.

(c)While no figures were available (again, because that was not how the Council analysed matters), it was reasonable to say that the full costs of a major facility were unlikely to be recouped over its lifetime.

Appellant’s case

23. For the Council, Ms Brown and Mr Rycroft submitted as follows.

Background

The Ealing case and exemption

24. In Ealing the CJEU held that sports and leisure activities provided by a local authority fall within the scope of the exemption in art 132(1)(m) PVD which relates to “the supply of certain services closely linked to sport or physical education by non-profit making organisations to persons taking part in sport or physical education”. The question of whether those supplies are or otherwise should be treated as non-taxable activities is antecedent to that of exemption which can only apply to supplies falling within the scope of VAT. The terms of arts 9 and 13 were not considered by the Court in Ealing in which the referral was on the basis that neither party claimed that the local authority taxpayer was acting as a public authority.

25. The Council continues to plead its case by reference to arts 9 and 13 rather than relying on the exemption afforded by art 132. That is because different consequences may flow for some local authorities due to the application of purely national law provisions in s 33 VATA 1994 which may, depending on the circumstances, place a local authority relying on exemption in a disadvantaged position, as compared to if the same services were to be treated as non-taxable. The Council has previously operated on the basis that VAT incurred by it and relating to its exempt supplies was insignificant. HMRC’s guidance (in Notice 749) is that VAT attributable to exempt activities is insignificant only if it amounts to less than one of (a) £7,500 per annum; or (b) 5% of the total VAT incurred on all purchases in any one year. If the Council were to rely on the direct effect of art 132(1)(m) to treat the disputed supplies as exempt, then the VAT relating to them will cease to be insignificant, giving rise to a requirement for the Council to restrict the VAT recovered relating both to its pre-existing exempt supplies and the relevant supplies. The Council has concluded that if it were to rely on art 132(1)(m) then its claim would be extinguished, as the restriction on recoverable VAT would then exceed the VAT declared on the leisure supplies. However, the Council reserved the right to rely on art 132(1)(m) if it lost the current appeal.

Local Government provisions

26. The Council operates under the ‘two-tier’ system of local government in which other legal powers and responsibilities, in particular those relating to education and health and social care, are held by Essex County Council.

27. The Council, as a local authority, is a statutory body whose objects and powers are as prescribed by Parliament (either expressly or impliedly). A local authority is empowered to provide public leisure services in England & Wales by virtue of s 19(1) LGMPA: “a local authority may provide, inside or outside its area, such recreational facilities as it thinks fit”. Under s 19(2) LGMPA a local authority may make those facilities available for use “by such persons as the authority thinks fit either without charge or on payment of such charges as the authority thinks fit”. Furthermore, under s 19(3) LGMPA a local authority may contribute “by way of grant or loan towards the expenses incurred or to be incurred by any voluntary organisation in providing any recreational facilities which the authority has power to provide by virtue of s 19(1)”.

28. S19(1) LGMPA overlaps, so far as public swimming is concerned, with the earlier s 221 of the Public Health Act 1936 under which a local authority may provide “(a) public baths and washhouses, either open or covered, and with or without drying grounds”. Section 222 PHA 1936 also provides that a “local authority may make such charges for the use of, or for admission to, any baths or washhouse under their management as they think fit”.

29. The Council is required to make discretionary decisions concerning the range of activities and charges with regard to the wider benefit of those activities to the population in the area of the Council’s responsibility. The wider legal obligations of the Council are in s 3 Local Government Act 1999, which requires the Council to “make arrangements to secure continuous improvement in the way in which its functions are exercised, having regard to a combination of economy, efficiency and effectiveness”. Also relevant are the Council’s obligations as regards state aid arising from art 107 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the Economic Union which outlaws state aid which is incompatible with the internal market. Whilst state aid is generally outlawed, art 107(2)(a) expressly recognises “aid having a social character, granted to individual consumers, provided that such aid is granted without discrimination related to the origin of the products concerned” as being compatible.

The Council’s activities

30. The witness evidence described how the Council has exercised its discretion to provide fee-generating sport and leisure activities, and the Council’s objectives in providing leisure activities.

31. The Council’s objectives have not, at any time, included the objective of making a surplus on either the provision of the disputed supplies or of leisure activities more generally (the making of a surplus could be a consequence of pursuing the Council’s objectives but is not an aim in and of itself).

32. The Council provides some services for free or on an open access basis. The Council provides activities which are specifically targeted at improving health (the GP exercise referral scheme and the Bodycare programme).

33. The Council does not expect any return on capital expenditure - the capital expenditure is not recognised in the form of any charge to depreciation. The decision making as regards capital expenditure is by reference to the expected social benefits which may justify siting a leisure centre in an area of deprivation. The nature of the facilities provided is also driven by the Council’s objectives - facilities are provided with a view to allowing a wide range of uses. The nature of any investment is also made with regard to the needs of the local population.

34. The Council measures success in providing the leisure activities by reference to its objectives. The fact that the Council incurs net expenditure in respect of the disputed services and in connection with leisure activities more generally is not viewed in negative terms - the net expenditure is weighed against the social benefits achieved from participation in sport.

35. The fees for the disputed supplies are set at a level to allow participation across the whole of the population. The supplies are generally available on a pay-per-play basis without any prior need for membership. The Council’s services contrast with those provided elsewhere, in particular the private commercial sector, which commonly provides sports leisure activities as part of a membership package.

36. The disputed supplies, throughout the period at issue in this appeal, gave rise to significant net expenditure, which was in each year planned for in advance when the Council set its budget for the year. The net expenditure is funded in part from a formula grant from central Government but also through Council Tax.

37. The provision of leisure activities more generally by local authorities may be organised differently. In particular, the local authority may arrange their affairs such that their objectives are achieved through the means of a leisure trust. The leisure trust will typically be funded through a payment made by the local authority which, it is recognised, falls within the scope of VAT in light of the decision in Edinburgh Leisure. HMRC’s guidance to local authorities (in RCB 28/7) states: “any VAT charged to the local authority by a contractor acting as principal in respect of the management fee or deficit funding will be recoverable in full by the authority subject to the normal rules”. It is understood that by this HMRC accept that a local authority will not, in these circumstances, be recognised as acting in the course of a business in providing funding to third parties to discharge their leisure functions.

The issues for determination

38. The issues for determination by the Tribunal are whether in undertaking the activities the Council:

(1) is undertaking economic activity within the meaning of art 9(1); or

(2) is to be recognised as engaging in that activity as a public authority within the meaning of art 13(1), which it is agreed falls to be determined by the tests as laid out by the Court which requires that an assessment be made as to whether the activity is undertaken pursuant to a ‘special legal regime’; or

(3) if the Council is not recognised as engaging as a public authority for the purpose of art 13(1), whether the terms of Note 3 to Group 10 VATA operates as an exercise of the discretion permitted under art 13(2) so as to treat the supplies made by the Council as carried out by it as a public authority.

Article 9 - No economic activity

39. The Council accepts that it is supplying “services for consideration” but not that it is “a taxable person” for the purposes of art 2. In those circumstances, the Council as a local authority has a right of refund under s 33 VAT Act 1994.

40. In referring to “any economic activity” art 9 is only intended to cover activities which essentially concern financial or monetary considerations. That is underlined by the terms of the second sub-paragraph which identifies that the “exploitation of tangible or intangible property for the purposes of obtaining income therefrom on a continuing basis shall in particular be regarded as economic activity”. Whilst that wording is linked to the exploitation of property, it has been recognised by the Court as applying to all of the activities referred to in art 9 - see Götz at [18].

41. In referring to “purpose” art 9 requires assessment of the underlying rationale for the activity as a whole determining whether it is undertaken for the purposes of obtaining income or for other purposes. Whilst it is necessary to seek to identify the reason for which the activity is being undertaken, the case law of the Court is clear in recognising that the activity has to be considered per se and without regard to its purpose or results - see for example Finland at [37].

42. The legislative purpose of art 9, as it applies to public authorities, is set out in the Opinion of the Advocate General (“AG”) in Gemeente Borsele. In general, there is no imperative to imposing VAT on services provided by the state as it operates only to reallocate revenue at a national level (between different departments of state) - Opinion at [23]. However, the very structure of arts 9 and 13 recognise that at least some activities of public authorities are considered, in principle, as capable of falling within the scope of VAT as economic activities - Opinion at [24]. There are two reasons for taxing those transactions: the first is to prevent distortions of competition within a relevant and identified market; and the second is to ensure, in accordance with the principle set out in the fifth recital to the PVD, that final consumption is effectively taxed such that if the state provides services culminating in final consumption then such consumption is taxed. The examination of whether a public activity constitutes an economic activity pursuant to art 9(1) “is subject to manifestly stricter criteria than would apply in the case of an activity carried on by a private individual” - Opinion at [27]. In the current appeal taxation of the Council’s supplies is not justified either on the grounds of distortion of competition or final consumption. There is no particular reason, with regard to the PVD, as to why treating leisure activities as not being economic activities should give rise to distortions in competition - the treatment of the activities as exempt or non-taxable gives rise to essentially the same results so far as concerns the PVD; that is reflected in the terms of art 13(2) which make it clear that Member States can treat exempt activities as non-taxable activities. Neither is there any imperative to capture and recognise the value of those activities as representing final consumption by the users of the facilities; activities which are in principle exempt from VAT at European level (as has been established in Ealing) are assimilated to acts of final consumption, exemption, non-economic activities and final consumption, all having the same chain breaking effect on recovery of VAT paid on supplies received.

43. Wakefield College concerned the correct VAT characterisation of further education courses provided to students paying fixed fees representing only 30-35% of the costs of providing the courses. The courses were provided at below cost due to grant funding provided by the Learning and Skills Council. Those activities were considered against the wider factual background in which the college provided the same courses to some students, representing the majority, for no fee, and other courses where no remission was available and the fees were designed to cover the full costs (‘full cost courses’). The agreed position of the parties in that appeal, in respect of those other activities, was that the services provided for no consideration did not amount to the carrying on of a business, but the provision of ‘full cost courses’ did. The Court of Appeal identified (at [51] to [59]) the factors relevant to identifying whether the activities fall within the scope of art 9.

44. The concept of ‘market participation’ is in some respects an overarching test. In Gemeente Borsele (at [30]) the Court stated: “Comparing the circumstances in which the person concerned supplies the services in question with the circumstances in which that type of service is usually provided may therefore be one way of ascertaining whether the activity concerned is an economic activity”. The AG (Opinion at [65]) notes that the fact that only a small percentage of the costs are recovered is not typical conduct of a market participant. The relationship between income and expenditure was also considered relevant in Finland in which the Court considered whether VAT should be applied to payments made by individuals to the public legal aid office in return for the provision of representation. In Hutchison the Court (at [35 - 36]), considering whether the grant by the government of mobile telecommunications licences to private corporations, recognises that activity as essentially amounting to the grant to economic operators to access the market (as distinguished from actual participation in that market). That is also reflected in the judgment in ICAEW in which the House of Lords considered whether VAT should be applied to registration fees charged by the ICAEW as a ‘recognised professional body’ to its members in discharge of a statutory regulatory function; their Lordships recognised (at 402j to 405a) that the activity was not economic activity with regard in particular to the fact that it was essentially exercising powers of the state.

45. A precondition for determining whether an activity is an economic activity is the identification of the activity itself. In Gemeente Borsele the transport provider charged in full to parents whose children travelled less than 6km, for those travelling 6-20km parents paid a price equivalent to taking public transport for a distance of 6km, and over 20km the charge was set taking account of the parent’s income. As a result, two thirds of parents did not pay any contribution. The AG stated (Opinion at [71]), “… the requirement of market participation on the part of a public activity must in principle be assessed in relation to the activity as a whole and does not necessitate the analysis of each individual transaction”. The Court’s judgment proceeds on the basis that both activities fall to be assessed together - (at [33]): “[t]he contributions at issue in the main proceedings are not payable by each user and were paid by only a third of the users, with the result that they account for only 3% of the overall transport costs, the balance being financed by public funds”. A similar analysis was applied in Finland in which, in having accepted the relevance of the general income and expenditure relating to the activity, the Court considered that the activity falling to be assessed included both paid for and unpaid for activities. The activities being undertaken by the Council include both the activities which are provided in return for consideration and those which are provided without any charge; that approach is consistent with the approach of the Court in Borsele and Finland, where it was accepted that the same paid-for and unpaid-for activities should be considered as a whole.

46. In Wellcome the Court concluded that the activities in that case, which concerned the buying and selling of shares, did not amount to an ‘economic activity’. In coming to that conclusion the Court relied on the fact that the trust had no power to engage in trading activities and was also precluded from taking majority holdings in other companies. The approach of the Court in Wellcome was considered by Patten J in Yarburgh (at [22]-[23]) - whilst he accepts the submission on behalf of HMRC that the motive of the person supplying the services is not relevant, he also states ‘the exclusion of motive or purpose in that sense does not require, or in my judgment, allow the tribunal to disregard the observable terms and features of the transaction in question and the wider context in which it came to be carried out’. In Floridienne (at [28]) the Court held that an economic activity had to have a “commercial purpose, characterised by, in particular, a concern to maximise returns on capital investments”. That would appear to be a relevant factor on the facts of the present case in which capital investment is made by the Council with no expectation of return. A similar approach was taken by Evans-Lombe J in St Paul’s which considered whether a charity was in business in providing the activity of a day nursery which had been undertaken for social reasons to support disadvantaged children. In giving judgment in favour of the charity the judge (at [54]) identifies the factors which weighed heavily in his assessment including that the fees charged were significantly lower than those charged by commercial nurseries and pitched at levels designed only to cover the costs after grants and donations were taken into account.

47. In the current appeal, the Council’s provision of the activities does not represent market participation:

(1) The Council incurs substantial net expenditure in its provision of both the disputed supplies considered in isolation and in connection with the provision of leisure activities taken as a whole and that such expenditure is planned for in advance. A loss is not of itself sufficient to identify an activity as falling outside the scope of economic activity and thereby ‘non-taxable’; however, the fact that the loss is habitual and planned for with no expectation of any return provides a wider context indicating that the Council is not involved in market participation.

(2) There is an absence of any account of capital expenditure which goes to make up the facilities - that represents an approach which is at odds with market participation where capital outlay is made in anticipation of reward.

(3) The Council receives income in the form of grants such as those from Sport England. The existence of grants is indicative that the activities do not represent ‘market participation’ - grants do not represent the ordinary operation of a market;

(4) A substantial proportion of the activities are provided for free such as the facilities provided in the Council’s parks and gardens and free swimming provided to the over 60s. The existence of free leisure facilities serves, objectively, to demonstrate that the activity is not dependent upon the stimulus of income.

(5) The activities are provided in the context of the law as it applies to public authorities - whilst on the face of it a local authority has wide discretion as to what leisure facilities it provides and as to the charges to be made for those services that discretion must be exercised in view of the legitimate and stated objects. The activities cannot be pursued with the primary objective of making profit and as outlined in the evidence, the Council does not recognise surplus as being a measure of success. The Council has identified the legitimate objects it seeks to achieve through the provision of leisure services - those objects are directed towards social purposes such as the use of sport to improve the health and welfare of the population.

(6) As identified in the evidence, the manner of provision varies greatly with that available in the for-profit sector - the Council is providing leisure services in a manner which seeks to make provision which is not met by the market - capital expenditure is directed towards areas of relative deprivation which are not served by the market.

(7) The central facilities are configured in a manner to facilitate a range of different uses. The facilities are made available to a range of different organisations who operate as partners in achieving the Council’s objectives, in particular its objective in increasing participation in sport in the area. The fees are set with a view to ensuring that the facilities are accessible to the wider population and so set at an affordable level and allowing ‘pay-per-play’ access.

48. Where a local authority chooses to exercise its statutory powers through a third party, such as in Edinburgh Leisure, then it is clear that the activity undertaken is essentially ‘noneconomic’. That is consistent with HMRC’s view that such authorities are entitled to recover VAT on the associated third party supply. There is no reason, from the perspective of a local authority, why that activity should fall to be assessed any differently whether undertaken ‘in house’ or by a third party.

Article 13 - Public authority acting under a special legal regime

49. Article 13 PVD provides that local government bodies are not to be regarded as taxable persons in respect of the activities or transactions in which they engage as public authorities, even where they collect dues, fees, contributions or payments in connection those activities or transactions. Article 13 in referring to ‘activities’ is essentially referencing the ‘economic activity’ as referred to in art 9 and, in referring to ‘transactions’ is referencing the terms of art 2 relating to the identification of a supply.