Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

United Kingdom Competition Appeals Tribunal

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Competition Appeals Tribunal >> British Telecommunications Plc v Office Of Communications [2017] CAT 25 (10 November 2017 )

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/CAT/2017/25.html

Cite as: [2017] CAT 25

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral citation [2017] CAT 25

|

IN THE COMPETITION APPEAL TRIBUNAL |

Case No: 1260/3/3/16 |

|

Victoria House |

10 November 2017 |

Before:

Mr Justice Snowden

(Chairman)

Dr Clive Elphick

Professor John Cubbin

Sitting as a Tribunal in England and Wales

BETWEEN:

BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS PLC

Appellant

- v -

OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS

Respondent

- and -

VIRGIN MEDIA LIMITED

CP GROUP (TALKTALK TELECOM GROUP PLC, VODAFONE LIMITED, COLT TECHNOLOGY SERVICES AND HUTCHISON 3G UK LIMITED)

GAMMA TELECOM HOLDINGS LIMITED

CityFibre Infrastructure Holdings PLC

Interveners

Heard at Victoria House on 10-13 and 24-27 April, 4-5, 8-10, 17-18 and 24 May 2017

Judgment (Market Definition)

APPEARANCES

Mr Daniel Beard QC, Mr Robert Palmer, Ms Ligia Osepciu and Mr David Gregory (instructed by BT Legal) appeared on behalf of British Telecommunications plc.

Mr Josh Holmes QC, Mr Mark Vinall, Mr Tristan Jones and Mr Daniel Cashman appeared on behalf of the Office of Communications.

Ms Sarah Love and Mr Tim Johnston (instructed by Charles Russell Speechlys) appeared on behalf of Gamma Telecom Holdings Limited.

Mr Philip Woolfe (instructed by Towerhouse LLP) appeared on behalf of TalkTalk Telecom Group plc, Vodafone Limited, Colt Technology Services, Hutchison 3G UK Limited.

Ms Sarah Ford QC (instructed by Ashurst LLP) appeared on behalf of Virgin Media Limited.

Note: Excisions in this Judgment (marked “[…]["]”) relate to commercially confidential information: Schedule 4, paragraph 1 to the Enterprise Act 2002.

CONTENTS

(2) The market review process and the BCMR 2016. 8

(3) The scope of this judgment and our conclusions. 10

B........ Technical Background. 16

(2) Ethernet and WDM technology. 17

(3) Ethernet in the First Mile. 17

(4) BT's leased line products. 18

C........ The Legal Framework. 22

(1) The EU Common Regulatory Framework. 22

(a) Burden and standard of proof 29

(b) The role of the Tribunal 29

(d) Standard applicable in future appeals. 35

D........ Witnesses and Evidence. 36

(3) Remarks on the evidence in this appeal 47

E........ Outline of the Parties’ Contentions. 50

(2) Product market definition – outline. 50

(3) Geographic market definition – outline. 53

(4) The competitive core – outline. 61

F........ Product Market Definition. 63

(3) Issues 2 and 3: preliminary discussion. 74

(b) Roadmap of our analysis of issues 2 and 3. 86

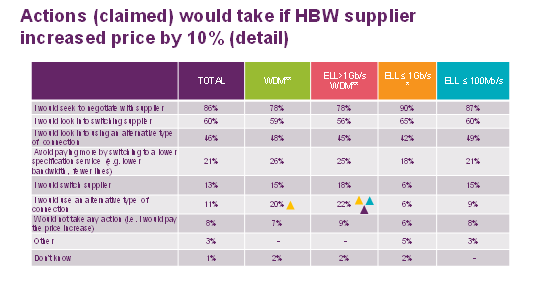

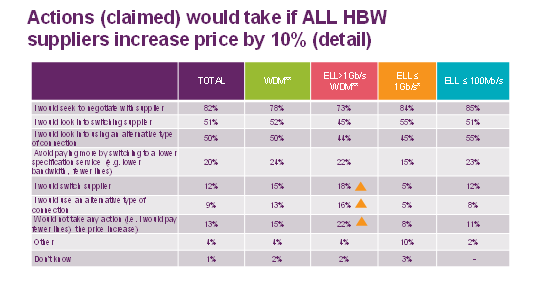

(6) Issues 2.5 and 3.5: Price sensitivity of users of leased lines, including BDRC survey 101

(a) Evidence regarding price sensitivity. 101

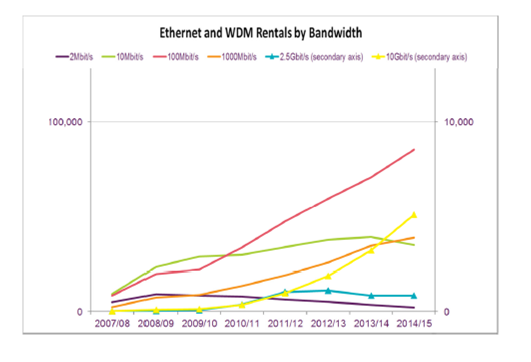

(7) Issue 2.3 and 3.3: the narrowing of price differentials. 107

(b) Evidence regarding a CP’s pricing of its WDM products. 111

(8) Evidence indicating significant numbers of 1G users with ~2G of demand 113

(a) Evidence before Ofcom when it prepared the FS. 113

(b) Evidence in the appeal proceedings. 114

(10) Issues 2.4 and 3.4: switching costs. 119

(b) Comments regarding the 10G SSNIP.. 128

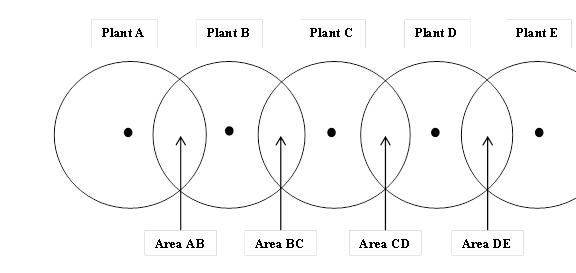

(13) Other matters: did Ofcom err in assessing the chain of substitution in the CISBO market? 133

(a) Chains of substitution. 133

(b) Did Ofcom err by failing to test all links in the chain?. 136

(c) Did Ofcom err by not checking pricing interactions at the extremes of the chain? 139

(14) Conclusion on product market definition. 142

G....... Geographic Market Definition. 143

(1) What is the purpose of defining geographic markets?. 143

(2) Ofcom’s approach to geographic market definition. 146

(4) The competitive conditions in the CBDs and the RoUK.. 147

(a) Ofcom’s identification of the CBDs in the May 2015 BCMR Consultation 147

(b) The decision by Ofcom not to define the CBDs as a separate market 148

(5) Issues 6 and 7: the formulation and application of the Boundary Test and Network Reach Test 167

(6) Conclusion on geographic market definition. 178

H........ Competitive Core. 179

(1) Issue 8: Introduction. 179

(1) Summary of the Tribunal’s findings. 188

(a) Product Market: Issues 1 to 3. 188

(b) Geographic Market Definition – Issues 6 and 7. 191

(c) Competitive Core – Issue 8. 193

FIGURES

Figure 1: Fibre optic cables. 16

Figure 2: BDRC Survey QSSNIP1 (Survey Figure 41) 104

Figure 3: BDRC Survey QSSNIP3 (Survey Figure 43) 105

Figure 4: Growth of Ethernet and WDM services (FS Fig 3.10) 117

Figure 5: Diagram of a chain of substitution. 134

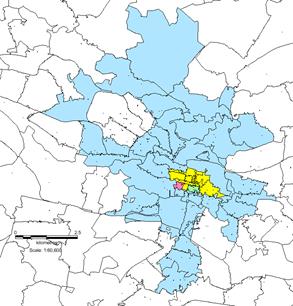

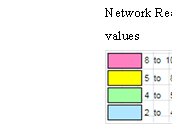

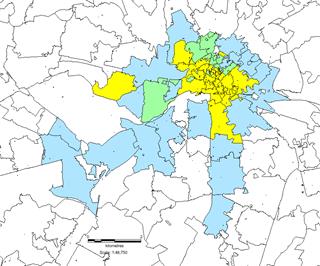

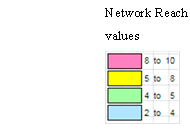

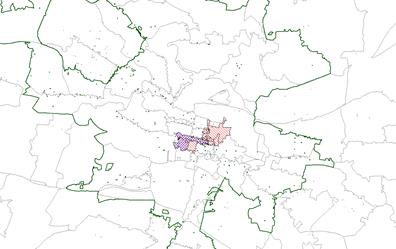

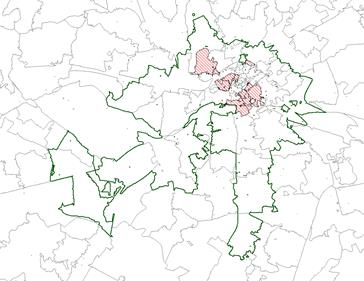

Figure 6: Network Reach values for Glasgow (FS Fig A10.50) 148

Figure 7: Network Reach values for Manchester (FS Fig A10.52) 148

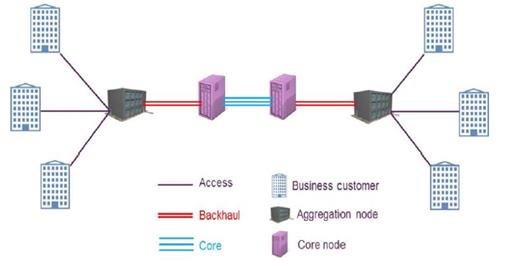

Figure 10: Illustrative example of network segments. 179

Tables

Table 2:.. Critical Loss Values for 10% SSNIP.. 71

Table 3: . TCO for new customers, 1G SSNIP.. 108

Table 4: . TCO for existing 1G customers, 1G SSNIP.. 109

Table 5: . TCO for new customers, 10G SSNIP.. 109

Table 6: . TCO for existing customers, 10G SSNIP.. 110

Table 7: . Ofcom’s overview of relevant metrics (based on FS Table 4.4) 153

ANNEXES

Annex 1: List of issues

Annex 2: Abbreviations used in this judgment

A. Overview

(1) Introduction

1. This case concerns the regulation of leased lines. These are high quality fixed connections allowing the transmission of large volumes of data between sites. They are supplied wholesale by communications providers (“CPs”) with the necessary fixed network infrastructure. They are used to supply data connections to businesses,[1] as well as fixed and mobile broadband services to consumers.

(2) The market review process and the BCMR 2016

5. The review is a forward-looking exercise, which seeks to determine the competitive position over the three year period until the next review. It consists of three stages.[2] NRAs must: (1) define relevant markets appropriate to national circumstances; (2) assess whether there is a lack of effective competition by reason of one or more CPs with significant market power (“SMP”); and (3) if so, impose regulatory obligations on the CP(s) with SMP to protect end-users and the process of competition. In defining the relevant market, NRAs must take utmost account of guidance from the European Commission (“Commission”), including its Recommendation on relevant markets (the “Recommendation”)[3] and the accompanying explanatory note (the “Explanatory Note”).[4]

6. The regulatory scheme envisages that as markets develop, mature and become more competitive, regulation will only be maintained or imposed where it is demonstrated to be necessary. The regulatory scheme has moved away from a scheme whereby regulation was imposed to “open up” markets held by former monopoly incumbents, to one where regulation will only be imposed if it can be shown that a market participant holds SMP. The general expectation is that over time the direction of travel will therefore be towards deregulation as existing regulation becomes unnecessary in the light of increasing competition.

8. In the BCMR 2013 Ofcom defined two separate product markets for “contemporary interface symmetric broadband origination” (“CISBO”) services. These were a market for business connectivity for lower bandwidth (i.e. up to and including one gigabit per second, or ≤1G) CISBO services, and, separately, a market for business connectivity for very high bandwidth (“VHB”) CISBO services (i.e. over one gigabit per second, or >1G services). Ofcom also found that each product market consisted of two geographic markets, one area known as the Western, Eastern and Central London Area (“WECLA”) and the second known as the Rest of the UK (“RoUK”)[5]. Ofcom concluded that, of those four markets, BT had SMP in all of them except the WECLA VHB market.

11. In terms of impact of the numbers of circuits subject to regulation, the changes brought about by the BCMR 2016 would result in:

(1) around 30,597 lower bandwidth circuits situated in the CLA being removed from SMP regulation; and

(2) around 762 VHB circuits situated in the LP falling within the scope of SMP regulation for the first time.

12. The BCMR 2016 would therefore lead to an overall reduction in total numbers of circuits subject to SMP regulation, which is consistent with the general trend of telecoms markets towards deregulation. Nevertheless, with regards to VHB services, there has been a shift against this general trend towards increased regulation which affects a small but significant number of VHB circuits in the LP.

(3) The scope of this judgment and our conclusions

13. BT lodged its appeal on 29 June 2016. It comprises six grounds of appeal. In broad terms:

(1) BT contended that Ofcom wrongly defined the relevant product and geographic market (Grounds D1 and D2).

(2) BT contended that Ofcom wrongly defined the extent of the “core conveyance network” (Ground D3).

(3) BT contended that Ofcom erred in imposing a DFA remedy. It contended that no remedy should have been imposed (Grounds E1 to E3).

14. Separately, two other companies lodged appeals concerning the FS.

(1) TalkTalk, one of the CPs intervening in support of Ofcom in BT’s appeal, lodged an appeal on 28 June 2016 arguing that the design of the DFA remedy was flawed. In very broad terms it argued that the price set by Ofcom would be too high. As noted above, TalkTalk is a member of the CP Group which has intervened in BT’s appeal in support of Ofcom.

(2) CityFibre Infrastructure Holdings plc (“CF”) lodged its appeal on 29 June 2016. CF operates pure fibre networks in around 35 UK cities. CF’s appeal partly overlapped with BT’s appeal, especially regarding the portions of BT’s appeal dealing with market definition (Grounds D1 and D2 of BT’s appeal). CF also contended that the DFA remedy was inappropriate. At Grounds 3 and 4b of its notice of appeal, CF raised specific arguments that the design of the DFA remedy was flawed. CF also intervened in support of BT in relation to certain aspects of its appeal.

15. For context we note that, in broad terms, BT’s arguments in respect of the DFA remedy were that:

(1) the DFA remedy is flawed and disproportionate because it targets only the most competitive segment of the market (i.e. VHB);

(2) Ofcom failed to take proper account of Directive 2014/61/EU (“the Civil Infrastructure Directive”) and, in particular, no consideration was given to the extent to which the claimed benefits of the DFA remedy would be achieved in any event following the implementation of the Civil Infrastructure Directive with effect from July 2016;

(3) Ofcom erred in conducting its cost-benefit analysis of the DFA remedy. In particular, Ofcom: (i) overstated the benefits of dark fibre; (ii) understated the risks of dark fibre; (iii) adopted an inconsistent approach to the timeframes for assessment of benefits and risks; (iv) failed to take into account the difficulty and costs of reversing the DFA remedy once implemented; and (v) failed to undertake a proper balancing exercise of the benefits and risks of the DFA remedy.

In addition, CF argued that if (which it denied) a remedy should be imposed, the more appropriate and proportionate remedy would be to enforce access to BT’s ‘duct and poles’ rather than DFA.

18. On 28 February 2017 the CMA issued its provisional determination of the specified PCMs in TalkTalk and CF’s appeals. The CMA indicated it had provisionally determined that Grounds 3 and 4b of CF’s appeal were ill-founded, but that TalkTalk’s appeal was well-founded. In summary, the CMA provisionally determined that Ofcom was wrong to decide that (in the absence of a change to the rating rules by further legislation) the rating costs to be deducted from the price of the reference active products in deriving the price for DFA should be based on an attribution of BT’s rates costs to the fibre, rather than some other appropriate measure. It further concluded that another appropriate measure would be one of access-seekers’ rates, which would be a materially higher sum. Further, the CMA indicated that it was minded to propose to the Tribunal that the matter be remitted to Ofcom, so that Ofcom could consult on how the DFA price might best be derived in a manner which took into account the CMA’s determination.

19. The Tribunal considered the implications of the CMA’s provisional determination at a pre-trial review on 29 March 2017. Ofcom argued that the provisional determination, were it to become final, would have relatively limited impact on the April hearing. Ofcom indicated that it would not seek a review of the CMA’s determination, but would instead conduct a swift consultation and reach a fresh decision in early summer 2017, recalibrating the DFA remedy in the light of the CMA’s findings. In the meantime, Ofcom contended, the April hearing should proceed with the Tribunal hearing arguments on all aspects of the case save for those elements concerning remedy which were affected by the CMA’s determination. BT and CF, on the other hand, argued that the CMA’s determination would have a profound impact on the remedy element of the proceedings. BT applied (with CF’s support) to have the substantive hearing adjourned until after Ofcom had reached its further decision on remedy.

20. The Tribunal indicated to the parties that the most appropriate course, should the CMA affirm its provisional determination, would be to order a split hearing between the market definition and remedy issues. Arguments concerning market definition would be heard in the existing April window, whilst any remedy issues would be re-fixed for a later date. This would avoid the risk of time-consuming satellite disputes concerning precisely which aspects of the remedy case should be heard in April and at the same time would make use of the existing window held in the parties’ and Tribunal’s diaries and allow a substantial and important aspect of the appeals to progress toward determination.

21. On 6 April 2017 the CMA reached its final determination of the specified PCMs, essentially affirming its provisional determination. Shortly afterward, CF wrote to the Tribunal indicating that it had reached agreement with Ofcom to amend its Notice of Appeal so as to remove its challenge in respect of market definition and the corresponding portions of its statement of intervention, but maintaining its position regarding remedy. CF therefore took no further part in the April hearing and the hearing dealt with only those aspects of BT’s appeal which concerned market definition and the extent of BT’s core conveyance network.

22. Ofcom issued its decision on the remitted matters on 30 June 2017. That remittal decision had no bearing on the matters at issue in this judgment.

23. On 26 July 2017 we issued a ruling setting out our decision in relation to the market definition issues in BT’s appeal and stated that our reasons would follow: [2017] CAT 17. We took this unusual step because it became clear to us that a remedies hearing in September would be unnecessary and we considered it desirable to inform the parties of this so as to avoid them incurring unnecessary costs. In our ruling, we unanimously concluded that:

(1) Ofcom erred in concluding that it was appropriate to define a single product market for CISBO services of all bandwidths;

(2) Ofcom erred in concluding that the RoUK comprises a single geographic market; and

(3) Ofcom erred in its determination of the boundary between the competitive core segments and the terminating segments of BT's network.

24. This judgment sets out our reasons for those findings. The judgment is structured as follows:

(1) Section B sets out the uncontroversial technical background relevant to this appeal.

(2) Section C sets out the relevant legal framework.

(3) Section D describes the witnesses and evidence in the appeal.

(4) Section E sets out the parties’ contentions in outline.

(5) Section F concerns BT’s ground of appeal relating to relevant product market.

(6) Section G concerns BT’s ground of appeal relating to relevant geographic market.

(7) Section H concerns BT’s ground of appeal relating to its core conveyance network.

(8) Section I summarises our conclusions.

25. We were greatly assisted by the parties preparing an agreed list of issues, which encapsulated the issues raised by BT’s Notice of Appeal and Ofcom’s Defence. The parties also sought to adhere to these agreed issues in the course of their written and oral arguments. For convenience, therefore, we have also used those issues to structure this judgment. As explained in section E below, issues 1-3 concerned product market definition, whilst issues 4 and 5 fell away before the hearing. Issues 6 and 7 concerned geographic market definition and issue 8 concerned the competitive core. A copy of the list of issues is annexed to this judgment at Annex 1. The judgment uses a number of abbreviations: for convenience a list of abbreviations is annexed to this judgment at Annex 2.

B. Technical Background

(1) Leased lines

26. Ofcom defined “leased lines” as “high-quality, dedicated, point-to-point data transmission services used by businesses and providers of communications services.”[6] Leased lines are used to transmit data over physical infrastructure and are available in various different capacities or “bandwidths” (these are also colloquially referred to as “speeds”), specified in terms of the number of individual bits of data they are able to carry per second. A leased line of 100Mb/s can carry 100 million bits per second; a leased line of 1Gb/s can carry 1 billion bits per second. In this judgment we use “1G”, “10G” and “100G” as shorthand for 1Gb/s etc. Similarly, we use “10M” and “100M” as shorthand for 10Mb/s and 100Mb/s.

27. Leased lines are built using fibre optic cables laid in ducts under the ground. Cables typically comprise around 200 individual strands, but can number as many as one thousand. Ducts can be different sizes and often there are smaller ducts, called sub-ducts, laid within the primary duct. The costs of digging and reinstatement (e.g. repairing road or pavement surfaces) are substantial and can also vary significantly from location to location. It is often also necessary to obtain wayleaves which can also add substantially to the cost and time required to dig trenches.

Figure 1: Fibre optic cables

28. Simplifying somewhat, fibre optic cables are made of strands of glass about the width of a human hair. Fibre optic cables have a massive potential capacity for carrying data: in an experiment in 2015 a record transmission rate of 2.15 Petabits per second was achieved over a 31km distance.[7]

(2) Ethernet and WDM technology

(3) Ethernet in the First Mile

32. As will be explained further below, Ofcom included EFM in its definition of a single product market for CISBO services on the basis that it exerted competitive pressures on lower bandwidth CISBO services, but excluded EFM in its network reach and boundary tests for the purpose of defining the relevant geographic markets on the basis that EFM could in principle be used to supply customers throughout an area and did not assist in identifying geographic variations in competitive conditions.

(4) BT's leased line products

(1) 100M (which can be configured to 10M if required);

(2) 1G; and

(3) 10G.

34. These bandwidths directly reflect the international standards for Ethernet interfaces and are the maximum bandwidth that can be carried by the relevant EAD service. However, downstream customers of Openreach can “throttle” the bandwidth of an overall end-to-end service and therefore limit the maximum bandwidth available to an end user.

35. BT's main WDM-based products are called Optical Spectrum Access, and Optical Spectrum Extended Access. The service can allow multiple wavelengths and each wavelength can be configured to carry 1G, 10G, 40G, or even 100G.

(5) Users of leased lines

(1) fixed access for business sites (“Business Access”);

(a) Business Access

38. The main element in the retail services relevant to the BCMR is the provision of connectivity between the sites of the business which is securely isolated from services provided by the CP to other customers. Such connectivity can be provided 'point-to-point' or via the creation of a VPN using the network of a downstream CP.

(b) Mobile Backhaul

(c) LLU Backhaul

40. LLU provides access to LLU operators to the pair of copper wires which directly connect a residential consumer's home to the BT local exchange. LLU operators (e.g. VM, TalkTalk and Sky) can place equipment in BT’s local exchanges and using LLU can thereby supply the mass market with packages of services comprising one or more of: public telephone service, broadband internet access and TV/video services. NGA involves either laying fibre to the customer’s premises (“Fibre to the Premises” or “FTTP”), bypassing the copper network completely or, much more commonly, running optical fibre from the local exchange to a street cabinet (“Fibre to the Cabinet” or “FTTC”) and installing equipment in the street cabinet to drive the higher bandwidth achievable using the shorter length of copper wire.

41. LLU and NGA are together referred to as “LLU Backhaul”. LLU operators purchase LLU Backhaul to provide their services. For example, Sky and TalkTalk, as major LLU operators, require access to roughly 3,000 of BT’s 5,500 local exchanges which account for over 90% of all homes in the UK. BT’s downstream unit also offers services to the mass market and, under regulations, must purchase LLU Backhaul from Openreach in an identical way to the LLU operators. The only significant difference is that BT downstream offers service from all of BT’s 5,500 local exchanges.

(6) Resilience

42. Since leased lines are critical components used to deliver many important services, reliability is a key requirement for many users. This means not only that leased lines are engineered to high standards to minimise the incidence of faults, but also that users take steps to minimise the impact of any fault. In many cases, the “downtime” when communication systems are inoperable due to a fault in a leased line, or an accident causing the severance of a line, will be unacceptable even if the supplier has in place effective fault management and repair processes. Similarly, downtime resulting from the failure of a commercial relationship with the supplier of the leased line can be equally unacceptable.

43. In such cases, the end-user requires resilience, which means that two separate leased lines are used in parallel, so that if one fails the other remains available. Resilience can be in the form of physical resilience (constructing the two leased lines in two separate physical paths), and/or commercial resilience (purchasing leased lines from two different CPs). The strongest form of resilience would be to have two separate paths and two separate providers, the next strongest would be two separate paths but the same provider, then the same path but two separate providers. Finally it is also possible to have a single path and a single provider but to purchase two strands on that path to provide some degree of resilience in the event of electronics systems failure.

C. The Legal Framework

44. This section sets out the relevant legal framework at both EU and national level. It also refers to some of the relevant guidance documents, along with an explanation of the principles governing the standard of review to be carried out by this Tribunal on this appeal.

(1) The EU Common Regulatory Framework

(a) The FD

46. Article 8 FD sets out the policy objectives and regulatory principles to be observed by NRAs in carrying out the regulatory tasks specified in the FD and in the AD. Among other things, NRAs must take reasonable and proportionate measures aimed at achieving objectives which include the promotion of competition, the development of the internal market, and the promotion of the interests of the citizens of the EU.

47. Article 8(5) FD provides:

“5. The national regulatory authorities shall, in pursuit of the policy objectives referred to in paragraphs 2, 3 and 4, apply objective, transparent, non-discriminatory and proportionate regulatory principles by, inter alia:

(a) promoting regulatory predictability by ensuring a consistent regulatory approach over appropriate review periods;

(b) ensuring that, in similar circumstances, there is no discrimination in the treatment of undertakings providing electronic communications networks and services;

(c) safeguarding competition to the benefit of consumers and promoting, where appropriate, infrastructure-based competition;

(d) promoting efficient investment and innovation in new and enhanced infrastructures, including by ensuring that any access obligation takes appropriate account of the risk incurred by the investing undertakings and by permitting various cooperative arrangements between investors and parties seeking access to diversify the risk of investment, whilst ensuring that competition in the market and the principle of non-discrimination are preserved;

(e) taking due account of the variety of conditions relating to competition and consumers that exist in the various geographic areas within a Member State;

(f) imposing ex-ante regulatory obligations only where there is no effective and sustainable competition and relaxing or lifting such obligations as soon as that condition is fulfilled.”

48. Articles 14-16 FD concern the identification of markets and SMP.

49. Article 14(2) FD provides that where the specific Directives require NRAs to determine whether operators have SMP in accordance with the market analysis procedure referred to in Article 16 FD, an undertaking shall be deemed to have SMP if:

“either individually or jointly with others, it enjoys a position equivalent to dominance, that is to say a position of economic strength affording it the power to behave to an appreciable extent independently of competitors, customers and ultimately consumers.”

50. Article 15(1) FD requires the Commission to adopt a Recommendation on Relevant Product and Service Markets which identifies those product and service markets within the electronic communications sector, the characteristics of which may be such as to justify the imposition of regulatory obligations set out in the specific Directives. Article 15(2) requires the Commission to publish guidelines for market analysis and the assessment of SMP. Article 15(3) requires NRAs, taking utmost account of the Recommendation and Guidelines, to define relevant markets appropriate to national circumstances, in particular relevant geographic markets within their territory, in accordance with the principles of competition law.

51. Article 16 FD concerns the market analysis procedure and provides as relevant:

“1. National regulatory authorities shall carry out an analysis of the relevant markets taking into account the markets identified in the Recommendation, and taking the utmost account of the Guidelines. Member States shall ensure that this analysis is carried out, where appropriate, in collaboration with the national competition authorities.

2. Where a national regulatory authority is required under paragraphs 3 or 4 of this Article, Article 17 of Directive 2002/22/EC (Universal Service Directive), or Article 8 of Directive 2002/19/EC (Access Directive) to determine whether to impose, maintain, amend or withdraw obligations on undertakings, it shall determine on the basis of its market analysis referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article whether a relevant market is effectively competitive.

3. Where a national regulatory authority concludes that the market is effectively competitive, it shall not impose or maintain any of the specific regulatory obligations referred to in paragraph 2 of this Article. In cases where sector specific regulatory obligations already exist, it shall withdraw such obligations placed on undertakings in that relevant market. An appropriate period of notice shall be given to parties affected by such a withdrawal of obligations.

4. Where a national regulatory authority determines that a relevant market is not effectively competitive, it shall identify undertakings which individually or jointly have a significant market power on that market in accordance with Article 14 and the national regulatory authority shall on such undertakings impose appropriate specific regulatory obligations referred to in paragraph 2 of this Article or maintain or amend such obligations where they already exist.”

(b) The AD

53. The AD harmonises the way in which the Member States regulate access to, and interconnection of, electronic communications networks and associated facilities.

54. Article 1(1) explains:

“The aim is to establish a regulatory framework, in accordance with internal market principles, for the relationships between suppliers of networks and services that will result in sustainable competition, interoperability of communications services and consumer benefits.”

55. Article 5(1) provides that NRAs shall, acting in pursuit of the objectives set out in Article 8 FD, “encourage and where appropriate ensure, in accordance with the provisions of this Directive, adequate access and interconnection, and the interoperability of services, exercising their responsibility in a way that promotes efficiency, sustainable competition, efficient investment and innovation, and gives the maximum benefit to end-users.”

56. Article 5(2) provides:

“Obligations and conditions imposed in accordance with paragraph 1 shall be objective, transparent, proportionate and non-discriminatory [...].”

57. Article 8(2) AD provides that, where an operator is designated as having SMP on a specific market as a result of a market analysis carried out in accordance with Article 16 FD, NRAs shall impose the obligations set out in Articles 9 to 13 AD as appropriate. Article 8(3) provides that such obligations shall not be imposed on operators which have not been designated as having SMP. Under Article 8(4) AD, any obligations imposed on SMP operators shall be “based on the nature of the problem identified, proportionate and justified in the light of the objectives laid down in Article 8 [FD]”.

58. The obligations that can be imposed by an NRA include obligations of access to and use of specific network facilities under Article 12, and the imposition of price control and cost accounting obligations under Article 13.

(2) The 2003 Act

59. Ofcom’s general duties are set out in section 3 of the 2003 Act. Ofcom’s principal duty, as set out at section 3(1), is:

“(a) to further the interests of citizens in relation to communications matters; and

(b) to further the interests of consumers in relevant markets, where appropriate by promoting competition.”

60. Section 3(3) provides:

“In performing their duties under subsection (1), Ofcom must have regard, in all cases, to—

(a) the principles under which regulatory activities should be transparent, accountable, proportionate, consistent and targeted only at cases in which action is needed; and

(b) any other principles appearing to Ofcom to represent the best regulatory practice.”

61. Section 3(4) provides that Ofcom must also have regard to various matters as appear to them to be relevant in the circumstances, including inter alia:

“(b) the desirability of promoting competition in relevant markets;

[…]

(d) the desirability of encouraging investment and innovation in relevant markets;”

62. Section 4(2) requires Ofcom, in carrying out its functions as NRA, to act in accordance with the six “Community requirements”, which give effect to the requirements in Article 8 FD.

63. Section 6 provides :

“(1) Ofcom must keep the carrying out of their functions under review with a view to securing that regulation by Ofcom does not involve—

(a) the imposition of burdens which are unnecessary; or

(b) the maintenance of burdens which have become unnecessary.”

64. Section 79 provides that, before making a market power determination, Ofcom must identify the relevant market and carry out an analysis of the relevant market. The relevant subsections are as follows:

“(1) Before making a market power determination, Ofcom must—

(a) identify (by reference, in particular, to area and locality) the markets which in their opinion are the ones which in the circumstances of the United Kingdom are the markets in relation to which it is appropriate to consider whether to make the determination; and

(b) carry out an analysis of the identified markets.

(2) In identifying or analysing any services market for the purposes of this Chapter, Ofcom must take due account of all applicable guidelines and recommendations which—

(a) have been issued or made by the European Commission in pursuance of the provisions of an EU instrument; and

(b) relate to market identification and analysis.

(3) In considering whether to make or revise a market power determination in relation to a services market, Ofcom must take due account of all applicable guidelines and recommendations which—

(a) have been issued or made by the European Commission in pursuance of the provisions of an EU instrument; and

(b) relate to market analysis or the determination of what constitutes significant market power.”

65. Section 78 provides that a person shall be taken to have SMP in relation to a market if he enjoys a position which amounts to or is equivalent to dominance of the market.

66. Where Ofcom determines that a person has SMP within a particular market then, under sections 45(1) and 45(2)(b)(iv) of the 2003 Act, Ofcom has the power to set an “SMP condition”.

67. Section 47 provides, inter alia, that:

“(1) Ofcom must not, in exercise or performance of any power or duty under this Chapter—

(a) set a condition under section 45, or

(b) modify such a condition,

unless they are satisfied that the condition or (as the case may be) the modification satisfies the test in subsection (2).

(2) That test is that the condition or modification is—

(a) objectively justifiable in relation to the networks, services, facilities, apparatus or directories to which it relates (but this paragraph is subject to subsection (3));

(b) not such as to discriminate unduly against particular persons or against a particular description of persons;

(c) proportionate to what the condition or modification is intended to achieve; and

(d) in relation to what it is intended to achieve, transparent.”

68. The “SMP conditions” which may in principle be imposed under section 45 are those which are authorised or required by one or more of sections 87 to 92. Of relevance in these proceedings are sections 87 and 88. Section 87 contains powers, inter alia, to require a CP with SMP to provide access to its network and impose price controls. Section 88 limits the circumstances in which a price control can be imposed, to ensure that they are imposed only where to do so is appropriate.

(3) Guidance documents

69. Four guidance documents were referred to in the course of submissions. These were:

(3) The Office of Fair Trading’s market definition guidance, OFT403, 1 December 2004 (the “OFT Guidance”).

We shall refer to relevant parts of these guidance documents as required in this ruling.

(4) Review in the Tribunal

(a) Burden and standard of proof

(b) The role of the Tribunal

71. Section 192 of the 2003 Act explains what decisions are appealable to the Tribunal. Section 192(6) provides that the grounds of appeal must be set out in sufficient detail to indicate: (a) to what extent, if any, the appellant contends that the decision appealed against was based on an error of fact or was wrong in law, or both; and (b) to what extent, if any, the appellant is appealing against the exercise of a discretion by Ofcom, or others.

72. Section 195(2) of the 2003 Act sets out the Tribunal’s task on an appeal under section 192. It provides that the Tribunal must decide the appeal “on the merits” and by reference to the grounds of appeal set out in the notice of appeal. That reference to an appeal “on the merits” reflects the terms of Article 4(1) FD which provides:

“Member States shall ensure that effective mechanisms exist at national level under which any user or undertaking providing electronic communications networks and/or services who is affected by a decision of a national regulatory authority has the right of appeal against the decision to an appeal body that is independent of the parties involved. This body, which may be a court, shall have the appropriate expertise to enable it to carry out its functions effectively. Member States shall ensure that the merits of the case are duly taken into account and that there is an effective appeal mechanism.”

73. In British Telecommunications plc v Telefonica O2 Ltd & Ors [2014] UKSC 42 at [24], Lord Sumption (with whom all the other members of the Supreme Court agreed) explained that:

“Under section 192 of the Communications Act 2003, an appeal to the CAT is an appeal on the merits. It is a rehearing, and is not limited to judicial review or to points of law. This reflects the requirements of Article 4 of the Framework Directive.”

74. The detailed approach to appeals on the merits under section 192 has been the subject of consideration in a number of decisions. In British Telecommunications Plc v Office of Communications [2010] CAT 17 at [69] – [78] the Tribunal stated:

“70 […] the first limb of section 193(2) quite clearly requires that the appeal be conducted “on the merits” and not in accordance with the rules that would apply on a judicial review. This point was very clearly made in Hutchison 3G UK Limited v Office of Communications [2008] CAT 11 at paragraph [164]:

“However, this is an appeal on the merits and the Tribunal is not concerned solely with whether the 2007 Statement is adequately reasoned but also with whether those reasons are correct. The Tribunal accepts the point made by H3G in their Reply on the SMP and Appropriate Remedy issues that it is a specialist court designed to be able to scrutinise the detail of regulatory decisions in a profound and rigorous manner. The question for the Tribunal is not whether the decision to impose a price control was within the range of reasonable responses but whether the decision was the right one.”

We consider that this correctly states the legal consequences of section 193(2).

71 That said, Jacob LJ in T-Mobile (UK) Limited v Office of Communications [2008] EWCA Civ 1373 made absolutely clear that the section 192 Appeal Process is not intended to duplicate, still less, usurp, the functions of the regulator. In paragraph [31], he stated:

“After all it is inconceivable that Article 4 [of the Framework Directive], in requiring an appeal which can duly take into account the merits, requires Member States to have in effect a fully equipped duplicate regulatory body waiting in the wings just for appeals. What is called for is an appeal body and no more, a body which can look into whether the regulator had got something materially wrong. That may be very difficult if all that is impugned is an overall value judgment based upon competing commercial considerations in the context of a public policy decision.”

[…]

76 By section 192(6) of the 2003 Act and rule 8(4)(b) of the 2003 Tribunal Rules, the notice of appeal must set out specifically where it is contended Ofcom went wrong, identifying errors of fact, errors of law and/or the wrong exercise of discretion. The evidence adduced will, obviously, go to support these contentions. What is intended is the very reverse of a de novo hearing. Ofcom's decision is reviewed through the prism of the specific errors that are alleged by the appellant. Where no errors are pleaded, the decision to that extent will not be the subject of specific review. What is intended is an appeal on specific points.

77 The nature of the appeal before the Tribunal is similarly made clear in sections 193(3) and (4) of the 2003 Act. These sections make plain that it is not for the Tribunal to usurp Ofcom's decision-making role. The Tribunal's role is not to make a fresh determination, but to indicate to Ofcom what (if any) is the appropriate action for Ofcom to take in relation to the subject-matter of the decision under appeal and then to remit the matter back to Ofcom.”

(Emphasis in original.)

75. These paragraphs were referred to with approval by the Tribunal in British Sky Broadcasting Ltd and ors v Ofcom [2012] CAT 20, an appeal from a decision under section 316 of the 2003 Act. At [76] the Tribunal then observed, in relation to appeals concerning findings of fact:

“It is clear (and appears to be common ground) that in a case such as this the Tribunal has jurisdiction to assess and find the facts in so far as they are relevant to the grounds of appeal, and must do so in the light of the admissible material that is before it. If, having evaluated the evidence, the Tribunal finds that a material finding of fact made by Ofcom is wrong, then it must so hold and proceed accordingly. Although a finding of fact obviously involves an evaluation of the evidence, this is not an exercise of discretion, and there is no margin of appreciation (as that notion is generally understood in this context) in relation to such findings, any more than for decisions on points of law.”

76. So far as appeals against the exercise of discretion or judgement by Ofcom is concerned, and having reviewed a number of authorities the Tribunal continued, at [84]:

“Having regard to the parties’ submissions and the authorities to which our attention was drawn, we consider that the following principles should inform our approach to disputed questions upon which Ofcom has exercised a judgment of the kind under discussion:

(a) Since the Tribunal is exercising a jurisdiction “on the merits”, its assessment is not limited to the classic heads of judicial review, and in particular it is not restricted to an investigation of whether Ofcom's determination of the particular issue was what is known as Wednesbury unreasonable or irrational or outside the range of reasonable responses.

(b) Rather the Tribunal is called upon to consider whether, in the light of the grounds of appeal and the evidence before it, the determination was wrong. For this purpose it is not sufficient for the Tribunal simply to conclude that it would have reached a different decision had it been the designated decision-maker.

(c) In considering whether the regulator's decision on the specific issue is wrong, the Tribunal should consider the decision carefully, and attach due weight to it, and to the reasons underlying it. This follows not least from the fact that this is an appeal from an administrative decision not a de novo rehearing of the matter, and from the fact that Parliament has chosen to place responsibility for making the decision on Ofcom.

(d) When considering how much weight to place upon those matters, the specific language of section 316 to which we have referred, and the duration and intensity of the investigation carried out by Ofcom as a specialist regulator, are clearly important factors, along with the nature of the particular issue and decision, the fullness and clarity of the reasoning and the evidence given on appeal. Whether or not it is helpful to encapsulate the appropriate approach in the proposition that Ofcom enjoys a margin of appreciation on issues which entail the exercise of its judgment, the fact is that the Tribunal should apply appropriate restraint and should not interfere with Ofcom's exercise of a judgment unless satisfied that it was wrong.”

77. These observations were expressly endorsed on appeal: see British Telecommunications plc v Ofcom and others [2014] EWCA Civ 133 at [88] per Aikens LJ. They have also since been adopted in other Tribunal decisions under section 192 of the 2003 Act: see e.g. British Telecommunications plc v Ofcom [2014] CAT 14 at [62]-[67].

78. Of themselves, these statements of principle do not fully explain what the Tribunal is to do if it finds an error in the facts or law upon which a decision was based, or (exercising sufficient restraint) is satisfied that an exercise of judgement was wrong. The answer is that the Tribunal must also be satisfied that the decision itself cannot stand in light of that error and that it cannot be supported on some other ground. This follows from the judgment of Moses LJ in Everything Everywhere Ltd v Competition Commission (Mobile Call Termination) [2013] EWCA Civ 154 at [23]-[24]:

“23 It is for an appellant to establish that Ofcom's decision was wrong on one or more of the grounds specified in s.192(6) of the 2003 Act: that the decision was based on an error of fact, or law, or both, or an erroneous exercise of discretion. It is for the appellant to marshal and adduce all the evidence and material on which it relies to show that Ofcom's original decision was wrong. Where, as in this case, the appellant contends that Ofcom ought to have adopted an alternative price control measure, then it is for that appellant to deploy all the evidence and material it considers will support that alternative.

24 The appeal is against the decision, not the reasons for the decision. It is not enough to identify some error in reasoning; the appeal can only succeed if the decision cannot stand in the light of that error […] If the Commission (or Tribunal in a matter unrelated to price control) concludes that the original decision can be supported on a basis other than that on which Ofcom relied, then the appellant will not have shown that the original decision is wrong and will fail.”

79. Moses LJ also went on, at [25], to consider how an appellant might seek to discharge the burden upon it, and to outline the options open to the Tribunal in the event that the appellant succeeded:

“25 Usually an appellant will succeed by demonstrating the flaws in the original decision and the merits of an alternative solution. But that is not necessarily so. I would not rule out the possibility that there could be a case where an appellant succeeds in so undermining the foundations of a decision that it cannot stand, without establishing what the alternative should be. In such a case, if there is no other basis for maintaining the decision, the Commission or Tribunal would be at liberty to conclude that the original decision was wrong but that it could not say what decision should be substituted. The Tribunal would then be required to allow the appeal under s.195(2) and direct Ofcom to make a fresh decision with such directions as the Tribunal thinks are necessary to reach a properly informed conclusion. The Tribunal may wish to specify the steps to be taken by Ofcom to make good any deficit in evidence and material so as to reach a fresh decision, or leave it to Ofcom to act as it sees fit in the light of the Commission's conclusion.”

(c) New evidence

80. As we shall explain later in this judgment, after the Final Statement had been issued and during the course of the appeal proceedings, it emerged that an important piece of factual information supplied to Ofcom by BT during the BCMR process, and upon which it became apparent that Ofcom had placed significant reliance in coming to its decision on market definition, had been wrong. Ofcom raised no objection to the admission of evidence from BT explaining the error and showing what it contended that the correct position was: Ofcom did, however, submit that its product market decision was correct on either basis.

81. The explanation for Ofcom’s position on the question of admission of new evidence is to be found in the following extracts from the judgment of Toulson LJ in the Court of Appeal in British Telecommunications plc v Ofcom [2011] EWCA Civ 245 at [60] – [71],

“60 The task of the appeal body referred to in article 4 of the Framework Directive is to consider whether the decision of the national regulatory authority is right on “the merits of the case”. In order to be able to make that decision the Framework Directive requires that the appeal body “shall have the appropriate expertise available to it”. There is nothing in article 4 which confines the function of the appeal body to judgment of the merits as they appeared at the time of the decision under appeal. The expression “merits of the case” is not synonymous with the merits of the decision of the national regulatory authority. The omission from article 4 of words limiting the material which the appeal body may consider is unsurprising. When an appeal body is given responsibility for considering the merits of the case, it is not typically limited to considering the material which was available at the moment when the decision was made. There may be powerful reasons why an appeal body should decline to admit fresh evidence which was available at the time of the original decision to the party seeking to rely on it at the appeal stage, but that is a different matter.”

[…]

70 Under article 4 of the Framework Directive, the appeal body is concerned not merely with Ofcom's process of determination but with the merits. Ofcom is not only an adjudicative but an investigative body, and the appellant may wish to produce material, or further material, to rebut Ofcom's conclusions from its investigation. It is unsurprising that the CAT should adopt a more permissive approach towards the reception of fresh evidence than a court hearing an appeal from a judgment following the trial of a civil action. Indeed, as Sullivan LJ observed, the appeal body might in some cases expect an appellant to produce further material to address criticisms or weaknesses identified by Ofcom.

71 Ofcom submitted in its skeleton argument that an unfettered right to adduce fresh evidence on appeal might cause parties to avoid proper engagement with Ofcom during the dispute resolution process. No party has an unfettered right to adduce fresh evidence on an appeal to the CAT, and there is force in Ms Rose's argument that parties ought to be encouraged to present their case to Ofcom as fully as the circumstances permit. That is a factor, among others, to be borne in mind by the CAT when considering the discretionary question whether to admit fresh evidence. Other relevant factors would include the potential prejudice (in costs, delay or otherwise) which other parties may suffer if an appellant is permitted to introduce material that it could reasonably have been expected to place before Ofcom. These are not necessarily the only relevant factors.”

We shall return to consider the consequences of the erroneous evidence provided by BT to Ofcom in greater detail later in this judgment.

(d) Standard applicable in future appeals

82. For completeness, we note that the ‘on the merits’ standard of review will no longer apply to appeals from decisions of Ofcom made on or after 1 August 2017 owing to the coming into force of section 87 of the Digital Economy Act 2017, which was brought into effect by the Digital Economy Act 2017 (Commencement No. 1) Regulations 2017 (2017 S.I. 675). In future, such decisions will be determined by the Tribunal applying the same principles as would be applied by a court on an application for judicial review.

D. Witnesses and Evidence

(1) Factual evidence

83. A total of 11 factual witnesses gave evidence, and all but one (Mr Baxter) was called for cross-examination. BT called Mr Andy Reid, Mr Mark Logan and Mr David Beal. Ofcom called Mr Gideon Senensieb. VM called Mr Duncan Higgins. The CP Group called Mr Mark Allinson and Mr Alexander Connors (both of Vodafone), Mr Barnaby Lane (Colt), Mr Simon Pilsbury (TalkTalk) and Mr Graham Baxter (Three). Finally, Gamma called Mr Peter Farmer.

84. As a rule, but subject to the general comments which we make in section D(3) below, we found all of the factual witnesses to be credible and reliable. We would, however, add the following brief comments:

(1) Mr Logan (Director of Fibre Products within Openreach) at times (certainly early in his cross-examination) appeared rather defensive and intent upon advancing BT’s case when answering questions.

(3) Mr Connors (Head of Fixed Connectivity Services at Vodafone) relied upon written evidence that was shown to contain certain errors. To his credit, however, he was ready to acknowledge those errors in cross-examination.

(2) Expert evidence

85. We heard from the following witnesses who were put forward as (in whole or in part) as expert witnesses:

BT

86. Dr Matt Yardley. Dr Yardley works for Analysys Mason, a management consultancy and research company. Dr Yardley is head of Analysys Mason’s Manchester Office and a member of the company’s senior management team. Dr Yardley advises companies on a wide range of issues relating to fixed networks. We thought that Dr Yardley was somewhat defensive initially, and that on occasions he gave evidence on economics which fell outside his area of expertise. Overall, however, we found his evidence to be reliable and of assistance.

87. Dr Bruno Basalisco. Dr Basalisco is an economist working as a consultant at Copenhagen Economics. Dr Basalisco provided three lengthy reports focussed on the issues of market definition and BT’s core conveyance network. It appeared to us that Dr Basalisco lacked the objectivity and balance required of an independent expert witness. Rather than explaining the relevant economic principles in neutral or objective terms for our assistance, Dr Basalisco’s written material was couched throughout as a one-sided argument and critique of Ofcom’s reasoning and approach. Moreover, whilst Dr Basalisco exhibited an impressive recall and command of the written materials, in cross-examination we thought that he was intent on seeking to promote BT’s case by advancing arguments, rather than simply answering the questions he had been asked. Accordingly, we regret that we were not assisted by much of Dr Basalisco’s evidence.

88. Two examples will suffice to illustrate our point. In his first report, under the heading “The hypothetical monopolist in a multi-product industry benefits from SSNIP-induced migration across products” Dr Basalisco advanced a theory as to how Ofcom should have applied the hypothetical monopolist test. He said:

“270. In addition, Ofcom is wrong in considering that upwards migration is a demand constraint for the pricing of Medium or High CISBO products. One must not forget that upwards migration of end users’ needs’ is actually a boon for the industry supplying wholesale leased lines - infrastructure-based operators which are multi-product firms selling both the products end users migrate from and migrate to.

271. Thus, it is not factually or conceptually consistent to portray upwards migration in user needs as an additional demand constraint: neither for each of the current infrastructure-based operators nor for the entire set of these operators (considered together as the hypothetical monopolist). All else equal, upward migration of customer needs enables each firm (and the hypothetical monopolist) to increase prices for Medium or High CISBO products, since promoting buyers’ trading up leads to higher profits for multi-product suppliers.

272. In the previous subsection, I quantified the effect of migration as a very small volume effect. In this section, I argue that this very small effect actually has the opposite implication for the purpose of product market definition than what Ofcom considered. This effect of upward migration increases the case for CISBO medium or High products to be a market worth monopolising i.e. a separate product market distinct from 10Gb - the opposite of Ofcom’s interpretation of the effect of upward migration of user needs.

273. The argument in this subsection is logically consistent with market features recognised by Ofcom, i.e. the multi-product nature of fibre networks. Thus, when defining the hypothetical monopolist e.g. of 1Gb Ethernet products it is strictly necessary (even if superficially counterintuitive) to consider that the very same hypothetical monopolist is also the supplier of 10Gb lines and thus earns the revenues after trading up is induced by the SSNIP. The hypothetical monopolist benefits from up-selling in the same way that each individual supplier of wholesale leased lines does when a price increase promotes end user migration to a higher service level.”

89. In cross-examination, Dr Basalisco adhered to this opinion, which he expressed without qualifying it in any way, volunteering that he thought that the contrary approach taken by Ofcom’s witness, Ms. Curry, was “absurd”. However, it became apparent that Dr Basalisco’s argument was unsupported by any authority or guidance and had never been adopted by any competition authority or regulator. If attempting to give independent expert evidence for the assistance of the Tribunal, we think that Dr. Basalisco ought at very least to have drawn this important factor to our attention:

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

You say there that when defining the hypothetical monopolist, it is strictly necessary, even if superficially counter-intuitive, to consider that the very same hypothetical monopolist is also the supplier of lOG lines and thus earns the revenues after trading-up is induced by a SSNIP. That is your position, is it not? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

Yes, in this context, that is my position. |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

This is a case of “heads I win, tails you lose”. The hypothetical monopolist picks up the sales at 10G which it loses at 1G. Is that right? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

I think in this market, given the nature of the product and infrastructure used to provide it, assuming otherwise, which is what Curry has done in the report, is an assumption which is disconnected by the fact that it is absurd and does not hold. Upon reflection, this reflection is both in Basalisco 1 and Basalisco 3. I have chosen what I think is the safest option to --- |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

So the 10% price increase at 1G might actually lead the hypothetical monopolist to benefit from the sales which it lost in response as a result of substitution to its 10G product. Is that right? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

For the reason that suppliers individually in this market also supply at 1GB, and in the and next behind Basalisco report 1, I have checked that all key suppliers listed by Ofcom supply both 1G product and VHB product, therefore their commercial incentives are to promote migration up. It is an industry boon. It is an advantage for each individual supplier, and suppliers taken together, that customers move to more expensive products and faster products. They all welcome that individually. They also welcome it in the guise of the hypothetical monopolist. Assuming otherwise, which is what Curry does, implicitly or explicitly, to me is absurd and does not capture in this market, specifically at 1G to 10G, not perhaps at the bottom of the market, what is the reality of the competitive constraints faced by a supplier individually or taken as a hypothetical monopolist. |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

There is no distinction on that approach between the focal product and the main substitute product. They are both supplied by the same hypothetical monopolist supplier. That is your position. |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

My position is that it is not tenable to assume otherwise. It is not tenable to assume that there is a company that supplies l0G using not yet a clear infrastructure that is not also a member of the hypothetical monopolist at 1G, because it is fibre infrastructures that allow the nature of this product to be -- it is the nature of the product. |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

Just to situate this, you would accept there is no support for your approach in any of the guidance on market definition. |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

I would say that the guidance is silent on this point. Perhaps this specific market context is not a general situation in many markets. Indeed, in the bottom end of BCMR, I think if we were to do a SSNIP on 10Mb, for instance – |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

I think you are straying from my question, Dr. Basalisco. My question was simply, is there any support for this approach in any of the guidance on market definition? I think your answer is they are silent on the point. Is that correct? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

Yes. |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

And you agree that in the relevant guidelines, the assessment is framed purely in terms of balancing the greater profits made on the retained sales of the focal product against the profits lost to substitutes. That is correct, is it not? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

The focus is on whether there are profits being lost. That is what we are discussing now. |

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

You are not aware of any instance of a regulator or competition authority ever having presumed that the hypothetical monopolist also monopolized products other than the focal product, are you? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

No.[8] |

90. Dr. Basalisco then sought to argue what he perceived to be the facts of the case in spite of it being pointed out to him that the hypothetical monopolist test is a thought experiment rather than a reality-based test:

|

Q (Mr Holmes) |

And the purpose of the SSNIP test is that it is an abstraction. It is, by its nature, a departure from reality. You are assuming in relation to a market with plural suppliers that for the focal product there is only one supplier. It is, by its nature not the real world. Would you accept that? |

|

A (Dr Basalisco) |

I would only accept that the purpose of assuming a hypothetical monopolist is to eliminate the effect of churn, the effect of one customer responding to 10% price increase from a supplier by going to another supplier of the same 1G product. That is what is then looked at later on in terms of the market power assessment and all the following stages of analysis. For the purpose of market definition, that is the only one we need to assume away. Then we need to look at the reality of what are the incentives. Is there anything that constrains the discipline, the pricing, the 10% price increase, of suppliers of a 10 product? If we were to merge together all the companies that supply wholesale lease lines, BT, Virgin Media, CityFibre, and all those—if we were to merge together into an industry board all the wholesale suppliers of lease lines, BT, Virgin Media, CityFibre, would they be disciplined by the 10G product if they were to raise collectively as a joint entity the price of 1G? They would be laughing all the way to the bank. They would be happy to promote migration of customers. They would not be disciplined in the supply and pricing of 1G by the existence of the l0G product. The same question with 10MB would give a different answer. My point is not a generally applicable point, but it refers to the specific reality of this market […].[9] |

91. The second example of Dr Basalisco making submissions rather than giving evidence concerned the section of his third report headed “Limited relevance of the Aberdeen Journals precedent, given the facts of this appeal”. He stated:

“75. I believe that, in the context of the BCMR, Ofcom finds itself in a more favourable position as regard evidence gathering than that faced by many other agencies that are required to undertake market definition exercises. In particular, Ofcom has a relatively long time to carry out evidence gathering, access to evidence from a wide range of market participants (which may not be the case in a discrete competition investigation) and the benefit of experience from past BCMRs, which allow it to adapt its analytical techniques in light of what has and has not worked well in the past. Ofcom also benefits from wide-ranging and intrusive information gathering powers that legally oblige market participants to respond to its information requests.

76. Thus, it is somewhat surprising to see considerable effort in Ofcom’s Defence in explaining why it was appropriate for Ofcom not to rely on evidence, especially quantitative evidence, in the context of the BCMR.

77. The Defence §156 goes as far as making the remarkable statement that one of Ofcom’s commissioned surveys (the 2016 BDRC Survey) “was not intended to be used for a quantitative analysis”. This statement refers to a 90-page survey which sought and reported a large amount of statistics and quantitative information. In particular, this survey provides the results of Ofcom’s own-commissioned SSNIP questions (results of questions named in the survey as SSNIP1, SSNIP2, SSNIP3, SSNIP4, see BDRC 2016 Survey, pp. 56-59 in the section named “Hypothetical price increases”).

78. Ofcom’s Defence §175 refers to the Aberdeen Journals CAT precedent and states that the value of quantitative analysis depends on the facts. I re-state below the factors stated in Aberdeen Journals which in that case drove the choice not to rely on survey-based and other quantitative analyses of substitutability, deemed (i) not to be robust enough and; (ii) unnecessary given the availability of other sufficient sources of evidence. I then compare the factors in the Aberdeen Journals case with the situation in this appeal.

79. I consider that the case specific factors that drove the DGFT/OFT and CAT to conclude that survey-based evidence was not reliable in Aberdeen Journals are mainly not relevant for the BCMR case. I concluded this on the basis of the analysis presented in Appendix, which includes:

• A Box highlighting the key paragraphs in Aberdeen Journals on the value of and limitations of quantitative analysis for the purpose of market definition

• A Table comparing factors limiting the availability of reliable economic evidence in Aberdeen Journals vs BCMR

80. My review of the relevant facts of the case in Aberdeen Journals vs. this appeal concludes that quantitative data and analysis relevant to Ofcom’s BCMR market definition are not affected by the same type of bias and the same extent of unreliability as was the case in Aberdeen Journals for the DGFT/OFT. Thus, insofar as Ofcom relies on Aberdeen Journals as a relevant precedent, this may be severely impaired by the facts of the BCMR case.”

92. The Table referred to in the second bullet of para 79, is labelled “Supporting arguments”.

93. The Table provided as follows:

|

Table 1: Dr Basalisco’s “Comparison of factors limiting the availability of reliable economic evidence in Aberdeen Journals vs BCMR (Table 4 of Appendix to Basalisco 3)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: First column: [2003] CAT 11 (Aberdeen Journals), §260, §262. Rest of the table: my analysis. |

94. This entire text was pure argument and did not relate to any matters that properly fell into the scope of an expert witness on economics. Whilst it is not surprising that Dr Basalisco should be familiar with Ofcom’s defence and, indeed, the Tribunal’s case law, including the Aberdeen Journals case, it is clearly inappropriate for an expert witness to seek to “fight back” against a pleading and do so by reference to an entirely unrelated dispute.

Ofcom

95. Ms Katie Curry. Ms Curry works for Ofcom as an Economic Director. Ms Curry provided two reports which focussed on the issues of market definition and BT’s core conveyance network. Ms Curry’s reports also openly acknowledged that, in part, they contained factual evidence as to how Ofcom had reached its decisions in the Final Statement, with which she had clearly been closely involved. Ms. Curry explained that she started working on the BCMR after the close of the consultation in May 2015 and that in her role she “oversaw the economics analysis that informed Ofcom’s market definition analysis as part of the BCMR.”

96. In part, therefore, Ms. Curry is properly to be regarded as a witness of fact. We do not doubt that Ms. Curry also had the necessary qualifications and experience to be an expert witness on economic issues. We also thought that she gave her evidence honestly and conscientiously, and that she was seeking as best she could to assist the Tribunal in an impartial manner. But we nevertheless felt that the fact that Ms. Curry was attempting to perform the multiple roles of giving factual evidence as to a decision with which she had been involved, answering BT’s arguments and criticisms of that decision, and giving expert opinion evidence on economic issues, meant that it was often difficult to distinguish which role Ms. Curry was performing. It also meant that to some extent (though far less than Dr. Basalisco) Ms. Curry tended to be an advocate for Ofcom’s cause.

97. So, for example, the way in which Ms. Curry’s written evidence contained both factual evidence and argument was illustrated by the following exchange in relation to Ms. Curry’s statement concerning the outcome of a SSNIP test at 10G:

|

Q (Mr Beard) |

[In] Paragraph 61 [of your report] you say: "I also consider that the evidence Ofcom presented, taken in the round, suggests a SSNIP on 10Gbit/s Ethernet connections would be likely to be rendered unprofitable by the constraint from lower bandwidth Ethernet connections (and particularly 1Gbit/s Ethernet services). I consider this constraint would be likely to come from the following sources…". Again, this is not language or a conclusion we find in the final statement, is it? |

|

A (Ms Curry) |

No. Again, I was re-presenting the focus of the analysis in response to BT's appeal. The presentation in the final statement reflects my discussion earlier about what I see as the core essence of the market definition question, which is whether two products are sufficiently substitutable to be considered within the same relevant market. BT takes a special focus on the implementation of the SSNIP and so I have reformulated the evidence to more clearly address BT's concerns in relation to the SSNIP. [10] |

|

Q (Mr Beard) |

We have been referring to the time period within which you take into account switching and I would suggest to you that the relevant time period should be one year. Do you accept that in this case? |

|

A (Ms Curry) |

No, I am not sure that I do. I think in the first instance what you are talking about is the time period over which you would quantify a SSNIP calculation. I think when Ofcom was looking at migration, it was looking at the number of users over the period covered by this review who would be choosing between 1G and 10G and whose decision would therefore be affected by the relative prices of those services. Ofcom did not, as we know, do a quantified SSNIP calculation. I think it was appropriate when considering migration for Ofcom to look at the three-year period covered by this review because it is required to adopt a forward-looking review and to adopt a market definition that is relevant for the whole period covered by this review. Even within the context of a quantified SSNIP calculation, whilst I can see that the OFT suggests it is a rough rule of thumb that a year might be appropriate, I can also see that in this specific industry there may be reasons to adopt a longer time period. |

|

Q (Mr Beard) |

Does the final statement indicate what time period was being used? |

|

A (Ms Curry) |

No. Ofcom did not conduct a quantified SSNIP calculation, so that was not a relevant consideration. It was clear that it was looking at migration over the period covered by this review, and I think that was the appropriate time period for Ofcom to look at. |

|

Q (Mr Beard) |

Does that effectively mean that the final statement should be read as treating the relevant period as being three years? |

|

A (Ms Curry) |

The relevant period for what? |

|

Q (Mr Beard) |

Any relevant switching for the assessment of a SSNIP test? |

|

A (Ms Curry) |

I do not think necessarily. It was not a question that Ofcom considered, the exact time frame that would be relevant to a quantified SSNIP test, because it did not conduct one. It did look at substitutability between 1G and 10G over the period as a whole and it was relevant to do so given the time period covered by this review. |

|

Q (Professor Cubbin) |

I am sorry, I am not clear. Are you saying that it is only where you do a quantified SSNIP test that you need even consider what the relevant period should be? |

|

A (Ms Curry) |

I think you would need to consider that substitution would be sufficiently timely so as to affect the pricing decision of a hypothetical monopolist. We have seen evidence that BT was taking into account the substitution from 1G to 10G when setting the price of its 10G service. So I think that evidence strongly suggests that the time period over which substitution was likely to occur would be a sufficient constraint [sic]. I am saying that I do not think Ofcom needed to consider it in more detail than that.[11] |

99. A similar point can be made in relation to Ms. Curry’s evidence concerning the design of the Boundary Test and its orgins in the BCMR 2008 to which reference is made in paragraphs 406ff below.

100. As a consequence, we approach Ms. Curry’s expert evidence with a degree of caution.

Virgin Media

101. Mr Chris Osborne. Mr Osborne is an economist and is the Global Segment Leader of FTI Consulting’s Economic Consulting segment. Mr Osborne provided a single expert report which focussed solely on the question of geographic market definition. Mr Osborne gave clear, crisp evidence, making sensible concessions where appropriate. We found him to be a helpful and straightforward witness.

(3) Remarks on the evidence in this appeal

102. Having set out our brief impressions of the witnesses, we wish to place on record two general points regarding the evidence.

103. The first is that we were not remotely assisted by the length and tone of much of the written evidence and expert reports with which we were assailed. Whilst we appreciate that Ofcom’s Final Statement was itself a vast document, and the issues with which it deals are complex, we thought that much of the written material, in particular from BT, was excessively prolix and argumentative. At times, that written material also sought to reopen old (and irrelevant) battles. This style of written statement inevitably tended to obscure rather than enlighten, and led to cross-examination which strayed into argument.

104. In saying this, we appreciate that the regulatory environment of the BCMR cycle is very different from the situation that prevails in ordinary commercial litigation. The questions to be answered necessarily concern looking into the future rather than simply looking at events that have happened in the past. Moreover, the personnel who give evidence are very likely to have been closely involved on behalf of their employer over several cycles of consultation and the litigation that appears inevitably to follow a regulatory decision in the telecommunications field. This may make it very difficult for such witnesses to distinguish between the submissions that they have been involved in preparing or receiving during the BCMR process, and the relevant factual evidence that they have to give on an appeal.

105. That said, in principle there should be no difference in the content of witness statements of fact used in the Tribunal proceedings and those used in ordinary commercial litigation. Such statements should in general only contain evidence that the witness would be allowed to give orally, and witnesses should not engage in matters of argument: see JD Wetherspoon plc v Harris [2013] 1 WLR 3296 and words to similar effect at paragraph 7.61 of The Tribunal’s Guide to Proceedings 2015.

106. The second point arises from the comments which we have made regarding the evidence of Dr. Basalisco and Ms. Curry. As Cresswell J made clear in The Ikarian Reefer [1993] 2 Loyds Rep 68 at 81-82, an expert witness in civil proceedings should provide independent assistance to the court by way of objective unbiased opinion in relation to matters within his or her expertise, and should never assume the role of an advocate.

107. Those requirements are reflected in paragraph 11 of CPR Practice Direction 35, which states:

“Experts must provide opinions that are independent, regardless of the pressures of litigation. A useful test of ‘independence’ is that the expert would express the same opinion if given the same instructions by another party. Experts should not take it upon themselves to promote the point of view of the party instructing them or engage in the role of advocates.”

108. To similar effect is paragraph 7.67 in The Tribunal’s Guide to Proceedings 2015, which states:

“[…] Expert evidence presented to the Tribunal should be, and should be seen to be, the independent product of the expert uninfluenced by the pressures of the proceedings. An expert witness should never assume the role of an advocate […].”