Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Scottish Law Commission (Reports)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Scottish Law Commission >> Scottish Law Commission (Reports) >> Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 [2019] SLC 254 (April 2019)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/scot/other/SLC/Report/2019/254.html

Cite as: [2019] SLC 254

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION

Report on Section 53 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003

Report on a reference under section 3(1)(e) of the Law Commissions Act 1965

Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers

April 2019

SCOT LAW COM No 254

SG/2019/54

The Scottish Law Commission was set up by section 2 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 (as amended) for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law of Scotland. The Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lady Paton, Chair

Kate Dowdalls QC

Caroline S Drummond

David Johnston QC

Dr Andrew J M Steven.

The Chief Executive of the Commission is Malcolm McMillan. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR.

Tel: 0131 668 2131

Email: info@scotlawcom.gsi.gov.uk

Or via our website at https://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/contact-us/

NOTES

1. Please note that all hyperlinks in this document were checked for accuracy at the time of final draft.

2. If you have any difficulty in reading this document, please contact us and we will do our best to assist. You may wish to note that the pdf version of this document available on our website has been tagged for accessibility.

3. © Crown copyright 2019

You may re-use this publication (excluding logos and any photographs) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 ; or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU; or email psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available on our website at https://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/ .

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at info@scotlawcom.gsi.gov.uk .

ISBN:………………….

Produced for the Scottish Law Commission by APS Group Scotland, 21 Tennant Street, Edinburgh EH6 5NA.

SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION

Report on a reference under section 3(1)(e) of the Law Commissions Act 1965

Report on Section 53 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003

To : Humza Yousaf MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Justice

We have the honour to submit to the Scottish Ministers our Report on Section 53 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003.

(Signed) ANN PATON, Chair

CATHERINE DOWDALLS

C S DRUMMOND

DAVID JOHNSTON

ANDREW J M STEVEN

Malcolm McMillan, Chief Executive

25 March 2019

Structure and content of the Report 3

Legislative competence and human rights . 3

Scottish Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement 3

Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment (BRIA) 4

Chapter 2 Current law: overview and assessment 6

Implied rights to enforce real burdens . 6

Implied enforcement rights in common schemes: introduction . 7

Scottish Executive Consultation Paper 11

Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill 11

The Scottish Executive response . 12

Deed registered before the appointed day . 14

What section 53 does not require . 19

(3) Lack of publicity on the burdened property’s title . 21

Chapter 3 A replacement provision . 24

General policy: should section 53 be repealed and not replaced? . 24

General policy: an identifiable community . 24

Implementing policy: a unitary provision . 27

A requirement for there to be a “community” 33

Rule 1: flats in the same tenement 34

Rule 2: properties subject to common management provisions . 35

Rule 3: properties subject to burdens imposed in the same deed . 36

Rule 4: shared common property . 37

Post-28 November 2004 sub-divisions . 42

Chapter 4 A preservation scheme . 44

Proportionality: fair balance . 46

The need for and general principles of a preservation scheme: consultation . 48

Chapter 5 List of recommendations . 53

List of Respondents and Advisory Group Members . 67

2003 Act

Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003

CMS

CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang LLP

Discussion Paper

Discussion Paper on Section 53 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 (Scot Law Com DP No 164, 2018), [2018] SLC 164 (DP)

Discussion Paper on Real Burdens

Scottish Law Commission, Discussion Paper on Real Burdens (Scot Law Com DP No 106, 1998), [1998] SLC 106 (DP)

Gretton and Reid, Conveyancing

G L Gretton and K G C Reid, Conveyancing (5 th edn, 2018)

Gretton and Steven, Property, Trusts and Succession

G L Gretton and A J M Steven, Property, Trusts and Succession (3 rd edn, 2017)

Hislop

Hislop v MacRitchie’s Trs (1881) 8 R (HL) 95, [1881] UKHL 571

Justice Committee Report

Scottish Parliament Justice Committee, 8 th Report, 2013 (Session 4) Inquiry into the effectiveness of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 , available at http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/CurrentCommittees/59247.aspx

McDonald, Conveyancing Manual

D A Brand, A J M Steven and S Wortley, Professor McDonald’s Conveyancing Manual (7 th edn, 2004)

O’Neill Survey

B O’Neill, Title Conditions Survey (2016)

Reid, “New Enforcers for Old Burdens”

K G C Reid, “New Enforcers for Old Burdens: Sections 52 and 53 Revisited” in R Rennie (ed), The Promised Land: Property Law Reform (2008) 71-90

Reid, Property

K G C Reid, The Law of Property in Scotland (1996)

Reid, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure

K G C Reid, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure in Scotland (2003)

Rennie, Land Tenure

R Rennie, Land Tenure in Scotland (2004)

Report on Real Burdens

Scottish Law Commission, Report on Real Burdens (Scot Law Com No 181, 2000)

Steven, “Implied Enforcement Rights”

A J M Steven, “Implied Enforcement Rights in relation to Real Burdens in terms of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003” 2003 Scottish Law Gazette 146

Wortley, “Love Thy Neighbour”

S Wortley, “Love Thy Neighbour: The Development of the Scottish Law of Implied Third-Party Rights of Enforcement of Real Burdens” 2005 Juridical Review 345

Amenity burden A real burden which protects amenity such as by forbidding building or non-residential use.

Benefited property A property which benefits from a real burden. Its owner and certain other parties, such as a tenant of that property, can enforce the burden. See the 2003 Act s 1(2)(b).

Burdened property A property which is affected by a real burden. See the 2003 Act s 1(2)(a).

Common scheme A set of real burdens which are identical or similar and affect a group of properties. The term is found in the 2003 Act ss 52 and 53, but is undefined.

Community burden A real burden which regulates a group or “community” of properties and is mutually enforceable by the owners of the properties in the community. See the 2003 Act s 25.

Deed of conditions A document imposing title conditions against a group of properties, such as a tenement or housing development or industrial estate.

Facility burden A real burden which regulates a common facility. See the 2003 Act s 56. A list giving examples of facilities is provided by the 2003 Act s 122(3) and includes a common area for recreation, a private road and a boundary wall.

Feudal superior The holder of a superiority interest in land under the feudal system, which was abolished on 28 November 2004.

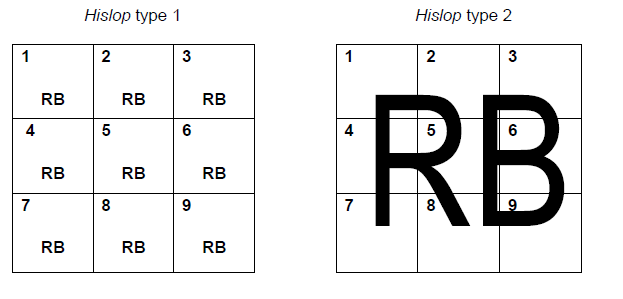

Hislop type 1 Where real burdens have been imposed in successive deeds and the grantees have implied enforcement rights. This is the first of the two scenarios identified by Lord Watson in Hislop v MacRitchie’s Trustees (1881) 8 R (HL) 95. It can also be referred to as the “external enforcement” case as it is necessary to look at deeds other than the deed affecting the relevant property, to see if there is a common scheme.

Hislop type 2 Where real burdens have been imposed in a single deed and the land is subsequently sub-divided, conferring implied enforcement rights on the grantees. This is the second scenario identified by Lord Watson in the Hislop case. It can also be referred to as the “internal enforcement” case as only the one deed needs to be considered.

Notice of common scheme A requirement under the 2003 Act s 52 and the common law for there to be implied rights to enforce under a common scheme. The main examples of notice are that the deed imposing the burdens (i) affects both the property whose owner wants to enforce and the property against which enforcement is sought; or (ii) contains an obligation on the granter to impose burdens in future grants in the same development.

Real burden A perpetual obligation affecting land, usually of a positive or negative character, which can be enforced by neighbouring landowners.

Related properties A term found in the 2003 Act s 53 which refers to certain units of land affected by real burdens. “Related” is to be “inferred from all the circumstances” and a non-exhaustive list of examples is given.

Service burden A real burden which requires the provision of a service such as electricity. See the 2003 Act s 56.

Title and interest to enforce A real burden can only be enforced by someone with both title and interest. See the 2003 Act s 8. Title is a general concept essentially tied to ownership of a benefited property, whereas interest relates to the breach (or anticipated breach) in question.

Title condition A general term for obligations affecting land which can be varied or extinguished by the Lands Tribunal, such as real burdens. See the 2003 Act s 122(1).

1.1 On 31 August 2013 we received a reference [1] from the then Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs, Roseanna Cunningham MSP:

“To review section 53 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 in the context of part 4 of that Act and make any appropriate recommendations for reform.”

1.2 The reference followed a recommendation by the Justice Committee of the Scottish Parliament in its Inquiry into the effectiveness of the provisions of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 (2013) that the matter be remitted to us. [2] It was this Commission which was responsible for the draft Bill on which the 2003 Act is based. [3] But what is now section 53 was a new provision added by the then Scottish Executive, [4] during the Parliamentary passage of the Bill.

1.3 The 2003 Act codified the Scottish law of real burdens. It was part of a package of legislation which abolished the feudal system and modernised Scottish land law. [5] It deals mainly with real burdens. These are obligations affecting land, such as to maintain a boundary wall or not to carry out any further building. They can burden any type of land, including that which is residential or commercial. [6] In principle real burdens are perpetual and thus “run with the land”, although there are a number of ways in which they can be extinguished (ie removed). [7] The land affected by real burdens is known as the “burdened property” and the land whose owner is entitled to enforce the burdens is known as the “benefited property”. At common law there were strict requirements for the burdened property to be identified and for the real burdens to be registered against that property. But conversely there was no requirement to identify the benefited property (or properties). The courts were willing to imply benefited properties, provided that certain conditions were met. [8]

1.4 The 2003 Act reformed the law so that to create real burdens since 28 November 2004 it is usually necessary to identify both the benefited and burdened properties and to register the burdens against the title to both. [9] For real burdens created before that date, Part 4 of the 2003 Act abolished the common law rules on implied enforcement rights and replaced these with a set of statutory rules. Section 53 is the most important of these rules. It concerns the situation where there is a “common scheme” of burdens affecting “related properties”. The provision does not define “common scheme” and provides that whether properties are “related” is to be “inferred from all the circumstances”. [10] A non-exhaustive list of examples is given, including flats in the same tenement and properties subject to the same deed of conditions.

1.5 Section 53 has been the subject of significant criticism, principally directed at its uncertainty. For example, the Law Society of Scotland in its response to our Discussion Paper stated: “The lack of clarity . . . in relation to the application of section 53 is undesirable and increases . . . costs.” Dentons said:

“English clients sometimes struggle to understand why the situation is not as clear as it would be south of the border and consequently we feel that the current uncertainty might make it less attractive to buy property in Scotland.”

1.6 Professors Reid and Gretton have described the provision as “fatally unclear”. [11]

1.7 In May 2018 we published our Discussion Paper, containing provisional proposals and questions. We concluded that section 53 was defective and proposed that it should be replaced with a new provision that would implement its policy aim more clearly and effectively. We identified that policy aim as being that the owners of properties within an identifiable community should have the implied right to enforce a common scheme of burdens affecting that community against each other. Consultees were asked to confirm whether they agreed with that policy. The Discussion Paper then proposed a set of provisional rules which would govern whether such a community existed, such as where the properties were flats in the same tenement. These hard and fast rules would replace the list of examples in section 53(2). We asked consultees also whether there should be a residual rule based on proximity. The other main issue covered by the Discussion Paper was a preservation scheme to allow any owner who would lose rights of enforcement under our proposals to maintain these by means of registration of a notice. We were influenced here by previous reforms such as those made by the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Act 2000 and the need to ensure that our proposals were compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

1.8 Consultation ran for three months, until the end of August 2018. During that period the project team delivered seminars on the Discussion Paper to many of the large Scottish law firms where property lawyers regularly have to attempt to apply section 53 in practice. In addition, we attended meetings of the Edinburgh Conveyancers Forum, RICS Residential Property Board and the Scottish Factoring Network to speak on the project. We eventually received 34 responses to the Discussion Paper.

1.9 These responses were analysed and policy recommendations decided on. This allowed us to prepare our draft Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill which, if enacted, would amend the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 to give effect to our recommendations. We carried out a short technical consultation on that draft Bill in early 2019. We received 19 responses to that consultation and the helpful comments of consultees led to some refinements.

Structure and content of the Report

1.10 This Report is divided into five chapters. This chapter considers introductory matters. Chapter 2 gives a brief account of the background to section 53, followed by an assessment of the difficulties which it is causing in the property sector. Chapter 3 makes recommendations as to how it should be replaced, together with some clarification of related matters. Chapter 4 sets out recommendations in relation to a preservation scheme to ensure that the reforms would be compatible with Article 1 Protocol 1 to the ECHR. Chapter 5 lists our recommendations.

1.11 There are two appendices. Appendix 1 contains the draft Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill. Appendix 2 lists (a) those who responded to our Discussion Paper; (b) those who responded to our draft Bill consultation; and (c) the members of our advisory group.

Legislative competence and human rights

1.12 The 2003 Act is an Act of the Scottish Parliament and deals with land law, which is not a reserved matter. In particular, it does not appear in the list of reservations in Part II of Schedule 5 to the Scotland Act 1998 (specific reservations). It is indeed an aspect of Scots private law. [12]

1.13 An Act of the Scottish Parliament is not law in so far as any provision of the Act is outside the legislative competence of the Parliament and a provision is outside that competence in so far as it is incompatible with any right under the ECHR. [13] In a land law context, Article 1 Protocol 1 to the ECHR is particularly important as it protects property rights. As will be seen later, [14] this was a relevant factor in the Scottish Executive departing from the scheme for implied rights recommended in our Report on Real Burdens and bringing forward an alternative approach including section 53. In recommending possible reforms we need to ensure that these would be ECHR-compliant. We deal with this matter in Chapter 4 where, as noted above, we recommend a preservation scheme.

Scottish Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement

1.14 In preparing this Report we have taken account of the Scottish Government’s Scottish Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement, which was published in 2017, under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016. [15] Part of Principle 5 of the Statement is that there “should be improved transparency of information about the ownership, use and management of land”. We consider that the effect of our recommendations if implemented would be to provide greater transparency as to whether land owners have implied rights to enforce real burdens against other land owners. This is because the law in this area would become much more certain.

Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment (BRIA)

1.15 In line with the Scottish Government’s requirements for regulatory impact assessments of proposed legislation, [16] we have prepared a BRIA in relation to our recommendations. In the Discussion Paper we noted that the Justice Committee in 2013 received representations from several stakeholders that the current law resulted in increased costs. [17] This might be because copies of the titles of properties which may have enforcement rights under section 53 require to be obtained and assessed. Since section 53 is so opaque, owners may in some cases be advised by their lawyers to approach the Lands Tribunal for a ruling on the enforceability of a burden. [18] They might be advised too to pay for an expert opinion (from Counsel (an advocate) or a professor) or for title insurance.

1.16 We asked consultees for information or data on the economic impact of section 53 and of the reforms proposed. We are grateful for their responses. These very much reinforced the evidence which the Justice Committee received. For example, Dentons informed us of a case where a developer paid £19,000 for a title indemnity policy against the risk of burdens being enforced under section 53. A member of our advisory group, Bernadette O’Neill, told us that when she carried out her survey of solicitors mentioned below [19] she was advised of a case where a client had spent £20,000 in establishing that section 53 gave it title to enforce.

1.17 DLA Piper Scotland said: “The potential economic impact of any reform which clarifies the law will be positive for the real estate sector [and] should have the effect of increasing investor confidence.” Gillespie Macandrew stated: “The reforms proposed will lead to more clarity and as such will allow practitioners to advise their clients more efficiently and effectively. This will … mean genuine savings for the client.”

1.18 These comments and others have allowed us to prepare the BRIA which is available on our website. Its main points are:

· Section 53 is causing significant difficulty in practice. Its uncertainty affects development and property investment in Scotland.

· There is strong support for replacing the provision with an improved version.

· If implemented, our recommendations would reduce the costs of many property transactions.

· The recommendations would clarify the law in relation to implied rights to enforce real burdens, encouraging people and businesses to develop land in confidence.

1.19 As all Bills introduced in the Scottish Parliament require an accompanying BRIA there is likely to be a need to update our version when a Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill is brought forward. It will be examined as part of the Parliamentary process, especially at Stage 1. We would encourage all those who may be affected by the reforms, or otherwise with an interest in them, to consider engaging with that process at the appropriate time in the future.

1.20 We are grateful to the members of our advisory group, whose names are listed in Appendix B. We thank particularly Bernadette O’Neill of the University of Glasgow for providing us with the results of her Title Conditions Survey. This involved issuing a questionnaire to solicitors in 2016, which attracted 100 responses. We acknowledge also the assistance from Professor Kenneth Reid of the University of Edinburgh in relation to the preparation of our draft Bill. Finally, we thank Jennifer Henderson, the Keeper of the Registers of Scotland, and her staff for their assistance in relation to our recommendations in respect of a preservation scheme. [20]

Chapter 2 Current law: overview and assessment

2.1 In the Discussion Paper we gave a detailed account of the common law background to section 53; [21] our previous project on real burdens; [22] the passage of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill, during which the provision which became section 53 was first introduced; [23] and an assessment of that provision. [24] What follows here is an abbreviated version. We have also taken account of the views of consultees in the part of this chapter assessing section 53.

Implied rights to enforce real burdens

2.2 The growing urbanisation of Scotland from the late eighteenth century brought with it the need to develop a mechanism which regulated building projects and future use of land. [25] Public law controls, such as planning and building laws, came much later, in the mid-twentieth century. Servitudes, brought into Scots law from Roman law, could not play this regulatory role as they are unable to impose positive obligations and always require neighbouring land. And mere contractual obligations could not bind third parties such as successor owners. Conveyancers were inventive and began to impose conditions when land was feued (under the now-abolished feudal system) or disponed. These conditions became known as real burdens and their validity was accepted by the courts. [26]

2.3 Real burdens required to have a benefited property and a burdened property. As to the burdened property, the courts required precise identification. [27] But, as regards the benefited property, the courts were considerably more generous. There was no requirement to identify that property, because it was possible to imply one. There were three broad categories where a benefited property or properties would be implied by the courts. [28]

2.4 The first category arose where there was a feudal conveyance. Where land was the subject of such a conveyance and it imposed real burdens, the feudal superiority was deemed to be the benefited property.

2.5 The second category arose where there was a non-feudal conveyance. If the disponer retained land in the neighbourhood then that land was deemed to be the benefited property. The leading case was J A Mactaggart & Co v Harrower . [29]

2.6 The third category related to neighbouring owners whose properties were subject to the same or similar burdens imposed under feudal or non-feudal conveyances. In other words, where there was some form of common scheme the owners of properties subject to the scheme could enforce. This was the most complex and, for present purposes, the most relevant category.

Implied enforcement rights in common schemes: introduction

2.7 The leading case on common-scheme enforcement rights under the common law is Hislop v MacRitchie’s Trs , [1881] UKHL 571, [30] which was decided in 1881. The account of the law given there was developed in subsequent cases. [31] Hislop involved two properties in Gayfield Square in Edinburgh. The owner of one property unsuccessfully attempted to enforce real burdens in the title of the other to stop building work. The burdens had been imposed by the superior, who was not a party to the action. In the House of Lords, Lord Watson stated that implied rights in favour of third parties could arise in the following two cases:

“(1) where the superior feus out his land in separate lots for the erection of houses, in streets, or squares, upon a uniform plan; or (2) where the superior feus out a considerable area with a view to its being subdivided and built upon, without prescribing any definite plan, but imposing certain general restrictions which the feuar is taken bound to insert in all sub-feus or dispositions granted by him.” [32]

2.8 The two identified cases can be set out in diagram form. [33]

2.9 It can be seen in the first case that the real burdens are imposed in separate deeds, whereas in the second case the one deed imposes them. These two cases have traditionally been referred to as Hislop type 1 and Hislop type 2. [34] More recently, Professor Kenneth Reid has suggested moving on from Lord Watson’s analysis and drawing a distinction between “internal enforcement” (case 2, where the properties are burdened by the same deed) and “external enforcement” (case 1, where the properties are burdened by different deeds). [35] He points out that Lord Watson’s division does not take account of deeds of conditions, which were in their infancy in 1881 but in more modern times are very common.

2.10 While the statement made by Lord Watson was in feudal language, it became settled that the same principles applied where the burdens were imposed in a non-feudal conveyance or conveyances. [36]

2.11 Hislop and subsequent cases set out a number of criteria which required to be satisfied before implied enforcement rights in favour of third-party owners would be recognised under the common law. [37] First, the burdens had to be imposed by a common author , that is to say either the same superior or disponer.

2.12 Secondly, the property owned by the party seeking to enforce (the would-be benefited property) required to be subject to the same or similar burdens as the burdened property. The properties had to be the subject of a planned common scheme . The burdens did not have to be identical but there had to be a sufficient degree of equivalence or similarity. That degree was found not to be satisfied in Hislop itself where although both properties had building restrictions they lacked commonality. Lord Watson said that “it is essential that the conditions to be enforced ... shall in all cases be similar, if not identical”. [38]

2.13 Thirdly, there required to be notice of the common scheme in the title of the burdened property. It was not enough that the burdens affecting it and the property of the party seeking to enforce were the same. [39] That said, where the burdens were imposed by the same deed, the notice requirement was automatically satisfied because it could be seen by inspecting the title of the burdened property that the real burdens affected a wider area. Where, however, the burdens were imposed in separate deeds, there were two established ways of giving notice. One was an obligation by the granter to impose the same or equivalent burdens in future grants in the same development. [40] The other was a reference to a common plan for the development. [41]

2.14 The final requirement was a negative one. There had to be nothing in the deed creating the burdens which excluded implied enforcement rights arising. The classic example of this was the granter reserving the right to vary or waive the burdens. [42] Another possibility, in the case where the deed was over a wider area, was a prohibition on the land being sub-divided. [43]

2.15 The feudal system, which provided the structural basis of Scottish land law, was progressively dismantled over time. [44] This Commission was tasked with preparing the way for final feudal abolition. Our Report on the Abolition of the Feudal System, and the draft Bill appended to that Report, formed the basis of the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Act 2000. [45] It came fully into force on 28 November 2004, the “appointed day” on which the feudal system was abolished. Superiorities and superiors’ rights to enforce real burdens were abolished on that day. [46] The first category of implied enforcement rights referred to above [47] was therefore consigned to history. Prior to the appointed day, however, it was possible for superiors in limited cases to preserve their enforcement rights by “reallotting” the real burden to neighbouring land which they owned or by converting the burden into a personal real burden. [48] To do this it was necessary to register [49] a preservation notice and thus the right to enforce became patent on the register. Very few preservation notices were registered.

2.16 It became apparent to this Commission when working on feudal abolition that the law of real burdens in general required reform. [50] Consequently a separate, albeit related, project on real burdens commenced. We issued a Discussion Paper in 1998 and a Report in 2000. [51] We made numerous criticisms of the common law, including that it was over-reliant on implied rights, it was difficult to operate and it was uncertain. [52] For the future we recommended that it should be mandatory to specify the benefited property and for the deed creating the real burdens to be registered against the title to that property. [53] These recommendations drew widespread support and have now been enacted in section 4 of the 2003 Act.

2.17 We found the question of reform of existing implied rights a difficult one and the recommendations which we made in the Report differed to some extent from the proposals which we made in the Discussion Paper. We recommended abolition of implied rights with some savings. One recommended saving was for burdens regulating the maintenance and use of common facilities, such as shared amenity ground, a private water system or the common parts of a tenement. We recommended that such burdens should become enforceable following the appointed day by those whose property is benefited by the facility. [54] This recommendation was implemented by section 56 of the 2003 Act. We made a similar recommendation in relation to burdens requiring the provision of a service, although such burdens are rare in practice. [55] For the situation where land retained in the neighbourhood by the granter was implied to be the benefited property, [56] we recommended a preservation scheme requiring the registration of the right of enforcement. [57] This recommendation was implemented by section 50 of the 2003 Act.

2.18 For burdens imposed under common schemes dealing with amenity, such as prohibitions on development, we proposed originally a preservation scheme once again, but we changed approach following opposition from consultees. Empirical research which we commissioned influenced us to recommend a rule based on planning law notification. [58] Only owners within four metres (disregarding roads which are 20 metres or narrower in width) would have implied rights to enforce. They would only have these if the common law requirements [59] for the deed imposing the burdens – in particular notice of a common scheme and nothing to negative the implication of third-party enforcement rights – were satisfied. But the common law requirement that the burdens were imposed by the same author would be dropped on the basis that a housing development may be completed by another developer. [60] Apart from that, the recommendation was to codify Hislop , [61] but with the four-metre distance limitation. This could be termed a “ Hislop four-metre rule”. It would not be restricted to amenity burdens: a burden which could qualify as a facility burden or a service burden would be included too. [62]

2.19 We considered whether, given pending feudal abolition, the Hislop four-metre rule was too restrictive. [63] We recommended ultimately that two cases merited special treatment. The first was tenements. A tenement is a very clear example of a community, but individual flats might well be more than four metres apart. The fact that all the flats are in the same tenement should be regarded as sufficient notice of there being a community . Thus we recommended that where burdens have been imposed under a common scheme on all the flats in a tenement, each flat should be a benefited property. [64] The second case was sheltered housing complexes. These are another clear case of a community. We recommended that where real burdens have been imposed under a common scheme on all the units in a sheltered housing development (or on all units other than one which is used in a special way, such as a warden’s flat) each unit should be a benefited property. [65]

Scottish Executive Consultation Paper

2.20 The Scottish Executive subsequently published its consultation paper on the draft Bill appended to our Report on Real Burdens. [66] Chapter 4 of that paper dealt with implied rights of enforcement. In relation to the Hislop four-metre rule, the Executive was concerned that this was too restrictive. But its concerns ran wider. Under the feudal law it was possible for the superior to enforce burdens. Housing developments were often regulated by feudal burdens with the developer retaining the superiority. Similarly, feudal conveyancing was also used when local authority housing was sold under the right-to-buy legislation. Commonly, the developer (or, in right-to-buy cases, the local authority) had reserved the right to vary the burdens and thus there were no implied rights in favour of the householders under Hislop. [67] With feudal abolition, the result of our recommendation for amenity burdens would be that these would be extinguished, except in the cases of tenements and sheltered housing developments.

2.21 The Executive asked whether neighbours in other common schemes should be able to enforce amenity burdens even although they could not at common law. It then suggested that consultees should try to imagine three types of modern housing estate. The first is where there are express enforcement rights in favour of all the owners. The second is where there are implied enforcement rights under Hislop and in respect of which we proposed a four-metre rule. The third is where the developer was the superior, who had reserved the right to vary the burdens meaning that there were no implied enforcement rights in favour of the house owners. The paper asked whether the schemes should be treated differently. [68] A large majority of respondents to the consultation paper was opposed to the proposed different treatment of the three common schemes. [69] Consequently the subsequent Bill took a far wider approach to implied enforcement rights than we had recommended. A further reason for this approach was concerns that the Hislop four-metre rule might not be ECHR-compatible. [70]

Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill

2.22 The Scottish Executive introduced the Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill in the Scottish Parliament in 2002. The Bill’s policy for burdens in common schemes was to treat the three types of cases outlined in the consultation paper identically, following the views expressed by consultees. Thus, in cases where there were no express enforcement rights, all that was required was notice of the common scheme within the titles. Typically that notice would be supplied by there being a deed of conditions over the development as a whole. A reserved power of the developer to vary the burdens made no difference. [71]

2.23 Stage 1 of the Bill took place in the Justice 1 Committee. It heard oral evidence at four meetings and received a considerable amount of written evidence, before completing its Report. [72] Three of its recommendations merit mention.

2.24 First, given the policy that common schemes were to be treated alike, the meaning of the term “common scheme” as used in the Bill was clearly very important:

“Accordingly, the Committee recommends that there should be a clear definition of the term in the Bill given that it underpins substantial parts of the Bill and appears open to confusion at the moment.” [73]

2.25 The Committee referred also to evidence from the Confederation of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) and the Society of Local Authority Solicitors and Administrators (SOLAR) that there would be cases of “mixed tenure” [74] housing estates where the policy that there should be enforcement rights was not achieved by the Bill. [75] This was because the Bill, in line with the position under the common law, required notice of the common scheme. If the burdens had been imposed in the individual conveyances of the properties rather than in a deed of conditions this requirement might not be satisfied.

2.26 Secondly, the Committee noted that the result of this policy where a developer had reserved the right to vary the burdens would be that instead of one person (typically the superior) having to be approached for permission to breach a burden, numerous neighbours would now need to give consent. It therefore was of the view that the Scottish Executive’s policy was in some ways too generous as regards implied rights (by having a general disapplication of the rule that a right to vary burdens reserved by the developer precluded such implied rights) and in some ways too restrictive (because the absence of notice of the common scheme would preclude such implied rights and this was unsatisfactory in housing estates).

2.27 Thirdly, the Committee reviewed the provisions on implied rights in the Bill as introduced compared with the Commission’s recommended Hislop four-metre rule. [76] Its conclusion was that it supported the Scottish Executive’s approach.

The Scottish Executive response

2.28 Following the evidence given at Stage 1, the Scottish Executive reconsidered the provisions on implied enforcement rights in relation to common schemes [77] and therefore amended the Bill. The amendments were tabled and agreed to at Stage 2. The result of these was that the Bill now contained in relation to burdens in common schemes:

(a) a provision which was designed to restate the common law as set out in Hislop and successor cases (so that an absence of notice of a common scheme or a reserved right to vary the burdens would preclude implied enforcement rights); and

(b) a provision creating a new rule whereby there would be implied enforcement rights where there was a “common scheme” of “related properties”.

2.29 Provision (a) would subsequently become section 52 of the 2003 Act and provisio n (b) would become section 53.

2.30 We now look at section 53 in detail and assess the criticisms that can be made of it. Its sister provision is section 52, which restates the common law of common-scheme enforcement rights as set out in Hislop and subsequent cases. [78] When assessing section 53 it is important to remember the existence of section 52 too.

2.31 Section 53 provides:

“(1) Where real burdens are imposed under a common scheme, the deed by which they are imposed on any unit comprised within a group of related properties being a deed registered before the appointed day, then all units comprised within that group and subject to the common scheme (whether or not by virtue of a deed registered before the appointed day) shall be benefited properties in relation to the real burdens.

(2) Whether properties are related properties for the purposes of subsection (1) above is to be inferred from all the circumstances; and without prejudice to the generality of this subsection, circumstances giving rise to such an inference might include–

(a) the convenience of managing the properties together because they share–

(i) some common feature; or

(ii) an obligation for common maintenance of some facility;

(b) there being shared ownership of common property;

(c) their being subject to the common scheme by virtue of the same deed of conditions; or

(d) the properties each being a flat in the same tenement.

(3) This section confers no right of pre-emption, redemption or reversion.

(3A) Section 4 of this Act shall apply in relation to any real burden to which subsection (1) above applies as if–

(a) in subsection (2), paragraph (c)(ii);

(b) subsection (4); and

(c) in subsection (5), the words from “and” to the end,

were omitted.

(4) This section is subject to sections 57 and 122(2)(ii) of this Act.”

2.32 The most important parts of section 53 are subsections (1) and (2). These can be analysed in terms of three requirements in relation to the relevant real burdens. First, the burdens must have been imposed in a deed registered before the appointed day. Secondly, the burdens must have been imposed under a “common scheme”. Thirdly, the property on which the burdens have been imposed must be within a group of “related properties”.

Deed registered before the appointed day

2.33 This requirement is straightforward. The real burdens in the scheme must have been first imposed prior to 28 November 2004. As long as one property in the scheme satisfies this requirement then section 53 can apply. For example, a local authority sells properties in a housing scheme to tenants under the right-to-buy legislation. [79] It imposes the same real burdens in each disposition in favour of the purchasers. Provided that at least one of these dispositions was registered before 28 November 2004 then section 53 can operate. This requirement of section 53 was indeed particularly aimed at local authority housing schemes which were in the process of being sold when the legislation came into force. [80]

2.34 We saw earlier that the requirement for a common scheme of real burdens was present under the common law. [81] Where the same deed imposes burdens on multiple properties there is less difficulty than where the burdens are in the break-off deeds for the individual properties.

2.35 In the former case, the burdens will typically be identical. A deed of conditions might have different sets of burdens for different streets in a development but this would not be that usual. [82] A more likely scenario is a deed of conditions relating to a development of flats and houses where there are: (1) flat-specific burdens; (2) house-specific burdens; and (3) general burdens, for example on paying for the maintenance of common grass areas. If there is a burden requiring the flat owners not to leave bicycles in the common stair, it is arguable that the house owners would not be benefited owners because their properties are not subject to this burden. In other words there is a separate common scheme in respect of the flat-specific burdens. The counter-argument is that there is only the one common scheme so all the owners in the development have title to enforce all the burdens. [83] In contrast, in the latter case of the burdens being imposed in separate deeds, these may well not be identical. The respective deeds will have to be checked.

2.36 Despite the call from the Justice 1 Committee, [84] “common scheme” is not defined in the 2003 Act. The Policy Memorandum to the Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill and the explanatory notes to the 2003 Act both say:

“Common schemes exist where there are several burdened properties all subject to the same or similar burdens.” [85]

There is no difficulty with “the same”, but what is less certain is how similar is “similar”. As we saw earlier, [86] the same issue arose at common law. It arises too with regard to section 52 of the 2003 Act where the expression “common scheme” also appears without definition. Burdens which are randomly the same or similar, such as where a conveyancer has simply used the same style for two nearby developments, will not constitute a common scheme. [87] The commonality has to be planned when the burdens are imposed and not arise by chance. [88]

2.37 The case law in relation to “common scheme” and section 53 more generally has been slight. [89] Russel Properties (Europe) Ltd v Dundas Heritable Ltd [90] is the only Court of Session case in relation to section 53 of which we are aware. It was an Outer House decision of Lord Woolman and concerned the Westwood Neighbourhood Centre in East Kilbride. This is a mixed development of flats, offices and shops. The various units were subject to use burdens of varying description and Lord Woolman held on the facts that there was insufficient similarity for there to be a common scheme. The case was decided at the stage of interim interdict. Therefore all the issues may not have been fully canvassed. Professors Reid and Gretton state that, while accepting that Lord Woolman’s view was “tenable, our inclination is to say that, on the information available to us, there was indeed a common scheme.” [91] They say that it would not be possible to reach a definitive view without considering the burdens in the respective titles as a whole rather than only comparing the burdens on use, because in a mixed estate these will inevitably be different. [92]

2.38 In Thomson’s Exr, Applicant [93] plots of land in Old Humbie Road in Newton Mearns had been sold by means of feu dispositions between 1958 and 1960. The deeds each contained real burdens. The Lands Tribunal was asked to determine whether the burdens imposed on 9 Old Humbie Road were enforceable under sections 52 and 53 of the 2003 Act. [94] In its judgment it noted that there was no statutory definition of “common scheme”, but said that it “would suppose that ‘scheme’ suggests some sort of planned or systematic regulation by the superior over a certain area.” [95] It decided that there was a common scheme in relation to the houses despite the real burdens not being identical. In particular, the properties were all subject to burdens requiring the houses built on them to be of a value of at least £2,500. This was held to be a “significant common characteristic, and if not a ‘uniform plan’, at least embodied an intention that the relevant residential area should attain a certain quality of amenity.” [96]

2.39 Since the Discussion Paper was published last year there has been a further Lands Tribunal case: O’Gorman v Love. [97] This involved two adjacent villas in East King Street, Helensburgh. Both had similar real burdens, imposed by the same granter, in feu dispositions dating from the 1860s in relation to the type and location of the houses that could be built. The Tribunal had no hesitation in holding that there was a common scheme.

2.40 For section 53 to apply, the benefited and burdened properties must be “related properties”. This phrase is not defined. It has to be “inferred from all the circumstances”. [98] A non-exhaustive list of examples is provided.

2.41 The policy was explained by Mr Jim Wallace QC MSP, the Deputy First Minister and Minister for Justice at the time of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Bill when what is now section 53 was introduced at Stage 2 as section 48A:

“The purpose of new section 48A is to ensure that amenity burdens in all housing estates or tenements should be mutually enforceable by the owners of houses in the estate or of flats in a tenement. … A large majority of respondents to the consultation on the bill were in favour of such amenity burdens being treated in the same way, irrespective of whether rights had been granted expressly to owners in the original deeds or whether they had arisen by implication under existing law.

We needed to ensure that section 48 [the relevant provision in the Bill as introduced and which in amended form is now section 52] would not confer enforcement rights as between scattered properties in rural areas. [Section 48A] does not require notice of a common scheme, but it retains the need for a common scheme of burdens and introduces a requirement for the properties to be related to one another. For example, houses on a typical housing estate would be related properties. The relationship would be inferred from all the circumstances, but the amendment gives examples of when such inference might arise. …

[S]ubsection (2) of new section 48A gives several examples of circumstances that might give rise to an inference that properties are related properties for the purpose of being treated as a common scheme. One example is of properties that are flats in the same tenement, so section 49 [the provision dedicated to implied enforcement rights in tenements] will no longer be needed, as it will have no independent effect.” [99]

2.42 This has long been assumed to have been a statement made with Pepper v Hart [100] in mind. [101] We understand that it was. [102] It can be seen from Mr Wallace’s statement that the policy of section 53 is for there to be implied enforcement rights in housing estates. The words “housing estate” do not appear in section 53. We understand that this is because an appropriate definition of the term for this purpose could not be found at the time. The difficulties are apparent. For example, it may be difficult to know where one estate stops and a neighbouring estate starts.

2.43 Rather than referring to a “housing estate”, section 53 instead provides a list of examples of where properties are “related”. The list has been the subject of a penetrating analysis by Professor Reid, to which the account here is indebted. [103] The examples can be divided into “legal” and “physical”.

2.44 The first legal example is the convenience of managing the properties together where there is an obligation for common maintenance of a facility such as a private road or water supply. [104] It is not apparent why this is relevant to amenity burdens given that section 56 of the 2003 Act separately deals with implied rights in relation to facility burdens. [105]

2.45 The second legal example is shared ownership of common property. [106] This might perhaps be a recreational or landscaped area in a development which is co-owned by the property owners.

2.46 The third legal example is the properties being subject to the common scheme by virtue of the same deed of conditions. [107] This example is evidently intended to implement the Executive’s policy that there should be implied enforcement rights in housing estates on the basis that such estates, at least modern ones, are typically the subject of a deed of conditions imposed by the builder. But of course this is not always true.

2.47 The more important of the two physical examples is the properties being flats in the same tenement. [108] Indeed this seems more than an example, given the comments of the Justice Minister quoted above [109] to the effect that its presence removed the need for a separate provision dedicated to tenements as there was in the Bill at the time of introduction.

2.48 The other example is the convenience of managing the properties together because they share some common feature. [110] “Feature” seems to mean an aspect of the properties themselves (perhaps the design of the houses) rather than something such as a garden shared by the properties, because the latter is covered by the facility example. [111] But it is difficult generally to see how such features would assist the convenience of the management of the properties. [112]

2.49 A small number of cases have considered the meaning of “related properties”. In Brown v Richardson [113] the Lands Tribunal decided that, where there is a conveyance of a wider area imposing burdens followed by a sub-division (in other words a Hislop type 2 case), the conveyance could be treated in the same way as a deed of conditions to infer that the properties burdened by it were related. The Tribunal took the same approach in Franklin v Lawson . [114]

2.50 Russel Properties (Europe) Ltd , discussed above, [115] involved use restrictions on a mixed estate. Lord Woolman said:

“Although the court has a discretion as to what constitutes related properties, some guidance can be gleaned from the illustrations set out in section 53(2). Russel do not plead that it fits any of these cases. In my view, having regard to the whole circumstances, it has failed to establish an arguable case that the properties are related.” [116]

2.51 It is unknown what “the whole circumstances” were. This aside it is not certain that properties in the same mixed, as opposed to wholly residential, development should not be regarded as “related”. [117]

2.52 In Thomson’s Exr, Applicant , discussed above, [118] the properties were burdened with an obligation to maintain the boundary fence they shared with their immediate neighbour or neighbours. The Tribunal regarded such a fence as a “common feature”, as well as being a “facility” in respect of which there was an obligation to maintain. [119] It noted also that the requirement that the fences should be maintained at joint expense suggested “a certain convenience in managing the properties together”. [120] The fences were also declared to be owned in common by the owners who shared them as a boundary. All these factors are mentioned in section 53(2). The Tribunal therefore concluded that the properties on either side of the common fences were related. This meant only the immediate neighbours. Thus although there was one “common scheme” for the five properties in the road, there were several sub-groups of “related properties”. [121] It may be questioned whether this was the intention of the Scottish Executive when bringing forward section 53. As we saw above, [122] the provision was aimed at conferring title in respect of an entire housing estate, rather than creating multiple micro-communities based on shared boundary obligations.

2.53 The most recent case of O’Gorman v Love , also discussed above, [123] concerned the issue once again of whether a neighbouring house was a “related” property. The facts differed from Thomson’s Exr, Applicant in that the wall separating the properties was not declared to be common property and there was no real burden requiring it to be maintained at joint expense. In fact what the relevant real burdens envisaged was two separate fences on the boundary line, each separately maintained. The Tribunal held that the properties were not “related”. What is most interesting about the decision is the discussion in it about whether the wall could be regarded as a “common feature”. In contrast with Thomson’s Exr, Applicant , the Tribunal analyses more closely the meaning of “the convenience of managing the properties together”. [124] It notes that the properties had no history of being so managed. Further, it considers the Scottish Parliament Official Report in relation to the introduction of what is now section 53 into the then Title Conditions Bill and concludes that the provision is aimed at the management of housing estates, in particular those coming into private ownership under the then right-to-buy legislation. As a result of this decision, the correctness of Thomson’s Exr, Applicant can be increasingly doubted.

What section 53 does not require

2.54 It is worth highlighting three criteria that section 53 does not require. The first is notice of the common scheme. The second is the absence of anything negativing there being implied rights. As we have seen, these were requirements of the common law. [125] They are also requirements of section 52 of the 2003 Act. [126] That provision, as we have noted, [127] codified the common law but the Scottish Executive’s policy was that the common law was too restrictive. Hence there was a need for section 53. Thirdly, the burdens in the common scheme do not have to be imposed by the same author. This was a requirement of the common law but the policy of the 2003 Act further to our Report on Real Burdens was to drop this. [128] This was on the basis that a development may be the work of more than one builder, either jointly or consecutively. [129]

2.55 In the foregoing paragraphs we have attempted to explain section 53 and the case law which has discussed it. We now set out the difficulties relating to the provision, many of which were identified in the evidence to the Justice Committee in 2013.

2.56 It is often impossible to know whether section 53 confers implied rights or does not. [130] In its written evidence to the Justice Committee, DWF Biggart Baillie stated:

“In many cases much time can be spent trying to ascertain whether there is a benefited property with enforcement rights, often involving a time consuming examination of neighbouring titles, only to come to the unsatisfactory conclusion ‘there might be’. For most clients, this is a frustrating, and costly, conclusion.”

2.57 In response to the O’Neill Survey fewer than half of the respondents (49%) said that they felt confident advising clients on questions of implied rights to enforce real burdens. Moreover, only 26% said that the 2003 Act made it easier to find benefited owners who have implied rights to enforce. And only 10% said that it made it less expensive to find the benefited owners who have implied rights to enforce. While these questions were directed at Part 4 of the 2003 Act in general rather than section 53 in particular, section 53 is such an important provision in Part 4 that it must have influenced many of these responses.

2.58 Similar conclusions can be drawn from the views of consultees to our Discussion Paper. For example, Gillespie Macandrew wrote:

“[The process of finding out whether section 53 applies] more often than not . . . ends in a discussion with the client which is not particularly conclusive, and leads to frustration.”

2.59 The uncertainty introduced by section 53 can also be shown by the fact that a provision in the 2003 Act requiring the Keeper to add statements to Land Register title sheets explaining whether there are implied rights was repealed because the task was too difficult and the provision was thus unworkable. [131]

2.60 Much of the problem arises because the provision does not provide bright-line rules, but rather a non-exhaustive list of examples. This contrasts with the common law rules, which were much more certain, albeit the question of whether there was a common scheme was not free from difficulty in the case of similar, rather than identical, burdens.

2.61 There is evidence that section 53 is regarded by many as too complex. The O’Neill Survey asked whether the rules set out in the provision were easy to understand. Only 26% of respondents agreed; 64% disagreed and 10% did not know. In its written evidence to the Justice Committee, MacRoberts said:

“Section 53 is one of the most, if not the most, difficult sections in the Act. … Property law should not be so complicated.”

2.62 In her oral evidence to the Committee, Alison Brynes of T C Young, who was representing the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations, said:

“I find it fairly difficult to understand section 53, but what I find really difficult is explaining it to a client in a way that they can understand. What is a common scheme? What does the phrase “related properties” mean?”

2.63 In their response to our Discussion Paper, DLA Piper Scotland stated:

“Section 53 has proved difficult to apply in practice (for the reasons explained in the Discussion Paper) and this has led, on occasion, to higher transactional costs, including fees for professorial opinions, and title insurance.”

2.64 The issue of complexity to some extent shades into the issue of uncertainty. Section 53 is arguably not that complex: once it is established that a property in the purported common scheme was burdened before 28 November 2004 the provision essentially rests on the twin criteria of “common scheme” and “related properties”. It might even be said to be less complex than section 52 and the common law, which require more criteria to be satisfied. [132]

2.65 Sections 52 and 53 taken together, however, can be argued to be more complex than is necessary. It would seem preferable to have a simpler rule dealing with common schemes.

(3) Lack of publicity on the burdened property’s title

2.66 Under the common law it was possible to determine whether implied rights existed almost entirely from the title of the burdened property alone, ie from within the title in respect of which the owner proposed to breach a burden.

2.67 In Hislop type 2 cases [133] the fact that the relevant deed burdened a wider area meant that the requirements of the same author, identical or similar burdens and notice of a common scheme were immediately satisfied. All that had to be ascertained beyond that was whether there was a negativing factor, but that too could be found in that deed. Where the real burdens were imposed by a deed affecting the relevant property alone (the Hislop type 1 case), it was necessary to look at the neighbouring properties’ titles, but only to check whether the burdens were the same or similar and imposed by the same author. The other requirements, such as notice of a common scheme, were all matters to be determined from within the burdened property’s title. [134]

2.68 In contrast, section 53 requires an assessment of “relatedness” between the burdened owner’s title and those of neighbours. Professor Reid, however, while accepting that criticism based on lack of publicity has force, regards it nonetheless as “exaggerated” [135] on the basis that what amounted to publicity at common law was “often slight”. [136] Furthermore, under section 53 the fact that the property is a flat in a tenement or subject to a deed of conditions provides publicity. But these of course are the easier cases.

2.69 As we have seen, the recommendation in our Report on Real Burdens was to restrict implied enforcement rights in common schemes to neighbours within four metres. [137] But the Scottish Executive was concerned about the loss of rights by further-away owners and our recommendation was not accepted. [138] Instead the common law was codified by section 52 and further rights were conferred by means of section 53. The Executive policy, as we have seen, was for the owner of each property in a housing estate to have title to enforce the burdens against all the other owners. [139]

2.70 Title to enforce is not the only requirement for a party wishing to rely on a real burden. Interest must also be shown. In relation to amenity burdens, section 8(3)(a) of the 2003 Act provides that a person has such interest if:

“in the circumstances of any case, failure to comply with the real burden is resulting in, or will result in, material detriment to the value or enjoyment of the person’s ownership of, or right in, the benefited property”.

2.71 As can be seen, whether there is interest to enforce depends on the facts of the case. Nevertheless, as a general rule, the further the distance between the properties the less likely there is to be interest. [140] For example, in Kettlewell v Turning Point Scotland , [141] the pursuers, who successfully showed interest to enforce a burden to prevent a change of use, were all owners of adjacent or closely neighbouring properties. The requirement of interest influenced our Report on Real Burdens where we recommended the four-metre rule discussed above. [142]

2.72 There seems little value in giving title to enforce to owners whose properties are more distant if they are not going to have interest. [143] Nevertheless, because interest to enforce must always be considered on a fact-specific basis a blanket four-metre limitation would seem on reflection to be too restrictive. For example, in some modern housing developments the individually-owned plots are separated by more than four metres by common landscaped areas. Here there is a readily identifiable community where the owners would expect to be entitled to enforce the burdens affecting it. There may also be cases where the immediate neighbours are unwilling to take action and where it is legitimate to allow neighbours who are further away but within the same comm unity to be entitled to do so.

2.73 The drafting of section 53 has also been criticised. In his oral evidence to the Justice Committee Professor Rennie said that the provision is “almost unintelligible and is very difficult to teach”. [144] This was endorsed by Dr Craig Anderson in his response to the Discussion Paper:

“That has certainly been my experience. This is a point whose importance is often overlooked. I would make two observations. First, today's law students are tomorrow's legal advisers. If their teachers are unable to understand s. 53, it is improbable that they will find it easy to advise properly on it amidst of the pressures of legal practice. Second, if law students, with the advantage of at least some legal education, cannot be made to understand the provision, how are the general public supposed to understand their position?”

2.74 In its response, the Property Litigation Association commented that “section 53 is not particularly well worded”. Brodies mentioned “the vagueness of the drafting”.

2.75 Professor Reid has shown how some of the difficulties arise from section 53 being based on another provision in the 2003 Act – section 66 – which deals with the different subject of manager burdens. [145] But, when he gave evidence at the same session as Professor Rennie, he said that:

“The drafting of section 53 is a little bit unhappy, but that is not the main difficulty. The main difficulty is that section 53 is trying to do something that is almost impossible to do by legislation. By means of a general rule, section 53 tries to provide clarity to title deeds that are extremely varied in type. Although it would help if one recast section 53 and tightened up the drafting, that would not solve the fundamental problem.” [146]

2.76 While some of the foregoing arguments are more persuasive than others, cumulatively they amount to a strong case for reform. There is clear discontent among stakeholders about the current law. This is evidenced not only by the evidence to the Justice Committee in 2013 but also by the responses to our Discussion Paper of 2018.

Chapter 3 A replacement provision

3.1 In this chapter we consider how section 53 of the 2003 Act could be replaced. Our starting point is the identification of what the appropriate general policy should be in relation to implied rights of enforcement in common schemes. We then look at how that policy should best be implemented by means of recommendations which would enable clearer statutory provision to be made.

General policy: should section 53 be repealed and not replaced?

3.2 In the Discussion Paper, [147] we noted that if there is to be reform of section 53, the two broad options are to (1) repeal it without replacement; or (2) replace it. Having reviewed the matter, we concluded that simply repealing section 53 would not be sensible. The result would be to leave section 52 (the provision which codifies the common law on implied rights in common schemes), section 54 (the special rule for sheltered housing) and section 56 (the special rule for facility and service burdens).

3.3 This would mean no special rule for flats in the same tenement. We recommended such a rule in our Report on Real Burdens and the Scottish Executive’s view was that section 53(2)(d) in effect implements that recommendation. [148] It would be unsatisfactory for that rule simply to disappear. We noted also that 36% of the respondents to the O’Neill Survey believed that repealing section 53 would cause problems since it has created new rights on which people may now wish to rely. Only 23% disagreed, with 41% being unsure. The other significant difficulty with a simple repeal is that this could contravene the ECHR meaning that compensation might have to be paid or some form of preservation scheme devised. With one exception, [149] none of the respondents to the Discussion Paper favoured repeal of section 53 without replacement.

General policy: an identifiable community

3.4 In Chapter 2 above we explained the Scottish Executive policy which lay behind section 53. Put shortly, this was that owners of flats within the same tenement or properties within the same housing estate should have title to enforce the burdens affecting that community. In this regard it should not matter whether the right to enforce was (a) expressly conferred by the deed creating the burdens; (b) impliedly conferred by the common law; or (c) not conferred by the common law. Provided that there was an identifiable community, there should be mutual enforcement rights for the owners within it. The Scottish Executive was influenced by the fact that a large majority of respondents to its consultation believed that housing estates should be treated in the same way as regards the burdens regulating them, no matter the conveyancing niceties of the particular case. On the other hand, there should be no implied enforcement rights where there was no identifiable community, such as in the case of scattered rural properties.

3.5 We asked in the Discussion Paper whether that policy should be disturbed in any reform of section 53. Our provisional view was that it should not be. As we saw in Chapter 2, many of the problems identified in relation to the provision concern only the execution of the policy: notably the difficulties of uncertainty and complexity, as well as the criticisms made as to the drafting. It is perhaps unsurprising that these problems exist, given that section 53 was a Stage 2 amendment when the legislation was passing through the Scottish Parliament and was produced at speed.

3.6 We commented that the practice by developers since feudal abolition supports the adherence to the policy behind section 53. Deeds creating real burdens require either to set out expressly the benefited property – or, in the case of community burdens, the community - which has title to enforce. [150] In new housing developments we understand that deeds of conditions are normally used to impose burdens and these provide that all the properties are to be both benefited and burdened. If this is the position as regards developments commenced after 28 November 2004 there is force in the proposition that the same rule should apply as regards older developments. Another advantage of broadly keeping the status quo in policy terms is that it would minimise the human rights consequences of any reform being taken forward.

3.7 We noted that other policy approaches were possible. From the perspective of simplicity there would be an argument in favour of reducing the pre-requisites for implied enforcement rights in common schemes effectively to one. [151] There would have to be a common scheme, no more no less. The other requirements of Hislop and the common law would not apply. Nor would the properties require to be related. Such an approach might be simpler, but it seems unattractive in policy terms. The mere fact that a conveyancer had used the same style when imposing burdens on disparate properties would result in the respective owners having title to enforce against each other, even although there was no connection between the properties. [152] Enforcement rights would significantly be multiplied with little justification and it is not clear therefore that such a policy would be ECHR-compliant.

3.8 Another possibility would be a narrower approach. As we saw in Chapter 2, the policy that everyone in a community should have title to enforce can be regarded as too generous. Given that distant owners are unlikely to have interest to enforce amenity burdens it may be questioned why they should have title. On this view, it should be left to immediate neighbours to take action or not. But there may be cases where distant owners can arguably show interest and should be entitled to take action. We understand also that in “mixed tenure” estates it is often the local authority or housing association which is called upon by owners to take up the matter of the breach of a burden with the relevant owner, even although that authority or association does not have ownership of an immediately-neighbouring house.

3.9 From the perspective of the owner wanting to carry out work in breach of a real burden, the fact that title to enforce is held by all the owners in the estate is qualified by both (a) the need to show interest to enforce; and (b) section 35 of the 2003 Act, which enables a minute of waiver to be obtained from immediate neighbours (albeit owners whose properties are further away can object by means of an application to the Lands Tribunal to preserve the burden). Therefore, in practice the fact that less immediate owners have title to enforce is unlikely to be a barrier to work in many cases.

3.10 We asked consultees whether they agreed with our provisional view that owners of properties within an identifiable “community” should have the implied right to enforce any common scheme of real burdens affecting that community against all the other owners (subject to “community” being appropriately defined).

3.11 There was near unanimous agreement from consultees. Gillespie Macandrew said: “Put simply, given that this is the pattern adopted for developments commenced post-28 November, then there is no obvious reason why this should not be the position pre-28 November 2004.” Sarah King commented: “The problem with the current legislation is in defining the community created by s 53, not the underlying policy.”

3.12 The Faculty of Advocates, while having “no particular objection to such a policy” also said that this “is a policy objective, the identification and specification of which is primarily a matter for the Government and Parliament.” We think that this is true in relation to all the recommendations which we make in our Reports.

3.13 Only one response out of the total of 34 responses to the Discussion Paper rejected the policy based on an identifiable community. This response – which we have been asked to treat as confidential – favoured the abolition of all implied rights to enforce real burdens dealing with amenity, but subject to there being a preservation scheme requiring registration of notices. This was an approach which we considered in our 1998 Discussion Paper but from which we came away because of opposition from consultees. [153] In our 2000 Report we said:

“On reconsideration the disadvantages [of such an approach] loom large. As applied to common scheme burdens, a registration requirement would affect a large number of people, involve considerable trouble and expense, lead to disputes about which properties were and were not to be included in the community, and result in a patchwork of rights preserved and rights extinguished.” [154]

3.14 When we consulted on our draft Bill in early 2019, our confidential respondent once again argued for this approach. MacRoberts and CMS, in contrast to their Discussion Paper responses, now also favoured a policy along these lines. CMS commented that this would improve transparency for land owners, which is an objective of the Scottish Government. [155] In addition, Pinsent Masons expressed a concern at this stage that our draft Bill “creates a lot of implied rights”. We think it is fairer to say that our recommendations perpetuate a lot of implied rights. This is because almost all our Discussion Paper consultees favoured a policy based on an identifiable community and not one of generally abolishing implied rights. While we accept that abolishing implied rights subject to a preservation scheme would much improve transparency, as well as making conveyancing easier, we continue to be persuaded by the arguments which we quote above from our 2000 Report. Such a preservation scheme would be too onerous on ordinary householders in housing developments across Scotland. In human rights terms, it may be regarded as not proportionate. [156] Plainly many owners would not go to the trouble and expense of preserving. The result would be, in contrast to the comment made by Gillespie Macandrew quoted above, [157] a bifurcation between pre and post-28 November 2004 developments. This is undesirable. We continue to be of the view that a policy based on an identifiable community is preferable.

3.15 Finally on this matter, it is worth mentioning, because the point was raised at some of the seminars which we gave on the Discussion Paper, that by “identifiable community” we do not mean a town or a village. Rather, we mean an area which should be regarded as a community in conveyancing terms because the properties within that area are subject to a common scheme of real burdens and there is relatedness between the properties. [158]

3.16 We recommend:

1. Owners of properties within an identifiable “community” should have the implied right to enforce any common scheme of real burdens affecting that community against all the other owners (subject to “community” being appropriately defined).

(Draft Bill, s 1 as inserting a new s 53A into the 2003 Act)

Implementing policy: a unitary provision

3.17 The next matter is how best to implement the appropriate policy and improve what is currently section 53. We noted in the Discussion Paper that our advisory group shared our view that having two separate provisions on implied rights to enforce real burdens in common schemes – sections 52 and 53 – makes Part 4 of the 2003 Act more complex than it needs to be. [159] Neither of these provisions is easy to apply. Our advisory group provisionally agreed that it would be preferable to replace the sections with a consolidated provision clearly expressing an appropriate policy in relation to common schemes. We proposed this in the Discussion Paper.