Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland Chancery Division Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland Chancery Division Decisions >> Fitzpatrick & Anor v Ligoniel Developments Ltd [2020] NICh 16 (01 December 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/nie/cases/NIHC/Ch/2020/16.html

Cite as: [2020] NICh 16

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

Neutral Citation No: [2020] NICh 16

Judgment: approved by the Court for handing down (subject to editorial corrections)* |

Ref: HUM11371

ICOS No: 20/063335/01

Delivered: 01/12/2020 |

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND

___________

CHANCERY DIVISION

___________

BETWEEN:

FRANCESCO DON FITZPATRICK and LUCIA MARIA FITZPATRICK

Plaintiffs

and

LIGONIEL DEVELOPMENTS LIMITED

Defendant

___________

Jacqueline Simpson QC and William Sinton (instructed by Higgins Hollywood Deazley) for the Plaintiffs

Keith Gibson (instructed by Cleaver Fulton Rankin) for the Defendant

___________

HUMPHREYS J

Introduction

[1] This is an application for an interlocutory injunction in respect of allegedly unlawful interference with a right of way enjoyed by the Plaintiffs, who are the owners of land and premises situate at 2 Glenview Avenue, Ligoniel, Belfast.

[2] The Plaintiffs say that their lands benefit from a right of way over and along a laneway to the east of the premises, which laneway is in the ownership of the Defendant company.

[3] As a result of legal submissions made by the Defendant, it became necessary for the Court to make a determination into the existence of the right of way before considering whether there had been substantial interference with any such easement.

[4] The resolution of these two issues would inform the Court as to whether any interlocutory relief should be granted at all and whether the matter should be determined on traditional American Cyanamid principles or on some other basis.

The Right of Way

[5] The Plaintiffs’ root of title is to be found in a Lease from Messrs. George and William Rutledge to Thomas Armstrong dated 1 September 1957. This Lease included in its demise a free right of way and passage over and along the lane leading from Glenside Farm to Wolfhill Avenue. This lane runs along the eastern boundary of the subject premises and affords access to them. The boundary between the premises and the lane was a hedge in which gaps were made to allow pedestrian and vehicular access.

[6] The layout of the area has changed in recent years in that Glenside Farm has been developed, in 2016 the Plaintiffs’ premises were destroyed by fire and the Defendant company has been constructing houses in the area, in phases, over the last 4 years.

[7] It is common case that, during the course of these construction works, the Defendant caused a fence to be erected on the laneway in November 2019. This has been referred to as a ‘temporary’ fence and was the subject of communications between Solicitors acting for the respective parties in late 2019 and early 2020. There was an agreement that this fence could remain in situ although there is a dispute about which other terms may have been agreed around this time. I do not need to make any determination on this dispute for the purposes of this interlocutory hearing.

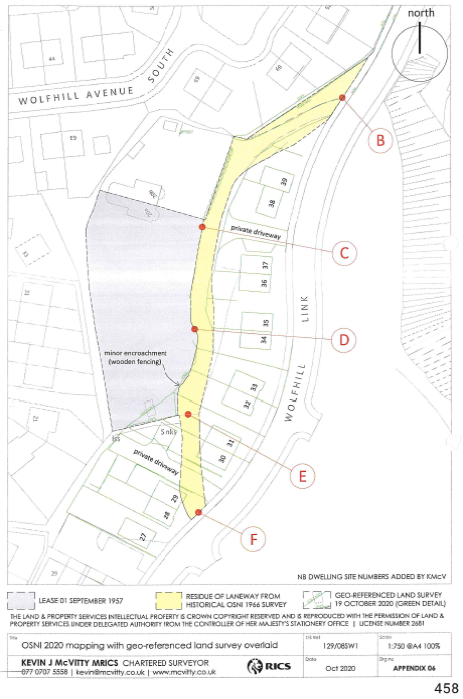

[8] In June 2020 the Defendant erected a more substantial fence at the point D on the map annexed to this judgment. This is a large post and board fence which prevents any access down the lane by any means beyond this point. The Defendant also replaced the hedge which formed the boundary between its property and that of the Plaintiffs with a fence of similar nature.

[9] Shortly after erecting this fencing, the Defendant made an application to the Lands Tribunal under article 5 of the Property (Northern Ireland) Order 1978 seeking modification of the right of way in order to allow the Defendant to develop its property in accordance with the extant planning permission. It is noteworthy that this application was not preceded by any relevant pre-action correspondence.

[10] When this injunction application came before the Court on 9 November 2020, the Defendant was no longer arguing that there should be modification of the right of way but rather was denying that any such right existed at all. In a skeleton argument filed on its behalf, the Defendant contended bluntly that the purported grant of the right of way was 'a nullity' and was ‘meaningless’.

[11] If the Defendant’s contention was correct, this would have represented a knock-out blow to the Plaintiffs’ claim. Equally, the parties agreed, if the Court were to find that the Plaintiff’s premises benefitted from an express right of way created by deed, it may impact upon the Court’s approach to the question of interlocutory relief. For both these reasons, I directed that the question of whether the Plaintiffs’ lands enjoyed the benefit of a right of way created by the Lease of 1 September 1957 be tried as a preliminary issue, pursuant to Order 33 rule 3 of the Rules of the Court of Judicature (NI) 1980.

[12] The Plaintiffs adduced an expert report from Mr Donald Eakin, a conveyancing Solicitor of considerable experience and former President of the Law Society of Northern Ireland. The Court has derived considerable benefit from this report. Mr Eakin expresses the opinion that the 1957 Lease represents the Plaintiffs’ root of title since it satisfies the forty year requirement under the Vendor and Purchaser Act 1874.

[13] The Defendant’s arguments in relation to the right of way were twofold. Firstly, it was said that the grantors who themselves were the owners of a leasehold interest could not grant a right of way over a third party’s land. Whilst, of course, a leasehold owner could not grant what he himself did not own, it is a legal nonsense to suggest he cannot grant an easement in identical terms to that enjoyed under his lease to his sub-lessee. An easement, as an incorporeal hereditament, can be alienated in the same manner as any other property right.

[14] The second issue was that of registration. The Defendant complained that it had no notice of the existence of the right of way as it had not been registered as a burden on its title. However, by section 38 and Schedule 5 of the Land Registration Act (Northern Ireland) 1970 such easements affect registered land without registration. It will, of course, have been evident to the Defendant that there was a laneway within the land which it acquired for development and this ought to have alerted it to the potential existence of easements.

[15] Analysis of the arguments put forward by the Defendant revealed them to be wholly without foundation. At the adjourned hearing on 26 November 2020, the Defendant conceded that the Plaintiffs’ property benefitted from an express grant of a right of way under the 1957 Lease.

Was there a substantial interference with the right of way?

[16] It is well-established that no action lies unless the owner of the dominant tenement which benefits from the easement can demonstrate that there has been substantial interference. In West v Sharp (2000) 79 P&CR 327, Mummery LJ set out the test:

“Not every interference with an easement, such as a right of way, is actionable. There must be substantial interference with the enjoyment of it. There is no actionable interference with a right of way if it can be substantially and practically exercised as conveniently after as before the occurrence of the alleged obstruction.”

[17] The evidence before the Court at this interlocutory stage was that the Plaintiffs and their family had regularly used the laneway both to access the premises at Glenview Avenue and also to walk to the former Glenside Farm. There was no dispute between the parties that the fencing erected by the Defendant prevented any access beyond point D on the map, whether by vehicle or on foot.

[18] I have concluded that this represents a substantial interference with the enjoyment of the right of way. The prevention of access at point D means that the right cannot be exercised as conveniently as it was prior to the erection of the fence. The Plaintiffs have conceded that any relief which they may seek in respect of the interference with the right of way beyond point E will sound only in damages but they contend they are entitled to an interlocutory injunction, both mandatory and prohibitory in nature, in relation to the interference which has occurred between the road and point E.

The test for interlocutory relief

[19] Section 91 of the Judicature (NI) Act 1978 entitles the High Court to grant a mandatory or other injunction at any stage of proceedings ‘in any case where it appears to the Court to be just and convenient to do so’. The discretion to grant an injunction on an interlocutory basis is, in most cases, governed by the principles set out by the House of Lords in American Cyanamid v Ethicon [1975] AC 396. These were well summarised by Deeny J in McLaughlin & Harvey v Department of Finance and Personnel [2008] NIQB 122:

“It can be seen that the test laid down by the House of Lords, is sequential.

(i) Has the plaintiff shown there is at least a serious issue to be tried?

(ii) If it has, has it shown the damages would not be an adequate remedy for the plaintiff and would be an adequate remedy for the defendant if an injunction were granted and it ultimately succeeded?

(iii) If there is doubt about the issue of damages the court will then address the balance of convenience between the parties.

(iv) Where other factors are evenly balanced it is prudent to preserve the status quo.

(v) If the relative strength of one party’s case is significantly greater than the other that may legitimately be taken into account.

(vi) There may be special factors in individual cases.”

[20] In the context of interference with property rights, however, the Court of Appeal in England & Wales has held that where title is in not in issue, and the interference is clear, the Plaintiff is prima facie entitled to an injunction and the Court need not consider the American Cyanamid principles. Such an injunction would issue even if the trespass in question did not cause actual harm. In Patel –v- WH Smith (Eziot) Limited [1987] 1 WLR 853 Balcombe LJ explained:

“If there is no arguable case…then questions of balance of convenience, status quo and damages being an adequate remedy do not arise. Prima facie the Plaintiffs are entitled to an injunction to restrain trespass on their land.”

[21] The Court of Appeal did recognise that there may be exceptional cases where, notwithstanding the existence of a continued trespass, the Court could properly decline to grant an injunction but Neill LJ concluded that such cases would be “very rare.”

[22] In a case such as this, therefore, the burden is on the Defendant at the interlocutory stage to demonstrate that there is some serious issue in relation to the Plaintiffs’ title or some arguable basis to assert a right to carry out the act which would otherwise constitute an unlawful interference.

Is there an arguable case?

[23] Having conceded that the grant of the right of way in the 1957 Lease was effective, the Defendant argued as follows:

(i) That the principle in Patel only applied to actions in trespass rather than those relating to interference with an easement;

(ii) There was an arguable case that the right of way had been abandoned;

(iii) The Plaintiffs had been guilty of delay such as to deprive them of the right to an interlocutory injunction;

(iv) The Plaintiffs’ offer of an undertaking in damages was worthless and this should militate against the grant of relief.

[24] The submission that Patel does not apply to interference with an easement is not legally coherent. The existence of, and interference with, a property right are common to both scenarios. If there is no arguable basis for the interference then the Plaintiff’s rights ought to enjoy the same protection.

[25] A plea of abandonment represents a difficult hurdle for a Defendant in a right of way case to surmount. Cumming-Bruce LJ summarised the law in Williams v Usherwood (1983) 45 P&CR 235, adopting the words of Buckley LJ in Gotobed v Pridmore (1971) EG 759:

“To establish abandonment of an easement the conduct of the dominant owner must, in our judgment, have been such as to make it clear that he had at the relevant time a firm intention that neither he nor any successor in title of his should thereafter make use of the easement…Abandonment is not to be lightly inferred. Owners of property do not normally wish to divest themselves of it unless it is to their advantage to do so, notwithstanding that they may have no present use for it.”

[26] When pressed for evidence in relation to the claim of abandonment, Mr Gibson referred to an aerial photograph, taken in 2012, which showed some foliage which had grown over the laneway although, on his own admission, this did not show the path of the laneway itself. Such evidence, taken at its height, could never amount to an arguable case that the Plaintiffs had abandoned the right of way. The Court also had the benefit of affidavit evidence, albeit untested, from the Plaintiffs in respect of the family’s use of the right of way.

[27] The belated plea that the Plaintiffs had been guilty of some culpable delay which should deprive them of relief was not pursued with any vigour. The evidence reveals that the first substantial interference with the right of way took place in November 2019 and the Plaintiffs swiftly sought legal advice to protect their rights. An interim arrangement was arrived at but the position changed when the Defendant erected the more substantial fence in June 2020. Further correspondence ensued and, in the absence of resolution, proceedings issued in September 2020. There is no merit in the claim that the Plaintiffs were guilty of any delay, let alone delay which would cause the Court to deny them relief to which they would otherwise be entitled.

[28] In relation to the proposed undertaking in damages, I note that the Plaintiffs are not people of substantial means. However, it should not be the case that the Courts only provide effective remedies to the wealthy. The impecuniosity of a Plaintiff is just one factor which weighs in the discretion - see Gould v Kay [2020] 7 WLUK 221. In any event, I am told that these Plaintiffs own the premises at Glenview Avenue outright and Ms Simpson QC has offered the usual undertaking in damages on their behalf. I will return to the appropriateness of requiring such an undertaking in due course, but I am not satisfied that the nature of the undertaking offered is such as to cause the Court to refuse the relief sought.

The Injunction

[29] I have concluded that the Defendant has no arguable case at this stage and that the Plaintiffs are entitled to interlocutory relief. I should stress that I would have reached the same conclusion had I been applying American Cyanamid principles. I concur with the learned authors of Gale on Easements (20th Edition at 14-85) when they conclude that damages are usually not an adequate remedy in cases where a dispute has arisen over an easement. I would also have found that the balance of convenience favoured the Plaintiffs in circumstances where the Defendant has blocked the right of way without any reasonable excuse. At all times the Defendant was acting at risk. It ought to have known that a right of way would have existed over and along the laneway and it did know that such a right was being asserted by the Plaintiffs from November 2019. By choosing to obstruct the right of way in June 2020 it invited the Plaintiffs to issue legal proceedings to protect their rights.

[30] The question then arises as to nature of the interlocutory relief which should be granted. I concur with the views expressed by Gillen J in Khan v Western Health and Social Services Trust [2010] NIQB 92 and by Lord Hoffman in National Commercial Bank Jamaica v Olint [2009] 1 WLR 149 that arguments over whether injunctions are prohibitory or mandatory are barren - what matters are the actual consequences of the injunction which the Court grants.

[31] I have concluded that it is just and convenient for the Court to order that the Defendant do remove the fence located at point D on the map and open up the right of way to point E. I do not make any specific order in relation to the lawns and kerbstones which may be affected by the opening up of the right of way. I note that, although part of the right of way may be within the physical curtilage of the gardens of site numbers 32 and 33, no title to this strip of land was transferred to the current owner who was aware of the existence of this dispute.

[32] I also order that the Defendant do not obstruct or interfere with the right of way between points B and E on the map by any means whatsoever, or otherwise trespass on the lands owned by the Plaintiffs.

[33] In all the circumstances, and having considered submissions on the issue, I do require the Plaintiffs to give an undertaking in damages as a condition of the grant of the injunction.

[34] I order that the Defendant do pay the Plaintiffs’ costs of the preliminary issue, such costs to be agreed or taxed in default of agreement, and I reserve the costs of the application for an interlocutory injunction to the trial Judge or further Order of the Court.

[35] This is a case which is suitable for an expedited trial. I express the view at this stage that the Lands Tribunal proceedings in relation to modification ought to be transferred to this Court and heard and determined at the same time as the remaining issues in the litigation.